Abstract

The coarse spatial resolution of Global Climate Models (GCMs) makes the assessment of future hydrological dynamics particularly challenging over complex terrain regions like High Mountain Asia (HMA). Climate downscaling is therefore essential to better understand the impacts of climate change on water resources in HMA. Owing to this need, we investigate the effect of downscaling climate models on the hydrological projections of glacierized catchments in HMA with a specific focus on streamflow projections, relative contribution of streamflow components, and peak flows over five study basins in HMA. For this, four CMIP6 GCMs under SSP5-8.5 scenario were downscaled using two statistical techniques—parametric Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) matching and Generalized Analog Regression Downscaling (GARD)—and used for streamflow simulations using the Hydrological Model for Distributed Systems. The original GCMs exhibited a wet bias across all basins in the dominant precipitation season and a cold bias (−4.3 °C to −13.6 °C) over the glacier-dominated basin. CDF matching and GARD performed well in reducing the bias from original GCMs over high precipitation seasons. Future precipitation increases over winter and spring seasons for basins in Pakistan and over summer and fall seasons for basins in Nepal and Bhutan. An increase in rainfall-runoff component is anticipated in the future across all basins, while the contribution to streamflow from snowmelt decreases over central and eastern basins. The overall water availability across the basins is projected to increase, along with extreme flows. The results revealed the impact of choice of downscaling techniques and GCMs on the catchment climatology, affecting the hydrological projections.

1 Introduction

The impacts of global climate change are profound and multifaceted with adverse effects on the spatial, temporal, and quantitative variations of hydrometeorological characteristics (Kim et al., 2014). Increased temperature and changes in precipitation will alter the hydrological regime of the catchments impacting the overall water availability for billions of people. The effect of climate change is more pronounced over complex topography regions like High Mountain Asia (HMA). Rapid decline and limited restoration of glacial mass alter the regional hydrology and intensify natural hazards (Yang et al., 2023; Rounce et al., 2023; Hugonnet et al., 2021; Hock et al., 2019) impacting livelihoods and infrastructure. Hence it is crucial to have a comprehensive understanding of the future changes in Earth’s climate and to quantify its potential consequences in the context of high mountain regions.

Global Climate Models (GCMs) are generally used to provide an estimate of future climate by simulating the global climate system response to changing greenhouse gas concentrations (IPCC, 2013). GCMs are mathematical models representing the Earth’s climate based on complex processes and their interactions (Tehrani et al., 2022). However, in most cases, the coarse resolution of GCM outputs makes them inefficient in representing small-scale climate variability and thus limits their application to regional climate studies, especially for complex terrains like HMA (Di Virgilio et al., 2022; Gebrechorkos et al., 2019; Gutmann et al., 2012). In addition, GCMs are also known to have significant biases and uncertainties in representing historic and future climate, especially extreme events (Wu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2020; Buser et al., 2010; Wilby and Harris, 2006).

To overcome the limitation of spatial resolution of GCMs and to represent the variability in climate effectively, we depend on different downscaling techniques. The commonly used downscaling approaches may be broadly classified as statistical downscaling techniques which utilize a statistical relation between high-resolution observed historic climate data and climate model output to disaggregate coarser GCM output to higher spatial resolution; and dynamic downscaling techniques where high-resolution Regional Climate Models (RCMs) are used to improve the climate model resolution with boundary conditions from GCMs (Bozkurt et al., 2019; El-Samra et al., 2018; Xu and Yang, 2015). One of the major limitations of dynamic downscaling is the significant computational time and resource requirements (Alizadeh, 2022; Xu et al., 2019). The simplicity of use and comparable performance of the statistical downscaling techniques make them a popular alternative in climate change impact analyses (Michalek et al., 2023; Emmanouil et al., 2023).

Statistically downscaled GCMs combined with hydrological models have been extensively used to assess the impacts of climate change on water resources in HMA. For instance, Chen et al. (2012) compared two statistical downscaling techniques combined with two GCMs and two hydrological models over the upper Hanjiang basin in China. The results indicated large variation in simulated runoff outputs from hydrologic models using the same GCM downscaled by different statistical techniques. A study done by Faiz et al. (2018) evaluated the performances of multiple hydrological models driven by bias-corrected precipitation estimates from multiple GCMs over northeastern China and revealed that bias correction significantly improved the performance of GCMs against observational data. Yaseen et al. (2020) evaluated the effects of statistical downscaling of temperature and precipitation on the runoff generated using the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) in the transboundary Mangla watershed in Pakistan. The results indicate that the annual streamflow will increase in the future attributing to an increased temperature for snow melting in the Mangla watershed.

A recent study done by Usman et al. (2022) investigated the suitability of linear scaling (LS) and empirical quantile mapping (EQM) bias correction methods to generate present and future precipitation, temperature, and streamflow over the Chitral river basin in Pakistan. Raw and bias-corrected NEX-GDDP simulations were used to generate streamflow projections from HBV-light hydrological model. The results highlight that the high-resolution NEX-GDDP has significant biases for precipitation and temperature over the study area, leading to unrealistic streamflow simulations, compared to the observed data over the historical period. A study done by Mannan Afzal et al. (2023) on the response of glaciers to climate change over the Hunza basin in Karakoram revealed that the peak glacier runoff is expected near mid-century as the small glacier volume will drop by 90%. Adnan et al. (2024) evaluated the spatiotemporal variability in streamflow components simulated using the University of British Columbia Watershed Model and their relative contributions to the streamflow of the Gilgit river basin in Pakistan. An ensemble mean of three GCMs was bias-corrected using the Generator for Point Climate Change model to generate future streamflow simulations. The results indicate an early onset of snow/glacier melting in the future due to an increase in summer air temperature and a decline in winter precipitation.

The above-mentioned studies, but not limited to, emphasize the need to choose appropriate downscaling methods and hydrological models for the proper representation of future climate and to understand its hydrological implications over complex terrains. Moreover, they highlight the fact that globally available downscaled climate data, can still present significant bias over certain regions (such as HMA) and regionally tuned datasets should be sought for climate change impact assessments. As part of the NASA High Mountain Asia program,1 we have developed, using different techniques, a set of downscaled climate data that are focused on HMA. In this study, we present a rigorous evaluation of the impacts and importance of downscaling climate forcing for assessing future projections of the hydrologic response of glacierized catchments in HMA and understanding the implications of uncertainty in climate projections. Specifically, we aim to answer the following research questions: (1) What is the uncertainty of climate forcing due to GCM and downscaling technique in the HMA region? (2) What is the dependence of the hydrological projections of glacierized catchments in HMA on climate models and downscaling techniques? (3) What are the impacts of climate forcing uncertainty on various aspects of hydrologic response such as (a) total streamflow, (b) the relative contribution of streamflow components, and (c) extreme values of streamflow? While, as mentioned previously, there are several works on climate change impacts on hydrologic response in different regions of the world, we want to highlight that the HMA region has not been extensively researched on this topic. Given its complex topography and significant importance, in terms of water resources, there is a need for additional investigations on hydrologic projection and climate uncertainty. Accordingly, the main focus of our study is on the effects of climate downscaling on the hydrological projections with specific emphasis on changes in water resource availability, basin hydrological processes, and future flood risks. Additionally, the elevation dependence of original and downscaled climate and simulated streamflow is also analyzed to understand how projected changes will manifest along the steep gradients of the region’s terrain.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

In this study, we focus on understanding the impacts of climate change on five glacierized basins across different parts of HMA (see Figure 1). These basins are chosen based on the availability of observed streamflow data.

Figure 1

(A) Extent of HMA showing the locations of the five study basins. Land use maps of (B) GRB, (C) SRB, (D) MRB, (E) BRB, and (F) PRB, derived from GlobeLand30 (http://www.globallandcover.com).

Gilgit and Shigar River Basins (GRB and SRB) located in northern Pakistan have an area of 13141.6 km2 and 7,139 km2. GRB has an elevation ranging from 1,457 m to 7,151 meters above sea level (m a.s.l) and is characterized by brief hot summers and cold winters (Ali et al., 2017). According to the glacier outlines available from version 6.0 of the Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI6.0), GRB consists of 1700 small glaciers covering about 18% of the total area. The river Gilgit is the biggest contributor to the Indus River, with a hydroelectric power potential of about 50,000 MW (Hussain, 2020). The elevation of SRB ranges from 986 m to 8,546 m a.s.l. with 847 glaciers (covering around 40% of the total area) within the basin. Both GRB and SRB are snowfall-dominated catchments influenced by upper-level westerlies and summer monsoons (Latif et al., 2020). The streamflow contribution in GRB is influenced by snowmelt and to some extent glacial melt, whereas for SRB glacial melt is the major streamflow contributor (Latif et al., 2021). The daily streamflow observations for GRB and SRB are available from the Water and Power Development Authority-Surface Water Hydrology Project (WAPDA-SWHP), Pakistan.

