- Department of Physiotherapy, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

Introduction: Female stroke survivors experience considerable vulnerabilities and existential concerns, shaped by sociocultural factors and gender roles, which heighten stroke morbidity and limit community reintegration. Yet, the existential concerns of female stroke survivors in Nigeria, and their relationships with psychological depression and community reintegration have not been explored.

Methods: A mixed-methods study was conducted among female stroke survivors recruited from selected hospitals in South-west, Nigeria. Community integration questionnaire, Existential concerns questionnaire, and the depression subscale of the Hospital anxiety and depression scale were used to assess community reintegration, existential concerns, and psychological depression, respectively. Six purposively selected female stroke survivors participated in a focus group discussion (FGD). Quantitative data were analyzed using Chi-square test at p < 0.05, while qualitative data were thematically analyzed.

Results: Seventy-five female stroke survivors aged 64.07 ± 14.03 years participated in the survey. The mean community reintegration, existential concerns and psychological depression scores were 12.24 ± 2.95, 9.77 ± 5.52, and 13.84 ± 4.71, respectively. The majority (n = 61; 81.3%) of the participants had a low level of community integration. Forty-seven (62.7%) reported a moderate level of existential concerns, while 32(42.7%) had psychological depression. There was a significant association between community reintegration and psychological depression (p = 0.02), and between existential concerns and psychological depression (p < 0.01). However, there was no association between community reintegration and existential concerns (p = 0.08). The five emergent themes from the FGD were: perception of stroke as a devastating condition; role disruption and loss of autonomy in the home, isolation and stigmatization in society, inadequate spousal support and sexual intimacy, work-related and financial concerns.

Conclusion: Existential concerns among participants were mostly related to social and family roles and were associated with poor emotional and mental wellbeing. Addressing these concerns through integrated care, delivered by a coordinated multidisciplinary team, could enhance emotional and mental wellbeing, and promote community reintegration among female stroke survivors.

1 Background

Stroke is the third leading cause of death and a major cause of disability among women (Petrea et al., 2009). Female stroke survivors often experience worse functional outcomes than males, attributable to older age at onset, poorer pre-stroke functional and health status, higher comorbidity rate, limited social support, and greater dependency in activities of daily living (Liljehult et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2024; Rizzo et al., 2024). These vulnerabilities extend beyond physical functioning to psychosocial and existential concerns, with female stroke survivors facing lower levels of community reintegration, heightened risks of depression and unique gender-related challenges (Hamzat et al., 2014; Witt et al., 2024). The objectives of this study were to explore the existential concerns of female stroke survivors in Nigeria, and to investigate the associations among community reintegration, existential concerns and psychological depression. We hypothesized that female stroke survivors with greater existential concerns would exhibit higher levels of psychological depression and lower levels of community reintegration.

Community reintegration encompasses important aspects of post-stroke life, including leisure and social participation, economic and residential integration, employment stability, familial roles, coping mechanisms and independent living (Akosile et al., 2016). It is an important component of stroke recovery However, inadequate support systems, isolation and restrictive gender expectations often impede women's reintegration into the community, deepening the impact of stroke beyond physical disability to existential concerns (Walsh et al., 2015; Thompson and Ryan, 2019).

Existential concerns, such as death, isolation, loss of identity and autonomy, and the search for meaning, can interfere with mental health, exacerbate loneliness and intensify uncertainty (Kretschmer and Storm, 2018; Vail et al., 2020). Many female stroke survivors struggle with role reversal trauma as they transition from caregivers to care recipients, a process worsened by cultural expectations and traditional gender roles (Nettles, 2024; Pathan et al., 2024; Wan et al., 2024). These concerns heighten psychological distress, as women worry about loss of control and diminished autonomy (Agbola et al., 2020), and have been associated with post-stroke depression (PSD) (Kingau et al., 2024).

Depression is a common and debilitation complication of stroke. Dymm et al. (2024) reported that 31.7% of women with small vessel stroke experienced PSD compared to 6.3% of controls. Evidence suggests high rates of depressive symptoms among female stroke survivors in Nigeria, particularly those with severe disabilities and post-stroke complications (Bakare et al., 2024). Female gender itself has been identified as an important risk factor for PSD (Harini and Suraweera, 2023), alongside low level of education, dissatisfaction with life, poor social support and pain (Xiao et al., 2024). PSD interferes with recovery by worsening physical functioning, quality of life, and survival (Shewangizaw et al., 2023). It also impairs concentration, motivation and energy levels, further hindering reintegration (Argyriadis et al., 2020; Terrill, 2023).

Despite extensive research on the physical impacts of stroke, the psychological and existential dimensions remain underexplored, particularly among women in low-and middle-income countries (Dahlby and Boyd, 2024). Moreover, female stroke survivors are underrepresented in stroke research, limiting the development of gender-sensitive rehabilitation strategies that reflect their unique experiences (Dahlby and Boyd, 2024). In Africa, where socio-cultural expectations amplify vulnerabilities, women face peculiar existential challenges that require culturally appropriate, gender-responsive support systems (Santiago, 2024). Addressing these issues is essential to improving clinical outcomes and the overall wellbeing of Nigerian female stroke survivors.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study design

A concurrent mixed-methods research design; comprising a cross-sectional survey and a focus group discussion was adopted for this study. This approach provided broad and complementary insights into the existential concerns of the participants. The survey was used to obtain quantitative data while the focus group discussion elicited qualitative data on the personal experiences and existential concerns of participants.

2.2 Participants

A convenience sample of female stroke survivors recruited from the physiotherapy clinics of the four hospitals in South-west Nigeria (University College Hospital, Oyo state; Ring Road State Hospital, Oyo state; Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Osun state; and University of Osun Teaching Hospital, Osun state), participated in the survey. Six participants from this sample were purposively recruited for the focus group discussion. Eligible participants were: adults aged 18 years and above, with first incident stroke and a minimum post-stroke duration of 3 months, and who could comprehend and communicate freely in English and/or Yoruba language. Comprehension was determined by the participants' ability to follow a three-step command (indicating minimal or no cognitive impairment) (Olaleye et al., 2014). Female stroke survivors with co-existing neurological conditions such as Parkinson's disease and dementia; and those who had undergone mastectomy or any similar intervention that could lead to or had been associated with psychological distress were excluded.

