- 1Department of Neurosurgery, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

- 2Department of Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

- 3Department of Neurosurgery, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, United States

Background: Demarcation of malignant brain tumor boundaries is critical to achieve complete resection and to improve patient survival. Contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for diagnosis and pre-surgical planning, despite limitations of gadolinium (Gd)-based contrast agents to depict tumor margins. Recently, solid metal-based nanoparticles (NPs) have shown potential as diagnostic probes for brain tumors. Gold nanoparticles (GNPs) emerged among those, because of their unique physical and chemical properties and biocompatibility. The aim of the present study is to review the application of GNPs for in vitro and in vivo brain tumor diagnosis.

Methods: We performed a PubMed search of reports exploring the application of GNPs in the diagnosis of brain tumors in biological models including cells, animals, primates, and humans. The search words were “gold” AND “NP” AND “brain tumor.” Two reviewers performed eligibility assessment independently in an unblinded standardized manner. The following data were extracted from each paper: first author, year of publication, animal/cellular model, GNP geometry, GNP size, GNP coating [i.e., polyethylene glycol (PEG) and Gd], blood-brain barrier (BBB) crossing aids, imaging modalities, and therapeutic agents conjugated to the GNPs.

Results: The PubMed search provided 100 items. A total of 16 studies, published between the 2011 and 2017, were included in our review. No studies on humans were found. Thirteen studies were conducted in vivo on rodent models. The most common shape was a nanosphere (12 studies). The size of GNPs ranged between 20 and 120 nm. In eight studies, the GNPs were covered in PEG. The BBB penetration was increased by surface molecules (nine studies) or by means of external energy sources (in two studies). The most commonly used imaging modalities were MRI (four studies), surface-enhanced Raman scattering (three studies), and fluorescent microscopy (three studies). In two studies, the GNPs were conjugated with therapeutic agents.

Conclusion: Experimental studies demonstrated that GNPs might be versatile, persistent, and safe contrast agents for multimodality imaging, thus enhancing the tumor edges pre-, intra-, and post-operatively improving microscopic precision. The diagnostic GNPs might also be used for multiple therapeutic approaches, namely as “theranostic” NPs.

Introduction

Surgery is the mainstay of primary brain tumor management (1). The goal of image-guided neurosurgery for primary brain tumors is to achieve maximal tumor resection, while minimizing neurological morbidity and mortality related to brain manipulation of cortical and subcortical structures (2, 3). Post-surgical residual enhancing tumor volume is a strong significant negative predictor of patient survival, especially in high-grade gliomas (4). Thus, the delineation of tumor boundaries is crucial for optimizing surgical resection and improving overall survival.

Although brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is still the gold standard for brain tumor diagnosis (5, 6), it is accuracy in delineating brain tumor boundaries is limited by the pharmacological properties of the commonly used gadolinium (Gd)-based contrast agents. Indeed, these agents enhance brain tumor regions where there are major defects and abnormal permeability of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) (7). However, BBB permeability is almost normal at in the most peripheral, yet most actively replicating and invasive portions of high-grade tumors (4). Thus, visualization of tumor edges can be sub-optimal as peripheral tumor debulking may be limited, while a more extensive resection could positively impact patient survival (8). In a similar fashion, low-grade primary brain tumors induce a limited increase in BBB permeability, preventing a clear delineation of tumor edges (9). Thus, there is a need for new imaging techniques, enabling the neurosurgeon to better visualize tumor edges, regardless of BBB permeability and tumor histology and grade.

Recently, solid metal-based nanoparticles (NPs) have shown potential as diagnostic probes for brain tumors (10, 11). Nanotechnology has emerged with the goal of better understanding and manipulating materials in order to create NPs ranging from 1 to 100 nm in diameter (11). The potential of the NPs as diagnostic (and therapeutic) agents in neuro-oncology can be attributed to their chemical and physical properties, including their small size, physiological stability, and biocompatibility (11). Several NPs were tested for brain tumor imaging, including quantum dots, iron oxide NPs, superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs, carbon nanotubes, dendrimers, polyelectrolyte complex NPs, calcium phosphate NPs, perfluorocarbon NPs, and lipid-based NPs (11). Nonetheless, the main limitation for the application of metallic NPs in vitro and in vivo is cyto-toxicity due to degradation and release of toxic metal ions (12).

Gold nanoparticles (GNPs) were discovered more than one century ago. Given their remarkable biocompatibility, negligible toxicity, high-atomic number, and high-X-ray absorption coefficient, they have received significant interest recently for use in multiple imaging technologies (13). Additionally, GNPs synthesis is technically easy and cost effective (14).

To the best our knowledge, this is the first literature review to explore the application of GNPs in brain tumor diagnosis. We aim to: (1) define the main structural features of GNPs that are critical for their biological, toxic, and physical (radiological) properties; (2) review the radiological techniques that can be used in conjunction with GNPs; and (3) review experimental models for testing GNPs and explore any potential studies in humans.

Future research could include creating new GNPs specifically optimized for particular radiological techniques, as well as for preparing experimental models to test GNPs.

