- 1School of Public Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Faculty of Medicine and Health, Menzies Centre for Health Policy, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3Faculty of Medicine and Health, Susan Wakil School of Nursing and Midwifery, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Aim: To explore the social experiences of Dual Sensory Impairment (DSI) for older Australian adults from the perspective of their family carers.

Background: DSI in older adults is a chronic progressive disability with varying combined degrees of vision and hearing loss. Prevalence increases with age and is particularly high in those > 85 years of age. Older persons with DSI experience a range of functional, social and emotional health issues and are considered a vulnerable group. Family carers fulfill complex multiple roles and provide the majority of care and support to this group. Caregiving and care-receiving are reported as demanding and stressful for both. Together, both spousal and mother-daughter dyads experience a range of social consequences as a result of DSI which are under-reported in the DSI literature.

Design: Qualitative study design using Grounded Theory Methodology (GTM).

Methods: This manuscript is part of a doctoral study. A total of 23 qualitative in-depth interviews with older Australians with DSI and their family carers were conducted over eighteen months. This manuscript reports on eight of those interviews (the caregivers) and explores the experiences of caregivers in the context of their relationship with their partner or parent with DSI. Data were analyzed using the inductive constant comparative method to systematically categorize emergent themes in order to develop a grounded theory.

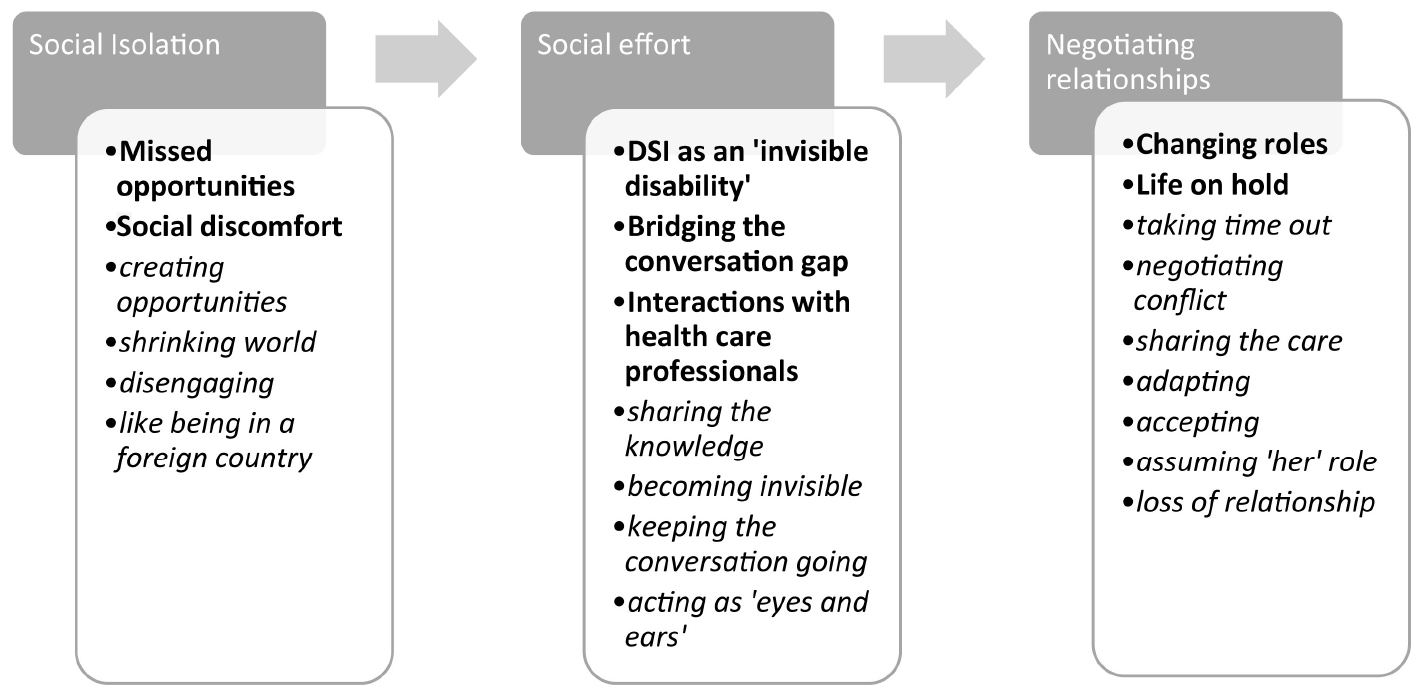

Findings: This qualitative study reports on the social experiences of the family carer in the context of DSI, and identified social isolation, social effort and negotiating relationships as key themes. These common social effects interrupt personal and external social networks and have a pervasive, often negative impact on social relations and the care relationship itself.

Conclusion: The experience of living with DSI is underexplored from a caregiver’s perspective. Few studies explore the perspective of the family carer and the impact of their family member’s DSI on their immediate relationships and social experiences. This report draws on the experiences of eight family carers and identifies three main themes that impact the quality of their dyadic relationship. While caring in a DSI context has clear parallels to caring in other health domains, the social relational aspects of DSI appear unique justifying further qualitative exploration of the family carers’ perspective.

Introduction

Improvements in health and social conditions and advances in medical technologies have increased life expectancy in developed nations (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2011; McPake and Mahal, 2017; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2018). Complex health and social needs in older Australians (defined here as over 60 years) have pushed family members into caregiving roles (Braun et al., 2009). In Australia, family carers often bridge the gap between residential aged care and caring in the home, fulfilling a critical role in supporting aged care services. They are pivotal to realizing popular preferences for aging in place and the key to meeting national aged care policies designed to keep older Australians at home in later life (Breheny and Stephens, 2012; Barken, 2017; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2019; Commonwealth of Australia, 2019, Royal Commission into Aged Care, Quality and Safety, 2019).

Caregiving is founded on a dyadic process, an interdependent relationship between carers and care-receivers (Lyons and Lee, 2018). The dyadic relationship involves complex interactions that can be stressful and strenuous to both caregiver and care-receiver (Sebern and Whitlatch, 2007; Lyons and Lee, 2018). In the context of chronic illness in older age, research studies tend to focus on either the caregiver or care-receiver, thus limiting our understanding of the mediating and shared influences of each individual within the dyad and their external social networks (Moon et al., 2017).

A rapidly expanding aging population means that specific age-related conditions, such as vision impairment (VI) and hearing impairment (HI) or loss, are increasingly prevalent among the elderly, with corresponding social and functional issues for the individual (Heine et al., 2002; Schneider et al., 2011). Together, these sensory losses are defined as Dual Sensory Impairment (DSI) (Saunders and Echt, 2007; Schneider et al., 2011; Schneider et al., 2014). As a poorly defined disability, DSI in older adults is a complex and progressive chronic condition, of varying degrees of severity, which presents affected adults with significant challenges.

Recent national and international policy attention (United Nations, 1991; World Health Organisation [WHO], 1999, 2002, 2011; Australian Government Department of Health, 2019) on the needs of the older population has generated interest in DSI as both a risk factor for other age-related conditions and a key driver of physical, social and mental health issues (Jaiswal et al., 2018). To date, while there has been increased research focus on DSI in older age, the influences and social experiences of family carers and their dyadic relationship in a DSI context has received little attention.

Drawing on the conceptual model developed by Berkman et al. (2000) of both macro and micro social network effects on health, the family carer can be seen as a provider of social support, as well as a facilitator of social engagement and a means of accessing resources and external support. Berkman et al. (2000) describe social networks as complex systems of social relationships that develop over a lifetime, within which the individual is embedded. It is generally acknowledged that these networks provide support and resources that are protective, and that network size matters in terms of “healthy aging” (van Tilburg and Thomese, 2010; Upenieks et al., 2018). Berkman et al. (2000) argue that social networks function at the micro-level through the provision of social support, social engagement and facilitation of access to external resources and that these micro effects are embedded in and shaped by the macro social context.

