- 1Department of Microbiology, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

- 2Dental Research Division, Guarulhos University, Guarulhos, Brazil

- 3Department of Bioscience, Piracicaba Dental School, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Piracicaba, Brazil

The present study evaluated the antibiofilm effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus within a subgingival multispecies biofilm. Lactobacillus acidophilus (La5) at 1 × 102, 1 × 104, and 1 × 106 were included at the beginning of biofilm formation, which lasted 7 days. The biofilms comprised 33 periodontitis-related bacterial species and the Calgary Biofilm device was used. At the end, DNA–DNA hybridization (checkerboard) was performed. A Kruskal–Wallis test followed by a Dunn post hoc test were performed (p ≤ 0.05). La5 at 1 × 104 and 1 × 106 reduced the total counts of biofilm and the proportions of red and green complexes when compared to the control biofilm without La5 (p ≤ 0.05). La5 at 1 × 104 increased the proportions of Actinomyces complex compared to the controls (p ≤ 0.05). Both La5 at 1 × 104 and 1 × 106 decreased levels of 20 and 14 distinct species, respectively, including Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Fusobacterium nucleatum polymorphum, and Parvimonas micra compared to the control (p ≤ 0.05). Only La5 at 1 × 104 reduced the levels of Tannerella forsythia, Fusobacterium periodonticum, and Aggregatibacter actinomycetencomytans compared to the control (p ≤ 0.05). L. acidophilus inhibited establishing periodontic pathogens from red complex such as P. gingivalis and T. forsythia in a subgingival multispecies biofilm.

1. Introduction

Periodontitis is clinically characterized by the loss of protective and supporting tissues of the teeth. Such destruction involving loss of periodontal ligament, cement, and alveolar bone results in a proper niche to a dysbiotic microbiome, which results in an intense immune-inflammatory response (1). The dysbiosis starts without clinical signs (2) and this bacteria-inflammation binomial remains in a positive feedback loop if the patient is not properly treated. New findings regarding periodontal disease have changed the perspective regarding its etiology and the role of those considered “periodontal pathogens,” showing a more diverse and complex periodontitis-associated microbiota, related to dysbiosis, i.e., a shift in the proportion of beneficial and pathogenic microorganisms that disrupts the homeostasis seen in health (3).

Traditionally, periodontal treatment requires control of risk factors (such as diabetes, smoking, insufficient biofilm control), mechanical debridement of affected surfaces, and administration of systemic antibiotics in severe cases (4); however, studies show that due to a biofilm characteristic called resilience, after 1 year of treatment, pathogenic bacteria tend to increase in proportion, and this may lead to disease recurrence (5). In this regard, several adjunctive therapies have been studied, such as antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (6), combinations of antibiotics (6), statins (7), and probiotics (8), in order to prevent recolonization and propagation of bacterial pathogens and/or modulate the immune response, regaining the microbiome ecological balance (9).

Probiotics are living microorganisms that may promote benefits in health (10) and they have been studied as adjunctive therapy in periodontal treatment due to their ability to decrease the colonization of pathogens and to modulate host immune response. In vitro studies (11, 12) have shown that gingival epithelial cells (GECs) infected either with Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans or Porphyromonas gingivalis and treated with different strains of probiotics could reduce the adhesion of pathogens to GECs as well as attenuating the release of important inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, CXCL-8, and GM-CSF. In addition, the postbiotics derived from lactobacilli have been shown to reduce A. actinomycetemcomitans biofilm formation and to decrease the expression of virulence factors, such as cytolethal distending toxin and leukotoxin (13). Moreover, an in vivo study using a microbial consortium to induce experimental periodontitis containing P. gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Prevotella intermedia, and Streptococcus gordonii was successfully treated when the animals were inoculated with probiotics, by reducing alveolar bone loss (14). However, all the aforementioned studies showed that the effectiveness of treatment with probiotics depends on the strain used, since some strains have an inflammatory potential.

