- 1Department of Social Science and Economics, University of Applied Sciences Osnabrück, Osnabrück, Germany

- 2Department for Psychology and Psychotherapy, Universitat Witten-Herdecke, Witten, Germany

Introduction: According to modern research on diversity, attitudes toward cultural diversity are a main predictor of performance in heterogeneous teams. Social psychological research, however, focuses on the impact of crises on prejudice and disregards instrumental attitudes. It focuses on two distinct outcomes: the withdrawal of solidarity toward people with a migration background, and pro-diversity beliefs reflecting positive evaluations of cultural heterogeneity, examining how value orientations, emotional responses, and motivational factors may be linked to these attitudes.

Method: Data were collected from N = 130 participants without immigration background during the first lockdown period in spring 2020. Structural path analyses were used to examine associations among key variables.

Results: Social dominance orientation showed statistical associations with intergroup threat and fear, which in turn were linked to reported withdrawal of solidarity. The association between intergroup fear and solidarity withdrawal appeared stronger among individuals reporting lower internal motivation to act without prejudice. In a second model, general solidarity and individualism were associated with pro-diversity beliefs, suggesting that internal motivation and intergroup threat may play mediating roles.

Discussion: The findings point to the relevance of distinguishing between affective and value-based aspects of diversity-related attitudes, particularly under crisis conditions. While emotional responses such as fear and threat were linked to exclusionary tendencies, value-based orientations—such as solidarity and egalitarian motivation—were associated with more inclusive attitudes.

1 Introduction

Group-related attitudes are shaped by a combination of emotional (affective) and cognitive-evaluative (instrumental) processes. During societal crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, these attitudes can shift significantly. Affective responses, including fear and perceived intergroup threat, may result in behaviors like the withdrawal of solidarity—defined as a refusal to support marginalized groups during times of need. In contrast, instrumental attitudes, such as pro-diversity beliefs, reflect cognitive evaluations of diversity's value for group functioning and societal cohesion. This study focuses on these two dependent variables—withdrawal of solidarity and pro-diversity beliefs—as they represent distinct yet interrelated outcomes of intergroup attitudes that have particular relevance in crisis contexts.

Solidarity plays a vital role during crises as a measure of social cohesion and collective support. It is not only a moral or cultural value but also a behavioral expression that indicates who is considered part of the in-group. According to Nohlen (2002), solidarity involves obligations among group members to support each other. Hofmann (2016) emphasizes that solidarity is subject to individual negotiation, especially under conditions of uncertainty. The COVID-19 pandemic presented such conditions, making questions of social affiliation particularly salient. The withdrawal of solidarity—especially toward people with a migration background—can deprive these groups of access to resources and justify discriminatory behavior. In organizational contexts, this translates to lower team performance and reduced wellbeing among employees (Van Dick and Stegmann, 2016).

The pandemic also heightened societal tensions around integration and inclusion. According to the European Commission, both the unintended consequences of the health crisis and the integration of people with a migration background emerged as central social challenges. Previous research has shown that attitudes of majority-group members are pivotal in shaping integration processes (Genkova and Ringeisen, 2017). From a psychological perspective, these attitudes are often affectively driven, rooted in emotional responses such as fear or anxiety.

However, not all group-related attitudes are affective. In contrast to prejudices, instrumental attitudes—such as pro-diversity beliefs—reflect a reasoned, functional evaluation of diversity in society and the workplace. These beliefs have gained attention in diversity research due to their predictive power regarding group performance, inclusion, and openness to difference (Kauff et al., 2019; Van Dick and Stegmann, 2016). They offer a promising perspective for understanding the benefits of diversity and how they are perceived by members of the mainstream population.

To investigate these processes in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, the current study implemented a newly developed scale capturing reactions specific to the pandemic, withdrawal of solidarity toward migrants, general tendency for solidarity, and individualism. Moreover, we tested two separate models that used the newly developed questionnaire to expand research on predictors of affective and instrumental reactions toward the crisis. In the first, withdrawal of solidarity was measured as a dependent variable to represent affectively driven exclusionary behavior. In the second model, pro-diversity beliefs served as the outcome, predicted by broader, value-based tendencies such as general solidarity and individualism. General solidarity captures an individual's overarching orientation toward social cohesion, while individualism reflects a value orientation that prioritizes autonomy and may counteract collectivist responses. This structure allows for an examination of the distinct pathways through which affective and instrumental group-related attitudes develop and manifest.

Rather than merging these processes into a single model, this study adopts an approach that treats them as separate but conceptually linked systems. This design provides a more precise understanding of how fear, values, and motivations independently influence group-related outcomes. By integrating classical research on prejudice with modern perspectives on diversity management, the study sheds light on how people without a migration background in Germany responded to the COVID-19 pandemic.

2 Rationale

2.1 Stereotyping and solidarity

The process of social categorization is the basis for the formation of prejudices and attitudes toward cultural diversity. This process is not problematic at first, it, actually, allows us to react quickly in complex situations by means of simplifying thought patterns, also called categories or stereotypes. Stereotypes relate to certain characteristics as well as affective and behavioral predispositions. Social psychology traces the categorization of people into social groups back to the Social Identity Theory (Aronson et al., 2008; Tajfel, 1981). According to the SIT, a person's social identity is formed by the totality of all groups to which a person subjectively belongs. This, in turn, implies that there are groups to which we do not belong i.e., outgroups.

Each category has predispositions which are called social attitudes. Different characteristics can become salient at different points in time. A characteristic which is currently salient thus differs from the remaining characteristics. Next to the preference for own groups, categorization is subject to some biases, which influence how we perceive members of groups. Individuals perceive outgroups as more homogenous, while they experience in-group members as more heterogenous. People perceive a relation between group membership and various characteristics of a stereotyped person. This judgment is based, however, on little information and no contact to the stereotyped person. This bias is known as illusory correlation (Degner et al., 2009). When an individual is consciously confronted with a stereotype, he can either choose to disconfirm the stereotype or to apply it. However, individuals are often not aware that they use stereotypes, especially in complex or stressful situations (Degner et al., 2009).

2.1.1 Withdrawal of solidarity as an expression of prejudice

Prejudice is typically conceptualized as a negative predisposition toward members of an outgroup. It frequently manifests in behaviors that create or reinforce social exclusion, particularly during times of societal stress. One such behavior is the withdrawal of solidarity—wherein individuals withhold social support from marginalized groups. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, this behavior has served as a clear indicator of prejudicial attitudes. Social psychological research suggests that prejudice often stems from simplified categorizations and stereotypes, which are culturally conditioned and perceived as normative (Aronson et al., 2008; Weiss, 2003). Importantly, such prejudices are not limited to fringe ideological groups but can be found within mainstream society (Heitmeyer, 2011; Hofmann, 2012). Hofmann (2016) emphasizes that the denial of solidarity reflects affective processes linked to perceived threat and fear, particularly in moments of crisis when individuals are more attuned to group boundaries. Drawing on social identity theory, it becomes evident that during such crises, individuals are prone to in-group favoritism, leading to reduced empathy for outgroups such as immigrants. This withdrawal of solidarity reflects not only interpersonal bias but also moral exclusion—where marginalized groups are placed outside the boundaries of moral concern (Opotow, 1990).

2.1.2 Social dominance theory as an explanation of prejudice in times of crisis

Social Dominance Theory (SDT) provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how intergroup prejudice and inequality are maintained and expressed, particularly during times of societal stress and uncertainty. At its core, SDT posits that societies are organized as group-based hierarchies, with dominant and subordinate groups arranged along dimensions such as age, gender, and arbitrary-set systems (e.g., ethnicity, class, religion). These hierarchies are sustained through a variety of mechanisms, including institutional practices, cultural ideologies, and individual-level psychological orientations (Paranti and Hudiyana, 2022; Pratto et al., 1994; Sidanius and Pratto, 1999).

