- Affiliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Jinhua, Zhejiang, China

Background: This meta-analysis investigates the relationship between smoking and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) risk.

Methods: Observational studies (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional) were systematically searched in PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCO, and Cochrane Library up to December 2024. Adjusted odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were used to assess the association.

Results: A total of 19 studies, composing 450,130 participants were included. Active smoking significantly increased NAFLD risk (OR = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.21–1.40, p < 0.001), with stronger effects observed in current smokers (OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.22–1.63, p < 0.001). A dose-response relationship was evident: ≥20 pack-years of smoking elevated risk by 32% (OR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.18–1.49, p < 0.001). Subgroup analyses revealed amplified risks in metabolically compromised individuals, including those with BMI ≥ 24 (OR = 1.43, p < 0.001), TG ≥ 1.2 mmol/L (OR = 1.41, p = 0.003), and SBP ≥ 125 mmHg (OR = 1.65, p < 0.001). Passive smoking showed a marginal association (OR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.09–1.16, p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Smoking is an independent risk factor for NAFLD, particularly in individuals with metabolic dysregulation. Public health strategies targeting smoking cessation and metabolic control may mitigate NAFLD burden.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#loginpage, identifier CRD42024545970

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is one of the most prevalent chronic liver diseases, with an estimated global prevalence of 25% (1). It poses significant health risks, increasing the incidence of metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular events (2). The all-cause mortality rate of NAFLD patients is significantly higher than that of the general population, mainly due to cardiovascular diseases and extrahepatic malignancies (3). Moreover, NAFLD has also been linked to a higher risk of osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, colorectal cancer, and breast cancer (4, 5). Prevention strategies for NAFLD include maintaining a healthy lifestyle, such as a balanced diet, regular exercise, and weight control, as well as managing underlying metabolic disorders like obesity, hypertension, and diabetes (6, 7).

Several common risk factors contribute to the development of NAFLD, including obesity, insulin resistance, and a sedentary lifestyle (8). Among these, smoking has emerged as a potential risk factor. Smoking may exacerbate the severity of NAFLD through mechanisms such as inducing oxidative stress, promoting hepatocyte apoptosis, and stimulating the extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway (9–11). It has been suggested that smoking can increase the risk of NAFLD, with a dose-response relationship observed between the amount of smoking and the risk of developing the disease (12). Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that the association between smoking and NAFLD may be modified by metabolic factors, such as obesity or insulin resistance, indicating a potential synergistic effect that warrants further investigation. However, the exact role of smoking in the development and progression of NAFLD remains a subject of debate.

Numerous studies have investigated the impact of smoking on NAFLD, yielding conflicting results. Firstly, some studies such as Yun Seo Jang et al. (13) and Ayaka Hamabe et al. (14) did not observe a link between smoking and NAFLD risk. Secondly, subgroup analyses of smoking frequency, duration of quitting smoking, and other factors in different studies show a high degree of inconsistency. For example, Ayaka Hamabe et al. (14) believe that smoking <10 pack years increases the risk of NAFLD, but Peiyi Liu et al. (15) believe that smoking <10 pack years does not increase the risk of NAFLD. These discrepancies may arise from variations in study design, population characteristics, adjustments for confounding factors, or differences in NAFLD diagnostic criteria. Given the conflicting evidence in existing literature, this study aims to systematically review and meta-analyze observational studies assessing the association between smoking and NAFLD. The goal is to provide robust evidence for smoking-related NAFLD risk and inform prevention strategies in healthy populations.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

In the electronic databases of PubMed, Web of science, EBSCO and the Cochrane Library, a comprehensive literature search was performed by retrieving the keywords “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” and “smoking” until December 2024. The complete retrieval formula that was used to identify the related studies includes: (“non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” OR “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” OR “NAFLD” OR “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” OR “non-alcoholic fatty liver” OR “non-alcoholic fatty livers” OR “non-alcoholic steatohepatitis” OR “non-alcoholic steatohepatitides”) AND (“smoking” OR “tobacco smoke pollution” OR “tobacco use” OR “tobacco products” OR “active smoking” OR “passive smoking” OR “secondhand smoking” OR “tobacco”). Retrieved studies and recently reviewed reference lists were also reviewed for potentially inclusive studies. In cases of duplicate publication, the original article is included if the study is published as an abstract and an original article. Also, if several articles were published for research, only the latest or highest quality articles were included. This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines (16). The population, intervention/exposure, comparison, outcome, and setting (PICOS) criteria were used to describe the research question. The Prospero registration number of this meta-analysis was CRD42024545970.

Selection criteria

An eligible criterion had been formulated. The specific criteria were as follows: inclusion criteria: (1) all included studies are observational studies (include prospective or retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies). (2) The main exposure of study was smoking including active and passive smoking, and the outcome was NAFLD risk. (3) The article must report extractable risk estimates (e.g., RR, HR, OR) along with their 95% confidence intervals, or provide raw data sufficient to calculate these estimates. Exclusion criteria: (1) the study was conducted on NAFLD population. (2) The study was published in duplicate. (3) The study was not published in English. (4) The study was case reports, case series, reviews, editorials, conference abstracts (without full data), and animal or in vitro studies.

Two authors independently applied a search strategy to select studies from the database and independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of these articles to determine eligibility for inclusion. When in doubt, the full text will be searched for further selection. When necessary, the authors were contacted for more information about their research. In case of disagreement, discussions were conducted with the third author. When consensus could not be reached, the study was excluded.

