- 1School of Medicine, Deakin University, Geelong, VIC, Australia

- 2Rural Community Clinical School, School of Medicine, Deakin University, Colac, VIC, Australia

- 3Rural Clinical School, The University of Queensland, Rockhampton, QLD, Australia

- 4Deakin Rural Health, School of Medicine, Deakin University, Warrnambool, VIC, Australia

Introduction: With an increasing focus on social accountability in program design in response to a shortage of rural healthcare professionals, emerging approaches in pre-registration health professional education (HPE) offer ‘place-based’ solutions. This review assesses the adoption of these approaches by the international HPE community and describes how programs are designed to recruit and train students ‘in place’.

Methods: Utilizing a global scoping review, a search strategy of relevant HPE databases was developed based on the review’s eligibility criteria and key search terms. Titles and abstracts of all articles were screened against the review’s inclusion criteria, followed by full text review of articles retained. Reporting followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.

Results: Database searches identified 4,215 articles (1,526 duplicates). Title and abstract screening were completed, with 319 retained for full text review. Of these, 138 met the inclusion criteria, with 50 unique HPE programs from 12 countries identified, predominantly from medicine or nursing and midwifery. Programs often had a dual purpose to provide a rural workforce and increase access to HPE for under-represented groups. Recruitment strategies included preferential admission of local students, identifying students with rural or primary care intentions, community involvement in selection, and pre-entry programs. A typology of four training models was identified: short-term rural placements, extended rural placements, rural campuses, and distributed blended learning. Distributed blended learning occurred primarily in nursing and midwifery programs, enabling students to train in their home rural communities. Outcomes evaluated by programs focussed on graduates’ work locations, the effectiveness of widening access measures, and academic results.

Discussion: Despite heterogeneity of design and context, place-based programs were characterized by three common features closely aligned with social accountability: widening access to HPE, comprehensive program design and a community-engaged approach. Key considerations for place-based HPE program design are the geographical scale of the program, strategies for student recruitment from the target region, provision of continuity with rural communities through longitudinal training experiences, engaging communities in the design and delivery of the program, and alignment of evaluation with the goals of the program and the communities served.

Introduction

A shortage of rural healthcare professionals is a global phenomenon that crosses economic, geographic, and health professional discipline boundaries (1–5). There is a need to identify and adopt evidence-based strategies to address this challenge, including through health professional education (HPE) program design (1, 6, 7). Universities act as gatekeepers to the majority of HPE pre-registration training (undergraduate and post-graduate pathways prior to professional registration) and play a critical role in determining who is selected by these programs. High levels of competition for course places and an emphasis on academic attainment favor students of metropolitan origin, largely due to their relative educational, resource and socio-economic advantage (8, 9). Traditionally, universities have also been based in more populated settings, thus reducing access for rural-based applicants, although there have been deliberate policy initiatives this century, such as Australia’s Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) Program, supporting increased rurally-based health professional training (10, 11).

In such an environment, the focus of rural workforce recruitment has often been, understandably, on ‘attract and retain’, with a myriad of strategies focused on enticing a population of predominantly metropolitan based, and trained, graduates into rural practice (1, 12). At the pre-registration level, such strategies have included mandatory periods of rural training, bonded return of service schemes, financial incentives linked to rural practice, and rural curricula (1, 4, 5, 7). In Australia, targeted recruitment of rural background students into pre-registration HPE (particularly in medicine) has been a longstanding strategy aiming to improve rural workforce outcomes, yet this measure alone has not been sufficient to address the maldistribution in that country (13).

There is a substantial body of empirical research that provides guidance on the individual factors associated with enhanced rural health workforce outcomes such as rural origin and longitudinal rural training (14–18). However, there is less evidence available to inform how these individual variables might interact within a complex system, or how programs have been designed and evaluated that incorporate multiple elements. The 2021 WHO guidelines on rural and remote health workforce development included a recommendation for ‘bundling’ of initiatives, as a more effective strategy than isolated interventions (1). Similarly, within medical education there has been increasing discourse on the importance of comprehensive approaches to program design, where several design elements are included (such as rural student selection, extended rural training, and rural curricula) with the expectation of an enhanced outcome (6, 19–21).

The role and importance of social accountability in HPE has gained prominence since the beginning of the 21st century (22–24). Social accountability of educational institutions is defined as ‘the obligation to direct their education, research and service activities toward addressing the priority health concerns of the community, region, or nation that they have a mandate to serve’ (25). The increasing focus on social accountability is reflected in the strengthened recommendations in the 2021 WHO guidelines. Notably, they state that all health workforce education institutions are ‘obliged’ to adopt social accountability as a core part of their mandate to develop a relevant and appropriate workforce (1).

With an increasing focus on both social accountability and comprehensive program design, emerging alternatives to ‘attract and retain’ in HPE have been described as ‘growing your own’ or ‘place-based’ solutions (26–29). These two phrases convey different emphases but share an overlapping purpose to recruit and train students from and for a specific place. ‘Growing your own’ emphasizes the recruitment of students already embedded in rural communities and providing them with access to training opportunities, ideally in the local area (26, 27). ‘Place-based’ approaches recognize that education is inexorably grounded in the place and context in which it occurs (29). Place-based education (PBE) seeks to strengthen students’ connections with their location and community through the context, content, and pedagogy of curriculum delivery (30–32).

The purpose of this scoping review is to assess the extent of adoption of these approaches by the international HPE community and describe how programs are being comprehensively designed to achieve these goals. A synthesis of the literature on program design in place-based HPE will provide a summary of this evolving field, that will inform contemporary program design and evaluation. Following a search of completed and in-progress reviews, including contacting authors of two reviews in progress on rural PBE, it was determined that the proposed review was substantially different in focus.

Objectives

This scoping review will identify rural pre-registration HPE programs in the international literature that are adopting a place-based approach to recruiting and training students in a defined geographic region. The review will synthesize the literature to answer the following research questions:

1. What is the global distribution of rural place-based pre-registration HPE programs and how is their concept and purpose described?

2. How is this concept translated into HPE program design?

a) How is place defined geographically?

b) How is place-based student recruitment occurring?

c) How are place-based training and recruitment co-occurring?

d) What program outcomes are being investigated?

Methods

This scoping review was conducted using Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review guidelines (33) and follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis extension for scoping reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR) (34) (Supplementary file 1). The review protocol was registered with Open Science Framework (osf.io/56dcf) on 29th May 2024.

Inclusion criteria

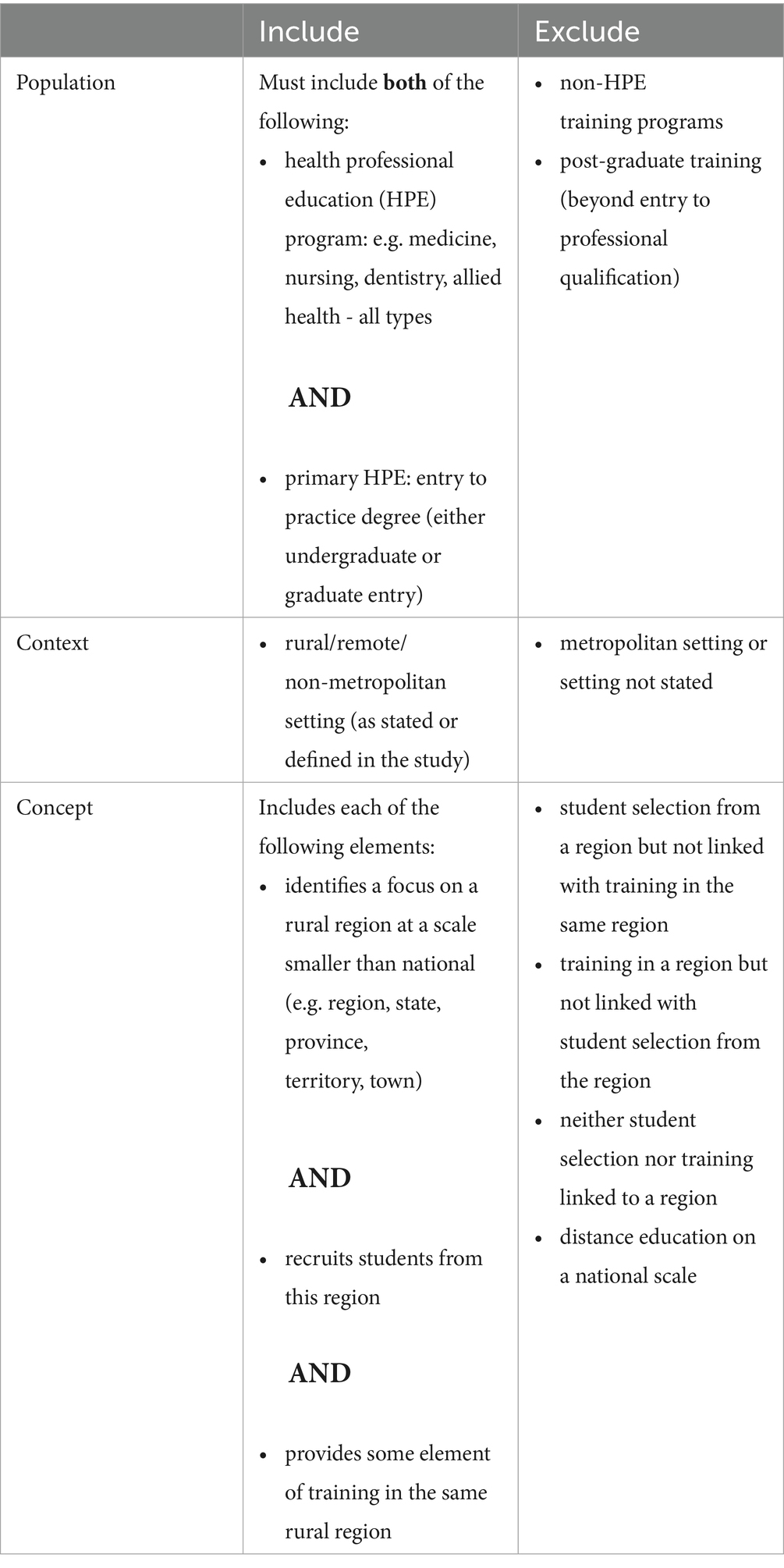

The population, context, and concept framework was used to construct the review’s inclusion criteria (Table 1).

