- 1Food and Environmental Engineering Department, Yangjiang Polytechnic, Yangjiang, China

- 2Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Marine Biotechnology, Shantou University, Shantou, China

- 3State Key Laboratory of Biocontrol, Institute of Aquatic Economic Animals, and the Guangdong Province Key Laboratory for Aquatic Economic Animals, Life Science School, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China

The Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus, a polychaete benthic invertebrate belonging to the Nereididae family, has emerged as a promising aquaculture species. It is highly regarded for its nutritional profile, with protein accounting for up to 60% of its dry weight, as well as its balanced amino acid composition. This has earned it the nickname “aquatic cordyceps”. However, wild populations of this species have declined significantly due to environmental shifts and human activities, with local extinctions reported in certain regions. A critical barrier to advancing its population genetics and conservation biology has been the absence of a chromosomal-level reference genome for T. heterochaetus. To address this gap, we present the first chromosome-level genome assembly of T. heterochaetus, generated using PacBio HiFi sequencing data and Hi-C technology. The final assembly spans 782.25 Mb with a scaffold N50 of 75.39 Mb, successfully anchored to 11 pseudo-chromosomes. Repetitive sequences account for 428.09 Mb (54.73%) of the genome, and 20,145 protein-coding genes were annotated. This study provides foundational insights into the genetics, genomics, and evolutionary history of T. heterochaetus, laying a critical groundwork for future research and enabling the development of targeted genetic conservation strategies.

1 Introduction

Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus, commonly known as “Hechong” in Chinese, is a polychaete, benthic invertebrate belonging to the Nereididae family (order: Polychaeta; phylum: Annelida). It is widely distributed across the brackish coastal waters of China, Japan and Southeast Asia (Tuan, 2018; Yang et al., 2020). In the estuarine regions of south-eastern China, this species primarily colonises paddy ecosystems, where it feeds on crop roots, forming a natural symbiotic association with rice (Su et al., 2016). The “rice + T. heterochaetus” integrated ecological farming model not only significantly increases the economic returns of rice cultivation, but also promotes the reuse of abandoned farmland and helps to ensure food security. Collectively, these attributes make it a promising candidate for emerging aquaculture development.

In addition, T. heterochaetus has remarkable nutritional value. Protein accounts for up to 60% of its dry weight and it has a well-balanced amino acid profile (Zhang et al., 2022). This has earned it the reputation of being the “aquatic cordyceps” (Glasby and Timm, 2008). Studies have shown that it contains 10–20 species of fatty acids, B vitamins and trace elements (including calcium, iron and selenium), which together regulate dyslipidaemia and prevent atherosclerosis (Suzuki and Gotoh, 1986; Osanai, 1978). Furthermore, it contains high levels of fibrinolytic enzymes, fibrinogen activators and collagenase, which support the prevention and treatment of cerebral thrombosis and myocardial infarction (Wu et al., 2006). However, T. heterochaetus occupies a narrow ecological niche and is acutely sensitive to abrupt environmental shifts. In recent years, rising commercial demand coupled with increasing pressures from water pollution and habitat fragmentation has led to a continuous decline in wild populations and even local extinctions in some regions (Tuan, 2018; Chen et al., 2020).

Currently, research on T. heterochaetus has primarily focused on its morphological characteristics, life history, reproductive biology, culture techniques, and nutritional composition (Wu et al., 2006; Sato and Osanai, 1990; Ma et al., 2014). However, systematic genetic investigations remain scarce. To date, only Chen et al. (Chen et al., 2020) have sequenced its complete mitochondrial genome and analyzed the genetic structure of seven geographic populations using mitochondrial COI sequences. Meanwhile, Yang et al. (Yang et al., 2023a; Yang et al., 2023b) leveraged genome survey data and transcriptome information to preliminarily characterize microsatellite features and develop polymorphic molecular markers. Despite these contributions, a complete and well-assembled nuclear genome is still unavailable. This paucity of genomic data significantly impedes in-depth studies of its genetic regulatory networks, adaptive evolution mechanisms, and population genetic diversity.

In recent years, the rapid advancement of high-throughput sequencing technologies, particularly third-generation sequencing (TGS), has provided a key technical foundation for molecular biology research in areas such as evolutionary analysis, functional gene mining and genomic breeding (Huang et al., 2025). A prime example is Pacific Biosciences’ single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing, which leverages its circular consensus sequencing (CCS) mode to generate long reads and high-fidelity (HiFi) reads (Wenger et al., 2019). These capabilities have substantially enhanced the continuity and completeness of genome assemblies. Meanwhile, high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technology enables genome-wide DNA interactions to be deciphered, facilitating the construction of high-resolution, three-dimensional chromatin architecture (Dekker et al., 2002). Integrating third-generation long-read sequences with chromatin interaction data enabled us to overcome key challenges associated with repetitive sequences and structural variations in genome assembly (Wenger et al., 2019). Therefore, this study employed a combined strategy of PacBio HiFi sequencing and Hi-C technology. The result was the decoding of a high-quality, chromosome-level genome for T. heterochaetus. This genome assembly provides the first systematic insights into the gene structure and distribution of functional elements in T. heterochaetus, as well as the chromosome arrangement. It also provides foundational data to support subsequent genetic breeding target screening, analysis of adaptive evolution mechanisms, and germplasm resource conservation. Furthermore, this work establishes critical genomic resources for population genetics studies and provides a fundamental molecular basis for evolutionary biology research on Nereididae polychaetes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection and DNA extraction

One adult male individual of the species Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus (body length: 7.5 cm) was obtained from Guangdong Yanghai Agricultural Technology Co., Ltd. (Yangjiang, Guangdong, China; 111°55′23″E, 21°49′16″N; Figure 1A). Following three washes with sterile water, the body wall muscle tissue was dissected from the individual and transferred to a 2 mL cryotube. The tissue was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until required. For Illumina DNA library, fresh muscle tissue was used for DNA extraction using the phenol–chloroform method (Sambrook and Russell, 2006). For PacBio HiFi long-read sequencing, the high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA was extracted using the Genomic-tip kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA concentration and purity were assessed using a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), respectively; the integrity was evaluated using 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with approval from the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Yangjiang Polytechnic (licence no. 2019DW003).

