- School of Health in Social Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Despite the early roots of arts and health as grounded within rituals and interest in ”community”– a term that is deeply laden with a history of rituals - the role of ”ritual” in modern arts and health is largely untheorized. Yet, ”secularized” rituals can teach us about contemporary life, beliefs, and practices, playing a role in our understanding of how and why the arts connect to health and wellbeing. In this article, I draw on published literature and insights from my experiences in the field of arts and health to make the case that incorporating “ritual” as a concept within arts and health research serves to expand existing thinking in social psychology. Specifically, I link Interaction Ritual Chain (IRC) theory and the social cure approach (a social identity approach to health) to theorize that arts activities may enable the construction of group identities through participation in interaction rituals, whereby ritual outcomes across chains of interactions may be considered as expressions of health and wellbeing. The article makes an original contribution to social psychology by connecting IRC theory to a social identity approach to health, laying a new theoretical foundation for researchers working in arts and health.

Introduction

Although the connection between the arts and health has been argued as dating back to the Paleolithic period, “arts and health” as a field of research and practice has been given increasing credibility over the last two decades due to growing interest in policy regarding the role of the arts in public health (Fancourt, 2017). This has been particularly the case in Western contexts, with “evidence” positioned within Western policies and sociocultural paradigms of health and illness, whereby the growth of the field has intersected with broader shifts in policy and research, such as the growth of evidence-based policymaking. Notable publications in the field include the 2017 report Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing from the UK All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Arts, Health and Wellbeing (All-Party Parliamentary Group for Arts, 2017) and follow-up 2023 Creative Health Review in partnership with the National Centre for Creative Health (The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts Health and Wellbeing and the National Centre for Creative, Health, 2023), the 2019 World Health Organization evidence synthesis on the role of the arts in health and wellbeing (Fancourt and Finn, 2019), and the 2022 CultureForHealth report funded by the EU Commission (Zbranca et al., 2022). Within this landscape, taking a community asset-based approach that draws on existing resources in the community or employing a social model of health that focuses on salutogenesis, rather than a deficit model, has rapidly grown in interest across research, policy, and practice, particularly in view of recent development and implementation of social- or arts-on- prescription programmes (Chatterjee et al., 2018; Fancourt et al., 2021). Further, although arts and health researchers initially focused on the impact of the arts on health outcomes, and this remains an important focus for decision-makers and evaluators wishing to evidence the benefits of the arts to scale up programmes such as part of community initiatives, there has been increasing interest in understanding the underlying mechanisms of how the arts affect health, and viewing the arts as part of complex adaptive systems (Fancourt et al., 2020; Fancourt and Warran, 2024; Warran et al., 2022).

Yet, despite the early roots of arts and health as grounded within rituals, such as rituals connected to fertility and health in the Paleolithic period (Fancourt, 2017), the language of “ritual” has largely been stripped from the modern field of arts and health. Indeed, the word “ritual” is not mentioned in any of the aforementioned flagship reports on the role of the arts in health and wellbeing. Given the ever-increasing focus on the role of “community” in the context of arts and health—a term that is deeply laden with a history of rituals (Delanty, 2010; Stephenson, 2015)—it seems somewhat surprising that the role of “ritual” in modern arts and health is largely untheorized. One reason for this may be that the language of “ritual” has historical ties to religion. Because the arts are not necessarily intertwined with religion (as it could be argued they may once have been; Carey, 2005) and have become largely secularized, their role as meaning-making cultural activities that connect with our sense of self and wellness within modernity are overlooked. While there is a body of literature on ritual (e.g., Kenny, 1982, 1989; Aigen, 1991) in the related field of arts therapies (see Box 1), this has tended to draw on anthropological understandings and spiritual practices, where the focus has been on exploring the relevance of ritual to the specific contexts of therapy, healing, and individual psychological support. The (micro)sociological perspective that ritual is a social phenomenon, with “modern” or “secularized” rituals able to teach us something about everyday contemporary life, beliefs, and practices, is given little attention.1

Box 1. Conceptualizing arts and health.

There is no single definition of “arts and health” and it is a complex term that can mean different things to different people in different contexts. It is also closely interconnected to, and often overlaps with, the related terms of “arts in health,” “arts for health,” and “creative health.” “Creative health” has burgeoned in recent years, particularly since the publication of the 2017 and 2023 APPG reports and the creation of the National Centre for Creative Health (NCCH) in the UK. In this article, the choice has been made to use the language of “arts” rather than “creative” for two reasons. Firstly, although it is growing in popularity, “creative health” is predominantly a UK term, with “arts and health” used globally more frequently (e.g., the Jameel Arts & Health Lab: a global initiative). Secondly, the language of “arts” acknowledges the role of arts' practices, artists, arts policies, and the arts' sector in the construction and maintenance of the field of “arts and health.” Within this frame of understanding, arts and health may be conceptualized as including a diverse range of kinds of activities (e.g., performing arts, visual arts, digital arts, literary arts, cultural engagement; Fancourt and Finn, 2019) across multiple modes (e.g., attending, creating, participating, consuming, learning; Sonke et al., 2023). I also choose to use arts “and” health as I seek to give an equal weighting to both the arts and health (Fancourt, 2017), recognizing that these different worlds bring together multiple epistemologies.

The question of whether or not to include creative arts therapies (e.g., art therapy, music therapy, drama therapy) in a definition of “arts and health” is more complex. Theoretically, therapies very much fit within an understanding of exploring the relationship between the arts and health. However, institutionally, the structure and delivery of arts therapies tends to be different, with different research and practice histories. In the UK, specific accredited training is needed to be an arts therapist and to practice within clinical contexts, so the use of the language of “therapy” outside of those particular contexts may be confusing. Although this is a complex picture, as there are community therapies and often accredited arts therapists work in contexts outside of those in which their accredited training is required, the distinction between “arts therapies” and broader arts and health practices is important to delineate those who are trained to practice clinically to meet specific patient outcomes from those who work in more diverse ways across multiple contexts and groups.

The focus of this article is on “arts and health” relating to work and practice that falls outside of formal arts therapies. There is a recognition of overlaps between the shared values of the fields (Van Lith and Spooner, 2018) and that literature from arts therapies has relevance to the discussion, and this is noted where relevant throughout the article.

In my view, rituals, particularly “interaction rituals” (Goffman, 1967) which I will explore in this article, have a central role to play in our understanding of how and why the arts connect to health and wellbeing, and why secular arts and health rituals are meaningful for those who engage in them. Further, given the increasing interest in how the arts may be able to support health, particularly from policymakers, commissioners, and health and social care institutions, embarking on the endeavor to think about and understand the role of interaction ritual within arts and health is a much-needed focus to elucidate the ways in which arts and health activities are deeply interconnected to our culture, interactions, and shared humanity. Thus, it is the purpose of this article to explore how “interaction ritual” could be used as a mode of analysis within future study in arts and health. I draw on published literature and insights from my experiences in the field of arts and health and reflections on my own research to make the case that researchers and policymakers should consider incorporating ritual as a concept within their theoretical apparatus in future research. It is hoped that this discursive foundation could be used to incite future empirical research to explore the ideas presented further. Of note, the theoretical development presented seeks to expand theory in social psychology, notably “the social cure approach” (Haslam et al., 2018), and the article is intended as a foundation to further deepen this approach through drawing on theoretical tools from interaction ritual chain theory (Collins, 2004). Doing so illuminates new theorized mechanisms of change linking the arts to health that could be explored empirically by social psychologists and interdisciplinary scholars in future research. How arts and health is understood and conceptualized in the article is outlined further in Box 1.

