- 1Department of Psychology, New York University, New York City, NY, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, Long Island University Brooklyn, Brooklyn, NY, United States

Systemic racism carries disparate and varying impacts for members of advantaged and disadvantaged racial groups, not only materially and socially, but also psychically, with consequences for psychological wellbeing. To further explore the varying psychological experience of advantaged and disadvantaged racial groups within a racialized social system, we apply a system justification perspective by examining the degree to which the acceptance vs. rejection of the racialized status quo is associated with ethnic-racial identity attitudes and, consequently, with psychological wellbeing. Specifically, we hypothesized that for racially advantaged group members, racial system justification would positively predict psychological wellbeing, and decreased ethnic-racial salience and ethnic-racial self-hatred would mediate this relationship. For racially disadvantaged groups, we hypothesized that racial system justification would negatively predict psychological wellbeing mediated by its association with racial self-hatred. However, we also tested a competing hypothesis that racial system justification would positively predict psychological wellbeing for the racially disadvantaged mediated by its association with racial salience – reflecting a possible simultaneously palliative effect of racial system justification among the racially disadvantaged. We tested these hypotheses across two studies examining the relationship between racial system justification, ethnic-racial identity salience and self-hatred attitudes, and psychological wellbeing among White and Black Americans. Among White Americans (Study 1, N = 371), we found that racial system justification predicted wellbeing (i.e., the likelihood of reporting zero – vs. one or more – bad mental health days) and that this association with wellbeing was mediated separately by decreased ethnic-racial self-hatred, and to a lesser extent, ethnic-racial salience. In a sample of Black American participants (Study 2, N = 414), we tested the racial system justification–wellbeing association by examining the association between racial system justification and psychological distress. We found evidence of a positive indirect association between racial system justification and psychological distress through increased racial self-hatred, while also finding some evidence of a negative indirect association between racial system justification and psychological distress through decreased racial salience. The results point to the possibility that while racial system justification is associated with wellbeing for racially advantaged groups, it may have simultaneous palliative and pernicious associations with wellbeing for disadvantaged groups, based on its diverging associations with the salience and self-hatred aspects of racial identity attitudes.

A well-documented history of settler colonialism, chattel slavery, Black Codes, Jim Crow segregation, mass incarceration, and the perpetuation of mob and state-sanctioned violence make evident that American society1 has produced a social system replete with racial hierarchy, rooted in an ideology of White superiority and anti-blackness, that organizes the distribution of status and resources on the basis of race and racial position (Alexander, 2012; Bonilla-Silva, 1997; Coates, 2014; Wilkerson, 2020). The racialized nature of the American social system manifests institutionally, interpersonally, and culturally (Jones, 1972), and has produced a status quo characterized by persistent inequality and disparities along racial lines across nearly every domain, including housing, health, employment, and wealth disparities (Reskin, 2012).

Systemic racism limits the prospects of people of color materially and socially, and- more than that- psychically, in that it also negatively impacts the mental health and wellbeing of those disadvantaged by it (Williams and Williams-Morris, 2000; Okazaki, 2009; Thompson and Neville, 1999). Importantly, there is considerable variability in the psychological experience of actors within such a racialized and hierarchical system, particularly around the degree to which they accept vs. reject the system's arrangements (Versey et al., 2019). In what follows, we employ system justification theory to advance the notion that variability in appraisals of the racial status quo predict health and wellbeing, and that this relationship is explained at least in part by aspects of ethnic-racial identity, namely, racial self-hatred and racial salience.

System justification and the psychological experience in a racialized social system

System justification theory (SJT) asserts that in addition to ego and group justification motives for enhanced self- and group-esteem, there exists a system justification motive to justify, legitimize, or defend the status quo (Jost and Banaji, 1994). This psychological attachment can exist for society at large, or for specific aspects of the societal system such as the economic system (Jost and Thompson, 2000), the political system (e.g., Azevedo et al., 2017), the gender system (Jost and Kay, 2005) and—as we contend—the racial system (Saunders et al., 2024).

The psychological motive to justify the status quo is particularly important to understand in a context where the status quo is inegalitarian and persistent (e.g., under a racialized social system) as it drives both the advantaged and disadvantaged to consciously and/or unconsciously endorse cultural ideologies and institutional policies that reinforce racial disparities (Jost et al., 2004; Phelan and Rudman, 2011). In other words, justifying the racial status quo further perpetuates racial inequality and hegemony. But defending the racial status quo may also exacerbate disparities in the psychological advantages and disadvantages afforded by racism. These disparities are the focus of the present research.

System justification and psychological wellbeing

SJT advances that for groups who are advantaged by the status quo, ego- and group-justification motives are consonant with the system justification motive, and thus system justification should be positively associated with self-esteem, in-group favoritism, and long-term psychological wellbeing (Jost and van der Toorn, 2012: Postulate VI). On the other hand, for members of disadvantaged groups the system justification motive conflicts with self- and group-justification motives, and is therefore negatively associated with self-esteem, in-group favoritism, and long-term psychological wellbeing (Jost and van der Toorn, 2012: Postulate VII). This means that for White Americans, legitimizing and upholding a racialized system contributes to a psychological experience characterized by positive mental health: higher self-esteem, greater life satisfaction, and greater resilience against poor mental health such as depression and anxiety. However, upholding a racialized hierarchical system that casts one's group as inferior or undeserving may further disadvantage group members psychologically, as such a response goes against ego- and group-enhancing tendencies that protect self-esteem and mental health.

A host of literature supports SJT's prediction that the consequences of defending the status quo on psychological wellbeing diverge for low- and high-status groups in general (e.g., Bahamondes et al., 2019; Suppes et al., 2019), and specifically for the racially privileged and racially oppressed. For instance, opposition to inequality (i.e., a system justifying ideology) predicted increased self-esteem and decreased neuroticism for White Americans but decreased self-esteem and increased neuroticism for Black Americans (Jost and Thompson, 2000). Additionally, endorsement of the general status quo corresponds with increased life satisfaction for White Americans and decreased life satisfaction for Black Americans (Rankin et al., 2009).

However, contrary to SJT postulate VII, there are two lines of evidence and reasoning suggesting that system justification may also positively predict psychological wellbeing for both low- and high-status groups. First, though there is evidence that system justification positively and negatively predicted psychological wellbeing in highly identified White and Black Americans respectively as SJT suggests, it has also been shown to positively predict psychological wellbeing for Black Americans who were not highly identified with their racial group (O'Brien and Major, 2005). These contradictory, opposing effects have also been demonstrated outside the context of race, in research showing that system-justifying beliefs both buffer and enhance anxiety and depressive symptoms in gay men (Bahamondes-Correa, 2016).

Second, we argue that system justification may positively predict wellbeing for both the racially privileged and the racially oppressed, perhaps as a consequence of its proposed positive effects on affect, or what SJT calls the palliative effect of system justification. Specifically, Jost and Hunyady (2003) hypothesized that the endorsement of system-justifying beliefs and ideologies corresponds with short-term benefits in increased positive- and decreased negative- affect for members of advantaged and disadvantaged groups alike (Postulate VIII). The theory thus traditionally purports a short term, perhaps more superficial palliative effect for both advantaged and disadvantaged groups in terms of affect but diverging effects in terms of more substantive psychological wellbeing. However, we contend that given the established relationship between affect and increased psychological wellbeing (Garcia et al., 2014; Khazanov and Ruscio, 2016; Mehrabian, 1997; Steptoe et al., 2008), this proposed palliative effect of system justification presents another avenue which complicates the relationship between system justification and psychological wellbeing. So, though system justification theory traditionally proposes that a palliative effect of system justification should converge for advantaged and disadvantaged groups for affect while its associations with psychological wellbeing should diverge, we contend that system justification may also have converging positive associations with psychological wellbeing for advantaged and disadvantaged groups, similar to (and perhaps because of) its palliative effect with regard to affect. Thus, we may see signs of palliative effects of system justification in terms of its association with psychological health or wellbeing.

Against this mixed background, the present paper aims to reconcile the convergent and divergent effects of system justification for racially privileged and racially oppressed groups by examining the pernicious vs. palliative effects of racial system justification for Black and White Americans. In so doing, we address our primary research question: What is the relationship between system justification and psychological wellbeing for racial actors under the system of racism? Specifically, on one hand, we apply the SJT postulate that system justification will positively predict the wellbeing of White Americans but negatively predict the wellbeing of Black Americans. However, in a departure from the traditional SJT conceptualization, and with the goal of extending the palliative postulate beyond affect, we also examine whether justifying the racial status quo will also positively predict psychological wellbeing for Black Americans. Notably, we do so using a new self-report measure of racial system justification (RSJ).

Considering both possibilities together, then, implies that RSJ may exhibit a simultaneously positive and negative relationship with wellbeing, particularly for the racially oppressed. One way to explore this possibility involves examining potential mechanisms by which RSJ may become associated with psychological wellbeing similarly or differently for privileged and oppressed racial actors. In doing so, we aim to both: (1) establish the (R)SJ—psychological wellbeing association; and (2) reveal the mechanisms through which positive and negative associations may simultaneously occur. We set out to do so by examining whether racial system justification shapes aspects of ethnic-racial identity similarly or differently for White Americans and Black Americans in the U.S.

Ethnic-racial identity attitudes as potential mediators of the system justification—wellbeing association

The system of racism invariably imposes racial categories on all actors, rooted in the institutional practice of assigning status and rights based on race during the colonial and antebellum periods (Patterson, 1982; Wilkerson, 2020) and carried forth into present day via both institutional and cultural practices (Nobles, 2002; Schor, 2017; Jenkins, 1994). As such, we posit that, because ethnic-racial identity is inextricable from the broader system of racism, one's ethnic-racial identity attitudes would be tied to one's psychological and ideological response to the system of racism. We have already offered evidence that group identification can moderate the relationship between system justification and psychological wellbeing, producing differing effects for racially oppressed groups based on their degree of identification (O'Brien and Major, 2005).

However, O'Brien and Major (2005) examined only one dimension of identity—strength of identification. Yet, some psychological theories about racial identity have also emphasized that racial identification does not only vary in strength but in its attitudinal and ideological nature/content. One of the earliest theories to emphasize the attitudinal dimension of racial identity was Cross' Nigrescence theory (Cross, 1971; Cross and Vandiver, 2001)2 which posits that for Black Americans, racial identity can vary along six attitudinal dimensions: assimilation, miseducation, self-hatred, anti-White, Afrocentricity, and multiculturalist-inclusive attitudes. The theory and accompanying scales were subsequently extended beyond racial identification among Black Americans exclusively to include ethnic and racial identity among all groups, and to include a racial salience dimension. Though the theory and accompanying scales identify and measure multiple attitudinal aspects of ethnic and racial identity, we focus on two specific dimensions—racial salience and racial self-hatred—that we posit may operate as intervening mechanisms in the relationship between racial system justification and psychological wellbeing, due to: (1) their established relationship with psychological wellbeing (Telesford et al., 2013; Whittaker and Neville, 2010); and (2) their predicted association with racial system justification.

