Abstract

Objectives:

Surgical myocardial revascularization shows impaired outcomes in women compared to men. Investigation of gender related outcome differences comprises of different operative strategies potentially hampering interpretation of data. We herein aimed to investigate gender related outcome differences in off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCAB) only.

Methods:

Between 2016 and 2021, 1,075 consecutive patients underwent OPCAB at our center. Of those 880/1,075 were male (81.9%) and 195/1,075 were female (18.1%). Kaplan–Meier analysis was used for investigating differences in survival probabilities. Identification of risk factors was conducted by logistic regression.

Results:

Male patients showed a higher rate of reduced LVEF < 35% (88/880, 10% vs. 9/195, 4.61%; p = 0.025) and impaired renal function (creatinine: 1.17 ± 0.76 vs. 1.03 ± 0.59; p = 0.016). In female patients less utilization of both internal mammary arteries was documented (502/880, 57.04% vs. 74/195, 37.94%; p < 0.001). Procedure time (256.13 min vs. 238.02 min; p < 0.001) and number of distal anastomoses (2.40 ± 0.83 vs. 2.11 ± 0.82; p < 0.001) were lower in female patients. 30-day mortality (16/880, 0.34% vs. 4/195, 0.51%; p = 0.77) and rates of disabling stroke (3/880, 1.81% vs. 1/195, 2.05%; p = 0.55) were similar between groups. In logistic regression analysis age (OR 1.079; CI 1.001- 1.162; p = 0.047) and impaired renal function (OR 1.495; CI 1.090–2.051; p = 0.013) were identified as independent risk factors for 30-day mortality.

Conclusions:

Male and female patients present similar 30-day outcomes after OPCAB suggesting a potential benefit of OPCAB in female patients. However, female patients receive more saphenous vein grafts compared to men, which may lead to impaired long-term outcomes.

Introduction

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is the most commonly performed cardiac surgery worldwide, recommended for treating complex coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients with intermediate to high SYNTAX (Synergy between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery) score and diabetes (1, 2). However, only 20%–30% of patients undergoing CABG are women (3, 4). Several studies report worse outcomes in women after CABG, including higher incidences of acute mortality, stroke, and postoperative myocardial infarction (5–7).

Reasons for these outcome differences are likely multifactorial including delayed diagnosis in women due to atypical symptoms, leading to later presentation for CABG (8, 9), a higher comorbidity burden and more urgent presentation at the time of surgery in women (10, 11), a higher incidence of non-obstructive CAD (12), smaller coronary arteries more prone to spasm (13, 14), and less frequent complete revascularization, with increased use of unfavorable bypass grafts (15, 16).

Most studies and registries investigating gender-related outcome differences in CABG combine various operative strategies, including on-pump CABG, OPCAB, and beating heart CABG. Therefore, interpretation of these findings is challenging. Previously gender-related outcome differences in on-pump CABG were described, with higher rates of emergency procedures, use of saphenous vein grafts (SVG), and postoperative complications like myocardial infarction, stroke, and wound healing disorders (WHD) as well as increased 30-day mortality in women (13).

To further clarify the impact of surgical strategies in CABG on gender-specific outcomes, our current study aims to specifically investigate gender-related differences in OPCAB only.

This work is part of the first author's dissertation thesis conducted at the University Medical Center Hamburg Eppendorf.

Patients and methods

Ethical statement

Data acquisition was performed anonymized and retrospectively. Therefore, in accordance with German law, no ethical approval is needed and informed patient consent was waived.

Patients and definitions

Between 01/2016 and 12/2021, 1,075 consecutive patients underwent isolated OPCAB at our center. Of those 880/1,075 were male (81.9%, group 1) and 195/1,075 were female (18.1%, group 2). Assignment to gender followed biological sex.

Primary endpoints for this study are adverse events during 30 days of the index procedure including all-cause mortality, postoperative myocardial infarction, major stroke and acute renal failure [Acute kidney injury network (AKIN) III]. Secondary outcomes include resternotomy for bleeding, wound healing disorders (WHD), sepsis, New York Heart association (NYHA) functional class ≥3 and postoperative creatinine levels.

Complete revascularization was defined as revascularization of all coronary segments with a stenosis of ≥50% supplying viable myocardium (17). Wound healing disorders were defined as postoperative infection involving the sternum and mediastinal space or isolated infection of the sternal subcutaneous layer. After surgery and completion of hospital stay patients were referred to cardiac rehabilitation as standard of care.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables are presented as proportions. Baseline differences between male and female patients undergoing OPCAB were detected using the chi2-test, the Fisher's exact test and the t-test. Non-parametric data was analysed using the Mann–Whitney-test. For validation of normal data distribution, the Kolmogorow-Smirnow-test was utilized. Kaplan–Meier analysis was implemented for investigating differences in survival probabilities between male and female patients after OPCAB. Identification of independent risk factors for 30-day mortality was conducted by logistic regression including the variables sex, age and preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 35%.