Working in a theoretically interdisciplinary way

Despite the importance of theorizing (as a process) underpinning empirical processes (Swedberg, 2012), it is the testing of theory (as a product) that dominates contemporary research. This is perhaps because theorizing is a multifaceted process that involves imagination and intuition, meaning that it is iterative and non-linear (Abbott, 2004; Swedberg, 2012). It can be challenging to know how to begin to theorize. One way it has been suggested that new knowledge can be created in one field or discipline is to borrow ideas and ways of thinking from another discipline (Abbott, 2004). Yet, doing so can create conceptual and epistemological challenges, alongside “an element of incompatibility between disciplines and approaches” (Gray, 2010, p. 226). Moreover, disciplines have themselves sought to construct boundaries in order to uphold certain disciplinary identities constructed through processes of distinction, with it argued that “interdisciplinary liaisons are dangerous” (Brossard and Sallée, 2019).

In this article, I have taken an interdisciplinary approach to theorizing, seeking to combine theories and approaches from social psychology, sociology, and public health to further understand the relationship between the arts and health. I build a rationale for these combinations in the earlier parts of the article and then work toward the construction of a new theory that combines Collins' (2004) emotional-entrainment model (part of his theory of Interaction Ritual Chains) and the “social cure” (an approach that draws on a social identity approach to health and wellbeing) (Haslam et al., 2018) to argue that “interaction ritual” can be a useful analytic lens to understand the relationship between the arts and health. This article is broadly a conceptual exploration, in that I am thinking through ideas and avenues that could be explored in future empirical research, and it is acknowledged that, to some, ontological complexities and contradictions may be inherent within it. Rather than seeking to “overcome” these complexities, I have sought to sit with them and recognize that innovating and creating new knowledge entails pushing boundaries and working through conceptual complexities, rather than trying to “solve” them and seek a resolution to every problem. Theoretical purists may experience challenges in what I suggest and, in particular, by operationalising sociological theory in the context of practical public health implications, the work may be viewed as too “mechanistic.”2 Yet, I have chosen to work in this way in the recognition that innovating and inciting the “sociological imagination” (Wright Mills, 1959) has the potential to open the door to new avenues, pathways, contradictions, and questions, and that creating more questions than answers is also a worthwhile endeavor. As argued by Russell (1912) on his discussion of the value of philosophy, “philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions… but rather for the sake of the questions themselves… because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible.” In a similar vein, through reflecting on the potential links between arts, ritual, and health, it is my hope that I can provide a foundation that may open new avenues of what may be possible in the future of research in the field.

Understanding secular rituals as interaction rituals

There have been many endeavours to define what constitutes a “ritual” and what specific characteristics mean a ritual has taken place (Snoek, 2006). Some have drawn upon Aristotelian definitions of classification and category membership, seeking to define the necessary and sufficient conditions of a ritual (Snoek, 2006). Others have prioritised the act of doing and understanding rituals in terms of their function (Stephenson, 2015). For example, a ritual may be considered as a “a culturally strategic way of acting in the world” (Bell, 1992, p. vii [my emphasis]). Thus, rather than focusing on discrete characteristics, there may be certain (fluid) conditions that may, in some circumstances, constitute a successful ritual and, in other cases, may not. The elements that create the ritual may change and are dependent on changing sociocultural factors. Such an analysis of ritual can be unpacked further through exploring secular rituals as interaction rituals (IRs), originally conceptualised by sociologist and social psychologist Erving Goffman (1922-1982).

Goffman was interested in face-to-face interaction and in the “image of self” that one shares with others within a social encounter (Goffman, 1967, p. 5). He argued, however, that these interactions were not defined by the “individual and [their] psychology” but instead by “the syntactical relations among the acts of different persons” (Goffman, 1967, p. 2). Individuals draw on various “behavioral materials” such as “glances, gestures, positionings, and verbal statements” (Goffman, 1967, p. 1) that are appropriate. The situation defines behaviours and not the other way around. In view of this understanding of interaction order, Goffman theorized that rituals are not limited to sacred ceremonies but include mundane events and everyday routines (Kádár, 2024; Goffman, 1967). There are “countless patterns” that we perform to one another based on a context and our role in that context (Goffman, 1967, p. 2). For example, the greeting between friends meeting at an informal café which involves a hug together to confirm their friendship versus the greeting between colleagues of shaking hands in a formal meeting room which confirms the start of a business discussion. Goffman coined these patterned behaviours within face-to-face interactions “interactional rituals” (IRs) (Goffman, 1967).

Yet, Goffman's definition of IR is broad and the mechanisms of how IRs operate across different contexts, and how they become meaningful, are underexplored. Building on Goffman's conceptualisation of IRs, Collins (2004) has more recently combined the work of Émile Durkheim with Goffman's study of interaction to develop his theory of Interaction Ritual Chains (IRCs), described as a “radical microsociology.” Durkheim was one of the first supporters of the idea of ritual as revelatory of meanings in society. Despite its title including the word “religion,” within sociology it is widely accepted that Durkheim's Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912) is not only about religion and religious rituals, per se, but rather about religious contexts (e.g., aboriginal communities in Australia) as examples of how social solidarity may operate in any social context. As a result of this seminal work, “ritual” became a key concept to explore and explain what holds society together, including how orders of meaning, purpose and value are created and maintained (Stephenson, 2015, p. 38). But it is Durkheim's concept of collective effervescence defined as “an extraordinary degree of exaltation” (Durkheim, 2001, p. 162) that has had profound influence on the development of interaction ritual theory and, more broadly, on understanding group processes in social psychology. This extraordinary emotional experience can act as a social glue to hold groups and societies together.

Drawing on Goffman to argue that ritual can be found to “one degree or another throughout everyday life,” and there is a “fluidity” to them, Collins sees rituals as interaction rituals (Collins, 2004, pp. 7-8). But he centres the notion of collective effervescence, putting forward his emotional-entrainment model (see Collins, 2004, p. 48). This model illustrates that IRs happen across a chain of situational contexts whereby individuals who are gathered together with a mutual focus of attention and shared mood experience collective effervescence and become “pumped up” with emotional energy (EE), alongside feelings of group solidarity and a sense of shared symbols and standards of morality. On the other hand, failed rituals result in individuals feeling drained and excluded. When the components and mechanisms of this model are enacted, it is theorized that an interaction ritual has taken place, and when they happen across more than one situation, they happen in a chain.

Yet, the success of the interaction ritual depends on the degree to which the ritual ingredients are present (i.e., group assembly, barriers to outsiders, mutual focus of attention, shared mood), with those that have a “high degree of emotional entrainment” resulting in stronger feelings of group membership (Collins, 2004, p. 42). Rituals range from “the barest utilitarian encounters and failed rituals to intensely engaging ritual solidarity” (Collins, 2004, p. 141). And other factors such as where an individual is located in an IR (central/peripheral participation), whether individuals engage in an aggregate chain or IRs (social density), and whether the people who gather for a chain of IRs are the same of different each time (social diversity) will influence ritual intensity and the strength of feelings of solidarity with others participating in the ritual (see pp. 116–117 of Collins, 2004).

How rituals become meaningful: emotions and cultural context

As we have seen in the cases of Durkheim, Goffman, and Collins, one way that actions become meaningful is in and through social interactions. This is even the case for acts undertaken alone because understandings of who we are, what we think, and what is important to us come from the interactions we have shared with others; we are social beings. But there is more to it than interaction alone. If every interaction were meaningful, there would be no conflict, no disagreements, no feelings of isolation and, ultimately, no failed rituals. It is not just about social interactions; it is about the emotions brought into, created and sustained through these interactions, and the morality in which those engaging in a ritual share and affirm.

