Abstract

Nanoplastics (NPs) are ubiquitous in harvested organisms at various trophic levels, and more concerns on their diverse responses and wide species-dependent sensitivity are continuously increasing. However, systematic study on the toxic effects of NPs with different functional group modifications is still limited. In this review, we gathered and analyzed the toxic effects of NPs with different functional groups on microorganisms, plants, animals, and mammalian/human cells in vitro. The corresponding toxic mechanisms were also described. In general, most up-to-date relevant studies focus on amino (−NH2) or carboxyl (−COOH)-modified polystyrene (PS) NPs, while research on other materials and functional groups is lacking. Positively charged PS-NH2 NPs induced stronger toxicity than negatively charged PS-COOH. Plausible toxicity mechanisms mainly include membrane interaction and disruption, reactive oxygen species generation, and protein corona and eco-corona formations, and they were influenced by surface charges of NPs. The effects of NPs in the long-term exposure and in the real environment world also warrant further study.

Introduction

Plastics discarded into the environment has become a global concerned pollution (Alak et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). Microplastics, especially nanoplastics (NPs, smaller than 1 μm), could more likely to penetrate the cell membranes and impose adverse impacts on living organisms (Shen et al., 2019). However, due to limitations in quantitative detection, the varying effects of their environmental concentrations are still unclear, although Schirinzi et al. (2019) reported traces of nano-sized polystyrene (PS) in estuarine and surface waters of the West Mediterranean Sea. Toxicities of NPs on development, behavioral alterations, and oxidative stress have attached great importance in various organisms (Duan et al., 2020). Ultimately, they may cause hazards to human health (Sun M. et al., 2021).

The aged plastics through photo-degradation, biodegradation, hydrolysis, and mechanical abrasion in the environment, will result in different surface modifications in NPs. Negatively charged NPs, such as the carbonyl groups (−COOH), are expected to be the most common ones due to surface oxidation and acquisition of functionalities during the weathering (Luan et al., 2019). Positively charged NPs, such as amino modification (−NH2), may also consider as an important counterpart due to the hydrolyzation of polyamides (Wang et al., 2019). However, compared with morphology and size (Aznar et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2020), the presence of functional groups on the surface modifications of plastic polymers working on their toxicological effects remains to be systematically studied.

Thus, the toxic effects of NPs, with different functional groups or without modification (bare NPs), were reviewed and compared on microorganisms, plants, animals, and mammalian/human cells in vitro in the present study. We aim to provide some new information concerning on the health risk of NPs in the environment.

Bibliometric Analysis

The keywords used in the bibliographic search were as follows: “nanoplastics, toxic mechanism, toxic effects, surface modification, and functional group” or “nanoplastics, toxic mechanism, toxic effects, and amino-modified” or “nanoplastics, toxic mechanism, toxic effects, and carboxyl-modified” in Science Direct database and Web of Science database from January 2012 to December 2021. A total of 477 references were obtained, including review articles and research articles. Abstracts of the retrieved publications were reviewed separately to screen the relevant literature. Only studies that involved the toxic effects and/or toxic mechanisms of NPs researched on organisms were selected for further analysis. Literature that did not specify whether NPs were modified, or the information of NPs was incomplete, or the toxic mechanisms were not assessed based on organisms, were excluded. In addition, a manual review of the reference lists of the selected publications was conducted to recover articles not included in the bibliographic search. Eventually, 6 review articles and 59 research articles (summarized in Table 1) were screened, accounting for approximately 13.6% of the total. The numbers of manuscripts talked about the functional groups including: −NH2 (48), −COOH (40), −COC (1), −SO3H (3), −CNH2NH2+(1), and bare NPs (19).

TABLE 1

| Species | NPs type | Particle size | Exposure concentration | Toxic effects | References |

| Microorganisms | |||||

| Biofilms | PS-bare | 100 and 500 nm | 5–100 mg/L | Oxidative stress | Miao et al., 2019 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| Activated sludge | PS-bare | 100 nm | 100 mg/L | Cell membrane damage and oxidative stress | Qian et al., 2021 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| Halomonas alkaliphila | PS-bare | 55 nm | 20–320 mg/L | Inhibit growth and oxidative stress | Sun et al., 2018 |

| PS-NH2 | 50 nm | ||||

| Synechococcus | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 2–9 μg/mL | Inhibit growth; damage the membrane integrity; changes in metabolic; and oxidative stress | Feng et al., 2019 |

| PS-SO3H | 52.03 nm | ||||

| Escherichia coli | PS-bare | 30–200 nm | 4–32 mg/L | Inhibit growth; oxidative stress; and DNA damage | Ning et al., 2021 |

| PS-NH2 | 200 nm | ||||

| PS-COC | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| Algae in freshwater | |||||

|

Pseudokirchneriella

subcapitata |

PS-NH2 | 20 nm | 10 mg/L | Inhibition of photosynthesis and/or cell wall disruption | Nolte et al., 2017 |

| PS-COOH | 110 nm | ||||

|

Raphidocelis

subcapitata |

PS-COOH | 88 nm | 0.5–50 mg/L | Interfere with mitosis and cell metabolism | Bellingeri et al., 2019 |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 3.4 and 6.8 μg/mL | Inhibit photosystem II efficiency; reduce organic substance synthesis; induce oxidative stress; and enhance the synthesis of microcystin | Feng et al., 2020 |

| PS-SO3H | – | 100 μg/mL | |||

| Algae in seawater | |||||

| Diatom | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 0.05 and 5 μg/mL | Inhibit photosynthesis and destroy lipid structure | González-Fernández et al., 2020 |

| PS-NH2 | 500 nm | 2.5 μg/mL | Decrease in esterase activity and diminished neutral lipid content | Seoane et al., 2019 | |

| Dunaliella tertiolecta | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 5–50 μg/mL | Inhibit growth and photosynthesis | Bergami et al., 2017 |

| PS-COOH | 40 nm | ||||

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | PS-COOH | 60 nm | 1–100 mg/L | No toxic effects | Grassi et al., 2020 |

| Chlorella vulgaris | PS-NH2 | 90, 200, and 300 nm | 25–200 mg/L | Inhibit photosynthesis and algal growth | Khoshnamvand et al., 2021 |

| Rhodomonas baltica | PMMA | 50 nm | 0.5–100 μg/mL | Cell cycle injury; loss of membrane integrity; inhibition of photosynthesis; and decrease cell viability | Gomes et al., 2020 |

| PMMA-COOH | 50 nm | ||||

| Chlorella sp. | PS-bare | 217 nm | 1 mg/L | Eco-corona formation and decline the oxidative stress | Natarajan et al., 2020 |

| PS-NH2 | 217 nm | ||||

| PS-COOH | 220 nm | ||||

| PS-NH2 | 200 nm | 5 mg/L | Reduced bioavailability of TiO2 and decrease oxidative stress and enhance photosynthetic yield | Natarajan et al., 2021 | |

| PS-COOH | |||||

| Terrestrial plants | |||||

| Arabidopsis thaliana | PS-NH2 | 200 nm | 10, 50, and 100 μg/mL | Induced a higher accumulation of ROS and inhibit plant growth and seedling development | Sun X. D. et al., 2020 |

| PS-SO3H | |||||

| PS-COOH | 40 nm | 0.029 g/L | Accumulation of plastics at root surface and cap cells | Taylor et al., 2020 | |

| 8.3 × 1011 n/mL | |||||

| Maize | PS-NH2 | 22 nm | 10–500 ng/spot | Inhibit photosynthesis; inhibit growth; oxidative damage; and upset metabolic balance | Sun H. et al., 2021 |

| PS-COOH | 24 nm | ||||

| Wheat | PS-COOH | 40 nm | 0.029 g/L | Accumulation of plastics at root surface and cap cells | Taylor et al., 2020 |

