- 1Department of Humanities, MacEwan University, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- 2Department of Psychology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

This paper presents a series of three studies describing how reading literature promotes empathy and moral outcomes. We add three contrasts to this field of empirical study: (a) an explanatory and interpretative form of narrative reading engagement (Integrative Comprehension) is contrasted with an expressive and explicative form of aesthetic reading engagement (Expressive Enactment); (b) an explanatory and interpretive form of cognitive perspective-taking (a component of Integrative Comprehension) is distinguished from an expressive and explicative form of empathy (a component of Expressive Enactment); and (c) a local form of moral outcome (involving changes in attitude toward a specific group or outgroup) is distinguished from a global form of moral outcome (involving an inclusive respect for human subjectivity). These contrasts are clarified and contextualized within existential-phenomenological discussions of sense-giving lived experience, agency, and morality. In conclusion, we offer a framework that specifies the potential impact on wellbeing of a form of literary reading that involves existential reflection, especially as conceived within the emerging field of existential positive psychology.

Introduction

That reading literature can promote empathy and related prosocial attitudes is not a new claim. Aristotle's Poetics often is referred to as the first record of such a claim, although more recent versions are abundant. Authors and poets (e.g., Victor Hugo, Harper Lee, Rabindranath Tagore, Leo Tolstoy), philosophers (e.g., Jürgen Habermas, Martha C. Nussbaum, Jenefer Robinson, Richard Rorty, Robert Solomon), historians (e.g., Robert Darnton, Lynn Hunt), literary scholars (e.g., Susan Keen, Lisa Zunshine), psychologists (e.g., Emanuele Castano, Raymond Mar, Keith Oatley), and interdisciplinary scholars (e.g., Mark Bracher, Frank Hakemulder, Emy Koopman) seem to agree that literature has a positive effect on our capacity to empathize with people different from ourselves and to contribute to our moral growth.

Indeed, there is robust evidence that lifetime exposure to fiction is positively correlated with social cognitive and empathic abilities, although the correlation is rather small (Mumper and Gerrig, 2017). There is also evidence that reading fictional texts at least briefly boosts social cognition and empathy more than does reading non-fiction or no text at all, but, here too, the effect sizes are marginal (Dodell-Feder and Tamir, 2018). As Mar (2018) points out, it is also possible that a third variable, such as transportation or absorption, is responsible for the correlation between social cognition and empathy.

Some scholars have begun to examine how individual differences affect the relation between literary reading and social cognition. The tendency to become absorbed—or transported into—the world of a narrative text has been given particular attention (see Kuijpers et al., 2021 for a review). In their seminal accounts, Nell (1988) referred to the impact of becoming “lost in a book,” Gerrig (1993) described the effects of “transportation” into the world of the text, and Busselle and Bilandzic (2009) examined how “narrative engagement” affects story-related attitudes. In empirical studies based on Gerrig's discussion of transportation, Green and Brock (2000) and Green (2002) provide evidence that readers who are transported into a narrative (i.e., attentionally focused on and emotionally invested in the vividly imagined world of the text) are more likely to be persuaded by the narrative (i.e., to report story-congruent beliefs) than are those who are not transported. van Laer et al. (2014) provide a “transportation-imagery” version of this hypothesis (involving identifiable characters and story verisimilitude) and suggest that the effects of transportation are mediated by an increase in story-consistent affective responses (identifiable characters) and (b) a decrease in critical thoughts (counterarguments).

In an attempt to clarify the reader characteristics that mediate attitude change, Johnson (2012) found that participants reporting transportation also scored higher on affective empathy. In a follow-up study, Johnson (2013) investigated the effect of fiction reading on the reduction of prejudice against Muslims. In line with the transportation-persuasion model, he employed a text with a female Muslim protagonist who defied negative Muslim prejudices. Johnson found that transportation into the narrative, as measured by Green and Brock (2000) transportation scale, correlated positively with prejudice reduction. Moreover, he reported regression analyses indicating that affective empathy, as measured by Batson et al. (1997), mediated the effects of transportation on prejudice reduction.

Bal and Veltkamp (2013) similarly found that high levels of transportation into a fictional narrative were associated with higher levels of affective empathy, as measured by the empathic concern subscale of Davis (1983) Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Moreover, levels of empathy remained elevated 1 week after initial post-reading measurement. In contrast, reading a non-fiction text did not lead to higher levels of affective empathy, presumably because non-fiction does not provide the same opportunities as narrative fiction to generate vivid imagery and identify with a character (Green, 2005).

Efforts to explain how reading evokes empathy and shapes social cognition point either to the transmission of social knowledge or to the social value of the processes that readers rehearse while reading, including empathizing with characters. Regarding the latter hypothesis, Mar (2018) argues that social processes such as mental inferencing, affective empathy, etc., may be enhanced by stories that evoke and rehearse the social cognitive mechanisms through which we understand our social world.

In this paper, we use distinctions grounded in existential-phenomenological philosophy to add conceptual nuance to this discussion of absorption, empathy, and changes in social cognition. Specifically, we adopt Kuiken and Douglas (2017) contrast between two forms of absorbed reading engagement, as measured by the Absorption-Like States Questionnaire (ASQ): Expressive Enactment (ASQ-EE) and Integrative Comprehension (ASQ-IC). Each of these forms of absorption involves empathy-like social cognition—but in a rather different form than was addressed in previous studies. Briefly, Expressive Enactment subsumes an expressive, meaning-explicating form of empathy-like social cognition, whereas Integrative Comprehension subsumes an interpretive, explanation-seeking form of empathy-like social cognition. The distinction between these two forms of empathy-like response differs from the distinction between affective and cognitive empathy that was invoked to explain the results of the Johnson (2012, 2013) and Bal and Veltkamp (2013) research (see also Melchers et al., 2015; Healey and Grossman, 2018). Moreover, Kuiken and Douglas (2017, 2018) and Kuiken et al. (2021) have repeatedly found that Expressive Enactment and Integrative Comprehension—and the contrasting forms of empathy-like social cognition that they subsume—differentially predict aesthetic, explanatory, and pragmatic reading outcomes. For example, Expressive Enactment mediates the relationship between Open Reflection and self-altering aesthetic outcomes, such as inexpressible realizations, self-perceptual depth, and sublime feeling, while Integrative Comprehension mediates the relationship between Open Reflection and narrator intelligibility, causal explanation, and explanatory cohesion.

We emphasize and elaborate here how the “self-perceptual depth” that is reliably an outcome of Expressive Enactment involves a global (or existential) sense of self (Kuiken and Sopcak, 2021: 310). As measured in the present research (Kuiken et al., 2012), our conception of “self-perceptual depth” was derived from studies of self-perceptual change reported after (a) intensive therapeutic reflection (Kuiken et al., 1987); (b) impactful dreams (Kuiken and Sikora, 1993); and (c) self-altering reading (Kuiken et al., 2004; Sikora et al., 2011). Items on this instrument reflect existential feelings, especially convictions about aspects of a person's orientation toward broadly inclusive states of affairs (e.g., “I felt sensitive to aspects of my life that I usually ignore”; “I felt that my understanding of life had been deepened”; “I felt like changing the way I live”).

In the present paper, we supplement this global (and existential) sense of self with a similarly global (and existential) sense of others. In a series of three studies, we examine the contrast between global and local forms of moral outcome. Local forms of moral outcome include changes in racist and anti-immigrant attitudes toward a specific group or outgroup, that is, what Zick et al. (2011) refer to as Group-Focused Enmity. Global forms of moral outcome, in contrast, involve an inclusive, other-directed respect for the complexities of human subjectivity—or what we have called “non-utilitarian respect” (Kuiken et al., 2012). Items used to assess non-utilitarian respect include “It seemed wrong to treat people like objects”; “I was keenly aware of people's inherent dignity”; “I felt deep respect for humanity.”