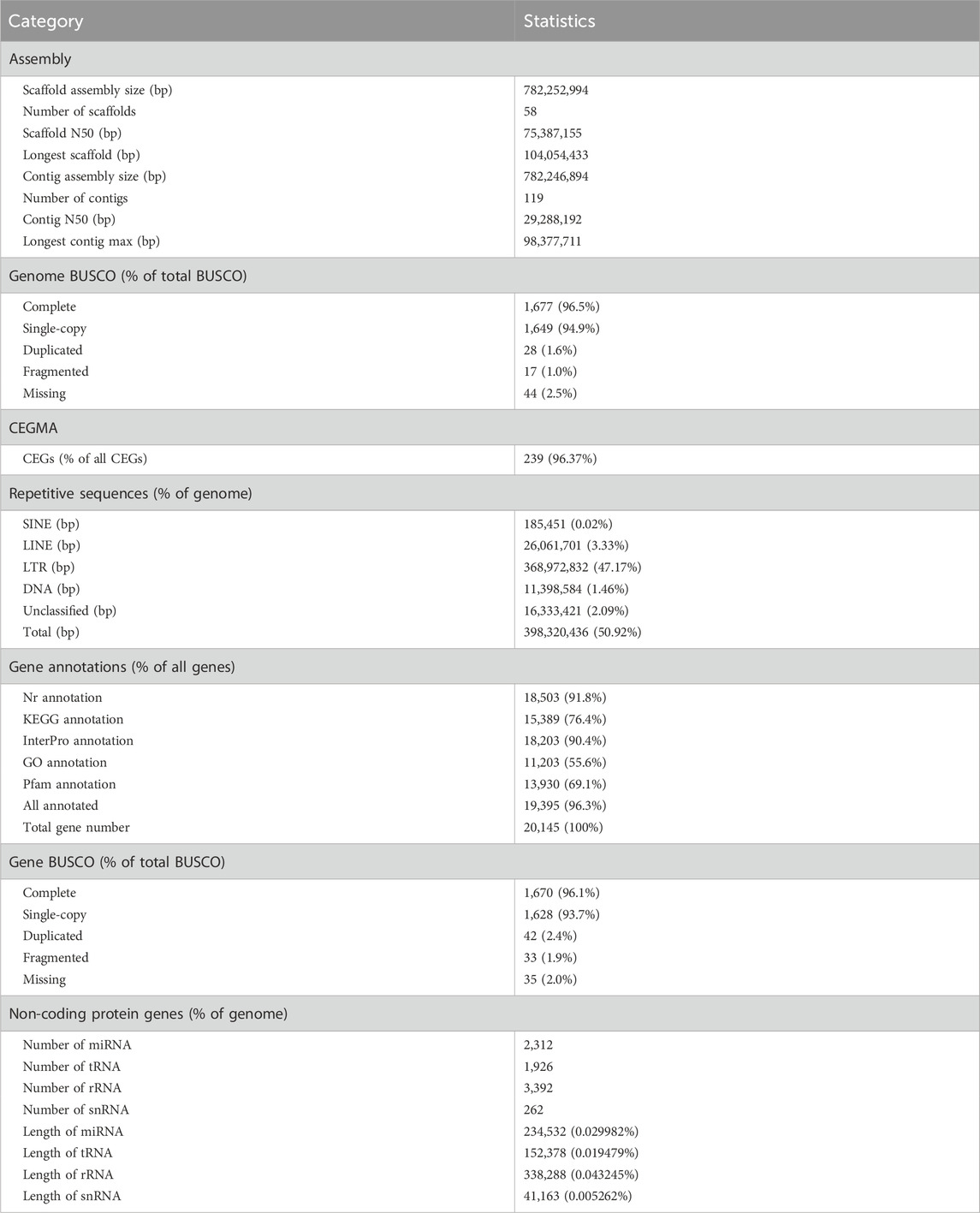

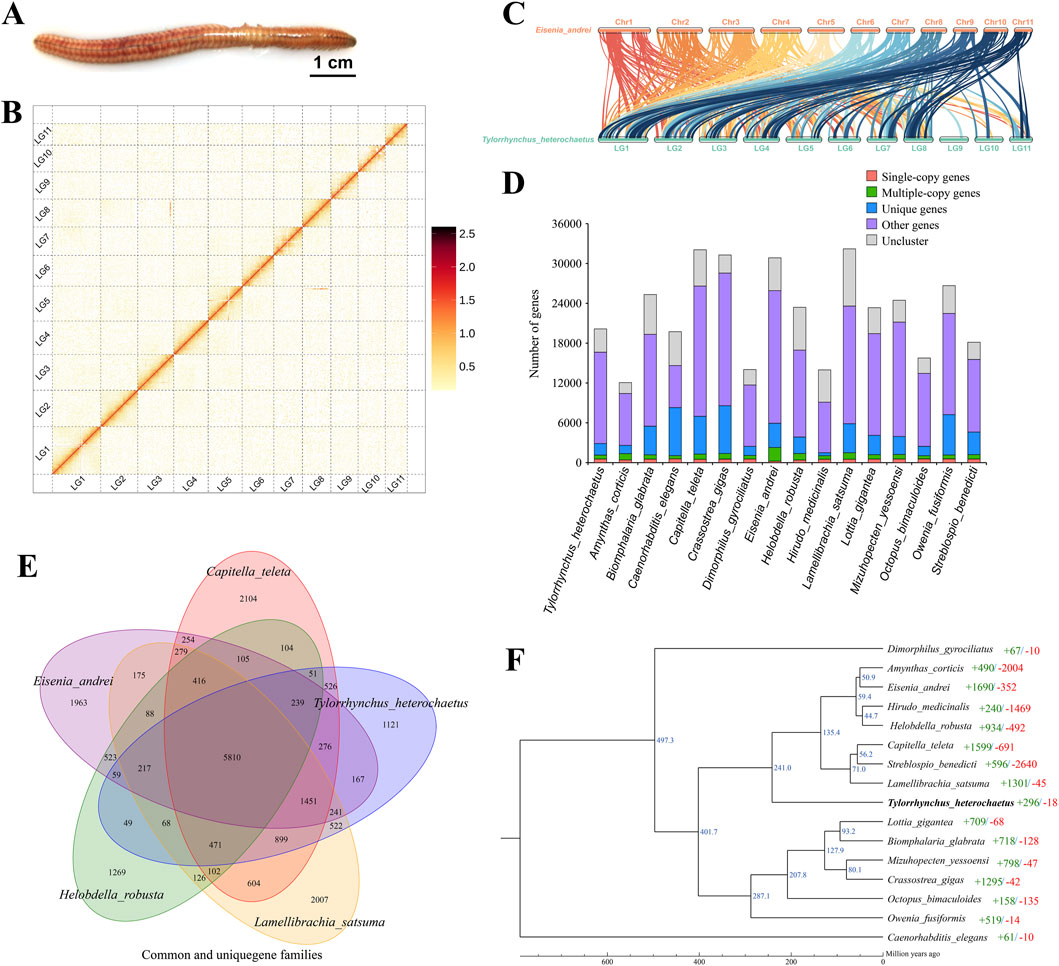

Figure 1. Characteristics of the Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus genome. (A) The Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus. (B) Genome-wide Hi-C interaction heatmap of Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus. The heatmap illustrates interaction frequencies across the genome, with darker red intensities indicating higher interaction frequencies. The 11 distinct square blocks along the diagonal represent the 11 reconstructed pseudo-chromosomes (linkage groups). The schematic on the right serves as the color scale key for interaction frequency. LG1-11 are the abbreviations of Lachesis Group 1–11, representing the 11 pseudo-chromosomes. (C) Genome comparison between Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus and Eisenia andrei. The lines between the horizontal lines link the alignment blocks. (D) Gene family clustering in Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus and fifteen other species. (E) Venn Diagram representation of gene family overlaps and specificities among Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus, Capitella teleta, Eisenia andrei, Helobdella robusta and Lamellibrachia satsuma. (F) Phylogenetic analysis and a divergence time tree for Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus relative to other species were inferred, using Caenorhabditis elegans as the outgroup. The number of significantly expanded (+, green) and contracted (−, red) gene families is assigned to each branch following the species names. Estimated species divergence times (in million years ago, Ma) are indicated on each branch; these times were retrieved from the TimeTree database.

2.2 Library construction and genome sequencing

To characterise the genomic features of Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus, an Illumina DNA library with a 350 bp insert size was constructed using the Illumina Genomic DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was then performed on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform by Novogene (Beijing, China) using a 150 bp paired-end protocol.

