- Department of Psychology, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, United States

Introduction: The purpose of this study was to observe how accurate Black and White perceivers were in detecting White targets' anti-Black attitudes, the non-verbal cues that were related to targets' anti-Black attitudes, and the cues that were related to perceivers' judgments of targets' anti-Black attitudes.

Method: White targets (N = 61) engaged in an interracial interview and completed a self-report measure of anti-Black attitudes. We recruited Black perceivers (N = 114) and White perceivers (N = 108) through Prolific who watched 30 second, silent clips of targets and inferred each targets' anti-Black attitudes. Research assistants coded the clips for various non-verbal behaviors (e.g., smiling) and impressions (e.g., positivity, anger).

Results: Black and White perceivers were able to accurately (above chance) detect targets' anti-Black attitudes. Targets' anti-Black attitudes were significantly and positively related to coded target anger during the interracial interaction. Similarly, Black and White perceivers' judgments of targets' anti-Black attitudes were significantly and positively related to coded target anger. Several other non-verbal behaviors generally reflecting less positive feelings and impressions were also related to perceivers' judgments of higher anti-Black attitudes. Relationships between targets' self-reported attitudes and non-verbal cues, as well as the relationships between perceiver judgments of attitudes and non-verbal cues, were largely only significant when targets were interviewing with a Black woman and not a Black man. Lastly, Black and White perceivers were more accurate in detecting targets' anti-Black attitudes when the target was interviewing with a Black woman, compared to a Black man.

Discussion: Implications for identifying anti-Black attitudes in workplace settings are discussed.

Introduction

Experiencing repeated discrimination has dire consequences for Black Americans. The majority of Black professionals have experienced racial prejudice at work, a rate that is nearly four times higher than that of White professionals (58% vs. 15%, respectively; Coqual, 2019). As a result, over a third (35%) of Black professionals plan on leaving their jobs within 2 years (Coqual, 2019). This presents a systemic problem; social mobility and economic opportunities are greatly hindered as a result of Black individuals not feeling welcome at work. However, the factors that lead a person to accurately detect anti-Black attitudes are unclear. Detecting anti-Black attitudes is functionally important because one would want to detect potential threats in the environment by hiring more egalitarian employees and selecting friends that are low in negative attitudes of Black individuals (Becker et al., 2011; Zebrowitz and Collins, 1997). Even though anti-Black attitudes can be inferred from salient cues in the environment, these explicit signs are not necessarily always present.

From here on out, the person whose attitudes are being judged is referred to as a “target,” and the one who is inferring the target's attitudes is referred to as a “perceiver.” The purpose of this study is to understand the non-verbal behaviors that a person (i.e., target) may display toward a Black interaction partner that are, (1) related to their anti-Black attitudes, and (2) influence a perceiver's perceptions of the target's anti-Black attitudes in a videoconferencing setting. Additionally, we aimed to test the accuracy of perceivers in inferring targets' anti-Black attitudes from only their non-verbal behaviors. Once we understand the cues that are related to anti-Black attitudes and how perceivers are influenced by such cues in their judgments, a skills-based decoding training could be created to enhance perceivers' skills in the detection of anti-Black attitudes and paired with a bystander intervention training to increase effective confrontation of anti-Black attitudes (Monteith et al., 2019). Lastly, we examined how the Black interaction partner's gender influenced targets' anti-Black behaviors and perceiver judgments of targets' behaviors.

Interpersonal accuracy of attitudes

Perceivers can glean a wealth of information from short excerpts, including information about another person's personality, traits, and emotions in a very short amount of time and with only access to non-verbal behaviors (Ambady and Rosenthal, 1992; Murphy and Hall, 2021). For instance, Rollman (1978) found that perceivers were able to judge racism in targets within five minutes. The degree to which judgments about others are correct is referred to as interpersonal accuracy. One domain of accuracy is the judgment of another's beliefs and attitudes (e.g., Goh et al., 2017; Paunonen and Kam, 2014; Richeson and Shelton, 2005; Rollman, 1978). Past research suggests that attitudes and beliefs are more difficult to judge in a person than other domains that have more observable and salient behaviors (e.g., crying to indicate sadness; Paunonen and Kam, 2014).

A lens model approach to anti-Black attitudes

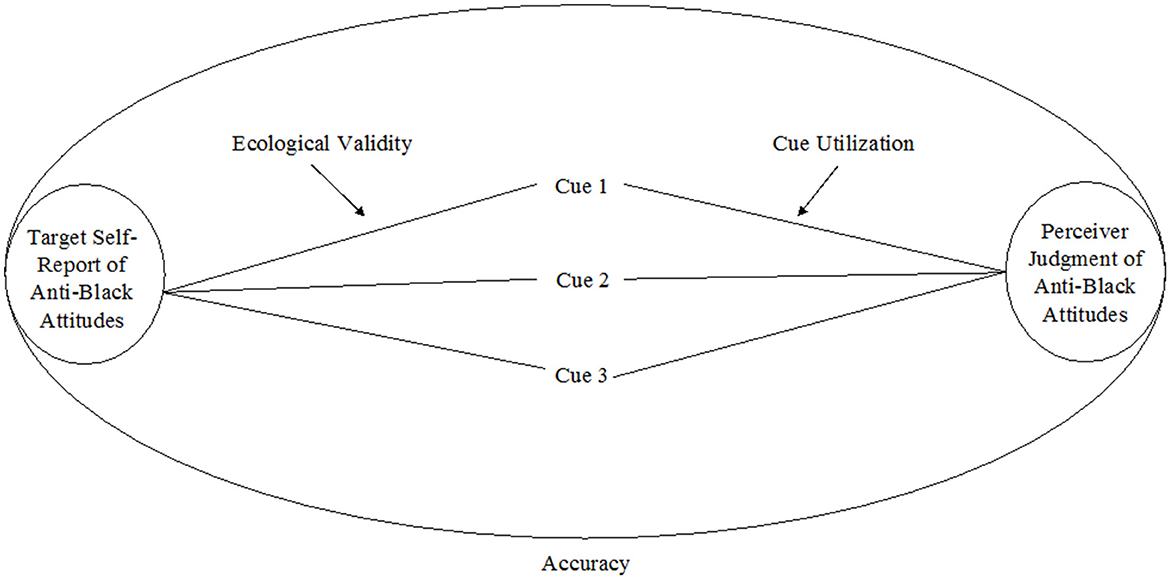

Brunswik's (1952) lens model is a framework for understanding how people make judgments about others when they cannot directly observe a psychological phenomenon (e.g., Bernieri et al., 1996; Ruben and Hall, 2016). Judgments are formed through cues or observable signals in the environment that stand in for the criterion (i.e., psychological phenomena of interest). For example, when evaluating a physician's empathy, listeners may rely on cues such as tone of voice, eye contact, or word choice. The lens model emphasizes (1) ecological validity, or how well each cue relates to the criterion (e.g., whether smiling genuinely reflects empathy) and (2) cue utilization, or the degree to which an observer relies on that cue when forming a judgment. Accuracy arises when cue utilization aligns with cue validity, but systematic errors occur when reliance falls on unreliable or invalid cues. It is named the “lens” model because it describes the process of how individuals piece together probabilistic cues from the environment, similar to how a lens filters and focuses light.

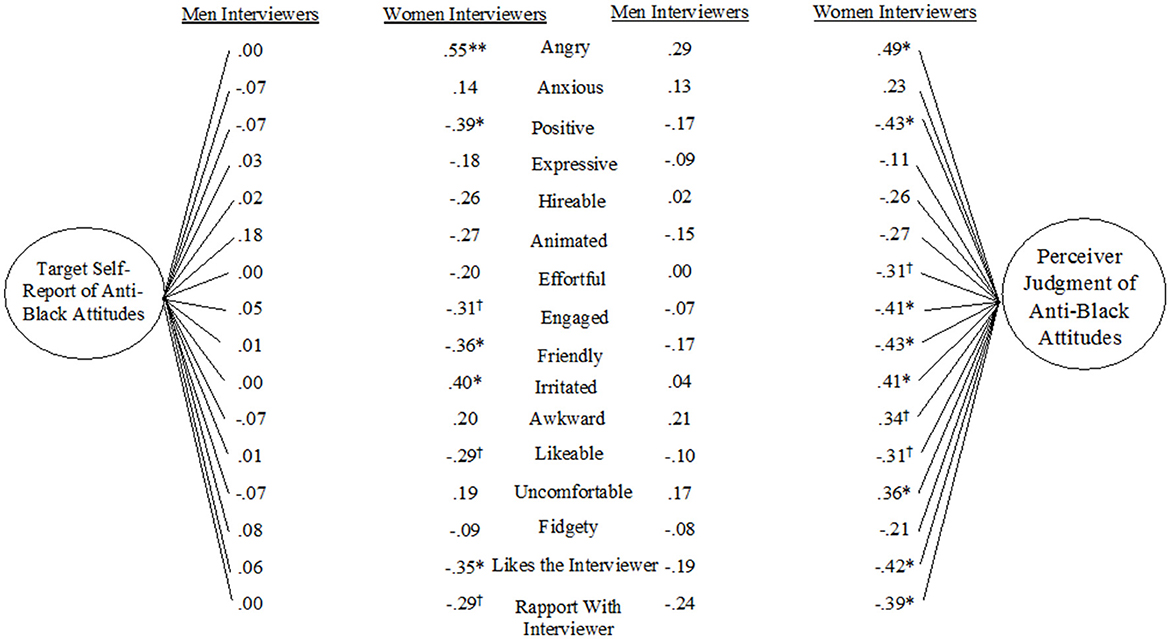

In the context of perceiving a target's attitudes, the lens model can be employed to assess a perceiver's use of cues (or behaviors) in determining a target's level of anti-Black attitudes, cues related to anti-Black attitudes, and a perceiver's accuracy in judging a target's anti-Black attitudes (Figure 1). The degree to which certain cues are present when perceivers infer targets have higher anti-Black attitudes is denoted by the cue utilization side of the lens. The ecological validity side of the lens model indicates the extent to which higher self-reported anti-Black attitudes of the targets are related to specific non-verbal cues observed in the middle of the lens. Perceivers display higher accuracy when their ratings of the targets' attitudes are positively correlated at above chance levels with the targets' self-reported attitudes– suggesting that perceivers can accurately discriminate higher from lower levels of anti-Black attitudes.

Figure 1. Lens model of anti-Black attitudes. The lines connecting each cue to target self-report of anti-Black attitudes and perceiver judgment of anti-Black attitudes represent hypothetical correlations.

Ecological validity: cues correlated with targets' anti-Black attitudes

Since explicitly expressing anti-Black attitudes is not socially acceptable in a modern society, bias against Black individuals may manifest in a more subtle fashion (Carter and Murphy, 2015; Dovidio et al., 1997, 2002; McConahay, 1986). It may be the case that in-group favoritism, more broadly, can be observed through non-verbal behavior. For example, Mackinnon et al. (2011) found that individuals who were alike in physical characteristics (glasses-wearing, hair length/color, race, and gender) chose, or indicated that they would choose, to sit closer together.