2.3 Materials

The Existential Concerns Questionnaire was used to assess existential concerns. This is a 22-item self-report questionnaire, based on the theoretical model of the five factors of existential anxiety: fear of death, meaninglessness, identity, loneliness and guilt (Van Bruggen et al., 2017). Questions are rated as either true or false, with each true and false response scored as one and zero, respectively. The obtainable score ranges from 0 to 22. Higher scores indicate greater existential concerns and lower scores indicate lesser existential concerns. The questionnaire has good internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.82 and test-retest reliability of 0.78 (Ain and Gilani, 2021).

The Community Integration Questionnaire (Willer et al., 1994) was used to measure community integration. It is a 15-item self-report questionnaire with 3 domains: home integration (H), social integration (S), and integration into productive activities (P). Items 1–12 are scored on a scale of 0 to 2. Items 13, 14 and 15 are scored individually and then transformed into one variable called the jobschool variable which is scored from 0 to 5. The integration into productive activities domain score is obtained by summing the score of the 12th item and the jobschool variable score. The overall score ranges from 0 to 29. The community reintegration level is classified as: low (0–14), moderate (15–20) and high (21–29). The questionnaire has demonstrated good internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha of 0.86–0.90 and test-retest reliability of 0.80–0.90.

The Depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983; Geusgens et al., 2024) was used to assess psychological depression. The HADS-D comprises 7 items that are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3. The total score from all items is used to categorize the level or severity of depression as: non-case (0–7), mild (8–10), moderate (11–15) and severe (16–21). The questionnaire has a Cronbach's alpha of 0.80–0.90; and test-retest reliability of 0.80–0.90 (Stern, 2014).

The Revised Scoring Tool for the Classification of Socio-economic status in Nigeria (Ibadin and Akpede, 2021) was used to assess the socio-economic status of the participants. The tool has 3 items: level of education, occupation and income. The minimum annual income is set at ₦360,000 (i.e ₦30,000 per month, which was the minimum wage at the time of this study). Each item is graded on a six-point scale from 1 to 6, where 1 represents the highest level and 6 represents the lowest level of each socioeconomic variable. The total score from all items is divided by three (3) and used to classify the participants' socio-economic status into upper (1–2), middle (3–4), or lower (5–6) socio-economic class. A section for obtaining the socio-demographic and clinical information of participants: age, marital status, limb dominance, time since stroke onset, and side of stroke affectation, was added to the socio-economic status form.

2.4 Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital (UI/UCH) Health Research Ethics Committee (UI/UCH/EC/24/0746). Informed consent was obtained from all eligible participants after the purpose and rationale for the study had been fully explained to them.

2.4.1 Quantitative data collection

The existential concerns questionnaire, the depression subscale of hospital anxiety and depression scale, the community integration questionnaire and the revised scoring tool for the classification of socio-economic status in Nigeria were translated through a forward- backward approach. Copies of the questionnaires were hand-distributed and self-administered by participants in their preferred language. Filled-out questionnaires were also collected by hand. Data collection was from October 2024 to February 2025.

2.4.2 Qualitative exploration of existential concerns

The qualitative study was grounded ontologically in relativism (Österman, 2021) and epistemologically in interpretivism, based on the beliefs that there are multiple realities and that context is important in the understanding of participants' existential concerns (Kivunja and Kuyini, 2017). A Focus group discussion (FGD) was employed for the qualitative study. Six purposively sampled female stroke survivors from the survey sample participated in the FGD to explore their individual experiences and existential concerns. The lead author (OAO), who has experience in conducting qualitative research and has published multiple qualitative studies, served as moderator for the FGD, while the co-author was an observer. There was a notetaker who took minutes of the discussions in addition to the audio recordings. The authors were aware of how their positionality and preconceptions could influence the research process and data interpretation. Therefore, they practice reflexivity and approach the FGD with a commitment to minimize biases, thereby enhancing the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings.

A focus guide (Appendix 1), comprising semi-structured open-ended questions formulated from a review of existing literature was used to guide the discussion. Participants were informed of their rights to withdraw from the study at any stage and were assured of anonymity of the data collected. Informed consent for participation and audio recording was obtained from all participants. The discussion was recorded using the audio recorder of a smartphone. Data saturation was considered reached when no substantially new existential concerns emerged, and themes became recurring among participants. The FGD lasted approximately 60 min.

2.5 Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 23. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Chi-square test was used to investigate the association between community reintegration and each of the following: existential concerns and psychological depression. Associations between these variables and sociodemographic variables (age and marital status), were also tested with Chi-square test. Fisher's exact test was used to examine the associations between the variables and each of time since stroke onset and socio-economic status. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Qualitative data were analyzed using interpretative phenomenological analysis (Alase, 2017). This approach is well-suited for exploring the lived experiences of research participants, as it allows them to express themselves in their own way without distortion by the researchers, thereby minimizing researcher bias. The authors are female physiotherapists involved in stroke care, who, through cursory clinical observation, have noted that male stroke survivors often received more social support from their wives and children while female survivors tend to receive minimal social support from their husbands. Acknowledging the potential impact of this bias, authors were careful to ensure it did not influence the data analysis and interpretation process. The audio recording of the discussion was promptly and manually transcribed verbatim by one of the authors (ATO) within 48 h of the FGD, to accurately capture participants' perspectives. The transcripts were then verified by the lead author (OAO). Both authors read the transcripts carefully and multiple times, to familiarize themselves with the data and note emerging patterns. Data was then exported into a Microsoft Excel worksheet for analysis. All comments were entered individually into cells in a column. Each quote was reviewed and assigned to subthemes and themes in different columns using an inductive approach. Through a thorough process of review, refinement, grouping and regrouping, five themes were generated and presented sequentially to create a trajectory of the existential concerns of female stroke survivors in Nigeria. Representative quotes were used to illustrate each theme.

3 Results

The results of both the quantitative and qualitative studies were merged to provide a detailed exploration and a nuanced understanding of the existential concerns of the participants.