Materials and Methods

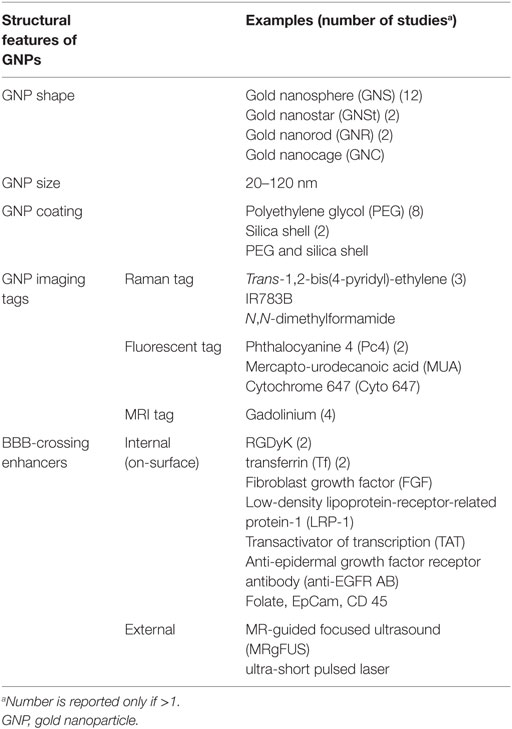

The present review was conducted according to the PRISMA statement criteria (15). The literature search was updated to April 30, 2017. No other temporal limits were applied. The search was open to both in vitro and in vivo studies. Inclusion criteria included GNPs to diagnose any kind of brain tumor in biological models including cells, animals, primates, and humans. The review included only original papers published in Pubmed-indexed peer-review journals, clearly stating the structural features of the GNPs (listed below), the experimental model/s, and the radiological technique/s applied in conjunction with the GNPs. Exclusion criteria included: papers not describing original research (i.e., reviews, perspectives, letters to the editor, commentaries, and abstracts), papers in languages other than English, description of new chemical or physical properties of GNPs without application of biological models, and papers focusing on nanotechnology but not primarily on brain tumor diagnosis or GNPs. The search was performed using the PubMed database and by scanning reference lists of the resulting articles. The search terms were “gold” AND “NP” AND “brain tumor.” Eligibility assessment was performed independently in an unblinded standardized manner by two reviewers (Antonio Meola and Navjot Chaudhary). Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus. The following data were extracted from each paper: first author, year of publication, animal/cellular model, GNP route of administration, GNP geometry, GNP size, GNP coating and imaging tags, BBB-crossing enhancers, imaging modalities applied in conjunction with the GNPs, and main conclusions of the study. Unfortunately, a quantitative comparison between studies or groups was not possible because of heterogeneity of the biological models and technical discrepancies between different GNP formulations. Therefore, no statistical analysis was performed.

