- Department of Psychology, Chemnitz University of Technology, Chemnitz, Germany

Introduction: The current social zeitgeist is characterized different feminist tendencies, some of which are embedded in a neoliberal logic. Although the impact of modern mainstream feminism on the individual and society is a subject of critical scholarly debate, there is a lack of suitable instruments to measure the complexity of modern feminist attitudes.

Methods: In three studies, we developed a scale assessing liberal feminist attitudes and tested its factor structure and validity. In Study 1, we generated an item pool capturing liberal feminist attitudes and presented it to a sample of N = 473 with scales for Ambivalent Sexism (hostile and benevolent), Social Dominance Orientation, System Justification, Neoliberal Beliefs, and the self-labeling as a feminist. In Studies 2 (N = 310) and 3 (N = 214) we aimed at replicating the factor structure of the LFAS from Study 1 and confirmed the construct and criterion validity with measurements of the constructs Self-Identification as a Feminist, Personal Progress, Conformity to Feminine Norms and a concrete behavioral measure that captured the willingness to receive information about feminism in the future.

Results: Exploratory factor analysis (Study 1) yielded a 4-factor structure with 17 items-the Liberal Feminist Attitudes Scale (LFAS). In Studies 2 and 3, this 4-factorial model showed excellent model fit, internal consistency and convergent as well as discriminant and criterion validity, at least within a particular demographic (i.e., German students).

Discussion: The LFAS holds the potential to provide psychologists with a tool to examine and analyse liberal feminist attitudes comprehensively.

Introduction

Despite increasing changes in gender roles, the achievements of the women's rights movement over the last 100 years and the enshrinement in law of equal treatment irrespective of gender, true gender parity remains elusive (United Nations, 2022). Poverty, violence, discrimination in employment, and the disproportionate responsibility for domestic work and family care are persistent barriers to girls' and women's freedom and autonomy.

In response to this persistent gender disparity, the feminist movement advocates for enhanced political, economic, and social engagement. Defined by the Cambridge Dictionary (2022) as “the belief that women should be allowed the same rights, power, and opportunities as men and be treated in the same way or set of activities intended to achieve this state,” feminism manifests across a spectrum of inclinations, encompassing concerns of self-determination, labor participation, education, intersectionality, and contextual variations within diverse cultural, regional, and social milieus.

A feminist identity and beliefs are beneficial for girls and women both as individuals and in their interpersonal relation (Moradi and Yoder, 2011). However, the empirical landscape presents a disparity in demonstrating the affirmative influence of feminism, largely attributable to the variability in measurement methodologies employed to gauge feminist attitudes and identities. These incongruities arise from ambiguities in defining distinct feminist movements, coupled with psychometric challenges intrinsic to the assessment instruments (Liss and Erchull, 2010; Siegel and Calogero, 2021).

Researching feminism's impact is complicated by numerous authors revealing people's avoidance of the “feminist” label, despite valuing gender equality (McCabe, 2005; Bay-Cheng and Zucker, 2007). Concurrently, the mainstreaming of feminism is accompanied by stagnation in the efficacy of gender equity demands (Rottenberg, 2014; Scarborough et al., 2018). To study these evolving societal dynamics and their impact on individuals, particularly women, an explicit and dependable measurement tool is imperative. In response, we present the Liberal Feminist Attitudes Scale. This measurement instrument allows, in contrast to previous measurement tools, the capturing of feminist attitudes as a complex interplay between system-critical and individualistic beliefs. In this way, it provides a foundation for the exploration of processes of social change in a world that, despite increasing liberalization, rejection of traditional gender stereotypes, and advocacy for egalitarian norms, struggles in implementing social justice.

Defining (liberal) feminism

Feminism has changed drastically in recent decades, while its fundamental mission of combating sexist oppression has remained constant over time (Hooks, 1984). The feminist landscape comprises key tendencies, including liberal, radical, and socialist feminism, which have evolved substantially over the past 20 years (Donovan, 2012). New challenges of so-called Fourth Wave Feminism stem from the diverse cultural, socio-political, and historical contexts and form a wide variation of beliefs and principles that constitute feminist identity and attitudes. The intricate dynamics of contemporary feminist perspectives defy a singular, cohesive category of “feminism” (Ehlers, 2016). Since liberal feminism—especially through its outgrowths in pop culture—enjoys broad social approval and can most readily be considered the mainstream of the various feminisms (Rottenberg, 2014; Ehlers, 2016; Zhang and Rios, 2021), we assume that the general lay understanding of feminism in the Western world is predominantly based on liberal feminist principles and is therefore most suitable for examining socio-political and individual effects and changes.

Since the late 1960's, critiques of liberal feminism have centered on the gender exclusions that persist within the framework of universal equality propagated by liberal democracy. This critique seeks to integrate women into the “citizen” category, encompassing civil rights, equal opportunities, access to institutions, and education as agents of social change (Rottenberg, 2014; Zhang and Rios, 2021). The advocacy is for women to resist limited, demeaning roles such as wife, mother, and object of male desire, and to highlight how gendered socialization constrains women's economic and political progress (Rottenberg, 2014).

In distinction to other feminist theories, according to liberal feminism, women's political emancipation is in the “equality” of the sexes or in the elimination of unfavorable gender differences and thus in the minimization of gender difference itself (Zhang and Rios, 2021). Behind this is an open concept of gender neutrality that follows a social constructivist perspective and assumes that gender and role conceptions are constructed in historical contexts rather than in being biologically determined (Baber and Tucker, 2006). The demand for equality regardless of gender involves an open, non-specifically defined concept of gender that refers to both biological sex and gender identity, as well as to freely chosen social roles and life goals. Making intersectionality visible is pushed into private space and not specified within liberal feminist claims.

Capturing feminism: challenges and complexities

Over the past 50 years, measurement instruments have been developed to capture different feminist constructs in quantitative research (for an overview, see Frieze and McHugh, 1998; Siegel and Calogero, 2021). But in the light of rapidly developing and multiplying feminist, they can at best be considered a snapshot in time and give rise to the development of a contemporary and reliable scale. A difficulty in operationalizing feminism stems from the conflation of feminist attitudes and feminist identity. Feminist attitudes are defined as beliefs in the feminist goal of gender equality in social structures and practices (Zucker, 2004). Meanwhile, feminist identity is construed as a collective or social identity, necessitating self-identification as a group member (Ashmore et al., 2004). Thus, the definition of feminist identity includes both the adoption of feminist attitudes and Self-Identification as a Feminist (Zucker, 2004), with explicitly feminist self-identification being a prerequisite for feminist identity (Ashmore et al., 2004).

Zucker (2004) proposes the separation between feminists, who endorse feminist values and claimed a feminist identity; non-feminists, who reject both feminist values and identities, and egalitarians, who endorse feminist values yet reject a feminist identity. Based on Self-Categorization Theory (Turner et al., 1987), several researchers emphasize that individuals might hold feminist-oriented viewpoints but avoid identifying and labeling themselves as feminists, often due to negative stereotypes linked to feminism (Bay-Cheng and Zucker, 2007).

A paradoxical facet of feminism emerges despite its mainstream status, the potency of the gender equality agenda weakens within post-feminist and neoliberal narratives (Scarborough et al., 2018; Girerd and Bonnot, 2020). Gill (2007) alludes to a pervasive “postfeminist sensibility” in contemporary culture. Postfeminism, not only created and propagated, but also assimilated and replicated through media enables a feminist identity choice devoid of backing or comprehension of modern feminist principles (Gill, 2016; Moon and Holling, 2020). Such an identity, rooted in a post-feminist ideology, intertwines feminist and anti-feminist beliefs, buoyed by neoliberal tenets of self-determination, meritocracy, and individualism.

Furthermore, the post-feminist wave fosters the notion, particularly among young women, that feminism is irrelevant, antiquated, and out of touch with their lives (Girerd and Bonnot, 2020). Feminist self-identification correlates with perceptions of the women's movement's impact and the genesis of gender (in)equality (McCabe, 2005). In contrast to mere feminist attitudes, a strong affiliation with feminists influences active engagement in feminist actions (Szymanski, 2004; Nelson et al., 2008), readiness to combat sexist behaviors in daily life (Weis et al., 2018), and participation in a spectrum of feminist behaviors (e.g., supporting feminist charities, discussing feminist topics; Redford et al., 2016). The advantages of a feminist identity emanate not solely from feminist beliefs, but from perceiving oneself as a feminist. This identification forms a politicized dimension of identity, mirroring attitudes toward the group's societal status concerning disadvantage, inequality, and prestige (van Breen et al., 2017).

Overview of existing measurement methods

Despite the social and individual relevance of feminist perspectives, their changing dynamics and differentiation, all scales developed so far that claim to “measure feminism” show serious psychometric and content-related limitations, which we present here as examples for the most frequently cited scales. Early scales such as the Belief Pattern for Measuring Attitudes Toward Feminism (BSMATF; Kirkpatrick, 1936), the Attitudes Toward Women Scale (AWS; Spence et al., 1972) and the Fem Scale (Smith et al., 1975) capture attitudinal beliefs about gender roles, but neither feminist identity nor feminist attitudes. Other scales, such as the Attitudes Toward Feminism Scale (ATFS; Fassinger, 1994) and the Feminism and Women's Movement Scale (FWM; Fassinger, 1994), while based on feminist ideology, are designed solely to capture attitudes toward the feminist movement and are thus more restrictive in scope.

