- Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, College of Social Sciences and Humanities, Woldia University, Woldia, Ethiopia

This study investigates the challenges and inequities in infrastructure provision and service accessibility in informal peri-urban settlements, focusing on Woldia, Ethiopia. Using mixed methods, including survey questionnaires, interviews, focus groups, and field observations, the research explores the interplay between formal policies and informal practices in delivering basic infrastructure such as water, roads, and electricity. Findings reveal systemic exclusion of informal settlements from formal infrastructure planning and investment, perpetuating socio-economic inequalities. Local authorities prioritize planned urban areas, while informal residents rely on alternative, often costlier, and lower-quality services, such as informal water vendors and shared electricity connections. Informal settlers pay exorbitant rates for water—up to 1,645% higher than formal residents—and face unreliable electricity, leading to reliance on firewood and kerosene. Informal actors, including local leaders, vendors, and corrupt officials, play crucial roles in filling service gaps but exacerbate financial burdens. The study underscores the structural neglect of informal settlements, evidenced by stark disparities in investment and infrastructure access between central and peripheral areas. Recommendations include improving municipal accountability, optimizing resource distribution systems, and recognizing the role of non-state actors in service delivery. Addressing these challenges is critical for fostering equitable urban development and improving living conditions in marginalized peri-urban communities. The findings have broad implications for policy reforms aimed at inclusive infrastructure planning and socio-economic equality.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background of the study

There exist divergent perspectives regarding the development of informal settlements. While some, like Turner (1977), perceive them as housing options for the impoverished, others categorize informal settlements as urban blights, likening them to cancers or festering sores that pose threats to public safety and health (Amoako and Boamah, 2016; Hardoy and Satterthwaitet, 1986; Potter and Lloyd-Evans, 2014). Due to these negative perceptions, informal settlers are often marginalized and denied access to basic infrastructure services, despite living in an era marked by urbanization and digital advancement (Winayanti and Lang, 2004). They are considered “wild residents” and face eviction threats, either through forceful removal by authorities or policy changes (Turner, 1977; United Nations, 2018). Consequently, informal settlements become sites of injustice where profit motives overshadow the wellbeing, dignity, and rights of residents and the environment (Harris, 2017; Perlman, 2010).

As a result of this marginalization, informal settlements commonly suffer from inadequate access to essential services such as water supply, sanitation, waste management, roads, drainage systems, electricity, and public transportation. Residents find themselves living “off the grid,” lacking safe and reliable piped water supply, sanitation facilities, and proper waste disposal mechanisms (Tutu and Stoler, 2016). They are excluded from infrastructure extension plans and municipal services, perpetuating their status as marginalized urban dwellers (Fekade, 2000; Lombard, 2014; Pierce, 2017). This situation significantly impacts residents' health, overall quality of life, and social wellbeing. Moreover, informal settlements are devoid of emergency services during crises such as floods or fires, as well as public educational institutions and healthcare facilities (Leitmann and Baharoglu, 1999; Satterthwaite, 2009; UN-Habitat, 2016; Ansah and Chigbu, 2020). Consequently, the provision and accessibility of basic urban infrastructure services in informal settlements fail to meet the demands of the general populace in developing countries.

In this context, the construction of informal housing is often deemed illegal, encompassing not only the occupation of the land or the erection of shelters but also the utilization of physical infrastructure and services. Consequently, numerous activities within these settlements, such as water sourcing, electricity access, healthcare consultations, and informal commerce, are considered unlawful (Sinharoy et al., 2019). This prevalence of illegal activities within informal settlements poses significant barriers to accessing and securing basic urban infrastructure services. Despite the critical need for such services, various obstacles hinder their provision, including legal, spatial, social, institutional, and political barriers (Sinharoy et al., 2019; Allen, 2010).

Pierce (2017) and Sinharoy et al. (2019) highlighted the significant obstacle of economic barriers to accessing and securing basic urban infrastructure within informal settlements. The inadequacy of economic resources is believed to underlie these challenges, as infrastructure development demands substantial investments, which are often beyond the financial means of households in informal settlements. Additionally, the informal status of these areas hampers the establishment of legal taxation systems, resulting in limited funding for infrastructure projects. Consequently, due to issues like poor financial management, low funding priorities, lack of autonomy, and limited engagement with civil society, local governments have not been able to invest in urban infrastructure within informal settlements (Allen, 2010; Nguyen et al., 2017; Jimenez-Redal et al., 2014).

The spatial dimension presents a significant barrier to accessing and securing infrastructure in informal settlements. According to Pierce (2017), Sinharoy et al. (2019), and UN-Habitat (2013), these settlements are often situated in undesirable or geographically challenging areas of urban landscapes, making it difficult to provide basic infrastructure services. The inherent geographic characteristics of informal settlements, such as peripheral location, unstable terrain, or susceptibility to flooding, contribute to this challenge. Additionally, the high housing density and irregular urban layout typical of informal settlements further complicate efforts to ensure access to and security of basic infrastructure.

Social barriers represent a significant impediment to accessing and securing infrastructure in informal settlements. Government agencies, as noted by Pierce (2017), often fail to provide basic services to specific ethnic, racial, religious, or caste groups residing in these areas. This lack of inclusivity stems from various factors, including limited awareness among informal settlement residents about urban administrative agencies, which can be attributed to patterns of rural-urban migration. Furthermore, residents frequently lack the necessary time, resources, and knowledge to advocate for themselves and hold officials accountable for policies or engage in community development efforts (Pierce, 2017; Sinharoy et al., 2019). Consequently, individuals living in informal settlements, often marginalized due to poverty and discrimination based on caste, ethnicity, race, or religion, struggle to access and secure infrastructure services.

Another fundamental obstacle to accessing and securing infrastructure relates to legal and institutional issues. Research conducted by Pierce (2017) in four slum settlements located in Hyderabad, India, indicates that the level of legal and institutional recognition significantly impacts tenure security, which consequently affects access to basic services in informal areas. Governments sometimes refrain from extending services to informal settlements due to concerns that doing so would imply formal acknowledgment of these settlements. Depending on local laws, certain buildings may be exempted from receiving formal service provisions if they fail to meet specific legal standards (Gaisie et al., 2018). Furthermore, the presence of confusing or conflicting laws, particularly in the absence of a comprehensive policy vision, can pose barriers to the implementation of inclusive infrastructure policies, even when such policies exist (Sinharoy et al., 2019). In some instances, infrastructure projects may be unable to proceed due to lacking necessary conditions, such as formal addresses for plots, residents lacking legal documentation for registration, or households lacking documents establishing boundaries and ownership of plots. Additionally, laws often prohibit the public provision of infrastructure in informal settlements (UN-Habitat, 2013).

The other impediment to providing infrastructure to informal settlements pertains to political barriers. Residents of informal settlements often trade their political influence for sporadic assistance or unfulfilled promises. Alternatively, the service concerns of slum dwellers may be conveyed to local government authorities by ineffective or corrupt representatives. In a study by Sinharoy et al. (2019) examining the factors influencing water and sanitation policies for urban informal settlements in low- and middle-income countries, several political barriers to implementing infrastructure policies for informal settlements are highlighted, including corruption and patronage. Thus, Pierce (2017) emphasizes the significance of political hindrances in delivering services to informal settlements.

1.2 Supply chains and costs of infrastructure in the informal built environment

Informal settlements typically emerge in two main scenarios, each highlighting significant challenges in urban governance and housing provision. The first scenario involves unauthorized construction in formal areas, where individuals build in designated zones without obtaining the necessary permits or approvals from relevant authorities, often circumventing formal regulations. The second scenario occurs in non-designated areas, where individuals occupy and construct buildings on land that is not formally allocated for development and where they lack legal ownership or rights. Both cases underscore critical deficiencies in urban planning, weak enforcement of regulatory frameworks, and the limited availability of affordable housing options, which collectively contribute to the proliferation of informal settlements.

Informal settlements, thus, face deficiencies in basic infrastructure, prompting the emergence of non-governmental organizations, community-based groups, and small-scale private service providers to bridge gaps left by formal systems (Narayanan et al., 2017; Shaheen, 2022). Key stakeholders in service delivery include the government, the private sector, and voluntary organizations (Pierce, 2017; Sinharoy et al., 2019). However, legal restrictions and overlooked illicit practices have spurred informal service providers, shifting infrastructure provision to non-state actors such as water vendors and local civil society groups (Yirgalem, 2008).

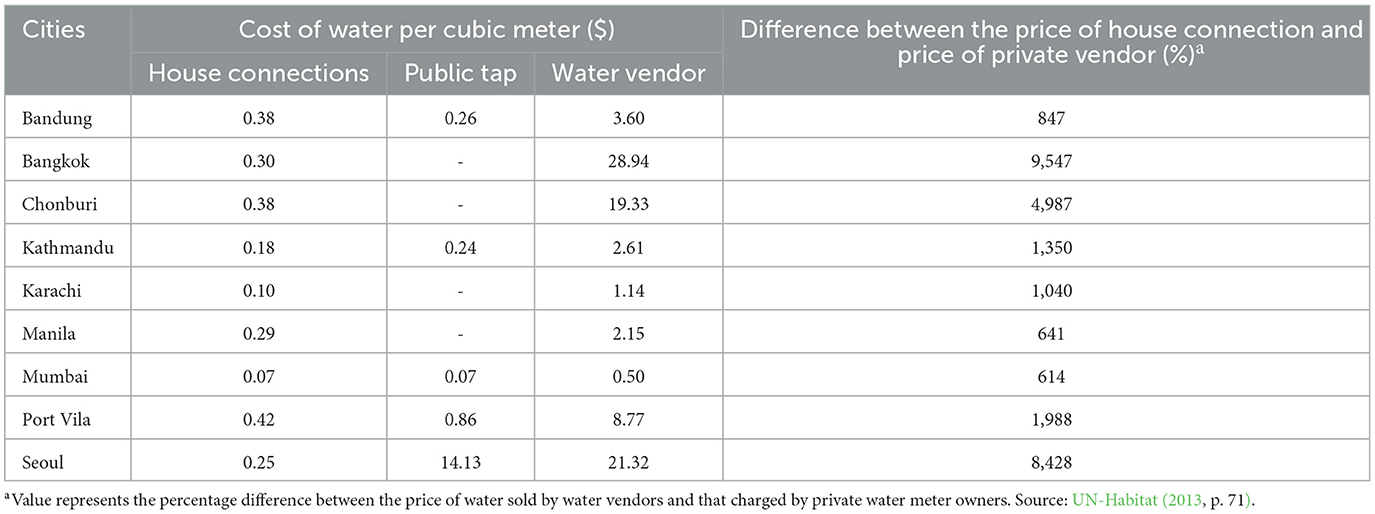

Traditional regulations often fail to improve infrastructure access in informal settlements, as seen in Turkey's gecekondus, where informal actors bypass formal rules to address local needs (Leitmann and Baharoglu, 1999). These actors frequently collaborate with larger entities to supply services to underserved communities (UN-Habitat, 2009). Despite high costs, utilities extending infrastructure to informal areas often face unauthorized connections, further increasing expenses (Leitmann and Baharoglu, 1999). Informal residents without legal tenure are denied services, unlike formal counterparts (Varley, 2002), forcing reliance on costly private providers. For example, UN-Habitat (2013) reports water costs from private vendors are up to 9,547% higher than household connections in some Asian cities. Consequently, many informal settlers lack affordable access to a water, electricity, sanitation, and transportation, underscoring the critical need for equitable service solutions (refer to Table 1).