Results

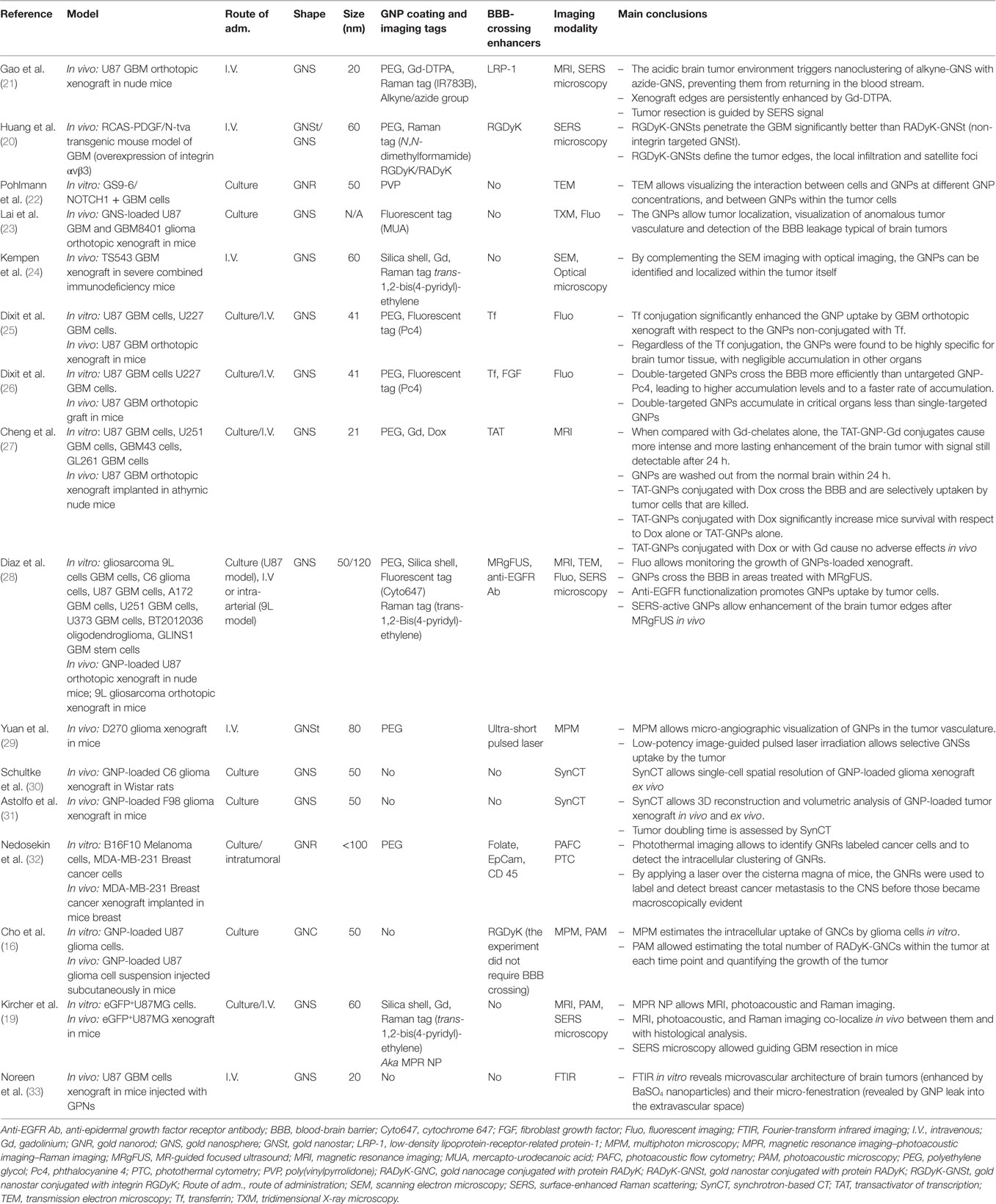

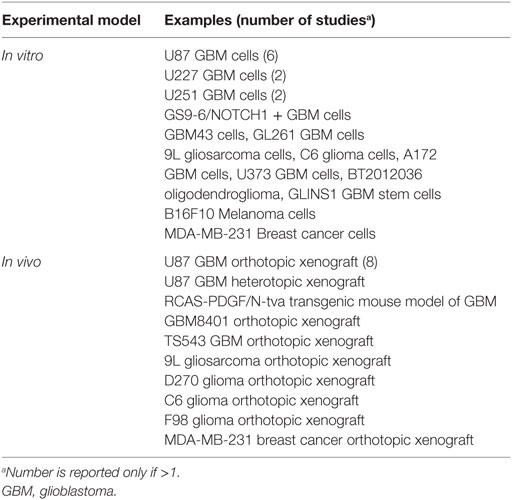

A total of 16 studies were included in our review. The PubMed search yielded 100 items. One duplicate was found. Among the collected studies, 85 were discarded because they met the exclusion criteria: reviews (16), commentaries (2), conference proceedings (1), topics different than brain tumor (17), topics different than GNPs (2), topics different than diagnosis (i.e., brain tumor therapy) (18), and applications on non-biological models (4). Two (2) citations (19, 20) were added after reviewing the bibliographies of the included papers (Figure 1). The studies included are summarized in Table 1, and an overview of the main features of the GNPs and of the experimental models is reported in Tables 2–4.

Figure 1. Flow-diagram of study selection, according to PRISMA criteria (15).

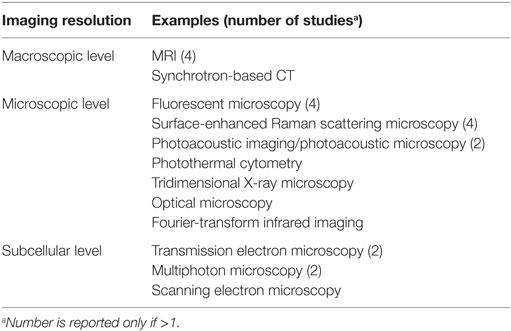

Table 4. Imaging techniques applied in conjunction with gold nanoparticles (GNPs) for brain tumor diagnosis.

Sixteen studies were published between 2011 and 2017. No studies on humans were found. Eight studies were conducted in vivo on rodent models, three studies were performed in vitro on brain tumor cells, and five studies were done in vitro and in vivo. In all the studies in vitro, the GNPs were loaded into the brain tumor cells; while in the studies in vivo, the GNPs were injected intravenously into the tail vein of the rodent models with two exceptions. In one study, the GNPs were inoculated into primary breast cancer in order to detect metastatic spread to the central nervous system (32); in another study, the GNP-loaded xenograft was heterotopically injected into the subcutaneous tissue (16).

The cellular models more commonly used in vitro were the U87 GBM cells (six studies), the U227 GBM cells (two studies), and the U251 GBM cells (two studies). Among all the other in vitro only models, one study was performed on a cellular model different than glioma, namely on melanoma and breast cancer cells (32). In vivo, the most commonly used model was the U87 orthotopic xenograft (eight studies). A single study was performed on a cellular model different than glioma, using a breast cancer orthotopic xenograft (32). Another group used an RCAS-PDGF/N-tva transgenic mouse model of GBM (20).

The shape of GNPs was nanosphere (GNS) in 12 studies, nanostar (GNSt) in 2 studies, nanorod (GNR) in 2 studies, and nanocage (GNC) in one study. The size of GNPs ranged between 20 and 120 nm. Twelve studies used GNPs with size equal or less than 60 nm. Noticeably, the GNPs with a diameter of 120 nm crossed the BBB, after permeabilization of the brain tumor region with MRI-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) (28).