To add to the knowledge of the use of probiotics in the control of dysbiosis seen in periodontal disease, we evaluated whether L. acidophillus La5 was able to interfere in a subgingival biofilm composition through an in vitro model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Formation of multispecies subgingival biofilm

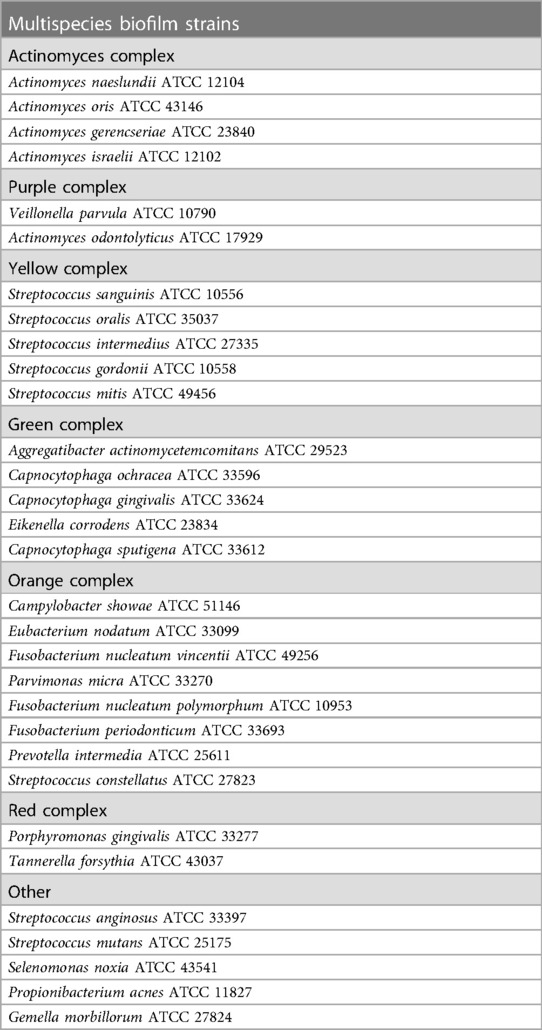

An in vitro multispecies biofilm was developed, as explained by Miranda et al. (15) and Pingueiro et al. (16), with inoculum alterations. The bacterial species used in the multispecies biofilm model are listed in Table 1. All bacterial species were procured from the ATCC company.

Table 1. Species cultivated in multispecies biofilms grouped into the bacterial complexes (17).

Tryptone soy agar plus 5% sheep blood (Probac, São Paulo, Brazil) was the medium to grow the majority of the species under anaerobic conditions (85% nitrogen, 10% carbon dioxide, and 5% hydrogen), while Eubacterium nodatum was cultivated on fastidious anaerobic agar plus 5% sheep blood. Porphyromonas gingivalis was grown on tryptone soy agar plus yeast extract and supplemented with 1% hemin, 5% menadione, and 5% sheep blood. Tannerella forsythia was cultivated on tryptone soy agar plus yeast extract, supplemented with 1% hemin, 5% menadione, 5% sheep blood, and 1% N-acetylmuramic acid. All species were grown on agar plates for 24 h and were then moved to glass tubes with BHI culture medium (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) enriched with 1% hemin. After 24 h of growth on conical tubes, the optical density (OD) was adjusted for the inoculum to have about 108 cells/mL of each bacterial species. A dilution of individual bacterial cell suspensions was performed, and 100-µL aliquots containing 106 cells from each species were mixed with 11,700 µL of BHI broth supplemented with 1% hemin and 5% sheep blood to acquire a 15-mL inoculum.

The multispecies biofilm model was established using a Calgary biofilm device in a 96-well plate (Nunc; Thermo Scientific, Roskilde, Denmark). A 150-µL aliquot of the inoculum was placed into each well, corresponding to ∼1 × 104 cells of each bacterial species, except for P. gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia, whose inocula were modified to 2 × 104 cells. A lid comprising polystyrene pins was utilized to cover the 96-well plate (Nunc TSP System; Thermo Scientific, Roskilde, Denmark). Coated plates were incubated at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. On day 3, the medium was replaced with fresh BHI broth supplemented with 1% hemin and 5% sheep blood, and the biofilm was maintained at 37°C under anaerobic conditions for another 4 days to achieve 7-day-old biofilms (15, 16). Three distinct experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.2. Preparation of Lactobacillus acidophilus (La5)

L. acidophilus La5™ (CHR Hansen Holding A/S, Hørsholm, Denmark) was used. Before the experiments, the strain was stored in 20% glycerol at −80°C. L. acidophilus La5 was cultivated under microaerophilic conditions in Lactobacilli MRS broth and agar (Lactobacilli MRS, Difco). Then, bacteria were grown in liquid media until the midlog phase. After that, the suspension was adjusted to an OD 590 nm ∼ 0.9, corresponding to 2 × 108 CFU/mL. Then, the inoculum values of La5 were adjusted to final values of 1 × 102, 1 × 104, and 1 × 106 CFU/mL for each group of analysis.

