Abstract

The need for ocean information has never been greater. From climate change to food security and extreme events, we need to understand the role of the ocean and better predict change and impact. This is only possible with the sustained collection of a key set of ocean observations. The Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) coordinates international efforts to collect these Essential Ocean Variables (EOVs), which span physics, biogeochemistry, biology and ecosystem realms. Guided by three expert panels, these EOVs are used to define the needs and design of a sustained, fit for purpose global ocean observing system, aimed at maximizing investments in observing infrastructure. As the GOOS EOVs are increasingly used, it has become important to discuss and refine the understanding of this framework, to ensure that the right balance is struck between their essential nature and the need to expand to new domains and integrate with key global policies. In this paper we provide a description of the EOV framework, discuss some of the challenges in implementing it, and identify a set of recommendations for GOOS and the ocean observing community to take forward. These recommendations include increasing the transparency of the EOV adoption process, and the need to periodically assess the EOVs in consultation with observing communities and with the entities managing other global essential variable frameworks in cross cutting realms such as climate and biodiversity. This will contribute to building a useful and responsive global ocean observing system that delivers the observations required to meet societal needs.

1 Introduction

The ocean is an essential component of Earth’s weather and climate system; it comprises the majority of Earth’s ecosystems and covers 70% of the surface of the planet. Human society depends critically on the ecosystem services and economic activities provided by the ocean including food resources, tourism, and shipping and for many coastal communities the ocean is highly important culturally. Safeguarding the sustainability of the ocean and these activities requires an understanding of the functioning of the ocean and how it might be changing over time. It also requires that appropriate information about the ocean be delivered to inform decision and policy-making, ensuring the continued health of the ocean and the provision of societal services.

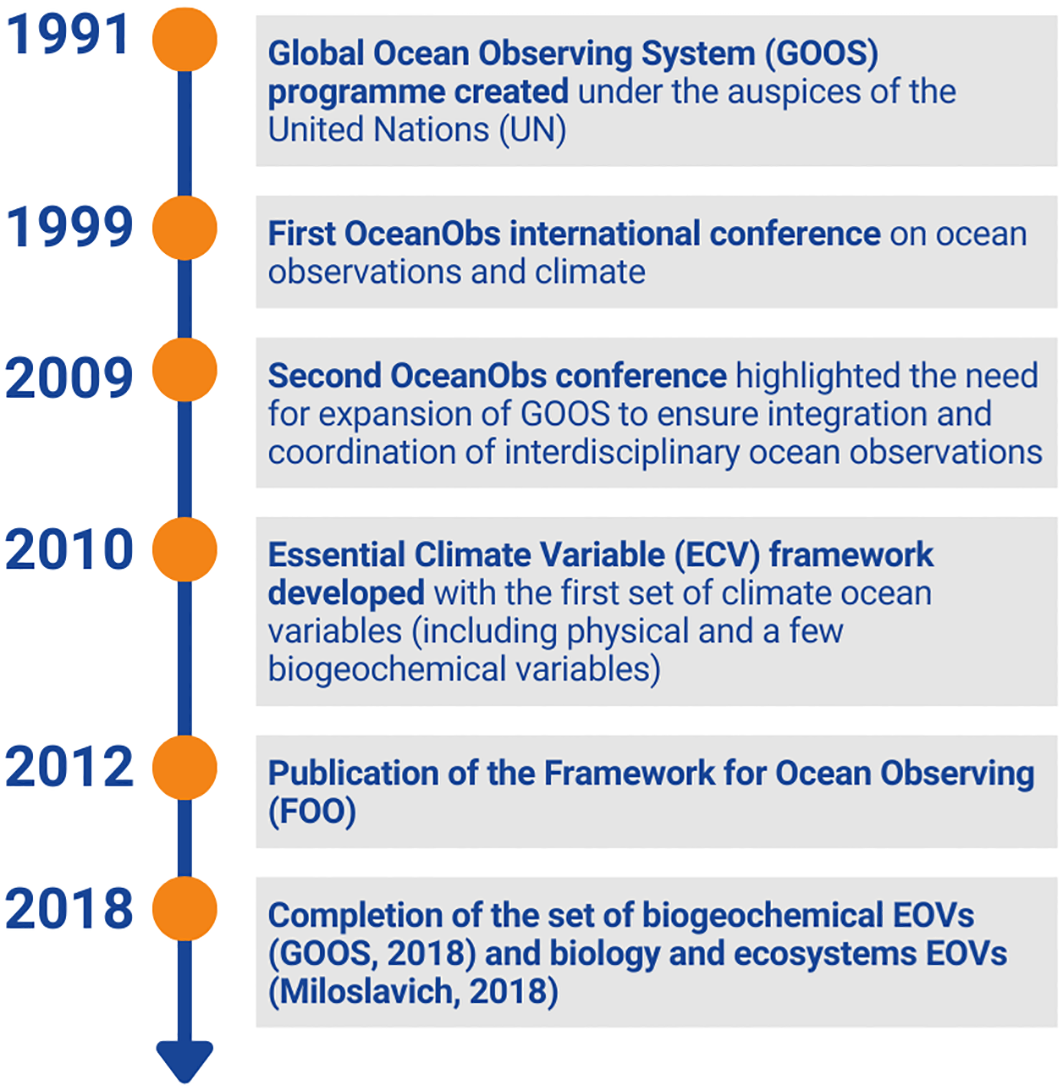

The Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) programme was created under the auspices of the United Nations (UN) in 1991 to establish the coordination framework needed to bring the ocean observations that support delivery of this vital information. The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO (IOC/UNESCO) is the lead sponsor of GOOS, with co-sponsors the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the International Science Council (ISC).

The initial focus of GOOS was on collecting observations in support of understanding and forecasting weather, hazard warnings, and climate change. Since then, the need for ocean data and information has expanded significantly, encompassing operational and management aspects of ocean and coastal activities, including industries such as fisheries, aquaculture, offshore wind farms, seabed mining, tourism, and navigation. Increased provision of ocean and marine biodiversity information is also required for environmental impact and risk assessments, and sustainable ocean planning, thereby underpinning the implementation of ocean management and policies. The vision of GOOS has evolved in response to these needs and is expressed as ‘a truly global ocean observing system that delivers the essential information needed for our sustainable development, safety, wellbeing and prosperity’ (Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), 2019).

The decadal OceanObs conferences have marked milestones in GOOS’s evolution process. In particular, the 2009 OceanObs’09 conference in Venice, Italy, highlighted the need for expansion of GOOS to ensure integration and coordination of interdisciplinary ocean observations (including biological and ecological observations) and commissioned a Task Team to develop the Framework for Ocean Observing (FOO, see Table 1 for a full list of acronyms) (UNESCO, 2012; Tanhua et al., 2019a). The FOO applies a system-design approach to guide ocean observing communities in establishing requirements for an integrated, fit-for-purpose, sustained global ocean observing system, focused on a limited number of variables: the Essential Ocean Variables (EOVs). This focus on EOVs aimed to move ocean observations beyond a focus on single observing systems, platforms, programs, or regions towards a system that was globally connected and coordinated. In doing so, the FOO recognized the lessons learned in identifying and building a set of Essential Climate Variables (ECVs) (Bojinski et al., 2014), which aimed to bring the global community together to coordinate and cooperate in building a climate observing system facilitated by the Global Climate Observation System (GCOS).

Table 1

| Acronyms and abbreviaotins | Definition |

|---|---|

| GOOS | Global Ocean Observing System |

| FOO | Framework for Ocean Observing |

| EOV | Essential Ocean Variable |

| OOPC | Ocean Observations Physics and Climate panel |

| BGC | Biogeochemistry panel |

| BioEco | Biology and Ecosystems panel |

| GCOS | Global Climate Observing System |

| ECV | Essential Climate Variable |

| GEO BON | Group on Earth Observations Biodiversity Observation Network |

| EBV | Essential Biodiversity Variable |

List of acronyms and abbreviations repeatedly used in the paper.

Since their creation in the early 2010’s, the GOOS EOVs have become a reference for the ocean observing community globally, supporting harmonization and collaboration. They are also increasingly recognized by other organizations that use ocean data, such as the WMO, and funding agencies when planning and supporting ocean observing activities (see Section 2.5).

