- 1School of Physical Education and Sports, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China

- 2Division of Sports Science and Physical Education, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

- 3School of Physical Education, Yunnan Normal University, Yunnan, China

Background: Evidence on the association between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser (rs8192678) polymorphism and elite athlete status is inconsistent, and a prior meta-analysis has used a genotype-merging approach that may bias results.

Objective: This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to clarify the association between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser (rs8192678) polymorphism and elite endurance and power athlete status.

Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Library from inception to November 2025. Studies were included if they provided genotype frequency data for the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism in elite endurance or power athletes and non-athlete controls. Fixed or random-effects models were used to calculate odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic.

Results: 21 studies involving 5,795 athletes and 9,048 non-athlete controls were included. Compared with non-athlete controls, a higher frequency of the Gly/Gly genotype was observed in Caucasian endurance athletes (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.08–1.31; p < 0.001) and Caucasian power athletes (OR 1.30; 95% CI 1.17–1.44; p < 0.001). In Asians, no significant difference in the frequency of the Gly/Gly genotype was observed between endurance athletes and controls (OR 0.92; 95% CI 0.71–1.19; p = 0.523), whereas a lower frequency was observed in Asian power athletes (OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.53–0.90; p = 0.007).

Conclusion: Our findings demonstrate that the Gly/Gly genotype of the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism was associated with an increased likelihood of achieving elite athlete status in Caucasians, suggesting its potential as a genetic marker for athletic talent identification in this population. In Asians, no significant association was observed between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism and elite endurance athlete status, whereas the Gly/Gly genotype is associated with a lower likelihood of achieving elite power athlete status.

Systematic Review registration: identifier CRD420251148245.

1 Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing body of studies on the influence of genetics on athletic performance, which has significantly contributed to the field of sports science. Approximately 66% of the variation in athletic performance among individuals can be attributed to genetic factors (İpekoğlu et al., 2025). Research indicates that the heritable component of athletic traits may account for up to 90% of variation in anaerobic performance, 60% in cardiorespiratory function, and 70% in maximal muscular strength (Kartibou et al., 2025).

The PPARGC1A gene (located on chromosome 4p15.2) encodes the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1a (PGC-1α), a transcriptional coactivator that serves as a key regulator of numerous metabolic pathways (Zhuang et al., 2025). PGC-1α activates transcription factors, such as NRF-1, NRF-2, ERR, PPARγ, RXR, MEF2, FOXO1, HNF-4, and SREBP1, thereby orchestrating multiple mitochondrial and extramitochondrial pathways in cellular energy metabolism. These transcription factors regulate genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, lipogenesis, thermogenesis, and glucose utilization (Michael et al., 2001; Jornayvaz and Shulman, 2010; Huang et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2025). Furthermore, studies have reported that the expression of PPARGC1A increases in both rodent and human skeletal muscle following short-term and long-term exercise (Pilegaard et al., 2003; Terada and Tabata, 2004; Mathai et al., 2008; Russell et al., 2003).

In sports science, the most studied polymorphism in the PPARGC1A gene is the Gly482Ser (rs8192678) polymorphism, which exerts an influence on both mRNA expression and protein levels (Eynon et al., 2010). The PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism (rs8192678) is a common missense variant that replaces glycine (Gly) with serine (Ser) at codon 482, producing three genotypes: Gly/Gly, Gly/Ser, and Ser/Ser (Hall et al., 2023). Numerous studies have reported associations between this genetic variant and endurance or power athlete status, but findings across different studies are contradictory. For instance, Eynon et al. found the Gly/Gly genotype and Gly allele to be more common in both endurance and power athletes compared with non-athlete controls (Eynon et al., 2011). However, a subsequent study by Grealy et al. analyzing elite Ironman triathletes found no significant association between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism and endurance performance (Grealy et al., 2015). Additionally, Gineviciene et al. observed that among Lithuanians, power athletes had a slightly lower frequency of the Gly/Gly genotype and Gly allele than non-athletes (Gineviciene et al., 2016). Although two previous meta-analyses have investigated this association (Chen et al., 2019; Tharabenjasin et al., 2019), genotype-specific evaluations remain limited. Of these, one meta-analysis pooled genotypes that may have opposing effects, an approach that can obscure genotype-specific associations and introduce bias (Tharabenjasin et al., 2019). Additionally, the dataset in Tharabenjasin et al. included athletes from various competitive levels, ranging from college to international athletes. Furthermore, both meta-analyses restricted their literature searches to studies published up to 2018. Together, the emergence of new studies and methodological limitations justify an updated systematic assessment. Therefore, this meta-analysis aims to explore the potential associations between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism and elite endurance and power athlete status by meta-analyzing studies on the distribution of genotypes of this polymorphism in endurance and power athletes compared with non-athlete controls.

2 Methods

This meta-analysis was registered on PROSPERO with the registration number CRD420251148245 and was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021).

2.1 Eligibility criteria

Our analysis includes studies that investigate the association between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism and elite endurance or power athlete status, defined as participation at national or international competitive levels. Therefore, studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) evaluated the association between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism and elite endurance or power athlete status; (2) included healthy non-athlete individuals as controls; (3) provided genotype frequency data for the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism; (4) conformed to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the control group; (5) selected the most recent publication in cases of duplicate data. Studies were excluded for the following reasons: (1) review articles; (2) studies without a control group; (3) absence of genotype frequency data for the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism; (4) included athletes not competing at national or international level.

2.2 Literature search strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted in electronic databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Library from their inception to November 2025. No restrictions were applied regarding language or publication date. The literature search was conducted using the following key terms: “PPARGC1A,” “Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-alpha,” “PGC-1α,” “rs8192678,” “Gly482Ser,” “polymorphism,” “athletes,” “sports.” Full search terms were provided in Supplementary Table S1. To ensure comprehensive coverage, we also supplemented the electronic search by conducting manual searches of the reference lists of included articles and relevant reviews.

2.3 Data extraction

Two authors independently extracted data from all included studies. Any discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third author. Key data were extracted from each of the included studies, including study characteristics (author, publication year, and country), participant characteristics (ethnicity, sample size, sex, age, and athlete status), the number of PPARGC1A Gly/Gly, Gly/Ser, and Ser/Ser genotypes in each group, and the genotyping methods.