A DNA library was constructed using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, United States) to perform PacBio HiFi long-read sequencing, according to the standard PacBio protocol. The library was then sequenced on a PacBio Sequel II platform. High-accuracy consensus reads were generated using the Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) module in SMRT Link v11.0 (Chin et al., 2013).

Approximately 1 g of muscle tissue was harvested for Hi-C sequencing. A Hi-C library was constructed using the GrandOmics Hi-C Kit (GrandOmics, Wuhan, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, chromatin was crosslinked in situ with formaldehyde to preserve 3D chromatin structures, and the reaction was quenched with glycine. Nuclei were subsequently extracted via tissue lysis, and the fixed chromatin was digested with the restriction enzyme MboI. Following digestion, DNA ends were filled with biotinylated nucleotides and ligated to generate chimeric molecules. After reversing crosslinks, the DNA was purified and sheared to prepare the sequencing library. Library concentration and insert size were assessed using a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and an Agilent 2,100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States), respectively. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6,000 platform in paired-end mode. Raw reads were preprocessed using Fastp v0.20.0 (Chen et al., 2018) to remove adapters and filter out low-quality sequences.

2.3 Transcriptome sequencing

As muscle tissue constitutes the majority of the body mass of Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus, it was selected for transcriptome sequencing. Total RNA was extracted from the tissue using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States), following the manufacturer’s protocol. mRNA was then purified from the total RNA extract using an Oligotex mRNA Midi Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The integrity of the RNA was evaluated using an Agilent 2,100 Bioanalyzer, and only samples with an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) of at least 8.0 were retained for library construction. The library was constructed in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines and was then sequenced using a 150 bp paired-end protocol on a HiSeq X Ten platform (Illumina, San Diego, California, United States).