No restrictions were placed on the type of evidence sources considered for inclusion, with evidence syntheses, editorials and conference presentations considered along with all types of original research study design. There were no restrictions placed on publication date, to allow for a historical perspective on this topic. Only articles available in English were included.

Information sources

Databases were chosen due to their relevance to HPE: Medline, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and ERIC (Ebscohost), Scopus, and Excerpta Medica database (Embase). Due to the large number of papers identified for screening by the primary database search, the pragmatic decision was taken not to widen the search to grey literature, snowball or hand searching of references, to keep the review size manageable.

Search strategy

A search strategy was developed based on the review’s eligibility criteria and key search terms identified in papers known to the authors. Search terms were developed using relevant index search terms, keywords, and truncation symbols translated to each individual database and searched separately (Supplementary file 2). Search terms relating to the allied health professions were developed based on terminology used by representative bodies of allied HPE in Australia, United States of America, United Kingdom, and peer-reviewed literature.

Several reference papers known to the authors were used to validate the search strategy. The search strategy was trialed and refined to extract relevant papers from the literature.

Study selection and data charting

Citations of all articles identified by the database search were exported to Endnote 21 reference library (Clarivate™) and then imported to CovidenceTM (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for screening. Duplicates were identified and removed by Covidence software, and any remaining duplicates were manually removed during the screening process. Two reviewers (LF and JB) independently screened the title and abstract of all articles against the review’s inclusion criteria. Full text review was then performed independently by the same two reviewers, with reasons provided when articles did not meet the review’s inclusion criteria. Conflicts were resolved by discussion between JB and LF periodically during the screening process.

A data extraction template and guidance document were developed and piloted by two authors (LF and JB), following which data were charted for each included article (LF and JB). Categorical outcomes for extracted data where relevant, were determined during the trialing phase. Data charted by each reviewer were compared during the synthesis of the results, with discrepancies resolved by referring to the primary information source (LF).

For evidence sources that included both rural and metropolitan programs, only rural program information was charted. For literature such as reviews that included multiple programs, only data for programs that met the review’s inclusion criteria were charted. First or corresponding authors were contacted during full text review if additional information was required to determine whether programs met the review’s inclusion criteria. Quality appraisal of articles was not undertaken, consistent with scoping review methodology (33).

Data items

The following data were extracted to answer the review’s questions:

Population: program name, program provider, program description, year of commencement, health profession, entry level (undergraduate/post-graduate), return of service requirements.

Context: country, state/province/location, rurality classification of program.

Concept: terminology used to describe program’s concept, program purpose, place definition, student selection/recruitment methods, rural training delivery (duration, context, clerkship model), outcome measures.

Metadata of included studies reported included authors, evidence source and year of publication.

Results

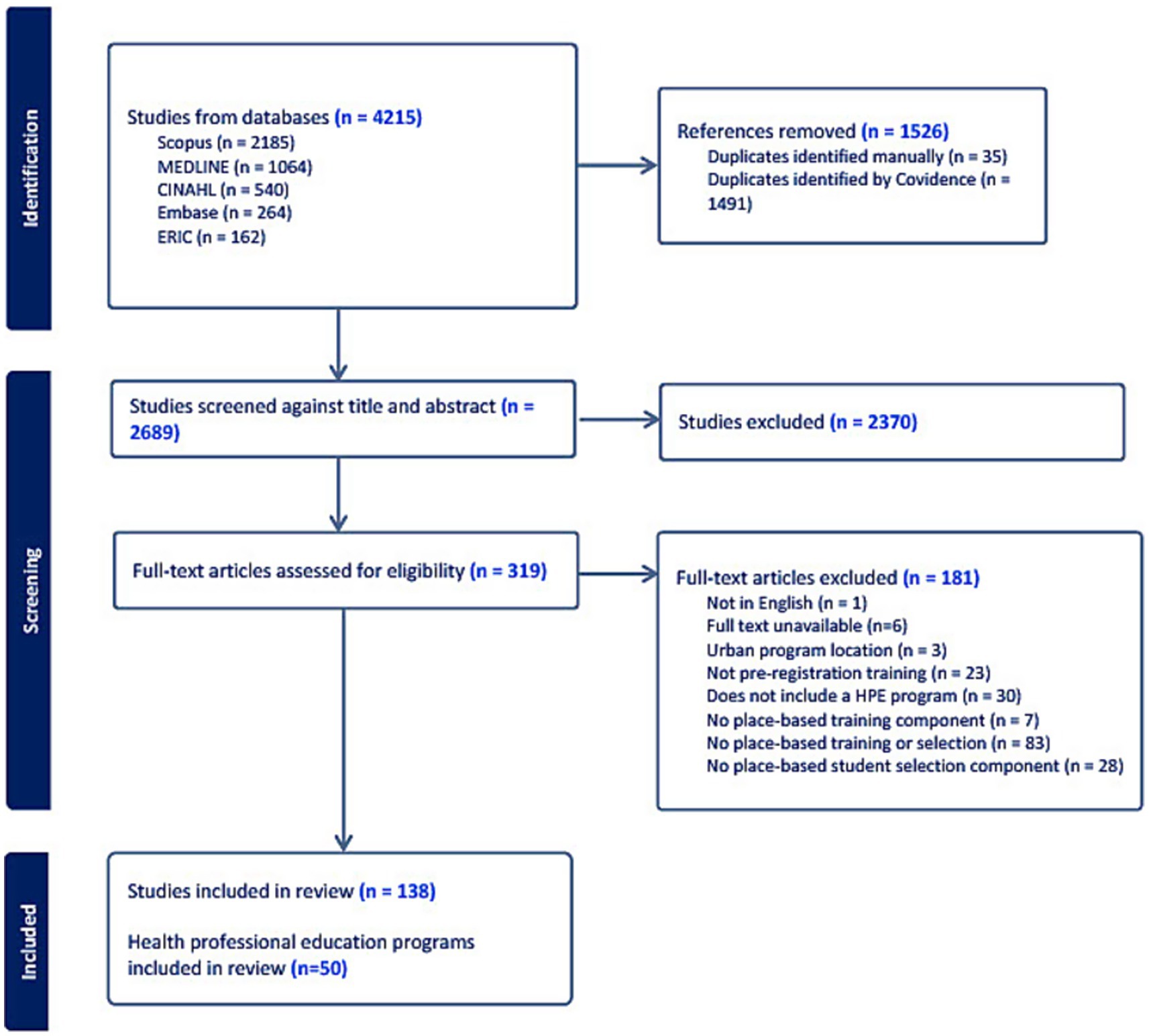

Database searches conducted on 4th October 2023, identified 4,215 articles. Following the removal of 1,526 duplicates, 2,689 studies were screened by title and abstract against the inclusion criteria, with 2,370 excluded at this stage. Full text review of 319 articles was completed, with 181 studies excluded for the following reasons: no place-based training or selection (n = 83), no place-based selection (n = 28), not a HPE program (n = 30), not pre-registration training (n = 23), no place-based training component (n = 7), full text unavailable (n = 6), urban program location (n = 3), not available in English (n = 1) (Figure 1 PRISMA-ScR flow diagram).

One hundred thirty-eight information sources met the review’s inclusion criteria, relating to 50 unique programs. Information sources included journal articles (n = 129), organizational reports (n = 4), symposium/conference proceedings (n = 2), a thesis (n = 1), a book chapter (n = 1), and a WHO bulletin (n = 1).

Research question 1: What is the global distribution of rural place-based pre-registration HPE programs and how is their concept and purpose described?