Marsyangdi and Budhigandaki River basins (MRB and BRB) in Nepal have an area of 4,059 km2 and 3881.2 km2, respectively. There are 348 glaciers in MRB and 330 in BRB. MRB consists of two existing and three planned hydroelectric power plants (Mudbhari et al., 2022; Khadka and Pathak, 2016), and a feasibility study for a potential hydropower plant in BRB has been completed (Devkota et al., 2017; Budhigandaki Hydroelectric Project Development Committee (BHPDC), 2015). Both basins are dominated by the Indian Summer monsoon with a temperate climate characterized by dry winters and warm summers (Kayastha and Kayastha, 2020). Daily streamflow observations for MRB and BRB are available for the years 2004–2010 and 1980–2015, respectively.

Punatsangchhu River Basin (PRB) located in central Bhutan is a rainfall-dominated catchment with an area of 9,655 km2 and 297 glaciers. Two significant hydroelectric powerplants—the Punatsangchhu Hydroelectric Project Authority - PHPA-I and II (1,200 MW and 1,020 MW, respectively) along the river Punatsangchhu are under construction and are anticipated to generate 5,670 and 4,357 million units of electricity per year, respectively. The streamflow observations for PRB are available for the years 2007 to 2022.

2.2 Datasets

2.2.1 Reference datasets

We used the high-resolution precipitation dataset (5 km/1 h) from Maina et al. (2022) aggregated to a daily scale (hereafter Pref) as the reference for downscaling daily precipitation from the GCMs and to evaluate the variability of precipitation in the historic period. Pref is developed by blending IMERG, ERA5, and CHIRPS and is available for the years 1990–2014 (Maina et al., 2022). A downscaled ERA5 temperature at 5 km (hereafter Tref) is used as the reference temperature for downscaling near-surface air temperature from the GCMs (Xue et al., 2020). Both Pref and Tref datasets have been validated using available in-situ data across HMA. Dollan et al. (2024) conducted an extensive evaluation of the individual datasets as well as blended Pref datasets and found a higher correlation for the ensemble product with ground observations. While a resolution of 5 km may still be considered coarse, given the complex topography of the region, they correspond to one of the highest available resolutions of climate data for HMA.

2.2.2 Global climate models

In this study, we compare the model simulations obtained using four GCMs (see Table 1)—original and downscaled—as the input to the hydrological model. The models were chosen based on the common availability of their statistically downscaled versions using two different techniques (explained in Section 2.2.3 below). The current version of the Euro-Mediterranean Centre on Climate Change- Earth System Model (CMCC-ESM2) is developed by coupling climate coupled model CMCC-CM2 (Cherchi et al., 2019) with the Biogeochemical Flux Model (Vichi et al., 2015). Compared to the previous versions, CMCC-ESM2 fully represents the global carbon cycle with the inclusion of marine biogeochemistry (Lovato et al., 2022). The Higher-resolution Version of the Max Planck Institute Earth System Model (MPI-ESM1.2-HR) is developed by the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Germany, and has twice the horizontal resolution in its atmospheric component compared to its precursors, leading to an improved regional atmospheric dynamics (Müller et al., 2018). The Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model version 2.0 (MRI-ESM2.0) developed at the Meteorological Research Institute (MRI), Japan is an integration of interactive models for aerosol and atmospheric chemistry into the atmosphere–ocean coupled model (Yukimoto et al., 2019). The second version of the Norwegian Earth System Model developed by the Norwegian Climate Center is based on the Community Earth System Model (CESM2.1) with differences in the ocean biogeochemistry and atmospheric aerosol module (Seland et al., 2020). In this study, we have used the atmospheric medium-resolution version of the model (NorESM2-MM). The precipitation, temperature, and streamflow simulations based on these selected GCMs are hereafter referred to as ‘CMCC-based’, ‘MPI-based’, ‘MRI-based’, or ‘NoR-based’.

Table 1

| Modeling centre and country | Model name | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Euro-Mediterranean Centre on Climate Change- Earth System Model | CMCC-ESM2 | 1.25° × 0.94° |

| Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Germany | MPI-ESM1-2-HR | 0.94° × 0.94° |

| Meteorological Research Institute (MRI), Japan | MRI-ESM2-0 | 1.13° × 1.13° |

| Norwegian Climate Centre, Norway | NorESM2-MM | 1.25° × 0.94° |

List of CMIP6 models used in the study.

2.3 Methodology

2.3.1 General framework

Figure 2 shows the general methodological framework adopted in this study. In order to assess the significance of downscaling for hydrological applications over glacierized catchments in HMA, we used four original and downscaled GCMs as input to the Hydrological Model for Distributed Systems (HYMOD_DS, explained in Section 2.3.3). First, HYMOD_DS was calibrated for the five basins using Pref and Tref as input. The list of calibrated parameters for each basin and the results of calibration/validation are included in Tables S1 and S2 of the supplementary material, respectively. Figure 3 shows the comparison of observed and simulated streamflow over the calibration and validation periods for each basin. The simulated streamflow thus obtained was used as the reference for comparing the performance of the original and downscaled GCM-based simulations for the historic period (1990–2014). The calibrated model for each basin was used to simulate the future hydrological projections under the SSP5-8.5 scenario using original and downscaled GCM data for the years 2015–2100. We focused our analysis on the SSP5-8.5 scenario only to understand the anticipated extreme climate conditions in the future and their impacts on the hydrological responses.

Figure 2

Methodological framework adopted for the study.

Figure 3

Results of calibration and validation of HYMOD_DS using reference precipitation and temperature for (A) GRB, (B) SRB, (C) MRB, (D) BRB, and (E) PRB.

The comparison of the historic and future precipitation, temperature, and streamflow simulations is done on a seasonal scale. For the historic period (years 1990–2014), the monthly average data are grouped into four seasons—winter (December, January, February), spring (March, April, May), summer (June, July, August), and fall (September, October, November). Future projections are evaluated for mid-century (2041–2070) and end-century (2071–2,100) using the same seasonal grouping. The precipitation and streamflow simulations are compared based on the percentage differences: historic simulations are assessed against reference simulations, while future simulations are compared to the historic period simulations with the corresponding GCM data. Comparing the GCM historic data with reference data will help in understanding the bias in original GCMs, while the comparison of future data with historic data of GCM helps in analyzing the projected trends. For temperature, comparison was done based on absolute differences instead of percentage differences.

A similar comparison using percentage differences is also adopted for the streamflow components—snowmelt, ice melt, and rainfall-runoff and base flow (hereafter RR&B flow), and extreme streamflow. Note that rainfall-runoff mentioned hereafter refers to the rainfall-induced runoff. When evaluating changes in GCM-related simulations in the historic period, streamflow components are normalized with corresponding reference components (streamflow components from reference-based simulations). When evaluating future changes in streamflow components, GCM future simulations are normalized with GCM historic simulations (to evaluate relative change with respect to the climate signal captured in GCMs).

The impact of downscaling on the higher extreme streamflow values is evaluated using 95th percentile flow. A daily streamflow value simulated using GCMs is considered as a peak flow if it is greater than the 90th percentile flow of the reference-based simulations. The flows greater than the 95th percentile of these peaks are compared across historic and future periods.

2.3.2 Downscaling of GCM data

Downscaling, beyond simple bias correction of climate variables over HMA, is critical considering the challenges introduced due to the region’s complexity, diverse microclimate, and data-scarce environments. The four GCMs used in the study (see Table 1) are downscaled to a finer resolution (5 km) based on Pref and Tref using two statistical downscaling techniques: (a) mixed Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) matching and (b) Generalized Analog Regression Downscaling (GARD).

The CDF matching technique consists of pairing the coarse and reference pixels through a nearest-neighbor approach and using their statistical relationships to distribute the coarser information into a finer grid. A single CDF was built for the historic period for each pixel of both the high-resolution reference and the low-resolution GCM grid, and then matched using the nearest neighbor. In this technique, the statistical characterization of daily precipitation and mean temperature was done using a mixed-CDF concept. For precipitation, following the procedure from Emmanouil et al. (2021), extremes are represented by Generalized Pareto (GP) distribution and the remaining values by lognormal distribution. In the case of temperature, the lower and upper tails are represented by Generalized Pareto and the in-between values by Gaussian distribution (Nikolopoulos and de Alcantara Araujo, 2023). The identification of the lower and upper tails is performed by iteratively testing quantile thresholds (between 10th and 20th for lower and 80th and 95th for upper) and selecting the fit based on the lowest Anderson-Darling metric. The fitting of GP, Lognormal, and Gaussian distributions is performed by the Maximum Likelihood Estimation approach.