2.4 Quality assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the methodological quality of the studies based on three domains: Selection (four items), Comparability (one item), and Exposure (three items). Each item meeting the criteria was awarded one star, with a maximum possible total of nine stars. Studies could receive up to one star for each item within the Selection and Exposure domains and up to two stars for the Comparability domain. Studies with a score ≥7 were considered high quality. Two authors independently conducted the quality assessment, and any disagreements were resolved through consultation with a third author.

2.5 Statistical analyses

The association between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism and elite athlete status was determined by calculating pooled odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of ≤0.05. The statistical heterogeneity across the included studies was assessed using the I2 statistic. I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% represented low, moderate, and high heterogeneity respectively. The heterogeneity level determined model selection: fixed-effects models were applied when I2 < 50%, while random-effects models were used when I2 > 50%. Publication bias in our meta-analysis was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots for all comparisons. Sensitivity analyses were performed by sequentially removing each study to assess the stability of the overall results. This meta-analysis was conducted using Stata 18.0.

3 Results

3.1 Selection of studies

A total of 967 records were identified through database searches and manual search. After removing duplicates (n = 257) and excluding studies based on the title and abstract screening (n = 661), 49 studies remained. Based on the full-text assessment, a further 29 studies were excluded for the following reasons: no controls (n = 6), data insufficient or unusable (n = 8), duplicate populations (n = 7), review articles (n = 2), control not in HWE (n = 2), and athletes not competing at national or international level (n = 3). Finally, 21 eligible studies were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1).

3.2 Characteristics of the included studies

These studies involved a total of 5,795 athletes (comprising 3,351 endurance athletes and 2,444 power athletes) and 9,048 controls. According to the type of sports, athletes were divided into endurance and power groups. The endurance group included marathon, biathlon, orienteering, steeplechase, long-distance swimming, football, pentathlon, rowing, road cycling, cross-country skiing, long-distance track and field athletics, triathlon, long-distance speed skating, race walking, and mountain biking. The power group included weightlifting, short-distance track and field athletics, powerlifting, kayaking, judo, wrestling, boxing, fencing, short-distance swimming, speed skating, alpine skiing, artistic gymnastics, throwing events, jumping events, bodybuilding, ski jumping, canoe speed, basketball, volleyball, tennis, hockey and decathlon. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Distributions of the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism genotypes in endurance and power athletes across included studies are presented in Supplementary Table S2; Supplementary Table S3 respectively.

3.3 Study quality assessment

Following the assessment using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), 2 study scored 6 points, 8 studies scored 7 points, 10 studies scored 8 points, and 1 study scored 9 points (Table 1). With a mean score of 7.48 ± 0.74, the overall quality of the evidence was considered satisfactory.

3.4 Meta-analysis

3.4.1 Endurance athletes

The distribution of PPARGC1A Gly/Gly, Gly/Ser, and Ser/Ser genotypes in endurance athletes is as follows. A higher frequency of the Gly/Gly genotype was observed compared with the Gly/Ser genotype in Caucasians (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.06–1.71; p = 0.015; 78.7% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S1), whereas a lower frequency of the Gly/Gly genotype was observed in Asians (OR 0.41; 95% CI 0.30–0.57; p < 0.001; 9% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S1). When combining Caucasian and Asian populations, no significant difference between the Gly/Gly genotype and the Gly/Ser genotype was detected (OR 1.16; 95% CI 0.88–1.53; p = 0.301; 86.6% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S1). Compared with the Ser/Ser genotype, the Gly/Ser genotype was significantly more frequent in the combined populations (OR 7.21; 95% CI 5.30–9.81; p < 0.001; 74.8% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S2). This advantage was more pronounced in Caucasians (OR 8.14; 95% CI 5.93–11.16; p < 0.001; 69.3% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S2) than in Asians (OR 3.49; 95% CI 2.55–4.76; p < 0.001; 0% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S2). Similarly, the Gly/Gly genotype showed a significantly higher frequency than the Ser/Ser genotype in the combined populations (OR 8.79; 95% CI 5.25–14.74; p < 0.001; 91.4% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S3), with Caucasians showing the same trend (OR 11.05; 95% CI 7.16–17.06; p < 0.001; 84.2% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S3), whereas no statistically significant association was observed in Asians (OR 1.39; 95% CI 0.81–2.40; p = 0.229; 62.4% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S3).

When comparing endurance athletes with controls, we found a higher frequency of the Gly/Gly genotype in Caucasian athletes (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.08–1.31; p < 0.001; 43.7% heterogeneity) (Figure 2A), whereas no significant association was detected in Asians (OR 0.92; 95% CI 0.71–1.19; p = 0.523; 0% heterogeneity) (Figure 2A).When combining both populations, the Gly/Gly genotype frequency was higher in athletes than controls (OR 1.15; 95% CI 1.06–1.26; p = 0.001; 44.5% heterogeneity) (Figure 2A). Analyses of the Ser/Ser genotype showed no statistically significant differences: Caucasians (OR 0.81; 95% CI 0.59–1.10; p = 0.179; 60.7% heterogeneity) (Figure 2B), Asians (OR 1.09; 95% CI 0.82–1.45; p = 0.548; 0% heterogeneity) (Figure 2B), or the combined populations (OR 0.86; 95% CI 0.66–1.12; p = 0.263; 59.3% heterogeneity) (Figure 2B). In allelic comparisons, a higher frequency of the Gly allele was detected in the combined populations (OR 1.15; 95% CI 1.01–1.30; p = 0.032; 67% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S4) and Caucasians (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.04–1.36; p = 0.014; 66.5% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S4). However, no significant differences were found in Asians (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.79–1.12; p = 0.468; 9.6% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 2. Forest plot of the comparison between genotype frequencies in endurance athletes versus controls. (A) Gly/Gly vs. Gly/Ser + Ser/Ser and (B) Ser/Ser vs. Gly/Gly + Gly/Ser.

