- 1Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR)-Central Institute of Freshwater Aquaculture, Bhubaneswar, India

- 2Biosciences and Bioengineering Division, CSIR-National Institute for Interdisciplinary Science and Technology, Thiruvananthapuram, India

- 3Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research (AcSIR), Ghaziabad, India

Introduction: Nannochloropsis oceanica CASA CC201 is a marine microalga valued for its capacity to accumulate high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly essential omega-3 fatty acid EPA. In carp nursery culture, low survival rates from spawn to fry (25–30%) and from fry to fingerling (40–50%) are often attributed to inadequate access to easily digestible, high-quality nutrients. This study evaluated the potential of N. oceanica–derived algae oil as a sustainable dietary lipid source to improve growth, survival, immune responses, and gut enzymatic activity in nursery-reared rohu (Labeo rohita).

Methods: A three-week feeding trial was conducted using four iso-nitrogenous and iso-lipidic diets formulated with fish oil (FO), N. oceanica algae oil (AO), linseed oil (LO), or sunflower oil (SFO). Each diet was randomly assigned to triplicate groups across 12 indoor nursery tanks (2000 L), with 2000 rohu spawn stocked per tank in a completely randomized design. Fish were fed twice daily, aeration was maintained continuously, and weekly water renewal ensured optimal water quality. Growth performance, survival, non-specific immunity parameters (lysozyme, haemolytic, haemagglutination, and myeloperoxidase activities), and digestive enzyme activities (amylase, protease, and lipase) were assessed at the end of the experiment.

Results: The AO diet resulted in the highest survival among nursery rohu, while the FO diet produced the greatest growth performance. Gut enzyme analysis indicated the highest amylase activity in fish fed FO and the highest lipase activity in fish fed AO, with protease showing no marked trend among treatments. No significant differences were detected in non-specific immune parameters across dietary groups.

Discussion: Algae oil derived from N. oceanica demonstrated clear advantages in enhancing survival and lipase activity, outperforming conventional plant oils and offering a viable partial or complete replacement for fish oil in nursery diets. Although FO supported superior growth, AO provided a more sustainable alternative that could improve overall nursery performance without compromising immunity. These findings underscore the potential of microalgal oils as functional and eco-friendly lipid sources for early-stage carp aquaculture.

1 Introduction

Driven by sustainability concerns and economic pressures, a principal focus of aquaculture research in recent decades has been the quest of alternative feed ingredients to partially or completely replace fishmeal and fish oil, without compromising growth performance or welfare of animal (Naylor et al., 2009). This research imperative is intensified by a growing supply-demand disparity, driven by rising aquaculture sector demand for finite marine-derived resources sourced from static global capture fisheries. The resultant supply-demand imbalance has triggered substantial market inflation, with the cost of fishmeal and fish oil escalating by roughly 300% within the last decade (Beal et al., 2018). Owing to their unique nutritional composition, microalgae represent a promising, multi-functional alternative for sustainable aquaculture feed formulations. They are suitable not only as a partial substitute for fishmeal and fish oil but also as a functional feed additive. Their inclusion has been demonstrated to enhance the nutritional value of diets, improve growth performance and survivability, and bolster immunocompetence (Gbadamosi and Lupatsch, 2018).

Microalgae have emerged as a promising feed supplement for humans and animals due to their rich composition of high-quality protein, bioactive compounds, pigments (e.g., chlorophyll and carotenoids), functional ingredients, vitamins, and minerals (Shah et al., 2018). Microalgal biomass serves as a promising, sustainable alternative to conventional fishmeal and fish oil, addressing critical sustainability challenges in aquaculture (Patterson and Gatlin, 2013; Ryckebosch et al., 2014; Haas et al., 2016; Shah et al., 2018). Partial substitution of fishmeal with microalgae biomass in aquafeeds has been shown to improve growth, feed utilization, body composition, and disease resistance in a range of species, including Oncorhynchus mykiss (Dallaire et al., 2007), Ictalurus punctatus (Li et al., 2009), Sparus aurata (Vizcaíno et al., 2014), Clarias gariepinus (Raji et al., 2019), and Trachinotus Ovatus (Zhao et al., 2020). Additional benefits, such as modulated lipid metabolism and improved meat quality, have been documented in Cyprinus carpio varieties (Xiao et al., 2021; Fan et al., 2025).

Nannochloropsis, a resistant unicellular chromophyte with yellowish-green chloroplasts, possesses an extremely resistant cell wall and is high in Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Nannochloropsis oceanica is a marine microalga regarded as a promising alga due to its exceptional capacity to accumulate significant amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids (Udayan et al., 2018; Arumugam et al., 2021). Omega-3 fatty acids, which include eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and α-linolenic acid (ALA), are among the most significant polyunsaturated fatty acids. The EPA content in various Nannochloropsis species ranges from 2.9% to 41.7% of total fatty acids, depending on cultivation conditions in open ponds or closed bioreactors (Ma et al., 2016). Due to their critical role in fundamental physiological processes in animals and humans, Nannochloropsis species have been widely employed in the production of nutraceuticals and feed supplements (Rodolfi et al., 2009). Consequently, these microscopic organisms have garnered significant scientific and commercial interest, establishing them as a promising component for incorporation into sustainable aquaculture practices.

Defatted microalgae from the genus Nannochloropsis represent a viable, sustainable alternative to conventional fishmeal in aquafeeds, supporting circular economy models within aquaculture. Research indicates that inclusion levels are species-specific, with optimal thresholds identified for several key teleosts. For instance, European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) tolerates dietary inclusions of defatted Nannochloropsis sp. meal up to 15% (Valente et al., 2019). Similarly, in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), modest inclusion levels of approximately 10% defatted N. oceanica do not adversely affect performance metrics (Sørensen et al., 2017). Beyond nutritional replacement, dietary supplementation with N. oculata at 5% has been shown to enhance the productive performance and immunocompetence of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), conferring increased resistance against Aeromonas veronii challenge (Abdelghany et al., 2020; Zahran et al., 2023). Furthermore, N. salina can effectively replace up to 10% of the crude protein from fishmeal and soybean meal in diets for red drum (Sciaenops ocellatus) juveniles without significant performance decrements (Patterson and Gatlin, 2013). Collectively, these findings substantiate that low to moderate inclusion levels (5-10%) of defatted Nannochloropsis meal are a promising functional ingredient for sustainable aquafeed, contributing to growth, health, and nutritional quality (Qiao et al., 2019).

While the substitution of fishmeal with dried microalgae biomass in aquafeed for finfish and shrimp has been extensively documented (Ju et al., 2009; Vizcaíno et al., 2014; Tibaldi et al., 2015), the potential of lipid-extracted algal residue as a source of essential fatty acids (EFA) remains comparatively unexplored. The substitution of fish oil with vegetable oils, including canola, sunflower, and linseed, has been extensively investigated. However, a significant limitation of these terrestrial alternatives is their deficiency in n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LC-PUFA) such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) (Miller et al., 2014). Consequently, microalgae-derived oil, which is inherently rich in these critical n-3 LC-PUFAs, presents a promising sustainable alternative to fish oil in aquafeeds.

