- Graduate School of Urban Environmental Sciences, Tokyo Metropolitan University, Hachiouji, Tokyo, Japan

All coastal states are expected to establish marine protected areas (MPAs) in line with international targets. For most, this will mean a radical increase in the amount of marine area protected in this way. In order to achieve effective MPAs, the opinions of stakeholders must be carefully considered. This article examines the views of marine extractive users (people engaged in fishery and mining industries) in three coastal countries, the United Kingdom, Canada, and New Zealand, using public comments submitted in response to recent proposals for new MPAs. Specifically, I focus on practically ideal size, duration, required information for regulation, burden of proof and post-designation monitoring of MPAs. Therefore, the gathered material was analyzed to capture views on four issues: 1) to what extents MPAs should target geographical and time scale?; 2) to what extents MPAs should conserve objects and regulate activities based on limited evidence?; 3) who should bear the burden of proof with respect to the environmental impact of regulated activities?; and 4) who and how monitoring and research on ecosystems should be done in MPAs? The study finds that some extractive users oppose the large geographic/temporal scales of MPAs especially when these are based on the application of the precautionary approach. Others accepted these but use them to argue that their own activities are environmentally insignificant. Further, the arguments of some extractive users in favor of their industrial use of MPAs are also considered. These views were commonly found across all three countries, indicating that users in countries committed to the MPA project hold views that challenge this commitment. These findings suggest that challenges to the achievement of MPA targets lie ahead but also suggest new avenues of research and potential solutions. The paper makes six proposals for adjusting the application of the precautionary approach and related targets and regulations. In all cases, my results reinforce the importance of dialogue with marine extractive users for effective MPA reforms at the national and international levels.

1 Introduction

1.1 Introduction of the study

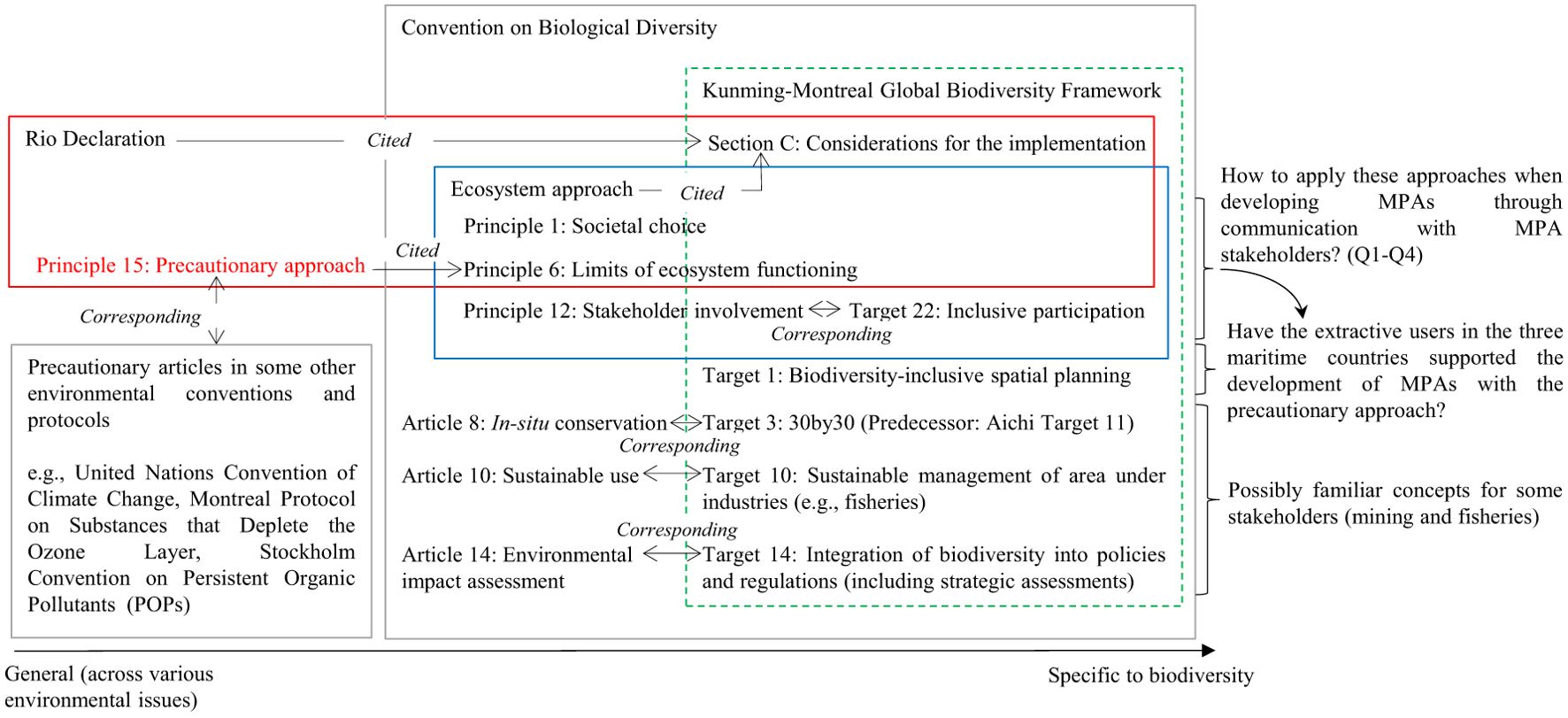

The 15th Conference of the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD-COP15) set a global target known as Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which included Target 3 that at least 30% of marine areas should be “conserved and managed” by 2030 (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD), 2022). The target is now known as “30by30”, while the same objective has been advocated by a few countries already before 2020 (e.g., Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs of the United Kingdom, 2018). Simultaneously, the framework includes other relevant targets (Figure 1), contributing to the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Figure 1. Relationship between international frameworks and relevant approaches of marine protected areas.

Regarding Target 3 of the framework, protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures are considered means to achieve, while protected area has been defined as “means a geographically defined area which is designated or regulated and managed to achieve specific conservation objectives” according to Article 2 of the convention. The 7th Conference of Parties of the convention also agreed on a decision that mentioned the definition of marine and coastal protected area adopted by its ad hoc technical expert group (SCBD, 2004a). Thereafter, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) offered a similar definition of protected area and also a protected area management category system according to the management objectives of such areas (Dudley, 2008). Depending on the context and stakeholders, the goals of protection are diverse, ranging from conserving biodiversity, securing ecosystem services, sequestering carbon, and protecting the human rights of the local people (Corson et al., 2014).

As a result, there are now many kinds of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) with many different rules. So far, studies have examined the global development of MPAs, mainly in terms of coverage (Boonzaier and Pauly, 2016; Gannon et al., 2017; O’Leary et al., 2018; SCBD, 2020). More recent categorization systems consider not only the quantity but also quality (objective and/or regulations) of MPAs (Pike et al., 2024). Given that the range of activities regulated/permitted varies depending on MPAs (Andradi-Brown et al., 2023), Horta e Costa et al. (2016) developed a new regulation-based MPA classification system.

Most of these features of MPAs (e.g., area, objective, regulation) are likely to have been determined through communication among MPA stakeholders, which is a key to MPA success (Di Cintio et al., 2023). Typically, in this communication stakeholders have the opportunity to submit comments on proposed MPA plans, though their comments are not necessarily reflected on the plans. The involvement of a wide range of stakeholders is a core feature of the ecosystem approach as established by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention as they worked to implement the convention (Fish, 2011). Principle 12 explicitly calls for stakeholder participation whereas Principle 1 embraces the importance of societal choice in ecosystem management, such as different values related to economic and cultural well-being, intergenerational equity and even transparency of decision-making (SCBD, 2004b). This approach was agreed among the parties of the convention as a basic approach to achieve the main objectives of the convention, being cited in Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (SCBD, 2022) (Figure 1).

Principle 6 of the ecosystem approach (SCBD, 2004b), Principle 15 of the Rio Declaration (United Nations, 1992), and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (SCBD, 2022) all incorporate the “precautionary approach”, making this principle a foundation of the 30by30 plan. This approach stipulates that a lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason to delay measures against environmental threats (Cameron and Abouchar, 1991). Therefore, in the face of uncertainty, the precautionary approach recommends protecting larger areas, more permanently, and limiting a greater number of activities. This approach has been incorporated into international treaties and protocols across various environmental fields (Harremoës et al., 2002) (Figure 1), though how this principle should be applied practice is debatable in the field of marine environmental protection (VanderZwaag, 2002; Gullett, 2021; Pentz and Klenk, 2022).

MPA stakeholders usually comprise public authorities, local residents, marine conservationists, extractive users, and non-extractive users (e.g., people engaged in tourism and their clients). Therefore, there is a wide variety of stakeholders with differing views on conservation stemming from a range of factors (Jentoft et al., 2012; Corson et al., 2014; Pentz and Klenk, 2022). Of the various activities carried out within marine areas, the impacts of extractive uses are potentially most significant: the support of extractive users and their compliance with MPA restrictions are essential for the establishment and long-term maintenance of MPAs. In other words, involving such stakeholders in MPA decision-making is crucial for effective MPAs with strong compliance (Arias et al., 2015). Furthermore, their local marine knowledge is important for designation and management of MPAs particularly when scientific information is scarce (Johannes et al., 2000). Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework also acknowledges such contribution and rights of indigenous peoples and local communities in its implementation (SCBD, 2022).