The individual and their relationships are the simplest deconstruction of social networks. Family carers are embedded in a broader social network which may provide opportunities for each individual in the caring relationship to derive benefits that improve quality of life. This micro-level social network of family carer and care-receiver provide a critical point of analysis in understanding how relationships may facilitate or limit access to external social networks.

The intersection of social experiences of both caregiver and care-receiver in relation to their external social networks and needs is an important context for exploring the social experiences of those with DSI and their family members. This research report draws attention to the social experiences of DSI from the perspective of the caregiver. As caregiving is frequently embedded in the spousal and mother-daughter dyadic relationships, often female (Solomon et al., 2015), exploring the caregiving perspective provides a powerful means to better understand the key issues that may facilitate or limit social participation and quality of life for this caregiving group.

Background

In Australia, prevalence of DSI was assessed through the Blue Mountains Eye Study (BMES) with prevalence ranging from 6% (in those older than 55 years), rising to 26.8% in those aged greater than 80 years (Schneider et al., 2012). Despite the high prevalence of DSI in the older Australian population, and unlike most other age-related health conditions, this disability is under reported in health settings (Dullard and Saunders, 2016), poorly acknowledged in policy development (Jaiswal et al., 2018; Simcock and Wittich, 2019) and is a neglected dialogue in the public arena. This lack of attention to DSI in the health care setting compromises care and reduces autonomy for those with DSI (Dullard and Saunders, 2016). Inconsistent approaches to DSI at a primary care level reflect a normalization of DSI which limits opportunities to participate and reduces access to services (Heine and Browning, 2015; Wittich et al., 2016). We have found that these experiences are shared by family carers, particularly in situations where other forms of social support are limited.

DSI has a spectrum of severity, ranging from mild VI and HI through to severe vision and hearing loss. Acquired DSI in the older person often co-exists with multiple other chronic health conditions, which, in effect limits social participation through interruptions to mobility, day to day functioning (Jaiswal et al., 2018) and communication (Heine and Browning, 2002). Losing the ability and self-confidence to navigate unfamiliar environments limits independence and reduces self-confidence. Fletcher and Guthrie’s (2013) qualitative study of seven participants with DSI, identified the significance of this in relation to day to day functional activities (such as shopping), recognizing social isolation as one consequence of increasing dependence. Jaiswal et al. (2018) scoping review of deafblind literature noted that impaired mobility in older adults with DSI impacted social participation in a wide range of activities. Communication difficulties have been reported, both one on one (Fletcher and Guthrie, 2013) and in group settings, with feelings of embarrassment and stigmatization contributing to isolation and depression (Capella-McDonnall, 2005; Schneider et al., 2011; Heine and Browning, 2014). The published research suggests that these consequences of DSI outweigh the sum of its constituent parts and that the reported social experiences have significance beyond functional impact (Saunders and Echt, 2007). Research to date has demonstrated associations between DSI and multiple social, emotional and cognitive effects (Heine et al., 2002; Heine and Browning, 2002; Capella-McDonnall, 2005; Chia et al., 2006; Schneider et al., 2011; Kwon et al., 2015; Yamada et al., 2016; Lehane et al., 2017a,b; Maharani et al., 2018). Studies have consistently demonstrated associations between DSI, cognitive decline and dementia (Lin et al., 2004; Hwang et al., 2019). Luo et al. (2018) cross sectional study of a nationally representative population of Chinese older adults with single vision loss, single hearing loss or DSI determined that the prevalence of dementia was highest in those with DSI although the pathway between DSI and dementia is unclear. Aging, and its association with smaller social networks (Kemperman et al., 2019) means that the combined effects of impaired mobility, limited independence, poor communication and cognitive impairment are more visible to the family carer, poorly understood by both caregiver and care-receiver and have a pervasive impact on the interpersonal and intrapersonal relations of both (Brennan et al., 2006; Heine and Browning, 2014; Lehane et al., 2019). This suggests that addressing these heterogeneous needs is complex (Fletcher and Guthrie, 2013; Simcock, 2017; Jaiswal et al., 2018) and requires an understanding of the experiences of DSI from both caregiver and care-receiver perspectives.

As the consequences of DSI are often intangible, those with DSI are not easily characterized as meeting formal aged care criteria despite significant functional limitations (Cimarolli and Jopp, 2014). Complex needs may be considered from a range of care dimensions: from assistance with activities of daily living (Brennan et al., 2005) through to social and emotional support (Heine and Browning, 2002; Bodsworth et al., 2011). These needs, for the most part, are met by family carers, who in this context are defined as family members who provide regular and ongoing assistance (Dyke, 2013; Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015). In a DSI context, family carers are often a spouse or close adult family member, such as a daughter.

Research on caregiving dyads generally focuses on spousal relationship quality and according to Lehane et al. (2018a) research and consistent with previous studies (Lehane et al., 2017a,b; Hofsoe et al., 2018) spousal relationships in a DSI context may experience significant strain. Using the relationship intimacy model, this study measured relationship satisfaction, perceived support and psychological well-being in 45 spouses of older adults with DSI, demonstrating that interpersonal communication and perceived support were associated with improved psychological well-being. The mother-daughter caregiving dyad is less well understood and relatively under-explored in the published research. Solomon et al. (2015) explores both qualitative and quantitative research on mother-daughter care relationships in their systematic review. This research suggests that positive mother-daughter relationships increase resilience, protects against the more stressful aspects of caregiving, and may play a significant role in supporting aging parents to stay at home (Solomon et al., 2015).

Irrespective of the nature of the care-giving relationship, the adoption of the care-giving role in a potentially already strained relationship will impose additional interpersonal tensions and suggests that understanding DSI as a collective experience, as suggested by Lehane et al. (2018a) has the potential to offer more targeted support strategies for the family carer and improve quality of life for both. Given that family carers assume the bulk of care-giving responsibilities, this lends weight to the current focus of our study where the effects of DSI are considered a shared experience.

While it is widely acknowledged that family carers in general experience reduced subjective well-being (Senses Australia, 2013; Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015, 2018), we have limited understanding of caregiving in a DSI context. Understanding these microlevel social relations from a caregiving perspective is critical to identifying the complex social consequences of DSI (Lehane et al., 2017a; Hovaldt et al., 2019) with further exploration of the novel aspects of the caregiving role potentially providing explanatory power in determining future needs. This paper reports on the unique social experiences of the family carer in the context of DSI.

Materials and Methods

This paper presents findings from qualitative interviews of the eight (8) family carers, guided by the following research questions:

1. How does DSI affect the social experiences of older Australians and their family carers?

2. How do these experiences shape the way family carers identify, maintain and adapt their social networks and roles in a DSI context?

Design

Given the exploratory nature of this study, Grounded Theory Methodology (GTM) was considered an appropriate research approach with its main tenet to generate or discover theory (Glaser, 1992; Dey, 2007). We utilized Charmaz’s (2014) constructivist perspective that considers complex individual social experiences. Constructivism provides a flexible but rigorous method of enquiry and recognizes subjectivity and the role of the researcher in constructing and interpreting data. Participants willingly shared their stories thus aligning with the constructivist position of interaction, sharing perspectives and co-construction of knowledge to better articulate the unique caring processes inherent in the DSI context.