Study 1

The first study, a classroom study, explored whether empathy-like engagement with excerpts from a novel depicting the traumatic experience and aftermath of attending a Residential School would reduce prejudice toward the Canadian Indigenous population. We employed a well-established measure of empathy (Davis, 1983, the IRI), which distinguishes affective from cognitive empathy, and we also employed the ASQ, which contrasts an expressive and explicative form of empathy with an interpretive and explanatory form of cognitive perspective-taking.

Study 2

In Study 2, we examined whether global and local moral outcomes are differentially predicted by the ASQ-EE and ASQ-IC, respectively. Although excerpts from the same novel as used in Study 1 were used again, the measures of moral outcome no longer focused narrowly on prejudiced attitudes toward the Canadian Indigenous population. Rather we distinguished between decreases in prejudice toward outgroups (a local moral outcome) and increases in non-utilitarian respect (a global moral outcome).

Study 3

In Study 3, we conceptually replicated Study 2, but shifted from presentation of a text in which the explicit themes involved prejudice to presentation of a text in which the explicit themes involved honesty and integrity in intimate interpersonal relations. Our goal was to examine whether the effects of reading on pro-social attitudes are due to a generic reading process or to the narrative content of a specific text.

Discussion

Finally, in the discussion, we provide theoretical elaboration of a form of reading engagement that involves the expressive and explicative form of reading engagement captured by the ASQ-EE (Expressive Enactment). Our elaboration relies especially upon Husserl (2001) description of expressive and explicative sense-giving within lived experience. We argue further that this form of engagement is at the heart of existentialists' discussions of agency and freedom, especially how this form of expressive and meaning-explicating engagement affects the global moral outcomes emphasized in their philosophy.

Study 1

To explore the role that empathy-like social cognition plays in moral judgment, we examined changes in prejudice toward the Canadian Indigenous population after participants read a novel depicting the traumatic experience and aftermath of attending a Residential School. The classroom research setting enabled participants to engage a text that explicitly addresses prejudice within a research situation that supported close reading of the text. We also asked participants to complete questionnaires that assess several forms of empathy-like social cognition.

Materials and methods

Participants

The convenience sample of students participating in Study 1 consisted of 68 undergraduate students at MacEwan University, Canada, who were enrolled in one of two of the first author's introductory-level English courses and received partial course credit for participation. Forty-seven were women and twenty-one were men (Mage= 21.9, age range: 18–41 years). Participants in one course formed Group A (23 women, 12 men, 1 “it's complicated,” Mage= 23.9, age range: 18–41 years) and those in the other course formed Group B (24 women, 9 men, Mage= 19.8, age range: 18–31 years).

Materials

Davis' interpersonal reactivity index

Davis (1983) Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) is a multi-dimensional measure of trait empathy. It contains 28 items, distributed across four subscales of seven items each: (a) Perspective Taking (PT) – the tendency to spontaneously adopt the psychological point of view of others; (b) Fantasy (FS)—the tendency to project oneself imaginatively into the feelings and actions of fictitious characters in books, movies, and plays; (c) Empathic Concern (EC)—“other-oriented” feelings of sympathy and concern for unfortunate others; and (d) Personal Distress (PD)—“self-oriented” feelings of personal anxiety and unease in tense interpersonal settings (Davis, 1983). Our objective was to determine whether any of these aspects of trait empathy predict reading-induced changes in prejudiced attitudes toward the Canadian Indigenous population. We were particularly interested in the Fantasy subscale because it captures a form of absorption into narrative media; also, the Fantasy and Perspective Taking scales reflect the two forms of empathy that are prominent in contemporary scholarly literature: affective and cognitive empathy (Melchers et al., 2015).

Morrison's measure of prejudiced attitudes toward aboriginals in Canada

Morrison et al. (2008) developed the Prejudiced Attitudes Toward Aboriginals in Canada Scale (PATAS), which contains two subscales: the Old-Fashioned Attitudes Toward Aboriginals in Canada Subscale (O-PATAS) and the Modern Attitudes Toward Aboriginals in Canada Subscale (M-PATAS). The O-PATAS consists of 11 items and is grounded in the theory of and research on old-fashioned prejudice (e.g., Madon et al., 2001). It measures attitudes toward the perceived inferiority of the Canadian Indigenous population1, based on genetic race differences. The M-PATAS consists of 14 items based on the theory of and research on modern prejudice (e.g., Tougas et al., 1995). It measures modern prejudices such as that Indigenous people are no longer discriminated against, that they are too demanding and too proud of their cultural heritage, and that they receive special treatment. The O-PATAS and M-PATAS were used to assess text-congruent changes in prejudice, i.e., local moral outcomes.

Kuiken and Douglas's absorption-like states questionnaire

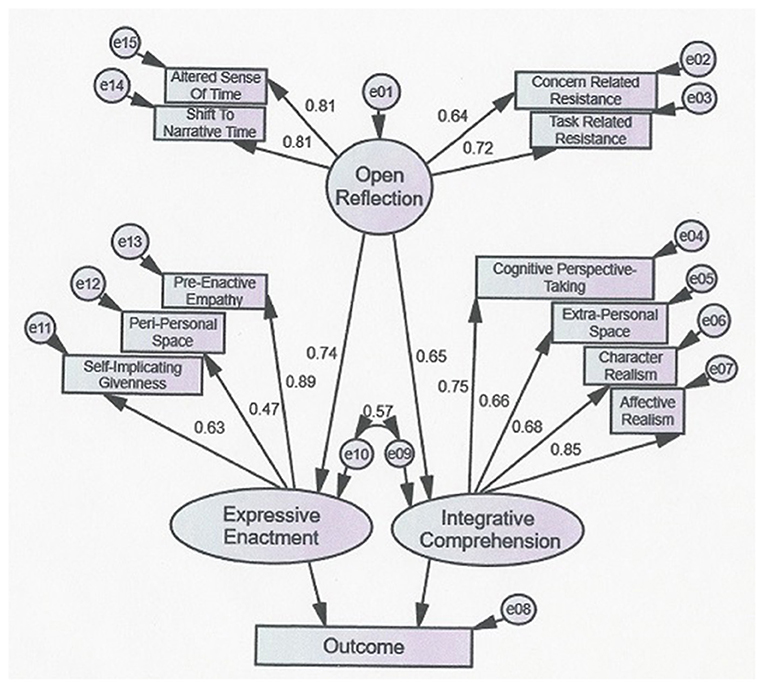

Kuiken and Douglas (2017) Absorption-Like States Questionnaire (ASQ) is a 37-item instrument that assesses (1) Open Reflection (ASQ-OR; with item parcels for sustained concentration and attentional flexibility); (2) Expressive Enactment (ASQ-EE; with item parcels for pre-enactive empathy, peri-personal space, and self-implicating “givenness”); and (3) Integrative Comprehension (ASQ-IC; with item parcels for cognitive perspective-taking, extra-personal space, affective realism, and realistic conduct). Previous studies indicate that, when these measures of absorption-like states are included within an appropriate SEM model (Kuiken and Douglas, 2017, 2018; Kuiken et al., 2021), openness to experience (Open Reflection) is the substrate of (a) an expressive and explicative form of reading engagement (Expressive Enactment; ASQ-EE) and, separately, an interpretative and explanatory form of reading engagement (Integrative Comprehension; ASQ-IC). In general, Expressive Enactment predicts aesthetic (but not narrative explanatory) reading outcomes, while Integrative Comprehension predicts narrative explanatory (but not aesthetic) reading outcomes (Kuiken and Douglas, 2017, 2018; Kuiken et al., 2021). The present project is the first to examine this model in relation to reading outcomes that involve text-related moral outcomes. Also, rather than differentiating affective from cognitive empathy, the contrasting forms of social cognition that are subsumed by the ASQ-EE (Pre-Enactive Empathy) and ASQ-IC (Cognitive Perspective-Taking) separately contribute, on the one hand, to an expressive, explication-oriented form of reading engagement (ASQ-EE) and, on the other hand, to an explanatory, narrative-oriented form of reading engagement (ASQ-IC), respectively.