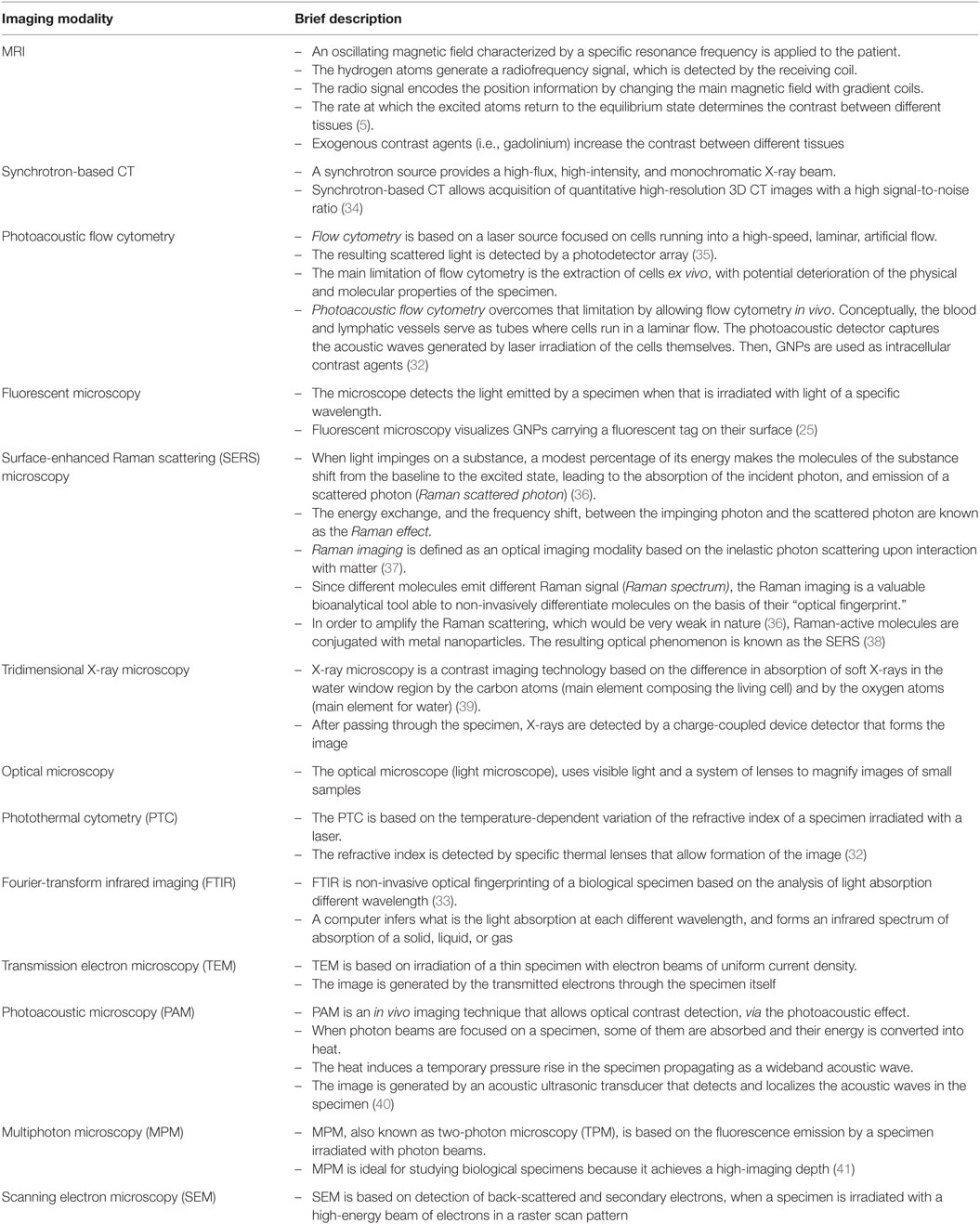

Among the 13 in vivo studies, the GNPs were covered of polyethylene glycol (PEG) in 8 studies (namely PEGylated), the GNPs were covered with a silica shell in 2 studies, and with both in one case. Several imaging modalities used GNPs to diagnose and follow tumor growth at a macroscopic and cellular level, and to define the biodistribution of GNPs at a subcellular level. The imaging techniques are summarized in Table 5. The most commonly used imaging modalities were MRI (four studies), surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) (three studies), and fluorescent microscopy (three studies). All of these techniques required specific molecules attached to the GNP surface, in order to make them detectable within the tumor cells. All the MRI-enhancing GNPs carried Gd-chelates on their surface; for fluorescent microscopy purpose, the most commonly used fluorescent tag was the phthalocyanine 4 (Pc4) (two studies); and the most commonly used SERS-active tag was the trans-1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)-ethylene (three studies).

Table 5. Reference guide for the imaging modalities used in conjunction with gold nanoparticles (GNPs).

In order to increase the penetration of the GNPs through the BBB and their uptake by tumor cells, the GNPs were functionalized with different molecules on their surface (most commonly the RADyK group and the Transferrin) and/or the BBB itself was irradiated with paired-pulsed laser or MRgFUS. The GNPs were used for therapeutic purposes by the addition of a chemotherapic agent (doxorubicin) or a photosensitizer (Pc4) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The “typical” gold nanoparticle (GNP). The most used GNPs are the nanospheres. The gold core is sometimes covered with an imaging tag (i.e., Raman tags, fluorescent tag). Then, the GNPs are often covered by a polyethylene glycol (PEG) and/or silica shell. Finally, on the GNP surface, several molecules can be conjugated serving as blood-brain barrier (BBB) crossing internal enhancers or as chemotherapy agents.