When utilizing a lens model framework, one must understand what non-verbal cues could plausibly have a relationship with anti-Black attitudes, or negative attitudes about an outgroup member. It is possible that negative attitudes about an outgroup member may be expressed through lower levels of non-verbal involvement, a set of behaviors that describe the degree of involvement manifested between people in a social interaction (Patterson, 1982, 1983). Less non-verbal involvement in interracial interactions may signal less liking, interest, or commitment to one's interaction partner (Patterson, 1982). Lower expressed non-verbal involvement may manifest in interracial interactions as (1) less smiling, (2) less gaze toward the others' eyes, (3) less head nodding, (4) less hand gesturing (5) more body orientation away, and (6) more movement away from one's conversational partner.

Past studies or theories support that these cues (i.e., less non-verbal involvement) may be related to White targets' anti-Black attitudes in the context of an interracial interaction. In previous studies, targets higher in anti-Black attitudes smiled less and made less eye contact (or gazed less) during an interaction with a Black individual than those lower in anti-Black attitudes (Dovidio et al., 1997; Willard et al., 2015).

Though there are no studies to our knowledge that assessed the relationship between gesturing and anti-Black attitudes, there may be reason to believe that less gesturing is related to higher anti-Black attitudes. Gesturing is related to effort in understanding and making a good impression, so when targets gesture less in an interracial interaction, they might be exhibiting less care or attentiveness for the interaction, and therefore hold higher anti-Black attitudes (Patterson, 1982; Walkington et al., 2019).

Though one study has coded behaviors similar to body orientation and movement toward a Black conversation partner (McConnell and Leibold, 2001), no studies to our knowledge coded these behaviors precisely in an interracial interaction and related them to White targets' implicit or explicit anti-Black attitudes. Non-verbal involvement behaviors such as moving toward and orienting one's body toward an interaction partner reflect “approach” behaviors or behaviors that indicate interest or liking of one's conversation partner (Chen and Bargh, 1999). If a White target displays few approach behaviors toward a Black conversation partner, this might indicate that they hold higher anti-Black attitudes.

While the absence of non-verbal involvement may reflect higher anti-Black attitudes, it is also plausible that there may be observable signs of negative affect or arousal that relate to anti-Black attitudes. For example, impressions of anger are associated with more negative emotional arousal and thus may reflect higher anti-Black attitudes (Burgoon et al., 1989). Additionally, excessive blinking might be related to higher anti-Black attitudes due to its link with negative arousal states and tension (Exline, 1985). For example, Dovidio et al. (1997) found that White people who excessively blinked during an interaction with a Black individual had higher anti-Black attitudes than those who blinked less.

Past studies show that different non-verbal and verbal cues may be related to anti-Black attitudes depending on whether explicit or implicit attitudes are measured. Explicit attitudes are those that are consciously and declaredly stated. However, researchers increasingly focus on implicit attitude measures, especially in the racial context. Among the most popular implicit measures are those intended to capture individuals' speed of categorizing White and Black faces/stimuli with valanced words (Gaertner and McLaughlin, 1983; Greenwald et al., 1998). Biased scores on implicit racism measures were sometimes more predictive of non-verbal behavior in interracial interactions than explicit measures. For example, Dovidio et al. (2002) found that White peoples' explicitly reported anti-Black attitudes predicted verbal bias toward a Black conversation partner but was not a predictor of non-verbal friendliness. White peoples' implicit bias was related to coder ratings of the White participants' non-verbal friendliness such that more biased scores on the response latency measure predicted less non-verbal friendliness to the Black conversation partner than a White partner (Dovidio et al., 2002). In addition, McConnell and Leibold (2001) found that participants' more biased scores on a version of the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald et al., 1998) predicted the degree to which they smiled more at and talked longer to a White experimenter vs. a Black experimenter, but participants' scores on explicit anti-Black attitude measures were not significantly related to these cues. However, the significant results initially presented in McConnell and Leibold's original work did not hold when reanalyzed by a separate research team (Blanton et al., 2009).

Even though implicit attitude measures were shown to be stronger predictors of non-verbal behavior than explicit attitude measures, there is still a need to understand what non-verbal behaviors are related to explicit measures as the current political climate has shifted since these former studies were done more than 20 years ago. Negative explicit attitudes may not be that uncommon given the current political climate and tolerance of extremism. There was a 49% increase in hate crimes against Black/African Americans from the year 2019 and 2020, according to the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2021). Additionally, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) Center on Extremism reported a 38% increase in White supremacist propaganda efforts from 2021 to 2022 (i.e., the distribution of racist/anti-semitic/anti-LGBTQ+ materials; Anti-Defamation League Center on Extremism, 2023). Given these recent events, explicit endorsements of and observable behaviors related to anti-Black attitudes might not be that uncommon.

Past literature also shows that explicit attitude measures do predict observable behaviors. In a meta-analysis, Cameron et al. (2012) found that, across 38 studies, more biased scores on explicit measures predicted more prejudiced behaviors (r = 0.25). Importantly, the predictive power of explicit measures did not significantly differ from the predictive power of implicit measures (Cameron et al., 2012). Additionally, among other types of prejudice, there is support for explicit attitudes being related to observable non-verbal behaviors (Goh and Hall, 2015). Goh and Hall (2015) found that men higher in explicitly-reported hostile sexism compared to those lower exhibited less affiliative behaviors (e.g., seemed not approachable) and men higher in explicitly-reported benevolent sexism compared to those lower exhibited more affiliative behaviors (e.g., seemed approachable). However, there is a lack of research on the relationship between explicit racial attitudes and non-verbal behavior, especially more recently (Dovidio et al., 1997; McConnell and Leibold, 2001). Regardless of the type of measure used as the criterion for anti-Black attitudes (implicit vs. explicit), it is common for ecological validity correlations to be weaker than cue utilization correlations, highlighting that non-verbal manifestations of internal states such as attitudes may appear in subtle but insidious ways (Gosling et al., 2002; Hartwig and Bond, 2011).

Cue utilization: non-verbal cues correlated with perceived anti-Black attitudes

The cue utilization side of the lens model is the process by which perceivers make judgments based on the cues available to them when inferring targets' anti-Black attitudes. Past work on cue utilization of racial prejudice has predominantly focused on stable characteristics such as facial features (e.g., face-width-to-height ratio; Hehman et al., 2013) or gender (e.g., Ifatunji and Harnois, 2016) as cues rather than more behavioral or modifiable manifestations of prejudice. For example, Hehman et al. (2013) found that perceivers judged men with a higher face-width-to-height ratio (FWHR) to be more anti-Black than those with a lower FWHR. Though gender dynamics and facial cues are important in understanding Black and White perceivers' judgments of anti-Black attitudes, the literature on the relationship between dynamic non-verbal cues such as non-verbal involvement behaviors and prejudice is lacking (as opposed to more stable cues like facial structure).

Approaches to perceiving anti-Black attitudes might differ according to the perceiver's race. For example, in a study by (Rollman 1978), participants self-reported the parts of the body which they felt strongly influenced their perception of a target's prejudicial attitudes. Black participants reported a more localized approach to detecting prejudice (focusing on specific parts of the body), while White participants differed in that they reported a more global approach (focusing on the whole body). Participants also reported that they relied on the degree to which the White target was tense or relaxed in an interaction with a Black person and used that information to infer the target's prejudicial attitudes. However, participants may not be able to accurately report which cues they relied on to make their judgments. Nisbett and Wilson (1977) argued that the typical person does not have immediate awareness of the higher-order cognitive processes underlying their decisions and judgments. Therefore, in the present study, the “cue utilization” side of the lens will indirectly serve as the degree to which certain non-verbal cues were present (or had more intense cues) in a target when the perceiver inferred higher or lower anti-Black attitudes. This does not require participants to explicitly report the non-verbal cues that they utilized to make their impression.

Accuracy: perceivers' abilities to detect targets' anti-Black attitudes

Past work suggests that perceivers can accurately infer the prejudiced attitudes of others (Goh et al., 2017; Richeson and Shelton, 2005; Rollman, 1978; West, 2016). For example, Hehman et al. (2013) found that perceivers' evaluations of targets' prejudice (based on static photographs) were significantly related to targets' explicit reports of racial prejudice. However, this may depend on characteristics of the perceiver and their position in society including whether they have experienced prejudice or systemic marginalization. Richeson and Shelton (2005) found that Black people were better able to infer a White target's scores of racial bias on a response-latency measure, the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald et al., 1998), with greater precision than White people when watching 20-s silent videos of the target. In addition, Rollman (1978) found that Black individuals could discriminate between high-prejudice individuals and low-prejudice individuals better than White individuals. These researchers argue that Black perceivers might be particularly motivated to accurately detect White targets' racial attitudes given the benefits in managing complex social dynamics and safety. This may also be true in situations where limited information about White targets is available and explicit statements about their racial attitudes are not expressed nor available to perceivers. Due to the historical marginalization of Black individuals, this group may be more vigilant to non-verbal cues from White targets that signal negative attitudes (Bernstein et al., 2008) and may be a more accurate decoder of prejudicial attitudes.

It is also possible that Black and White perceivers might be more accurate in detecting anti-Black attitudes when targets are speaking to Black women compared to Black men. Black women might suffer from the “double jeopardy hypothesis” of prejudice (Beale, 1970) where they might receive more negative non-verbal behavior than Black men because of their identification with two marginalized groups (Black and a woman) as opposed to only one marginalized group (Black). As a result, targets might more readily express their anti-Black attitudes toward Black women than Black men, allowing for there to be more available non-verbal cues to aid perceivers' accuracy. People also feel more comfortable in interactions with women in general. In one meta-analysis, Roter et al. (2002) found that patients display more behaviors consistent with comfort (e.g., disclosure, engagement) when speaking with women physicians compared to men physicians. Thus, targets might display more genuine, ecologically valid cues consistent with their levels of anti-Black attitudes when speaking with a Black women compared to a Black man, providing more available target cues for perceivers to make an accurate judgment about targets' anti-Black attitudes.

Though no studies to our knowledge have documented ecological validity, cue utilization, nor accuracy differences when targets are speaking to Black women vs. Black men, previous work addressing the accuracy of perceiving anti-Black attitudes has answered different but related research questions than the present study. In Richeson and Shelton's (2005) study, targets' IAT scores were compared to perceivers' judgments of target prejudice on a scale from 1 (low) to 9 (high). Similarly, Hehman et al. (2013) addressed how perceivers' judgments of targets' prejudice on a 1 (not at all) to 6 (extremely) scale predicted targets' explicit self-reports of racial prejudice. Rollman (1978) examined how accurately Black and White individuals could make a binary judgment about each target's prejudice level (high prejudice vs. low prejudice). While these studies start to address accuracy in detecting anti-Black attitudes, they are limited in that targets and perceivers are not using the same instrument to assess anti-Black attitudes. This study is the first to examine accuracy in detecting anti-Black attitudes in a systematic way by understanding the cues to anti-Black attitudes (ecological validity) and perceivers' judgments of anti-Black attitudes (cue utilization). Specifically, we matched the assessment of anti-Black attitudes for both the targets' self-reports and perceivers' judgments of each target.