When comparing individual genotypes between endurance athletes and controls, the frequency of carrying the Gly/Gly genotype relative to the Gly/Ser genotype was higher in endurance athletes than in controls (OR 1.12; 95% CI 1.02–1.23; p = 0.016; 0.3% heterogeneity) (Figure 3A), with Caucasians showing the same trend (OR 1.15; 95% CI 1.04–1.27; p = 0.006; 0% heterogeneity) (Figure 3A) and Asians exhibiting no significant difference (OR 0.93; 95% CI 0.71–1.23; p = 0.628; 0% heterogeneity) (Figure 3A). In the comparison of Gly/Ser and Ser/Ser genotypes, no significant difference was observed between endurance athletes and controls in Caucasians (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.86–1.54; p = 0.351; 50.6% heterogeneity) (Figure 3B), Asians (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.70–1.27; p = 0.694; 0% heterogeneity) (Figure 3B), or the combined populations (OR 1.10; 95% CI 0.86–1.40; p = 0.449; 47.2% heterogeneity) (Figure 3B). Similarly, In the comparison of Gly/Gly and Ser/Ser genotypes, no significant difference was found for Caucasians (OR 1.35; 95% CI 0.95–1.91; p = 0.090; 64.4% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S5), Asians (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.62–1.25; p = 0.479; 12.4% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S5), or the combined populations (OR 1.24; 95% CI 0.92–1.67; p = 0.154; 64% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 3. Forest plot of the comparison between individual genotype frequencies in endurance athletes versus controls. (A) Gly/Gly vs. Gly/Ser and (B) Gly/Ser vs. Ser/Ser.

3.4.2 Power athletes

The distribution of PPARGC1A Gly/Gly, Gly/Ser, and Ser/Ser genotypes in power athletes is as follows. Compared with the Gly/Ser genotype, the Gly/Gly genotype was more frequent in Caucasians (OR 1.47; 95% CI 1.11–1.93; p = 0.006; 72.5% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S6), but less frequent in Asians (OR 0.36; 95% CI 0.26–0.48; p < 0.001; 0% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S6) and showed no significant association in the combined populations (OR 1.13; 95% CI 0.78–1.64; p = 0.516; 88.6% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S6). The frequency of the Gly/Ser genotype was significantly higher than the Ser/Ser genotype in Caucasians (OR 6.80; 95% CI 5.70–8.11; p < 0.001; 37.2% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S7), Asians (OR 5.11; 95% CI 3.66–7.14; p < 0.001; 0% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S7), and the combined populations (OR 6.42; 95% CI 5.50–7.50; p < 0.001; 32.3% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S7). Similarly, the frequency of the Gly/Gly genotype was higher than the Ser/Ser genotype in Caucasians (OR 10.41; 95% CI 7.57–14.32; p < 0.001; 57.9% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S8), Asians (OR 1.82; 95% CI 1.28–2.57; p = 0.001; 0% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S8), and the combined populations (OR 8.13; 95% CI 5.06–13.05; p < 0.001; 86.4% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S8).

When comparing power athletes with controls, the Gly/Gly genotype was more frequent in power athletes in the combined populations (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.09–1.31; p < 0.001; 58.6% heterogeneity) (Figure 4A) and in Caucasians (OR 1.30; 95% CI 1.17–1.44; p < 0.001; 13% heterogeneity) (Figure 4A), but less frequent in Asians (OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.53–0.90; p = 0.007; 0% heterogeneity) (Figure 4A). In contrast, a lower frequency of the Ser/Ser genotype was observed in the combined populations (OR 0.84; 95% CI 0.72–0.99; p = 0.033; 17.9% heterogeneity) and in Caucasians (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.68–0.97; p = 0.025; 29.7% heterogeneity) (Figure 4B), whereas no significant difference was detected in Asians (OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.69–1.30; p = 0.733; 0% heterogeneity) (Figure 4B). Furthermore, there was a higher frequency of the Gly allele in the combined populations (OR 1.15; 95% CI 1.07–1.24; p < 0.001; 49.4% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S9) and in Caucasians (OR 1.22; 95% CI 1.13–1.32; p < 0.001; 18.2% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S9), but no significant difference was detected in Asians (OR 0.86; 95% CI 0.72–1.03; p = 0.099; 0% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S9).

Figure 4. Forest plot of the comparison between genotype frequencies in power athletes versus controls. (A) Gly/Gly vs. Gly/Ser + Ser/Ser and (B) Ser/Ser vs. Gly/Gly + Gly/Ser.