2.4 Genome size assessment and preliminary assembly

To estimate the genome size, heterozygosity, and repeat content of Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus, we performed K-mer analysis using Jellyfish v2.3.0 (Marçais and Kingsford, 2011). The frequency distribution was computed based on 17-mers from clean Illumina sequencing reads. A k-mer size of 17 was selected as this yielded the most consistent and biologically plausible estimates compared to k = 21 or 31. It also offered the clearest distinction between heterozygous and homozygous peaks. The k-mer distribution can be used to estimate genome size, and the peak of the k-mer frequency curve can be used as an indicator of overall sequencing depth. The genome size was calculated using the following formula: Genome size = total k-mer number/peak depth (Marçais and Kingsford, 2011).

In a heterozygous genome, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) sites are usually few and far between. Ideally, two heterozygous K-mers are generated around each SNP site. These heterozygous K-mers exhibit half the expected coverage depth of homozygous K-mers. The heterozygosity rate is estimated using the following equation:

where nKspecies denotes the total number of K-mer species, and a1/2 represents the proportion of heterozygous K-mer species (Li and Waterman, 2003; Liu et al., 2013). Deviations between the observed K-mer distribution and a theoretical Poisson distribution can arise from sequencing errors or copy number variations, both of which can affect subsequent estimates. Therefore, the repeat rate was calculated based on the percentage of total K-mers with depths exceeding 1.8 times the main peak depth (Liu et al., 2013). Following characterisation, the preliminary genome was assembled using PacBio HiFi long-read with hifiasm v0.11 (Cheng et al., 2021) and the default parameters. The resulting contig-level assembly was subsequently polished with Pilon v1.23 (Walker et al., 2014) and clean Illumina short reads to correct potential base-calling errors.

2.5 Chromosome-level genome assembly and assessment

To construct a chromosome-level genome assembly, raw Hi-C data were processed using Hicup v0.8.1 (Wingett et al., 2015), which identified valid interaction pairs. These valid pairs were then utilized by the 3D-DNA v180419 pipeline (Dudchenko et al., 2017) to anchor, order, and orient the contigs into pseudo-chromosomes. Visual inspection and manual curation were subsequently performed using Juicebox v1.9.8 (Durand et al., 2016) to correct assembly errors. Following this refinement, the final chromosome-level assembly was generated. To validate scaffold ordering into pseudo-chromosomes, we performed synteny analysis between the genome of Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus and the chromosome-level assembly of Eisenia andrei using MCScanX (Wang et al., 2012).

To assess the completeness of the assembly, we employed both BUSCO v5.2.2 (Simão et al., 2015) and CEGMA v2.5 (Parra et al., 2007). BUSCO analysis was conducted against the annelida_odb10 lineage dataset, while CEGMA evaluated the coverage of core conserved eukaryotic genes.

2.6 Repetitive sequence and noncoding RNA annotation

We employed a hybrid approach combining de novo and homology-based methods to identify repeat sequences in the Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus genome. For the latter, RepeatMasker v4.1.0 (Bao et al., 2015) was used to identify known repetitive elements. De novo repetitive element databases were constructed using LTRharvest v1.0.6 (Zhao and Wang, 2007), RepeatScout v1.0.5 (Abrusán et al., 2009) and RepeatModeler v2.0.1 (Price et al., 2005). Tandem repeats were also predicted using TRF v4.09 (Benson, 1999). Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) were annotated using tRNAscan-SE v2.0 (Chan et al., 2021) and Infernal v1.1.3 (Nawrocki and Eddy, 2013), which identified tRNAs, rRNAs, snRNAs and miRNAs.

2.7 Gene prediction and functional annotation

We employed a comprehensive strategy integrating homology-based, transcript-based and de novo prediction methods to predict protein-coding genes. For de novo prediction, we utilised five tools: AUGUSTUS v3.2.3 (Stanke and Waack, 2003); GlimmerHMM v3.04 (Majoros et al., 2004); SNAP v2013-11-29 (Korf, 2004); GeneID v1.4 (Blanco et al., 2007); and Genscan v3.1 (Burge and Karlin, 1997). These were used to identify candidate genes. Homology-based predictions were conducted using protein sequences retrieved from the publicly available databases for the following six species: Helobdella robusta (GCF_000326865.1), Lamellibrachia satsuma (GCA_022478865.1), Dimorphilus gyrociliatus (GCA_904063045.1), Eisenia andrei (GWHACBE00000000), Capitella teleta (GCA_000328365.1) and Owenia fusiformis (GCA_903813345.2). Homology searches and gene annotation were then performed using GeMoMa v1.6.4 (Keilwagen et al., 2016) with the default parameters. For transcript-based prediction, short-read Illumina RNA-seq data were assembled into transcripts using Trinity v2.5.2 (Haas et al., 2013) and the resulting gene structures were validated using PASA v2.3.3 (Haas et al., 2003). Finally, all gene predictions were integrated via the Evidence Modeler (EVM) pipeline v1.0 (Haas et al., 2008) to produce a consensus gene set.

Gene functional annotation involved aligning protein sequences to the Swiss-Prot database (Bairoch and Apweiler, 2000) using BLASTp (Altschul et al., 1990), and functional assignments were derived from the best hit (e-value ≤1 × 10−5). Motif and domain annotations were performed using InterProScan v5.31 (Quevillon et al., 2005), which queries public databases including ProDom, PRINTS, Pfam, SMART, PANTHER and PROSITE. Gene Ontology (GO) terms (Ashburner et al., 2000) were then assigned to each gene by mapping them to the relevant InterPro entries (Finn et al., 2017). Protein-coding genes were further annotated by transferring functional labels from two sources: (1) the top BLASTp hits (e-value <1 × 10−5) in the Swiss-Prot database, and (2) the DIAMOND hits (e-value <1 × 10−5) in the non-redundant protein database (Kanz et al., 2005; Buchfink et al., 2015). Additionally, the gene set was mapped to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000) to assign each gene to the most appropriate metabolic or signalling pathway.