The GARD technique incorporates circulation predictors and generates gridded downscaled meteorological datasets with spatial and temporal variability features. The primary algorithm in this technique includes a logistic regression model to predict the probability of precipitation occurrence, an Ordinary Least Squares regression to predict precipitation and temperature magnitudes, and an analog selection process to develop both of those models for sets of climatologically related days (Gutmann et al., 2022). In this application, GARD used precipitation and 500 hPa zonal and meridional winds from the global climate models to predict precipitation at the surface, and it used temperature and winds to predict near-surface temperature. Because regression models have a tendency to produce overly smooth predictions, the spatio-temporally correlated stochastic sampling of the regression residuals was used as described in Gutmann et al. (2022). In addition to downscaling for climate applications, GARD has been applied for seasonal drought forecasting (Zamora et al., 2021) and real-time streamflow forecasting (Mendoza et al., 2017). Further details on the methodology and algorithm involved are available in Gutmann et al. (2022).

CDF matching is capable of simultaneously bias-correcting and downscaling lower-resolution climate data and is characterized by simplicity, versatility, and computational effectiveness, while its data requirements are relatively low, especially over complex terrains like HMA. On the other hand, GARD utilizes multiple large-scale predictors to predict local variables using historical analogs and regression. GARD captures physical relationships and combines analog realism and statistical power, making it more complex than CDF matching, which does not explicitly account for spatial/physical predictors. Comparison of these two downscaling methods, with their distinct differences, will allow us to evaluate their relative benefits as a function of algorithmic complexity.

2.3.3 Hydrological model

An empirical model—HYMOD_DS (Wi et al., 2015)—is used for simulating streamflow using the original and downscaled datasets discussed in Section 2.2. HYMOD_DS is a distributed hydrological model developed as a modification to the original HYMOD (Boyle, 2001) with additional modules for flow routing and snow/glacier processes. The model accepts gridded daily precipitation and temperature data as input for simulating streamflow. The entire basin is divided into different Hydrological Response Units (HRUs) based on the resolution of the climate forcing and elevation of the basin. The streamflow simulated in each of these HRUs is then routed toward the outlet to generate the total streamflow. In addition to precipitation and temperature inputs, the model requires datasets on elevation (digital elevation model derived from Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM)), land use/land cover (from GlobeLand30), and glacier thickness [from Farinotti et al. (2019)]. HYMOD_DS has been previously used for hydrological analysis over similar small basins and showed promising results (Nair et al., 2024; Wi et al., 2015). More details on the model structure and related specifics are available in Wi et al. (2015) and in the supplementary material (Section S1).

3 Results

3.1 Bias assessment in the reference period

3.1.1 Differences in precipitation

The comparison of the original and downscaled GCM-based precipitation over the historic period with Pref (Figure 4A) reveals an evident bias in the original GCM-based precipitation for most of the models. The extent of bias varies among models and basins considered. For instance, the basins in the western parts of HMA (GRB and SRB) exhibited an overestimation of original GCM-based precipitation across the models. In contrast, for the central basins (MRB and BRB) NoR-based original GCM showed a negative bias during winter, spring, and fall. In PRB, original GCM-based precipitation was overestimated over summer and fall, apart from MPI in fall. CMCC-based precipitation showed a particularly higher bias (more than 100%) over the summer and fall for the central and eastern basins.

Figure 4

Percentage difference in precipitation over different seasons of (A) historic period with respect to Pref which reveals the bias in original GCMs (B) mid-century period and (C) end-century period with respect to historic precipitation representing the future trends. Each row represents the basins considered in the study and each shaded column represents the four seasons—winter (blue shade), spring (green shade), summer (red shade), and fall (yellow shade). The blue lines represent the original GCMs, red lines—downscaled GCMs based on CDF matching, and yellow lines—downscaled GCMs based on GARD.

The results from Figure 4A further depict the critical role of downscaling in reducing the bias in original GCM-based precipitation with respect to Pref. For GRB winter precipitation, the bias in original GCMs was reduced from around 200% (MRI original) to less than 40%, with GARD-based downscaling performing better (1.3% for MRI). Similarly, both downscaling techniques perform well in reducing the bias for summer and fall precipitation. The overestimation of original MRI-based winter precipitation for SRB (115.8%) was reduced to 1.5% by CDF matching and to 14% by GARD. In the case of MRB, BRB, and PRB, the downscaling process was able to reduce the overestimation of summer and fall precipitations from original GCMs, which are the dominant precipitation seasons for the basins.

Even though the bias in precipitation was reduced considerably by the downscaling process, a few exceptions were observed across the models and basins. For GRB, original MRI-based summer precipitation has a positive bias whereas, after downscaling the bias has reversed to negative, with GARD-based precipitation underestimating more than CDF matching-based precipitation. The positive bias in MRI-based precipitation for MRB and BRB was observed to increase after downscaling over the winter and spring, in which the basins receive less precipitation. Similarly, for PRB, the bias in original MPI-based precipitation was reversed after downscaling over the non-dominant precipitation seasons.

3.1.2 Differences in temperature

The difference in Tref and GCM-based temperature is calculated in terms of absolute values instead of percentage differences to account for very high percentages obtained while comparing high and low temperatures. Figure 5A shows the difference in temperature from original and downscaled GCMs for each basin and the corresponding Tref over the historic period. As in the case of precipitation, the original GCM-based temperature showed significant bias compared to Tref, which is reduced considerably by the downscaling process.

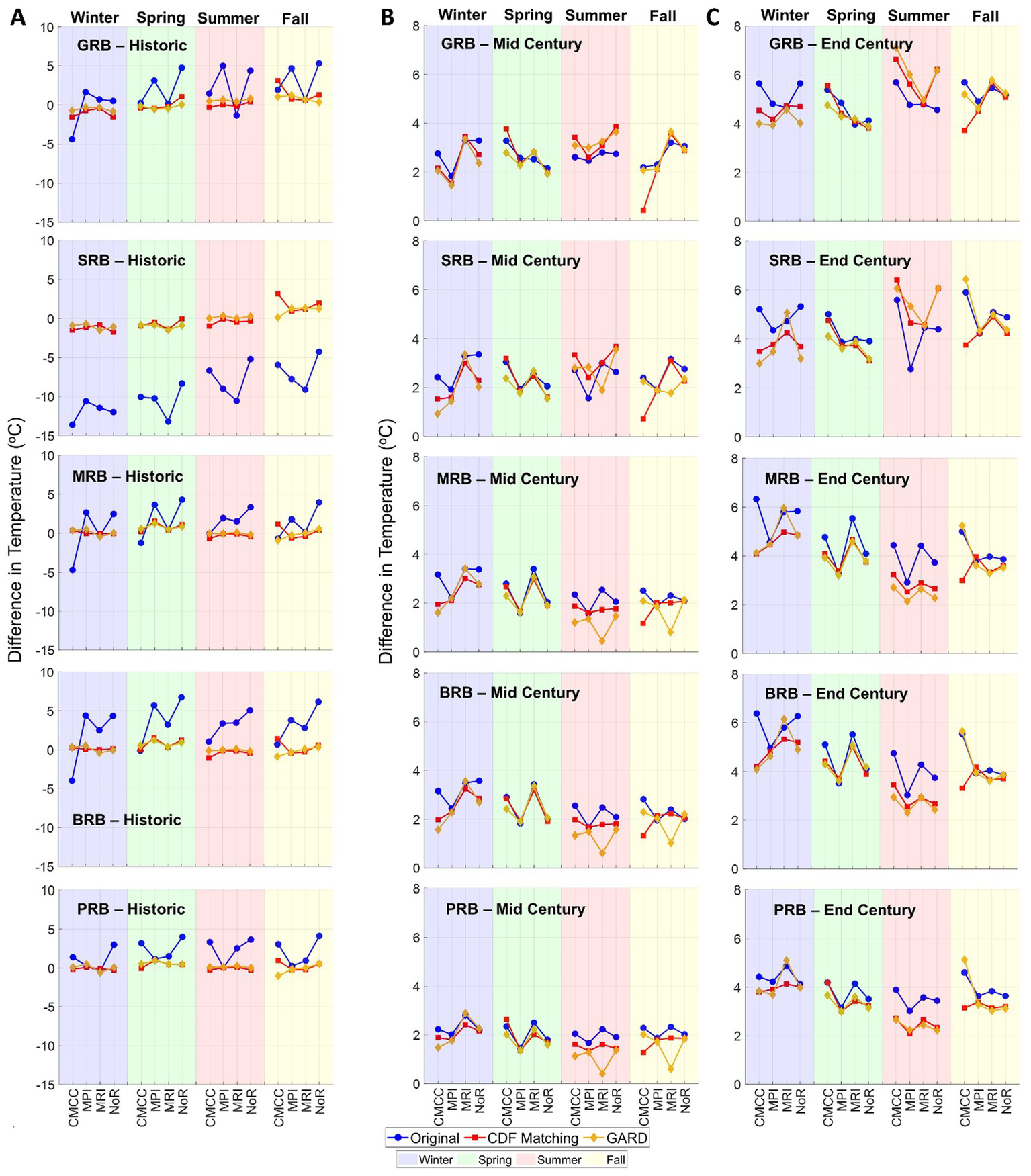

Figure 5

Difference in temperature over different seasons of (A) historic period with respect to Tref showing the bias in original GCMs (B) mid-century period and (C) end-century period with respect to historic temperature representing the future trends.