2.3. DNA–DNA hybridization (checkerboard)

Three 7-day biofilm coated pins from each group and from each experiment were washed in phosphate-buffered solution and transferred to microcentrifuge tubes containing 150 μL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.6)), followed by the addition of 100 μL of 0.5M NaOH. The tubes containing the pins and the final solution were boiled for 10 min, and the solution was neutralized with 0.8 mL of 5M ammonium acetate. The samples were analyzed individually for the presence and quantity of 33 bacterial species using the DNA–DNA hybridization technique. Briefly, biofilm samples were lysed by boiling them and by the ammonium acetate as described above. The corresponding DNA was plated onto a nylon membrane using a Minislot device (Immunetics, Cambridge, MA, USA). After attachment to the membrane, the DNA samples were placed in a Miniblotter 45 (Immunetics). Digoxigenin labeled with DNA probes of the entire genome of the subgingival species was hybridized to the individual lanes of the Miniblotter 45. The membranes were washed, and DNA probes were detected using a specific antibody against digoxigenin conjugated to phosphatase alkaline. The signals were detected using AttoPhos substrate (Amersham Life Sciences, Arlington Heights, IL, USA), and the results were obtained using Typhoon Trio Plus (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Two lanes in each run contained standards with 105 and 106 cells of each strain. Signals obtained with the Typhoon Trio were converted into absolute counts by comparison with the standards on the same membrane. Failure to detect a signal was recorded as zero. The values obtained upon treatment with La5 were compared to those of the negative and positive controls (15, 18). The data were analyzed using a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by a Dunn post hoc test (p ≤ 0.05).

3. Results

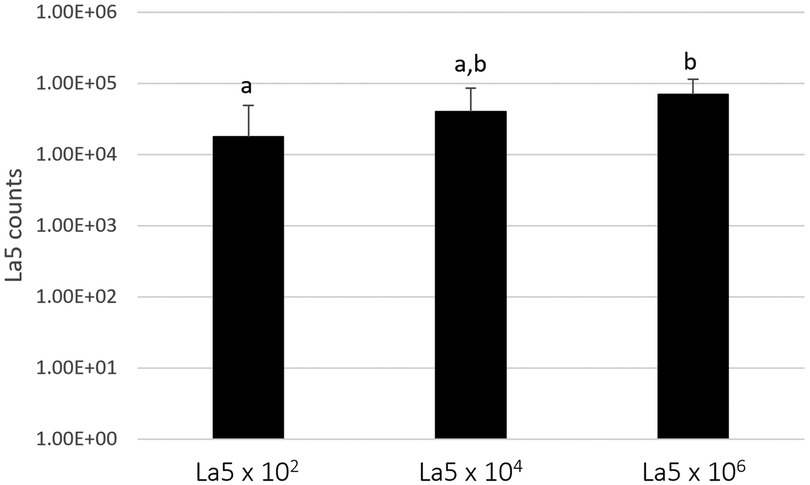

Figure 1 shows the counts of L. acidophilus (La5) within the subgingival multispecies biofilm. La5 × 106 presents three times more counts than La5 × 102 (p ≤ 0.05). La5 × 104 counts did not differ from any other group (p ≥ 0.05).

Figure 1. Mean counts of La5 after 7 days of biofilm formation within a multispecies biofilm. Different letters indicate statistical significance between groups by Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn's post hoc test (p ≤ 0.05). La5 × 102 means initial inoculum with La5 × 102 CFU/mL; La5 × 104 means initial inoculum with La5 × 104 CFU/mL; and La5 × 106 means initial inoculum with La5 × 106 CFU/mL.