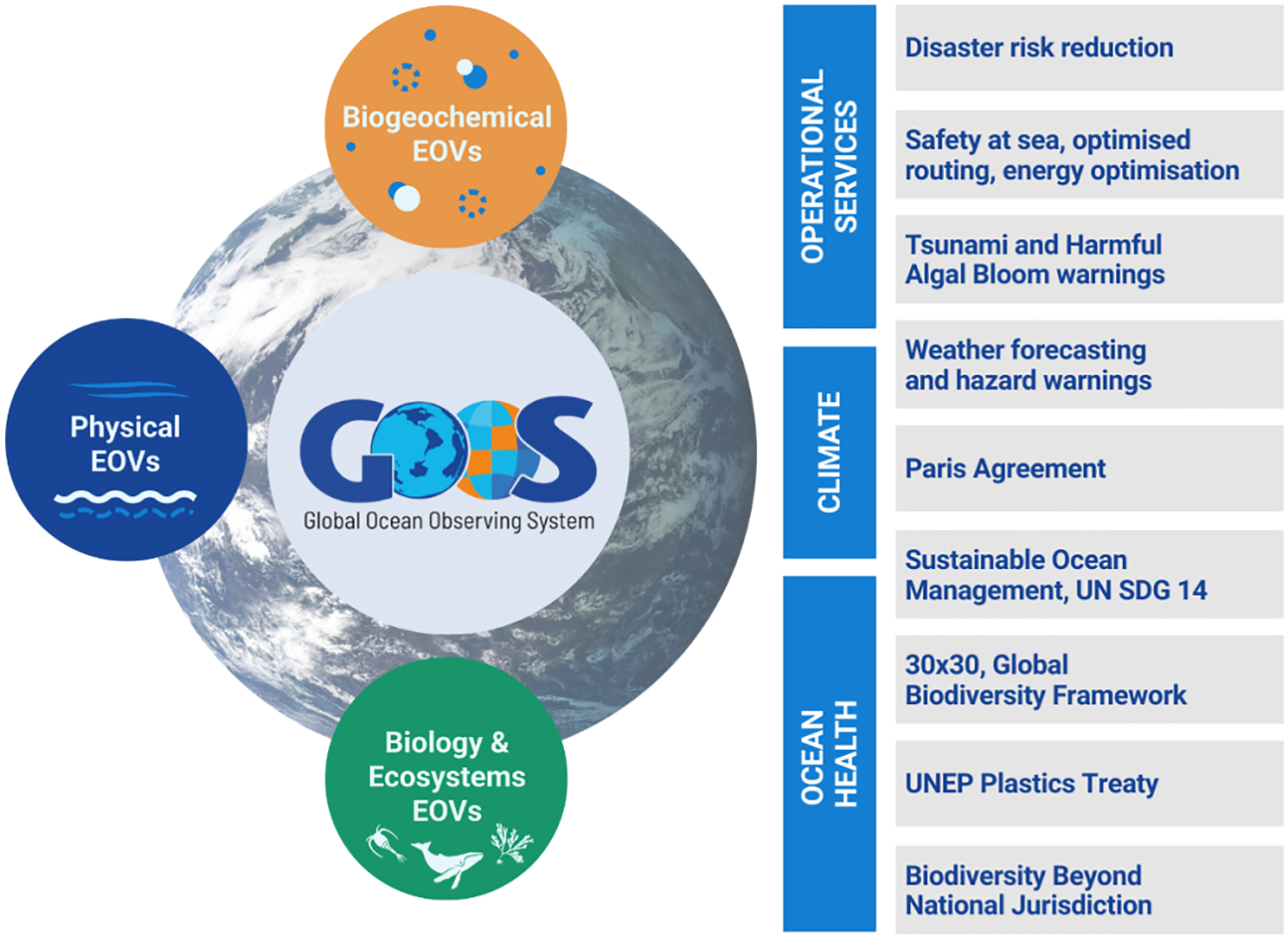

Through the EOVs GOOS can help guide investments in observing infrastructure and support the coordination of ocean observing systems that provide information important to its three main delivery areas: climate, weather forecasts and warnings, and ocean health. Developing EOVs that have a clear connection to community and policy requirements, ensures that the observing system can deliver directly to societal and environmental needs.

The EOV concept has been in use for almost 15 years (UNESCO, 2012), and its function now requires review. This paper lays out the concept, its implementation and current status (Section 2), expands on key issues related to the development of the framework (Section 3), and finally discusses a way forward to ensure the EOV framework remains effective for the next decade (Section 4).

2 The EOV framework and its use

By “EOV framework” we refer to a set features developed by GOOS in implementing the concept, encompassing the definition and EOV description, the current group of EOVs, the process to establish their “essentiality”, and their stewardship.

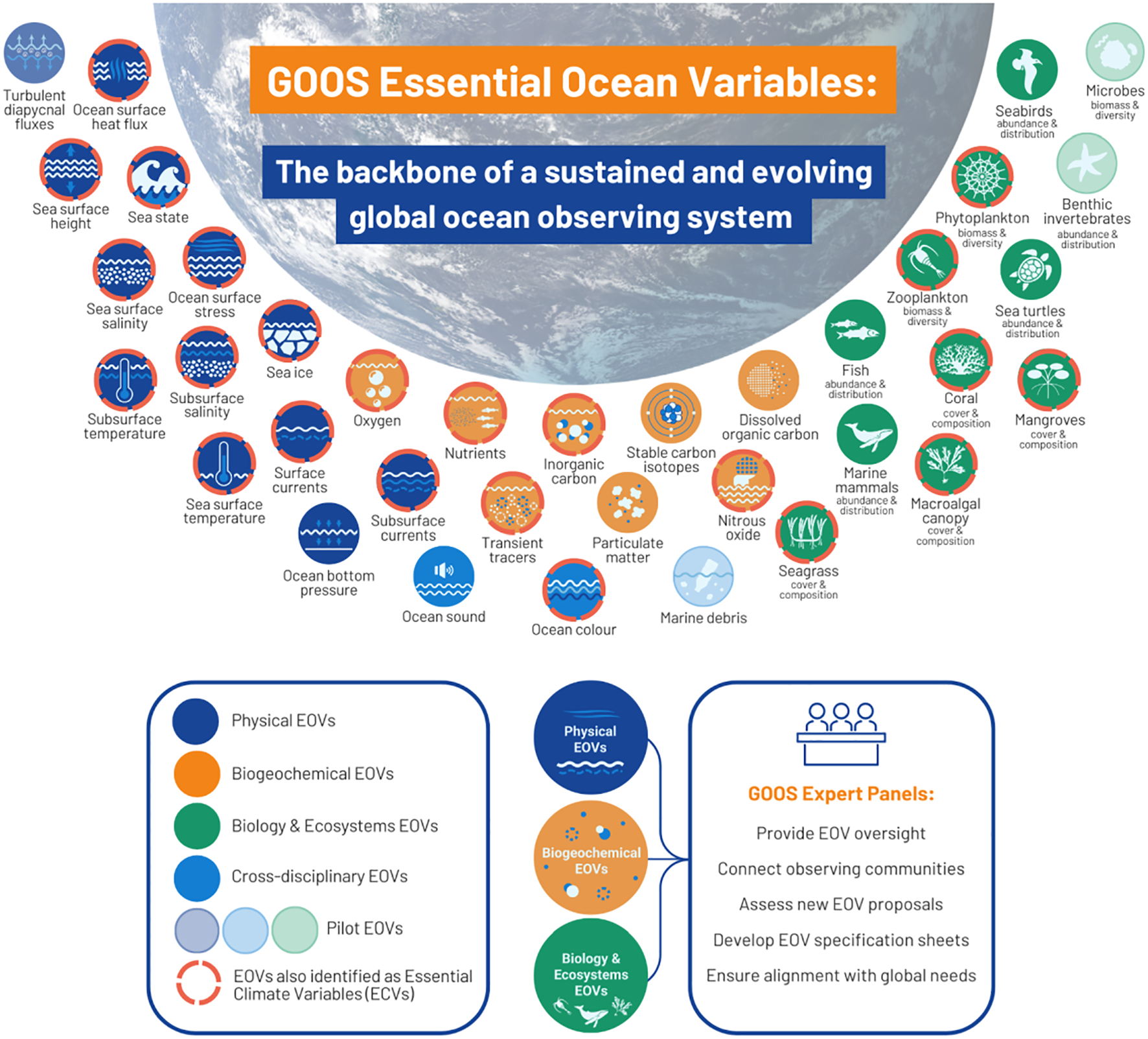

There are three GOOS expert panels, which provide scientific advice and expertise to GOOS and are instrumental to carry forward GOOS activities: The Physics and Climate panel (OOPC), the Biogeochemistry panel (BGC) and the Biology and Ecosystems panel (BioEco). As described in the FOO, the GOOS expert panels are responsible for setting requirements for EOVs, documenting and sharing of best practices, as well as assessing fitness for purpose of the observing system, and associated data and information streams.

2.1 Brief history

The OOPC (Sloyan et al., 2019) was the first GOOS panel to develop a set of physical EOVs in the early 2010s (Figure 1). The physical EOVs initially comprised the ocean variables already included in the Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) Essential Climate Variables (ECV) framework. The BGC panel also adopted some of the relevant ECVs from GCOS and then expanded the biogeochemical EOVs through an expert consultation process (Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), 2013) that identified additional candidate biogeochemical EOVs and defined the state of readiness of observing system elements and existing data streams for the EOVs. The BioEco panel undertook a process for identifying a set of EOVs based on the Drivers, Pressures, State, Impact and Response (DPSIR) framework, combined with a feasibility and impact assessment. These reflect the biological and ecological observations required to “inform ocean health and provide baselines against which the effects of human pressures and climate change may be measured and reported” (Miloslavich et al., 2018).

Figure 1

Timeline and milestones in the development of the EOV framework since the creation of GOOS.

Additionally, EOVs aimed at delivering outputs of relevance to human pressures with direct relevance for policy and sustainable ocean management have been identified and are in various phases of development. These are the Ocean Colour, Ocean Sound and Marine Debris EOVs (Figure 2). Each of these EOVs has cross-disciplinary elements, with two or all GOOS expert panels providing oversight.

Figure 2

The current set of 36 GOOS EOVs (2025) categorized following the three disciplines of the GOOS expert panels: physics (13 EOVs), biogeochemistry (8 EOVs), and biology and ecosystems (12 EOVs). There are also three cross-disciplinary EOVs delivering outputs of relevance to human pressures on the ocean. Pilot EOVs (see Section 2.4) are represented in lighter colors. EOVs that are also ECVs are circled with a dashed red line. The figure also illustrates the role of the GOOS expert panels in the EOV framework.

2.2 EOV definition and the nature of ‘essential’

GOOS currently recognizes 36 Essential Ocean Variables (2026) across physical, biogeochemical, biology and ecosystem, and some human impact domains (Figure 2). GOOS EOVs are derived from sustained individual measurements or combinations of measurements that are essential for assessing the ocean’s state and changes in globally important ocean phenomena [Box 1]. They can be used in applications that provide societal benefits. These ocean phenomena1 can be properties (such as habitat status and trends), processes (such as air-sea fluxes), or events (such as upwelling) that have distinct spatial and temporal scales and when observed, inform assessments of ocean state and ocean change (Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), 2016, Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), 2018). Multiple EOVs may be required to assess state and variability of one global phenomenon, and one EOV can be used to assess multiple phenomena.