Low-income residents in informal settlements often pay significantly higher costs for basic services such as water and sanitation. Households purchasing water from private vendors face steep charges and spend excessive time fetching water—averaging 92 min daily in some East African cities (UN-Habitat, 2013). Water costs can consume up to 45% of household income when relying on vendors, compared to 5%−10% for piped connections (Gimelli et al., 2018). Similarly, public toilet fees in Kumasi, Ghana, use 10%−15% of a primary earner's wages, while financial constraints drive open defecation in Indian cities (UN-Habitat, 2013). Inadequate sanitation in Kenya leads to makeshift practices like “flying toilets” (Fox and Beall, 2009), with community-managed latrines charging access fees (Mutisya and Yarime, 2011).

Electricity access is also limited, with high fees and illegal connections common in informal areas like Kibera, Kenya, and Brazilian favelas, where reliance on wood and charcoal persists (Mutisya and Yarime, 2011; Mimmi and Ecer, 2010). Informal residents often allocate higher income shares to energy than wealthier urban populations. Despite land legality in some unauthorized subdivisions, utilities rarely invest in informal settlements.

Using Woldia as a case study, this research examines infrastructure deficiencies, barriers to access, socio-economic impacts, and strategies employed by residents to address challenges in informal peri-urban settlements, focusing on roads, water supply, and electricity. The findings highlight systemic inequalities and the urgent need for inclusive solutions.

2 Methods and study sites selection

2.1 Study sites selection

Woldia, which is the capital of North Wollo Zone, is categorized as Regio-Politan town administration as per ANRS Proclamation No. 245/201 (ANRS, 2017). The case study areas are found in the peri-urban area of Woldia. Astronomically, Woldia lies between 11° 48′ 56″ N and 11° 50′ 39″N latitudes and 39°34′30 ″E-39°36′56″E longitudes. Its name, meaning “a meeting central place,” reflects that it was serving as a break of bulk point not only to the proximate areas but also to far great distances (Guta, 1966; Baye, 2009). As the data from the cadastral office and the land management core process owner of Woldia municipality reveal, in 2019 Woldia town had an area of 2,097 ha. In the same year, the population of Woldia was about 83,806 (CSA, 2016) giving it a population density of 40 people per ha.

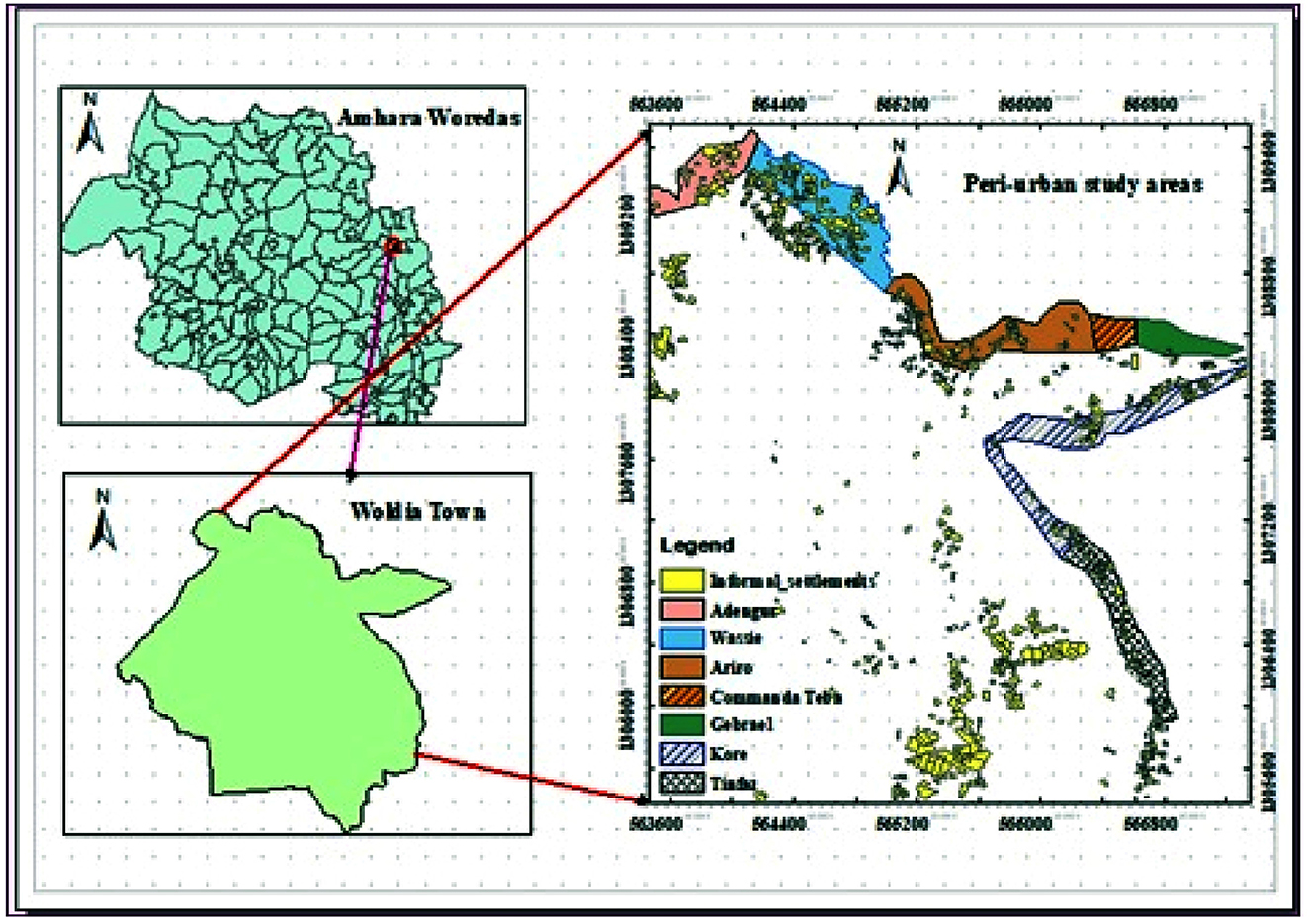

Seven neighborhood peri-urban areas located in the northern, northeastern, and eastern margins of Woldia form the case study areas (see Figure 1). They are purposely selected as they constitute the town's largest concentration of informal settlements (Baye et al., 2020a). Yet, these areas are expanding rapidly without being adequately accessed with basic infrastructure development. In addition to the question of legality, the provision of vital infrastructures in these peri-urban areas is abandoned by public agencies due to overlapping jurisdictions along with poor clarity and coordination of management responsibilities. These case study areas, thus, include Adengur, Wassie, Ariro, Commanda Teba, Foot of Gebrael, Kore, and Tinfaz.

Figure 1. Peri-urban study areas and spatial distribution of informal settlements. Source: Constructed by the author.

2.2 Methods

To accomplish the research objectives, this research has used a mixed research approach. The decision to adopt a mixed research approach is driven by the complex nature of the issue at hand. Given that the issue at hand is multifaceted and multidimensional, relying solely on either quantitative or qualitative methods is unlikely to yield comprehensive findings. Therefore, a mixed research method is deemed suitable for exploring the intricate and multiple dimensions of urban infrastructure challenges, including physical, economic, social, and political factors. This approach posits that integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches offers a more comprehensive understanding of research problems compared to using either approach in isolation (Creswell and Plano, 2011). Furthermore, employing a mixed research approach within a single study helps mitigate the limitations associated with relying solely on one approach (Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009).

To understand the current state of urban infrastructure in informal settlements, the study employs a descriptive research design. There are several reasons why a case study design is selected for undertaking the exploration of urban infrastructure in informal peri-urban Woldia. First, a case study design allows for a detailed and comprehensive examination of the specific context and dynamics of urban infrastructure challenges in Woldia. It provides an opportunity to delve deeply into the unique characteristics, complexities, and nuances of the peri-urban environment, enabling a more profound understanding of the barriers, implications, and informal strategies at play. Secondly, Woldia and its peri-urban areas have distinct socio-economic, cultural, and geographic features that influence urban infrastructure challenges. Thirdly, by focusing on a specific case, the researcher can take a holistic perspective that considers multiple dimensions of urban infrastructure challenges, including physical, economic, social, and political factors. Fourthly, by understanding the specific barriers and informal strategies employed by residents and local authorities, policymakers and practitioners can design interventions that are responsive to the unique needs and dynamics of the area. Fifth, the case study design allows for the collection of rich and detailed data through a variety of methods, including interviews, surveys, observations, and document analysis.

The researcher collected both primary and secondary data from relevant sources. To this end, primary data were collected from structured survey questionnaires, interviews, FGDs, and observations. To gather quantitative data on infrastructure conditions, access, and satisfaction levels, structured survey questionnaires were conducted with 244 peri-urban informal residents. The selection of sample household respondents was mainly made among peri-urban dwellers where the land transaction takes place largely outside the land law and infrastructure availability is minimal. For questionnaire administration to informal settlers, there is no official data about the actual number of informal settlers. Consequently, the following sample size determination formula has been applied (Cochran, 1963; Kothari, 2004).

Where

n = the sample size,

z2 = the value of the normal curve that divides an area at the tails (1-a equals the desired confidence level, e.g., 95%),

e2= the anticipated level of precision or the acceptable error,

p = the proportion of the population with the characteristics of the case, informality in this case (0.80),

q = the proportion of the population without the characteristics of informality (0.20).

The onsite questionnaire survey was conducted in the targeted peri-urban households in January and February 2019 using a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was pilot-tested on four informal settlers before being administered to the actual fieldwork. Based on the validation, hence, the instrument has been further refined. Two hundred forty-six questionnaires were distributed to sample households but the final analysis of the study was conducted based on the 244 respondents (90 male and 154 female, aged 18 years and above) which completed and satisfied all the information needed for this study.