Global distribution

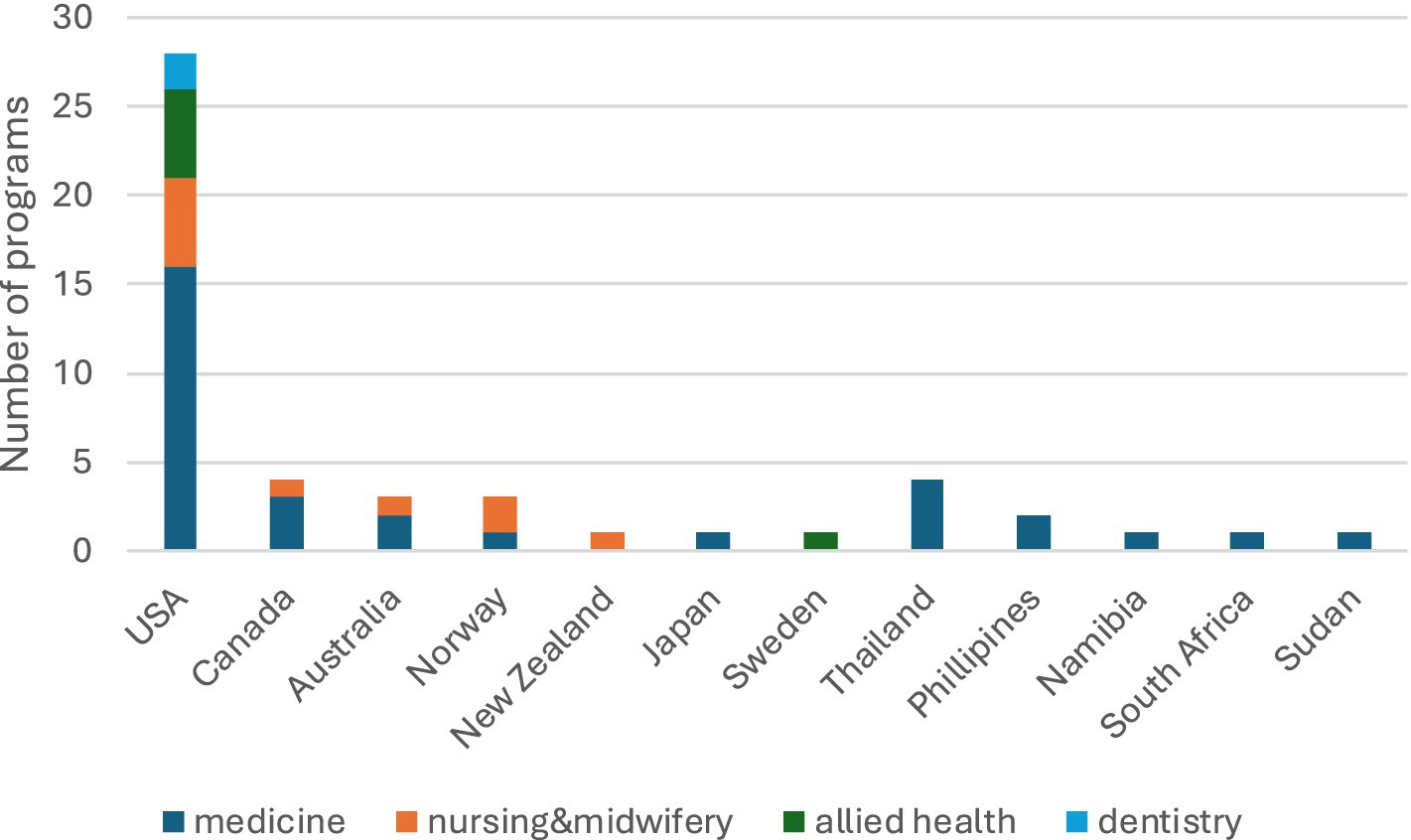

Of the 50 included programs across 12 different countries, 28 were in the USA, with smaller numbers in Canada (n = 4), Thailand (n = 4), Australia (n = 3), Norway (n = 3), the Philippines (n = 2) and single programs in Japan, New Zealand, Sweden, South Africa, Sudan and Namibia (Figure 2). Programs were included from seven high income countries (n = 41) and five low and middle income countries (n = 9) (35) and from five of the six WHO regions, the Eastern Mediterranean Region being the exception (36). Forty programs related to a single educational institution (27 medicine, 9 nursing, 1 dental, 3 allied health), six to a collaborative of more than one institution (1 medicine, 1 nursing, 1 dental, 3 allied health) and four to national level government initiatives (medicine).

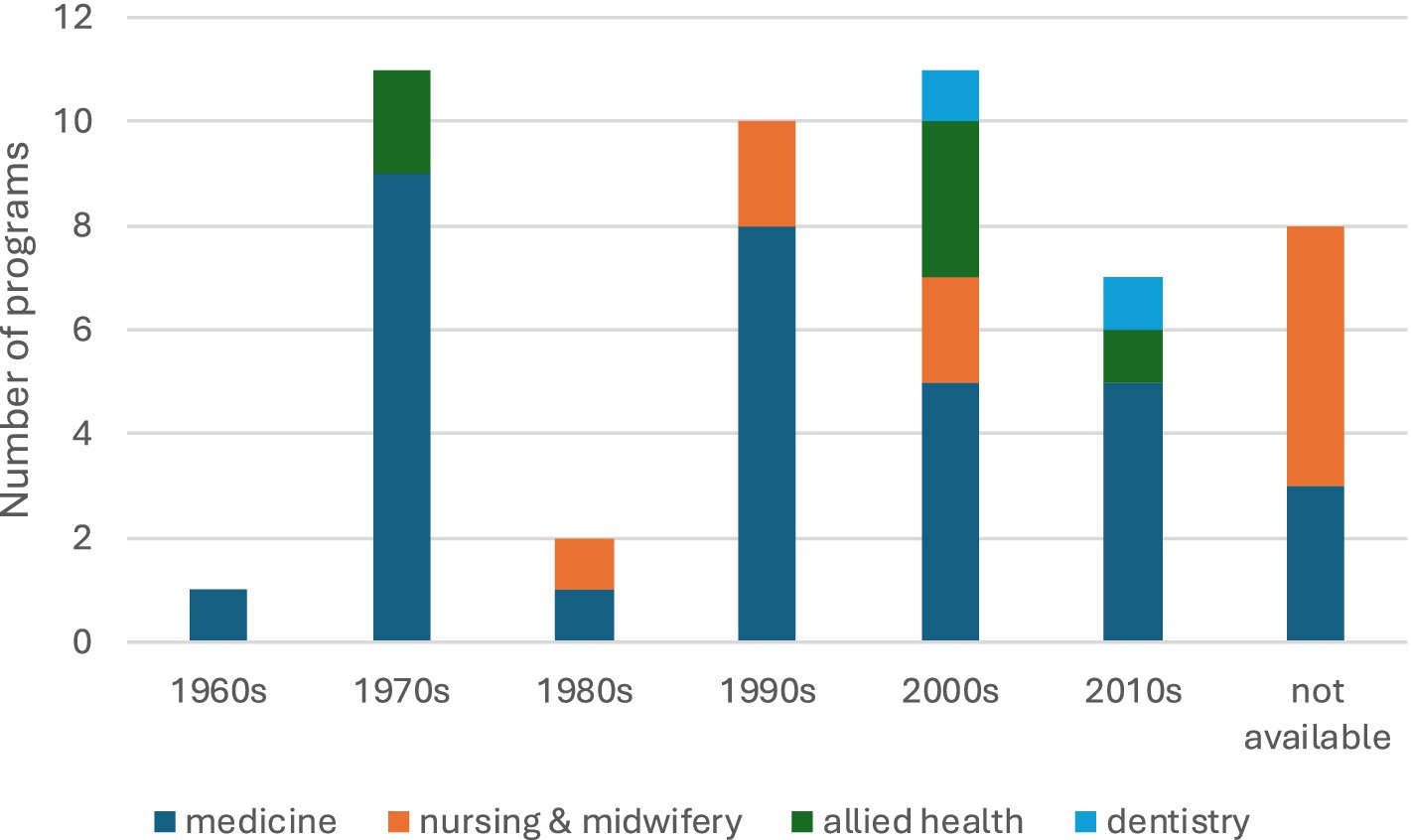

The commencement dates of programs ranged from 1967 to 2017. Programs in medicine preceded programs in the other health professional disciplines (Figure 3). Programs are listed in order of commencement date in Table 2 (medical programs) and Table 3 (non-medical programs).

Conceptualisation and purpose

The concept of a ‘place-based’ approach was evident in terminology used by many programs, although only one used this precise term (29). Concepts used to describe place-based programs included ‘learn where you live’ (37) and ‘grow your own’ (28, 38). Other place-related language included ‘sense of place’ (acknowledging the existence of place connection, importance of access and opportunity and approaches to strengthening place connection through training) (37, 39), ‘local’ [usually with reference to the location of the medical school) (40–44), ‘home’ or ‘hometown’ (in relation to allowing students to study in or near their home communities (38, 45–47) or evaluating the retention of students or graduates in their home areas (47–51)] and ‘place-bound’ referring to rural nursing or allied health students with reduced geographic mobility restricting educational access (52–55).

All 50 programs had a clear purpose related to improving rural workforce outcomes. Programs with a predominant workforce purpose used terminology such as ‘rural pipeline’ (20, 21, 39, 44, 56–60) or ‘rural track’ (57, 61, 62) to describe a deliberate approach to provide a separate stream of recruitment and training specifically focussed on achieving rural workforce outcomes. Programs were also described as being ‘comprehensive’ (20, 21, 57, 63, 64) when they included multifaceted, coordinated initiatives including targeted recruitment, admissions, curriculum, support, and evaluation components spanning the training continuum to achieve workforce goals.

There was an equity-driven purpose identified in many programs, underpinned by a social accountability framework. This was evident through the frequent use of the term ‘underserved areas’ (5, 39, 43, 53, 54, 56, 59, 65–72) to describe priority areas for workforce improvements. The term ‘underserved’ was often not precisely defined but was frequently inclusive of rural areas (rural underserved) but also extended the program’s focus beyond rural areas alone (rural and underserved). Underserved areas were sometimes defined by medical programs as having low physician to population ratios (61, 73, 74).

The majority of programs (n = 38/50) demonstrated a social accountability mandate through a concurrent purpose to address both rural workforce needs and widen access to their educational programs for students from rural areas or other under-represented populations. Population groups that were targeted under widening access measures related to each program’s context, and included Indigenous populations (Australia, Canada, USA), Francophone speakers (Canada), and those experiencing socio-economic or socio-cultural disadvantage (USA) (75). A dual focus on widening access and workforce outcomes was more prevalent in the non-medical programs.

Social accountability was also evident in terminology applied to community-centered educational models, including community-‘engaged’ (29, 37, 76), ‘oriented’ (77) or ‘based’ (76–78). Educational models that emphasized rural community-based learning to increase access for rural students were described as ‘distributed’ (37, 58, 79–83), ‘decentralised’ (43, 58, 77, 78, 81, 84–87), ‘distance education’ (37, 38, 41, 47, 53, 54, 67, 88, 89),’ learn where you live’ (37) or as a ‘flipped model’ (49).

Research question 2: how is this concept translated into pre-registration HPE program design?

How is ‘place’ defined geographically?