Given the shift to greater use of video conferencing platforms such as Zoom in everyday life and in workplace settings, it is especially important to understand if people can accurately perceive others' anti-Black attitudes through a computer-mediated platform. Since the beginning of COVID-19, the use of videoconferencing platforms such as Zoom has increased 500% (Sadler, 2021). Additionally, 90% of organizations use Zoom for first round interviews (Sarkar, 2023). It is plausible that biased non-verbal behavior can be transmitted through these platforms during workplace interactions including during the interview setting. For the first time, we extend the expression and detection of anti-Black attitudes to a videoconferencing interview context.

The purpose of the following studies is to identify behavioral cues and impressions that are related to targets' anti-Black attitudes when interviewing with a Black men or woman on Zoom (Study 1), to test Black and White perceivers' accuracy in detecting targets' anti-Black attitudes over Zoom (Study 2), and to observe which non-verbal cues and impressions expressed by the targets influenced Black and White perceivers' judgments of anti-Black attitudes (Study 2).

Overview of studies

Study 1

In Study 1, White undergraduates (referred to as “targets”) at a large University in the northeast completed a mock interview with a Black interviewer. Research assistants then coded their non-verbal behavior. We correlated coded non-verbal behaviors (e.g., blinking, smiling) and non-verbal impressions of target behavior (e.g., anxiety, anger, positivity) with targets' self-reports on the Modern Racism Scale (MRS; McConahay, 1986), a measure of anti-Black attitudes, to assess ecological validity, the degree to which non-verbal cues were related to anti-Black attitudes (see Table 1 for a full list of non-verbal behaviors and impressions). We compared ecological validity correlations between targets interviewing with Black women and Black men interviewers.

Study 2

In Study 2, Black and White perceivers watched silent videos of the White targets from Study 1 who were completing the mock interview with the Black interviewer. Perceivers inferred each target's anti-Black attitudes using the same scale that was completed by the targets (MRS; McConahay, 1986). We correlated coded non-verbal behaviors and impressions with perceived anti-Black attitudes to assess cue utilization. Finally, we assessed accuracy by correlating perceived anti-Black attitudes with targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes, which reflects the degree to which perceivers could distinguish targets with higher from targets with lower anti-Black attitudes. We compared cue utilization and accuracy correlations among targets interviewing with Black women and Black men interviews.

Hypotheses

Study 1

Hypothesis 1: ecological validity

We hypothesized that targets with higher anti-Black attitudes compared to lower anti-Black attitudes would display less coded non-verbal involvement (less smiling, less gaze, less hand gesturing, more shoulders away from the interviewer, less movement toward the interviewer, and display a less positive impression). Additionally, targets with higher anti-Black attitudes would show more negative arousal through more blinking, and more coded impressions of anxiety and anger. Lastly, targets' anti-Black attitudes would be more strongly related to the above non-verbal behaviors when speaking to Black women interviewers compared to Black men interviewers.

Study 2

Hypothesis 2: cue utilization

We hypothesized that perceivers would infer higher anti-Black attitudes compared to lower anti-Black attitudes from targets who displayed more ecologically valid cues of anti-Black attitudes (i.e., less non-verbal involvement and more negative arousal behaviors). Perceiver ratings of targets' anti-Black attitudes would be more strongly related to behavioral cues when targets were interviewing with a Black woman vs. a Black man interviewer.

Hypothesis 3: accuracy

We hypothesized that Black and White perceivers would, on average, accurately infer targets' anti-Black attitudes at an above-chance level. We hypothesized that Black perceivers would have significantly higher accuracy than White perceivers (Richeson and Shelton, 2005; Rollman, 1978). Lastly, since we hypothesized that targets would display more ecologically-valid cues toward Black women interviewers compared to Black men interviewers, we further hypothesized that perceivers would be more accurate in detecting anti-Black attitudes when targets were interviewing with Black women compared to Black men.

Study 1

Method

Participants

N = 76 White undergraduate students (“targets,” Mage = 19.47, SD = 3.03) at a large University in the northeast participated in this study in exchange for partial course credit. Fifteen targets expressed disbelief in the study's authenticity following a funnel debriefing at the end and were excluded, for a final sample of N = 61. An a priori power analysis suggested that N = 82 targets would be sufficient to detect a medium effect size (two-tailed, ρ = 0.30, α = 0.05, power = 0.80), thus our sample of N = 61 was slightly underpowered. However, this sample size was typical of ecological validity investigations for lens models (Bernieri et al., 1996). Furthermore, it was more important for targets to exhibit relevant (i.e., related to the criterion of interest) and available (i.e., accessible to a perceiver) non-verbal cues to be able to detect significant ecological validity correlations, compared to collecting a high number of targets (Funder, 1995). Specifically, targets in this study were likely to exhibit cues relevant to racism, as the design is consistent with other studies who utilize an interview format and found that targets displayed cues consistent with their attitudes (McConnell and Leibold, 2001). Second, these cues were likely available for the perceiver because of the mounting evidence that targets' racism “leaks” through their non-verbal behavior toward Black individuals (Dovidio et al., 1997; McConnell and Leibold, 2001). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at [University of Rhode Island].

Procedure

Anti-Black target stimuli

Targets joined a Zoom call as part of a study entitled “Conversations About Careers,” where they were under the impression that the study was being conducted to assess how well interviews flow over videoconferencing platforms such as Zoom (Weaver, 2022). Twelve research assistants (one Asian American research assistant, one Latine research assistant, and 10 White research assistants) guided targets through the study sessions. These experimenters kept their camera off the entire time. A supposed “interviewer” joined the Zoom call with the target. However, the interviewer was not real and was another research assistant playing recordings for the target to interact with and had their profile picture changed to a picture of a Black interviewer with their camera off. Targets were randomly assigned to interview with a Black woman or Black man. The targets were instructed to alter their Zoom settings to ensure that the interviewer was the only image that they could see on the screen and so the interviewer took up their entire screen. Specifically, targets were instructed in Speaker Mode to hide their Self-View. In addition, we instructed targets to place their devices approximately three feet away so that all target sessions appeared similarly on a recording and their torso and head were in view.

The audio recordings of the interviewer were recorded by a trained White woman actor. The same recordings were used for all conditions, except we tuned her voice down in pitch for the man interviewer audio. To adjust the pitch of the audio, we used the LingoJam Female to Male Voice Changer, uploaded the clips, and selected the “lower pitch” option (Lingojam, n.d.). There was no relationship between suspected inauthenticity and race (p = 0.152) nor gender (p = 0.456) of the interviewer. Experimenters recorded from the moment the interviewer joined the call, to right after the interviewer had to leave. The interviews were, on average, 3 minutes and 25 seconds. We extracted one clip (approximately 30 s in length; Msec = 28.37, SDsec = 2.59, Minsec = 19.80, Maxsec = 30) from the entire interaction that started right after the interviewer asked the target “What are your greatest strengths and skills?”, until the target stopped talking (see Supplementary material for partial script). We selected this clip because it was the first time that the target interacted with the interviewer.

The targets reported their explicit anti-Black attitudes using the Modern Racism Scale (MRS; McConahay, 1986) right after the end of the interview and with their camera turned off. The MRS (α = 0.86, M = 1.46, SD = 0.57, skewness = 1.47, kurtosis = 1.70) is related to other measures and constructs aligned with anti-Black attitudes, such as negative attitudes of Black Lives Matter and the belief that inequality does not exist in the United States (McConahay, 1986; Miller et al., 2021). The MRS contains several statements pertaining to the rights and respect afforded to Black people in the United States and beliefs about whether it is deserved. One example item is “Black people are getting too demanding in their push for equal rights” (see the Supplementary material for all survey items). Responses to these statements were anchored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A higher score on the scale indicates higher anti-Black attitudes. Language in the scale was adapted (e.g., “Blacks” was changed to “Black people”). After the mock interview and questionnaire, targets gave permission for their videos to be used in future studies where new participants would watch their silent videos and make inferences about them.

Ten White trained research assistants (separate from the 12 experimenters above) watched the clips of the mock interviews, without sound, and coded each clip for non-verbal behaviors and impressions. Coders were blind to the purpose of the study, and unaware that targets were speaking to Black individuals, and unaware that the study was about race. Coders rated non-verbal behaviors such as smiling, nodding, gesturing, gaze directed toward the computer screen (e.g., “screen gaze”), movement toward the interviewer, and shoulders angled away from the interviewer (the extent to which targets' shoulders were not square with the screen) on a scale from 1 (not at all often) to 9 (extremely often). In addition, the coders rated several more global impressions of the face and body including expressivity, friendliness, positivity, anxiety, hireability, irritation, discomfort, effort, animation, engagement, fidgeting, liking of the interviewer, and rapport with interviewer from 1 (not at all) to 9 (extremely). A second set of research assistants independent from experimenters and original coders (including one Black research assistant and 10 White research assistants) rated the impression of anger on the same 1 (not at all) to 9 (extremely) scale at a later date. Coders completed three rounds of coding (~20 videos each); between each round interrater reliability was assessed and if interrater reliability was low, the researcher provided examples to research assistants of target videos at the high end and low end of the impressions/behaviors that were not reaching reliability. All behaviors and impressions reached an alpha level of at least 0.60, with a mean reliability of α = 0.75 (Rosenthal and Rosnow, 1984). See Table 1 for a full list of coded non-verbal behaviors and impressions.

We used the software FaceReader to calculate blinking rate (Dovidio et al., 1997). Blinking rate was defined as the number of blinks in the video divided by the total time. We also obtained emotion expressions (happy, sad, angry, surprised, scared, disgusted, valence and arousal) from FaceReader every 0.5 s on a scale from 0 (least intense or not discernable) to 1 (most intense or completely present). We calculated a mean estimate for each emotion across each of the 0.5 s intervals.

Analyses

Modern racism scale

Due to the nature of the MRS, scores were positively skewed and clustered toward the lower end of the scale. This is expected, as self-reports of racial bias are more susceptible to socially desirable responding, as most people are aware that non-egalitarian views of Black individuals are not socially acceptable (Krieger et al., 2010). Although researchers may log transform variables that are not normally distributed, there is reason to retain the original distribution. First, transformations change the research question being asked as data are transformed to use geometric means instead of arithmetic means (Field, 2013). Second, in other literature including the MRS and others like it, the original distributions were unchanged and there were no transformations made (Aosved and Long, 2006; Miller et al., 2021). Therefore, we retained the original MRS values in all analyses.

Ecological-validity

To establish ecological validity of the behaviors and impressions, we correlated the intensity and frequency of all coded target cues with targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes. We then examined results separately by interviewer gender.

