- 1Independent Consultant, Washington, DC, United States

- 2Independent Consultant, San Rafael, CA, United States

- 3Independent Consultant, St. Louis, MO, United States

Young people around the world are experiencing a range of emotional responses to the climate crisis. While many are organizing for action, most policies and programs addressing climate change do not consider their mental wellbeing or include them as active participants in climate decision making. In this perspective, we present a case for (1) the importance of youth’s eco-emotions in the face of climate change and their desire to be engaged in climate-related actions; and (2) the value of evidence-based public health frameworks to support building young people’s emotional resilience and integrating them into climate responses. Drawing from two recent scoping reviews and our experience in youth-centered public health programs, we describe how eco-emotions, such as eco-anxiety, eco-trauma, grief, and hope, are being experienced by adolescents and young adults. These emotions can be intense, but they also hold the potential to motivate action and connection. Our review of global climate resilience policies shows that emotional resilience is rarely addressed, and young people are largely absent from these plans. We make the case for using existing public health frameworks like Positive Youth Development (PYD) and Social Emotional Learning (SEL) to support youth mental wellness and resilience in climate programming. These approaches are already used in health and education and can be adapted to climate efforts to build young people’s emotional skills, agency, and engagement. Finally, we describe types of low-cost, evidence-based interventions that can be added to existing programs in ways that are community-based, non-clinical, and culturally appropriate. These offer a starting point for rethinking climate action as something that must include young people and their emotional well-being.

Introduction

Young people are increasingly concerned about climate change and how ecological and societal ‘unraveling’ predictions (Macy and Johnstone, 2012) will affect their futures (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2021, United Nations Children’s Fund, 2023a). Adolescents and young adults are organizing as climate activists in countries and communities around the globe (Nisbett and Spaiser, 2023; UN CC:Learn, 2023). Yet young people have not been systematically included in deliberations and as decision-makers. For example, the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) in 2021 was the first time youth had formal representation. Global policies and program strategies are out of step with the needs of the largest cohort of young people ever to live on the planet. They fail to recognize the crucial role young people can play in addressing the climate crisis. Nor do they include mental wellness in climate adaptation and mitigation response.

The public health disciplines offer evidence and expertise that can inform the design of effective policies and programs that engage youth. Participatory community-based research, programming, and other youth-adult partnership initiatives in health can inform the conceptualization of young people as actors in climate change policy and programs addressing resilience. These human rights-based approaches recognize that young people present an untapped resource for driving change (Arora et al., 2022). Youth want to be involved; studies of Gen Z, defined as people born between 1997 and 2012 (Dimock, 2019), show that they often cite mental health, the environment, and social inequality as their top social issues (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2021; Deloitte Insights, 2024). More than anyone, they are deeply invested in fostering a healthy, just, and resilient future, as they are affected by the immediate and the long-term effects of climate change. As the research deepens on how young people bring new perspectives to issues that adults cannot envision (Stevenson, 2020), the climate and public health communities are remiss in not engaging young people alongside adults in envisioning new responses. Therefore, this paper aims to present a case for (1) the importance of youth’s eco-emotions in the face of climate change and their desire to be engaged in climate-related actions; and (2) the value of evidence-based public health frameworks to support building young people’s emotional resilience and integrating them into climate responses.

In this Perspective, we propose opportunities for effective programming at the intersection of climate change, adolescence, and mental wellness. Our view is informed by decades of work as program researchers and designers of community-centered and youth-focused public health programs in the Global South, as well as work with nonprofits addressing climate-related mental wellness. While most research has focused on the Global North, adolescents and young adults in Global South communities face similar realities.

We begin by describing the youth experience of eco-emotions in the Global South. We then introduce the widely recognized framework of positive youth development, which focuses on resilience building as both a process and an outcome, emphasizing the importance of socio-emotional skills, youth voice, and their rights to participate in identifying, proposing, and being part of solutions. We close by making the case for integrating young people and emotional resilience as a first-line response.

Youth emotional responses to the climate crisis in the global south

A growing body of research links climate change to worsening mental health and emotional well-being (Helldén et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2022; World Health Organization, 2022). Eco-emotions, sometimes called climate emotions, refer to the emotional impact of environmental degradation (Cianconi et al., 2023). These mental health impacts can arise from direct experiences of one or more extreme weather events, their consequences, and learning about, understanding, or anticipating the risks and impacts of climate change (Cianconi et al., 2023; Murphy, 2024).