The Feminist Identity Development Scale (FIDS; Downing and Roush, 1985), the Feminist Identity Scale (FIS; Rickard, 1989) and its development, the Feminist Identity Composite (FIC; Fischer et al., 2000) map attitudes to gender roles as part of feminist identity and, borrowing from existing developmental theories such as Black Identity Development (Cross, 1971), serve as measures of the feminist concept of identity. However, the derivation of Black political identity development cannot be fully applied to feminist identity (Hyde, 2002; Moradi and Subich, 2002). Moreover, the scales do not map the incongruence of women who display high levels of self-empowering attitudes (and thus belong to a high level of the FIDS model) but reject a feminist identity (Erchull et al., 2009).

The Liberal Feminist Attitudes and Ideological Scale (LFAIS; Morgan, 1996) capitalizes on identifying socio-political congruities in feminist thought, often neglected by earlier scales (Siegel and Calogero, 2021). However, its conceptualization of “feminism” remains vague, lacking specificity in defining liberal feminism and leading to content inconsistencies such as neglecting individualistic tendencies. A similar critique applies to the Feminist Perspective Scale (FPS; Henley et al., 1998, 2000), designed to gauge varying degrees of feminist ideologies but unsuitable for assessing feminist identity and action.

For simplicity and broad applicability, the Self-Identification as a Feminist Scale (SIF; Szymanski, 2004) and the Cardinal Beliefs of Feminists Scale (CBF; Zucker, 2004) stand out. Nonetheless, the SIF overlooks the underlying content of feminist identity, while the yes/no response format of the CBF hampers the assessment of attitude strength (Siegel and Calogero, 2021). The analysis underscores the pressing need for a comprehensive and robust measurement tool that accurately captures contemporary feminist attitudes and identity.

The present studies

In this paper we develop a new instrument to capture liberal feminist attitudes—the Liberal Feminist Attitudes Scale—over three stages: (1) item pool generation and exploratory factor analysis (EFA; Sample 1); (2) confirmatory factor analyses to confirm the factor structure found in Study 1 (CFA; Sample 2 and Sample 3; H1 and H2); and (3) assessment of the final scale's internal consistency and validity (all three samples; H3 to H17).

Regarding convergent validity, we expect positive correlations to the already established and frequently used measure for feminist identity, the SIF (Szymanski, 2004; H3) and to the self-labeling as a feminist (H4). The LFAS should correlate positively with personal growth and empowerment (H5), as feminist attitudes as a form of women-centered intervention can help women acquire skills and resources to better cope with future stress and trauma, as well as become more independent and confident to achieve their goals and make changes (Johnson et al., 2005).

Theories and findings from various disciplines suggest negative correlations with the hierarchy-supporting constructs of (gender-specific) System Justification (H6; H7) and Social Dominance Orientation (H8), as feminist ideology is based on awareness of social inequality and critique of the current gender system that is disadvantageous to women. SDO is positively associated with opposition to gender-based affirmative action (Fraser et al., 2015), with higher skepticism about women's professional employment due to an assumed lack of skills (Christopher and Wojda, 2008), predicts various types of sexism (Sibley et al., 2007; Asbrock et al., 2010), and negative attitudes toward women in leadership positions (Manganelli et al., 2012). Ambivalent sexism perpetuates the gender imbalance between men and women through hostile and benevolent sexist attributions, discriminates against women as lower status groups, justifies male supremacy (Glick and Fiske, 1996) and should therefore also correlate negatively with LFAS as it serves to legitimize gendered power relations (H9; H10).

The neoliberal position is a meritocratic, post-racist and post-feminist one that assumes that institutionalized discrimination has been largely eradicated. Bay-Cheng et al. (2015) found a moderate negative correlation between neoliberal attitudes and perceptions of sexism, a high positive correlation with acceptance of rape myths, and a moderate to high negative correlation with feminist attitudes as measured by the FPS (Henley et al., 1998). Furthermore, Girerd and Bonnot (2020) found evidence that endorsement of neoliberal beliefs was related to stronger justification of the gender system, lower feminist identification and lower collective action in favor of women, which leads us to assume a negative correlation between neoliberal attitudes and the LFAS (H11).

Women's conformity to dominant cultural norms of femininity has significant implications for psychological wellbeing and health (Parent and Moradi, 2011) and is associated, for example, with lower levels of aggression (Reidy et al., 2009), greater pursuit of leanness and eating disorders (Smolak and Murnen, 2008) and mediates the association of feminist self-identification and higher self-esteem including lower body image, eating disorder symptoms and depression (Hurt et al., 2007). Acceptance of the status quo, which is disadvantageous to women, is associated with lower expectations of egalitarian intimate relationships and lower sexual self-esteem (Yoder et al., 2007). Feminist beliefs moderate the relation between media awareness and internalization of thinness ideals (Myers and Crowther, 2007), are positively related to sexual wellbeing (Schick et al., 2008) and sexual openness (Bay-Cheng and Zucker, 2007). In addition, women exposed to a feminist perspective showed higher satisfaction with physical appearance (Peterson et al., 2006), so we assume negative associations between the LFAS and conformity to female norms in terms of desire to be thin (H12), investment in appearance (H13), romantic relationships (H14), and sexual fidelity (H15).

In sexism research, gender differences in mean scale scores are seen as an additional indication of the construct validity of a scale (McHugh and Frieze, 1997). Men should score higher on average than women. For feminism research, the opposite can be assumed, as women are more likely to agree with feminist attitudes (H16; Fitz et al., 2012). Finally, we expect liberal feminist attitudes to correlate positively with women's willingness to receive information about future feminist actions (H17). The hypotheses for Study 1 and 3 are pre-registered in the Open Science Framework and can be found with all materials and data under: https://osf.io/mv473/?view_only=499d37eca35546729394661e413fde3b.

Study 1

Method

Participants and procedures

The study included 473 German adults between the ages of 18 and 68 (M = 31, SD = 10) recruited from December 2020 to January 2021 through various channels: the student mailing list of Chemnitz University of Technology, social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram), and Survey Circle. Participants engaged in an online survey titled “Attitudes toward gender equality and social coexistence in Germany.” Inclusion criteria were age of at least 18 years, proficient knowledge of German, and completion of the full questionnaire. Unless specified, responses were given on randomized 7-point Likert scales.

In a demographic analysis conducted on the survey participants, it was observed that 73.8% identified themselves as female, 24.1% identified as male, and 2.1% indicated their gender as “other.” Regarding educational qualifications, 46.2% of the respondents reported a university degree and a university entrance diploma as their highest academic attainment, while 4.4% mentioned a secondary school certificate. Notably, four individuals refrained from disclosing their age, and two individuals did not provide information about their educational background.

Measures

Item Development of the Liberal Feminist Attitudes Scale (LFAS)—The item pool for the LFAS was created through the German translation and adaptation of the LFAIS items (Morgan, 1996), the SRQ items (Social Role Questionnaire, Baber and Tucker, 2006) as well as based on multidisciplinary literature dealing thematically with the construct “liberal feminism.” Newly generated items were added to the translated items of the LFAIS and the SRQ, which were selected according to their topicality, and the item pool was corrected several times to eliminate possible redundancies and to consolidate content-related foci based on existing literature. This critical, iterative process resulted in an item pool of 42 items that, for the sake of clarity, were assigned to the theoretically assumed core themes of liberal feminism—gender roles and gender, feminist ideology, social and economic participation, and self-empowerment.

Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI)—Ambivalent sexism was measured with the 22 items of the German version (Eckes and Six-Materna, 1999) of the ASI (Glick and Fiske, 1996).

System Justification (SJ) and gender-specific System Justification (SJG)—To assess System Justification (Jost et al., 2004), participants answered the German version (Ullrich and Cohrs, 2007) with eight items and the German version of the gender-specific System Justification (Jost and Kay, 2005; Becker and Wright, 2011) with six items.

Social Dominance Orientation (SDO)—Social Dominance Orientation (Ho et al., 2012) was assessed in the German translation (Carvacho et al., 2018) with 16 items.

Neoliberal beliefs Inventory (NBI)—Neoliberal beliefs were assessed via the NBI (Bay-Cheng et al., 2015) in the German version (Völkel, 2019) via 25 items.

Self-Identification as a feminist (SISI)—Self-Identification as a Feminist was assessed using the Single-item Measure of Social Identification (Postmes et al., 2012). Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the item.

Results and discussion

Preliminary item analyses, exploratory factor analyses, and internal consistency

For an exploratory factor analysis, it is commonly advised to have at least 10 participants per item (Yong and Pearce, 2013). With an item Pool of 42 items measuring liberal feminist attitudes, our target sample size was N = 420. The items selected tended to have high item variance, medium item difficulty and high discriminatory power. Items with a medium difficulty between 80 ≤ Pi ≤ 20 are most likely to produce clear differentiations between subjects with high and low trait expression (Moosbrugger and Keleva, 2012). Items with difficulty indices of 5 ≤ Pi ≤ 20 or 80 ≤ Pi ≤ 95 were also included in the further calculation if the discriminatory power was sufficiently high (rit = 0.4 to rit = 0.7). Items with a discriminatory power close to zero or in the negative range were excluded. At the same time, the theoretical breadth of the construct was considered in the item selection and the item “Men are more sexually active than women.” (i) was retained despite a low discriminatory power of rit = 0.22. The remaining item pool on this basis comprised 35 items. The original German wording, the item-analytical parameters and the descriptive statistics of the items are reported in the Supplementary Table 1.