All test were two tailed and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline demographics

Male (group 1) and female patients (group 2) undergoing OPCAB presented no significant differences in baseline parameters regarding age (group 1: 68.99 ± 9.91 vs. group 2: 69.91 ± 9.94 years; p = 0.2413) and comorbidity and symptom burden (extracardiac artheropathy: 198/880, 22.5% vs. 42/195, 21.5%, p = 0.8531; NYHA functional class ≥ III: 469/880; 53.29% vs. 115/195, 58.97; p = 0.4683). However, common risk stratification tools (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II: 2.09% vs. 2.69%; p = 0.001) indicated a higher perioperative risk in group 2. Male patients presented with higher baseline creatinine levels (1.17 ± 0.76 vs. 1.03 ± 0.59 mg/dl; p = 0.0159) and a higher number of diseased coronary vessels (2.44 ± 1.03 vs. 2.28 ± 0.41; p = 0.033). Female patients presented more often with preoperative non ST-elevation infarction (NSTEMI) (216/880, 24.54% vs. 50/195, 25.64%; p = 0.566). Furthermore, the male population showed higher rates of LV dysfunction (LVEF < 35%: 88/880, 10.0% vs. 9/195, 4.61%; p = 0.025).

Detailed patient demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Male (n = 880) | Female (n = 195) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 68.99 ± 9.91 | 69.91 ± 9.94 | 0.24 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.28 ± 7.29 | 28.04 ± 5.43 | 0.66 |

| Prior CABG, n (%) | 9 (1.02) | 1 (0.51) | 1.00 |

| Prior PCI, n (%) | 174 (19.77) | 29 (14.87) | 0.22 |

| Myocardial infarctiona, n (%) | 249 (28.29) | 60 (30.76) | 0.61 |

| STEMI | 33 | 10 | 0.42 |

| NSTEMI | 216 | 50 | 0.56 |

| COPDb, n (%) | 65 (7.38) | 18 (9.23) | 0.46 |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 101 (11.47) | 18 (9.23) | 0.45 |

| Extracardiac atheropathyb, n (%) | 198 (22.50) | 42 (21.53) | 0.85 |

| LVEF ≤35%, n (%) | 88 (10) | 9 (4.61) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 71 (8.06) | 23 (11.79) | 0.13 |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 13 (1.47) | 5 (2.56) | 0.35 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.17 ± 0.76 | 1.03 ± 0.59 | 0.01 |

| Number of diseased vessels | 2.44 ± 1.03 | 2.28 ± 0.41 | 0.03 |

| One vessel disease, n (%) | 64 (7.3) | 29 (14.9) | 0.001 |

| Two vessel disease, n (%) | 176 (20.0) | 40 (20.5) | 0.84 |

| Three vessel disease, n (%) | 640 (72.7) | 126 (64.6) | 0.02 |

| EuroSCORE II, % median | 2.09 ± 2.35 | 2.69 ± 2.55 | 0.001 |

| NYHA ≥ III, n (%) | 469 (53.29) | 115 (58.97) | 0.46 |

Baseline data of male and female patients undergoing OPCAB.

OPCAB, off-pump coronary artery bypass; BMI, body mass index; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non ST-elevation myocardial infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

During 30 days prior to CABG.

According to EuroSCORE definitions.

Periprocedural data

No differences were seen in rates of OPCAB as emergency procedure (40/880, 4.55% vs. 11/195, 5.64%; p = 0.577). Procedure time was lower in female patients (256.13 vs. 238.02 min; p = 0.0001). Accordingly, number of performed distal bypass anastomoses was lower in group 2 (2.4 ± 0.8 vs. 2.1 ± 0.8; p < 0.001). Utilization of bilateral internal mammary artery (BIMA) was more frequently conducted in male patients (502/880, 57.04% vs. 74/195, 37.94%; p = 0.0052), whereas graft choice strategies including combination of the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) and saphenous vein grafts (SVG) (220/880, 25% vs. 66/195, 33.84%; p = 0.076) or single IMA (131/880, 14.88% vs. 50/195, 25.64%; p = 0.004) were more often applied in female patients. Accordingly, incidence of one vessel disease was higher in female patients. No differences between groups were found regarding rates of complete revascularization.

In group 2 a higher rate of red blood cell unit (RBC) administration (188/880 vs. 83/195; p = 0.0001) and a higher number of administered RBC (0.58 ± 1.76 vs. 1.03 ± 1.63 p = 0.001) was documented.