Composite creation

A Principal Components Analysis with an oblique rotation with coder impression and behavior ratings revealed that many of the impression ratings loaded onto the same factor (> |0.7|) and were highly correlated (α = 0.96). Among these impressions were positivity, expressiveness, hireability, animation, effort, engagement, friendliness, how much targets seemed to like the interviewer, and how much they seemed to have rapport with the interviewer. These were collapsed to create a single “positive impression” composite (M = 6.02, SD = 1.03). In addition, in the same factor analysis, anxiety, discomfort, awkwardness, and fidgeting (α = 0.77) loaded onto the same factor with a cutoff of |0.7|, so these impressions were collapsed to create an “anxiety” composite (M = 3.38, SD = 0.94, α = 0.77). Lastly, the code “irritation” loaded onto the same factor as “anger” (> |0.7|), and the two were combined to create the “agitation” composite (α = 0.67). The code “likable” did not load sufficiently onto any factor and was analyzed only as a single impression rating. Behaviors (i.e., smiling, screen gaze) also did not sufficiently load onto any factor and was analyzed separately.

Results

A correlation matrix of all non-verbal behaviors and the impression composites can be found in the Supplementary material. A correlation matrix with FaceReader codes and human coder ratings of impressions can also be found in the Supplementary material.

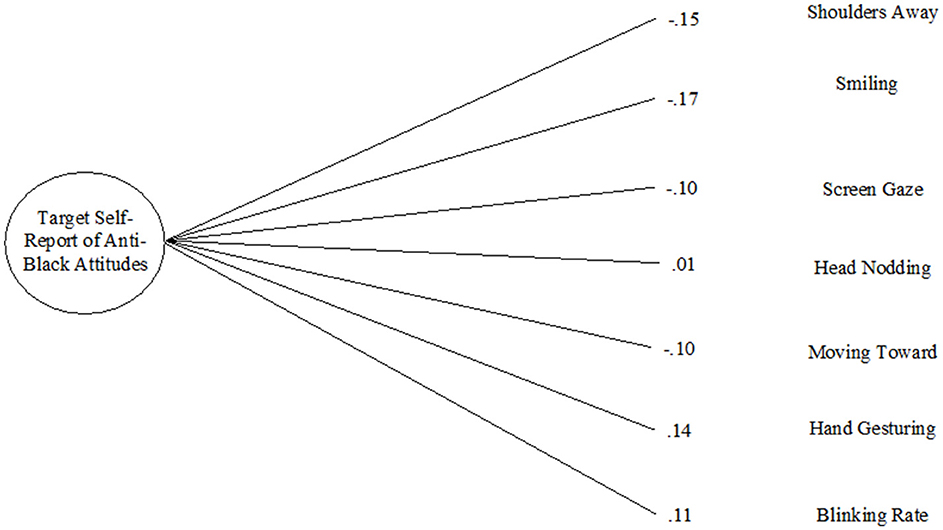

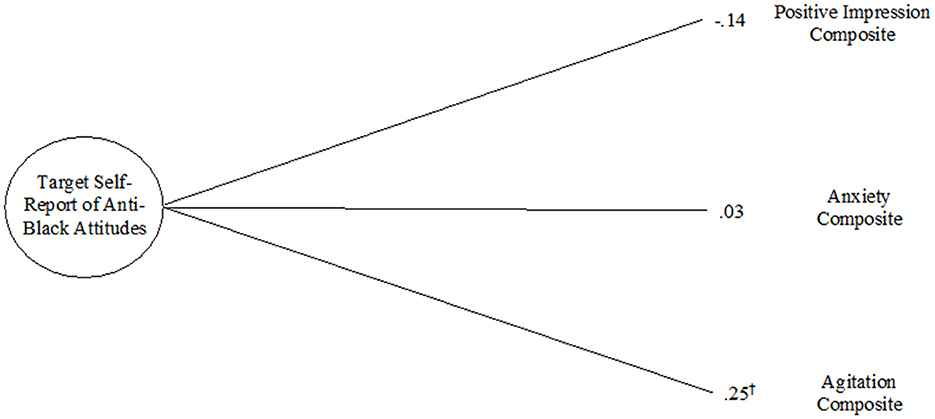

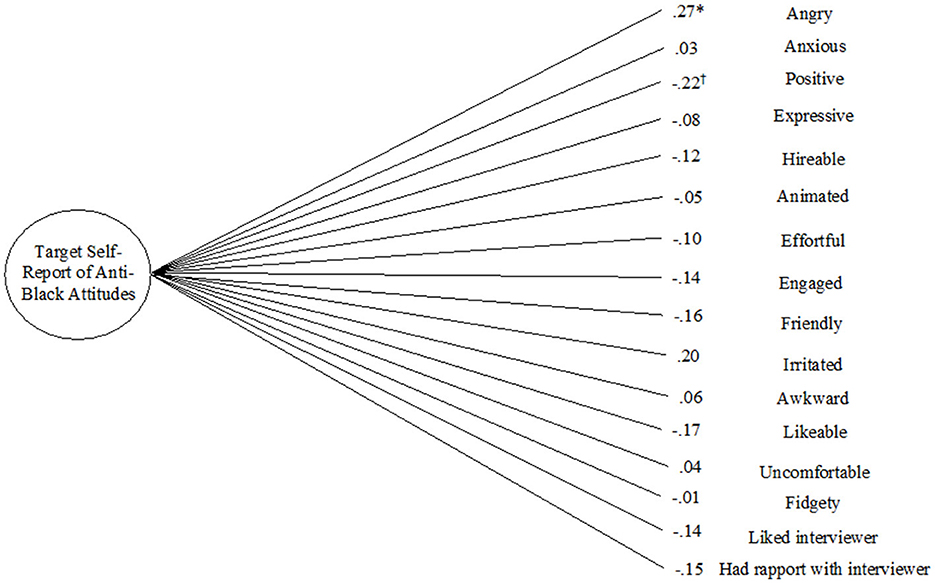

Ecological validity

Ecological validity is the degree to which targets' cues (non-verbal behaviors and impressions) correlate with targets' -reported anti-Black attitudes (Brunswik, 1952). Targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes were significantly related to the coded impression of anger when using the single-item impression of anger [r(59) = 0.27, p = 0.033]. That is, targets with higher anti-Black attitudes appeared angrier. When using the agitation composite (combining anger and irritation), coded impressions of anger were not significantly related to anti-Black attitudes [r(59) = 0.25, p = 0.055]. No other impressions or behaviors were significantly related to anti-Black attitudes (all r's <|0.16|, p's > 0.277); See Figures 2–4.

Figure 2. Ecological validity of anti-Black attitudes: the associations between targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes and non-verbal behaviors.

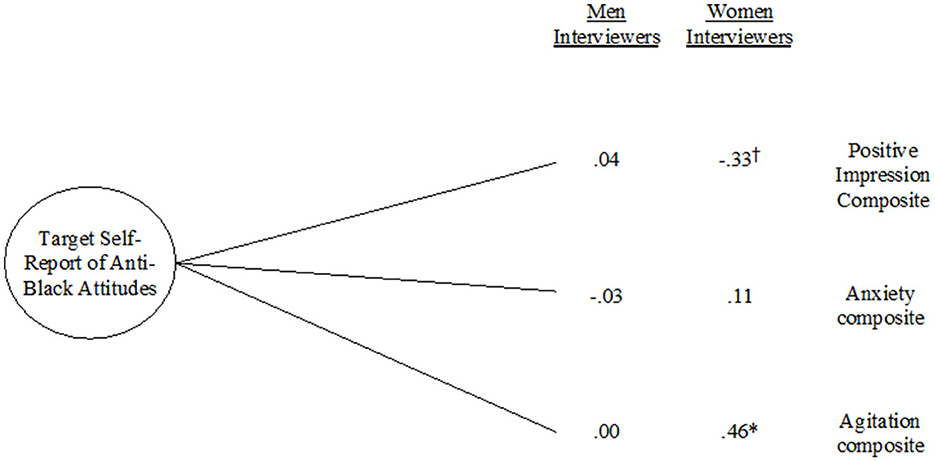

Figure 3. Ecological validity of anti-Black attitudes: the associations between targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes and composite impression ratings. †p < 0.10.

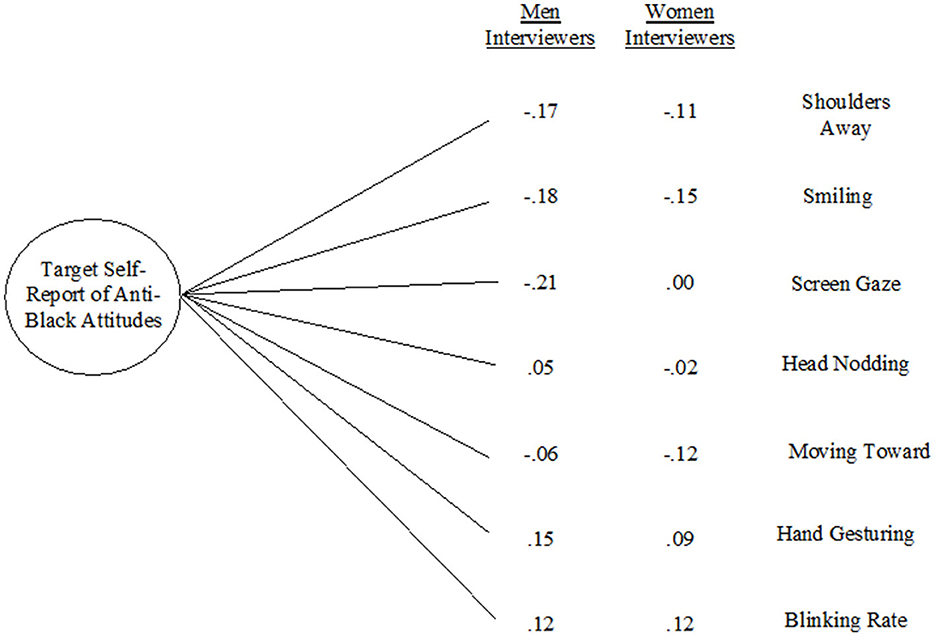

Figure 4. Ecological validity of anti-Black attitudes: the associations between targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes and non-verbal behaviors split by gender of interviewer.