The process of expressive, explication-oriented reading (reflected by the ASQ-EE) involves a form of “egoic activity” (Husserl, 2001) through which new “categories” of lived experience are created in the dynamic back and forth and actively reflective explication (lifting out) of self-directed, pre-reflective sensed meanings, on the one hand, and pre-reflectively sensed textual meanings, on the other. In the general discussion, we will elaborate how this “egoic activity” is at the heart of existential reflection. In contrast, the process of absorbed reading that is reflected by the ASQ-IC lacks this kind of “egoic” expressive activity.

Form C of the Marlowe-Crown social desirability scale

Form C of the Marlowe-Crown Social Desirability Scale (SDS, Reynolds, 1982) involves 13-items and uses a true-false response format. This scale measures the degree to which participants provide socially desired rather than sincere responses.

Experimental and comparison texts

The experimental text in this study consisted of three selected passages from Richard Wagamese's novel Indian Horse (Wagamese, 2012). The novel presents a fictionalized, but realistic, portrayal of how the Residential Schools System has impacted and continues to impact the lives of Canadian Indigenous people. The first passage (53–54) powerfully describes the protagonist's and fellow Residential School children's feeling of being robbed of their freedom, as well as their feeling of suffocation from having their identity and culture taken away. In the second passage (167–169), the protagonist recalls the tragic story of two sisters, the younger of whom died after being repeatedly placed in solitary confinement by the nuns running the school, after which the older sister committed suicide at her sister's funeral. The third passage (198–199) portrays the painful memory of the protagonist's extended sexual abuse by one of the catholic Fathers running the school, who was also the protagonist's ice hockey coach. Besides potentially contributing to increased empathy for and understanding of some of the current struggles of the Indigenous population in Canada, the research materials also required participants to reflect on their own prejudices toward Indigenous people and out-groups in general.

As a comparison text we used the poem “The Red Wheelbarrow” by Williams (1966). Since the presumed effects of literary reading on social cognition, empathy, and prejudice are thought to hinge on absorption (transportation) into narratives, we chose a comparison text that completely lacks narrative structure and, moreover, does not make moral conduct thematic.

Procedure

We used a quasi-experimental design, namely, a crossover design in which interventions are performed sequentially (Handley et al., 2011). That is, participants in both groups read the comparison text and the experimental text but at different times and in a different order. This ensured that both groups received the benefits of the treatment.

Study session 1

All participants (Groups A & B) were given an oral briefing and invited to participate in the study. Since participants received partial course credit for participation (3 ™ 2% of their final grade, for a total of 6%) and since participation involved class specific educational benefits, 1 h and 15 min of class time were allocated to each study session. All study materials were presented on screen through a learning management system.

Participants who did not give consent were directed toward an alternative exercise, which required approximately the same amount of time to complete for the same partial course credit. Participants who gave consent were presented Davis's (1983) Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), Morrison et al.'s (2008) Prejudiced Attitudes Toward Aboriginals Scales (O-PATAS, M-PATAS), and Kuiken and Douglas's (2017) Absorption-Like-States Questionnaire (ASQ). The response format for these scales required a 5-point rating (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = do not know, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). Lastly, the first session also included Form C of the Marlowe-Crown Social Desirability Scale (Reynolds, 1982).

Study session 2

By the second session, which occurred 1 month after Session 1, Group B had finished reading Wagamese's (2012) Indian Horse (the experimental text) while Group A had not, and Group A had read the comparison text while Group B had not. Both groups completed Morrison et al.'s (2008) PATAS again and, in addition, Kuiken and Douglas's (2017) ASQ (in response to the presented text).

Study session 3

In the third session, which occurred 1 month after Session 2, Group A had finished reading the excerpts from Indian Horse and Group B had read the comparison text. Both groups then completed Morrison et al. (2008) O-PATAS and M-PATAS, as well as the ASQ. A written and oral debriefing were provided at the completion of Session 3.

Results

PATAS change scores

The research design involved (a) an initial baseline session (Session 1) during which both groups completed the M-PATAS and O-PATAS; (b) a second session (Session 2) in which Group A read the comparison text and Group B read the experimental text before completing the M-PATAS and O-PATAS; and (c) a third (cross-over) session (Session 3) in which Group B read the comparison text and Group A read the experimental text before completing the M-PATAS and O-PATAS. Thus, in this crossover design, both groups were exposed to the comparison text and to the experimental text shortly before completing the dependent measures.

We conducted two ANCOVAs in which (a) exposure to the comparison text vs. exposure to the experimental text was a between subjects variable; (b) order of exposure to the comparison and experimental texts was a between subjects variable; (c) baseline measures of the M-PATAS (or O-PATAS) was a covariate; and (d) post-intervention assessment of the M-PATAS (or O-PATAS) was a dependent variable. Using baseline minus post-treatment item averages, we found a significant text (comparison vs. experimental) by order (comparison text first vs. experimental text first) interaction for the M-PATAS, F(1, 54), = 8.889, p = 0.004. As expected, when statistically controlling for baseline M-PATAS scores, presentation of the experimental text was followed by significantly larger M-PATAS change scores (M = 3.038) than after presentation of the comparison text (M = 2.927). The analogous interaction for the O-PATAS change scores was not significant.

IRI and PATAS

We found no significant correlations between any of the dimensions of Davis's (1983) IRI and either of Morrison et al.'s (2008) PATAS change scores. This means that trait empathy, as measured by the IRI, did not affect changes in prejudiced attitudes toward the Canadian Indigenous population, as measured by the PATAS.

ASQ and PATAS

We also examined whether Pre-Enactive Empathy (a component of the ASQ-EE) or Cognitive Perspective-taking (a component of the ASQ-IC) would predict Morrison et al. (2008) PATAS change scores. We found a significant correlation between ASQ Pre-Enactive Empathy and the M-PATAS change scores, r(58) = 0.289; p = 0.028, but no relationship between ASQ Cognitive Perspective-Taking and M-PATAS change scores.

In an exploratory analysis, we also found that Pre-Enactive Empathy predicted a measure of Non-Utilitarian Respect: r(58) = 0.548; p < 0.001. However, Non-Utilitarian Respect and the M-PATAS change scores were not significantly correlated.

Discussion—Study 1

Results from Study 1 confirm previous evidence that reading narrative fiction can reduce prejudice. We also found a suggestive correlation between an expressive form of empathy (ASQ Pre-Enactive Empathy) and two forms of moral outcome: (a) reduction in the PATAS measure of old-fashioned prejudice and (b) an index of Non-Utilitarian Respect. These results motivated more careful examination of two issues.

First, it seems useful to examine more thoroughly the type of reading engagement that is required to capture the social cognitive nuances of literary reading. In particular, it seems useful to distinguish between (a) a form of engaged reading that involves Pre-Enactive Empathy as a single dimension among the three dimensions that constitute ASQ Expressive Enactment) and (b) a form of engaged reading that involves Cognitive Perspective-taking as a single dimension among the four dimensions that constitute ASQ Integrative Comprehension.

Second, it seems useful to reconsider the type of moral outcome that might follow engaged literary reading. Although Pre-Enactive Empathy (a component of the ASQ-EE) predicted both M-PATAS prejudice reduction and Non-Utilitarian Respect, these measures of moral outcome were not significantly correlated with each other. Moreover, given the previously demonstrated contrast between the expressive, aesthetic outcomes of the ASQ-EE and the explanatory, narrative outcomes of the ASQ-IC (Kuiken and Douglas, 2017, 2018; Kuiken et al., 2021), we thought it would be useful to determine whether these two forms of moral outcome are differentially related to ASQ-EE and ASQ-IC.