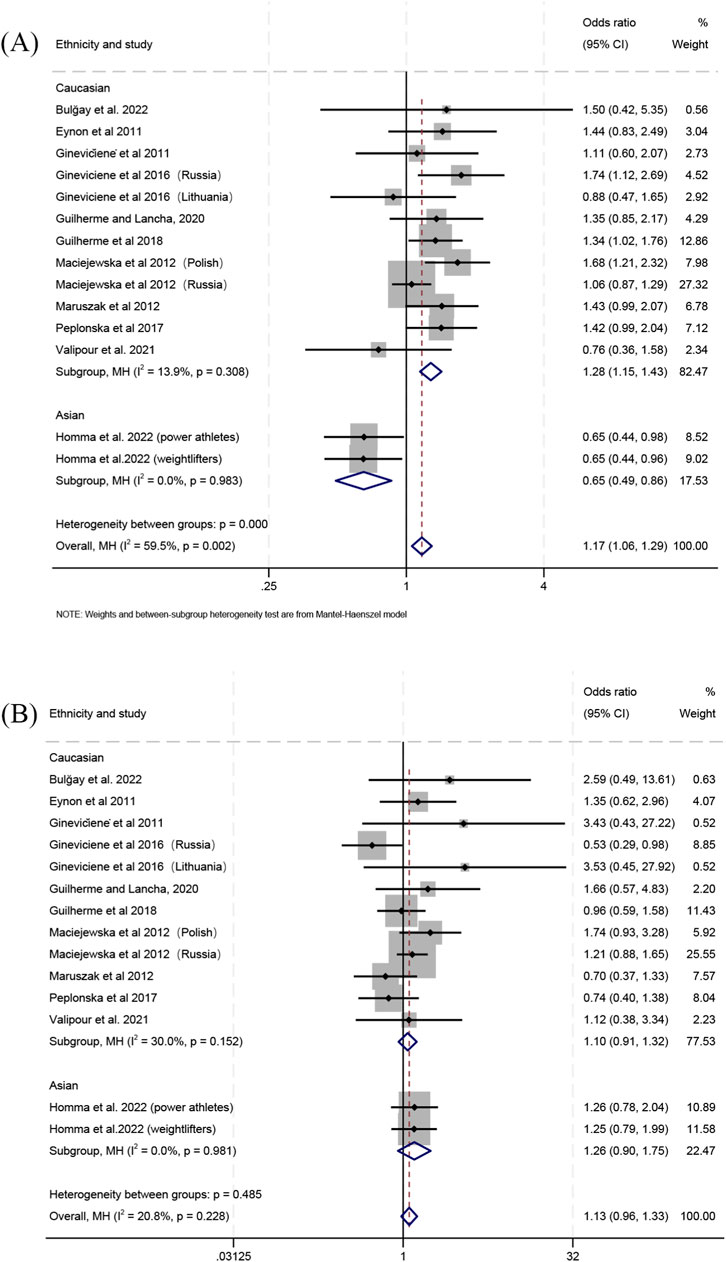

When comparing individual genotypes between power athletes and controls, the frequency of the Gly/Gly genotype relative to the Gly/Ser genotype was higher in the combined populations (OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.06–1.29; p = 0.002; 59.5% heterogeneity) (Figure 5A) and in Caucasians (OR 1.28; 95% CI 1.15–1.43; p < 0.001; 13.9% heterogeneity) (Figure 5A), but lower in Asians (OR 0.65; 95% CI 0.49–0.86; p = 0.003; 0% heterogeneity) (Figure 5A). For the comparison of the Gly/Ser and Ser/Ser genotypes, no significant differences between power athletes and controls were detected in Caucasians (OR 1.10; 95% CI 0.91–1.32; p = 0.332; 30% heterogeneity) (Figure 5B), Asians (OR 1.26; 95% CI 0.90–1.75; p = 0.181; 0% heterogeneity) (Figure 5B) or the combined populations (OR 1.13; 95% CI 0.96–1.33; p = 0.134; 20.8% heterogeneity) (Figure 5B). Additionally, the frequency of the Gly/Gly genotype relative to the Ser/Ser genotype was higher in power athletes than in controls for the combined populations (OR 1.26; 95% CI 1.07–1.48; p = 0.005; 37.7% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S10) and Caucasians (OR 1.40; 95% CI 1.17–1.68; p < 0.001; 25.8% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S10), whereas no significant difference was observed in Asians (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.57–1.17; p = 0.273; 0% heterogeneity) (Supplementary Figure S10).

Figure 5. Forest plot of the comparison between individual genotype frequencies in power athletes versus controls. (A) Gly/Gly vs. Gly/Ser and (B) Gly/Ser vs. Ser/Ser.

3.5 Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

To assess the effect of each study on the overall results, we conducted sensitivity analysis. The use of fixed-effects and random-effects models was based on the percentage of heterogeneity. After excluding one study each time, the ORs, 95% confidence interval, and p-values did not significantly change, which may indicate the robustness of our results. Moreover, the visual inspection of the funnel plots suggested no publication bias among the included studies. The information of funnel plots is provided in Supplementary Figures S11–S29.

4 Discussion

The primary objective of this meta-analysis was to investigate the associations between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism and athlete status, focusing on genotype distribution in endurance and power athletes compared with controls. In Caucasians, the distribution of the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism in both endurance and power athletes followed the trend: Gly/Gly > Gly/Ser > Ser/Ser. Furthermore, both the Gly/Gly genotype and the Gly allele were significantly more frequent in Caucasian elite athletes compared with controls. Specifically, the Gly/Gly genotype was more frequently observed than the Gly/Ser genotype in both endurance and power athletes compared with controls. In contrast, direct comparisons of Gly/Ser versus Ser/Ser revealed no significant differences between athletes and controls in either discipline.

Notably, three studies respectively investigating Asian athletes from China and Japan (He et al., 2015; Yvert et al., 2016; Homma et al., 2022), included 758 athletes (389 endurance athletes and 369 power athletes). For endurance athletes, there is no statistically significant differences in genotype frequencies (Gly/Gly, Gly/Ser, Ser/Ser) compared with their respective controls. For power athletes, the Gly/Gly genotype is less frequent relative to controls, whereas the Gly/Ser and Ser/Ser genotypes show no significant differences between athletes and controls. These findings suggest that the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism may not be associated with Asian athlete status. However, this conclusion should be interpreted with caution. The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) reveals significant inter-population differences in rs8192678 allele frequencies (Chen et al., 2024). The Ser allele is more common in East Asians, less frequent in Caucasians, and rare in African populations. Consequently, the baseline prevalence of the Gly/Gly genotype is lower in East Asians than in Caucasians. These background differences, combined with the limited sample size of existing Asian athlete cohorts, may reduce statistical power to detect genotype–phenotype effects, which may partly explain the absence of significant associations in our meta-analysis.

Our findings demonstrate that the Gly/Gly genotype is advantageous for both endurance and power athletic performance. This finding is consistent with two previous meta-analyses (Chen et al., 2019; Tharabenjasin et al., 2019) and is further supported, for endurance-specific cohorts, by a homogeneous meta-analysis of long-distance runners and road cyclists (Konopka et al., 2022).Mechanistically, this genotype enhances the expression of PGC-1α, a key transcriptional coactivator that regulates cellular energy metabolism. For endurance athletes, enhanced PGC-1α expression promotes GLUT4-mediated glucose transport and muscle glycogen storage, ultimately improving metabolic efficiency and athletic performance (Katz et al., 1986; Wasserman, 2009; Wasserman et al., 2011; Richter and Hargreaves, 2013). Furthermore, PGC-1α associates with and coactivates nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF-1), thereby upregulating the expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (mtTFA), which directly activates the transcription and replication of mitochondrial DNA. One study found that cells overexpressing PGC-1α exhibited a 57% increase in mitochondrial density relative to control cells (Wu et al., 1999). This enhanced skeletal muscle mitochondrial content can lead to reduced lactate production, enhanced fat utilization, and improved endurance performance (Coyle et al., 1988; LeBlanc et al., 2004). Furthermore, this increased oxidative capacity also elevates the rate of carbohydrate oxidation when required, enabling higher power output and contributing to improved athletic performance (Westgarth-Taylor et al., 1997). Upregulation of PGC-1α has been shown to significantly enhance fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle, which reduces reliance on finite muscle glycogen reserves, prolongs exercise duration, and ultimately improves endurance performance (Huang et al., 2017; Muscella et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2025; Gerhart-Hines et al., 2007). Moreover, PGC-1α expression induces a functional shift in skeletal muscle, converting fast-twitch type IIb fibers toward a more oxidative type IIa and type I fibers (Lin et al., 2002).

