Introduction

The internet is often considered an amplifier of extremism (e.g., Binder and Kenyon, 2022; Mølmen and Ravndal, 2023). While social media offers unique opportunities for cross-cultural exchange (Yuna et al., 2022), it is increasingly associated with echo chambers and polarization (Cinelli et al., 2021). Skeptics may counter that extremism predates the digital age—after all, the rise of Nazism unfolded without algorithms, and the degree to which social media has a causal role in extremism is debated (e.g., Shaw, 2023). However, this should not overlook the distinctive amplification power of today's social media algorithms, which repeatedly promote divisive content (Rathje et al., 2021; Milli et al., 2025). In this article, we argue that exposure to such content can drive radicalization, especially among youth (Nienierza et al., 2021), either by introducing psychologically vulnerable individuals to extremist propaganda or by strengthening links between existing radical beliefs and political violence (Pauwels and Hardyns, 2018). We illustrate this through the cases of ISIS's use of social media (Awan, 2017) and Russian influence operations (Cosentino, 2020). These examples were selected because (a) they represent high-profile cases of how social media is used to breed extremism1 and (b) to illustrate how both state and non-state actors exploit the digital sphere for extremist agendas in Western democracies in distinct, yet related, ways. Further, we argue that emerging AI technologies exacerbate these threats in potentially unprecedented ways. Finally, we consider the potential of inoculation (McGuire, 1964; van der Linden, 2024) as an intervention against online extremism (Saleh et al., 2023).

ISIS and the internet

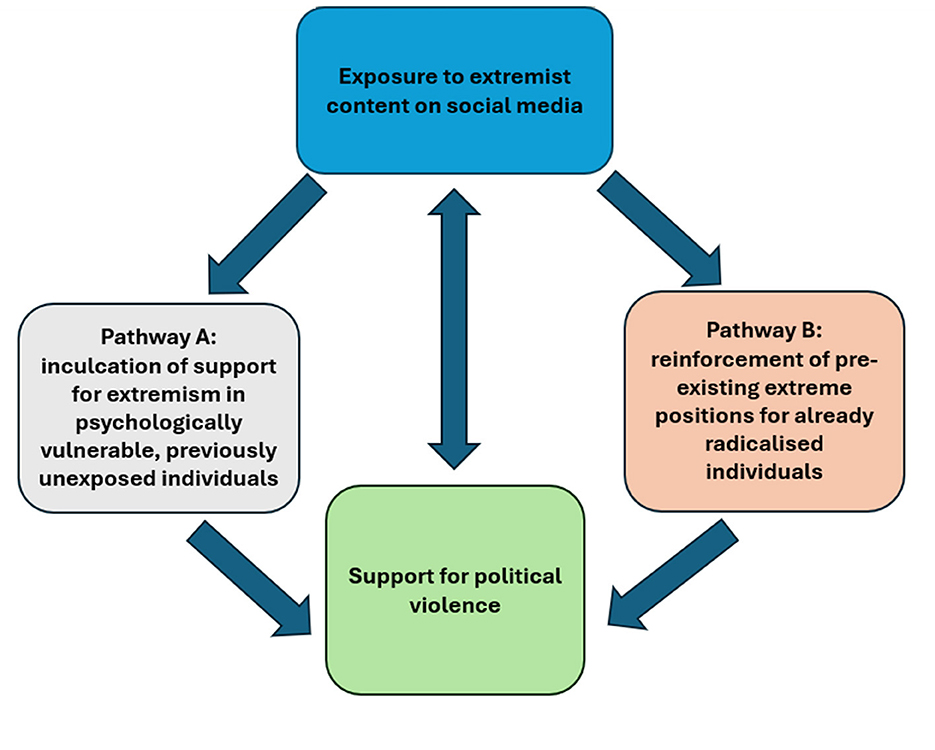

In an analysis of some 6,000 individuals across Arab countries, Piazza and Guler (2021) found that individuals using the internet for political news were more likely to support ISIS. Though the direction of causality remains unclear: individuals already sympathetic to ISIS may engage in confirmation bias (Klayman, 1995; Modgil et al., 2024)—especially in the restricted media contexts of Arab countries, where social media has long been utilized by dissidents (Wolfsfeld et al., 2013). These pathways are not mutually exclusive either: social media has the capacity both to seed extremist beliefs and reinforce existing ones (see Figure 1), both of which may increase support for political violence (Hassan et al., 2018; Pauwels and Hardyns, 2018) The apparent success of ISIS is perhaps unsurprising given their well-established propaganda strategies (Lieberman, 2017). They were early adopters of YouTube and their online presence spanned deep-web magazines, violent high-definition videos, and exploitation of platforms such as Twitter (Colas, 2017; Lieberman, 2017; Venkatesh et al., 2020). In 2014, they launched an app automatically sharing pro-ISIS tweets with users, prompting Iraq's government to block Twitter (Irshaid, 2014). ISIS often uses social networks to recruit by appealing to belonging, purpose, and identity (Ponder and Matusit, 2017) and romanticizing life as an ISIS fighter (Awan, 2017).