Partial substitution of fish oil with microalgae biomass has been successfully demonstrated in the diets of several commercially important aquaculture species. Research on olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) indicated that a combination of Schizochytrium sp. (rich in DHA) and Nannochloropsis sp. (rich in EPA) effectively supported growth performance and feed efficiency (Qiao et al., 2014). In a study on European sea bass (D. labrax), Haas et al. (2016) reported that up to 50% of dietary fish oil could be replaced by Nannochloropsis sp. without adverse effects on growth or nutrient retention. For juvenile kuruma shrimp, Oswald et al. (2019) determined the optimum fish oil replacement to be 1.58 g of Nannochloropsis sp. lipid (equivalent to 26.33% of dietary fish oil), which sustained standard growth metrics, survival, and somatic fatty acid composition.

Beyond their nutritional value, microalgae-mediated carbon sequestration has emerged as a sustainable strategy for mitigating anthropogenic CO2 emissions, simultaneously generating biomass for the production of value-added chemicals. Microalgae are remarkably effective carbon sinks, consuming about 1.83 kg of CO2 per kilogram of dry biomass a rate roughly ten times greater than that of terrestrial plants (Kamyab et al., 2017).

Aquaculture has made its record high production of about 94.0 million tons (51% of total) of fish and aquatic animals in 2022, surpassing marine capture fisheries for the first time ever (FAO, 2024). As the world’s population surpasses 9.7 billion by 2050, there will be an increased need for protein-rich foods, making aquaculture vital in tackling this very pertinent issue in future (Wang et al., 2023; Kumari et al., 2024). It is only feasible if a continuous and assured supply of quality fish seed is made available for sustainable aquaculture. Indian major carps have continually dominated the aquaculture landscape, accounting for 87% of India’s total aquaculture production. The nursery phase of L. rohita is a crucial yet challenging stage in carp farming. Under standard practices, survival rates are often suboptimal, typically reported at only 25–30% from spawn to fry and 40–50% from fry to fingerling. This high mortality rate represents a significant bottleneck in the production of stockable seed. Nutrition plays a significant role in growth and survival of in nursery rearing of the carp culture. Non-availability of essential nutrient particularly oil is a major reason for the poor survival and growth, making the nursery rearing of carp less remunerative (Das et al., 2022). Similarly, in grow out culture; nutrition plays a vital role in improving animal productivity as feed accounts for 55 to 60% of the operational cost in intensive system and around 40% in semi-intensive system (Lovell, 1998). Provision of energy dense diets via lipid supplementation is an effective strategy to spare protein and reduce ammonia production in several fish species, including common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Similarly, studies indicate that protein utilization efficiency in fish can be enhanced by partially replacing dietary protein with lipid or carbohydrate (Lovell, 1989). This highlights the critical need for identifying cost-effective and highly efficacious oil sources for advancing scientific and sustainable aquaculture practices. This study evaluated the efficacy of four distinct dietary lipid sources fish oil (FO), N. oceanica algae oil (AO), linseed oil (LO), and sunflower oil (SFO) on growth performance, survival, non-specific immune response, and digestive enzyme activity in nursery-reared rohu, Labeo rohita.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental diets and feeding trial

Four iso-nitrogenous and iso-lipidic experimental diets for nursery rohu was formulated and prepared incorporating fish oil, algae (N. oceanica) oil, linseed oil and sunflower oil, respectively as source of oil and other ingredients like maize, soybean meal, groundnut oil cake, rice bran, fish meal, minerals and vitamin mixture were incorporated in each feed (Table 1) as per BIS specification and fed to nursery rohu of different treatment groups (Khumujam et al., 2024). The raw materials for the fish feed were carefully weighed, pulverized, mixed, extruded, dried and then grinded. A 21-day feeding trial was subsequently conducted at the experimental wet laboratory facility of the ICAR-Central Institute of Freshwater Aquaculture, Kausalyaganga, Bhubaneswar, India. The experiment was conducted under a completely randomized design (CRD). Each of the four dietary treatments was randomly assigned to three replicate tanks (n=3; total tanks = 12). Each 2000 L tank was stocked with 2000 rohu spawn. Continuous aeration was provided to maintain optimum oxygen levels. Water exchange was performed weekly to maintain water quality. Throughout the 21-day feeding trial, fish were fed their respective experimental diets to apparent satiation twice daily. The daily ration was adjusted weekly based on biomass, starting at 300 g per 100,000 spawn for the first week and increasing to 600 g per 100,000 spawn for the second and third weeks. Every day, six hours after feeding, any leftover feed was siphoned off and stored in a hot air oven for assessing feed intake. The fish were weighed weekly to determine the average weight and biomass for each tank. Water quality parameters were monitored fortnightly throughout the study period using standard methods (APHA, 2005) and found within the optimal range. The mean (± SE) values recorded were: temperature, 27.05 ± 0.24 °C; pH, 7.5 ± 0.16; dissolved oxygen, 5.43 ± 0.19 mg L−1 total hardness, 64 ± 4 mg CaCO3 L−1 ammonia-N, 0.66 ± 0.28 mg L−1 and total alkalinity, 76 ± 5 mg CaCO3 L−1.

2.2 Culture condition of N. oceanica in a photobioreactor

N. oceanica was cultured as discussed (Venkatesh and Muthu, 2025; Arumugam et al., 2021) and pure colonies were established using dilution and quadrant streaking techniques. Seawater from Vizhinjam Beach, Kerala, was enriched with De Walne’s medium (sodium nitrate, boric acid, and EDTA disodium salt; Sigma, Himedia) and used as the growth medium. Cultivation was performed in a custom-designed PET bubble column photobioreactor (PBR; internal diameter 29 cm, height 165 cm, wall thickness 0.23–0.28 mm) that could be converted into a stirred tank with an integrated impeller. The reactor operated at 18–25 °C, pH 7–8, and was illuminated with six LED lamps (70 µmol m−2 s−1 16 h light/8 h dark), supplemented by fluorescent lighting (1000 lumens). The PET construction provided high light transmission, low cost compared to acrylic/glass, and supported modules for nutrient delivery, mixing, and extraction.

Approximately 10 L of inoculum was scaled up to a 40 L PBR under controlled aeration, temperature (20–23 °C), and light conditions (70 µmol m−2 s−1 16:8 h cycle). A total of 160 L culture was processed, with harvesting after 11–12 days at pH 7–8. Biomass was collected by centrifugation, washed twice with distilled water, freeze-dried, and stored (Venkatesh and Muthu, 2025). Lipid extraction was carried out from the lyophilized biomass, and the oil was preserved under refrigeration (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. (A) Nannochloropsis oceanica algal oil, and (B) a representative nursery-reared rohu (Labeo rohita) after the 3-week experimental feeding period.