Racial self-hatred as mediating mechanism in the RSJ—wellbeing association

According to Cross' Nigrescence model, racial self-hatred—the extent to which individuals dislike their racial group (Worrell et al., 2019), is grounded in internalized racism, which can be defined as the internalization or acceptance of negative or stereotypical ideas about one's own racial group (Willis et al., 2021). Following this conceptualization, we propose that members of racially oppressed groups who justify, legitimize, or defend a racial system which disparages them (i.e., who are higher in racial system justification), may be more likely to experience or display racial self-hatred, and in turn, poorer psychological wellbeing.

Indeed, prior research has established the relationship between system justification and internalized racism, for example, in observing a link between system justification and outgroup favoritism—a preference for a dominant outgroup over one's ingroup—amongst racially oppressed groups as well as other disadvantaged groups (Jost, 2013; Jost et al., 2004). Additionally, dating back at least as far as the late 1930s, ample research has empirically demonstrated the nefarious effects of self-hatred on psychological wellbeing for racially oppressed groups (Clark and Clark, 1939). Across a number of studies, racial self-hatred has been shown to be negatively related to self-esteem (Worrell et al., 2023) and positively associated with symptoms of negative mental health (Worrell et al., 2011). Internalized racism, more broadly, has also been linked to poor psychological wellbeing, with research demonstrating it is directly and indirectly related to long term psychological distress in Black Americans (i.e., the presence of depressive and anxiety symptoms; Graham et al., 2016; Mouzon and McLean, 2017; Willis et al., 2021), Asian Americans (Godon-Decoteau et al., 2024), and other ethnic/racial minorities (James, 2020).

Conversely, we would not anticipate a similar relationship between racial system justification, self-hatred, and thus psychological wellbeing for those privileged by the racialized system, such as White Americans. While legitimization of the racial status quo might produce acceptance of negative messages about one's group for the racially marginalized, the opposite would be more likely for the groups granted positive status, power, and regard within the system. In fact, those privileged group members who justify the racial status quo which grants them their privileged position might be protected from any racial self-hatred that could arise from racial guilt or shame around unearned privileges, especially if this guilt is turned inward (Matias, 2016; Yancy, 2018). Thus, it is conceivable that legitimizing the racialized social system as fair and legitimate may be associated with greater psychological wellbeing for White Americans, because it is associated with less racial self-hatred (relative to those who do not justify the racial status quo). As such, we conceive of racial self-hatred as a potential mediating mechanism explaining divergence in association between racial system justification and psychological wellbeing in those oppressed vs. privileged by the system of racism.

Racial salience as mediating mechanism in the RSJ—wellbeing association

Racial salience refers to the degree to which one's race has situational relevance (Sellers et al., 1997), yet this aspect of racial identity, though mentioned and emphasized, did not originally feature as one of the attitudinal components measured by Cross' Nigrescence attitudinal model (Cross and Vandiver, 2001). A measure of racial salience, defined as the extent to which “individuals consider race in their daily lives” (Worrell et al., 2019, p. 406), was later included when an alternate version of the scale—the Cross Ethnic Racial Identity Scale—was developed (CERIS-A; Worrell et al., 2019, 2020). It is no mistake, we believe, that the necessity of a racial salience subscale became inescapable at the point when theory and measurement was being extended beyond Black racial identity to include other ethnic and racial identities—and specifically White racial identity. Given the dynamics of power and hegemonic Whiteness, particularly in the U.S. racialized system, social theorists have argued that White identity is characterized by a form of invisibility or “racelessness” where race is not acknowledged or considered in the everyday life and outlook of White individuals (Dottolo and Stewart, 2013), because they are simply seen as the norm, while others are seen as having race (Bell, 2020).

We contend that perceived “racelessness” may be associated with a motive to legitimize the privileges and benefits enjoyed by White Americans, and thus may be related to racial system justification (Dovidio et al., 2015). Indeed, Jayakumar and Adamian (2017), who examined colorblind frames of race and racism among white students at HBCUs noted:

“[Race-less-ness] involves “seeing color” but disassociating from being white. This allows one to believe race does not matter— including seeing or discussing race—and to instead selectively note the salience of white identity. Ultimately, race-less-ness permits whites to avoid accountability for racism and privilege, or to avoid changing in any way that would sacrifice group advantage or dismantle the status quo” (p. 921).

This “racelessness” is thus part of the racial privilege of White Americans (Bonilla-Silva, 1997; Phillips and Lowery, 2018; Versey et al., 2019), because it shields them from the burdens of racial guilt and discomfort (Jayakumar, 2015; Leonardo and Porter, 2010) and allows for the maintenance of positive self-regard (Phillips and Lowery, 2018). As such, we propose that racial salience predicts increased psychological wellbeing, and may function as an important mediating mechanism in the relationship between (racial) system justification and psychological wellbeing for White Americans. Specifically, we advance that the proposed positive association between system justification and wellbeing for the racially privileged may unfold alongside a decrease in the salience of race, as this motivation to legitimize the racial status quo may encourage this blindness to race. Blindness to race may, moreover, protect the psychological benefits to self-esteem afforded by White Americans' position within the racial status quo.

In the same vein, acknowledging the empirical evidence of an occasional positive association between system justification and wellbeing for disadvantaged groups (Bahamondes-Correa, 2016; O'Brien and Major, 2005), we propose that racial system justification will also negatively predict racial salience and positively predict psychological wellbeing for members of racially oppressed groups. Cluster-analytic research conducted with Black participants' Cross' Racial Identity Scale scores supports this idea. Though the race salience subscale had not yet been introduced to the CRIS, a “Low Race Salience” cluster (i.e., those with relatively low scores across each of the CRIS subscales, indicating avoidance of focus or importance on race) was identified in prior research (Whittaker and Neville, 2010; Telesford et al., 2013). Telesford et al. (2013), in particular, found that Black participants in the “Low Race Salience” cluster (along with the “Multiculturalist” cluster) reported substantially less distress than those in the other clusters. Thus, there is at least some evidence that low attention to race may have a psychological benefit for those disenfranchised by racism.

What is more, though there has not yet, to our knowledge, been any research demonstrating an association between system justification and race salience, colorblind ideology (an ideological and attitudinal denial of the significance or role of race) is related to psychological false consciousness (defined as “false beliefs that serve to work against one's individual or group interest”; Neville et al., 2005) in Black Americans. Specifically, Neville et al. (2005) found that it corresponded positively with social dominance orientation, blaming of victims, and internalized oppression among Black participants. In other words, despite the general higher salience of race for the racially oppressed, compared to White Americans (Worrell et al., 2020), justification of the racial status quo may also be associated with minimized attention to or focus on race as a self-protective response, that is, to (consciously or unconsciously) avoid an increase in self-hatred and accompanying negative effects on self-esteem and wellbeing. Indeed, Coleman et al. (2013) found that, contrary to their initial hypothesis, colorblind attitudes negatively predicted racial stress in Black American participants.

As such we propose that, while racial self-hatred may clarify why the SJ—wellbeing association diverges for racially advantaged and disadvantaged groups, racial salience may simultaneously (and paradoxically) explain convergence in the RSJ—wellbeing association for advantaged and disadvantaged groups—and, correspondingly, the proposed “palliative” effect of system justification.

Overview of the present research

In the present research, we examined the relationship between racial system justification and psychological wellbeing in both a racially advantaged and racially oppressed group and sought to understand the converging and diverging associations between racial system justification and wellbeing by examining the mediating role of two aspects of racial identity: racial salience and racial self-hatred. We do so by testing the following hypotheses across two studies:

Hypotheses

H1: In racially advantaged groups (i.e., White Americans), racial system justification will positively predict psychological wellbeing. Ethnic-racial salience and ethnic-racial self-hatred will each independently mediate this relationship, such that racial system justification will predict both decreased ethnic-racial salience and decreased ethnic-racial self-hatred, which in turn will positively predict wellbeing;

H2: In racially disadvantaged groups (e.g., Black Americans), racial system justification will negatively predict psychological wellbeing. Racial self-hatred will mediate the relationship, such that racial system justification will predict increased racial self-hatred, which in turn will negatively predict wellbeing.

However, reflecting the simultaneously palliative effect of racial system justification, but considering the extension of this palliative effect beyond affect, we test a competing hypothesis that:

H3: Amongst racially disadvantaged groups (e.g., Black Americans), racial system justification will positively predict psychological wellbeing, and racial salience will mediate the relationship such that racial system justification will predict decreased racial salience, which in turn will positively predict wellbeing.

In Study 1, we tested our hypotheses by examining whether a measure of racial system justification would positively predict scores on a measure of mental health in a sample of White American participants; we further examined whether this relationship would be mediated by measures of ethnic-racial salience and ethnic-racial self-hatred. In Study 2 we tested hypotheses 2–3 by examining whether racial system justification both positively and negatively predicted psychological distress in a sample of Black American participants.3 We also tested whether the relationships between racial system justification and psychological distress were mediated by racial self-hatred and racial salience.

Study 1

Our first study examined the RSJ—wellbeing association in White Americans, generally regarded as the racial group occupying the highest position in the American racial hierarchy (Zou and Cheryan, 2017). We hypothesized that racial system justification would negatively predict wellbeing and decreased ethnic-racial salience, and that ethnic-racial salience and self-hatred would mediate this relationship (H1). To explore this hypothesis, we administered measures of ethnic-racial identity, racial system justification, and mental health to an online sample of White US Adults. Operationally, we therefore expected racial system justification to negatively predict the number of bad mental health days and to negatively predict ethnic-racial salience and ethnic-racial self-hatred. Additionally, we expected racial system justification to indirectly predict the number of bad mental health days through decreased racial salience and decreased racial self-hatred.

Methods

Participants

A total of N = 525 participants were recruited through Amazon MTurk in September of 2018. The data were collected for an ongoing research program on the development and validation of the racial system justification scale (Saunders et al., 2024). Several measures not examined in the present analyses were administered to participants in the service of examining the construct validity of the racial system justification scale. These measures included established antecedents, consequences, and correlates of published system justification measures. We did not pre-register any hypotheses, though we selected variables appropriate for testing many of system justification theory's core postulates (Jost, 2020). To ensure data quality, we excluded data from participants whose responses were flagged as dubious using Bot Shiny App, who produced duplicate responses, which we verified using geolocation data, and who completed the study in < 25% of the expected completion time, in keeping with best practices for crowdsourced data (Robinson et al., 2019). After these exclusions, we arrived at an initial sample of 474 participants. This initial sample was predominantly White (~83%) because we did not originally restrict data collection based on race. However, given the specificity of our first two hypotheses for White Americans and the small number of participants in each of the other racial/ethnic groups, we restricted our analysis sample to include only participants who identified as White (N = 371, Mage = 41.47, SDage = 12.34, 52% Female).