Figure 1. A dual-pathway model of social media-based radicalization. We recognize that causality can be bi-directional in mutually reinforcing loops, e.g., when newfound support for extremism is reinforced by later (algorithmic) exposure to extremist content on social media. Similarly, existing support for political violence can lead people to seek out extremist content which further solidifies violent intent.

Why was social media especially effective? One contributing factor is the enablement of an unprecedented mass distribution of content (Aïmeur et al., 2023) For example, Alfifi et al. (2019) compiled a dataset of 17 million pro-ISIS tweets, with over 71 million retweets. It is difficult to imagine how a group in Syria and Iraq could reach such vast audiences before the digital era. Thus, in line with our dual-pathway model (see Figure 1), this may initiate support for extremist groups in some (i.e., discovering ISIS propaganda online) and reinforce existing sympathies in others (through greater exposure to pro-ISIS content).

Repeated pro-extremist content also exploits the illusory truth effect, where repeated claims seem more accurate even if false (Fazio et al., 2015; Vellani et al., 2023; Udry and Barber, 2024) and the high visibility of extremists can trigger a “false consensus effect,” leading individuals to overestimate public support for extreme views (Wojcieszak, 2011; Luzsa and Mayr, 2021). Such tactics are desirable for terrorist organizations that are, in reality, deeply unpopular (Poushter, 2015) as social cues enhance the perceived credibility of misleading narratives (Traberg et al., 2024).

Another aspect to consider is algorithms' negativity bias: Milli et al. (2025); Watson et al. (2024) showed that Twitter's algorithm amplifies divisive content far more than users' stated preferences (see also (Rathje et al., 2024). This suits a group such as ISIS, whose propaganda was deliberately designed to shock (Venkatesh et al., 2020). As well as attracting attention, such content potentially fosters desensitization to violence (Bushman and Anderson, 2009; Krahé et al., 2011).

Of course, social media cannot explain radicalization alone. Individual factors such as uncertainty intolerance, perceived injustice, isolation, and a quest for significance likely play key roles (Knapton, 2014; Jasko et al., 2017; Trip et al., 2019). But social media gives extremist organizations unique opportunities to appeal to individuals with these characteristics.

In short, ISIS's digital strategy supports the idea that social media can play a determining role in both inculcating and reinforcing extremist positions. In the next section we argue that state actors, too, have weaponized these platforms in distinct yet similar ways.

Social media and influence operations: the case of Russian-backed disinformation

Although adversaries in international politics have always engaged in covert subversion campaigns against each other (e.g., O'Brien, 1995), social media has opened an entirely new arena for such activity. In discussing ISIS's mass proliferation of content, observers may note some parallels with Russia's “firehose of falsehood” strategy (Paul and Matthews, 2016), most recently deployed in Ukraine (Karalis, 2024; Roozenbeek, 2024). This strategy rapidly spreads misinformation across channels to weaken trust in reliable sources. An example is the Doppelgänger campaign, where Russian operatives cloned Western news sites to spread misinformation about Ukraine (Alaphilippe et al., 2022). The effectiveness of such tactics is debated (Bail et al., 2020; Eady et al., 2023), as crafting effective propaganda is harder for Russia in the West than at home, where it controls the information sphere (Kaye, 2022). Nevertheless, high volume output from the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA) predicted polling figures for Trump (Ruck et al., 2019). This is partially explainable by psychological research. Falsehoods often have more reach than accurate information online, in part because they tend to be more novel, polarizing, and emotionally engaging (Vosoughi et al., 2018; McLoughlin et al., 2024; Kauk et al., 2025). Individuals may then continue believing misinformation even after correction, a phenomenon known as the continued influence effect (Johnson and Seifert, 1994; Lewandowsky et al., 2012). Moreover, Russian propaganda tends to feign multiple source-origins (Paul and Matthews, 2016) to appear more convincing (Harkins and Petty, 1987). Russia exploits this principle through coordinated bots and fake accounts—uniquely enabled by social media (Geissler et al., 2023). By flooding the digital environment with misinformation, Russia exploits cognitive biases entrenching it, including black-and-white thinking (EUvsDisinfo, 2017), tactics long linked to extremism (e.g., Roberts-Ingleson and McCann, 2023; Enders et al., 2024). Russian propaganda also tends to create the impression that it comes from multiple sources (Paul and Matthews, 2016) because arguments appear more convincing when repeated by independent sources (Harkins and Petty, 1987). Russia exploits this principle through coordinated state media, bots, and fake accounts, enabled by social media (Geissler et al., 2023). A key difference between a terrorist organization (ISIS) and state-actor (Russia), however, is strategy. Whereas ISIS produces self-promotional propaganda, Russian operations often covertly exploit internal divisions within adversarial societies by spreading misinformation (Karlsen, 2019). Lacking legitimacy, terrorist groups may favor attention-grabbing to win support (e.g., through shock; Venkatesh et al., 2020), while state-actors can afford more subtle strategies. That both strategies flourish underscores social media's ability to enable extremist manipulation across diverse actors. Some individuals may be exposed online to Russian misinformation they may otherwise never encounter (i.e., Pathway A), given its unique prevalence online (Muhammed and Mathew, 2022), while others may strengthen existing radical beliefs through confirmation bias toward already internalized misinformation (i.e., Pathway B; Modgil et al., 2024).