2.8 Gene family identification and phylogenetic analysis

We used OrthoMCL v2.0.9 (Li et al., 2003) to identify orthologous groups based on protein sequences from sixteen species: Dimorphilus gyrociliatus (Annelida, Dinophilidae, GCA_904063045.1), Amynthas corticis (Annelida, Megascolecidae, GWHAOSM00000000.1), Eisenia andrei (Annelida, Lumbricidae, GWHACBE00000000), Hirudo medicinalis (Annelida, Hirudinidae, GCA_011800805.1), Helobdella robusta (Annelida, Glossiphoniidae, GCF_000326865.1), Capitella teleta (Annelida, Capitellidae, GCA_000328365.1), Streblospio benedicti (Annelida, Spionidae, GCA_019095985.1), Lamellibrachia satsuma (Annelida, Siboglinidae, GCA_022478865.1), Owenia fusiformis (Annelida, Oweniidae, GCA_903813345.2), Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus (Annelida, Nereididae, GWHHJEW00000000.1), Lottia gigantea (Mollusca, Lottiidae, GCF_000327385.1), Biomphalaria glabrata (Mollusca, Planorbidae, GCF_947242115.1), Mizuhopecten yessoensis (Mollusca, Pectinidae, GCF_002113885.1), Crassostrea gigas (Mollusca, Ostreidae, GCF_000297895.1), Octopus bimaculoides (Mollusca, Octopodidae, GCA_001194135.2) and Caenorhabditis elegans (Nematoda, Rhabditidae, GCF_000002985.6). These species were selected based on their phylogenetic representation within Annelida and Lophotrochozoa, as well as the availability of high-quality reference genomes. Selected species included key annelid references, such as Eisenia andrei, which serve as critical benchmarks for understanding annelid evolution. The genes were then grouped into orthologous (orthologs) and paralogous (paralogs) clusters. Single-copy orthologues shared by all 16 species were aligned using MUSCLE v3.8.31 (Edgar, 2004) and a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using PHYML v3.0 (Guindon et al., 2010). Divergence times among species were estimated using the MCMCTree program (PAML package v4.7a; Yang, 2007), with calibration based on divergence time estimates from the TimeTree database (http://timetree.org/).

2.9 Gene family comparison

Gene family expansion and contraction are key drivers of phenotypic diversity and environmental adaptation (Rayna and Hans, 2015). In this study, we used CAFE v4.2 (De Bie et al., 2006) to identify gene families that had expanded or contracted significantly (adjusted p < 0.05). We estimated ancestral gene family numbers using a birth-death model to infer evolutionary expansions and contractions. To elucidate the biological functions associated with these changes, we performed KEGG pathway enrichment analysis using Fisher’s exact test, applying a False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction (<0.05) to control for multiple testing.

To identify putative positively selected genes (PSGs) and genes undergoing accelerated evolution, we constructed a set of single-copy orthologues common to five species: Capitella teleta, Eisenia andrei, Helobdella robusta, Owenia fusiformis and Lamellibrachia satsuma. First, we conducted multiple sequence alignments of protein sequences within each gene family via Muscle v3.6 (Edgar, 2004). Synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitution rates were then calculated using PAML v4.4c (Yang, 1997), with codon-based substitution models implemented via the codeml program and the likelihood ratio test (LRT). To further pinpoint PSGs, we applied the branch-site model, computing LRT p-values under the null hypothesis of a 50:50 mixture between an ω2-distribution (df = 1) and a point mass at zero. Stringent filtering was subsequently applied, retaining only genes that satisfied all of the following criteria: (a) gene length ≥300 bp, (b) ≥2 positively selected sites, and (c) no gaps in any stretch of three consecutive amino acids.

3 Data

3.1 Genome sequencing and assembly

K-mer analysis (K = 17) based on Illumina reads indicated a sequencing depth of ∼57×, estimating the Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus genome size at 759.53 Mb, with a heterozygosity rate of 1.41% and a repeat content of 45.92% (Supplementary Figure S1). PacBio HiFi sequencing generated 20 Gb of HiFi reads (Supplementary Table S1). As an annelid, T. heterochaetus possesses tissues rich in polysaccharides and mucus, which are prone to co-precipitation during HMW DNA extraction. Consequently, although the yield of ultra-HMW DNA was limited, the quantity obtained met the requirements for library construction and assembly. Subsequently, we generated a primary contig assembly of 782.25 Mb with a contig N50 of 29.29 Mb using hifiasm (Table 1). Finally, by integrating Hi-C data, a total of 777.18 Mb scaffolds (representing 99.35% of the total sequence) was anchored onto 11 linkage groups (Supplementary Table S2; Figure 1B), yielding a highly continuous final assembly with a scaffold N50 of 75.39 Mb. Furthermore, synteny analysis revealed a clear correspondence between the 11 linkage groups of T. heterochaetus and the chromosomes of Eisenia andrei, thereby validating the ordering of scaffolds into pseudo-chromosomes (Figure 1C).

BUSCO assessment revealed 1,677 (96.5%) complete BUSCOs, comprising 1,649 single-copy and 28 duplicated entries (Table 1). The CEGMA analysis identified 239 conserved eukaryotic core genes, constituting 96.37% of the 248 genes in the database (Table 1). These results demonstrate that the genome assembly achieves high coverage and completeness.

3.2 Genome annotation

De novo prediction and Repbase database analyses revealed that repetitive sequences constitute 54.73% of the Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus genome. Among these transposable elements, long terminal repeats (LTRs, 47.17%) were the most abundant, followed by long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs, 3.33%), DNA transposons (1.46%), and short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs, 0.02%) (Table 1; Supplementary Table S3).