Interviewer gender

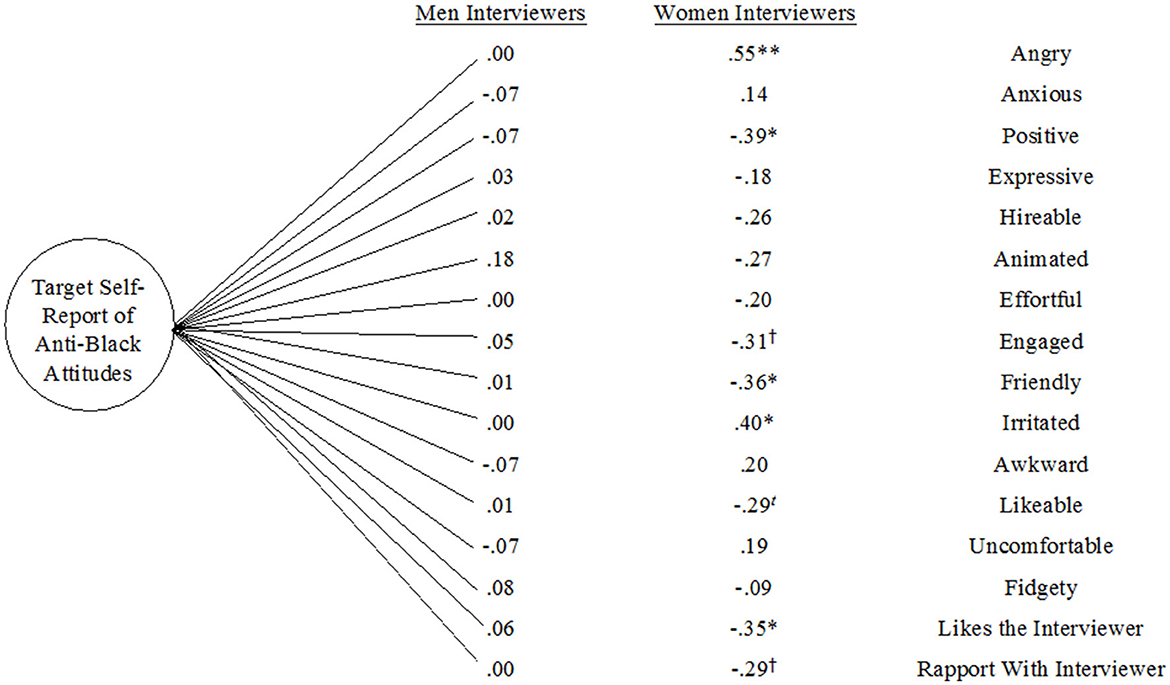

When examining results separately by gender, there were no significant ecological validity correlations for behaviors nor impressions when targets were interviewing with a Black man (all r's <|0.21|, p's > 0.270). However, when targets were interviewing with a Black woman, several significant associations emerged between targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes and non-verbal impressions ratings (See Figures 5–7). Specifically, in interviews with Black women, targets' higher self-reported anti-Black attitudes were significantly related to more coded impressions of anger [agitation composite, r(31) = 0.46, p = 0.007; individual impression rating, r(31) = 0.55, p < 0.001] and less positivity [positive impression composite, r(33) = −0.33, p = 0.065; individual impression rating, r(31) = −0.38, p = 0.026].

Figure 5. Ecological validity of anti-Black attitudes: the associations between targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes and composite impression ratings split by gender of interviewer. *p < 0.05, †p < 0.10.

Figure 6. Ecological validity of anti-Black attitudes: the associations between targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes and individual impression ratings. **p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, †p < 0.10.

Figure 7. Ecological validity of anti-Black attitudes: the associations between targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes and individual impression ratings. *p < 0.05, †p < 0.10.

Study 1 discussion

The purpose of Study 1 was to identify non-verbal behaviors and impressions related to non-verbal involvement and negative arousal that were related to anti-Black attitudes measured via the Modern Racism Scale (MRS) during a Zoom mock job interview with a Black interviewer. We identified one non-verbal impression rating, anger, that was significantly related to higher self-reported anti-Black attitudes when using the single-item rating and not the agitation composite. We extend past work on interracial interactions, showing that there is in fact observable behaviors related to explicit prejudicial attitudes. While we cannot make any claims about internal states of targets, the finding that more non-verbal impressions of anger were related to self-reported anti-Black attitudes is consistent with past work on negative arousal (Burgoon et al., 1989) and the prevalence of outgroup directed anger (Mackie and Smith, 2015). In addition, we found that targets' less positive behavior was only related to their self-reported anti-Black attitudes when targets were interviewing with a Black woman compared to a Black man.

Contrary to what we hypothesized, targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes were not related to coded anxiety, smiling, screen gaze, hand gesturing, shoulders away from the interviewer, nor movement toward the interviewer, regardless of the gender of the interviewer. It is possible that we could not view all behaviors related to anxiety due to the nature of teleconferencing (e.g., the frame did not include behaviors below the torso like leg shaking). Furthermore, since the topic of conversation was not race-related, this may have lessened the potential of targets appearing more anxious (Trawalter and Richeson, 2008). Similarly, it is possible that the computer-mediated format lessened the preciseness of human coding of the other behaviors thought to be related to non-verbal involvement (e.g., more screen gaze, more gesturing), making it harder for coders to perceive these behaviors. Future studies should conduct in-person studies where one can conduct more precise non-verbal coding methods.

However, other significant ecological validity relationships emerged when only including targets who were interviewing with Black women instead of Black men. Specifically, when targets were speaking to Black women, higher anti-Black attitudes manifested as less non-verbal involvement (e.g., less positivity) and more perceived negative affect/arousal (e.g., more anger), but these relationships were non-significant among targets who interviewed with Black men. While we do not know the mechanism responsible for more ecologically valid cues with the Black women interviewers compared to the Black men interviewers, past work would suggest one of two possible explanations. First, people tend to be more expressive and comfortable with women interaction partners compared to men interaction partners and therefore express more authentic non-verbal cues related to their internal states and traits including anti-Black attitudes (Becker et al., 2011). Alternatively, it could be that people might more readily express their racism toward Black women compared to Black men because of Black women's multiple marginalized identities making it easier to identify those higher from those lower in anti-Black attitudes (Beale, 1970).

The appearance of anti-Black non-verbal behaviors may be expressed in a subtle but insidious and pervasive manner such that one might expect their intensity is only slightly or modestly related to reports of one's racism. We still do not know if perceivers utilize these cues (or others) to make inferences of targets' anti-Black attitudes. Study 2 sought to examine what cues Black and White perceivers infer higher vs. lower anti-Black attitudes from and whether Black and White perceivers can accurately detect anti-Black attitudes across targets.

Study 2

Method

Participants

Participants (termed “perceivers”) were at least 18 years of age and we purposefully recruited a subsample of White and a subsample of Black perceivers. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at [University of Rhode Island].

Black perceiver sample

We recruited n = 123 Black perceivers through the online platform Prolific (see the Supplementary material for sociodemographic information). No Black perceivers failed attention checks embedded throughout the survey, though three Black perceivers showed behavior associated with inattentive responding (i.e., there was no variability in their responses), and we excluded them from analyses. In addition, there were six Black perceivers who identified with one or more additional racial or ethnic categories. These participants were excluded because there were too few multiracial participants to compare to White and Black perceivers. The final sample size was n = 114.

White perceiver sample

We also recruited n = 123 White perceivers from Prolific, but we excluded 10 perceivers for failing two or more attention checks and five for displaying inattentive responding behavior for a final sample size of n = 108 (see the Supplementary material for sociodemographic information).

To compare the independent group means of Black and White perceivers, an a priori power analysis suggested that N = 64 perceivers in each group would be sufficient (two-tailed, medium effect size of d = 0.50, α = 0.05, power = 0.80, allocation ratio N2/N1 = 1).

Procedure

To prevent the effects of perceiver fatigue, we divided the 61 target clips into three sets, and each perceiver was randomly assigned to a set of approximately 20–21 videos. The sets were matched on target anti-Black attitudes and target gender. Specifically, we conducted a one-way ANOVA where target set (set 1, set 2, set 3) was the independent variable and targets' MRS score (McConahay, 1986) was the dependent variable [F(2, 58) = 0, p = 1.00]. Second, we conducted a chi-square test where target set was the independent variable and gender (three levels: man, woman, gender non-conforming) was the dependent variable [ = 5.40, p = 0.482]. Perceivers watched the clips with sound off so that their judgments were based on the targets' non-verbal behaviors. Perceivers were instructed that the target was speaking to a Black/African American person for context. After watching each clip, perceivers were asked to infer the target's anti-Black attitudes using the same scale that targets had completed, the MRS (McConahay, 1986; e.g., “The person in this video believes that…Black people should not push themselves where they are not wanted”). The MRS was internally reliable (α = 0.83 for Black perceivers; α = 0.92 for White perceivers).

Analyses

Cue utilization

To calculate the extent to which perceivers inferred anti-Black attitudes from target non-verbal behaviors and impressions, we conducted a series of correlations between perceiver-rated anti-Black attitudes, non-verbal behaviors, and impressions. We also examined the difference in cue utilization correlations when the target was interviewing with a Black woman compared to a Black man.

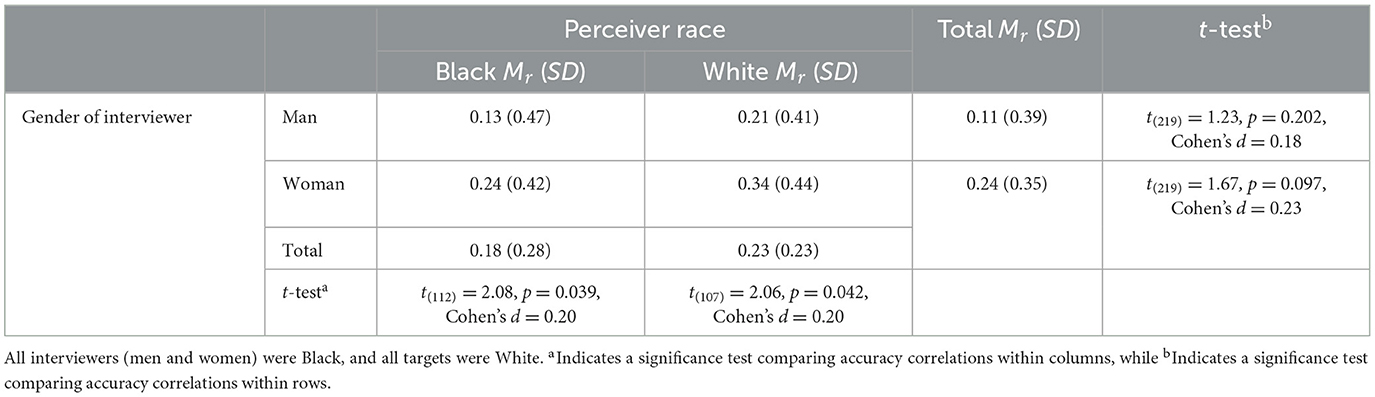

Accuracy

We examined the extent to which perceivers could discriminate targets with higher anti-Black attitudes from targets with lower anti-Black attitudes by correlating each perceiver's rating of a target's anti-Black attitudes (using the mean MRS score for each perceived target) with each target's self-reported anti-Black attitudes (using each target's self-reported mean MRS score). This resulted in an accuracy correlation for each perceiver that explained their ability, on average, to discriminate higher from lower anti-Black attitudes across the 20–21 targets they rated. To test whether perceivers were accurate above chance, we conducted a one-sample t-test against 0 (chance level). An independent samples t-test examined the difference between Black and White perceivers' average accuracy. We also conducted two paired sample t-tests to examine if Black and White perceivers differed in accuracy depending on the gender (man vs. woman) of the interviewer that the target was speaking with. For all analyses, accuracy correlations were transformed into Fisher z scores for analyses and transformed back into Pearson correlation coefficients for presentation.