Recruitment

Recruitment of family carers for this study was conducted simultaneously with recruitment of those with DSI for the broader doctoral study. As part of the previous Vision-Hearing Project (2009–2013), MD and JS had an established network of contacts that facilitated access to this cohort via Vision Australia (VA), the leading blindness and low vision support service in Australia. Permission to access data of potential participants was approved by VA and regular meetings with VA staff ensured appropriate means of contacting participants, either during clinic appointments or through suggestion by staff. The regular presence of MD at VA clinics meant that face to face contact could be facilitated quickly and study information given to both those with DSI and their carers. This was followed up by telephone contact by MD. Information flyers were disseminated in large, bold font and educational sessions with VA staff meant that clear information about the study was conveyed to clients. As recruitment slowed, site recruitment was extended to include local (Sydney, NSW) Vision Impairment community support groups. These support groups were chosen based on the older age range of the participants and through recommendation by VA considering the number of attendees who experienced hearing loss in combination with vision loss. Many attendees came with their family carer. Following a presentation of the study aims to attendees by MD, recruitment increased significantly and was finalized early 2019.

There are significant challenges to recruiting older persons with sensory loss to research studies. First, communication challenges meant that face to face contact was important as contact by telephone cold-calling was often met by suspicion and outright refusal. VA was considered a “safe space” by this older cohort so the presence of MD on site provided an opportunity to build a relationship with those with DSI and their family carers and explain the study aims clearly. This potentially drove better participation in the study. Second, accessibility was a key concern with potential participants and their carers reluctant to commit to the study if interviews were conducted outside of their home. Interviews with participants were conducted at a venue of their choosing, most often the participant’s home. Family carers were key to facilitating study participation for those with DSI and were eager to be included in the study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in this study, family carers had to reside with their parent or partner with DSI and provide personal support and care to those with DSI, in accordance with current Australian legal definitions of an unpaid carer (Australian Government, Carer Recognition Act, 2010). Their partner’s or parent’s DSI was defined as a combination of vison loss (documented in VA records) and self-reported hearing loss that met all three criteria of (1) difficulty hearing in a crowded room, (2) difficulty hearing high pitches, e.g., children’s voices, and (3) difficulty with accents. Data was accessed through VA with participants written permission. For those with DSI, criteria for eligibility to participate in the research interviews included: age greater than 60 years, with documented VI and self-reported HI. Older Australians with DSI and their family carers were sampled for their insights on their experience of DSI. Details of the family carers (n = 8) are provided in Appendix Table 1.

Participants

The cohort of family carers was made up of both daughter carers (n = 3) and spouse carers (n = 5). Carers ranged in age from 50 to 93 years. Daughter carers were younger, as expected and all three were in either part-time employment or had voluntary work commitments. These family carers’ demographic details such as age; living arrangements; relationship to participant with DSI and other health issues are detailed in Appendix Table 1.

Data Collection

This manuscript details the findings from analysis of the experiences of eight (8) family carers who were interviewed as part of a doctoral study which overall comprised of 23 in-depth face to face qualitative interviews. Of the total 23 interviews, sixteen participants formed a dyad of family carer and partner/parent with DSI. Family carers (n = 8) were interviewed individually (with the exception of one family care who chose to be interviewed with spouse). The remaining seven interviews were from individuals with DSI and the findings of these interviews will be detailed in future publications.

The Interview

This study opted for intensive interviewing to collect data. Interviews were conducted over an 18-month period in participants’ homes and were structured around five core guiding themes (Appendix Table 2A), using the U.K. Office of National Statistics [ONS] (Siegler, 2014) principles of social capital theory as sensitizing concepts to guide interview direction (Carter and Little, 2007; Charmaz, 2014).

On average, these interviews with family carers lasted approximately 1 h and were recorded and transcribed verbatim with participant permission. As family carers were already known to MD through previous interviews with their partner/parent with DSI, these interviews were relaxed and conversational in nature. Interviews were conducted individually in seven out of eight interviews, thus ensuring that family carers were in a position to discuss their relationships and experiences openly. The one interview conducted as a dyad was based on the personal preference of this spousal care-giving dyad. As detailed above, questions were formed around the ONS social capital principles with a typical interview starting with a broad opening question, such as “tell me when you first noticed your partner/parent’s sensory loss.” This allowed family carers to tell their “stories” and, while specific guiding questions were used (see Appendix Table 2B), the interview followed constructivist GTM principles of being “open-ended yet directed, shaped but emergent, and paced yet unrestricted” (Charmaz, 2014, p. 85). This enabled the interviewer (MD) to revisit areas of interest to the study in more detail, and to clarify, in real time with participants, seemingly contradictory or inconsistent points. An example of a question and answer are detailed in Appendix Table 2B.

Written notes, taken during the interview, offered an opportunity to compare the recording to comments written. The immediate post-interview routine of listening to the recording, comparing written notes and writing further memos became a critical phase between data collection and analysis. The analytical process of creating memos is an essential part of constructivist GTM, forming part of the data collection, furthering analysis and prompting researcher decision making (Carter and Little, 2007; Charmaz, 2014). Thus, informal and detailed memos in the form of ideas, events, thoughts, reflections or interesting points discussed, were documented if sensed to be relevant to the study questions.

Data Analysis

In keeping with constructivist GT methods for analysis and as detailed above, interviews were in-depth, often conversational in nature and described as “permission to vocalize” and “work through” the complex, but often hidden, social experiences of participants. Construction of meaning in relation to the study’s area of inquiry was achieved through data coding and an inductive identification of themes (Carter and Little, 2007; Charmaz, 2014). Initial (line-by-line), focused and theoretical coding methods specific to GT methodology was employed to analyze data (Charmaz, 2014). Coding was a shared process between all researchers (MD, JS, HMcK, JG). MD completed the initial line by line coding to sort, synthesize and categorize the main recurring codes and these codes and their meaning were discussed at regular supervision meetings. This was an iterative process with constant checking of data necessitating regular comparison and discussion between the supervision team of transcribed data and memos to identify categories. In this way, subsequent interview questions were refined to explore specific concepts in greater detail. Searching for common themes early in data collection in conjunction with MD’s detailed memo writing provided opportunities to explore emerging concepts in more detail, identify gaps and note implicit and explicit points conveyed by the data (Tie et al., 2019). A constant comparative approach identified, compared and defined common themes to build theory that remained “grounded” in the data. For example, early identification of the theme “social effort” occurred through Ted’s interview, where he discusses his partner’s difficulties engaging socially:

But new people, it’s hard to meet new people and it’s hard to form friendships with them because Ruth can’t see who she’s talking to and she kind of loses interest in that. If she was in a group, she knows so and so’s talking but all she sees is a bunch of blurs and she can’t join the conversation. That’s the trouble. It is hard for her. (Ted, carer to Ruth)

This response suggested that this was an issue worth pursuing in future interviews. Ted’s focus on this particular issue was repeated several times in response to theme 3 (Appendix Table 2A) questions. In this way, common themes were explored until no new insights were evident during interviews and we could conclude that theoretical saturation had been reached.

Ethics

Ethics approval for this study was obtained through the Human Research Ethics Committee at The University of Sydney, NSW, Australia (HREC 2014/897). Written ethical approval for site recruitment was obtained through Vision Australia and at each individual Vision Impairment community meeting. Ethical approval included informed participant consent, including publication of deidentified narratives and information about the study in large font.

Findings

Several themes relating to the social experiences of the caregiver and care-receiver were identified in analysis, representing a range of participant perceptions. This section of the paper discusses three of these themes, as seen in Figure 1: social isolation, social effort and negotiating relationships. These themes emerged consistently from each carer’s narrative and represent experiences that reflect both choice and consequences of their circumstances.

The three themes detailed in this manuscript were selected from a total of six major themes from the analysis of family carers’ data. The selection of these three themes was based on word count limitations of this manuscript and were chosen as representative of both daughter carer and spousal carer experiences. The remaining themes will be detailed in future publications.