| 8.3 × 1011 n/mL | |||||

| Aquatic animals in freshwater | |||||

| Daphnia magna-Zooplankton | PS-bare | 100 nm | 75 mg/L | Stimulate the antioxidant system | Lin et al., 2019 |

| PS-n-NH2 | 50 and 100 nm | 40 mg/L | |||

| PS-COOH | 300 nm | 70 mg/L | |||

| PS-p-NH2 | 110 nm | 100 mg/L | |||

| PS(-CNH2NH2+) | 200 nm | 50 and 150 mg/L | Acute toxicity | Saavedra et al., 2019 | |

| PS(-COO-) | |||||

| Caenorhabditis elegans-Zooplankton | PS-bare | 35 nm | 1–1000 μg/L | Reproductive and gonadal developmental toxicity and genotoxicity | Qu et al., 2019 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-bare | 35 nm | 1–100 μg/L | Reproductive and gonadal developmental toxicity and genotoxicity | Sun L. et al., 2020 | |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | 200 and 500 nm | 100 nm/L | Reduce survival rate | Yilimulati et al., 2020 | |

| PS-bare | 50 and 60 nm | 1–50 mg/L | Effects on survival, growth, and reproduction | Schultz et al., 2021 | |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| PS-bare | 116.2 nm | 1 and 10 μg/mL | Change cellular behavior | Kim et al., 2020 | |

| PS-COOH | 110.6 nm | ||||

| PS-NH2 | 120.2 nm | ||||

| Brachionus calyciflorus-Zooplankton | PS(-CNH2NH2+) | 200 nm | 50 and 150 mg/L | Acute toxicity | Saavedra et al., 2019 |

| PS(-COO-) | |||||

| Coregonus lavaretus | PS-COOH | 50 nm | 100 and 10000 pcs | Decrease sperm motility and reduce offspring body mass and impair swimming ability | Yaripour et al., 2021 |

| Aquatic animals in seawater | |||||

| Brachionus plicatilis-Zooplankton | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 0.5–50 μg/mL | Increase mortality rate | Manfra et al., 2017 |

| PS-COOH | 40 nm | ||||

| Ciona robusta-Zooplankton | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 2–15 μg/mL | Developmental toxicity and induced oxidative stress | Eliso et al., 2020 |

| PS-COOH | 60 nm | 5–100 μg/mL | |||

| Artemia franciscana-Zooplankton | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 1 and 10 μg/mL | Exfoliation; increase mortality rates; inhibit growth; inhibit activity; and regulate clap and cstb gene expressions | Bergami et al., 2017 |

| PS-COOH | 40 nm | ||||

| PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 0.1–10 μg/mL | Inhibit growth; inhibit gene expression; neurotoxicity; and higher mortality rate | Varó et al., 2019 | |

| PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 5–100 μg/mL | Impair feeding, motility and multiple molting | Bergami et al., 2016 | |

| PS-COOH | 40 nm | ||||

| Mytilus galloprovincialis Lam. | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 1–50 μg/mL | Stimulate increase in extracellular ROS and NO and induce lysosomal damage and a dramatic decrease in phagocytosis | Canesi et al., 2015 |

| 0.001–20 mg/L | Induce malformations and a delay in development dysregulation of transcription of genes and decrease in shell length | Balbi et al., 2017 | |||

| 0.15 mg/L | |||||

| 1–50 μg/mL | Increase cellular damage and ROS production and induce lysosomal damage and a dramatic decrease in phagocytosis | Canesi et al., 2016 | |||

| 10 μg/L | Induce lysosomal release and a dramatic decrease in phagocytosis | Auguste et al., 2020a | |||

| 10 μg/L | Dysregulation of transcription of genes and affect immune function | Auguste et al., 2020b | |||

| Meretrix | PS-NH2 | 100 nm | 0.02–2 mg/L | Inhibit growth; disrupt energy homeostasis; Digestive tubule atrophy and necrosis; induce lysosomal damage; and inhibit phagocytic activity | Liu et al., 2021 |

| Sea urchin | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 1–50 μg/mL | Increase the appearance of malformations and undeveloped embryos and effects on gene expression | Della Torre et al., 2014 |

| PS-COOH | 40 nm | 2.5–50 μg/mL | |||

| PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 1 and 5 μg/mL | Induce lysosomal damage and a dramatic decrease in phagocytosis | Bergami et al., 2019 | |

| PS-COOH | 40 nm | ||||

| PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 5–25 μg/mL | Induce lysosomal damage | Marques-Santos et al., 2018 | |

| Euphausia superba | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 2.5 mg/L | Increase molting and inhibit swimming activity | Bergami et al., 2020 |

| PS-COOH | 60 nm | ||||

| PS-COOH | 40 nm | ||||

| Crassostrea gigas | PS-bare | 50 and 500 nm | 0.1–25 μmg/L | Developmental toxicity and cytotoxicity | Tallec et al., 2018 |

| PS-NH2 | 50 nm | ||||

| PS-COOH | 50 nm | ||||

| PS-NH2 | 100 nm | 0.1–100 mg/L | ROS generation | González-Fernández et al., 2018 | |

| PS-COOH | 100 nm | ||||

| Mammalian animal | |||||

| Mice | PS-bare | 100 nm | 10 mg/mL | Weight loss induce cell apoptosis; inflammation; structural disorder; damage to the blood system; and lipid metabolism disorders | Xu et al., 2021 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| PS@Bap | 192 nm | 0.5 mg/mL | Protein corona and inhibit cell viability | Ji et al., 2020 | |

| PS-bare | 188 nm | ||||

| Mammalian cells in vitro | |||||

| Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 25 μg/mL | Damage contractility, glycolytic homeostasis and the mitochondrial activity of neonatal cardiomyocytes | Roshanzadeh et al., 2021 |

| PS-COOH | |||||

| Human cells in vitro | |||||

| HepG2 | PS-bare | 50 nm | 10, 50, and 100 μg/mL | Inhibit cell viability; destroy cell morphology; and damage the antioxidant structure | He et al., 2020 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| Caco-2/HT29-MTX-E12/THP-1 | PS-bare | 50 nm | 1–50 μg/cm2 | Reduce cell viability; cytotoxicity; and decrease metabolic activity | Busch et al., 2020 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | 50 and 500 nm | 0.01–100 μg/mL | No effect on cell viability | Hesler et al., 2019 | |

| BEAS-2B | PS-bare | 60 nm | 1–40 μg/mL | Inhibit cell viability; increase ROS production; lead endoplasmic reticulum stress; and induce Lysosomal, autophagic cell death, and protein misfolding | Chiu et al., 2015 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| Calu-3 | PS-bare | 50 nm | 0.3–32.3 μg cm–2 | Decrease cell viability; induce genotoxicity; and increase ROS production | Paget et al., 2015 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| Caco-2, HT29-MTX-E1, RajiB co-culture | PS-bare | 50 and 100 nm | 250 μg/mL | Shift the translocation rates; protein corona; and membrane integrity | Walczak et al., 2015 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| Caco-2, HT29 and LS174T monocultures | PS-bare | 60 nm | 20–100 μg/mL | Inhibit cell viability; induce apoptosis; and induce mucin interaction and cell apoptosis | Inkielewicz-Stepniak et al., 2018 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| THP-1 | PS-NH2 | 120 nm | 1–100 μg/mL | Inhibit cell viability and polarization and induce inflammation | Fuchs et al., 2016 |

| PS-COOH | |||||

| THP-1 | PS-bare | 50 nm | 0.3–32.3 μg cm–2 | Decrease cell viability; induce genotoxicity; and increase ROS production | Paget et al., 2015 |