We conducted two scoping reviews in 2022 and 2024 of peer-reviewed and gray literature to understand the eco-emotions, thoughts, and mental states of adolescents and young adults concerning the climate crisis. The second review sought to update the first review with literature published between 2023 and 2024. The review followed a step-wise process of conducting keyword searches in peer-reviewed databases and on Google for gray literature. Abstracts of identified articles and reports were reviewed for eligibility. All eligible manuscripts and reports were reviewed in full; data were extracted in a matrix. Thematic analysis was conducted to identify patterns and gaps. Our 2022 scoping review identified 37 peer-reviewed articles, most of which were descriptive studies conducted in the Global North. The 2024 update review identified 134 new articles. Proportionally, the 2024 review identified more articles surveying Global South youth compared to the 2022 review. The scoping reviews confirmed that the phenomenon of eco-distress is affecting youth globally, including in the Global South.

The 2024 update review confirmed research on the growing awareness of how escalating climate threats can lead to significant psychological distress, which is felt acutely by young people worldwide (Lawrance et al., 2022). Hickman and colleagues (Hickman et al., 2021), for example, surveyed people aged 16–25 living in 10 countries across five continents about their emotional reactions to climate change. Nearly two-thirds were extremely worried about climate change, and 45% reported these feelings impacted their daily lives (Hickman et al., 2021). Participants described believing ‘humanity is doomed’ and fearing they would lack the same opportunities as their parents had (Hickman et al., 2021).

Notably, the 2024 update review showed a more nuanced and complex take on youth mental health and climate change. New descriptors of eco-emotions were proposed, and studies moved away from pathologizing the phenomenon as a siloed problem. Some research indicated that eco-optimism is a response to feelings of eco-anxiety that can channel the emotional experience into activism. As will be discussed in subsequent sections, the expanded conceptualization and definitions offer new possibilities to move program responses into community-based youth mental wellness approaches.

Eco-anxiety, a commonly used term to describe the emotional reactions to climate change, is understood now to be a family of distinct but connected emotions that may be simultaneously felt by teens, including guilt, depression, or a sense of powerlessness (Pihkala, 2020; Kurth and Pihkala, 2022). Eco-anxiety can cause intense and overwhelming feelings where simple solutions are insufficient to address the issue (Hickman et al., 2021). Eco-anxiety can also be felt as a rational and practical response to climate change, as it can have the beneficial effect of alerting people to a problem and motivating them to respond (Cianconi et al., 2023).

New psychological categories have also been proposed, including 19 distinct ecological emotions (Cianconi et al., 2023). New descriptors of eco-emotions have emerged, including eco-distress, eco-trauma, eco-paralysis, and terrefurie (i.e., rage related to the destruction of the earth) (Cianconi et al., 2023). There is also recognition that current categories are not capturing the full emotional spectrum of youth across cultures, particularly those associated with experiences of loss related to climate change (Dodds, 2021). For example, the term solastalgia, initially proposed by the ecopsychologist Glenn Albrecht to describe a feeling of homesickness by Aboriginal people in Australia when their home became unrecognizable due to coal mining’s effect on the environment (Pihkala, 2020), may not fully capture the experience of loss closely connected to the culture, identity, and well-being of other Indigenous communities, such as Pacific Islanders (Cunsolo and Ellis, 2018).

In the last several years, a shift away from mental illness to mental wellness has expanded how eco-emotions are defined operationally and how they can support youth engagement. In this framing, emotional responses to climate change are considered common and are based on a person’s experience or knowledge of climate change. A 2023 UNICEF USA study in 15 countries across five continents explored perspectives, experiences, actions, and demands of youth in dealing with eco-anxiety and climate change (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2023b). Young people described how they manage eco-anxiety, with approaches ranging from eco-optimism to eco-apathy (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2023b). Young people elsewhere have described feelings of hopelessness, grief, anger, and how they affect daily life (Diffey et al., 2022). These feelings are also driven by their reactions to the lack of political and corporate action and the limited inclusion and influence of youth on national and global systems (Godden et al., 2021; Diffey et al., 2022).

The UNICEF USA study and studies by Ojala (2015) and Godden et al. (2021) elaborate on constructive hope (compared to hope rooted in denial of the importance of climate change), describing how taking action for climate helps youth feel good, proud, connected to the community, and hopeful (Godden et al., 2021). A 2021 commentary written by 23 young people from 15 countries across four continents provides a firsthand account of their feelings, experiences, and hopes. Reflecting how eco-emotions can fuel youth efforts, it calls for radical compassion, meaningful intergenerational collaboration, climate-related mental health support, and climate action by policymakers and business leaders (Godden et al., 2021; Diffey et al., 2022).