A clear example of Russia's attempt to stir division came during the 2016 U.S. election, when Russia's Internet Research Agency ran thousands of fake American accounts. These accounts amplified racial, anti-immigration, and conspiratorial narratives, polarizing both left-and right-leaning audiences (Howard et al., 2018; Simchon et al., 2022; Vićić and Gartzke, 2024).

Russian operators also organized U.S. protests on race and vaccination (Aceves, 2019; Broniatowski et al., 2018), exploiting social media anonymity to pose as in-group members—a clever tactic given in-group messages are deemed more persuasive and trustworthy (Mackie et al., 1992; Traberg et al., 2024; Im et al., 2020). Using fake accounts, they more effectively spread misinformation and fuelled polarization, which can heighten extremism (Mølmen and Ravndal, 2023). From a social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979) perspective, heightened polarization sharpens the psychological boundaries between in-groups and out-groups, and can increase the likelihood of violence against outgroups (Doosje et al., 2016). Russia—known for ties with far-right groups (Pantucci, 2023)—fuelling these dynamics further illustrates how social media emboldens extremism.

Future risks posed by AI

As extremist groups and state actors weaponize social media, the rise of AI threatens to amplify these risks at a scale that was previously unachievable. For example, in addition to the ability for automated algorithms to promote divisive and extremist content (Milli et al., 2025; see also Burton, 2023), Baele et al. (2024) found that LLM-generated texts mimicking extremist groups appeared so credible that it even fooled academic experts. Extremists may also exploit chatbots. By simulating human-like conversation, AI chatbots can foster a sense of direct personal connection with users (e.g., Zimmerman et al., 2024). Since recruitment relies on trust (Saleh et al., 2021, 2023), AI chatbots could act as scalable recruiters, tailoring narratives to users' vulnerabilities (Houser and Dong, 2025; Farber, 2025). By mimicking in-group cues (Baele et al., 2024) and appealing to identity biases (Hu et al., 2025), they could ‘befriend' users and exploit principles of persuasion (Cialdini, 2008), potentially more effectively than social media due to their personal, conversational nature. The threat of extremist chatbots was raised by the UK Government's review of terrorism legislation in 2024 (Vallance and Rahman-Jones, 2024).

Lastly, LLMs can now create persuasive propaganda (Wack et al., 2025a), often as or more persuasive than human-written propaganda (Goldstein et al., 2024) which can then be micro-targeted at users. A recent experiment estimates that anywhere between roughly 2,500 and 11,000 individuals can be persuaded for every 100,000 targeted (Simchon et al., 2024), which is meaningful given that elections are often decided on small margins and these methods are already leveraged for propaganda campaigns (Wack et al., 2025b). These capabilities could strengthen both our proposed pathways of online extremism (Figure 1). They could inculcate extremist beliefs in new audiences through tailored exposure, potentially microtargeting individuals with traits linked to radicalization (Simchon et al., 2024), and reinforce them in existing radicals though personalized persuasion validating existing beliefs (e.g., Du, 2025).