For further reduction of the item pool and to obtain clues about the factorial structure of the selected items, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) based on principal axis analysis with promax rotation using jamovi (Version 1.6) [Computer Software]. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) revealed a high level of shared variance (MSA = 0.94) for the 35 items and Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant [ = 6,589.00, p < 0.001], indicating that the data met the assumptions of multivariate normality and were appropriate for factor analysis (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). Two additional items with a low MSA score below 0.6 were dropped. Factor selection was based on parallel analysis, scree plots and factor interpretability. Factors containing fewer than three items were excluded.

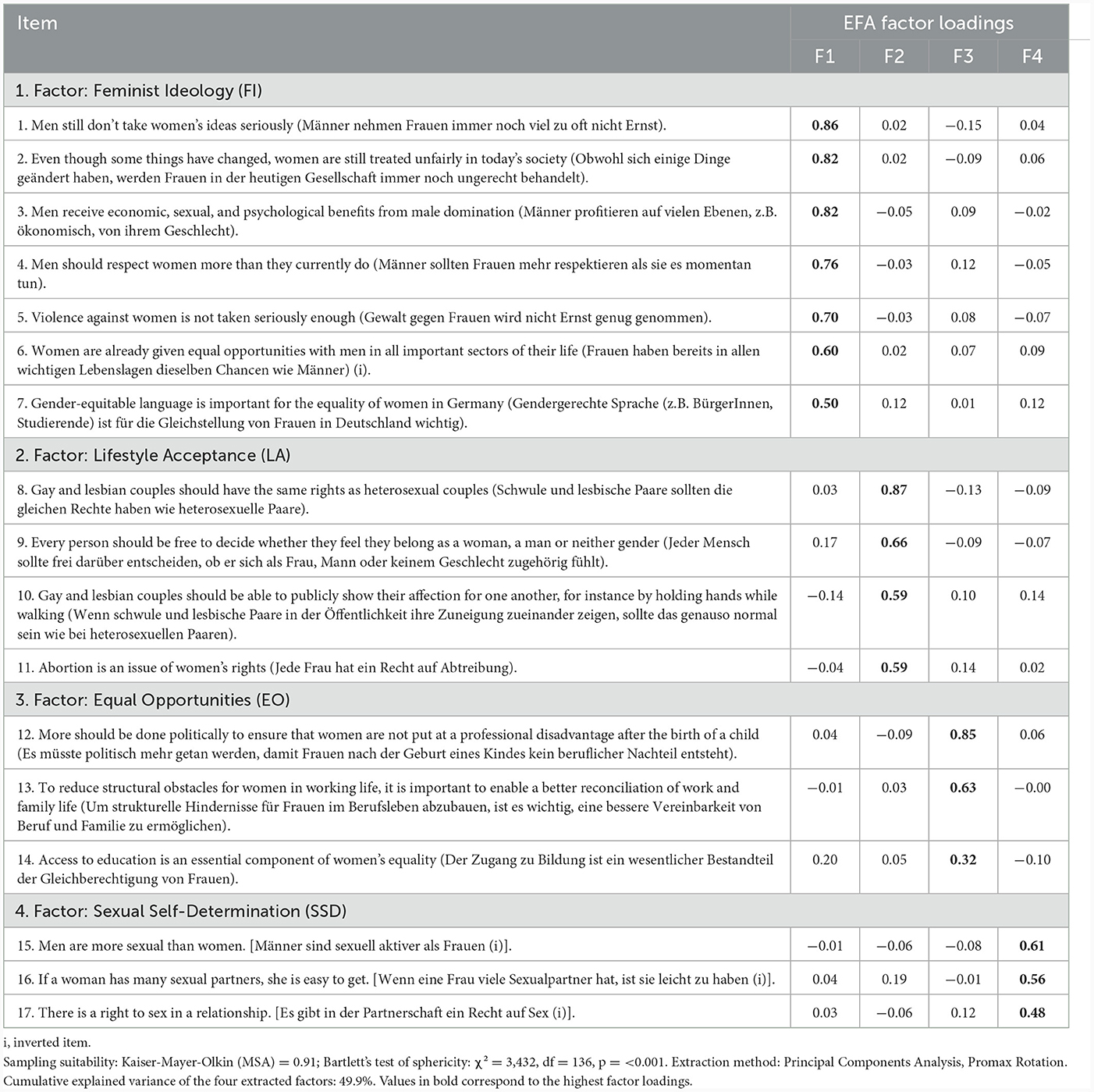

The parallel analysis for factor selection resulted in a model with five factors. This model explained 41% of the variance, resulted in partially low factor loadings of < 0.4 and revealed conceptual difficulties that made the interpretation of the factors difficult. As an additional approach to determining the number of factors, the scree plot (Supplementary Figure 1) of the data was examined, which indicated a four-factor solution. These four factors were conceptually discrete. For this reason, a four-factor solution was adopted, retaining items with factor loadings of 0.50 and above. Items that loaded on more than one factor were discarded if the difference between the loadings was < 0.10 (Kahn, 2006). In addition to these statistical criteria, the conceptual validity of the factors and their associated items was examined. On this basis, one item was retained with a factor loading of 0.32 for the third factor and one item with a factor loading of 0.48 for the fourth factor. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) again revealed a high level of shared variance (MSA = 0.91) for the 17 items and Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant [ = 3,432, p < 0.001]. The results of EFA for four factors with 17 items (in German original wording and in English translation) are presented in Table 1. The correlation matrix of the 17 items can be found in the Supplementary Table 2.

The resulting LFA scale (LFAS) thus comprised 17 items loading on four factors. The four factors were given the following labels: Feminist Ideology (FI, i.e., recognition of discrimination and need for equality), Lifestyle Acceptance (LA, in the sense of an open gender concept), Equal Opportunities (EO, i.e., economic, and social participation) and Sexual Self-Determination (SSD). Except for the fourth factor, these factors were similar to the main themes that emerged for liberal feminist attitudes from the literature review. Feminist Ideology explained 23.8%, Lifestyle Acceptance 11.65%, Equal Opportunity 8.32%, and Sexual Self-Determination 6.13% of the variance in the data. In total, these four factors explain 49.9 % of the variance.

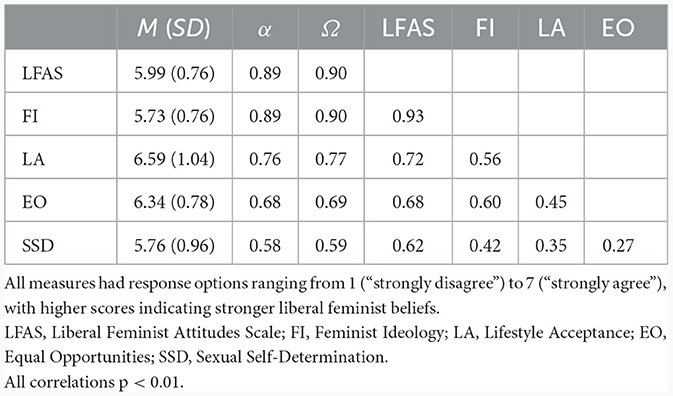

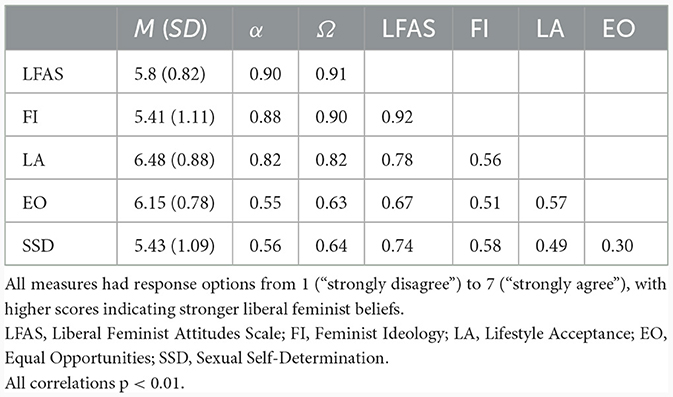

For the LFAS, there was good/excellent internal consistency. The internal consistencies of the subscales were excellent to acceptable with lower internal consistency for the EO and SSD. However, due to the small number of items, this can still be considered acceptable, and it can be assumed that the SSD factor also results from the lower factor loading discriminatory power of the item 15. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics, Cronbach's alpha, McDonald's omega and correlations of the LFAS and its subscales for Study 1.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, internal consistency, and correlation of the four factors of the LFAS (Study 1).