Discussion

The Structural Elements of GNPs: A Difficult Balance Between Tumor Penetration and Systemic Toxicity

The size of GNPs is critical for their physical, pharmacological, and toxic properties. The BBB is a complex barrier between the brain and the blood, which is formed by brain capillary endothelial cell tight junctions, luminal glycocalyx, basal lamina, and astrocytic foot processes. The intact BBB allows penetration of small lipophilic compounds, electroneutral compounds, and molecules under 600 Daltons. In order to use GNPs for brain imaging and/or for therapy, their size has to be tailored on the basis of the BBB restraints. Among the presented studies, the size of GNPs ranged between 20 and 120 nm, although the majority (12) had a size equal or less than 60 nm. Studies revealed that GNPs with a diameter up to 50 nm were able to pass BBB, as demonstrated by gold accumulation in the brain (42). About 0.3% of the intravenously injected GNPs with a 10 nm diameter can pass through the BBB into the brain, and this percentage remarkably drops as GNPs diameter increases (17, 42). In some studies, large GNPs (up to 120 nm) were able to cross the BBB after a temporary increase of BBB permeability, as achieved by MRgFUS (28). The size of GNPs is also critical for their toxicity. In fact, ultra-small GNPs (1.5 nm in diameter) were found to be highly cytotoxic, while approximately 10-fold larger GNPs (15 nm and above) were non-toxic at the same concentration levels (43). Thus, although there is an inverse proportion between GNP size and BBB penetration, there is not a similar correlation between size and toxicity. GNP shape can further complicate the scenario. A higher aspect ratio reduces GNPs toxicity and promotes cellular uptake (44). As an example, GNSs uptake is more efficient than GNRs uptake (44), and is less toxic (45). None of the papers on experiments performed on rodent models reported toxic reactions. Remarkably, 12 of the 13 studies performed, at least in part, using living rodent models, adopted GNSs. Other factors that might influence GNP toxicity include chemical preparation (46), high concentration, prolonged exposure (47), and the systemic route of administration (47). Nonetheless, GNPs are very biocompatible and induce minimal to no toxicity in healthy tissue (44).

The bioavailability of gold is largely dependent on the administration route. In the included papers, GNPs were injected in rodents intravenously, except when the xenograft itself was loaded with GNPs before implantation. In humans, gold preparations injected intravenously are fully absorbed within 2 h (48), while only one-fifth of the oral doses are absorbed (49). The gold diffuses to organs through the bloodstream, although the reticuloendothelial system has a remarkable affinity for the metal. Together, the liver and the bone marrow uptake 50% of injected gold (50), while the bone and skin uptake about 20% each (51). As noted above, less than 1% of injected GNPs reach the brain.

Thus, it is of paramount importance to minimize reticuloendothelial clearance of the gold, in order to maximize bioavailability for brain imaging. Various natural and synthetic polymers, including dextran (52), PEG (53), and poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (54), were employed as biocompatible coatings to prevent coagulation, promote particle monodispersion, and enhance systemic circulation of NPs. Among those, PEG was used to extensively cover the gold core of GNPs, in 9 of 13 studies performed in vivo. PEG is an FDA-approved biodegradable amphiphilic diblock copolymer with several advantages. First, PEG reduces GNPs clearance by the reticuloendothelial system and improves the exposure of the organs to GNPs (18); second, by reducing the reticuloendothelial clearance, PEG promotes GNPs accumulation in the brain tumor (55); third, PEG reduces potential intravascular aggregation of GNPs (aka “stealth effect”); fourth, PEG increases the retention of GNPs once there is tumor uptake (56); and fifth, the PEG coating serves as a platform for conjugation of further molecules to increase or broaden GNPs functionalities (20, 25).

Overcoming the “Enhanced Permeability and Retention” (EPR) Effect

In 1986, Maeda et al. observed that Evans blue binding albumin selectively accumulates in tumor tissue, after endovenous injection (57). The phenomenon was named “EPR” effect. Given the aberrant and exaggerated angioarchitecture and vascular permeability of tumors, heavy (>40 kDa) molecules can diffuse into tumor interstitial space and be retained because of impaired venous and, for some organs, lymphatic drainage. The EPR phenomenon leads to remarkable accumulation of heavy (>40 kDa) molecules, such as drugs, at concentrations several folds higher than plasma. The prerequisites for the phenomenon to occur include a large molecular weight of drugs above the renal threshold, and a sufficiently high plasma concentration for a substantial amount of time (i.e., at least 6 h in mice and rat). The EPR effect still represents the pathophysiological basis for functioning of intravenously injected GNPs (19, 21). Nonetheless, the BBB of the tumor still partially limits the penetration of foreign molecules into the brain. Therefore, maximizing brain tumor uptake of GNPs is critical both for imaging and therapeutic purposes. Schematically, we divided the method for BBB penetration enhancement into two categories. The first included all molecules attached to GNPs surface (“internal enhancers”), and the second included all methods to increase BBB permeability by using an external source of energy (“external enhancers”).