A central construct in SDT is Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), which reflects an individual's general preference for inequality among social groups. Those high in SDO favor hierarchy-enhancing ideologies (e.g., meritocracy, nationalism, racism) and tend to support policies that preserve or intensify group-based dominance. Conversely, individuals low in SDO are more likely to endorse hierarchy-attenuating values such as egalitarianism and social justice (Pratto et al., 1994; Sidanius and Pratto, 1999).

SDT emphasizes that legitimizing myths—culturally accepted beliefs that justify social inequalities—play a crucial role in reinforcing dominance. These myths operate at both systemic and psychological levels and are more readily accepted under conditions of threat or instability. In times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the appeal of hierarchy-enhancing ideologies may increase, as people seek certainty, control, and scapegoats for their anxieties. The withdrawal of solidarity from marginalized groups during such crises is not merely a reflection of personal prejudice but can be understood as an expression of an overarching social dominance framework.

Recent research supports this interpretation. For example, Uenal (2016) found that SDO significantly predicts exclusionary attitudes, particularly under conditions of perceived threat. These findings echo Pratto et al.'s (1994) earlier work, which showed that individuals high in SDO are more likely to endorse policies and attitudes linked to militarism, punitiveness, and resistance to minority rights. Importantly, SDO is also associated with reduced empathy, tolerance, and altruism—traits necessary for solidarity and inclusion.

2.1.3 Intergroup fear and threat as mediators of the SDO–solidarity relationship

While SDO provides a foundational predisposition toward hierarchy and exclusion, the mechanisms through which it translates into behaviors like the withdrawal of solidarity are complex. Two key mediators in this process are intergroup fear and intergroup threat. Integrated Threat Theory (Stephan and Stephan, 2000) further elaborates that prejudice arises when an outgroup is perceived as a threat—either symbolically, by endangering cultural values, or realistically, by competing for resources. Intergroup fear, defined as a generalized anxiety or discomfort with outgroup interaction, and symbolic or realistic threats function as proximal causes that mediate the effect of ideological orientations like SDO on exclusionary behavior.

Empirical evidence supports this mediational model. Uenal (2016) finds that SDO predicts various forms of intergroup threat and fear, which in turn relate to attitudes toward marginalized populations. Although findings are mixed regarding the specific types of fear most relevant, the role of these mediators is well-established. They help explain how a relatively stable personality trait such as SDO can result in context-sensitive expressions of prejudice, such as the withdrawal of solidarity during a public health crisis.

2.1.4 Motivation for prejudice-free behavior as a moderator of threat-induced prejudice

The expression of prejudice in contemporary societies is often shaped not only by internal beliefs but also by powerful social norms that discourage overtly biased behavior. As a result, conventional assessments of prejudice face significant challenges due to social desirability bias. To address this issue, Plant and Devine (1998) introduced the concept of motivation for unprejudiced behavior, distinguishing between internal motivation, which stems from personal egalitarian values, and external motivation, which arises from the desire to conform to social expectations (Martiny and Froehlich, 2020). This differentiation is critical, as the type of motivation may shape how individuals manage intergroup biases—particularly in emotionally charged situations like crises.

Banse and Gawronski (2003) argued that responses on explicit attitude measures are not mere artifacts of self-presentation, but instead reflect active cognitive processing of social information. From this perspective, explicitly stated egalitarian values can represent meaningful motivational states rather than being dismissed as socially desirable responses. Furthermore, they highlight that expressions of prejudice are not simply products of latent attitudes, but are also governed by behavioral control, which is influenced by the social and normative context. In environments where racist norms are prominent, even individuals with low prejudice may display discriminatory behavior due to external pressures. Conversely, in normatively egalitarian contexts, high-prejudice individuals may suppress biased responses.

The interplay between fear, perceived threat, and prejudice is particularly salient in times of societal crisis. As Hofmann (2016) and Heitmeyer (2011) suggest, the denial of solidarity—such as withdrawing support from marginalized groups during the COVID-19 pandemic—is closely linked to affective processes of perceived threat. In such moments, group boundaries become more salient, increasing the likelihood of moral exclusion (Opotow, 1990) and ingroup favoritism (Aronson et al., 2008). Social Dominance Theory (Pratto et al., 1994) further supports this view by arguing that threats to societal stability activate hierarchy-preserving ideologies, particularly among individuals with high social dominance orientation (SDO). Uenal (2016) demonstrated that, under threat, SDO strongly predicts exclusionary attitudes.

However, this dynamic does not affect all individuals equally. The motivation for unprejudiced behavior may act as a buffer against the prejudicial effects of fear and threat. Fehr et al. (2012) showed that both internal motivation and egalitarian values moderate the controlled processing of stereotypical associations. In threatening contexts where stereotypes are easily activated, those who are internally motivated to be unprejudiced may exert greater effort to inhibit biased reactions and uphold inclusive norms. This aligns with Banse and Gawronski's (2003) emphasis on behavioral regulation in accordance with social or personal standards.

Given these findings, it is plausible to conceptualize motivation for unprejudiced behavior not merely as an outcome or mediator of prejudice, but as a moderator in the relationship between fear/threat and the withdrawal of solidarity. In other words, individuals with high internal motivation may resist the normative pull toward exclusion, even under stress, whereas those with low motivation—especially those driven only by external factors—may be more susceptible to acting on prejudices when societal cohesion is strained.

2.2 Attitudes toward cultural diversity

In increasingly diverse societies, the way individuals evaluate and respond to cultural heterogeneity plays a crucial role in fostering social cohesion and inclusion. While overt prejudices and intergroup attitudes have been extensively researched, less is known about the interplay of underlying value orientations and motivational processes that lead to positive intergroup outcomes such as pro-diversity beliefs. This paper proposes a model in which solidarity, as a general value orientation, indirectly promotes pro-diversity beliefs via intergroup threat and motivation to act without prejudice, and in which the cultural value of individualism moderates these relationships.

2.2.1 Pro-diversity beliefs: instrumental evaluations of diversity

In contemporary social psychology and intergroup research, pro-diversity beliefs have emerged as a key construct for understanding how individuals cognitively and evaluatively engage with societal heterogeneity. Originally introduced by van Knippenberg and Haslam (2003), pro-diversity beliefs describe the conviction that diversity—especially cultural or ethnic—enhances group functioning and contributes positively to collective goals. These beliefs reflect an instrumental, rather than affective, evaluation of diversity, distinguishing them from traditional measures of intergroup attitudes or prejudice.

Kauff et al. (2019) define pro-diversity beliefs as the individual conviction that diversity is beneficial for the functioning of a society. Importantly, these beliefs operate across levels: on the group level, they relate to improved team performance, decision quality, and creativity in diverse teams; on the societal level, they signify the belief that multiculturalism and inclusion benefit the broader social system by improving problem-solving, social cohesion, and innovation.

This distinction between affective attitudes (e.g., prejudice, warmth, threat) and instrumental evaluations (e.g., utility, performance, functionality) is conceptually aligned with dual-process models of social cognition (e.g., Gawronski and Bodenhausen, 2006), in which emotional and cognitive components of attitudes can diverge. While affective attitudes have been the primary focus of much of the prejudice literature, recent research has emphasized the need to examine beliefs about diversity as a normative and epistemic stance, especially in pluralistic societies (Moreu et al., 2021).

Moreover, pro-diversity beliefs have gained relevance in applied domains such as organizational psychology, educational settings, and public policy. In workplace research, they are associated with stronger group identification, more cooperative norms, and more positive intergroup dynamics in diverse teams (Van Dick et al., 2008). In education, students who endorse pro-diversity beliefs show higher openness to multicultural curricula and greater acceptance of immigrant peers (Kauff et al., 2020). These findings underscore the role of pro-diversity beliefs as a socially adaptive, future-oriented attitude that supports pluralism without ignoring group boundaries.