Inoculation as a pre-emptive intervention

Although there is considerable cause for concern regarding the ability for extremist organizations to exploit social media and emerging AI technologies to amplify the spread of harmful narratives, some respite may be found in the concurrent development of psychological interventions against such risks. One promising approach is rooted in inoculation theory (McGuire, 1964; Van der Linden, 2023; van der Linden, 2024). This “pre-bunking” approach (Lewandowsky and van der Linden, 2021) typically forewarns individuals of potential manipulation and offers a “refutational preemption”— i.e., exposure to a weakened version of an extremist claim alongside a clear refutation, exposing the extremist playbook (Van der Linden, 2023; Roozenbeek et al., 2022). Akin to a psychological vaccine, this process builds cognitive resistance, making individuals less susceptible to similar misinformation in the future (Van der Linden, 2023; van der Linden, 2024). For example, Saleh et al. (2021, 2023) tested an inoculation game in former ISIS-held regions of Iraq, where participants role-played recruiters. Players exposed to simulated extremist recruitment tactics online later showed greater recognition of and resistance to manipulation. Similarly, Lewandowsky and Yesilada (2021) found that inoculation videos reduced belief in and sharing of both Islamist and anti-Islam disinformation, while Braddock (2022) found that inoculation reduced the credibility of left-and-right extremist groups and lowered intentions to support them. This underscores inoculation's potential, which has recently been evaluated at scale on YouTube (Roozenbeek et al., 2022) and in meta-analyses (Simchon et al., 2025).

Inoculation may also potentially protect against influence operations. Ziemer et al. (2024) tested an inoculation intervention against Russian war-related misinformation online among ethnic Russians in Germany, finding that it enhanced participants' ability to detect misinformation. The ability for inoculation to work against such social identity-salient persuasion attempts remains, however, relatively understudied. Moreover, inoculation faces some challenges as a counter-extremism tool. Designed as a pre-emptive intervention (McGuire, 1964), it may be less effective once individuals are already radicalized, i.e., pathway B in our model (though “therapeutic inoculation” may help address internalized extremist narratives; (Compton, 2020; van der Linden et al., 2017). Reaching vulnerable groups also remains challenging. While successful in former ISIS-held areas (Saleh et al., 2021, 2023), such efforts are harder in regions where extremists remain in charge. Moreover, while Ziemer et al. (2024) found that inoculation reduced belief in Russian misinformation, it did not alter their attitudes toward the war, suggesting identity-salient views may be more resistant (see also Van Bavel and Pereira, 2018). Nonetheless, evidence that inoculation counters extremist narratives warrants further research on its potential to reduce group radicalization (Bierwiaczonek et al., 2025).

Conclusion

Overall, while extremist ideologies are not new, we illustrate how digital platforms have transformed the landscape of extremism: non-state and state actors with distinct aims exploit algorithms to spread their narratives at unprecedented speed and scale. This may both initiate radicalization and deepen existing extremism, in mutually reinforcing pathways to support extremist violence (Figure 1). These dynamics may be magnified by AI technologies. Yet, psychological research also highlights inoculation theory as a promising intervention to build resilience against extremist manipulation (Saleh et al., 2021, 2023; Lewandowsky and Yesilada, 2021), but needs further testing in identity-salient contexts. Going forward, psychologists, policymakers, and technology companies must work together to anticipate and mitigate the evolving threat landscape. This will require further research into the psychology of extremism in the digital age and greater investment in evidence-based interventions. For example, psychological insights could be integrated into counter-extremism strategies such as algorithmic regulation (Whittaker et al., 2021) and the UK's PREVENT program (Montasari, 2024). Adopting inoculation as a counter-extremism strategy could help make PREVENT more preventative, as it currently still relies on individual referrals. Likewise, education curricula could build early digital and AI literacy against extremism, e.g., by incorporating interactive games into classrooms, as is already done in Finland (Kivinen, 2023). Doing so could bolster the ability of democracies to withstand the challenges of increasingly digitalized forms of extremism.

Author contributions

NL-D: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SL: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) for their support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor ES declared a past co-authorship with the author SL.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^We note that there is no consensus definition of extremism, whereas some have defined extremism as “holding radical views that depart from societal norms” (Ismail et al., 2025), more psychological definitions have focused on motivational imbalance where extremism emerges when one need dominates all others (Kruglanski et al., 2021).

References

Aceves, W. J. (2019). Virtual hatred: how Russia tried to start a race war in the United States. Michigan J. Race Law 24, 177–250. doi: 10.36643/mjrl.24.2.virtual

Aïmeur, E., Amri, S., and Brassard, G. (2023). Fake news, disinformation and misinformation in social media: a review. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 13:30. doi: 10.1007/s13278-023-01028-5

Alaphilippe, A., Machado, G., Miguel, R., and Poldi, F. (2022). Doppelganger: Media Clones Serving Russian Propaganda. EU DisinfoLab. Available online at: https://www.disinfo.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2022/09/Doppelganger-1.pdf (Accessed November 6, 2025).