Internal Enhancers

Internal enhancers aim to selectively increase brain tumor uptake of GNPs, making them detectable for preoperative, intraoperative, and post-operative imaging techniques. As an example, since different glioma cell lines are characterized by a variable overexpression of EGFR (58), GNPs were functionalized with a monoclonal antibody anti-EGFR (Panitumumab) promoting their internalization by tumor cells (28).

Gold nanospheres were conjugated with RGDyK, an active ligand of the integrin αvβ3, a molecular marker overexpressed in about 30% of GBMs (20). At a microscopic level, GNPs conjugated with RGDyK enhanced tumor edges, loco-regional infiltration, and satellite foci remarkably better than non-integrin specific GNPs (20).

Similarly, Gd-carrying GNPs were conjugated with a transactivator of transcription (TAT) peptide derived from HIV (TAT-GNP-Gd conjugates), in order to increase GNPs penetration through the BBB. These conjugates allowed a remarkably more intense and lasting tumor enhancement with respect to Gd alone (with a signal still detectable after 24 h) closely correlating with tumor invasion topography (41, 59). Importantly, TAT-GNP-Gd conjugates also cross the normal BBB, selectively accumulate within the most peripheral tumor cells, and are washed out from normal brain tissue (27).

Gold nanoparticles were also conjugated with multiple ligands in order to promote their uptake by cells with different molecular profiles within the same tumor mass (“molecular heterogeneity”). As an example, dual-receptor GNPs, functionalized both with FGF and transferrin, were able to cross the BBB more efficiently and accumulate more intensely in the tumor with respect to untargeted GNPs or transferrin-only targeted GNPs (25, 26).

Importantly, enhanced accumulation of functionalized GNPs into the brain did not lead to accumulation in other organs, as revealed by histological analysis of several different explanted organs (kidney, liver, heart, and lung) after injection of transferrin-functionalized GNPs (25) or after injection of dual-targeted (FGF and transferrin) GNPs (26). As a consequence, enhanced accumulation of functionalized GNPs into the tumor was not accompanied by systemic or brain toxicity. The internal enhancers were also used for GNP targeting of tumors different than gliomas, such as breast cancer or melanoma metastases (32).

Internal enhancers were used to regulate GNPs aggregation inside the tumor itself. As an example, GNPs were functionalized with either the alkyne or azide chemical group. After passing through the BBB, the acidic environment typical of solid tumors promotes PEG degradation, exposure, and interaction of the functional alkyne and azide groups, allowing GNPs aggregation. Thus, GNPs rapidly form 3D spherical nanoclusters with characteristic Raman signal and MR enhancement persisting in the brain tumor interstitium for days. Conversely, GNPs diffusing in the normal brain, do not aggregate in the neutral pH environment, and are washed out (21).

External Enhancers

External enhancers include all the external sources of energy promoting BBB permeabilization, such as MRgFUS (28) and laser irradiation (29). MRgFUS was used to transiently enhance the BBB permeability in order to allow very large GNPs (ranging from 50 to 120 nm) to pass through the BBB.

Next, because of the unique physical properties of GNPs, a low-power (i.e., 35 mW) laser was used to radiate a brain tumor and elicit selective extravasation of the GNPs through the BBB of the tumor, but not of healthy brain. Interestingly, this phenomenon is limited to GNPs use. Indeed, tumor irradiation with a laser of similar power did not induce extravasation of traditional contrast agents. Thus, the mechanism of tumor BBB permeation might be attributed either to direct photothermal effect or to inflammation induced by energy bust (29). The main advantage of external enhancers is that these allow over-sized GNPs to cross the BBB. The conceptual limitation of this approach is that GNPs cross the BBB only in pre-treated areas. Thus, tumor invasion boundaries should be known a priori. Conversely, the aim of using diagnostic GNPs is in contrast to this, namely to achieve an ultra-sensitive detection of tumor edges at a macroscopic and microscopic level. Ideally, GNPs should be engineered to diffuse freely in the brain parenchyma and to be retained only in brain tumor cells, providing an accurate “mapping” of brain tumor invasion.

Imaging Methods: From Macrostructures to Nanostructures

Gold nanoparticles enabled imaging the development of tumors and the interaction between tumor and healthy brain tissue at different resolutions, ranging from a macroscopic level to a microscopic and to a subcellular level.

Macroscopic Level

The synchrotron-based head CT (SynCT) of GNPs-loaded glioma xenografts in rats, provided a 3D reconstruction of the tumor volume and shape (31, 34). This resulted in a higher spatial resolution than PET (6–8 mm) and even MRI (1 mm) (60) which is considered the “gold standard” for brain tumor diagnosis and follow-up (30). Additionally, by measuring the dilution of GNPs within subsequent tumor cells generations, SynCT allows measuring and mapping replication rates of different tumor sections (31). Unfortunately, the present approach has a limited potential for use in humans for two main reasons. First, CT imaging requires a radiation dose that might not be acceptable humans; and second, GNPs are loaded into glioma cells instead of being injected into the living animal, which does not exactly replicate the real-life scenario in humans.