Vector correlations

To examine whether the cue utilization correlations followed a similar pattern as the ecological validity correlations (i.e., making it the “correct” pattern), we conducted vector correlations for Black and White perceivers. Vector correlations offer a valuable perspective on accuracy because they reveal how effectively perceivers “use” valid cues provided by targets by calculating the standardized covariance between all cues in the ecological validity and cue utilization correlations (Back and Nestler, 2016; Gosling et al., 2002). We calculated vector correlations by correlating the ecological validity correlations with the cue utilization correlations, for both Black and White perceivers separately. Specifically, we correlated the column of ecological validity correlations (i.e., each row is a different correlation) with the column of cue utilization correlations. Each row corresponded to one non-verbal cue. For example, we correlated the ecological validity correlation for the code “angry” with the cue utilization correlation for the code “angry,” and this was done for all cues simultaneously.

Results

Cue utilization

Cue utilization is the degree to which certain cues were present or more intense when perceivers inferred higher anti-Black attitudes (Brunswik, 1952).

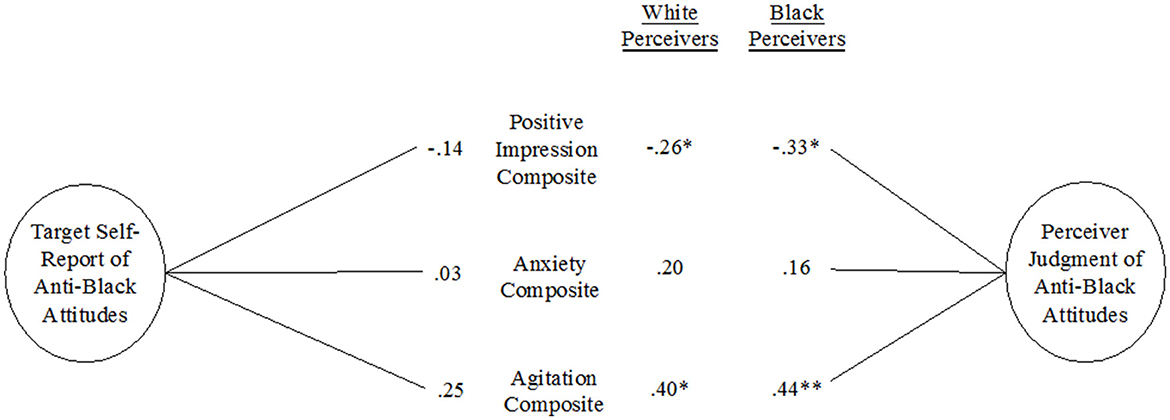

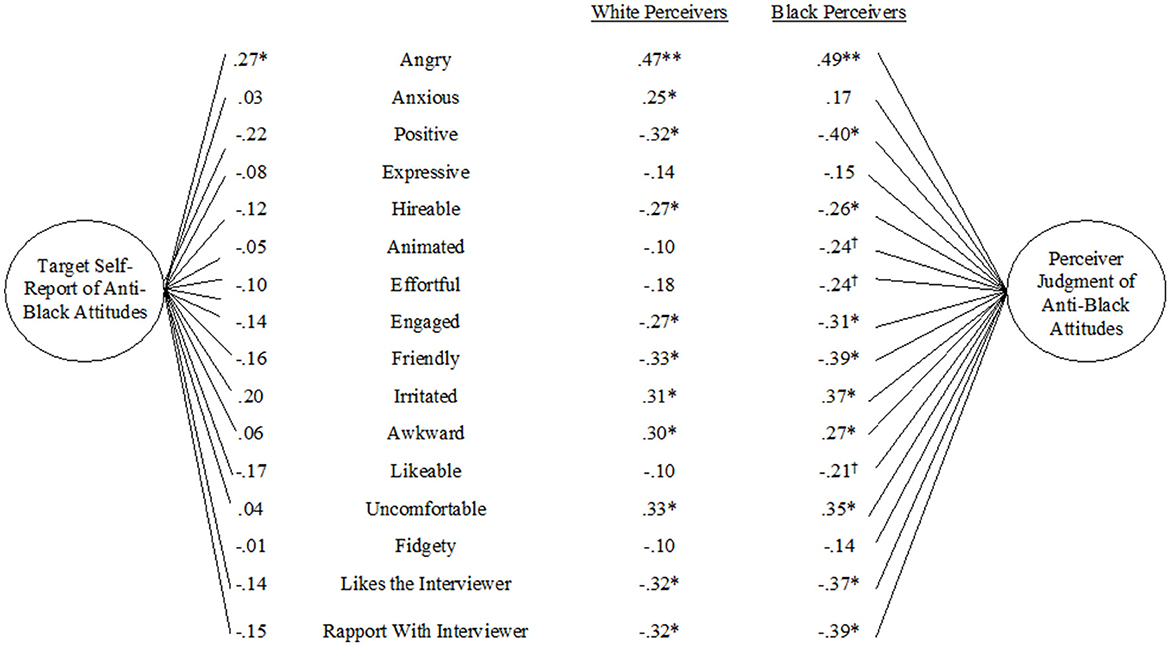

Black perceivers

Black perceivers inferred higher anti-Black attitudes when targets smiled less [r(59) = −0.40, p = 0.001], made a less positive impression [positive impression composite, r(59) = −0.33, p = 0.010; individual impression rating, r(59) = −0.40, p = 0.001] and appeared more angry [agitation composite, r(59) = 0.44, p < 0.001; individual impression rating, r(59) = 0.49, p < 0.001] (See Figures 8–10).

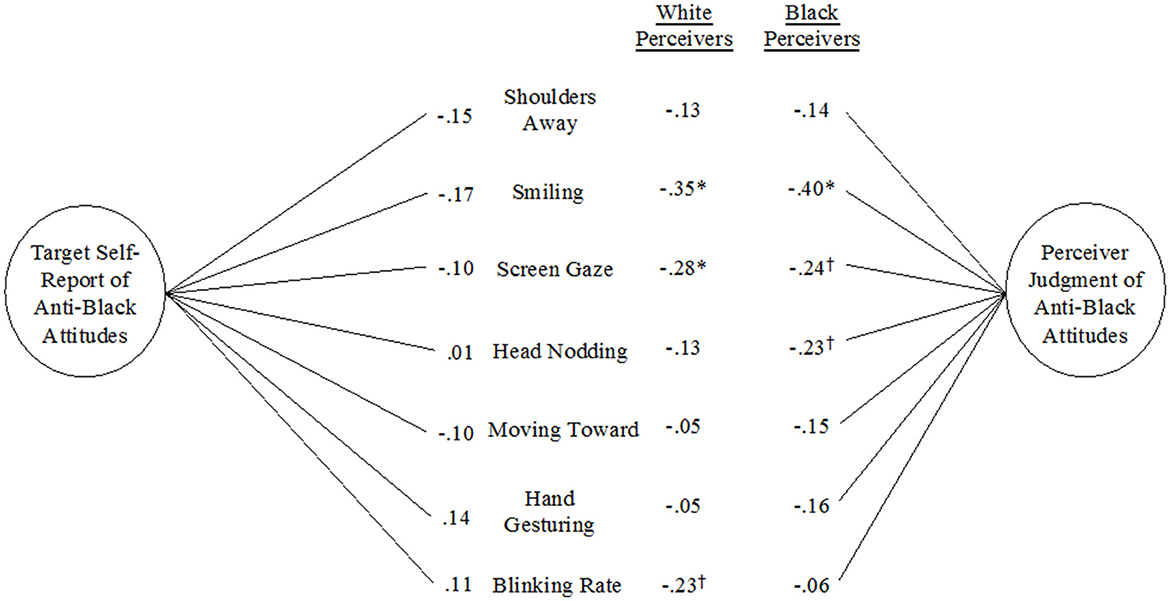

Figure 8. Lens model of Black and White perceiver judgments of targets' anti-Black attitudes, targets' non-verbal behaviors, and targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes. *p < 0.05, †p < 0.10.

Figure 9. Lens model of Black and White perceiver judgments of targets' anti-Black attitudes, targets' non-verbal composite impressions, and targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

Figure 10. Lens model of Black and White perceiver judgments of targets' anti-Black attitudes, targets' non-verbal individual impressions, and targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, †p < 0.10.

White-perceivers

Similar to Black perceivers, White perceivers inferred higher anti-Black attitudes when targets smiled less [r(59) = −0.35, p = 0.006], directed their gaze less at the screen [r(59) = −0.28, p = 0.027], made a less positive impression [positive impression composite, r(59) = −0.26, p = 0.043; individual impression rating, r(59) = −0.32, p = 0.013] and appeared more angry [agitation composite, r(59) = 0.40, p = 0.002; individual impression rating, r(59) = 0.47, p < 0.001].

None of the cue utilization correlations were significantly different from each other when comparing Black and White perceivers (all r's > |0.05|, all p's > 0.201).