| PS-NH2 | |||||

| PS-COOH | |||||

| Human erythrocytes | PS-COOH | 200 nm | 50–2000 particles cell–1 | Sensitivity to osmotic, mechanical, oxidative and complement lysis | Pan et al., 2016 |

| Astrocyte 131N | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 100 μg/mL | Induce apoptosis and lysosomal cell death; cell membrane damage | Wang et al., 2013 |

| PS-COOH | 40 nm | ||||

| Brain capillary endothelial cells | PS-COOH | 40, 100, and 200 nm | 25–100 μg/mL | Affect cell viability; particle uptake; induce inflammation; and no cell death | Raghnaill et al., 2014 |

| Human endothelial | PS-COOH | 20, 40, 100, 200, and 500 nm | 10–100 μg/mL | Cell viability, particle localization, lysosome function and integrity | Fröhlich et al., 2012 |

| Alveolar cells | PS-NH2 | 50 nm | 100 μg/mL | Interfere the mechanoadaptive capacity of alveolar cells; cyclic stretch induces higher ROS levels in alveolar cells treated with PS-NPs; and upregulate pro-apoptotic gene expressions | Roshanzadeh et al., 2020 |

| PS-COOH | |||||

Summary of toxicity assessment of NPs with different functional groups.

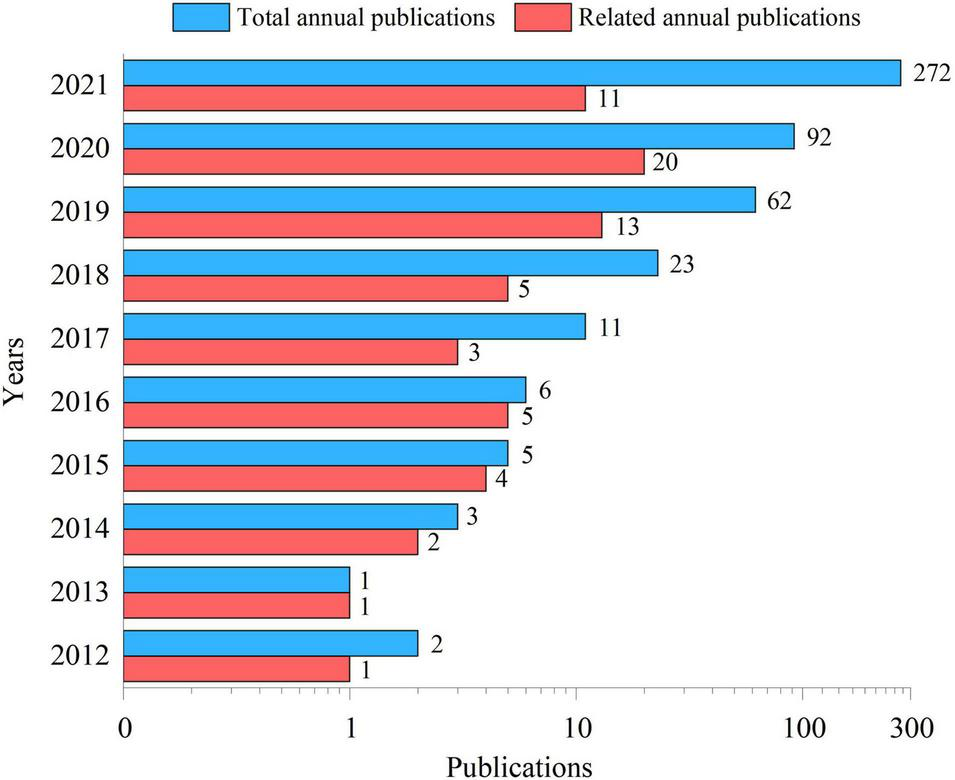

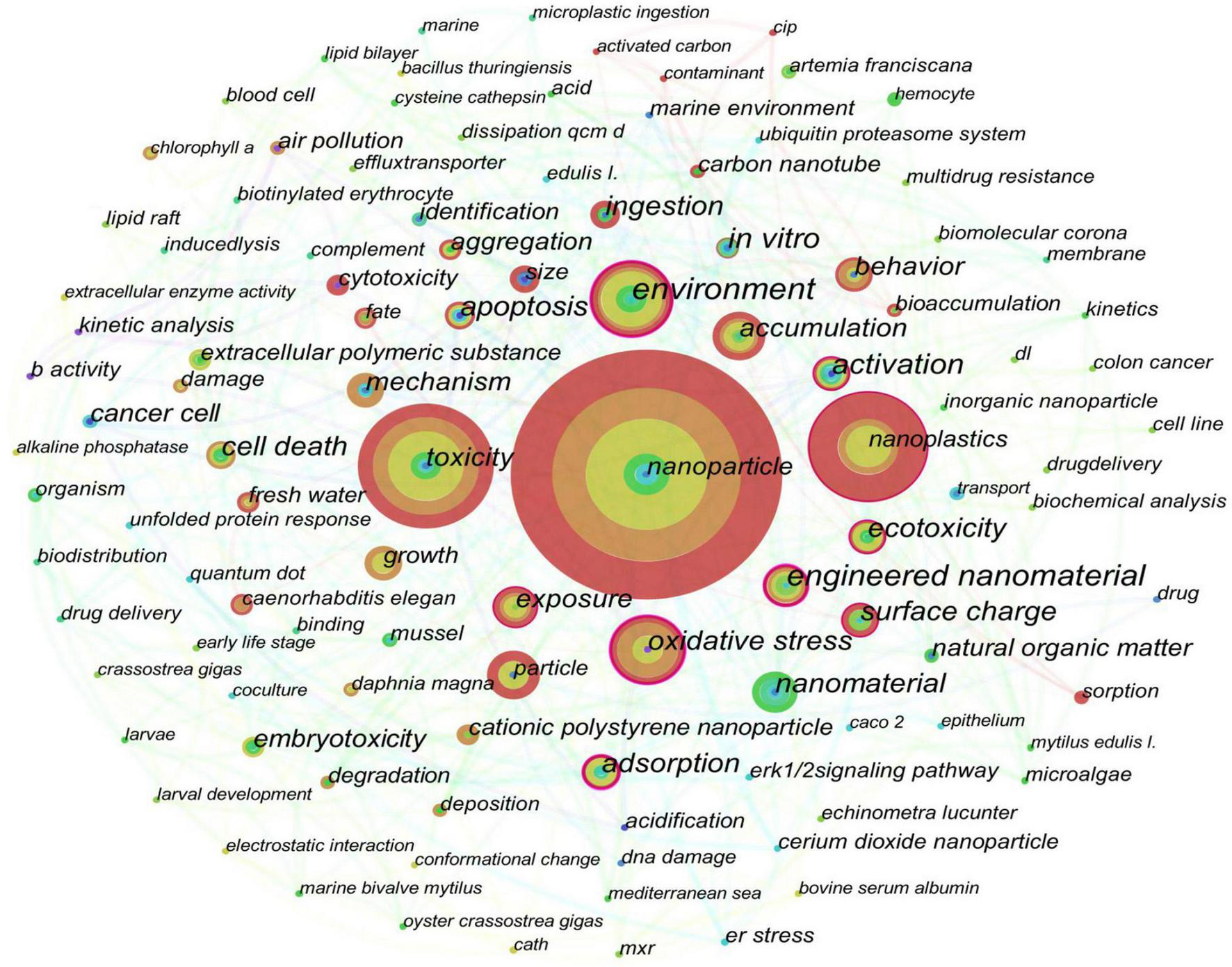

Cite Space software (5.8.R2, 64 bit) and Origin Pro 9.0 (Origin Lab Corp., Northampton, MA, United States) were used to perform visualization and bibliometric analysis, mainly for the number of annual publications and keyword co-occurrence analysis. As shown in Figure 1, the number of published articles on NPs increased from 2 in 2012 to 272 in 2021, which indicated that the toxicity of NPs played important roles in relevant studies. However, only 11 studies compared the toxicities of NPs with different functional groups in 2021. The co-occurrence network (Figure 2) showed that Caenorhabditis elegan, Artemia franciscana, Daphnia magna, mussel, oyster, and algae were the main species used in the previous studies. The main toxic effects included growth, behavior, apoptosis, and cytotoxicity. The main toxic mechanisms discussed involved oxidative stress, accumulation, activation, adsorption, ingestion, surface charge, size, aggregation, and extracellular polymeric substance.