Importantly, pro-diversity beliefs can be both dispositional and contextually malleable. While some research treats them as stable individual differences, other studies show that they can be influenced by leadership cues, diversity training, or framing effects (van Knippenberg and Haslam, 2003). This dual character renders them especially suitable for interventions aimed at reducing polarization and promoting inclusion in diverse societies.

Pro-diversity beliefs are also theoretically positioned as the positive counterpart to constructs such as intergroup threat or competitive zero-sum beliefs. While both constructs refer to the instrumental implications of diversity, they differ fundamentally in valence and psychological function. Intergroup threat emphasizes perceived competition, loss, and conflict, often reinforcing ingroup defensiveness and exclusion (Stephan and Stephan, 2000). In contrast, pro-diversity beliefs highlight the potential contributions of outgroups and encourage inclusive identification with superordinate categories (Van Dick and Stegmann, 2016).

Given this conceptual distinction, and the growing empirical evidence for their role in shaping inclusive intergroup behavior, pro-diversity beliefs serve as a meaningful outcome variable in this study. By focusing on this construct, we align with a normative shift in diversity research: moving beyond the reduction of prejudice toward the promotion of positive, future-oriented, and cooperative intergroup attitudes.

2.2.2 Solidarity as a predictor of pro-diversity beliefs

Solidarity is a core moral and social value that denotes a commitment to shared welfare, mutual support, and collective responsibility. In psychological terms, it is increasingly conceptualized as a value orientation—a relatively stable predisposition to prioritize the needs of others, particularly those facing disadvantage or exclusion (Prainsack and Buyx, 2017). This orientation often manifests in prosocial behavior, inclusive attitudes, and support for policies aimed at equity and justice (van Zomeren et al., 2012).

The general tendency toward solidarity, conceptualized as a personal or cultural inclination to value the welfare of others and act cooperatively, has been discussed as a foundational value that shapes social attitudes (Earley and Gibson, 1998; Lynch and Kalaitzake, 2020). From a social identity and intergroup perspective, solidarity is especially relevant because it expands the psychological boundaries of concern beyond one's immediate ingroup. Individuals high in solidarity tend to adopt a more inclusive, superordinate identity—such as a sense of common humanity—which in turn supports more positive attitudes toward cultural outgroups (Reicher and Haslam, 2006). In this way, solidarity reflects a moral and cognitive readiness to embrace intergroup diversity as a social reality rather than a threat.

As such, solidarity can be expected to promote pro-diversity beliefs, the instrumental belief that diversity enhances group and societal functioning. Individuals who are oriented toward solidarity are likely to view the inclusion of cultural outgroup members not merely as tolerable, but as normatively desirable and functionally advantageous. In contrast to more self-focused value orientations (e.g., power, security, or tradition), solidarity aligns with a worldview in which interdependence and mutual contribution are emphasized, thereby predisposing individuals to perceive cultural diversity as an asset rather than a liability.

This predictive relationship is also supported by empirical work linking solidarity to inclusive policy attitudes, support for refugee rights, and acceptance of multiculturalism (Prainsack and Buyx, 2017). Furthermore, the framing of diversity in instrumental terms—as a shared resource for solving collective problems—resonates with the moral underpinnings of solidarity, which prioritize the common good over individual gain.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a real-world context in which the role of solidarity became especially visible. Appeals to solidarity were central in public discourse, encouraging citizens to engage in behaviors (e.g., mask-wearing, vaccination, mutual aid) that protected not only themselves but others—particularly vulnerable groups. Studies conducted during this time revealed that individuals high in solidarity were more likely to comply with health measures and support equitable distribution of healthcare resources (Pfattheicher et al., 2020). These behaviors parallel the kind of collective responsibility that underlies pro-diversity beliefs.

In collectivist cultures, solidarity is typically directed at broader in-groups, while in individualist societies, it is often restricted to close social ties (Mau, 2015). Individuals high in solidarity may be more predisposed to view diversity as a collective strength, thereby fostering pro-diversity beliefs. However, this relationship is likely to be mediated by more proximal psychological mechanisms, such as perceived intergroup threat and the internal motivation to act without prejudice.

2.2.3 The mediating role of intergroup threat and prejudice-reduction motivation

In previous sections, we established that intergroup threat and fear mediate the relationship between ideological orientations such as SDO and expressions of exclusion. However, these constructs also help explain the reverse pathway: how solidarity enables individuals to endorse inclusive attitudes like pro-diversity beliefs. If fear and threat erode solidarity, the absence of threat may facilitate its downstream consequences.

According to Integrated Threat Theory (Stephan and Stephan, 2000), individuals high in solidarity—who typically identify with broader collectives—are less likely to perceive cultural outgroups as realistic (e.g., economic) or symbolic (e.g., cultural values) threats. Solidarity fosters a sense of shared fate and moral inclusion, which lowers intergroup anxiety and reduces the salience of competition. Thus, reduced threat functions as a key mechanism by which solidarity promotes positive evaluations of diversity.

In parallel, solidarity is closely aligned with internal motivation to act without prejudice (Plant and Devine, 1998). Unlike external motivation, which is norm-driven, internal motivation stems from personal values and is more stable across contexts. Individuals high in internal motivation may thus be more likely to regulate biased responses and maintain inclusive attitudes—even under stress. Solidarity, as a deeply held value, can reinforce such motivations and increase their behavioral expression.

Therefore, we propose that solidarity is indirectly related to pro-diversity beliefs:

• By being negatively related to perceived threat, and

• By being positively related to motivation to act without prejudice, which enables cognitive reframing of diversity as a collective advantage.

This framework aligns with the affective and motivational processes identified in prior work on prejudice under threat (Fehr et al., 2012).

2.2.4 The moderating role of individualism

While solidarity can promote openness toward diversity, the strength of this influence may depend on individuals' cultural orientation toward individualism—defined as a value that emphasizes autonomy, self-interest, and independence over communal obligation (Hofstede, 2001). In highly individualistic cultures, solidarity is often restricted to close circles (e.g., family or friends) and may not extend as easily to culturally distant outgroups (Lynch and Kalaitzake, 2020).

We therefore expect that individualism moderates the effects of solidarity on both threat and motivation. When individualism is low, solidarity more effectively reduces intergroup threat and enhances egalitarian motivation. When individualism is high, solidarity's effect may be limited by self-referential or exclusionary tendencies.

3 Method

3.1 Hypothesis

The present study examines the psychological mechanisms that underlie two distinct but related intergroup outcomes during the COVID-19 crisis: the withdrawal of solidarity toward people with a migration background and the endorsement of pro-diversity beliefs. Building on the theoretical frameworks of Social Dominance Theory and Integrated Threat Theory, we propose that affective responses such as intergroup fear and perceived threat are key mediators linking Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) to exclusionary behaviors. At the same time, value-based orientations, such as a general tendency toward solidarity, are hypothesized to promote more inclusive, instrumentally grounded attitudes toward diversity, provided that individuals are not constrained by perceived threat or conflicting motivational orientations.

To capture this duality, we implemented a two-pathway design. In the first model, we investigate the extent to which SDO predicts the withdrawal of solidarity through affective mechanisms. We further test whether internal motivation for unprejudiced behavior buffers the relationship between threat and exclusion, acting as a moderator. In the second model, we explore how solidarity contributes to positive evaluations of diversity by reducing perceived threat and strengthening internal motivation. In line with value-based models of social behavior, we also examine whether the cultural orientation of individualism attenuates these effects by limiting the generalizability of solidarity-based concerns beyond one's immediate ingroup.