While well-suited to the pedagogical demands and restrictions of an in-class study, the outcome measure used in Study 1 (PATAS)—and the study design in general—may not be optimal. Although the classroom setting does provide a level of external validity that an experimental design does not, a more carefully constructed experimental setting might preclude the potential confounds (e.g., demand characteristics) that are difficult to control in the classroom. Also, while there may have been educational benefits to classroom opportunities for discussion, a more precise grasp of the processes involved in how contrasting forms of empathy mediate different forms of moral outcome may be possible within a controlled, experimental setting of the kind we employed in Studies 2 and 3.

Study 2

Building on the findings of Study 1, in Study 2, rather than comparing responses to different texts, we compared two forms of reading engagement, one that reflects an expressive and meaning-explicating form of engagement and another that reflects a resistance to expressive and explicative activity and an acquiescence to sedimented meaning categories, focusing instead on interpretation and explanation. Specifically, we examined the possibility that ASQ Expressive Enactment (ASQ-EE) and ASQ Integrative Comprehension (ASQ-IC) would differentially predict local and global moral outcomes. To that end, in this study we also examined two forms of moral change: (1) reduced racist attitudes (local moral change) and (2) non-utilitarian respect for others (global moral change). Racist attitudes, as measured in this study, are local in the sense that they involve prejudices grounded in a form of nativism, whereas non-utilitarian respect is global in the sense that it involves respect for human subjectivity in general. Our design enabled determination of whether the expressive, meaning explicating orientation of the ASQ-EE and the explanatory, narrative interpretive orientation of the ASQ-IC would differentially predict these global and local moral outcomes, respectively.

Materials and methods

Participants

Four hundred and fourteen undergraduate psychology students at MacEwan University, Canada, participated in this study for partial course credit. 16.5% were male (68 participants), 45.2% were female (187 participants), and 38.3% chose not to declare their gender (159 participants). Participants were 17–45 years old, with an average age of 21 years.

Materials

As in Study 1, participants completed Kuiken and Douglas's (2017) ASQ and Form C of the Marlowe-Crown Social Desirability Scale (SDS, Reynolds, 1982). The following measures were also included.

Zick's group-focused enmity index

Strong reactions to the racist wording of Morrison's PATAS in Study 1 and the fact that prejudiced attitudes toward one outgroup are strongly correlated with prejudices toward other outgroups (Allport, 1954; Adorno et al., 1993) prompted replacement of the PATAS with a more generalized measure of racist attitudes, namely Zick et al.'s (2011) eleven-item Group-Focused Enmity Index (GFE). Five of its 11 items target racist attitudes directly (e.g., “Some cultures are clearly superior to others;” GFE Racism subscale), and six of the items target tacitly racist anti-immigrant attitudes (e.g., “There are too many immigrants in Canada;” GFE AIA subscale). We obtained pre- and post-test measures of these two forms of prejudice. Like Morrison's PATAS, Zick et al.'s GFE distinguishes between old-fashioned prejudice and modern prejudice (Tougas et al., 1995; Madon et al., 2001). That is, it measures attitudes toward the perceived inferiority of outgroups based on genetic race differences (old-fashioned prejudice), as well as more subtle (but also more widespread) convictions that certain out-groups are no longer discriminated against, that they are too demanding and too proud of their cultural heritage, or that they receive special treatment (modern prejudice).

Kuiken's experiencing questionnaire

Whereas, the ASQ reliably distinguishes two forms of reading engagement, Kuiken et al.'s (2012) Experiencing Questionnaire (EQ) assesses several aesthetic reading outcomes. Of particular relevance here, the EQ includes a scale that assesses a global form of moral understanding called Non-Utilitarian Respect. The EQ was administered as a post-test only.

Response text

Participants in Study 2 read and responded to the same three passages from Richard Wagamese's novel Indian Horse (Wagamese, 2012) that were employed in Study 1.

Procedure

To establish baseline measures of prejudiced attitudes toward outgroups, Zick et al.'s (2011) GFE was administered during mass testing to all introductory-level psychology students at MacEwan University, Canada. Participants subsequently registered for the present study through the university's research pool administration portal. Participants read the three excerpts from the novel Indian Horse and then completed questionnaires that assessed prejudicial attitudes, reading engagement, and global moral judgement. Specifically, they first completed Kuiken and Douglas's (2017) ASQ, followed by Kuiken et al.'s (2012) EQ, and finally Zick et al.'s (2011) GFE.

Results

Using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), we examined two paths that have been identified in prior research (Kuiken and Douglas, 2017, 2018; Kuiken et al., 2021): (1) one leading from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension and from there to explanatory narrative outcomes (including narratively induced changes in local prejudicial attitudes, i.e., GFE Racism scores), and (2) another leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment and from there to expressive aesthetic outcomes (including an expressively induced shift toward global non-utilitarian respect for others).

As in the model presented in Figure 1, the path leading from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension positively predicted GFE Racism change scores (β = 0.38, p < 0.007). In contrast, the path leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment negatively predicted GFE Racism change scores (β = −0.46, p = 0.002). In sum, the full ASQ model including Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension positively predicted local changes in prejudice, while the path leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment negatively predicted local prejudice reduction. This asymmetry was evident for GFE Racism change scores but not for GFE AIA change scores.

On the other hand, when the outcome measure was Non-Utilitarian Respect, both the path leading from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension and the path leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment positively predicted that global moral outcome (Integrative Comprehension: β = 0.24, p = 0.015; Expressive Enactment: β = 0.32, p = 0.002, respectively). In sum, while the path leading from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension positively predicted local changes in prejudicial attitudes, both the path leading from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension and the path leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment positively predicted global changes in non-utilitarian respect.

Results for the path leading from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension are consistent with the relation between ASQ Pre-Enactive Empathy and changes in local prejudicial attitudes observed in Study 1. However, results for the path leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment suggest that, in this study, expressive explication actually impeded local attitude change, while results for the path leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment suggest that expressive explication facilitated global changes in non-utilitarian respect.

Discussion

Our results suggest that local moral attitude change (e.g., GFE Racism) is facilitated by an interpretive form of narrative reading engagement (Integrative Comprehension; ASQ-IC) and that local moral attitude change may actually be impeded by an expressive form of meaning-explicating reading engagement (Expressive Enactment; ASQ-EE). Also, these results suggest that a global form of moral understanding (e.g., Non-Utilitarian Respect) is facilitated by Expressive Enactment (ASQ-EE), although that form of global moral understanding is also predicted by Integrative Comprehension (ASQ-IC). These relations are complicated also by the fact that we only used a post-test measure of Non-Utilitarian Respect. Nonetheless, the present results suggest that differentiation between an interpretive, explanatory form of narrative reading engagement and an expressive, meaning-explicating form of reading engagement may clarify how literary reading influences moral change. Clearly, however, these results required replication.

Study 3

In Study 2, we found that when (a) an expressive form of empathy-like cognition is included within an overall model of Expressive Enactment and (b) an explanatory form of cognitive perspective-taking is included within an overall model of Integrative Comprehension, these two forms of reading engagement differentially predict local text-congruent attitude change and global non-utilitarian respect. To examine whether this pattern is replicable and generalizable, we conducted a third study in which we applied the methods and procedures from Study 2 to a different literary text. Besides replication, our goal was to determine whether local prejudice reduction and global non-utilitarian respect are differentially mediated by these two forms of reading engagement when racial prejudice is not thematic in the text.

Materials and methods

Participants

Two hundred and forty-four undergraduate psychology students at MacEwan University, Canada, participated in this study for partial course credit. Due to a technical error during mass testing, we have demographic statistics for only a subset of 74 participants and, also, we were not able to calculate change scores (using pre- and post-test measures of moral change). However, based on the similarity of this subset to participants in Study 2 (same average age of 21 years, similar age range and gender distribution), we have determined that our sample is roughly comparable to that of Study 2.