Collective effervescence is a key part of the shared emotional experience that enables rituals to become meaningful. The “exaltation” of this experience is especially present within crowds who are “moved by a common passion” whereby a sharing of beliefs results in a kind of unity, raising the individual above one's self, and enabling “feelings and actions of which we are incapable [of] on our own” (Durkheim, 2001, p. 157). Collins unpacks this concept in more detail and applies it to the micro-level, explaining that emotions are important at every stage of the ritual. Shared mood is an important ritual ingredient that underpins collective effervescence, which leads to EE in the individual if the ritual is successful, with these emotions also feeding back on one another in a chain (Collins, 2004). Within the study of religion and religious experiences, similar notions have also been expressed, with the Ancient Greek concept of ekstasis (εκστασις) holding similar connotations to collective effervescence in terms of emotional experience. It represents a desire to “step outside” of oneself to experience something bigger, such as the Divine, with this often occurring when engaging in spiritual practices (Armstrong, 2010). Such experiences are also characterised as having an indescribable emotional quality—they are ineffable (James, 1983; Armstrong, 2010). Yet, while ekstasis is often experienced at an individual level, it can happen at a communal level too, whereby the collective go together “into the darkness which is beyond intellect” (Armstrong, 2010). Importantly, ekstasis has been argued as relevant to understanding secular rituals, such as those connected to music, dance, art, or sports engagement (Armstrong, 2010). What the concepts of collective effervescence and ekstasis show is that it is through shared, heightened emotional experience that individuals are bound together through interaction rituals in a way that may support social solidarity.

Collective effervescence is also premised on shared values and beliefs, and rituals have a moral character to them (Durkheim, 2001). Building on this, Collins (2004) argues that interaction rituals are the source of a group's morality (p. 39), and that righteous anger may be experienced by those involved in a group with strong solidarity when there are violations to the shared moral code (that may or may not be explicit and known to those engaging in the ritual). A further reason that rituals become imbued with meaning is therefore because they are cultural phenomena, reflecting and reproducing meanings, morality, beliefs, and values about the societies in which they manifest. As Durkheim (1953) observed, “things in themselves have no value” (p. 86) and it is society that attributes meaning, with what is sacred becoming so through the collective practices of the moral community. Emotions and morality are deeply intertwined and upheld within ritual participation.

Emotional intent (shared mood, intention, attention), emotional experience (collective effervescence, ekstasis) and emotional energy are therefore key facets of understanding and explaining how interaction rituals—whether religious or secular—become meaningful within a cultural context, and when rituals may (or may not) contribute to our meaningful social lives.

The social determinants of health and the social cure

If socioemotional interactions are the bedrock of meaningful rituals, then there may be a clear doorway to understanding why rituals are important to our health and wellbeing (Charles et al., 2021; VanderWeele, 2017). In recent years there has been increased understanding that there are social determinants of health, framed within a biopsychosocial model (rather than a biomedical model) where social factors are understood as core to our health, wellbeing and quality of life. This has included an understanding of how social inequalities, social environments, social networks, and acquisition of social capital all play a role in the prevention, management and treatment of ill health and in improving and sustaining wellbeing (Marmot, 2005; Marmot et al., 2012). Within this landscape, the study of social isolation and loneliness has suggested that being lonely is detrimental to health, with loneliness having the same effects as smoking 15 cigarettes a day (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). Epidemiological data has shown that “close relationships” are more important to our health and happiness than money or fame (Waldinger and Schulz, 2023). Relevant to this discussion, Berkman et al. (2000) draw on Durkheim and Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980) to present a conceptual model for how social networks impact health. Recognising that there is a dynamic relationship between macro-level structural conditions and individual psychobiological processes, it is suggested that networks affect health through provision of social support, promoting social participation, person-to-person contact (e.g., restricting or promoting exposure to infectious diseases), and access to material goods, resources and services. Further, a number of studies have explored the role of collective emotions, such as experiences of collective effervescence at gatherings, in improving wellbeing, self-esteem and self-efficacy (at individual and collective levels), all of which are important to health (Páez et al., 2015; Pizarro et al., 2022). Even the language of “social glue” has been used to describe the role that arts and culture have in contributing to the wellbeing of people living in a city—a sentiment that is reminiscent of Durkheim's collective effervescence (Parkinson, 2022). There are clear undertones of the role of interaction rituals as social determinants within this literature.

In view of the increasing emphasis on social factors to our health and wellbeing, a “social identity approach to health” has been put forward which suggests that engaging with meaningful groups that enable group identities and cohesion to form may provide important psychological resources that can support health and wellbeing. This approach—known as the social cure—combines two theories from social psychology (social identity theory and self-categorisation theory) to argue that meaningful identification to groups (e.g., a sense of group belonging) can reduce loneliness and support mental health (Jetten et al., 2012). “Social identity” is an internalised group membership that contributes to a person's sense of “who they are” in a given context,” with an individual's self-identity viewed in terms of meaningful relations with others in group contexts (Haslam et al., 2018, p. 15). This builds on Tajfel's (1972, p. 292) assertion that belonging to certain social groups may have emotional or value significance that contribute to the construction of a social identity (Haslam et al., 2018, p. 15). Meaning and emotions, as we saw within the literature on rituals, are therefore central concepts within the social cure approach because it is when individuals are able to experience group-based interactions as purposeful that benefits for health are seen (Haslam et al., 2018, p. 17).

Notions of purpose have clear links to what is experienced as meaningful in view of eudaimonic wellbeing too: a concept with roots in Aristotle that denotes fulfilment of human potentiality, flourishing, and the attainment of human wellness, including self-realisation (Ryan et al., 2013; Tennant et al., 2007). A sense of meaning and purpose may lead to fulfilment, growth, and flourishing, experienced as eudaimonic wellbeing. There's a further link to emotions here as well, with it suggested that positive emotions build meaning, and forecast and cause increases in eudaimonia (Fredrickson, 2016). In this sense, deriving a sense of purpose from group-based interactions may affect psychological aspects of wellbeing too, with social identity theorists suggesting that meaningful group interactions enable individuals to derive psychological or emotional resources that support health at multiple levels; for example, provision of a sense of collective meaning, purpose, personal agency, belonging, social support, and efficacy (Forbes, 2020; Haslam et al., 2022). In the context of ritual, group identity is considered a “group emblem” (2004, p. 36–37), contributing to important meaning-making practices upheld across chains of interactions, and in the social cure literature this identity is internalised to support health. In other words, combining these theories may make it possible to argue that the social and wellbeing “outcomes” of the social cure are somewhat reminiscent of interaction ritual outcomes (Stige, 2010).

In sum, it is clear that there are key analytic links between (micro)sociological understandings of ritual and a “social cure” approach. On the one hand, emotionally meaningful social interactions in face-to-face rituals build up to provide powerful emotional energies at an individual level, in addition to building social identities, social cohesion and social solidarities—holding society together and acting as a “social glue.” On the other hand, meaningful social identities and a sense of belonging can become internalised to construct personal identities and provide psychological and emotional resources that support health and wellbeing. This is the central theoretical argument of this paper that facilitates a foundation to link the arts to health through ritual: meaningful interaction rituals are crucial to our health and wellbeing.

Bringing in the arts: meaningful chains of interaction rituals that interconnect with health and wellbeing

The idea of “the arts as ritual” is not new and is explored within literature on ancient rituals and community. Within the study of religion, history of art, and cultural anthropology, the relational aspects of the arts as core to ritual and community-building are well documented (Camlin et al., 2020; Chernoff, 1979). From within anthropology, arguments have also been proposed that the arts are an evolutionary behavioural adaptation, examining musical interactions between mothers and infants as examples of social rituals that enhance social bonding and cohesion (Dissanayake, 2004, 2009). Further, the issue of art is implicit in Elementary Forms: collective effervescence is key to “all kinds of things, not just society and religion, but art, symbolism, conceptual thought and science” (Watts Miller, 2013, pp. 17, 41). There are also a small number of studies that have applied the concept of interaction ritual to arts' contexts (e.g., Benzecry and Collins, 2014; Heider and Warner, 2010). However, very little research has explored how the rituals embedded in artistic experiences may foster social cohesion in a way that may intersect with experiences of health and wellbeing, and micro-sociological understandings of interaction rituals are rarely developed in this context.