3.1 Survey results

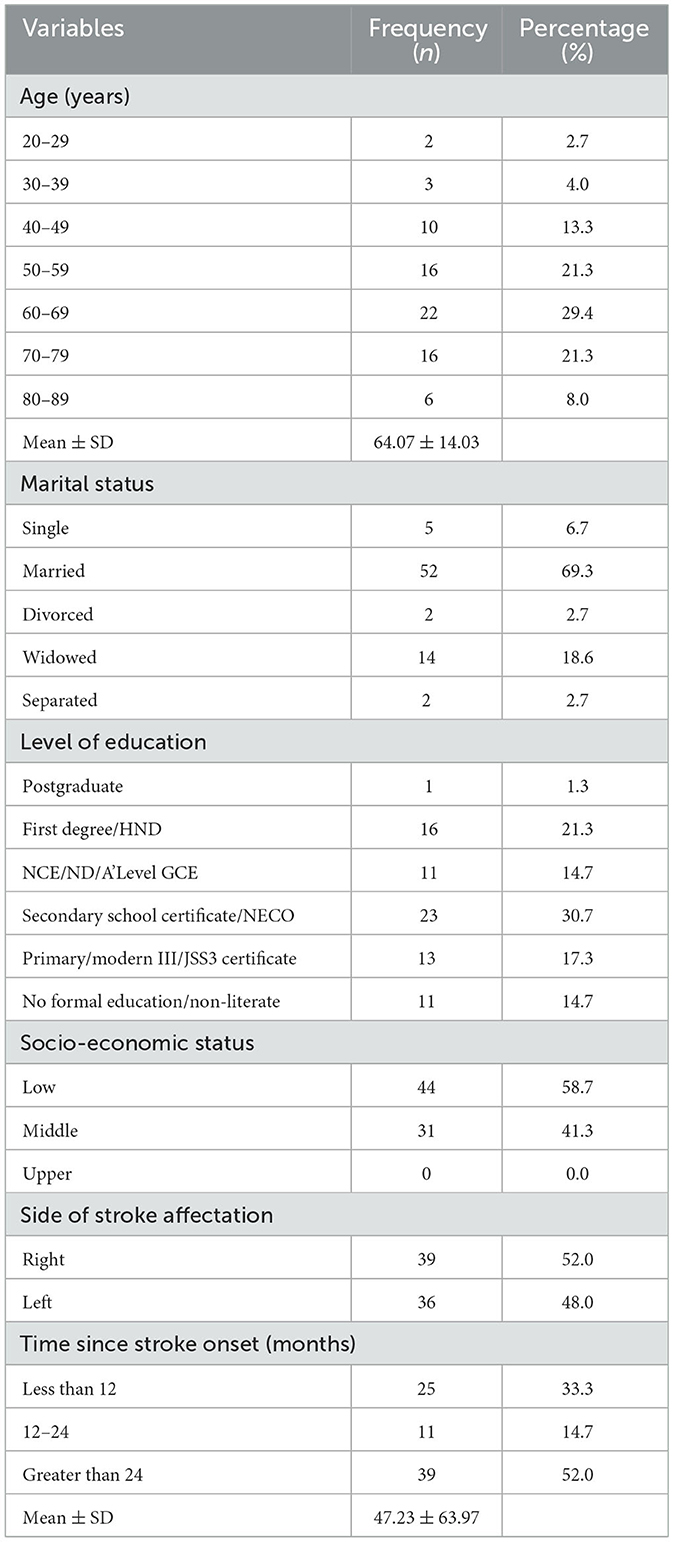

Seventy-five out of the 78 copies of the questionnaires administered to participants were properly completed and analyzed, giving a response rate of 96.2%. Participants were aged 64.07 ± 14.03 years, with a mean time since stroke onset of 47.23 ± 63.97months. More than half (58.7%) were in the lower socio-economic stratum. The mean community reintegration, existential concerns and psychological depression scores were 12.24 ± 2.95, 9.77 ± 5.52, and 13.84 ± 4.71, respectively. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are as summarized in Table 1.