2.3 Lipid extraction from algal biomass

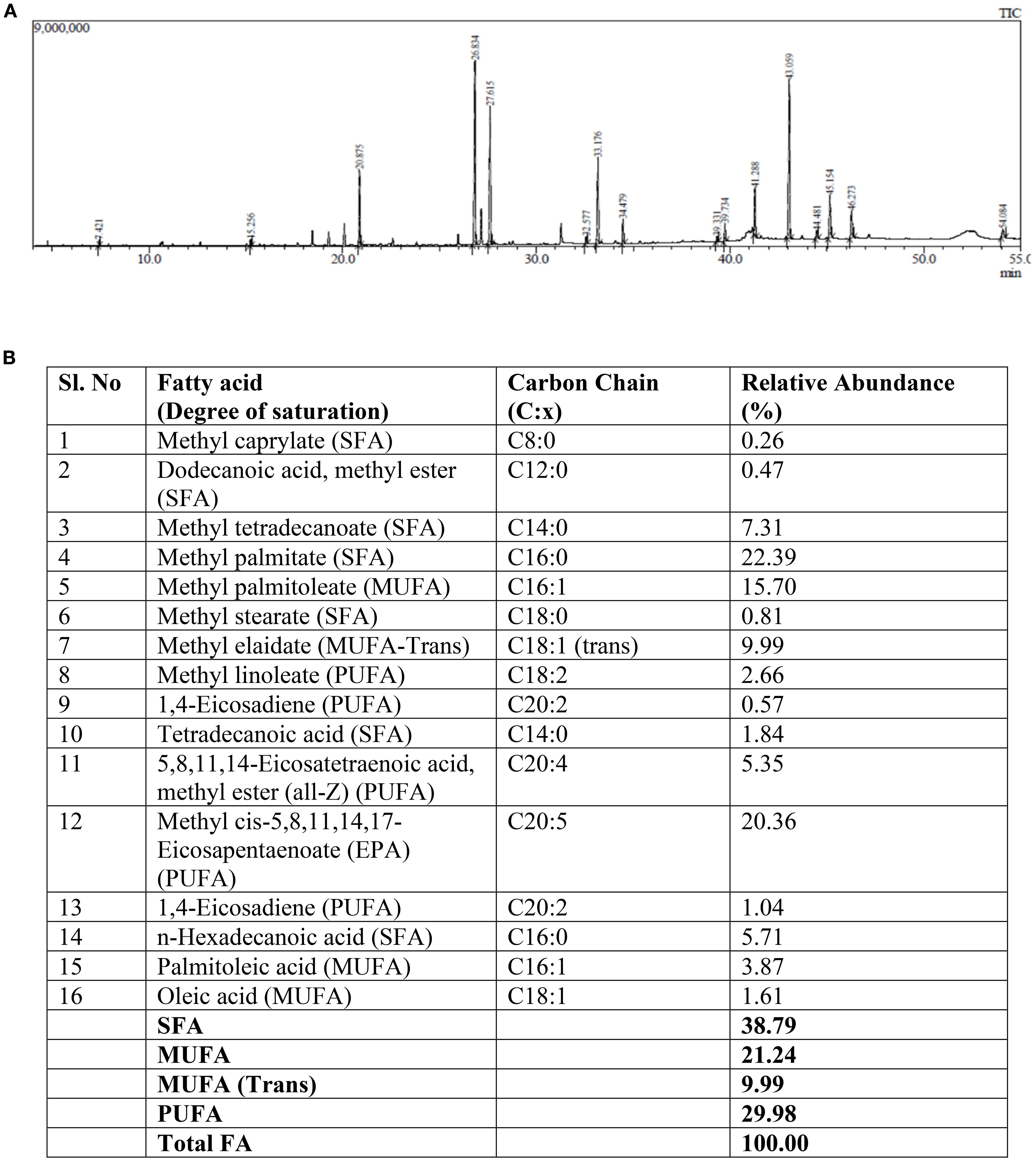

The total lipid extraction was performed as previously reported (Udayan et al., 2018), in brief Lyophilized algal biomass was suspended in 3 volumes of chloroform: methanol (2:1, v/v), followed by the addition of 20 mL sodium chloride solution to facilitate cell wall disruption and lipid release. The mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes, and the lower organic phase containing the total lipids was transferred to a pre-weighed 50 mL round-bottom flask. Following solvent evaporation, the lipid content was determined gravimetrically by re-weighing the flasks. The resulting lipid extract was subjected to GC-MS profiling to verify the presence of EPA, and EPA-enriched fraction was then used for the feeding trials (Figures 2A, B).

Figure 2. The total FAME profiling (A) chromatogram and the (B) Lipid composition containing SFAs, MUFAs and PUFAs of N.oceanica derived algal oil.

2.4 Sampling and preservation of samples

Upon conclusion of the 21-day feeding trial, all tanks were dewatered and the number of larvae in each tank was manually counted and weighed (Mettler Toledo, Mumbai) after fasting for 24 hours at the last feeding to compute indices of growth performance including weight gain, survival rate, and feed conversion ratio (FCR) (Figure 1B). Samples collected for whole body proximate analysis, for assaying digestive enzymes and non-specific immune responses were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then preserved at ─20 °C until further analysis.

2.5 Survival and growth indices

2.6 Sample preparation for digestive enzyme assay

Snap -frozen samples from each replicate were hygienically macerated in liquid nitrogen before being homogenized with ice-cold 0.9% physiological saline using a tissue homogenizer (IKA, Bengaluru, India). The whole-body lysate was centrifuged at 4 °C for 20 minutes at 15,000 rpm and thereafter kept at –20 °C until the enzyme activities were assessed. The total soluble protein in the enzyme extracts was measured using the Bradford technique (1976), with bovine serum albumin as the reference.

2.7 Estimation of digestive enzymes

The gut enzymatic activity of rohu at the end of the experiment were assessed for amylase (Rick and Stegbauer, 1974), protease (Silva et al., 2014), and lipase (German et al., 2004; Rajesh et al., 2022) and the enzyme activities were expressed as micromole of maltose released min-1 g protein-1 at 37 °C for amylase, as micromoles of tyrosine produced per mg of protein per minute at 37 °C for protease and µmole of para-nitrophenol produced min-1mg protein-1 for lipase.

2.7.1 Amylase

For estimation of amylase activity,170 µL of 0.1M Phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was dispensed into a 96 well deep well polypropylene plate, 20 µL of sample, 10 µL of substrate (starch) was added and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 25 °C and then 200 µL of DNS was added and it was again incubated at 100 °C for 45 min. 1mL of distilled water was added to the mixture to cool it down and 200 µL of the reaction mixture was dispensed into the microplate and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm in the microplate reader.

2.7.2 Protease

Protease activity was assayed using a modified microplate based method with Azocasein as substrate. The assay mixture consisted of 20 µL of sample and 50 µL of 1% Azocasein in 0.1M Tris HCl which was incubated for 1hr at 25 °C and then 140 µL of TCA was added and centrifuged at 8000g for 5 min. The supernatant was used for end point estimation, where 70 µL of supernatant and 130 µL was dispensed onto the microplate and absorbance was measured at 450 nm in microplate reader.

2.7.3 Lipase

Lipase activity was assayed using a modified microplate-based method with 5mM p-nitrophenyl palmitate (PNP) was utilized as the substrate which was prepared, following the protocol of Rajesh et al. (2022). Assay mixture consisted of 40 µL of sample and 210 µL of substrate and change in absorbance was measured at 410 nm for 10 min at 60 second intervals. The lipase unit was calculated using the molar extinction coefficient (ϵ= 15.95/mM*cm) for p-nitrophenol produced.

2.8 Estimation of non‐specific immune parameters

Whole-body homogenates for immunological analysis were prepared from larvae following a 21-day nursery rearing period, according to the method of Hanif et al. (2004). Briefly, larvae were randomly sampled from each replicate, euthanized, weighed, and thoroughly rinsed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2). Tissues were then homogenized in ice-cold PBS at a 1:1 (w/v) ratio. The homogenate was centrifuged at 4,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was collected and stored at -20 °C until subsequent analysis. The homogenates were analyzed for key innate immune parameters: myeloperoxidase activity (MPO), hemolytic activity, lysozyme activity, and bacterial agglutination titer. Myeloperoxidase activity was quantified according to Quade and Roth (1997). Lysozyme activity was determined following the method of Ellis (1990). Bacterial agglutination assays were performed in U-bottom microtiter plates as described by Swain et al. (2019). Hemagglutination and hemolytic activities were quantified based on the protocols of Blazer and Wolke (1984).