Often very large jurisdictional sub-divisions, such as states, territories, and provinces were used by programs in the USA (n = 12), Canada (n = 1), and Australia (n = 2) to define a program’s place of focus. This approach was particularly evident in the USA where the workforce purpose of programs was frequently stated in terms of providing a workforce for rural areas of the state in which the program was based, for example, ‘training Kentuckians in Kentucky to practice in Kentucky’ (90). Reference to one or more rural counties was also used to further clarify geographic focus, evident in the USA (43, 90, 91) and European programs (47, 86). For example, Umea University’s web-based pharmacy program focussed on three rural counties in Northern Sweden in which local study groups were established (47). Countries smaller in land mass tended to use smaller geographic areas to define their place-based focus, assisted by higher resolution national-level geographic subdivisions such as provinces in Thailand (92), and prefectures in the Philippines (93) and Japan (94).

Approximately one-third of programs (n = 16) employed descriptive approaches alone to define their region of focus, specific to their context and with an absence of reference to any political or geographical rural subdivisions. Examples include ‘northern’ (37, 38, 95) ‘western’ (39) or ‘southern’ (41, 43) areas of a state or province, or the description of geographical landmarks or boundaries defining an area (53, 70, 82). For example, the University of California Davis Programs in Medical Education (PRIME) describes their region as ‘rural Northern California regions from Sacramento to the Oregon and Nevada borders’ (70).

The rurality of program locations was inconsistently defined, often without reference to a formal geographic classification system. When provided, descriptors included the proportion of the region defined as rural by statistical measures, population density, population and/or size of the region or training site, distance of training sites from major campuses or cities, and physician-to-population ratios (Tables 2, 3).

How is place-based student recruitment occurring?

Although all programs included some form of rural student recruitment, detail was often lacking to determine precisely how this was occurring, and the extent to which this was place-based. At a strategic level, the establishment of rural campuses in areas of workforce shortages was a mechanism used to attract local applicants to programs (39, 69, 90). It was observed that the location of rural learning sites for distance education programs heavily influences who participates in these programs (20, 22, 47, 70).

Recruitment in many cases began some years ahead of health professional training commencement, through the provision of formal pre-entry pathways (39, 44, 46, 56). Common in the USA, pre-entry pathways often included cooperative arrangements with undergraduate institutions in the state (39, 74), and offered guaranteed admission if academic standards were maintained (44, 46, 56). Further targeted pre-entry recruitment strategies were implemented by programs within their communities, including quota-based arrangements with local high schools (92, 94, 96) and active marketing and recruitment (41, 52, 53, 59, 67, 97). Pre-entry programs provided students with clear entry pathways to health professional training as well as often providing opportunities for rural and healthcare exposure to consolidate rural interest prior to course commencement (39, 56).

At the point of course entry, a wide range of approaches were used that attempted to identify and select students aligned with the goals of the program. There were only two examples of admission processes that aimed to identify suitability for a specific place: the Remote Suitability Score developed by the University of British Columbia for their Northern program (98), and Northern Ontario School of Medicine’s (NOSM) context score, aligned with the admission of students reflecting Northern Ontario’s population demographics (22). Other programs reflected on the influence of the learning locations on the students who participated, leading to the conclusion that study sites can be strategically located to recruit students from target areas of workforce shortage (47, 86).

Admission quotas were used on a national (94) or regional scale (40, 42, 46, 75, 87, 99, 100) to facilitate preferential admission for rural students. Preferential admission of students from the area of focus (28, 100, 101) or rural areas generally (21, 44, 102–104) was also mentioned without stating a specific quota requirement. Demonstration of rural residence or background in the region of focus was commonly a requirement, although detail was not always provided on how this was assessed. Mechanisms that were described included providing evidence of a minimum number of years spent living in a defined rural region (44, 62, 74), small hometown (21, 44, 104–106), or attending a rural high school (44, 46).

Tailored admission requirements were commonly observed across program types, including a reduced emphasis on academic attainment (39, 40, 44, 100), program-specific exams (40, 107), waiver of aptitude tests (39, 108), and score adjustments for educational disadvantage (99, 109). Some medical programs retained the full admission requirements of the main medical program with additional requirements for the rural pathway, such as current or previous residence in a rural underserved area (74, 102), interviews (20, 70, 101, 102), and letters of recommendation (20, 74).

Several studies described mechanisms for community involvement in student recruitment, with their contributions including personal letters of recommendation (20, 74, 97), student nomination/endorsement (62, 103), involvement in interviews (100), and admission committees (20, 44).

Beyond seeking students from a rural background, admissions processes were often employed to identify students considered more likely to enter rural and/or primary care practice. Assessment of rural identity and intent for rural practice was sought through personal statements (22, 98, 109) and admissions committee interviews (20, 44, 46, 56, 59, 70, 74, 99, 100, 102, 109), by seeking pertinent life experiences and characteristics (104), and rural lifestyle/hobbies (44, 98). Several USA programs had a strong focus on recruiting students with an intention for family medicine practice (20, 46, 74, 110) or generalist practice (44, 70). Evidence of community service was sought as a characteristic of students suitable for program participation (20–22, 59, 70, 104) and, in medicine, this was deemed to be a trait associated with future family medicine practice (21, 77).

How are place-based training and recruitment co-occurring?

The authors of this review have classified a typology of included programs according to four main models of rural training delivery (Table 4).

In Type 1 programs: short rural placements (medicine: n = 5, dentistry: n = 1, pharmacy: n = 1), rural stream students are attached to a larger mainstream urban program and participate in one or more short term rural rotations. The duration varies from 8 weeks of clinical placement to multiple separate short-term rotations across all years of the course. For example, at the University of New Mexico (USA), students complete a practical rural immersion in their first year, and clinical rotations in rural areas in later years (66). Although programs in this category offer training within the program’s defined rural region of varying durations, it was often not clear whether mechanisms were in place to allow students to experience continuity with a single rural community, or their home community, when they undertake more than one rural placement during their course. Jichi Medical University (Japan) reported that students spent ‘some weeks’ in their home prefectures in 5th year (94). In contrast, UC Davis rural-PRIME (USA) rotates students between five different rural communities for their third-year clerkships to experience different systems of care.

In Type 2 programs: extended rural placements (medicine: n = 21, dentistry: n = 1, allied health: n = 1), rural stream students complete pre-clinical training at an urban campus but undertake at least one extended period of rural placement (≥12 weeks). This model describes most included medical programs, although there is considerable variation in the structure and timing of rural placements. Several programs are structured around a number of years of initial urban campus-based pre-clinical training followed by relocation for subsequent years of rural clinical training. An example is the Collaborative Project to Increase Production of Rural Doctors program (Thailand) where rural track students complete their first three years jointly at universities with ‘normal track’ students, then relocate to regional and provincial hospitals in their home communities for their three clinical years (92, 107). In other programs, such as NOSM (Canada), students participate in several eight-week rural immersion experiences in the early years, followed by an eight-month community-based rural longitudinal integrated clerkship in third year (111, 112).

There were few examples of programs of this type that deliberately connect students with a single rural community or their home region for rural placements (68, 99, 102). An exemplar is the Targeted Rural Underserved Track (TRUST, USA), which provides students with a longitudinal curriculum connected to a single rural continuity site, throughout the course duration. By contrast, NOSM deliberately provides students with a diverse range of rural community placements in Northern Ontario (113). Most other programs of this type did not provide information on whether students’ rural placements provided continuity with their home or another rural community over time.

In Type 3 programs: rural campuses (medicine: n = 4), the entire training duration occurs in a rural location. These programs were confined to medical schools established in rural states or areas. Australian examples are the Northern Territory Medical program and James Cook University, with all four years of delivery based at rural campuses and training sites. Preferential student recruitment to these programs occurs at the level of the state or region of the medical school, suggesting that students may be required to relocate from their home communities to attend these rural campuses. The included articles did not provide details on the process by which students were matched to a rural training campus to determine whether their home rural community was a key consideration. An expectation of these programs was that the establishment of a new rural campus would attract students from that location into the course, who would then choose to train there (69, 114).

In Type 4 programs: distributed blended learning (nursing & midwifery: n = 9, occupational therapy: n = 1, pharmacy: n = 1), confined to nursing & midwifery and allied health programs, students complete their studies without leaving the rural communities in which they live (37, 38, 41, 47, 53, 54, 67, 88, 89). Learners are often more widely dispersed across a rural region and in smaller groups, with education delivered through blended learning, combining online curriculum delivery with local, site-based teaching and supervision. Decentralized training sites were often strategically established in areas of workforce shortages, with small groups of students working with local clinical preceptors (52, 89, 115). An example of this model is the Eastern Shore of Virginia Registered Nurse to Bachelor of Science in Nursing program delivered via online asynchronous distance learning, in partnership with local hospital preceptors and study facilities.

What program outcomes are being investigated?

The scope of outcomes evaluated was broad, with three main areas studied: (i) graduate workforce outcomes, (ii) success in widening access to HPE programs, and (iii) academic outcomes. In addition, a range of other impacts of programs were evaluated, with a full list available in Table 5.

Most program outcomes were evaluated through cross-sectional and retrospective single or multi-cohort studies using surveys (39, 43, 49, 78, 79, 81, 85, 97, 101–103, 107, 116–129), data linkage of school-held administrative data with publicly available practice location data (42, 43, 47, 56, 58, 74, 79, 84, 92, 95, 106, 130–138) or admissions data analysis (139, 140). Other types of studies included prospective cohort studies (54, 75, 100, 108, 141–143), case studies (44, 60, 62, 65, 91, 93, 99, 144, 145), program descriptions/project reports (20, 21, 28, 37, 38, 46, 50, 52, 53, 55, 57, 61, 68–70, 73, 83, 86, 88–90, 96, 98, 109, 112–115, 146–155), reviews (5, 19, 76, 77, 87, 156, 157), commentaries/policy analysis (22, 41, 113, 144, 158–160), editorials (64, 105, 161, 162), an economic review (80), a conceptual framework (163), and a typology (66).