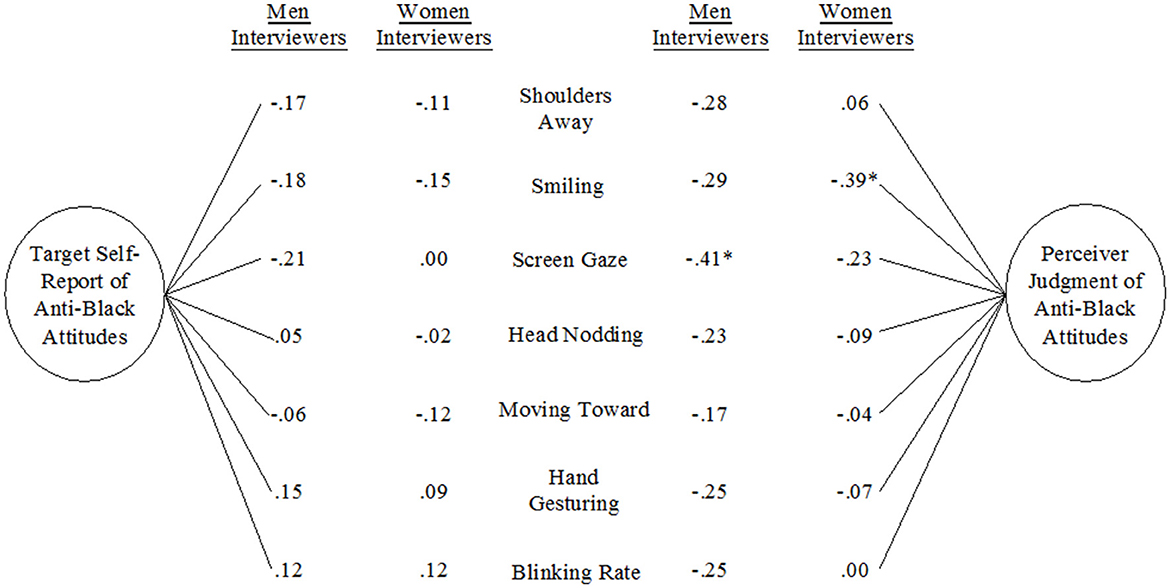

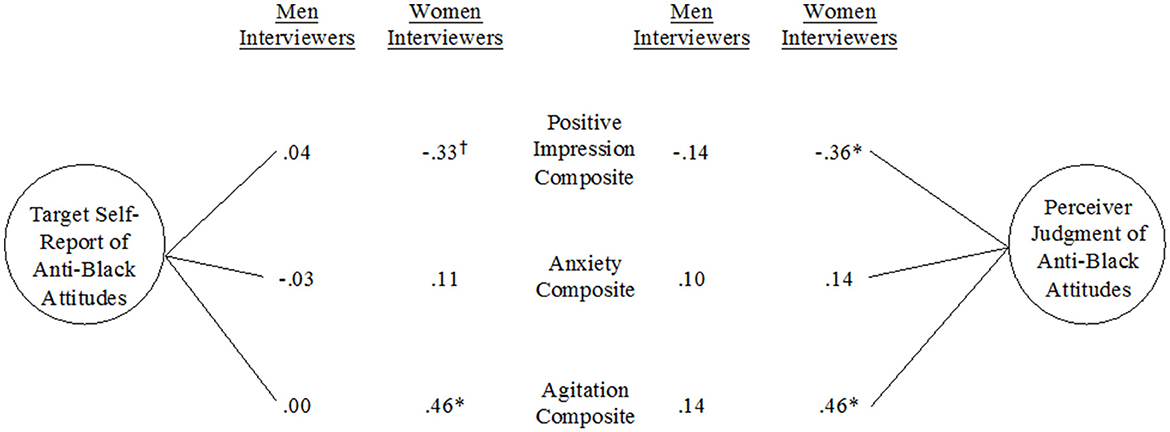

Interviewer gender

Consistent with our hypothesis, non-verbal behaviors and impressions were largely only related to perceiver judgments of anti-Black attitudes when targets were interviewing with a Black woman and not a Black man (see Figures 11–13). Specifically, among targets interviewing with Black women, perceivers inferred higher anti-Black attitudes when targets smiled less [r(31) = −0.39, p = 0.027], made a less positive impression [positive impression composite, r(31) = −0.36, p = 0.042; individual impression rating, r(31) = −0.43, p = 0.013], and appeared more angry [agitation composite, r(31) = 0.46, p = 0.009; individual impression rating, r(31) = 0.49, p = 0.004]. Perceivers only inferred higher anti-Black attitudes when targets displayed less screen gaze when interviewing with a Black man [r(27) = −0.41, p = 0.027], but not with a Black woman (p = 0.216).

Figure 11. Lens model of perceiver judgments of targets' anti-Black attitudes, targets' non-verbal behaviors, and targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes split by gender of interviewer. *p < 0.05.

Figure 12. Lens model of perceiver judgments of targets' anti-Black attitudes, targets' non-verbal impression composites, and targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes split by gender of interviewer. *p < 0.05, †p < 0.10.

Figure 13. Lens model of perceiver judgments of targets' anti-Black attitudes, targets' individual impression ratings, and targets' self-reported anti-Black attitudes split by gender of interviewer. **p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, †p < 0.10.

Accuracy

Accuracy correlations

Accuracy in detecting anti-Black attitudes for both Black and White perceivers (see Table 2 for average accuracy scores of each perceiver group) was significantly greater than chance (i.e., guessing), as demonstrated by two significant one-sample t-tests with large effects [Black; t(113) = 6.19, p < 0.001, d = 0.64, White; t(108) = 10.78, p < 0.001, d = 1.0]. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was not a significant difference between Black and White perceivers' accuracy in detecting anti-Black attitudes [t(226) = 1.81, p = 0.071, d = 0.20]. Among Black [t(112) = 2.08, p = 0.039] and White perceivers [t(107) = 2.06, p = 0.042], paired sample t-tests revealed that perceivers were more accurate in rating targets interviewing with Black women compared to Black men, as hypothesized. Perceivers were accurate at above chance levels when detecting anti-Black attitudes of targets interviewing with Black men [t(220) = 5.70, p < 0.00, d = 0.38] and Black women [t(221) = 9.90, p < 0.001, d = 0.67] separately.

Table 2. Accuracy scores by perceiver race and gender of the interviewer interacting with the target.

As an exploratory analysis, we sought to examine if expressivity of the targets differed by interviewer gender to help explain why cue utilization and accuracy was improved when targets were in Black women-led interviews (n = 32) compared to targets in Black men-led interviews (n = 29). If targets showed increased expressivity to Black women, then this might allow anti-Black non-verbal cues to be more available to the perceiver. We found that targets were significantly more expressive when interacting with Black women (M = 5.77, SD = 1.23) compared to Black men (M = 5.06, SD = 1.11) [t(60) = 2.38, p = 0.021, d = 0.61].

Vector correlations

For both Black and White perceivers, cue utilization correlations and ecological validity correlations were correlated strongly [Black perceivers: r(21) = 0.83, p < 0.001; White perceivers: r(21) = 0.78, p < 0.001]. These vector correlations suggest that both Black and White perceivers tended to utilize the appropriate pattern of cues when making inferences about anti-Black attitudes.

Discussion

Cue utilization

The purpose of Study 2 was to examine the cues that were related to perceiver judgments of anti-Black attitudes, and whether perceivers were accurate in inferring targets' anti-Black attitudes. We sought to examine how behaviors related to non-verbal involvement and negative arousal contributed to perceiver judgments of anti-Black attitudes. We hypothesized that less non-verbal involvement and more behaviors related to negative arousal would be related to higher perceiver judgments of anti-Black attitudes. Our hypothesis was partially supported, in that less smiling, a less positive impression, and more impressions of anger (when using both the single item rating and agitation composite) were related to higher perceived anti-Black attitudes for both Black and White perceivers. For White perceivers only, less screen gaze was related to higher perceived anti-Black attitudes.

Individuals high in prejudice tend to act more unfriendly toward Black people than those that are low in prejudice (Dovidio et al., 2002, 1997; Willard et al., 2015). It may also be that White people that fear looking prejudiced to Black individuals may act in an overly positive manner toward Black individuals, engaging them more (LaCosse et al., 2015; Kunstman et al., 2016). Edinger and Patterson (1983) proposed a functional perspective of social control in social interactions such that when one holds negative expectations about another person, they might increase smiling as a behavioral strategy to counteract an unfriendly interaction. Therefore, targets who made a more positive impression could have plausibly displayed either higher or lower anti-Black attitudes. In the current study, however, when targets made a less positive impression (e.g., less smiling, less positivity) and appeared more angry, Black and White perceivers inferred higher anti-Black attitudes. Thus, it appears that White targets higher in anti-Black attitudes were not trying to mask or counteract the display of their negative attitudes but rather were behaving in a more overtly negative fashion toward the Black interviewer and perceivers were able to infer anti-Black attitudes from these more negative and less non-verbally involved behaviors.

As hypothesized, cue utilization relationships were largely non-significant when only including targets interviewing with Black men interviewers. However, significant relationships between higher perceiver judgments of anti-Black attitudes and non-verbal cues (i.e., less smiling, more anger—single item, more anger—agitation composite, less positivity, less engagement, less friendliness, more irritation, more discomfort, less apparent liking of the interviewer, and less apparent rapport with the interviewer) emerged when only including targets interviewing with Black women. Given the significant ecological validity correlations that emerged in Black women-led interviews only, it follows that significant cue utilization correlations would emerge because targets were displaying more ecologically valid cues related to their anti-Black attitudes in Black women-led interviews, and perceivers may be more likely to pick up on ecologically valid cues (Brunswik, 1952; Funder, 1995).

Accuracy

We hypothesized that Black and White perceivers would, on average, be able to infer targets' anti-Black attitudes at an above-chance level. This hypothesis was supported. That is, perceivers were not merely guessing when rating targets' anti-Black attitudes. These accuracy results parallel and extend past research on the accurate detection of anti-Black attitudes (Richeson and Shelton, 2005; Rollman, 1978). Even though the effect sizes were small (rBlack = 0.18 and rWhite = 0.23), this was expected for several reasons. First, attitudes are a latent construct and not immediately obvious (Paunonen and Kam, 2014). Second, the videos had no verbal content; therefore, perceivers could not hear any explicit language that may have aided in their detection of anti-Black attitudes, which in past work has aided perceivers' accuracy in other person perception domains (e.g., lie detection; Hartwig and Bond, 2011). Third, the videos contained only thin slices (30 s) of behavior and while accuracy is usually above chance even when using thin slices of behavior, it is rarely very high unless the stimuli or targets are displaying prototypical expressions (e.g., Krumhuber et al., 2021). Finally, perceivers made judgments at zero-acquaintance, that is, they did not know the people in the videos, which is a more difficult task than making judgments after having a relationship with the target and understanding a person's behavior more generally (Borkenau et al., 2004).

We also hypothesized that Black perceivers would be significantly more accurate than White perceivers in detecting anti-Black attitudes. This hypothesis was not supported. White perceivers had a slightly higher average accuracy in detecting anti-Black attitudes than Black perceivers (d = 0.20), though this difference was not significant. This was surprising considering past studies found that Black individuals were better able to detect anti-Black attitudes than White individuals (Richeson and Shelton, 2005). Marginalized groups might be more vigilant in detecting bias against one's own group, since the information is personally relevant to them (Goh et al., 2017; Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002; Zebrowitz and Collins, 1997). However, there is literature to suggest a same-race advantage in detecting internal states (Gray et al., 2008; Weathers et al., 2002), though these results need to be replicated.

Vector correlations revealed that Black and White perceivers' pattern of cue utilization correlations closely matched the pattern of ecological validity correlations. This means that Black and White perceivers were both able to identify the pattern of cues associated with anti-Black attitudes. Despite the above findings that White perceivers had a higher mean accuracy score than Black perceivers, Black individuals did have a slightly higher vector correlation than White individuals. This means that Black perceivers were slightly better than White perceivers at inferring higher anti-Black attitudes from cues that were more related to anti-Black attitudes, but also not systematically inferring higher or lower anti-Black attitudes from cues that were not related to anti-Black attitudes (i.e., ignoring a cue that is unrelated to anti-Black attitudes or a correct rejection). While more non-verbal impressions of anger were significantly related to both higher self-reported anti-Black attitudes (when using the single item rating) and higher perceiver judgments of anti-Black attitudes (when using both the single item rating and agitation composite), the magnitude of the vector correlations suggests that a single cue may not solely account for accuracy in detecting anti-Black attitudes. Rather, it appears to be how perceivers infer anti-Black attitudes from multiple cues in concert.

Lastly, our hypothesis was supported in that accuracy was significantly greater when perceivers were rating targets in Black women-led interviews compared to targets in Black men-led interviews. Perceivers were inferring anti-Black attitudes from actual cues related to anti-Black attitudes in Black women-led interviews. In Black men-led interviews, targets were less expressive and thus there were less available cues to infer anti-Black attitudes and perceivers appeared to have a harder time identifying what cues were related to anti-Black attitudes. Importantly, this critical difference in accuracy emerged even when perceivers were not given information about the gender of the interviewer.