Data collection and quality assessment

A jointly agreed data collection form was used to extract all data. Information was extracted as follows: the author’s name, year of publication, study type, age, exposure assessment, number of participants, number of NAFLD cases, number of smokers, number of non-smokers, variables adjusted in the statistical analyses, and outcomes. To ensure the objectivity and accuracy of the data, two researchers independently extracted data from each study. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or consultation with a third author.

The quality of each cohort and case-control study was evaluated by the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) checklist, a tool used for quality assessment of non-randomized studies. NOS checklist is composed of eight items classified into three aspects, including selection, comparability, and outcome. The maximum scores of this checklist were nine, and scores between seven and nine were identified to higher study quality. The cross-sectional studies were assessed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Recommended Standard List. Risk of bias was assessed as “low risk,” “high risk” or “unclear risk.” To ensure the reliability and standardization of the quality assessment, the evaluation was also independently performed by two researchers. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third researcher.

Objectives and endpoints

The primary objective is to explore the relationship between smoking and the incidence of NAFLD. The secondary objective was to explore the relationship between the incidence of NAFLD and the smoking subgroup, such as smoking duration, smoking intensity, pack-years smoked and other metabolic indicators. The results after adjusting for relevant confounding factors were uniformly adopted for the processing of relevant data from the included articles.

Data analysis

The Stata software version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) was used to analyze the data. The confidence interval (CI) of odds ratio (OR) was set at 95% to examine the relationship between smoking and BC risk. Heterogeneity of included studies was tested by Q statistic and I2 statistic to quantitatively assess inconsistency. For statistical results, values of p < 0.10 and I2 > 50% were representative of statistically significant heterogeneity. To increase the credibility of the results, random effect model was uniformly adopted in this study. When more than ten studies were included, sensitivity analysis and publication bias test were performed to evaluate the stability and reliability of the results. Publication bias was evaluated by the Begg’s test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study characteristics