Early program evaluations demonstrated an interest in the academic equivalence of rural stream students to their urban counterparts, through measures including assessment results (21, 28, 44, 69, 77, 151), clinical competency assessments (21, 103, 122, 146, 151, 157), development of social accountability competencies (54, 76, 103, 116, 118, 122), attrition and retention rates (37, 56, 70, 86, 89, 140), medical licensing exam results (44, 45, 93, 103, 113, 135, 144, 151) and progression to post-graduate degrees and residency programs (21, 54, 160). One program reported distributed learning as the most important factor in increasing the success of Indigenous students in nursing education (37).

Early graduate workforce outcomes (1–5 years) evaluated included graduates’ career intentions when entering and exiting medical school (75, 116, 124–126, 128, 143), first practice locations (43, 54, 56, 58, 81, 84–86, 103, 124, 126, 128, 135, 143, 144), and intention to emigrate (48, 75, 91, 164). Programs evaluating mid-career (5–10 year) graduate outcomes investigated the impact of specialty training vocation on rural practice (74, 79, 103, 118, 128, 129, 131, 134, 137), and retention in rural practice (74, 85, 156), including after the completion of mandatory training or return of service periods (5, 28, 45, 71, 72, 165). Longer-established programs evaluated outcomes of multiple cohorts, including rural practice locations in late career (>10 years) (5, 19, 20, 77, 103, 104, 119, 131, 134, 160), and long-term graduate retention in rural practice (5, 19, 77, 138, 160).

Locally relevant rurality classification systems were used to determine the number of graduates in rural practice (Table 5). In the USA, these included non-Metropolitan Statistical Area counties (39, 56, 68, 74, 77, 104, 110, 115, 156) and Rural–Urban Communing Area (RUCA) codes (20, 135). Canadian programs used Statistics Canada census subdivision of <10,000 population as the definition of a rural community (58, 79, 106, 129, 133). Australian programs utilized the Australian Statistical Geography Standard Remoteness Areas (ASGS-RA) (124, 132, 166) and Modified Monash Model (MM) (131) to classify the rurality of practice locations. Internationally, programs also reported rural outcomes with reference to an upper limit of the town’s population, commonly <25,000, <30,000 or <50,000 (19, 56, 101, 106, 116, 156, 165). Frequently, a precise description of the way that graduate rural practice location was determined by programs was not provided (5, 19, 22, 44, 54, 58, 64, 77, 93, 104, 143, 144, 146, 151, 154, 158, 160).

Interest in graduates’ work locations went beyond binary outcomes of rural or metropolitan practice to evaluate the program’s place-based outcomes. These measures included the proportion of graduates practicing in the program’s state/province/prefecture or region (5, 19, 28, 42, 44, 47–49, 56, 64, 77, 79, 93, 110, 113, 128, 129, 131, 143, 151, 154) or in their home state/territory/province/prefecture or other region of origin (48, 64, 77, 94, 106, 133, 134, 155, 165). A small number of programs reported on the contribution of a particular program’s graduates to the region of interest’s workforce (5, 74, 134, 138, 144), including improvements in the availability of junior doctors or physicians in areas of need (65, 76, 93). Involvement in working with under-represented population groups (59, 76, 79, 100, 117, 119, 122, 159) or in underserved areas (5, 43, 77, 93, 100, 103, 110, 119, 141, 156) was also reported (Table 5).

The specialty and context of medical graduates’ practice were commonly evaluated, with a particular focus on family medicine (5, 20, 21, 44, 49, 56, 74, 77, 79, 87, 102, 103, 106, 122, 131, 135, 138, 142, 144, 151, 154, 156, 157, 160), primary care (20, 21, 44, 48, 77, 94, 102, 110, 154, 156, 157) or generalist practice (78, 79, 110, 116, 118, 123), often linked with the greatest workforce needs of the communities being served.

Programs evaluated the impact of widening access to HPE initiatives by investigating the presence of under-represented population groups in their student cohort (Table 5). Programs reported on the presence of rural background students in their cohort (21, 22, 39, 75, 79, 97, 99, 105, 106, 109, 114, 135, 141, 144), and on the presence of students from the program’s defined region (21, 28, 39, 47, 48, 64, 85–89, 91, 108, 109, 114, 151). Other cohort demographics reported included socio-economic status (75, 118, 141), educational background (75, 94, 141), Aboriginal and Francophone student representation (28, 37, 79, 88, 99, 144, 151), and self-identification with an underserved population group (59, 75, 100, 141).

There was limited investigation of the outcomes for the communities in which programs were being delivered. Outcomes evaluated included the correlation of student projects with community needs (21, 93), economic impacts (151, 157) and physician availability (65, 76, 93). There was also a notable absence of published findings regarding the experiences of students and graduates participating in these programs.

Discussion

Place-based programs identified in this review varied significantly in their geographical scale and design, in part due to the inclusion criteria that allowed for programs up to large state or provincial level in size and the inclusion of a broad range of rural training models. The predominance of medicine in the included programs likely reflects the greater volume of published literature on medical graduate workforce outcomes, which in some countries such as Australia, is a program funding requirement (11).

Despite this heterogeneity and the contextualisation within their global settings, programs were found to be characterized by three common features. Firstly, a comprehensive program design linking targeted student recruitment, rural training and evaluation of relevant outcomes, secondly, a focus on widening access to HPE opportunities, and thirdly, a community-engaged approach. These features align closely with key principles of social accountability, suggesting synergies between social accountability and place-based approaches (29).

Comprehensive place-based program design

Comprehensive program design refers to the use of multiple interventions or bundled strategies to achieve a program’s goals (1, 6, 20, 21). Programs demonstrated a comprehensive approach to achieving their place-based workforce goals, through targeted recruitment strategies and pre-entry programs, purposeful admission processes and requirements, recurrent or extended training experiences in rural communities and evaluation of outcomes designed to assess the effectiveness of these strategies.

Approaches to student recruitment were heterogenous, illustrating both the lack of a ‘gold standard’ approach and the need for this to be contextualized for each program’s setting. Common characteristics of place-based recruitment were the presence of pre-entry programs that facilitated early connection with local students, strategies to preferentially admit rural students from the region through adjusted admission requirements, and the involvement of the local community in the recruitment process. For medical programs, attributes commonly assessed through a suite of admission requirements included academic capability, rural commitment and often primary care career intentions. These strategies demonstrated that programs were interested not only in rural outcomes, but also in the development of a generalist workforce that would meet the primary healthcare needs of rural communities.

The variation in the geographical scale at which place-based recruitment and training occurred calls for reflection on ideal or preferred approaches. Large state or provincial programs often recruited broadly from their rural region and required students to relocate on more than one occasion for rural training experiences (Table 4, Types 1 and 2), some explicitly valuing the variety of exposure this provided. Other programs had clear mechanisms for students to foster a longitudinal relationship with a single rural community, through entirely rural campus-based programs, or distance education (Table 4, Types 3 and 4). Distance education models (Type 4), prominent in nursing and midwifery, prioritized local student recruitment and keeping learners in their home communities throughout training.

These variations in approach may be due to both practical and pedagogical influences. The absence of Type 4 distance education models in medicine may reflect traditional Flexnerian educational approaches with a period of on-campus pre-clinical learning, allowing for exposure to scientific laboratories and anatomical specimens (167). Extended rural placements have become increasingly common for clinical learning in medicine, illustrated by the predominance of this program design in Table 4. Following the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic during 2019–2021, it will be interesting to observe whether there is an increased uptake of blended learning delivery inclusive of distance education for medical programs. Many programs were forced to ‘pivot’ rapidly to online delivery of learning during the pandemic, a disruptive event that may have an ongoing impact on how programs are delivered that is not yet apparent in the literature (168, 169).

The provision of continuity with a rural community throughout training aligns with evidence that extended rural placements are associated with enhanced rural workforce development (6, 18). Extended rural placements allow students to develop and strengthen their rural identity and self-efficacy, participate more fully as members of the clinical team, and develop meaningful relationships within the community (6, 170–172). Studies that have examined the effect of extended rural training within a student’s own rural region of origin have demonstrated even greater workforce benefits (26). Repeated exposure that provides continuity with the same rural community throughout training, including extended periods of placement time in a students’ home rural community, has the potential to be an important defining feature of authentic place-based program design.

An important consideration is that purposeful selection of students, and location of training sites is not always under the control of individual programs but may be subject to the national policy context. For example, in Australia, rural students are equally eligible for government-mandated rural admission quotas at any rural medical program in the country, meaning students often apply broadly and may relocate long distances for their studies. In contrast in Japan and Thailand, admission quotas operate at a provincial or district level, encouraging a more localised place-based approach. Thus, programs may have been constrained by the policy environment in the extent to which they were able to adopt a place-based approach to student selection and training.

The diversity of outcomes evaluated by programs was perhaps unsurprising given the heterogeneity of included programs. The proposal in this review of a typology distinguishing four models of rural training potentially allows for future identification and comparison of outcomes for narrower clusters of programs with more similar place-based approaches. The utilization of program logic models is recommended to clarify and visually represent the goals and components of programs and how outcomes being evaluated relate to these goals (173, 174). In this way, evaluation can be more clearly linked to the core purposes of these programs to provide a fit-for-purpose rural workforce for their region. The adoption of a program logic model may also draw attention to the importance of evaluating the experience of students participating in these programs, an area identified as a current gap in the literature. Program logic models prompt the development of outcome goals across short, medium and long-term timeframes which would help to shift attention from early outcomes (such as academic equivalence) to evaluate longer term impacts on rural communities, for example improving access to healthcare and health outcomes for underserved populations. Furthermore, the use of program logic models would provide a consistent framework for place-based program description, whilst allowing for customization and clear identification of local contextual factors and assumptions impacting on program design.