Yet, there are some publications that are relevant to this discussion, and several that have laid a foundation for the discussion of this article. Firstly, there is a body of literature from within the arts therapies that could be explored and applied to broader arts and health contexts. For example, work by Kenny (1982, 1989) drawing on anthropological understandings of ritual to theorize ritual as an element of therapy practice which describes the therapist as a “ritualist.” This foundation is developed by Aigen (1991) who draws a parallel between music therapy and shamanic activity, informed by the importance and meaning of ritual (Aigen, 1991). Ruud (1998) has also explored the liminal components of musical improvisation as a “transitional ritual” (p. 121), focusing on the transformative potential of music therapy. This literature could be viewed in the context of micro-sociological conceptions of interaction ritual to deepen understanding of how these rituals work, such a theorizing the role of the therapist as an important ritual ingredient in constructing therapy rituals or seeing liminality as a core process of transformation across chains of interaction rituals. However, while the relevance of this literature to broader arts and health contexts is palpable, the application of it is sparse. Further, arts therapy work on ritual has tended to focus less on the potential importance of building social cohesion across chains of interactions to health, staying close to the therapy context and drawing on anthropological understandings (rather than looking at the relevance of secular interaction rituals to broader arts and health contexts).

Looking to the literature relating to arts and health, there is a small body of literature from within positive psychology that has theorized arts activities as structured practices that link to wellbeing, whereby there are some theoretical similarities to a conceptualisation of interaction ritual. For example, Martin Seligman's (2011) PERMA model of wellbeing has been drawn upon to argue that the practice of music (Croom, 2012, 2015a), the practice of poetry (Croom, 2015b), and the practice of martial arts (Croom, 2014) can be understood as meaningful, socially supportive processes that support the subcomponents of wellbeing. “Enactment of ritual” is also mentioned as a potential mechanism linking leisure activities (which includes arts engagement) to health and wellbeing in a narrative review (Fancourt et al., 2020) and ter Kuile (2020) links rituals to wellbeing, suggesting that everyday activities can be infused with meaning to reduce feelings of social isolation and create a sense of community, including arts engagement as examples of such everyday practices. Other examples include the use of narrative and expressive arts as rituals that create meaning and connection in a way that enables intersubjective telling of stories, empathy, and healing in palliative care (Romanoff and Thompson, 2016) and art-making as part of a ritual that supports unity, reduces anxiety, and provides feelings of safety through transitions (Koch, 2017). Further, there are a range of arts and health studies that could be theorized as relevant to a discussion on secular ritual, such as work exploring solidarity (Lee and Northcott, 2020), collective identities (Parkinson et al., 2019), and group meaning (Finn et al., 2023). Nevertheless, overall, the mention of “ritual” in these studies is either absent or brief, and the potential of secular ritual, notably interaction ritual, as a core theoretical concept is untapped.

There is one notable exception to this, and the research is, again, from the music therapy literature. Stige (2010) applies Collins' theory of IRCs to the context of a group music therapy “festival” where he argues that “the ritual outcomes are the therapeutic outcomes” and that music participation was a form of ritual negotiation (Stige, 2010). Rituals are argued as being “supportive contexts” that may enable “community, creative and critical processes,” drawing on a notion of rituals as “secular traditions” (e.g., using Durkheimian sociology). In this sense, Stige (2010) acknowledges a social model of health, whereby feelings of membership, solidarities and the creation of social relationships through music underpin therapeutic processes that support health and wellbeing. Although his emphasis and language are on “therapy,” rather than broader health and wellbeing benefits, the links are clear, and it provides an interesting foundation to reflect on how this work may have relevance in other artistic contexts.

In my own research, I have studied IRCs in the context of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe (the world's largest arts festival), whereby I found that groups (community groups and professional performing companies) who engaged with the Fringe experienced shared emotions and challenges that fostered feelings of group solidarity and group identity, as well as the embodiment of this shared identity (Warran, 2021). Social relationships within groups and to others in broader networks at the Fringe deepened (Warran, 2021). The groups also shared a sense of group morality in view of shared beliefs around the value of the Fringe and, more broadly, engaging in the arts (Warran, 2021). While I was not specifically looking at the relationship between engagement in the Fringe and health and wellbeing, it is my view that the findings from this research could be re-constructed within the context of a social identity approach to health to theorize that the interaction rituals of groups engaging in the arts may construct meaningful identities that are embodied in ways that could be understood as psychological resources important to health—which represents a theoretically different way of looking at the same findings (see Appendix for an example). Further empirical research would be needed to delve into this further, but given the clear “social” processes of arts engagement and the broader research showing the importance of these social factors to health, including application of the “social cure” in the context of the arts (Finn et al., 2023; Forbes, 2020; Williams et al., 2020) and a recent review including 18 articles highlighting the relationships between arts participation, social cohesion, and wellbeing (Sonke et al., 2024), the theoretical interconnections are clear.

Yet, it is also important to note that just because I found that engagement in the Fringe could foster group solidarity, there were also clear cases where this did not happen. For one group, the identity fostered through their engagement with the festival was that “it's not for us,” with their sense of solidarity coming from their engagement with their local community group, rather than with the festival (Warran, 2021). This suggests that solidarities are interconnected with shared emotions, morality, and beliefs, and that these shared processes may or may not align with that of an arts experience for a group (Warran, 2021). As explored by McCormick (2015) in the context of international music competitions, performances are contingent processes that exist within complex societies; competing moral frames occur, resulting in a need for “a project of re-fusion” where some features may be fused and others not, with collective effervescence existing alongside “deflation and estrangement” (McCormick, 2015, p. 22). Thus, even if an argument can be made that the construction of social identities through arts engagement can provide a theoretical link to the role of interaction rituals in supporting and maintaining health and wellbeing across chains of interactions, this does not mean that arts engagement will always do this. As noted by Collins (2004), there are particular ritual ingredients that are needed to lead to successful rituals. And similarly, within the health literature, it has been suggested that certain combinations of “active ingredients” (the elements of an activity responsible for its therapeutic action) are needed to lead to health and wellbeing outcomes, also explored within the context of arts activities (Warran et al., 2022).

Ritual as transformation through the arts

Ritual has been theorized as a process or structure that can aid with transitions, transformation, restoration or recovery (e.g., some form of change) within the context of health. Atkinson (2012) has highlighted how micro-rituals facilitated by arts practitioners for primary school children (e.g., start-up activities, games, closing activities) support with enabling “wellbeing gains” to be transferred and integrated into the classroom. Practitioners use ritualised practice as a means to establish the boundaries of arts activities and create spaces for meaningful engagement (Atkinson, 2012). Harris (2009) has described rituals as having an “incomparable model for therapeutic intervention in the wake of disaster” which offers a release of emotions associated with trauma, offering possibility for restoration (Harris, 2009). This is also a similar argument to West and Fewster (2021) who state that performing arts aid recovery through “creativity being embraced as a source of ritual escape and a way to reimagine the self.” Although this literature is not specifically positioned within an understanding of interaction rituals, this sense of “transformation” could be repositioned as a ritual outcome (i.e., as per the outcomes of Collins' model) that underpins positive therapeutic change and, consequently, benefits to health and wellbeing.