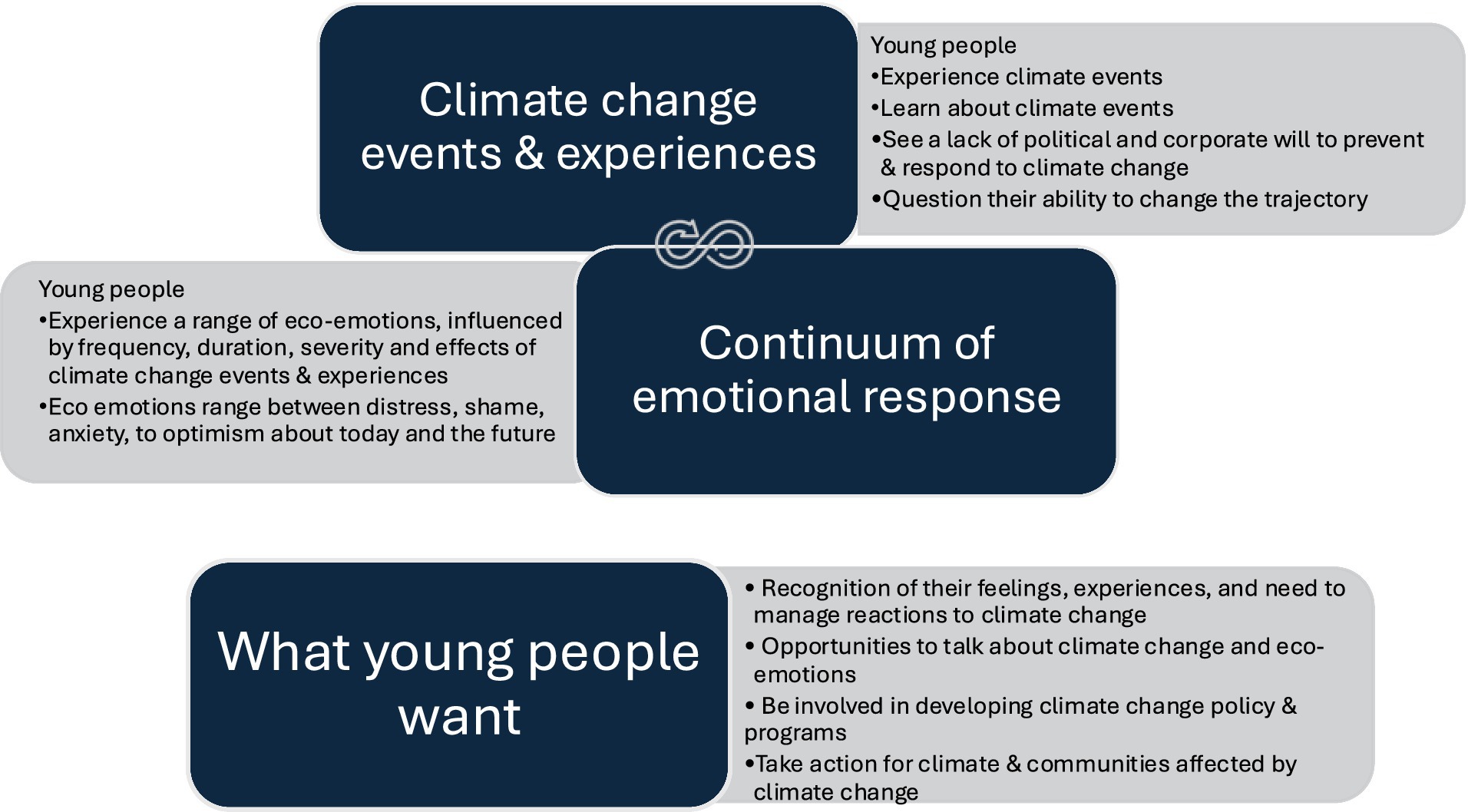

Figure 1 summarizes these trends. Climate events, experiences, and awareness are affecting youth emotionally, ranging from distress to optimism (upper two boxes). This continuous interaction will persist throughout a person’s life and needs to be managed to create emotional balance in a changing world. Simultaneously, young people want to engage in numerous ways and include emotional wellness as part of the solution (bottom box). Young people are already organizing around the world as climate activists. An opportunity exists to further engage with young people as a crucial cohort for climate action, enabling them to envision and confront the complexities of the crisis in new ways.