Detailed periprocedural data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| Male (n = 880) | Female (n = 195) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urgency, n (%) | |||

| Elective | 840 (95.45) | 184 (94.36) | 0.95 |

| Urgent | 40 (4.55) | 11 (5.64) | 0.57 |

| Procedure time, min median | 256.13 | 238.02 | 0.0001 |

| Number of bypasses, n | 2.40 ± 0.83 | 2.11 ± 0.82 | 0.0001 |

| Bypass graft strategy | |||

| BIMA grafting, n (%) | 502 (57.04) | 74 (37.94) | 0.005 |

| LIMA + SVG, n (%) | 220 (25) | 66 (33.84) | 0.07 |

| SVG, n (%) | 4 (0.45) | 1 (0.51) | 1 |

| IMA + radialis, n (%) | 10 (1.13) | 3 (1.53) | 0.71 |

| Single IMA, n (%) | 131 (14.88) | 50 (25.64) | 0.004 |

| Complete revascularization, n (%) | 654 (74.31) | 141 (72.30) | 0.85 |

| Prolonged inotropes ≥24 h, n (%) | 18 (2.04) | 6 (3.07) | 0.42 |

| Conversion to ECC, n (%) | 6 (0.68) | 1 (0.51) | 1 |

| RBC administration, n (%) | 188 (21.4) | 83 (42.6) | 0.0001 |

| Numbers of RBC | 0.58 ± 1.76 | 1.03 ± 1.63 | 0.001 |

Periprocedural data of male and female patients undergoing OPCAB.

OPCAB, off-pump coronary artery bypass; BIMA, bilateral internal mammary artery; LIMA, left internal mammary artery; SVG, sapheneous vein graft; ECC, extracorporeal circulation; RBC, packed red blood cells.

30-day outcomes

No significant difference regarding 30-day mortality was seen (16/880, 1.81% vs. 4/195, 2.05%; p = 0.77) between groups. Postoperative complications showed similar rates between groups regarding wound healing disorders (17/880, 1.93% vs. 7/195, 3.58%; p = 0.12) and resternotomy (10/880, 1.13% vs. 2/195, 1.02%; p = 1.0). Rates of postoperative coronary angiography were similar between groups (30/880, 3.40% vs. 8/195, 4.10%; p = 0.66). Mean ventilation time (9.62 ± 36.15 vs. 8.35 ± 15.72 h; p = 0.63), and rates of prolonged ventilation time >24 h (23/880, 2.61% vs. 5/195, 2.56%; p = 1.0) presented no differences between groups. Intensive care unit stay time was similar between groups (2.45 ± 2.91 vs. 2.37 ± 1.87 days; p = 0.08), as well as hospital stay time (8.29 ± 4.00 vs. 8.89 ± 5.99 days; p = 0.08). Rate of myocardial infarction during 30 days after the procedure was similar between groups (20/880, 2.27% vs. 5/195, 2.56%; p = 0.80), as well as rates of disabling stroke (3/880, 0.34% vs. 1/195, 0.51%; p = 0.55) and rates of renal failure (AKIN III) (11/880, 1.25% vs. 4/195, 2.05%; p = 0.49).