Reporting on workforce outcomes for the region of interest, an important feature of place-based programs, is recommended. Ideally, this should include not only the proportion of program graduates working in the region and in primary care but also the contribution of the program’s graduates to the workforce in the region, including other priority specialties based on community needs. A closer examination of workforce outcomes for a more limited range of programs sharing similar design features is warranted to identify factors that positively contribute to graduates working ‘in place’. Programs are encouraged to utilize and clearly define rurality classification systems to describe their place-based geography and apply these measures consistently to student recruitment, training site locations and the measurement of workforce outcomes. This would assist with transparency of how rurality is defined and applied in all elements of program design and enable comparisons to be made between similar programs (175, 176).

Widening access

Programs expressed clear goals to train fit-for-purpose healthcare professionals for rural and underserved communities, to improve health outcomes for these communities. This ‘back-end’ purpose, to meet societal needs was, in most programs, also associated with a ‘front-end’ purpose, to widen access to their educational programs for students from these same communities (177). While this secondary purpose to widen access was clearly articulated for some programs, for others it could be inferred through the outcomes of interest that were evaluated, for example, the diversity of the student cohort. This duality of purpose to widen access for underserved population groups from the region and train in and for the region could be considered an identifying hallmark of PBE programs. It is noteworthy that the scale on which these strategies were applied varied significantly, from small rural provinces to entire states, prompting consideration of possible upper limits of scale at which a program could be described as truly place-based.

Place-based program design was found to address both spatial (geographic) and aspatial (economic, socio-cultural, political) barriers to program participation (178). Spatial barriers were addressed by the location of rural learning sites, either through the establishment of new campuses or through de-centralized, distributed learning models. Aspatial barriers, such as financial disadvantage, were also addressed by programs that allowed students to complete their course without the expense involved in relocation, or through the provision of financial assistance. Socio-cultural barriers were addressed by many programs through widening access initiatives in student recruitment, relevant to each program’s context.

Community engagement

Community engagement is a feature of social accountability that involves authentic interdependent partnerships between health services and academic institutions, respects the knowledge and experience of rural communities and gives them a voice in the selection and training of students (179, 180). This was evident through rural communities being given agency in student selection, with their level of involvement varying from responsibility for nominating students for consideration for program entry (62, 103), to more collaborative involvement as stakeholder representatives on admissions committees (20, 44). Rural communities were also engaged in student training through distributed educational models, often through the provision of clinical supervision. Community engagement was further evident through pre-entry recruitment programs, for example, partnerships with local rural high schools (92, 94, 96).

In terms of program outcomes for communities, measures such as economic impact and healthcare access were reported by a small number of programs. However, there was limited investigation of the broader experiences of communities in which programs were based. This is an important area for future evaluation, given the central role of the community in PBE. Sustainable rural pre-registration HPE programs require collaborative, symbiotic partnerships with health services and communities that enable mutual benefit (181, 182). Evaluation of program outcomes with this focus would recognize the investment of rural communities and provide examples of best practice in this field.

Limitations

As data for this review were extracted from the peer-reviewed literature only, there may be other place-based pre-registration HPE programs that have not been included. Database search terms were designed to capture a range of terminology and concepts that may be used to describe place-based approaches, however the primary usage of PBE terminology in Western countries may mean that alternative terms used to describe programs adopting similar approaches may not have been captured. A further limitation of this study, with its focus on program design, was the absence of data extraction on rural/place focussed curriculum content and how this may contribute to building and reinforcing place connection. Overall, there was insufficient curricular detail to assess this important aspect of a place-based approach adequately. This knowledge gap could be addressed through a literature review on a narrower subset of place-based pre-registration HPE programs, to explore current practice in this area and how place-based curriculum is being incorporated.

The absence or heterogeneity of rural definitions and classification systems hindered comparisons and contextualisation of programs. This issue has been noted in previous systematic reviews on rural workforce outcomes (4, 5, 19, 77, 175). To assist with this, programs should consider providing a clear and specific description of their defined area of focus, as well as information on how rurality is classified in their region. Population density (persons/square km) was one strategy identified to compare international programs that may be helpful to consider as a unifying program statistic (75, 141).

Conclusion

Through the identification of common design features of place-based pre-registration HPE programs, this review provides a foundation and framework to guide the establishment and evaluation of similar programs. Key considerations for comprehensive place-based program design include: accurately defining the geographical scale of the program, developing a strategy for student recruitment from the target region focused on widening access, provision of continuity with rural communities through longitudinal training experiences, engaging communities in the design and delivery of the program, and the alignment of evaluation plans with the goals of the program and the communities served. There are rich opportunities for further research into each of these areas, to compare and contrast how place-based HPE programs are delivering on these outcomes through their program design.

Author contributions

LF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Visualization. JB: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. VV: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GR: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors acknowledge the Commonwealth of Australia's Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training funding that supports this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1546701/full#supplementary-material

References

1. World Health Organisation . WHO guideline on health workforce development, attraction, recruitment and retention in rural and remote areas: A summary. Geneva: WHO (2021).

2. World Health Organization . Retention of the health workforce in rural and remote areas: a systematic review Geneva. (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240013865

3. Onnis, L-A, and Hunter, T. Improving rural and remote health workforce retention amid global workforce shortages: a scoping review of evaluated workforce interventions. J Health Organ Manag. (2024) 39:260–79. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-03-2024-0077

4. Noya, F, Carr, S, Freeman, K, Thompson, S, Clifford, R, and Playford, D. Strategies to facilitate improved recruitment, development, and retention of the rural and remote medical workforce: a scoping review. Int J Health Policy Manag. (2022) 11:2022–37. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2021.160

5. Figueiredo, AM, Labry Lima, AO, Figueiredo, DCMM, Neto, AJM, Rocha, EMS, and Azevedo, GD. Educational strategies to reduce physician shortages in underserved areas: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:5983. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20115983

6. McGrail, MR, Doyle, Z, Fuller, L, Gupta, TS, Shires, L, and Walters, L. The pathway to more rural doctors: the role of universities. Med J Aust. (2023) 219:S8–S13. doi: 10.5694/mja2.52021

7. Elma, A, Nasser, M, Yang, L, Chang, I, Bakker, D, and Grierson, L. Medical education interventions influencing physician distribution into underserved communities: a scoping review. Hum Resour Health. (2022) 20:31. doi: 10.1186/s12960-022-00726-z

8. Patterson, F, Roberts, C, Hanson, MD, Hampe, W, Eva, K, Ponnamperuma, G, et al. 2018 Ottawa consensus statement: selection and recruitment to the healthcare professions. Med Teach. (2018) 40:1091–101. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1498589

9. Fox, J, Beattie, J, McGrail, J, Eley, D, Fuller, L, Hu, W, et al. Medical school admission processes to target rural applicants: an international scoping review and mapping of Australian practices. BMC Med Educ. (2025) 25:1–21. doi: 10.1186/s12909-025-07234-3

10. Walsh, S, Lyle, D, Thompson, S, Versace, V, Brown, L, Knight, S, et al. The role of national policies to address rural allied health, nursing and dentistry workforce maldistribution. Med J Aust. (2020) 213:S18–22. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50881

11. Commonwealth of Australia Department of Health and Aged Care . Rural health multidisciplinary training (RHMT) program framework (2019-20). (2021). Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/10/rural-health-multidisciplinary-training-rhmt-program-framework-2019-2020-rural-health-multidisciplinary-training-rhmt-program-framework-2019-2020.pdf

12. Cosgrave, C, Malatzky, C, and Gillespie, J. Social determinants of rural health workforce retention: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:314. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16030314

13. Australian Government Department of Health . National medical workforce strategy 2021-2031. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/national-medical-workforce-strategy-2021-2031#:~:text=The%20strategy%20aims%20to%20address%20medical%20workforce%20issues,5%20building%20a%20flexible%20and%20responsive%20medical%20workforce

14. Fuller, L, Beattie, J, and Versace, V. Graduate rural work outcomes of the first 8 years of a medical school: what can we learn about student selection and clinical school training pathways? Aust J Rural Health. (2021) 29:181–90. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12742

15. McGirr, J, Seal, A, Barnard, A, Cheek, C, Garne, D, Greenhill, J, et al. The Australian rural clinical school (RCS) program supports rural medical workforce: evidence from a crosssectional study of 12 RCSs. Rural Remote Health. (2019) 19:4971. doi: 10.22605/RRH4971

16. Seal, AN, Playford, D, McGrail, MR, Fuller, L, Allen, PL, Burrows, JM, et al. Influence of rural clinical school experience and rural origin on practising in rural communities five and eight years after graduation. Med J Aust. (2022) 216:572–7. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51476

17. Playford, D, Larson, A, and Wheatland, B. Going country: rural student placement factors associated with future rural employment in nursing and allied health. Aust J Rural Health. (2006) 14:14–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2006.00745.x

18. O'Sullivan, B, McGrail, M, Russell, D, Walker, J, Chambers, H, Major, L, et al. Duration and setting of rural immersion during the medical degree relates to rural work outcomes. Med Educ. (2018) 52:803–15. doi: 10.1111/medu.13578

19. Rabinowitz, HK, Diamond, JJ, Markham, FW, and Wortman, JR. Medical school programs to increase the rural physician supply: a systematic review and projected impact of widespread replication. Acad Med. (2008) 83:235–43. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318163789b

20. Glasser, M, Hunsaker, M, Sweet, K, MacDowell, M, and Meurer, M. A comprehensive medical education program response to rural primary care needs. Acad Med. (2008) 83:952–61. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181850a02

21. Stearns, JA, Stearns, MA, Glasser, M, and Londo, RA. Illinois RMED: a comprehensive program to improve the supply of rural family physicians. Fam Med. (2000) 32:17–21.