A combined approach using de novo, homology-based, and RNA-seq predictions identified 20,145 protein-coding genes in the T. heterochaetus genome, with an average gene length of 10,909.40 bp (Supplementary Table S4). The length distributions of genes, coding sequences (CDS), exons, and introns in T. heterochaetus were comparable to those of other annelids (Supplementary Figure S2). The functions of the protein-coding genes were annotated in NR, KEGG, InterPro, GO and Pfam databases. A total of 19,395 genes were annotated, accounting for 96.30% of all protein-coding genes (Table 1).

Noncoding RNAs were predicted using Rfam, cmsearch, and tRNAscan-SE, yielding 2,312 miRNAs, 1,926 tRNAs, 3,392 rRNAs, and 262 snRNAs (Table 1; Supplementary Table S5).

3.3 Comparative genome analysis

A comparison of 15 species genomes was conducted to investigate the phylogenetic relationships of Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus. These species were selected based on their phylogenetic representation within Annelida and Lophotrochozoa, as well as the availability of high-quality reference genomes. They include close relatives such as Eisenia andrei, which serve as key references for understanding annelid evolution. In total, 33,522 gene families were clustered across the 16 species, with T. heterochaetus possessing 12,170 of these gene families (Figure 1D; Supplementary Table S6). A venn diagram was constructed for the gene families of Capitella teleta, Eisenia andrei, Helobdella robusta, Lamellibrachia satsuma and T. heterochaetus. Among these, 1,121 gene families were unique to T. heterochaetus, while 5,810 gene families were conserved across all five species (Figure 1E).

The ML phylogenetic tree was constructed from single-copy orthologs. The Caenorhabditis elegans as an outgroup in a separate clade, while the remaining 15 Lophotrochozoa species form a single clade (Figure 1F). This Lophotrochozoa clade further resolves into three distinct branches. The Dimorphilus gyrociliatus diverged from the common ancestor of the other 14 species at approximately 497.3 Ma. Subsequently, around 401.7 Ma, the common ancestor of eight Annelida species (Amynthas corticis, E. andrei, Hirudo medicinalis, H. robusta, C. teleta, Streblospio benedicti, L. satsuma, and T. heterochaetus) separated from the ancestor of the remaining six species (Lottia gigantea, Biomphalaria glabrata, Mizuhopecten yessoensis, Crassostrea gigas, Octopus bimaculoides, Owenia fusiformis). Notably, the annelid O. fusiformis clusters with the five Mollusca species. Recent studies indicate that Oweniidae and Magelonidae form a monophyletic group, termed Palaeoannelida, which constitutes the sister taxon to all other annelids (Weigert and Bleidorn, 2016), potentially explaining this unusual placement. In our analysis, T. heterochaetus, an annelida from Polychaeta, Errantia, clusters with Oligochaeta (A. corticis and E. andrei), Hirudinea (H. medicinalis and H. robusta), and Sedentaria (C. teleta, S. benedicti, and L. satsuma) species, all of which belong to Annelida. This consistent taxonomic grouping underscores the high accuracy of the genome assembly presented here.

Gene family expansion and contraction represent key drivers of phenotypic diversity evolution. We compared gene families across sixteen species: C. elegans, D. gyrociliatus, A. corticis, E. andrei, H. medicinalis, H. robusta, C. teleta, S. benedicti, L. satsuma, T. heterochaetus, L. gigantea, B. glabrata, M. yessoensis, C. gigas, O. bimaculoides, and O. fusiformis. In T. heterochaetus, 296 gene families were significantly expanded (p < 0.05) and 18 were significantly contracted (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S7). KEGG enrichment analysis demonstrated that expanded gene families were preferentially associated with signal transduction, immune response, and digestive processes. Key enriched pathways included cAMP and TNF signaling, cytosolic DNA-sensing, ABC transporters, and vitamin digestion. Notably, the expansion of the GPCR, TLR, and Cytochrome P450 superfamilies likely facilitates adaptation to the challenges of the benthic environment (Supplementary Table S8). In contrast, contracted lineages were largely restricted to functional categories involving cellular community (e.g., gap/tight junctions) and developmental processes (e.g., dorso-ventral axis formation and axon regeneration) (Supplementary Table S9). Additionally, positive selection occurs when non-synonymous amino acid mutations arise in single-copy gene families as organisms adapt to external influences. Using C. teleta, E. andrei, H. robusta, O. fusiformis, and L. satsuma as controls, we identified genes under positive selection in T. heterochaetus. The analysis revealed 305 genes under positive selection (Supplementary Table S10).

4 Conclusion

This study presents a chromosomal-level genome assembly for Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus. The resulting genome exhibits continuity and completeness comparable to other high-quality Annelida genomes, thereby offering a valuable reference for systems biology and comparative evolutionary analysis. This reference genome holds importance for the aquaculture and artificial breeding of T. heterochaetus, establishing a foundation for further investigation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. The final genome assembly and annotation files (predicted CDS and protein sequences) generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.31015993). Raw sequencing data, including Illumina, PacBio, Hi-C, and RNA-seq reads, have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject PRJNA1346694 (Accession numbers: SRR35822427, SRR35819296, SRR35859756, and SRR35859347). Additionally, the final genome assembly is available in the Genome Warehouse (GWH) of the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) under accession number GWHHJEW00000000.1 (BioProject PRJCA049339).

Ethics statement

The animal studies were approved by Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Yangjiang Polytechnic. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study.