2.9 Analysis of proximate composition

Standard procedures were employed to analyze the proximate compositions of experimental feeds (AOAC, 2012). Dry matter was determined by oven-drying at 1050C up to constant weight. The crude protein contents were estimated by the Kjeldahl method using 6.25 conversion factor (KEL PLUS, Pelican Equipments, Chennai, India). The crude lipid contents were determined by Soxhlet method (SOC PLUS, Pelican Equipments) and acid/alkali digestion were performed to measure the crude fiber contents of the samples (FIBRA PLUS, Pelican Equipments, Chennai, India). To determine the ash content, the samples were incinerated at 600 0C for 12 hours in the muffle furnace. The proximate composition of experimental feeds with different sources of oil is presented in Table 2.

2.10 Fatty acid analysis

The fatty acid composition of whole-body rohu and different oil sources was determined via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) according to established protocols (Siddaiah et al., 2023; Chandan et al., 2023; Christie, 1993). Briefly, total lipids were extracted using a chloroform/methanol (2:1 v/v) solution per the Folch method (Folch et al., 1957) and concentrated by rotary evaporation at 50 °C. The extracted lipids were then transesterified into fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) using methanolic NaOH and BF3. The resulting FAME extracts, dissolved in n-heptane, were stored at -20 °C prior to analysis. GC-MS analysis was conducted on a Shimadzu GC-2010 system featuring a DB225 capillary column and a flame ionization detector, with hydrogen as the carrier gas. The temperature gradient was: initial 35 °C for 30 s, ramped to 195 °C at 25 °C/min, then to 205 °C at 3 °C/min, and finally to 240 °C at 8 °C/min, held for 35 min. Peaks were identified by comparison to a 37-component FAME standard (Supelco, CRM47885).

2.11 Statistical analysis

All experimental data were subjected to statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism software (version 4.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) followed by Tukey’ post-hoc tests. Results are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). p‐values of <0.05 were considered significant.

3 Results

3.1 Growth performance of nursery rohu fed diets with different sources of oil

The growth performance of nursery rohu fed diets containing different oil sources is summarized in Table 3. Following the 21-days feeding trial, fish fed the fish oil (FO) diet exhibited a significantly higher (p < 0.05) growth rate compared to those fed algae oil (AO), linseed oil (LO), or sunflower oil (SFO) diets. No significant differences (p > 0.05) in growth were observed among the AO, LO, and SFO treatment groups. FCR was calculated from the total feed intake and weight gain. The FO group also demonstrated the most favorable FCR, which was significantly superior to all other treatments. Furthermore, the FCR for the AO diet was significantly better than that of the LO and SFO diets.

Survival of nursery rohu was monitored throughout the trial. Final survival rate was significantly highest (p < 0.05) in the AO treatment group compared to all other diets. No significant differences (p > 0.05) in survival were observed among FO, LO, and SFO groups. These results demonstrate a clear differential effect of oil source, with algal oil promoting the highest survivability and fish oil supporting the superior growth rate.

3.2 Effects of different dietary oil sources on non-specific immunity parameters in nursery rohu

The nonspecific immunity parameters of nursery rohu fed diets containing distinct oil sources are presented in Table 4. Upon conclusion of the 21-day feeding trial, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were detected among treatment groups for key innate immune responses, including lysozyme, hemolytic, hemagglutination, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activities.

Table 4. Nonspecific immunity parameters of nursery rohu fed with different sources of oil during the experiment.

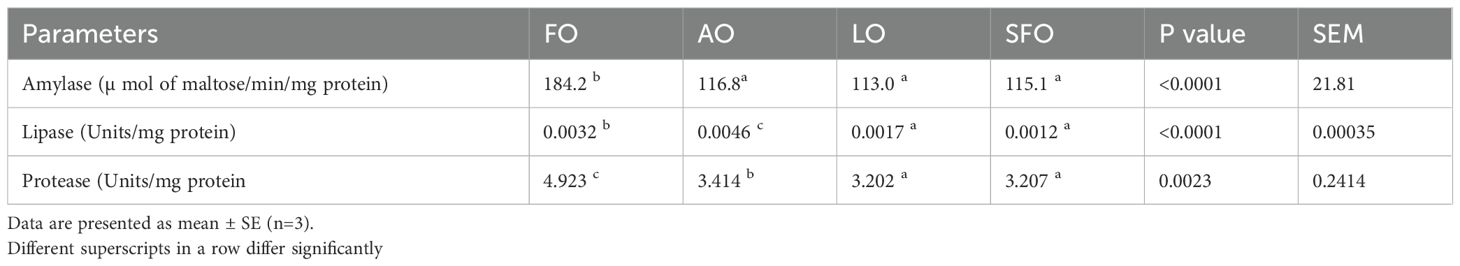

3.3 Gut enzyme activity of nursery rohu fed diets with different sources of oil

The activity of key digestive enzymes (amylase, protease, lipase) in nursery rohu fed diets containing distinct oil sources is summarized in Table 5. Statistical analysis revealed significant differential effects of dietary oil sources on enzymatic activities. Amylase and protease activities were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the FO group compared to all other treatments. Conversely, lipase activity was significantly highest (p < 0.05) in the algae oil (AO) group, differing markedly from the FO, LO, and SFO treatments. No significant differences (p > 0.05) in amylase, protease, or lipase activities were observed between the SFO and LO dietary groups. Furthermore, protease activity in the AO group was significantly greater than in both the LO and SFO groups.

3.4 Whole-body fatty acid composition (% of total fatty acids) of rohu fed diets with different sources of oil

Dietary oil source significantly influenced the whole-body fatty acid profile of nursery-reared rohu (Figure 3). The deposition of n-3 PUFAs was highest in the fish fed the FO diet, which was significantly greater (p < 0.05) than all other groups. The AO group also retained significantly more n-3 PUFAs than the SFO group, which had the lowest concentration. In contrast, n-6 PUFA content was numerically higher in fish fed the LO and SFO diets compared to the FO and AO groups; this difference was significant between the FO and SFO groups but not between the LO and SFO groups. Overall, total PUFA concentration was significantly highest in the FO fed group.

Figure 3. The effect of dietary oil source on the whole-body fatty acid composition (% of total fatty acids) in rohu. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n=3).