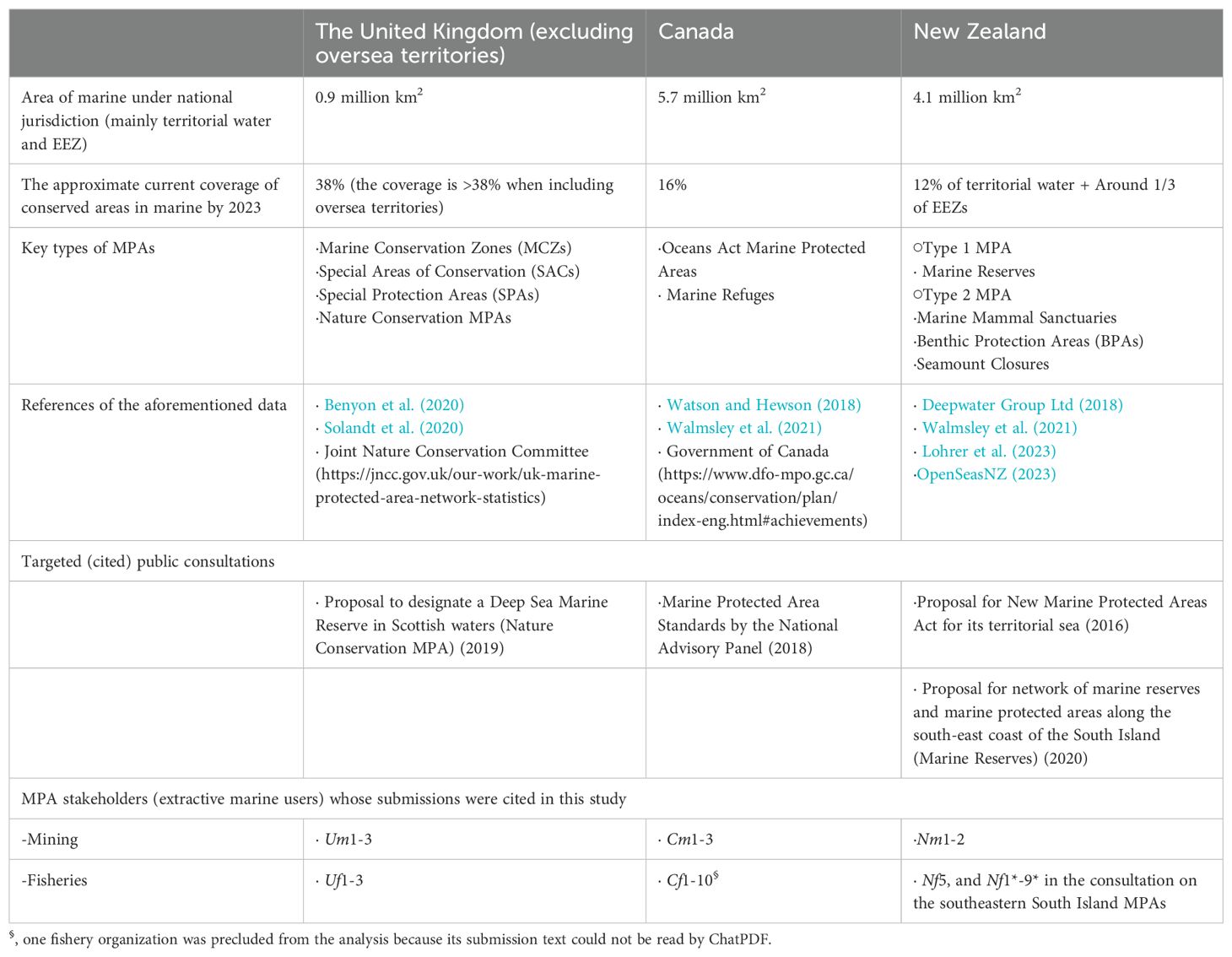

This article examines the views of extractive users with respect to MPAs, with particular emphasis on the precautionary approach. The study drew upon data from three maritime counties, the UK, Canada, and New Zealand (Table 1), to see how users view MPA development and to explore whether and how conservation science can address their concerns and respond to their arguments. In this paper, I focus on the use of the precautionary approach in MPA planning and design, leaving aside arguments for and against MPA legitimacy in improving marine biodiversity. Specifically, I focus on practically ideal size, duration, required information for regulation, burden of proof and post-designation monitoring of MPAs. This is because MPA authorities need to address such issues through communication with MPA stakeholders when establishing and maintaining MPAs, as noted by Boersma and Parrish (1999) in their discussion of “Reserve design”. If they strictly follow the precautionary approach, MPA authorities should then favor long-lasting, large and strictly regulated MPAs until someone proves they are unnecessary. MPA authorities would also prefer strong burden of proof on people who want to do an activity to prove its harmlessness. Nevertheless, such ways may not be feasible and/or agreed with MPA stakeholders, and MPA authorities may want or need to explore more practical solutions.

Table 1. The profile of the three examined countries together with the cited submissions in each public consultation.

This study uses data from three maritime countries which have signed on to 30by30 to investigate how extractive users of marine areas view the development of new MPAs. I then compare these perspectives with those associated with the precautionary approach. Finally, I discuss possible proposals for future research and practice to address their argument and concerns by adjusting the application of the precautionary approach and others (e.g., targets and regulations) to MPA implementation.

1.2 Review of relevant studies and remaining research gaps

Based on the argument in the earlier section, this paper explores the following questions relating to extractive users’ perspectives on Q1-Q4:

Q1) to what extents MPAs should target geographical scale (coverage area) and time scale (duration)?

Q2) to what extents MPAs should conserve objects and regulate activities based on limited evidence?

Q3) who should bear the burden of proof with respect to the environmental impact of regulated activities?

Q4) who and how monitoring and research on ecosystems should be done in MPAs?

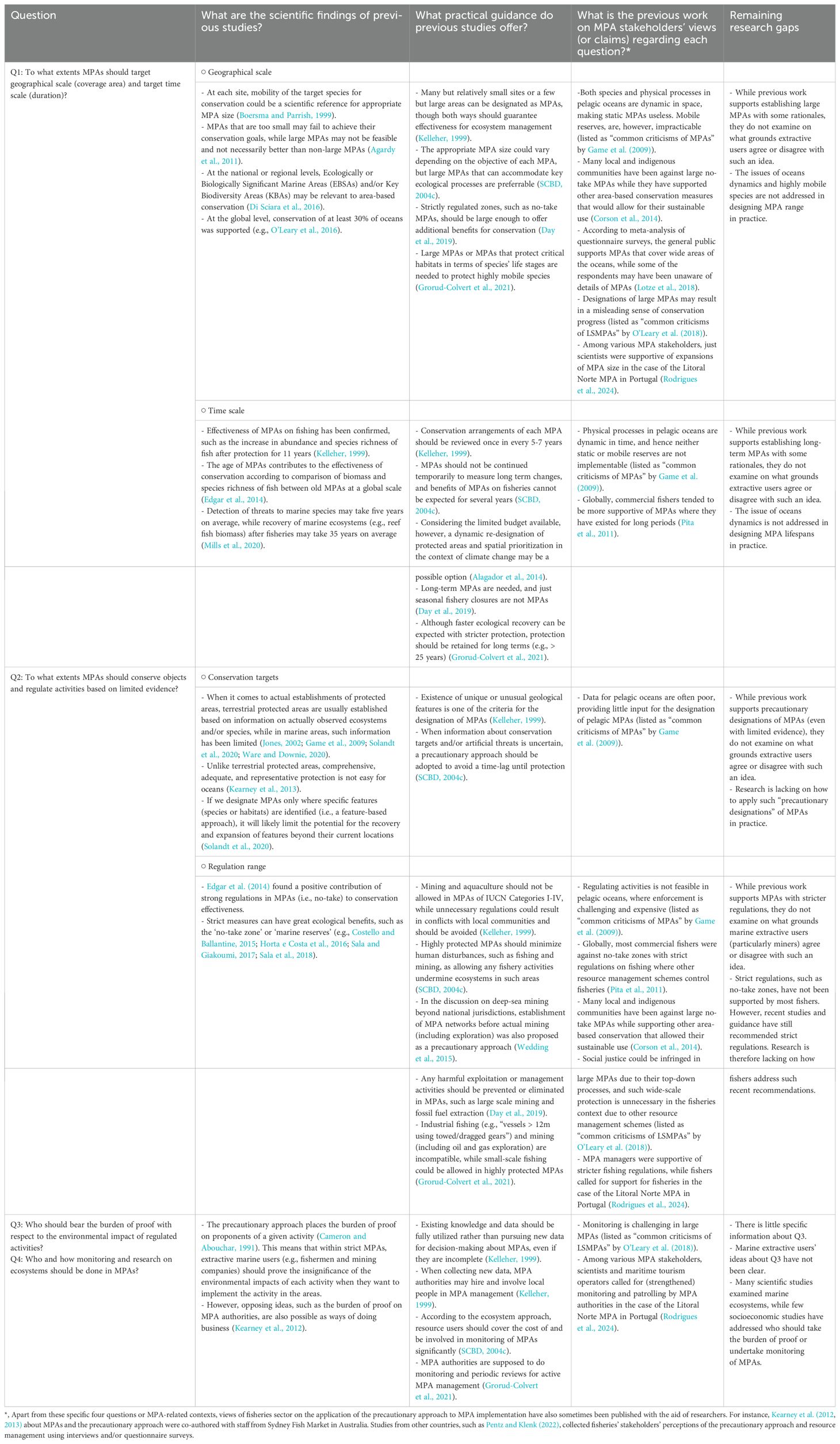

Relevant studies on these questions are then collected to identify research insights and remaining gaps (Table 2). A number of guidelines have been published regarding MPAs, and I focus on those under the Convention on Biological Diversity as main references. To complement these, I also refer to the publications by IUCN, which has supported the secretariat of the convention for its implementation, together with the “MPA Guide” published in Science (Grorud-Colvert et al., 2021) here.