Figure 1. Listening to young people - recognizing eco-emotional realities and taking program actions.

The absence of eco-emotions as a frontline response in climate resilience conceptualization

Policies and programs addressing the consequences of climate change often aim to build individual, community, and systemic resilience. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines climate resilience as “the capacity of social, economic, and environmental systems to cope with a hazardous event, trend, or disturbance, responding or reorganizing in ways that maintain essential function, identity, and structure while also maintaining the capacity for adaptation, learning, and transformation” (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2025). The IPCC also focuses on increasing climate resilience by reducing the vulnerability of people, communities, countries, and natural environments. On the human societal side, reducing vulnerability and increasing resilience tends to focus on technological and infrastructural changes, such as drought-resistant crops, heat-resistant buildings, and policy, such as laws and regulations on agricultural production (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2025). Our 2025 exploratory review of 20 global policies and strategic action plans revealed a similar focus on technology and infrastructure aimed at reducing vulnerability and building human resilience. The absence of psychological or emotional resilience is remarkable; language on this type of resilience, which underpins the ability of individuals, communities, and societies to act and react, was only seen in documents explicitly addressing mental wellness. Noteworthy also is the near absence of young people as either a beneficiary group or as stakeholders in preparing for the future.

Learning from youth-focused public health programs and research

When climate policy and action plans incorporate mental well-being and focus on susceptible groups, such as adolescents and young adults, the odds are better for coordinated, cross-sectoral responses. Well-accepted and evidence-based frameworks, particularly Positive Youth Development (PYD), which incorporates meaningful youth participation and social–emotional skills development, are utilized in adolescent and young adult programming. They are already widely used in development programming, including health, education, democracy and governance, and economic development sectors in the Global South (Chowa et al., 2023). They can be adapted for mental wellness and climate change.

PYD fosters individual and external protective factors that support the development of young people. At the personal level, PYD aims to build young people’s assets, creating health, cognitive, social, psychological, and emotional well-being, and agency to make decisions and act. Beyond the individual, fostering a supportive environment in families, schools, communities, and at higher government and civil society levels provides opportunities for young people to engage, share their unique perspectives and inputs on addressing issues, and develop their skills, ultimately leading to healthy relationships and societal roles as adults. A key principle underlying PYD-informed approaches is meaningful youth engagement or participation (versus tokenistic approaches to include youth, which is often an issue with adult-centric decision-making). Also underpinning PYD is social-psychological-emotional asset-building, which enhances attitudes toward oneself and others and reduces emotional and high-risk behaviors. Although implicit, fostering young people’s social–emotional learning (SEL) skills is also a key component of PYD approaches (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2025). SEL skill domains are often classified as internal (self-awareness and self-management) and fostering a supportive environment (social awareness and relationship skills), which lead to responsible decision-making (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2025). SEL skills are critical to supporting the healthy growth, resiliency, and well-being of all young people and offer a practical way to address mental wellness.

The good news is that PYD concepts and SEL are slowly entering the climate change discourse based on articles exploring their utility in climate change adaptation and resilience building. See, for example, Gomez-Baya et al. (2020) “Environmental Action as Asset & Contribution of Positive Youth Development” and Ardoin et al. (2022) “Positive youth development outcomes and environmental education: a review of research.”

What works to build youth mental well-being and emotional resilience and the feasibility of adding them to climate change programs