Box 1

Definition of GOOS Essential Ocean Variables (GOOS EOVs).

GOOS EOVs are defined as the minimum set of ocean variables that are needed to assess ocean state and variability for important global ocean phenomena, and to provide essential data for applications that support societal benefit. They are derived from sustained individual measurements, or combinations of measurements, that can be undertaken at global scale and in a cost-effective manner.

The “essential” nature of an EOV is evaluated by the relevant GOOS expert panel based on impact and feasibility for sustained observation.

The assessment of a variable’s impact considers how the variable addresses the three GOOS delivery areas (detailed in Box 2) both from a scientific perspective (i.e., addressing critical knowledge gaps) and from a service perspective (i.e., addressing critical user needs). The feasibility for sustained observation considers whether the measurement is technically and economically realistic to collect or estimate, on a global scale, using proven, scientifically understood, and ethical methods. Feasibility also considers the effectiveness of data delivery into systems supporting ocean information products and services.

Box 2

Three main delivery areas for GOOS.

Climate

The ocean is a key component of the climate system and influences its evolution and change through the energy, water, and carbon cycles. Expanded and improved ocean observations, the knowledge generated from those observations and the resulting improvements in climate services inform policies and decisions supporting mitigation of and adaptation to climate change.

Forecasts and warnings (Operational Services)

Coastal populations and infrastructure are growing and are increasingly exposed to ocean-related hazards, and marine industries and users continue to grow - ocean and weather forecasts and early warning systems manage risk and improve business efficiency.

Ocean observations are also vital to forecast extreme events at all scales.

Ocean Health

Ocean ecosystems are under increasing pressure from anthropogenic activities, both through direct impacts (e.g., pollution including marine debris and noise) and through greenhouse gases absorption, which is warming, acidifying, and reducing oxygen concentrations in the ocean. Expanded and enhanced observations are needed to understand how changes in the ocean are occurring, how these changes affect the services it provides to society, and to generate the knowledge required to sustain ocean biodiversity, as well as the resources and livelihoods it supports.

This combination of impact and feasibility sets a clear justification to consider what is ‘essential’ and supports investment rationale and priorities for sustained ocean observations. In this way, the EOVs help provide pragmatic guidance for the ocean observing system design, recognizing that “we cannot measure everything everywhere, nor do we need to” (UNESCO, 2012). Furthermore, EOVs are easy to communicate, and used to drive attention to parts of the ocean observing system that require support. The EOVs distil the complexity of tracking ocean state and variability, to a well-defined and limited set of essential ocean observations.

2.3 What is in a name? key elements of GOOS EOVs

Each EOV can be described by three key elements: the sub-variables, supporting variables, and derived products.

The sub-variables are key measurements that are used to estimate and characterize the EOV. For example, counts of individuals to provide an estimate of species abundance (such as fish, mammals, seabirds or turtles), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) to estimate ocean inorganic carbon, or wave height to characterize sea state.

The supporting variables are other measurements that provide scale or context to the sub-variables of the EOV or which can be useful in providing the derived products. For instance, pressure measurements can provide information on the depth at which subsurface currents are estimated, sea temperature affects the solubility of dissolved inorganic carbon, while water turbidity affects coral growth and can inform estimations of hard coral cover. Physical EOVs are typically used as supporting variables for many other non-physical EOVs.

The derived products are outputs calculated from the EOV and sub-variables, often in combination with the supporting variables, which contribute to evaluating changes in phenomena. For example, evaporation can be determined from sea surface temperature measurements; air-sea fluxes of CO2 can be derived from the inorganic carbon EOV; fish stock productivity can be determined from fish abundance.

Table 2 provides three examples of GOOS EOVs (one per discipline) together with the corresponding sub-variables, supporting variables, derived products, and the related phenomena they are used to evaluate.

Table 2

| EOV | Sea-surface temperature (SST) | Inorganic carbon | Seagrass cover and composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenomena | Air-Sea Fluxes Fronts and eddies Coastal Shelf Exchange Processes Upwelling |

Air-Sea Fluxes Storage/inventory Ocean Acidification Primary production Export fluxes |

Habitat status and trends Carbon stock and sequestration trends (estimated) Changes in species composition |

| Sub-Variables | Skin SST Subskin SST Near SST at stated depth Bulk SST |

Dissolved Inorganic Carbon (DIC) Total Alkalinity (TA) Partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) pH |

Seagrass percent cover Seagrass species composition Seagrass areal extent |

| Supporting Variables | Wind speed Cloud cover |

SST and subsurface temperature Surface and subsurface salinity Ocean vector stress Atmospheric column-averaged dry-air mole fraction of CO2 Barometric pressure Oxygen Transient tracers Oxygen to argon ratio |

Water depth, clarity, and temperature Salinity Sediment characteristics pH Dissolved oxygen concentration Nutrients concentrations Land runoff Fishing and Tourism pressure Surrounding habitats |

| Derived products | Foundation SST Bulk SST Latent, sensible, and long-wave air-sea heat flux Evaporation |

Saturation state (aragonite, calcite) Dissolved carbonate ion concentration Air-sea flux of CO2 Anthropogenic carbon |

Global and regional seagrass distribution Seagrass diversity metrics Ecosystem resilience Carbon storage and sequestration |

Three examples of GOOS EOVs overseen by the three GOOS expert panels (physics, biogeochemistry and biology and ecosystems), including the ocean phenomena they support, their corresponding sub-variables, supporting variables, and derived products.

2.4 EOV stewardship by GOOS expert panels

The panels are responsible for reviewing the EOVs, to make sure that they align with global information needs, such as for policy mandates for climate and biodiversity. For each EOV, GOOS expert panels produce a specification sheet, which serves as a guide for understanding and contributing relevant observations to support science and society. These specification sheets are developed in consultation with the ocean observing communities to ensure that they are an expression of community knowledge and reflect the most recent monitoring approaches and technology. They include details of phenomena, sub-variables, supporting variables and derived products, and provide guidance on the spatial and temporal scales at which the sub-variables need to be measured (i.e., the observational requirements) in order to detect and monitor the ocean phenomena, as well as data quality metrics. The specification sheets also include complementary information such as observing communities of practice and/or networks that measure the EOV, sensors and technologies and other observing approaches used for collecting the measurements, best practices and standards related to the measurement of variables and sub-variables, and information on the data flows, repositories, and products.

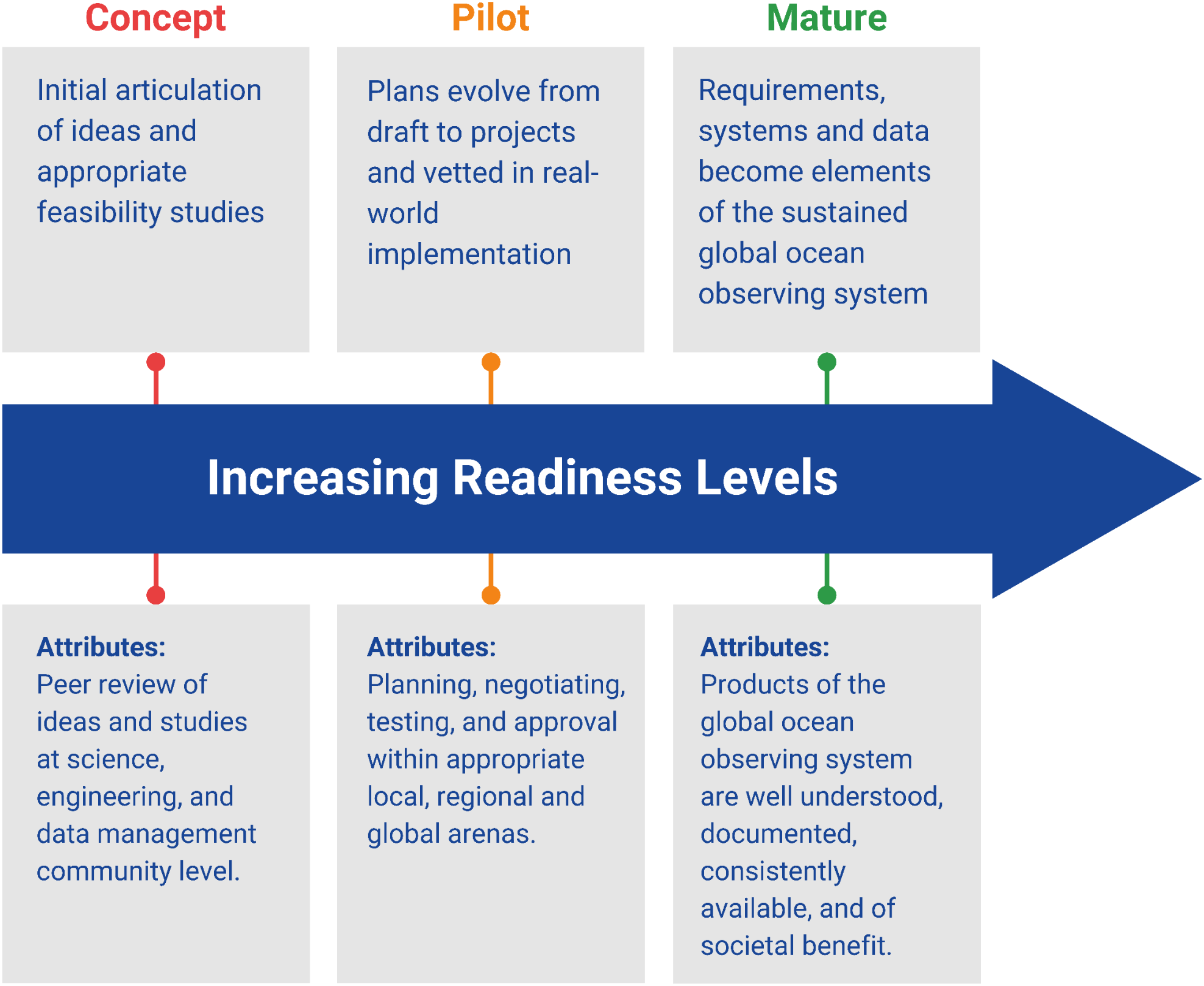

In the development and implementation of the sustained observing capacity to measure each new EOV three phases are recognized (Figure 3). During the first or concept phase, ideas are articulated and peer reviewed. During the second or pilot phase, elements of the system are tested and made ready for large-scale implementation. During the third or mature phase, those elements become a sustained part of the global ocean observing system. As part of their role as stewards of the EOVs, the GOOS expert panels assess the essential nature of the EOVs and oversee the evolution of an EOV from concept to mature. Through the EOVs, GOOS aims to reduce complexity and increase the readiness level of the observing system to meet the evolving demands of science and society.