Social Isolation

Social isolation was experienced by both caregiver and care-receiver. All participant carers recognized their own need and that of their loved one to remain socially connected to any extent possible. Circumstances often presented a choice to either engage socially or an opportunity for quiet time and there was not always alignment between caregiver and carereceiver in their responses to the available social opportunities. Opportunities to engage in activities with others became increasingly unavailable, with smaller social networks, safety concerns and disinterest frequently cited reasons by those with DSI. Caregivers were generally more socially engaged than their partner or family member, but social interdependence restricted opportunities to socialize. Social participation, however, small, was meaningful for caregivers, because it reduced feelings of confinement. For example, Eve explained that even shopping locally presented social occasions to engage beyond the dyad and social opportunities for both her and her mother:

They [i.e. shopping trips, casual social encounters etc.] created opportunities to have conversations, at the check-out in the supermarket and things like that, [that] are a big part of the social interaction. You know they were really 99% of the social interaction. So, if they go, you know the world kind of shrinks. (Eve, carer to May)

Missed Opportunities

There were times when Eve had to make choice about the best use of her time and sometimes her choices were not in her mother’s best interests, meaning her mother potentially missed out. “Missed opportunities” was dichotomous: on one hand some of these activities provided encouragement to participate for both Eve and her mother but on the other hand also created opportunity for caregivers to have “time out,” even though during this time out they may well be carrying out practical caring-related activities such as housework or shopping. This situation was particular to daughter carers, time constrained by their own activities in addition to providing care for their parent with DSI. They often chose to miss potentially valuable social opportunities as their time was limited. Karen, daughter and carer for mother, Ina, stated as an example:

I’m very conscious that I should be doing things like taking her out to the shops to let her do the shopping. You know, those kinds of [social] things, but that’s even more of the day, you know. (Karen, carer to Ina)

Both Eve and Karen’s preference to focus on the practical aspects of care that separated them, albeit temporarily, from their other care duties, provided welcome respite.

Social Discomfort

As noted above, there was often a lack of alignment between the expectations and desires of the caregiver and care-receiver. This situation would often lead to feelings of discomfort or distress for both and often led to communication breakdown. Poor communication and misunderstanding often led to conflict, resentment and offense. Ted, who cared for his wife, Ruth, voiced his frustration at what he saw as Ruth’s apparent lack of effort. Ruth felt increasingly disabled by her DSI and preferred to stay at home where she felt safe; Ted on the other hand wanted her to make an effort:

There’s no point going on all these mystery tours and things, she can’t see so what’s the point of going? There’s nothing you can do. But there’s even blind people out in the world that can hear something, they’re totally blind but they still get around. You’re not totally blind so you could maybe make an attempt to do something. (Ted, carer to Ruth)

Some caregivers viewed social disengagement as a result of apathy rather than a consequence of DSI; a situation that could make the caregiver feel resentful and also lead to resentment on the part of the care-receiver. For example, in Ted and Ruth’s case, they often found themselves in a less than optimum situation because of their mismatched expectations and needs. Ted felt that he could not go out, while Ruth’s preference was that he did, creating discord related to personal boundaries. Ted described his reluctance to leave Ruth on her own:

If I go away and leave her, anything she needs, she can’t see to get it. (Ted).

Ruth withdrew, choosing instead to pursue solitary hobbies (e.g., listening to her ‘Daisy’, a talking book) rather than engaging with her husband:

I’ll leave you alone for hours (Ruth).

Their forced proximity created discomfort for both, while their inability to communicate their own expectations disguised complex emotions.

Social discomfort was often evident within the dyad, with day to day social encounters presenting challenges to both as they tried to engage with each other and their external social networks. In the interviews, caregivers frequently described concerns about embarrassing social encounters and the frustration they experienced.

Spousal carers who shared the same social network with their partner, were mostly at pains to maintain these networks as they recognized the importance of maintaining their social engagement. Family carers had a vested interest in maintaining these social networks, both as a means of support for themselves and also as social opportunities for their partner or parent, which they found helpful.

When their opportunities for social participation were reduced many carers felt excluded from “normal” social activities. Local community VI groups, while not specific to DSI, provided relief to carers: The researcher initially met Sarah at one such group with her mother, Ina, who has severe HI and moderate VI. Despite Ina’s significant communication challenges and clear lack of enthusiasm for these outings, Sarah continued to engage in this activity describing them as support for herself and a relief from the communication strain she experienced when alone with her mother:

You have to basically modify your whole way communicating, it’s like being in a foreign country and you have to kind of more or less think that the other person is, [you know], not able to understand you…so it is a constant strain. (Sarah, carer to Ina)

The theme of social isolation represents experiences of caregivers that are both personal choice and also a consequence of their circumstances. For the caregiver, these social situations were described as hard work and tiring, particularly for older carers.

Social Effort

In an attempt to reduce social isolation or at least keep it at bay, all caregivers engaged in significant social effort. This was required because of the pervasive impact of DSI on everyday social participation and engagement, with the effort inevitably leading to increased fatigue as well as social withdrawal for both carer and their partner/parent.

Within the broad theme of social effort, we have identified the following sub-themes: DSI as an invisible disability and interactions with health care professionals.

DSI as an Invisible Disability

DSI was described by family carers as an “invisible disability” in that the absence of physical signs of disability meant that others would expect those with DSI to be able to function as “normal” in social circumstances.

The invisibility of DSI underpinned the need for a repeat of the “same story” during multiple social encounters. This constant need for “knowledge sharing” was seen as a protective and significant aspect of each carer’s role, but also contributed to communication fatigue. Gail, the wife and carer of Clive, (a retired professional with DSI and active in the Vision Impaired group). Gail explained:

You have to actually tell them [about DSI] and remind people to speak up…people just assume everyone’s the same. (Gail, carer to Clive)

She described common communication adjustments she made to create meaningful interactions for her partner, how tired she became of repetitively “sharing the knowledge” and the consequences of this for her:

He doesn’t talk anymore much, because he doesn’t know whether they’re talking to him, unless they use his name, he’s unaware they’re speaking to him, so he might ignore people and so on. And in the end, I noticed people weren’t even bothering him to talk, so now I refuse to go. Because I don’t think it’s fair to Clive. (Gail)

The effects of “invisibility” created a unique role for caregivers as social facilitators and protectors. Each caregiver saw the potential to improve their family member’s quality of life through facilitating social interactions, but they also acknowledged the effort involved in constantly “sharing the knowledge.”

Social facilitation or “keeping the conversation going” was a complex process involving empathic understanding and reading microlevel social interactions and nuances. This involved different strategies to maintain engagement in the interaction. Caregivers adapted the social constructs of conversational norms to reduce the effort required so that those with DSI were able to actively participate, although this increased the effort required of carers. As Gail explained:

It’s a strange thing, but you’ve really got to hone-in on them and being aware of it I suppose, I can do that. I can bring them back into the conversation and Clive will pick up and then I’ll include Clive. (Gail)

“Bridging the [conversation] gap” reflected carers’ efforts to protect their family member. Recognizing the complexities of many social interactions, carers felt the need to respond on behalf of their family member or intervene to “keep the conversation going.” This attention to detail involved effort and their ongoing presence for even the simplest social interactions. Communication disruption was common, with caregivers highlighting the one-sided nature of the conversation. Caregivers were constantly on guard to interpret and respond to both implicit and explicit social cues, often resulting in complex, fractured conversations which were both frustrating and tiring.