Regarding stakeholders’ views on MPAs, for instance, Artis et al. (2020) collected personal perspectives on purposes and validity of large-scale MPAs from various MPA stakeholders, mainly governmental staff, finding much support for the idea that large-scale MPAs are a way of precautionary approach to biodiversity conservation. Furthermore, these views by such governmental staff or conservationists could be different from those held by extractive users (Rodrigues et al., 2024). In Table 2, I list a few studies that partially or indirectly uncovered views by MPA stakeholders (typically fishers, tourism operators, tourists, scientists, governmental staff, and local communities) in terms of these questions, including one recent case study of an MPA in Portugal (Rodrigues et al., 2024). Such previous studies have undertaken interviews, group discussions, questionnaire surveys, and/or literature review. To address such controversial points of MPAs, Game et al. (2009) reviewed typical claims about pelagic MPAs, while O’Leary et al. (2018) reviewed the main criticisms of large-scale MPAs (i.e., MPAs with areas of 100,000 km2 or larger) available in some selected academic literature (Table 2). While these studies offer insights from a range of MPA stakeholders, views from mining sector and submissions from MPA stakeholders in public consultation have been rarely documented in previous studies.

As shown in the table, there is still room to explore stakeholders’ views on the application of precautionary approach in MPAs. Besides, public consultation that fully involve MPA stakeholders is crucial for appropriate designation and operation of MPAs (Kelleher, 1999; SCBD, 2004b). In other words, such stakeholders’ participation in MPA designs makes MPA stakeholders likely to trust MPA authorities and accept MPAs (Rodrigues et al., 2024), and hence their views in public consultations deserve close investigation.

To address these gaps, I examine comments made by extractive marine users in three countries that proposed, prepared or recently completed expansions of MPAs. These comments were made during the period of public consultation and were still available for analysis. Public comments complement (contrast with) surveys and other academic work by their relationship to specific real-world proposals, as well as because respondents have the chance to think through their views and express themselves at length, which allow us to understand their argument in details.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Targeted countries

The three targeted countries, the UK, Canada, and New Zealand, are leaders in maritime conservation for the following reasons. First, these countries have remarkably large EEZ areas (they are ranked within the top ten countries worldwide) and have been vigorously addressing marine nature conservation and resource management by adopting different approaches, even before their recent work on MPAs (Alder et al., 2010). Second, these countries proposed and reviewed national MPA systems within the last ten years. All or at least some stakeholders’ submissions from public consultation were available in English for the current study. Third, these three countries have actively participated in CBD discussions, being leaders in establishing and implementing global targets on marine conservation, including 30by30 (Table 1).

In particular, the UK has been chairing the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People (High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, 2021) and the Global Ocean Alliance (Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs of the United Kingdom, 2020), which also promote the idea of 30by30. The same country led discussion on 30by30 among G7 countries, resulting in the G7 2030 Nature Compact (Cabinet Office of the United Kingdom, 2021). Canada, a G7 country, supported the compact too, and also joined the two coalitions.

To introduce the treatment of MPAs in each country, I start with the UK, which published its marine strategy in 2012 and updated it in 2019 (Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs of the United Kingdom, 2019a), though the public consultation on the strategy did not disclose original submission texts (Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs of the United Kingdom, 2019b). This strategy sets out how the UK would pursue Good Environmental Status (GES) in its seas, and a number of MPAs (including MPAs of the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic) using the feature-based approach, which focuses on specific species and habitats for protection (Solandt et al., 2020). However, some GES requirements were not met in 2018; hence, the updated marine strategy describes how to realize the GES for the next cycle (2018 - 2024). The UK has increased MPA coverage in its seas, such as the designation of Deep-Sea Marine Reserve in West of Scotland in 2020. Along with such efforts, the United Kingdom government (2018) proposed the idea of 30by30 and thereafter led the discussion under the CBD in making the global agreement with 30by30. The coverage of conserved marine areas around the UK mainland is 38% (Joint Nature Conservation Committee of the UK, 2023), while the same country is developing marine conservation around its overseas territories.

MPAs in Canada were limited (0.64% of Canada’s oceans in 2009 (Canadian Federal Government, 2009)). The regulations on activities in these MPAs were determined individually, in accordance with the federal Oceans Act (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2024). In 2017, Canadian scientists requested that responsible federal ministers amend the Ocean Act in order to facilitate better MPA planning. This led to the establishment of a national advisory panel (Watson and Hewson, 2018). Based on its work between April and September 2018, Canada finally adopted, in April 2019, new MPA protection standards (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2019), which prohibit oil and gas extraction, mining, dumping, and bottom trawling to improve the quality of its MPAs (Watson and Hewson, 2018; Walmsley et al., 2021). In parallel with this standard reform, not only new MPAs but also marine refuges have been continuously established in Canada, resulting in a high marine protection coverage of more than 15% by 2023 (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2024).

In New Zealand, the MPA policy and implementation plan (Department of Conservation and the Ministry of Fisheries of New Zealand, 2005) was created with the aim of protecting 10% of New Zealand’s marine environment by 2010. In line with this plan, New Zealand established strictly protected MPAs that were designed to protect areas for scientific study (designated “marine reserves”). These covered 10% of New Zealand’s territorial seas by 2015 (Scott, 2016; Mossop, 2020). Subsequently, improving MPA systems in New Zealand’s territorial sea was proposed in 2016, and four new types of MPAs were proposed (Ministry for the Environment of New Zealand, 2016). Regulated activities in such protected areas vary depending on the MPA type. In seabed reserves, seabed mining, bottom trawl fishing, and dredging are prohibited. However, this system reform targeted territorial waters, but not its EEZ or continental shelf (Scott, 2016; Mossop, 2020). Simultaneously, new MPAs have been designed and established. This includes six marine reserves southeast of South Island, which were proposed for public consultation in 2020, and these are scheduled to come into force by the end of 2024. With benthic protection areas and seamount area closures, a third of the total EEZ of New Zealand has been already covered since 2007 (Deepwater Group Ltd, 2018; Walmsley et al., 2021; Lohrer et al., 2023; OpenSeasNZ, 2023).

There are some other countries that led discussion on 30by30, such as France and Costa Rica (High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, 2021). I refrained from targeting these countries by prioritizing English-speaking countries, however.

2.2 Methods

For this study I searched for public comments submitted by organizations representing fisheries and mining organizations from the three selected countries on new proposals for mainly national MPA systems/strategies. No submissions from individuals were included in the study. Because comments from extractive users about the selected cases were often missing, I also collected information on a few additional MPA cases. All selected comments submitted by fisheries and mining organizations that were identified by name were selected and examined in the targeted consultations in the UK (n = 6) and Canada (n = 13) (Table 1), while just accessible comments from (not all) organizational submitters were done in New Zealand (n = 12 including two submissions from the same organization) (see below and Supplementary Figure 1 for details). A comment identifier was then assigned to only those cited in the article (e.g. Um1) in the following text by anonymizing the submitters. Here, the first letter in the submission identifier indicates the country from which the submission was cited (U: the UK, C: Canada, N: New Zealand). The second letter in the identifier indicates the industry of the submitter (m: mining, f: fisheries). The last number of the identifier (e.g., 1, 2, …) was then given according to the alphabetic order of submitter’s name.

In the UK, due to unavailability of submission texts in the public consultation about its marine strategy (Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs of the United Kingdom, 2019a), the public consultation about the proposal to designate the aforementioned deep-sea marine reserve in Scottish waters in 2019 was employed in the current study. It is the largest national MPA (107,720km2) in Europe. This consultation collected and disclosed names and responses of 43 submitters, including three mining and three fisheries organizations (Um1-3, Uf1-3) (Scottish Government, 2020).

In Canada, the National Advisory Panel on MPA Standards collected 111 submissions from individuals or organizations during the process of creating new protection standards for Canadian MPAs between April and July 2018. All submitted comments were then published on the Canadian government website, along with information on the submitters (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2018). Only organizational submissions from the extractive users were examined in this study (Cm1-3, Cf1-10).

In New Zealand, the Ministry for the Environment, Department of Conservation, and the Ministry for Primary Industries collected approximately 5,400 public submissions between January and March 2016 during the process of reforming the MPA system for New Zealand’s territorial waters (Bamford, 2018). However, the government of New Zealand did not disclose the submissions on their website, although such submissions were uploaded by some submitters on their websites. I therefore collected them through keyword searches (‘New Zealand’, ‘marine protected area’, and ‘submission’) on the Internet (Nm1-2 and Nf5). To supplement the limited data on New Zealand, public comments gathered in the consultation on the aforementioned establishment of the southeastern South Island marine protected areas in 2020, which disclosed information on submitter names and submitted texts, were also examined here (i.e., Nf1*-9*). More details are available in Supplementary Figure 1.

All stakeholders provided their comments in response to open calls, while evidence of individual invitations for specific stakeholders to such consultations was not confirmed. In the consultations on MPAs in Scottish waters in the UK, submitters used a specific format related to a series of specific questions (Supplementary Table 1). Among the examined Canadian submissions, only Cm1 gave its answers to specific key questions along with its general comments, while all the other submissions were written in an open-ended format. In New Zealand, some stakeholders gave their comments in response to a series of specific questions in the two consultations. Although all the submitters of the consultations cited in my study gave their submissions in a free format, two submitters (Nm1 and Nf5) additionally gave responses to some of the posed questions.

Each proposed MPA covered distinctive geographical areas, activities and stakeholder configurations, and comments made by stakeholders were frequently contextual and specific. In this study, a generative AI tool, ChatPDF (ChatPDF GmbH, 2024) was used to extract answers to the four questions from the submission texts. Specifically, I submitted a PDF of each submission to this analysis and entered the aforementioned four questions consecutively by replacing “MPAs” with “marine protected areas (MPAs)” in Q1 so that ChatPDF can recognize the meaning of the acronym. The submission file by Nf3* was compressed before text mining. This analysis was conducted in February 2025 after two tests with similar questions and all the targeted PDFs in October and December 2024. The accuracy of single automatic extraction by ChatPDF is equivalent to that of double manual extractions by humans according to randomized trials, while high analysis reproducibility of ChatPDF is also confirmed (Sun et al., 2024). Considering the limitation of the automatic text mining, I also read through the examined submissions and extracted some key parts from them.