Discriminant and convergent validity

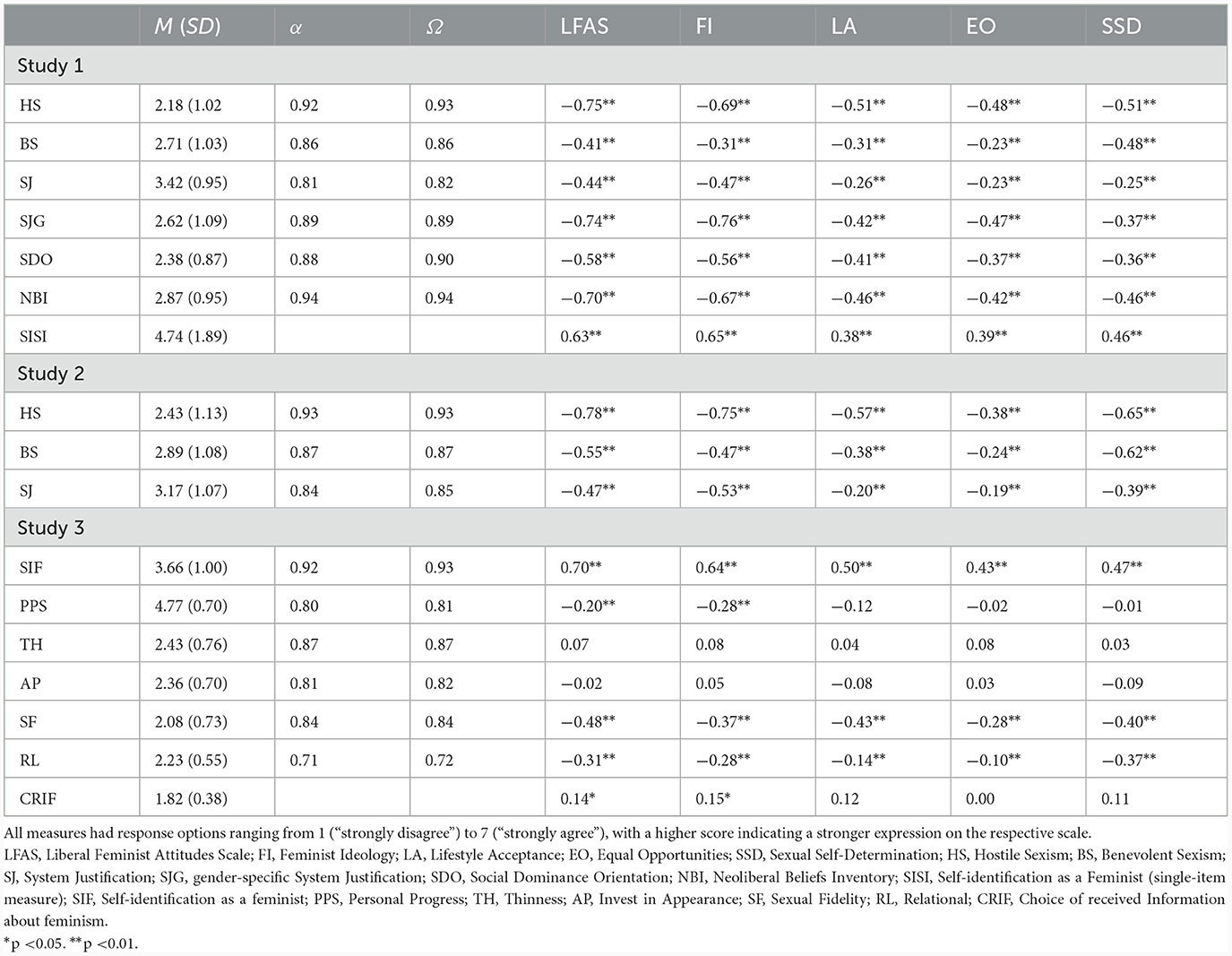

LFAS correlated negatively and highly with hostile sexism (H9), gender-specific System Justification (H6), Social Dominance Orientation (H8), and neoliberal beliefs (H11), according to Cohen's (1988) conventions. The correlations between LFAS and benevolent sexism (H10) and System Justification (H7) were moderately negative and supported our hypotheses. The Convergent validity was confirmed by a high positive correlation (H4) between LFAS and self-identification as a feminist.

A sensitivity power analysis with G*Power (Faul et al., 2009), indicated the study's ability to detect a small effect size (r = 0.13) with a power of 80%. The correlations of the LFAS with the validation constructs as well as the descriptive statistics and the internal consistency of the measurement instruments are shown in Table 3. The correlation matrix of the validation constructs from Study 1 can be found in the Supplementary Table 3.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics, internal consistency, and correlations among validity constructs and the LFAS (Study 1, Study 2, and Study 3).

Group differences

As we expected (H16), women scored significantly higher than men on the LFAS [M = 6.09, SD = 0.64; M = 5.63, SD = 0.96; t(146) = 4.79, p < 0.001] and the subscales Feminist Ideology [M = 5.84, SD = 0.89; M = 5.3, SD = 1.33; t(146) = 4.02, p < 0.001], Lifestyle Acceptance [M = 6.66, SD = 0.66; M = 6.33, SD = 0.98; t(147) = 3.33, p = 0.001], Equal Opportunities [M = 6.42, SD = 0.66; M = 6.07, SD = 1.05; t(142) = 3.33, p = 0.001], and Sexual Self-Determination [M = 5.83, SD = 0.95; M = 5.48, SD = 1.1; t(171) = 3.02, p = 0.003], suggesting that liberal feminist attitudes are of greater importance to women. Cohen's d effect size revealed a medium effect for the LFAS (d = 0.57) and the FI subscale (d = 0.48), and a small effect for the LA (d = 0.39), EO (d = 0.4), and SSD (d = 0.34) subscales. Descriptives and differences between women and men on the LFAS and its subscales can be found in the Supplementary Table 4.

In Study 2 we examined the factor structure with a CFA and repeated the validity analyses.

Study 2

Method

Participants and procedures

Study 2 (N = 310) was recruited from July to August 2021 via the mailing list of Chemnitz University of Technology as well as social media platforms, whereby it was pointed out that people should only participate if they had not already taken part in Study 1. Participants had to be at least 18 years old and have sufficient knowledge of German to complete a survey subtitled “Attitudes toward menstruation, equality and society.” Examining participants aged 18 to 70 (M = 31.1; MD = 11.7), 78% identified as female, 20.1% as male, and 1.9% as “other.” A university degree was held by 48.8% of the sample, 42.5% had a university entrance diploma, and 9.2% a secondary school diploma.

Measures

Liberal Feminist Attitudes Scale (LFAS) was measured with the 17-item scale developed in Study 1. Ambivalent Sexism (ASI) and System Justification (SJ) were measured with the same items as in Study 1.

Results and discussion

Confirmatory factor analyses and internal consistency

Using RStudio Team (2020) with lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012), we conducted a CFA with the 17 items of the LFAS. In agreement with the EFA results, we hypothesized four latent factors representing the four subscales Feminist Ideology, Lifestyle Acceptance, Equal Opportunity, and Sexual Self-Determination, which were allowed to correlate with each other. The size of sample 2 (N = 310) exceeded the recommended minimum for CFA (Myers et al., 2011), increasing the accuracy of the models and the fit indices.

Absolute model fit was assessed using root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized mean residual (SRMR). We also tested incremental model fit using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis index (TLI) and the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) as absolute measures. We did not use chi-square because it is less informative for models with comparatively large samples (Kenny, 2014). Following Weston and Gore (2006), we used RMSEA and SRMR ≤ 0.10, and for GFI, TLI and CFI ≥0.90 as standards for acceptable fit. To compare the goodness of fit across different models, we ran chi-square difference tests (Bollen, 1989).

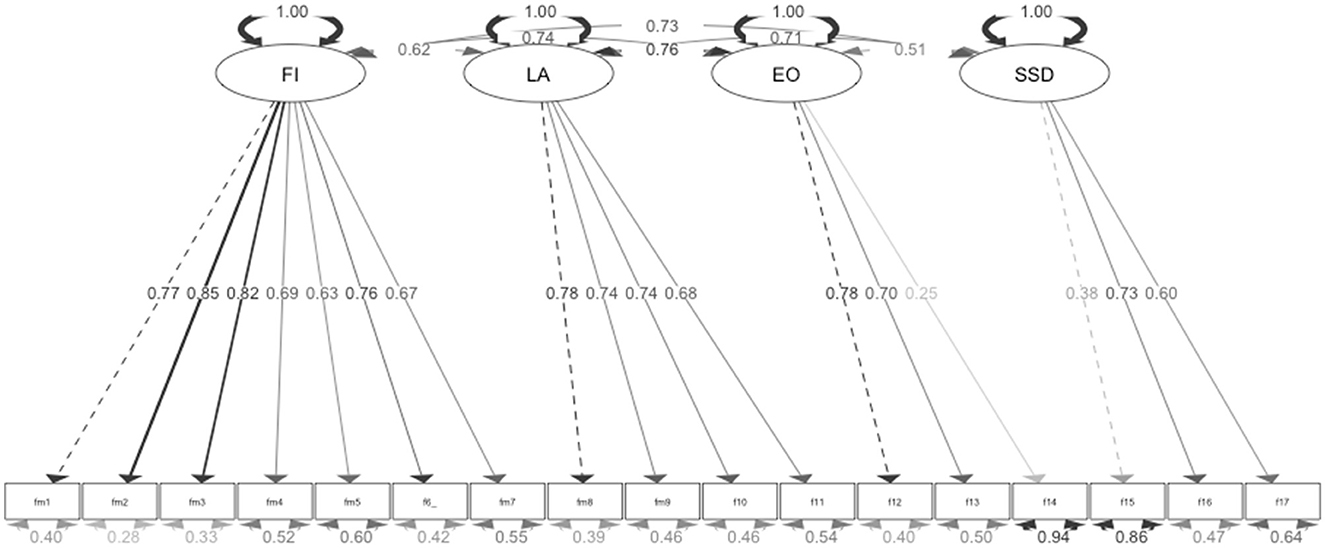

The four-factor model provided a good fit to the data (H1): RMSEA = 0.075 (90% CI [0.065, 0.085]), SRMR = 0.051, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.9, GFI = 0.90. The loadings of the items on the latent factors were significantly different from zero and within a satisfactory range (see Figure 1). Two items showed low standardized factor loadings of 0.25 (item 14: “Access to education is an essential component of women's equality”) and 0.38 [item 15: “Men are more sexually active than women” (i)]. The conspicuously low factor loading of item 14 within factor Equal Opportunities could be due to the homogeneous, western, and predominantly student sample, for whom educational inequality is not a relevant demand within liberal feminist attitudes and is already considered to have been overcome. For item 15 of factor Sexual Self-Determination, the item wording could be a reason for the low loading, as this item asks for a perception rather than an attitude. Respondents might agree more or less with the item based on their everyday observations, irrespective of whether they view this issue positively or negatively. Both items were excluded within another CFA [RMSEA = 0.081 (90% CI [0.070, 0.093]), SRMR = 0.049, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, GFI = 0.91; χ2(1)diff = 53.73, p < 0.01]. However, this third model showed little relevant change in terms of model fit, so we retained both items to represent as wide a range of content as possible. A unidimensional model, with all items loading on a single latent factor, showed poor fit, RMSEA = 0.12 (90% CI [0.11, 0.13]), SRMR = 0.079, CFI = 0.79, TLI = 0.78, GFI = 0.78. The 4-factorial model fitted the data significantly better than the unidimensional model, χ2(1)diff = 310.75, p <0.001.