Materials

Questionnaires

As in Study 2, we employed Zick et al.'s (2011) eleven-item Group-Focused Enmity Index (GFE), Kuiken and Douglas (2017) thirty-seven-item ASQ, and Kuiken et al. forty-one-item EQ.

Response text

Participants read a 2,713-word excerpt from On Chesil Beach, the short novel by McEwan (2007) that thematizes, among other things, the inter- and intrapersonal consequences of the unwillingness or inability to humbly work toward meaningful marital relationships. This text was chosen for several reasons. First, it shares with the text used in Studies 1 and 2 (Indian Horse) a concern with moral conduct and with the complex subjectivity of narrative personae. Second, in contrast to Indian Horse, On Chesil Beach does not specifically thematize prejudice toward outgroups. Thus, employment of this text—and comparison with results from Study 2—enabled us to analyse whether ASQ-EE and ASQ-IC differentially predict the moral outcomes we observed in that study.

Procedure

As in Study 2, participants registered for the present study through MacEwan University's research pool administration portal. They read the excerpt from the short novel On Chesil Beach and then completed the task and questionnaires that assessed prejudicial attitudes, reading engagement, and global moral judgement. Specifically, they first completed Kuiken and Douglas's (2017) ASQ, followed by Kuiken et al.'s (2012) EQ, and finally Zick et al.'s (2011) GFE. No GFE pre-test scores were collected in this study.

Results

As in Study 2, we examined two SEM causal paths: (1) one leading from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension and from there to explanatory narrative outcomes (including narratively induced changes in local prejudicial attitudes, i.e., GFC Racism scores), and (2) another leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment and from there to expressive aesthetic outcomes (including an expressively induced shift toward global non-utilitarian respect).

As in Study 2, the path leading from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension positively predicted GFE Racism change scores (β = 0.41, p = 0.006). Also as in Study 2, the path leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment negatively predicted GFE Racism change scores (β = −0.43, p = 0.004). In sum, the full ASQ model including the path from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension positively predicted local changes in prejudice, while the path leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment negatively predicted local prejudice reduction. As in Study 2, this asymmetry was evident for GFE Racism change scores but not for GFE AIA change scores.

On the other hand, when the outcome measure was Non-Utilitarian Respect, the path leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment positively predicted that global moral outcome (β = 0.53, p < 0.001). However, unlike in Study 2, the path leading from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension did not reliably predict Non-Utilitarian Respect (β = 0.09, ns). In short, while the path leading from Open Reflection to Expressive Enactment indicated facilitation of global changes in non-utilitarian respect, the path leading from Open Reflection to Integrative Comprehension did not significantly influence non-utilitarian respect.

Discussion

As in Study 2, these results indicate that local moral attitudes, particularly racist ones, are reduced by a form of reading engagement that is interpretive and oriented toward narrative explanation (Integrative Comprehension; ASQ-IC). In addition, we replicated evidence that, perhaps ironically, this same local form of moral change is impeded by openly reflective Expressive Enactment.

In addition, we replicated evidence that openly reflective Expressive Enactment (but perhaps not Integrative Comprehension) facilitates global respect for human subjectivity. In sum, the present results substantiate not only the distinction between Expressive Enactment and Integrative Comprehension but also the distinction between the local and global forms of moral change that may be outcomes of deeply engaged literary reading.

General discussion

The results replicated across Studies 2 and 3 are 2-fold. First, in both studies, ASQ-EE, but not ASQ-IC, impeded text-related reductions in prejudice. One possibility is that ASQ-IC is marked by acquiescence to sedimented understandings of prejudice (or of the lack of prejudice). Another possibility is that the ASQ-IC is marked by the predisposition to turn quickly to causal explanation of narrative events and, in doing so, bypass the process of expressive explication (Kuiken and Douglas, 2017).

Second, in both studies, Expressive Enactment facilitated (global) non-utilitarian respect. It is our contention that, consistent with results from studies by Kuiken and Douglas (2018) and Kuiken et al. (2021), ASQ-EE distinctively predicts the kind of expressive explication that deepens this global form of human understanding.

The phenomenology of literary reading

To understand how Expressive Enactment overcomes resistance to expressive explication and supports non-utilitarian respect may require elaboration of the phenomenology of expressive, meaning-explicating literary reading. Further, elaboration of the phenomenology of expressive—and almost certainly aesthetic—literary reading may clarify relations between the moral import of literary reading and existential philosophy.

As indicated in the introduction, there is a tradition in literary studies and more recently in the empirical study of literature that situates literariness in the interaction of reader and text. The overarching proposal is that defamiliarizing linguistic structures elicit perceptual, physiological, or behavioral effects. While support for some of these effects is available (e.g., Hakemulder, 2004, 2020; van Peer, 2007; Jacobs, 2015), we have distinguished these from a distinctly aesthetic engagement with literature, which is characterized by what the phenomenologist Edmund Husserl has termed “egoic acts” and “awakenings” (Husserl, 2001) and expressive explication of affective resonances (i.e., lifting out the felt sense of metaphoric resonances; Kuiken and Sopcak, 2021; Sopcak and Kuiken, 2022). Husserl, in turn, is part of a tradition in philosophy that dates back to Heraclitus and more recently Descartes2 within which emphasis is placed on the importance of reflection that goes beyond passive recognition of reified (sedimented) categorial objects, and instead toward expression of lived experience.

The proposal, in brief, follows Husserl (2001) in his suggestion that our default engagement in the world occurs in a mode of habituality (“natural attitude”) involving abstract recognition of sedimented meaning categories and passivity of the self (Husserl's “ego”). In this habitual process of perception and cognition “the ego … is ‘in a stupor' in the broadest sense, and … no lived-experience in the specific sense of wakefulness is there at all and no present ego is there at all as its subject” (17). He refers to this passivity as a kind of “self-forgetfulness” (28) that undermines our freedom and stands in the way of our seeing “the true, the genuine,” (Husserl, 2001: 28). In Husserl translator Steinbock's (2001) words: “If we were to live only in passivity, contends Husserl, and if it were not possible for us to carry out free activity, we would be blind to the sphere of true being” (lviii).

Free activity and thinking “in the true sense” occur when affective resonances exert a strong enough pull to elicit an egoic turning toward and tending to these resonances and when the intentional object thus becomes thematic. This “sense-constituting lived-experience” (Husserl, 2001: 13) and “sense-giving thinking” (27) involves an active ego expressively explicating the lived experience. Important to note here is the connection Husserl makes between an expressively active ego and freedom.

Gallagher's (2012) discussion of sense of agency will help clarify and provide context for the notoriously ambiguous terms ego and freedom. At a first level, he distinguishes the sense of ownership (I am the one undergoing an action, whether voluntarily or not) from the sense of agency (“I am the one who is causing or generating the action;” 18). The sense of ownership, he contends, is experienced pre- or non-reflectively, “which means they [experiences of sense of ownership] neither are equivalent to nor depend on the subject taking an introspective reflective attitude, nor that the subject engages in an explicit perceptual monitoring of bodily movements” (18). The sense of agency, in contrast, involves the experience of being the author or cause of a certain action (including the action of reflecting on something). However, this can be a first-order, embodied, pre-reflective sense of agency, which Gallagher (2012) refers to as “SA(1),” or it can be of a second-order, adding “prior deliberation or occurrent metacognitive monitoring,” which he refers to as “SA2” (26). Finally, as a special case of a reflective sense of agency, he adds the “long-term sense of one's capacity for action over time” (29), which involves sense of one's past, present, and future actions “are given a general coherence and unified through a set of overarching goals, motivations, projects and general lines of conduct” (Pacherie, 2007, as quoted in Gallagher, 2012: 29).