For GRB, the original CMCC-based winter temperature showed a negative bias compared to Tref (difference of −4.4 °C) while all other models showed a positive bias. MPI and NoR-based original GCMs exhibited a higher positive bias than other models over spring, summer, and fall seasons for GRB and winter and spring seasons for MRB and BRB. The temperature from original GCMs for SRB showed a significant underestimation compared to Tref (−13.6 °C for CMCC-based winter temperature to −4.3 °C for NoR-based fall temperature). Both downscaling methods significantly reduced the cold bias in the original GCMs. The temperature for MRB and BRB showed a similar pattern with CMCC-based winter temperature showing an underestimation compared to Tref (−4.7 °C for MRB and -4 °C for BRB). The GCM-based winter temperature for PRB was found to be similar to Tref except for CMCC and NoR which showed a positive bias (1.4 °C for CMCC and 3 °C for NoR).

3.2 Effects of downscaling on future climate projections

3.2.1 Differences in precipitation over future period

In Figures 4B,C we show the percentage difference in precipitation from the original and downscaled products over the mid-century and end-century, respectively, with respect to the corresponding historic precipitation. For instance, CMCC winter precipitation over the mid-century is compared with the winter precipitation from CMCC over the historic period, and likewise for all other models. Figures 4B,C represent the future trend in precipitation from the original and downscaled GCMs compared to their corresponding historic values. The original and downscaled precipitation from each model across the basins were observed to have similar percentage differences, which indicates that the trends in original GCMs are well preserved after the downscaling process. An exception was observed for CMCC-based winter precipitation following an opposite trend compared to other models across the basins over the mid-century period. This opposite trend of CMCC is also observed for summer precipitation over GRB and SRB, where all other models have a negative trend, CMCC precipitation increases.

The winter and spring precipitation for GRB and SRB was observed to increase towards the end century, whereas for MRB, BRB, and PRB, an increase in summer and fall precipitation is expected. This indicates that in the future, an increase in precipitation over the dominant seasons will be anticipated in the basins considered. The opposite trend of CMCC observed in all basins over the mid-century remains for MRB and BRB over the end century. For GRB and SRB, the downscaled winter and spring precipitation from MRI has a higher increase than the corresponding original MRI-based precipitation. On the other hand, GARD-based winter precipitation from MPI and MRI for the central and eastern basins has a significant negative trend compared to CDF matching-based precipitation.

3.2.2 Differences in temperature over future period

Figures 5B,C show the difference in temperatures from original and downscaled GCMs over mid-century and end-century, respectively, with respect to the corresponding historic period. The temperature was found to increase across all the basins and models in the future. As seen in the case of precipitation, the trends in temperature from the original GCMs were preserved even after the downscaling process. The increase in temperature for GRB towards the end of the century was observed to be approximately double that of mid-century (increased by 4.6 °C, 4.4 °C, 5.6 °C, and 5 °C over winter, spring, summer, and fall seasons, respectively). For SRB, the average temperature difference of 2.3 °C over winter, spring, and fall seasons in mid-century increased to 4 °C over the end-century, while the summer temperature difference increased from 2.9 °C to 5.1 °C. For the basins in central and eastern HMA, the projected difference in temperature was higher for the winter season and less for summer over both mid and end centuries. The average difference in MRB winter temperature is expected to be 2.7 °C over mid-century to 5 °C by the end of the century, whereas the difference is 1.8 °C over the mid-century and 3 °C over the end century for summer. BRB, being geographically close to MRB, was observed to have similar temperature differences as MRB. For PRB, the difference in winter temperature increases from 2.2 °C (mid-century) to 4.1 °C (end-century), whereas the average summer temperature difference increases from 1.6 °C (mid-century) to 2.8 °C (end-century).

While in general the temperatures were found to increase for both original and downscaled products, there were a few exceptions. For instance, fall temperature from CMCC downscaled using CDF matching increased only by 0.4 °C over the mid-century while the original and GARD-based downscaled temperatures increased by 2.2 °C and 2 °C, respectively. Similarly for SRB, CDF matching-based CMCC temperature increased by 0.7 °C over the mid-century, while original and GARD-based CMCC showed an increase of 2.4 °C and 2 °C, respectively. Also, the magnitude of the increase in temperature within a season across different models varies significantly. For instance, CMCC and MPI-based temperatures showed comparatively less increase than MRI and NoR, especially for winter temperatures.

3.3 Effects of downscaling on hydrological projections

3.3.1 Differences in streamflow over historic period

In this section we investigate how the identified differences in precipitation and temperature discussed previously, manifest as changes in streamflow. The percentage difference in simulated streamflow over the historic period with respect to reference-based simulations (see Figure 6A) is influenced by both precipitation and temperature. For instance, in GRB, winter streamflow from original GCMs exhibits a positive bias as that of precipitation, while the downscaled-based streamflow simulations show a negative bias as in temperature. The spring streamflow shows a significantly high positive bias similar to that of precipitation. The very low temperature from the original GCMs for SRB has reflected on the streamflow simulations across the seasons, except for the spring season. The original MRI-based streamflow over spring follows a pattern similar to that of temperature, while CDF matching-based streamflow simulations over the spring exhibit a higher positive bias compared to reference-based simulations even though the bias in precipitation and temperature are relatively low.

Figure 6

Percentage difference in simulated streamflow over different seasons of (A) historic period with respect to reference-based streamflow simulations (B) mid-century period and (C) end-century period with respect to historic simulations. The percentage difference for the original GCM-based spring streamflow over historic period for GRB went up to 695% due to very low reference streamflow and the original GCM-based spring streamflow for SRB over the future went up to 916% due to very low historic streamflow. Hence the y-axis was limited to 250% to make the remaining plots visible.

While the streamflow simulations from the basins in the western parts of HMA exhibited patterns influenced by both precipitation and temperature, the simulations over MRB, BRB, and PRB being rainfall-dominated basins, are influenced more by precipitation than by temperature (see Figures 4A, 6A). The patterns of streamflow in these basins, especially over the summer and fall seasons, follow a pattern similar to that of corresponding precipitation.

3.3.2 Differences in streamflow over future period

Figures 6B,C show the percentage difference in simulated streamflow obtained using original and downscaled GCMs as input to HYMOD_DS over mid and end centuries respectively, with respect to the corresponding historical simulations. For GRB, the streamflow simulations over the winter and spring seasons during the mid-century increased with respect to corresponding historical simulations, whereas summer and fall streamflow decreased. The streamflow simulated using downscaled GCMs over the spring season was found to be overestimated compared to the original GCMs. The simulated streamflow for SRB increased for all seasons across all GCMs, except for the fall season where a decrease in streamflow was observed for downscaled CMCC and MPI-based simulations. For the basins in Nepal and Bhutan, winter, spring, and summer streamflow simulated using all GCMs did not change significantly compared to the corresponding historical simulations, except for CMCC-based simulations which showed an increase. The streamflow over the fall season for MRB and BRB increased during the mid-century compared to the historic simulations, while that of PRB did not change significantly except for CMCC.

The streamflow simulations over the end century were observed to increase considerably over all the basins compared to the mid-century. For GRB, the streamflow simulations were found to increase over the winter and spring seasons, while a decrease in streamflow was observed for the summer and fall seasons. GRB being a snow-fed basin, this increase in winter and spring streamflow as a result of the increase in precipitation and temperature indicates early and rapid snow melt. For SRB, streamflow increased significantly for all seasons, with the rate of increase higher for the winter and spring seasons. The high values for the percentage increase over the spring season for GRB and that of all seasons for SRB are also attributed to the very low streamflow values in their corresponding historic periods. The basins in central and eastern parts of HMA also showed an increase in streamflow for all seasons, however, the rate of increase in streamflow for PRB was found to be lower compared to MRB and BRB. In these basins, the streamflow is expected to increase more in the fall and winter seasons.