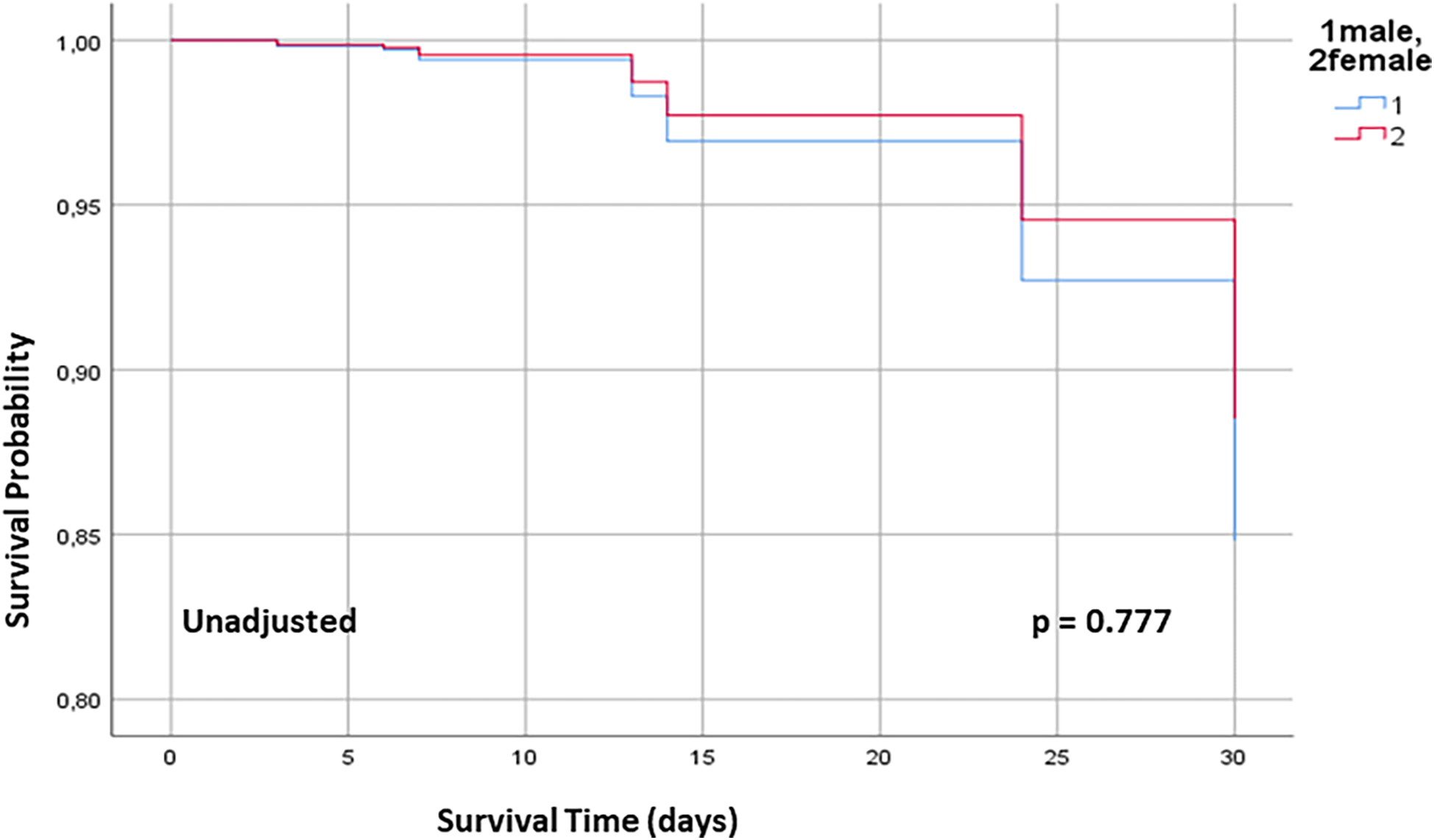

Detailed 30-day outcome parameters are summarized in Table 3. See Figure 1 for Kaplan–Meier curve.

Table 3

| Male (n = 880) | Female (n = 195) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality, n (%) | 16 (1.81) | 4 (2.05) | 0.77 |

| WHDa, n (%) | 17 (1.93) | 7 (3.58) | 0.18 |

| Resternotomy, n (%) | 10 (1.13) | 2 (1.02) | 1 |

| Coronary angiography, n (%) | 30 (3.40) | 8 (4.10) | 0.66 |

| PCI, n (%) | 8 (0.91) | 2 (1.03) | 1.0 |

| Ventilation time, h | 9.62 ± 36.15 | 8.35 ± 15.72 | 0.63 |

| Ventilation >24 h, n (%) | 23 (2.61) | 5 (2.56) | 1 |

| ICU stay, days | 2.45 ± 2.91 | 2.37 ± 1.87 | 0.08 |

| Hospital stay, days | 8.29 ± 4.00 | 8.89 ± 5.99 | 0.08 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 20 (2.27) | 5 (2.56) | 0.79 |

| Disabling stroke, n (%) | 3 (0.34) | 1 (0.51) | 0.55 |

| Renal failure (AKIN III), n (%) | 11 (1.25) | 4 (2.05) | 0.49 |

30-day outcome parameter of male and female patients undergoing OPCAB.

OPCAB, off-pump coronary artery bypass; WHD, wound healing disorders, PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ICU, intensive care unit; AKIN, acute kidney injury network; MACE, major adverse cardiac even.

Including superficial wound healing disorders and deep sternal wound infection.

Figure 1

30 days Kaplan–Meier survival curve for male and female patients undergoing OPCAB. OPCAB off-pump coronary artery bypass.