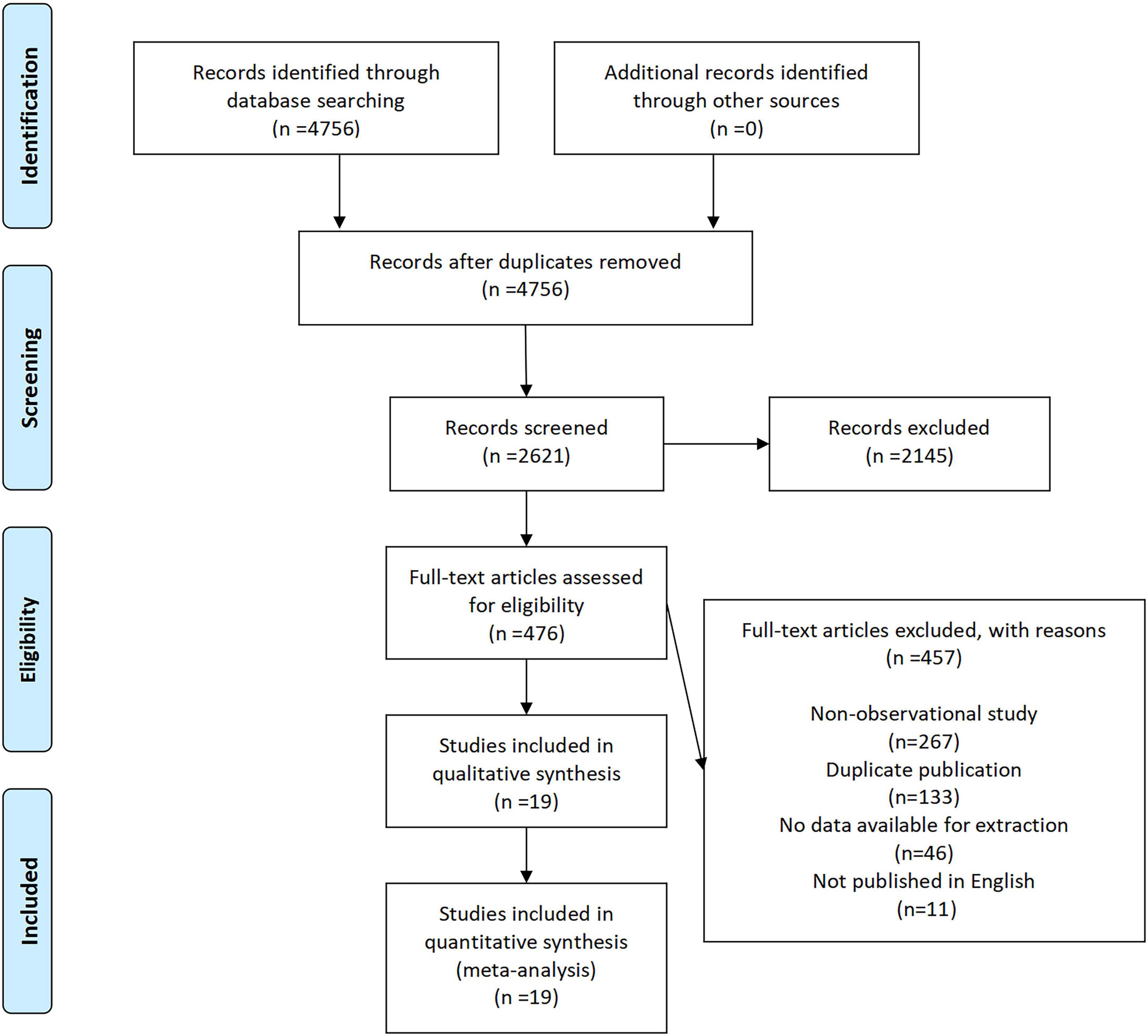

A total of 4,756 records were initially identified through database searching, with no additional records obtained from other sources (Figure 1). After removing duplicates, 2,621 records remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 2,145 records were excluded due to irrelevance. The full texts of 476 articles were assessed for eligibility, among which 457 were excluded for the following reasons: non-observational study (n = 219), duplicate publication (n = 130), no data available for extraction (n = 96), and not published in English (n = 11). Ultimately, 19 studies (10 cohort, 8 cross-sectional, 1 case-control) spanning Asia, Europe, and South America met the inclusion criteria and were included in the quantitative synthesis (Supplementary Table 1). Cohort and case-control studies demonstrated high quality (Cohort studies: mean NOS = 7.9; case-control study: NOS = 9; Supplementary Tables 2, 3), while cross-sectional studies were assessed on AHRQ criteria (Supplementary Table 4). According to the quality evaluation results of the investigators, all included studies were of high quality.

Quality appraisal of included studies

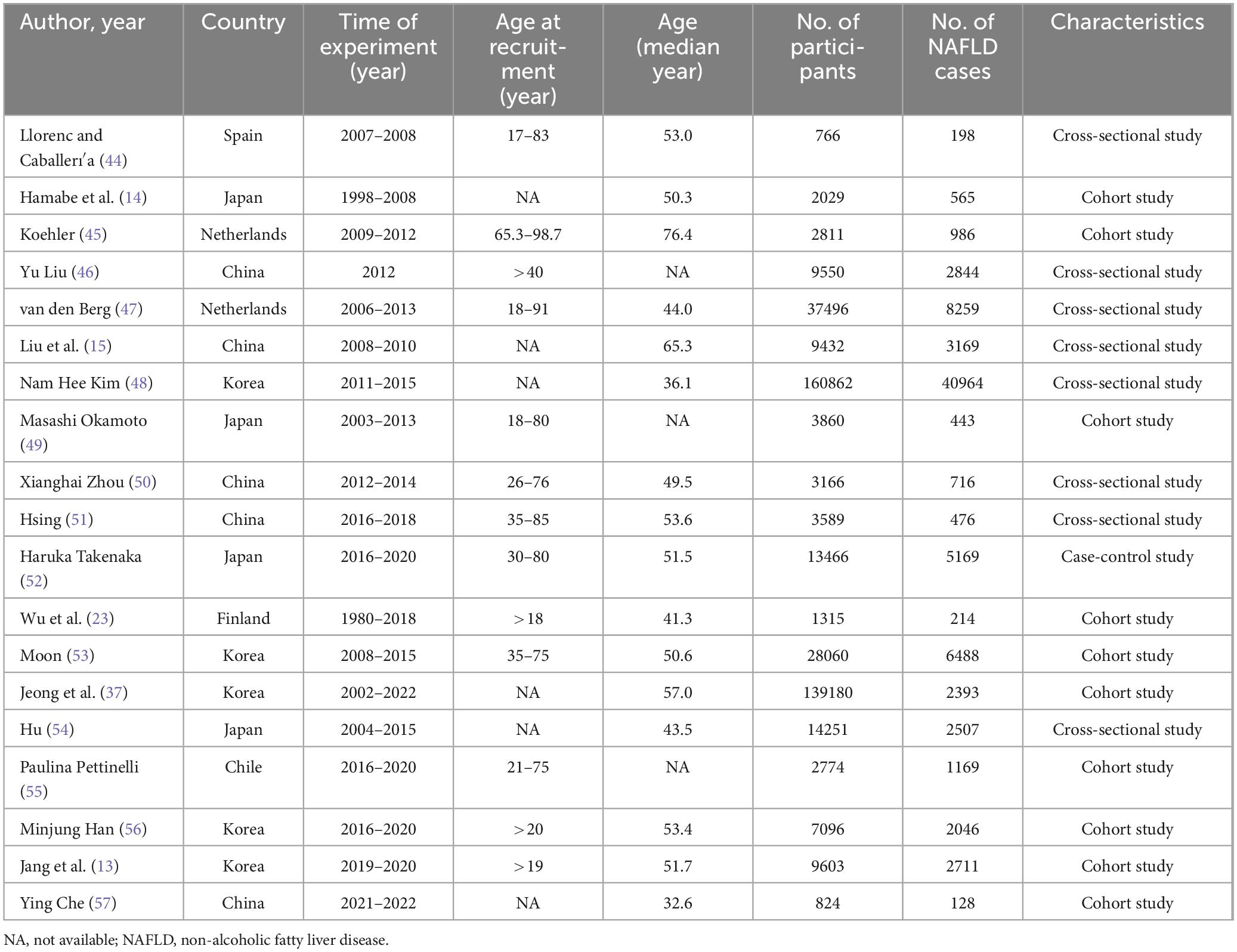

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. These studies were conducted across seven countries, encompassing 450,130 participants and 81,445 cases of NAFLD, with participant recruitment periods ranging from 1980 to 2022. Among the studies, 10 were cohort studies, 8 were cross-sectional studies, and 1 was a case-control study. The median age at recruitment ranged from 32.6 to 76.4 years, with most studies involving adults aged over 40 years.