22. Rourke, J . Social accountability in theory and practice. Ann Fam Med. (2006) 4:S45–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.559

23. Ventres, W, Boelen, C, and Haq, C. Time for action: key considerations for implementing social accountability in the education of health professionals. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. (2018) 23:853–62. doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9792-z

24. Boelen, C, and Woollard, B. Social accountability and accreditation: a new frontier for educational institutions. Med Educ. (2009) 43:887–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03413.x

25. Boelen, C, and Heck, JE. Defining and measuring the social accountability of medical schools. World Health Organization. (1995). Available at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/59441

26. McGrail, MR, and O'Sullivan, BG. Increasing doctors working in specific rural regions through selection from and training in the same region: national evidence from Australia. Hum Resour Health. (2021) 19:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12960-021-00678-w

27. Johnson, IM . A rural "grow your own" strategy: building providers from the local workforce. Nurs Adm Q. (2017) 41:346–52. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000259

28. Worley, P, Lowe, M, Notaras, L, Strasser, S, Kidd, M, Slee, M, et al. The Northern Territory medical program - growing our own in the NT. Rural Remote Health. (2019) 19:4671. doi: 10.22605/RRH4671

29. Ross, BM, Cameron, E, and Greenwood, D. Remote and rural placements occurring during early medical training as a multidimensional place-based medical education experience. Educ Res Rev. (2020) 15:150–8. doi: 10.5897/ERR2019.3873

30. Gruenewald, DA . Foundations of place: a multidisciplinary framework for place-conscious education. Am Educ Res J. (2003) 40:619–54. doi: 10.3102/00028312040003619

31. Gruenewald, DA . Accountability and collaboration: institutional barriers and strategic pathways for place-based education. Ethics Place Environ. (2005) 8:261–83. doi: 10.1080/13668790500348208

32. Yemini, M, Engel, L, and Ben Simon, A. Place-based education – a systematic review of literature. Educ Rev. (2025) 77:640–60. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2023.2177260

33. Arksey, H, and O'Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

34. Tricco, AC, Lillie, E, Zarin, W, O'Brien, KK, Colquhoun, H, Levac, D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

35. Metreau, E, Young, K, and Eapen, S. World Bank country classifications by income level for 2024-2025. (2024). Available online at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/world-bank-country-classifications-by-income-level-for-2024-2025

36. World Health Organisation . WHO regional offices 2024. Available online at: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/regional-offices.

37. Butler, L, Exner-Pirot, H, and Berry, L. Reshaping policies to achieve a strategic plan for indigenous engagement in nursing education. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont). (2018) 31:18–27. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2018.25476

38. Morris, T, Jones, CA, and Sehrawats, S. The pathway program: a collaboration between 3 universities to deliver a social work distance education (DL) program to underserved areas of California. Online J Distance Learn Adm. (2016) 19

39. Crump, WJ, Barnett, D, and Fricker, S. A sense of place: rural training at a regional medical school campus. J Rural Health. (2004) 20:80–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00011.x

40. Ozeki, S, Kasamo, S, Inoue, H, and Matsumoto, S. Does regional quota status affect the performance of undergraduate medical students in Japan? A 10-year analysis. Int J Med Educ. (2022) 13:307–14. doi: 10.5116/ijme.6372.1fce

41. Latham, H, Hamilton, M, Manners, J, and Anderson, J. An innovative model improving success at university for regional Australians suffering educational and social disadvantage. Rural Remote Health. (2009) 9:1128. doi: 10.22605/RRH1128

42. McDonnel Smedts, A, and Lowe, MP. Clinical training in the top end: impact of the Northern Territory clinical school, Australia, on the territory's health workforce. Rural Remote Health. (2007) 7:723. doi: 10.22605/RRH723

43. Philips, BU, Mahan, JM, and Kroshel, FT. Migration of allied health care personnel in and out of an underserved area: a question of roots. J Allied Health. (1978) 6:288–93.

44. Wheat, JR, Brandon, JE, Leeper, JD, Jackson, JR, and Boulware, DW. Rural health leaders pipeline, 1990-2005: case study of a second-generation rural medical education program. J Agromedicine. (2007) 12:51–61. doi: 10.1080/10599240801985951

45. Matsumoto, M, Takeuchi, K, Tanaka, J, Tazuma, S, Inoue, K, Owaki, T, et al. Follow-up study of the regional quota system of Japanese medical schools and prefecture scholarship programmes: a study protocol. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e011165. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011165

46. Kallail, K, and Anderson, MB. The scholars in primary care program: an assured admission program. Acad Med. (2001) 76:499. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00025

47. Mattsson, S, Gustafsson, M, Svahn, S, Norberg, H, and Gallego, G. Who enrols and graduates from web-based pharmacy education - experiences from northern Sweden. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. (2018) 10:1004–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2018.05.019

48. Magnus, JH, and Tollan, A. Rural doctor recruitment: does medical education in rural districts recruit doctors to rural areas? Med Educ. (1993) 27:250–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1993.tb00264.x

49. Woolley, T, Hogenbirk, JC, and Strasser, R. Retaining graduates of non-metropolitan medical schools for practice in the local area: the importance of locally based postgraduate training pathways in Australia and Canada. Rural Remote Health. (2020) 20:1–11. doi: 10.22605/RRH5835

50. Snadden, D, and Casiro, O. Maldistribution of physicians in BC: what we are trying to do about it. Br Columbia Med J. (2008) 50:371–2.

51. Kawamoto, R, Uemoto, A, Ninomiya, D, Hasegawa, Y, Ohtsuka, N, Kusunoki, T, et al. Characteristics of Japanese medical students associated with their intention for rural practice. Rural Remote Health. (2015) 15:3112. doi: 10.22605/RRH3112

52. Ouzts, KN, Brown, JW, and Diaz Swearingen, CA. Developing public health competence among RN-to-BSN students in a rural community. Public Health Nurs. (2006) 23:178–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.230209.x

53. Skorga, P . Interdisciplinary and distance education in the delta: the delta health education partnership. J Interprof Care. (2002) 16:149–57. doi: 10.1080/13561820220124166

54. Brandt, LC . From collaboration to cause: breaking rural poverty cycles through educational partnerships. Am J Occup Ther. (2014) 68:S45–50. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2014.685S01

55. Ostmoe, PM (1989). Establishment of an off-campus baccalaureate nursing program. Div. of Nursing., Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

56. Quinn, KJ, Kane, KY, Stevermer, JJ, Webb, WD, Porter, JL, Williamson, HAJr, et al. Influencing residency choice and practice location through a longitudinal rural pipeline program. Acad Med. (2011) 86:1397–406. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318230653f

57. Wheeler, DL, and Hackler, JB. Preparing physicians for rural-based primary care practice: a preliminary evaluation of rural training initiatives at OSU-COM. J Am Osteopath Assoc. (2017) 117:315–24. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2017.057

58. Rourke, J, Asghari, S, Hurley, O, Ravalia, M, Jong, M, Graham, W, et al. Does rural generalist focused medical school and family medicine training make a difference? Memorial University of Newfoundland outcomes. Rural Remote Health. (2018) 18:1–20. doi: 10.22605/RRH4426

59. Thind, A, Hewlett, ER, and Andersen, RM. The pipeline program at the Ohio State University College of dentistry: oral health improvement through outreach (OHIO) project. J Dent Educ. (2009) 73:S96–S106. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2009.73.2_suppl.tb04674.x

60. Somporn, P, Walters, L, and Ash, J. Expectations of rural community-based medical education: a case study from Thailand. Rural Remote Health. (2018) 18:1–11. doi: 10.22605/RRH4709

61. Stearns, JA, Glasseh, M, and Fulkerson, P. Medical student education: an admission and curricular approach to rural physician shortages. Acad Med. (1997) 72:438–9.

62. Paul, VK . Innovative programmes of medical education: I. Case studies. Indian J Pediatr. (1993) 60:759–68. doi: 10.1007/BF02751044

63. Couper, I, Worley, PS, and Strasser, R. Rural longitudinal integrated clerkships: lessons from two programs on different continents. Rural Remote Health. (2011) 11:1665. doi: 10.22605/RRH1665

64. Strasser, R . Social accountability and the supply of physicians for remote rural Canada. CMAJ. (2015) 187:791–2. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150266

65. Mian, O, Hogenbirk, JC, Warry, W, and Strasser, RP. How underserviced rural communities approach physician recruitment: changes following the opening of a socially accountable medical school in northern Ontario. Can J Rural Med. (2017) 22:139–47.

66. Tesson, G, Curran, V, Pong, R, and Strasser, R. Advances in rural medical education in three countries: Canada, the United States and Australia. Educ Health (Abingdon). (2005) 18:405–15. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.108732

67. Chadwick, DG, and Hupp, JR. East Carolina University School of dentistry: impact on access disparities. J Am Coll Dent. (2008) 75:35–41.

68. Joiner, CL Alabama linkage: an innovative higher education consortium maximizing statewide resources Shelton State Community Coll., Tuscaloosa, AL: Alabama Univ., Birmingham. School of Health Related Professions. (1992).

69. Snadden, D, and Bates, J. Breaking new ground in northern British Columbia. Clin Teach. (2007) 4:116–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2007.00137.x

70. Eidson-Ton, WS, Rainwater, J, Hilty, D, Henderson, S, Hancock, C, Nation, CL, et al. Training medical students for rural, underserved areas: a rural medical education program in California. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2016) 27:1674–88. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0155

71. Kataoka, Y, Takayashiki, A, Sato, M, and Maeno, T. Motives and factors associated with staying in medically underserved areas after the obligatory practice period among first-year Japanese medical students in a special quota system. Rural Remote Health. (2015) 15:3663. doi: 10.22605/RRH3663

72. Kataoka, Y, Takayashiki, A, Sato, M, and Maeno, T. Japanese regional-quota medical students in their final year are less motivated to work in medically underserved areas than they were in their first year: a prospective observational study. Rural Remote Health. (2018) 18:4840. doi: 10.22605/RRH4840

73. Kallail, KJ, and McCurdy, S. Scholars in rural health: outcomes from an assured admissions program. Fam Med. (2010) 42:729–31.