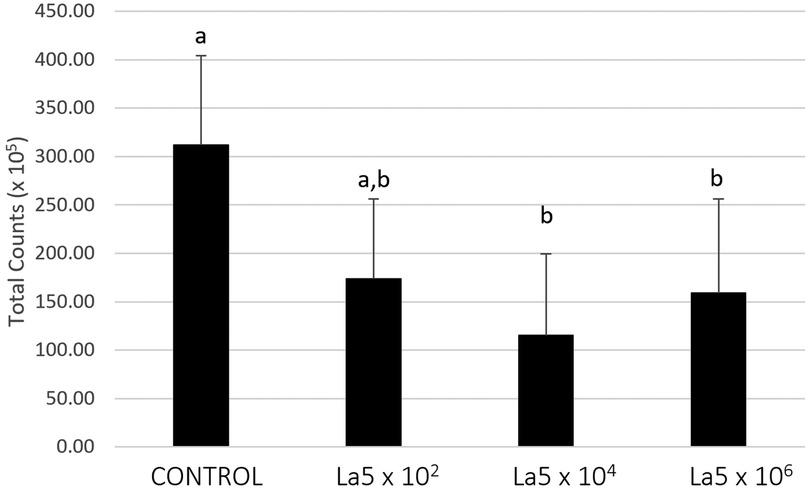

Figure 2 shows the total counts of all microorganisms included within the biofilm model. La5 × 104 and La5 × 106 significantly reduced the biofilm amount when compared to biofilm without any treatment (p ≤ 0.05). Data from the La5 × 102 were not significant (p ≥ 0.05) to any of the other groups; therefore, this group was excluded from the next analysis.

Figure 2. Mean total counts of multispecies biofilm without any treatment (control) and treated with La5 × 102, La5 × 104, and La5 × 106. Different letters indicate statistical significance between groups by Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn's post hoc test (p ≤ 0.05). La5 × 102 means initial inoculum with La5 × 102 CFU/mL; La5 × 104 means initial inoculum with La5 × 104 CFU/mL; and La5 × 106 means initial inoculum with La5 × 106 CFU/mL.

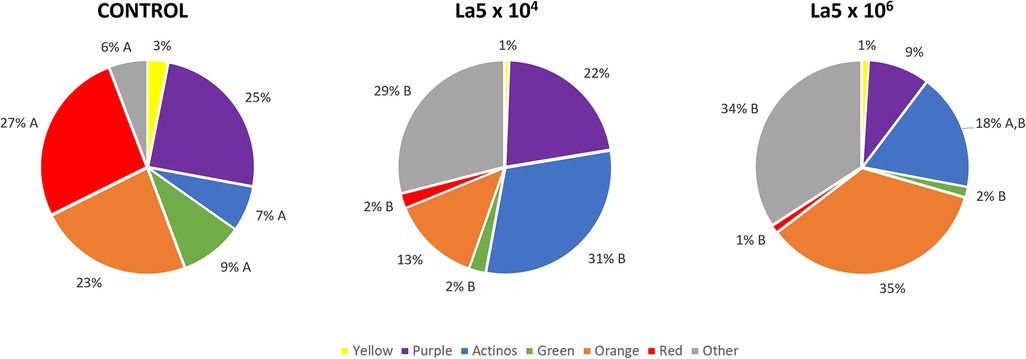

Figure 3 shows the La5 effects on bacterial complexes, as determined by Socransky et al. (19). Both La5 × 104 and La5 × 106 significantly decreased proportions of pathogens in the red complex and those of the beneficial green complex to a very similar number when compared to control (p ≤ 0.05). On the other hand, both La5 × 104 and La5 × 106 significantly increased the proportions of other complexes (p ≤ 0.05). Finally, only La5 × 104 increased proportions of bacteria in the health-associated actinos complex when compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3. Mean proportions of bacterial complexes multispecies biofilm without any treatment (control) and treated with La5 × 104 and La5 × 106. The colors represent different microbial complexes described by Socransky et al. (17). Different letters mean statistical significance among groups within the same complex. Statistical analysis performed using Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn post hoc (p ≤ 0.05). La5 × 102 means initial inoculum with La5 × 102 CFU/mL; La5 × 104 means initial inoculum with La5 × 104 CFU/mL; and La5 × 106 means initial inoculum with La5 × 106 CFU/mL.