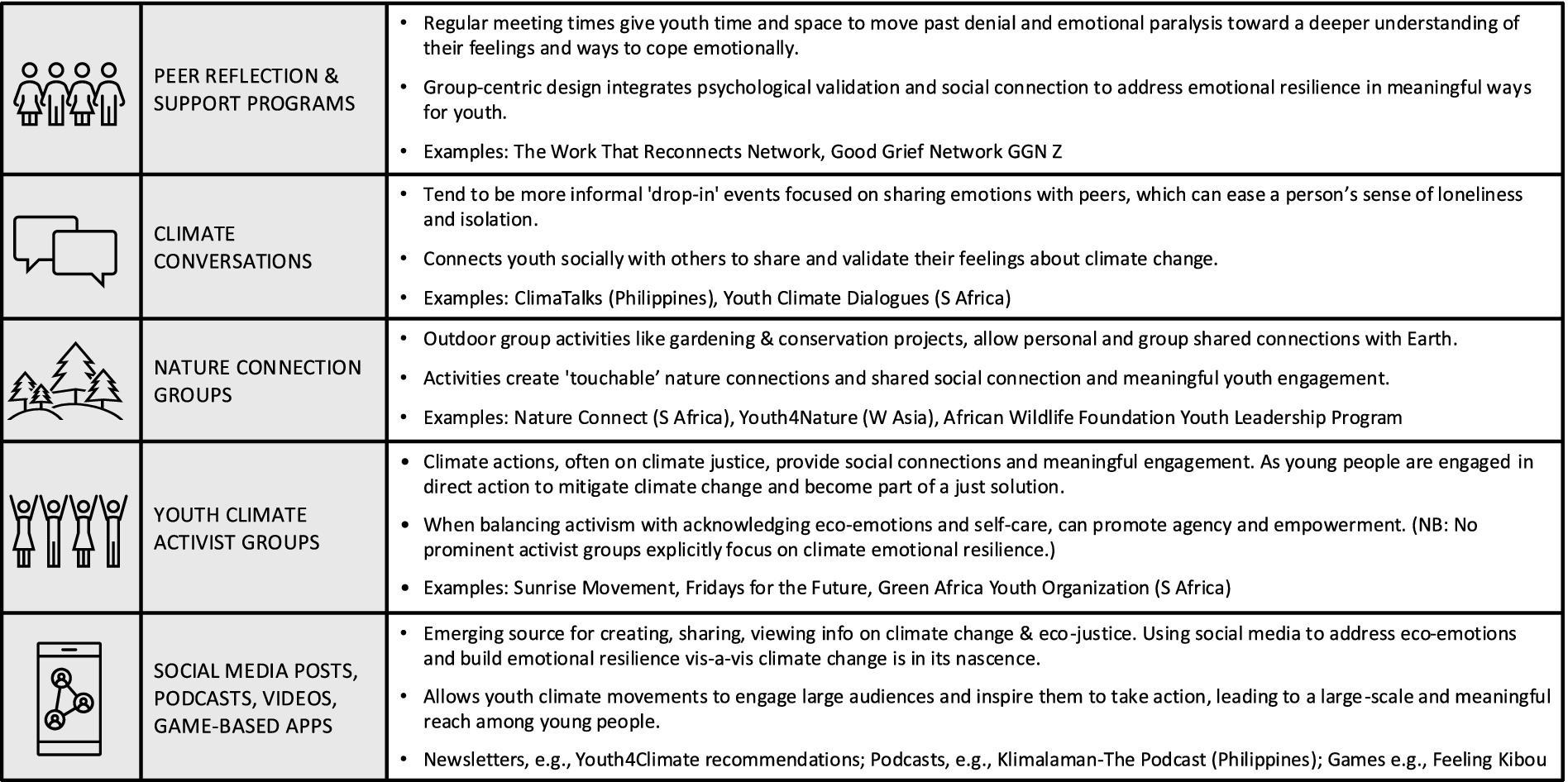

Although the number of community-based and social media-based climate resilience programs and projects targeting teens and young adults is skyrocketing, very few have been rigorously evaluated. We can, for now, use better practices designed to help teens and young adults cope with stress and trauma and /or promote emotional resilience more generally. A recent analysis indicated important characteristics of such interventions (i) acknowledge and validate feelings; (ii) build emotional coping skills; (iii) create social connection; (iv) create a connection with nature; (v) engage in climate action; (vi) practice self-care; (vii) foster climate justice awareness; and (viii) forge meaningful youth engagement. Figure 2’s left-hand column shows the five types of evidence-based interventions that can build emotional resilience. The right-hand column provides a brief description of the approaches and explanations how interventions contribute to emotional resilience. Each intervention type includes two or more mechanisms that research shows help young people foster emotional resilience (Dooley et al., 2021). Note that these intervention types are all underpinned by meaningful youth engagement principles (United Nations, 2023).

Figure 2. Getting Practical - integrating Tested Youth Interventions that Build Emotional Resilience into Existing Climate Change Programs. (Sources Dooley et al., 2021; United Nations, 2023).