It was just so much of a one-way street, plus this is not normal, our situation is not normal. (Sarah, carer to Ina)

While both mother-daughter and spousal dyads experienced similar frustrations, their responses varied. Daughter carers (Karen, Sarah, Eve) tended to offer a solutions-based approach to creating social opportunities for their parent, which at least resolved some of the frustration. By engaging in external groups or networks they were often able to shift the social focus from themselves to others. Sarah actively encouraged her mother, Ina, to join groups:

She really loved it, because it’s not like sitting in front of somebody having to talk; you don’t have to talk, you just participate. (Sarah, carer to Ina)

External groups, such as activity-based groups, were not necessarily chosen for specific services for DSI. Instead, groups, such as guided exercise programs, were chosen that offered an opportunity to participate with others in a non-conversational informal environment where those with DSI felt comfortable and safe. All daughter participants expressed some frustration in identifying such opportunities but persisted as they felt this was a valuable opportunity for their parent:

Mum really enjoys the outings (VI support group) because they know enough about her disability to know what she needs. (Sarah)

In contrast, spousal carers, tended to adopt a more passive approach, meaning their social interactions reflected their partners’ wishes and decreased accordingly, often resulting in conflict:

On Tuesdays over a period of years now, he’s been going and meeting with a group of men which he has probably told you about. Basically, every week now I have to say “Are you going [to the group]?” and he says, “No, I don’t want to go, I can’t hear what they say, I don’t want to go.” And I have to sometimes get angry, then I feel guilty. (Mary, carer to Jim)

Interactions With Health Care Professionals (HCP)

Social facilitation and protection were particularly evident during health care encounters where the capacity for misunderstanding had a potentially significant impact. Interactions with health care professionals (HCPs), particularly at a primary care level, are more frequent with age and considered by many older persons a regular source of supportive social interaction. However, some caregivers described these interactions as complex and frustrating. Negative experiences originated from multiple issues: from HCPs excluding their family member with DSI in conversation to poor communication on the part of HCP’s and health literacy issues for carers and their family member. This was common, for example, when signing legal and informed consent documentation. These tense and often complex health care encounters emphasized the dependence experienced by those with DSI and the need for caregivers to act as the “eyes and ears,” (to advocate), while negotiating privacy concerns versus potentially missing key health information.

Mary, and her husband (a retired health professional), described a series of negative health care experiences during a recent hospitalization. Mary highlighted health care professionals’ poor communication skills with potential for misinterpretation of key health information being the main concern. This necessitated her attendance at consultations:

……we have been to specialists and I go with him now which I never ever used to have to do because he was quite capable. But now I have to go, and he always looks towards me to answer the questions, … and I know I try to refer to him. (Mary, carer to Jim)

Mary described her distress at the “diminished” version of her husband (“he just sits”) and the new responsibility of protecting him during these health care encounters.

In addition, appropriate services were not readily accessible for this cohort, for example, support groups that catered for DSI participants. Hospitalizations, when they did happen, separated those with DSI from their caregiver, creating feelings of vulnerability and anxiety for both. Advocacy was often difficult in the hospital environment, which participants in this study considered hostile, particularly in view of the perceived poor communication skills of many HCP’s and thus potential for misinterpretation, not only for those with DSI, but also caregivers. Mary recounted her experience of her husband’s hospital admission, where she attempted to alert HCP’s to her husband’s sudden and significant visual deterioration. Despite her repeated concerns, she felt ignored, until tests acknowledged further visual loss due to infection:

I was really upset by that. Because no one was listening when it happened, and they didn’t seem to see the importance of eyes, even though he clearly couldn’t hear. (Mary, carer to Jim)

Mary’s account was not unique, with these findings suggesting that the hospital environment increases vulnerability in those with DSI, in the absence of an appropriate advocate.

Social effort describes complex social situations where increasing effort was required by the caregiver to facilitate social participation for their partner or parent with DSI.

Negotiating Relationships

This increased social effort was not only required to access networks beyond the dyadic relationship, but also reflected the effort required to preserve this relationship. In this study, caregivers drew attention to the impact of the social effort outlined above on their dyadic relationship, and the subsequent need to make significant changes to the dynamics of their relationship. Negotiating relationships encapsulates the process aimed at achieving compromises that involved both caregiver and care-receiver as they sought to optimize their “new normal.” For family carers, this process provided a mechanism for adapting to changing roles whilst attempting to preserve their personal identity within an interdependent relationship.

Changing Roles

There was implicit understanding by both caregiver and care-receiver of the inevitability of role change within the dyad. Family carers described an “increased responsibility” and their need to “assume other roles” such as “mothering” or “communicator” within the family. These changing roles were not explicitly communicated within the dyadic relationship nor always welcomed by either caregiver or care-receiver and often contributed to increased conflict.

Most carer participants did not refer to themselves as “carers” unless specifically asked, referring instead to their changed circumstances, roles and responsibilities:

I’m a bit like a little mother, really. I sort of mother him now. Sometimes in a group situation, you need eye contact. But sight-impaired people don’t have that, you know, they just sit there and when there’s no response, people walk away. (Gail, carer to Clive)

Role change required complex adaptation and those carers who experienced greater difficulty adapting to these changed circumstances described both isolation and social disengagement. They described “feeling trapped” and referred to conflict within the relationship because of the “loss of companionship” and isolation within the relationship. Some carers, like Mary, experienced discomfort in their new role as advocate and protector. Mary’s health care encounters (described above), demonstrate role change which effectively disempowered her husband and shifted the balance of power to her. For others, like Paul, his role as carer for wife Betty, was an opportunity to give back. Betty has severe DSI and is immobile meaning their opportunity to participate socially was particularly limited. Paul’s acceptance of his changed role was described as an opportunity to reciprocate for the many years that Betty had cared for him and the family as he pursued his career:

It’s my turn to give back. (Paul, carer to Betty)

The ability to adapt to new roles varied. The resilience of those with DSI often provided the stimulus for adaptation to this change. For some, disability presented opportunity. Gail’s retired partner, Clive, created an alternative career through DSI, which preserved his diminishing independence, located him in external supportive networks and provided a sense of purpose. For Gail, seeing her partner adapt to their changed circumstances provided the incentive to “get on with her own life” in parallel to her role as carer:

I have to come up with ways of how to deal with this. Because he accepted it really well and got on with his life, he wasn’t sitting at home moaning about it, I probably did then get on with my life. I didn’t stop. (Gail, carer to Clive)

Life on Hold

The description of caring responsibilities suggested a ‘life on hold’ for many carers. Carers described a role that left little time for self, with several resenting the increased dependence of their family member. Carers described the “missed opportunities” inherent in their “shrunken world” that limited their own social opportunities, as well as that of their family member. Opportunities for “sharing the care” such as the experiences of sisters, Karen and Sarah, with their mother Ina, were rare and often limited by the strength of carers’ external networks, their ability to negotiate extra help from family and friends and acceptance by the care-receiver. For Eve, caring for her mother, May, was an isolating experience. As an only child, she assumed sole responsibility for her mother’s care with no opportunity to outsource care:

It’s really hard to find anyone that mum will accept, she wouldn’t have anyone else but me. Ideally, I need the help. (Eve, carer to May).

While the spousal and mother-daughter dyadic relationship itself was often protective for those with DSI, caregivers experienced little to no specific formal support. They had difficulty accessing external resources, experienced exhaustion and critically, could not see their situation improving in the short or long term.

Together, these three core themes of social isolation, social effort and negotiating relationships illustrate the impact of DSI on the caregiver and their relationship with their loved one.

Discussion

This paper explores the social experiences of DSI for the older Australian and their family carer from the carer’s perspective. The findings presented here address the microlevel social effects of increased social effort on relationship dynamics for the family carer and how this impacts their access to external social networks and their relationship with their family member with DSI. In this study we found family carers experienced social isolation by way of missed opportunities and social discomfort. Carers reported social effort connected to the invisibility of DSI and the need to constantly bridge the conversation gap and this was particularly significant in encounters with health care professionals. Due to changing roles and a sense of “life on hold,” carers had to work to negotiate their relationships with their family member with DSI.