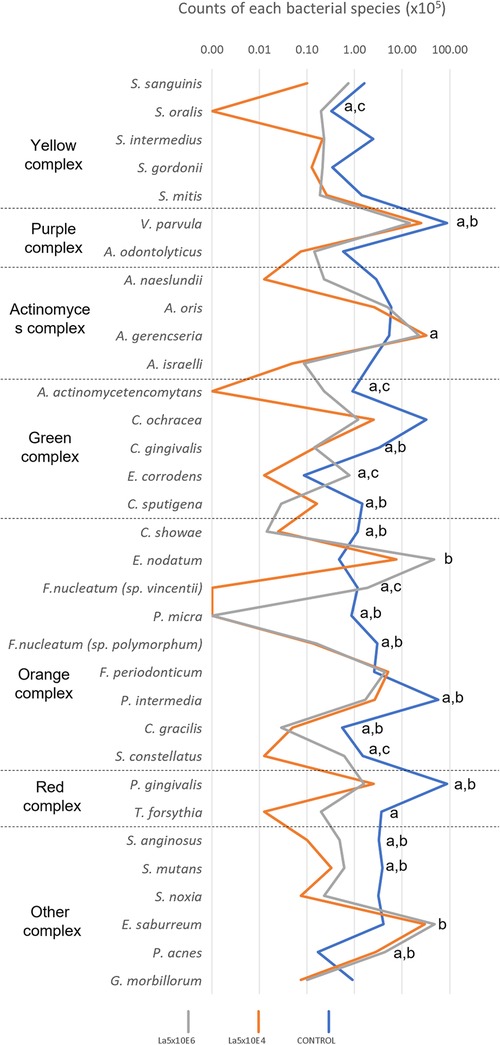

Figure 4 demonstrates the results of the counts of each bacterial species within multispecies biofilm. La5 × 104 significantly diminished the counts of 20 species while La5 × 106 decreased the counts of 14 species (p ≤ 0.05) when compared to counts of bacterial species within biofilm without any treatment. Both treatment groups share inhibitory effects on 12 species, highlighting the effects on P. gingivalis (red complex), Campylobacter showae, Campylobacter gracilis, Parvimonas micra, Fusobacterium nucleatum polymorphum, and Prevotella intermedia (members of the orange complex). Of even greater impact, only La5 × 104 significantly reduced the counts of T. forsythia, another member of the red complex, and Fusobacterium periodonticum, a member of the orange complex. In contrast, La5 × 106 increased the counts of Eubacterium nodatum, a member of the orange complex. When comparing both La5 treatments, La5 × 104 significantly reduced the counts of Streptococcus oralis, Aggregatibacter actinomycetencomytans, Eikenella corrodens, Fusobacterium nucleatum vicentii, and Streptococcus constellatus (p ≤ 0.05). Therefore, the subgingival multispecies biofilm formed in the presence of La5 × 104 presented lower counts of three major periodontic pathogens such as P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, and A. actinomycetencomytans.

Figure 4. Mean total counts of the species included in the biofilm without any treatment (control) and treated with La5 × 104 and La5 × 106. Statistical analysis was performed by the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn post hoc test (p ≤ 0.05). Letter “a” indicates statistical difference between La5 × 104 and control but without statistical difference between La5 × 104 and La5 × 106; “b” indicates statistical difference between La5 × 106 and control but without statistical difference between La5 × 104 and La5 × 106; and “c” indicate statistical difference among La5 × 104 and the two other groups.

4. Discussion

Periodontitis is a chronic multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with a mainly structured biofilm, composed of specific microorganisms and their products, that may guide to tissue damage (20). Herein, L. acidophilus reduced biofilm total counts, the red complex proportion, and the amount of the mainly periodontopathogens, such as P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, P. micra, F. nucleatum polymorphum, P. intermedia, and A. actinomycetencomytans, within a subgingival multispecies biofilm model.

The subgingival biofilm is considered the main etiological factor of periodontal disease. The classical work by Socransky et al. (17) grouped bacterial species in the subgingival biofilm into microbial complexes. The yellow (Streptococcus spp.), green (Campylobacter spp.), purple (V. parvula and A. odontolyticus), and actinos (Actinomyces spp.) complexes were associated with periodontal healthy conditions, while the orange complex (P. micra, Fusobacterium spp., and P. intermedia) was associated to transition from health to disease. Finally, the red complex (P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, and Treponema denticola) was associated with diseased conditions of the periodontum. Although nowadays it is known that the presence of bacterial species in periodontal-diseased sites is much more diverse than the 40 species included in the Socransky complexes (21), this analysis is still an excellent parameter to evaluate antimicrobial effects until new knowledge establish novel periodontal pathogens.

Currently, an agent acting only on the pathogens and their virulence factors is preferable to a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent since some bacterial species are associated with healthy conditions (22). In this way, both La5 × 104 and La5 × 106 reduced the red complex from 27% to 2% and 1%, respectively. This is a considerable reduction in the same levels observed with the aid of well-known antimicrobials, such as chlorhexidine and cetylpyridinium chloride (23). In line with the current concept, La5 × 104 increased proportions of actinomyces complex associated with healthy conditions.

The present data corroborate the literature that shows that L. acidophilus diminishes the P. gingivalis abundance within mono and three-species biofilm (24). In addition, the quantities of an A. actinomycetencomytans monospecies biofilm were reduced by L. acidophilus La5 (13). Thus, L. acidophilus La5 has a potential effect as an antibiofilm agent, increasing the scientific basis for future clinical studies for the treatment of periodontitis.