The comparison of runoff ratio based on annual rainfall-runoff and precipitation across the study basins (Figure S1) indicates a much lower ratio over western basins than central and eastern basins. The higher runoff ratio over central and eastern basins can be attributed to the dominance of rainfall rather than snowfall over these basins. The cold bias in glacier-dominated SRB based on the original GCMs was observed to be translated to a lower runoff ratio, owing to the precipitation phase transition from rainfall to snowfall.

3.3.3 Annual streamflow and its components

The comparison of projections of annual simulated streamflow and its components based on downscaled GCMs indicates promising performance by both downscaling techniques (Figures S2–S5 in the supplementary material). The simulations based on downscaled data were found to be close to reference-based simulations over the historic period. The future projections of streamflow over GRB are anticipated to be similar to the historic period, while that of all other basins increases significantly towards the end of the century. The snowmelt projections based on both downscaling techniques are expected to be the same over the central and eastern basins. A small positive bias was observed for projections of streamflow and components based on CDF matching compared to GARD-based projections, owing to the intrinsic differences between the two techniques.

3.3.4 Relative contribution of streamflow components

The impact of downscaling on the contribution of streamflow components (snowmelt, ice melt, and rainfall-runoff and base flow) was analyzed by first comparing the streamflow components obtained by running HYMOD_DS using different model inputs (original and downscaled) for the historic period with the reference-based simulations. The streamflow components for the historic period are normalized using the corresponding reference-based components and compared in Figure 7A. A value of 1 in Figure 7A indicates the streamflow component simulated using the original or downscaled GCM over the historic period is close to the reference component.

Figure 7

Contribution of streamflow components over (A) historic period normalized based on reference-based streamflow components (B) mid-century period and (C) end-century period normalized based on historic streamflow components. The shaded column represents the three components of streamflow—snowmelt (blue shade), ice melt (green shade), RR&B flow (red shade).

The results indicate that in most cases original GCM-based streamflow components are significantly biased. For instance, in GRB, snowmelt and RR&B flow obtained from the original GCM have a positive bias compared to the reference, with RR&B flow being three times more. For SRB, the contribution of original GCM-based components is very low compared to the reference, especially for ice melt, owing to the very low temperature for the basin (see Figure 5A). For MRB and BRB, the components simulated using original and downscaled GCMs are close to the reference-based components with an exception for BRB RR&B flow component from all models and CMCC-based snowmelt where the original GCM has a slight overestimation compared to downscaled-based components. In the case of PRB, a significant overestimation (two to five times) is observed for the ice melt component based on original GCMs. Also, the original CMCC-based RR&B flow has a positive bias whereas the downscaled components are similar to the reference-based components.

In Figures 7B,C, we show the contribution of streamflow components simulated using original and downscaled GCMs normalized based on the corresponding historic components over the mid-century and end-century, respectively. Snowmelt and ice melt components for GRB do not change significantly over the mid-century compared to the historic period, while the RR&B flow component increases. RR&B flow obtained by using GARD-based CMCC was observed to be two times more than the corresponding historic component. The normalized ice melt component from the original GCMs for SRB resulted in a higher value due to the very low historic components. For SRB, all the streamflow components were found to increase over the mid-century compared to the historic period. For the basins in Nepal and Bhutan, ice melt and RR&B flow increased over the mid-century while the snowmelt component was found to decrease compared to the historic period. An exception was observed in MRB for the original CMCC-based snowmelt component, which increased two times over mid-century compared to historic.

The RR&B flow component for GRB was found to increase towards the end century, while the snowmelt and ice melt did not change compared to the mid-century. For SRB, all streamflow components increased for the original as well as downscaled GCMs, with the increase in original GCMs being more. For MRB, BRB, and PRB, the snowmelt component decreased further toward the end century while ice melt and RR&B flow increased compared to the historic period. This might be attributed to the increase in temperature towards the end-century, which results in precipitation phase transition (more rainfall rather than snowfall) and an increased ice melt. However, for PRB, the rate of increase in ice melt and RR&B flow is low compared to MRB and BRB.

3.3.5 Peak streamflow

The impact of downscaling on the higher peak flows was analyzed by first comparing the 95th percentile peak flow over the historic period with that of the reference period (Figure 8A). The percentage difference in the 95th percentile peak flow simulated using original GCMs for GRB was found to have a positive bias compared to the corresponding downscaled flows, especially for MRI. For NoR-based peak flows, CDF matching had a positive bias than the original and GARD-based flows. For SRB, an underestimation of peak flows was observed across the GCMs, except for peak flows from CDF matching-based CMCC and NoR. For the basins in Nepal and Bhutan, a positive bias in peak flows was observed with an exception for GARD-based flows from CMCC (for MRB) and MPI. For MRB, peak flows from original as well as downscaled MPI exhibited underestimation compared to other GCMs.

Figure 8

Percentage difference in 95th percentile peak flow over (A) historic period with respect to reference-based peak flow (B) mid-century period and (C) end-century period with respect to historic peak flow.

Figures 8B,C show the percentage difference in 95th percentile peak flow over the mid and end centuries, respectively, with respect to corresponding historical peak flows. A reduction in peak flows was observed for GRB over the mid-century compared to historical peak flows across GCMs except for original and GARD-based flows from NoR. In all other basins, peak flow is expected to increase in the mid-century. The peak flows obtained based on the original MPI resulted in lower values compared to the corresponding peak flows from downscaled forcing, across all the basins. For SRB, the original GCM-based peak flows had higher values than the downscaled-based flows. Downscaled MRI based on CDF matching exhibited a negative difference compared to the original and GARD-based peak flows. MPI and MRI-based peak flows for MRB were found to be similar to historic peaks whereas CMCC and NoR-based peaks had a positive bias, with the original CMCC-based flow having a percentage difference of 75%. For BRB CDF matching-based peak flow shows an overestimation across all GCMs compared to original and GARD-based flows, except for CMCC. In PRB, MRI-based peak flows had a significant positive bias (58–82%) than the corresponding historic peak flows, while NoR-based flows showed a very low increase (approximately 0–10%). For the end century, the percentage difference in peak flows further increased for all basins, except for PRB where a decrease in peak was observed for MRI-based flows.

3.4 Elevation dependency of climate and streamflow projections

In order to understand how projected changes in climate and streamflow will manifest along the steep gradients of the region’s terrain, the elevation profiles for annual precipitation, temperature, and streamflow were made. The profiles are created using the ensemble mean of the four GCMs used in the study. The profile of annual precipitation over different elevation zones based on original GCMs shows a considerably different pattern than that of downscaled GCMs (Figure S6). The bias in original GCMs is more evident over the western and eastern basins of HMA. For PRB, the bias in precipitation based on the original GCM is more over areas above 2000 m compared to lower elevations. The mean temperature shows a decreasing profile with altitude (Figure S7). The cold bias observed in the original GCM over SRB tends to increase further above an elevation of 5,000 m. The elevation-dependent annual streamflow profile based on original and downscaled GCMs (Figure 9) indicates a significant overestimation by the original GCM, especially over elevations below 4,000 m for western basins. In GRB, the regions above 5,000 m are anticipated to experience a higher increase in streamflow towards the end century.

Figure 9

Elevation-dependent annual streamflow profile based on GCM ensemble mean over (A) historic, (B) mid-century, and (C) end-century periods.

4 Discussion

4.1 Precipitation and temperature

The analysis of precipitation and temperature from original and downscaled GCMs revealed a significant bias in the original GCMs, the extent of which varies based on the GCM and the basin considered. For instance, original CMCC-based precipitation over summer and fall for the basins in central (MRB and BRB) and eastern HMA (PRB) exhibited a higher positive bias compared to the reference precipitation than other GCMs during the historic period. For the basins in western HMA (GRB and SRB), the original GCMs showed a higher positive bias for spring precipitation. Winter precipitation was also overestimated in the case of GRB. The wet bias in precipitation from original GCMs is observed in the mid-century and end-century periods as well across the basins. The higher bias in historic precipitation from the original GCMs resulted in a bigger change in precipitation over the mid and end centuries. The overall wet bias in precipitation simulated by CMIP6 GCMs, especially in higher altitude regions, has been previously reported (Cui et al., 2021; Dong and Dong, 2021; Zhu and Yang, 2020).