Procedure and measures

After providing informed consent, participants responded to a series of questions in an online survey administered through Qualtrics which included the measures described below (in order of appearance), along with other measures not relevant to the study. Participants then completed demographic questions and read the debriefing form. Study procedures were approved by the Long Island University-Brooklyn Institutional Review Board (IRB# 17/01-019).

Ethnic-racial salience (salience)

We administered items from the Cross Ethnic-Racial Identity Scale, Adult (CERIS-A; Worrell et al., 2020) which included the 4 items from the ethnic-racial salience subscale (e.g., “When I read the newspaper or a magazine, I always look for articles and stories that deal with race and ethnic issues.”), and participants indicated their agreement with the items on a bipolar Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). We computed a salience score by averaging across the four items, and it had adequate reliability (α = 0.73, McDonald's ω = 0.76).

Ethnic-racial self-hatred (self-hatred)

Participants completed four items from the CERIS-A measuring their endorsement of ethnic-racial self-hatred (e.g., “I go through periods when I am down on myself because of my ethnic group membership,” “Privately, I sometimes have negative feelings about being a member of my ethnic/racial group.”) on 7-point bipolar scales (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree), with higher scores reflecting greater self-hatred. The four items were averaged to produce a reliable index of self-hatred (α = 0.89, ω = 0.92).

Racial System Justification (RSJ)

We used a novel measure of racial system justification (Saunders et al., 2024) constructed by drawing from the general and economic system justification scales (Kay and Jost, 2003; Jost and Thompson, 2000). Participants were asked to rate from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree) their agreement with each of the 16 items. Sample items include: “In general, I find society to be fair for all racial groups,” and “Everyone in America, no matter their race, has a fair shot at wealth and happiness.” We averaged participants' responses to compute a reliable index of racial system justification (α = 0.91, ω = 0.93; see Supplementary material for the complete list of items administered).

Psychological wellbeing (number of bad mental health days)

To measure psychological wellbeing, we administered a single item measure of mental health which read: “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” Participants indicated the number of days up to 30. This single item measure was administered as a measure of mental health in a sample of 1.2 million U.S. adults4 (Chekroud et al., 2018).

Demographic questions

Toward the end of the study participants responded to several demographic questions, including measures of age, gender, education, income, and political orientation.

Data-analytic plan

To test our hypotheses, we ran multiple regression models followed by mediation analyses. To test bivariate relationships between RSJ, salience, self-hatred, and mental health, we conducted zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) regression analyses because our dependent variable produced count data which exhibited overdispersion (and excessive frequency of 0′s), making linear or poisson regression models less appropriate (Zeileis et al., 2008). We conducted these analyses in R using the pscl package (Jackman, 2024). To test the role of salience and self-hatred in mediating the relationship between RSJ and mental health, we conducted single and dual-mediator path analyses using the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012). Our regression and path analyses controlled for participant gender (dummy coded, where male = 1), age (centered), income (centered), and educational level (centered), given known associations between demographic variables and wellbeing (Kessler et al., 2010; Lorant et al., 2003; Seedat et al., 2009).

Results

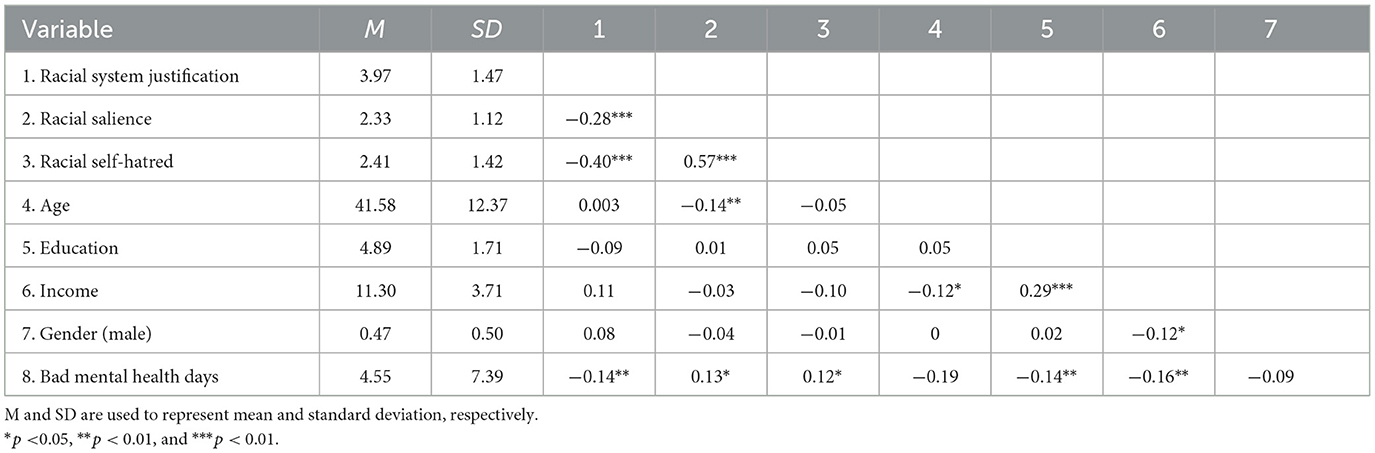

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among the study variables are reported in Table 1.

Regression analyses

We first regressed mental health on White participants' racial system justification, using a ZINB regression and adjusting for participants' age, gender, income, and education.5 In the count model (i.e., the negative binomial model with log link), RSJ did not significantly predict the number of poor mental health days (b = −0.076, SE = 0.061, z = −1.257, p = 0.209). However, in the zero-inflation model (i.e., the binomial model with logit link), RSJ significantly and positively predicted the likelihood of reporting zero poor mental health days (i.e., being in the “excess zero” group, b = 0.238, SE = 0.111, z = 2.157, p =0.031).

To examine the relationships between our predictor and mediator variables, we regressed salience and self-hatred on racial system justification, reporting HAC standard errors to address potential autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity issues, and found that RSJ negatively predicted salience (b = −0.226, SE = 0.047, β = −0.30, t(365) = −4.773, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.302, −0.151]) and self–hatred (b = −0.388, SE = 0.047, β = −0.403, t(360) = −8.286, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.481, −0.296]).

We then examined the relationship between our mediator and outcome variables using ZINB regression. In the count model, neither racial salience nor racial self–hatred significantly predicted the number of poor mental health days (salience: b =0.027, SE = 0.071, z = 0.373, p =0.709; self–hatred: b = −0.002, SE = 0.055, z = −0.40, p =0.968). In the zero–inflation model, both salience and self–hatred negatively predicted the likelihood of reporting zero poor mental health days (salience: b = −0.381, SE = 0.16, z = −0.137, p =0.017; self–hatred: b = −0.386, SE = 0.12, z = −3.226, p =0.001).

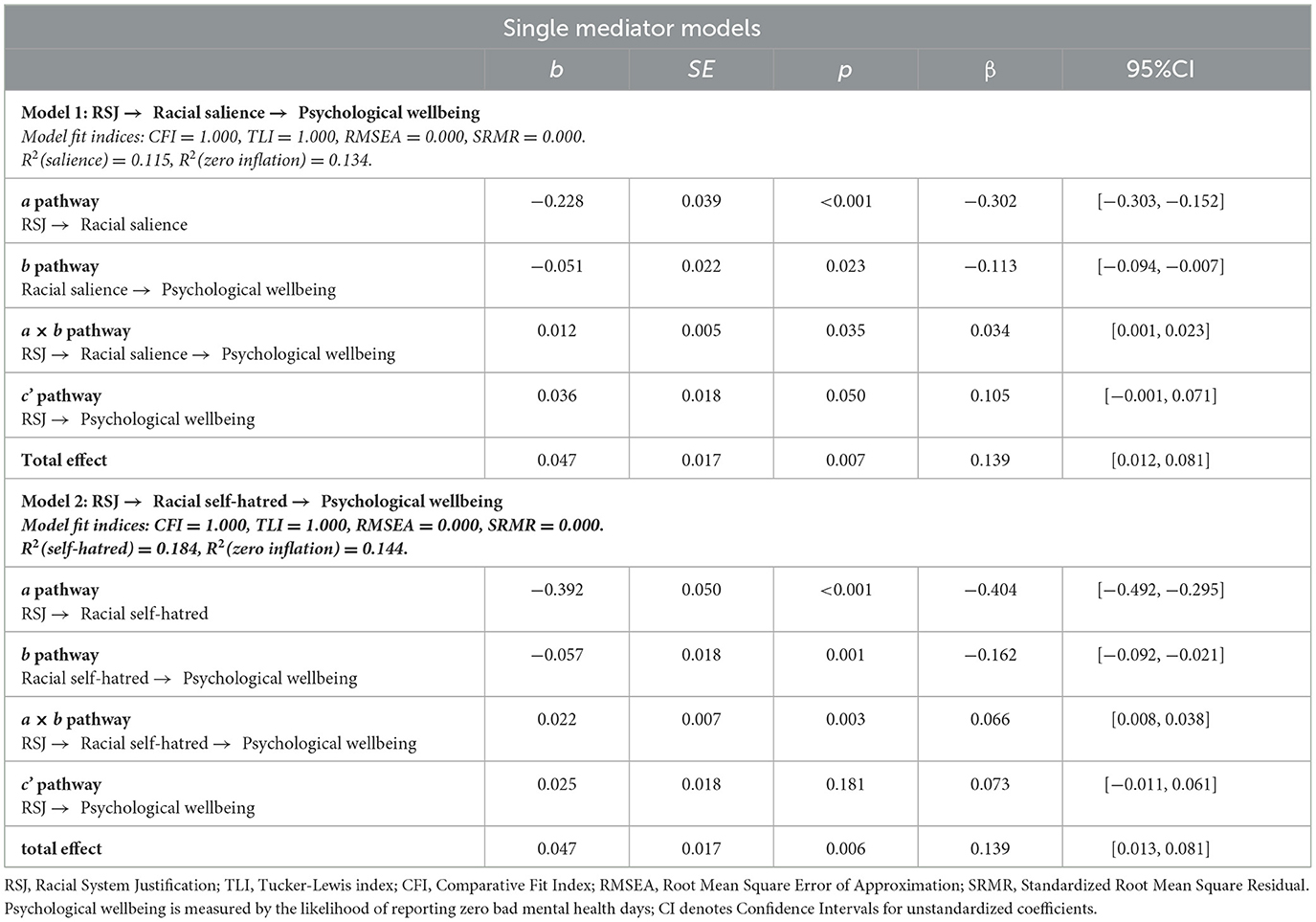

Mediation analyses

We conducted path analyses to examine whether the relationship between racial system justification and psychological wellbeing is explained by ethnic-racial identity. Specifically, we employed path analysis to reveal why, in psychological terms, variability in perceptions of the racial status quo might be associated with psychological wellbeing. In other words, we examined the degree to which, in White Americans, the RSJ—wellbeing association is explained, in part, by differences in ethnic-racial identity.