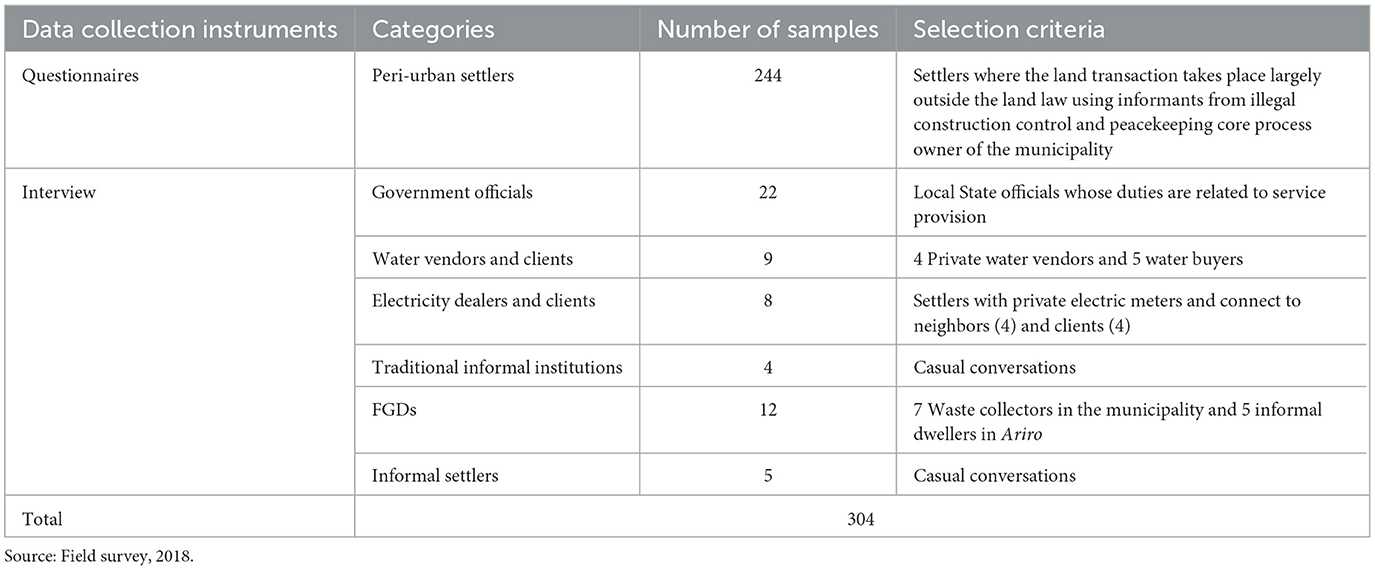

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 22 key local State officials whose duties are related to service provision. Semi-structured interviews were also conducted with four private water vendors and five private clients (buyers). Four electricity dealers and four clients were also interviewed to substantiate the data collected using other methods. Individuals from traditional informal institutions were also interviewed in a casual conversation. While water vendors were selected using the snowball technique, electricity dealers were selected where houses connected the electric wire to multiple neighbors identified during a field visit. Besides, information from traditional informal institutions was collected using a causal conversation with individuals during the time of Iddir and Equb meetings. This study also draws primary data from two FGD sessions: one held with seven members of hired municipal waste collectors (Cleaners), and a second with informal settlers (5 in number) at Ariro. The questions prepared for interviews were semi-structured and flexible so that details and unanticipated questions were pursued during the interview. The process of gathering data from all 304 participants for this research took a total of 35 days. The administration of questionnaires was relatively efficient, as data collectors were responsible for distributing and collecting them within the designated timeframe. However, conducting interviews required a longer duration due to challenges related to respondent availability. Scheduling interviews was influenced by factors such as the participants' daily commitments, and work schedules.

All in all, a total of 304 participants in various categories have been involved in conducting this research as shown in Table 2. In addition to these primary sources of data, each study area has been visited and the situation of infrastructure facilities was observed and photographed. The transect walks were held with a formal talk with a person in charge of the illegal construction control and peacekeeping core process owner of the municipality.

The researcher collected secondary data from published and unpublished materials. Public policy documents, development programs documents, and legal documents were reviewed to understand their implication for the implementation from the perspective of urban infrastructure. In addition, books, and journals, were reviewed.

Data were analyzed through the use of a mixed method of data analysis (qualitative and quantitative). The qualitative data from informal settlements such as Adengur, Wassie, Ariro, Commanda Teba, Foot of Gebrael, Kore, and Tinfaz was analyzed using systematic interpretative techniques to identify key patterns and themes. The process began with data organization and transcription, ensuring that interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs), and field observations were accurately recorded. Open coding was then applied to categorize key phrases, followed by axial coding to group related concepts. Thematic analysis (Neuendorf, 2017) was used to identify core themes, including barriers to infrastructure access, community coping mechanisms, roles of local actors, and tensions with authorities. To enhance data validity, triangulation was applied by cross-referencing interview responses with FGDs and interviews. Interpretative techniques such as narrative analysis helped explore how informal settlers navigate infrastructure inequities, while comparative analysis highlighted variations across settlements. Finally, the findings were synthesized into thematic discussions, incorporating direct participant quotes for authenticity and using comparative assessment tables to illustrate key differences. The qualitative analysis includes the use of figures, photos, and descriptive tools used in interview interpretation, field survey observation, and FGDs.

Similarly, the quantitative analysis includes the use of simple descriptive statistics such as mean and percentage and displaced using tables, and. The data were integrated to reflect the situation of infrastructure services in the informal settlements at the peri-urban of Woldia. Other characteristics of the study, such as the various socio-economic, demographic, and housing conditions of the respondents are included in the dataset (Baye et al., 2020b).

The affordability and accessibility of basic public urban infrastructure services for peri-urban informal residents were computed using the following formulas.

2.2.1 Affordability assessment

The Water Poverty Index measures the percentage of household income spent on water services. It provides insights into the affordability of water supply for peri-urban residents relative to their income levels.

The Energy Poverty Index measures the percentage of household income spent on energy services, such as electricity and cooking fuels. It helps assess the affordability of energy access for peri-urban residents.

2.2.2 Accessibility gradient analysis

This method involves creating accessibility gradients based on travel time or distance from peri-urban settlements to infrastructure facilities. It categorizes areas into zones of high, medium, and low accessibility and assesses the distribution of infrastructure services across these zones. To this end, the accessibility of healthcare facilities based on travel time from different parts of the town has been computed using the following simple formula:

Where: f(d) is a function of distance, f(t) is a function of travel time.

Given the unauthorized nature of infrastructure delivery in informal built-up areas, some respondents were to some extent hesitant and suspicious to participate in interviewing and in the questionnaire. Accordingly, interviewing and collecting data from these individuals was handled with great caution after discussing and addressing the aim of the research and confirming that their responses are kept confidential. Participants were provided with information about the study objectives, procedures, and their rights before obtaining consent. Thus, data were collected when participants agreed and gave verbal consent to their involvement in the research.

3 Theoretical framework

Urban residents rely on infrastructure, but access often hinges on a settlement's legal status. In unauthorized areas, government agencies neglect their responsibilities, prompting informal actors to provide services, frequently at higher costs and lower quality (Allen, 2010; Yirgalem, 2008). In informal settlements like gecekondus, residents bypass formal rules to secure utility connections, with informal systems dominating infrastructure provision (Leitmann and Baharoglu, 1999). This study uses two frameworks—institutional analysis (North, 1990) and societal non-compliance (Scott, 1985; Tripp, 1997; Leduka, 2004; Vargas and Urinboyev, 2015)—to understand informal infrastructure delivery and actors' behaviors.

Institutional analysis differentiates formal rules, created and enforced by governments, from informal rules, developed outside official channels. Informal institutions emerge when formal systems are inadequate, impractical, or lack credibility (Helmke and Levitsky, 2004). Studies by Pamuk (2000) and Leitmann and Baharoglu (1999) highlight how informal arrangements substitute formal processes, governing land and service provision in squatter settlements.

Societal non-compliance, as described by Scott (1985) and Tripp (1997), is a form of resistance where marginalized groups use alternative systems to bypass state regulations. This defiance fosters informal economies and access to infrastructure, as seen in Tanzania and Malaysia. In Woldia, societal non-compliance drives urban growth by enabling informal systems to fill gaps left by ineffective formal institutions, illustrating the critical role of resistance in providing essential urban services to disadvantaged communities.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Results

The empirical findings of the study revealed that informal settlements often lack formal planning, infrastructure, and property rights. Informal settlements are dubbed as unauthorized. The town's infrastructure services are poorly developed and unevenly distributed over the vast peri-urban built-up areas. The extent of neglect of informal settlers by the town administration could be understood when one observes the distribution of public-funded urban infrastructure and social services. Informal settlements are often unplanned and lack basic infrastructure such as roads, water supply, and electricity. The absence of comprehensive planning and management frameworks can result in inefficient and inadequate infrastructure delivery, exacerbating socio-economic disparities and inequalities.

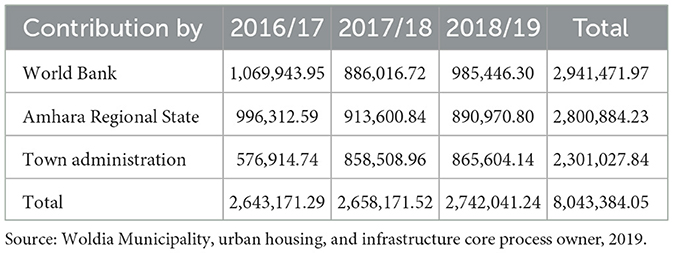

The empirical finding reveals that there are no infrastructure investments in areas that are considered informal not only the budget allocated by the State (Central, regional, and local) but also from the donor organizations such as the World Bank. The data obtained from urban housing and infrastructure core process owner of the municipality show that from the year 2016/17 to 2018/19, a total sum of $ US 8,043,384.05 was invested in the area of urban infrastructure, services, and related activities (including compensation payments to install infrastructure in the areas). Specifically, in the year 2017/18, a total sum of $ US 2,658,171.52 was disbursed to 34,952 beneficiaries in the town. The average amount of disbursed is equivalent to $ US 76.05 per beneficiary.

Woldia is one of the World Bank's housing and infrastructure project urban areas. Based on the data shown in Table 3, the largest share of financial expenditure of $ US 2,941,471.97 is credited to the World Bank followed by the Amhara National Regional State which accounted for an equivalent magnitude of $ US 2,800,884.23 and the remaining amount, $ US 2,301,027.84 by the town administration within the last 3 years. Such millions of amounts of money poured into road expansion, water, and sanitation projects, and municipal capacity buildings. With such an amount of financial flow, the municipality is supposed to install cobblestone roads, drainage, bridges, culverts, street lights, water supply lines, waste disposal sites, abattoir shade, etc.

Table 3. Monetary expenditure (in $ US) to infrastructures (including for compensation) in the town administration of Woldia (2016/17–2018/19).

4.1.1 Access to roads and paths

The primary purpose of this type of urban lifeline is to bring all the resources into the built environment of the town: housing, public buildings, markets, and workplaces as well as public facilities such as schools, clinics, wells, standpipes, public toilets, etc.