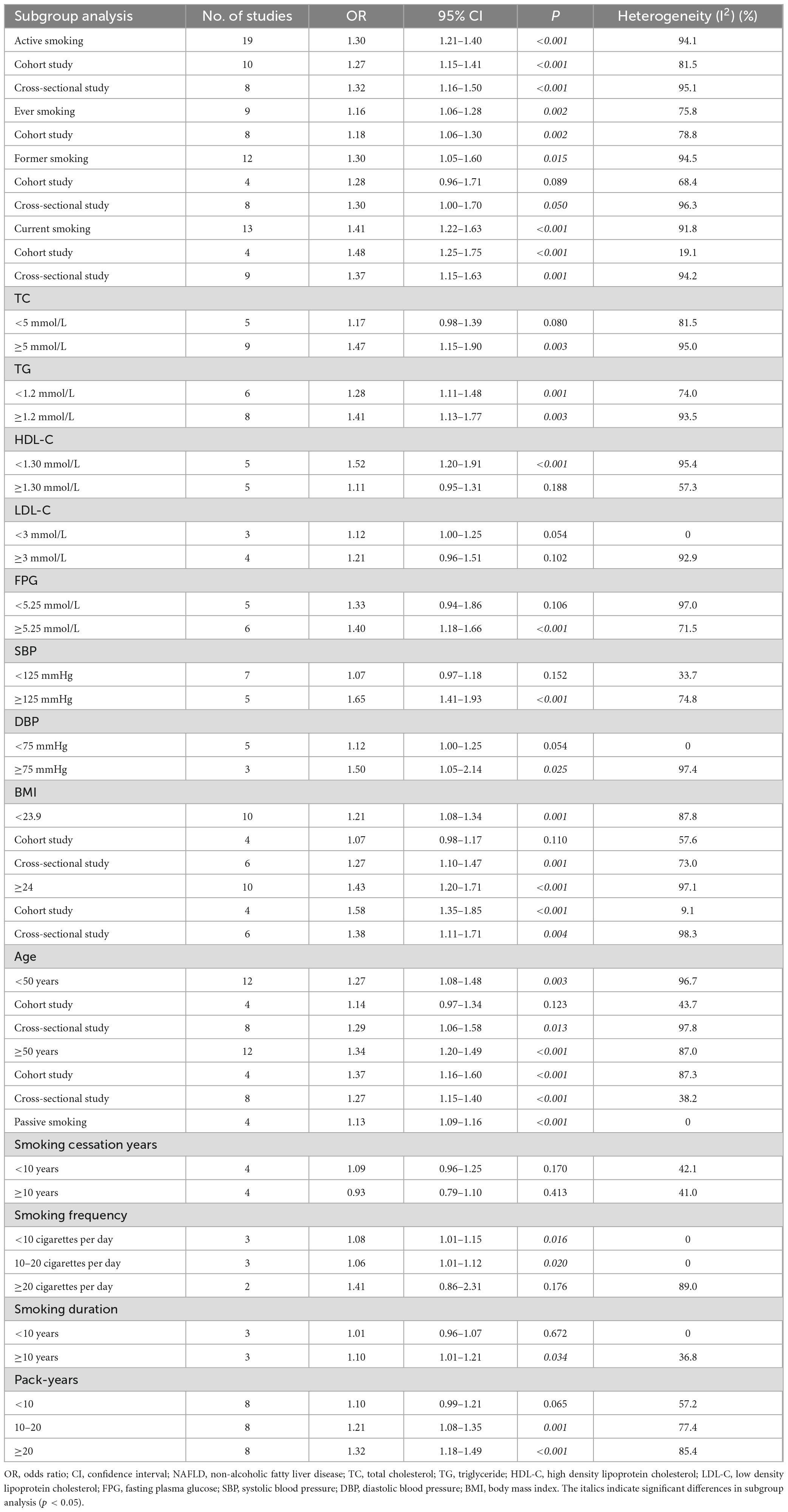

Smoking status and NAFLD

The pooled analysis demonstrated that active smoking was significantly associated with increased risk of NAFLD (OR = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.21–1.40, p < 0.001), with substantial heterogeneity observed (I2 = 94.1%). Subgroup analysis by study design revealed consistent findings: both cohort studies (OR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.15–1.41, p < 0.001) and cross-sectional studies (OR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.16–1.50, p < 0.001) supported this association (Table 2).

Regarding smoking history, ever smokers had a moderately elevated NAFLD risk (OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.06–1.28, p = 0.002), while former smokers also showed an increased risk (OR = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.05–1.60, p = 0.015). Notably, current smoking was more strongly associated with NAFLD (OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.22–1.63, p < 0.001), particularly in cohort studies (OR = 1.48, 95% CI: 1.25–1.75, p < 0.001), where heterogeneity was low (I2 = 19.1%) (Table 2).

Subgroups analysis

Stratified analyses by metabolic indicators further demonstrated that the effect of smoking was more pronounced among individuals with elevated total cholesterol (≥5 mmol/L, OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.15–1.90, p = 0.003), triglycerides (≥1.2 mmol/L, OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.13–1.77, p = 0.003), or lower HDL-C (<1.30 mmol/L, OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.20–1.91, p < 0.001). Similar patterns were observed in participants with higher fasting plasma glucose (≥5.25 mmol/L, OR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.18–1.66, p < 0.001) and elevated systolic blood pressure (≥125 mmHg, OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.41–1.93, p < 0.001) or diastolic blood pressure (≥75 mmHg, OR = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.05–2.14, p = 0.025) (Table 2).

Body mass index (BMI) significantly modified the association: among participants with BMI ≥ 24, the association was stronger (OR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.20–1.71, p < 0.001) compared to those with BMI < 23.9 (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.08–1.34, p = 0.001). The trend was more robust in cohort studies with high BMI (OR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.35–1.85, p < 0.001) compared to those with low BMI (OR = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.98–1.17, p = 0.110) (Table 2).