Author contributions

WY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. XZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing. BF: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review and editing. YS: Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing. RX: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review and editing. SL: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review and editing. ZM: Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing. XC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by grants from the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022A1515011231); Guangdong Province Scientific and Technological Support Project for the “Hundreds, Thousands, and Ten Thousands Project” (BQW2024006); Yangjiang City 2023 Provincial Science and Technology Special Funds (“Major Projects + Task List”) (SDZX2023034); Yangchun City’s Construction Project for the County-Level Innovation Base under the “Hundreds, Thousands, and Ten Thousands Project” (SBQW2024041); Innovative Team of Guangdong Province Universities and College (2024KCXTD059); Yangjiang Vocational and Technical College’s Key Projects in Natural Science (2022kjzd01 and 2023kjzd03).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2026.1753621/full#supplementary-material

References

Abrusán, G., Grundmann, N., DeMester, L., and Makalowski, W. (2009). TEclass—a tool for automated classification of unknown eukaryotic transposable elements. Bioinformatics 25, 1329–1330. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp084

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., and Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Ashburner, M., Ball, C. A., Blake, J. A., Botstein, D., Butler, H., Cherry, J. M., et al. (2000). Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29. doi:10.1038/75556

Bairoch, A., and Apweiler, R. (2000). The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 45–48. doi:10.1093/nar/21.13.3093

Bao, W., Kojima, K. K., and Kohany, O. (2015). Repbase update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob. DNA 6, 11. doi:10.1186/s13100-015-0041-9

Benson, G. (1999). Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580. doi:10.1093/nar/27.2.573

Blanco, E., Parra, G., and Guigó, R. (2007). Using geneid to identify genes. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 18, 4. doi:10.1002/0471250953.bi0403s18

Buchfink, B., Xie, C., and Huson, D. H. (2015). Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 12, 59–60. doi:10.15496/publikation-1176

Burge, C., and Karlin, S. (1997). Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 268, 78–94. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02509.x

Chan, P.-P., Lin, B.-Y., Mak, A. J., and Lowe, T. M. (2021). tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 9077–9096. doi:10.1101/614032

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y., and Gu, J. (2018). Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

Chen, X.-H., Yang, S., Yang, W., Si, Y.-Y., Xu, R.-W., Fan, B., et al. (2020). First genetic assessment of brackish water polychaete Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus: mitochondrial COI sequences reveal strong genetic differentiation and population expansion in samples collected from southeast China and north Vietnam. Zool. Res. 41, 61–69. doi:10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.006

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H., and Li, H. (2021). Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175. doi:10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5

Chin, C. S., Alexander, D. H., Marks, P., Klammer, A. A., Drake, J., Heiner, C., et al. (2013). Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods 10, 563–569. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2474

De Bie, T., Cristianini, N., Demuth, J. P., and Hahn, M. W. (2006). CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics 22, 1269–1271. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097

Dekker, J., Rippe, K., Dekker, M., and Kleckner, N. (2002). Capturing chromosome conformation. Science 295, 1306–1311. doi:10.1126/science.1067799

Dudchenko, O., Batra, S. S., Omer, A. D., Nyquist, S. K., Hoeger, M., Durand, N. C., et al. (2017). De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95. doi:10.1126/science.aal3327

Durand, N. C., Robinson, J. T., Shamim, M. S., Machol, I., Mesirov, J. P., Lander, E. S., et al. (2016). Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101. doi:10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012

Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh340

Finn, R. D., Attwood, T. K., Babbitt, P. C., Bateman, A., Bork, P., Bridge, A. J., et al. (2017). InterPro in 2017-beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D190–D199. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw1107

Glasby, C. J., and Timm, T. (2008). Global diversity of polychaetes (polychaeta; annelida) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 595, 107–115. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9008-2

Guindon, S., Dufayard, J. F., Lefort, V., Anisimova, M., Hordijk, W., and Gascuel, O. (2010). New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syq010

Haas, B. J., Delcher, A. L., Mount, S. M., Wortman, J. R., Smith Jr, R. K., Hannick, L. I., et al. (2003). Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg770

Haas, B. J., Salzberg, S. L., Zhu, W., Pertea, M., Allen, J. E., Orvis, J., et al. (2008). Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 9, R7. doi:10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7

Haas, B. J., Papanicolaou, A., Yassour, M., Grabherr, M., Blood, P. D., Bowden, J., et al. (2013). De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494–1512. doi:10.1038/nprot.2013.084

Huang, Y., Li, Z., Li, M., Zhang, X., Shi, Q., and Xu, Z. (2025). Fish genomics and its application in disease-resistance breeding. Rev. Aquat. 17, e12973. doi:10.1111/raq.12973

Kanehisa, M., and Goto, S. (2000). KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. doi:10.1093/nar/27.1.29

Kanz, C., Aldebert, P., Althorpe, N., Baker, W., Baldwin, A., Bates, K., et al. (2005). The EMBL nucleotide sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D29–D33. doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.19

Keilwagen, J., Wenk, M., Erickson, J. L., Schattat, M. H., Grau, J., and Hartung, F. (2016). Using intron position conservation for homology-based gene prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e89. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw092

Li, X., and Waterman, M. S. (2003). Estimating the repeat structure and length of DNA sequences using L-tuples. Genome Res. 13, 1916–1922. doi:10.1101/gr.1251803

Li, L., Stoeckert, C. J., and Roos, D. S. (2003). OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189. doi:10.1101/gr.1224503

Liu, B. H., Shi, Y. J., Yuan, J. Y., Hu, X. S., Zhang, H., Li, N., et al. (2013). Estimation of genomic characteristics by analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects. arXiv.1308.2012v1. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1308.2012v1 (Accessed August 20, 2025).