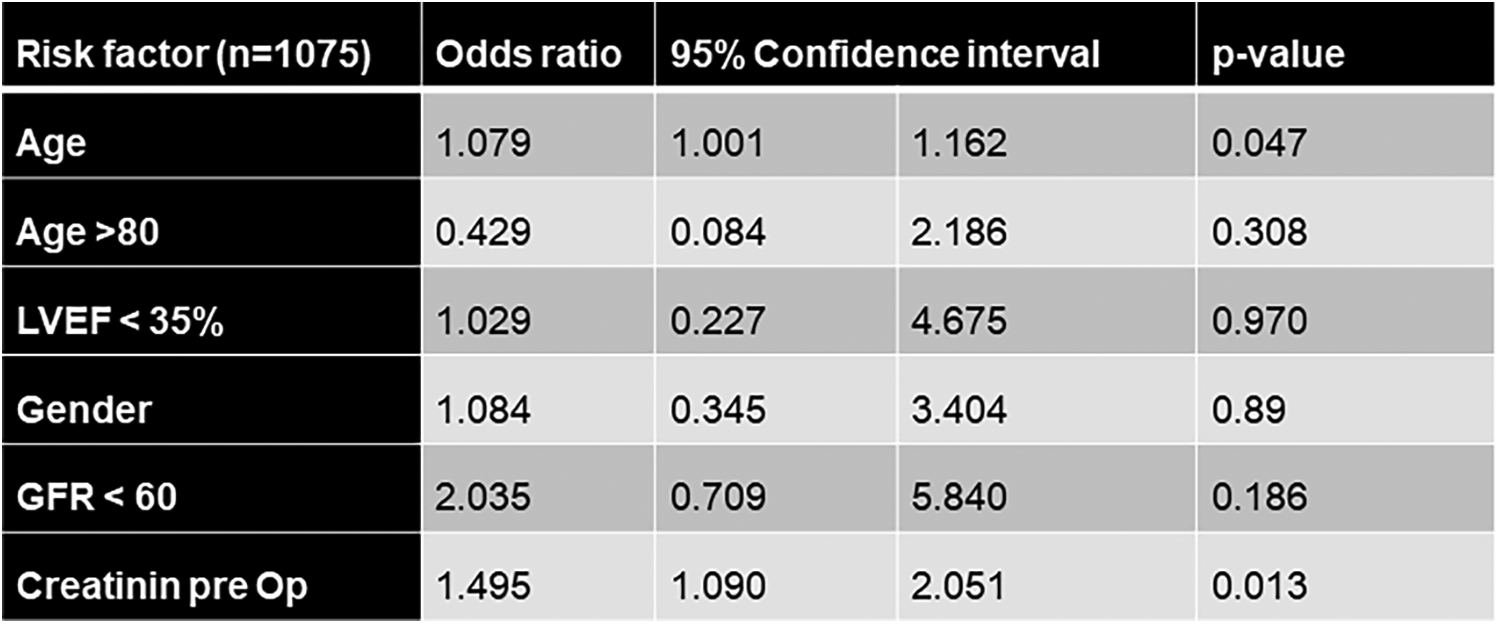

In logistic regression analysis independent risk factors for 30-day mortality consisted of increased preoperative creatinine levels (OR 1.495; CI 1.090–2.051; p = 0.013) and age (OR 1.079; CI 1.001–1.162; p = 0.047). Preoperative LVEF <35% (OR 1.029; CI 0.227–4.675; p = 0.970) and gender (OR 1.084, CI 0.345–3.404; p = 0.89) were not predictive for mortality during 30 days after OPCAB.

Detailed results of logistic regression analysis are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Logistic regression analysis for 30-day mortality after OPCAB. OPCAB off-pump coronary artery bypass, NYHA New York Heart Association, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction.

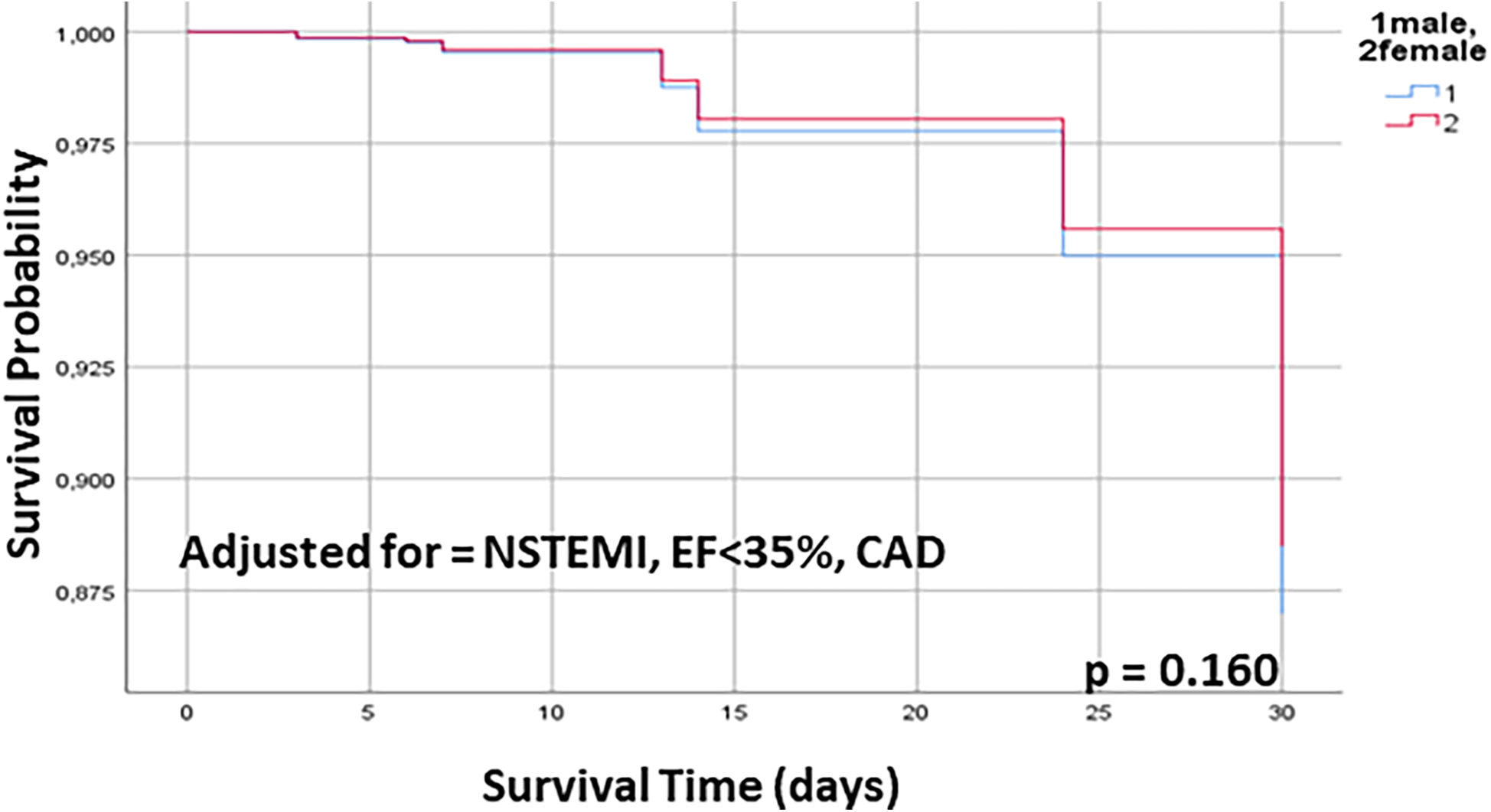

After adjustment for rates of NSTEMI, reduced LVEF and extent of CAD no significant differences for 30-day mortality were found (Figure 3).