FIGURE 1

Total annual publications and publications from 2012 to 2021 related to this manuscript indexed in Science Direct and Web of Science.

FIGURE 2

Co-occurrence network of keywords extracted from the obtained literature. The size of each node represents the occurrence frequency of the corresponding keyword.

Toxic Effects of NPs With Different Functional Group Modifications

Microorganisms

Microorganisms play important roles in the biological chain as decomposers for the ecosystem (Liu et al., 2020). NPs can penetrate into cells through microbial cell membranes and destroy cell functions (Ning et al., 2021). The toxicity is greater when the particle size is smaller (Miao et al., 2019). For example, PS NPs of 100 and 200 nm had no effect on the growth of Escherichia coli, whereas PS NPs of 30 nm had an increased inhibition on bacterial growth (Ning et al., 2021).

Amino-modified NPs are usually positively charged, which make it easier for them to get into the negatively charged bio-membrane due to the electrostatic interaction (González-Fernández et al., 2018; Tallec et al., 2018). Therefore, the toxicity of amino-modified NPs was supposed to be higher than that of carboxyl-modified NPs and bare NPs. However, to our knowledge, only five manuscripts compared the toxicity of NPs with different functional groups in microorganisms to date. PS-NH2 NPs more strongly inhibited the growth of Synechococcus and damaged the membrane integrity of Synechococcus than PS-SO3H NPs (Feng et al., 2019). PS-NH2 NPs of 50 nm produced a higher reactive oxygen species (ROS) level in Halomonas Alkaliphilathan that bare PS NPs of 55 nm, and the generated ROS may cross extracellular polymers (EPS) and cause great damages (Sun et al., 2018). PS-NH2, bare PS, and PS-COOH NPs caused cell membrane damage and induced oxidative stress in activated sludge and biofilms, and PS-NH2 NPs induced the highest effect among them (Miao et al., 2019; Qian et al., 2021). NPs inhibited the bacterial growth of Escherichia coli in the order of PS-NH2 > PS-COC > PS-COOH (Ning et al., 2021).

Algae and Plants

Algae-adsorbed NPs might be ingested by aquatic animals and transmitted through the food chains, and ultimately result in health risk to human beings (Heddagaard and Møller, 2019; Huang et al., 2020; Mateos-Cárdenas et al., 2021). The potential risks of NPs to the algae in freshwater and seawater have been well documented recently. The toxicity of NPs to the algae was affected by exposure doses, particle sizes, and types of functional groups (González-Fernández et al., 2019). Exposure to carboxyl-modified NPs inhibited the growth of Raphidocelis subcapitata, diatom, Chlorella Vulgaris, Phaeodactylum tricornutum, and Rhodomonas baltica, which was manifested in morphological changes, interference with mitotic cycle, reduction in chlorophyll content, and photosynthetic efficiency (Bellingeri et al., 2019). PS-NH2 NPs with diameters of 90 and 200 nm decreased the biomass and the content of chlorophyll a in Chlorella Vulgaris, and mall-sized PS-NH2 NPs were more toxic than large-sized ones (Khoshnamvand et al., 2021).

Positively charged NPs induced higher toxicology on the algae than negatively charged NPs, which was also due to the electrostatic interaction with bio-membrane. For example, PS-NH2 NPs had higher adsorption ratios on the cell surface of the algae than bare PS and PS-COOH NPs, which limited the material transfer, gas exchange, and energy transfer in diatom (Seoane et al., 2019; González-Fernández et al., 2020). PS-NH2 NPs more significantly inhibited the photo-system efficiency than PS-COOH NPs in Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata (Nolte et al., 2017) and PS-SO3H NPs in Microcystis aeruginosa (Feng et al., 2020). Poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA) caused a higher impact on cellular and physiological parameters than PMMA-COOH (Gomes et al., 2020).

Land-based sources have been considered an important long-term sink for NPs (Rochman, 2018). NPs could accumulate and aggregate on the leaves of land-based plants, transfer from leaves to stems, and finally to roots (Yu et al., 2021). However, the toxicity of NPs to land-based plants was poorly understood although three relevant studies were reported recently. PS-COOH NPs mainly accumulated on the root surface and cap cells of Arabidopsis thaliana and wheat, rather than in roots (Taylor et al., 2020). Compared with PS-COOH NPs, PS-NH2 NPs were more present in roots, which resulted in a stronger inhibitory effect on photosynthesis and growth of maize leaves; they also activated a more obvious oxidative defense mechanism (Sun H. et al., 2021). PS-NH2 NPs induced a higher accumulation of ROS in Arabidopsis thaliana, and they inhibited the plant growth and the seedling development more strongly than PS-SO3H NPs (Sun X. D. et al., 2020).

Animals and Mammalian/Human Cells in vitro

The functional groups of NPs influenced their toxicities to zooplankton in fresh water and seawater (Saavedra et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020; Gola et al., 2021). PS-NH2 NPs enhanced the gonad development, the reproductive capacity, and the genotoxicity to nematode (Caenorhabditis elegan) compared with bare PS NPs and PS-COOH NPs (Qu et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020; Sun L. et al., 2020; Yilimulati et al., 2020; Schultz et al., 2021). Compared with PS-COOH NPs, PS-NH2 NPs induced higher mortality in rotifers (Brachionus plicatilis) (Manfra et al., 2017); PS-NH2 NPs caused more effects on the molting amount, the developmental toxicity on larval Artemia franciscana (Bergami et al., 2016, 2017; Varó et al., 2019), larval Ciona robusta (Eliso et al., 2020), and Daphnia magna (Lin et al., 2019); they also more significantly reduced the swimming activity of Euphausia superba (Bergami et al., 2020).

As for other aquatic animals, pre-fertilization exposure of sperm to PS-NH2 NPs decreased offspring size and swimming performance in the European whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus) (Yaripour et al., 2021). PS-NH2 NPs stimulated the increase in extracellular ROS, induced lysosomal damage, and decreased shell length in two kinds of mussels, Mytilus galloprovincialis (Canesi et al., 2015, 2016; Balbi et al., 2017; Auguste et al., 2020a,b) and Meretrix (Liu et al., 2021). Compared with PS-COOH NPs, PS-NH2 NPs induced severe developmental defects and genetic regulations in the development of sea urchin (Paracentrotus Lividus) embryos (Della Torre et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the controversial joint effects were obtained in some cases. PS-COOH NPs had a significant increase in ROS production in sperm cells of Crassostrea gigas, whereas PS-NH2 NPs did not (González-Fernández et al., 2018). In contrast to PS-COOH, positively charged PS-NH2 seemed to affect the antioxidant and immune genetic responses differently and to a lesser extent in coelomocytes of the Antarctic sea urchin (Bergami et al., 2019).