In age subgroup analysis, older adults demonstrated a significant association (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.20–1.49, p < 0.001), consistent across study designs (cohort study: OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.16–1.60, p < 0.001; cross-sectional study: OR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.15–1.40, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Dose-response and passive exposure

A dose-response relationship between smoking and NAFLD was evident. Smoking ≥ 20 cigarettes per day was associated with a higher risk (OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.86–2.31, p = 0.176) compared to those with low smoking frequency (<10 cigarettes per day: OR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.01–1.15, p = 0.016; 10–20 cigarettes per day: OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.01–1.12, p = 0.020), though with wide confidence intervals, indicating heterogeneity (I2 = 89.0%). Longer smoking duration (≥10 years) also conferred increased risk (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.01–1.21, p = 0.034), while shorter duration showed no significant association. A similar trend was observed for pack-years, with stronger associations observed in participants with ≥20 pack-years (OR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.18–1.49, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

In contrast, passive smoking was associated with a modest but statistically significant increase in NAFLD risk (OR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.09–1.16, p < 0.001), with no observed heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), suggesting a consistent effect across studies (Table 2).

Moreover, the impact of smoking cessation varied by time since quitting. Those who had quit for less than 10 years still exhibited a non-significant increase in risk (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.96–1.25, p = 0.170), while the risk was attenuated after ≥10 years of cessation (OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.79–1.10, p = 0.413) (Table 2).

Discussion

This meta-analysis synthesizes findings from 19 observational studies, encompassing over 400,000 participants across multiple countries, to systematically evaluate the association between smoking and the risk of developing NAFLD. The pooled analysis demonstrated a significantly elevated risk of NAFLD among smokers, with current smokers exhibiting a higher risk compared to former and ever smokers. We specifically incorporated and stratified analyses by metabolic status (e.g., obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia), allowing identification of high-risk subgroups and clarifying effect modification by metabolic health. These findings suggest that smoking may represent a critical modifiable risk factor for NAFLD.

Active smokers exhibited a significantly elevated risk of NAFLD, with this association remaining consistent across various study designs, including both cohort and cross-sectional analyses. Notably, both former and current smoking, as well as passive smoking, demonstrated significant correlations with NAFLD, suggesting persistent and potentially cumulative detrimental effects of tobacco exposure on hepatic function that may extend even years beyond smoking cessation (17). This is consistent with existing evidence indicating that the metabolic and inflammatory sequelae of tobacco use can persist over time, contributing to long-term hepatic steatosis and fibrosis. Stratified analyses further revealed that current smokers faced the highest NAFLD risk, implying that sustained and active exposure to cigarette smoke may exert more pronounced pathogenic effects, potentially via mechanisms such as oxidative stress, insulin resistance, lipid metabolism dysregulation, and pro-inflammatory cytokine activation (12, 18–21). The observed dose–response relationship, characterized by increasing NAFLD risk with longer duration and higher cumulative exposure to smoking, further supports a positive association between tobacco use and hepatic fat accumulation (22).

Importantly, passive smoking was also associated with a significantly increased risk of NAFLD, indicating that involuntary chronic exposure to environmental tobacco smoke may be sufficient to induce metabolic alterations and hepatocellular injury in non-smokers (23). Although the observed pooled effect size for the association between passive smoking and NAFLD incidence may appear modest at the individual level, its public health implications could be substantial. Given the vast number of individuals exposed to secondhand smoke worldwide, even a small increase in relative risk translates to a significant population attributable risk, suggesting that a considerable number of NAFLD cases could be potentially prevented through public health interventions aimed at reducing secondhand smoke exposure. This highlights the broader public health implications of secondhand smoke and underscores the need to address environmental exposure in NAFLD prevention strategies. The observed gradient of NAFLD risk–from highest in current smokers, intermediate in former smokers, and elevated in passive smokers compared to never-smokers–reinforces the importance of both primary and secondary prevention efforts (24). These findings emphasize the necessity of incorporating structured smoking cessation programs into NAFLD clinical management pathways and support the broader implementation of population-level tobacco-control policies to mitigate exposure in both private and public settings. Future studies should aim to elucidate the mechanistic pathways linking tobacco exposure to NAFLD progression and explore the reversibility of hepatic changes following smoking cessation (25, 26).

This study found that individuals who have been quitting smoking for at least 10 years have a significantly lower risk of developing NAFLD compared to current smokers. The mainstream views currently recognized by researchers are as follows: firstly, quitting smoking can alleviate oxidative stress and inflammation caused by tobacco smoke. Nicotine, tar, free radicals, and other substances in tobacco smoke are powerful pro-oxidants and pro-inflammatory agents (27). They directly reach the liver through the portal vein system or indirectly affect the liver by triggering systemic low-grade inflammation, exacerbating oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions in liver cells, which is the core link in the occurrence and development of NAFLD (28). After long-term smoking cessation, the body is freed from continuous exposure to exogenous toxins, and the antioxidant defense system (such as glutathione levels) in the body is restored. The levels of systemic inflammatory markers (such as C-reactive protein, TNF-α, IL-6) continue to decrease, creating a healthier metabolic environment for the liver (29). The second is to regulate the gut microbiota and gut liver axis (30). Studies have shown that smoking can alter the structure and function of the gut microbiota (dysbiosis), increase intestinal permeability, and lead to the translocation of endotoxins (such as lipopolysaccharides) to the portal vein. lipopolysaccharides exacerbate liver inflammation by activating immune cells in the liver (31). Long term smoking cessation can help restore the gut microbiota ecology and repair the intestinal barrier function, reducing the sustained attack on the liver (32). The third is to improve insulin resistance, restore insulin sensitivity, correct lipid metabolism, and reduce liver fat accumulation (33). The reversal of the above mechanism requires a long-term process, which may explain why it takes more than 10 years of continuous smoking cessation to observe a significant reduction in NAFLD risk, reflecting the time required for deep body repair. This evidence greatly enhances the scientific persuasiveness of smoking cessation initiatives. We suggest that future clinical guidelines and public health policies should fully consider reducing the risk of NAFLD as an important benefit in encouraging long-term smoking cessation and integrate it into patient education and public health information, in order to more effectively promote the overall liver health and overall health level of the population.