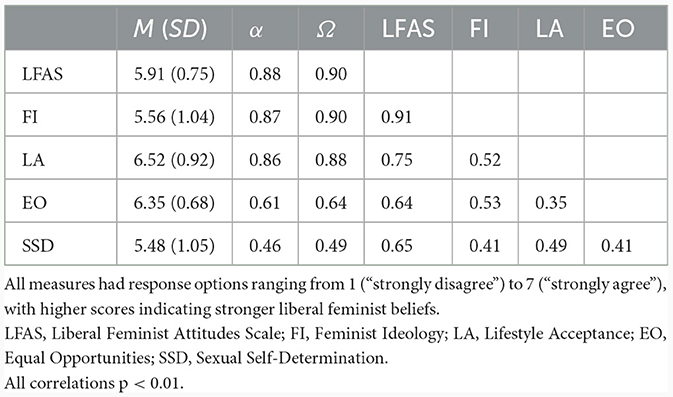

There was excellent internal consistency for the LFAS. The values found for the subscales were excellent to acceptable. Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics, Cronbach's alpha, McDonald's omega and correlations of the LFAS and its subscales for Study 2.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics, internal consistency, and correlation of the four factors of the LFAS (Study 2).

Discriminant validity

As expected, LFAS and all subscales correlated negatively with Hostile Sexism (H9), Benevolent Sexism (H10), and System Justification (H7). A sensitivity power analysis with G*Power (Faul et al., 2009), indicated the study's ability to detect a small effect size (r = 0.16) with a power of 80%. Correlations and descriptive statistics are shown in Table 3. The correlation matrix of the validation constructs from Study 2 can be found in the Supplementary Table 5. We excluded item 14 and item 15 for the correlation analyses but found no notable changes in effect sizes (Supplementary Table 6).

To avoid the gender effect found in Study 1, we focussed on a female sample in Study 3. In addition, in Study 3 we re-examined the factor structure through CFA, conducting extended validity analyses.

Study 3

Method

Participants and procedures

The sample comprised a total of N = 214 female participants, 114 aged between 18 and 57 (M = 23.5; SD = 0.7) of whom were collected through the mailing list of the same university as in Studies 1 and 2, and 100 German-speaking participants aged between 18 and 69 (M = 48.5; SD = 16.5) through Prolific. Thirty-four percentage of the total sample held a university degree, 60.5% a university entrance diploma, and 5.1% a secondary school certificate. Participants were asked to complete an online survey entitled “Women's attitudes toward gender equality.” If not otherwise stated, the items were answered in randomized order on 7-point Likert scales. Excluded were people who did not answer the control item correctly, did not identify their gender as female, were not at least 18 years old, had already participated in Study 1 or 2 and/or did not have sufficient knowledge of German, as well as incomplete questionnaires.

Measures

Liberal Feminist Attitudes Scale (LFAS) was measured with the 17-item scale developed in Study 1.

Personal Progress Scale Revised (PPS-R)—To assess personal empowerment in women, the PPS-R (Johnson et al., 2005) was translated into German and recorded with a total of 17 items.

Self-Identification as a Feminist (SIF)—The participants were presented with the four items of the SIF (Szymanski, 2004), translated into German, with a 5-point Likert scale.

Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory−45—The CFNI-−45 (Parent and Moradi, 2010) statements are designed to measure attitudes, beliefs and behaviors associated with both traditional and non-traditional female gender roles. We used four of the total nine subscales (Thinness, Invest in Appearance, Relational and Sexual Fidelity) with five items each and presented them to the participants in with a 4-point Likert scale.

Results and discussion

Confirmatory factor analyses and internal consistency

Following the recommendation of Myers et al. (2011), we maintained a sample size of at least 200 participants. The CFA confirmed the 4-factor structure (H2): RMSEA = 0.078 (90% CI [0.066, 0.091]), SRMR = 0.07, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.90, GFI = 0.87. Item 14 and item 15 showed low factor loadings of 0.28 and 0.25, as in Study 2. We therefore tested the 4-factor model excluding the two items and obtained slightly changed measure fits, RMSEA = 0.080 (CI [0.066, 0.094]), SRMR = 0.073, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, GFI = 0.88, χ2(1)diff = 62.96, p < 0.001, so that we decided to keep the two items for content reasons. The remaining items had satisfactory factor loadings between 0.49 and 0.94 (for the detailed factor loadings see in the Supplementary Table 7. We also tested a one-factor model, but this model fitted the data worse than the 4-factor model, RMSEA = 0.12 (CI [0.14, 0.16]), SRMR = 0.1, CFI = 0.68, TLI = 0.64, GFI = 0.71, χ2(1)diff = 410.1, p < 0.001.

The internal consistency can be rated as excellent to good for the LFAS and excellent to unacceptable for the subscales. Unacceptable values regarding internal consistency for the SSD subscale could, on the one hand, be due to the small number of items. On the other hand, the removal of the items in the case of item 15 led to an improvement in internal consistency (α = 0.50; Ω = 0.50), which—as in Study 1 and Study 2—could be due to the low discriminatory power and/or the unfavorable item formulation. The mere finding of gender-specific differences—as is the case with item 15—regarding sexual activity says little in terms of content about the individual attitude toward sexual self-determination. Items 16 (α = 0.24; Ω = 0.24) and 17 (α = 0.33; Ω = 0.33), on the other hand, worsened the internal consistency values, which is why we assume that they are important for measuring the construct SSD. Table 5 shows the descriptive statistics, Cronbach's alpha, McDonald's omega and the correlations of the LFAS and its subscales.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics, internal consistency, and correlation of the four factors of the LFAS (Study 3).

Convergent, discriminant, and criterion validity

As we expected, convergent validity was assessed through correlations with the self-identification as a feminist (H3). The SIF correlated strongly positively with the LFAS. Personal progress, contrary to our expectation (H5), interestingly correlated weakly negatively with both the LFAS and the SIF. Discriminant validity was confirmed for the Sexual Fidelity (H15) and Relational (H14) subscales of the CFNI-45. However, we found no correlation between LFAS and the subscales Thinness (H12) and Investment in Appearance (H13), which focus on the idealized female body.

Finally, the LFAS as well as the Feminist Ideology subscale correlated positively with willingness to receive information about feminist actions in the future, confirming our hypothesis (H17). The LA, EO and SSD subscales either did not correlate with willingness to receive information or the correlation was not significant. The Feminist Ideology dimension seems to be the basis for the specific behavioral measure here. This confirms our theoretical assumptions that FI is to be seen as the core of all feminist tendencies and takes a society-wide focus, while the dimensions LA, EO and SSD rather reflect an individual perspective within liberal feminist attitudes. A sensitivity power analysis with G*Power (Faul et al., 2009), indicated the study's ability to detect a small effect size (r = 0.19) with a power of 80%. Correlations and descriptive statistics are shown in Table 3. The correlation matrix of the validation constructs from Study 3 can be found in the Supplementary Table 8.

We repeated the correlation analyses excluding Items 14 and 15, which had low factor loadings, and again found no significant changes in the correlations between the factors of the LFAS and the validation constructs (see Supplementary Table 9).

General discussion

Across three studies, we crafted and validated the 17-item Liberal Feminist Attitudes Scale (LFAS), encompassing Feminist Ideology, Lifestyle Acceptance, Equal Opportunity, and Sexual Self-Determination as sub-dimensions.

The LFAS demonstrated excellent internal consistency, construct and criterion validity, and known groups validity. Its convergent validity was substantiated by positive correlations with feminist identification and self-identification as feminist. Unexpectedly, no positive link was found with the Personal Progress Scale. Discriminant validity was upheld through negative associations with Ambivalent Sexism (gender-specific), System Justification, Social Dominance Orientation, neoliberal beliefs, and conformity to female norms for the Sexual Fidelity and Relational sub-dimensions. However, contrary to predictions, no correlations emerged between liberal feminist beliefs and the Investment in Appearance and Thinness subscales. Furthermore, a significant positive relationship between liberal feminist attitudes and concrete behavioral measures was observed, along with confirmed gender-based differences, with women exhibiting higher LFAS scores compared to men.

Liberal feminist attitudes and the neoliberal subject

The four factors corresponded to the theoretically assumed thematic foci, with the dimension Feminist Ideology encompassing beliefs based on criticism of the previous and prevailing political, economic and social order. In line with common definitions of the term “feminism,” we interpret the FI factor as the core of all feminist tendencies, identities, and attitudes.