Explaining this further, these theorizations of how rituals facilitate change are reminiscent of Turner's work on liminality and communitas, also referenced in these studies, and van Gennep (1909)'s Rite of Passage. Communitas is an unstructured state (“antistructure”) that contrasts a structured community, providing opportunities for the creation of meaningful connections through liminal (transient/transitionary) spaces and states (Turner, 1975).

There are numerous studies within the arts, community arts, and arts and health that have suggested that engagement with the arts can foster communitas (Raw et al., 2012; Raw and Mantecón, 2013; Warran and Wright, 2023; White and Hillary, 2009), also explored within the context of an “arts activist application of secular ritual,” exploring how communitas can frame the creative journey to open up potential for imagining “different everyday ‘structures”' (Raw, 2013, p. 356). Further, van Gennep's (1909) Rite of Passage explores how ceremonies such as baptisms, weddings, and graduations symbolise the transition from one identity to another. There are different stages of a rite of passage, with a kind of liminality between an old and new identity as persons experience transition (van Gennep, 1909). Such a process aligns well, and upholds, a broader discourse in policy that underpins the arts and health field which constructs the arts as “transformative.” In the Culture Strategy for Scotland it states that “transforming through culture” is a priority ambition for Scotland, emphasising the power of the arts to be transformative in the context of health and wellbeing, the economy and education, as well as playing a role in “reducing inequality and realising a greener and more innovative future” (The Scottish Government, 2020). This kind of language is furthermore echoed nationally, such as through the language of the arts as “promoting healing” and being “a means of empowerment” (All-Party Parliamentary Group for Arts, 2017, p. 20). Much of the literature on arts events, including my own research of festivals, could be viewed as an “occasion” that provides an opportunity for such transformation (Warran, 2021). Yet, once again, it is important to note that the arts will not always be transformative, and that belief in such a transformation is deeply interconnected with the shared moralities, beliefs, emotions, and experiences of those who engage. While acknowledging this, however, the concept of “transformation,” which is embedded within and across the literature on rituals, arts, and health, once again, provides a foundation on which to build a theory that links the arts to health through meaningful interaction rituals.

Social interactions as inseparable from artistic experiences

Something important to note here is that interaction rituals in the arts need not necessarily be bounded by the context of the arts engagement itself. Not every ritual will have a high ritual intensity, leading to collective effervescence and feelings of transformation. Everyday micro-rituals across time and contexts may build up more slowly to construct situations that are conductive to the arts fostering group solidarity across time. This was certainly the case in my research on the Fringe, whereby what may be described as “non-arts” rituals of tourism and socialising contributed to the meaning that was attached to the Fringe by groups (Warran, 2021). Something similar has also been suggested with use of the language of “moment” in the context of arts and dementia. A “moment” is considered a basic unit for creative expression and provision, sustained through interactional processes of meaningful exchange, and these moments may happen across a continuum of moments (Dowlen et al., 2021; Keady et al., 2022). This is somewhat similar to a meaningful interaction ritual taking place across a “chain” of situations as per Collins' (2004) theory. Thus, if we are to theorize that micro-rituals in the arts could be foundational to health and wellbeing, then looking across situations and contexts, and understanding the contribution of so-called “non-arts” rituals that lead up to a meaningful engagement with the arts that connects to health, is going to be vital.

Nonetheless, it's important not to be too causal when interpreting this discussion of literature on micro-rituals, such as suggesting that there is a linear link between the arts leading to an interaction ritual which leads to improved health outcomes, and that this will build up across time. Ritual processes are deeply interconnected with emotions, beliefs, contexts, and cultures, and our social interactions are inseparable from our artistic engagements. As Acord and Denora (2008) note, art becomes meaningful in interaction—it is not separate from our social engagement. In a similar vein, our experiences and expressions of health are also not separate from our interactions and experiences. Put simply, art can never be an isolated “input” and health an “output” because these experiences are intertwined and inherently part of our social life, embedded within our ritual participation.

Combining interaction ritual chain theory and the social cure to link the arts to health

Thus far in this article I have demonstrated that there are theoretical similarities across the literature in social psychology, sociology, and health that may provide a foundation to link arts, interaction rituals, and health. Although different language is often used, with sociologists tending to focus on social solidarity, emotions, and social integration, and social psychologists focusing more on social identity and psychological resources, by taking a foundation of a social identity approach combined with theories of “secular” rituals, notably from Goffman, Durkheim, and Collins, it seems plausible to suggest that engagement in arts activities may construct ritual outcomes in ways that provide psychological resources that improve health. Restating the words of Stige (2010) to emphasise their significance to this proposition: “the ritual outcomes are the therapeutic outcomes.” As I too argue and develop, the ritual outcomes are expressions of our health and wellbeing. But we can be more specific regarding how these processes of ritual and the social cure may link together in the context of arts and health through re-visiting Collins (2004) emotional-entrainment model and reframing it in view of the social cure approach.

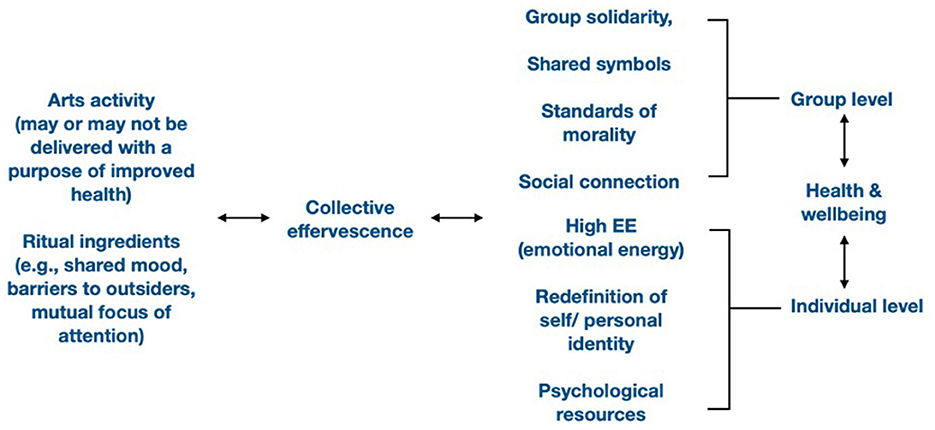

In the context of an arts activity, which may or may not be delivered in a way that intends to create “health” outcomes, where there are ritual ingredients present (such as shared mood and mutual focus of attention; Collins, 2004) whereby collective effervescence underpins the construction of a group identity (i.e., as theorized in a social identity approach to health) and other ritual outcomes (such as social solidarity; Collins, 2004), such ritual outcomes may be internalised as emotional energy (Collins, 2004) and psychological resources that may support health and wellbeing (i.e., the social cure). These different stages in the ritual may also feed back and reinforce one another across chains of situations to maintain meaningful interactions across different contexts, also recognising that arts engagements happen within our interactions. Figure 1 has been included to visually depict how these links between interaction rituals and health could be theorized, and a case example is included in the Appendix that descriptively explores these connections further using a real-world example.

Figure 1. Combining Collins' emotional-entrainment model with the social cure approach to theoretically link the arts to health through interaction ritual. As per Collins (2004, p. 48), the situation of the interaction ritual involves two or more people gathered to engage in a common action or event. In this case, the event is an artistic engagement. Many arts programmes in recent years have been delivered with a specific health outcome or purpose in mind as part of an arts and health initiative but, within research and evaluation, arts activities that do not have such a focus can still be examined for their health impacts, whether retrospectively or in-situ. Through engagement with such an arts activity, it is possible (although contingent on the situation and context) for ritual ingredients such as shared mood and mutual focus to build up and lead to heightened emotional experiences of collective effervescence. Such an experience leads to ritual outcomes at a group and individual level. At the group level, this could be theorized as group solidarity, social cohesion, or social connections, and at the individual level as emotional energy, changes to personal identity, and the acquisition of psychological resources, as understood through combining IRC theory with the social cure approach. These different processes reinforce on one another, with feedbacks building up across chains of situations and creating the potential to support health and wellbeing at group and individual levels.