Figure 3

The three phases in the development and implementation of the EOVs as part of the global ocean observing system (adapted from UNESCO, 2012).

2.5 Use of EOVs

The in situ global ocean observing networks coordinated under the GOOS Observations Coordination Group (OCG) are all required to observe EOVs as one of the key ‘attributes’ of a GOOS ocean observing network (Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), 2020), and the biological and ecological observing networks of GOOS are constructed around the 12 biological and ecological EOVs. GOOS global ocean observing networks currently (2026) recognized by the OCG include 13 mature networks: Argo, OceanGliders, OceanSITES (deepwater moored reference stations), Voluntary Observing Ships (VOS), XBT Ship of Opportunity Programme (XBT SOOP), Automated Shipboard Aerological Programme (ASAP), Global High Frequency Radar Network (HF Radars), Moored Buoys, Global Drifter Array (GDA), Tsunami Buoys, Global Ocean Ship-based Hydrographic Investigations Program (GO-SHIP), Animal Borne Ocean Sensors (AniBOS), the Global Sea Level Observing System (GLOSS), and four emerging networks: the undersea cables network (SMART Cables), the Fishing Vessel Ocean Observing Network (FVON), the Surface Ocean CO2 Observing Network (SOCONET), and the Surface Uncrewed Fleet (SUN Fleet). The networks develop best practices for executing measurements and estimating their quality (uncertainty, heterogeneity) to enable deriving EOVs, to ensure interoperability of observational data regardless of the platform used for observing, and to ensure that data is fed into delivery systems with appropriate quality and latency.

EOVs can also be monitored using airborne and spaceborne remote sensing systems (for a review see Amani et al., 2022). In particular satellite missions are an excellent complement to the in-situ data networks, since they can provide global coverage, yet restricted to the upper layers. Both in situ and remote sensing systems are typically used in combination, and the latter is dependent upon in situ measurements for calibration purposes. Huge progress has been accomplished in the last 30 years, starting with measurements of physical EOVs such as SST and sea ice, and more recently the ocean biosphere (Purkis and Chirayath, 2022). A GOOS Status Report is published every year2 with an update on the status of the global ocean observing system and its networks, including information on how both in situ and remote sensing components contribute to the monitoring of the EOVs. The Status Report also gives examples of how the collection of EOV data supports the development and implementation of policies and agreements connected to the three GOOS delivery areas. One single EOV can contribute to fulfil societal needs in several GOOS delivery areas (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Connection between EOVs, the three GOOS delivery areas, and relevant societal and policy needs and multilateral environmental agreements.

In parallel, numerous initiatives focusing on storage (new data repositories) and on EOV exploitation (new data products) have been set up and organized around the EOVs, both at national and international levels. For example, the European Copernicus programme builds upon the EOVs for its marine service component (CMEMS) and the CMEMS Ocean Monitoring Indicators3, provide trends and datasets covering 25 years of EOVs globally and per ocean basin. A recent review paper (Bloch Haimson et al., 2025) presents the EOV framework as one type of interoperability tool, crucial in supporting the vision of a distributed ocean data ecosystem.

The IOC Ocean Best Practices System (OBPS), a cross-IOC initiative initiated by GOOS and the International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange programme (IODE), has been established to provide a global coordination framework for development, and dissemination of Best Practices. The OBPS repository of global ocean best practices is searchable by EOV4.

At an intergovernmental level, five out of the seven Global Climate Indicators, used annually to produce the State of the Global Climate report (World Meteorological Organization (WMO), 2025) and supporting the policy-driven need to monitor warming relative to the goal specified in the Paris Agreement, are directly based on EOVs. The WMOs Unified Data Policy for International Earth System Data Exchange (World Meteorological Organization (WMO), 2022) acknowledges the importance of physical EOVs, which are identified as “Core Data” and must be exchanged, while the exchange of biogeochemical and biology and ecosystems EOVs that are also ECVs (Figure 2) is recommended.

The United Nations (UN) Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development Vision 2030 process has identified key action areas in which to make change by the end of the decade across all ten challenges. The Ocean Decade Vision 2030 White Paper – Challenge 7: Sustainably Expand the Global Ocean Observing System (Miloslavich et al., 2024) evaluated existing initiatives underway in the Ocean Decade and relevant communities, and identified priority datasets, gaps in science, and needs in capacity, infrastructure, and technology. The White Paper indicated the need for observing priorities and EOVs to evolve, informed by other Ocean Decade challenges. The White Paper – Challenge 2: Protect and Restore Ecosystems and Biodiversity highlights that success in establishing the scientific framework for sustainable development will rely on convergence on a practical set of essential ocean biology and ecosystem variables from among those defined by the GOOS (Muller-Karger et al., 2024).

The EOVs are increasingly recognized, utilized, and integrated into various aspects of ocean observing and ocean research (Centurioni et al., 2019; Bravo et al., 2021; Venkatesan et al., 2021; Lange et al., 2023) including by space agencies (Purkis and Chirayath, 2022). More and more funding agencies are referring to the EOVs and the need for projects to incorporate them into their activities recognizing EOVs’ value to enable evidence-based decision–making and contribute to the implementation of policy frameworks.

3 On-going challenges and opportunities for the EOV framework

In the previous section we have described the EOV framework and shown how EOVs are already well recognized across ocean observing and beyond. To ensure a proper uptake and development of the EOV framework moving forward, the ocean community has identified three key issues that need to be tackled.

-

Transparency: As already mentioned, the GOOS expert panels are responsible for identifying and setting requirements for EOVs. This identification process has not been formalized and, in some cases, has changed over time without being properly documented. A more transparent process will improve understanding of the EOVs and their evolution, as well as engagement by the broader community in the process.

-

Relationship with other essential variables frameworks: Other essential variable frameworks have been developed by organizations and groups, in parallel to the GOOS EOVs, and with varying complementarities, synergies and overlaps with the GOOS EOVs. These include the ECVs and the Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs) (Pereira et al., 2013). Identifying the interactions between essential variable frameworks is needed for creating linkages and synergies, as well as to avoid confusion and duplication of effort.

-

Proliferation: Multiple community white papers from the OceanObs’19 conference (Speich et al., 2019) showed that uptake of EOVs as a means to focus observing efforts had been embraced, with requests for many new “essential” ocean variables proposed to GOOS. It is important to find a balance between maintaining the ‘essential’ nature of EOVs, whilst also recognizing the evolution of observing systems, the technologies used, and the needs of the end-users, including policy makers.

Each challenge—and the opportunities tied to it—will be explored in the subsections below, while the following section (Section 4) will focus on how the EOV framework can adapt to these dynamics to remain relevant and fit for purpose. The interplay between the EOV framework and the private sector – and its potential to improve the observing system - will also be explained.

3.1 Adopting new EOVs and transparency of the framework

The EOVs recognized by GOOS are not intended to be static. Emerging or shifting societal needs, responses to climate change, expanding human pressures, advancements in science and technology, and other factors may result in a need or capacity to measure new variables. Technological advances and innovation can also advance observations and allow for the measuring of new variables, or the measuring of the variables with less uncertainty, altering the readiness level of the observing system (Figure 3).

To date, proposals to include a new variable in the EOV framework have been either put forward by members of a GOOS expert panel, or by a group of experts connected to a panel. In both cases, the experts were asked to justify their proposal based on the feasibility and impact of the EOV (Section 2.2). Preparing a proposal for an EOV has frequently involved mobilizing external groups of experts, and observing projects or programmes through consultations, workshops, or similar events to ensure input by global experts. The adequacy of the proposal was then assessed by the relevant GOOS expert panel and the decision made to adopt, or not, the proposed variable. For example, the proposal for an EOV focused on ocean bottom pressure was initially presented to OOPC in 2018 but did not meet the feasibility requirements for an EOV. Thanks to concerted efforts by the relevant experts in collaboration with the Deep Ocean Observing Strategy (DOOS5) community, the proposal was advanced, demonstrating the feasibility of the measurement, defining observational requirements, and presenting a plan to roll out a pilot under the umbrella of the SMART Cables initiative (Howe et al., 2019). The plan was considered by the GOOS Steering Committee, who accepted Ocean bottom pressure as a mature EOV in 2022, and SMART Cables as an emerging GOOS ocean observing network in 2024.