Our findings on convergent and criterion validity support this assumption. Feminist ideology correlates higher than the other sub-dimensions with feminist identification and self-labeling as a feminist. Furthermore, the specific behavioral measure of willingness to be informed about feminist actions in the future was exclusively related to FI and self-identification, but not to the individualistic dimensions Lifestyle Acceptance, Equal Opportunities and Sexual Self-Determination. Within these factors, the focus is on the decision of the form of relation and gender affiliation, bodily self-determination—which refers to abortion rights on the one hand and sexual self-determination on the other—as well as social and economic participation with a focus on the compatibility of work and family.

Rottenberg (2014) perceives work-family balance as a potential neoliberal reinterpretation of feminist ideals. Neoliberal feminism views inequality as a personal challenge, with women responsible for their wellbeing and the harmonization of work and family life seen as a matter of individual determination and resource allocation. This shift champions self-empowerment and individual success, redefining feminism as personal achievement while side-lining collective action and structural analysis. Girerd and Bonnot's (2020) findings corroborate this view, highlighting neoliberalism's hindrance to feminist identification and collective efforts.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the fourth factor, Sexual Self-Determination, diverges from extant literature on liberal feminism. It is posited that decisions regarding body and sexuality serve as manifestations of autonomous living. Young women identifying as feminists align themselves with the paradigms of pop feminism, exemplified by figures such as Miley Cyrus and Beyoncé, portraying themselves as revealing, meticulously styled, and sexually active. This phenomenon disrupts the conventional stereotypic portrayal of feminists as “frigid,” “bitter,” and “ugly,” thereby demonstrating that feminist identity encompasses a self-determined approach to both the body and sexuality. This trend is also underlined by socially significant protests, such as against restriction of advertising abortions by law in Germany. It is also reflected in the efforts of sex workers to emphasize the self-determined nature of their profession.

Rutherford (2018) argues that sexual self-determination bolsters female emancipation, forming a key element—Sexual Self-Determination (SSD)—within liberal feminist attitudes. This perspective allows women to embrace their sexuality without conforming to traditional gender norms. The influence of feminist attitudes on sexual agency aligns with the observed negative correlation between liberal feminist attitudes and the Sexual Fidelity and Relational sub-dimensions.

Bay-Cheng (2015) describes how the one-dimensional “gendered moral continuum” (p. 279), anchored at one end by the “virgin” and at the other by the “slut,” is complicated by the pursuit of sexual agency. In this context, Gill (2007) points to the concept of “postfeminist sensibility” as depicted in media culture. It encompasses notions of femininity as a physical attribute, heightened cultural sexualization, emphasis on choice and empowerment, and a concurrent focus on self-monitoring, control, and regulation. This perspective enforces femininity within the female body, targets women as consumers, intensifies the demand for meticulous self-governance, and extols the value of choice (Meenagh, 2017). Recent research by Zucker and Bay-Cheng (2020) demonstrates that neoliberal beliefs predict self-directed sexual choices, yet they also correlate with the endorsement of a double sexual standard disadvantaging women, along with heightened sensitivity to external judgments.

Since, as expected, we identified negative correlations between liberal feminist attitudes and neoliberal beliefs, as well as with constructs supporting the system, such as System Justification and Social Dominance Orientation. This suggests that despite its individualistic orientation, the measured mainstream feminism here is not inherently aligned with a neoliberal stance. While the LFAS does not differentiate from neoliberal feminist beliefs, it introduces the novel opportunity to capture mainstream feminism through personal attitudes. Future research should consider integrating LFAS with established measures of feminist identity (e.g., SIF, Szymanski, 2004) or feminist consciousness (e.g., FCS, Duncan et al., 2020). This could enable the differentiation of those identifying as feminists from those who hold liberal feminist attitudes, as well as from self-labellers, potentially offering new insights. Given the potential influence of neoliberalism on individual psychology, careful consideration is essential, as it can manifest behaviors attributed to distinct ideological positions. This approach could unveil variables, contexts, and mechanisms by which liberal feminist attitudes intersect with neoliberal discourse. It may also shed light on the reasons behind how and why young women navigate mainstream feminism within the parameters of neoliberal and postfeminist ideals.

Correlations between liberal feminist attitudes, body image, and empowerment

Contrary to our hypotheses, we observed no links between liberal feminist attitudes and internalized female beauty ideals, assessed using the Thinness and Invest in Appearance subscales of the CFNI-45. This outcome echoes diverse findings on the protective role of feminism in influencing perceptions of physical appearance (e.g., Hurt et al., 2007). While feminist beliefs can challenge societal beauty norms, they might not directly reshape an individual's body-related thoughts or emotions (Rubin et al., 2004). Identifying as a feminist involves adopting a stigmatized social identity (Aronson, 2003), potentially leading to a greater likelihood of rejecting multiple societal norms, including those related to appearance. Moreover, social identity theory (Tajfel, 1981) suggests that women who label themselves feminists may have their worldviews more profoundly shaped by their feminist ideology compared to non-feminist women, even if their beliefs align with feminism. However, given our finding of no correlation between feminist identification and internalized beauty norms, we recommend re-evaluating the interplay between liberal feminist attitudes, feminist identity, body perceptions, and the potential influence of moderator or mediator variables, along with a broader exploration of female beauty ideals.

Interestingly, contrary to our hypothesis, we uncovered a slight negative correlation between liberal feminist attitudes and dimensions of female empowerment, self-determination, and the ability to mobilize internal and external resources for personal and societal change, as gauged by the PPS-R (Johnson et al., 2005). This finding diverges from prior evidence suggesting that feminist attitudes could aid women, such as by enabling them to label experiences in the face of prevailing sexism and redirect blame (Moradi and Subich, 2002). Nevertheless, some authors emphasize that a high score in the disclosure phase of FIC may be associated with psychological distress and reduced self-esteem (Fischer et al., 2000; Moradi and Subich, 2002). This phase corresponds to times of crises marked by the questioning of conventional gender roles, feelings of anger and powerlessness, and dualistic thinking.

Furthermore, feminist attitudes might enhance the recognition of discrimination, potentially leading to wellbeing decline, unless this association is mediated by alignment with the marginalized group (Schmitt et al., 2014). Conversely, strong alignment with the marginalized group might moderate the detrimental wellbeing outcomes by intensifying perceived discrimination (Schmitt et al., 2014). We advise a nuanced differentiation between attitudinal and identification metrics in future research to untangle the multifaceted impact mechanisms of feminism on empowerment and self-determination.

The way in which the LFAS captures feminist attitudes aligns with the complexity of social change that we are currently witnessing. For instance, the gradual increase in gender equality at national and international levels (UNDP, 2022; EIGE, 2023) does not necessarily correspond to a decrease in gender-based segregation in education and the job market. On the contrary, the gender-equality paradox (Stoet and Geary, 2018) describes that with increasing gender equality in a country, gender-based STEM gaps in post-primary education also increase. Through the nuanced assessment of both system-critical and individualistic attitudes, the LFAS can provide a more detailed examination of this apparent paradox. It allows for a deeper exploration of mainstream feminism, where female empowerment might not necessarily conflict with advocating prototypical female roles, shedding light on this phenomenon and aiding in a better understanding thereof.

Limitation and further research

Contrary to Siegel and Calogero's (2021) recommendations, no item explicitly includes the terms “feminism” or “feminist.” Although such labeling in surveys or study designs can provide insights into predicting behaviors (e.g., Collective Action, Radke et al., 2016), qualitative mixed-methods studies show considerable variability in individual definitions of feminism. Different understandings of feminism can influence feminist self-identification (Swirsky and Angelone, 2014; Hoskin et al., 2017). In order to minimize potential influences arising from differing understandings and possible negative stereotyping, we intentionally avoided the use of these terms in this study. Given the integration of feminist issues into mainstream culture, future research should consider the explicit use of such terms and explore participants' interpretations of “feminism” and its interplay with feminist attitudes and identification (Hoskin et al., 2017; Siegel and Calogero, 2021).

Siegel and Calogero (2021) emphasize the importance of measurement tools that encompass cisgender men and individuals who reject the binary gender classification, identifying as non-binary. They also stress the incorporation of intersectionality within feminist attitudes, presenting a challenge for new scale development. It is noteworthy that the LFAS items are tailored to hetero/cis normative individuals, excluding those beyond these categories. This choice aligns with the liberal feminist perspective of the 'homogeneous woman'. Future research should critically evaluate the absence of intersectional considerations and the need to embrace a diverse range of identities, enabling the LFAS to better capture the evolving socio-political landscape and socio-demographic context in which it is employed.

A significant portion of participants in our studies identified as female and fell primarily within the 20–30 years age range, with a notable level of education. The sample's demographic uniformity limits the applicability of LFAS findings to broader populations. Further investigations could shed light on the contextual nuances of liberal feminist attitudes. For instance, older cohorts, more directly exposed to historical feminist movements (e.g., women from the 1960's and 70's feminist era), might perceive liberal feminism differently due to their familiarity with its complexity compared to younger generations.