While some comparisons can be drawn with previous research that address interpersonal relational experiences in a DSI context, we consider the experiences of social isolation, social effort and relational change to be compounded by the additional responsibilities of caregiving. As such, this may be a significant factor in both the maintenance of external social networks and the quality of interpersonal relationships for both family carer and the individual with DSI. Social networks are critical to the caregiving role as external social networks convey support that both protect health and foster healthy aging. Our findings support the functionality of Berkman et al. (2000) conceptual framing of micro social network effects on health and suggest that improving social support for family carers in a DSI context may reduce perceptions of social effort and improve interpersonal relationship quality.

Our findings highlight increasing isolation despite ongoing social effort by the family carer and that there are consequences of this for both immediate and external social networks. Changes in size and construct of social networks associated with aging (van Tilburg, 1998; Antonucci et al., 2013) are particularly relevant in a DSI context. Heine and Browning (2002) highlight the poor communication, increased social fatigue and functional difficulties experienced in DSI which may contribute to diminishing external networks. While network size has importance for the older person, changes to network diversity, i.e., the quality of networks, has significant implications for the caregiving role (Tolkacheva et al., 2011). Other researchers have noted the barriers to social participation and difficulties in maintaining social connections from the perspective of the individual with DSI (Arndt and Parker, 2016; Jaiswal et al., 2018). However, these social barriers appear to be also present for caregivers, often elderly themselves (Cloutier-Fisher et al., 2011). This draws attention to the impact of increased social effort on family carers’ relationships in a DSI context in a number of ways. First, increasing strain will have an impact on the strength and quality of interpersonal relationships (noting the differences of relationship status in our participant carers). Second, on a background of poor communication, frustration and relationship conflict, the level of effort required to maintain social participation beyond the immediate relationship, is likely to limit access to external social networks and the potential reciprocal benefits suggested by Berkman et al. (2000) conceptual model of “downstream” effects.

Network diversity changes with age in response to the needs and life stages (such as retirement status) of the older person (Suanet et al., 2020). van Tilburg’s (1998) original network research describes the deployment of “helpers” in response to health needs (often family members), with these changes to aging social network constructs reflecting the primacy of health needs over social needs. Our findings suggest that when these needs are “invisible,” or not strictly physical, these broader networks may be reduced rather than replaced, effectively meaning that the spousal and mother-daughter dyadic relationship can become very isolated. Under these circumstances, caregiving can become lonely, with difficulty clarifying the needs of the older person with DSI, given the prevalence of co-morbidities in this age-group and the compounding effects of DSI on multiple life domains.

Contrary to societal assumptions about the social capital invested in family caregiving relationships, it is not necessarily the case that in older age there is always going to be a desire on the part of one member of the dyad to care under difficult circumstances for the other, more vulnerable partner. In effect, not all social ties are beneficial (Stephens et al., 2011) or voluntary. Cloutier-Fisher et al. (2011) further suggest that such relationships, in the presence of additional caregiving responsibilities, can in fact increase isolation, becoming injurious to both caregiver and care-receiver. This can undermine formal policy approaches related to home-based family care (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2019; Commonwealth of Australia, 2019, Royal Commission into Aged Care, Quality and Safety, 2019) and serves as a reminder of the importance of external social networks to continued social participation. These networks can be a critical pathway for both caregiver and care-receiver in a DSI context, often enabling access to support that potentially reduces isolation.

Several researchers have reported on the potential for reduction in psychological distress in the presence of spousal support (Lehane et al., 2017a) and acceptance of DSI in their partner/spouse (Hofsoe et al., 2018; Lehane et al., 2018a,b). While our findings do not report on measured relationship satisfaction, they do suggest that role change to caregiver creates additional complexity within interpersonal relationships. Our participants describe varying difficulties renegotiating this role within the relationship with substantial variations in dyadic dynamics between spousal and daughter family carers. Westaway et al. (2011) report on the increased burden of caregiving in DSI contexts supports our findings of increased social effort in caregiving as a contribution to overall caregiving burden. Within our participant cohort, daughter carers and one younger spousal (female) carer, reported some success in maintaining external social networks (and therefore additional support), and communicated less conflict within the relationship as a result of this. This access to external social resources and the positive benefits derived, aligns with Berkman et al.’s (2000) model and may have a role in improving relational satisfaction between care-giver and care-receiver. In contrast, the narratives of older spousal carers, with reduced access to broader networks and communication challenges, highlight ongoing poor communication and misunderstanding. Age and frailty of most spousal care-givers limits opportunities for social support and this situation can exhaust the caring capacities of caregivers. This situation can frustrate the carer’s attempts to negotiate new roles or accept the changes that DSI brings to the relationship.

Lehane et al. (2018b) study of 122 adults with sensory loss presents a dyadic perspective of the mediating role of acceptance of DSI within the spousal relationship using a family systems-illness model. Self-acceptance of DSI was considered important, but critically, the role of spousal acceptance was central to adjustment to the challenges of DSI. Our findings suggest that the change of role from spouse to family carer can create additional strain and negativity thus limiting the potential for acceptance. Age, the presence of comorbidities and the progressive nature of DSI suggests that this may be challenging for those in the oldest-old age category particularly. Our participants’ narratives reflect a mutual tendency to minimize DSI in line with public misconception of DSI as a “normal” feature of aging (Huddle et al., 2016). In this context, there is a reluctance to communicate the true effects of DSI within their immediate relationship and the multiple combined effects of DSI leave family carers and their family member exhausted and isolated but unclear why they are feeling this way. Adjustment to these changes, or indeed acceptance of DSI for our family carers is then much more complex and appears at least partially dependent on their ability to access support external to their relationship. In the current study, only one of the five spousal family carers (family carer narrative, p. 26) refers to mutual acceptance. This participant described the rich social network created by her partner in his disability support group and the benefits this presented to her, both as an individual and within the partnership. We suggest there is value in facilitating supportive external social networks that may positively influence acceptance of DSI for both family carer and their partner or parent.

The complex negative consequences attributed to DSI range from functional to social and influence independence (Brennan et al., 2005; Tiwana et al., 2016; Simcock, 2017). Dependence and reduced autonomy may have broad implications for engagement in society, i.e., those “upstream” macro-social networks suggested by Berkman et al. (2000). Equally and possibly more importantly to this dyad, these effects may have a corrosive impact on micro-social network strength, interrupting mechanisms of social engagement and restricting access to peripheral support. Our findings suggest that diminishing external social networks, increased social effort and poor interpersonal communication significantly affect the family carer and consequently, their immediate relationship with their family member with DSI.

Conclusion

The increasing prevalence of DSI in older Australians and related communication and social concerns presents a growing public health concern. This research report presents the experiences of family carers in the context of DSI and contributes to a growing body of research directed at social inclusion of this population. Family carers report social isolation, social effort and a need to negotiate their relationship. The findings presented in this report suggest that the negative social experiences of DSI are pervasive and can potentially adversely affect the dyadic relationship. Findings suggest that supporting carers to maintain their external social networks may benefit both caregiver and care-receiver in facilitating access to external resources, reducing the effort of caring in this context and potentially improving social inclusion for those with DSI. Given the overwhelming reliance of those with DSI on family carers for physical, social and emotional support, these issues are under-explored in the DSI literature and emphasize the value of qualitative research that is inclusive of the family carer perspective.

Limitations

The aim of the broader doctoral study from which these findings are taken, is to develop a grounded theory of the social experiences of those with DSI, their family carer and their dyadic relationship. This paper reports on the findings from the family carers’ narratives and explores three key themes. Family carers comprised of both daughter and spousal relatives and the differences in dyadic dynamics are acknowledged as an important consideration in understanding the family carers’ experience. One of the limitations of this manuscript is the capacity to fully explore relationship variables and how this impacts the social and caregiving experiences. In future publications, this aspect of caregiving will be fully explored.