P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, and possibly other oral bacteria species have been recently indicated as strategic actors in the dysbiosis of the subgingival biofilm, leading to periodontal disease. The presence of these microorganisms can stimulate the transition from a health-associated biofilm to a pathogenic one and start the destruction of tissue due to an increased immunoinflammatory reaction (25). In these circumstances, the reduction of both bacteria by La5 × 104 is an outstanding result, explained by the physical proximity of microorganisms within the biofilm that increases the probability of synergistic or antagonistic interactions.

Lactobacillus ssp. produces several antimicrobial compounds, such as hydrogen peroxide, lactate, teichoic acid, and bacteriocins (26, 27), that can inhibit a range of microorganisms, such as P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetencomitans. Moreover, studies show that lactobacilli can alter the transcription profile of P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetencomitans, thus interfering in their ability to colonize the host tissues and subvert the immune response; for example, by downregulating the expression of fimA, an important virulence factor-related fimbriae formation of P. gingivalis, and reduction of leukotoxin (ltxA) produced by A. actinomycetencomitans.

Another important finding is the reduction of all species of Fusobacterium genera present in the model (F. nucleatum vincentii, F. nucleatum polymorphum, and F. periodonticum) by La5 × 104. The genera Fusobacterium plays a relevant role in the transition from periodontal health to disease (28). Fusobacterium nucleatum is indicated as the most prevalent anaerobic, Gram-negative species in the late periods of the disease and has been considered a possible periodontal pathogen (29). Some authors (29, 30) have reported that the presence of F. nucleatum is mainly associated with individuals with periodontitis and periodontal abscesses, and its levels are reduced after effective periodontal therapy. As an intermediate colonizer of dental biofilm and one of the first Gram-negative species to be stable in the subgingival biofilm, Fusobacterium species play an important role in the interactions between Gram-positive and Gram-negative species, contributing to the colonization of other anaerobic species, including the pathogens of the red complex (28).

The limitations of this study include the absence of Treponema denticola in the model. Although relevant to the development of periodontitis, previous articles using the same model did not include it due to the difficulty of growing this bacterium in vitro. Another limitation is the time of contact of LA5 with the biofilm. How to administer the lactobacilli in vivo to keep it stuck to the biofilm from the beginning of periodontal multispecies biofilm development? These are challenges to be overcome in future studies.

The inflammatory response plays a crucial role in the tissue destruction occurring during periodontal disease and probiotics, in addition to exerting action in the colonization of pathogens, can modulate the exacerbated immune host response (31). In vitro studies using GECs (11, 12) and human macrophages (32) showed the downregulation of inflammatory cytokines when cells were challenged either with P. gingivalis or A. actinomycetencomitans and treated with lactobacilli, such as interleukin-1β, a cytokine involved in bone resorption under pathological conditions. Other cytokines/chemokines also presented reduced levels by La5 such as CXCL-8, GM-CSF, and TNF-α. This immunomodulatory response accompanied by the antibiofilm effect indicate that this probiotic strain is a potential candidate for adjunctive therapy in periodontal treatment.

Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis showed that using probiotics as an adjunctive therapy promoted a clinical attachment level gain and reduction of probing pocket depth at 3 and 12 months, which are the main clinical goals in periodontal treatment (33). In addition, a systematic review concluded that administering probiotics as an adjuvant treatment improved the clinical parameters and decreased the concentration of the main periodontal pathogens without causing any side effects (33).

To limit the use of antibiotics and the risk of bacterial resistance, as well as to avoid undesirable effects by repeated therapy, efforts to optimize therapeutic procedures addressing the microbial colonization and recolonization of the periodontal pocket are crucial. Probiotics seem to be a reasonable alternative and our study elucidates that the co-culture of L. acidophilus La5 in a multispecies biofilm is capable of reducing the red complex and increasing the Actinomyces complex, providing an exciting strategy for the control of dysbiosis. However, more studies elucidating their mechanism of action and the correct timing, quantity, and which strain to be used are still necessary.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

BB-S drew the project, planned the assays, and wrote the manuscript. MB planned and ran the assays and helped write the manuscript. GD-S, TM, AG, AR, and LA helped run the assays. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

MB was supported by scholarships from the Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; no. 2017/16377-7). GS and TM received a scholarship from the Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (CAPES). AG and AR received an undergraduate scholarship from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). LA pursued a scholarship from the Latin American Oral Health Association (LAOHA).