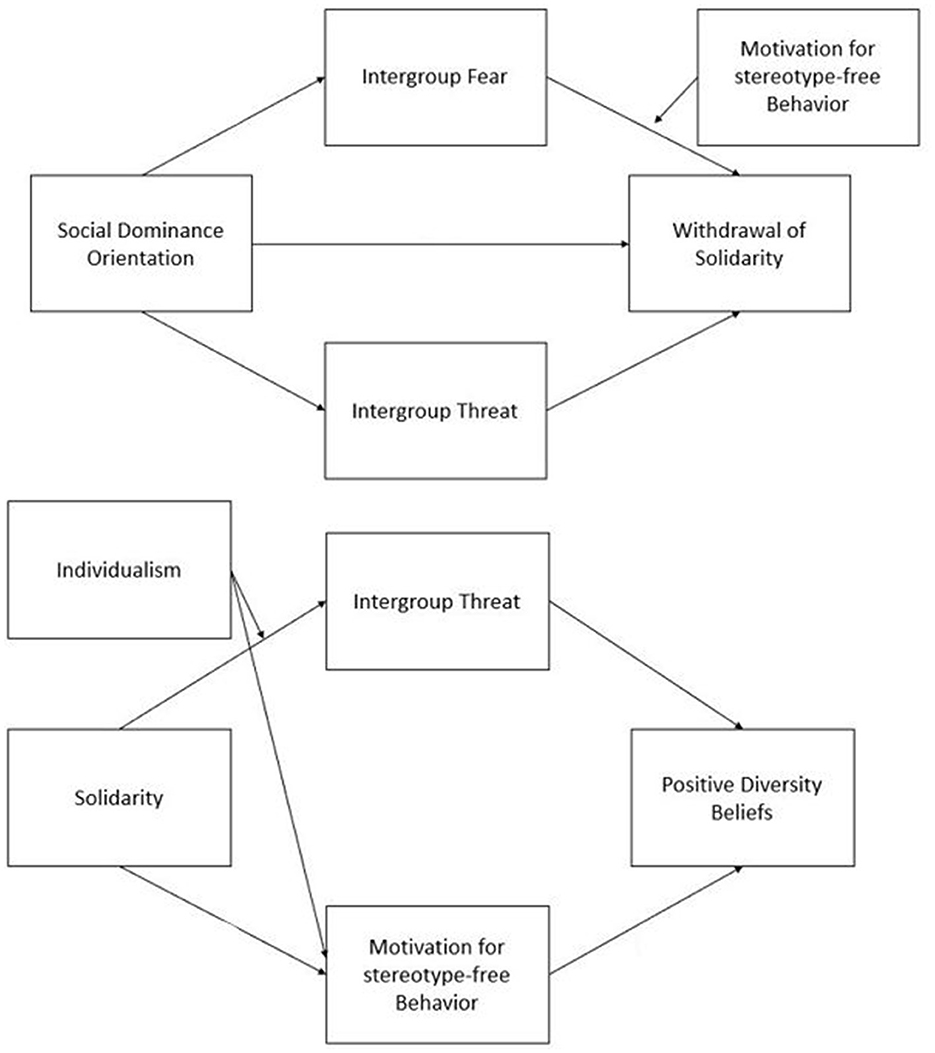

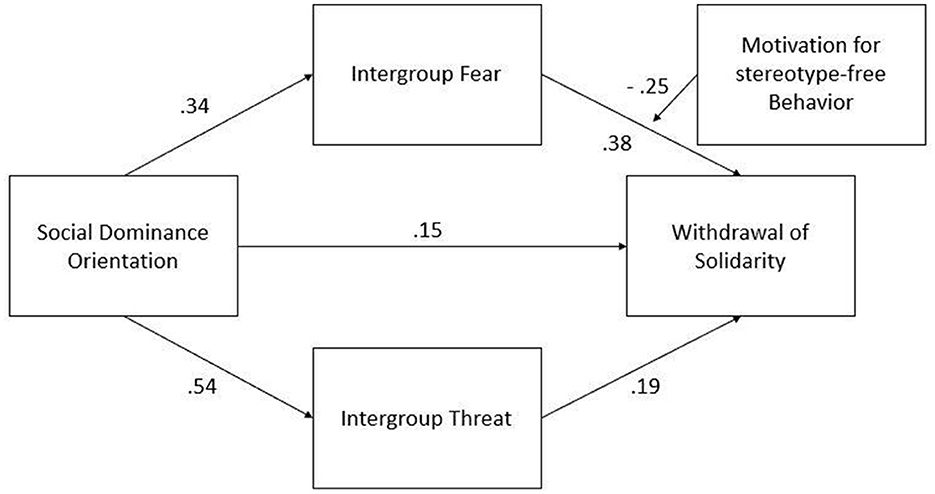

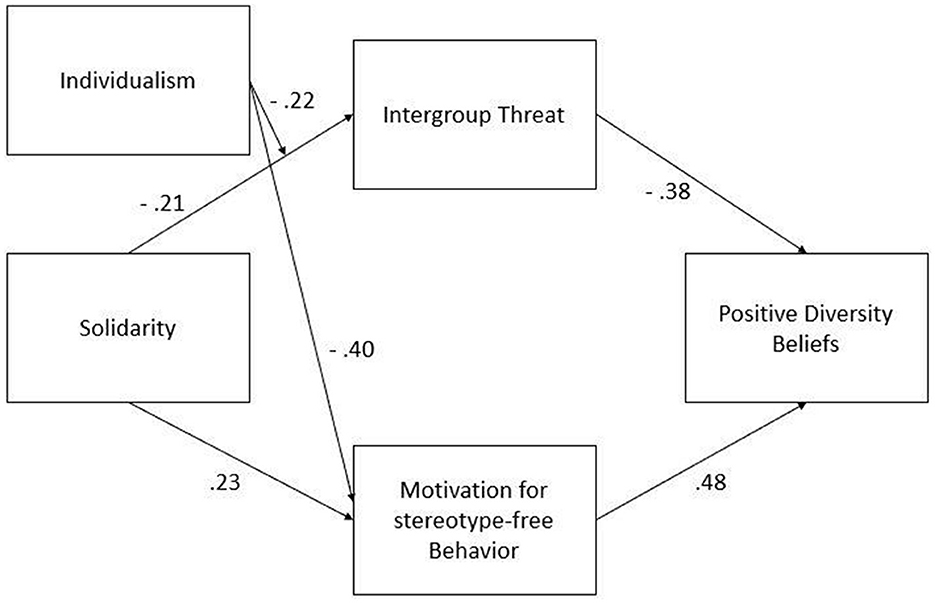

By disentangling the emotional and cognitive pathways underlying intergroup attitudes during a societal crisis, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how ideological predispositions, values, and motivational processes jointly shape inclusive or exclusionary responses. Specifically, we propose the following hypotheses. Figure 1 summarizes them as path-models.

H1: Intergroup fear and intergroup threat mediate the effect of SDO on withdrawal of solidarity toward people with a migration background.

H1A: Motivation for stereotype-free behavior moderates the effect of intergroup fear and intergroup threat on the withdrawal of solidarity toward people with a migration background.

H2: Intergroup threat and motivation to stereotype-free behavior moderates the effect of general solidarity on positive diversity attitudes.

H2A: Individualism moderates the effect of solidarity on intergroup threat and motivation to stereotype-free behavior.

To test the hypotheses, we developed a questionnaire on group-related attitudes in the corona crisis. With reference to Hofmann (2016), the questionnaire covers withdrawal of solidarity toward people with a migration background and fear of corona disease, general solidarity in the corona crisis and individualism as value-related dimensions.