Submission Statement

Dual Sensory Impairment (DSI) describes the concurrent loss of both vision and hearing and is an under-diagnosed chronic condition prevalent in aging populations. Untreated or, without appropriate support, it undermines the ability of older people to function independently. DSI presents the older adult with complex functional and social challenges, often requiring additional care. Caregiving is a dyadic process, which involves complex interactions, stressful for both caregiver and those with DSI. To date, considering the increased awareness of DSI in older age, there is limited understanding of caregiving in this context, despite family carers’ critical role in facilitating social participation and realizing popular preferences for aging at home.

This report discusses select findings from a qualitative research study using Grounded Theory methodology (GTM). This research explores the social experiences of older Australians and their family carers in a DSI context, and how these experiences shape their social networks. We found that social isolation and social effort significantly impacted the family carer, their dyadic relationship and their external social networks, limiting the potential benefits derived from these networks.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Human Research Ethics Committee, University of Sydney, Sydney, 2006, NSW (HREC 2014/897). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

This original research report was part of the doctoral thesis of MD. MD was responsible for the development of this manuscript and coordination of the study with ongoing support from doctoral supervisors JG, JS, and HM. All authors collaborated on data analysis and development of findings and all read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank all participants who willingly shared their experiences with us for this study. We are grateful to Vision Australia and local Vision Impaired support groups in NSW, Australia who provide ongoing support to this older population and their families, and who willingly shared their expertise and experience with us for this study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.572201/full#supplementary-material

References

Antonucci, T. C., Ajrouch, K. J., and Birditt, K. S. (2013). The convoy model: explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. Gerontologist 54, 82–92. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt11

Arndt, K., and Parker, A. (2016). Perceptions of social networks by adults who are deafblind. Am. Ann. Deaf. 161, 369–383. doi: 10.1353/aad.2016.0027

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015). Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, (Catalogue 4430.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018). Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, (Catalogue 4430.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Government Department of Health (2019). Dementia, Ageing and Aged Care Mission. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/dementia-ageing-and-aged-care-mission (accessed May 12, 2020).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] (2018). Older Australia at a Glance. Canberra: AIHW.

Barken, R. (2017). Reconciling tensions: needing formal and family/friend care but feeling like a burden. Can. J. Aging 36, 81–96. doi: 10.1017/s0714980816000672

Berkman, L., Glass, T., Brissette, I., and Seeman, T. (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 51, 843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4

Bodsworth, S., Clare, I., and Simblett, S. (2011). Deafblindness and mental health: psychological distress and unmet need among adults with dual sensory impairment. Br. J. Vis. Impair. 29, 6–26. doi: 10.1177/0264619610387495

Braun, M., Scholz, U., Bailey, B., Perren, S., Hornung, H., and Martin, M. (2009). Dementia Caregiving in spousal relationships: a dyadic perspective. Age. Ment. Health 13, 426–436. doi: 10.1080/13607860902879441

Breheny, M., and Stephens, C. (2012). Negotiating a moral identity in the context of later life care. J. Aging Stud. 26, 438–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.06.003

Brennan, M., Horowitz, A., and Su, Y.-P. (2005). Dual sensory loss and its impact on everyday competence. Gerontologist 45, 335–346.

Brennan, M., Su, Y.-P., and Horowitz, A. (2006). Longitudinal associations between dual sensory impairment and everyday competence among older adults. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 4, 777–792. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2005.06.0109

Capella-McDonnall, M. E. (2005). The effects of developing a dual sensory loss on depression in older adults: a longitudinal study. J. Age. Health 21, 1179–1199. doi: 10.1177/0898264309350077

Carter, S., and Little, M. (2007). Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Q. Health Res. 17, 1316–1328. doi: 10.1177/1049732307306927

Chia, E. M., Mitchell, P., Rochtchina, E., Foran, S., Golding, M., and Wang, J. J. (2006). Association between vision and hearing impairments and their combined effects on quality of life. Archiv. Ophthalmol. 124, 1465–1470. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.10.1465

Cimarolli, V., and Jopp, D. (2014). Sensory impairments and their associations with functional disability in a sample of the oldest-old. Q. Life Res. 23, 1977–1984. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0657-0

Cloutier-Fisher, D., Kobayashi, K., and Smith, A. (2011). The subjective dimension of social isolation: a qualitative investigation of older adults’ experiences in small social support networks. J. Aging Stud. 25, 407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.012

Commonwealth of Australia (2019). Carers of Older Australians, Royal Commission into Aged Care, Quality and Safety Background Paper. Available at: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Publications_Archive/archive/agedcare (accessed May 12, 2020).

Dey, I. (2007). “Grounding categories,” in The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory, eds A. Bryant and K. Charmaz, (New York, NY: SAGE Publications Ltd), 166–190. doi: 10.4135/9781848607941.n8

Dullard, B., and Saunders, G. (2016). Documentation of dual sensory impairment in electronic medical records. Gerontologist 56, 313–317. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu032

Dyke, P. (2013). A Clear View: Identifying Australians Who Live With Deafblindness and Dual Sensory Loss. Available at: www.senses.org.au (accessed April 4, 2020).

Fletcher, P., and Guthrie, D. (2013). The lived experience of individuals with acquired deafblindness: challenges and the future. Intern. J. Disabil. Commun. Rehabil. 12:1.

Heine, C., and Browning, C. (2002). Communication and psychosocial consequences of sensory loss in in older adults: Overview and rehabilitation directions. Disabil. Rehabil. 24, 763–773. doi: 10.1080/09638280210129162

Heine, C., and Browning, C. (2014). Mental health and dual sensory loss in older adults: a systematic review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14:83. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00083

Heine, C., and Browning, C. (2015). Dual sensory loss in older adults: a systematic review. Gerontologist 55, 913–928. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv074

Heine, C., Erber, N. P., Osborn, R., and Browning, C. J. (2002). Communication perceptions of older adults with sensory loss and their communication partners: Implications for intervention. Disabil. Rehabil. 24, 356–363. doi: 10.1080/09638280110096250

Hofsoe, S. M., Lehane, C., Wittich, W., Hilpert, P., and Dammeyer, J. (2018). Interpersonal communication and psychological well-being among couples coping with sensory loss: the mediating role of perceived spouse support. J. Soc. Pers. Relationsh. 36, 2323–2344. doi: 10.1177/0265407518787933

Hovaldt, H. B., Lund, R., Lehane, C., and Dammeyer, J. (2019). Relational Strain in close social relations among older adults with dual sensory loss. Br. J. Vis. Impair. 37, 81–93. doi: 10.1177/0264619619833421

Huddle, M., Deal, J., Swenor, B., Genther, D., and Lin, F. (2016). The association of dual sensory impairment with hospitalization and burden of Disease. J. Ame. Geriatr. Soc. 64, 1735–1737. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14210

Hwang, P., Longstreth, W., Francis, C., Thielke, S., and Fitzpatrick, L. (2019). Dual sensory impairment in older adults and risk of dementia and Alzheimers Disease. Alzheim. Dement. 15, 196.

Jaiswal, A., Aldersley, H., Wittich, W., Mansha, M., and Finlayson, M. (2018). Participation experiences of people with Deafblindness or dual sensory loss: a scoping review of the global deafblind literature. PLoS One 13:e0203772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203772

Kemperman, A., van den Berg, P., Weijs-Perree, M., and Uijtdewillegen, K. (2019). Loneliness of older adults: social network and the living environment. Intern. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 2–16.