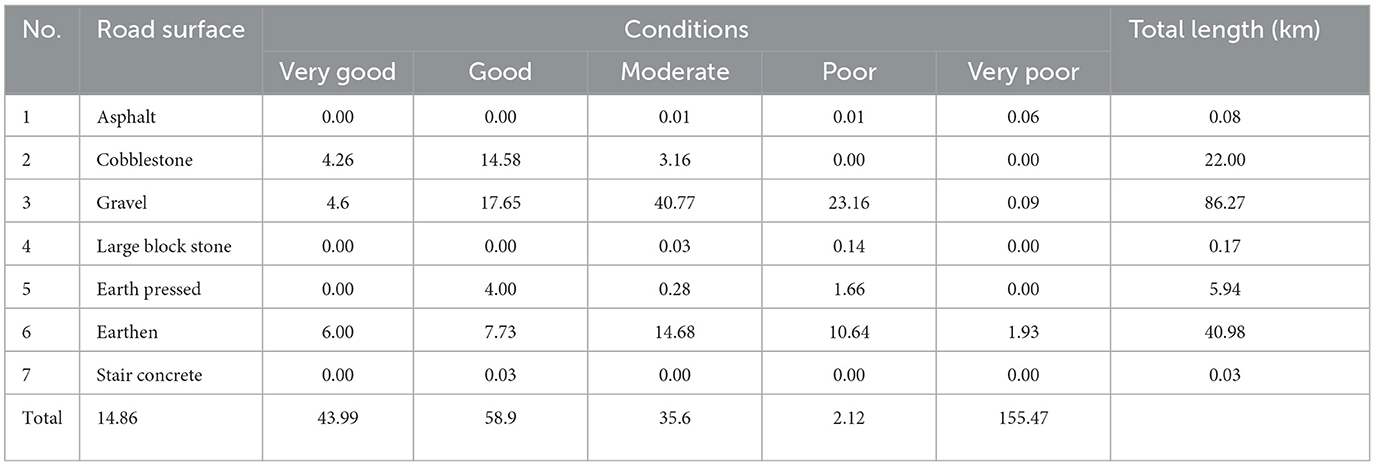

As per the data obtained from 2018/19 the Infrastructure Asset Management Plan document of Woldia municipality, there was a total length of about 182.25 km (including community roads) of the road in Woldia town administration. Furthermore, the asset management inventory revealed that of the total 155.47 km of road length of Woldia, about 86.27 km (56%) is covered with gravel followed by earth surfaced which accounted for 40.98 km (26%). On the other hand, Cobblestone roads and earth-pressed roads cover a total length of 22 km (14%) and 5.94 km (3.8%), respectively, as shown in Table 4. In addition to the above statistical shreds of evidence, there were about 20 bridges and 332 culverts in Woldia town administration.

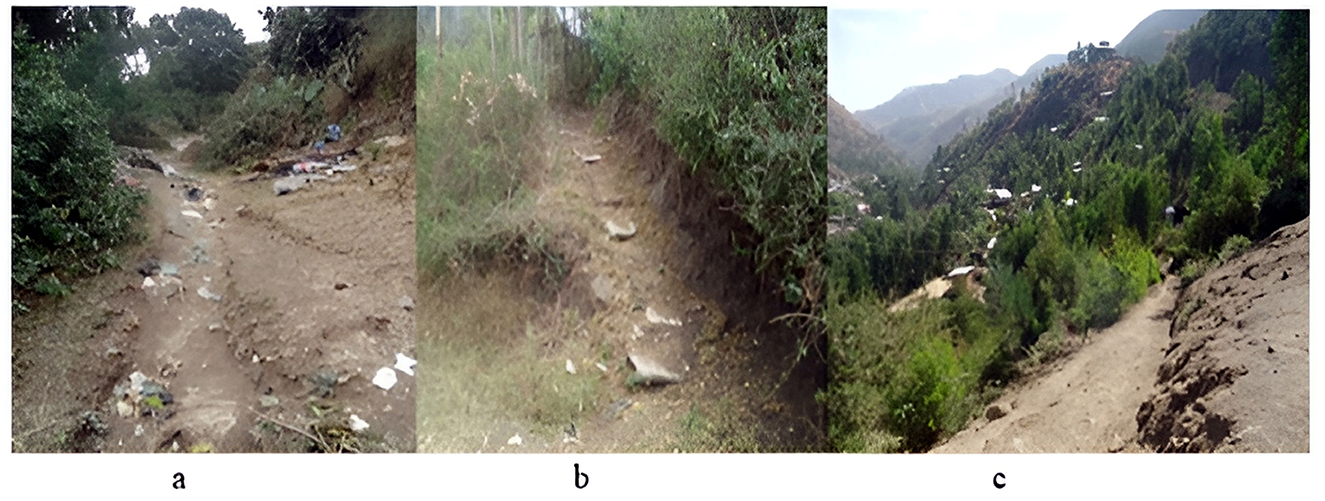

Given these official figures, and as far as the coverage in the formal areas is found at the lowest level (2.36%), it is not hard to imagine the situation of infrastructure in informal areas. Most of the routes in the peri-urban areas were unpaved or natural earthen roads. The findings of the field observations of the study also showed that most of the roads/routes/were footpath routes with poor quality. These naturally earthen roads deter movements, especially during the time of rain. When such places are not conducive for naturally earthen roads, the peri-urban settlers develop their routes. The peri-urban settlers for example fill cement sacks with soil and make terracing/steeping type of routes in front of their doorways (as shown in b) or they also open roads in collaboration with their communities as shown in the far-right image (c) of Figure 2 at their own cost.

Figure 2. Naturally earthen road (A), steeped footpath to the doorway (B), and community-developed road (C). Source: photo by the author, 2019.

Due to this, in peri-urban areas, walking is the most affordable form of movement for people to meet their daily needs. In addition to walking, Bajaj is the second most important means of transportation in the peri-urban areas wherein the community-opened road is accessible to do so. The findings of the study revealed that 63.3% of the passengers' trips are by walking whereas 34.8% are by motorized Bajaj. A small proportion of 1.9% of the settlers use bicycles as a means of transport.

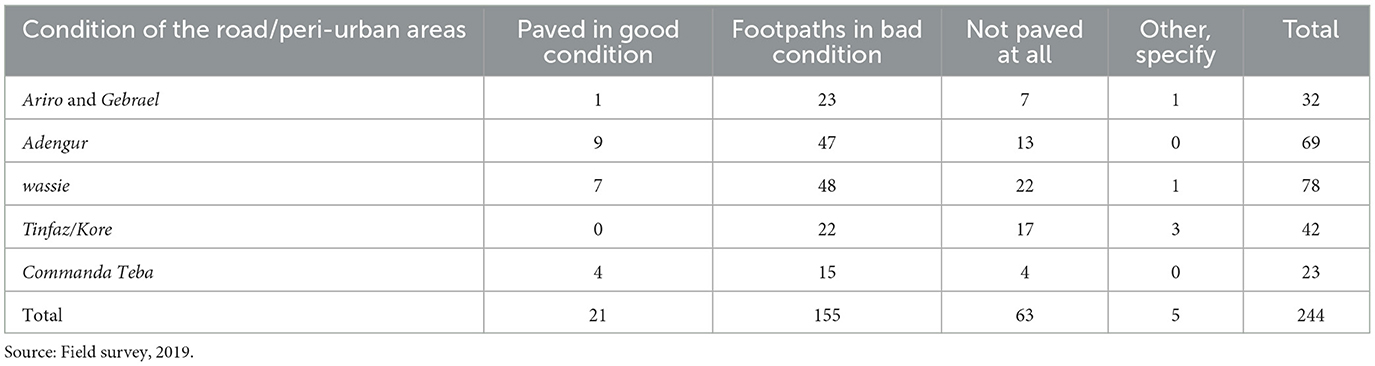

Sample peri-urban respondents across the study areas were asked to express their perception of the level/condition of the road in their surroundings. Accordingly, it is found that the majority of the respondents (63.52%) perceived that the road conditions in their surroundings were bad and 25% of the respondents perceived that the roads in their surroundings were not paved at all. 8.61% of the respondents perceived that the condition of the road was a paved road in good condition. There were variations in the perception of respondents like road conditions across peri-urban areas. Table 5 shows the variation in the perception of respondents across peri-urban informal settlements.

4.1.2 Water supply situation

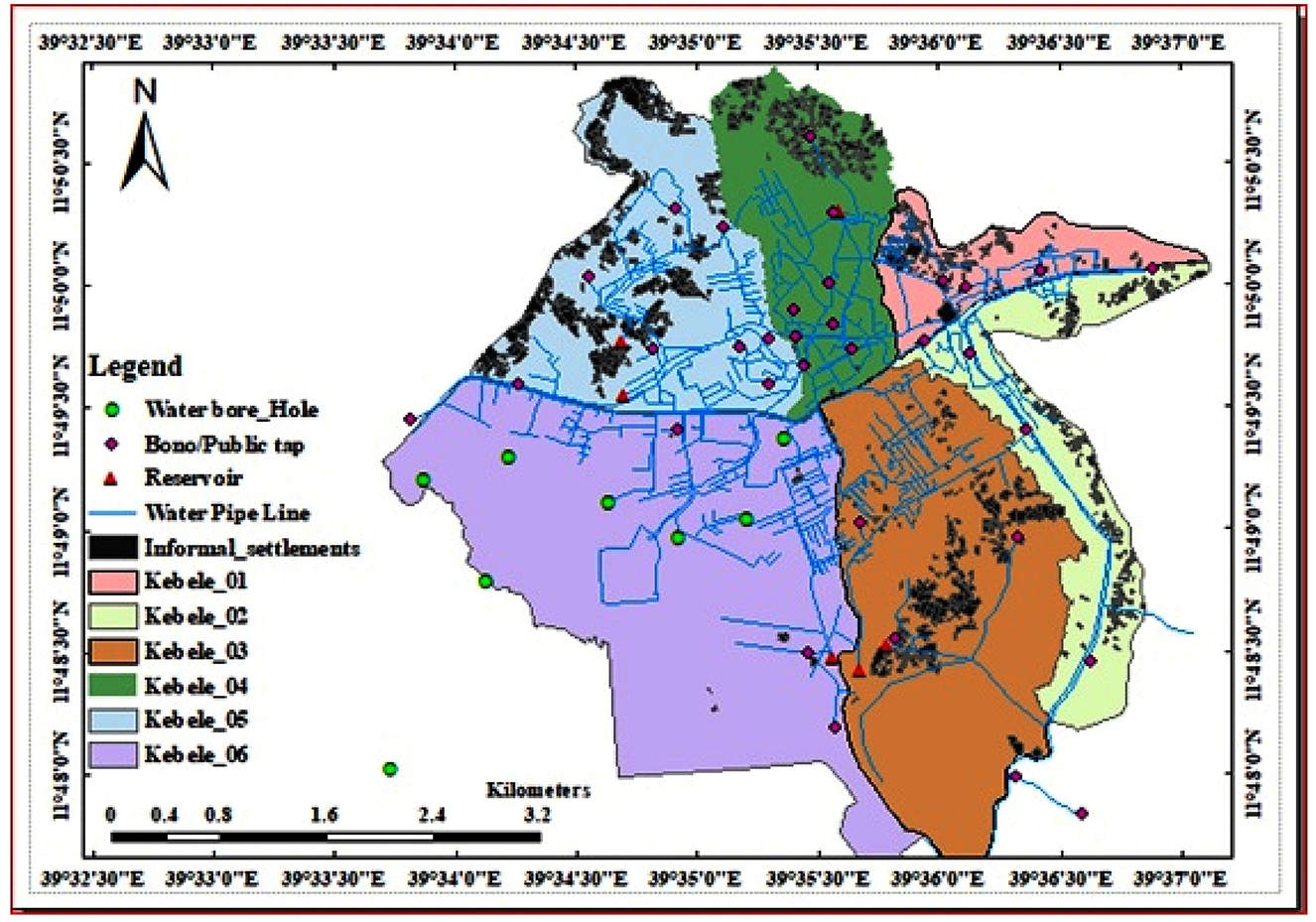

As per the data obtained from Woldia water supply and sewerage office, at the time of the data collection for this research, the town has an 18.90 km transmission network and 136.12 km main water distribution line. Furthermore, the town also has 37 public standpipes (Bobos), nine boreholes, and seven reservoirs. The water holding capacity of the reservoirs ranges from 100 to 500 m3. The distribution of Bonos, boreholes, reservoirs, and water pipelines is shown in Figure 3.