Alfifi, M., Kaghazgaran, P., Caverlee, J., and Morstatter, F. (2019). A large-scale study of ISIS social media strategy: community size, collective influence, and behavioral impact. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 13, 58–67. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v13i01.3209

Awan, I. (2017). Cyber-extremism: isis and the power of social media. Society 54, 138–149. doi: 10.1007/s12115-017-0114-0

Baele, S. J., Naserian, E., and Katz, G. (2024). Is AI-generated extremism credible? Experimental evidence from an expert survey. Terror. Polit. Violence 37, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2024.2380089

Bail, C. A., Guay, B., Maloney, E., Combs, A., Hillygus, D. S., Merhout, F., et al. (2020). Assessing the Russian internet research agency's impact on the political attitudes and behaviors of American twitter users in late 2017. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 117, 243–250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906420116

Bierwiaczonek, K., van Prooijen, J. W., van der Linden, S., and Rottweiler, B. (2025). “Conspiracy Theories and violent extremism,” in The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Violent Extremism, eds. M. Obaidi and J. Kunst, (166–184).

Binder, J. F., and Kenyon, J. (2022). Terrorism and the internet: how dangerous is online radicalization? Front. Psychol. 13:997390. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.997390

Braddock, K. (2022). Vaccinating against hate: using attitudinal inoculation to confer resistance to persuasion by extremist propaganda. Terror. Polit. Violence 34, 240–262. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2019.1693370

Broniatowski, D. A., Jamison, A. M., Qi, S., AlKulaib, L., Chen, T., Benton, A., Quinn, S. C., and Dredze, M. (2018). Weaponized health communication: Twitter bots and Russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. Am. J. Public Health 108, 1378–1384. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567

Burton, J. (2023). Algorithmic extremism? The securitization of artificial intelligence (AI) and its impact on radicalism, polarization and political violence. Technol. Soc. 75:102262. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102262

Bushman, B. J., and Anderson, C. A. (2009). Comfortably numb: desensitizing effects of violent media on helping thers. Psychol. Sci. 20, 273–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02287.x

Cinelli, M., De Francisci Morales, G., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., and Starnini, M. (2021). The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 118:e2023301118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2023301118

Colas, B. (2017). What does Dabiq do? ISIS hermeneutics and organizational fractures within Dabiq magazine. Stud. Conflict Terror. 40, 173–190. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2016.1184062

Compton, J. (2020). Prophylactic versus therapeutic inoculation treatments for resistance to Influence. Commun. Theor. 30, 330–343. doi: 10.1093/ct/qtz004

Cosentino, G. (2020). “Polarize and conquer: Russian influence operations in the United States,” in Social Media and the Post-Truth World Order (pp. 33–57). Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-43005-4_2

Doosje, B., Moghaddam, F. M., Kruglanski, A. W., De Wolf, A., Mann, L., and Feddes, A. R. (2016). Terrorism, radicalization and de-radicalization. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 11, 79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.008

Du, Y. (2025). Confirmation bias in generative ai chatbots: Mechanisms, risks, mitigation strategies, and future research directions. arXiv [Preprint]. arXiv:2504.09343. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.09343 (accessed 6 November 2025).

Eady, G., Paskhalis, T., Zilinsky, J., Bonneau, R., Nagler, J., Tucker, J. A., et al. (2023). Exposure to the Russian internet research agency foreign influence campaign on Twitter in the 2016 US election and its relationship to attitudes and voting behavior. Nat. Commun. 14:62. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-35576-9

Enders, A., Klofstad, C., and Uscinski, J. (2024). The relationship between conspiracy theory beliefs and political violence. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinform. Rev. 5:e100163 doi: 10.37016/mr-2020-163

Farber, S. (2025). AI-enabled terrorism: a strategic analysis of emerging threats and countermeasures in global security. J. Strat. Secur. 18, 320–344. doi: 10.5038/1944-0472.18.3.2377

Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N. M., Payne, B. K., and Marsh, E. J. (2015). Knowledge does not protect against illusory truth. J. Exp. Psychol. Gener. 144, 993–1002. doi: 10.1037/xge0000098

Geissler, D., Bär, D., Pröllochs, N., and Feuerriegel, S. (2023). Russian propaganda on social media during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. EPJ Data Sci. 12:35. doi: 10.1140/epjds/s13688-023-00414-5

Goldstein, J. A., Chao, J., Grossman, S., Stamos, A., and Tomz, M. (2024). How persuasive is AI generated propaganda? PNAS Nexus 3:pgae034. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae034

Harkins, S. G., and Petty, R. E. (1987). Information utility and the multiple source effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52:260. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.2.260

Hassan, G., Brouillette-Alarie, S., Alava, S., Frau-Meigs, D., Lavoie, L., Fetiu, A., et al. (2018). Exposure to extremist online content could lead to violent radicalization: a systematic review of empirical evidence. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 12, 71–88. doi: 10.3233/DEV-170233

Houser, T., and Dong, B. (2025). The convergence of artificial intelligence and terrorism: a systematic review of literature. Stud. Conflict Terror. 48, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2025.2527608

Howard, P. N., Ganesh, B., Liotsiou, D., Kelly, J., and François, C. (2018). The IRA, Social Media and Political Polarization in the United States, 2012-2018. Oxford: Project on Computational Propaganda.