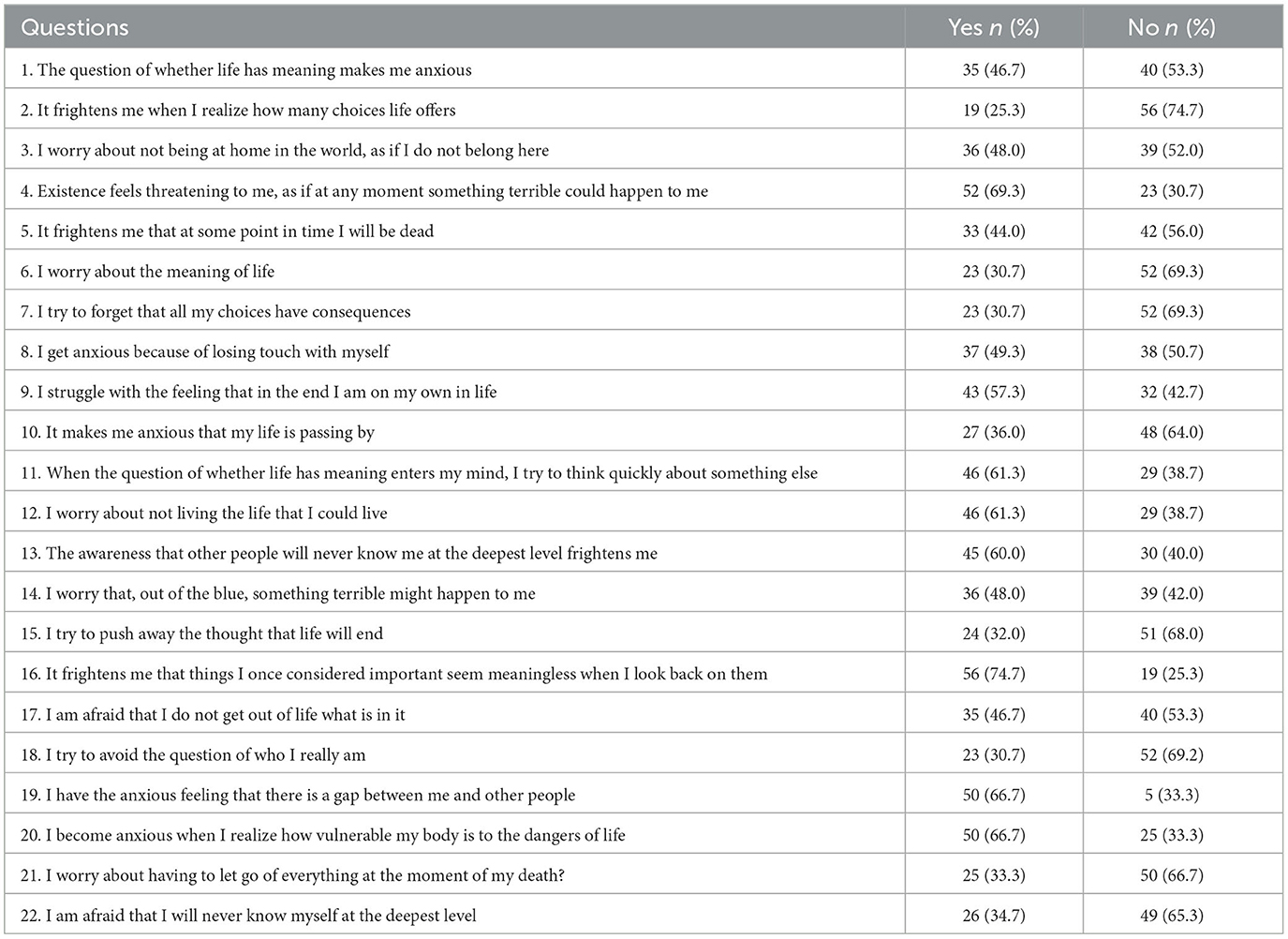

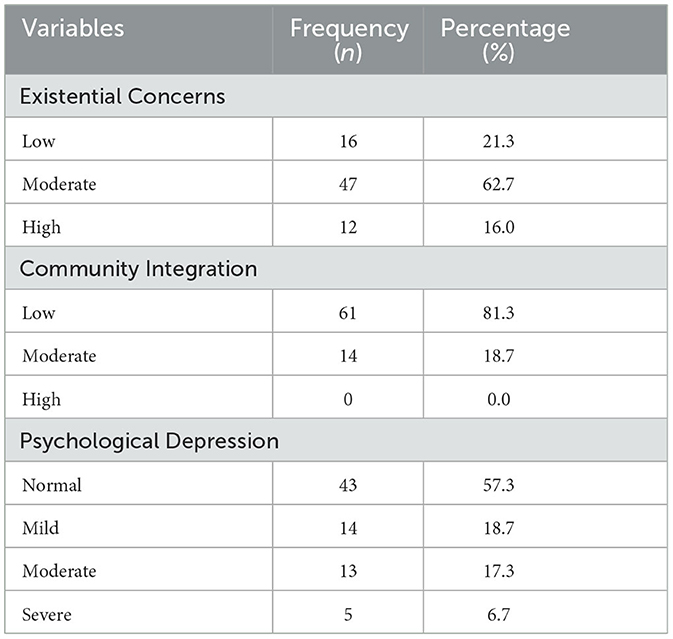

Community reintegration was generally poor. The majority (81.3%) of the participants had low reintegration scores. Fifty-nine (78.7%) participants seldomly leave their homes, and 72.0% rely on others for shopping (Table 2). Most of the participants (62.7%) reported moderate existential concerns (Table 2). More than two-thirds (69.3%) reported a persistent sense of threat, while 57.3% struggled with loneliness and 74.7% struggled with a loss of meaning (Table 3). More than half of the participants (57.3%) were classified as having no depression (Table 2), though 34 (45.3%) reported being cheerful only sometimes.

Table 2. Existential concerns, community integration and psychological depression among participants (n = 75).