Husserl (2001) “egoic acts” and “egoic awakenings” involve precisely the kind of higher-order, reflective sense of agency that Gallagher refers to as SA(2) (and which involve actively reflective explication of pre-reflective senses of ownership and agency). Moreover, we argue that this type of sense of agency vis a vis one's actions in/over time is at the heart of Husserl's notion of freedom as well as that of existentialists influenced by him, such as Sartre and de Beauvoir.

Building on Mukarovsky (1964), Shklovsky and Berlina (2017), and others, we have proposed that (and how) literature can, for some, set in motion the distinctly aesthetic form of reading engagement that Expressive Enactment (ASQ-EE) captures and that brings Husserl's (2001) active ego and Gallagher (2012) higher-order sense of agency onto the scene (Kuiken and Sopcak, 2021; Sopcak and Kuiken, 2022). In fact, the actively expressive explication characteristic of Expressive Enactment (ASQ-EE) has this reflective sense of agency at its core and is related to the existential-phenomenological notion of freedom as the ability and responsibility to actively and expressively explicate and act upon “sense-constituting lived-experience” (Husserl, 2001: 13).

The contrasting “self-forgetfulness” that Husserl refers to in his discussion of the natural attitude and passivity in perception and consciousness is characterized by the lack of a higher-order, explicitly expressive and reflective sense of agency (Gallagher, 2012) and closely related to existentialists' proposals that human existence requires an ongoing and persistent resistance against this “inner negation” (Sartre, 1966: 48). Existentialists, beginning with Kierkegaard (2004), considered the human self to be an accomplishment that needs to be constantly willed and won by the active ego [Gallagher, 2012 higher-order sense of agency, SA(2)] expressively explicating its lived experience. For instance, the “father of existentialism” Kierkegaard (2004), has precisely this active and expressive egoic sense-constituting thinking in mind when he defines a self as a “relation relating itself to itself” (43). And he describes in detail how human existence may ignore and deny this self by unnoticeably sliding into passivity, or by actively resisting the perpetual task of becoming a self, that is by resisting the sense of higher-order reflective agency Gallagher (2012) termed SA(2). Kierkegaard writes: “The biggest danger, that of losing oneself, can pass off in the world as quietly as if it were nothing” (62–63). Following in the footsteps of Socrates as the “midwife of truth,” Kierkegaard considered his texts to be maieutic in the sense that they helped birth the self [Kierkegaard et al.'s (1998): 495], by evoking Gallagher (2012) higher-order, reflective sense of agency and Husserl's (2001) active ego.

Similarly, Sartre (1966) describes this form of self-denial/denial of agency as “bad faith” (mauvaise fois) and argues that it involves fleeing one's freedom and the responsibility it entails: “Thus the refusal of freedom can be conceived only as an attempt to apprehend oneself as being-in-itself [static, passive, being without agency] … Human reality may be defined as a being such that in its being its freedom is at stake because human reality perpetually tries to refuse to recognize its freedom” (440). That is, bad faith is characterized by the denial of agency and the absence of an active ego expressively explicating its lived experience. Conversely, according to Sartre (1966), human existence is “identical with” (443) and founded by the freedom (and the curse of having) to “choose oneself” (441) through what Husserl termed “sense-constituting lived-experience” (Husserl, 2001: 13): “And this thrust is an existence; it has nothing to do with an essence or with a property of being which would be engendered conjointly with an idea. Thus, since freedom is identical with my existence, it is the foundation of ends which I shall attempt to attain” (Sartre, 1966: 444; our italics). In sum, from this existential-phenomenological perspective the “sense-giving thinking” (Husserl, 2001: 27) that involves an active ego (higher-order sense of agency) expressively explicating its lived experience (as captured by Expressive Enactment) is existential reflection in the sense that it is at the heart of “choosing oneself” and exercising the freedom that Sartre equates with human Being. It brings existence into experience.

In literary theory, this relationship between existential reflection and Expressive Enactment was aptly captured by Shklovsky and Berlina (2017): “What do we do in art? We resuscitate life. Man is so busy with life that he forgets to live it. He always says: tomorrow, tomorrow. And that's the real death. So what is art's great achievement? Life. A life that can be seen, felt, lived tangibly” (62).

Expressive enactment, existential reflection, and morality

Although seeds of an existentialist ethics can be found in earlier existentialist's writings such as Kierkegaard's and Nietzsche's, it is Sartre's partner, Simone de Beauvoir who sets out to explicitly develop this connection in her book The Ethics of Ambiguity (De Beauvoir, 1976). She writes:

“However, it must not be forgotten that there is a concrete bond between freedom and existence; to will man free is to will there to be being, it is to will the disclosure of being in the joy of existence; in order for the idea of liberation to have a concrete meaning, the joy of existence must be asserted in each one, at every instant; the movement toward freedom assumes its real, flesh and blood figure in the world by thickening into pleasure, into happiness… If we do not love life on our own account and through others, it is futile to seek to justify it in any way” (135–136).

Important to remember in this context is the existential-phenomenological notion of freedom as involving a higher-order, reflective sense of agency and the ability and responsibility to actively and expressively explicate and act upon “sense-constituting lived-experience” (Husserl, 2001: 13). Like other existentialists and phenomenologists before her, de Beauvoir considers the pursuit of this particular kind of freedom to be a moral imperative, the foundation of any other moral considerations, and an end in itself. She also makes it clear that this imperative applies not only to oneself (as Nietzsche might have it) but to all human beings. To de Beauvoir our “freedom wills itself genuinely only by willing itself as an indefinite movement through the freedom of others” (90).

This willing of the freedom of others is captured by our non-utilitarian human respect scale from the Experiencing Questionnaire (EQ-NUR; item example: “While reading this story, it seemed wrong to treat people like objects”), which we have used as a measure of a form of global moral reflection, as opposed to one that is local and narrow.

In contrast, we saw that moral attitude changes that were local in nature were associated with a form of absorbed reading engagement involving a resistance to expressive and explicative activity and an acquiescence to sedimented meaning categories, focusing instead on interpretation and explanation (Integrative Comprehension; ASQ-IC). These outcomes and this kind of reflection are what scholars have been referring to in studies of the persuasive effects of literary reading. To de Beauvoir, this is a bad faith ethics, not worthy of its name: “What must be done, practically? Which action is good? Which is bad? To ask such a question is also to fall into a naïve abstraction… Ethics does not furnish recipes any more than science and art. One can merely propose methods…” (De Beauvoir, 1976: 134). And she argues that “the finished rationalization of the real,” which is the mode of encountering the world in the natural attitude (passive, abstract recognition of pre-established meanings and patterns of causal inference) “would leave no room for ethics” (129).

The fact that the form of reading engagement that is actively expressive and explicative (Expressive Enactment; ASQ-EE) repeatedly impeded changes in local prejudiced attitudes may find an explanation within the framework of such an existentialist ethics. As discussed, this form of reading engagement involves a form of agency and existential outcomes that run counter to the denial of agency and absence of an active ego expressively explicating its lived experience that is characteristic of what Sartre (1966) terms bad faith. It also resists what De Beauvoir (1976) refers to as “the finished realization of the real” (129), which undermines a sincere ethics as a method. In fact, the type of reflective activity it involves is more akin to Nussbaum's (2001) description of Sophoclean reflection. Referring to Antigone, she writes:

The lyrics both show us and engender in us a process of reflection and (self)-discovery that works through a persistent attention to and a (re)-interpretation of concrete words, images, incidents. We reflect on an incident not by subsuming it under a general rule, not by assimilating its features to the terms of an elegant scientific procedure, but by burrowing down into the depths of the particular …The Sophoclean soul is more like Heraclitus's image of psuche: a spider sitting in the middle of its web…It advances its understanding of life and of itself not by a Platonic movement from the particular to the universal, from the perceived world to a simpler, clearer world, but by hovering in thought and imagination around the enigmatic complexities of the seen particular … (Nussbaum, 2001, p. 69).