We conducted a series of 4 path analyses with 10,000 bootstrap resamples, estimating a saturated, manifest variable model, again adjusting for demographic variables. Since the two distinct processes (count and zero-generated) involved in the ZINB regression could not be accounted for in this model, we computed the zero-inflated factor—indicating the likelihood of reporting zero bad mental health days—as our outcome variable. Because the models were saturated, fit indices for all models were as expected: χ2, RMSEA, and SRMR values were all 0, and CFI and TLI values were 1. A full report of the results from these 4 models (including direct paths and total effects) are summarized in Tables 2, 3.

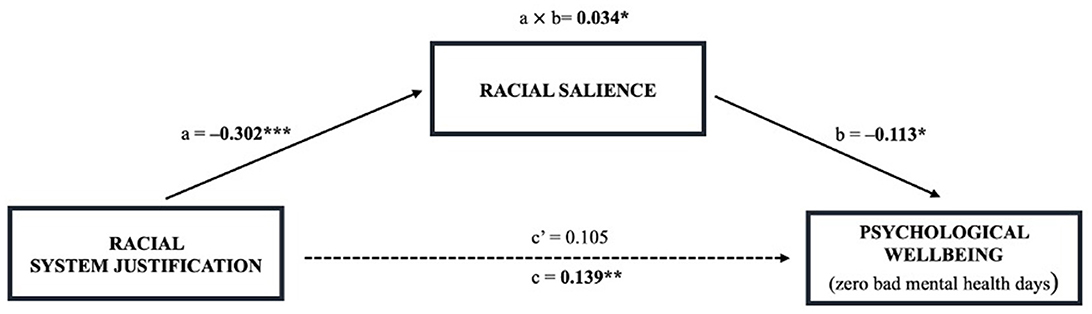

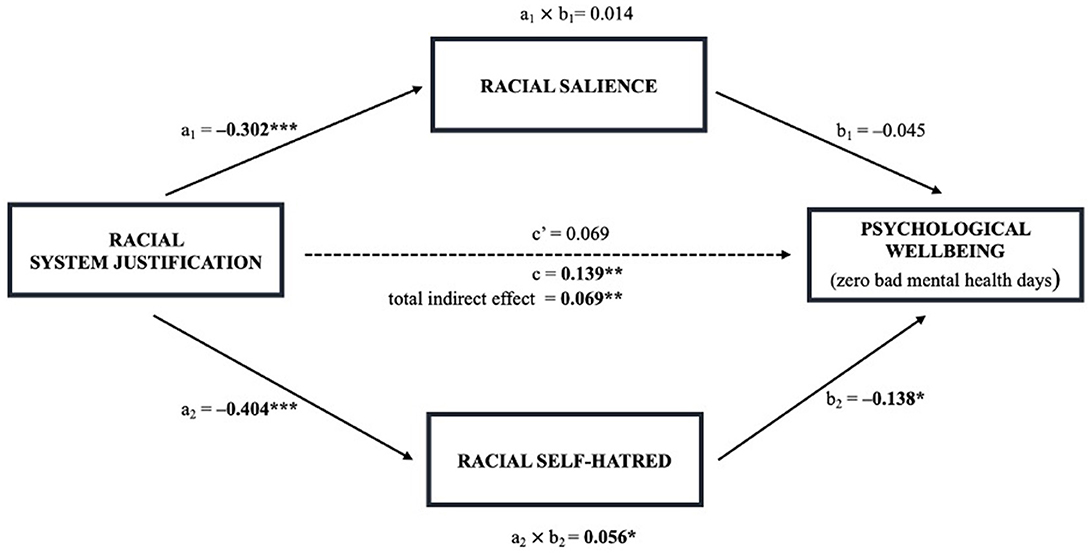

First, we tested two separate single-mediator models to examine whether each mediator individually explains the relationship between RSJ and zero bad mental health days (i.e., zero-inflation factor). In model 1, which explained 13.4% of our outcome variable, we examined whether RSJ predicted zero bad mental health days indirectly through salience, finding a significant indirect effect (β = 0.034, p = 0.035) and a nonsignificant direct effect (β = 0.105, p = 0.05) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Path model illustrating the mediation by racial salience of the effects of racial system justification on psychological wellbeing. Numerical values are standardized regression coefficients for the full model. Bolded values indicate significant coefficients (p < 0.05), and broken lines indicate non-significant paths (p > 0.05). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

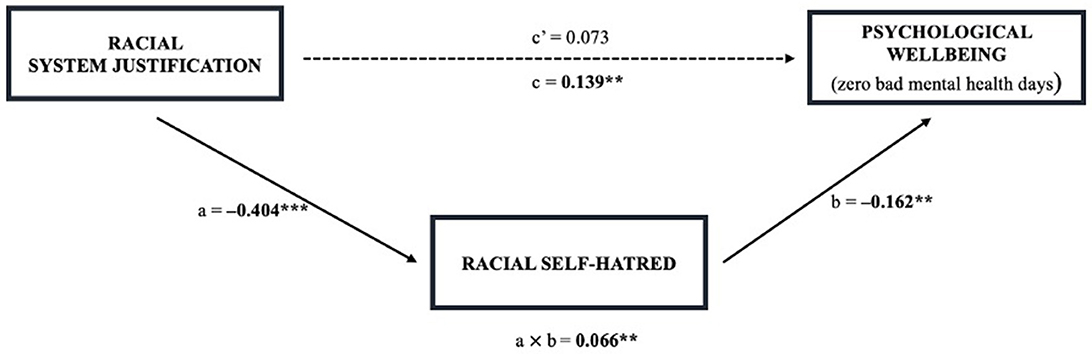

In model 2, which explained 14.4% of our outcome variable, we examined whether RSJ predicted zero bad mental health days indirectly through self-hatred, finding a significant indirect effect (β = 0.066, p = 0.003) and a nonsignificant direct effect (β = 0.073, p = 0.181) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Path model illustrating the mediation by racial self-hatred of the effects of racial system justification on psychological wellbeing. Numerical values are standardized regression coefficients for the full model. Bolded values indicate significant coefficients (p < 0.05), and broken lines indicate non-significant paths (p > 0.05). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

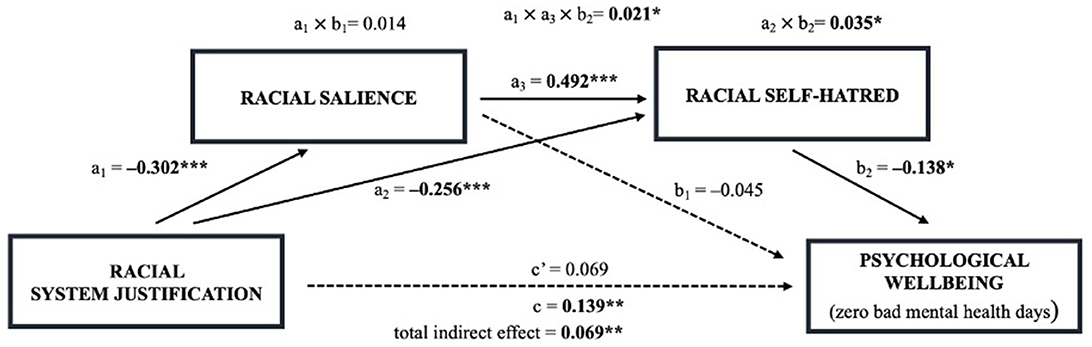

In model 3, we ran a dual-mediator analysis combining both mediators into a single model to determine whether both mediators still uniquely contributed independent effects when considered together. This model, which explained 14.6% of the outcome's variance, produced a significant indirect effect for self-hatred (β = 0.056, p = 0.025), but not for salience (β = 0.014, p = 0.447) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Path model illustrating the dual mediation by racial salience and racial self-hatred of the effects of racial system justification on psychological wellbeing. Numerical values are standardized regression coefficients for the full model. Bolded values indicate significant coefficients (p < 0.05), and broken lines indicate non-significant paths (p >0.05). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

We then conducted a fourth path analysis to explore two explanations for the results found across the first 3 models. First, the indirect relationship of RSJ on zero bad mental health days through salience is significant on its own but was no longer significant when considered together with self-hatred. Secondly the dual-mediator model does not explain much more of the variance of the outcome variable than the self-hatred only model−14.6%, compared to 14.4%—while the salience-only model explained only 13.4%. Given this pattern of results, we sought to determine which of two explanations seemed more likely; (1) that self-hatred is the primary pathway for the relationship between RSJ and zero bad mental health, with salience explaining little unique variance beyond its shared variance with self-hatred or; (2) that the mediating role of salience is part of a sequential process, operating through self-hatred. We thus tested a serial-mediator model, which again explained 14.6% of the outcome's variance, and results indicated a significant indirect sequential pathway of RSJ on zero bad mental health, through salience and self-hatred (β =0.021, p = 0.047), and a significant indirect pathway through self-hatred alone (β = 0.035, p =0.028) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Path model illustrating the serial mediation by racial salience and racial self-hatred of the effects of racial system justification on psychological wellbeing. Numerical values are standardized regression coefficients for the full model. Bolded values indicate significant coefficients (p < 0.05), and broken lines indicate non-significant paths (p > 0.05). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

Together these results demonstrate support for our first hypothesis that racial system justification would positively predict psychological wellbeing for White Americans, and that this relationship would be mediated by decreased ethnic-racial salience and ethnic-racial self-hatred.

In this study, we operationalized psychological wellbeing in terms of mental health, employing a measure of the number of poor mental health days. As such, in line with our hypothesis, we expected that racial system justification would negatively predict the number of poor mental health days. This would suggest that White American participants who were higher in racial system justification would report experiencing fewer bad mental health days, serving as one indicator of greater psychological wellbeing. While our results did not yield a significant predictive relationship between racial system justification and the number of bad mental health days reported, racial system justification positively predicted the likelihood of reporting zero bad mental health days, indicating that it predicted whether or not our participants did or did not experience bad mental health days. We also found support for our hypothesis that this relationship would be mediated by decreased ethnic-racial salience and ethnic-racial self-hatred.

In line with our rationale for this hypothesis, we found that both ethnic-racial salience and ethnic-racial self-hatred negatively predicted the likelihood of reporting zero mental health days (but did not predict the number of bad mental health days), suggesting that White Americans higher in ethnic-racial salience and/or self-hatred were more likely than not to experience some bad mental health days. We also observed a significant negative effect of racial system justification for racial salience and self-hatred scores, indicating that while these ethnic-racial identity attitudes may predict poorer mental health, White participants higher in racial system justification are less likely to hold them.