But what about the shared morality of “arts and health” rituals? The existence of the field of arts and health is one telling feature of what might underpin the shared morals of those who engage in arts rituals and experience health benefits. As argued by Williams (2022), the notion of “arts and health” has been constructed through political, economic, and social movements during times of austerity and cuts to public spending, whereby the celebratory narratives around the role of arts in health have thrived. A report from the Culture Health and Wellbeing Alliance also noted that people working in the arts and health field speak of “being evangelical about the arts for living well” and having “faith… in the joy it brings people” (Hume and Parikh, 2022, p. 22). This pseudo-religious language suggests a moral assertion that the arts are intrinsically “good” and able to provide transformation in our culture. Finally, this reinforces my own research on arts festivals, whereby those who engaged in meaningful rituals in the context of arts festivals did so in view of a shared belief in the intrinsic values of the arts and their transformative potential as part of what I theorize as a “moral community of the arts” (Warran, 2021). Thus, it is possible that those who benefit from arts and cultural engagement enter into a pervading discourse that they are “good” and reaffirm this through their ritual participation across chains of interactions.

Yet, this article is conceptual and what I have theorized here needs to be explored further in empirical research. Indeed, a focus on exploring secular rituals in arts and health could open out innovative questions and methodologies that are underexplored in the field. Given the need to understand interactions across multiple contexts when employing IRC theory, ethnography has been a popular methodology in previous studies examining IRCs. While this is a methodology utilised in arts and health, it has been argued that there is a need for more ethnographic work to go “beyond outcome measures” in the context of understanding the impact of the arts (Crossick and Kaszynska, 2016, p. 142). A focus on chains of interactions across situations provides a rationale and foundation in which to build ethnographic designs.3

It will also be important for future research to explore exactly what arts' ritual ingredients and ritual outcomes are needed to construct identities in ways that do provide psychological resources, and what characterises the shared moralities of those who engage. Further, there needs to be deeper exploration of the similarities between EE and psychological resources regarding whether EE could be viewed as such a resource, or whether it offers something emotionally different in the context of its potential link to health and wellbeing. And more research needs to be carried out to better understand specifically what it may be about arts engagement (as opposed to other social activities) that may set the stage for meaningful interaction rituals to happen, such as building on previous research on the active ingredients of arts and health activities (Warran et al., 2022). Finally, more research is needed to explore the different “social levels” of rituals in arts and health, exploring whether ritual ingredients and mechanisms vary in arts and health within and across micro, meso, and macro interactions. In this article, I have primarily focused on literature that has explored the micro-level of interaction rituals, and it is important for future research to unpack how larger scale rituals may operate in arts and health contexts (e.g., the role of the arts during the COVID-19 pandemic; large scale community arts events such as concerts).

Why is linking arts, secular ritual, and health important?

In short, this theorization is important to the field of arts and public health. Over the last 50+ years, there has been a growing shift from a biomedical approach to a biopsychosocial approach that acknowledges social factors as important to health and wellbeing, alongside consideration of biological and psychological factors (Borell-Carrió et al., 2004; Engel, 1980). This is a more “holistic” approach to health and social care, also aligning with the World Health Organization's definition of health as complete physical, mental and social wellbeing (World Health Organization, 1948). More recently, the arts have been considered part of this picture of holistic health and wellbeing, whereby the arts are increasingly being understood as a health behaviour (Fancourt and Finn, 2019; Rodriguez et al., 2023). But the “social” of the “biopsychosocial” has tended to be considered in view of social support, social identities, and social relationships, rather than considering the role of secular micro-rituals and culture in how these social processes form and are maintained. As has been demonstrated in this article, through working in an interdisciplinary way to incorporate the role of interaction ritual chains within arts and health, it may be possible to explore how to improve equitable public health delivery. This is because studying micro rituals involves looking at shared cultural symbols, meanings, values, beliefs, and morality, and being transparent about the kinds of artistic engagement that are constructing meaningful social identities and for whom, recognising that different interaction rituals are meaningful for different cultural groups. Moreover, by seeing the arts as part of the “social glue” of society that is fostered through rituals at different social levels, we begin to see health as something deeply interconnected to our everyday cultural practices and the concern of every aspect of society, rather than hidden away in health and social care institutions. Such an understanding could be incorporated into future empirical research and evaluation on arts and health to better understand why the arts are important to health and how culture and society facilitate (or impede) arts engagements that are supportive of health, wellbeing, and flourishing.

Why is the language of interaction ritual theory important?

While there are some theoretical overlaps in relation to how meaning connects to wellbeing from within other theories and disciplines, the contribution of language and concepts from interaction ritual theory to the field of arts and health serves to further expand thinking and centre processes of interactions between people at an intersubjective level. Essentially, IRCs can support with being more specific about the mechanisms underpinning processes of connecting the arts, meaning, and health and wellbeing, as well as explore such processes across time and situations. Moreover, interaction ritual theory does not prioritise positive emotions, as has often been the case in previous work, such as research exploring structured practices drawing on the PERMA model. Instead, in interaction ritual theory, “emotional intensification” is understood as “any intensification of a shared mood that occurs when certain micro-processes of social interaction take place in everyday life” (Collins, 2014, p. 299, my emphasis), therefore also including what may be perceived as negative emotional experiences. Relatedly, in the PERMA model, meaning is defined as “belonging to and serving something that you believe is higher than the self” (Seligman, 2011, p. 27). It has “a subjective component” and may be “subsumed into positive emotion” (Seligman, 2011, p. 27). IRCs, instead, prioritises the intersubjectivities of meaning, and the processes of meaning-making between people, whereby a range of emotions may play a role in what is considered meaningful. As such, it builds on literature in positive psychology to take a more nuanced approach to understanding how and why the arts may connect to health and wellbeing, incorporating a range of intersubjective emotional experiences across chains of interactions. It is a sociology of situations that serves to uncover “the social sources of the cult of the individual' (Collins, 2004, p. 4), expanding individualistic conceptions of what constitutes meaning and how it is (co)created within interactions.

The theoretical model proposed here also serves to make a unique theoretical contribution to social psychology, combining commonly used theories in social psychology (e.g., social identity theory, self-categorization theory) with Interaction Ritual Chain theory in an innovative way. While Collins' (2004) theory can be seen as cutting across microsociology and social psychology, Collins describes it as a “full scale social psychology” (p. 44), with it able to delve deeply into the interplay between individuals, their interactions with one another, and the broader context in which these interactions emerge. Yet, in social psychological studies of arts and health, Interaction Ritual is rarely drawn upon. Given the growing interest in the social cure approach in arts and health in recent years, the addition of interaction ritual chain theory serves to add new theoretical insights and opportunities for empirical work. For example, in previous studies applying the social cure to arts and health, variables such as group identification, group closeness, psychological needs satisfaction, collective efficacy, and mental health and wellbeing have been explored in quantitative studies (Draper and Dingle, 2021; Finn et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2019), and experiences of taking part or identifying with a group explored in qualitative studies (Forbes, 2020; Williams et al., 2020). These foci could be complemented with exploring measures of social interaction and EE to embed IRC theory within future work. For example, adding observations of bodily postures and movements or measurement of hormone levels (e.g., via blood or saliva) to observe changes to EE (suggested by Collins, 2004, p. 133-140), quantitative measures of social interaction and emotional synchrony (as explored in previous studies such as by Hudson et al., 2019, Marques et al., 2021, and Xie and Li, 2023), as well as qualitative exploration of symbols of membership, morality, and the meanings connected to group belonging. Through empirical exploration of how these theories intersect, there is enormous potential to measure mechanisms of change to health and wellbeing in arts and health studies as dimensions of meaningful secular rituals.