This study is the first to conduct comprehensive stratified analyses across subgroups defined by metabolic parameters such as blood pressure, BMI, and age, thereby providing novel insights into the interaction between smoking and metabolic health in the context of NAFLD (34–38). Notably, the magnitude of association between smoking and NAFLD was consistently more pronounced in these high-risk metabolic subgroups, implying that tobacco exposure may act synergistically with underlying metabolic dysregulation to accelerate hepatic steatosis and disease progression. This is biologically plausible, as smoking is known to impair lipid metabolism, exacerbate insulin resistance (38), and trigger systemic oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways (39) –all of which are established contributors to NAFLD pathogenesis. Particularly, populations with already compromised metabolic profiles, smoking may further destabilize hepatic lipid homeostasis, increase hepatic fat deposition, and heighten susceptibility to hepatocellular injury and fibrosis (40).

Although we adjusted for known confounding factors through a multivariate model, the possibility of residual confounding, such as confounding from measurement errors in diet, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and smoking, still exists. Especially, there is a high correlation between smoking and drinking behavior, which may partially contribute to the observed association. However, our sensitivity analysis indicates that a significant unmeasured confounding factor with a significant effect value is required to fully explain the current major findings, which reduces the likelihood of residual confounding leading to false positives. Therefore, although we interpret these findings cautiously, we believe that the observed associations are more likely to reflect the true effects rather than being solely due to confounding factors.

These findings underscore the importance of considering metabolic status when evaluating the hepatic impact of smoking and underscore the necessity for tailored preventive strategies in metabolically vulnerable populations (41). Public health interventions targeting smoking cessation may be particularly beneficial for individuals with existing cardiometabolic abnormalities, where the additive or synergistic effects of smoking may significantly increase the burden of liver disease (41, 42). Future mechanistic and longitudinal studies are warranted to further delineate these interactions and assess whether risk attenuation is achievable following cessation in these high-risk groups.

Given the marked increase in NAFLD risk associated with both active and passive smoking–particularly among people with obesity, dyslipidemia, or hypertension–smoking history should be routinely assessed in metabolically at-risk populations. Smoking cessation interventions should be incorporated into comprehensive NAFLD prevention and management protocols. At the public health level, enhancing tobacco control policies and raising awareness of the liver-specific risks of smoking could help mitigate the growing global burden of NAFLD. Despite the strength of the evidence, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, although the overall sample size is large, certain subgroup analyses may have been underpowered due to limited primary studies, which could affect the precision of risk estimates in these categories. Second, significant heterogeneity was observed across included studies, likely attributable to variations in NAFLD diagnostic criteria, differences in participant characteristics across geographic regions, and diverse adjustments for confounding factors. Third, varying diagnostic methods for NAFLD (e.g., ultrasound vs. biomarkers) across studies may affect comparability. Differences in diagnostic methods and regional distribution of populations may be important reasons for heterogeneity. The fourth is the limitation of exposure assessment. The main research relies on self-reported questionnaires to determine passive smoking exposure, which is susceptible to recall and misclassification bias. Therefore, the risk estimation proposed in our study may underestimate the true extent of the association between passive smoking and NAFLD. It is necessary to conduct prospective studies using objective exposure biomarkers (such as serum cotinine levels) in the future to confirm our findings and provide more accurate risk assessments.

This study and the cited literature both use the traditional term “NAFLD.” However, during the course of this study, the International Liver Disease Expert Group issued a new consensus recommendation to update the terminology to “metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease (MASLD)” (43). Given that the diagnostic criteria for NAFLD included in the study (details in Supplementary Table 1) are highly consistent with those for MASLD, the clinical characteristics of the study population essentially overlap with the current definition of MASLD. Out of respect for the original research design and consistency of data sources, this article still uses the term “NAFLD,” but the results of this study are also applicable to patient populations that meet the diagnostic criteria for MASLD.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrates a significant association between smoking and increased risk of NAFLD. Both current and former smokers are at elevated risk, with stronger associations seen in current smokers. These findings highlight the importance of smoking cessation in the prevention of NAFLD and reinforce public health efforts targeting lifestyle modifications to reduce liver-related morbidity. Future longitudinal studies with standardized NAFLD diagnostic criteria and detailed smoking exposure assessments are warranted to further elucidate causality and underlying mechanisms.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JJ: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1670932/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; MOOSE, the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology; PICOS, the population, intervention, comparison, outcome and setting criteria; NOS, the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale checklist; AHRQ, the agency for healthcare research and quality recommended standard list; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease.

References

1. Bilson J, Sethi J, Byrne C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a multi-system disease influenced by ageing and sex, and affected by adipose tissue and intestinal function. Proc Nutr Soc. (2022) 81:146–61. doi: 10.1017/S0029665121003815

2. Targher G, Lonardo A, Byrne C. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic vascular complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2018) 14:99–114. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.173

3. Rhee E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes: an epidemiological perspective. Endocrinol Metab. (2019) 34:226–33. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2019.34.3.226

4. Le P, Tatar M, Dasarathy S, Alkhouri N, Herman W, Taksler G, et al. Estimated burden of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in US adults, 2020 to 2050. JAMA Netw Open. (2025) 8:e2454707. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.54707

5. Corica B, Proietti M. Towards a broader perspective on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and coronary artery disease relationship: managing metabolic risk beyond genetics. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2025): doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwaf004 Online ahead of print.