3.2 Study design

The study used a quantitative cross-sectional design. In the period of 23.03.2020 – 15.04.2020 an online study was conducted using the platform LimeSurvey. The acquisition of the test people took place mainly via local Facebook groups related to different cities in Germany. The participants were informed in accordance with the data protection guidelines that this was an anonymous study. Accordingly, personal data is used for purely scientific purposes and cannot be traced back to individual people. Furthermore, participants were asked to answer honestly and spontaneously. The constraints of the lockdown limited both the size of the sample, but the exceptional timing of the data collection provides valuable ecological validity and allows insight into how individuals without a migration background responded to diversity-related issues during an unfolding crisis.

3.3 Measurement instruments

The questionnaire consisted of four parts. A demographic section, followed by the questionnaire about attitudes to cultural diversity in the crisis. In addition, the Pro-Diversity Beliefs Scale in the German version by Kauff et al. (2019) was used, as well as the scale Motivation for stereotype-free behavior by Banse and Gawronski (2003).

The Pro-Diversity Beliefs Scale is a very new, valid instrument for recording intergroup attitudes. It measures, via self-declarations and Likert-scales, Positive Diversity Attitudes (1–5; five items; α = 0.95), attitude toward strangers (in percent, one item), Intergroup Threat (1–7; two items; α = 0.80), Authoritarian Aggression (1–5; nine items; α = 0.87), Social Dominance orientation (1–7; five items; α = 0.75), Intergroup anxiety (1–4; four items; α = 0.84), positive and negative group contact (1–7; three items; α = 0.70), multiculturalism (1–7; five items; α = 0.76), and non-instrumentalized appreciation of diversity (1–5; four items; α = 0.82).

The scale of motivation for stereotype-free behavior (Banse and Gawronski, 2003) records in 16 items the control of behavior (eight items, α = 0.834), the admission of own prejudices (four items, α = 0.846) and the unprejudiced self-presentation (three items, α = 0.702) on a Likert scale of 1 (I do not agree at all) – 5 (I fully agree).

3.4 Sample

Of the 310 participants, 130 fully completed the survey. A larger proportion of the respondents were female (187), a quarter (67) male, 4 stated themselves as diverse and 73 gave no indication. Of the participants, 53% had a steady partner and 28% had children. In the sample, doctoral candidates were overrepresented with 5.7%, but none of the participants did not have a school-leaving certificate or a secondary modern school leaving certificate. Eight percentages had the intermediate secondary school leaving certificate, 5% a vocational baccalaureate, 12.4% A-levels, 11 % a completed apprenticeship, and 34% a completed university degree. Participants came from all German federal states, with Lower-Saxony (34%) and North-Rhine-Westphalia (31%) being overrepresented, Bavaria (9%), Saxony (7%), Berlin (4%), and Hamburg (4%) being underrepresented and the 10 other federal states being represented by only one or two participants, respectively. Since this study examines the attitudes of members of the mainstream group within the German population, people with a migration background were excluded from testing the hypotheses to avoid distortions.

While the sample is not representative of the German population, it was collected during the early phase of the first COVID-19 lockdown—a period of high societal uncertainty and rapidly changing social dynamics. This unique context offers valuable insight into how group-related attitudes manifest under acute crisis conditions. As such, the study should be viewed as an exploratory investigation of theoretical mechanisms rather than a basis for population-level inferences. Future research should aim to replicate these findings in larger, more representative samples.

4 Results

In the following, the results of the questionnaire verification by means of exploratory factor analysis and the hypothesis test by means of multiple regression analysis are presented.

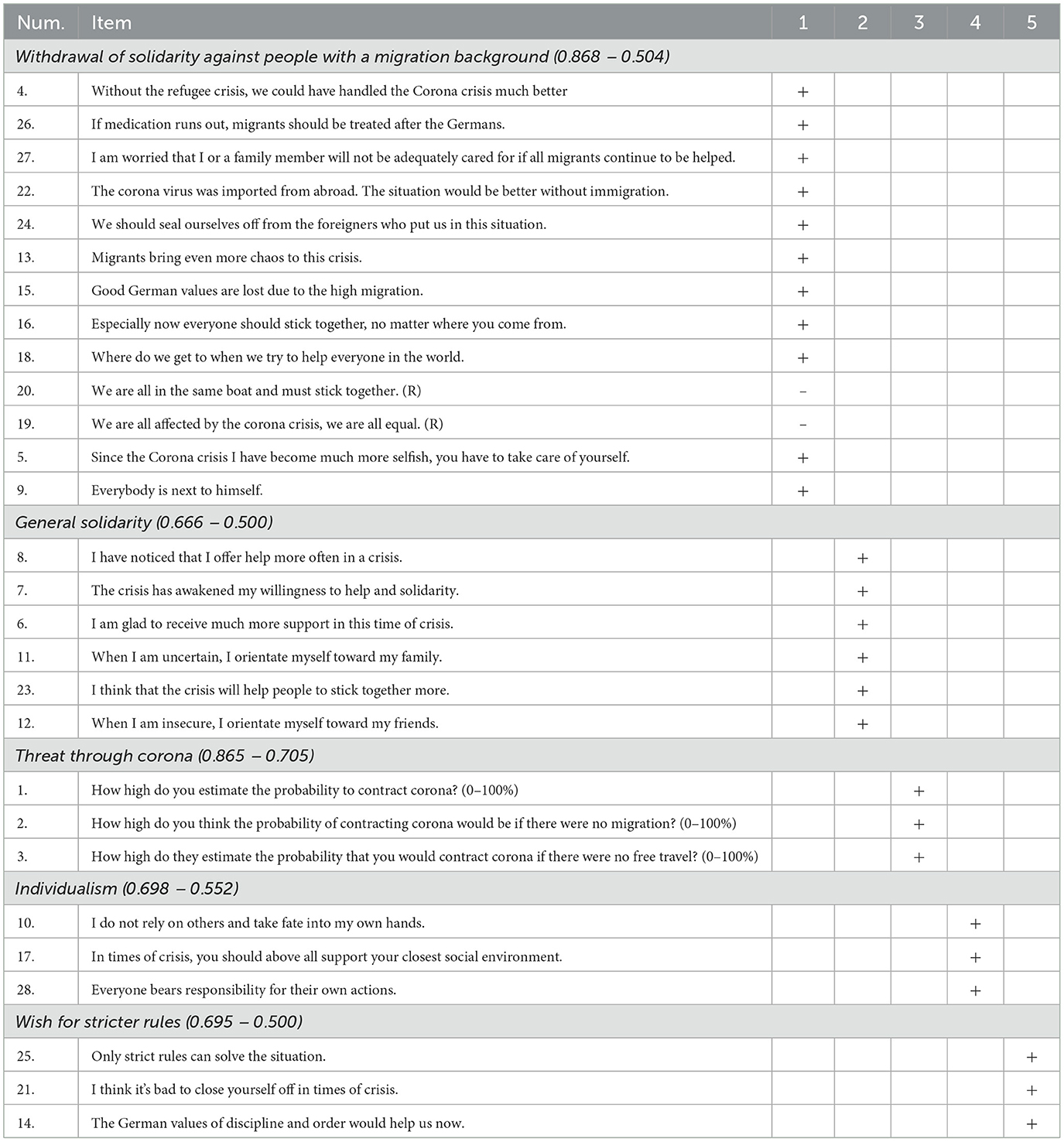

The original questionnaire for measuring attitudes toward cultural diversity in the crisis had 32 items. A factor analysis with Varimax Rotation did not confirm the intended four-factor structure. The model explained only 24% of the variance. An explorative procedure resulted in nine factors that fulfilled the Kaiser criterion, four of which had eigenvalues of more than one. A structure with five factors resulted in an explained variance of 57%. Six items were excluded due to excessive cross-charge. For the perception of cultural diversity in the crisis, the structure in Table 1 was confirmed. Items 25 and 14 were originally assigned to negative attitudes, item 21 to positive attitudes. However, it turned out that these related to an independent factor, which is interpreted here as a desire for strict regulations.