Notably, the same metabolic adaptations also contribute to enhanced power performance. The increase in glucose transport and muscle glycogen storage provides sufficient substrate for the glycolytic system, thereby supporting high-power output. Moreover, the elevated mitochondrial content reduces lactate accumulation during high-intensity efforts (Chesley et al., 1996). Additionally, the improved oxidative capacity is a key factor determining the rate of PCr resynthesis and the restoration of performance during repeated sprint exercises (Bogdanis et al., 1996). Studies have demonstrated the aerobic system contributes substantially to energy production even in high-intensity efforts: Spencer and Gastin et al. revealed that the aerobic system is activated rapidly after the onset of exercise and becomes the predominant energy supplier between 15 and 30 s for the 400-m, 800-m, and 1500-m events (Spencer and Gastin, 2001). Similarly, Hargreaves and Spriet et al. demonstrated that aerobic ATP production is activated during very intense exercise, with approximately 50% of the energy contribution in the final 5 s of a 30-s sprint being derived aerobically (Hargreaves and Spriet, 2020). Moreover, achieving elite athlete status depends not only on athletic performance capacity but also on the risk of sports-related injuries and the ability to recover from them. Evidence from candidate-gene and genome-wide association studies indicates that genetic background contributes to inter-individual variability in susceptibility to musculoskeletal injuries and in the rate of recovery (Koks et al., 2020; Ebert et al., 2023; Massidda et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2025). Several experimental studies using acute skeletal muscle injury models have shown that muscle-specific overexpression of PGC-1α leads to smaller necrotic areas, faster clearance of necrotic debris, and better preservation of muscle architecture after injury (Dinulovic et al., 2016; Washington et al., 2022). Given that power athletes are at a particularly high risk of acute musculoskeletal injuries, we hypothesized that the Gly/Gly genotype would confer an additional advantage in this population by mitigating the risk of such injuries and/or facilitating faster recovery, thereby contributing to their likelihood of achieving elite status.

Our findings also demonstrate that individuals carrying one or two copies of the Ser allele of the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism show no significant association with elite endurance athlete status and exhibit a lower likelihood of achieving elite power athlete status. This finding diverges from the conclusions of two prior meta-analyses (Chen et al., 2019; Tharabenjasin et al., 2019). Potential explanations for this discrepancy include the larger sample size incorporated in the present meta-analysis and potential differences in population genetic backgrounds. In addition, the previously reported association may have been confounded by the strong selective advantage of the Gly/Gly genotype, which increases the overall Gly allele frequency in athletes rather than reflecting a true effect of the heterozygous genotype. To date, the functional impact of the Ser allele remains controversial. Several studies support an impaired functional role associated with the Ser allele. For instance, Stefan et al. found that the Gly/Ser or Ser/Ser genotype in PPARGC1A was associated with lower aerobic fitness (Stefan et al., 2007), and Petr et al. reported that carriers of the Ser allele exhibited reduced training responsiveness after aerobic training (Petr et al., 2018). Moreover, Steinbacher et al. reported that the Ser-encoding allele inhibits the exercise-induced transition from type II to type I muscle fibers, although it does not affect improvements in mitochondrial biogenesis, capillarization, or lipid metabolism (Steinbacher et al., 2015). In contrast, other studies report no functional deficit under certain conditions. Okauchi et al. demonstrated that no significant difference in the level of co-activation was observed between the wild-type (Gly482) and variant (Ser482) PGC-1α proteins (Okauchi et al., 2008). Furthermore, one study revealed that the Ser482 allele exerted no significant influence on PGC-1α mRNA expression levels in young individuals but was associated with reduced expression in elderly carriers (Ling et al., 2004), suggesting an age-dependent functional impact of the Ser allele.

This study identifies methodological limitations in the approach of Tharabenjasin et al. who merged antagonistic genotypes (Gly/Gly + Ser/Ser) into a single reference group, which may introduce bias (Tharabenjasin et al., 2019). First, because genotype frequencies sum to 100%, the beneficial effect of the Gly/Gly genotype will necessarily reduce the proportions of the remaining genotypes in athletes. Thus, a lower frequency of Gly/Ser in athletes relative to controls cannot be interpreted as evidence that it is disadvantageous; it may instead reflect the dominance of Gly/Gly genotype. Second, combining opposite-effect genotypes (Gly/Gly + Ser/Ser) distorts the baseline of the reference group. For instance, if the Gly/Ser genotype has an enhancing or neutral effect on athletic performance, the Gly/Gly genotype is significantly more frequent in athletes than in controls, and the Ser/Ser genotype is slightly less frequent. Consequently, the combined frequency of Gly/Gly + Ser/Ser genotypes may be higher in athletes than in controls. This results in the frequency of the Gly/Ser genotype in athletes appearing relatively lower than in controls. Alternatively, if the Gly/Ser genotype has a detrimental effect on athletic performance and the frequency of Gly/Gly + Ser/Ser genotypes is lower in athletes than in controls. This results in the frequency of the Gly/Ser genotype in athletes appearing relatively higher than in controls. Therefore, to avoid confounding effects arising from the opposing influences of Gly/Gly and Ser/Ser genotypes, the present study separately compared Gly/Gly versus Gly/Ser, Gly/Ser versus Ser/Ser, and Gly/Gly versus Ser/Ser to reevaluate the impact of the Gly/Ser genotype on athletic performance. Furthermore, as noted by Chen et al., the study by Tharabenjasin et al. incorporated duplicate genotype data from overlapping populations (Chen et al., 2019), further underscoring the need for a re-evaluation of this topic.

This meta-analysis has several limitations. First, due to the scarcity of studies on the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism in Asian populations, particularly among power athletes, our findings are primarily applicable to Caucasians. Second, although we dichotomized athletic disciplines into “power” and “endurance” groups for this meta-analysis, this approach may oversimplify the complex physiological demands of different sports. Additionally, we observed high heterogeneity in some of the analyzed groups. Despite conducting subgroup analyses by ethnicity and genotyping method, the sources of heterogeneity could not be definitively identified. Finally, due to the unavailability of comprehensive individual data from the included studies, we were unable to perform sex-based subgroup analyses. This represents a critical shortcoming, considering that sex exerts a profound influence on both gene expression and athletic performance phenotypes (Singh et al., 2018; Senefeld and Hunter, 2024; Hunter et al., 2023). For instance, Mägi et al. reported that the ACE ID and ACTN3 RR genotypes were significantly associated with elite male skier status in a longitudinal cohort, but no such association was observed in females (Mägi et al., 2016).