General discussion

The present study sought to establish a network of non-verbal cues related to anti-Black attitudes (ecological validity), understand whether and how Black and White perceivers infer anti-Black attitudes from these cues (cue utilization), observe how accurate Black and White perceivers are in inferring targets' anti-Black attitudes, and to examine how the gender of the Black interviewer (woman vs. man) impacted ecological validity, cue utilization, and accuracy. This is a novel application of the lens model approach to the detection of anti-Black attitudes, extending previous literature in this area by observing the non-verbal cues that are related to Black and White perceiver judgments of anti-Black attitudes (Richeson and Shelton, 2005; Rollman, 1978).

We found one non-verbal impression, anger, that was significantly related to both explicit self-reports of anti-Black attitudes (when using the single-item rating) and perceivers' judgments of targets' anti-Black attitudes (when using both the single item rating and agitation composite). However, more coded anger was only related to higher anti-Black attitudes when targets were in Black women-led interviews (when using both the single item rating and agitation composite) and not Black men-led interviews. Also, among targets in Black women-led interviews, several associations between target non-verbal behaviors and higher anti-Black attitudes emerged (e.g., less positivity). Additionally, we found that perceivers, on average, were able to accurately (above chance levels) detect White peoples' anti-Black attitudes from short, silent clips interacting with a Black interviewer. This is evidenced by the mean accuracy correlations for Black and White perceivers, in addition to the vector correlations which show that perceivers inferred higher anti-Black attitudes from the correct pattern of cues displayed by targets. Black and White perceivers did not significantly differ in what cues they inferred higher vs. lower anti-Black attitudes from. Perceivers tended to infer lower anti-Black attitudes when targets smiled less, made a less positive impression and displayed less anger/agitation. White perceivers also inferred higher anti-Black attitudes when participants gazed less at the screen. Importantly, perceivers only inferred higher anti-Black attitudes from less target positivity and more target anger when targets were in Black women-led interviews, as opposed to Black men-led interviews. Perceivers were also more accurate in detecting anti-Black attitudes when targets were in Black women-led interviews.

Implications

The present study showed that anti-Black attitudes can be accurately detected via non-verbal behavior using a thin slice approach and during an interview setting. Furthermore, perceivers can accurately detect these attitudes even when the target is being perceived via computer-mediated communication. This is important to observe since many workplace interactions or interviews are happening over videoconferencing platforms such as Zoom. Black and White perceivers alike were able to accurately detect anti-Black attitudes with similar magnitude, meaning that the burden of targeting and correcting racism does not merely lie on Black individuals. Rather, White individuals are equally, if not more responsible for recognizing and confronting anti-Black attitudes. When White people confront discrimination, this may lead to changes in social norms that are effective at changing and sustaining less racist behavior (Czopp et al., 2006). However, when White people choose to not confront explicitly racist statements and behaviors, this can undermine Black peoples' sense of belonging and leads to mistrust with their White peers (Hurd et al., 2022) and compounds experiences of personal discrimination that leads to poorer mental and physical health and occupational outcomes (Low et al., 2007). Therefore, it is White peoples' shared responsibility to create an anti-racist culture and climate in the workplace and beyond.

A central aspect of the present study was to center Black individuals' perceptions of anti-Black non-verbal cues. Black perceivers rated targets as having higher anti-Black attitudes when they smiled less, made a less positive impression, and appeared less angry (when using both the single item rating and agitation composite). White individuals should be cognizant of how their non-verbal behavior might be perceived by Black people and consciously work to authentically monitor their own behaviors to create a more welcoming and affirming workplace environment for Black individuals.

These results also support the need for an intersectional approach when examining the accurate judgment of detecting non-verbal cues related to anti-Black attitudes. People seem to display more “valid” (e.g., more indicative of anti-Black attitudes) behavioral cues when speaking to Black women compared to Black men. This does not necessarily mean that Black women interviewers received more negative non-verbal behaviors than Black men but rather that targets interacting with Black women interviewers expressed their anti-Black attitudes (whether lower or higher) more genuinely, making it easier for observers to perceive. Targets were also more expressive to Black women than Black men, which likely increased the possibility of anti-Black non-verbal cues being expressed. It is possible that this effect was driven by interviewer gender as people tend to be more expressive toward women compared to men (Roter et al., 2002), however, future research should continue to explore these gender effects in the context of race, perhaps by creating and validating a self-report measure that assesses prejudice specific to Black women motivated by anti-Black sexist attitudes or gendered racism. Black women leaders who experience gendered sexism suffer in that they burnout quicker and have lower self-esteem (see King, 2003; Sudol et al., 2021) than other leaders, so White perceivers should be mindful of others' non-verbal cues that signal anti-Black attitudes toward Black women leaders and confront those who display these cues. Future work should continue to identify non-verbal cues related to anti-Black attitudes toward Black men.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the strengths of the present study, it is not without limitations. This study only focused on cues from a single modality, the dynamic non-verbal face and body channel. However, perceivers of anti-Black attitudes may also be heavily influenced by verbal content, vocal channels, or stable facial features (e.g., facial width-to-height ratio; See Hehman et al., 2013). For example, a target's use of verbal microaggressions may inform perceivers' perceptions of their anti-Black attitudes. Future studies should include the analysis of verbal and vocal content and stable facial features to fully understand the cues most strongly related to self-reported and perceived anti-Black attitudes. In addition, we may not have coded every cue related to anti-Black attitudes due to the medium in which we collected these data (e.g., a shaking foot was off camera). However, this could be addressed in future studies by collecting in person interview data or a wider angle from computer-mediated interactions and using machine learning to predict individuals' anti-Black attitudes, which would lend itself to a completely data-driven approach that would capture a myriad of non-verbal cues. Lastly, it is important for future studies to explore how the accurate detection of anti-Black attitudes, in conjunction with a culture of accountability and zero-tolerance of anti-Black attitudes, can contribute to positive interpersonal outcomes, such as a diverse workplace environment where Black individuals feel valued.

Another limitation is that the present study only observed one type of racism, modern racism (McConahay, 1986). Other types of racism, such as aversive racism, may be related to a different set of non-verbal cues and accuracy may differ. Aversive racism occurs when a person avoids racial discrimination in obvious situations but perpetuates racial bias in more ambiguous situations (Dovidio and Gaertner, 2000; Pearson et al., 2009). For example, they might call out a person in public for using racial slurs, but they may not say anything when they are given a job offer over an equally qualified Black candidate. Therefore, it may be harder to detect aversive racism in a short interaction when perceivers do not see the target faced with an ambiguous situation. Similarly, future studies should also include implicit measures of racism, as these measures have typically been more predictive of anti-Black non-verbal behavior than explicit measures of racism in past studies (Dovidio et al., 1997, 2002; McConnell and Leibold, 2001). Additionally, external and internal motivation to respond without prejudice may dilute the appearance of prejudice, so these constructs should be studied in investigations of how anti-Black attitudes relate to non-verbal behaviors. Additionally, in future research, researchers should administer the racism measure at a separate time from the interview or include distractor tasks along with/before completing the racism measure so as to not impact responses.

Furthermore, the present study employs a binary model of race and racism (specifically by only observing Black and White perceivers), but there are other racial and ethnic groups that should be included in future research, such as the Latino/a/x/e community, Asian/Pacific Islanders, those from the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) region, and multiracial communities. We excluded multiracial participants in the present study because we were underpowered to provide a lens model for this group, so future studies should consider actively recruiting multiracial participants to examine how they perceive White individual's non-verbal behavior and if they are accurate in detecting anti-Black attitudes. Future studies should also test the mechanisms behind accuracy for each racial or ethnic group, as each group (and individual) likely has differing experience with racial socialization and discrimination, leading some to exhibit greater accuracy in perceiving prejudiced attitudes than others. Furthermore, though we identified important differences in the appearance of anti-Black cues and the detection of anti-Black attitudes in women-led vs. men-led interviews, these results need to be replicated in a larger sample.

Lastly, the present study was limited in that the researchers and behavioral coders were predominantly White. It lacked diverse perspectives in its conceptualization and execution. Due to White individuals' position in a racially socialized world, there is the possibility that White privilege clouded the research process (Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva, 2008). Though the authors of this study are committed to anti-racist methodology, we are limited in that there is an embedded bias in seeing the White perspective as our social reality (Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva, 2008). This also means that the global impressions such as hireability, positivity, and anger were rated with a primarily White lens, even though we ensured that coders were blind to the hypothesis of the study and that they were not aware that the study was about race. In addition, most of the experimenters and the actor on the audio recordings were White (with only two sessions being run by non-Black People of Color) and their vocal cues may have been perceived (subconsciously or consciously) by targets and impacted their subsequent non-verbal behavior, though all research assistants were off camera the entire time (Kushins, 2014; Walton and Orlikoff, 1994).

Conclusion

The current series of studies documented how anti-Black attitudes manifest in an interracial videoconferencing interview through a target's non-verbal behaviors and that perceivers (both Black and White) are moderately accurate at perceiving these anti-Black attitudes when only presented with a thin slice of behavior (without sound). For the first time, we identified that more non-verbal impressions of anger were related to both explicit self-reports of anti-Black attitudes and third-party observer judgments of these targets' anti-Black attitudes, and this was especially true when targets were interviewing with a Black woman and not a Black man. This implies that organizations and companies have the capacity to create a workforce that is rid of or is lower in anti-Black attitudes by specifically identifying cues that may signal anti-Black attitudes during interracial interviews or interracial interactions, though this research should be extended to encompass multiple types of anti-Black attitudes and may be more important for identifying racism against Black women compared to Black men. Given the small effect sizes in this current work, it's important to replicate these effects in a separate sample. However, if replicated, an intervention could be created to identify individuals who may need additional anti-racism training as there appear to be systematic non-verbal cues related to explicit racism in the interview context. In addition, for the first time, we identified non-verbal cues that Black individuals perceived as racist in an interracial interaction. This perspective should be centered in racial diversity and inclusion efforts meant to create a welcoming organizational culture.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board: University of Rhode Island. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Partial financial support for the current study was received by the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues. Work on this paper by the second author (MR) was supported by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities K01MD020123. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Multicultural Consultation team in the Department of Psychology at the University of Rhode Island who provided thorough and thoughtful feedback on this manuscript. Their insight was instrumental in assuring this paper aligned with the goals of respectfully and effectively decreasing racism and bias. We are also grateful for the numerous, tireless research assistants who worked on data collection and non-verbal coding for this project. They are Andrew Pinkos, Jennifer Davis, Nicole Rivers, Elena Maturo, Maya Fetcho, Mackenzie Murray, Kendra Mosely, Alec Cole, Maria Taylor, Juliette Dutton, Matthew Kwan, Michelle Stage, Claire Phillips, Paige Roberts, Gianna Mantini, Korinna Simon, Jamie de Souza, Mary Perez, Cori Shooter, Angel Darling, Morgan Stosic, Talia Ducharme, Jacqueline Triglia, Alana Cardona, Christina Carford, Danielle DeWallace, Joanna Stepien, Maggie Fuller, Sara Brouillard, Delaney Farr, Kailee Yunker, and Nifemi Adewumi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note