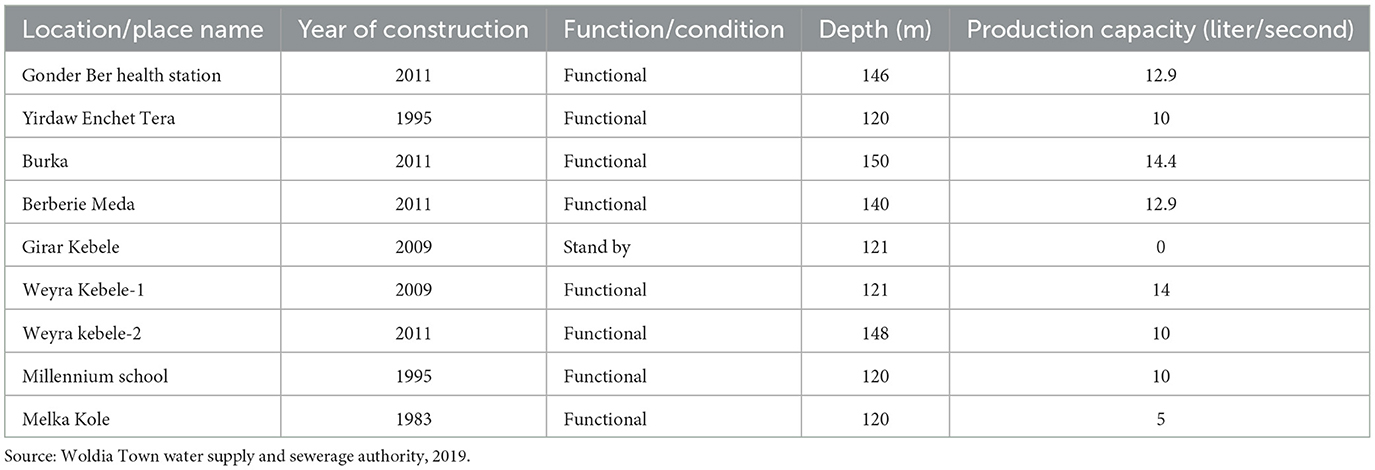

Nine bore wells have been dug at different locations in the town administration to supply potable water to urban dwellers as shown in Table 6. The production capacity of the wells ranges from a minimum of 5 L per second from the well of Melka Kole to 14.4 L per second at Burka.

As per the data obtained from Woldia water supply and sewerage office, the current mean total water production capacity by Woldia water supply and authority is 3,424 m3 per day. However, the total demand for potable water in the town is estimated at 5,103 m3 per day. This implies that well over 1,679 m3 per day of the town's demand for potable water remains unmet. Similarly, the town's water production capacity has never kept up with demand. Moreover, while the per capita demand of water per day per person is 60 L, the current actual mean per capita production of water is 41 L per day, almost 19 L of water per day shortfalls from the actual demand.

4.1.3 (In)formal water tariff and willingness to pay

Water tariff is the rate at which water is sold to a customer. As per regulation no. 94 of 2012, a water tariff is revised and issued by the regional bureau at least once in 5 years. The amount of tariff varies across different urban centers in the Amhara National Region State based on the grading of the urban center about potable water supply and sewerage services (Amhara National Regional State, 2012).

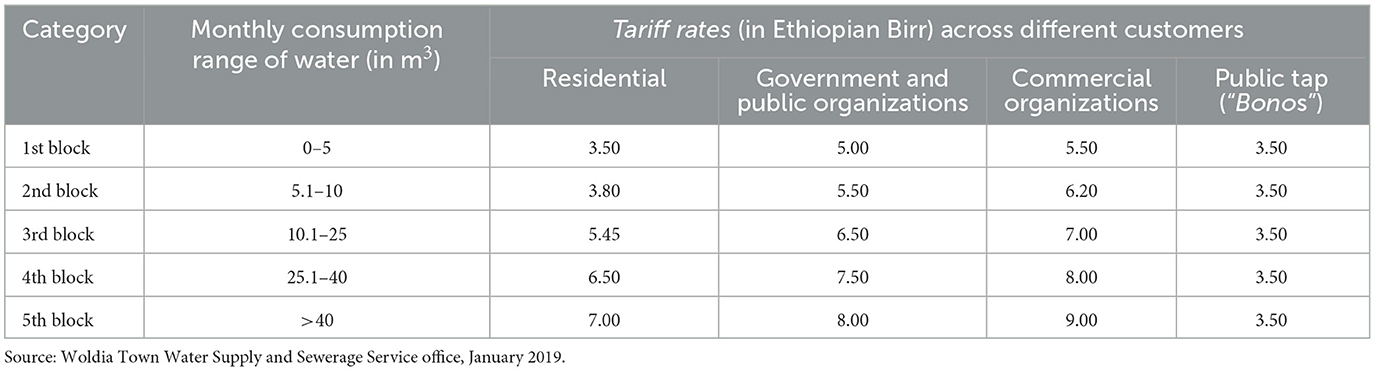

Based on the information elicited from the interview in Woldia water supply and sewerage office, the magnitude of water price (tariff) varies across different categories. That is, there is price discrimination among different customers as shown in Table 7. In the context of Woldia town administration, there are four customer categories: residential, government and public organizations, commercial organizations, and public taps (“Bonos”).

Table 7. Official water tariff rates across different water supply blocks and monthly water consumption ranges.

As one can notice from Table 7, all except the public tap or Bono users, the tariff rate is incremental or progressive. There are also five blocks. So, when water consumption is incremental, the cost for the water consumption is multiplied by the respective volume of water after dividing the total volume of water consumption into blocks. A hypothetical example will illustrate this point. Formal urban settlers with their private water meter are paying 3.50 Ethiopian Birr per 1 m3 or 1,000 L of water consumption. For example, if the amount of water consumption by a residential client is 110 m3 in August and 125 m3 in September, the difference in water consumption between the 2 months is 15 m3. Thus, the payment to be made by the customer is divided into three blocks. The first 5 m3 of water is computed on the first block tariff rate of Ethiopian Birr 3.50, the second 5 m3 by the second block tariff of Ethiopian Birr 3.80, and the third 5 m3 by the third block tariff of Ethiopian Birr 5.45. Hence, the total cost of water excluding the water meter renting service for September is summed as 68.75 Ethiopian Birr; i.e., (5 × 3.5) + (5 × 3.80) + (5 × 5.45). Therefore, in the residential area, a household that consumes water of 15,000 L (15 m3) is expected to pay 68.75 Ethiopian Birr ($ US 0.41) excluding water meter renting.

Since informal area residents have not waited for the government to act, one of the mechanisms of accessing water is via buying water from informal private water vendors. During the time of the research, those households who have no private water meter connection commonly purchase water at a price ranging from one to two Ethiopian Birr per 25 L (0.025 m3) or a Jerrycan of water. Jerrycan, with a water holding capacity of 20–25 L, is a plastic container widely used by households in the study area to fetch and store water. To put these figures into perspective and take the lower limit of this range, one Ethiopian Birr per 25 L, it implies that informal urban dwellers are getting water from private water vendors for 40 Ethiopian Birr for 1 m3. Similarly, taking the upper limit of this range, they are paying up to 80 Ethiopian Birr per 1 m3. As a result, the study points out that in informal settlements or in areas where there are no water lines or water meter installation, dwellers are forced to buy water from informal private water vendors at a cost ranging from 600 Ethiopian Birr (at the lower limit) to 1,200 Ethiopian Birr (at upper limit) for 15 m3 of water. That is, they are paying more for water in absolute terms than those with their private pipes.

Still, informal settlers who purchased water from private water vendors paid much more money than those who obtained water from public taps (Bonos). While those settlers who purchased water from private water vendors paid up to 1,200 Ethiopian Birr ($ US 42.12) per 15 m2 of water, those who purchased from public taps (Bonos) paid 300 Ethiopian Birr ($ US 10.53). It implies that the informal settlers without water meters pay more for their water consumption from private vendors than those who had private water installation or those who obtain water from public taps (Bonos) at a higher price. This implies that those people in the informal areas who purchase water from private water vendors had to pay almost two to four times more than those who had access to public taps (Bonos).

This inappropriate pricing and user charging are some of the major problems in the peri-urban areas of Woldia. The water is several times more expensive than publicly provided water. The difference between the price of water from private pipes and the price of water vendors reaches up to 1,645%.

That is) for 15 m2 of water consumption.

Despite pricing issues, private water vendors are serving the informal settlers (peri-urban settlers) at this cost.

It is important at this juncture to pay attention to public taps tariffs on reality. In actual terms, the water tariffs of public taps are constant, unlike other categories. However, customers are often purchasing water on a jerrycan daily. Users are not paying the price of water, for example, the first block, at once. During the time of the research, the price of a jerrycan of water including the service charge was 0.50 Ethiopian Birr. The tariff set by Woldia water supply and sewerage authority for a Jerrycan of water was 0.40 Ethiopian Birr. However, users are paying 0.50 Ethiopian Birr due to the absence of exchange. Now, it is a normal way of paying for a Jerrycan of Water at a Public tap. Soon after the printing of a metal coin of one birr, the 5 and 10 cents have almost disappeared from the market. This means that a household that purchases 15 m3 of water from a public tap within a month, for example, pays a total of 300 Ethiopian Birr.

On the face of it, the tariff rate of public taps seems so low and should not be high compared to other tariffs; but actually, it is not. It costs the second highest next to private water vendors to users. It was low had it been the customers had bought the water at block rates at once after the customer consumed the indicated volume of water. But this is not the practical way of buying water from public taps (Bonos). To this end, the first block tariff of public taps is attained once the user buys seven Jerrycans. Consequently, in addition to pricing issues, due to long queues on days and missing work, while fetching water from Bonos, they are less effective in serving the informal settlers. This is the reason that in areas with proximity to spring water, informal settlers are using water from this source for washing clothes and taking showers as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The informal settlers frequently take showers and wash clothes in the polluted stream water. Source: Field survey, 2019.

4.1.4 Electricity distribution, accessibility, and informal tariff in informal settlement areas

In Ethiopia, electricity is supplied by Ethiopian Electric Utility. The findings of the study showed that even if people in peri-urban areas are often in need of electricity for lighting and cooking, access to electricity is often unreliable, erratic, and expensive. That is, concerning the availability of electricity, central parts of the town administration dwelling units are connected to electricity power lines. However, peri-urban dwellers do not have the full benefits of electric power supply. The most remarkable feature of electricity in the town is uneven in its distribution over space. Most peri-urban areas do have a low level of electrification and the challenge is worse in informal areas. As a result, a large number of these residents come up with the decision to connect the power illegally. This has led to high levels of electricity use through illegal connections. The widespread sharing of a single electric meter by several urban dwellers is a common manifestation in the peri-urban areas of the town administration as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Examples of informal connections of electric wire from a single electric meter to neighborhoods. Source: Field survey, 2019.