Conflict of interest

The author BB-S declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Armitage GC. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. (2004) 34:9–21. doi: 10.1046/j.0906-6713.2002.003421.x

2. Carrouel F, Viennot S, Santamaria J, Veber P, Bourgeois D. Quantitative molecular detection of 19 major pathogens in the interdental biofilm of periodontally healthy young adults. Front Microbiol. (2016) 7:840. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00840

3. Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T, Lambris JD. Current understanding of periodontal disease pathogenesis and targets for host-modulation therapy. Periodontol 2000. (2020) 84(1):14–34. doi: 10.1111/prd.12331

4. Sanz M, Herrera D, Kebschull M, Chapple I, Jepsen S, Beglundh T, et al. Treatment of stage I–III periodontitis—the EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol. (2020) 47(Suppl 22):4–60. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13290

5. Rosier BT, Marsh PD, Mira A. Resilience of the oral microbiota in health: mechanisms that prevent dysbiosis. J Dent Res. (2018) 97(4):371–80. doi: 10.1177/0022034517742139

6. Ren C, McGrath C, Jin L, Zhang C, Yang Y. The effectiveness of low-level laser therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: a meta-analysis. J Periodontal Res. (2017) 52(1):8–20. doi: 10.1111/jre.12361

7. Petit C, Batool F, Bugueno IM, Schwinte P, Benkirane-Jessel N, Huck O. Contribution of statins towards periodontal treatment: a review. Mediators Inflamm. (2019) 2019:6367402. doi: 10.1155/2019/6367402

8. Canut-Delgado N, Giovannoni ML, Chimenos-Kustner E. Are probiotics a possible treatment of periodontitis? Probiotics against periodontal disease: a systematic review. Br Dent J. (2021). doi: 10.1038/s41415-021-3624-5. [Epub ahead of print]34815484

9. Balta MG, Papathanasiou E, Blix IJ, Van Dyke TE. Host modulation and treatment of periodontal disease. J Dent Res. (2021) 100(8):798–809. doi: 10.1177/0022034521995157

10. FAO/WHO. Working group report on drafting guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food London. London: Ontario, ON (2022).

11. Albuquerque-Souza E, Balzarini D, Ando-Suguimoto ES, Ishikawa KH, Simionato MRL, Holzhausen M, et al. Probiotics alter the immune response of gingival epithelial cells challenged by Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Periodontal Res. (2019) 54(2):115–27. doi: 10.1111/jre.12608

12. Bueno MR, Ishikawa KH, Almeida-Santos G, Ando-Suguimoto ES, Shimabukuro N, Kawamoto D, et al. Lactobacilli attenuate the effect of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans infection in gingival epithelial cells. Front Microbiol. (2022) 13:846192. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.846192

13. Ishikawa KH, Bueno MR, Kawamoto D, Simionato MRL, Mayer MPA. Lactobacilli postbiotics reduce biofilm formation and alter transcription of virulence genes of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Mol Oral Microbiol. (2021) 36(1):92–102. doi: 10.1111/omi.12330

14. Shimabukuro N, Cataruci ACS, Ishikawa KH, de Oliveira BE, Kawamoto D, Ando-Suguimoto ES, et al. Bifidobacterium strains present distinct effects on the control of alveolar bone loss in a periodontitis experimental model. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:713595. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.713595

15. Miranda SLF, Damasceno JT, Faveri M, Figueiredo L, da Silva HD, Alencar SMA, et al. Brazilian red propolis reduces orange-complex periodontopathogens growing in multispecies biofilms. Biofouling. (2019) 35(3):308–19. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2019.1598976

16. Pingueiro J, Piattelli A, Paiva J, Figueiredo LC, Feres M, Shibli J, et al. Additive manufacturing of titanium alloy could modify the pathogenic microbial profile: an in vitro study. Braz Oral Res. (2019) 33(Suppl 1):e065. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2019.vol33.0065

17. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. (1998) 25(2):134–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02419.x

18. Socransky SS, Smith C, Martin L, Paster BJ, Dewhirst FE, Levin AE. “Checkerboard” DNA-DNA hybridization. Biotechniques. (1994) 17(4):788–92.7833043

19. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Dzink JL, Hillman JD. Associations between microbial species in subgingival plaque samples. Oral Microbiol Immunol. (1988) 3(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.1988.tb00596.x