6. Alabdul Razzak I, Fares A, Stine J, Trivedi H. The role of exercise in steatotic liver diseases: an updated perspective. Liver Int. (2025) 45:e16220. doi: 10.1111/liv.16220

7. Easl, Easd, Easo. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical practice guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol. (2024) 81:492–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.04.031

8. Byrne C, Targher G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol. (2015) 62:S47–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.012

9. Rao Y, Kuang Z, Li C, Guo S, Xu Y, Zhao D, et al. Gut Akkermansia muciniphila ameliorates metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease by regulating the metabolism of L-aspartate via gut-liver axis. Gut Microbes. (2021) 13:1–19. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1927633

10. Zheng Y, Zhao L, Xiong Z, Huang C, Yong Q, Fang D, et al. Ursolic acid targets secreted phosphoprotein 1 to regulate Th17 cells against metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. (2024) 30:449–67. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2024.0047

11. Vesković M, Pejović M, Šutulović N, Hrnčić D, Rašić-Marković A, Stanojlović O, et al. Exploring fibrosis pathophysiology in lean and obese metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: an in-depth comparison. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:7405. doi: 10.3390/ijms25137405

12. Zhang J, Hou L, Lei S, Li Y, Xu G. The causal relationship of cigarette smoking to metabolic disease risk and the possible mediating role of gut microbiota. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2025) 290:117522. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.117522

13. Jang Y, Joo H, Park Y, Park E, Jang S. Association between smoking cessation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease using NAFLD liver fat score. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1015919. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1015919

14. Hamabe A, Uto H, Imamura Y, Kusano K, Mawatari S, Kumagai K, et al. Impact of cigarette smoking on onset of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease over a 10-year period. J Gastroenterol. (2011) 46:769–78. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0376-z

15. Liu P, Xu Y, Tang Y, Du M, Yu X, Sun J, et al. Independent and joint effects of moderate alcohol consumption and smoking on the risks of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in elderly Chinese men. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0181497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181497

16. Stroup D, Berlin J, Morton S, Olkin I, Williamson G, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. (2000) 283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

17. Lai S. Smoking and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. (2019) 114:998. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000204

18. Fricker Z, Pedley A, Massaro J, Vasan R, Hoffmann U, Benjamin E, et al. Liver fat is associated with markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in analysis of data from the framingham heart study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 17: 1157–1164.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.037

19. Zein C, Unalp A, Colvin R, Liu Y, McCullough A. Smoking and severity of hepatic fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. (2011) 54:753–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.040

20. Mallat A, Lotersztajn S. Cigarette smoke exposure: a novel cofactor of NAFLD progression? J Hepatol. (2009) 51:430–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.021

21. Torres S, Samino S, Ràfols P, Martins-Green M, Correig X, Ramírez N. Unravelling the metabolic alterations of liver damage induced by thirdhand smoke. Environ Int. (2021) 146:106242. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106242

22. Jung H, Chang Y, Kwon M, Sung E, Yun K, Cho Y, et al. Smoking and the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. (2019) 114:453–63. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0283-5

23. Wu F, Pahkala K, Juonala M, Jaakkola J, Rovio S, Lehtimäki T, et al. Childhood and adulthood passive smoking and nonalcoholic fatty liver in midlife: a 31-year cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. (2021) 116:1256–63. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001141

24. Liu E, Li Q, Pan T, Chen Y. Association between secondhand smoke exposure and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the general U.S. Adult nonsmoker population. Nicotine Tob Res. (2024) 26:663–8. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntad249

25. Lange N, Radu P, Dufour J. Prevention of NAFLD-associated HCC: role of lifestyle and chemoprevention. J Hepatol. (2021) 75:1217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.07.025

26. Chen B, Sun L, Zeng G, Shen Z, Wang K, Yin L, et al. Gut bacteria alleviate smoking-related NASH by degrading gut nicotine. Nature. (2022) 610:562–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05299-4

27. Caliri A, Tommasi S, Besaratinia A. Relationships among smoking, oxidative stress, inflammation, macromolecular damage, and cancer. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. (2021) 787:108365. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2021.108365

28. Younossi Z, Anstee Q, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2018) 15:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109

29. Derella C, Tingen M, Blanks A, Sojourner S, Tucker M, Thomas J, et al. Smoking cessation reduces systemic inflammation and circulating endothelin-1. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:24122. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03476-5

30. Aron-Wisnewsky J, Vigliotti C, Witjes J, Le P, Holleboom A, Verheij J, et al. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2020) 17:279–97. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0269-9

31. Tilg H, Adolph T, Trauner M. Gut-liver axis: pathophysiological concepts and clinical implications. Cell Metab. (2022) 34:1700–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.017

32. Canfora E, Meex R, Venema K, Blaak E. Gut microbial metabolites in obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2019) 15:261–73. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0156-z

33. Watt M, Miotto P, De Nardo W, Montgomery M. The liver as an endocrine organ-linking NAFLD and insulin resistance. Endocr Rev. (2019) 40:1367–93. doi: 10.1210/er.2019-00034

34. Chang Q, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Liu Z, Cao L, Zhang Q, et al. Healthy lifestyle and the risk of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: a large prospective cohort study. Diabetes Metab J. (2024) 48:971–82. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2023.0133