During the time of fieldwork, the researcher observed that across the case studies, electricity connections were jury-rigged from a nearby house that is legally connected to the power network. The result is, thus, that informal dwellers often access electricity illegally from neighbors who are connected legally. Such connections are rampant in peri-urban areas. The overwhelming of illegal electricity connections may be because peri-urban settlers who want to use this utility have no legal access to it as their claim to the plot they occupy is not legally recognized or they fail construction permits from authority.

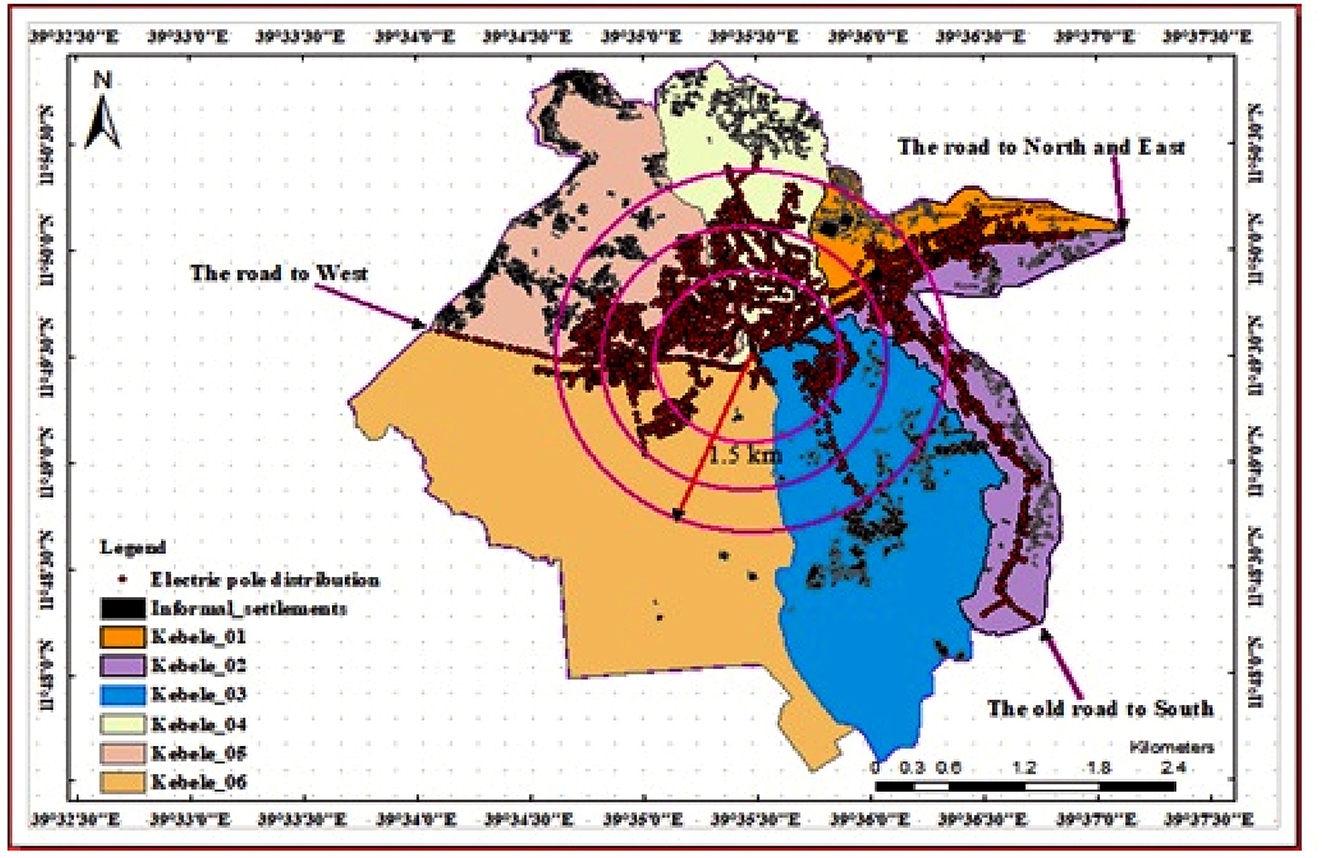

The uneven distribution of electricity in peri-urban areas is observed from the electric line distribution in the town. The electric line distribution indicates that the densest electric line distribution in Woldia appears predominantly in the northern half of the town within a 1.5 km radius from the center. A clear difference is perceived between places in the central and peripheral. Except within the 1.5 km radius from the center, electric line distributions have expanded following the three main highways in the direction of west, northeast, and southeast (Figure 6). This is also compounded by the fact that the spatial distribution of electric poles in the town declined significantly with distance from the center and major highways. In this sense, the analysis shows that areas close to the major highways and central parts have experienced a much greater distribution than areas that are farther away.

From the electric pole (pole) distribution, it is also important to notice that the outer areas have much lower access to electricity compared to their counter inner parts. Hence, there exist huge disparities between the inner and outer areas within the same town administration in the use of electricity.

Despite the distribution of electric poles in the peri-urban being minimal, the findings of the household survey revealed that the majority 226 (92.6%) use electricity as a source of light and the remaining 18 (7.38%) use other sources such as candles, firewood, flashlights and kerosene (via lamps). Of those households who used electricity light as a source of light, 119 (52.7%) did have their electric meter reading, while 96 (42.5%) of them did not have access to a formal connection to the Ethiopian Electric Utility supply lines, and the remaining 11 (4.9%) used shared electric meter.

Those households who are getting electricity through a connection from neighborhoods are, thus, forced to obtain their electricity possibly from a single electric meter that is connected to multiple neighborhoods. The implication is that in addition to the legal connections using different tactics, the jury-rigged form of connections is common. This can be dangerous and can cause fires or even damage electrical appliances in addition to inappropriate pricing and user charging. Here, mentioning a case of damaging electrical appliances at Adengur is valid. A man's response from Adengur who uses electric power by connecting from his neighborhood states that:

Once upon a time, there was an excess power of electricity in our neighborhood. Hence, because of the excess of the electric power supply, the TV sets, and refrigerators of many of us were damaged. We, the people demanded compensation for the damage of our equipment by the excess of electric power supply to the concerned body: Ethiopian Electric Utility of Woldia district. But the person in charge of the authority or district is saying ‘Where did you get the electricity?' The reason behind his saying was that some of the people were asking the Woldia district for the installation of electricity a month before damaging our equipment. In the end, since we lacked the legal grounds, we retrograded in enforcing the district for compensation.

The other finding shows that informal settlers are greatly affected during the windy and rainy seasons whereby informal connections are interrupted or ceased to work by the wind and rain. Due to these inconveniences, informal settlers are forced to stay without electricity for a substantial time until the connection is fixed. Besides this, because a large number of neighbors are sharing a single electric meter, it can cause overloading and ultimately stop functioning. In that case, to prevent this overloading, people often change their cooking and baking hours at other times, frequently from 9:00 to 11:00 local time (3:00–5:00 a.m.) in the morning when people are asleep. Households are using candles, firewood, kerosene via light, solar energy, and battery flashlights as a source of light when the electricity is absent or when the power is blackouts. This is the way of substituting electricity with the available alternatives as enabling strategies.

The study also showed that the main sources of energy that peri-urban households used for cooking were, in order of importance, firewood followed by electricity, and then charcoal. It implies that cooking by peri-urban households is dominated by firewood (43.9%), electricity (30.7%), charcoal (25%), and others (0.4%). The households use alternative sources of energy, such as fuelwood, charcoal, and kerosene in the absence of electricity or when they want to reduce electric consumption restricted by the owners to use the electricity for other appliances than lighting.

The findings of the study reveal that because of the unreliable, erratic, and frequent interruption of electricity, the majority of the peri-urban respondents were not only forced to use firewood or charcoal for household cooking but also the electricity that reaches a distance to such settlements is too weak to enable the households major electrical appliances.

4.1.5 Informal pricing of electricity in the informal areas

In addition to the prohibitive on the types of appliances that one could use, those who do not have access are forced to connect electricity from their neighbors even at higher costs. In line with this, Winkler et al. (2011) pointed out that where the formal system of service delivery fails to reach the poor, these households must resort to alternatives that often imply not only lower quality but higher costs. A woman, 32 years old, from Ariro underscores the seriousness of the situation as follows.

We connected the source of light from a single electric meter in the nearby neighborhoods. The total number of houses connected to this single electric meter is six including the owner. We agreed to use electricity only for lighting purposes but not for other utilities. But in reality, it was not happening. That is, lately, we confirmed that some people use it for other purposes which results in disagreements among us. First of all, the number of rooms and bulbs varies among us. Second, the number of electric appliances, such as TV sets, Refrigerators, stoves, irons, and so on vary which in turn leads the consumption to vary. Besides, this electric meter fluctuates frequently and stops working. Hence, due to this, the owner of the electric meter disconnects the electric wire from all of us. Then we were forced to entreat the owner with a middleman who is an ex-husband. But what made the situation worse than before was that each of us was requested to pay Birr 50 in addition to the cost of electricity that we would pay based on the electric meter reading. Since we do not have alternatives, we have been paying an extra 250 Ethiopian Birr per month for the last 8 months.

Still one needs to investigate how the source of energy pricing affects the peri-urban informal settlers. During the field survey, it was confirmed that in the peri-urban areas, whether they are formal or informal, residents without electric meters are paying for electricity use at a negotiable price ranging from 30 Ethiopian Birr ($ US 1.05) to 40 Ethiopian Birr ($ US 1.40) per 60 watts fluorescent bulb per month to the legal owner. Clients were restricted to using the power only for 4–6 h a day.

This implies that if a 60-watt fluorescent bulb gives light for about 6 h a day, the total power consumption is 0.36 kilowatt-hour of electricity for a day. That is, 60 × 6 = 360 wa = 0.36 kW. If the customer uses for a month, 30 days in the Ethiopian calendar except for the leap year, the total power consumption within a month, thus, is 10.8 kWh (0.36 KWh × 30 = 10.8 kWh). In the town, during the time of data collection, the legal price of electricity (base tariff) for the first block (up to 50 kWh) in the residential customer category was 0.273 Ethiopian Birr per kWh. Accordingly, the total electricity cost of a 60-watt fluorescent bulb that gives light for about 6 h within a month is 0.273 Ethiopian Birr ($ US 0.01) multiplied by 10.8 kWh plus a service charge of 1.68 Ethiopian Birr ($ US 0.06). Hence, the maximum possible cost of a single 60-watt fluorescent bulb including the service charge is 12.48 Ethiopian Birr ($ US 0.44). To this end, the informal settlers are forced to pay money for the same amount of energy consumption ranging from 18 to 28 Ethiopian Birr ($ US 0.63–$ US 0.98) above the normal price which creates a financial burden as the number of bulbs increases within the house. By inference, the informal electricity seller collects on average more than 12–22 Ethiopian Birr ($ US 0.42–0.77) from a single 60-watt bulb. This means that households without electric meter readings of their own tend to spend a larger portion of their income on electricity compared to those who have their electric meter reading. Consequently, consumption levels are often less than adequate. A respondent at Ariro considered his place of residence a “place of forgotten.” To the peri-urban informal settlers, resorting to informal options comes at a higher unit cost than the conventional systems because they have no legal alternatives to obtain the service.