These complexities involve paradox and ambiguity, perhaps even unwelcome and socially unacceptable views. In the context of our findings, the reliable prediction of impeded change in local prejudiced attitudes by Expressive Enactment may be attributed to the fact that a sincere expression of one's “enigmatic complexities,” must necessarily involve reflection on and explication of one's contradictory and perhaps at times unsavory attitudes.

In sum, the findings of our studies support the existential-phenomenological view that (global) moral reflection is a method that involves an active ego (higher-order [sense of] agency) expressively explicating its lived experience, rather than passive reflection on abstract moral laws, causal laws, or acquiescence to sedimented meaning categories. It is precisely this kind of reflection, we believe, that Hannah Arendt had in mind in her following observation on the “banality of evil:” “Could the activity of [sense-giving] thinking as such, the habit of examining and reflecting upon whatever happens to come to pass, regardless of specific content and quite independent of results, could this activity be of such a nature that it ‘conditions' men against evildoing?” (Arendt, 1977: 5).

Existential reading and psychological wellbeing

In this final section, we will show that the awakening of Husserl's (2001) active ego (Gallagher, 2012 higher-order sense of agency) that expressively explicates its lived experience, and which we have shown to be involved during the distinctly aesthetic form of reading engagement captured by Expressive Enactment (ASQ-EE), as well as its existential and moral outcomes, have been associated with beneficial health effects within existential psychotherapy (e.g., Yalom, 1980) and the burgeoning field of existential positive psychology (Wong, 2012; Bretherton, 2015; Robbins, 2021; Wong et al., 2021). What on the surface may seem like an unlikely union between existentialism (existential psychotherapies) and positive psychology, which Wong et al. (2021) refer to as positive psychology 2.0 (PP2.0), places emphasis on the importance of grappling with existential issues and anxiety for human flourishing. Rather than considering, say, a sense of meaninglessness in an indifferent universe or the struggle with existence or difficulty in locating a sense of self, by default as psychological disorders, PP2.0 considers them foremost as spiritual or philosophical ailments that can serve as catalysts for human flourishing.

Robbins (2021) differentiates PP2.0 from what he perceives as traditional positive psychology's view of human flourishing that overemphasizes hedonic happiness as follows: “In contrast, existential and spiritual traditions have stressed a vision of the good life as a refusal to avoid negative experiences, since the suppression of life's tragic dimensions, or “anesthetic consciousness,” can itself foster varieties of pathologies and dampen the vitality of life” (2). He further criticizes the relative absence of “the moral or ethical dimensions of human flourishing” in traditional positive psychology and proposes the concept of the “joyful life” [as a] potential bridge between positive psychology and conceptions of the good life found in existential, humanistic, and spiritual perspectives on the good life” (2).

In the passage from De Beauvoir's (1976) Ambiguity of Ethics, quoted above, we found the intertwining between freedom and existence in “the will to disclose being in joyful existence” (135) and that “freedom wills itself genuinely only by willing itself as an indefinite movement through the freedom of others” (90). By drawing on Husserl (2001) we argued that at the core of this freedom, joyful existence, and disclosing of being lies an active ego (higher-order, reflective sense of agency) that expressively explicates its lived experience.

Studies of joy in the PP2 community have also found that this form of joy, among other things, has a “tendency to emerge as a response to a solicitation from something larger than ourselves—into communion with others and a deeper, more engaged life” (Robbins, 2021: 2). This is reminiscent of the global moral outcomes that were consistently associated with the form of reading engagement captured by Expressive Enactment and that we measured with the non-utilitarian respect subscale of the Experiencing Questionnaire (e.g., While reading this story, it seemed wrong to treat people like objects; …I felt deep respect for humanity).

This aligns with existential-phenomenological and existential positive psychology's conceptions of the good life as involving mainly eudaimonic and chaironic “happiness,” and a “meaning orientation” to human flourishing (Wong, 2012; Robbins, 2021). More specifically, Robbins (2021) cites extensive empirical research associating this form of existential joy to indicators of wellbeing, such as psychological wellbeing, psychological need satisfaction and self-actualization, resilience and hardiness, and mindfulness (Robbins, 2021: 6–10).

Clearly, although the series of studies we presented in this paper and the existential-phenomenological orientation of the measures we employed enabled us to draw intriguing parallels to existential positive psychology, more targeted studies are necessary to substantiate these connections. However, a key takeaway in the context of this special issue “Existential Narratives: Increasing Psychological Wellbeing Through Story” may be not to overlook differences in reading engagement, since we found existential reflection and outcomes consistently associated with the distinctly aesthetic form of reading engagement captured by Expressive Enactment.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by MacEwan University's Research Ethics Board. The patients/participants provided their active informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

MacEwan University's Faculty Development Fund covered the open access publication fees for this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The term “Aboriginal” to refer to the Canadian Indigenous population is no longer in use. We retain it when referring to the Prejudiced Attitudes Toward Aboriginals Scale, but use “Indigenous” when referring to the population.

2. ^Wheeler (2005) has pointed out that the widespread anti-Cartesianism in some corners of cognitive science often operates on “received interpretations of Descartes' view that, when examined closely, reveal themselves to be caricatures of the position that Descartes himself actually occupied” (15).

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., and Levinson, D. J. (1993). The Authoritarian Personality. Abridged ed. New York, NY: Norton.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. The Nature of Prejudice. Oxford, England: Addison-Wesley.

Arendt, H. (1977). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report of the Banality of Evil. Rev. and Enlarged ed. New York, NY; London Victoria…[etc.]: Penguin books.

Bal, P. M., and Veltkamp, M. (2013). “How does fiction reading influence empathy? An experimental investigation on the role of emotional transportation.” Edited by L. Young. PLoS ONE 8, e55341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055341

Batson, C. D., Early, S., and Salvarani, G. (1997). Perspective taking: imagining how another feels versus imaging how you would feel. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 23, 751–758. doi: 10.1177/0146167297237008

Bretherton, R. (2015). “Existential dimensions of positive psychology.” In Positive Psychology in Practice, ed S. Joseph (Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 47–60. doi: 10.1002/9781118996874.ch4

Busselle, R., and Bilandzic, H. (2009). Measuring Narrative Engagement. Media Psychol. 12, 321–347. doi: 10.1080/15213260903287259

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 44, 113–126. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

Dodell-Feder, D., and Tamir, D. I. (2018). Fiction reading has a small positive impact on social cognition: a meta-analysis. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen/ 147, 1713–1727. doi: 10.1037/xge0000395

Gallagher, S. (2012). Multiple aspects in the sense of agency. New Ideas Psychol. 30, 15–31. doi: 10.1016/j.newideapsych.2010.03.003

Gerrig, R. J. (1993). Experiencing Narrative Worlds: On the Psychological Activities of Reading. Book, Whole. New Haven, CT: Yale UP.

Green, M. C. (2002). “In the mind's eye: transportation-imagery model of narrative persuasion,” in Narrative Impact: Social and Cognitive Foundations (Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 315–341.

Green, M. C. (2005). “Transportation into narrative worlds: implications for the self,” in On Building, Defending and Regulating the Self: A Psychological Perspective (New York, NY, US: Psychology Press), 53–75.