3 Results

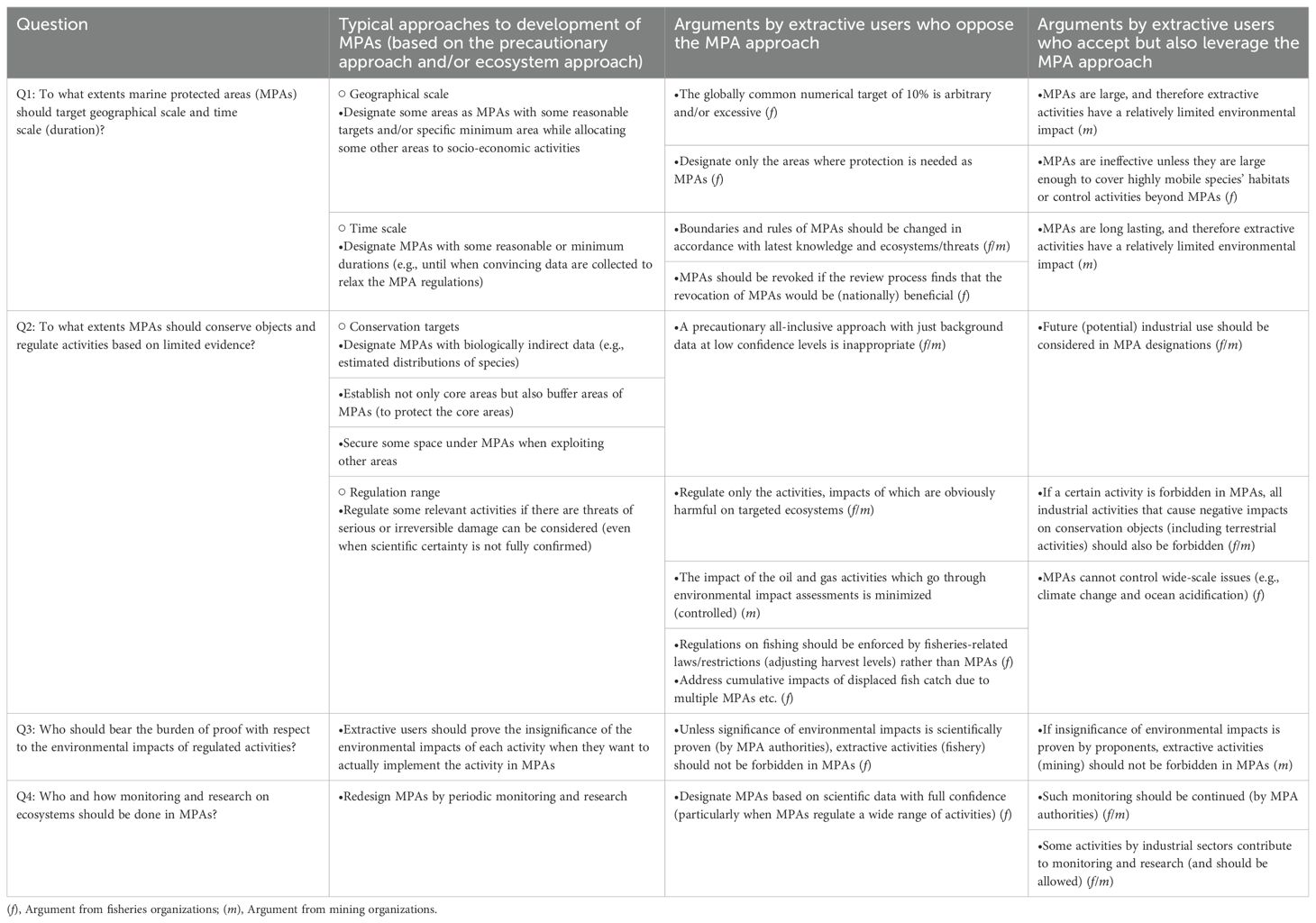

Among the cited submissions, for instance, Nf5 prepared a 53-page document with many citations to address the new proposal of the MPA Act in New Zealand. Other submissions also provided meticulous arguments including interesting logic (see below for details). Identified typical views are shown in Table 3, and the details of the views, including conflicts among the extractive users’ views, are shown from the four questions below. Although numbers of the submissions that showed certain views/patterns were included below for reference as minimum numbers, possibly other submitters gave similar views implicitly or partially. Furthermore, the returned answers by ChatPDF in response to the four questions are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Herein, the specific information on the submitters, such as their names, were anonymized with square brackets. Yet, considering the limitation of the automatic text mining, some relevant comments (mainly emphasized or unique comments that seem to be general across sites, but not site-specific comments) manually extracted are also shown in the non-exhaustive list in the same table. The submissions of Uf1 and Uf3 were substantially same though the submitters were different.

3.1 Appropriate scales of MPA

Three extractive users explicitly disagreed with the 10% target of MPAs by 2020 or more ambitious targets (e.g., Cf6). In addition, fisheries organizations in New Zealand were concerned about the “excessive” establishment of MPAs without any limitations (Nf5). The same organizations, together with Cf1, also stated that MPAs can preclude human use of large areas of ocean space, possibly resulting in negative economic impacts.

Five extractive users (Cf1, Nm1, Nm2, Nf4*, Nf6*) advocated the importance of precise understanding about spatial locations of ecosystems, threats and protected areas together with their zoning (e.g., integrated marine spatial planning). Cf1 argued that the protection of the Dungeness crab (Metacarcinus magister) would require large MPAs, which implied a difficulty for practical implementation. Therefore, these extractive users requested the spatial explicit boundaries of managed zones, while they sometimes used the supposed need for large-scale MPAs strategically to support conclusions that endorsed their activities or made the case for other spatial management choices than MPAs.

Regarding the timescale of MPAs, Nm2 underscored the relatively short duration of mining activities in long-term MPAs. Cf1 and Cf7 mentioned that non-static marine ecosystems should be considered when introducing MPAs that preclude human use from ocean space. Some users (Nf5 and Nm1) explicitly called for a review of existing MPAs (every five years according to Nf5) to take into account the latest knowledge. In addition, Nm1, Nf3*, and Nf5 proposed that when considering new MPA proposals, the effects of the proposals not only on existing but also on future uses and values of the areas (including economic impacts) should be considered. For instance, Nf5 commented that resource extraction should be allowed within the MPAs of New Zealand’s EEZs if resources of national interest (including significant positive economic values) are discovered. Meanwhile, Nf6* analyzed the impact of MPAs on their fishery for a 25-year period and projected an economic loss for the fishery. In other words, the submitter expressed concern that a long-term MPA would have negative economic consequences.

Five submitters were also concerned about cumulative impacts of displaced fish catch due to multiple MPAs along with other regulations (Nf4*-Nf7* and Nf9*).

3.2 Required evidence for regulation

Five extractive users opposed MPA designations on the grounds that there was weak biological evidence, a position directly in contrast to the precautionary principle. For instance, Uf3 opined that further data should be collected to justify MPAs that protect deep-sea features (background data at low confidence levels are insufficient). Um2 also stated that MPA designations rely excessively on modelled data without any real baseline information. Considering the low confidence levels of the underpinning data, Uf1 was confused as to how conservation objectives can be defined on the basis of evidence. Um1 concluded that wide-ranging MPAs should not be designed based on data at low confidence levels. Nf5 declared that a gap analysis should be conducted to identify habitats or ecosystems that are underrepresented by existing MPAs and are at risk of threats that are not well addressed by existing management mechanisms (i.e., “a risk-based approach”). In addition to these ideas, Nf6* underscored the importance of each case study including scientific evidence rather than general theories or studies based on model assumptions. The same extractive user then argued that it could not assess the proposals of MPAs in the south-east coast of the South Island in New Zealand because no clear scientific data supporting the designation were presented in the consultation process. Nm1 proposed that because of limited scientific knowledge of deep ocean ecosystems and relevant threats, coastal areas should be prioritized for protection.

3.3 Appropriate regulation scope

Around ten extractive users stated that certain activities of fisheries or mining have limited environmental impacts (and therefore should be permitted or not be regulated). For instance, Cf3-4 commented that their aquaculture does not threaten marine ecosystems, concluding that their aquaculture should be permitted in the boundaries of each MPA. Likewise, Nm2 proposed that prospecting for and exploration of mineral resources should be allowed in MPAs because of the limited impact of these activities on ecosystems. The cited organization also suggested that mining activity should be allowed if a mining company proves that their specific mining activity does not compromise conservation objects. A similar industrial coalition, Cm1, suggested that routine drilling activities should be allowed in MPAs if each proponent can show that environmental effects are limited. Cm3 also argued that no evidence of harmful impacts of the mining industry on offshore fish have been observed, while the industry has made conservation efforts, including flexible movement of planned anchors upon detection of indicator species of vulnerable marine ecosystems (VME), such as cold-water corals (i.e., move-on rule). According to Nm1, these activities by the industry are common around MPAs, or if appropriate, within MPAs, globally. Although the following quotes might have been influenced by the specific areas which the submitters considered, Uf1 and Uf3 argued that mid-water fishing activities should not be regulated in deep Scottish MPAs as such activities may not detrimentally affect conservation objectives. Um2-3 suggested that oil and gas activities should be permitted if they undergo environmental impact assessments (including monitoring and modelling) and satisfy specific requirements. Likewise, submissions about the MPA proposal for the south-east coast of the South Island indicate that fisheries organizations (characterized as “Nf*”) did not support particularly marine reserves in New Zealand.

Extractive users also raised different potential problems of no-take zones in relation to aboriginal rights (Cf5) and property rights of owners of quotas, which were allocated according to the Canada’s Fisheries Act 1996 (Part 4 Quota management system) or the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (e.g., Article 62) (Nf5). Nf1* pointed out the necessity of compensation to the fisheries parties who are affected by MPA regulations.