Kwon, H. J., Kim, J. S., Kwon, S. J., and Yu, J. N. (2015). Sensory Impairment and Health-Related Quality of Life. Iran J. Public Health 46, 772–782.

Lehane, C., Dammeyer, J., and Elsass, P. (2017a). Sensory loss and its consequences for couples’ psychosocial and relational well-being. Aging Men. Health 21, 337–347. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1132675

Lehane, C., Hofsoe, S. M., Wittich, W., and Dammeyer, J. (2017b). Mental health and spouse support among older couples living with dual sensory loss. J. Aging Health 30, 1205–1223. doi: 10.1177/0898264317713135

Lehane, C., Dammeyer, J., and Wittich, W. (2019). Intra and interpersonal effects of coping on the psychological well-being of adults with sensory loss and their spouses. Disabil. Rehabil. 41, 796–807. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1410583

Lehane, C., Elsass, P., Hovaldt, H., and Dammeyer, J. (2018a). A relationship-focused investigation of spousal psychological adjustment to dual-sensory loss. Aging Ment. Health 22, 397–404. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1268091

Lehane, C., Nielsen, T., Wittich, W., Langer, S., and Dammeyer, J. (2018b). Couples coping with sensory loss: a dyadic study of the roles of self- and perceived partner acceptance. Br. J. Health Psychol. 23, 646–664. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12309

Luo, Y., He, P., Guo, C., Li, N., and Zheng, X. (2018). Association between sensory impairment and dementia in older adults: evidence from china. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66, 480–486. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15202

Lyons, K., and Lee, C. (2018). The theory of dyadic illness management. J. Fam. Nurs. 24, 8–28. doi: 10.1177/1074840717745669

Maharani, A., Dawes, P., Nazroo, J., Tampubolon, G., and Pendleton, N. (2018). Longitudinal relationship between hearing aid use and cognitive function in older americans. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66, 1130–1136. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15363

McPake, B., and Mahal, A. (2017). Addressing the needs of an aging population in the health system: the Australian case. Health Syst. Reform 3, 236–247. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2017.1358796

Moon, H., Townsend, A., Whitlach, C., and Dilworth-Anderson, P. (2017). Quality of life for dementia caregiving dyads: effects of incongruent perceptions of everyday care and values. Gerontologist 57, 657–666. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw055

Saunders, G. H., and Echt, K. V. (2007). An overview of dual sensory impairment in older adults: perspectives for rehabilitation. Trends Amplif. 11, 243–258. doi: 10.1177/1084713807308365

Schneider, J. M., Gopinath, B., McMahon, C. M., Leeder, S., and Wang, J. J. (2011). Dual sensory impairment in older age. J. Age. Health 23, 1309–1324. doi: 10.1177/0898264311408418

Schneider, J. M., Gopinath, B., McMahon, C. M., Teber, E., Leeder, S., Wang, J. J., et al. (2012). Prevalence and 5-year incidence of dual sensory impairment in an older Australian population. Ann. Epidemiol. 22, 295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.02.004

Schneider, J. M., McMahon, C. M., Gopinath, B., Kifley, A., Barton, R., Mitchell, P., et al. (2014). Dual sensory impairment and hearing aid use among clients attending low-vision services in Australia: the vision-hearing project. J. Aging Health 26, 231–249. doi: 10.1177/0898264313513610

Sebern, M., and Whitlatch, C. (2007). Dyadic relationship scale: a measure of the impact of the provision and receipt of family care. Gerontologist 47, 741–751. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.741

Siegler, V. (2014). Office for National Statistics, UK, (2014a), ‘Measuring Social Capital, 2014’. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105213847/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/wellbeing/measuring-national-well-being/measuring-social-capital–july-2014/art-measuring-social-capital.html (accessed April 4, 2020).

Simcock, P. (2017). One of society’s most vulnerable groups? A systematically conducted literature review exploring the vulnerability of deafblind people. Health Soc. Care Commun. 25, 813–839. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12317

Simcock, P., and Wittich, W. (2019). Are older deafblind people being left behind? A narrative review of literature on Deafblindness through the lens of the United Nations Principles for Older People. J. Soc. Welf. Fam. Law 41, 339–357. doi: 10.1080/09649069.2019.1627088

Solomon, D., Hansen, L., Baggs, J., and Lyons, K. (2015). Relationship quality in non-cognitively impaired mother-daughter care dyads: a systematic review. J. Fam. Nurs. 21, 551–578. doi: 10.1177/1074840715601252

Stephens, C., Alpass, F., and Stevenson, B. (2011). The effects of types of social networks, perceived social support and loneliness on the health of older people: accounting for the social context. J. Age. Health 23, 887–911. doi: 10.1177/0898264311400189

Suanet, B., Huxhold, O., and Schafer, M. (2020). Cohort difference in age-related trajectories in network size in old age: are networks expanding? J. Gerontol. Ser. B. 75, 137–147. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx166

Tie, Y. C., Birks, M., and Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: a design framework for novice researchers. Sage Open Med. 7, 1–8. doi: 10.1177/2050312118822927

Tiwana, R., Benbow, S. M., and Kingston, P. (2016). Late life acquired dual sensory impairment [DSI]: a systematic review of its impact on everyday competence. Br. J. Vis. Impair. 34, 203–213. doi: 10.1177/0264619616648727

Tolkacheva, N., van Groenou, M. B., de Boer, A., and van Tilburg, T. (2011). The impact of informal care-giving networks on adult children’s care-giver burden. Age. Soc. 31, 34–51. doi: 10.1017/s0144686x10000711

United Nations (1991). Principles for Older Persons, Resolution 46/91. New York, NY: United Nations. doi: 10.1017/s0144686x10000711

Upenieks, L., Settels, J., and Schafer, M. (2018). For everything a season? A month-by-month analysis of social network resources in later life. Soc. Sci. Res. 69, 111–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.09.004

van Tilburg, T. (1998). Losing and gaining in old age: changes in personal network size and social support in a four-year longitudinal study. J. Gerontol. 53B, S313–S323.

van Tilburg, T., and Thomese, F. (2010). “Societal dynamics in personal networks,” in The Sage Handbook of Social Gerontology, eds D. Dannefer and P. Phillipson, (New York, NY: Sage), 215–225. doi: 10.4135/9781446200933.n16

Westaway, L., Wittich, W., and Overbury, O. (2011). Depression and burden in spouses of individuals with sensory impairment. Insight Res. Pract. Vis. Impair. Blind. 4, 29–36.

Wittich, W., Jarry, J., Groule, G., Southall, K., and Gagne, J.-P. (2016). Rehabilitation and research priorities in Deafblindness for the next decade. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 110, 219–231. doi: 10.1177/0145482x1611000402

World Health Organisation [WHO] (2011). Global Health and Ageing, NIH Publication no. 11-7737 1-32. Geneva: WHO.

Keywords: dual sensory impairment, deafblind, aging, social exclusion, social support, family carers, caregiving, dyad

Citation: Dunsmore ME, Schneider J, McKenzie H and Gillespie JA (2020) The Effort of Caring: The Caregivers’ Perspective of Dual Sensory Impairment. Front. Educ. 5:572201. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.572201

Received: 13 June 2020; Accepted: 02 September 2020;

Published: 29 September 2020.

Edited by:

Walter Wittich, Université de Montréal, CanadaReviewed by:

Camilla S. Øverup, University of Copenhagen, DenmarkMoa Maria Wahlqvist, Örebro University, Sweden

Copyright © 2020 Dunsmore, Schneider, McKenzie and Gillespie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Moira E. Dunsmore, moira.dunsmore@sydney.edu.au

Moira E. Dunsmore

Moira E. Dunsmore Julie Schneider

Julie Schneider Heather McKenzie3

Heather McKenzie3 James A. Gillespie

James A. Gillespie