All studies were conducted in Germany, limiting the generalizability of results beyond this specific socio-cultural context. While certain feminist debates, like the #MeToo movement, have global relevance, topics tied to German legal frameworks—such as gender-neutral marriage and the abolition of Section 219a of the German Criminal Code—remain specific for the German context. Ongoing socially polarized discussions, such as those about the implementation of gender-sensitive language are also confined to the German culture. Moreover, feminist discourses on women's employment, uneven caregiving distribution, and preferences for heteronormative marriages are intricately linked to applicable national legal framework, which prevents a seamless comparison with other national contexts. Nevertheless, applying the LFAS in, for example, English-speaking countries could be of great benefit and offers interesting possibilities for a comparative analysis of the feminist mainstream movement. To facilitate cross-national comparability, the wording of the items was deliberately designed to be non-specific and adaptable to different cultural contexts (except of item 7). In view of the global influence of pop feminism, which emanates primarily from Anglo-American regions, it is reasonable to assume that mainstream feminism is similar on an international level. Future research efforts could examine the manifestation of liberal-feminist attitudes in the context of different national legal systems and recognize their connection to the observed international backlash, as well as deciphering possible links to the propensity for social protest and collective action.

For this reason, we recommend validating the scale in English-speaking countries. The English translation of the items can be found in Table 1. It is important to recognize that feminism and its variations are culturally contingent, influenced by national laws, societal values, norms, and evolving dynamics. The LFAS functions as a measurement tool uniquely positioned to delineate the contemporary feminist zeitgeist within society. Distinguished from existing instruments, it intricately captures the essence of mainstream feminism, offering a precise demarcation of liberal feminist attitudes against feminist identity, while also providing a nuanced measure of the intensity of such attitudes. This measuring instrument facilitates an in-depth exploration of intricate developments in feminist orientation, their interplay with feminist identity, potential influences from neoliberal ideologies, and discerning associated social and individual ramifications.

Conclusion

The development and validation of the LFAS enables, for the first time, a deliberate and explicit examination of liberal feminist attitudes, particularly as they manifest within the German-speaking context. The validation constructs employed in this study offer initial insights, suggesting a multitude of future research opportunities aimed at comprehending how liberal feminism has evolved from a tangible social movement into a pervasive and occasionally contradictory element of contemporary discourse, personal experiences, and behaviors. Given the historical shifts in US abortion legislation, such as the reversal of Roe v. Wade, as well as the curtailment of abortion rights in European nations like Poland and Hungary, the significance of this research on women's rights is paramount.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

B-LH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. SB: Writing – review & editing. EK: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. FA: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) project number 491193532 and the Chemnitz University of Technology.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2024.1329067/full#supplementary-material

References

Aronson, P. (2003). Feminists or “postfeminists”? Gender Soc. 17, 903–922. doi: 10.1177/0891243203257145

Asbrock, F., Sibley, C. G., and Duckitt, J. (2010). Right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice: a longitudinal test. Eur. J. Personal. 24, 324–340. doi: 10.1002/per.746

Ashmore, R. D., Deaux, K., and McLaughlin-Volpe, T. (2004). An organizing framework for collective identity: articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychol. Bullet. 130, 80–114. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.80

Baber, K., and Tucker, C. (2006). The social roles questionnaire: a new approach to measuring attitudes toward gender. Sex Roles 54, 459–467. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9018-y

Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2015). The agency line: a neoliberal metric for appraising young women's sexuality. Sex Roles 73, 279–291. doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0452-6

Bay-Cheng, L. Y., Fitz, C. C., Alizaga, N. M., and Zucker, A. N. (2015). Tracking homo oeconomicus: development of the neoliberal beliefs inventory. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 3, 71–88. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v3i1.366

Bay-Cheng, L. Y., and Zucker, A. N. (2007). Feminism between the sheets: sexual attitudes among feminists, nonfeminists, and egalitarians. Psychol. Women Quart. 31, 157–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00349.x

Becker, J. C., and Wright, S. C. (2011). Yet another dark side of chivalry: benevolent sexism undermines and hostile sexism motivates collective action for social change. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 101, 62–77. doi: 10.1037/a0022615

Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociol. Methods Res. 17, 303–316. doi: 10.1177/0049124189017003004

Cambridge Dictionary (2022). Feminism. Cambridge Dictionary. Available online at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/feminism (accessed June 22, 2022).

Carvacho, H., Gerber, M., Manzi, J., González, R., Jiménez-Moya, G., Boege, R., et al. (2018). Validation and Measurement Invariance of the Spanish and German Versions of SDO-7. Santiago: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Christopher, A. N., and Wojda, M. R. (2008). Social dominance orientation, right-wing authoritarianism, sexism, and prejudice toward women in the workforce. Psychol. Women Quart. 32, 65–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00407.x

Donovan, J. (2012). Feminist Theory, Fourth Edition: The Intellectual Traditions. New York, NY: Continuum.

Downing, N. E., and Roush, K. L. (1985). From passive acceptance to active commitment: a model of feminist identity development for women. Counsel. Psychol. 13, 695–709. doi: 10.1177/0011000085134013

Duncan, L. E., Garcia, R. L., and Teitelman, I. (2020). Assessing politicized gender identity: validating the Feminist Consciousness Scale for men and women. J. Soc. Psychol. 161, 570–592. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2020.1860883

Eckes, T., and Six-Materna, I. (1999). Hostilität und Benevolenz: Eine Skala zur Erfassung des ambivalenten Sexismus. Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie 30, 211–228. doi: 10.1024//0044-3514.30.4.211

Ehlers, N. (2016). “Identities,” in Oxford Handbook of Fminism Theory, eds. L. Disch and M. Hawkesworth (New York, NY: Oxford University Press).

EIGE (2023). Gender Equality Index 2023. Towards a Green Transition in Transport and Energy. Publication Office of the European Union. Available online at: https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/publications/gender-equality-index-2023-towards-green-transition-transport-and-energy?language_content_entity=en (accessed October 25, 2023).

Erchull, M. J., Liss, M., Wilson, K. A., Bateman, L., Peterson, A., and Sanchez, C. E. (2009). The feminist identity development model: relevant for young women today? Sex Roles 60, 832–842. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9588-6

Fassinger, R. E. (1994). Development and testing of the Attitudes Toward Feminism and the Women's Movement (FWM) Scale. Psychol. Women Quart. 18, 389–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00462.x

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., and Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Fischer, A. R., Tokar, D. M., Mergl, M. M., Good, G. E., Hill, M. S., and Blum, S. A. (2000). Assessing women's feminist identity development: studies of convergent, discriminant, and structural validity. Psychol. Women Quart. 24, 15–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01018.x

Fitz, C. C., Zucker, A. N., and Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2012). Not all nonlabelers are created equal: distinguishing between quasi-feminists and neoliberals. Psychol. Women Quart. 36, 274–285. doi: 10.1177/0361684312451098

Fraser, G., Osborne, D., and Sibley, C. G. (2015). “We want you in the Workplace, but only in a Skirt!” Social dominance orientation, gender-based affirmative action and the moderating role of benevolent sexism. Sex Roles 73, 231–244. doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0515-8

Frieze, I. H., and McHugh, M. C. (1998). Measuring feminism and gender role attitudes. Psychol. Women Quart. 22, 349–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00159.x

Gill, R. (2007). Postfeminist media culture. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 10, 147–166. doi: 10.1177/1367549407075898

Gill, R. (2016). Post-postfeminism? New feminist visibilities in postfeminist times. Feminist Media Stud. 16, 610–630. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2016.1193293

Girerd, L., and Bonnot, V. (2020). Neoliberalism: an ideological barrier to feminist identification and collective action. Soc. Just. Res. 20:8. doi: 10.1007/s11211-020-00347-8

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. T. (1996). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 70, 491–512. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Henley, N. M., Meng, K., O'Brien, D., McCarthy, W. J., and Sockloskie, R. J. (1998). Developing a scale to measure the diversity of feminist attitudes. Psychol. Women Quart. 22, 317–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00158.x

Henley, N. M., Spalding, L. R., and Kosta, A. (2000). Development of the short form of the feminist perspectives scale. Psychol. Women Quart. 24, 254–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00207.x

Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., Levin, S., Thomsen, L., Kteily, N., et al. (2012). Social dominance orientation. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 38, 583–606. doi: 10.1177/0146167211432765

Hoskin, R. A., Jenson, K. E., and Blair, K. L. (2017). Is our feminism bullshit? The importance of intersectionality in adopting a feminist identity. Cogent Soc. Sci. 3:1290014. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2017.1290014

Hurt, M. M., Nelson, J. A., Turner, D. L., Haines, M. E., Ramsey, L. R., Erchull, M. J., et al. (2007). Feminism: what is it good for? Feminine norms and objectification as the link between feminist identity and clinically relevant outcomes. Sex Roles 57, 355–363. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9272-7

Hyde, J. S. (2002). Feminist identity development. Counsel. Psychol. 30, 105–110. doi: 10.1177/0011000002301007

Johnson, D. M., Worell, J., and Chandler, R. K. (2005). Assessing psychological health and empowerment in women: the personal progress scale revised. Women Health 41, 109–129. doi: 10.1300/J013v41n01_07

Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., and Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of system justification theory: accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Polit. Psychol. 25, 881–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00402.x

Jost, J. T., and Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 88, 498–509. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.498

Kahn, J. H. (2006). Factor analysis in counseling psychology research, training, and practice. Counsel. Psychol. 34, 684–718. doi: 10.1177/0011000006286347

Kenny, D. A. (2014). Measuring Model Fit. Available online at: http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm (accessed April 15, 2022).