It is noteworthy that six extractive users called for regulations or at least pointed out the lack of regulations on other extractive users’ specific activities that might have strong negative impacts on ecosystems. For instance, Cf8 suggested that oil and gas exploration and development should be completely ruled out from MPAs for obvious and perceptual reasons. Meanwhile, Cm2 pointed out that almost all of the damage to benthic populations was caused by bottom trawling, and that existing fisheries exclusion areas did not cover the main area of such fishing. Cf9 proposed that if fishing is forbidden in MPAs, all industrial activities that cause negative impacts on conservation objects should also be forbidden. Nf5 and Nf7* made similar requests (e.g., request for regulation on riverine sediments and resulting nutrient loading from lands) for marine reserves. Nf6* also emphasized the impacts of non-fishery drivers, such as land-based sedimentation and secondary invasion of non-native species, saying that MPAs cannot address these impacts.

3.4 Monitoring and research on ecosystems

Five submitters stated that monitoring (including the collection of baseline information), regular review, and adaptive management (by MPA authorities) is necessary. For instance, Uf1 was of the view that given the wide area of designation, further work is needed to monitor the effect and impact of MPA management measures. Furthermore, Cf10 proposed that extractive research activities, such as trawl surveys, should be allowed to ensure the monitoring of MPAs. Nm1 stated that the activities of the petroleum and mineral sectors contribute to the understanding of specific marine areas that are commercially valuable through environmental impact assessments. Nonetheless, the same organization also proposed that a science-based process for establishing and managing MPAs is important. This would require ongoing investment in research covering even MPA networks by not only the petroleum or mineral sectors but also other stakeholders, such as relevant governmental sections (Nm1).

4 Discussion

There were two clusters of opinions of extractive users from both fishery and mining sectors in this study: opinions that reject the necessity of MPA designations, particularly those that regulate activities of these sectors, and those that accept such MPA designations but demand additional measures and/or argue the irrelevance of their own activities within MPAs. In the latter pattern, extractive users often requested the implementation of challenging/unrealistic measures, such as MPAs that were large enough to cover highly mobile species habitats or that regulated many extractive or other damaging activities, including land-based pollution.

Consequently, such extractive users challenge the concepts of the MPA and/or the precautionary approach per se. Although some of their opinions may not be supported by science (e.g., Cf6’s disagreement with the ≥10% target of MPAs), others may offer lessons and insights to minimize the gap between extractive users and MPA authorities. Such lessons and insights will allow us to find a middle ground in the practical implementation of MPAs. More specific discussion, including differences in opinions between fishery and mining sectors and six specific proposals based on the discussion about Q1-Q4, are provided below.

4.1 MPA scale

Direct application of globally common numerical targets of MPAs to national practice may be fair at the global level, but its fairness was questioned by some users, particularly those from the fisheries sector, consistent with results by Agardy et al. (2016). The result of the present study indicates that fishermen may be more seriously concerned about geographically wide-scale restrictions than are miners perhaps because many fishing activities require utilization of large and constantly shifting areas. To address such ideas, while numerical targets need to be considered, they (the targets) could be adjusted to actual application in each country by taking into account country’s unique natural and socio-economic conditions. For instance, each country could figure out such numerical targets and/or geographical ranges for MPA designations based on Ecologically or Biologically Significant Areas (EBSA) identified through the CBD process (SCBD, 2023) or similar spatially explicit information. Even when adopting global numerical targets in national policy-making, additional rationales based on domestic information may be useful to convince extractive users to cooperate (Proposal 1).

Additionally, extractive users argued for adaptive/flexible designations and management of MPAs. This is reasonable due to dynamic ocean ecosystems, as Alagador et al. (2014) proposed a dynamic re-designation of protected areas and spatial prioritization in the context of climate change, for instance. Further, adaptive/flexible MPA designations may also address the issue of cumulative impacts of multiple MPAs. Thus, national conservation efforts should include consideration of such adaptive redesignations while some long-term MPAs are also necessary for specific vulnerable and/or slowly growing ecosystems such as VMEs (Clark et al., 2016) (Proposal 2). If it is agreed that exploitation benefits outweigh protection benefits through the societal choice noted in the ecosystem approach, for instance, degazetting of some protected areas might be necessary. However, notably, the societal choice should be carefully made particularly when comparing environmental concern vs. other factors (Fish, 2011). For instance, benefits of exploitation can be expected in a short-term while those of conservation can be in a long-term. It is also noteworthy that cumulative impact is a central concept in ecosystem management (e.g., Duinker and Greig (2006)).

Extractive users also tended to support only the regulation of activities that are empirically proven to be harmful (“threat/risk-based approach”). In addition, some extractive users proposed that the impact of fishing or mining activities that are already subject to fishery harvest controls or environmental impact assessments (including environmental monitoring and modelling) can be minimized (controlled) without MPA regulations. However, minimizing regulations in MPAs can undermine the effectiveness of MPAs (Horta e Costa et al., 2016). In this respect, relevant guidance about MPAs cited in Table 2 may be useful in reconsidering the requirements for and effectiveness of MPAs. It is also true that such guidelines could be revised in response to the critical views on MPAs identified in the current study. For instance, permanence as well as the precautionary design of MPAs were pointed out as principles of highly protected MPAs by the secretariat, but these were questioned by marine stakeholders. Besides, revised guidelines can shed light on under what conditions additional contribution of MPAs to conservation can be expected in comparison with fishery harvest controls or environmental impact assessments. For instance, the aforementioned move-on rules are common and can be improved further with scientific thresholds (Geange et al., 2020).

Assuming that some fishing/mining activities could impact ecosystems, some extractive users may have animosity against other extractive users’ activities (e.g., animosity against bottom trawling by those who don’t do it). Several extractive users suggested that if a certain activity is forbidden in MPAs, then all industrial activities (including terrestrial activities) that negatively affect conservation objects should be forbidden. In other words, they requested equal regulations for all marine activities regardless of the activities’ impacts and/or tried to divert the regulator’s attention to other specific areas/industries/activities. However, we should undertake regulations that not only consider equality of regulation limits but also the environmental impact of each activity to achieve the original purpose of MPAs (Proposal 3). In this regard, the landscape approach, as defined by Reed et al. (2015), could provide an equitable solution as it considers a wider geographic and thematic scope that extends beyond the boundary of any proposed protected area (Sayer et al., 2013, 2017). Regulating land-based activities to protect adjacent marine areas using MPA systems could be reasonable according to the landscape approach as well as the ecosystem approach, although land-based activities may be more easily controlled by other rules tailored to the land. Hence, even though the proposed regulations are not easy to implement in a timely and/or systematically manner, how to address the challenges that MPAs cannot control may deserve to be addressed when proposing new MPAs.

A few extractive users of mining argued that in large and/or long-lasting MPAs, the relative environmental impact of their extractive activities would be negligible. Therefore, this frames potential targets of regulation with respect to their relative rather than absolute impact. According to Ohsawa and Duinker (2014), proponents often attempt to make their carbon footprints look insignificant by comparing them with the carbon emissions from large bodies, such as nations or provinces, in environmental impact assessments (this is known as the “scale trick”). Similarly, large spatial and temporal scales of MPAs can be used to express the relative insignificance of environmental impacts by extractive users. Originally, however, MPAs were not supposed to be compared in such ways; hence, some guidance on how to measure and express environmental impact of each activity in relation to MPA is useful in addressing such issues. For instance, the Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation (Conservation Measures Partnership, 2020) shows how to identify critical threats, while the concept of “serious harm” of mining activities to the marine environment in areas beyond national jurisdiction has been discussed in the community of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) (Leduc et al., 2024).

4.2 MPA restrictions

According to the precautionary approach, MPAs could be considered to be at least an interim conservation tool when insufficient scientific evidence is available. In particular, when the precise locations of certain species and/or ecosystems are not well understood, large interim MPAs that cover the possible locations of such conservation targets should be considered. However, in large MPAs, collecting data is time consuming and costly; hence, data per unit area is likely to be limited. On the other hand, some extractive users whom the current study targeted argued that to regulate a wide range of activities in MPAs, scientific data with full confidence is necessary. They argue that only highly certain data would justify regulating their activities.