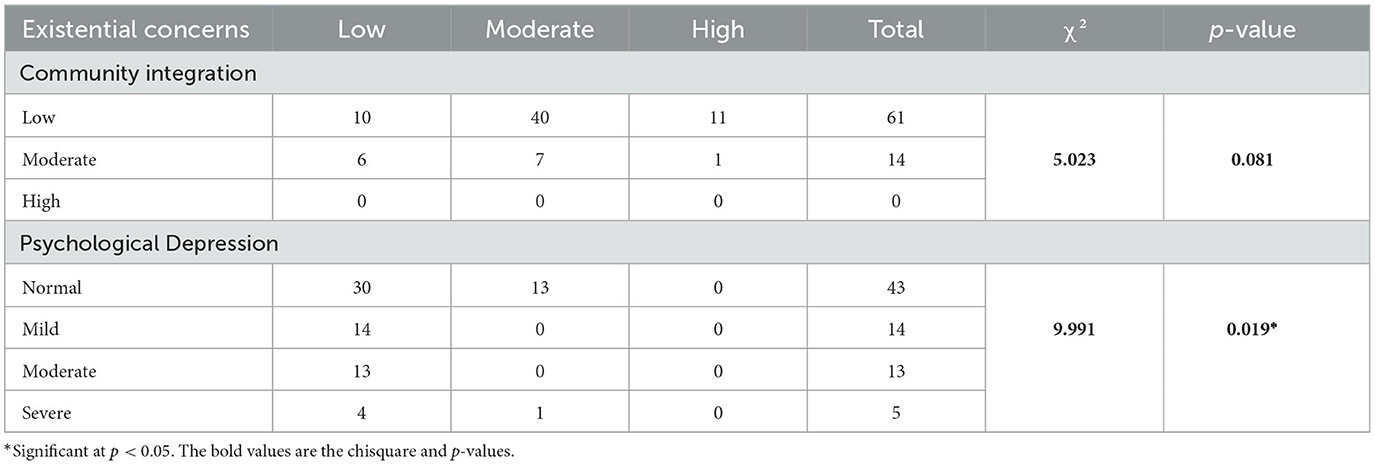

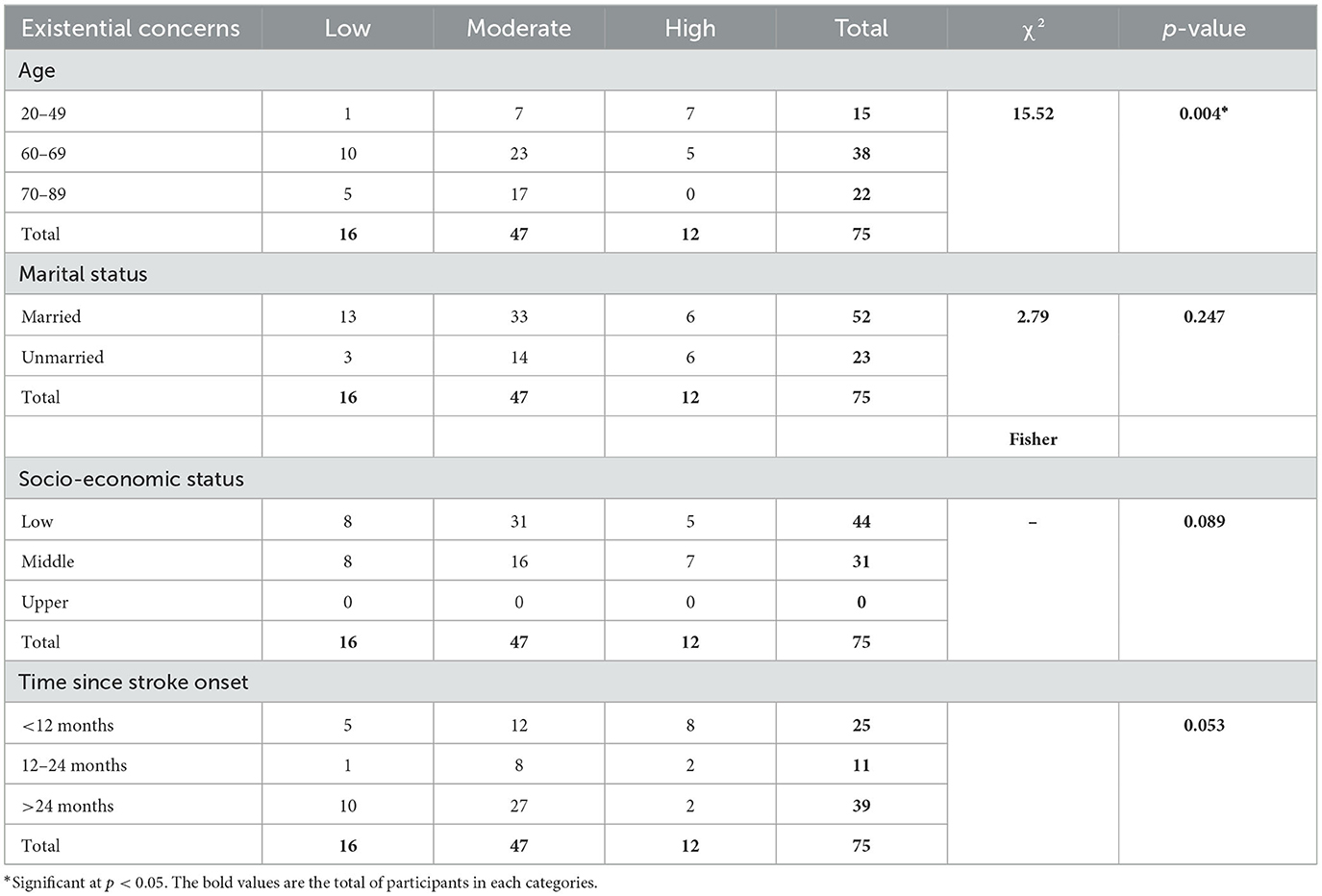

There was no significant association between community reintegration and existential concerns (p > 0.05) (Table 4). However, a majority of the women with moderate existential concerns reported low community reintegration. There was a significant association between community reintegration and depression (p = 0.019), and between existential concerns and psychological depression (p < 0.05). There was a significant association between existential concerns and age (p=0.004), whereas there was no significant association between existential concerns and marital status, socio-economic status or time since stroke onset (p > 0.05) (Table 5). There was a significant association between psychological depression and marital status (p = 0.02).

Table 4. Association between existential concerns and each of community integration and psychological depression (n = 75).

Table 5. Association between existential concerns, and selected socio-demographic and clinical variables.

3.2 Exploration of existential concerns among participants

To deepen the understanding of existential concerns among female stroke survivors, a focus group discussion (FGD) was conducted with six participants aged 54.00 ± 7.24 years. To ensure anonymity, participants were identified by numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) assigned by the researchers. Five emergent themes reflected the existential concerns of female stroke survivors.

3.2.1 Stroke as a devastating condition

The survey findings showed high existential threats among participants. This was echoed in the FGD, where participants described stroke as a devastating and life altering-experience. A participant noted that “stroke is a terrible experience and a devourer” (P4, 61years) that drains resources and disrupts life. Others emphasized the suddenness of onset, reinforcing feelings of unpredictability and loss of control:

“It was very sudden… I just fell down” (P5, 48 years)

3.2.2 Role disruption and loss of autonomy in the home

Consistent with the survey's findings of low community reintegration, the women lamented their inability to perform house chores or nurture their families. One explained:

“I have not been able to cook since it happened to me” (P3, 48years).

Some participants expressed frustrations at being unappreciated despite attempts to contribute:

“If I cook, my husband won't eat it because I didn't use both hands to make it. (P4, 61 years)

Another described sneaking to perform house chores “to avoid feeling redundant” (P6, 65 years).

This highlights how stroke undermined the women's valued identities as caregivers, deepening existential distress.

3.2.3 Isolation and stigmatization in society

Survey findings showed that most women seldom left their homes, and the FGD findings provided insights on why. Participants described withdrawing from social events due to perceived stigma and negative attention. One participant stated:

“I have stopped attending church services…I dislike the way people just stare at me” (P6, 65 years).

Others felt excluded by neighbors or relegated within community groups. Feelings of being avoided or disregarded led to self-imposed withdrawal, contributing to loneliness and underscoring stigma as a key barrier to reintegration:

“I go out to parties, but most times, I don't like how people treat me at such events…this discourages me from going out subsequently in order to avoid such experiences.” (P4, 61 years).