Currently, four pilot EOVs are being considered for inclusion in the list of mature GOOS EOVs (Figure 2). New monitoring technologies, such as molecular methods, and efforts leading to global coordination of observations, best practices, and data management developments, have progressed the feasibility of some of these EOVs (Microbes). With the growing recognition of the impacts of marine plastic debris to society, and parallel rapid development of globally scalable monitoring techniques, a cross-disciplinary Marine debris EOV is also developing. Similar technological, best practices and coordination of observation developments are happening for Diapycnal turbulent fluxes and Invertebrates EOVs.

Since 2016, GOOS has made a concerted effort to harmonize and streamline the identification of EOVs across the GOOS expert panels. Representatives from the three panels gathered in Ostend, Belgium (Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), 2016) in 2016 and produced a common set of definitions and descriptions for some of the elements pertaining to the EOV framework. Two years later, a cross-panel meeting was held in Hobart, Australia, where some of the EOV-associated concepts described in the Section 2.3 were further harmonized, including a common list of ocean phenomena to which the EOVs are linked (Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), 2018).

Despite reaching a collective understanding for the definition of EOVs and associated concepts, the process of identification, selection, and adoption of new EOVs has remained internal to GOOS. A documented process for the adoption of new EOVs is presented in Section 4.1, which addresses the transparency required for globally adopted frameworks.

3.2 Relation with other global frameworks associated with essential variables

The existence of connections between the GOOS EOVs and other Essential Variables (EVs) was recognized when they were first introduced in the FOO. Since then, the landscape of EV frameworks has changed and grown significantly with groups proposing essential variables of several types.

In recognition of the connectivity of Earth systems, the EOVs are aligned to work with both the Essential Climate Variables (ECVs), developed by the Global Climate Observing System (GCOS), and the Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs) developed by the Group on Earth Observations Biodiversity Observation Network (GEO BON); Pereira et al., 2013). Both these organizations have developed globally relevant ‘earth system’ essential variable frameworks, where the GOOS EOVs support the ocean component. ECVs support the development and implementation of policy responses, in particular under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Bojinski et al., 2014), while EBVs are connected to the implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

GOOS has been active in ensuring that the EOVs under its stewardship remain compatible with both global frameworks through time, and it is vital for planetary assessments that these essential variable frameworks are aligned.

3.2.1 EOVs alignment with ECVs

A set of Essential Climate Variables were developed by GCOS in the late 1990’s (Bojinski et al., 2014), with the first set of requirements for observing these variables published in 2010 (Global Climate Observing System (GCOS), 2010). These constituted the minimum set of observations required to systematically observe the Earth’s changing climate across three domains: the ocean, land, and atmosphere.

There are currently 55 ECVs specified by GCOS, of which 19 are ocean-focused variables. The Ocean Observations Physics and Climate (OOPC) panel acts as both the ocean panel for GCOS and the physics panel for GOOS providing a direct interface between GOOS and GCOS, and the primary stewardship for the ocean GCOS ECVs and the physical GOOS EOVs.

Of the 19 ocean ECVs, 11 are GOOS physics EOVs, and five are biogeochemistry EOVs (Figure 2). The ocean color ECV is a cross-disciplinary GOOS EOV. The two ocean biological ECVs are compounds of several GOOS Biological and Ecological EOVs, such that the mangrove, seagrass, macroalgae and hard coral EOVs, comprise the marine habitats ECV, and the phytoplankton and zooplankton EOVs make up the plankton ECV.

The ECVs and by association, the climate-related EOVs are updated through the GCOS review process every five years, with input from the GOOS expert panels. The most recent update was developed in 2019, opened to public review in 2020, and published in 2022, with a recent update in 2025 (Global Climate Observing System (GCOS), 2025).

3.2.2 EOVs alignment with EBVs

The EBVs defined by GEO BON apply to terrestrial, freshwater, and marine systems, and are complementary to the GOOS biological and ecosystem EOVs (Muller-Karger et al., 2018; Bax et al., 2019). EBVs synthesize and combine biodiversity observations across genes, species populations, communities, or ecosystems and have a primary focus on broader ecological phenomena such as taxonomic diversity or habitat structure.

Biological and ecological EOVs are measurements of the status and trends of marine biodiversity and cover key taxa representing the major groups of life among our diverse ocean environments. They can be seen as building blocks for the EBVs. For example, the EBVs can comprise time series of BioEco EOVs (e.g., changes in the abundance of a taxa or their distribution through time), and with each EOV contributing to multiple EBVs. EBVs can also comprise timeseries of gridded, mapped, or modelled BioEco EOVs (e.g., population/biomass dynamics which can be derived from EOV Fish abundance and distribution).

In 2016, the BioEco panel with the IOC-UNESCO programme OBIS (Ocean Biodiversity Information System), signed a collaborative agreement with the marine biodiversity component of GEO BON (the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network; MBON) to work collaboratively toward a set of mutual objectives. These objectives were focused on advancing the collection and sharing of information on biological and ecosystem components of the ocean, building a global community around shared approaches and leveraging the strengths and membership of each network (Benson et al., 2018). In practice, observing communities and networks monitor the same aspects of the marine environment, and are thus contributing to delivering both BioEco EOVs and EBVs.

3.2.3 EOVs alignment with indicators

Several of the community white papers presented at OceanObs19 explored the connections between EOVs and global indicators, particularly those pertaining to the environmental pillar of sustainability (Sustainable Development Goals SDG 13, 14 and 15). Tanhua et al. (2019a) describe how some EOVs could be directly established as ocean indicators, while Batten et al. (2019) point to information gaps in reporting on the SDGs and the CBD global indicators and the need to ‘streamline’ EOVs towards such indicators. Furthermore, policy requirements for indicators of ecosystem and biodiversity status are expanding, with the adoption of Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and associated target and indicator identification in 2022, and with the agreement on marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) under the UN Convention for Law of the Sea in 2023.

Regarding the connection between EOVs, and indicators of climate change specifically, five out of seven are already related to EOVs (surface temperature, sea level, ocean heat content, ocean acidification, Arctic, and Antarctic sea ice extent). Von Schuckmann et al. (2020) point out that the EOVs, the ECVs and the global climate indicators can be all considered “an evidence-based framework for Ocean and climate services providing a foundation for a sustainable ocean stewardship supporting international to national decisions to achieve the SDGs”.

Development of linkages between GOOS EOVs and global indicators established for multi-lateral environmental agreements is an area of opportunity to leverage community engagement in observing EOVs and provides a direct pathway for maximizing EOV impact. Yet, the connections between both conceptual frameworks need to be clearly established to avoid confusion and duplication of efforts.

3.3 Other collections of ocean variables and the risk of proliferation

Through the expert panels, GOOS is also working with a number of other variable frameworks to align efforts and recognize synergies between the EOVs and other variables being proposed. As previously noted, the OceanObs’19 conference showed that the EOV concept had been embraced, and several of the Community White Papers documented new sets of ‘EOVs’ not currently included in the GOOS EOV framework. In many cases, these sets of EOVs are specific to a particular region or part of the ocean (Southern Ocean, deep ocean…) which makes them contextually constrained.

Southern Ocean Observing System (SOOS) EOVs. SOOS collaborates with GOOS in the development of EOVs. Its science plan (Newman et al., 2022) identifies prioritization of efforts that support the collection of observations that contribute directly to the GOOS EOVs and GCOS ECVs, which as previously noted are linked. In addition, observations that support several variables specific to the Southern Ocean that are focused on particular species or specific processes at finer scales, but that align with the EOVs have been identified (Newman et al., 2022; Newman et al., 2019).

Essential Deep Ocean Variables. Although many of the GOOS EOVs consider subsurface ocean properties, initially few EOVs considered deep ocean observing needs (Levin et al., 2019). Direct collaborations with the Deep Ocean Observing System (DOOS), a GOOS project, has resulted in new EOVs being recognized, including ocean bottom pressure (adopted in 2022) and turbulent fluxes (Le Boyer et al., 2023); currently a pilot EOV). Further work is currently progressing towards expansion of some of the biology and ecosystem EOVs to include deep ocean species and communities and some of the biogeochemical EOVs to develop community practice and observation capacity into the deep ocean.

Coastal Essential Ocean Variables. Farcy et al. (2019) emphasized that a thorough understanding of the complexity of coastal processes requires a deep comprehension of the interactions between physics, biogeochemistry, and biology. To progress understanding of this coupling, the authors suggested an expanded set of coastal Essential Ocean Variables could be developed. Many of the variables proposed for a coastal observing network align with the GOOS EOVs either directly (e.g., variables proposed include temperature, salinity, turbidity, and fluorescence) or to a compilation of EOVs (e.g., a coastal EOV relating to the food web would draw on observations collected across multiple EOVs). However, in assessing the EOVs against the qualitative descriptors of the EU legislation MSFD (Marine Strategy Framework Directive), the same authors identified that further EOVs (at least benthic fauna, contaminant concentrations and induced biological effects and marine litter) would be required. Development of a GOOS cross-disciplinary EOV on marine litter and on invertebrates (Figure 2) goes some way to addressing these needs.

Other areas where EOVs have been suggested. A number of publications have identified a need for directed delivery of the observations contributing to EOVs into specific applications including fisheries assessments and ecosystem studies (Schmidt et al., 2019) and for understanding specific processes such as biological responses to ocean acidification (Tilbrook et al., 2019). In addition, in many regions, traditional and Indigenous knowledge can provide unique data to establish baselines and to understand historical change as it often incorporates observations over longer time periods and preserves memories of rare and extreme events (Kaiser et al., 2019). Frameworks that build on the EOVs to also recognize Indigenous and local community observations would provide information that is more responsive to local needs. For instance, the Shared Arctic Variables are built on observing efforts that are co-designed and co-managed with local communities. Their prioritization has been done as a function of societal benefit area, following analysis demonstrating that the sitting of observations and temporal resolution are less important to policy makers and funding organizations than delivering societal value through data that supports policy and decisions (Lee et al., 2019; Bradley et al., 2021).