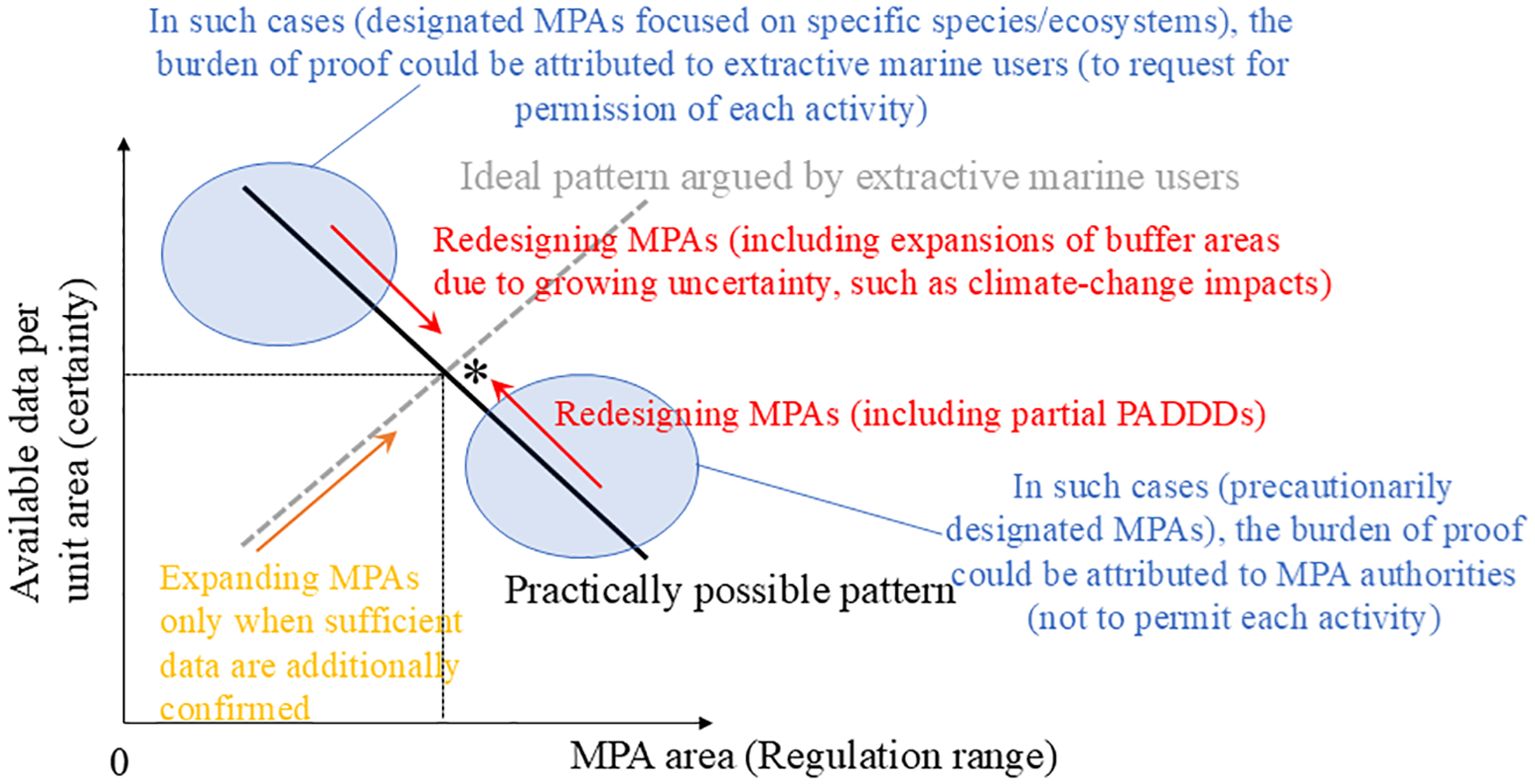

There are two contradictory ideas here: the need to establish large-scale MPAs and the need for adequate data when establishing MPAs. There may be a middle ground, however. In Figure 2, the curve of “Practically possible pattern” for redesigning MPAs can be considered depending on changes of confidence (certainty) of available scientific data. For instance, precise information on the location of targeted species/ecosystems could allow us to narrow down the MPA ranges (i.e., partial PADDDs). However, the level of data confidence may decline over time. Climate change impacts can increase uncertainty regarding the future of species/ecosystems. In such cases, the MPAs may need to be expanded and networked (Heller and Zavaleta, 2009; Bates et al., 2019). In such redesigning, the middle ground (intersection marked with asterisk) indicated by the curve labeled “Ideal pattern for extractive marine users” deserves consideration (Proposal 4). Some methods (e.g., acoustic seabed mapping) can only be used for identifying habitats, whereas others can be useful for collecting species using qualitative (e.g., eDNA) or even quantitative (e.g., imaging sonar) methods (McGeady et al., 2023). Therefore, it will be interesting to explore which methods and data types are cost effective but still convincing in the context of MPA establishment.

Figure 2. Possible relationships between MPA area (regulation range) and confidence (certainty) of scientific data.

Precautionary/interim MPA designations are needed to secure possible habitats (including future habitats) for marine ecosystems (and their migration) where available information is limited. However, the effectiveness of such precautionarily designated MPAs can be undermined by climate change (Pentz and Klenk, 2023). The degree to which marine stakeholders accept future projections based on climate-change assumptions (e.g., climate scenarios embedded in the future projections and/or statistical certainty of the projections) as justification for designations of MPAs which regulate current marine use may deserve further investigation (Proposal 5). Interestingly, some extractive users invoked the idea of “precautionary” decision-making to protect extraction potential instead of ecological potential.

4.3 Burden of proof

Extractive users in the mining industry (rather than in fisheries) were more likely to accept the burden of proof. Unlike those engaged in seabed mining, fishers are unfamiliar with environmental impact assessments. In addition, precautionary regulations may be more strongly disagreed with in an industry with such a long history (Lauck et al., 1998; Kriebel et al., 2001). Particularly in coastal areas, fishermen may feel uncomfortable and/or that they are being treated unfairly when required to assume the burden of proof.

If the burden of proof is heavy for extractive users, such as if it requires onsite surveys for proof, only a few extractive users may be able to obtain permission to do what they want to do. Likewise, if the burden of proof is assigned to conservation authorities alone, most activities may not stop, even within MPAs. This idea needs to be examined as, to my knowledge, no past studies confirmed it. If it is true, a good balance between the two could be then pursued to make MPA regulations functional (Proposal 6). For instance, in the core zones of the MPAs, the proof can be assigned mainly to extractive users. On the other hand, in the buffer zones of MPAs, this could be mainly assigned to conservation authorities (i.e., conservation authorities could suspend the activities of extractive users only when they find some tangible evidence of serious harm). In this approach, buffer zones would be established with limited evidence based on an essentially precautionary approach, but approvals of each regulated activity would be done on the basis of a lighter burden of proof on extractive users than in core zones. Another way is for extractive users and conservation authorities to cooperate (e.g., to perform on-site co-surveys) to determine the significance or insignificance of the environmental impacts of each activity. However, the burden allocation is a value judgment and therefore should be finally determined among actual stakeholders respectively.

4.4 Research limitations and future works

Based on the findings and discussion in this study, future studies should consider addressing a few but new challenges. For instance, there is room to investigate conflicts among extractive users’ ideas by engaging extractive users of various sectors. Future research could also investigate the perspective that some extractive users had, which suggested the use of the precautionary approach for the protection of future extraction rather than ecological potential. Likewise, further research is needed to determine how reasonable it is to use the concept of “cumulative impact” of MPAs on industrial use.

This study had also certain limitations that could be addressed in future work. First, this study only drew on publicly available data, limiting the extent to which I can extrapolate across systems and places. The countries will possibly reform their MPA systems again based on 30by30, and hence public consultations through reform processes could hopefully reveal the latest opinions of MPA stakeholders and offer new research opportunities. For such future research, it would be beneficial if MPA authorities were to disclose the collected submissions from MPA stakeholders through public consultations as much as possible. Second, given the employed document analysis method, the study was an exploratory attempt to document a wide range of ideas and opinions but it was likely not representative of all users’ views. Any quantitative assessment of specific ideas (i.e., identifying which ideas were most popular) was avoided in the current study. With a sufficient number of samples, however, such assessments will be possible. Further, large language model-based AI tools, such as ChatPDF, are not perfect and required manual reading at the same time. To examine systematically consistencies/inconsistencies in opinions among stakeholders, social network analysis may also be helpful (Veríssimo and Campbell, 2015). Third, the current study focused on the four questions specifically and also suggested how to find the middle ground for all of these questions. Yet, there are perhaps also differences in values at play that extractive users and MPA authorities may not be able to reconcile. The four questions in the study also leads me to extrapolate additional challenges for the future. Future work could cover additional themes, including, e.g., perspectives on penalties as they relate to MPA design and enforcement. In other words, the most appropriate values in various metrics for implementation, including the levels of penalties, could be further explored in future research. Finally, the study scope could be expanded to other types of MPA stakeholders and also other countries. For instance, then Nova Scotia premier McNeil (2018) was suspicious of precautionary MPA designations in the examined public consultations in Canada, arguing that such an approach was not scientific. It is therefore interesting to what degree such oppositions against the precautionary approach exist among local governments. Moreover, considerably different results might be obtained from other countries (e.g., the countries which disagreed with the idea of 30by30 through the CBD negotiation). However, unlike academic publications, such comments from the public may become unavailable unless they are documented in permanently available databases or publications (such as in the current study). Some of the comments cited in this study are actually no longer available on the Internet. Thus, documenting their views from public consultations is useful but only possible for just a certain period after actual consultations.

5 Conclusion

This current study identified a few important patterns that have barely been discussed by previous literature from the comments given by marine stakeholders (extractive users) in three maritime countries. First (answer to Q1), while some extractive users were just against large and/or long-lasting MPAs, other extractive users strategically used such large spatial/temporal scales to underscore the environmental insignificance of their activities or choices. This framing is similar to the behavior known as the “scale trick.” The latter argument relates to the ongoing question of how much of an activity, if any, should be permitted within each MPA, and relevant standards/guidelines may be helpful to address this issue. Second (Q2/4), some extractive users opposed the precautionary approach by arguing that scientific data with full confidence should be necessary to designate (regulate activities in) large MPAs. In contrast, some extractive users invoked the idea of “precautionary” decision-making to protect future harvest opportunities for fish and minerals. Third (Q2), extractive users often requested the minimization of regulations in MPAs. They also tended to favor non-MPA approaches which each industrial sector has been familiar with to control their own activities. In contrast, other extractive users requested equal regulations on all industrial activities that negatively impacted conservation objects (including terrestrial activities), which could be partly considered in actual regulations based on the landscape approach. Fourth (Q3), while some mining stakeholders commented that they could hold some responsibility for burden of proof, few fishery stakeholders claimed this responsibility for themselves.

In conclusion, even though further MPA development, known as 30by30, has been recently discussed and supported at the global level, the extractive users’ views on MPAs were diverse in the examined leading countries in marine conservation. Some examples of possible resolutions (the aforementioned six proposals) were given in this study and hopefully will be beneficial for future MPA discussions, particularly how to adjust the application of the precautionary approach to MPA implementation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (CSTI), Crossministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (SIP), the 3rd period of SIP “Smart Infrastructure Management System” Grant Number JPJ012187 (Funding agency: Public Works Research Institute).