“Some people don't even associate with me again because of my condition.” (P1, 52 years).

3.2.4 Inadequate spousal support and changes in sexual intimacy

Emotional struggles experienced by participants were reflected in their narratives of strained spousal support and diminished sexual intimacy. While some couples mutually agreed to suspend sexual intimacy pending recovery, others reported dwindling care and support over time:

“We both agreed that we won't be sexually intimate until I'm back to good health…” (P5, 48 years).

“My husband no longer drives me to the hospital for physiotherapy, this makes me sad. It's my children who help now” (P1, 52 years).

This erosion of spousal support heightened fears of abandonment and contributed to psychological distress.

“I told my husband, if he leaves me at this stage…. You know sometimes, he gets angry and I plead with him to stay, he agrees” (P5, 48 years).

3.2.5 Work-related and financial concerns

Participants described workplace discrimination and financial burdens, aligning with the high prevalence of existential concerns. One woman recounted being pressured at work despite limitations, threatened with redundancy and outright loss of income:

“My boss would threaten to declare me redundant, which was very painful. I was worried I would be laid off unceremoniously because of my condition” (P4, 61 years).

The women expressed a desire for financial independence and early return to paid employment:

“It is my husband that helps me out financially… Is there a way for us to return to our work on time?” (P5, 48 years).

The participants also decried the lack of insurance coverage for long-term physiotherapy, exacerbating their financial strain.

4 Discussion

This mixed-methods study explored existential concerns, depression and community reintegration among female stroke survivors in Ibadan, Nigeria,. By merging quantitative and qualitative findings, we gained a nuanced understanding of how stroke disrupts identity, social roles and psychological wellbeing. There was a notable convergence in our findings.

4.1 Existential anxiety and depression

Consistent with previous reports (Oyewole et al., 2016; Badaru et al., 2015), participants described stroke as devastating, unpredictable and life-altering. Quantitative data showed that the majority felt their existence was under constant threat, while qualitative narratives revealed hidden despair and fear of mortality. Many respondents in the quantitative study avoided questions about the meaning of life, possibly as a defense mechanism against deep existential contemplation. It has been suggested that individuals facing major health crises suppress distressing thoughts to maintain emotional stability (Akosile et al., 2011). Despite more than half reporting no depression, the FGD uncovered episodes of crying and hopelessness, suggesting underreporting or social desirability bias (Bakare et al., 2024).

The strong association between existential concerns and depression reflects the interplay among uncertainty, loss of purpose and perceived lack of control (Agbola et al., 2020). Qualitative data highlighted the role of strained intimacy and inadequate spousal support in the prevalence of depression among married women. This reinforces evidence that psychosocial factors are as critical as physical disability in shaping post-stroke depression (Ibeneme et al., 2017).

4.2 Social expectations and role reversal

Loss of autonomy in household and caring roles was a central theme. Many women struggled with dependence, secrecy around chores and unappreciated efforts, reflecting how cultural expectations of women as caregivers exacerbate distress when they become care recipients (Vincent-Onabajo et al., 2018; Ogunlana et al., 2023). This has led some women to overextend themselves, resulting in injuries, and increased emotional distress. The perceived lack of appreciation and/or rejection by spouses deepened emotional pain, buttressing findings that unmet social expectations worsen psychological outcomes (Ihegihu et al., 2024). Tailored family education programs are essential to reduce role reversal trauma and validate the contributions of female stroke survivors within households.

4.3 Social isolation and stigma

Over half of the survey respondents reported fears about being alone, while FGD highlighted avoidance of public gathering and feeling of exclusion by neighbors and social networks. This aligns with earlier findings that social isolation is a barrier to reintegration (Obembe et al., 2010; Vincent-Onabajo et al., 2015). Stigma, rooted in misconception of stroke as contagious, compounded loneliness and reduced participation (Vincent-Onabajo et al., 2015). Involving survivors in peer-support groups and structured community activities could provide a sense of belonging, reduce stigma and buffer against depressive symptoms.

No significant association existed between existential concerns and community reintegration. This could be due to underreporting of existential distress or the stronger influence of stigma and physical disability on reintegration. However, the significant associations between existential concerns, age and depression highlight how psychological and social contexts shape reintegration trajectories.

4.4 Workplace reintegration and financial concerns

Many of the women in our study belonged to the lower socio-economic stratum, and narratives revealed financial strain and workplace discrimination. These findings resonate with reports by Soeker and Olaoye (2017) that stroke survivors in Nigeria struggle to resume work due to physical limitations and workplace discrimination. This underscores the need for policies that support workplace reintegration, which could mitigate barriers and support female stroke survivors' economic independence.

5 Study limitations

This study has some inherent limitations. Survey data are based on self-report questionnaires that might have introduced social desirability and recall biases. Also, the FGD sample was small and recruited from a single study site, limiting the generalizability of qualitative findings. Lastly, the cross-sectional design of the quantitative study precludes causal inference. Despite these limitations, the mixed-methods approach adopted for the study provided valuable complimentary perspectives.

6 Conclusion

The outcomes of this study highlight the unique existential concerns of female stroke survivors in Nigeria and their links with depression and limited community reintegration. These findings emphasize the need for gender-sensitive, community-based rehabilitation programs that integrate functional recovery with counseling and existential support. Family caregiver education on how to ease role-reversal trauma should be prioritized. Peer-support networks to reduce isolation and stigma should be encouraged for female stroke survivors. Policies to strengthen workplace reintegration, expand health insurance to cover long-term physiotherapy, and embed mental health services within stroke care are urgently needed for this population. Future longitudinal studies to capture changes in existential and psychological outcomes over time are needed. Also, comparative studies to explore how gender differences shape post-stroke adjustment should be conducted to guide the design of equitable and culturally sensitive interventions that could improve the quality of life of female stroke survivors in Nigeria and similar contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Ibadan/University College Hospital Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

OO: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Conceptualization. AO: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer OE declared a shared affiliation with the authors OO and AO at the time of review.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agbola, O. E., Akpa, O. M., Ojagbemi, A., and Afolabi, R. F. (2020). Multilevel modelling of the predictors of post-stroke depression in South-west Nigeria. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 23, 199–205.