4 Discussion

The economic sustainability of sectors reliant on fishmeal (FM) and fish oil (FO) is challenged by a supply-demand imbalance. While demand is escalating due to aquaculture growth and industrial applications, production from conventional fisheries is both finite and ecologically unsustainable. Consequently, identifying and developing alternative sources has become an urgent priority for the industry (FAO, 2022). Fish oil is a critical ingredient in aquafeed formulations, providing a concentrated source of metabolic energy and essential functional nutrients, notably long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LC-PUFAs). These fatty acids are indispensable for the proper development of the nervous system, the modulation of immune function, and the ontogeny of vital organs in both aquatic species and humans (Tocher et al., 2015). Although various alternative oils including crude palm oil, soybean oil, canola oil, cottonseed oil, corn oil, pork lard, and poultry fat have been investigated as potential substitutes for fish oil in aquafeeds, their inherently low concentrations of n-3 LC-PUFAs, specifically eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), often result in suboptimal growth performance and compromised health status in farmed aquatic species (Alhazzaa et al., 2019). The most effective application of microalgal lipids is as a premium LC-PUFA supplement for the partial replacement of fish oil, rather than as a bulk energy substitute. Microalgae, particularly species within the genera Chlorella, Tetraselmis, Isochrysis, Microchloropsis, and Nannochloropsis biosynthesize significant quantities of nutritionally critical compounds, including essential fatty acids and carotenoid pigments. Research indicates that the integration of algal biomass or extracts from these species serves as an effective strategy for the nutritional enhancement and fortification of aquaculture feed formulations (Seong et al., 2021; Walker and Berlinsky, 2011). Through de novo synthesis, microalgae produce n-3 LC-PUFAs that satisfy the essential fatty acid demands of farmed aquatic animals. The fatty acid profile of microalgae is highly species-specific. Certain species accumulate substantial quantity of n-LC-PUFAs, which can comprise between 37% and 67% of their total fatty acid content. Microalgae are a well-established, sustainable source of n-3 LC-PUFAs for aquaculture, with the commercial production of microalgal-derived DHA already demonstrating significant success. Linseed (flaxseed) oil is distinguished by its high concentration of unsaturated fatty acids, notably alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), an essential n-3 fatty acid. In contrast, sunflower oil is predominantly composed of oleic and linoleic acids, which constitute 85–90% of its total fatty acid profile. In aquaculture, fish oil and soybean oil are commonly used lipid sources, while linseed and algal oils are less frequently utilized. Identifying the most effective and cost-efficient oil source is crucial for optimizing sustainable aquaculture production.

The nursery phase is a critical bottleneck in carp seed production, with only 25–30% of hatchlings surviving to the fry stage, and 40–50% of fry developing into fingerlings under standard farming conditions. Enhanced survival and growth during the nursery phase are fundamental requirements in modern aquaculture practices (Das et al., 2024). The survival rate was significantly higher in groups fed a diet supplemented with microalgae (N. oceanica) oil compared to those fed other oil based diets. While fish oil promoted optimal growth and FCR, algal oil represents a more sustainable and economically viable alternative. Its competitive FCR and higher survivability compared to plant-based oils (linseed and sunflower) can increase profitability for aquaculture operations. Therefore, algal oil presents a sustainable alternative to fish oil for nursery rearing in aquaculture.

Assessing gastrointestinal function, particularly digestive enzyme activity, provides a reliable metric for determining the nutritional health of farmed fish and for screening potential novel ingredients in aquafeed formulations (Alarcón, 1998). Gut enzyme activity was consistent with the observed growth performance in this experiment. The activity of digestive enzymes is a key indicator of digestive efficiency, as they catalyze the hydrolysis of nutrients and their increased activity directly reflects improved nutrient assimilation. The enhanced growth performance associated with fish oil is likely attributable to a concurrent increase in gut amylase and protease activity. The higher amylase and protease activity in the FO group correlates with its superior growth, suggesting better utilization of dietary protein and carbohydrates for enhanced growth performance.

The increased survivability in rohu fed algal oil may be linked to enhanced lipase activity, which improved the hydrolysis and subsequent bioavailability of essential fatty acids (EFAs). This improved EFA profile likely supported critical physiological functions, thereby reducing mortality during the nursery phase (Tocher et al., 2015). Another plausible reason for the superior survival in the algal oil group, despite iso-lipidic diets, may be attributable to co-extracted bioactive compounds like carotenoids and tocopherols that enhance antioxidant status and mucosal immunity, thereby boosting larval robustness.

The absence of adverse effects and high tolerability of Nannochloropsis oil establishes it as a viable and sustainable replacement in aquafeeds. The dietary administration of microalgal products appears to modulate lipid digestion by enhancing endogenous lipase secretion. This is evidenced by a dose-responsive upregulation of lipolytic enzyme activity in juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) fed graded levels of N. oceanica meal (Qiao et al., 2019). Corroborating this, Adel et al. (2016) found that a 10% dietary inclusion of Spirulina platensis significantly increased lipase activity in the digestive tract of juvenile beluga sturgeon (Huso huso).

Dietary supplementation with algal oil significantly enhanced digestive function and growth performance in larval Japanese seabass (Lateolabrax japonicus). Rahman et al. (2021) demonstrated that an algal oil-based diet elicited a significant upregulation in the activity of key pancreatic digestive enzymes, specifically trypsin and lipase, compared to diets containing fish oil or soybean oil. This augmented enzymatic capacity was concomitant with superior growth metrics, including significantly increased final body weight and specific growth rate. The authors attributed these synergistic effects to the superior nutritional profile of algal oil. Its high concentration of bioavailable docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) promoted enhanced lipid digestibility and acted as a critical dietary stimulant for the functional maturation of the entero-pancreatic system. Conversely, studies on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) indicate that the partial or complete substitution of fish oil (FO) with microalgae oil elicits no significant changes in enzyme activities in the hindgut region (Katerina et al., 2020; Zatti et al., 2023). This disparity suggests that the physiological effects of microalgae-based supplements are highly species-specific.

The whole-body fatty acid composition of nursery rohu was significantly influenced by the dietary lipid source. The highest n-3 PUFA deposition was recorded in the fish oil group, which was significantly greater (p < 0.05) than all other treatments. The algal oil group exhibited a significantly higher n-3 PUFA content than sunflower oil groups, which had the lowest recorded values. These results are consistent with the observed gut enzyme profiles. The elevated lipase activity in fish fed algal oil likely enhanced the hydrolysis and absorption of dietary lipids, thereby increasing the bioavailability of precursor fatty acids for the subsequent synthesis and deposition of n-3 LC-PUFA. Consistent with the present findings, Liu et al. (2022) also reported a significant elevation in tissue n-3 LC-PUFA content, specifically EPA and DHA, in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) fed a diet supplemented with N. oceanica. Betancor et al. (2021) indicated that a novel, terrestrial-based oil from a transgenic Camelina sativa line, bioengineered to synthesize elevated levels of EPA and DHA, serves as a viable alternative to fish oil in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) feeds. The study reported comparable growth and feed efficiency, alongside enhanced deposition of n-3 LC-PUFA in fish tissues. Evidence from multiple studies supports the use of Schizochytrium sp. products as a viable, renewable alternative for dietary n-3 LC-PUFA supplementation in aquaculture. The efficacy of both its dried biomass and extracted oil has been validated in key species such as Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) (Sprague et al., 2016), white shrimp (Patnaik et al., 2006), and gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) (Ganuza et al., 2008).

In our study the nonspecific immunity parameters like lysozyme, hemolytic, hemaglutination and myeloperoxidase activity did not show any significant difference (p > 0.05) when fed with different sources of oil. Other workers while feeding microalgae have highlighted the immunostimulating abilities in fish and crustaceans. The primary benefits of the algal oil at this life stage appear to be mediated through improved digestive efficiency leading to higher survival, rather than the upregulation of the specific humoral immune parameters assayed in the study. The immunostimulatory efficacy of Euglena viridis was evidenced in L. rohita challenged with A. hydrophila. According to Das et al. (2009), dietary administration of E. viridis significantly potentiated key humoral and cellular immune defenses. This was characterized by a marked increase in lysozyme activity, bolstered serum bactericidal activity, and a heightened respiratory burst, as indicated by elevated superoxide anion production. Studies on gibel carp (Carassius auratus gibelio) have established that Chlorella supplementation acts as a potent biostimulant, significantly enhancing growth performance and physiological status while concurrently modulating immunity. This includes the regulation of both innate and adaptive immune mechanisms (Xu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). This could be due to availability of other essential nutrients in algal biomass which are deprived in oil experiment.