Hu, T., Kyrychenko, Y., Rathje, S., Collier, N., van der Linden, S., Roozenbeek, J., et al. (2025). Generative language models exhibit social identity biases. Nat. Comput. Sci. 5, 65–75. doi: 10.1038/s43588-024-00741-1

Im, J., Chandrasekharan, E., Sargent, J., Lighthammer, P., Denby, T., Bhargava, A., et al. (2020). “Still out there: modeling and identifying Russian troll accounts on twitter,” in 12th ACM Conference on Web Science, 1–10.

Ismail, A. M., Jamir Singh, P. S., and Mujani, W. K. (2025). A systematic review: unveiling the complexity of definitions in extremism and religious extremism. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12:1297. doi: 10.1057/s41599-025-05685-z

Jasko, K., LaFree, G., and Kruglanski, A. (2017). Quest for significance and violent extremism: the case of domestic radicalization. Polit. Psychol. 38, 815–831. doi: 10.1111/pops.12376

Johnson, H. M., and Seifert, C. M. (1994). Sources of the continued influence effect: when misinformation in memory affects later inferences. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 20, 1420–1436. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.20.6.1420

Karalis, M. (2024). Fake leads, defamation and destabilization: how online disinformation continues to impact Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Intell. Natl. Secur. 39, 515–524. doi: 10.1080/02684527.2024.2329418

Karlsen, G. H. (2019). Divide and rule: ten lessons about Russian political influence activities in Europe. Palgrave Commun. 5:19. doi: 10.1057/s41599-019-0227-8

Kauk, J., Humprecht, E., Kreysa, H., and Schweinberger, S. R. (2025). Large-scale analysis of online social data on the long-term sentiment and content dynamics of online (mis) information. Comput. Human Behav. 165:108546. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2024.108546

Kaye, D. (2022). Online propaganda, censorship and human rights in Russia's war against reality. AJIL Unbound 116, 140–144. doi: 10.1017/aju.2022.24

Kivinen, K. (2023). In Finland, we make each schoolchild a scientist. Issues Sci. Technol. 29, 41–42. doi: 10.58875/FEXX4401

Klayman, J. (1995). Varieties of confirmation bias. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation (Vol. 32) (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 385–418.

Knapton, H. M. (2014). The recruitment and radicalisation of western citizens: Does ostracism have a role in homegrown terrorism? J. Eur. Psychol. Stud. 5, 38–48. doi: 10.5334/jeps.bo

Krahé, B., Möller, I., Huesmann, L. R., Kirwil, L., Felber, J., Berger, A., et al. (2011). Desensitization to media violence: links with habitual media violence exposure, aggressive cognitions, and aggressive behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 100, 630–646. doi: 10.1037/a0021711

Kruglanski, A. W., Szumowska, E., Kopetz, C. H., Vallerand, R. J., and Pierro, A. (2021). On the psychology of extremism: how motivational imbalance breeds intemperance. Psychol. Rev. 128, 264–289. doi: 10.1037/rev0000260

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., and Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 13, 106–131. doi: 10.1177/1529100612451018

Lewandowsky, S., and van der Linden, S. (2021). Countering misinformation and fake news through inoculation and prebunking. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 32, 348–384. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2021.1876983

Lewandowsky, S., and Yesilada, M. (2021). Inoculating against the spread of Islamophobic and radical-Islamist disinformation. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 6:57. doi: 10.1186/s41235-021-00323-z

Lieberman, A. V. (2017). Terrorism, the internet, and propaganda: a deadly combination. J. Natl. Secur. Law Policy 9:95.

Luzsa, R., and Mayr, S. (2021). False consensus in the echo chamber: exposure to favorably biased social media news feeds leads to increased perception of public support for own opinions. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 15:3. doi: 10.5817/CP2021-1-3

Mackie, D. M., Gastardo-Conaco, M. C., and Skelly, J. J. (1992). Knowledge of the advocated position and the processing of in-group and out-group persuasive messages. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 18, 145–151. doi: 10.1177/0146167292182005

McGuire, W. J. (1964). “Some contemporary aproaches,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 1) (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 191–229.