Ain, S. N., and Gilani, S. N. (2021). Existential anxiety amid COVID-19 pandemic in Kashmir: a cross-sectional study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 10:184. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1102_20

Akosile, C., Nworah, C., Okoye, E., Adegoke, B., Umunnah, J., and Fabunmi, A. (2016). Community reintegration and related factors in a Nigerian stroke sample. Afr. Health Sci. 16, 772–780. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v16i3.18

Akosile, C. O., Okoye, E. C., Nwankwo, M. J., Akosile, C. O., and Mbada, C. E. (2011). Quality of life and its correlates in caregivers of stroke survivors from a Nigerian population. Qual. Life Res. 20, 1379–1384. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9876-9

Alase, A. (2017). The Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA): a guide to a good qualitative research approach. Int. J. Educ. Liter. Stud. 5, 9–19. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9

Argyriadis, A., Fylaktou, C., Bellou-Mylona, P., Gourni, M., Asimakopoulou, E., and Sapountzi-Krepia. (2020). Post stroke depression and its effects on functional rehabilitation of patients: socio-cultural disability communities. Health Res. J. 6:3. doi: 10.12681/healthresj.22512

Badaru, U., Ogwumike, O., and Adeniyi, A. (2015). Quality of life of Nigerian stroke survivors and its determinants. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 18, 1–5.

Bakare, A. T., Amin, H. H., Adebisi, A., Abubakar, A., Yakubu, A., Yahaya, H., et al. (2024). Assessment of depressive symptoms among post stroke patients attending a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Ibom Med. J. 17, 334–339. doi: 10.61386/imj.v7i2.446

Dahlby, J. S., and Boyd, L. A. (2024). Chronic underrepresentation of females and women in stroke research adversely impacts clinical care. Phys. Ther. 105:155. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzae155

Dymm, B., Goldstein, L. B., Unnithan, S., Al-Khalidi, H. R., Koltai, D., Bushnell, C., et al. (2024). Depression following small vessel stroke is common and more prevalent in women. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 33:107646. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2024.107646

Geusgens, C. A., van Tilburg, D. C., Fleischeuer, B., and Bruijel, J. (2024). The relation between insomnia and depression in the subacute phase after stroke. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2024.2370072

Hamzat, T. K., Ekechukwu, N. E., and Olaleye, O. A. (2014). Comparison of community reintegration and selected stroke specific characteristics in Nigerian male and female stroke survivors. Afr. J. Physiother. Rehabil. Sci. 6, 27–31. doi: 10.4314/ajprs.v6i1-2.4

Harini, S. A. T., and Suraweera, C. (2023). Prevalence and associated factors of post-stroke depression among stroke survivors during the early rehabilitation period: a cross-sectional study. Sri Lanka J. Psychiatry 14, 20–26. doi: 10.4038/sljpsyc.v14i1.8406

Ibadin, M. O., and Akpede, G. O. (2021). A revised scoring scheme for the classification of socioeconomic status in Nigeria. Nigerian J. Paediatr. 48, 26–33. doi: 10.4314/njp.v48i1.5

Ibeneme, S. C., Nwosu, A. O., Ibeneme, G. C., Bakare, M. O., Fortwengel, G., and Limaye, D. (2017). Distribution of symptoms of post-stroke depression in relation to some characteristics of the vulnerable patients in socio-cultural context. Afr. Health Sci. 17, 70–78. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v17i1.10

Ihegihu, E., Onwukwe, J. K., Afolabi, T. O., Ihegihu, C., and Wale-Aina, D. A. (2024). Exploring the correlation between sexual function, mental health, and quality of life among stroke survivors in South-East Nigeria. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 11, 333–341. doi: 10.51244/IJRSI.2024.1108028

Kingau, N., Rhoda, A., Louw, Q., and Nizeyimana, E. (2024). The impact of stroke support groups on stroke patients and their caregivers. Rehabil. Adv. Dev. Health Syst. 1:12. doi: 10.4102/radhs.v1i1.9

Kivunja, C., and Kuyini, A. B. (2017). Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. Int. J. High. Educ. 6:26–41. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v6n5p26

Kretschmer, M., and Storm, L. (2018). The relationships of the five existential concerns with depression and existential thinking. Int. J. Exist. Psychol. Psychother. 7:1–20.

Liljehult, M. M., von Euler-Chelpin, M. C., Christensen, T., Buus, L., Stokholm, J., and Rosthøj, S. (2021). Sex differences in independence in activities of daily living early in stroke rehabilitation. Brain Behav. 11:2223. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2223

Nettles, T. C. G. (2024). Examining factors that contribute to poststroke depression within the family caregiver and care recipient dyadic experience. Perspect. Am. Speech-Lang.-Hear. Assoc. Special Interest Groups 9, 1853–1867. doi: 10.1044/2024_PERSP-23-00294

Obembe, A. O., Johnson, O. E., and Fasuyi, T. F. (2010). Community reintegration among stroke survivors in Osun, Southwestern Nigeria. Afr. J. Neurol. Sci. 29, 9–16.

Ogunlana, M. O., Oyewole, O. O., Fafolahan, A., and Govender, P. (2023). Exploring community reintegration among Nigerian stroke survivors. South Afr. J. Physiother. 79:1857. doi: 10.4102/sajp.v79i1.1857

Olaleye, O. A., Hamzat, T. K., and Owolabi, M. O. (2014): Stroke rehabilitation: should physiotherapy intervention be provided at a primary health care centre or the patients' place of domicile. Disabil. Rehabil. 36, 49–54 doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.777804

Österman, T. (2021). Cultural relativism and understanding difference. Lang. Commun. 80, 124–135. doi: 10.1016/j.langcom.2021.06.004

Oyewole, O., Ogunlana, M., Oritogun, K., and Gbiri, C. (2016). Post-stroke disability and its predictors among Nigerian stroke survivors. Disabil. Health J. 9, 616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.05.011

Pathan, N. M., Saxena, R., Kumar, C., Kamlakar, S., and Yelikar, A. (2024). Stroke rehabilitation in India: addressing gender inequities. J. Lifestyle Med. 14, 94–97. doi: 10.15280/jlm.2024.14.2.94