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to constructive and helpful comments of three reviewers.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1446357/full#supplementary-material

References

Agardy T., Claudet J., Days J. C. (2016). ‘Dangerous Targets’ revisited: Old dangers in new contexts plague marine protected areas. Aquat. Conserv.: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 26, 7–23. doi: 10.1002/aqc.2675

Agardy T., Di Sciara G. N., Christie P. (2011). Mind the gap: addressing the shortcomings of marine protected areas through large scale marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 35, 226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2010.10.006

Alagador D., Cerdeira J. O., Araújo M. B. (2014). Shifting protected areas: scheduling spatial priorities under climate change. J. Appl. Ecol. 51, 703–713. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12230

Alder J., Cullis-Suzuki S., Karpouzi V., Kaschner K., Mondoux S., Swartz W., et al. (2010). Aggregate performance in managing marine ecosystems in 53 maritime countries. Mar. Policy 34, 468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2009.10.001

Andradi-Brown D. A., Veverka L., Amkieltiela, Crane N. L., Estradivari, Fox H. E., et al. (2023). Diversity in marine protected area regulations: Protection approaches for locally appropriate marine management. Front. Mar. Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1099579

Arias A., Cinner J. E., Jones R. E., Pressey R. L. (2015). Levels and drivers of fishers’ compliance with marine protected areas. Ecol. Soc 20, 19. doi: 10.5751/ES-07999-200419

Artis E., Gray N. J., Campbell L. M., Gruby R. L., Acton L., Zigler S. B., et al. (2020). Stakeholder perspectives on large-scale marine protected areas. PloS One 15, e0238574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238574

Dudley D.(2008). Best practice protected area guidelines series no. 21 guidelines for applying protected area management categories. Available online at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/9243 (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Bamford T. (2018). PA reform in Aotearoa National Advisory Panel on Marine Protected Area Standards. Available online at: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/oceans/documents/conservation/advisorypanel-comiteconseil/submissions-soumises/Aotearoa-MPA-reform-NAP-MPA-workshop-Ottawa-March-2018-eng.pdf (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Bates A. E., Cooke R. S., Duncan M. I., Edgar G. J., Bruno J. F., Benedetti-Cecchi L., et al. (2019). Climate resilience in marine protected areas and the ‘Protection Paradox’. Biol. Conserv. 236, 305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.05.005

Benyon R., Barham P., Edwards J., Kaiser M., Owens S., de Rozarieux N., et al. (2020). Benyon review into highly protected marine areas final report. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5eda52cbe90e071b78731f0d/hpma-review-final-report.pdf (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Boersma P. D., Parrish J. K. (1999). Limiting abuse: marine protected areas, a limited solution. Ecol. Econ. 31, 287–304. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00085-3

Boonzaier L., Pauly D. (2016). Marine protection targets: an updated assessment of global progress. Oryx. 50, 27–35. doi: 10.1017/S0030605315000848

Cabinet Office of the United Kingdom (2021). Policy paper G7 2030 Nature Compact. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/g7-2030-nature-compact/g7-2030-nature-compact (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Cameron J., Abouchar J. (1991). The precautionary principle is a fundamental principle of law and policy for protecting the global environment. Boston Col. Int. Comp. Law Rev. 14, 1–27.

Canadian Federal Government (2009). Canada’s 4th national report to the united nations convention on biological diversity. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/ca/ca-nr-04-en.pdf (Accessed September 3, 2020).

ChatPDF GmbH (2024). ChatPDF. Available online at: https://www.chatpdf.com/ (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Clark M. R., Althaus F., Schlacher T. A., Williams A., Bowden D. A., Rowden A. A. (2016). The impacts of deep-sea fisheries on benthic communities: a review. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 73, i51–i69. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsv123

Conservation Measures Partnership (2020). Open standards for the practice of conservation version 4.0. Available online at: https://conservationstandards.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/10/CMP-Open-Standards-for-the-Practice-of-Conservation-v4.0.pdf (Accessed October 19, 2024).

Corson C., Gruby R., Witter R., Hagerman S., Suarez D., Greenberg S., et al. (2014). Everyone’s solution? Defining and redefining protected areas in the Convention on Biological Diversity. Conserv. Soc 12, 190–202. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.138421

Costello M. J., Ballantine B. (2015). Biodiversity conservation should focus on no-take marine reserves: 94% of marine protected areas allow fishing. Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 507–509. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2015.06.011

Day J., Dudley N., Hockings M., Holmes G., Laffoley D., Stolton S., et al. (2019). Guidelines for applying the IUCN protected area management categories to marine protected areas. 2nd ed. (Gland. Switzerland: IUCN). Available at: https://repository.oceanbestpractices.org/bitstream/handle/11329/1176/PAG-019-2nd%20ed.-En%281%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed April 16, 2025).

Deepwater Group Ltd (2018). New zealand’s marine protected areas. Available online at: https://deepwatergroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/NZ-MPAs.pdf (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs of the United Kingdom (2018). Press release Gove calls for 30 per cent of world’s oceans to be protected by 2030. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/gove-calls-for-30-per-cent-of-worlds-oceans-to-be-protected-by-2030 (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs of the United Kingdom (2019a). Marine Strategy Part One: UK updated assessment and Good Environmental Status. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f6c8369d3bf7f7238f23151/marine-strategy-part1-october19.pdf (Accessed September 3, 2020).

Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs of the United Kingdom (2019b). Marine Strategy Part One: UK Updated Assessment and Good Environmental Status Summary of responses. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5daf1ce3e5274a5cad31aafb/marine-strategy-part1-summary-of-responses.pdf (Accessed August 3, 2024).

Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs of the United Kingdom (2020). Global Ocean Alliance: 30 countries are now calling for greater ocean protection. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/global-ocean-alliance-30-countries-are-now-calling-for-greater-ocean-protection (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Department of Conservation and the Ministry of Fisheries of New Zealand (2005). Marine protected areas policy and implementation plans. Available online at: https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/conservation/marine-and-coastal/marine-protected-areas/mpa-policy-and-implementation-plan.pdf (Accessed 15 June 2021).

Di Cintio A., Niccolini F., Scipioni S., Bulleri F. (2023). Avoiding “paper parks”: a global literature review on socioeconomic factors underpinning the effectiveness of marine protected areas. Sustainability 15, 4464. doi: 10.3390/su15054464

Di Sciara G. N., Hoyt E., Reeves R., Ardron J., Marsh H., Vongraven D., et al. (2016). Place-based approaches to marine mammal conservation. Aquat. Conserv.: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 26, 85–100. doi: 10.1002/aqc.2642

Duinker P. N., Greig L. A. (2006). The impotence of cumulative effects assessment in Canada: ailments and ideas for redeployment. Env. Manage. 37, 153–161. doi: 10.1007/s00267-004-0240-5

Edgar G. J., Stuart-Smith R. D., Willis T. J., Kininmonth S., Baker S. C., Banks S., et al. (2014). Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas with five key features. Nature 506, 216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature13022

Fish R. D. (2011). Environmental decision making and an ecosystems approach: Some challenges from the perspective of social science. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 35, 671–680. doi: 10.1177/0309133311420941

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2018). Submissions to the national advisory panel on marine protected area standards. Available online at: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/oceans/conservation/advisorypanel-comiteconseil/submissions-soumises/index-eng.html (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2019). National advisory panel on marine protected area standards. Available online at: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/oceans/conservation/advisorypanel-comiteconseil/index-eng.html (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2024). Targets, achievements and reports. Available online at: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/oceans/conservation/index-eng.html (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Game E. T., Grantham H. S., Hobday A. J., Pressey R. L., Lombard A. T., Beckley L. E., et al. (2009). Pelagic protected areas: Missing dimensions in ocean conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.01.011

Gannon P., Seyoum-Edjigu E., Cooper D., Sandwith T., Dias B. F. S., Palmer C. P., et al. (2017). Status and prospects for achieving Aichi Biodiversity Target 11: Implications of national commitments and priority actions. Parks 23, 13–26. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2017.PARKS-23-2PG.en

Geange S. W., Rowden A. A., Nicol S., Bock T., Cryer M. (2020). A data-informed approach for identifying move-on encounter thresholds for vulnerable marine ecosystem indicator taxa. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00155

Grorud-Colvert K., Sullivan-Stack J., Roberts C., Constant V., Horta e Costa B., Pike E. P., et al. (2021). The MPA Guide: A framework to achieve global goals for the ocean. Science 373, eabf0861. doi: 10.1126/science.abf0861

Gullett W. (2021). The contribution of the precautionary principle to marine environmental protection: from making waves to smooth sailing? Front. Int. Environ. Law: Oceans Climate Challenges (Brill Nijhoff). 135, 368–406. doi: 10.1163/9789004372887_015

Harremoës P., Gee D., MacGarvin M., Stirling A., Keys J., Wynne B., et al. (2002). Introduction. The precautionary principle in the 20th century: Late lessons from early warnings (London (England): Earthscan Publications).

Heller N. E., Zavaleta E. S. (2009). Biodiversity management in the face of climate change: a review of 22 years of recommendations. Biol. Conserv. 142, 14–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.10.006

High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People (2021). Ministerial event, open to the public, following official launch by heads of state. Available online at: https://www.hacfornatureandpeople.org/launch-of-high-ambition-coalition-for-nature-and-people-by-over-50-countries-at-one-planet-summit/ (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Horta e Costa B., Claudet J., Franco G., Erzini K., Caro A., Gonçalves E. J. (2016). A regulation-based classification systems for marine protected areas (MPAs). Mar. Policy 72, 192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.06.021

Jentoft S., Pascual-Fernandez J. J., de la Cruz Modino R., Gonzalez-Ramallal M., Chuenpagdee R. (2012). What stakeholders think about marine protected areas: Case studies from Spain. Hum. Ecol. 40, 185–197. doi: 10.1007/s10745-012-9459-6

Johannes R. E., Freeman M. M., Hamilton R. J. (2000). Ignore fishers’ knowledge and miss the boat. . Fish Fisheries 1, 257–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2000.00019.x

Joint Nature Conservation Committee of the UK (2023). UK Marine Protected Area network statistics. Available online at: https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/uk-marine-protected-area-network-statistics (Accessed February 16, 2025).