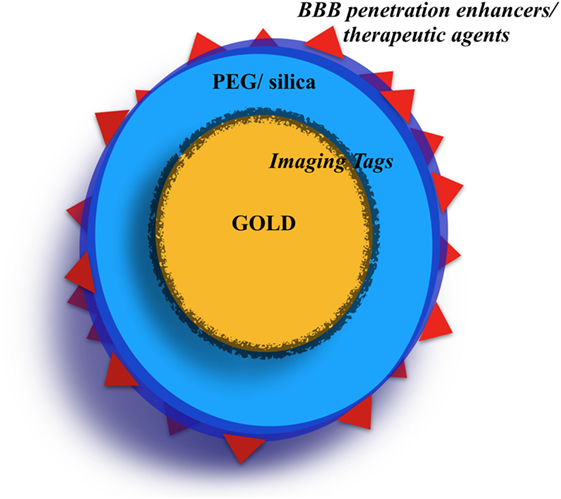

On the other hand, Gd-enhanced MRI is used in daily practice. Unfortunately, Gd mainly enhances tumor portions characterized by increased BBB permeability (19, 21, 61). Thus, the main limitation of MRI is that it does not enhance the most peripheral portion of the tumor, where highly active tumor cells infiltrate healthy brain parenchyma without an extensive BBB disruption and neoangiogenesis (8). A complete tumor resection is theoretically not possible because of imprecise tumor visualization. When compared with Gd alone, GNP-Gd conjugates allowed a remarkably more intense (up to 82-fold higher intracellular Gd concentration) and more lasting enhancement of the brain tumor, with signal still detectable after 24 h. Enhancement closely correlates with the whole tumor mass (19, 21, 27). Importantly, GNP-Gd conjugates widely penetrate the normal brain parenchyma, and are quickly washed out. So, GNPs are able to cross the BBB regardless of its integrity, selectively accumulate within the tumor cells or, otherwise are removed from normal brain tissue, as expected according to the EPR effect (57). From a practical standpoint, GNP-Gd conjugates improve tumor visualization and, in the future, might improve extent of resection. Additionally, prolonged tumor enhancement might allow for improved intraoperative MRI imaging. Intraoperative MRI is mainly limited because iatrogenic BBB disruption during surgery affects Gd distribution and, as a consequence, visualization of tumor borders (62). Conversely, if GNP-Gd conjugates are injected preoperatively, tumor resection may occur in a stepwise fashion by intraoperative MRI with no need of further contrast injections, allowing for both improved diagnostic accuracy and no additional Gd-induced toxicity. Additionally, the need for quantitative and qualitative estimation of brain shift during surgery would be not practically relevant anymore, since identification of tumor edges would not depend on finding a correspondence between intraoperative and preoperative landmarks.

Microscopic Level

Several techniques were applied to microscopic detection of tumor spread in the brain (Table 4). From a practical viewpoint, a few of them are suitable for the clinical practice.

The photoacoustic flow cytometry (PAFC) has been used to detect breast cancer metastases in vitro and in vivo (32).

Breast cancer orthotopic xenograft bearing mice were injected with GNPs into the tumor. In the following days, a photoacoustic probe approximated to the mice cisterna magna, revealed the metastatic spread of breast cancer cells containing GNPs. PAFC detected the metastatic cells in the CSF well before macroscopic brain metastases became radiologically evident. The implementation of this technique in humans might drastically change the diagnosis of brain metastases and, potentially, the timing of treatment.

Recently, the use of fluorescent markers was found to be useful for detection of microscopic tumor foci during surgery. 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), a fluorescent tumor maker, marks tumor edges intraoperatively with good sensitivity, and spatial resolution. This has been associated with increased progression-free survival in patients affected with gliomas (63). The use of 5-ALA as tumor marker has some technical limitations. First, the natural emission of light by biological structures (autofluorescence) can result in false positives and limited depth penetration of the signal; second, fast photochemical destruction (known as “photobleaching”) limits the time of tumor enhancement (37); and third, the large spectral overlap with other fluorescent imaging agents prevents the detection of multiple targets simultaneously (known as “multiplexing”) (47). Several fluorescent tumor markers have been conjugated with GNPs in order to increase selectivity of intracellular uptake by tumor cells. As an example, fluorescent markers, such as cytochrome 647 (26) and Pc4 (28), conjugated with GNPs allowed fluorescent microscopy localizing and quantifying intracellular uptake of GNPs by tumor cells as well as by normal brain tissue and peripheral organs. Thus, the fluorescent GNPs might be used for accurate intraoperative detection of residual tumor foci. Fluorescent GNPs can be further functionalized with Raman tags (28). Although Raman imaging is not currently available in the neurosurgical practice, in experimental models, SERS microscopy revealed that GNPs delineate tumor edges, the loco-regional infiltration (corresponding to the GBM digitations) and even the satellite foci remote from the main tumor mass, strongly correlating with spatial distribution of GBM histological markers (20, 21, 28).

Importantly, Raman signal is more stable and intense with respect to fluorescent markers such as 5-ALA (64). GNPs labeled with Raman tags might be the basis for intraoperative detection of GBM cells with SERS. Additionally, the photostability of Raman-active GNPs might allow a more persistent signal emission with respect to fluorescent markers.