20. Papapanou PN, Sanz M, Buduneli N, Dietrich T, Feres M, Fine DH, et al. Periodontitis: consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 world workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions. J Periodontol. (2018) 89(Suppl 1):S173–82. doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0721

21. Perez-Chaparro PJ, Goncalves C, Figueiredo LC, Faveri M, Lobao E, Tamashiro N, et al. Newly identified pathogens associated with periodontitis: a systematic review. J Dent Res. (2014) 93(9):846–58. doi: 10.1177/0022034514542468

22. Marsh PD, Head DA, Devine DA. Ecological approaches to oral biofilms: control without killing. Caries Res. (2015) 49(Suppl 1):46–54. doi: 10.1159/000377732

23. Miranda SLF, Damaceno JT, Faveri M, Figueiredo LC, Soares GMS, Feres M, et al. In vitro antimicrobial effect of cetylpyridinium chloride on complex multispecies subgingival biofilm. Braz Dent J. (2020) 31(2):103–8. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440202002630

24. Ishikawa KH, Mita D, Kawamoto D, Nicoli JR, Albuquerque-Souza E, Lorenzetti Simionato MR, et al. Probiotics alter biofilm formation and the transcription of Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence-associated genes. J Oral Microbiol. (2020) 12(1):1805553. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2020.1805553

25. Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. (2015) 15(1):30–44. doi: 10.1038/nri3785

26. Collado MC, Vinderola G, Salminen S. Postbiotics: facts and open questions. A position paper on the need for a consensus definition. Benef Microbes. (2019) 10(7):711–9. doi: 10.3920/BM2019.0015

27. O'Grady J, O'Connor EM, Shanahan F. Review article: dietary fibre in the era of microbiome science. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2019) 49(5):506–15. doi: 10.1111/apt.15129

28. Kolenbrander PE. Oral microbial communities: biofilms, interactions, and genetic systems. Annu Rev Microbiol. (2000) 54:413–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.413

29. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Dental biofilms: difficult therapeutic targets. Periodontol 2000. (2002) 28:12–55. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.280102.x

30. Colombo AP, Teles RP, Torres MC, Souto R, Rosalem WJ, Mendes MC, et al. Subgingival microbiota of Brazilian subjects with untreated chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. (2002) 73(4):360–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.4.360

31. Matsubara VH, Ishikawa KH, Ando-Suguimoto ES, Bueno-Silva B, Nakamae AEM, Mayer MPA. Probiotic bacteria alter pattern-recognition receptor expression and cytokine profile in a human macrophage model challenged with Candida albicans and lipopolysaccharide. Front Microbiol. (2017) 8:2280. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02280

32. Vale GC, Mota BIS, Ando-Suguimoto ES, Mayer MPA. Effect of probiotics Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus on antibacterial response gene transcription of human peripheral monocytes. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. (2023) 15(2):264–74. doi: 10.1007/s12602-021-09832-1

33. Ho SN, Acharya A, Sidharthan S, Li KY, Leung WK, McGrath C, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical, immunological, and microbiological shift in periodontitis after nonsurgical periodontal therapy with adjunctive use of probiotics. J Evid Based Dent Pract. (2020) 20(1):101397. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2020.101397

Keywords: subgingival biofilm, periodontitis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, bacteria, probiotics

Citation: Bueno MR, Dudu-Silva G, Macedo TT, Gomes APdAP, Rodrigues Oliveira Braga A, Aguiar Silva LD and Bueno-Silva B (2023) Lactobacillus acidophilus impairs the establishment of pathogens in a subgingival multispecies biofilm. Front. Dent. Med 4:1212773. doi: 10.3389/fdmed.2023.1212773

Received: 26 April 2023; Accepted: 13 July 2023;

Published: 31 July 2023.

Edited by:

Gaetano Isola, University of Catania, ItalyReviewed by:

Victor Martinez-Aguilar, Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan, MexicoFlorence Carrouel, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, France

© 2023 Bueno, Dudu-Silva, Macedo, Gomes, Rodrigues Oliveira Braga, Aguiar Silva and Bueno-Silva. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bruno Bueno-Silva, YnJ1bm9idWVAZ21haWwuY29t

Manuela Rocha Bueno

Manuela Rocha Bueno Gustavo Dudu-Silva2

Gustavo Dudu-Silva2 Arthur Rodrigues Oliveira Braga

Arthur Rodrigues Oliveira Braga Lucas Daylor Aguiar Silva

Lucas Daylor Aguiar Silva Bruno Bueno-Silva

Bruno Bueno-Silva