Conclusion

Literature from across social psychology, sociology, art therapies, and arts and health presents a foundation to suggest that “interaction ritual” has a central role to play in our understanding of how and why the arts connect to health and wellbeing. There are various bodies of literature that have indirectly explored links between artistic, ritual, and social processes and health. However, articulating such processes more clearly as markers of interaction ritual opens the door to the construction of a theoretical foundation that could be employed in future designs in arts and health to improve our understanding of how the arts link to health, thereby informing policy and practice. More specifically, Interaction Ritual Chain theory and the social identity approach to health display some similarities (albeit using different language) that could be viewed as arguing that ritual outcomes may be supportive of health and wellbeing through the construction of shared social identities. Given previous research has demonstrated that arts activities may be understood as forms of meaningful ritual engagement that create social identities, there is a clear rationale to suggest that “interaction ritual” could be a useful analytic lens to more deeply understand the relationship between the arts and health.

Thus, this article makes an original contribution to social psychology by combining interaction ritual chain theory with a social identity approach to health, using an original example from the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and distinguishing the work from other models of psychological wellbeing such as the PERMA model in positive psychology. Such theorization is useful for social psychologists working in the field of arts and health, such as those working in the developing space of applying the social cure approach to arts and health interventions and contexts. The work serves to deepen understanding of the potential mechanisms underpinning how art affects health, integrating mechanisms across the social cure and interaction ritual chain theory, and proposing a theoretical model that could be tested empirically. For example, exploring IRs as mechanisms of change alongside pre-existing theorized mechanisms in social psychology linked to the social cure (e.g., group identification, social support).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KW: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. KW was supported by a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship [ECF-2023-715] and an Arts and Humanities Research Council grant [AH/X012743/1].

Acknowledgments

KW would like to thank Dr Giorgos Tsiris for his time, expertise, and insights during the development of this article, including reviewing it ahead of submission. She would also like to thank the handling editor for this article, Dr Adam M. Croom, whose care, attention, and insights greatly helped to develop the work. She would also like to thank Dr Lisa McCormick and Prof David Stevenson (academic supervisors) and Lyndsey Jackson (industry supervisor at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe Society) who supervised the doctoral work referenced in the article. Finally, KW would like to thank Samuel Maggs, Gig Buddies Project Manager for Thera Trust, and all Gig Buddies' members who participated in the data collection that informed the case study included in the Appendix.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Sassatelli (2011) made a similar argument to this in her exploration of urban festivals, suggesting that “because contemporary, post-traditional festivals have lost their close association with religion… they have escaped the sociologist's attention and have been dismissed as not equally revelatory of society's self-representation when compared with their traditional forebears.” Yet, drawing on Simmel, she argues that such festivals are “still sociologically fundamental” and are “a crucial indicator of a society's character according to the specific forms it assumes” (p. 14).

2. ^It should be noted that this has also been a criticism of Collins' (2004) theory. Smith and Alexander (2019) have argued that his theory adopts a “mechanistic and often cynical model of human interaction and emotion” (p. 8), placing too much emphasis on individual and emotional needs. By theorizing rituals as having “outcomes”, this could also be viewed as aligning too readily with simplistic, instrumental models of arts and health that do not account for the complexity and importance of processes. Yet, within Collins' theory, these outcomes should always be viewed in a chain. As such, interaction rituals, and their ritual outcomes, are a “set of processes with causal connections and feedback loops among them” (Collins, 2004, p. 47). Through this processual lens, the ‘mechanistic' quality of Collins' theory supports interpreting complex arts and health engagements, having a practical applicability – a strength in the applied field of arts and health.

3. ^Collins (2004) outlines a range of empirical ways through which to measure emotional energy (EE), including self-report, hormone levels, and tracking eye contact. Such methods could be explored in future research in arts and health to explore secular rituals.

References

Abbott, A. D. (2004). Methods of Discovery: Heuristics for the Social Sciences. W.W. Norton and Company.

Acord, S. K., and Denora, T. (2008). Culture and the arts: from art worlds to arts-in-action. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 619, 223–237. doi: 10.1177/0002716208318634

Aigen, K. (1991). The voice of the forest: a conception of music for music therapy. Music Ther. 10, 77–98. doi: 10.1093/mt/10.1.77

All-Party Parliamentary Group for Arts H. and W. (2017). Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing. London: All-Party Parliamentary Group for Arts.

Atkinson, S. (2012). Arts and health as a practice of liminality: managing the spaces of transformation for social and emotional wellbeing with primary school children. Health Place 18, 1348–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.06.017

Benzecry, C., and Collins, R. (2014). The high of cultural experience. Soc. Theory 32, 307–326. doi: 10.1177/0735275114558944

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., and Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 51, 843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4

Borell-Carrió, F., Suchman, A. L., and Epstein, R. M. (2004). The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann. Fam. Med. 2:576. doi: 10.1370/afm.245

Brossard, B., and Sallée, N. (2019). Sociology and psychology: what intersections? Eur. J. Soc. Theory 23, 3–14. doi: 10.1177/1368431019844869

Camlin, D. A., Daffern, H., and Zeserson, K. (2020). Group singing as a resource for the development of a healthy public: a study of adult group singing. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Comm. 70:60. doi: 10.1057/s41599-020-00549-0

Charles, S. J., van Mulukom, V., Brown, J. E., Watts, F., Dunbar, R. I. M., and Farias, M. (2021). United on sunday: the effects of secular rituals on social bonding and affect. PLoS ONE 16:e0242546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242546

Chatterjee, H. J., Camic, P. M., Lockyer, B., and Thomson, L. J. M. (2018). Non-clinical community interventions: a systematised review of social prescribing schemes. Arts Health 10, 97–123. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2017.1334002

Chernoff, J. M. (1979). “African rhythm and African sensibility: aesthetics and social action,” in African Musical Idioms. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Collins, R. (2004). Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400851744

Collins, R. (2014). “Interaction ritual chains and collective effervescence,” in Collective Emotions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199659180.003.0020

Croom, A. M. (2012). Music, neuroscience, and the psychology of well-being: a precis. Front. Psychol. 2:393. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00393

Croom, A. M. (2014). Embodying martial arts for mental health: Cultivating psychological well-being with martial arts practice. Arch. Budo Sci. Martial Arts Extreme Sports 10, 59–70.

Croom, A. M. (2015a). Music practice and participation for psychological well-being: a review of how music influences positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. Music Sci. J. Eur. Soc. Cognit. Sci. Music 19, 44–64. doi: 10.1177/1029864914561709

Croom, A. M. (2015b). The practice of poetry and the psychology of well-being. J. Poet. Ther. 28, 21–41. doi: 10.1080/08893675.2015.980133

Crossick, G., and Kaszynska, P. (2016). Understanding the value of arts and culture: the AHRC cultural value project. Available from: http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/documents/publications/cultural-value-project-final-report/ (accessed August 7, 2024).

Dissanayake, E. (2004). Motherese is but one part of a ritualized, multimodal, temporally organized, affiliative interaction. Behav. Brain Sci. 27, 512–513. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0432011X

Dissanayake, E. (2009). “Bodies swayed to music: the temporal arts as integral to ceremonial ritual,” in Communicative Musicality: Exploring the Basis of Human Companionship, eds. S. Malloch and C. Trevarthen (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 533–544. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198566281.003.0024

Dowlen, R., Keady, J., Milligan, C., Swarbrick, C., Ponsillo, N., Geddes, L., et al. (2021). In the moment with music: an exploration of the embodied and sensory experiences of people living with dementia during improvised music-making. Ageing Soc. 42, 1–23. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X21000210

Draper, G., and Dingle, G. A. (2021). “It's not the same”: a comparison of the psychological needs satisfied by musical group activities in face to face and virtual modes. Front. Psychol. 12:1565. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646292

Durkheim, É. (1953). Value judgments and judgments of reality,” in Sociology and Philosophy, ed. D. F. Pocock (London: Routledge Revivals, Cohen and West), 80–96.