Such interventions do not require a counselor or therapist to lead them; instead, trained local facilitators implement them in socially and culturally appropriate ways. Most use experiential-based activities to process feelings (compared to more fact-based activities to educate on climate change) and build group social connections. They work at both an individual level and an interpersonal and/or community level. Most are time-limited, meaning they could be added to ongoing projects. By selecting one or two intervention types to include in programs focused on climate resilience and adaptation, we believe that existing community-based programs in agriculture, conservation, health, education, and other sectors could be adjusted in small yet significant ways to increase program impact and effectiveness. As the intervention types are already utilized in public health and other programs, experienced practitioners exist in various sectors, including health, education, governance, and economic development, to help guide these necessary adjustments (Figure 2).

A call for integrated climate action: incorporating adolescents and young adults and emotional resilience

The nexus of climate change, adolescence, and mental wellness is a nascent area of climate action. Research shows that young people are aware of and concerned about climate change around the world. They understand the complexity of the challenges and can offer solutions that adults may not have envisioned. The growing research and conceptualization on the magnitude and relationship between climate change and youth eco-emotions is showing that eco-emotions are more varied than initially understood. Distress-related emotions, such as eco-anxiety and eco-trauma, and grief-related emotions, co-exist with optimistic emotions. What causes this range of responses and what helps youth experience more optimism or engage in action in response to climate change is unclear, but it provides a springboard for action.

Public health disciplines have developed, evaluated, and adapted frameworks that can guide this process to advance climate action at this nexus and lead to better resilience outcomes. Across sectors, PYD, SEL, and meaningful youth participation are accepted as frameworks and could advance this work.

There are opportunities to build youth resilience by engaging young people in emotional resilience-building activities, offering services and support, and providing avenues to become part of the solution in supporting their peers, families, and communities. Grappling with climate change is essential for youth well-being and the planet’s health. Leveraging lessons learned from decades of global health programming can support the development of more relevant and effective responses that engage youth as leaders, program designers, decision-makers, and participants from the outset, providing an integrated climate-health-mental wellness response.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AK: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization, Visualization, Project administration. SI: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization, Visualization, Project administration. LR: Formal analysis, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2021). Social issues that matter to generation Z. Available online at: https://www.aecf.org/blog/generation-z-social-issues [Accessed May 8, 2025].

Ardoin, N., Bowers, A., Kannan, A., and O’Connor, K. (2022). Positive youth development outcomes and environmental education: a review of research. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 27, 475–492. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2022.2147442

Arora, R., Spikes, C. F., Waxman-Lee, R., and Arora, R. (2022). Platforming youth voices in planetary health leadership and advocacy: an untapped reservoir for changemaking. Lancet Planet. Health 6:e78-e80. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00356-9

Chowa, G., Masa, R., Manzanares, M., and Bilotta, N. (2023). A scoping review of positive youth development programming for vulnerable and marginalized youth in low- and middle-income countries. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 154:107110. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.107110

Cianconi, P., Hanife, B., Grillo, F., Betro, S., Lesmana, C. B. J., and Janiri, L. (2023). Eco-emotins and psychoterratic syndromes: reshaping mental health assessment under climate change. Yale J. Biol. Med. 96, 211–226. doi: 10.59249/EARX2427

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2025). SEL and mental health. Available online at: https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/how-does-sel-support-your-priorities/sel-and-mental-health/ [Accessed 25 June 2025].

Cunsolo, A., and Ellis, N. R. (2018). Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 275–281. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2

Deloitte Insights. (2024). Gen zs and millennials find reasons for optimism despite difficult realities. Available online at: https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/talent/deloitte-gen-z-millennial-survey.html [Accessed May 8, 2025].

Diffey, J., Wright, S., Uchendu, J. O., Masithi, S., Olude, A., Juma, D. O., et al. (2022). “Not about us without us” – the feelings and hopes of climate-concerned young people around the world. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 34, 499–509. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2022.2126297

Dimock, M. (2019). Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins

Dodds, J. (2021). The psychology of climate anxiety. BJPsych Bull. 45, 222–226. doi: 10.1192/bjb.2021.18

Dooley, L., Sheats, J., Hamilton, O., Chapman, D., and Karlin, B. (2021). Climate change and youth mental health: Psychological impacts, resilience resources, and future directions. Los Angeles, CA: See Change Institute.