Petrea, R. E., Beiser, A. S., Seshadri, S., Kelly-Hayes, M., Kase, C. S., and Wolf, P. A. (2009). Gender differences in stroke incidence and poststroke disability in the framingham heart study. Stroke 40, 1032–1037. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.542894

Rizzo, F., Taborda, B., Muchada, M., Colangelo, G., Purroy, F., Roig, X. U., et al. (2024). Abstract TMP43: patient reported outcomes and mood disorders differences according to sex and gender after stroke. Stroke 55. doi: 10.1161/str.55.suppl_1.TMP43

Santiago, J. (2024). Existential concerns and supports. An investigation into vulnerability. Papeles del CEIC Int. J. Collect. Ident. Res. 298: 1–17. doi: 10.1387/pceic.25840

Shewangizaw, S., Fekadu, W., Gebregzihabhier, Y., Mihretu, A., Sackley, C., and Alem, A. (2023). Impact of depression on stroke outcomes among stroke survivors: systematic review and meta- analysis. PLoS ONE 18:0294668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294668

Soeker, M. S., and Olaoye, O. A. (2017). Exploring the experiences of rehabilitated stroke survivors and stakeholders with regard to returning to work in South-West Nigeria. Work 57, 595–609. doi: 10.3233/WOR-172590

Stern, A. F. (2014). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occup. Med. 64, 393–394. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu024

Terrill, A. L. (2023). Mental health issues poststroke: underrecognized and undertreated. Stroke 54, 1528–1530. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.042585

Thompson, H. S., and Ryan, A. (2019). The lived experience of female stroke survivors: a phenomenological study. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being 14:1632109.

Vail, K. E., Sullivan, D., Landau, M. J., and Greenberg, J. (2020). Editorial foreword: applying existential social psychology to mental health. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 39, 229–237. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2020.39.4.229

Van Bruggen, V., Ten Klooster, P., Westerhof, G., Vos, J., and de Kleine, E. (2017) The Existential Concerns Questionnaire (ECQ)-Development Initial Validation of a New Existential Anxiety Scale in a Nonclinical Clinical Sample. J Clin Psychol. 73:1692–1703. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22474.

Vincent-Onabajo, G., Gayus, P. P., Masta, M. A., Ali, M. U., Gujba, F. K., Modu, A., et al. (2018). Caregiving appraisal by family caregivers of stroke survivors in Nigeria. J. Car. Sci. 7, 183–188. doi: 10.15171/jcs.2018.028

Vincent-Onabajo, G., Muhammad, M., Ali, M., and Masta, M. (2015). Influence of sociodemographic and stroke-related factors on availability of social support among Nigerian stroke survivors. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 5, 353–357. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.165258

Walsh, M. E., Galvin, R., Loughnane, C., Macey, C., and Horgan, N. F. (2015). Factors associated with community reintegration in the first year after stroke: a qualitative meta- synthesis. Disabil. Rehabil. 37, 1599–1608. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.974834

Wan, X., Chan, D. N. S., Chau, J. P. C., Zhang, Y., Liao, Y., Zhu, P., et al. (2024). Effects of a nurse-led peer support intervention on psychosocial outcomes of stroke survivors: a randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 160:104892. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104892

Willer, B., Ottenbacher, K. J., and Coad, M. L. (1994). The community integration questionnaire: a comparative examination. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 73:1. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199404000-00006

Witt, P., Lindner, C., Franzsen, D., and Maseko, L. (2024). Environmental facilitators and barriers to community reintegration experienced by stroke survivors in an under-resourced urban metropolitan sub-district. South Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 54:5. doi: 10.17159/2310-3833/2024/vol54no2a5

Xiao, W., Liu, Y., Huang, J., Huang, L. A., Bian, Y., and You, G. (2024). Analysis of factors associated with depressive symptoms in stroke patients based on a national cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 14:9268. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-59837-3

Xu, M., Amarilla, V. A., Cantalapiedra, C. C., Rudd, A., Wolfe, C., and O'Connell, M. D. L. (2022). Stroke outcomes in women: a population-based cohort study Stroke 53, 3072–3081. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.037829

Zhou, Y., Gisinger, T., Lindner, S. D., Raparelli, V., Norris, C. M., Kautzky-Willer, A., et al. (2024). Sex, gender, and stroke recovery: functional limitations and inpatient care needs in Canadian and European survivors. Int. J. Stroke 20, 215–225. doi: 10.1177/17474930241288033

Zigmond, A. S., and Snaith, R. P. (1983). A self-rating scale for anxiety and depression: validation in a clinical setting. Psychol. Med. 13, 361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Appendix—Focus Guide

1. Can you kindly share with us what stroke meant to you based on your personal experience of stroke?

2. How has having a stroke affected your roles at homes, at work and your immediate community?

3. In what ways do you feel stroke has changed your identity or self-worth as women?

4. How do you think having a stroke has changed how others see you or what they expect of you? Probe: How do you respond to these changes?

5. What has been your experience in terms of support from your husband, children and other relatives since your stroke? Probe: How has your husband and family encouraged you to return to your previous activities?

6. How has stroke affected your sexual life or intimacy with your husband?

7. Is there anything you will like to tell or ask us that we have not talked about on how stroke has affected you as women?

Keywords: female, stroke survivors, community reintegration, existential concerns, emotional and mental wellbeing, depression

Citation: Olaleye OA and Olajide AT (2025) Existential concerns, community integration and psychological depression among female stroke survivors in Nigeria. Front. Stroke 4:1635705. doi: 10.3389/fstro.2025.1635705

Received: 13 June 2025; Accepted: 22 September 2025;

Published: 14 October 2025.

Edited by:

Patricia Munseri, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, TanzaniaReviewed by:

Michael Ogunlana, Bowen University, NigeriaOlufisayo Elugbadebo, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Copyright © 2025 Olaleye and Olajide. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olubukola A. Olaleye, b2x1YnVrb2xhb2xhbGV5ZUB5YWhvby5jb20=; b2FvbGFsZXllQGNvbS51aS5lZHUubmc=

Olubukola A. Olaleye

Olubukola A. Olaleye Ayomide T. Olajide

Ayomide T. Olajide