Figure 3

30 days Kaplan–Meier survival curve for male and female patients undergoing OPCAB, adjusted for NSTEMI, EF < 35% and extent of CAD. OPCAB off pump coronary artery bypass, NSTEMI non ST-elevation infarct, EF ejection fraction, CAD coronary artery disease.

Discussion

Main findings of the herein conducted study are: (I) male and female patients present similar 30-day outcomes subsequent to OPCAB regarding 30-day mortality, rates of disabling stroke, myocardial infarction and acute renal failure, (II) periprocedurally female patients receive more often and higher numbers of RBC units and rate of BIMA utilization is lower in female patients, (III) 30-day survival after OPCAB is similar between male and female patients even after adjustment for preprocedural NSTEMI, severely reduced LVEF and extent of CAD, (IV) identified risk factors for adverse 30-day outcomes after OPCAB consist of age and preoperative impaired renal function, whereas gender presented no impact on 30-day mortality after OPCAB.

Female patients are prone to impaired postoperative outcomes across a variety of surgical interventions (18) including CABG (19) with documented higher rates of mortality and even after percutaneous coronary intervention for ischemic heart disease (20). While this phenomenon is likely multi-factorial, investigation of different operative strategies in CABG is lacking and herein similar results of OPCAB in male and female patients were shown for 30-day outcomes. Although larger scale randomized controlled trials could not prove significant impact of the OPCAB approach on clinical endpoints (21), OPCAB is widely considered to present advantages in specific subsets of patients including elderly patients, patients with significant comorbidities and patients with reduced LVEF and/or diabetes (22). The herein presented results suggest that female patients might also benefit from OPCAB. Given the possible reasons for worse outcomes in female patients after CABG, which consist of a higher prevalence of microvascular disease compared to men, smaller coronary artery diameters with subsequent higher rates of graft to target vessel size mismatch and a worse preoperative status (23–25), as reflected in this work by a higher EuroSCORE II in women, OPCAB might outplay its specific advantages in women by reducing systemic inflammatory response, organ dysfunction and coagulation disorders, as well as addressing the mentioned gender-specific anatomical (small artery diameters, microvascular disease) and clinical challenges by avoiding CPB (26). This may be especially true for OPCAB procedures using total arterial revascularization and a non-aortic touch approach, which was shown to reduce rates of periprocedural stroke rates and long-term rates of re-revascularization and myocardial infarction (27, 28). Although rate of BIMA utilization in women was lower compared to male patients in our work, which may be partly attributable to higher rates of three vessel CAD in male patients, BIMA utilization rate was still markedly higher than the average of western countries (29). Acute mortality, stroke and myocardial infarction rates were not only similar between men and women in this study, but low for the entire patient cohort. These results are in line with previous findings of a retrospective study of Puskas et al., who showed decreased rates of cardiovascular events and mortality after OPCAB compared to CABG as well as decrease of those rates in women undergoing OPCAB (30). Therefore, this work adds to the growing evidence for benefits of OCPAB in women. Additionally, our findings regarding similar mortality rates between male and female patients undergoing OPCAB were consistent after adjustment for several confounders suggesting a significant advantageous impact of the OPCAB approach for myocardial revascularization in women. However, it has to be emphasized that the compared groups presented with certain differences in baseline characteristics which may be an indicator of selection bias, potentially hampering interpretability of results. The comparably high rates of BIMA utilization in women in this work may contribute to a lasting protective effect regarding mortality, re-revascularization and myocardial infarction even in the long term, since total arterial revascularization was shown to be beneficial compared to utilization of SVG (27), although this remains speculative since no long-term data are available in the context of this study. Since a long-term benefit for OPCAB compared to CABG was not documented so far (31), further studies regarding gender specific long-term effects of the surgical approach in myocardial revascularization are warranted.

The increased rates of RBC administration is still a matter of concern in women, since it was shown to be connected with increased long-term mortality (32). However, OPCAB is commonly considered to be associated with lower rates and decreased numbers of RBC administration, which might be an additional benefit of OPCAB in women. Previous work showed that female patients undergoing CABG/OPCAB tend to present older and with a higher symptom burden at time of surgery compared to male counterparts (33, 34). A phenomenon which was not confirmed by the herein presented data. Reasons for that discrepancy remain speculative but may involve an increase in awareness of gender-specific variability of CAD associated symptoms over the last decade. While age is commonly considered a risk factor for adverse outcomes in a variety of surgical interventions, and was also shown to be predictive for 30-day mortality in logistic regression analysis in this work, an impaired renal function was primarily shown to increase duration of hospital stay and costs (35) in CABG procedures. However, specific analyses regarding influence of an impaired renal function on postoperative outomes in CABG presented adverse long-term outomes and also an increase in early mortality (36) which was confirmed by the herein conducted analyses.