Few studies have been conducted on their toxic effects on mammals except Xu et al. (2021) reported that PS-NH2 NPs significantly affected the body weight of mice compared with PS-COOH NPs. Several in vitro studies on mammalian and human cells have also confirmed the high toxicity of positively charged NPs. PS-NH2 NPs were more highly internalized in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes when compared with PS-COOH NPs, which resulted in decreased myocardial contractility (Roshanzadeh et al., 2021). PS-NH2 NPs accumulated more than bare PS NPs in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells, and caused greater oxidative damage than PS-COOH NPs in HepG2 cells (He et al., 2020). PS-NH2 NPs increased the cytotoxicity and induced cell apoptosis of human BEAS-2B (Chiu et al., 2015), Calu-3 (Paget et al., 2015), Caco-2 (Walczak et al., 2015; Busch et al., 2020), HT29-MTX-E12 (Inkielewicz-Stepniak et al., 2018), THP-1 cell lines (Fuchs et al., 2016; Hesler et al., 2019), and human alveolar cells (Roshanzadeh et al., 2020). On the contrary, bare PS NPs and PS-COOH NPs did not or were in a lesser extent.

Toxic Mechanism of Nanoplastics With Different Functional Group Modifications

This manuscript summarizes the toxic effects of NPs with different functional groups in various organisms. Most studies focus on PS NPs, while research on other materials of NPs is lacking. The above mentioned studies show that NPs with different functional groups greatly impact on the toxicity of NPs, but most groups are concentrated in amino (−NH2) and carboxyl (−COOH) groups. Only a few studies have been performed on the toxic effects of other functional groups. The surface charge of NPs considerably contribute to the toxic mechanisms of NPs (Banerjee and Shelver, 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). Positively charged NPs (PS-NH2) usually induce stronger toxicity than bare NPs and negatively charged NPs (PS-COOH, PS-SO3H NPs, and PS-COC).

In general, the stimulatory effect of exogenous particles causes granulocytosis to generate ROS in organisms (Qin et al., 2021). Significant decreases in the cell viability and the changed membrane integrity due to the generation of ROS and other cellular parameters are common toxic mechanisms in the microorganisms, algae, plants, animals, and mammalian/human cells in vitro we reviewed above. Positively charged NPs are more likely to interact with the cell membranes due to the negative charges of cell surfaces and cell walls; thus, they will generate more ROS (Sun X. D. et al., 2020), which will result in more effects on oxidative stresses, changes in membrane permeability, and destruction of cell function; they even induce cell apoptosis (Pan et al., 2016; Ning et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, the differences of toxicity mechanisms affected by charged groups of NPs still exist among different species. For microorganisms, the toxic mechanism is limited to the membrane disruption via the generated ROS (Sun et al., 2018), because larger particles cannot be internalized. Algae and plant cells are affected mainly by the adsorption of NPs to the surface through disrupted/damaged membrane, aquaporins, and cell pores, and further cause ROS generation and sequentially damage to the photosynthesis system (Sun H. et al., 2021). As for animal/human cells, the cellular processes of NPs internalized into lysosomesis are also related to their different surface charges (Fröhlich et al., 2012; Raghnaill et al., 2014). Negative NPs can escape from lysosomes and interact with cellular components to trigger cellular stress (Wang et al., 2013; Marques-Santos et al., 2018; Matthews et al., 2021), whereas Positive NPs destabilize lysosomes and initiate a cascade of cellular damage via ROS generation due to the proton sponge hypothesis (Nel et al., 2009). Thus, the cellular process of NPs in animals and human beings might be more complicatedly affected by their charged groups.

The eco-corona on the surface of NPs will be stimulated through coating different components of natural organic matters (NOMs; Grassi et al., 2020). The eco-corona formation enhances the aggregation of the NPs and accompanied with the decreased effective surface area, which will reduce the toxic impact of NPs (Bergami et al., 2017). The formation of the eco-corona is also influenced by the surface charge of NPs (Saavedra et al., 2019). Negatively charged NPs are more effective to form the eco-corona in the presence of EPS than positively charged NPs, which helps them in more significantly lessening the oxidative stress and cytotoxic impact on biological cells (Natarajan et al., 2020, 2021). However, the characteristics of the surrounding environment will significantly influence the biological effects of eco-corona on NPs. For example, PS-NH2 NPs are usually better dispersed than PS-COOH NPs in nature seawater (Della Torre et al., 2014; Bergami et al., 2019). Yet the abundance and composition of NOMs vary significantly across different seawater bodies. Humic acids (HA), one of the main compositions of NOMs in seawater, was found to stabilize negatively charged NPs due to electrostatic repulsion between negative charges and steric effect, whereas it induced PS-NH2 NPs to agglomerate (Wu et al., 2019). Thus, the controversial joint effects might be obtained in marine organisms in some cases (González-Fernández et al., 2018; Bergami et al., 2019).

In addition, the types and charges of surface chemical modification will affect the formation of the protein corona on NPs (Ji et al., 2020). The protein corona might be formed on the surface of NPs when they enter the physiological environment (Li et al., 2020). The formation of the protein corona in the serum is considered as a general protective effect from the potential cytotoxicity of NPs (Coglitore et al., 2019), because they reduce NP surface energy by non-specific adsorption, which leads to the lowered membrane adhesion and uptake efficiency (Lesniak et al., 2013). Positively charged NPs usually adsorb more plasma proteins than negatively charged NPs, which cause more opportunities for them to form the protein corona (Liu et al., 2019). Thus, positively charged NPs are hypothesized to weaken their toxicity more than negatively charged NPs. However, the formation of a PS-NH2-protein corona in hemolymph serum (HS) increased the short term cellular damage and ROS production of PS-NH2 toward immunocytes (Canesi et al., 2016), because NP-protein complexes were hypothesized to function as recognizable molecular patterns to be cleared by phagocytic cells (Hayashi et al., 2013). In addition, the enhanced formation of the protein corona on positively charged NPs will promote their “Trojan-horse effect” on other pollutants (Matthews et al., 2021). The studies on the biological effects of NPs with the protein corona are still in the initial stage. Most of recent results obtained were in vitro, which do not entirely reflect a realistic exposure scenario in vivo. More efforts should be contributed on the specific cell biological behavior of various NPs in the real environment, not limited to their effects on cell uptake efficiency and biocompatibility (Qin et al., 2021).

Conclusion and Research Prospects

In sum, amino-modified polystyrene nanoparticles (PS-NH2) usually induce stronger toxicity than modified NPs, due to their positively charge characteristics. Positively charged NPs are more likely to interact with the cell membranes and generate more ROS than negatively charged NPs, which is mainly due to the negative charges of cell surfaces and cell walls. Nevertheless, there are still some differences existed among different species in the toxicity mechanisms of NPs affected by charged groups. The biological effects of NPs with the eco-corona and protein corona also contribute a lot to their differentiate toxic mechanisms. The exact environmental distributions of these functional group-modified NPs are unclear to date due to the limitations of quantitative detection. The mass balance of NPs between intake and excretion in organisms is also far from being established. Thus, the transmission of these modified NPs on organisms needs to be further researched. Reducing the inherent toxicity of NPs will be an urgent topic due to the substantial environmental problems they induced. The effect of NPs in the long-term exposure and in reality should also be explored.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

HZ: data curation and writing—original draft preparation. YW and HC: data curation. YS and WC: data collection. ZD: supervision, writing, reviewing, editing, and resources. LQ: conceptualization, writing, reviewing, and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41807487) and National College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of China (202010060009).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Alak G. Köktürk M. Atamanalp M. (2021). Evaluation of different packaging methods and storage temperature on MPs abundance and fillet quality of rainbow trout.J. Hazard. Mater.420:126573. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126573

2

Auguste M. Lasa A. Balbi T. Pallavicini A. Vezzulli L. et al (2020a). Impact of nanoplastics on hemolymph immune parameters and microbiota composition in Mytilus galloprovincialis.Mar. Environ. Res.159:105017. 10.1016/j.marenvres.2020.105017

3

Auguste M. Balbi T. Ciacci C. Canonico B. Papa S. Borello A. et al (2020b). Shift in immune parameters after repeated exposure to nanoplastics in the marine bivalve Mytilus.Front. Immunol.11:426. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00426