Kirkpatrick, C. (1936). The construction of a belief-pattern scale for measuring attitudes to-ward feminism. J. Soc. Psychol. 7, 421–437. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1936.9919893

Liss, M., and Erchull, M. J. (2010). Everyone feels empowered: Understanding feminist self-labeling. Psychol. Women Q. 34, 85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01544.x

Manganelli, A. M., Bobbio, A., and Canova, L. (2012). Sexism, conservative ideology and attitudes toward women as managers. Psicol. Soc 7, 241–260. doi: 10.1482/37697

McCabe, J. (2005). What's in a label? The relationship between feminist self-identification and “feminist” attitudes among U.S. women and men. Gender Soc. 19, 480–505. doi: 10.1177/0891243204273498

McHugh, M. C., and Frieze, I. H. (1997). The measurement of gender-role attitudes. Psychol. Women Quart. 21, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00097.x

Meenagh, J. (2017). Breaking up and hooking up: a young woman's experience of “sexual empowerment”. Femin. Psychol. 27, 447–464. doi: 10.1177/0959353517731434

Moon, D. G., and Holling, M. A. (2020). “White supremacy in heels”: (white) feminism, white supremacy, and discursive violence. Commun. Crit. 17, 253–260. doi: 10.1080/14791420.2020.1770819

Moradi, B., and Subich, L. M. (2002). Perceived sexist events and feminist identity development attitudes. Counsel. Psychol. 30, 44–65. doi: 10.1177/0011000002301003

Moradi, B., and Yoder, J. D. (2011). “Current status and future directions in research on women's experiences,” in The Oxford Hand- Book of Counseling Psychology, eds. E. M. Altmaier and J. C. Hansen (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 346–374.

Morgan, B. (1996). Putting the feminism into feminism scales: introduction of a liberal feminist attitude and ideological scale (LFAIS). Sex Roles 34, 359–390. doi: 10.1007/BF01547807

Myers, N. D., Ahn, S., and Jin, Y. (2011). Sample size and power estimates for a confirmatory factor analytic model in exercise and sport. Res. Quart. Exer. Sport 82, 412–423. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2011.10599773

Myers, T. A., and Crowther, J. H. (2007). Sociocultural pressures, thin-ideal internalization, self-objectification, and body dissatisfaction: could feminist beliefs be a moderating factor? Body Image 4, 296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.04.001

Nelson, J. A., Liss, M., Erchull, M. J., Hurt, M. M., Ramsey, L. R., Turner, D. L., et al. (2008). Identity in action: predictors of feminist self-identification and collective action. Sex Roles 58, 721–728. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9384-0

Parent, M. C., and Moradi, B. (2010). Confirmatory factor analysis of the conformity to feminine norms inventory and development of an abbreviated version: the CFNI-45. Psychol. Women Quart. 34, 97–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01545.x

Parent, M. C., and Moradi, B. (2011). An abbreviated tool for assessing feminine norm conformity: psychometric properties of the Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory-45. Psychol. Assess. 23, 958–969. doi: 10.1037/a0024082

Peterson, R. D., Tantleff-Dunn, S., and Bedwell, J. S. (2006). The effects of exposure to feminist ideology on women's body image. Body Image 3, 237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.05.004

Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., and Jans, L. (2012). A single-item measure of social identification: reliability, validity, and utility. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 52, 597–617. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12006

Radke, H. R. M., Hornsey, M. J., and Barlow, F. K. (2016). Barriers to women engaging in collective action to overcome sexism. Am. Psychol. 71, 863–874. doi: 10.1037/a0040345

Redford, L., Howell, J. L., Meijs, M. H. J., and Ratliff, K. A. (2016). Implicit and explicit evaluations of feminist prototypes predict feminist identity and behavior. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 21, 3–18. doi: 10.1177/1368430216630193

Reidy, D. E., Shirk, S. D., Sloan, C. A., and Zeichner, A. (2009). Men who aggress against women: effects of feminine gender role violation on physical aggression in hypermasculine men. Psychol. Men Masculinity 10, 1–12. doi: 10.1037/a0014794

Rickard, K. M. (1989). The relationship of self-monitored dating behaviors to level of feminist identity on the feminist identity scale. Sex Roles 20, 213–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00287993

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modelling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rottenberg, C. (2014). The rise of neoliberal feminism. Cult. Stud. 28, 418–437. doi: 10.1080/09502386.2013.857361

RStudio Team (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio Team. Available online at: http://www.rstudio.com/

Rubin, L. R., Nemeroff, C. J., and Russo, N. F. (2004). Exploring feminist women's body consciousness. Psychol. Women Quart. 28, 27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00120.x

Rutherford, A. (2018). Feminism, psychology, and the gendering of neoliberal subjectivity: from critique to disruption. Theory Psychol. 28, 619–644. doi: 10.1177/0959354318797194

Scarborough, W. J., Sin, R., and Risman, B. (2018). Attitudes and the stalled gender revolution: egalitarianism, traditionalism, and ambivalence from 1977 through 2016. Gender Soc. 33, 173–200. doi: 10.1177/0891243218809604

Schick, V. R., Zucker, A. N., and Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2008). Safer, better sex through feminism: the role of feminist ideology in women's sexual well-being. Psychol. Women Quart. 32, 225–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00431.x

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., and Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bullet. 140, 921–948. doi: 10.1037/a0035754

Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M. S., and Duckitt, J. (2007). Antecedents of men's hostile and benevolent sexism: the dual roles of social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 33, 160–172. doi: 10.1177/0146167206294745

Siegel, J. A., and Calogero, R. M. (2021). Measurement of feminist identity and attitudes over the past half century: a critical review and call for further research. Sex Roles 85, 248–270. doi: 10.1007/s11199-020-01219-w

Smith, E. R., Ferree, M. M., and Miller, F. D. (1975). A short scale of attitudes toward feminism. Represent. Res. Soc. Psychol. 6, 51–56.

Smolak, L., and Murnen, S. K. (2008). Drive for leanness: assessment and relationship to gender, gender role and objectification. Body Image 5, 251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.03.004

Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R., and Stapp, J. (1972). A short version of the Attitudes toward Women Scale (AWS). Bullet. Psychon. Soc. 2, 219–220. doi: 10.3758/BF03329252

Stoet, G., and Geary, D. C. (2018). The gender-equality paradox in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education. Psychol. Sci. 29, 581–593. doi: 10.1177/0956797617741719

Swirsky, J. M., and Angelone, D. J. (2014). Femi-Nazis and bra burning crazies: a qualitative evaluation of contemporary beliefs about feminism. Curr. Psychol. 33, 229–245. doi: 10.1007/s12144-014-9208-7

Szymanski, D. M. (2004). Relations among dimensions of feminism and internalized heterosexism in lesbians and bisexual women. Sex Roles 51, 145–159. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000037759.33014.55

Tabachnick, B., and Fidell, L. (2001). Using Multivariate Statistics, 4th Edn. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., and Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Ullrich, J., and Cohrs, J. C. (2007). Terrorism salience increases system justification: experimental evidence. Soc. Just. Res. 20, 117–139. doi: 10.1007/s11211-007-0035-y

UNDP (2022). Human Development Report 2021/2022. Uncertain Times, Unsettles Lives. Shaping Our Future in a Transforming World. Available online at: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2021-22pdf_1.pdf (accessed March 26, 2023).

United Nations (2022). The 17 Goals. Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls. Available online at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed June 19, 2022).

van Breen, J. A., Spears, R., Kuppens, T., and de Lemus, S. (2017). A multiple identity approach to gender: identification with women, identification with feminists, and their interaction. Front. Psychol. 8:1019. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01019

Weis, A. S., Redford, L., Zucker, A. N., and Ratliff, K. A. (2018). Feminist identity, attitudes toward feminist prototypes, and willingness to intervene in everyday sexist events. Psychol. Women Quart. 42, 279–290. doi: 10.1177/0361684318764694

Weston, R., and Gore, P. A. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. Counsel. Psychol. 34, 719–751. doi: 10.1177/0011000006286345

Yoder, J. D., Perry, R. L., and Saal, E. I. (2007). What good is a feminist identity? Women's feminist identification and role expectations for intimate and sexual relationships. Sex Roles 57, 365–372. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9269-2

Yong, A. G., and Pearce, S. (2013). A beginner's guide to factor analysis: focusing on exloratory factor analysis. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 9, 79–94. doi: 10.20982/tqmp.09.2.p079

Zhang, Y., and Rios, K. (2021). Understanding perceptions of radical and liberal feminists: the nuanced roles of warmth and competence. Sex Roles 86, 143–158. doi: 10.1007/s11199-021-01257-y

Zucker, A. N., and Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2020). Me first: the relation between neoliberal beliefs and sexual attitudes. Sexual. Res. Soc. Pol. 18, 390–396. doi: 10.1007/s13178-020-00466-6

Keywords: liberal feminism, feminist attitudes, measurement, feminism, neoliberalism

Citation: Henze B-L, Buhl S, Kolbe E and Asbrock F (2024) Should we all be feminists? Development of the Liberal Feminist Attitudes Scale. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1329067. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1329067

Received: 27 October 2023; Accepted: 10 January 2024;

Published: 13 February 2024.

Edited by:

Scott Eidelman, University of Arkansas, United StatesReviewed by:

Silvia Galdi, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyAleksandra Cislak, SWPS University, Poland

Copyright © 2024 Henze, Buhl, Kolbe and Asbrock. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bonny-Lycen Henze, Ym9ubnlseWNlbkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†ORCID: Bonny-Lycen Henze orcid.org/0000-0001-8716-5630

Sarah Buhl orcid.org/0000-0003-4257-8890

Frank Asbrock orcid.org/0000-0002-6348-2946

Bonny-Lycen Henze

Bonny-Lycen Henze Sarah Buhl

Sarah Buhl Elisa Kolbe

Elisa Kolbe Frank Asbrock

Frank Asbrock