Our findings suggest that the Gly/Gly genotype of the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism may represent a candidate genetic marker associated with elite athlete status in Caucasians. Therefore, screening for the Gly/Gly genotype in youth talent identification and elite athlete development programs could contribute to a more scientific evaluation of genetic predisposition and optimize the allocation of training resources. These findings provide strong evidence for the role of genetics in athletic performance. Meanwhile, the lack of a significant association in Asian endurance athletes highlights the need for population-specific approaches in genetic profiling. To improve the accuracy of talent identification, we recommend integrating this marker with other sports-related genes into polygenic scores.

In conclusion, the association between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism and elite athlete status appears population-specific. In Caucasians, the Gly/Gly genotype of the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism was associated with an increased likelihood of achieving elite athlete status, whereas the Gly/Ser and Ser/Ser genotypes showed no significant association with elite endurance athlete status and were associated with a lower likelihood of achieving elite power athlete status. In Asians, no significant association was observed between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism and elite endurance athlete status. The Gly/Gly genotype is associated with a lower likelihood of achieving elite power athlete status, whereas the Gly/Ser and Ser/Ser genotypes show no significant association with elite power athlete status. In this meta-analysis, we resolve methodological limitations in a previous meta-analysis (Tharabenjasin et al., 2019), thereby providing a more accurate evaluation. Future studies should enroll diverse ethnic cohorts, report data stratified by sex and conduct functional experiments to elucidate how the PPARGC1A polymorphisms modulate energy metabolism and athletic performance.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

WS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis, Data curation. LY: Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Validation, Investigation. ZH: Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Validation, Investigation. FD: Software, Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Validation. JS: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing, Resources. YX: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision. XS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Open access joint supported by Joint Supported by Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation and Sports Innovation and Development of China (2025AFD658), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (CCNU24JCPT007), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (CCNU24JCPT009).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2025.1733458/full#supplementary-material

References

Bogdanis G. C., Nevill M. E., Boobis L. H., Lakomy H. K. (1996). Contribution of phosphocreatine and aerobic metabolism to energy supply during repeated sprint exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 80, 876–884. doi:10.1152/jappl.1996.80.3.876

Bulğay C., Zorba E., Akman O., Bayraktar I., Kazan H. H., Ergun M. A., et al. (2022). Evaluation of association between PPARGC1A gene polymorphism and competitive performance of elite athletes. Gazi Beden Eğit. Ve Spor Bilim. Derg. 27, 323–332. doi:10.53434/gbesbd.1126033

Chen Y., Wang D., Yan P., Yan S., Chang Q., Cheng Z. (2019). Meta-analyses of the association between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism and athletic performance. Biol. Sport 36, 301–309. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2019.88752

Chen S., Francioli L. C., Goodrich J. K., Collins R. L., Kanai M., Wang Q., et al. (2024). A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature 625, 92–100. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06045-0

Chesley A., Heigenhauser G. J., Spriet L. L. (1996). Regulation of muscle glycogen phosphorylase activity following short-term endurance training. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 270, E328–E335. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1996.270.2.E328

Coyle E. F., Coggan A. R., Hopper M. K., Walters T. J. (1988). Determinants of endurance in well-trained cyclists. J. Appl. Physiol. 64, 2622–2630. doi:10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2622

Dinulovic I., Furrer R., Di Fulvio S., Ferry A., Beer M., Handschin C. (2016). PGC-1α modulates necrosis, inflammatory response, and fibrotic tissue formation in injured skeletal muscle. Skelet. Muscle 6, 38–49. doi:10.1186/s13395-016-0110-x

Ebert J. R., Magi A., Unt E., Prans E., Wood D. J., Koks S. (2023). Genome-wide association study identifying variants related to performance and injury in high-performance athletes. Exp. Biol. Med. 248, 1799–1805. doi:10.1177/15353702231198068

Eynon N., Meckel Y., Sagiv M., Yamin C., Amir R., Sagiv M., et al. (2010). Do PPARGC1A and PPARα polymorphisms influence sprint or endurance phenotypes? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 20, E145–E150. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00930.x

Eynon N., Ruiz J. R., Meckel Y., Moran M., Lucia A. (2011). Mitochondrial biogenesis related endurance genotype score and sports performance in athletes. Mitochondrion 11, 64–69. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2010.07.004

Gerhart-Hines Z., Rodgers T., Bare O., Lerin C., Kim S.-H., Mostoslavsky R., et al. (2007). Metabolic control of muscle mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation through.

Ginevičienė V., Pranckevičienė E., Milašius K., Kučinskas V. (2011). Gene variants related to the power performance of the Lithuanian athletes. Open Life Sci. 6, 48–57. doi:10.2478/s11535-010-0102-5

Gineviciene V., Jakaitiene A., Tubelis L., Kucinskas V. (2014). Variation in the ACE, PPARGC1A and PPARA genes in lithuanian football players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 14, S289–S295. doi:10.1080/17461391.2012.691117

Gineviciene V., Jakaitiene A., Aksenov M., Aksenova A., Druzhevskaya A., Astratenkova I., et al. (2016). Association analysis of ACE, ACTN3 and PPARGC1A gene polymorphisms in two cohorts of european strength and power athletes. Biol. Sport 33, 199–206. doi:10.5604/20831862.1201051

Grealy R., Herruer J., Smith C. L. E., Hiller D., Haseler L. J., Griffiths L. R. (2015). Evaluation of a 7-gene genetic profile for athletic endurance phenotype in ironman championship triathletes. PLOS One 10, e0145171. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145171

Guilherme J. P. L. F., Lancha A. H. (2020). Total genotype score and athletic status: an exploratory cross-sectional study of a brazilian athlete cohort. Ann. Hum. Genet. 84, 141–150. doi:10.1111/ahg.12353

Guilherme J. P. L. F., Bertuzzi R., Lima-Silva A. E., Pereira A. D. C., Lancha Junior A. H. (2018). Analysis of sports-relevant polymorphisms in a large brazilian cohort of top-level athletes. Ann. Hum. Genet. 82, 254–264. doi:10.1111/ahg.12248

Hall E. C. R., Lockey S. J., Heffernan S. M., Herbert A. J., Stebbings G. K., Day S. H., et al. (2023). The PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism is associated with elite long-distance running performance. J. Sports Sci. 41, 56–62. doi:10.1080/02640414.2023.2195737