35. Mascaró C, Bouzas C, Montemayor S, Casares M, Llompart I, Ugarriza L, et al. Effect of a six-month lifestyle intervention on the physical activity and fitness status of adults with NAFLD and metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. (2022) 14:1813. doi: 10.3390/nu14091813

36. Huang Y, Xu J, Yang Y, Wan T, Wang H, Li X. Association between lifestyle modification and all-cause, cardiovascular, and premature mortality in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrients. (2024) 16:2063. doi: 10.3390/nu16132063

37. Jeong S, Oh Y, Choi S, Chang J, Kim S, Park S, et al. Association of change in smoking status and subsequent weight change with risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut Liver. (2023) 17:150–8. doi: 10.5009/gnl220038

38. Azzalini L, Ferrer E, Ramalho L, Moreno M, Domínguez M, Colmenero J, et al. Cigarette smoking exacerbates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese rats. Hepatology. (2010) 51:1567–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.23516

39. Yuan H, Shyy J, Martins-Green M. Second-hand smoke stimulates lipid accumulation in the liver by modulating AMPK and SREBP-1. J Hepatol. (2009) 51:535–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.026

40. Hao X, Song H, Su X, Li J, Ye Y, Wang C, et al. Prophylactic effects of nutrition, dietary strategies, exercise, lifestyle and environment on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Med. (2025) 57:2464223. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2025.2464223

41. Younossi Z, Zelber-Sagi S, Henry L, Gerber L. Lifestyle interventions in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2023) 20:708–22. doi: 10.1038/s41575-023-00800-4

42. Lin C, Rountree C, Methratta S, LaRusso S, Kunselman A, Spanier A. Secondhand tobacco exposure is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. Environ Res. (2014) 132:264–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.04.005

43. Rinella M, Lazarus J, Ratziu V, Francque S, Sanyal A, Kanwal F, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol. (2023) 79:1542–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.06.003

44. Caballería L, Pera G, Auladell MA, Torán P, Muñoz L, Miranda D, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with the presence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in an adult population in Spain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2010) 22:24–32. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832fcdf0

45. Koehler EM, Schouten JN, Hansen BE, van Rooij FJ, Hofman A, Stricker BH, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the elderly: results from the Rotterdam study. J Hepatol. (2012) 57:1305–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.028

46. Liu Y, Dai M, Bi Y, Xu M, Xu Y, Li M, et al. Active smoking, passive smoking, and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a population-based study in China. J Epidemiol. (2013) 23:115–21. doi: 10.2188/jea.je20120067

47. van den Berg EH, Amini M, Schreuder TC, Dullaart RP, Faber KN, Alizadeh BZ, et al. Prevalence and determinants of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in lifelines: a large Dutch population cohort. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0171502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171502

48. Kim NH, Jung YS, Hong HP, Park JH, Kim HJ, Park DI, et al. Association between cotinine-verified smoking status and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. (2018) 38:1487–94. doi: 10.1111/liv.13701

49. Okamoto M, Miyake T, Kitai K, Furukawa S, Yamamoto S, Senba H, et al. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for the onset of fatty liver disease in nondrinkers: a longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0195147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195147

50. Zhou X, Li Y, Zhang X, Guan YY, Puentes Y, Zhang F, et al. Independent markers of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a gentrifying population-based Chinese cohort. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. (2019) 35:e3156. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3156

51. Hsing JC, Nguyen MH, Yang B, Min Y, Han SS, Pung E, et al. Associations between body fat, muscle mass, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based study. Hepatol Commun. (2019) 3:1061–72. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1392

52. Takenaka H, Fujita T, Masuda A, Yano Y, Watanabe A, Kodama Y. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is strongly associated with smoking status and is improved by smoking cessation in Japanese males: a retrospective study. Kobe J Med Sci. (2020) 66:E102–12.

53. Moon JH, Koo BK, Kim W. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and sarcopenia additively increase mortality: a Korean nationwide survey. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. (2021) 12:964–72. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12719

54. Hu H, Han Y, Liu Y, Guan M, Wan Q. Triglyceride: a mediator of the association between waist-to-height ratio and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a second analysis of a population-based study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2022) 13:973823. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.973823

55. Pettinelli P, Fernández T, Aguirre C, Barrera F, Riquelme A, Fernández-Verdejo R. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with lifestyle habits in adults in Chile: a cross-sectional study from the National Health Survey 2016-2017. Br J Nutr. (2023) 130:1036–46. doi: 10.1017/S0007114523000028

56. Han M, Jeong S, Song J, Park SJ, Min Lee C, Lee K, et al. Association between the dual use of electronic and conventional cigarettes and NAFLD status in Korean men. Tob Induc Dis. (2023) 21:31. doi: 10.18332/tid/159167

57. Che Y, Tang R, Zhang H, Yang M, Geng R, Zhuo L, et al. Development of a prediction model for predicting the prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese nurses: the first-year follow data of a web-based ambispective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. (2024) 24:72. doi: 10.1186/s12876-024-03121-1

Keywords: NAFLD, active smoking, passive smoking, incidence, meta-analysis

Citation: Jin J, Zhang Y and Huang Y (2025) The relationship between tobacco and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Front. Med. 12:1670932. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1670932

Received: 22 July 2025; Accepted: 22 September 2025;

Published: 15 October 2025.

Edited by:

Rais Ahmad Ansari, Nova Southeastern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Hassan Mumtaz, Resear-Ligent Limited, United KingdomOluwafemi Balogun, Boston University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Jin, Zhang and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yiping Huang, amhodWFuZ3lwQDE2My5jb20=

Jianxiang Jin

Jianxiang Jin Yiping Huang

Yiping Huang