4

Aznar M. Ubeda S. Dreolin N. Nerín C. (2019). Determination of non-volatile components of a biodegradable food packaging material based on polyester and polylactic acid (PLA) and its migration to food simulants.J. Chromatogr. A5831–8. 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.10.055

5

Balbi T. Camisassi G. Montagna M. Fabbri R. Franzellitti S. Carbone C. et al (2017). Impact of cationic polystyrene nanoparticles (PS-NH2) on early embryo development of Mytilus galloprovincialis: effects on shell formation.Chemosphere1861–9. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.07.120

6

Banerjee A. Shelver W. L. (2020). Micro- and nanoplastic induced cellular toxicity in mammals: a review.Sci. Total Environ.755(Pt. 2):142518. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142518

7

Bellingeri A. Bergami E. Grassi G. Faleri C. Redondo-Hasselerharm P. Koelmans A. A. et al (2019). Combined effects of nanoplastics and copper on the freshwater alga Raphidocelis subcapitata.Aquat. Toxicol.210179–187. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2019.02.022

8

Bergami E. Bocci E. Vannuccini M. L. Monopoli M. Salvati A. Dawson K. A. et al (2016). Nano-sized polystyrene affects feeding, behavior and physiology of brine shrimp Artemia franciscana larvae.Ecotoxicol. Environm. Saf.12318–25. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.09.021

9

Bergami E. Krupinski Emerenciano A. González-Aravena M. Cárdenas C. A. Hernández P. Silva J. et al (2019). Polystyrene nanoparticles affect the innate immune system of the Antarctic sea urchin Sterechinus neumayeri.Polar Biol.42743–757. 10.1007/s00300-019-02468-6

10

Bergami E. Manno C. Cappello S. Vannuccini M. L. Corsi I. (2020). Nanoplastics affect moulting and faecal pellet sinking in Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) juveniles.Environ. Int.143:105999. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105999

11

Bergami E. Pugnalini S. Vannuccini M. L. Manfra L. Faleri C. Savorelli F. et al (2017). Long-term toxicity of surface-charged polystyrene nanoplastics to marine planktonic species Dunaliella tertiolecta and Artemia franciscana.Aquat. Toxicol.189159–169. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.06.008

12

Busch M. Bredeck G. Kämpfer A. A. M. Schins R. P. F. (2020). Investigations of acute effects of polystyrene and polyvinyl chloride micro- and nanoplastics in an advanced in vitro triple culture model of the healthy and inflamed intestine.Environ. Res.193:110536. 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110536

13

Canesi L. Ciacci C. Bergami E. Monopoli M. P. Dawson K. A. Papa S. et al (2015). Evidence for immunomodulation and apoptotic processes induced by cationic polystyrene nanoparticles in the hemocytes of the marine bivalve Mytilus.Mar. Environ. Res.11134–40. 10.1016/j.marenvres.2015.06.008

14

Canesi L. Ciacci C. Fabbri R. Balbi T. Salis A. Damonte G. et al (2016). Interactions of cationic polystyrene nanoparticles with marine bivalve hemocytes in a physiological environment: role of soluble hemolymph proteins.Environ. Res.15073–81. 10.1016/j.envres.2016.05.045

15

Cheng H. Feng Y. Duan Z. Duan X. Zhao S. Wang Y. et al (2020). Toxicities of microplastic fibers and granules on the development of zebrafish embryos and their combined effects with cadmium.Chemosphere269:128677. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128677

16

Chiu H. W. Xia T. Lee Y. H. Chen C. W. Tsai J. C. Wang Y. J. (2015). Cationic polystyrene nanospheres induce autophagic cell death through the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress.Nanoscale7736–746. 10.1039/c4nr05509h

17

Coglitore D. Janot J. M. Balme S. (2019). Protein at liquid solid interfaces: toward a new paradigm to change the approach to design hybrid protein/solid-state materials.Adv. Coll. Interface Sci.270278–292. 10.1016/j.cis.2019.07.004

18

Della Torre C. Bergami E. Salvati A. Faleri C. Cirino P. Dawson K. A. et al (2014). Accumulation and embryotoxicity of polystyrene nanoparticles at early stage of development of sea urchin embryos Paracentrotus lividus.Environ. Sci. Technol.4812302–12311. 10.1021/es502569w

19

Duan Z. Duan X. Zhao S. Wang X. Wang J. Liu Y. et al (2020). Barrier function of zebrafish embryonic chorions against microplastics and nanoplastics and its impact on embryo development.J. Hazard. Mater.395:122621. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122621

20

Eliso M. C. Bergami E. Manfra L. Spagnuolo A. Corsi I. (2020). Toxicity of nanoplastics during the embryogenesis of the ascidian Ciona robusta (Phylum Chordata).Nanotoxicology141415–1431. 10.1080/17435390.2020.1838650

21

Feng L. Li J. Xu E. G. Sun X. Zhu F. Ding Z. et al (2019). Short-term exposure of positively charged polystyrene nanoparticles causes oxidative stress and membrane destruction in cyanobacteria.Environ. Sci. Nano63072–3079. 10.1039/c9en00807a

22

Feng L. Sun X. Zhu F. Feng Y. Duan J. Xiao F. et al (2020). Nanoplastics promote microcystin synthesis and release from cyanobacterial Microcystis aeruginosa.Environ. Sci. Technol.543386–3394. 10.1021/acs.est.9b06085

23

Fröhlich E. Meindl C. Roblegg E. Ebner B. Absenger M. Pieber T. R. (2012). Action of polystyrene nanoparticles of different sizes on lysosomal function and integrity.Part. Fibre Toxicol.9:26. 10.1186/1743-8977-9-26

24

Fuchs A. K. Syrovets T. Haas K. A. Loos C. Musyanovych A. Mailänder V. et al (2016). Carboxyl- and amino-functionalized polystyrene nanoparticles differentially affect the polarization profile of M1 and M2 macrophage subsets.Biomaterials8578–87. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.064

25

Gola D. Kumar Tyagi P. Arya A. Chauhan N. Agarwal M. Singh S. K. et al (2021). The impact of microplastics on marine environment: a review.Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag.16:100552. 10.1016/j.enmm.2021.100552

26

Gomes T. Almeida A. C. Georgantzopoulou A. (2020). Characterization of cell responses in Rhodomonas baltica exposed to Pmma nanoplastics.Sci. Total Environ.726:138547. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138547

27

González-Fernández C. Le Grand F. Bideau A. Huvet A. Paul-Pont I. Soudant P. (2020). Nanoplastics exposure modulate lipid and pigment compositions in diatoms.Environ. Pollut.262:114274.

28

González-Fernández C. Tallec K. Le Goïc N. Lambert C. Soudant P. Huvet A. et al (2018). Cellular responses of Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) gametes exposed in vitro to polystyrene nanoparticles.Chemosphere208764–772. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.06.039

29

González-Fernández C. Toullec J. Lambert C. Goic N. L. Seoane M. Moriceau B. et al (2019). Do transparent exopolymeric particles (tep) affect the toxicity of nanoplastics on chaetoceros neogracile?Environ. Pollut.250873–882. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.093

30

Grassi G. Gabellieri E. Cioni P. Paccagnini E. Faleri C. Lupetti P. et al (2020). Interplay between extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) from a marine diatom and model nanoplastic through eco-corona formation.Sci. Total Environ.725:138457. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138457

31

Hayashi Y. Miclaus T. Scavenius C. Kwiatkowska K. Sobota A. Engelmann P. et al (2013). Species differences take shape at nanoparticles: protein corona made of the native repertoireassists cellular interaction.Environ. Sci. Technol.4714367–14375.