The relative difference in temperature also showed a strong dependence on geographical characteristics. In the case of SRB, all four GCMs significantly underestimated the temperature across the seasons. Many previous studies identified a cold bias in GCMs over high-elevation regions, especially for winter temperatures. Lalande et al. (2021) compared the temperature simulated by 26 GCMs with the Climate Research Unit (CRU) observational dataset over the HMA region and observed a significant cold bias (in the range of −8.2 °C to 2.9 °C) for most of the models. However, in our study, the cold bias was observed for all seasons over SRB only, which has a glacier cover of about 40% of the total area. The temperature across all basins and all models was found to increase over the future, with a higher rate of increase towards the end-century than mid-century.

While the relative difference in future temperature with respect to the corresponding GCM historic temperature exhibited a consistent increase across all models and seasons, future precipitation showed variable trends depending on the choice of GCM. A reverse trend was observed in CMCC-based winter precipitation across all basins, consistent for both original and downscaled products, especially over the mid-century. The results of the relative difference in the future climate with respect to the corresponding GCM historic climate from the original and downscaled data revealed that the choice of GCM has more pronounced effects on the direction and magnitude of future climate than the downscaling method. There were similarities in the trends of percentage difference values between the original and downscaled future climate across the basins, which implies that if the original GCMs are used as such for trend analysis, despite the bias, they still capture the magnitude of relative change in the future. However, the absolute magnitudes were higher for the original GCMs than the corresponding downscaled data, thereby resulting in biased hydrological responses which raise caution for directly utilizing original GCM estimates for future climate impact analysis and water resources assessment.

4.2 Downscaling method

Both CDF matching and GARD downscaling methods have shown promising performance in reducing the bias in original GCMs, the extent of which varied across the basins, models, and seasons. For instance, GARD performed well in reducing the bias over all the seasons for GRB, except for summer where the GARD-based precipitation was significantly underestimated across all models (percentage difference ranging from −61% to −72%). On the other hand, CDF matching showed notable improvement in summer precipitation for the basins in central and eastern HMA. It is worth noting that the CDF fitting in the case of CDF matching was done over the entire historic period and not on a seasonal scale. Nevertheless, CDF matching shows promising results in improving the bias, especially over the dominant season for precipitation. In a few cases, the downscaled products exhibited higher bias compared to the original GCMs. The downscaled summer precipitation for GRB exhibited additional negative bias across all models, with GARD-based products having higher bias than CDF matching. However, the impact of this negative bias on the hydrologic response will be negligible since it is observed over a season in which the basin receives less precipitation. The bias in temperature was also reduced significantly across all the basins and seasons, with a few exceptions. These results suggest that while the downscaled products reduce the bias in the original GCMs, they should be used and interpreted with caution.

4.3 Streamflow components

The changes in precipitation and temperature were found to have a direct impact on the streamflow simulations across the basins. The total streamflow simulations from rainfall-dominated basins in central and eastern HMA showed a stronger correlation with precipitation than temperature, whereas both precipitation and temperature influenced the streamflow simulations over western basins. The original GCM-based streamflow simulations across the seasons over SRB for the historic period had an underestimation owing to the cold bias, except for spring.

The contribution of the snowmelt component for SRB is expected to increase considerably over the future. As demonstrated also by Wang et al. (2024), Duan et al. (2022), and Chen et al. (2015), a rapid increase in future temperature will result in earlier melting of snow which leads to an increase in snowmelt floods, especially in snowfall-dominated basins. However, in our study snowmelt and ice melt components for GRB remained mostly the same over the future compared to the historic period. For MRB and BRB, RR&Bflow and ice melt increased towards the future resulting in higher streamflow dominated by rainfall-runoff. At the same time, snowmelt was found to decrease over the central and eastern basins for all GCMs compared to the corresponding historic-based simulations.

4.4 Peak flow projections

The analysis of the higher peak flow quantiles showed a positive bias in the GCM-based simulations compared to the reference-based peaks across the basins, except for SRB. The future peak flows based on downscaled GCMs resulted in higher values relative to the corresponding original GCMs, especially for rainfall-dominated basins. Comparing the results from Figures 7, 8, these higher values of peak flows in the future are attributed to the increase in rainfall-runoff and ice melt components of streamflow. The peak flows are expected to increase towards the end of the century bringing more intense flooding in the region, especially over the central and eastern HMA. These results are in line with the findings of Shrestha et al. (2023) which highlighted the increase in high-flow events in eastern Nepal due to a projected increase in precipitation extremes thus projecting more frequent floods and landslides.

4.5 Implications of downscaled hydrological projections

Downscaled hydrological projections are critical in predicting when and how much meltwater will be available, guiding irrigation scheduling, storage policies, and domestic water allocations. They act as a bridge between coarse-scale climate variables and watershed-based decisions on water storage, hydropower plant installation, and flood risk management by providing reasonable estimates of future inflows. Downscaled projections will provide more realistic insights into the water resource availability, thereby facilitating better strategies for irrigation planning and drinking water supply. The variation in future streamflow, especially over snow and glacier-fed basins, will alter the power generation potential of hydropower plants. Correction of biases from original GCMs using downscaling methods helps in preventing under- or overestimation of streamflow inputs, thus improving the efficiency of reservoirs and hydropower plants. Improved projection of peak flow estimates will facilitate planning of flood mitigation measures and avoid under- or overdesign costly flood defense systems. Overall, by incorporating downscaled hydrologic projections into decision-making, better climate resilience and sustainability may be ensured in glacierized basins of HMA.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we investigate the importance of climate downscaling on future hydrologic projections of glacierized catchments in HMA. We examined different aspects of future streamflow response, due to different climate forcings, related to (a) total streamflow (indicating water resources availability), (b) contributions from various streamflow components (pertaining to changes in basin’s hydrological processes) and (c) peak flows, indicating potential changes in future flood risk. The major findings from this study can be broadly classified into the following:

-

(1) Impacts of choice of climate model and downscaling technique

-

The representation of catchment climatology was found to vary considerably with the choice of GCM, particularly for precipitation. For instance, CMCC-based simulations showed consistent wet bias in rainfall-dominated catchments.

-

Despite distinct methodological differences, both downscaling methods reduced GCM biases.

-

The choice of GCM was found to have more pronounced effects on the direction and magnitude of future climate than the downscaling method.

-

Uncertainties introduced by both downscaling methods were found to be less for temperature than for precipitation.

-

Downscaled temperatures generally reproduced observed climatology well, particularly in central and eastern HMA. However, a reversal of fall temperature trends after downscaling was noted in the glacier-dominated SRB, highlighting the need for further investigation into GCM temperature representation in highly glacierized regions.

-

(2) Impacts of downscaling on the hydrological projections of glacierized catchments in HMA

-

The total streamflow simulated from a basin is highly influenced by the precipitation and temperature patterns, the extent of which depends on whether the basin is rainfall-dominated or snowfall-dominated.

-

The water availability in the basins, in terms of streamflow, is expected to increase towards the end of the century with the corresponding increase in the rainfall-runoff component, especially over higher elevations. Even though the increase in water availability (in terms of total streamflow) is observed for both original and downscaled-based results, the downscaled-based results reveal a reasonable increase compared to that of original GCMs.

-

The increase in future peak flows suggests the occurrence of more intense snowmelt floods in the western and rainfall-runoff floods in the central and eastern HMA.

-

Without downscaling, GCM biases lead to overestimated peak flows, particularly in glacier-dominated SRB, implying unrealistically frequent and severe floods. Such errors could misguide flood risk management, infrastructure design, and adaptation planning.

Even though we attempted to choose five basins with distinct climatology spread across the HMA, the inclusion of basins located further north of HMA is difficult due to lack of streamflow observations needed to calibrate/validate our hydrological model. In future analysis, an effort should be made to include more basins from areas in central, north, and northwest HMA. Utilization of only two downscaling techniques and four GCMs may not fully represent the entire spectrum of results that one can obtain from the various downscaling techniques and GCMs available. However, we believe that our results provide clear evidence on the significance of downscaled climate data for hydrologic projections in this region. While the inclusion of more GCMs and additional downscaling methods can benefit such an investigation, it is important to highlight that these methods and GCMs were the only ones available at the time from the NASA High Mountain Asia database.