Microalgae have been used as the initial live prey for the rearing of the small larvae of most marine finfish species and some freshwater fish species (especially filter-feeding fish) for a long time. To achieve the appropriate EFA content, rotifers are often enriched with microalgae, for example, Chlorella, Nannochloropsis, Tetraselmis, and I. galbana (Dinesh et al., 2025). The use of microalgae as the food source for rotifers can be in the form of live microalgae, dried microalgal powder, or microalgal concentrate. Live microalgae can maintain a stable rotifer culture for an extended period due to their positive effect on water quality (Dhont et al., 2013). Generally, marine fish and crustaceans require a higher proportion of fish oil (5%–20%) than freshwater fish species (under 5%) (Tacon and Metian, 2008). Fish oil are predominantly derived from captured aquatic animals and the by-products of fish processing factories. However, the limited and decreasing global capture of aquatic animals has led to restricted global yields of fishmeal (ca. 5 million t per year) and fish oil (ca. 1 million t per year), of which 60%–80% and 70%–80% is consumed in aquaculture, respectively (FAO, 2022). Given the growing demand for fish oil from the expanding aquaculture industry, identifying and use of appropriate substitutes for fish oil is imperative for sustainable aquaculture. This study confirms that oil derived from N. oceanica is a rich source of EPA and DHA, serving as a viable substitute for fish oil in nursery diets for rohu. Its use can help alleviate the supply-demand deficit for n-3 LC-PUFA in aquaculture feed formulations.

5 Conclusion

Algal oil (Nannochloropsis oceanica) not only acts as a natural source of EPA within the marine food web but also flourishes under various cultivation conditions, facilitating substantial production of these beneficial fatty acids. By incorporating algal oil into fish feed, we can enhance the nutritional quality, growth performance and survivability of nursery fish while providing an economical solution to improve aquaculture practices. The decline in wild fish catches and growing demand from aquaculture make algal oil a vital, sustainable substitute for fish oil, helping to ensure better survival in the nursery phase.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of the ICAR-Central Institute of Freshwater Aquaculture, Bhubaneswar, India. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. KD: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. SN: Writing – review & editing. PS: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the DBT (Grant Number BT/PR40447/AAQ/3/998/2020, 2023). The work was supported by a grant from the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India, through the Taskforce on Aquaculture and Marine Biotechnology Project “BT/PR40447/AAQ/3/998/2020: Omega‐3 fatty acid enriched edible algal biomass as feed supplements” to MA and KCD.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Director, ICAR-CIFA, Bhubaneswar and Director, NIIST, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Trivandrum, for provision of facilities to carry out the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1696356/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdelghany M. F., El-Sawy H. B., Abd El-hameed S. A., Khames M. K., Abdel-Latif H. M., and Naiel M. A. (2020). Effects of dietary Nannochloropsis oculata on growth performance, serum biochemical parameters, immune responses, and resistance against Aeromonas veronii challenge in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 107, 277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.10.015

Adel M., Yeganeh S., Dadar M., Sakai M., and Dawood M. A. (2016). Effects of dietary Spirulina platensis on growth performance, humoral and mucosal immune responses and disease resistance in juvenile great sturgeon (Huso huso Linnaeus 1754). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 56, 436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.08.003

Alarcón F. J., Díaz M., Moyano F. J., and Abellón E. (1998). Characterization and functional properties of digestive proteases in two sparids; gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) and common dentex (Dentex dentex). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 19, 257–267. doi: 10.1023/a:1007717708491

Alhazzaa R., Nichols P. D., and Carter C. G. (2019). Sustainable alternatives to dietary fish oil in tropical fish aquaculture. Rev. Aquac 11, 1195–1218. doi: 10.1111/raq.12287

AOAC. (2012). Official methods of analysis of AOAC International 19th edn. Washington, DC, USA: AOAC International.

APHA. (2005). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater Missouri: American Public Works Association. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.51.6.940-a

Arumugam M., Udayan A., Sabapathy H., and Abraham B. (2021). Plant growth regulator triggered metabolomic profile leading to increased lipid accumulation in an edible marine microalga. J. Appl. Phycol 33, 1353–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10811-021-02424-0

Beal C. M., Gerber L. N., Thongrod S., Phromkunthong W., Kiron V., Granados J., et al. (2018). Marine microalgae commercial production improves sustainability of global fisheries and aquaculture. Sci. Rep. 8, 15064. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33504-w

Betancor M. B., MacEwan A., Sprague M., Gong X., Montero D., Han L., et al. (2021). Oil from transgenic Camelina sativa as a source of EPA and DHA in feed for European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.). Aquaculture 530, 735759. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735759

Blazer V. S. and Wolke R. E. (1984). The effects of α-tocopherol on the immune response and non-specific resistance factors of rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri Richardson). Aquaculture 37, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(84)90039-5

Chandan N. K., Sahu N. P., Krishna G., Kumar R., Nandi S., Kumari R., et al. (2023). Fatty acid utilization and digestive enzyme activity during early larval development of Anabas testudineus. Biol. Forum–Int. J. 15, 425–431.

Dallaire V., Lessard P., Vandenberg G., and de la Noüe J. (2007). Effect of algal incorporation on growth, survival and carcass composition of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fry. Bioresour. Technol. 98, 1433–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.05.043

Das S. K., Mandal A., and Khairnar S. O. (2022). “Aquaculture resources and practices in a changing environment,” in Sustainable Agriculture Systems and Technologies (John Wiley & Sons Ltd.) 169–199.

Das K. C., Mohanty S., Sinha M. K., Rath S. C., Sahoo P. R., Barik N. K., et al. (2024). Survival and non-specific immune parameters of nursery carp fed with CIFA-carp starter. Indian J. Anim. Res. 58, 453–458. doi: 10.18805/IJAR.B-4472

Das B. K., Pradhan J., and Sahu S. (2009). The effect of Euglena viridis on immune response of rohu, Labeo rohita (Ham.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 26, 871–876. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2009.03.016

Dhont J., Dierckens K., Støttrup J., Van Stappen G., Wille M., and Sorgeloos P. (2013). “Rotifers, Artemia and copepods as live feeds for fish larvae in aquaculture,” in Advances in Aquaculture Hatchery Technology (Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc).

Dinesh R., Nandhakumar S., Anand C., Kumar J., and Padmavathy P. (2025). Comparative analysis of Nannochloropsis oculata, Dunaliella salina, and Tetraselmis gracilis as feed sources for rotifer, Brachionus plicatilis: Effects on population dynamics, biochemical composition, and fatty acid profile. J. Appl. Phycol 37, 1029–1039. doi: 10.1007/s10811-024-03415-7

Ellis A. E. (1990). “Lysozyme assays,” in Techniques in Fish Immunol (SOS Publications) vol. 1, 101–103.

Fan Z., Gao Y., Xiong S., Li C., Wu D., Li J., et al. (2025). Assessment on Chlorella (Chlorella sorokiniana) meal as a substitution for fishmeal in Songpu mirror carp (Cyprinus carpio Songpu) feed: Effect on growth, intestinal health and microflora composition. Aquaculture 742, 742765. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.742765

FAO. (2024). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). doi: 10.4060/cd0683en

FAO. (2022). Aquaculture statistics: Global aquaculture production 1950-2020 (FishstatJ) (Rome: FAO Fisheries Division).