32

He Y. Li J. Chen J. Miao X. Li G. He Q. et al (2020). Cytotoxic effects of polystyrene nanoplastics with different surface functionalization on human HepG2 cells.Sci. Total Environ.723:138180. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138180

33

Heddagaard F. E. Møller P. (2019). Hazard assessment of small-size plastic particles: is the conceptual framework of particle toxicology useful?Food Chem. Toxicol.136:111106. 10.1016/j.fct.2019.111106

34

Hesler M. Aengenheister L. Ellinger B. Drexel R. Straskraba S. Jost C. et al (2019). Multi-endpoint toxicological assessment of polystyrene nano- and microparticles in different biological models in vitro.Toxicol. In Vitro61:104610. 10.1016/j.tiv.2019.104610

35

Huang D. Tao J. Cheng M. Deng R. Chen S. Yin L. et al (2020). Microplastics and nanoplastics in the environment: macroscopic transport and effects on creatures.J. Hazard. Mater.407:124399. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124399

36

Inkielewicz-Stepniak I. Tajber L. Behan G. Zhang H. Radomski M. Medina C. et al (2018). The role of mucin in the toxicological impact of polystyrene nanoparticles.Materials11:724. 10.3390/ma11050724

37

Ji Y. Wang Y. Shen D. Kang Q. Chen L. (2020). Mucin corona delays intracellular trafficking and alleviates cytotoxicity of nanoplastic-benzopyrene combined contaminant.J. Hazard. Mater.406:124306. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124306

38

Khoshnamvand M. Hanachi P. Ashtiani S. Walker T. R. (2021). Toxic effects of polystyrene nanoplastics on microalgae Chlorella vulgaris: changes in biomass, photosynthetic pigments and morphology.Chemosphere280:130725. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130725

39

Kim H. M. Long N. P. Min J. E. Anh N. H. Kim S. J. Yoon S. J. et al (2020). Comprehensive phenotyping and multi-omic profiling in the toxicity assessment of nanopolystyrene with different surface properties.J. Hazard. Mater.399:123005. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123005

40

Lesniak A. Salvati A. Santos-Martinez M. J. Radomski M. W. Dawson K. A. Aberg C. (2013). Nanoparticle adhesion to the cell membrane and its effect on nano-particle uptake efficiency.J. Am. Chem. Soc.1351438–1444. 10.1021/ja309812z

41

Li X. He E. Jiang K. Peijnenburg W. J. G. M. Qiu H. (2020). The crucial role of a protein corona in determining the aggregation kinetics and colloidal stability of polystyrene nanoplastics.Water Res.190:116742. 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116742

42

Lin W. Jiang R. Hu S. Xiao X. Wu J. Wei S. et al (2019). Investigating the toxicities of different functionalized polystyrene nanoplastics on Daphnia magna.Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.180509–516. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.05.036

43

Liu L. Zheng H. Luan L. Luo X. Wang X. Lu H. et al (2021). Functionalized polystyrene nanoplastic-induced energy homeostasis imbalance and the immunomodulation dysfunction of marine clams (Meretrix meretrix) at environmentally relevant concentrations.Environ. Sci. Nano82030–2048. 10.1039/d1en00212k

44

Liu N. Tang M. Ding J. (2019). The interaction between nanoparticles-protein corona complex and cells and its toxic effect on cells.Chemosphere245:125624. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125624

45

Liu X. Ma J. Yang C. Wang L. Tang J. (2020). The toxicity effects of nano/microplastics on an antibiotic producing strain – Streptomyces coelicolor M145.Sci. Total Environ.764:142804. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142804

46

Luan L. Wang X. Zheng H. Liu L. Luo X. Li F. (2019). Differential toxicity of functionalized polystyrene microplastics to clams (Meretrix meretrix) at three key development stages of life history.Mar. Pollut. Bull.139346–354. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.01.003

47

Manfra L. Rotini A. Bergami E. Grassi G. Faleri C. Corsi I. (2017). Comparative ecotoxicity of polystyrene nanoparticles in natural seawater and reconstituted seawater using the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis.Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.145557–563. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.07.068

48

Marques-Santos L. F. Grassi G. Bergami E. Faleri C. Balbi T. Salis A. et al (2018). Cationic polystyrene nanoparticle and the sea urchin immune system: biocorona formation, cell toxicity, and multixenobiotic resistance phenotype.Nanotoxicology121–21. 10.1080/17435390.2018.1482378

49

Mateos-Cárdenas A. van Pelt F. N. A. M. O’Halloran J. Jansen M. A. K. (2021). Adsorption, uptake and toxicity of micro- and nanoplastics: effects on terrestrial plants and aquatic macrophytes.Environ. Pollut.284:117183. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117183

50

Matthews S. Mai L. Jeong C. B. Lee J. S. Zeng E. Y. Xu E. G. (2021). Key mechanisms of micro- and nanoplastic (MNP) toxicity across taxonomic groups.Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol.247:109056. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2021.109056

51

Miao L. Hou J. You G. Liu Z. Liu S. Li T. et al (2019). Acute effects of nanoplastics and microplastics on periphytic biofilms depending on particle size, concentration and surface modification.Environ. Pollut.255(Pt. 2):113300. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113300

52

Natarajan L. Jenifer M. A. Chandrasekaran N. Suraishkumar G. K. Mukherjee A. (2021). Polystyrene nanoplastics diminish the toxic effects of Nano-TiO2 in marine algae Chlorella sp.Environ. Res.204:112400. 10.1016/j.envres.2021.1

53

Natarajan L. Omer S. Jetly N. Jenifer M. A. Chandrasekaran N. Suraishkumar G. K. et al (2020). Eco-corona formation lessens the toxic effects of polystyrene nanoplastics towards marine microalgae Chlorella sp.Environ. Res.188:109842. 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109842

54

Nel A. E. Mädler L. Velegol D. Xia T. Hoek E. M. V. Somasundaran P. et al (2009). Understanding biophysicochemical interactions at the nano–bio interface.Nat. Mater.8543–557. 10.1038/nmat2442

55

Ning Q. Wang D. An J. Ding Q. Huang Z. Zou Y. et al (2021). Combined effects of nanosized polystyrene and erythromycin on bacterial growth and resistance mutations in Escherichia coli.J. Hazard. Mater.422:126858. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126858

56

Nolte T. M. Hartmann N. B. Kleijn J. M. Garnæs J. van de Meent D. Jan Hendriks A. et al (2017). The toxicity of plastic nanoparticles to green algae as influenced by surface modification, medium hardness and cellular adsorption.Aquat. Toxicol.18311–20. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.12.005

57

Paget V. Dekali S. Kortulewski T. Grall R. Gamez C. Blazy K. et al (2015). Specific uptake and genotoxicity induced by polystyrene nanobeads with distinct surface chemistry on human lung epithelial cells and macrophages.PLoS One10:e0123297. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123297

58

Pan D. Vargas-Morales O. Zern B. Anselmo A. C. Gupta V. Zakrewsky M. et al (2016). The effect of polymeric nanoparticles on biocompatibility of carrier red blood cells.PLoS One11:e0152074. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152074

59

Qian J. He X. Wang P. Xu B. Li K. Lu B. et al (2021). Effects of polystyrene nanoplastics on extracellular polymeric substance composition of activated sludge: the role of surface functional groups.Environ. Pollut.279:116904. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116904

60

Qin L. Duan Z. Cheng H. Wang Y. Zhang H. Zhu Z. et al (2021). Size-dependent impact of polystyrene microplastics on the toxicity of cadmium through altering neutrophil expression and metabolic regulation in zebrafish larvae.Environ. Pollut.291:118169. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118169

61

Qu M. Qiu Y. Kong Y. Wang D. (2019). Amino modification enhances reproductive toxicity of nanopolystyrene on gonad development and reproductive capacity in nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.Environ. Pollut.254(Pt. A):112978. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.112978