Accordingly, in line with our hypothesis, we found evidence that both racial salience and self-hatred mediated the relationship between racial system justification and psychological wellbeing (i.e., likelihood of reporting zero mental health days) when considered separately. Interestingly, though, we found that racial salience no longer uniquely contributed to the indirect relationship when considered along with self-hatred. Instead, racial salience played a mediating role through self-hatred, indicating that White America's racial system justification negatively predicts racial salience, which in turn negatively predicts racial self-hatred, and thus, positively predicts psychological wellbeing (i.e., zero bad mental health days). Though we did not hypothesize a sequential relationship, this finding is not necessarily surprising as it is in line with our reasoning that racial salience shields White Americans from racial guilt in the service of self-esteem maintenance.

In Study 2, we turn to investigating the relationship between racial system justification and psychological wellbeing in Black U.S. residents.

Study 2

Our goal with Study 2 was to examine the intervening role of racial salience and racial self-hatred in Black Americans, often regarded as the racial group occupying the lowest position in the American racial hierarchy (Sidanius and Pratto, 2001; but see Zou and Cheryan, 2017). Thus, we employed measures of system justification, racial identity attitudes, and psychological distress in an online sample of Black Americans to test our hypotheses. In our second hypothesis we proposed that racial system justification would negatively predict psychological wellbeing through increased self-hatred (H2). Racial system justification, then, should positively predict racial self-hatred, which in turn should positively predict psychological distress. We further predicted (H3) that racial system justification would positively predict psychological wellbeing via decreased racial salience, therefore we expected that RSJ would also negatively predict racial salience, and in turn negatively predict psychological distress through racial salience.

Methods

Participants

Data used in this study were originally collected for a dissertation that examined the role of racial identity, coping, and threat appraisal in the relationship between discrimination and mental health in Black Americans (Soyeju, 2023). A total of 493 participants were recruited through Cloud Research, a crowdsourcing site, between February and August of 2022. All participants included in the study identified as Black, 18 years or older, and U.S. residents. We excluded participants who did not identify as Black, who submitted low quality data (e.g., random responses), who failed more than 1 of our 3 attention checks and whose data was flagged as dubious using IP Hub which screens participants based on IP address, following best practices for crowdsourced data (Robinson et al., 2019). After exclusions, we arrived at a final sample of 414 participants (Mage = 36.1, SDage = 11.18, 33.57% Female).

Procedure and measures

After providing informed consent, participants responded to a series of questions on an online survey administered through Qualtrics which included the measures described below, as well as other measures not relevant to this study. The measures appeared in the questionnaire in the order listed (not accounting for unreported measures), and all study procedures were approved by the Long Island University-Brooklyn Institutional Review Board (IRB# 21/12-165).

Racial system justification

We used the same measure of racial system justification as in Study 1 (α = 0.78, McDonald's ω = 0.86; Saunders et al., 2024) and once again computed a single score by averaging participants' responses across the 16 items.

Racial Salience and racial self-hatred

To measure racial self-hatred and racial salience, we used the expanded version of the Cross Racial Identity Scale (CRIS; Worrell et al., 2020) which added the racial salience subscale to the existing six subscales measuring attitudinal dimensions of Black racial identity. Racial salience (e.g., “When I walk into a room, I always take note of the racial make-up of the people around me”; α = 0.75, ω = 0.79) and self-hatred (e.g., “I sometimes struggle with negative feelings about being Black”; α = 0.91, ω = 0.94) were measured with five items each on seven-point bipolar scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Psychological wellbeing (psychological distress)

Psychological distress was assessed with the 6-item version of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6; Kessler et al., 2010), which measures depressed mood (2 items), motor agitation, fatigue, worthless guilt, and anxiety. Participants indicated on a scale from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time) how often during the last thirty days they felt the respective feeling (e.g., “nervous”, for a measure of anxiety, “hopeless” for a measure of depressed mood, and “restless or fidgety” for a measure of motor agitation). A total score was computed by summing responses on each of the items (α = 0.92, ω = 0.94), with higher scores indicating greater distress.

Demographic questions

Our demographic measures once again included measures of age, gender, education, and income.

Data-analytic plan

Our data-analytic plan mirrored the approach employed for Study 1. We ran multiple regression models followed by path analyses using the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012), again controlling for participants' gender (dummy coded, where male = 1), age (centered), income (centered), and educational level (centered) (see text footnote 5). Furthermore, to address potential issues with violations of regression assumptions (specifically, linearity and normality of residuals) in our regression and mediation models, we applied a log transformation to the psychological distress variable and ran robust regression models. Specifically, we applied a log(x + 1) transformation to accommodate zero values (Field, 2018) and we use the lmrob() function from the robustbase package in R which uses MM-estimation to produce more reliable coefficient estimates in cases of assumption violations (Koller and Stahel, 2011).

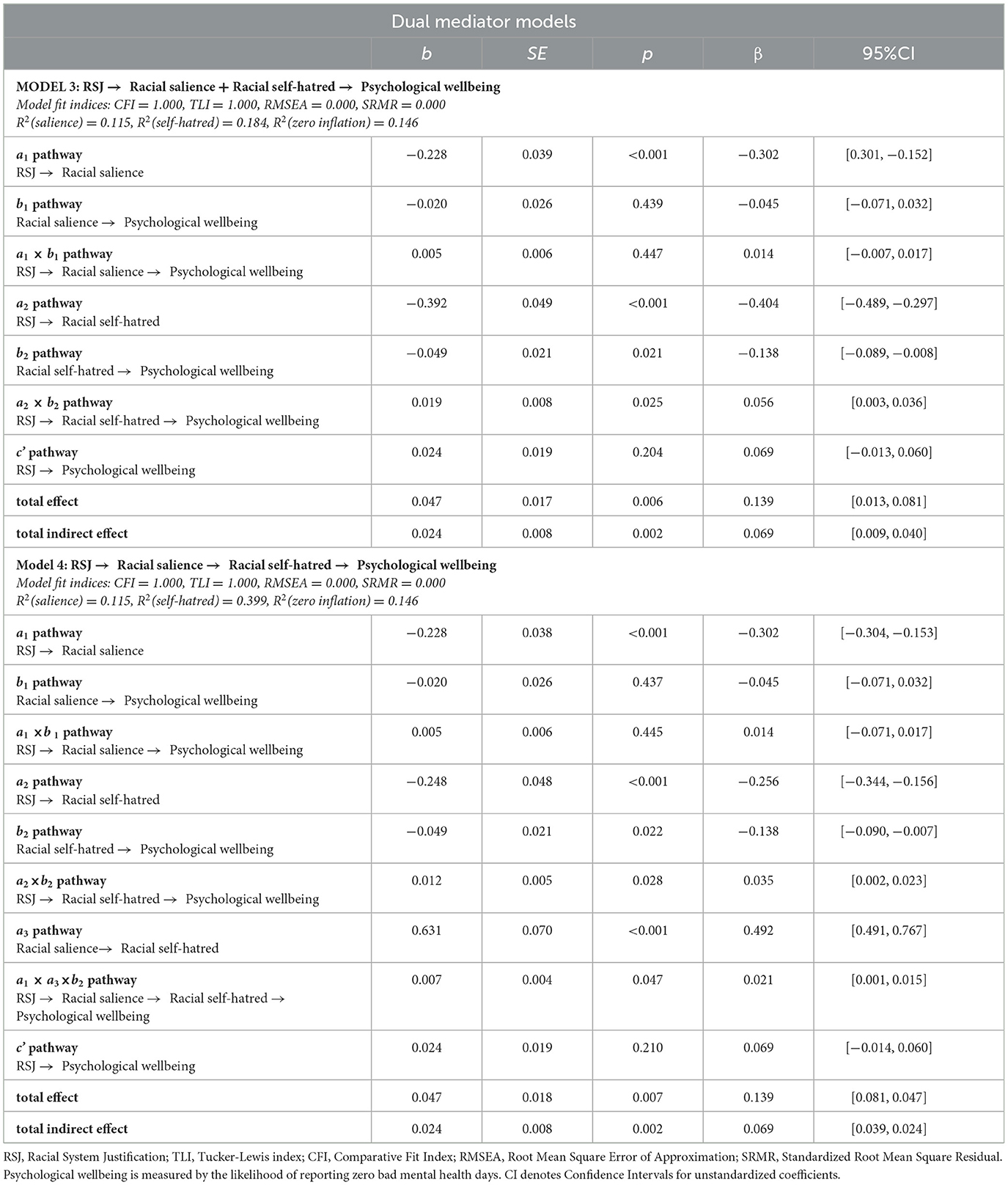

Results

Table 4 lists the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the primary variables. Below, we report and discuss results from both linear regression and mediation analyses for our first outcome variable, psychological distress (log transformed).6

Racial system justification and psychological distress

Linear regression analyses

We first regressed psychological distress on participants' racial system justification and found no effect, b = −0.029, SE = 0.045, β = −0.034, t(365) =-0.645, p = 0.519, 95% CI [−0.119, 0.06].

To examine the relationship between racial system justification and each of our mediator variables, we regressed our measures of racial self–hatred and racial salience on racial system justification, finding that racial system justification positively predicted self–hatred: b = 0.07, SE = 0.023, β = 0.15, t(406) = 3.002, p = 0.003, 95% CI [0.024, 0.116] and negatively predicted racial salience: b = −0.256, SE = 0.058, β = −0.216, t(406) = −4.703, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.37, −0.141]. To examine the relationship between our mediator variables and our outcome variable, we next regressed our measure of psychological distress on self–hatred, finding a positive effect, b = 0.175, SE = 0.026, β = 0.293, t(406) = 6.685, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.124, 0.227], and on racial salience which also yielded a positive effect, b = 0.103, SE = 0.037, β = 0.143, t(406) = 2.748, p = 0.006, 95% CI [0.029, 0.176].