Table 1. Factor structure for the questionnaire on the perception of cultural diversity in the corona crisis with the respective factor loads (translated by the author, German version available on request).

4.1 Hypothesis

We tested the hypotheses using multiple regression analysis with the PROCESS Macros for SPSS. Homoskedasticity as well as the other statistical requirements were met for all analyses performed. Indirect and total effects are not displayed by SPSS in moderated mediation models, since they depend on the characteristics of the moderators. For the interaction effect of the moderator variables on a context, index values were calculated for better illustration. The significant conditional direct effects are presented in tabular form.

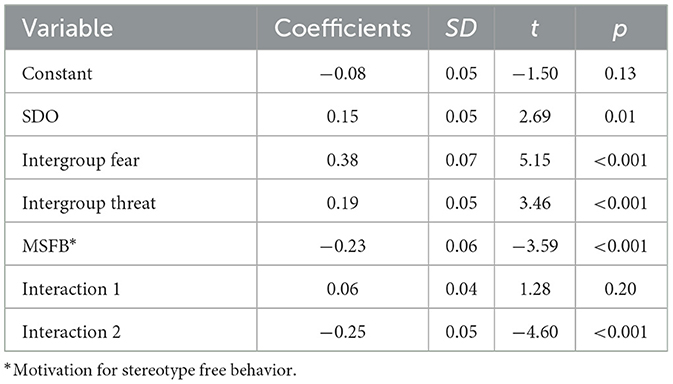

H1: Intergroup fear and intergroup threat mediate the effect of SDO on withdrawal of solidarity toward people with a migration background.

H1A: Motivation for stereotype-free behavior moderates the effect of intergroup fear and intergroup threat on the withdrawal of solidarity toward people with a migration background.

To test hypothesis 1 and 1A, a mediation analysis was calculated with PROCESS (model 14, bootstrap samples 10,000). Figure 2 summarizes the results in a path model. All coefficients are standardized. Only significant paths are displayed. The mediation model is significant for all endogenous variables. Table 2 shows the results for the dependent variable withdrawal of solidarity. The model shows a very good fit with R2 = 0.74 [F(6,123) = 58.88, p < 0.001]. Hypothesis 1 is confirmed. There is no significant interaction effect of intergroup threat and motivation for stereotype-free behavior. Hypothesis 1A can therefore only be considered partially confirmed.

Figure 2. Moderated mediation model for the dependent variable withdrawal of solidarity against people with migration background. All coefficients are standardized.

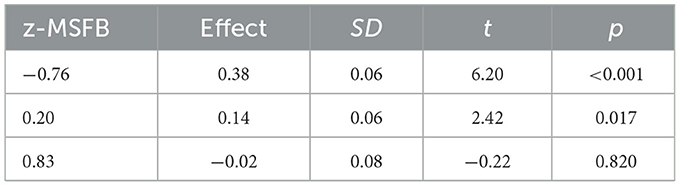

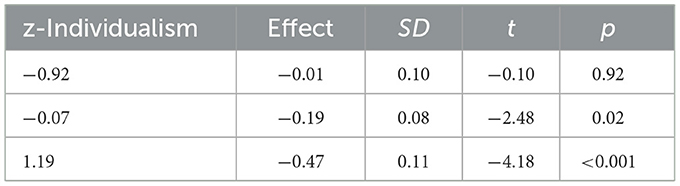

H2: Intergroup threat and motivation to stereotype-free behavior moderates the effect of general solidarity on positive diversity attitudes.

H2A: Individualism moderates the effect of solidarity on intergroup threat and motivation to stereotype-free behavior.

Hypothesis 2 and 2A were also tested with PROCESS (Model 7, Bootstrap samples: 10,000). The statistic conditions for the multiple regression analysis were fulfilled. The model is significant for all endogenous variables. Figure 3 illustrates the verified relationships. For the dependent variable a good model fit of R2 = 0.51 [F(3,126) = 44.08, p < 0.001] is obtained. Solidarity no longer has a direct effect on positive diversity attitudes in the model tested. Hypothesis 2 was nevertheless confirmed. Individualism moderates the effect of solidarity on intergroup threat. Individualism has a direct effect on motivation for stereotype-free behavior but no interaction effect with solidarity. Hypothesis 2A is therefore only partially confirmed. Tables 3–5 show additional analyses.

Figure 3. Moderated mediation model for the dependent variable positive diversity beliefs. All coefficients are standardized.

5 Discussion

5.1 Questionnaire construction

The study at hand was only partially successful in developing a questionnaire on group-related attitudes in the corona crisis. Individualism, group conflict, solidarity, and the perceived subjective personal threat emerged as independent factors. It was shown that the desire for strict regulations was also an independent factor in the corona crisis, which correlated only slightly with the items of the other factors. Since this study was less concerned with the fear of corona than with group-related fears in the context of corona, the analysis could be continued as planned. The desire for strict regulations is one dimension of the authoritarianism study and the items of the fourth factor can be related in terms of content to the concept of Social Darwinism in reference to Decker et al. (2018). Pettigrew (2016) distinguishes intergroup fear from authoritarianism. He points out that these constructs are based on different cognitive processes. Although they influence each other in cases of doubt, they are distinct from each other. Due to cross-loadings, we reduced the number of items for individualism to under four. Further studies should probably try to start with a bigger pool of items, derived from existing instruments on the constructs. A further step would be to reduce the items statistically in order to increase construct validity.

5.2 Discussion and specific relations

The results of the hypothesis tests provide support for the proposed models of intergroup attitudes during the COVID-19 crisis. Both primary hypotheses—H1, concerning the withdrawal of solidarity, and H2, addressing pro-diversity beliefs—were supported. This confirms the relevance of affective and cognitive-evaluative processes as distinct but complementary mechanisms shaping intergroup behavior. Furthermore, moderation analyses yielded partial support for H1A and H2A, indicating that while value-based and motivational factors moderate some of the proposed relationships, their influence may vary depending on the specific mediating process.

The first model replicated key findings from Uenal (2016), who identified intergroup fear and threat as important mediators of SDO's influence on exclusionary attitudes. However, the current study extends Uenal's work by adapting the model to a pandemic context, excluding fear of terrorism—which was central in Uenal's research but less relevant under COVID-19 conditions—and by focusing on withdrawal of solidarity toward people with a migration background, rather than toward a specific outgroup. This broadens the construct of exclusionary behavior and situates it more clearly within a public health and societal solidarity framework.

Importantly, our results revealed that intergroup fear only predicted withdrawal of solidarity among individuals low in internal motivation to act without prejudice, whereas intergroup threat exerted a direct effect regardless of motivational orientation. This suggests that affective reactions like fear are more susceptible to normative or value-based regulation, consistent with the controlled processing model proposed by Banse and Gawronski (2003) and supported by Fehr et al. (2012). In contrast, the effect of intergroup threat appears more cognitively entrenched or normatively acceptable, and therefore less easily moderated by internal egalitarian motivation.

This observation contributes to the ongoing debate about whether intergroup threat is best understood as an affective or instrumental construct. While some literature, such as Hofmann (2016), emphasizes its emotional underpinnings, our findings suggest a more functionalist reading is appropriate—particularly when considering its limited moderation by internal motivation. This interpretation is consistent with Pettigrew's (2016) suggestion that intergroup threat may reflect instrumental concerns linked to relative deprivation, rather than purely affective anxiety. However, due to the limited operationalization of the construct in this study, further research is needed to determine whether intergroup threat comprises distinguishable affective and instrumental subcomponents, as proposed by Uenal (2016) in the context of attitudes toward Muslims.