Engel, G. L. (1980). The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am. J. Psychiatry 137, 535–544. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.5.535

Fancourt, D. (2017). Arts in Health: Designing and Researching Interventions. Oxford: OUP. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198792079.001.0001

Fancourt, D., Aughterson, H., Finn, S., Walker, E., and Steptoe, A. (2020). How leisure activities affect health: a review and multi-level theoretical framework of mechanisms of action using the lens of complex adaptive systems science. Lancet Psychiatry. 8, 329–339. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30384-9

Fancourt, D., Bhui, K., Chatterjee, H., Crawford, P., Crossick, G., DeNora, T., et al. (2021). Social, cultural and community engagement and mental health: cross-disciplinary, co-produced research agenda. BJPsych Open 7:e3. doi: 10.1192/BJO.2020.133

Fancourt, D., and Finn, S. (2019). What is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving health and Well-being? A Scoping Review. WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Evidence Network synthesis report no. 67). Copenhagen.

Fancourt, D., and Warran, K. (2024). A fRAmework of the determinants of arts aNd cultural engagement (RADIANCE): integrated insights from ecological, behavioural and complex adaptive systems theories. Wellcome Open Res. 9:356. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.21625.1

Finn, S., Wright, L. H. V., Mak, H. W., Åström, E., Nicholls, L., Dingle, G., et al. (2023). Expanding the social cure: a mixed-methods approach exploring the role of online group dance as support for young people (aged 16–24) living with anxiety. Front. Psychol. 14:1258967. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1258967

Forbes, M. (2020). “We're pushing back”: group singing, social identity, and caring for a spouse with Parkinson's. Psychol. Music 49, 1199–1214. doi: 10.1177/0305735620944230

Fredrickson, B. L. (2016). The eudaimonics of positive emotions,” in Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-Being. International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life, ed. J. Vittersø (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-42445-3_12

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction Ritual: Essays in Face to Face Behavior, 2005th Edn, ed. J. Best. New York, NY: Aldine Pub.

Gray, C. (2010). Analysing cultural policy: incorrigibly plural or ontologically incompatible? Int. J. Cult. Policy 61, 215–230. doi: 10.1080/10286630902935160

Han, J., and Patterson, I. (2007). An analysis of the influence that leisure experiences have on a person's mood state, health and wellbeing. Ann. Leisure Res. 10, 328–351. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2007.9686770

Harris, D. A. (2009). The paradox of expressing speechless terror: ritual liminality in the creative arts therapies' treatment of posttraumatic distress. Arts Psychother. 36, 94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2009.01.006

Haslam, C., Jetten, J., Tegan, C., Dingle, G., and Haslam, A. (2018). The New Psychology of Health: Unlocking the Social Cure. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315648569

Haslam, S. A., Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., Jetten, J., Bentley, S. V., Fong, P., et al. (2022). Social identity makes group-based social connection possible: implications for loneliness and mental health. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 43, 161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.013

Heider, A., and Warner, R. S. (2010). Bodies in sync: interaction ritual theory applied to sacred harp singing. Soc. Religion 71, 1–76. doi: 10.1093/socrel/srq001

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., and Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Hudson, S., Matson-Barkat, S., Pallamin, N., and Jegou, G. (2019). With or without you? Interaction and immersion in a virtual reality experience. J. Bus. Res. 100, 459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.062

Hume, V., and Parikh, M. (2022). From surviving to thriving Building a model for sustainable practice in creativity and mental health. Barnsley: Culture Health and Wellbeing Alliance.

James, W. (1983). The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. London: Penguin Books.

Jetten, J., Alexander Haslam, S., and Haslam, C. (2012). “The case for a social identity analysis of health and well-being,” in The Social Cure: Identity, Health and Well-Being (Psychology Press), 3–20. doi: 10.4324/9780203813195

Kádár, D. Z. (2024). Ritual and Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108624909

Keady, J. D., Campbell, S., Clark, A., Dowlen, R., Elvish, R., Jones, L., et al. (2022). Re-thinking and re-positioning 'being in the moment' within a continuum of moments: introducing a new conceptual framework for dementia studies. Ageing Soc. 42, 681–702. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X20001014

Kenny, C. (1982). The Mythic Artery: The Magic of Music Therapy. Atascadero, CA: Ridgeview Publishing Company.

Kenny, C. (1989). Field of Play: Guide for the Theory and Practice of Music Therapy. Atascadero, CA: Ridgeview Pub Co.

Koch, S. C. (2017). Arts and health: active factors and a theory framework of embodied aesthetics. Arts Psychother. 54, 85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.02.002

Lee, C. J., and Northcott, S. J. (2020). Art for health's sake: community art galleries as spaces for well-being promotion through connectedness. Ann. Leis. Res. 24, 360–378. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2020.1740602

Marmot, M. (2005). Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 365, 1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Bell, R., Bloomer, E., and Goldblatt, P. (2012). WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 380, 1011–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8

Marques, L., Borba, C., and Michael, J. (2021). Grasping the social dimensions of event experiences: introducing the event social interaction scale (ESIS). Event Manage. 25, 9–26. doi: 10.3727/152599520X15894679115448

McCormick, L. (2015). Performing Civility: International Competitions in Classical Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316181478

Páez, D., Rimé, B., Basabe, N., Wlodarczyk, A., and Zumeta, L. (2015). Psychosocial effects of perceived emotional synchrony in collective gatherings. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108, 711–729. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000014

Parkinson, A., Engeli, A., Marshall, T., Burgess, A., Gallagher, P., and Lang, M. (2019). The value of arts and culture in place-shaping. Wavehill social and economic research. Available at: https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/Value%20of%20Arts%20and%20Culture%20in%20Place-Shaping.pdf (accessed August 7, 2024).

Parkinson, C. (2022). A Social Glue Greater Manchester: A Creative Health City Region Summary Report. Manchester: Manchester Institute for Arts Health and Social Change. Available online at: https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/sites/default/files/A%20Social%20Glue_Full%20Report_Digital_Oct22.pdf

Pizarro, J. J., Zumeta, L. N., Bouchat, P., Włodarczyk, A., Rimé, B., Basabe, N., et al. (2022). Emotional processes, collective behavior, and social movements: a meta-analytic review of collective effervescence outcomes during collective gatherings and demonstrations. Front. Psychol. 13:974683. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.974683

Raw, A., Lewis, S., Russell, A., and Macnaughton, J. (2012). A hole in the heart: Confronting the drive for evidence-based impact research in arts and health. Arts Health Int. J. Res. Policy Pract. 4, 97–108. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2011.619991

Raw, A., and Mantecón, A. R. (2013). Evidence of a transnational arts and health practice methodology? A contextual framing for comparative community-based participatory arts practice in the UK and Mexico. Arts Health 5, 216–229. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2013.823555

Raw, A. E. (2013). A model and theory of community-based arts and health practice (thesis), Durham University, Durham.

Rodriguez, A. K., Akram, S., Colverson, A. J., Hack, G., Golden, T. L., and Sonke, J. (2023). Arts engagement as a health behavior: an opportunity to address mental health inequities. Community Health Equity Res. Policy. 44, 315–322. doi: 10.1177/2752535X231175072