Our goal through this study is to demonstrate and quantify the importance of downscaling coarse GCMs to be able to use them for hydrological applications in complex terrains like HMA. The findings from this study will serve as a piece of reference information for climate scientists and local stakeholders while utilizing these climate models for regional analyses.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

AN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DA: Resources, Writing – review & editing. EG: Resources, Writing – review & editing. SW: Resources, Writing – review & editing. JP: Resources, Writing – review & editing. KT: Resources, Writing – review & editing. MH: Resources, Writing – review & editing. RK: Resources, Writing – review & editing. EN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research is supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration High Mountain Asia Program (grant #80NSSC20K1300).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the high-resolution reference precipitation and temperature datasets obtained from Sujay Kumar’s and Viviana Maggioni’s team of NASA HiMAT, respectively. Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) Pakistan is acknowledged for providing the observed streamflow data for Gilgit and Shigar River Basins.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

1

Adnan M. Liu S. Saifullah M. Iqbal M. Saddique Q. Ul Hussan W. et al . (2024). Estimation of changes in runoff and its sources in response to future climate change in a critical zone of the Karakoram mountainous region, Pakistan in the near and far future. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk15:2291330. doi: 10.1080/19475705.2023.2291330

2

Ali K. Bajracharya R. M. Sitaula B. K. Raut N. Koirala H. L. (2017). Morphometric analysis of Gilgit River basin in mountainous region of Gilgit-Baltistan province, northern Pakistan. J. Geoscience Environ. Prot.5:7. doi: 10.4236/gep.2017.57008

3

Alizadeh O. (2022). Advances and challenges in climate modeling. Clim. Chang.170:18. doi: 10.1007/s10584-021-03298-4

4

Boyle D. P. 2001 Multicriteria calibration of hydrologic models. Department of Hydrology and Water Resources Engineering, the University of Arizona.

5

Bozkurt D. Rojas M. Boisier J. P. Rondanelli R. Garreaud R. Gallardo L. (2019). Dynamical downscaling over the complex terrain of Southwest South America: present climate conditions and added value analysis. Clim. Dyn.53, 6745–6767. doi: 10.1007/s00382-019-04959-y

6

Budhigandaki Hydroelectric Project Development Committee (BHPDC) (2015). Feasibility study and detailed design of Budhi Gandaki HPP Phase 3: draft detailed design report. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

7

Buser C. M. Künsch H. R. Weber A. (2010). Biases and uncertainty in climate projections. Scand. J. Stat.37, 179–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9469.2009.00686.x

8

Chen H. Xu C.-Y. Guo S. (2012). Comparison and evaluation of multiple GCMs, statistical downscaling and hydrological models in the study of climate change impacts on runoff. J. Hydrol.434-435, 36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.02.040

9

Chen D. Xu B. Yao T. Guo Z. Cui P. Chen F. et al . (2015). Assessment of past, present and future environmental changes on the Tibetan plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull.60, 3025–3035. doi: 10.1360/N972014-01370

10

Cherchi A. Fogli P. G. Lovato T. Peano D. Iovino D. Gualdi S. et al . (2019). Global mean climate and main patterns of variability in the CMCC-CM2 coupled model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst.11, 185–209. doi: 10.1029/2018MS001369

11

Cui T. Li C. Tian F. (2021). Evaluation of temperature and precipitation simulations in CMIP6 models over the Tibetan plateau. Earth Space Sci.8:e2020EA001620. doi: 10.1029/2020EA001620

12

Devkota R. P. Pandey V. P. Bhattarai U. Shrestha H. Adhikari S. Dulal K. N. (2017). Climate change and adaptation strategies in Budhi Gandaki River basin, Nepal: a perception-based analysis. Clim. Chang.140, 195–208. doi: 10.1007/s10584-016-1836-5

13

Di Virgilio G. Ji F. Tam E. Nishant N. Evans J. P. Thomas C. et al . (2022). Selecting CMIP6 GCMs for CORDEX dynamical downscaling: model performance, independence, and climate change signals. Earths Future10:e2021EF002625. doi: 10.1029/2021EF002625

14

Dollan I. J. Maina F. Z. Kumar S. V. Nikolopoulos E. I. Maggioni V. (2024). An assessment of gridded precipitation products over High Mountain Asia. J. Hydrol. Regn. Stud.52:101675. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.101675

15

Dong T. Dong W. (2021). Evaluation of extreme precipitation over Asia in CMIP6 models. Clim. Dyn.57, 1751–1769. doi: 10.1007/s00382-021-05773-1

16

Duan K. Yao T. Wang N. Shi P. Meng Y. (2022). Changes in equilibrium-line altitude and implications for glacier evolution in the Asian high mountains in the 21st century. Sci. China Earth Sci.65, 1308–1316. doi: 10.1007/s11430-021-9923-6

17

El-Samra R. Bou-Zeid E. El-Fadel M. (2018). To what extent does high-resolution dynamical downscaling improve the representation of climatic extremes over an orographically complex terrain?Theor. Appl. Climatol.134, 265–282. doi: 10.1007/s00704-017-2273-8

18

Emmanouil S. Langousis A. Nikolopoulos E. I. Anagnostou E. N. (2021). An ERA-5 derived CONUS-wide high-resolution precipitation dataset based on a refined parametric statistical downscaling framework. Water Resour. Res.57:e2020WR029548. doi: 10.1029/2020WR029548

19

Emmanouil S. Langousis A. Nikolopoulos E. I. Anagnostou E. N. (2023). Exploring the future of rainfall extremes over CONUS: the effects of high emission climate change trajectories on the intensity and frequency of rare precipitation events. Earths Future11:e2022EF003039. doi: 10.1029/2022EF003039

20

Faiz M. A. Liu D. Fu Q. Li M. Baig F. Tahir A. A. et al . (2018). Performance evaluation of hydrological models using ensemble of general circulation models in the northeastern China. J. Hydrol.565, 599–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.08.057

21

Farinotti D. Huss M. Fürst J. J. Landmann J. Machguth H. Maussion F. et al . (2019). A consensus estimate for the ice thickness distribution of all glaciers on earth. Nat. Geosci.12, 168–173. doi: 10.1038/s41561-019-0300-3

22

Gebrechorkos S. H. Hülsmann S. Bernhofer C. (2019). Regional climate projections for impact assessment studies in East Africa. Environ. Res. Lett.14:044031. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab055a

23

Gutmann E. D. Hamman J. J. Clark M. P. Eidhammer T. Wood A. W. Arnold J. R. (2022). En-GARD: a statistical downscaling framework to produce and test large ensembles of climate projections. J. Hydrometeorol.23, 1545–1561. doi: 10.1175/JHM-D-21-0142.1

24

Gutmann E. D. Rasmussen R. M. Liu C. Ikeda K. Gochis D. J. Clark M. P. et al . (2012). A comparison of statistical and dynamical downscaling of winter precipitation over complex terrain. J. Clim.25, 262–281. doi: 10.1175/2011JCLI4109.1

25

Hock R. Rasul G. Adler C. Caceres B. Gruber S. Hirabayashi Y. et al . (2019). Chapter 2: high Mountain areas—special report on the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/chapter-2/ (Accessed May 28, 2024).

26

Hugonnet R. McNabb R. Berthier E. Menounos B. Nuth C. Girod L. et al . (2021). Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century. Nature592, 726–731. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03436-z

27

Hussain A. (2020). The “water tower of Asia” and the Gilgit River basin. PAMIR TIMES. Available online at: https://pamirtimes.net/2020/11/21/the-water-tower-of-asia-and-the-gilgit-river-basin/ (Accessed March 13, 2024).

28

IPCC . (2013). What is a GCM? Available online at: https://www.ipcc-data.org/guidelines/pages/gcm_guide.html (Accessed May 13, 2024).

29

Kayastha R. B. Kayastha R. (2020). “Glacio-hydrological degree-day model (GDM) useful for the Himalayan River basins” in Himalayan weather and climate and their impact on the environment. eds. DimriA. P.BookhagenB.StoffelM.YasunariT. (Berlin: Springer International Publishing), 379–398.