Green, M. C., and Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 701–721. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Hakemulder, F. (2020). Finding meaning through literature. Anglistik 31, 91–110. doi: 10.33675/ANGL/2020/1/8

Hakemulder, J. F. (2004). Foregrounding and its effect on readers' perception. Discourse Processes 38, 193–218. doi: 10.1207/s15326950dp3802_3

Handley, M. A., Schillinger, D., and Shiboski, S. (2011). Quasi-experimental designs in practice-based research settings: design and implementation considerations. J. Am. Board Family Med. 24, 589–596. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110067

Healey, M. L., and Grossman, M. (2018). Cognitive and affective perspective-taking: evidence for shared and dissociable anatomical substrates. Front. Neurol. 9, 491. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00491

Husserl, E. (2001). Analyses Concerning Passive and Active Synthesis: Lectures on Transcendental Logic. Amsterdam: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-94-010-0846-4

Jacobs, A. M. (2015). Neurocognitive poetics: methods and models for investigating the neuronal and cognitive-affective bases of literature reception. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 186. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00186

Johnson, D. R. (2012). Transportation into a story increases empathy, prosocial behavior, and perceptual bias toward fearful expressions. Pers. Individ. Differ. 52, 150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.005

Johnson, D. R. (2013). Transportation into literary fiction reduces prejudice against and increases empathy for arab-muslims. Sci. Study Literat. 3, 77–92. doi: 10.1075/ssol.3.1.08joh

Kierkegaard, S. (2004). The Sickness unto Death: A Christian Psychological Exposition for Edification and Awakening. Penguin Classics. London, England; New York, NY, USA: Penguin Books.

Kierkegaard, S., Hong, H. V., Hong, E. H., and Kierkegaard, S. (1998). The Point of View. Kierkegaard's Writings 22. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400832408

Kuijpers, M. M., Douglas, S., and Bálint, K. (2021). “Narrative absorption: an overview,” in Handbook of Empirical Literary Studies, eds D. Kuiken and A. M. Jacobs (Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter), 279–304. doi: 10.1515/9783110645958-012

Kuiken, D., Campbell, P., and Sopčák, P. (2012). The experiencing questionnaire: locating exceptional reading moments. Sci Study Literat. 2, 243–272. doi: 10.1075/ssol.2.2.04kui

Kuiken, D., Carey, R., and Nielsen, T. (1987). Moments of affective insight: their phenomenology and relations to selected individual differences. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 6, 341–364. doi: 10.2190/80PQ-65EP-PQGD-1WK9

Kuiken, D., D. Miall, S., and Sikora, S. (2004). Forms of self-implication in literary reading. Poetics Today 25, 171–203. doi: 10.1215/03335372-25-2-171

Kuiken, D., and Douglas, S. (2017). “Forms of absorption that facilitate the aesthetic and explanatory effects of literary reading,” in Narrative Absorption, eds F. Hakemulder, M. M. Kuijpers, E. S. Tan, K. Bálint, and M. M. Doicaru, Vol. 27 (Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins), 219–252.

Kuiken, D., and Douglas, S. (2018). Living metaphor as the site of bidirectional literary engagement. Sci. Study Literat, 8, 47–76. doi: 10.1075/ssol.18004.kui

Kuiken, D., Douglas, S., and Kuijpers, M. (2021). Openness to experience, absorption-like states, and the aesthetic, explanatory, and pragmatic effects of literary reading. Sci. Study Literat. 11, 148–195. doi: 10.1075/ssol.21007.kui

Kuiken, D., and Sikora, S. (1993). “The impact of dreams on waking thoughts and feelings,” in The Functions of Dreaming, eds A. Moffitt, M. Kramer, and R. Hoffmann (Albany: State University of New York Press), 419–476.

Kuiken, D., and Sopcak, P. (2021). “Openness, reflective engagement, and self-altering literary reading,” in Handbook of Empirical Literary Studies, eds D. Kuiken and A. M. Jacobs (Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter), 305–342. doi: 10.1515/9783110645958-013

Madon, S., Guyll, M., Aboufadel, K., Montiel, E., Smith, A., Palumbo, P., et al. (2001). Ethnic and national stereotypes: the princeton trilogy revisited and revised. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 27, 996–1010. doi: 10.1177/0146167201278007

Mar, R. A. (2018). Evaluating whether stories can promote social cognition: introducing the social processes and content entrained by narrative (SPaCEN) framework. Discourse Processes 55, 454–479. doi: 10.1080/0163853X.2018.1448209

Melchers, M., Li, M., Chen, Y., Zhang, W., and Montag, C. (2015). Low empathy is associated with problematic use of the internet: empirical evidence from China and Germany. Asian J. Psychiatry 17, 56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2015.06.019

Morrison, M. A., Morrison, T. G., Harriman, R. L., and Jewell, L. M. (2008). “Old-fashioned and modern prejudice toward Aboriginals in Canada.” In The Psychology of Modern Prejudice, eds M. A. Morrison, and T. G. Morrison (New York, NY: Nova Science), 277–305.

Mukarovsky, J. (1964). “Standard language and poetic language,” in Prague School Reader on Aesthetics, Literary Structure, and Style, ed P. L. Garvin (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press), 17–30.

Mumper, M. L., and Gerrig, R. J. (2017). Leisure reading and social cognition: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 11, 109–120. doi: 10.1037/aca0000089

Nell, V. (1988). Lost in a Book: The Psychology of Reading for Pleasure. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2001). The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511817915

Pacherie, E. (2007). The sense of control and the sense of agency. Psyche Interdiscipl. J. Res. Consciousness 13, 1–30.

Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 38, 119–125.

Robbins, B. D. (2021). The joyful life: an existential-humanistic approach to positive psychology in the time of a pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12, 648600. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648600

Sartre, J.-P. (1966). Being and Nothingness: An Essay in Phenomenological Ontology. New York, NY: Pocket Books.

Shklovsky, V., and Berlina, A. (2017). Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc.

Sikora, S., Kuiken, D., and Miall, D. S. (2011). Expressive reading: a phenomenological study of readers' experience of coleridge's the rime of the ancient mariner. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 5, 258–268. doi: 10.1037/a0021999

Sopcak, P., and Kuiken, D. (2022). The affective allure - a phenomenological dialogue with David Miall's studies of foregrounding and feeling. J. Literar. Seman. 51, 75–91. doi: 10.1515/jls-2022-2053

Steinbock, A. J. (2001). “Introduction.” Analyses Concerning Passive and Active Syntheses: Lectures on Transcendental Logic. By E. Husserl. Trans. A. Steinbock. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publisher.

Tougas, F., Brown, R., Beaton, A. M., and Joly, S. (1995). Neosexism: plus Ça change, plus C'est Pareil. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 21, 842–849. doi: 10.1177/0146167295218007

van Laer, T., de Ruyter, K., Visconti, L. M., and Wetzels, M. (2014). The extended transportation-imagery model: a meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of consumers' narrative transportation. J. Consumer Res. 40, 797–817. doi: 10.1086/673383

van Peer, W. (2007). Introduction to foregrounding: A state of the art. Lang. Literat. Int. J. 16, 99–104. doi: 10.1177/0963947007075978

Wheeler, M. (2005). Reconstructing the Cognitive World: The Next Step. Cambridge, MA; London: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/5824.001.0001

Williams, W. C. (1966). The Collected Earlier Poems of William Carlos Williams. A New Directions Book. New York, NY: New Directions.

Wong, P. T. P., Mayer, C.-H., and Arslan, G. (2021). Editorial: COVID-19 and existential positive psychology (PP2.0): the new science of self-transcendence. Front. Psychol. 12, 800308. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800308

Wong, P. T. P., ed. (2012). The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications, 2nd Edn. Personality and Clinical Psychology Series. New York, NY: Routledge.

Keywords: literary reading, empathy, prejudice, existential reflection, phenomenology, morality, agency, expression

Citation: Sopcak P, Kuiken D and Douglas S (2022) Existential reflection and morality. Front. Commun. 7:991774. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.991774

Received: 11 July 2022; Accepted: 16 September 2022;

Published: 18 October 2022.

Edited by:

Enny Das, Radboud University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Roel Willems, Radboud University, NetherlandsMassimo Salgaro, University of Verona, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Sopcak, Kuiken and Douglas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paul Sopcak, sopcakp@macewan.ca

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Paul Sopcak

Paul Sopcak Don Kuiken

Don Kuiken Shawn Douglas

Shawn Douglas