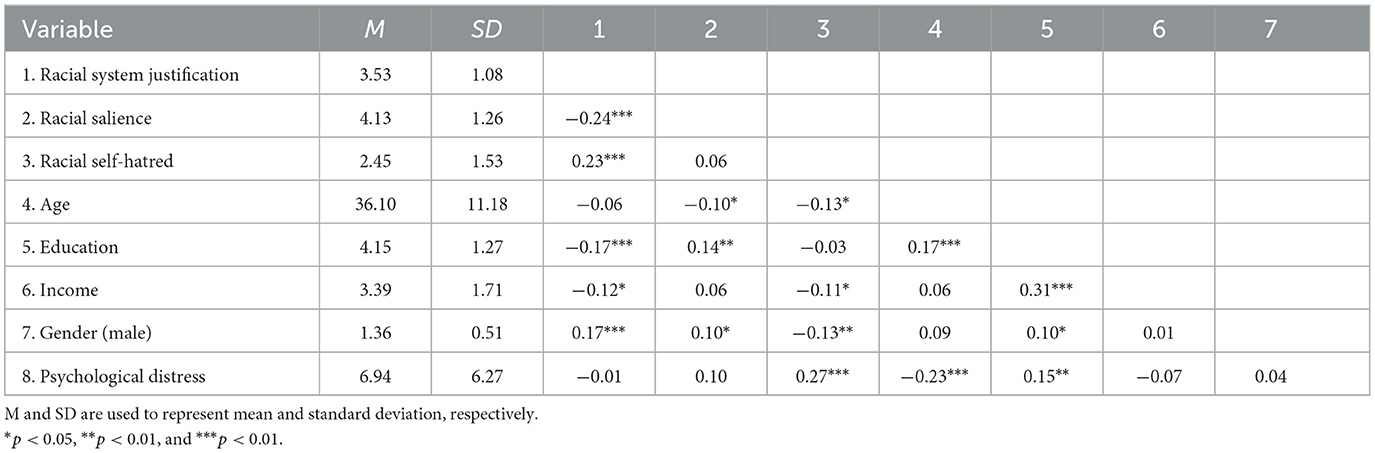

Mediation analyses

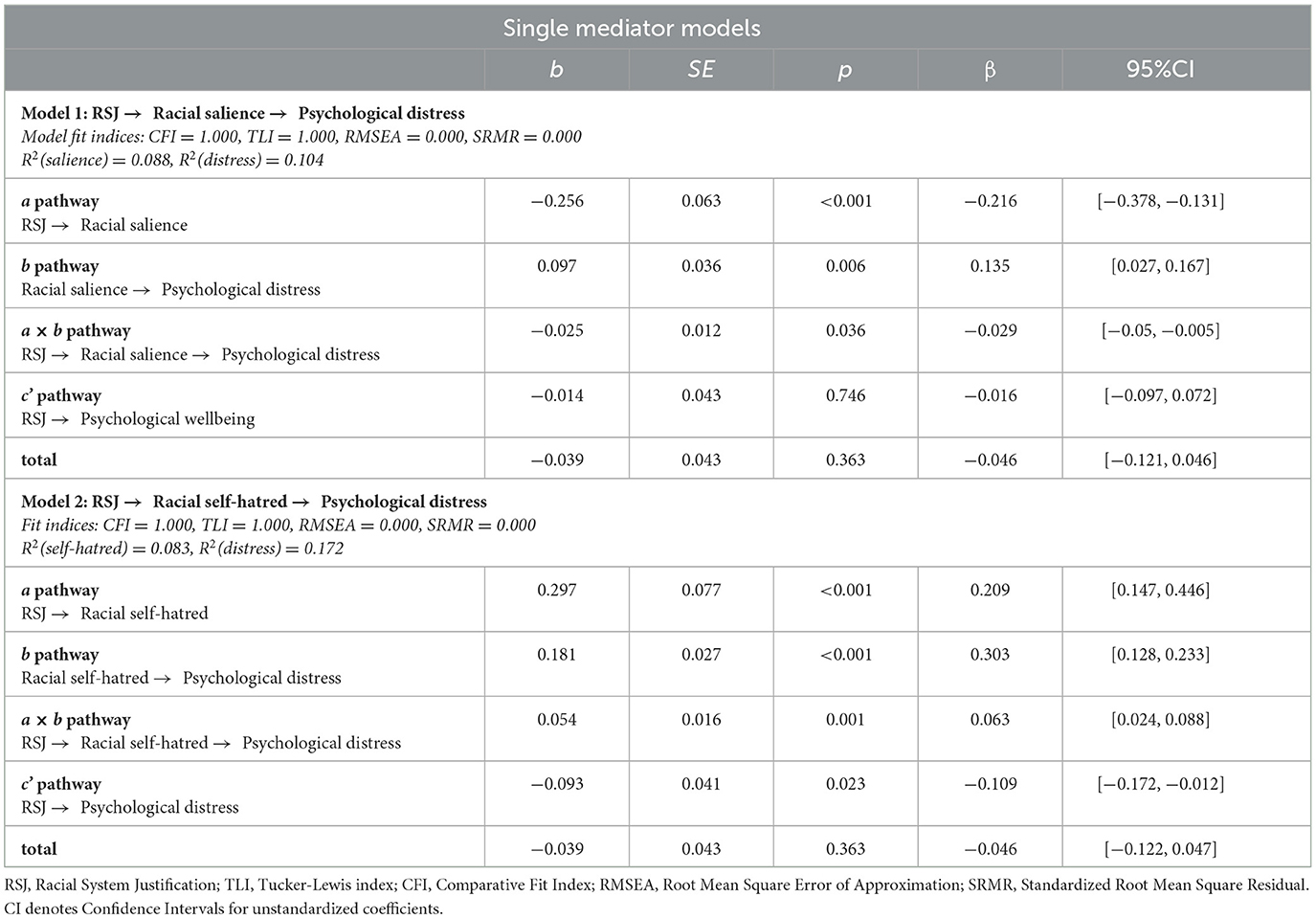

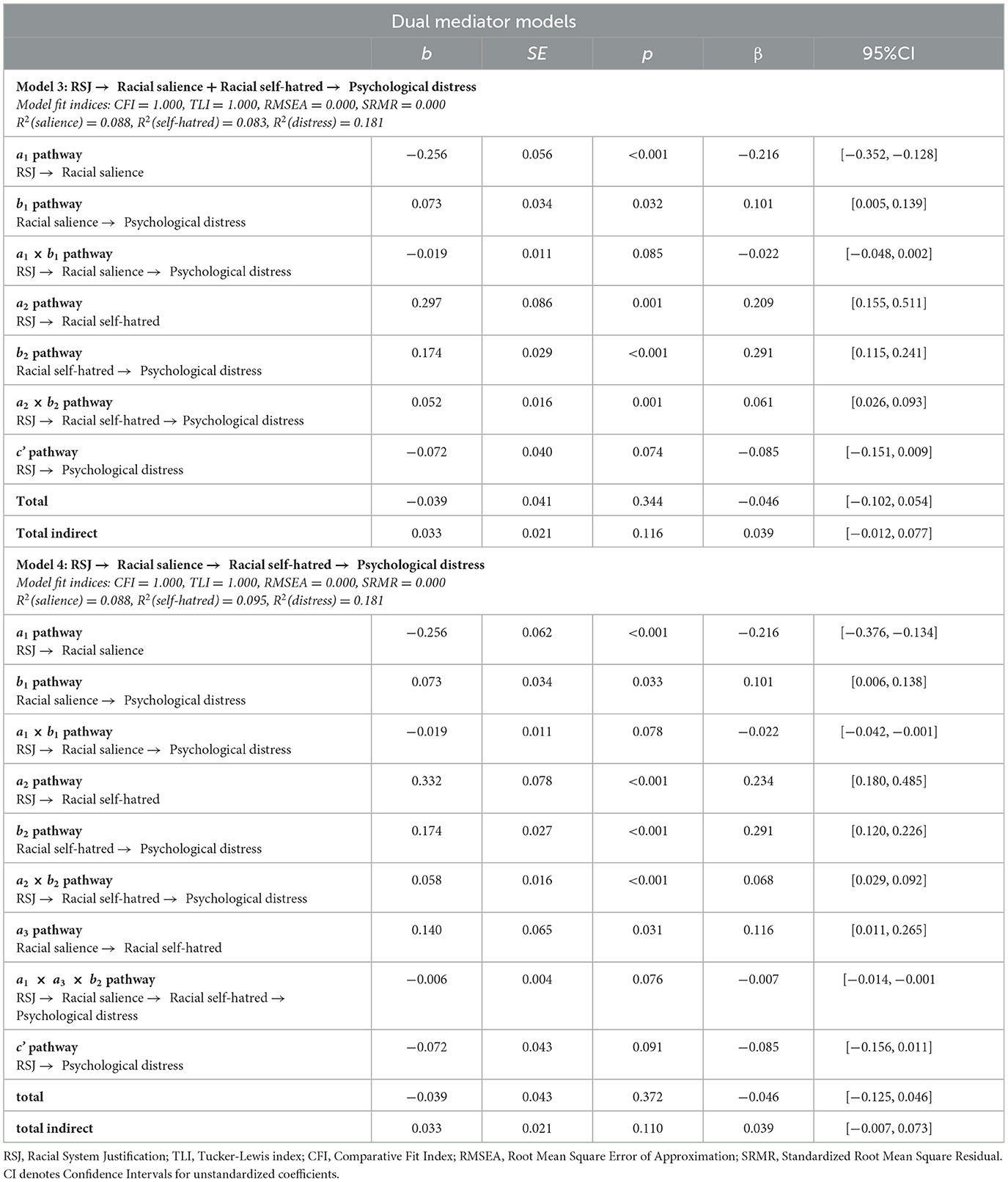

We conducted a series of 3 path analyses with 10,000 bootstrap resamples, estimating a saturated, manifest variable model, adjusting for aforementioned demographic variables. Model fit indices for all models were as expected for a saturated model: χ2, RMSEA, and SRMR values were all 0, and CFI and TLI values were 1. Results from these analyses are summarized in Tables 5, 6.

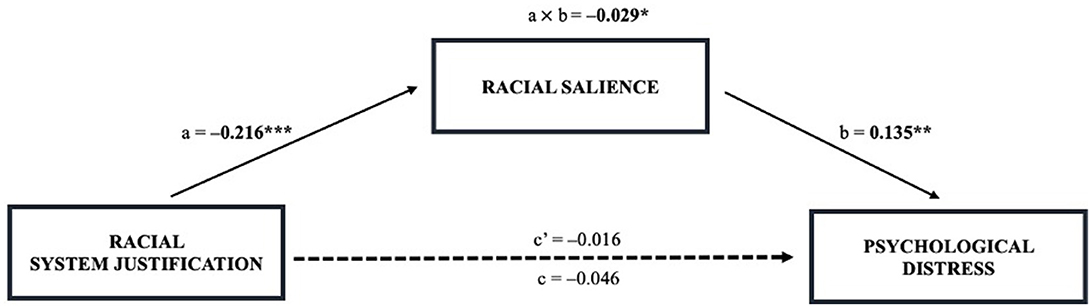

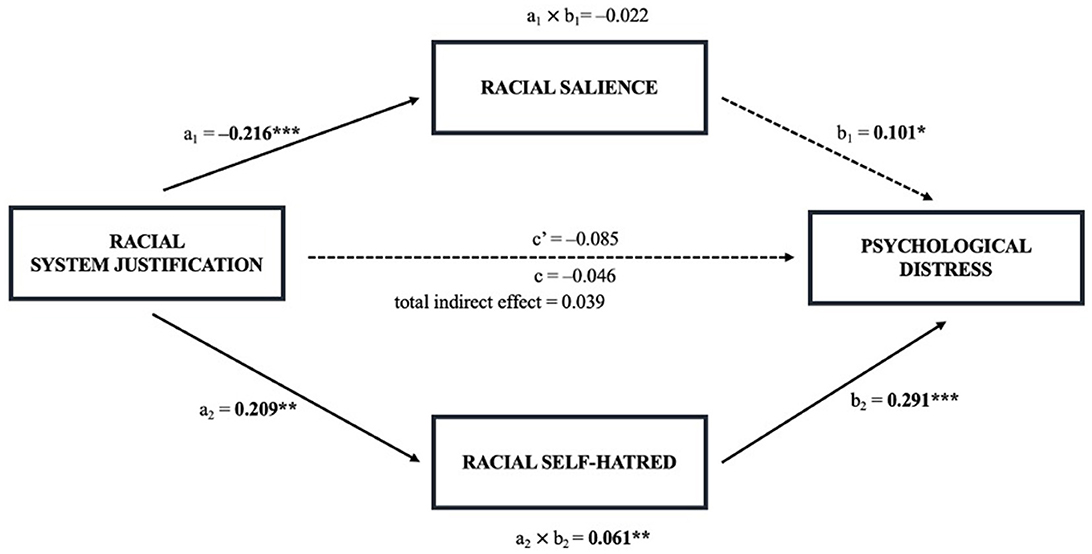

First, we tested two separate single–mediator models to examine whether each mediator individually explained the relationship between RSJ and psychological distress. In model 1, which explained 10.4% of the variance of psychological distress, we examined whether RSJ predicted psychological distress indirectly through salience, finding a negative indirect association (β = −0.029, p = 0.036) (note, though, that this relationship is nonsignificant with the untransformed version of the psychological distress variable: β = −0.019, p = 0.134). The direct relationship between RSJ and psychological distress was not significant (β = −0.016, p = 0.746) (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Path model illustrating the mediation by racial salience of the effects of racial system justification on psychological distress. Numerical values are standardized regression coefficients for the full model. Bolded values indicate significant coefficients (p < 0.05), and broken lines indicate non-significant paths (p >0.05). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