30

Khadka D. Pathak D. (2016). Climate change projection for the Marsyangdi River basin, Nepal using statistical downscaling of GCM and its implications in geodisasters. Geoenviron. Disasters3:15. doi: 10.1186/s40677-016-0050-0

31

Kim S. Kim B. S. Jun H. Kim H. S. (2014). Assessment of future water resources and water scarcity considering the factors of climate change and social–environmental change in Han River basin, Korea. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess.28, 1999–2014. doi: 10.1007/s00477-014-0924-1

32

Lalande M. Ménégoz M. Krinner G. Naegeli K. Wunderle S. (2021). Climate change in the High Mountain Asia in CMIP6. Earth Syst. Dyn.12, 1061–1098. doi: 10.5194/esd-12-1061-2021

33

Latif Y. Ma Y. Ma W. (2021). Climatic trends variability and concerning flow regime of upper Indus Basin, Jehlum, and Kabul river basins Pakistan. Theor. Appl. Climatol.144, 447–468. doi: 10.1007/s00704-021-03529-9

34

Latif Y. Ma Y. Ma W. Muhammad S. Adnan M. Yaseen M. et al . (2020). Differentiating snow and glacier melt contribution to runoff in the Gilgit River basin via degree-day modelling approach. Atmos11:1023. doi: 10.3390/atmos11101023

35

Lovato T. Peano D. Butenschön M. Materia S. Iovino D. Scoccimarro E. et al . (2022). CMIP6 simulations with the CMCC earth system model (CMCC-ESM2). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst.14:e2021MS002814. doi: 10.1029/2021MS002814

36

Maina F. Z. Kumar S. V. Dollan I. J. Maggioni V. (2022). Development and evaluation of ensemble consensus precipitation estimates over High Mountain Asia. J. Hydrometeorol.23, 1469–1486. doi: 10.1175/JHM-D-21-0196.1

37

Mannan Afzal M. Wang X. Sun L. Jiang T. Kong Q. Luo Y. (2023). Hydrological and dynamical response of glaciers to climate change based on their dimensions in the Hunza Basin, Karakoram. J. Hydrol.617:128948. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128948

38

Mendoza P. A. Wood A. W. Clark E. Rothwell E. Clark M. P. Nijssen B. et al . (2017). An intercomparison of approaches for improving operational seasonal streamflow forecasts. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci.21, 3915–3935. doi: 10.5194/hess-21-3915-2017

39

Michalek A. Quintero F. Villarini G. Krajewski W. F. (2023). Projected changes in annual maximum discharge for Iowa communities. J. Hydrol.625:129957. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129957

40

Mudbhari D. Kansal M. L. Kalura P. (2022). Impact of climate change on water availability in Marsyangdi river basin, Nepal. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc.148, 1407–1423. doi: 10.1002/qj.4267

41

Müller W. A. Jungclaus J. H. Mauritsen T. Baehr J. Bittner M. Budich R. et al . (2018). A higher-resolution version of the max Planck institute earth system model (MPI-ESM1.2-HR). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst.10, 1383–1413. doi: 10.1029/2017MS001217

42

Nair A. V. Wi S. Kayastha R. B. Gleason C. Dollan I. Maggioni V. et al . (2024). On the challenges of simulating streamflow in glacierized catchments of the Himalayas using satellite and reanalysis forcing data. J. Hydrometeorol.25, 847–866. doi: 10.1175/JHM-D-23-0048.1

43

Nikolopoulos E. de Alcantara Araujo D. (2023). High Mountain Asia daily 5 km downscaled SPEAR precipitation and air temperature projections, version 1 [dataset]. Boulder, Colorado, USA: NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center.

44

Rounce D. R. Hock R. Maussion F. Hugonnet R. Kochtitzky W. Huss M. et al . (2023). Global glacier change in the 21st century: every increase in temperature matters. Science379, 78–83. doi: 10.1126/science.abo1324

45

Seland Ø. Bentsen M. Olivié D. Toniazzo T. Gjermundsen A. Graff L. S. et al . (2020). Overview of the Norwegian earth system model (NorESM2) and key climate response of CMIP6 DECK, historical, and scenario simulations. Geosci. Model Dev.13, 6165–6200. doi: 10.5194/gmd-13-6165-2020

46

Shrestha A. Subedi B. Shrestha B. Shrestha A. Maharjan A. Bhattarai P. K. et al . (2023). Projected trends in hydro-climatic extremes in small-to-mid-sized watersheds in eastern Nepal based on CMIP6 outputs. Clim. Dyn.61, 4991–5015. doi: 10.1007/s00382-023-06836-1

47

Tehrani M. J. Bozorg-Haddad O. Pingale S. M. Achite M. Singh V. P. (2022). “Introduction to key features of climate models” in Climate change in sustainable water resources management. ed. Bozorg-HaddadO. (Berlin: Springer Nature), 153–177.

48

Usman M. Manzanas R. Ndehedehe C. E. Ahmad B. Adeyeri O. E. Dudzai C. (2022). On the benefits of bias correction techniques for streamflow simulation in complex terrain catchments: a case-study for the Chitral River basin in Pakistan. Hydrology9:11. doi: 10.3390/hydrology9110188

49

Vichi M. Lovato T. Lazzari P. Cossarini G. Gutierrez Mlot E. Mattia G. et al . (2015). The biogeochemical flux model (BFM): equation description and user manual. BFM version5:104. Available online at: http://bfm-community.eu

50

Wang H.-M. Chen J. Xu C.-Y. Zhang J. Chen H. (2020). A framework to quantify the uncertainty contribution of GCMs over multiple sources in hydrological impacts of climate change. Earths Future8:e2020EF001602. doi: 10.1029/2020EF001602

51

Wang H. Wang B.-B. Cui P. Ma Y.-M. Wang Y. Hao J.-S. et al . (2024). Disaster effects of climate change in High Mountain Asia: state of art and scientific challenges. Adv. Clim. Change Res.15, 367–389. doi: 10.1016/j.accre.2024.06.003

52

Wi S. Yang Y. C. E. Steinschneider S. Khalil A. Brown C. M. (2015). Calibration approaches for distributed hydrologic models in poorly gaged basins: implication for streamflow projections under climate change. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci.19, 857–876. doi: 10.5194/hess-19-857-2015

53

Wilby R. L. Harris I. (2006). A framework for assessing uncertainties in climate change impacts: low-flow scenarios for the river Thames, UK. Water Resour. Res.42:W02419. doi: 10.1029/2005WR004065

54

Wu Y. Miao C. Fan X. Gou J. Zhang Q. Zheng H. (2022). Quantifying the uncertainty sources of future climate projections and narrowing uncertainties with bias correction techniques. Earths Future10:e2022EF002963. doi: 10.1029/2022EF002963

55

Xu Z. Han Y. Yang Z. (2019). Dynamical downscaling of regional climate: a review of methods and limitations. Sci. China Earth Sci.62, 365–375. doi: 10.1007/s11430-018-9261-5

56

Xu Z. Yang Z.-L. (2015). A new dynamical downscaling approach with GCM bias corrections and spectral nudging. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos.120, 3063–3084. doi: 10.1002/2014JD022958

57

Xue Y. Houser P. Maggioni V. Mei Y. Kumar S. Yoon Y. (2020). Evaluation of High Mountain Asia -land data assimilation system part I: a hyper-resolution terrestrial modeling system. Hydrology105:essoar-10504630. doi: 10.1002/essoar.10504630.1

58

Yang L. Zhao G. Mu X. Liu Y. Tian P. Puqiong et al . (2023). Historical and projected evolutions of glaciers in response to climate change in High Mountain Asia. Environ. Res.237:117037. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.117037

59

Yaseen M. Waseem M. Latif Y. Azam M. I. Ahmad I. Abbas S. et al . (2020). Statistical downscaling and hydrological Modeling-based runoff simulation in trans-boundary mangla watershed Pakistan. Water12:3254. doi: 10.3390/w12113254

60

Yukimoto S. Kawai H. Koshiro T. Oshima N. Yoshida K. Urakawa S. et al . (2019). The meteorological research institute earth system model version 2.0, MRI-ESM2.0: description and basic evaluation of the physical component. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II.97, 931–965. doi: 10.2151/jmsj.2019-051

61

Zamora R. A. Zaitchik B. F. Rodell M. Getirana A. Kumar S. Arsenault K. et al . (2021). Contribution of meteorological downscaling to skill and precision of seasonal drought forecasts. J. Hydrometeorol.22, 2009–2031. doi: 10.1175/JHM-D-20-0259.1

62

Zhu Y.-Y. Yang S. (2020). Evaluation of CMIP6 for historical temperature and precipitation over the Tibetan plateau and its comparison with CMIP5. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res.11, 239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.accre.2020.08.001

Summary

Keywords

climate downscaling, High Mountain Asia, streamflow projections, water resources, glacio-hydrological model

Citation

Nair AV, Araujo DSA, Gutmann E, Wi S, Phuntshok J, Toeb K, Hassan M, Kayastha RB and Nikolopoulos EI (2025) On the effects of climate downscaling for projecting hydrologic response of catchments in High Mountain Asia. Front. Water 7:1611141. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2025.1611141

Received

13 April 2025

Revised

15 September 2025

Accepted

13 November 2025

Published

27 November 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Mehebub Sahana, The University of Manchester, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Zhenyu Zhang, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States

Hongxing Zheng, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Nair, Araujo, Gutmann, Wi, Phuntshok, Toeb, Hassan, Kayastha and Nikolopoulos.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Efthymios I. Nikolopoulos, efthymios.nikolopoulos@rutgers.edu

Disclaimer