62

Raghnaill M. N. Bramini M. Ye D. Couraud P. O. Romero I. A. Weksler B. et al (2014). Paracrine signaling of inflammatory cytokines from an in vitro blood brain barrier model upon exposure to polymeric nanoparticles.Analyst139923–930. 10.1039/C3AN01621H

63

Rochman C. M. (2018). Microplastics research-from sink to source.Science36028–29. 10.1126/science.aar7734

64

Roshanzadeh A. Oyunbaatar N. E. Ganjbakhsh S. E. Park S. Kim D. S. Kanade P. P. et al (2021). Exposure to nanoplastics impairs collective contractility of neonatal cardiomyocytes under electrical synchronizatio.Biomaterials278:121175. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121175

65

Roshanzadeh A. Park S. Ehteshamzadeh Ganjbakhsh S. Park J. Lee D. H. Lee S. et al (2020). Surface Charge-dependent cytotoxicity of plastic nanoparticles in alveolar cells under cyclic stretches.Nano Lett.207168–7176. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02463

66

Saavedra J. Stoll S. Slaveykova V. I. (2019). Influence of nanoplastic surface charge on eco-corona formation, aggregation and toxicity to freshwater zooplankton.Environ. Pollut.252715–722. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.135

67

Schirinzi G. F. Llorca M. Seró R. Moyano E. Barceló D. Abad E. et al (2019). Trace analysis of polystyrene microplastics in natural waters.Chemosphere236:124321. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.07.052

68

Schultz C. L. Bart S. Lahive E. Spurgeon D. J. (2021). What is on the outside matters—surface charge and dissolve organic matter association affect the toxicity and physiological mode of action of polystyrene nanoplastics to C. elegans.Environ. Sci. Technol.556065–6075. 10.1021/acs.est.0c07121

69

Seoane M. González-Fernández C. Soudant P. Huvet A. Esperanza M. Cid Á et al (2019). Polystyrene microbeads modulate the energy metabolism of the marine diatom Chaetoceros neogracile.Environ. Pollut.251363–371. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.142

70

Shen M. Zhang Y. Zhu Y. Song B. Zeng G. Hu D. et al (2019). Recent advances in toxicological research of nanoplastics in the environment: a review.Environ. Pollut.252(Pt. A)511–521. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.102

71

Sun H. Lei C. Xu J. Li R. (2021). Foliar uptake and leaf-to-root translocation of nanoplastics with different coating charge in maize plants.J. Hazard. Mater.416:125854. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125854

72

Sun L. Liao K. Wang D. (2020). Comparison of transgenerational reproductive toxicity induced by pristine and amino modified nanoplastics in Caenorhabditis elegans.Sci. Total Environ.768:144362. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144362

73

Sun M. Ding R. Ma Y. Sun Q. Ren X. Sun Z. et al (2021). Cardiovascular toxicity assessment of polyethylene nanoplastics on developing zebrafish embryos.Chemosphere282:131124. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131124

74

Sun X. D. Yuan X. Z. Jia Y. Feng L. J. Zhu F. P. Dong S. S. et al (2020). Differentially charged nanoplastics demonstrate distinct accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana.Nat. Nanotechnol.15755–760. 10.1038/s41565-020-0707-4

75

Sun X. Chen B. Li Q. Liu N. Xia B. Zhu L. et al (2018). Toxicities of polystyrene nano- and microplastics toward marine bacterium Halomonas alkaliphila.Sci. Total Environ.6421378–1385. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.141

76

Tallec K. Huvet A. Di Poi C. González-Fernández C. Lambert C. Petton B. et al (2018). Nanoplastics impaired oyster free living stages, gametes and embryos.Environ. Pollut.2421226–1235.

77

Taylor S. E. Pearce C. I. Sanguinet K. A. Hu D. Chrisler W. B. Kim Y. M. et al (2020). Polystyrene nano- and microplastic accumulation at Arabidopsis and wheat root cap cells, but no evidence for uptake into roots.Environ. Sci. Nano71942–1953. 10.1039/d0en00309c

78

Varó I. Perini A. Torreblanca A. Garcia Y. Bergami E. Vannuccini M. L. et al (2019). Time-dependent effects of polystyrene nanoparticles in brine shrimp Artemia franciscana at physiological, biochemical and molecular levels.Sci. Total Environ.675570–580. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.157

79

Walczak A. P. Kramer E. Hendriksen P. J. M. Tromp P. Helsper J. P. F. G. van der Zande M. et al (2015). Translocation of differently sized and charged polystyrene nanoparticles in vitro intestinal cell models of increasing complexity.Nanotoxicology9453–461. 10.3109/17435390.2014.944599

80

Wang F. Yu L. Monopoli M. P. Sandin P. Mahon E. Salvati A. et al (2013). The biomolecular corona is retained during nanoparticle uptake and protects the cells from the damage induced by cationic nanoparticles until degraded in the lysosomes.Nanomedicine91159–1168. 10.1016/j.nano.2013.04.010

81

Wang X. Liu L. Zheng H. Wang M. Fu Y. Luo X. et al (2019). Polystyrene microplastics impaired the feeding and swimming behavior of mysid shrimp Neomysis japonica.Mar. Pollut. Bull.50:110660. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110660

82

Wu J. Jiang R. Lin W. Ouyang G. (2019). Effect of salinity and humic acid on the aggregation and toxicity of polystyrene nanoplastics with different functional groups and charges.Environ. Pollut.245836–843.

83

Xu D. Ma Y. Han X. Chen Y. (2021). Systematic toxicity evaluation of polystyrene nanoplastics on mice and molecular mechanism investigation about their internalization into Caco-2 cells.J. Hazard. Mater.417:126092. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126092

84

Yaripour S. Huuskonen H. Rahman T. Keklinen J. Akkanen J. Magris M. et al (2021). Pre-fertilization exposure of sperm to nano-sized plastic particles decreases offspring size and swimming performance in the European whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus).Environ. Pollut.291:118196. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118196

85

Yilimulati M. Wang L. Ma X. Yang C. Habibul N. (2020). Adsorption of ciprofloxacin to functionalized nano-sized polystyrene plastic: kinetics, thermochemistry and toxicity.Sci. Total Environ.750:142370. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142370

86

Yu Z. Song S. Xu X. Ma Q. Lu Y. (2021). Sources, migration, accumulation and influence of microplastics in terrestrial plant communities.Environ. Exp. Bot.192:104635. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104635

87

Zhang K. Hamidian A. H. Tubić A. Zhang Y. Fang J. K. H. Wu C. et al (2021). Understanding plastic degradation and microplastic formation in the environment: a review.Environ. Pollut.274:116554. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116554

88

Zhao T. Tan L. Zhu X. Huang W. Wang J. (2020). Size-dependent oxidative stress effect of nano/micro-scaled polystyrene on Karenia mikimotoi.Mar. Pollut. Bull.154:111074. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111074

Summary

Keywords

nanoplastic, functional group modification, surface charge, toxic effect, mechanism

Citation

Zhang H, Cheng H, Wang Y, Duan Z, Cui W, Shi Y and Qin L (2022) Influence of Functional Group Modification on the Toxicity of Nanoplastics. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:800782. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.800782

Received

24 October 2021

Accepted

10 December 2021

Published

11 January 2022

Volume

8 - 2021

Edited by

Xiangrong Xu, South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), China

Reviewed by

Mingkai Xu, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (UCAS), China; Chun Ciara Chen, Shenzhen University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Zhang, Cheng, Wang, Duan, Cui, Shi and Qin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhenghua Duan, duanzhenghua@mail.nankai.edu.cnLi Qin, ql-tj@163.com

This article was submitted to Marine Pollution, a section of the journal Frontiers in Marine Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.