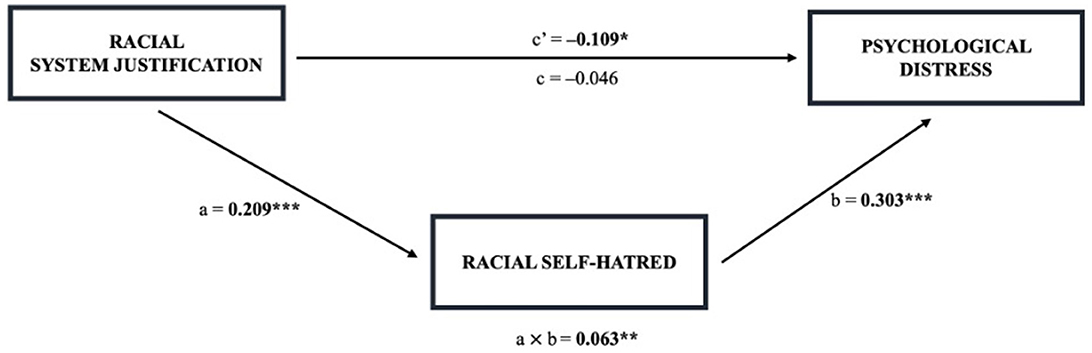

In model 2, which explained 17.2% of the variance of psychological distress, we examined whether RSJ predicted psychological distress indirectly through self-hatred, finding a positive indirect effect (β = 0.063, p = 0.001) and a negative direct effect (β = −0.109, p = 0.023) (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Path model illustrating the mediation by racial self-hatred of the effects of racial system justification on psychological distress. Numerical values are standardized regression coefficients for the full model. Bolded values indicate significant coefficients (p < 0.05), and broken lines indicate non-significant paths (p > 0.05). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

In model 3, as in Study 1, we ran a dual-mediator model to determine whether both mediators still uniquely contribute independent effects when considered together. This model, which explained 18.1% of the variance of psychological distress, produced a negative indirect pathway between racial system justification and psychological distress, through self-hatred (β = 0.061, p = 0.001), while the pathway through salience was no longer statistically significant (β = −0.022, p = 0.085) (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Path model illustrating the mediation by racial salience and self-hatred of the effects of racial system justification on psychological distress. Numerical values are standardized regression coefficients for the full model. Bolded values indicate significant coefficients (p < 0.05), and broken lines indicate non-significant paths (p > 0.05). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Given that the dual-mediator model attenuated the racial salience pathway, suggesting that self-hatred may be absorbing the effect of salience, as in Study 1, we followed up with a serial-mediator analysis to examine potential explanations, namely (1) that the mediating role of salience is part of a sequential process, operating through self-hatred, or; (2) that self-hatred is the stronger pathway for explaining the relationship between RSJ and psychological distress and, given the opposite signs of the two pathways, a confounding effect occurs obscuring the salience pathway. We thus tested a serial-mediator model, which still explained 18.1% of the variance of psychological distress but did not find a significant sequential pathway between RSJ and psychological distress, through salience and self-hatred (β = −0.007, p = 0.08).

Discussion

We hypothesized (H2) that among Black Americans, racial system justification would negatively predict psychological wellbeing, and increased racial self-hatred would mediate the relationship. As such, we expected that (1) racial self-hatred would positively predict psychological distress, and (2) RSJ will positively predict racial self-hatred and, thus, (3) that RSJ would positively and indirectly predict psychological distress through racial self-hatred. Our results supported these predictions. First, though we did not find a significant direct effect of RSJ on psychological distress in our regression analyses, the direct relationships between RSJ and racial self-hatred, and racial self-hatred and psychological distress, were in line with our predictions. Furthermore, in both the single and dual-mediator models, RSJ positively predicted psychological distress through increased racial self-hatred. As such, given the relationships between RSJ, self-hatred, and psychological distress, we find compelling support for our prediction that RSJ would be negatively associated with wellbeing through increased racial self-hatred.

Conversely, in line with our third hypothesis that racial system justification would positively predict psychological wellbeing, and decreased racial salience would mediate the relationship, we expected and found that though racial salience and psychological distress were positively associated in correlational and regression analyses, RSJ negatively predicted racial salience. Further, in our single-mediator model, RSJ negatively and indirectly predicted psychological distress through racial salience. We must note, however, that this statistically significant mediated relationship is eliminated when the psychological distress variable is not log transformed to address linearity and normality violations in the data. This suggests that, though we find evidence of a mediated relationship through racial salience, this relationship is sensitive to the distribution characteristics of psychological distress in our sample.

As such, at least for this sample of Black American participants, we find tentative but inconclusive evidence that racial system justification both positively and negatively predicted psychological distress through its effects on distinct attitudinal components of racial identity, that is, racial salience and self-hatred.

However, when considered together in the dual-mediator model (i.e., when the two mediators are made to “compete” to explain the variance in psychological distress), racial self-hatred seemingly confounded/obscured the mediating role of racial salience, suggesting that, comparatively, racial self-hatred played a larger role in explaining the relationship between racial system justification and psychological distress. Interestingly, however, in the dual mediator model, while the negative racial salience pathway lost significance, a direct, negative relationship between RSJ and psychological distress emerged. This suggests that, while the palliative RSJ–wellbeing association through racial salience may be overshadowed by its pernicious effects through self-hatred, there may still be a palliative effect of RSJ that persists alongside its pernicious effects, reflected by its direct association with wellbeing or its relationship with wellbeing through another mediator that we did not consider in this study.

General discussion

In the present research, we examined the association between racial system attitudes and psychological wellbeing in groups that are advantaged and disadvantaged by the American racial status quo. Importantly, we introduced a new measure of system justification that captures attitudes toward the racial system. While it would be useful to assess justification of the system as a whole, homing in on attitudes about the racial status quo in particular allows us to better capture whether and how appraisals of the racial system predict psychological wellbeing.

Divergence and convergence in the racially privileged and racially oppressed

In this paper we interrogated the relationship between system justification and psychological wellbeing for privileged and disadvantaged racial group members, accounting both for potential divergence and convergence. We hypothesized, first, that justification of the racial system would predict psychological wellbeing in members of a racially privileged group. We therefore predicted that our measure of racial system justification would positively predict (good) mental health in a sample of White participants residing in the U.S., further hypothesizing that decreased ethnic-racial salience and ethnic-racial self-hatred, two attitudinal components of racial identity (Worrell et al., 2019), would mediate this relationship (H1).

As expected, racial system justification predicted psychological wellbeing through racial salience and racial self-hatred for racially privileged group members, as evidenced by the significant positive indirect association between racial system justification and the likelihood of reporting zero bad mental health days through our two mediators. This pattern of results reiterates traditional SJT conceptualizations and corroborates the existing empirical evidence that privileged groups benefit psychologically from justifying the system that privileges them (Jost and Thompson, 2000). We reasoned that it may do so by making the source of their privilege—i.e., their race—a less salient feature of everyday life, allowing them to enjoy the psychological benefits of the status quo unencumbered by guilt or self-doubt, as has been illustrated among other high-status groups (e.g., high SES; Wakslak et al., 2007). Not only did our findings support our hypothesis that RSJ would positively predict psychological wellbeing through its association with both racial salience and racial self-hatred, we found further evidence of this reasoning via a non-hypothesized serial pathway wherein racial system justification positively and indirectly predicted psychological wellbeing by first predicting salience, which in turn predicted racial self-hatred, and then psychological wellbeing. These results suggest that racial salience and racial self-hatred do indeed operate together to explain the psychological benefits of racial system justification for White Americans.

The results of the present research also paint a complex picture regarding the relationship between system justification and psychological wellbeing for Black Americans—a racially oppressed group under the racialized U.S. American social system. Our analyses revealed that the relationship between RSJ and psychological distress was mediated by increased racial self-hatred, in line with Hypothesis 2. Yet it also tentatively revealed a significant (though inconclusive) mediated negative relationship between racial system justification and psychological distress through racial salience in line with Hypothesis 3, but contrary to SJT's traditional conceptualization, which postulates only a detrimental relationship between system justification and psychological wellbeing for disadvantaged groups (Postulate VII; Jost and van der Toorn, 2012). Interestingly there was no direct or total effect of racial system justification on psychological distress in both our regression and mediation analyses. As such, the possibility that RSJ may have simultaneous positive and negative, palliative, and pernicious associations with wellbeing was made clear only via considering the mediating mechanisms of racial identity attitudes. This finding highlights the significance of considering racial identity-attitudes in conjunction with system justification to fully appreciate the consequences of system justification for psychological wellbeing in the context of a racially inegalitarian status quo.

In examining system justification and identity together, we aimed to accomplish a few goals. First, we considered system justification and identity-related factors concurrently as psychological processes that not only coexist but may be associated with each other. This departs from how these two attitudinal and motivational processes are often treated in social psychological research. Habitually, system justification and group or identity-related psychological motives are treated as independent forces (Jost and Banaji, 1994; Jost et al., 2003b). Thus, few researchers have considered how identity-related motives and attitudes might intervene in shaping psychological wellbeing as people make sense of inegalitarian or oppressive systems (e.g., O'Brien and Major, 2005). In this research, we go even further by positioning system justification's beneficial or harmful association with psychological wellbeing as operating through its association with racial identity, rather than positioning the two as independent of each other.