The quantity and range of the OceanObs’19 papers proposing ocean variables is an indication of the acceptance and success of the EOV concept. However, they also illustrate a problem inherent in that success: if all variables are considered GOOS EOVs, we will lose the value and essential nature of the variables.

3.4 EOVs and the private sector

Another connection suggested in the OceanObs19 community white papers is between the EOVs and the private sector. Several papers point to the EOVs as having potential for prioritizing sensor and instrument development, with needs highlighted for autonomous platforms such as gliders or moorings as well as coastal monitoring for biogeochemical and biology and ecosystem variables (Wang et al., 2019; Testor et al., 2019; Benway et al., 2019). Furthermore, the advent of the private sector in the field of ocean observations could complement the existing observing infrastructure, which is mostly supported with public funds from a handful of nations and remains suboptimal. The EOV framework could help maximize investments by private companies, both through the prioritization of variables to monitor (pertaining to the EOVs), and through the EOV specification sheets (including information on observational requirements, best practices and data streams).

4 Discussion: evolving the GOOS EOV framework

In the previous sections we have documented the development of the GOOS EOV framework, and the challenges and opportunities associated with its implementation. Now we will present and discuss a set of suggestions for its evolution, addressing first the three issues highlighted in Section 3 and then considering other potential areas for progress to ensure that it remains a framework that is useful for the ocean community and beyond.

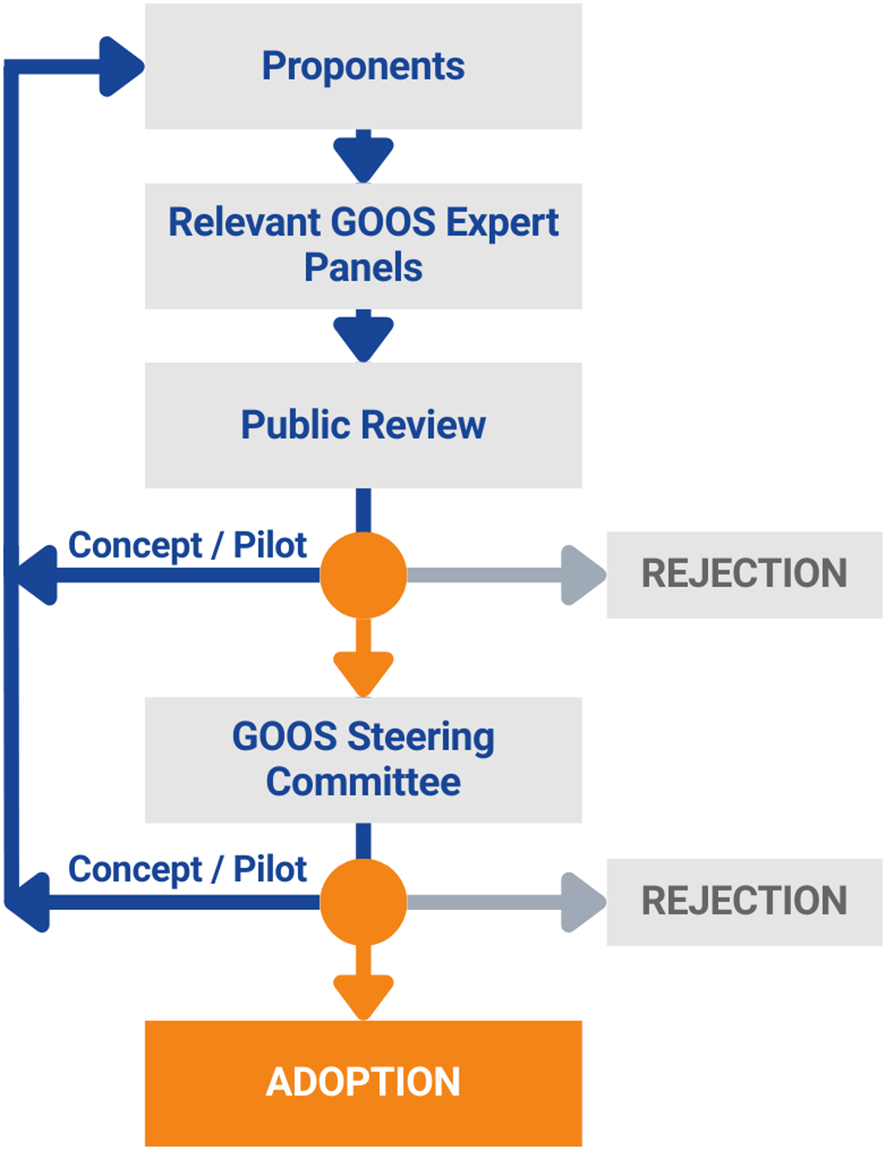

4.1 EOVs adoption process made transparent

As previously mentioned, ocean communities not closely related to GOOS have found it difficult to understand the process that led to the adoption of GOOS EOVs and have not engaged with it. To date, a formal GOOS EOV “adoption process” has been lacking. To tackle this issue and enhance transparency, understanding, and trust in the assessment process, the GOOS has now defined and adopted a documented process for submission of proposals and adoption of new GOOS EOVs, which the GOOS Steering Committee approved in 2024 (Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), 2024). This new process also ensures that the adoption of new EOVs is supported, documented, and can be tracked and reviewed, including through a Public Review. The adoption process can be adjusted and re-submitted for approval to GOOS SC as required. Supplementary Material 1 outlines the step-by-step process, from preparing the report to justifying a proposal for the final adoption of new EOVs by the GOOS Steering Committee and Figure 5 below summarizes the process.

Figure 5

Conceptual diagram of the process to adopt new GOOS EOVs.

To ensure that the EOV framework maintains its focus on addressing the most relevant societal needs, and adjusts and adapts as these needs evolve, a systematic assessment mechanism is required. This implies updating the specification sheets including the observational requirements for all the EOVs on a regular basis. While it is out of the scope of this paper to design such an assessment, one recommendation could be to establish a cyclic review process synchronized with other well-established processes such as that undertaken by GCOS (every five years, see Section 3.2.1), to avoid duplication of effort. To ensure relevance to the broader observing community and maintain consistency across disciplines, this review should actively engage experts from outside GOOS and include collaborative meetings among the three GOOS expert panels. Elements for such an assessment could include a review of the EOVs sub-variables and mapping the connections between them across GOOS expert panels as well as revisiting the “essentiality” of the EOVs and the EOVs sub-variables. In certain cases, for instance, if the impact of one EOV is considered to be less than initially understood, or if technical advancements make it possible to observe phenomena measuring new variables, an EOV could be withdrawn from the list.

4.2 Streamlining EOVs and other global frameworks associated with essential variables

Regarding the co-existence of several essential variable frameworks that overlap and intersect (e.g., the EOV, EBV and ECV frameworks), this can augment the visibility of these key variables which are fundamental for more than one application, but it can also bring about confusion and/or duplication of effort. A regular dialogue between the organizations responsible for these essential variable frameworks is suggested to ensure continuing alignment and to clarify the connections. OOPC, sitting between GOOS and GCOS, is an example of a body that maintains a regular dialogue around the EOVs and ECVs on behalf of all the GOOS panels. GOOS expert panels are now updating the EOV specification sheets using a new template which complies both with GOOS and GCOS needs and will continue to support the alignment between EOV and ECV practices. The BioEco Panel with OBIS will continue working with MBON to ensure that the EOV/EBV connection is well defined and clearly communicated. The goal is to take advantage of the same set of scientific measurements for different applications, in order to simplify the landscape for implementing ocean observation.

It is important that this ongoing work is regular and recognized by the framework sponsors and GOOS is working to ensure that the EOVs have a pathway into reporting mechanisms to ensure their relevance (see Figure 4). This applies particularly to the connection between the EOVs and the sets of indicators in the different realms (ocean, climate, biodiversity). The EOVs can be considered as the foundational measurements from which indicators are derived. While EOVs provide the core scientific data, indicators are more directly relevant to decision and policy making audiences. Typically, one indicator may derive from multiple EOV datasets, the setting of thresholds and/or combining with other datasets, hence global data systems providing a single entry-point to harmonized essential variable data are particularly valuable resources (Lehman et al., 2023). To this end GOOS is working towards the establishment of a federated data management system following EOV metadata standards and best practices and in line with FAIR principles (Tanhua et al., 2019b).

Focusing on the ocean realm, the importance of ocean indicators has been recently highlighted in the Ocean Decade Vision 2030 White Paper for Challenge 7 - Sustainably Expand the Global Ocean Observing System (Miloslavich et al., 2024) where the following measure of success is proposed: “established and prioritized a new set of ocean indicators, building on the EOVs, that are co-designed with stakeholders”. In 2021, GOOS set up a multidisciplinary task team to establish the foundation for an ocean indicator framework, which defined the criteria and a set of pilot indicators (Von Schuckmann et al., 2025).

4.3 Other collections of ocean variables and EOVs

Another key area of suggested evolution of the framework is consideration of the wide range of additional sets of variables that are proposed, as reflected in the OceanObs’19 Community White Papers, and discussed in Section 3.3. As of now (2025), a set of 36 GOOS EOVs exist and are managed by GOOS: these EOVs correspond to programmes of observation that are sustained, systematic and global. They cannot be replaced by other variables and without them, we lack fundamental information to understand oceanic and earth-system processes and to face societal problems.