McLoughlin, K. L., Brady, W. J., Goolsbee, A., Kaiser, B., Klonick, K., Crockett, M. J., et al. (2024). Misinformation exploits outrage to spread online. Science. 386, 991–996. doi: 10.1126/science.adl2829

Milli, S., Carroll, M., Wang, Y., Pandey, S., Zhao, S., Dragan, A. D., et al. (2025). Engagement, user satisfaction, and the amplification of divisive content on social media. PNAS Nexus 4:pgaf062. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf062

Modgil, S., Singh, R. K., Gupta, S., and Dennehy, D. (2024). A confirmation bias view on social media induced polarisation during COVID-19. Inf. Syst. Front. 26, 417–441. doi: 10.1007/s10796-021-10222-9

Mølmen, N. G., and Ravndal, J. A. (2023). Mechanisms of online radicalisation: how the internet affects the radicalisation of extreme-right lone actor terrorists. Behav. Sci. Terror. Polit. Aggress. 15, 463–487. doi: 10.1080/19434472.2021.1993302

Montasari, R. (2024). “Assessing the effectiveness of uk counter-terrorism strategies and alternative approaches,” in Cyberspace, Cyberterrorism and the International Security in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, ed. R. Montasari (Berlin: Springer International Publishing), 27–50.

Muhammed, T. S., and Mathew, S. K. (2022). The disaster of misinformation: a review of research in social media. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 13, 271–285. doi: 10.1007/s41060-022-00311-6

Nienierza, A., Reinemann, C., Fawzi, N., Riesmeyer, C., and Neumann, K. (2021). Too dark to see? Explaining adolescents' contact with online extremism and their ability to recognize it. Inform. Commun. Soc. 24, 1229–1246. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1697339

O'Brien, K. A. (1995). Interfering with civil society: CIA and KGB covert political action during the Cold War. Int. J. Intell. CounterIntelligence 8, 431–456. doi: 10.1080/08850609508435297

Paul, C., and Matthews, M. (2016). The Russian “Firehose of Falsehood” Propaganda Model: Why It Might Work and Options to Counter It. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Pauwels, L. J. R., and Hardyns, W. (2018). Endorsement for extremism, exposure to extremism via social media and self-reported political/religious aggression. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 12, 51–69. doi: 10.3233/DEV-170229

Piazza, J. A., and Guler, A. (2021). The online caliphate: internet usage and ISIS support in the Arab World. Terror. Polit. Violence 33, 1256–1275. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2019.1606801

Ponder, S., and Matusit, J. (2017). Examining ISIS online recruitment through relational development theory. Connect. Q. J. 16, 35–50. doi: 10.11610/Connections.16.4.02

Poushter, J. (2015). In nations with significant Muslim populations, much disdain for ISIS. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center.

Rathje, S., Robertson, C., Brady, W. J., and Van Bavel, J. J. (2024). People think that social media platforms do (but should not) amplify divisive content. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 19, 781–795. doi: 10.1177/17456916231190392

Rathje, S., Van Bavel, J. J., and Van Der Linden, S. (2021). Out-group animosity drives engagement on social media. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 118:e2024292118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2024292118

Roberts-Ingleson, E. M., and McCann, W. S. (2023). The link between misinformation and radicalisation: current knowledge and areas for future inquiry. Perspect. Terror. 17, 36–49. doi: 10.19165/LWPQ5491

Roozenbeek, J. (2024). Propaganda and Ideology in the Russian–Ukrainian war (1st Edn.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roozenbeek, J., Van Der Linden, S., Goldberg, B., Rathje, S., and Lewandowsky, S. (2022). Psychological inoculation improves resilience against misinformation on social media. Sci. Adv. 8:eabo6254. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abo6254

Ruck, D. J., Rice, N. M., Borycz, J., and Bentley, R. A. (2019). Internet research agency twitter activity predicted 2016 US election polls. First Monday 24. doi: 10.5210/fm.v24i7.10107

Saleh, N., Makki, F., Van Der Linden, S., and Roozenbeek, J. (2023). Inoculating against extremist persuasion techniques—Results from a randomised controlled trial in post-conflict areas in Iraq. Adv. Psychol. 1, 1–21. doi: 10.56296/aip00005

Saleh, N. F., Roozenbeek, J. O. N., Makki, F. A., McClanahan, W. P., and Van Der Linden, S. (2021). Active inoculation boosts attitudinal resistance against extremist persuasion techniques: a novel approach towards the prevention of violent extremism. Behav. Public Policy 8, 548–571. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2020.60

Shaw, A. (2023). Social media, extremism, and radicalization. Sci. Adv. 9:eadk2031. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adk2031

Simchon, A., Brady, W. J., and Van Bavel, J. J. (2022). Troll and divide: the language of online polarization. PNAS Nexus 1:pgac019. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac019

Simchon, A., Edwards, M., and Lewandowsky, S. (2024). The persuasive effects of political microtargeting in the age of generative artificial intelligence. PNAS Nexus 3:pgae035. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae035

Simchon, A., Zipori, T., Teitelbaum, L., Lewandowsky, S., and Van Der Linden, S. (2025). A signal detection theory meta-analysis of psychological inoculation against misinformation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 67, 102194.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds. W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Colen), 33–47.