Godden, N. J., Farrant, B. M., Yallup, F. J., Heyink, E., Carot, C. E., Burgemeister, B., et al. (2021). Climate change, activism, and supporting the mental health of children and young people: perspectives from Western Australia. J. Paediatr. Child Health 57, 1759–1764. doi: 10.1111/jpc.15649

Gomez-Baya, D., Tomé, G., Branquinho, C., and de Gaspar Matos, M. (2020). Environmental action as asset and contribution of positive youth development. Erebea 10, 53–68. doi: 10.33776/erebea.v10i0.4953

Helldén, D., Andersson, C., Nilsson, M., Ebi, K. L., Friberg, P., and Alfvén, T. (2021). Climate change and child health: a scoping review and an expanded conceptual framework. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e164–e175. doi: 10.1016/s2542-5196(20)30274-6

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pinkhala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., Mayall, E. E., et al. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e863–e873. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2025). FAQ 6: What is climate resilient development and how do we pursue it? Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/about/frequently-asked-questions/keyfaq6/ [Accessed June 25, 2025].

Kurth, C., and Pihkala, P. (2022). Eco-anxiety: what it is and why it matters. Front. Psychol. 13:981814. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.981814

Lawrance, E. L., Thompson, R., Le Vay, J. N., Page, L., and Jennings, N. (2022). The impact of climate change on mental health and emotional wellbeing: a narrative review of current evidence, and its implications. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 34, 443–498. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2022.2128725

Macy, J., and Johnstone, C. (2012). Active Hope: How to face the mess We’re in without going crazy. California: New World Library.

Martin, G., Reilly, K., Everitt, H., and Gilliland, J. A. (2022). Review: the impact of climate change awareness on children’s mental well-being and negative emotions - a scoping review. Child Adolesc. Mental Health 27, 59–72. doi: 10.1111/camh.12525

Murphy, V. (2024). Climate change disproportionately affects mental health of vulnerable people. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/254993/climate-change-disproportionately-affects-mental-health/ [Accessed on June 28, 2025].

Nisbett, N., and Spaiser, V. (2023). Moral power of youth activists – transforming international climate politics? Glob. Environ. Change 82:102717. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102717

Ojala, M. (2015). Hope in the face of climate change: associations with environmental engagement and student perceptions of teachers’ emotion communication style and future orientation. J. Environ. Educ. 46, 133–148. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2015.1021662

Pihkala, P. (2020). Eco-anxiety and environmental education. Sustainability 12:10149. doi: 10.3390/su122310149

Stevenson, C.. (2020). Are adolescents more creative than adults? Available online at: https://boldscience.org/are-adolescents-more-creative-than-adults/ [Accessed June 10, 2025].

UN CC:Learn. (2023). 2022/2023 youth and climate change survey. Available online at: https://www.uncclearn.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/2022-2023-Youth-and-Climate-Change-Global-Survey-Results_final61.pdf [Accessed June 10, 2025[.

United Nations. (2023). Our common agenda policy brief 3: meaningful youth engagement in policy and decision-making processes. Available online at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4009368?ln=en&v=pdf [Accessed June 25, 2025].

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2021). The climate crisis is a child rights crisis: introducing the children’s climate risk index. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/media/105376/file/UNICEF-climate-crisis-child-rights-crisis.pdf [Accessed June 10, 2025].

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2023a). From eco-anxiety to eco-optimism: listening to a generation of resilient youth. Available online at: https://www.unicefusa.org/sites/default/files/2023-09/UUSA_EcoOptimism_Report.pdf [Accessed on June 10, 2025].

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2023b). The climate-changed child: a children’s climate risk index supplement. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/media/147931/file/Theclimage-changedchild-ReportinEnglish.pdf [Accessed on June 10, 2025].

World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health and climate change: policy brief. Available online at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/354104/9789240045125-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed June 10, 2025]

Keywords: climate, eco emotions, adolescents, positive youth development, socio emotional learning, mental health

Citation: Kohli A, Igras S and Ramirez L (2025) Mind the gap: bringing adolescents and young adults and emotional resilience into climate action. Front. Clim. 7:1657851. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2025.1657851

Edited by:

Adugna Woyessa, Ethiopian Public Health Institute, EthiopiaReviewed by:

Waltaji Kutane, World Health Organization Ethiopia, EthiopiaPamela Kaithuru, The Catholic University of Eastern Africa Faculty of Education, Kenya

Copyright © 2025 Kohli, Igras and Ramirez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anjalee Kohli, YW5qYWxlZS5rMkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

Anjalee Kohli

Anjalee Kohli Susan Igras

Susan Igras Lacey Ramirez

Lacey Ramirez