4.1.6 Barriers to the formal provision of urban infrastructure services in informal areas

4.1.6.1 Political/legal barriers

In Woldia, key informants identified political and legal restrictions as significant obstacles to providing infrastructure to informal settlements. Government policies centralize control over essential services such as roads and electricity, considering them critical to national economic growth. Regulations, including Proclamation 86/1997 and Regulation 94/2012, limit infrastructure provision to settlements aligned with master plans and building permits. Consequently, informal areas are excluded from formal service delivery. Municipal authorities deprioritize these areas, citing non-compliance with planning regulations, leaving residents without access to basic infrastructure.

As a result, informal settlers must rely on private vendors who charge exorbitant rates—up to 1,200 Ethiopian Birr for 15 m3 of water. Even those using public taps (Bonos) pay 300 Ethiopian Birr for the same amount, significantly more than the 68.75 Ethiopian Birr paid by households with private connections. The lack of formal infrastructure and government oversight in informal areas perpetuates these disparities, reinforcing systemic inequalities in water access.

4.1.6.2 Economic barriers

Economic constraints further hinder infrastructure development in informal settlements. Public funds and donor investments, including those from organizations like the World Bank, are rarely allocated to unauthorized areas. Municipalities perceive these settlements as unworthy of investment, resulting in uneven infrastructure distribution and neglect. The absence of systematic approaches to financial support exacerbates the issue, with federal and regional funds failing to address the needs of informal settlers.

The extreme differences in water prices create a severe economic burden for informal settlers, forcing them to spend a disproportionate share of their income on a basic necessity. This financial strain exacerbates social and economic inequalities, as residents in informal settlements pay significantly more for water than those in formal housing areas. Limited access to affordable water services further marginalizes these communities, trapping them in a cycle of poverty where essential services are both scarce and costly.

4.1.6.3 Planning barriers

Urban planning practices exclude informal settlements, driven by objectives to prevent unregulated growth, enhance urban aesthetics, ensure resource equity, and avoid negative externalities. This planning philosophy reinforces marginalization, as informal areas are deemed incompatible with orderly urban development. Authorities fear that servicing these areas may encourage further unauthorized settlements.

Public taps (Bonos) provide a cheaper alternative to private vendors, but they come with several operational challenges that reduce their effectiveness. Long queues force residents to spend valuable time waiting for water, leading to lost income and productivity. Payment difficulties, such as a lack of small change, often result in users overpaying per jerrycan. Additionally, the pricing system is inefficient, as daily purchases prevent users from benefiting from lower block rates, making water more expensive in the long run. These planning failures make public taps an inadequate solution, despite their relatively lower cost.

4.1.6.4 Spatial/topographic barriers

Geographical challenges also impede infrastructure provision. Informal settlements in Woldia, often situated in hilly terrain, face difficulties in constructing roads, water pipelines, and electricity lines. Peripheral locations amplify these challenges, creating disparities in access and coverage between central and outlying areas. The difficult terrain and unplanned nature of informal settlements further complicate efforts to develop sustainable water supply systems, leaving residents dependent on unreliable and potentially hazardous sources.

4.1.7 Key actors, informal governance, social networks, and infrastructure access in informal settlements

In informal settlements, where state-led infrastructure provision is often absent or inadequate, local governance structures and social networks play a critical role in facilitating access to essential services such as water, electricity, sanitation, and transportation. To this end, informal settlers, faced with exclusion from formal infrastructure policies, develop alternative mechanisms to secure basic services, relying on collective action, informal agreements, and social capital as outlined below.

4.1.7.1 Informal service providers

Informal service providers play a crucial role in ensuring infrastructure access in areas where formal systems are either absent or insufficient. These actors include water vendors, who deliver water to households without direct municipal connections, and electricity brokers, who facilitate unofficial electricity access, often through informal grid extensions or shared connections. While their operations typically exist outside legal frameworks, they provide essential services to communities that would otherwise lack access. However, their services often come at a higher cost compared to formal providers, and the lack of regulation can lead to issues such as price exploitation, inconsistent service quality, and safety risks. Despite these challenges, informal service providers remain vital in bridging the gap between demand and the limitations of formal infrastructure systems.

4.1.7.2 Vigilante groups

In informal settlements where state institutions fail to provide adequate security and services, vigilante groups often emerge as alternative governance structures. Beyond their role in community protection, they influence infrastructure access by enforcing informal agreements related to service distribution, such as securing shared water points and electricity connections. They also regulate access to infrastructure resources, ensuring fair distribution and preventing monopolization by powerful individuals or groups. Additionally, vigilante groups negotiate with external providers, such as informal water vendors or electricity brokers, to secure more affordable and stable services for the community. They also mobilize residents for collective action, organizing road repairs or securing shared spaces for essential services like community meeting places.

4.1.7.3 Neighborhood committees

Neighborhood committees are informal governance structures formed by residents to address service provision and infrastructure maintenance. They coordinate community efforts to install, maintain, and repair local infrastructure, such as roads, drainage systems, and water supply points. Acting as intermediaries between residents and municipal authorities, they advocate for improved services and negotiate for the extension of formal infrastructure. These committees also manage informal service contributions, collecting voluntary fees to fund community-led projects like road paving. Furthermore, they help resolve conflicts over resource allocation by mediating disputes over access to water or electricity lines. In areas where government presence is weak, neighborhood committees often serve as trusted governance bodies.

4.1.7.4 Iddir (traditional community associations)

Iddir are voluntary community-based associations in Ethiopia, primarily established for mutual aid during emergencies such as funerals, but they also play a crucial role in infrastructure access. These associations pool financial resources to support collective infrastructure projects, such as road construction, and drainage system improvements. They provide financial assistance to community members for infrastructure-related expenses, including electricity connections or water storage installations. Additionally, Iddir organize labor contributions for communal service projects, such as maintaining public water points or rehabilitating pathways. Their effectiveness in mobilizing resources is rooted in strong social networks and community trust.

4.1.7.5 Equp (rotating savings and credit associations)

Equp are informal savings and credit groups that operate based on mutual financial contributions, primarily serving as economic support systems. However, they also facilitate infrastructure access by providing financial support for individual or collective infrastructure investments, such as household water connections or drainage system improvements. By offering low-interest loans for infrastructure-related expenses, Equp reduces financial barriers to service access, making them an essential alternative financial institution for marginalized populations lacking access to formal banking services.

4.1.7.6 Debo (traditional collective labor system)

Debo is a traditional Ethiopian practice where community members voluntarily contribute labor for large-scale communal or individual projects. In the context of informal infrastructure access, Debo plays a critical role in constructing and maintaining essential infrastructure, such as repairing roads, digging water wells, and installing communal sanitation facilities. It is also instrumental in organizing emergency responses, such as clearing blocked drainage systems after floods or reinforcing houses affected by infrastructure failures. By relying on community labor instead of external contractors, Debo significantly reduces infrastructure development costs, demonstrating the strength of community solidarity in addressing immediate infrastructure needs.

4.1.7.7 Elders (community leaders and mediators)

Elders are respected figures in informal settlements who act as mediators and decision-makers in community affairs, particularly in matters of infrastructure access. They negotiate with authorities and service providers to secure improved infrastructure services, ensuring that the community's needs are addressed. Elders also mediate disputes over land, infrastructure maintenance, and service access, helping to maintain fairness in resource distribution. Additionally, they provide guidance on traditional resource management practices, such as sustainable water use and road maintenance strategies. By leveraging their influence and credibility, elders mobilize community participation in infrastructure projects, particularly in communities where trust in formal institutions is low.

4.1.7.8 Religious leaders

Religious leaders play a crucial role in shaping social behavior and mobilizing collective action, which extends to infrastructure access. They raise awareness about the importance of infrastructure development and encourage community participation in service improvement projects. Religious leaders also facilitate negotiations with authorities, advocating for improved infrastructure in marginalized settlements. Additionally, they organize charitable contributions for infrastructure-related initiatives, such as installing water sources or electricity lines in underserved areas. Their significant moral authority helps unite communities around shared infrastructure goals, fostering collective efforts toward development.

4.1.8 Copying strategies from institutional analysis and societal non-compliance perspective

Informal actors, despite operating outside formal regulatory frameworks, play crucial roles in shaping infrastructure development and service provision in underserved areas. From an institutional perspective, their activities highlight the limitations of state-led infrastructure planning and the adaptive responses that emerge in contexts of institutional voids. Informal settlers employ various strategies to circumvent exclusion from formal service networks, often engaging in acts of non-compliance to secure essential infrastructure.

One key mechanism is collective action, where communities mobilize resources and labor to construct and maintain roads, drainage systems, and sanitation facilities in defiance of state neglect. Such initiatives reflect an alternative governance structure, wherein informal institutions substitute for absent or inefficient formal mechanisms. Additionally, settlers negotiate with state actors and private service providers, leveraging both formal and informal channels to access utilities such as water and electricity. Where state services are insufficient or entirely absent, informal service markets proliferate, with private vendors filling the gaps in transportation, energy, and water provision—often operating in legal gray zones or through extralegal arrangements.

Traditional institutions, including community associations and religious networks, function as parallel governance structures that provide financial, organizational, and logistical support for infrastructure projects. These adaptive strategies reveal the agency of informal communities in resisting infrastructural exclusion and navigating state-imposed constraints. Rather than passive recipients of state neglect, informal settlers actively contest and reshape infrastructural landscapes, highlighting the interplay between institutional failure and grassroots-driven non-compliance.