Folch J., Lees M., and Stanley G. S. (1957). A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64849-5

Ganuza E., Benítez-Santana T., Atalah E., Vega-Orellana O., Ganga R., and Izquierdo M. S. (2008). Crypthecodinium cohnii and Schizochytrium sp. as potential substitutes to fisheries-derived oils from seabream (Sparus aurata) microdiets. Aquaculture 277, 109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.02.005

Gbadamosi O. K. and Lupatsch I. (2018). Effects of dietary Nannochloropsis salina on the nutritional performance and fatty acid profile of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Algal Res. 33, 48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2018.04.030

German D. P., Horn M. H., and Gawlicka A. (2004). Digestive enzyme activities in herbivorous and carnivorous prickleback fishes (Teleostei: Stichaeidae): Ontogenetic, dietary, and phylogenetic effects. Physiol. Biochem. Zool 77, 789–804. doi: 10.1086/422228

Haas S., Bauer J. L., Adakli A., Meyer S., Lippemeier S., Schwarz K., et al. (2016). Marine microalgae Pavlova viridis and Nannochloropsis sp. as n-3 PUFA source in diets for juvenile European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.). J. Appl. Phycol 28, 1011–1021. doi: 10.1007/s10811-015-0622-5

Hanif A., Bakopoulos V., and Dimitriadis G. J. (2004). Maternal transfer of humoral specific and non-specific immune parameters to sea bream (Sparus aurata) larvae. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 17, 411–435. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2004.04.013

Ju Z. Y., Forster I. P., and Dominy W. G. (2009). Effects of supplementing two species of marine algae or their fractions to a formulated diet on growth, survival and composition of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquaculture 292, 237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.04.040

Kamyab H., Chelliapan S., Shahbazian-Yassar R., Din M. F. M., Khademi T., Kumar A., et al. (2017). Evaluation of lipid content in microalgae biomass using palm oil mill effluent (Pome). JOM 69, 1361–1367. doi: 10.1007/s11837-017-2428-1

Katerina K., Berge G. M., Turid M., Aleksei K., Grete B., Trine Y., et al. (2020). Microalgal Schizochytrium limacinum biomass improves growth and filet quality when used long-term as a replacement for fish oil, in modern salmon diets. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00057

Khumujam S. D., Dasgupta S., Srivastava P. P., Sahu N. P., and Varghese T. (2024). Interactive effects of dietary saponin with cholesterol and tannin on growth and biochemical responses in Labeo rohita (Hamilton 1822) fingerlings. Aquac. Int. 32, 4141–4157. doi: 10.1007/s10499-023-01368-1

Kumari R., Srivastava P. P., Mohanta K. N., Das P., Kumar R., Sahoo L., et al. (2024). Optimization of weaning age for striped murrel (Channa striata) based on expression and activity of proteases. Aquaculture 579, 740277. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.740277

Li M. H., Robinson E. H., Tucker C. S., Manning B. B., and Khoo L. (2009). Effects of dried algae Schizochytrium sp., a rich source of docosahexaenoic acid, on growth, fatty acid composition, and sensory quality of channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus. Aquaculture 292, 232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.04.033

Liu C., Palihawadana A. M., Nadanasabesan N., Vasanth G. K., Vatsos I. N., Dias J., et al. (2022). Utilization of Nannochloropsis oceanica in plant-based feeds by Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquaculture 561, 738651. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738651

Lovell T. (1998). “Dietary requirements,” in Nutrition and Feeding of Fish (Springer, Boston, US), 13–70.

Ma X. N., Chen T. P., Yang B., Liu J., and Chen F. (2016). Lipid production from nannochloropsis. Mar. Drugs 14, 61. doi: 10.3390/md14040061

Miller M. R., Quek S. Y., Staehler K., Nalder T., and Packer M. A. (2014). Changes in oil content, lipid class and fatty acid composition of the microalga Chaetoceros calcitrans over different phases of batch culture. Aquac. Res. 45, 1634–1647. doi: 10.1111/are.12107

Naylor R. L., Hardy R. W., Bureau D. P., Chiu A., Elliott M., Farrell A. P., et al. (2009). Feeding aquaculture in an era of finite resources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 15103–15110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905235106

Oswald A. T., Ishikawa M., Koshio S., Yokoyama S., Moss A. S., and Serge D. (2019). Nutritional evaluation of Nannochloropsis powder and lipid as alternative to fish oil for kuruma shrimp, Marsupenaeus japonicus. Aquaculture 504, 427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.02.028

Patnaik S., Samocha T. M., Davis D. A., Bullis R. A., and Browdy C. L. (2006). The use of HUFA-rich algal meals in diets for Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquac. Nutr. 12, 395–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2006.00440.x

Patterson D. and Gatlin III, D. M. (2013). Evaluation of whole and lipid-extracted algae meals in the diets of juvenile red drum (Sciaenops ocellatus). Aquaculture 416, 92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.08.033

Qiao H., Hu D., Ma J., Wang X., Wu H., and Wang J. (2019). Feeding effects of the microalga Nannochloropsis sp. on juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus L.). Algal Res. 41, 101540. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2019.101540

Qiao H., Wang H., Song Z., Ma J., Li B., Liu X., et al. (2014). Effects of dietary fish oil replacement by microalgae raw materials on growth performance, body composition and fatty acid profile of juvenile olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Aquac. Nutr. 20, 646–653. doi: 10.1111/anu.12127

Quade M. J. and Roth J. A. (1997). A rapid, direct assay to measure degranulation of bovine neutrophil primary granules. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 58, 239–248. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(97)00048-2

Rajesh M., Kamalam B. S., Sharma P., Verma V. C., Pandey A., Dubey M. K., et al. (2022). Evaluation of a novel methanotroph bacteria meal grown on natural gas as fish meal substitute in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Aquac. Res. 53, 2159–2174. doi: 10.1111/are.15735

Rahman Md A., Tantikitti C., Suanyuk N., Talee T., Hlongahlee B., Chantakam S., et al. (2021). “Effects of alternative lipid sources and levels for fish oil replacement in Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) diets on growth, digestive enzyme activity and immune parameters.” Songklanakarin Journal of Science & Technology 43, 4.

Raji A. A., Junaid Q. O., Oke M. A., Taufek N. H. M., Muin H., Bakar N. H. A., et al. (2019). Dietary Spirulina platensis and Chlorella vulgaris effects on survival and haemato-immunological responses of Clarias gariepinus juveniles to Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Aquac. Aquarium Conserv. Legis. 12, 1559–1577.

Rick W. and Stegbauer H. P. (1974). α-amylase. Methods enzymol Vol. 2 (New York: Academic Press), 885–894.