74. Rabinowitz, HK The effects of a selective medical school admissions policy on increasing the number of family physicians in rural and physician shortage areas. Research in medical education: proceedings of the annual conference on research in medical education (1987) 26 157–162

75. Johnston, K, Guingona, M, Elsanousi, S, Mbokazi, J, Labarda, C, Cristobal, FL, et al. Training a fit-for-purpose rural health workforce for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): how do drivers and enablers of rural practice intention differ between learners from LMICs and high income countries? Front Public Health. (2020) 8:582464. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.582464

76. Reeve, C, Woolley, T, Ross, SJ, Mohammadi, L, Halili, SB, Cristobal, F, et al. The impact of socially-accountable health professional education: a systematic review of the literature. Med Teach. (2017) 39:67–73. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1231914

77. Geyman, JP, Hart, LG, Norris, TE, Coombs, JB, and Lishner, DM. Educating generalist physicians for rural practice: how are we doing? J Rural Health. (2000) 16:56–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00436.x

78. Woolley, T, Larkins, S, and Gupta, TS. Career choices of the first seven cohorts of JCU MBBS graduates: producing generalists for regional, rural and remote northern Australia. Rural Remote Health. (2019) 19:31–40. doi: 10.22605/RRH4438

79. Hogenbirk, JC, Strasser, RP, and French, MG. Ten years of graduates: a cross-sectional study of the practice location of doctors trained at a socially accountable medical school. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0274499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274499

80. Hogenbirk, JC, Robinson, DR, and Strasser, RP. Distributed education enables distributed economic impact: the economic contribution of the northern Ontario School of Medicine to communities in Canada. Health Econ Rev. (2021) 11:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13561-021-00317-z

81. Schauer, A, Woolley, T, and Sen Gupta, T. Factors driving James Cook University bachelor of medicine, bachelor of surgery graduates' choice of internship location and beyond. Aust J Rural Health. (2014) 22:56–62. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12080

82. Daellenbach, R, Kensington, M, Maki, K, Prier, M, and Welfare, M. A networked distributed model for midwifery education. Professional and practice-based learning. 34. Springer, Cham: Springer Science and Business Media B.V. (2022). p. 335–354.

83. Hudson, GL, and Maar, M. Faculty analysis of distributed medical education in northern Canadian aboriginal communities. Rural Remote Health. (2014) 14:2664. doi: 10.22605/RRH2664

84. Woolley, T, Sen Gupta, T, and Murray, R. James Cook University’s decentralised medical training model: an important part of the rural workforce pipeline in northern Australia. Rural Remote Health. (2016) 16:1–11. doi: 10.22605/RRH3611

85. Norbye, B, and Skaalvik, MW. Decentralized nursing education in northern Norway: towards a sustainable recruitment and retention model in rural Arctic healthcare services. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2013) 72:22793. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.22793

86. Eriksen, LT, and Huemer, JE. The contribution of decentralised nursing education to social responsibility in rural Arctic Norway. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2019) 78:1691706. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2019.1691706

87. Hsueh, W, Wilkinson, T, and Bills, J. What evidence-based undergraduate interventions promote rural health? N Z Med J. (2004) 117:U1117.

88. Strasser, R, and Lanphear, J. The northern Ontario School of Medicine: responding to the needs of the people and communities of northern Ontario. Educ Health (Abingdon). (2008) 21:212. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.101547

89. Hawkins, JE, Wiles, LL, Karlowicz, K, and Tufts, KA. Educational model to increase the number and diversity of RN to BSN graduates from a resource-limited rural community. Nurse Educ. (2018) 43:206–9. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000460

90. Griffith, CH3rd, de Beer, F, Edwards, RL, Smith, C, Colvin, G, and Karpf, M. Addressing Kentucky's physician shortage while securing a network for a research-intensive, referral academic medical center: where public policy meets effective clinical strategic planning. Acad Med. (2021) 96:375–80. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003582

91. Hedrick, JS . “The Appalachian Medical Student Experience: A Case Study.” Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. West Virginia University. (2021). 10155. doi: 10.33915/etd.10155

92. Arora, R, Chamnan, P, Nitiapinyasakul, A, and Lertsukprasert, S. Retention of doctors in rural health services in Thailand: impact of a national collaborative approach. Rural Remote Health. (2017) 17:4344. doi: 10.22605/RRH4344

93. Cristobal, F, and Worley, P. Can medical education in poor rural areas be cost-effective and sustainable: the case of the Ateneo de Zamboanga University School of Medicine. Rural Remote Health. (2012) 12:1835. doi: 10.22605/RRH1835

94. Matsumoto, M, Inoue, K, and Kajii, E. Characteristics of medical students with rural origin: implications for selective admission policies. Health Policy. (2008) 87:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.12.006

95. Sen Gupta, T, Woolley, T, Murray, R, Hays, R, and McCloskey, T. Positive impacts on rural and regional workforce from the first seven cohorts of James Cook University medical graduates. Rural Remote Health. (2014) 14:1–13. doi: 10.22605/RRH2657

96. Techakehakij, W, and Arora, R. From one-district-one-doctor to the inclusive track: lessons learned from a 12-year special recruitment program for medical education in Thailand. Educ Health (Abingdon). (2019) 32:122–6. doi: 10.4103/efh.EfH_139_18

97. Soliman, SR, Macdowell, M, Schriever, AE, Glasser, M, and Schoen, MD. An interprofessional rural health education program. Am J Pharm Educ. (2012) 76:199. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7610199

98. Bates, J, Frinton, V, and Voaklander, D. A new evaluation tool for admissions. Med Educ. (2005) 39:1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02308.x

99. Rourke, J, Asghari, S, Hurley, O, Ravalia, M, Jong, M, Parsons, W, et al. From pipelines to pathways: the Memorial experience in educating doctors for rural generalist practice. Rural Remote Health. (2018) 18:1–12. doi: 10.22605/RRH4427

100. Larkins, S, Michielsen, K, Iputo, J, Elsanousi, S, Mammen, M, Graves, L, et al. Impact of selection strategies on representation of underserved populations and intention to practise: international findings. Med Educ. (2015) 49:60–72. doi: 10.1111/medu.12518

101. Brazeau, NK, Potts, MJ, and Hickner, JM. The upper peninsula program: a successful model for increasing primary care physicians in rural areas. Fam Med. (1990) 22:350–5.

102. Kardonsky, K, Evans, DV, Erickson, J, and Kost, A. Impact of a targeted rural and underserved track on medical student match into family medicine and other needed workforce specialties. Fam Med. (2021) 53:111–7. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.351484

103. Siega-Sur, JL, Woolley, T, Ross, SJ, Reeve, C, and Neusy, AJ. The impact of socially-accountable, community-engaged medical education on graduates in the Central Philippines: implications for the global rural medical workforce. Med Teach. (2017) 39:1084–91. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1354126

104. Roberts, A, Foster, R, Dennis, M, Davis, L, Wells, J, Bodemuller, MF, et al. An approach to training and retaining primary care physicians in rural Appalachia. Acad Med. (1993) 68:122–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199302000-00003

106. Rourke, J, O'Keefe, D, Ravalia, M, Moffatt, S, Parsons, W, Duggan, N, et al. Pathways to rural family practice at Memorial University of Newfoundland. Can Fam Physician. (2018) 64:e115–e25.

107. Putthasri, W, Suphanchaimat, R, Topothai, T, Wisaijohn, T, Thammatacharee, N, and Tangcharoensathien, V. Thailand special recruitment track of medical students: a series of annual cross-sectional surveys on the new graduates between 2010 and 2012. Hum Resour Health. (2013) 11:47. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-47

108. Hogenbirk, JC, French, MG, Timony, PE, Strasser, RP, Hunt, D, and Pong, RW. Outcomes of the Northern Ontario School of Medicine's distributed medical education programmes: protocol for a longitudinal comparative multicohort study. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e008246. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008246

109. Hays, R . Rural initiatives at the James Cook University School of Medicine: a vertically integrated regional/rural/remote medical education provider. Aust J Rural Health. (2001) 9:2–S5. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1584.9.s1.10.x

110. Keyes-Welch, M, and Martin, D Generalist physician initiatives in U.S. medical schools. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges. (1993).

111. Curran, VR, Fleet, L, Pong, RW, Bornstein, S, Jong, M, Strasser, RP, et al. A survey of rural medical education strategies throughout the medical education continuum in Canada. Cah Sociol Demogr Med. (2007) 47:445–68.

112. Strasser, RP, Lanphear, JH, McCready, WG, Topps, MH, Hunt, DD, and Matte, MC. Canada's new medical school: the Northern Ontario school of medicine: social accountability through distributed community engaged learning. Acad Med. (2009) 84:1459–64. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6c5d7

113. Strasser, R, and Neusy, A. Context counts: training health workers in and for rural and remote areas. Bull World Health Organ. (2010) 88:777–82. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.072462

114. Hays, R, Stokes, J, and Veitch, J. A new socially responsible medical school for regional Australia. Educ Health (Abingdon). (2003) 16:14–21. doi: 10.1080/1357628031000066613

115. Sandlin, BM . Bureau of health professions program resource guide. Kansas City, MO: National Rural Health Association (1994).

116. Woolley, T, Ross, S, Larkins, S, Sen Gupta, T, and Whaleboat, D. "We learnt it, then we lived it": influencing medical students' intentions toward rural practice and generalist careers via a socially-accountable curriculum. Med Teach. (2021) 43:93–100. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1817879