4.1.9 Comparative assessment of peri-urban study areas

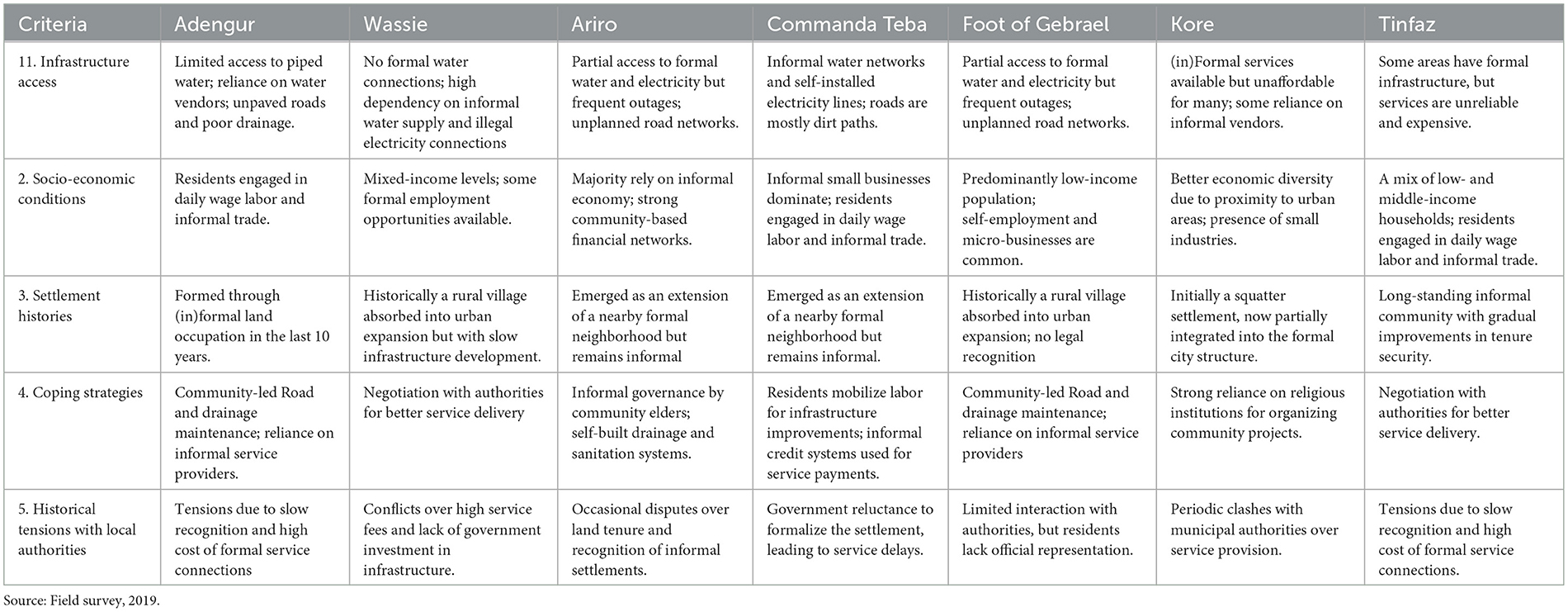

Table 8 presents a comparative analysis of peri-urban settlements Adengur, Wassie, Ariro, Commanda, Teba, Foot of Gebrael, Kore, and Tinfaz based on five key criteria: infrastructure access, socio-economic conditions, settlement histories, coping strategies, and historical tensions with local authorities. These factors influence the daily lives of residents and shape their interactions with formal governance structures.

4.2 Discussion

It was found that whilst some respondents claimed that they received no infrastructure, the research findings showed that governing infrastructure by informal institutions has turned out to be a massive force in the informal peri-urban areas. Many times, there is a conflict between the formal laws and the informal institutions, especially when it comes to the infrastructural provisions. The empirical findings of this study also revealed that informal access and securing of infrastructures are happening out of the ambit of the formal legal regime. Local authorities denied informal settlers access to a wide range of basic infrastructure services. The results of other studies showed similar trends as well (Amoako and Boamah, 2016; Hardoy and Satterthwaitet, 1986; Potter and Lloyd-Evans, 2014; Winayanti and Lang, 2004; United Nations, 2018; Harris, 2017; Perlman, 2010).

In the study of peri-urban areas of Woldia, though the informal settlement laws did not put particular restrictions, the sectoral laws such as building regulations, electricity, and water supply regulations strictly prohibit the delivery of infrastructure to such areas. Moreover, the spatial, economic, social, political, and legal barriers greatly deter informal dwellers from making private provisions for basic infrastructures. This was because local government officials often banned extending infrastructure access to informal settlements in their development schemes as such settlements are coming into being with no government official approvals. The low funding dedicated to infrastructure investment and development has aggravated this challenge in most of these informal settlements to meet the growing demand. A municipal urban planner addressing the provision of amenities to informal areas stated, “As a municipality, we cannot extend infrastructure to settlements that have not been legally recognized, as doing so would contradict urban development policies.”

The research output showed that financial expenditures in the form of investment are directly invested in areas that are considered legal (planned) by the town administration and in line with the structural plan. The underlying insight here is that it legitimizes the separation of formal areas from informal areas. This means that the existence of a master or structural plan, for example, is one of the necessary preconditions for infrastructure extension in the peri-urban areas. Local authorities achieved this through a spatially discriminated incentive system that favors the planned areas and disfavors the informal settlements which is similar to Piece's empirical work (Pierce, 2017). This conditionality is one of the legal barriers for informal settlers to obtain the necessary finance to extend physical infrastructure in their area of residence. That is why many of the informal settlements in peri-urban areas of Woldia were not equipped with the basic infrastructure of varying quality and quantity. This is consistent with the situation that Allen considered as ‘peri-urbanization of injustice (Allen, 2010), or treating the unequal unequally (Nguyen et al., 2017). The implication is that informal settlements were neglected and marginalized, leaving them out of the mainstream of the economy. Similar trends were observed in other studies (Potter and Lloyd-Evans, 2014; Winayanti and Lang, 2004; Harris, 2017; Perlman, 2010). To this end, informal settlements are settlements with physically proximate but institutionally distant. This lack of access undermines residents' quality of life, exacerbates socio-economic inequalities, and hampers efforts to improve living conditions through infrastructure development.

The challenges of accessibility of roads in informal areas, for example, are multifaceted and can significantly impact the wellbeing and development of residents. In consequence, informal settlements are often characterized by narrow pathways, uneven terrain, and a lack of proper roads or pathways. This physical layout makes it difficult for residents to access essential infrastructure such as water points, sanitation facilities, healthcare facilities, schools, and transportation hubs. This lack of connectivity makes it challenging for residents to travel to work, school, healthcare facilities, and other essential services, limiting their opportunities for economic and social mobility. More importantly, the lack of paved roads makes it unsafe for pedestrians and vehicles to navigate the area, especially at night. Inadequate or poor road infrastructure can also hinder emergency response and service delivery efforts.

The findings of the study also revealed that areas close to the major highways and central parts of Woldia are mainly infrastructure-served areas. It can mainly relate this to the primary focus on the planned residential areas, for example, with electricity, though may also be related to major economic and facilitating business. The peri-urban areas of towns, which often lie outside the formal infrastructure network of the town, are characterized by sporadic water supply, and frequent electricity outages in comparison to the central area of the town.

Because of these neglected and marginalized situations, some observers suggest that despite years of research and the many advances that have been made in both theory and practice relating to urban informal settlements, the “effects of stigmatization and discrimination are still felt by millions of urban dwellers today” (Lombard, 2014, p. 4). These urge informal settlers to set the accessing tactics of these infrastructure services using various enabling strategies (Sinharoy et al., 2019; Narayanan et al., 2017). Thus, informality is at play in the matters of infrastructure delivery via negotiation, collaboration, political deal-making, and use of organizational and financial strategies depending on the set of assets (natural, physical, human, and financial) and entitlements that individuals possess and whether they can mobilize them in times of challenge (Pierce, 2017; Sinharoy et al., 2019). In this regard, it means that urban policy and program responses of governments in developing countries to deficiencies in urban shelter, services, and infrastructure have been disjointed and ad hoc (Winkler et al., 2011).

This requires planning by informal settlers. As a result, based on the results of key informants and focused group discussions (FGDs), informal dwellers resort to ad hoc informal means to access infrastructures through which individuals and institutions interact, exchange information, exert impact, or are influenced and trade infrastructure services. In this regard, the study outlines the options that informal settlers use to respond to the deficiencies of basic urban infrastructure services. Those settlers who were denied access to formal infrastructure provisions have responded by seeking substitutes, though the actual (per unit) costs are high relative to the costs of services provided through formal networks. In this regard, informal settlers get urban infrastructures and services either illegally or at higher prices. Accordingly, households without access to public pipe water obtain water from a combination of sources: rivers and streams or from a range of (in)formal providers (e.g., public taps, water kiosks, streams, water vendors).

A key informant, 41 years old, discussing the prevalence of informal service providers in Adengur stated that:

“Water vendors and electricity brokers fill the gaps where the government cannot provide. Instead of criminalizing their work, the authority should explore ways to regulate and integrate them into the formal service network. They are often more efficient at reaching the most vulnerable populations than the public/state.”

In the same manner, many of the informal settlers continued to rely on non-public services of electricity. They substitute electricity for charcoal, firewood, and torchlight. Such infrastructure deliveries (substitutes) by the informal private providers in informal areas are beneficial as it does not confer the status of approval of a settlement that is often perceived with the state delivery of infrastructures. The findings of the study revealed that across the case study informal settlement areas, there are no sewer facilities. It was found that people usually limit their water use, and consequently, occupiers are more likely to rely on open space dumping and on-site sanitation mechanisms.

Yet, the study found that peri-urban dwellers without access to formal infrastructure provisions often pay exorbitant prices for water and electricity to their sellers. For example, across the case study areas, urban households without access to piped water often pay more than 17 times the piped water price to buy water from informal private vendors. Similarly, households without access to electricity often pay more than 3 times the electricity price to buy electricity from informal vendors per a single 60-watt electric bulb. Thus, the strategies people use are partially feasible substitutes for public services. However, as the findings of the study disclose, the bulb price for illegal electricity is not the same across all peri-urban informal settlements. Given that quality fluctuates with distance from the network, the price for illegal electricity is not uniform. For these reasons, the sellers of informal connections impose an additional charge of 18–28 Ethiopian Birr per 60-watt fluorescent bulb per month to their legal owners. This amount is determined by the physical distance and topography of each peri-urban informal settlement.

To this effect, for example, households are using candles, firewood, kerosene via light, solar energy, and battery flashlights as a source of light when electricity is absent or when power is blackouts. This is the way of substituting electricity with the available alternatives as enabling strategies. Similar trends were also observed in other studies (Mutisya and Yarime, 2011).

Some of the foremost local actors who are playing a leading role in ensuring access to basic infrastructures include informal private water and electricity vendors, corrupt local state actors, consumers (buyers), lobby groups (special interest groups), and people in local traditional institutions. In the absence of appropriate official rules, the suppliers and clients framed coping strategies that enabled the informal settlers. In Woldia, the roles of informal service providers, local leaders, and community networks reflect broader patterns of institutional adaptation (North, 1990) and non-compliance (Scott, 1985) in response to infrastructural and governance deficits. From an institutional analysis perspective (North, 1990), these actors emerge as alternative institutions that fill the void left by weak or absent state structures. From a societal non-compliance perspective (Scott, 1985), their actions illustrate how communities defy or circumvent formal regulations to meet their essential needs. The interplay between informal service providers, local leaders, and community networks in Woldia exemplifies the dynamic relationship between institutional shortcomings and grassroots adaptation. Through both compliance and non-compliance, these actors negotiate their infrastructural realities, demonstrating that informal governance is not a mere byproduct of state failure but an active force reshaping urban development (North, 1990; Scott, 1985).

The study findings confirmed that a variety of factors shape the actors' strategies (e.g., financial resources, social capital, access to government institutions, etc.); no actor is powerless. A similar procedure was used to deliver urban infrastructure in informal areas (Scott, 1985; Tripp, 1997; Leduka, 2004; Vargas and Urinboyev, 2015).