Rodolfi L., Chini Zittelli G., Bassi N., Padovani G., Biondi N., Bonini G., et al. (2009). Microalgae for oil: Strain selection, induction of lipid synthesis and outdoor mass cultivation in a low-cost photobioreactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng 102, 100–112. doi: 10.1002/bit.22033

Ryckebosch E., Bruneel C., Termote-Verhalle R., Goiris K., Muylaert K., and Foubert I. (2014). Nutritional evaluation of microalgae oils rich in omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids as an alternative for fish oil. Food Chem. 160, 393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.087

Seong T., Uno Y., Kitagima R., Kabeya N., Haga Y., and Satoh S. (2021). Microalgae as main ingredient for fish feed: Non-fish meal and non-fish oil diet development for red sea bream, Pagrus major, by blending of microalgae Nannochloropsis, Chlorella and Schizochytrium. Aquac. Res. 52, 6025–6036. doi: 10.1111/are.15463

Shah M. R., Lutzu G. A., Alam A., Sarker P., Kabir Chowdhury M. A., Parsaeimehr A., et al. (2018). Microalgae in aquafeeds for a sustainable aquaculture industry. J. Appl. Phycol 30, 197–213. doi: 10.1007/s10811-017-1234-z

Siddaiah G. M., Kumar R., Kumari R., Chandan N. K., Debbarma J., Damle D. K., et al. (2023). Dietary fishmeal replacement with Hermetia illucens (Black soldier fly, BSF) larvae meal affected production performance, whole body composition, antioxidant status, and health of snakehead (Channa striata) juveniles. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 297, 115597. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2023.115597

Silva J. F. X., Ribeiro K., Silva J. F., Cahú T. B., and Bezerra R. S. (2014). Utilization of tilapia processing waste for the production of fish protein hydrolysate. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 196, 96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2014.06.010

Sørensen M., Gong Y., Bjarnason F., Vasanth G. K., Dahle D., Huntley M., et al. (2017). Nannochloropsis oceania-derived defatted meal as an alternative to fishmeal in Atlantic salmon feeds. PloS One 12, e0179907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179907

Sprague M., Dick J. R., and Tocher D. R. (2016). Impact of sustainable feeds on omega-3 long-chain fatty acid levels in farmed Atlantic salmon. Sci. Rep. 6, 21892. doi: 10.1038/srep21892

Swain P., Das R., Das A., Padhi S. K., Das K. C., and Mishra S. S. (2019). Effects of dietary zinc oxide and selenium nanoparticles on growth performance, immune responses and enzyme activity in rohu, Labeo rohita (Hamilton). Aquaculture Nutrition 25, 486–494.

Tacon A. G. and Metian M. (2008). Global overview on the use of fish meal and fish oil in industrially compounded aquafeeds: Trends and future prospects. Aquaculture 285, 146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.08.015

Tibaldi E., Zittelli G. C., Parisi G., Bruno M., Giorgi G., Tulli F., et al. (2015). Growth performance and quality traits of European sea bass (D. labrax) fed diets including increasing levels of freeze-dried Isochrysis sp. (T-ISO) biomass as a source of protein and n-3 long chain PUFA in partial substitution of fish derivatives. Aquaculture 440, 60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.02.002

Tocher D. R., Betancor M. B., Sprague M., Sayanova O., Usher S., Campbell P. J., et al. (2015). Transgenic camelina sativa as a source of oils to replace marine fish oil in aquaculture feeds (Rotterdam, Netherlands: Aquaculture Europe).

Udayan A., Kathiresan S., and Arumugam M. (2018). Kinetin and Gibberellic acid (GA3) act synergistically to produce high value polyunsaturated fatty acids in Nannochloropsis oceanica CASA CC201. Algal Res. 32, 182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2018.03.007

Valente L. M. P., Custódio M., Batista S., Fernandes H., and Kiron V. (2019). Defatted microalgae (Nannochloropsis sp.) from biorefinery as a potential feed protein source to replace fishmeal in European sea bass diets. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 45, 1067–1081. doi: 10.1007/s10695-019-00621-w

Venkatesh T. and Muthu A.(2025).A perspective of microalga-derived omega-3 fatty acids: scale up and engineering challenges. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 65, 8173–8187doi: 10.1080/10408398.2025.2494060

Vizcaíno A. J., López G., Sáez M. I., Jiménez J. A., Barros A., Hidalgo L., et al. (2014). Effects of the microalga Scenedesmus almeriensis as fishmeal alternative in diets for gilthead sea bream, Sparus aurata, juveniles. Aquaculture 431, 34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.05.010

Walker A. B. and Berlinsky D. L. (2011). Effects of partial replacement of fish meal protein by microalgae on growth, feed intake, and body composition of Atlantic cod. N. Am. J. Aquac 73, 76–83. doi: 10.1080/15222055.2010.549030

Wang J., Chen G., Yu X., Zhou X., Zhang Y., Wu Y., et al. (2023). Transcriptome analyses reveal differentially expressed genes associated with development of the palatal organ in bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D 46, 101072. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2023.101072

Xiao F., Xing J., Li H., Xu X., Hu Z., and Ji H. (2021). Effects of the defatted Schizochytrium sp. on growth performance, fatty acid composition, histomorphology and antioxidant status of juvenile mirror carp (Cyprinus carpio var. specularis). Aquac. Res. 52, 3062–3076. doi: 10.1111/are.15150

Xie J., Fang H., Liao S., Guo T., Yin P., Liu Y., et al.(2019).Study on Schizochytrium Sp. Improving the Growth Performance and non-Specific Immunity of Golden Pompano (Trachinotus Ovatus) While Not Affecting the Antioxidant Capacity. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 95, 617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.10.028

Xu W., Gao Z., Qi Z., Qiu M., Peng J. Q., and Shao R. (2014). Effect of dietary Chlorella on the growth performance and physiological parameters of gibel carp, Carassius auratus gibelio. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 14, 53–57. doi: 10.4194/1303-2712-v14_1_07

Zahran E., Elbahnaswy S., Ahmed F., Ibrahim I., Khaled A. A., and Eldessouki E. A. (2023). Nutritional and immunological evaluation of Nannochloropsis oculata as a potential Nile tilapia-aquafeed supplement. BMC Vet. Res. 19, 65. doi: 10.1186/s12917-023-03618-z

Zatti K. M., Ceballos M. J., Vega V. V., and Denstadli V. (2023). Full replacement of fish oil with algae oil in farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar)–Debottlenecking omega 3. Aquaculture 574, 739653. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.739653

Zhang W., Zhang P., Sun H., Chen M., Lu S., and Li P. (2014). Effects of various organic carbon sources on the growth and biochemical composition of Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Bioresour. Technol. 173, 52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.09.084

Zhao W., Fang H. H., Gao B. Y., Dai C. M., Liu Z. Z., Zhang C. W., et al. (2020). Dietary Tribonema sp. supplementation increased growth performance, antioxidant capacity, immunity and improved hepatic health in golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus). Aquaculture 529, 735667. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735667

Keywords: Algae oil, rohu (Labeo rohita), nursery nutrition, survival rate, digestive enzymes, non-specific immunity, sustainable aquafeed

Citation: Mohanty A, Das KC, Kumari R, Chandan NK, Nandi S, Sahoo PK and Arumugam M (2025) Comparative evaluation of Nannochloropsis oceanica oil and conventional oils on survival, growth, and immunity in nursery rohu (Labeo rohita): towards sustainable aquaculture feeds. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1696356. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1696356

Received: 31 August 2025; Accepted: 10 November 2025; Revised: 05 November 2025;

Published: 15 December 2025.

Edited by:

Amit Ranjan, Tamil Nadu Fisheries University, IndiaReviewed by:

Sarvendra Kumar, College of Fisheries Kishanganj, IndiaPrakash Goraksha Patekar, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Central Agricultural University, India

Copyright © 2025 Mohanty, Das, Kumari, Chandan, Nandi, Sahoo and Arumugam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muthu Arumugam, YXJ1bXVnYW1Abmlpc3QucmVzLmlu; YWFzYWltdWdhbUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†ORCID: Muthu Arumugam, orcid.org/0000-0003-4697-6925

Aradhana Mohanty1

Aradhana Mohanty1 Krushna Chandra Das

Krushna Chandra Das Rakhi Kumari

Rakhi Kumari Muthu Arumugam

Muthu Arumugam