Some regional or thematic ocean observing communities will continue to use the EOV concept to establish collections of ocean variables that adhere to the general principles of the EOVs but remain specific to those communities of practice. These collections can be managed by these communities outside GOOS; however, the variables will not be considered as GOOS EOVs, except where they are already designated as GOOS EOVs. Communities can nevertheless submit proposals for inclusion of new variables in the GOOS EOV list, provided they fulfil the requirements and follow the adoption process established by GOOS (Section 4.1 and Supplementary Material 1). These variables may be accepted as new EOVs, or they may be instead designated as sub-variables and incorporated as part of an overarching EOV. In other cases, the criteria may not be met to become a GOOS EOV.

4.4 EOVs and the private sector

The EOV framework can also foster development in the private sector. The GOOS-MTS Dialogues with Industry (Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), 2023) has made clear that the development of standards for observations, to provide delivery targets for sensors, networks, data streams, etc., would support investment, speed up technology development, and aid the growth of the observing system and efficiency in operations. This suggests that providing guidance on the standards required for the measurement of EOVs would support industry investment into sensor development, which would help to boost EOVs from pilot to mature. There is an analogy for this in the WMO Rolling Review of Requirements (RRR) process (World Meteorological Organization (WMO), 2023), where for an application and variable, an expression of the precision of the measurement required is requested and this information is available to national meteorology offices who might be procuring instruments or services. The suggestion is that GOOS, in consultation with the private sector, considers how setting such standards for EOVs could best be accomplished.

4.5 Uptake of new EOVs

Finally, while the usefulness of the EOV framework in fostering development of ocean observing technology and networks and in prioritizing ocean observations is clear, the practicalities and merits of the EOVs and their specification sheets to bridge the gap between the communities defining the requirements and those implementing them have not been sufficiently assessed. As previously mentioned, the EOV specification sheets are being reviewed and updated versions will be available in the months following the publication of this manuscript (2026). Efforts are already being undertaken, in particular through public review processes, to incorporate views from users of ocean data and ocean observing communities beyond GOOS panels in the development of these specification sheets.

We recommend GOOS holds a discussion on how the EOVs are currently applied to adjust, prioritize, and evolve the ocean observing system, and to propose a mechanism for optimizing this process. One possibility could be that, as a follow-up to the adoption process, a workshop could be held between the proponents of a new EOV and GOOS OCG and/or biological observing communities to plan the enhancement of observing capacity around the new EOV. Ongoing European initiatives, such as the ObsSea4Clim Project6, are also paving the way for using the EOV framework in designing observing systems tailored to specific applications, like marine heatwaves.

5 Conclusions

After a decade, the GOOS EOV framework has proven successful in carrying forward the GOOS mission to lead the ocean observing community and work with partners towards ensuring that the global ocean observing system delivers the essential information needed for our sustainable development, safety, wellbeing, and prosperity.

EOVs have helped implement the global ocean observing system through a user-driven design; they have helped focus investment and sustain observations; they have been used to evaluate the fitness for purpose of the system and identify gaps; standards and best practices, including system monitoring, data management and delivery of information, have been set around the EOVs. Furthermore, the EOVs are also a powerful communication tool, helping mobilize ocean observing communities, with an impact that spreads beyond GOOS.

The list of GOOS EOVs has expanded with time, first through inputs from the GOOS and GCOS community, and more recently after interaction with other groups of global experts connected with GOOS. The process for proposal and adoption of new EOVs into the GOOS EOV framework is now formalized and made transparent, with a clear definition of qualification criteria, and a delineation of responsibilities in assessing the proposals and approving the adoption (Supplementary Material 1).

GOOS commits to regularly assessing its list of EOVs, keeping abreast of developments from other communities within and outside the ocean realm, but making sure that the essential and global nature of the EOVs are not compromised.

Different local or national realities, capacities, and priorities may require sustained observations of additional variables beyond the GOOS EOVs, considered essential at a global level. GOOS encourages observing communities to apply the EOV framework principles, based on the feasibility, cost-effectiveness, and impact, for such additional sets of variables outside the GOOS umbrella.

GOOS will work to ensure that an active and iterative dialogue is established and maintained with other programmes in charge of related essential variable frameworks, and between all the actors involved in the EOV framework: the GOOS experts overseeing the EOVs and defining observing requirements, the ocean networks under OCG umbrella and beyond, the private sector developing ocean technology, as well as other communities using the EOV framework, in particular those supporting the development and implementation of operational ocean services and marine policies. This dialogue will ensure that the EOV framework continues to be responsive to scientific needs and societal challenges, helping strengthen and build observing communities and generate useful knowledge and applications.

Statements

Author contributions

BM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. EH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. NB: Writing – review & editing. LB-C: Writing – review & editing. GC: Writing – review & editing. KC: Writing – review & editing. KE: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. AF: Writing – review & editing. VG: Writing – review & editing. MH: Writing – review & editing. JK: Writing – review & editing. AL-L: Writing – review & editing. DL: Writing – review & editing. FM-K: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. BN: Writing – review & editing. LMN: Writing – review & editing. AP: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JP: Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing. LS: Writing – review & editing, Visualization. AS: Writing – review & editing. TT: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MT: Writing – review & editing. KS: Writing – review & editing. AW: Writing – review & editing. WY: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. BM acknowledges support from NOAA through an award A101685/37000825 to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. FM-K was supported by the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON) grant from NASA (grants NNX14AP62A; 80NSSC20K0017, 80NSSC22K1779), NOAA (IOOS grant NA19NOS0120199, CPO grant NA22OAR4310561), and the Gulf of Mexico Coastal Ocean Observing System (GCOOS/IOOS Cooperative Agreement NA16NOS0120018). NB was supported by funding from UNESCO to attend the GOOS BioEco panel meeting in Paris in September 2023. LMN and LB-C were supported by the European Union’s Horizon Europe programme under Grant Agreement No 101136748 (BioEcoOcean). KC was supported by NIWA SSIF funding. AW was supported by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF) through the Ocean Frontier Institute at Dalhousie University. KC, VG, AS and MT acknowledge support from the International Ocean Carbon Coordination Project through the United States National Science Foundation grant OCE-2513154 to the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR, United States). AS acknowledges support from PMEL (PMEL contribution 5633). AP was supported by the EU Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 869383 (ECOTIP) and the EU Horizon Europe programme under Grant Agreement No 101136748 (BioEcoOcean). JK, TT and SS acknowledge support from EU H2020 project EuroSea under Grant Agreement No 862626 and EU Horizon 2030 project ObsSea4Clim Grant Agreement No 101136548. DL was supported by NOAA's Global Observing and Monitoring Program. The authors thank Uppsala University, Sweden, for covering the open access costs for this publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the very useful comments from two reviewers which helped improve the clarity, structure and presentation.

Conflict of interest

Author SS was employed by SMRU Consulting.

The remaining authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors TT, SS declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the review phase, B. Martín Míguez used Le Chat Mistral AI to edit approximately 1% of the paper to improve readability.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2026.1737002/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary material 1Description of the step-by-step process to follow for adoption of new Essential Ocean Variables (EOVs) by the Global Ocean Observing System Steering Committee.

Supplementary Material 2Graphical abstract of the Essential Ocean Variables Framework

Footnotes

1.^ https://goosocean.org/document/37429

2.^ https://www.ocean-ops.org/goosreport/

3.^ https://marine.copernicus.eu/access-data/ocean-monitoring-indicators

4.^ https://www.oceanbestpractices.org/

References

1

Amani M. Moghimi A. Mirmazloumi S. M. Ranjgar B. Ghorbanian A. Ojaghi S. et al . (2022). Ocean remote sensing techniques and applications: A review (Part I). Water14, 3400. doi: 10.3390/w14213400

2

Batten S. D. Abu-Alhaija R. Chiba S. Edwards M. Graham G. Jyothibabu R. et al . (2019). A global plankton diversity monitoring program. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00321

3

Bax N. J. Miloslavich P. Muller-Karger F. E. Allain V. Appeltans W. Batten S. D. et al . (2019). A response to scientific and societal needs for marine biological observations. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00395

4

Benson A. Brooks C. M. Canonico G. Duffy E. Muller-Karger F. Sosik H. M. et al . (2018). Integrated observations and informatics improve understanding of changing marine ecosystems. Front. Mar. Sci.5. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00428

5

Benway H. M. Lorenzoni L. White A. E. Fiedler B. Levine N. M. Nicholson D. P. et al . (2019). Ocean time series observations of changing marine ecosystems: an era of integration, synthesis, and societal applications. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00393

6

Bloch Haimson M. Lehahn Y. Sagi T. (2025). An overview of the ocean data ecosystem. Ocean Sci.21, 3131–3164. doi: 10.5194/os-21-3131-2025

7

Bojinski S. Verstraete M. Peterson T. C. Richter C. Simmons A. Zemp M. (2014). The concept of essential climate variables in support of climate research, applications, and policy. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc.95, 1431–1443. doi: 10.1175/bams-d-13-00047.1

8

Bradley A. Eicken H. Lee O. Gebruk A. Pirazzini R. (2021). Shared arctic variable framework links local to global observing system priorities and requirements. Arctic74, 69–86. doi: 10.14430/arctic7642

9

Bravo G. Moity N. Londoño-Cruz E. Muller-Karger F. Bigatti G. Klein E. et al . (2021). Robots versus humans: automated annotation accurately quantifies essential ocean variables of rocky intertidal functional groups and habitat state. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.691313

10

Centurioni L. R. Turton J. Lumpkin R. Braasch L. Brassington G. Chao Y et al (2019). Global in situ Observations of Essential Climate and Ocean Variables at the Air–Sea Interface. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00419

11

Farcy P. Durand D. Charria G. Painting S. J. Tamminen T. Collingridge K. et al . (2019). Toward a european coastal observing network to provide better answers to science and to societal challenges; the JERICO research infrastructure. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00529

12

Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) (2010). Implementation plan for the global observing system for climate in support of the UNFCCC, (2010 update) (GCOS-138/COP-16) (Geneva: World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Available online at: https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/58703.