The second model focused on solidarity and pro-diversity beliefs, with intergroup threat and prejudice-reduction motivation as mediators. The results confirmed that solidarity fosters pro-diversity beliefs through lower intergroup threat and higher motivation to act without prejudice. These findings underscore solidarity's role as a value orientation that supports inclusive, functionally grounded views of diversity—an effect consistent with theoretical models linking values to egalitarian attitudes (Duckitt, 2001; Reicher and Haslam, 2006).

However, this pathway is not unconditionally robust. Individualism—a cultural value emphasizing autonomy and self-interest—moderated the effect of solidarity on intergroup threat. Specifically, under conditions of high individualism, solidarity predicted stronger intergroup threat perceptions. This finding supports the argument advanced by Lynch and Kalaitzake (2020) that solidarity in individualist contexts may become inwardly focused, restricted to close social circles, and may inadvertently heighten competitive perceptions of outgroups. In such cases, even a nominal orientation toward solidarity can co-exist with exclusionary attitudes, if the value system guiding that solidarity is more exclusive or self-protective in nature.

Interestingly, individualism did not moderate the effect of solidarity on motivation to act without prejudice; instead, each value exerted its effect independently. This implies that while values can interact in shaping threat perceptions, their influence on deeper motivational processes may follow more distinct pathways. As such, solidarity appears to activate internal egalitarian motivation regardless of the individual's expression of individualism, highlighting the robustness of this moral value in contributing to positive attitudes toward cultural diversity.

Given the central goal of this study—to understand value-driven responses to diversity in times of crisis, the findings offer important insights into how affective, cognitive, and motivational factors interact in culturally specific ways. Future cross-cultural research should test whether similar dynamics hold in other cultural settings and examine which values most reliably predict the motivation to act without prejudice. Such studies could further disentangle the roles of individualism, collectivism, moral identity, and civic responsibility in fostering inclusive intergroup behavior.

5.3 General discussion

This study examined two theoretically grounded but distinct intergroup outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: the withdrawal of solidarity toward people with a migration background, and positive, instrumental attitudes toward diversity. These outcomes were selected to reflect different aspects of how individuals evaluate diversity during a societal crisis—one associated with affective reactions and defensive social boundaries, the other with reasoned, value-related assessments of cultural heterogeneity.

Findings indicated that intergroup fear and perceived threat were statistically associated with the withdrawal of solidarity, supporting existing theoretical work on affect-based exclusion and defensive reactions to outgroups in uncertain or threatening contexts. However, the relationship between intergroup fear and solidarity withdrawal was moderated by internal motivation to act without prejudice. Specifically, a significant association between intergroup fear and solidarity withdrawal was only observed among individuals low in internal motivation, suggesting that value-driven motivations may relate to the regulation of affective responses. This aligns with prior research that highlights the role of internal motivation in the effortful control of biased responses (Banse and Gawronski, 2003; Fehr et al., 2012). In contrast, intergroup threat showed a statistical effect on solidarity withdrawal that was not moderated by internal motivation, which may indicate that perceptions of threat are associated with more stable or socially sanctioned attitudes that are less subject to regulation.

The second part of the study examined positive attitudes toward diversity, conceptualized as instrumental evaluations of the benefits of heterogeneity for groups and societies. Results showed that solidarity and internal motivation to act without prejudice were statistically associated with stronger pro-diversity beliefs, suggesting that these value-related variables correspond to more positive diversity evaluations. This is consistent with the notion that moral values and prosocial dispositions are relevant for attitudes that emphasize cooperation and inclusion.

However, the association between solidarity and intergroup threat was moderated by individualism. Specifically, among individuals high in individualism, higher solidarity was statistically related to greater intergroup threat. This pattern may reflect a tendency for solidarity in individualistic value systems to be directed more narrowly toward close social networks, with culturally distant outgroups more likely to be viewed as potential competitors (Lynch and Kalaitzake, 2020; Mau, 2015). Such a dynamic suggests that solidarity does not operate uniformly across cultural value contexts and may correspond to ambivalent social attitudes depending on how broadly group boundaries are defined.

At the same time, individualism did not moderate the relationship between solidarity and the motivation to act without prejudice. Each value exerted its influence independently, indicating that the internalization of egalitarian norms may be a more robust predictor of inclusive motivation, even when solidarity is shaped by individualistic tendencies. This underscores the potential of internal motivation as a buffer against exclusionary attitudes—an insight especially relevant for designing interventions in highly individualistic societies.

These findings may be relevant for public and organizational discourse during periods of societal crisis. During crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, public communication and leadership narratives play a critical role in shaping how group boundaries are drawn and how diversity is framed. When crises are presented in zero-sum terms or when outgroups are scapegoated, fear, and threat become potent drivers of exclusion. To counteract this, it is essential that institutions promote narratives that activate broad solidarity, inclusive norms, and value-based commitments to equality. Crisis communication should frame diversity as a shared resource for societal resilience rather than a risk to be managed.

Organizational leaders and policymakers should also recognize that diversity-related attitudes are shaped not only by individual-level beliefs, but by broader cultural and value-laden frameworks. As this study shows, even prosocial values like solidarity can lead to ambivalent outcomes if not anchored in inclusive moral reasoning. Training programs, leadership development, and public education initiatives should therefore go beyond surface-level diversity messaging and engage with the deeper value orientations that shape intergroup behavior.

Finally, this study underscores the importance of distinguishing between affective and instrumental dimensions of intergroup attitudes. While both are responsive to situational and normative cues, they are rooted in different psychological processes and may require distinct intervention strategies. Future research should continue to develop differentiated models of diversity attitudes that capture these nuances and examine how they evolve in response to societal challenges.

5.4 Limitations

The study at hand can make no statements about causal links, due to its cross-sectional design. However, it is based on well-documented correlations, some of which have also been supported in longitudinal studies. For example, Schlueter et al. (2008) demonstrated robust links between fear, threat, and prejudice. Nevertheless, longitudinal research with larger samples should be conducted to replicate and validate the findings presented here.

Although path analyses were used to test theoretically informed models, we acknowledge that the observed relationships do not confirm causal directionality. Rather, the analytical approach serves to evaluate whether the data are consistent with hypothesized psychological mechanisms, such as the influence of value orientations and emotional responses on intergroup attitudes. This approach is especially useful in early-stage or crisis-context research, where experimental control is often not feasible. Future studies employing longitudinal or experimental designs are necessary to more rigorously test these pathways and establish temporal precedence.

It is also important to acknowledge limitations related to the measurement of key constructs. Some of the constructs—particularly those classified as “affective” (e.g., intergroup fear and threat) or “instrumental” (e.g., pro-diversity beliefs)—are conceptually distinct but empirically overlapping. This overlap was reflected in the results of the exploratory factor analysis, where several factors emerged without a dominant structure. These results suggest that the measured constructs may share common variance or tap into broader evaluative tendencies.

Another limitation concerns the relatively small sample size. This was primarily due to the timing of data collection, which took place during the initial COVID-19 lockdown in Germany. Social restrictions and general uncertainty limited recruitment opportunities, especially for a study requiring thoughtful engagement with sociopolitical attitudes. While this constraint reduces the generalizability of the findings, it also strengthens the ecological validity of the study, capturing real-time responses to a historically significant societal crisis. We have therefore framed our conclusions as exploratory and context-specific, rather than broadly generalizable. Future research should seek to replicate and extend these findings using larger and more diverse samples to ensure broader external validity.

Given the time-sensitive and situational nature of the study—conducted during the first COVID-19 lockdown—we used abbreviated and adapted scales to reduce participant burden. While this was appropriate for the context, it may have limited construct clarity and psychometric precision. We have therefore taken care to interpret findings cautiously and have revised the discussion to avoid overemphasizing strict distinctions between affective and instrumental processes.

The specific context in which this study took place may not be the same again, which underlines the unique value of the dataset. Nonetheless, the findings should be seen as exploratory and indicative, rather than conclusive. Future studies should strive to replicate the observed relationships using more comprehensive measures and in culturally and temporally diverse contexts.