Ma, D.-C., Ye, L.-H., Xu, A.-Y., Pan, G., and Long, C. (2014). A histological study of Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus. South China Fish. Sci. 10, 58–63. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-0780.2014.04.010

Majoros, W. H., Pertea, M., and Salzberg, S. L. (2004). TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics 20, 2878–2879. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bth315

Marçais, G., and Kingsford, C. (2011). A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011

Nawrocki, E. P., and Eddy, S. R. (2013). Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509

Osanai, K. (1978). Early development of the Japanese palolo, Tylorrhyuchus heterochaetus. Bull. Mar. Biol. Stn. Asamushi 16, 59–69.

Parra, G., Bradnam, K., and Korf, I. (2007). CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics 23, 1061–1067. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C., and Pevzner, P. A. (2005). De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, i351–i358. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018

Quevillon, E., Silventoinen, V., Pillai, S., Harte, N., Mulder, N., Apweiler, R., et al. (2005). InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W116–W120. doi:10.1093/nar/gki442

Rayna, M. H., and Hans, A. H. (2015). Seeing is believing: dynamic evolution of gene families. PNAS 112, 1252–1253. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423685112

Sambrook, J., and Russell, D. W. (2006). Purification of nucleic acids by extraction with phenol: chloroform. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2006. doi:10.1101/pdb.prot4455

Sato, M., and Osanai, K. (1990). Sperm attachment and acrosome reaction on the egg surface of the polychaete, Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus. Biol. Bull. 178, 101–110. doi:10.2307/1541968

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V., and Zdobnov, E. M. (2015). BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351

Stanke, M., and Waack, S. (2003). Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics 19, 215–225. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1080

Su, Y.-P., Huang, Q., and Cui, K.-P. (2016). Present situation of Hechong industry and analysis of increased breeding benefits in pearl river Estuary area. Ocean. Fish. 10, 64–67.

Suzuki, T., and Gotoh, T. (1986). The complete amino acid sequence of giant multisubunit hemoglobin from the polychaete Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 9257–9267. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09771.x

Tuan, N. N. (2018). Biological characteristics and effects of salinity on reproductive activities of marine worm (Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus, quatefages, 1865) in summer season in Hai Phong-Viet Nam. Creat. Sci. 10, 25–31.

Walker, B. J., Abeel, T., Shea, T., Priest, M., Abouelliel, A., Sakthikumar, S., et al. (2014). Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PloS One 9, e112963. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112963

Wang, Y., Tang, H., DeBarry, J. D., Tan, X., Li, J., Wang, X., et al. (2012). MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e49. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1293

Weigert, A., and Bleidorn, C. (2016). Current status of annelid phylogeny. Org. Divers. Evol. 16, 345–362. doi:10.1007/s13127-016-0265-7

Wenger, A. M., Peluso, P., Rowell, W. J., Chang, P. C., Hall, R. J., Concepcion, G. T., et al. (2019). Accurate circular consensus long-read sequencing improves variant detection and assembly of a human genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 1155–1162. doi:10.1038/s41587-019-0217-9

Wingett, S., Ewels, P., Furlan-Magaril, M., Nagano, T., Schoenfelder, S., Fraser, P., et al. (2015). HiCUP: pipeline for mapping and processing Hi-C data. F1000Res 4, 1310. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7334.1

Wu, Y. G., Pang, C. F., Wen, S. H., and Li, H. Y. (2006). Analysis and evaluation of nutritional components of Hechong (Tylorrhynchus heterochaeta). J. Hydroecology 26, 86–88.

Yang, Z. (1997). PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Bioinformatics 13, 555–556. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555

Yang, Z. (2007). PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biology Evolution 24, 1586–1591. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm088

Yang, Z., Sunil, C., Jayachandran, M., Zheng, X., Cui, K., Su, Y., et al. (2020). Anti-fatigue effect of aqueous extract of Hechong (Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus) via AMPK linked pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 135, 111043. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2019.111043

Yang, W., Si, Y.-Y., Xu, R.-W., and Chen, X.-H. (2023a). Characterization of microsatellites and polymorphic marker development in ragworm (Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus) based on genome survey data. South China Fish. Sci. 19, 123. doi:10.12131/20230086

Yang, W., Si, Y.-Y., Xu, R.-W., and Chen, X.-H. (2023b). Identification and characteristics analysis of SSR loci in the transcriptome of Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus. J. South. Agric. 54, 2593–2603. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-1191.2023.09.010

Zhang, W., Wang, Z., Ganesan, K., Yuan, Y., and Xu, B. (2022). Antioxidant activities of aqueous extracts and protein hydrolysates from marine worm Hechong (Tylorrhynchus heterochaeta). Foods 11, 1837. doi:10.3390/foods11131837

Keywords: chromosomal assembly, gene family comparison, genome annotation, phylogenetic analysis, Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus

Citation: Yang W, Zhang X, Fan B, Si Y, Xu R, Li S, Meng Z and Chen X (2026) Chromosome-level reference genome of Tylorrhynchus heterochaetus (Annelida, Nereididae). Front. Genet. 17:1753621. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2026.1753621

Received: 25 November 2025; Accepted: 12 January 2026;

Published: 28 January 2026.

Edited by:

Karine Frehner Kavalco, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, BrazilReviewed by:

Marcelo De Bello Cioffi, Federal University of São Carlos, BrazilPeng Luo, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), China

Copyright © 2026 Yang, Zhang, Fan, Si, Xu, Li, Meng and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinghan Chen, Q2hlbnhoMTk3OEAxNjMuY29t

Wei Yang

Wei Yang Xuemin Zhang1

Xuemin Zhang1 Shengkang Li

Shengkang Li Zining Meng

Zining Meng Xinghan Chen

Xinghan Chen