Limitations

Limitations are inherent in the retrospective, single-center study design with limited patient numbers: patients were not randomized to a specific treatment, therefore patient preselection with hidden confounders may apply. Furthermore, no long-term outcomes of the herein investigated patient population is available. Female patients in this work were rather higher age and therefore post-menopausal, comparability to other studies comparing outcomes in male and female patients of younger age is therefore limited.

Conclusions

Male and female patients present similar 30-day outcomes after OPCAB regarding mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction and renal failure suggesting a potential benefit of OPCAB in female patients. However, female patients receive more saphenous vein grafts compared to men, which may lead to impaired long-term outcomes. Further larger scale studies are warranted to clarify the impact of the surgical approach in CABG on gender specific outcomes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

RA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. FS: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. TK: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SP: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JB: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XH: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. BR: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YS: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. EG: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HR: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. BS: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AS: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AKIN, acute kidney injury network; BIMA, bilateral internal mammary artery; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; LIMA, left internal mammary artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; OPCAB, off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting; OR, odds ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RBC, red blood cells; SVG, saphenous vein graft; SYNTAX, Synergy between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery; WHD, wound healing disorder.

References

1.

NeumannFJSousa-UvaMAhlssonAAlfonsoFBanningAPBenedettoUet al2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40(2):87–165. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394

2.

LawtonJSTamis-HollandJEBangaloreSBatesERBeckieTMBischoffJMet al2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2022) 145(3):e18–e114.

3.

BenjaminEJMuntnerPAlonsoABittencourtMSCallawayCWCarsonAPet alHeart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2019) 139:e56–e528. Correction appears in Circulation 2020;141:e33. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659

4.

GaudinoMDi MauroMFremesSEDi FrancoA. Representation of women in randomized trials in cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. (2021) 10:e020513. 10.1161/JAHA.120.020513

5.

AlamMLeeVVElaydaMAShahzadSAYangEYNambiVet alAssociation of gender with morbidity and mortality after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. A propensity score matched analysis. Int J Cardiol. (2013) 167:180–4. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.12.047

6.

GaudinoMDi FrancoAAlexanderJHBakaeenFEgorovaNKurlanskyPet alSex differences in outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Eur Heart J. (2021) 43:18–28. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab504

7.

Bryce RobinsonNNaikARahoumaMMorsiMWrightDHameedIet alSex differences in outcomes following coronary artery bypass grafting: a meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. (2021) 33:841–7. 10.1093/icvts/ivab191

8.

FinkNNikolskyEAssaliAShapiraOKassifYBaracYDet alRevascularization strategies and survival in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease. Ann Thorac Surg. (2019) 107:106–11. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.07.070

9.

HansenKWSoerensenRMadsenMMadsenJKJensenJSvon KappelgaardLMet alDevelopments in the invasive diagnostic-therapeutic cascade of women and men with acute coronary syndromes from 2005 to 2011: a nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e007785. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007785

10.

EnumahZOCannerJKAlejoDWarrenDSZhouXYenokyanGet alPersistent racial and sex disparities in outcomes after coronary artery bypass surgery: a retrospective clinical registry review in the drug-eluting stent era. Ann Surg. (2020) 272:660–7. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004335

11.

AlamMBandealiSJKayaniWTAhmadWShahzadSAJneidHet alComparison by meta-analysis of mortality after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting in women versus men. Am J Cardiol. (2013) 112:309–17. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.03.034

12.

ReynoldsHRPicardMHSpertusJAPeteiroJLopez SendonJLSeniorRet alNatural history of patients with ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: the CIAO-ISCHEMIA study. Circulation. (2021) 144:1008–23. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046791

13.

HessianRJabagiHNguJMCRubensFD. Coronary surgery in women and the challenges we face. Can J Cardiol. (2018) 34:413–21.

14.

FisherLDKennedyJWDavisKBMaynardCFritzJKKaiserGet alAssociation of sex, physical size, and operative mortality after coronary artery bypass in the coronary artery surgery study (CASS). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (1982) 84:334–41. 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)39000-2

15.

JawitzOKLawtonJSThibaultDO'BrienSHigginsRSDSchenaSet alSex differences in coronary artery bypass grafting techniques: a society of thoracic surgeons database analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. (2022) 113:1979–88. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.06.039

16.

SchwannTAHabibRHWallaceAShahianDMO'BrienSJacobsJPet alOperative outcomes of multiple-arterial versus single-arterial coronary bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. (2018) 105:1109–19. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.10.058

17.

ZimarinoMCalafioreAMDe CaterinaR. Complete myocardial revascularization: between myth and reality. Eur Heart J. (2005) 26(18):1824–30. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi249

18.