Jones P. J. (2002). Marine protected area strategies: issues, divergences and the search for middle ground. Rev. fish Biol. fish. 11, 197–216. doi: 10.1023/A:1020327007975

Kearney R., Buxton C. D., Goodsell P., Farebrother G. (2012). Questionable interpretation of the Precautionary Principle in Australia’s implementation of ‘no-take’ marine protected areas. Mar. Policy 36, 592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.02.024

Kearney R., Farebrother G., Buxton C. D., Goodsell P. (2013). How terrestrial management concepts have led to unrealistic expectations of marine protected areas. Mar. Policy 38, 304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.06.006

Kelleher G. (1999). Guidelines for marine protected areas (Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN), xxiv +107. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/pag-003.pdf (Accessed April 16, 2025).

Kriebel D., Tickner J., Epstein P., Lemons J., Levins R., Loechler E. L., et al. (2001). Precautionary principles in environmental science. Environ. Health Persp. 109, 871–876. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109871

Lauck T., Clark C. W., Mangel M., Munro G. R. (1998). Implementing the precautionary principle in fisheries management through marine reserves. Ecol. Appl. 8, S72–S78. doi: 10.2307/2641364

Leduc D., Clark M. R., Rowden A. A., Hyman J., Dambacher J. M., Dunstan P. K., et al. (2024). Moving towards an operational framework for defining serious harm for management of seabed mining. Ocean Coast. Manage. 255, 107252. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2024.107252

Lohrer T., Hewitt J. E., Lohrer A. M., Parsons D. M., Ellis J. I., Stephenson F. (2023). Evidence of rebound effect in New Zealand MPAs: Unintended consequences of spatial management measures. Ocean Coast. Manage. 239, 106595. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106595

Lotze H. K., Guest H., O’Leary J., Tuda A., Wallace D. (2018). Public perceptions of marine threats and protection from around the world. Ocean Coast. Mng. 152, 14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.11.004

McGeady R., Runya R. M., Dooley J. S., Howe J. A., Fox C. J., Wheeler A. J., et al. (2023). A review of new and existing non-extractive techniques for monitoring marine protected areas. Front. Mar. Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1126301

McNeil S. (2018). National advisory panel on marine protected area standards. Available online at: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/oceans/documents/conservation/advisorypanel-comiteconseil/submissions-soumises/Premier-McNeil-MPA-panel-speaking-notes.pdf (Accessed September 3, 2020).

Mills M., Magris R. A., Fuentes M. M., Bonaldo R., Herbst D. F., Lima M. C., et al. (2020). Opportunities to close the gap between science and practice for Marine Protected Areas in Brazil. Persp. Ecol. Conserv. 18, 161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pecon.2020.05.002

Ministry for the Environment of New Zealand (2016). A new marine protected areas act consultation document. Available online at: https://environment.govt.nz/assets/Publications/Files/mpa-consultation-doc.pdf (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Mossop J. (2020). Marine protected areas and area-based management in New Zealand. Asia-Pacific. J. Ocean Law Pol. 5, 169–185. doi: 10.1163/24519391-00501009

O’Leary B. C., Ban N. C., Fernandez M., Friedlander A. M., García-Borboroglu P., Golbuu Y., et al. (2018). Addressing criticisms of large-scale marine protected areas. Bioscience 68, 359–370. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biy021

O’Leary B. C., Winther-Janson M., Bainbridge J. M., Aitken J., Hawkins J. P., Roberts C. M. (2016). Effective coverage targets for ocean protection. Conserv. Lett. 9, 398–404. doi: 10.1111/conl.12247

Ohsawa T., Duinker P. (2014). Climate-change mitigation in Canadian environmental impact assessments. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 32, 222–233. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2014.913761

OpenSeasNZ (2023). Marine conservation section detail report. Pp21. Available online at: https://openseas.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Marine-Conservation_January-2023.pdf (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Pentz B., Klenk N. (2022). Why do fisheries management institutions circumvent precautionary guidelines? J. Env. Manage. 311, 114851. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114851

Pentz B., Klenk N. (2023). Will climate change degrade the efficacy of marine resource management policies? Mar. Policy 148, 105462. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105462

Pike E. P., MacCarthy J. M., Hameed S. O., Harasta N., Grorud-Colvert K., Sullivan-Stack J., et al. (2024). Ocean protection quality is lagging behind quantity: Applying a scientific framework to assess real marine protected area progress against the 30 by 30 target. Conserv. Lett. 17, e13020. doi: 10.1111/conl.13020

Pita C., Pierce G. J., Theodossiou I., Macpherson K. (2011). An overview of commercial fishers’ attitudes towards marine protected areas. Hydrobiologia 670, 289–306. doi: 10.1007/s10750-011-0665-9

Reed J., Deakin L., Sunderland T. (2015). What are ‘Integrated Landscape Approaches’ and how effectively have they been implemented in the tropics: a systematic map protocol. Environ. Evidence 4, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/2047-2382-4-2

Rodrigues J. G., Villasante S., Sousa-Pinto I. (2024). Exploring perceptions to improve the outcomes of a marine protected area. Ecol. Soc 29, 18. doi: 10.5751/ES-15159-290318

Sala E., Giakoumi S. (2017). No-take marine reserves are the most effective protected areas in the ocean. ICES. J. Mar. Sci. 75, 1166–1168. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx059

Sala E., Lubchenco J., Grorud-Colvert K., Novelli C., Roberts C., Sumaila U. R. (2018). Assessing the real progress towards effective ocean protection. Mar. Policy 91, 11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.02.004

Sayer J. A., Margules C., Boedhihartono A. K., Sunderland T., Langston J. D., Reed J., et al. (2017). Measuring the effectiveness of landscape approaches to conservation and development. Sust. Sci. 12, 465–476. doi: 10.1007/s11625-016-0415-z

Sayer J., Sunderland T., Ghazoul J., Pfund J. L., Sheil D., Meijaard E., et al. (2013). Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 110, 8349–8356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210595110

Scott K. N. (2016). Evolving MPA management in New Zealand: Between principles and pragmatism. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 47, 289–307. doi: 10.1080/00908320.2016.1194096

Scottish Government (2020). Proposal to designate a Deep Sea Marine Reserve in Scottish waters Published responses. Available online at: https://consult.gov.scot/marine-scotland/deep-sea-marine-reserve/consultation/published_select_respondent (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD) (2004a).UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/VII/5 Decision adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity at its Seventh Meeting VII/5. In: Marine and coastal biological diversity. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-07/cop-07-dec-05-en.pdf (Accessed February 22, 2025).

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD) (2004b). The ecosystem approach (CBD guidelines) secretariat of CBD. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/ea-text-en.pdf (Accessed June 13, 2021).

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD) (2004c). Technical advice on the establishment and management of a national system of marine and coastal protected areas (CBD Technical Series no.13). Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-13.pdf (Accessed September 3, 2020).

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD) (2020). Global biodiversity outlook 5. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/gbo/gbo5/publication/gbo-5-en.pdf (Accessed June 15, 2021).

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD) (2022). CBD/COP/DEC/15/4 Kunming-Montreal Global biodiversity framework. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf (Accessed April 14, 2024).

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD) (2023). Ecologically or biologically significant marine areas. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/ebsa/ (Accessed October 27, 2024).

Solandt J. L., Mullier T., Elliott S., Sheehan E. (2020). Managing marine protected areas in Europe: Moving from ‘feature-based’ to ‘whole-site’ management of sites. Mar. protected areas (Elsevier), 157–181. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-102698-4.00009-5

Sun Z., Zhang R., Doi S. A., Furuya-Kanamori L., Yu T., Lin L., et al. (2024). How good are large language models for automated data extraction from randomized trials? MedRxiv, 2024–2002. doi: 10.1101/2024.02.20.24303083

United Kingdom government (2018). Press release Gove calls for 30 per cent of world’s oceans to be protected by 2030. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/gove-calls-for-30-per-cent-of-worlds-oceans-to-be-protected-by-2030 (Accessed June 15, 2021).

United Nations (1992). A/CONF351/26 (Vol. I) report of the united nations conference on environment and development. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_CONF351_26_Vol.I_Declaration.pdf (Accessed September 7, 2024).

VanderZwaag D. (2002). The precautionary principle and marine environmental protection: slippery shores, rough seas, and rising normative tides. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 33, 165–188. doi: 10.1080/00908320290054756

Veríssimo D., Campbell B. (2015). Understanding stakeholder conflicts between conservation and hunting in Malta. Biol. Conser. 191, 812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.07.018

Walmsley S., Pack K., Roberts C., Blyth-Skyrme R. (2021). Vulnerable marine ecosystems and fishery move-on-rules - best practice review. Available online at: https://www.msc.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/stakeholders/consultations/impact-assessments/msc-fisheries-standard-review—consultancy-report—vme-and-mor-best-practice-review-(2021).pdf?sfvrsn=66d5e7e4_4 (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Ware S., Downie A. L. (2020). Challenges of habitat mapping to inform marine protected area (MPA) designation and monitoring: An operational perspective. Mar. Policy 111, 103717. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103717

Watson M. M., Hewson S. M. (2018). Securing protection standards for Canada’s marine protected areas. Mar. Policy 95, 117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.07.002

Keywords: burden of proof, ecosystem approach, marine protected areas, precautionary approach, public comments

Citation: Ohsawa T (2025) Unveiling arguments on national system reforms of marine protected areas by extractive marine users in three maritime countries. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1446357. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1446357

Received: 09 June 2024; Accepted: 24 March 2025;

Published: 28 April 2025.

Edited by:

Randi D. Rotjan, Boston University, United StatesReviewed by:

Hugh Govan, University of the South Pacific, FijiKira Sullivan-Wiley, Pew Charitable Trusts, United States

Copyright © 2025 Ohsawa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Takafumi Ohsawa, YWE1NjI1OEBob3RtYWlsLmNvLmpw

Takafumi Ohsawa

Takafumi Ohsawa