Furthermore, only a relatively narrow range of attitudes was examined here. Other dimensions of the Ethnic Diversity Beliefs Scale were not included in the analysis. Future studies should aim to offer a more holistic view by including a broader set of attitudinal outcomes, ideally integrating behavioral indicators to explore how affective and instrumental constructs jointly or independently influence social action.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the study was conducted as part of, but not directly funded by, a third party project of the federal ministry of education and research. Grants for funding include ethic confirmation of all activities associated with the project. Thus no further confirmation was obtained. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

PG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. HS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Banse, R., and Gawronski, B. (2003). Die skala motivation zu vorurteilsfreiem verhalten: psychometrische eigenschaften und validität. Diagnostica 49, 4–13. doi: 10.1026//0012-1924.49.1.4

Decker, O., Kiess, J., Schuler, J., Handke, B., and Brähler, E. (2018). “Die Leipziger Autoritarismus-Studie 2018: Methode, Ergebnisse and Langzeitverlauf,” in Flucht ins Autoritäre – Rechtsextreme Dynamiken in der Mitte der Gesellschaft, eds. O. Decker and E. Brähler (Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag), 65–117.

Degner, J., Meiser, T., and Rothermund, K. (2009). “Kognitive und sozial-kognitive Determinanten: Stereotype und Vorurteile,” in Diskriminierung und Toleranz, eds. A. Beelmann and K. J. Jonas (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 75–93.

Duckitt, J. (2001). A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 33, 41–113. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(01)80004-6

Earley, P. C., and Gibson, C. B. (1998). Taking stock in our progress on individualism-collectivism: 100 years of solidarity and community. J. Manag. 24, 265–304. doi: 10.1177/014920639802400302

Fehr, J., Sassenberg, K., and Jonas, K. J. (2012). Willful stereotype control: the impact of internal motivation to respond without prejudice on the regulation of activated stereotypes. Z. für Psychol. 220, 180–186. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000111

Gawronski, B., and Bodenhausen, G. V. (2006). Associative and propositional processes in evaluation: an integrative review of implicit and explicit attitude change. Psychol. Bull. 132, 692–731. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.692

Genkova, P., and Ringeisen, T. Eds. (2017). Handbuch Diversity Kompetenz: Band 2: Gegenstandsbereiche. Wiesbaden: Springer-Verlag.

Hofmann, J. (2012). Verunsicherungen spalten. Eine Analyse der Quellen von Verunsicherung und ihrer gesellschaftlichen Spaltungen. Kurswechsel 3, 14–21.

Hofmann, J. (2016). “Abstiegsangst und Tritt nach unten? Die Verbreitung von Vorurteilen und die Rolle sozialer Unsicherheit bei der Entstehung dieser am Beispiel Österreichs,” in Solidaritätsbrüche in Europa, eds. W. Aschauer, E. Donat, and J. Hofmann (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 237–257.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kauff, M., Asbrock, F., and Schmid, K. (2020). Pro-diversity beliefs and intergroup relations. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 32, 269–304. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2020.1853377

Kauff, M., Stegmann, S., van Dick, R., Beierlein, C., and Christ, O. (2019). Measuring beliefs in the instrumentality of ethnic diversity: development and validation of the Pro-Diversity Beliefs Scale (PDBS). Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 22, 494–510. doi: 10.1177/1368430218767025

Lynch, K., and Kalaitzake, M. (2020). Affective and calculative solidarity: the impact of individualism and neoliberal capitalism. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 23, 238–257. doi: 10.1177/1368431018786379

Martiny, S. E., and Froehlich, L. (2020). “Ein theoretischer und empirischer Überblick über die Entwicklung von Stereotypen und ihre Konsequenzen im Schulkontext,” in Stereotype in der Schule, eds. S. Glock and H. Kleen (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 1–32.

Mau, S. (2015). Inequality, Marketization and the Majority Class: Why Did the European Middle Classes Accept Neo-Liberalism. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Moreu, G., Isenberg, N., and Brauer, M. (2021). How to promote diversity and inclusion in educational settings: behavior change, climate surveys, and effective pro-diversity initiatives. Front. Educ. 6:668250. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.668250

Nohlen, D. (2002). Lexikon der Politikwissenschaft, Bd. 2: N-Z: Theorien, Methoden, Begriffe. München: Campus.

Opotow, S. (1990). Moral Exclusion and Injustice: An Introduction. J. Soc. Issues 46, 1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb00268.x

Paranti, S. M., and Hudiyana, J. (2022). Current social domination theory: is it still relevant? Psikostudia: J. Psikol. 11, 324–340. doi: 10.30872/psikostudia.v11i2.7614

Pettigrew, T. F. (2016). In pursuit of three theories: authoritarianism, relative deprivation, and intergroup contact. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67, 1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033327

Pfattheicher, S., Nockur, L., Böhm, R., Sassenrath, C., and Petersen, M. B. (2020). The emotional path to action: empathy promotes physical distancing and wearing of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 31, 1363–1373. doi: 10.1177/0956797620964422

Plant, E. A., and Devine, P. G. (1998). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75, 811–832. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.811

Prainsack, B., and Buyx, A. (2017). Solidarity in Biomedicine and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., and Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: a personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 741–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741

Reicher, S., and Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: the BBC prison study. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 45, 1–40. doi: 10.1348/014466605X48998

Schlueter, E., Schmidt, P., and Wagner, U. (2008). Disentangling the causal relations of perceived group threat and outgroup derogation: cross-national evidence from German and Russian panel surveys. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 24, 567–581. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcn029

Sidanius, J., and Pratto, F. (1999). Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stephan, W. G., and Stephan, C. W. (2000). “An integrated threat theory of prejudice,” in Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination, ed. S. Oskamp (Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum), 23–46.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human Groups and Social Categories—Studies in Social Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Uenal, F. (2016). Disentangling Islamophobia: the differential effects of symbolic, realistic, and terroristic threat perceptions as mediators between social dominance orientation and Islamophobia. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 4, 66–90. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v4i1.463

Van Dick, R., and Stegmann, S. (2016). “Diversity, social identity und diversitätsüberzeugungen”, in Springer Reference Psychologie. Handbuch Diversity Kompetenz, eds. P. Genkova and T. Ringeisen (Berlin: Springer), 3–16.

Van Dick, R., Van Knippenberg, D., Hägele, S., Guillaume, Y. R., and Brodbeck, F. C. (2008). Group diversity and group identification: the moderating role of diversity beliefs. Human Relat. 61, 1463–1492. doi: 10.1177/0018726708095711

van Knippenberg, D., and Haslam, S. A. (2003). Realizing the Diversity Dividend: Exploring the Subtle Interplay Between Identity, Ideology, and Reality. Available online at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-08646-004

van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., and Spears, R. (2012). On conviction's collective consequences: integrating moral conviction with the social identity model of collective action. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 51, 52–71. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02000.x

Keywords: social dominance orientation, individualism, motivation to respond without prejudice solidarity, attitudes toward cultural diversity, social dominance orientation, solidarity

Citation: Genkova P and Schreiber H (2025) Crisis overcome?—Affective and instrumental changes of group related attitudes. Front. Soc. Psychol. 3:1514677. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2025.1514677

Received: 21 October 2024; Accepted: 12 May 2025;

Published: 18 June 2025.

Edited by:

Martina Rašticová, Mendel University in Brno, CzechiaReviewed by:

Matthew Hibbing, University of California, Merced, United StatesCristina O. Mosso, University of Turin, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Genkova and Schreiber. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Petia Genkova, cGV0aWFAZ2Vua292YS5kZQ==

Petia Genkova

Petia Genkova Henrik Schreiber

Henrik Schreiber