Secondly, our approach helps to account for discrepancies in the literature on the palliative, positive, and negative effects of system justification on wellbeing. Specifically, the simultaneous positive and negative associations between racial system justification and wellbeing for racially oppressed groups via different attitudinal components of racial identity may both (1) account for the absence of any direct positive effects of system justification on wellbeing in our present study and more broadly (2) reconcile the mixed empirical evidence in the literature that show the effects of SJ on wellbeing diverge based on group-status (Jost and Thompson, 2000) but also occasionally converge (O'Brien and Major, 2005; Vargas-Salfate et al., 2018). We also conceptually reconcile the traditional SJT postulates that speaks to the effects of system justification on long-term wellbeing and the palliative effects on affect, particularly for disadvantaged groups. SJT postulated that system justification will have a positive, palliative effect on affect (Postulate VIII) but a negative effect on psychological wellbeing (Postulate VII) for disadvantaged groups. Our Study 2 results indicate that system justification may show both positive and negative associations with psychological wellbeing, suggesting that the palliative effects may extend beyond affect. We think this makes sense, considering that affect is linked to and predictive of mental health and wellbeing (Khazanov and Ruscio, 2016; Mehrabian, 1997).

Limitations

Despite the promising evidence, we must acknowledge methodological limitations of our research. First, our outcome measures varied across White and Black samples. While both outcome variables measured poor psychological wellbeing, they differed considerably in terms of content, the number of scale items, and response-range. Identical outcome variables across the two studies would have allowed for a clearer one-to-one comparison. Nonetheless, both variables capture psychological distress—and specifically depressive symptoms—which allowed us to test our hypotheses about the effects of system justification for each group.

Secondly, our studies were not pre-registered. While we aimed for a theoretically driven approach, the absence of preregistration means that our findings should be interpreted with caution, particularly in terms of potential researcher degrees of freedom.

Thirdly, our data did not include any personality measures which would permit us to differentiate aspects of racial identity from non-racialized aspects of personality. For instance, racial self-hatred corresponds positively with all nine subscales of the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, 1993; Worrell et al., 2011), so including a measure of neuroticism, which likely covaries with racial self-hatred, would have allowed us to ascertain the degree to which racial self-hatred explains the relationship between racial system justification and wellbeing after statistically removing the effects of neuroticism and self-loathing for non-racial reasons.

Finally, we tested our hypotheses using correlational data. Although, we reasoned that system justification affects racial salience and racial self-hatred which in turn affects wellbeing, we cannot rule out that the direction of the relationship is reversed. It is reasonable to consider, for example, that individuals whose racial identity is characterized by greater degree of salience of race in their everyday life may be more or less inclined toward justifying the racial system—potentially, because they may be more attentive to the role race plays in the broader societal system and thus may be more likely to reason about the system. In other words, racial identity attitudes could be antecedents, rather than consequences, of racial system justification. Thus, experimental approaches which prime either attitude components of identity and/or racial system justification can further clarify the nature and direction of the relationship between the two and establish their downstream effects on psychological wellbeing.

Future directions

One important future direction of this research would be to examine the direct and indirect effects of racial system justification and identity-attitudes for intermediate status groups, such as Asian Americans (Oyserman and Sakamoto, 1997; Shiao, 2017; Yancey, 2003). For instance, within the U.S. American racialized system, Asian Americans are simultaneously derogated on the basis of perceived foreignness, and granted relatively high status (Zou and Cheryan, 2017), and so the attitude dimensions of identity may operate differently than they do for White and Black Americans (Junn and Masuoka, 2008; Worrell et al., 2020).

Another goal for future research involves reconciling the mechanistic contributions of ethnic-racial identity and perceptions of racial discrimination in understanding the relationship between system justification and wellbeing. Emerging research suggests that system justification exerts a positive effect on wellbeing for low-status or disadvantaged ethnic, gender, and sexual minorities, in part, via reduced perceptions of discrimination (Bahamondes et al., 2019; Suppes et al., 2019). While our Study 2 data did happen to include a measure of perceived discrimination (i.e., the Schedule of Racist Events; Landrine and Klonoff, 1996), we opted against analyzing this data to ensure parallel analyses across samples, as we had no measure of perceived discrimination for the White participants in Study 1. Thus, we welcome research employing measures of ethnic-racial identity and perceived discrimination, along with measures of racial system justification and subjective wellbeing, which can simultaneously examine identity attitudes and perceptions of discrimination as potential mediators of the SJ—wellbeing association for both racially advantaged and disadvantaged groups.

Future research may also benefit from examination of the relationship between other systems justifying beliefs, such as political conservatism, and racial identity attitudes, and wellbeing, which we do not explore here as we were primarily concerned with RSJ as a distinct construct, rather than broader ideological self-identification. In the present research we conducted supplementary analyses including political orientation as a covariate in our mediation models. However, given existing debate and mixed evidence in the literature regarding overlap between political conservatism and racial attitudes (e.g., Hutchings and Valentino, 2004; Sears and Henry, 2003; Smith, 2010; Wallsten et al., 2017), exploring the role political orientation may play in racial identity attitudes and wellbeing—above and beyond racial system attitudes—would be a fruitful direction for future research.7

Another viable path for future research involves exploring alternative conceptualizations of racial identity. Both the CERIS-A (Worrell et al., 2019) and CRIS (Vandiver et al., 2002) rely on Cross' Nigrescence theory (Cross and Vandiver, 2001). One well-known alternative to Nigrescence theory is the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI; Sellers et al., 1998) and its associated scale, the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI; Sellers et al., 1997) which conceptualizes four dimensions of racial identity: centrality, ideology, regard, and salience. Though the MIBI and CRIS share overlap in content, they also differ considerably. For example, the MIBI's centrality scale measures the degree to which people define themselves with respect to race and may be closer to the traditional strength of identification measures employed in social identity research. Notably, the MMRI theorized a salience dimension (i.e., as distinct from centrality) but did not operationalize it. In the present research, salience positively predicted psychological stress, though prior research using the MIBI found that racial centrality negatively predicted psychological distress, or buffered against it (Sellers et al., 2003). Thus, future research would benefit from examining the mediating role of racial centrality in the RSJ—wellbeing association.

Finally, the extent to which identity-related attitudes intervene in explaining the relationship between system justification and psychological wellbeing merits investigation in additional intergroup and economic/social contexts. First, our research is contextualized within the American social system, and so it remains an open question whether similar patterns of diverging and converging associations between racial system justification and wellbeing for advantaged vs. disadvantaged groups would emerge in other societies with similarities and differences in their racial and ethnic hierarchies (e.g., Caribbean, South African, or Indian contexts; Alleyne, 2002; Khalfani and Zuberi, 2001). Secondly, social theorists have pointed to a number of dimensions of inequality and hierarchy within the U.S. American system (Bonilla-Silva, 1997), highlighting its racialized, gendered, heterosexist, and capitalist nature (Bohrer, 2019; Lugones, 2007). Existing research has already demonstrated that self-hatred or internalized homonegativity mediates a negative relationship between system justification and psychological wellbeing for gay men. (Bahamondes-Correa, 2016). These parallels may reflect the fact that both the racialized and heteronormative aspects of the American social system have bearing upon identity. They each create socially relevant categories (i.e., on the basis of race or sexuality; Omi and Winant, 2014; Weststrate and McLean, 2010), while also proffering hegemonic ideas about groups that may shape the attitudes individuals have toward their own identity (Herek et al., 2009). Given the significance of gender for identity and the status-differences created by a sexist institutional and cultural context, a consideration of how gender system justification shapes identity attitudes may augment our understanding of its effects on wellbeing for privileged and disadvantaged genders, contributing to existing research on gender system justification and psychological wellbeing (Napier et al., 2020). However, other dimensions of inequality within the racialized social system (e.g., capitalism) which do not historically rely on group categorization, may thus bear less on identity, resulting in more convergence in the effects of system justification on wellbeing (Vargas-Salfate et al., 2018).

Concluding remarks

In this research we interrogated the relationship between racial system justification and psychological wellbeing for racial actors under the system of racism. Our results suggest that, for privileged groups, justifying the racialized system is associated with psychological benefits, explained in part by how those system attitudes shape identity attitudes. For disadvantaged groups, racial system justifying attitudes are associated with either detrimental or beneficial psychological consequences, depending on how those system attitudes shape identity attitudes. By considering identity in conjunction with system justification, our research points to and helps explain the diverging and converging effects of system justification for wellbeing for the privileged and oppressed, while clarifying the potential mechanisms through which system justification may have its palliative and pernicious effects. Beyond its theoretical contributions, our study elucidates the connection between system attitudes, racial identity, and psychological health. This insight deepens our understanding of how inegalitarian and hierarchical systems influence the psychological experiences of the people within them.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Long Island University-Brooklyn Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. BS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2025.1525321/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^As with other postcolonial societies in the Americas and across the globe.

2. ^The Nigrescence theory (NT) was originally formulated as a developmental stage model describing how Black Americans came to identify with Blackness (Cross, 1971), but was later expanded and reconceptualized as an attitudinal model (NT-E; Cross and Vandiver, 2001).

3. ^While we focus primarily on psychological distress in this study, we also explored hypotheses about the mediated relationship between racial system justification and positive and negative affect for Black American participants, in an application and extension of SJT's palliative hypothesis. We report and discuss these analyses in the Supplementary material.

4. ^We acknowledge pre-emptively the limitations in a single-item count variable as Study 1's primary outcome measure. We nonetheless used it as a crude proxy for psychological wellbeing to test our hypothesis.

5. ^We excluded political orientation due to its likely conceptual overlap with racial system justification (Jost et al., 2003a; Sears and Henry, 2003), our primary predictor of interest. We report mediation analyses including political orientation as a covariate in the Supplementary material.

6. ^We also ran the linear regression and mediation analyses with the untransformed version of the psychological distress variable, which are reported in the Supplementary material. With the exception of one relationship, results were largely the same, with slight differences in effect size, but no changes to statistical significance. However, results were not the same for the model examining the mediated relationship between racial system justification and psychological distress through racial salience, which we elaborate on in the main text.

References

Alexander, M. (2012). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press.

Alleyne, M. C. (2002). The Construction and Representation of Race and Ethnicity in the Caribbean and the World. University of the West Indies Press.

Azevedo, F., Jost, J. T., and Rothmund, T. (2017). “Making America great again”: System justification in the US presidential election of 2016. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 3:231. doi: 10.1037/tps0000122

Bahamondes, J., Sibley, C. G., and Osborne, D. (2019). “We look (and feel) better through system-justifying lenses”: system-justifying beliefs attenuate the wellbeing gap between the advantaged and disadvantaged by reducing perceptions of discrimination. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 45, 1391–1408. doi: 10.1177/0146167219829178

Bahamondes-Correa, J. (2016). System justification's opposite effects on psychological wellbeing: testing a moderated mediation model in a gay men and lesbian sample in Chile. J. Homosex. 63, 1537–1555. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1223351