Traberg, C. S., Harjani, T., Roozenbeek, J., and Van Der Linden, S. (2024). The persuasive effects of social cues and source effects on misinformation susceptibility. Sci. Rep. 14:4205. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-54030-y

Trip, S., Bora, C. H., Marian, M., Halmajan, A., and Drugas, M. I. (2019). Psychological mechanisms involved in radicalization and extremism. A rational emotive behavioral conceptualization. Front. Psychol. 10:437. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00437

Udry, J., and Barber, S. J. (2024). The illusory truth effect: a review of how repetition increases belief in misinformation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 56:101736. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101736

Vallance, C., and Rahman-Jones, I. (2024). Urgent need for terrorism AI laws, warns think tank. London: BBC News.

Van Bavel, J. J., and Pereira, A. (2018). The partisan brain: an identity-based model of political belief. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.004

Van der Linden, S. (2023). Foolproof: Why Misinformation Infects Our Minds and How to Build Immunity. New York, NY: WW Norton and Company.

van der Linden, S. (2024). Countering misinformation through psychological inoculation. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 69, 1–58. doi: 10.1016/bs.aesp.2023.11.001

van der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Rosenthal, S., and Maibach, E. (2017). Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change. Global Challeng. 1:1600008. doi: 10.1002/gch2.201600008

Vellani, V., Zheng, S., Ercelik, D., and Sharot, T. (2023). The illusory truth effect leads to the spread of misinformation. Cognition 236:105421. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2023.105421

Venkatesh, V., Podoshen, J. S., Wallin, J., Rabah, J., and Glass, D. (2020). Promoting extreme violence: visual and narrative analysis of select ultraviolent terror propaganda videos produced by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in 2015 and 2016. Terror. Polit. Violence 32, 1753–1775. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2018.1516209

Vićić, J., and Gartzke, E. (2024). Cyber-enabled influence operations as a ‘center of gravity'in cyberconflict: the example of Russian foreign interference in the 2016 US federal election. J. Peace Res. 61, 10–27. doi: 10.1177/00223433231225814

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., and Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science 359, 1146–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.aap9559

Wack, M., Ehrett, C., Linvill, D., and Warren, P. (2025a). Generative propaganda: evidence of AI's impact from a state-backed disinformation campaign. PNAS Nexus 4:pgaf083. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf083

Wack, M., Schafer, J. S., Kennedy, I., Beers, A., Spiro, E. S., Starbird, K., et al. (2025b). Legislating uncertainty: election policies and the amplification of misinformation. Policy Stud. J. psj.70054. doi: 10.1111/psj.70054. [Epub ahead of print].

Watson, J., van der Linden, S., Watson, M., and Stillwell, D. (2024). Negative online news articles are shared more to social media. Sci. Rep. 14:21592. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-71263-z

Whittaker, J., Looney, S., Reed, A., and Votta, F. (2021). Recommender systems and the amplification of extremist content. Internet Policy Rev. 10, 1–29. doi: 10.14763/2021.2.1565

Wojcieszak, M. E. (2011). Computer-mediated false consensus: radical online groups, social networks and news media. Mass Commun. Soc. 14, 527–546. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2010.513795

Wolfsfeld, G., Segev, E., and Sheafer, T. (2013). Social media and the Arab spring: politics comes first. Int. J. Press Polit. 18, 115–137. doi: 10.1177/1940161212471716

Yuna, D., Xiaokun, L., Jianing, L., and Lu, H. (2022). Cross-cultural communication on social media: review from the perspective of cultural psychology and neuroscience. Front. Psychol. 13:858900. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.858900

Ziemer, C-. T., Schmid, P., Betsch, C., and Rothmund, T. (2024). Identity is key, but Inoculation helps—how to empower Germans of Russian descent against pro-Kremlin disinformation. Adv. Psychol. 2:aip00015. doi: 10.56296/aip00015

Keywords: extremism, intergroup conflict, social media, inoculation, AI

Citation: Lavie-Driver N and van der Linden S (2025) Social media, AI, and the rise of extremism during intergroup conflict. Front. Soc. Psychol. 3:1711791. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2025.1711791

Received: 23 September 2025; Accepted: 30 October 2025;

Published: 19 November 2025.

Edited by:

Ewa Szumowska, Jagiellonian University, PolandReviewed by:

Kais Al Hadrawi, Al-Furat Al-Awsat Technical University, IraqCopyright © 2025 Lavie-Driver and van der Linden. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Neil Lavie-Driver, bmlsMjNAY2FtLmFjLnVr

Neil Lavie-Driver

Neil Lavie-Driver Sander van der Linden

Sander van der Linden