Hargreaves M., Spriet L. L. (2020). Skeletal muscle energy metabolism during exercise. Nat. Metab. 2, 817–828. doi:10.1038/s42255-020-0251-4

He Z.-H., Hu Y., Li Y.-C., Gong L.-J., Cieszczyk P., Maciejewska-Karlowska A., et al. (2015). PGC-related gene variants and elite endurance athletic status in a chinese cohort: a functional study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 25, 184–195. doi:10.1111/sms.12188

Homma H., Saito M., Saito A., Kozuma A., Matsumoto R., Matsumoto S., et al. (2022). The association between total genotype score and athletic performance in weightlifters. Genes 13, 2091. doi:10.3390/genes13112091

Huang T.-Y., Zheng D., Houmard J. A., Brault J. J., Hickner R. C., Cortright R. N. (2017). Overexpression of PGC-1α increases peroxisomal activity and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in human primary myotubes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 312, E253–E263. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00331.2016

Huang M., Claussnitzer M., Saadat A., Coral D. E., Kalamajski S., Franks P. W. (2023). Engineered allele substitution at PPARGC1A rs8192678 alters human white adipocyte differentiation, lipogenesis, and PGC-1α content and turnover. Diabetologia 66, 1289–1305. doi:10.1007/s00125-023-05915-6

Hunter S. K., Angadi S. S., Bhargava A., Harper J., Hirschberg A. L., Levine B. D., et al. (2023). The biological basis of sex differences in athletic performance: consensus statement for the american college of sports medicine. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 55, 2328–2360. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000003300

İpekoğlu G., Çetin T., Sırtbaş T., Kılıç R., Odabaşı M., Bayraktar F. (2025). Candidate gene polymorphisms and power athlete status: a meta-analytical approach. J. Physiol. Biochem. 81, 229–247. doi:10.1007/s13105-025-01071-0

Jornayvaz F. R., Shulman G. I. (2010). Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem. 47, 69–84. doi:10.1042/bse0470069

Kartibou J., El Ouali E. M., Del Coso J., Hackney A. C., Rfaki A., Saeidi A., et al. (2025). Association between the c.34C > T (rs17602729) polymorphism of the AMPD1 gene and the status of endurance and power athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 55, 1429–1448. doi:10.1007/s40279-025-02202-9

Katz A., Broberg S., Sahlin K., Wahren J. (1986). Leg glucose uptake during maximal dynamic exercise in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 251, E65–E70. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1986.251.1.E65

Koks S., Wood D. J., Reimann E., Awiszus F., Lohmann C. H., Bertrand J., et al. (2020). The genetic variations associated with time to aseptic loosening after total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 35, 981–988. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.11.004

Konopka M. J., Van Den Bunder J. C. M. L., Rietjens G., Sperlich B., Zeegers M. P. (2022). Genetics of long-distance runners and road cyclists—a systematic review with meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 32, 1414–1429. doi:10.1111/sms.14212

LeBlanc P. J., Howarth K. R., Gibala M. J., Heigenhauser G. J. F. (2004). Effects of 7 wk of endurance training on human skeletal muscle metabolism during submaximal exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 97, 2148–2153. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00517.2004

Lin J., Wu H., Tarr P. T., Zhang C.-Y., Wu Z., Boss O., et al. (2002). Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1α drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature 418, 797–801. doi:10.1038/nature00904

Ling C., Poulsen P., Carlsson E., Ridderstråle M., Almgren P., Wojtaszewski J., et al. (2004). Multiple environmental and genetic factors influence skeletal muscle PGC-1α and PGC-1β gene expression in twins. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 1518–1526. doi:10.1172/JCI21889

Lucia A., Gómez-Gallego F., Barroso I., Rabadán M., Bandrés F., San Juan A., et al. (2005). PPARGC1A genotype (Gly482Ser) predicts exceptional endurance capacity in european men. J. Appl. Physiol. 99, 344–348. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00037.2005

Maciejewska A., Sawczuk M., Cieszczyk P., Mozhayskaya I. A., Ahmetov I. I. (2012). The PPARGC1Agene Gly482Ser in Polish and Russian athletes. J. Sports Sci. 30, 101–113. doi:10.1080/02640414.2011.623709

Mägi A., Unt E., Prans E., Raus L., Eha J., Veraksitš A., et al. (2016). The association analysis between ACE and ACTN3 genes polymorphisms and endurance capacity in young cross-country skiers: longitudinal study, 0–8.

Maruszak A., Adamczyk J. G., Siewierski M., Sozański H., Gajewski A., Żekanowski C. (2014). Mitochondrial DNA variation is associated with elite athletic status in the P olish population. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 24, 311–318. doi:10.1111/sms.12012

Massidda M., Flore L., Cugia P., Piras F., Scorcu M., Kikuchi N., et al. (2024). Association between total genotype score and muscle injuries in top-level football players: a pilot study. Sports Med. - Open 10, 22–34. doi:10.1186/s40798-024-00682-z

Mathai A. S., Bonen A., Benton C. R., Robinson D. L., Graham T. E. (2008). Rapid exercise-induced changes in PGC-1α mRNA and protein in human skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 105, 1098–1105. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00847.2007

Michael L. F., Wu Z., Cheatham R. B., Puigserver P., Adelmant G., Lehman J. J., et al. (2001). Restoration of insulin-sensitive glucose transporter (GLUT4) gene expression in muscle cells by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 3820–3825. doi:10.1073/pnas.061035098

Muniesa C. A., González-Freire M., Santiago C., Lao J. I., Buxens A., Rubio J. C., et al. (2010). World-class performance in lightweight rowing: is it genetically influenced? A comparison with cyclists, runners and non-athletes: table 1. Br. J. Sports Med. 44, 898–901. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.051680

Muscella A., Stefàno E., Lunetti P., Capobianco L., Marsigliante S. (2020). The regulation of fat metabolism during aerobic exercise. Biomolecules 10, 1699. doi:10.3390/biom10121699

Okauchi Y., Iwahashi H., Okita K., Yuan M., Matsuda M., Tanaka T., et al. (2008). PGC-1α Gly482Ser polymorphism is associated with the plasma adiponectin level in type 2 diabetic men.

Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ n71, n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

Peplonska B., Adamczyk J. G., Siewierski M., Safranow K., Maruszak A., Sozanski H., et al. (2017). Genetic variants associated with physical and mental characteristics of the elite athletes in the polish population. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 27, 788–800. doi:10.1111/sms.12687

Petr M., Stastny P., Zajac A., Tufano J., Maciejewska-Skrendo A. (2018). The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and their transcriptional coactivators gene variations in human trainability: a systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1472. doi:10.3390/ijms19051472

Pilegaard H., Saltin B., Neufer P. D. (2003). Exercise induces transient transcriptional activation of the PGC-1α gene in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 546, 851–858. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.034850

Richter E. A., Hargreaves M. (2013). Exercise, GLUT4, and skeletal muscle glucose uptake. Physiol. Rev. 93, 993–1017. doi:10.1152/physrev.00038.2012

Russell A. P., Feilchenfeldt J., Schreiber S., Praz M., Crettenand A., Gobelet C., et al. (2003). Endurance training in humans leads to fiber type–specific increases in levels of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-coactivator-1 and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 52, 2874–2881. doi:10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2874

Santiago C., Ruiz J. R., Muniesa C. A., González-Freire M., Gómez-Gallego F., Lucia A. (2010). Does the polygenic profile determine the potential for becoming a world-class athlete? Insights from the sport of rowing. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 20, e188–e194. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00943.x

Senefeld J. W., Hunter S. K. (2024). Hormonal basis of biological sex differences in human athletic performance. Endocrinology 165, bqae036. doi:10.1210/endocr/bqae036

Singh K. P., Miaskowski C., Dhruva A. A., Flowers E., Kober K. M. (2018). Mechanisms and measurement of changes in gene expression. Biol. Res. Nurs. 20, 369–382. doi:10.1177/1099800418772161

Spencer M. R., Gastin P. B. (2001). Energy system contribution during 200- to 1500-m running in highly trained athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 33, 157–162. doi:10.1097/00005768-200101000-00024

Stefan N., Thamer C., Staiger H., Machicao F., Machann J., Schick F., et al. (2007). Genetic variations in PPARD and PPARGC1A determine mitochondrial function and change in aerobic physical fitness and insulin sensitivity during lifestyle intervention. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 1827–1833. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-1785

Steinbacher P., Feichtinger R. G., Kedenko L., Kedenko I., Reinhardt S., Schönauer A.-L., et al. (2015). The single nucleotide polymorphism Gly482Ser in the PGC-1α gene impairs exercise-induced slow-twitch muscle fibre transformation in humans. PLoS One 10, e0123881. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123881

Sun Z., Cięszczyk P., Bojarczuk A. (2025). COL5A1 rs13946 polymorphism and anterior cruciate ligament injury: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 6340. doi:10.3390/ijms26136340

Terada S., Tabata I. (2004). Effects of acute bouts of running and swimming exercise on PGC-1α protein expression in rat epitrochlearis and soleus muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 286, E208–E216. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00051.2003

Tharabenjasin P., Pabalan N., Jarjanazi H. (2019). Association of PPARGC1A Gly428Ser (rs8192678) polymorphism with potential for athletic ability and sports performance: a meta-analysis. PLOS One 14, e0200967. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200967

Valipour M., Nazarali P., Alizadeh R. (2021). Evaluation of frequency of PGC1-α and CKMM genes polymorphisms among iranian elite hockey athletes. Gene Cell Tissue 9. doi:10.5812/gct.117999

Varillas Delgado D., Tellería Orriols J. J., Monge Martín D., Del Coso J. (2020). Genotype scores in energy and iron-metabolising genes are higher in elite endurance athletes than in nonathlete controls. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 45, 1225–1231. doi:10.1139/apnm-2020-0174

Varillas-Delgado D., Morencos E., Gutiérrez-Hellín J., Aguilar-Navarro M., Muñoz A., Mendoza Láiz N., et al. (2022). Genetic profiles to identify talents in elite endurance athletes and professional football players. PLOS One 17, e0274880. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274880

Washington T. A., Haynie W. S., Schrems E. R., Perry R. A., Brown L. A., Williams B. M., et al. (2022). Effects of PGC-1α overexpression on the myogenic response during skeletal muscle regeneration. Sports Med. Health Sci. 4, 198–208. doi:10.1016/j.smhs.2022.06.005

Wasserman D. H. (2009). Four grams of glucose. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 296, E11–E21. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.90563.2008

Wasserman D. H., Kang L., Ayala J. E., Fueger P. T., Lee-Young R. S. (2011). The physiological regulation of glucose flux into muscle in vivo. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 254–262. doi:10.1242/jeb.048041

Westgarth-Taylor C., Hawley J. A., Rickard S., Myburgh K. H., Noakes T. D., Dennis S. C. (1997). Metabolic and performance adaptations to interval training in endurance-trained cyclists. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 75, 298–304. doi:10.1007/s004210050164

Wu Z., Puigserver P., Andersson U., Zhang C., Adelmant G., Mootha V., et al. (1999). Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 98, 115–124. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X

Yu H.-C., Bai L., Jin L., Zhang Y.-J., Xi Z.-H., Wang D.-S. (2025). SLC25A35 enhances fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis to promote the carcinogenesis and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma by upregulating PGC-1α. Cell Commun. Signal. 23, 130. doi:10.1186/s12964-025-02109-y

Yvert T., Miyamoto-Mikami E., Murakami H., Miyachi M., Kawahara T., Fuku N. (2016). Lack of replication of associations between multiple genetic polymorphisms and endurance athlete status in japanese population. Physiol. Rep. 4, e13003. doi:10.14814/phy2.13003

Keywords: athletic performance, endurance athletes, polymorphism, power athletes, PPARGC1A, sport genetics

Citation: Su W, Yuan L, He Z, Ding F, Sun J, Xiong Y and Song X (2026) Association between the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser (rs8192678) polymorphism and endurance and power athlete status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 16:1733458. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1733458

Received: 27 October 2025; Accepted: 15 December 2025;

Published: 07 January 2026.

Edited by:

Liang Zhang, Wuhan Sports University, ChinaReviewed by:

Sulev Kõks, Murdoch University, AustraliaHiroki Homma, Japan Institute of Sports Sciences (JISS), Japan

Copyright © 2026 Su, Yuan, He, Ding, Sun, Xiong and Song. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaobo Song, c29uZ3hiQGNjbnUuZWR1LmNu

Weilong Su

Weilong Su Lingfeng Yuan2

Lingfeng Yuan2 Yingzhe Xiong

Yingzhe Xiong