13

Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) (2025). The 2022 GCOS ECVs requirements (GCOS-245) (2025 update) (Geneva: World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Available online at: https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/58111.

14

Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) (2013). Defining Essential Ocean Variables for Biogeochemistry: First technical experts workshop of the GOOS Biogeochemistry Panel (GOOS-206) (Paris: IOC-UNESCO). Available online at: https://goosocean.org/document/13585.

15

Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) (2016). GOOS cross-panel report (GOOS-219) (Paris: IOC-UNESCO).

16

Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) (2018). A report of the Meeting of the Global Ocean Observing System Expert Panels (GOOS Cross-Panel 2018) (GOOS-228) (Paris: IOC-UNESCO). Available online at: https://goosocean.org/document/21277.

17

Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) (2019). “ The global ocean observing system 2030 strategy (GOOS-239),” in IOC brochure 2019-5 (IOC/bro/2019/rev.2) ( IOC-UNESCO, Paris).

18

Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) (2020). “ Observations coordination group,” in Network Attributes, Commitments, and Benefits - What it means to be an OCG Network (GOOS-266). Available online at: https://goosocean.org/document/24002.

19

Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) (2023). Dialogues with industry, synthesis report (GOOS-288). Available online at: https://goosocean.org/document/32773 (Accessed September 15, 2025).

20

Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) (2024). Process to adopt new GOOS Essential Ocean Variables (EOVs). Available online at: https://oceanexpert.org/document/35429 (Accessed September 15, 2025).

21

Howe B. M. Arbic B. K. Aucan J. Barnes C. R. Bayliff N. Becker N. et al . (2019). SMART cables for observing the global ocean: science and implementation. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00424

22

Kaiser B. A. Hoeberechts M. Maxwell K. H. Eerkes-Medrano L. Hilmi N. Safa A. et al . (2019). The importance of connected ocean monitoring knowledge systems and communities. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00309

23

Lange N. Tanhua T. Pfeil B. Bange H. W. Lauvset S. K. Grégoire M. et al . (2023). A status assessment of selected data synthesis products for ocean biogeochemistry. Front. Mar. Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1078908

24

Le Boyer A. Couto N. Alford M. H. Drake H. F. Bluteau C. E. Hughes K. G. et al . (2023). Turbulent diapycnal fluxes as a pilot Essential Ocean Variable. Front. Mar. Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1241023

25

Lee C. M. Starkweather S. Eicken H. Timmermans M.-L. Wilkinson J. Sandven S. et al . (2019). A framework for the development, design and implementation of a sustained arctic ocean observing system. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00451

26

Lehman A. Gregory G. Jarvis I. Serral Y. Masó J. Lacroix P. M. A. et al . (2023). GEO community activity report: Mainstreaming EVs across GEO. doi: 10.13097/archive-ouverte/unige:166309

27

Levin L. A. Bett B. J. Gates A. R. Heimbach P. Howe B. M. Janssen F. et al . (2019). Global observing needs in the deep ocean. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00241

28

Miloslavich P. Bax N. J. Simmons S. E. Klein E. Appeltans W. Aburto-Oropeza O. et al . (2018). Essential ocean variables for global sustained observations of biodiversity and ecosystem changes Glob. Change Biol.24, 2416–2433. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14108

29

Miloslavich P. O’Callaghan J. Heslop E. McConnell T. Heupel M. Satterthwaite E. et al . (2024). Ocean decade vision 2030 white papers – challenge 7: sustainably expand the global ocean observing system (Paris: UNESCO-IOC). doi: 10.25607/brxb-kr45

30

Muller-Karger F. E. Hwai A. T. S. Allcock L. Appeltans W. Baron Aguilar C. Blanco A. et al . (2024). “ Ocean decade vision 2030 white papers – challenge 2: protect and restore ecosystems and biodiversity,” in Ref. The ocean decade series (Paris: UNESCO-IOC). doi: 10.25607/y60m-4329

31

Muller-Karger F. E. Miloslavich P. Bax N. J. Simmons S. Costello M. J. Sousa Pinto I. et al . (2018). Advancing marine biological observations and data requirements of the complementary essential ocean variables (EOVs) and essential biodiversity variables (EBVs) frameworks. Front. Mar. Sci.5. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00211

32

Newman L. Hancock A. M. Hofmann E. Williams M. J. M. Henley S. F. Moreau S et al . (2022). The southern ocean observing system 2021–2025 science and implementation plan. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.6324359

33

Newman L. Heil P. Trebilco R. Katsumata K. Constable A. van Wijk E. et al . (2019). Delivering sustained, coordinated, and integrated observations of the southern ocean for global impact. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00433

34

Pereira H. M. Ferrier S. Walters M. Geller G. N. Jongman R. H. Schole R. J. et al . (2013). Essential biodiversity variables. Science339, 277–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1229931

35

Purkis S. Chirayath V. (2022). Remote sensing the ocean biosphere. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour47, 2022. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-112420-013219

36

Schmidt J. O. Bograd S. J. Arrizabalaga H. Azevedo J. L. Barbeaux S. J. Barth J. A. et al . (2019). Future ocean observations to connect climate, fisheries and marine ecosystems, (2019). Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00550

37

Sloyan B. M. Wilkin J. Hill K. L. Chidichimo M. P. Cronin M. F. Johannessen J. A. et al . (2019). Evolving the physical global ocean observing system for research and application services through international coordination. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00449

38

Speich S. Lee T. Muller-Karger F. Lorenzoni L. Pascual A. Jin D. et al . (2019). Editorial: Oceanobs’19: An ocean of opportunity. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00570

39

Tanhua T. McCurdy A. Fischer A. Appeltans W. Bax N. Currie K. et al . (2019a). What we have learned from the framework for Ocean Observing: Evolution of the global ocean observing system. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00471

40

Tanhua T. Pouliquen S. Hausman J. O’Brien K. Bricher P. de Bruin T. et al . (2019b). Ocean FAIR data services. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00440

41

Testor P. DeYoung B. Rudnick D. L. Glenn S. Hayes D. Craig M. L. et al . (2019). OceanGliders: a component of the integrated GOOS. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00422

42

Tilbrook B. Jewett E. B. DeGrandpre M. D. Hernandez-Ayon J. M. Feely R. A. Gledhill D. K. et al . (2019). An enhanced ocean acidification observing network: from people to technology to data synthesis and information exchange. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00337

43

UNESCO (2012). “ A framework for ocean observing,” in By the task team for an integrated framework for sustained ocean observing UNESCO 2012 (Paris: IOC/INF). doi: 10.5270/OceanObs09-FOO

44

Venkatesan R. Muthiah M. A. Vedachalam N. Vengatesan G. Ramesh K. Kesavakumar B. et al . (2021). Technological trends and significance of the essential ocean variables by the Indian moored observatories: relevance to UN decade of ocean sciences. Mar. Technol. Soc J.55, 34–49. doi: 10.4031/MTSJ.55.3.8

45

Von Schuckmann K. Godoy-Faundez A. Garçon V. Muller-Karger F. Evans K. Appeltans W. et al . (2025). Global ocean indicators: Marking pathways at the science-policy nexus. Mar. Policy128. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2025.106922

46

Von Schuckmann K. Holland E. Haugan P. Thomson P. (2020). Ocean science, data, and services for the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. Mar. Policy121. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104154

47

Wang Z. A. Moustahfid H. Mueller A. V. Michel A. P. M. Mowlem M. Glazer B. T. et al . (2019). Advancing observation of ocean biogeochemistry, biology, and ecosystems with cost-effective in situ sensing technologies. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00519

48

World Meteorological Organization (WMO) (2022). WMO unified data policy (Geneva: WMO). Available online at: https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/58009.

49

World Meteorological Organization (WMO) (2023). Manual on the WMO integrated global observing system (WMO-no. 1160) (Geneva: WMO). Available online at: https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/55063.

50

World Meteorological Organization (WMO) (2025). State of the global climate 2024 (WMO-no. 1368) (Geneva: WMO). Available online at: https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/69455.

Summary

Keywords

essential ocean variables, essential variables framework, global ocean observing system, ocean climate, ocean information, ocean monitoring, sustained observations, marine observations

Citation

Martín Míguez B, Heslop E, Bax N, Benedetti-Cecchi L, Canonico G, Currie K, Evans K, Fischer AS, Garçon V, Hood M, Karstensen J, Lara-López A, Legler D, Muller-Karger FE, Nair Thayannur Mullachery B, Nordlund LM, Palacz AP, Post J, Simmons SE, Speich S, Stukonytė L, Sutton AJ, Tanhua T, Telszewski M, von Schuckmann K, Waite AM and Yu W (2026) GOOS Essential Ocean Variables: the backbone of a sustained and evolving global ocean observing system. Front. Mar. Sci. 13:1737002. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2026.1737002

Received

31 October 2025

Revised

30 December 2025

Accepted

09 January 2026

Published

10 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Laura Lorenzoni, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), United States

Reviewed by

Anabel von Jackowski, Stockholm University, Sweden

Inia Soto Ramos, Morgan State University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Martín Míguez, Heslop, Bax, Benedetti-Cecchi, Canonico, Currie, Evans, Fischer, Garçon, Hood, Karstensen, Lara-López, Legler, Muller-Karger, Nair Thayannur Mullachery, Nordlund, Palacz, Post, Simmons, Speich, Stukonytė, Sutton, Tanhua, Telszewski, von Schuckmann, Waite and Yu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Belén Martín Míguez, bmartinmiguez@wmo.int; Lina Mtwana Nordlund, lina.mtwana.nordlund@geo.uu.se

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

ORCID: Véronique Garçon, orcid.org/0000-0002-4041-1379

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.