WallisCJDJerathACoburnNKlaassenZLuckenbaughANMageeDEet alAssociation of surgeon-patient sex concordance with postoperative outcomes. JAMA Surg. (2022) 157:146–56. 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.6339

19.

AttiaTKochCGHoughtalingPLBlackstoneEHSabikEMSabikJF3rd. Does a similar procedure result in similar survival for women and men undergoing isolated coronary artery bypass grafting?J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2017) 153:571–9.e9. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.11.033

20.

SambolaADel BlancoBGKunadianVVogelBChieffoAVidalMet alSex-based differences in percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes in patients with ischaemic heart disease. Eur Cardiol. (2023) 18:e06. 10.15420/ecr.2022.24

21.

DiegelerABörgermannJKappertUHilkerMDoenstTBöningAet alFive-year outcome after off-pump or on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting in elderly patients. Circulation. (2019) 139(16):1865–71. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035857

22.

YooKJ. The past, present, and future of off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. J Chest Surg. (2025) 58(4):121–33. 10.5090/jcs.24.122

23.

LanskyAJNgVGMaeharaAWeiszGLermanAMintzGSet alGender and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis, plaque composition, and clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2012) 5(3 Suppl):S62–72. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.02.003

24.

DodgeJTJrBrownBGBolsonELDodgeHT. Lumen diameter of normal human coronary arteries. Influence of age, sex, anatomic variation, and left ventricular hypertrophy or dilation. Circulation. (1992) 86(1):232–46. 10.1161/01.cir.86.1.232

25.

VaccarinoVLinZQKaslSVMatteraJARoumanisSAAbramsonJLet alGender differences in recovery after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2003) 41(2):307–14. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02698-0

26.

ComaniciMBithiNRajaSG. Comparison of outcomes between total arterial off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Am J Cardiol. (2025) S0002-9149(25):00247–4.

27.

TranbaughRFLucidoDJDimitrovaKRHoffmanDMGellerCMDinchevaGRet alMultiple arterial bypass grafting should be routine. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2015) 150(6):1537–44. discussion 1544–5. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.08.075

28.

ZhaoDFEdelmanJJSecoMBannonPGWilsonMKByromMJet alCoronary artery bypass grafting with and without manipulation of the ascending aorta: a network meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 69(8):924–36. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.071

29.

IribarneAGoodneyPPFloresAMDeSimoneJDiScipioAWAustinAet alNational trends and geographic variation in bilateral internal mammary artery use in the United States. Ann Thorac Surg. (2017) 104(6):1902–7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.08.055

30.

PuskasJDKilgoPDKutnerMPuscaSVLattoufOGuytonRA. Off-pump techniques disproportionately benefit women and narrow the gender disparity in outcomes after coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation. (2007) 116(11 Suppl):I192–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678979

31.

PeksaMNawotkaMMoskalLAwadAKStankowskiTPieszkoKet alLong-term clinical and angiographic outcomes of off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. J Surg Res. (2025) 309:8–18. 10.1016/j.jss.2025.02.041

32.

LeeSHKimJELeeJHJungJSSonHSKimHJ. Perioperative red blood cell transfusion and long-term mortality in coronary artery bypass grafting: on-pump and off-pump analysis. J Clin Med. (2025) 14(8):2662. 10.3390/jcm14082662

33.

BlasbergJDSchwartzGSBalaramSK. The role of gender in coronary surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2011) 40(3):715–21.

34.

SchmidtAFHaitjemaSSartipyUHolzmannMJMalenkaDJRossCSet alUnravelling the difference between men and women in post-CABG survival. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:768972. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.768972

35.

LaParDJRichJBIsbellJMBrooksCHCrosbyIKYarboroLTet alPreoperative renal function predicts hospital costs and length of stay in coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. (2016) 101(2):606–12. discussion 612. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.079

36.

van StratenAHHamadSKoeneMAMartensBMTanEJBerreklouwMEet alWhich method of estimating renal function is the best predictor of mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting?Neth Heart J. (2011) 19(11):464–9. 10.1007/s12471-011-0184-3

Summary

Keywords

coronary artery bypass grafting, coronary artery disease, gender, STEMI, NSTEMI, OPCAB

Citation

Akram R, Sobik F, Knochenhauer T, Philipp SA, Brickwedel J, Hua X, Reiter B, Zipfel S, Schneeberger Y, Girdauskas E, Reichenspurner H, Sill B and Schaefer A (2025) Gender related outcome differences in off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1641784. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1641784

Received

05 June 2025

Accepted

22 July 2025

Published

01 August 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Fabiana Isabella Gambarin, Veruno (IRCCS), Italy

Reviewed by

Nobuaki Fukuma, Columbia University, United States

Alessandro Maloberti, University of Milano Bicocca, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Akram, Sobik, Knochenhauer, Philipp, Brickwedel, Hua, Reiter, Zipfel, Schneeberger, Girdauskas, Reichenspurner, Sill and Schaefer.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andreas Schaefer and.schaefer@uke.de

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.