Nanoparticle multiplexing allows for performing multiple image modalities using the same NP. As an example, GNPs served as contrast agents for macroscopic imaging (MRI and PAFC) as well as for microscopic imaging (SERS microscopy) (19). The triple-modality NP, known as MPR (magnetic resonance–photoacoustic–Raman) NP caused stable enhancement of tumor edges and loco-regional infiltration even after 24 h post-endovenous injection, with robust correlation in the spatial distribution of the signal between the three modalities.

Subcellular Level

Several different techniques were employed to study the intracellular distribution of GNPs and the tumor pathophysiology. As an example, transmission electron microscopy visualizes the interaction and penetration of GNPs through the tumor membrane, the interactions of GNPs inside the tumor cells, and the ejection of GNPs from the cellular membrane (22). A correlative optical and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) technique visualized the GNPs accumulation in the brain tumor cells in experimental rodent models (24). SEM alone is not able to distinguish tumor from healthy tissue, while it allows an accurate definition of the size, shape, and structure of NPs. Thus, the GNPs can be visualized as well as be localized inside the cells (with a spatial accuracy of 10 µm), by overlaying the SEM and optical images.

Lai et al. (23) reported using X-ray microscopy to visualize the aberrant microvasculature associated with the development of brain tumors. X-ray microscopy provided the first evidence of GNPs leaking through the BBB defects of brain tumors, in contrast to the normal brain tissue unaffected by GNPs leaking. Then, Fourier-transform infrared imaging was used to characterize different patterns of tumor angioarchitecture on the basis of the specific size of fenestrations, by injecting at the same time GNPs of different sizes (33).

“Theranostic” GNPs: The Therapeutic Side of Diagnostic GNPs

Nanoparticles can behave simultaneously as diagnostic agents, therapeutic agents, and as markers of response to chemotherapy and radiation therapy (65, 66). NPs functioning both for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes are defined as “theranostic” NPs. As an example, GNPs were conjugated with photosensitizers such as Pc4. These GNPs can be used for diagnostic purposes because of their fluorescence, as well as, for therapeutic purposes. When irradiated with a laser, Pc4 causes photosensitization, and cell death (26).

Additionally, GNPs can be used as carriers for chemotherapy agents that cannot cross the BBB under physiological conditions. As an example, doxorubicin is highly effective on glioma cells in vitro, and is 2,000-fold more powerful than the standard-of-care temozolomide (67). Unfortunately, doxorubicin was abandoned as a chemotherapy agent for glioma in humans because it is not able to cross the BBB. Doxorubicin conjugated with GNPs (GNP-Dox) has different pharmacokinetic properties than doxorubicin injected alone. First, after intravenous injection, almost the entire amount of GNP-Dox passed through the BBB and entered the glioma cells; second, GNP-Dox caused no toxic effect on healthy brain or on other organs such as spleen, liver, kidney, and heart; third, since the link between GNPs and Doxorubicin was achieved by an acid-labile hydrazone group, the GNP-Dox could selectively release doxorubicin within the acidic environment of the lysosomes (pH = 4.5–6.0), leading to glioma cell death. As a consequence, a highly selective and highly concentrated topical chemotherapy is achieved, with no adverse effects. The use of GNPs as chemotherapy carriers might open the door to reconsider other agents that are currently not deemed efficacious for brain tumor treatment.

Limitations

At the moment, the interaction of the structural features of GNPs with their physical, biological, and toxic properties is not completely clear. A more detailed understanding would be crucial to maximize brain tumor uptake and to minimize the potential toxic effects on humans. Additionally, a quantitative and statistical comparison between the results of the included studies was not possible, because of the heterogeneity of the biological models, as well as, of the structural and biological features of the used GNPs.

Importantly, our review did not provide any evidence of ongoing or completed clinical trials. Thus, all the conclusions regarding the potential applications of GNPs for brain tumor diagnosis and treatment should be considered field of ongoing research. A clinical application is still not available. Nonetheless, ample experience in the use of gold for medical purposes (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis) makes GNPs promising agents for brain tumor diagnosis and treatment in humans.

Conclusion

Gold nanoparticles are highly selective contrast agents for preoperative, intraoperative (with macroscopic and microscopic resolution), and post-operative imaging of primary and metastatic brain tumors. In comparison with Gd alone, GNPs can persist in the tumor mass for hours and potentially days after a single injection. The selectivity of GNPs for brain tumor cells, their prolonged retention in the tumor itself, as well as their effectiveness as therapeutic agents provides the theoretical basis for the “theranostic cycle” of GNPs (Figure 3). Injected GNPs allow for accurate delineation of the tumor mass and its loco-regional invasion, as visualized by MRI. Once tumor debulking has been completed, intraoperative imaging might allow for detailed macroscopic (by intraoperative MRI) and microscopic (by Raman imaging and fluorescent imaging) detection and removal of loco-regional tumor invasion. Next, the most remote satellite brain tumor foci can be treated with local focused chemotherapy. Should the tumor recur, a new “theranostic cycle” can be repeated because of the minimal toxicity of GNPs in vivo.

Figure 3. The theranostic cycle. (1) The brain tumor diagnosis is achieved by advanced brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium-conjugated gold nanoparticles (GNPs). (2) After the usual surgical debulking of the tumor mass, the loco-regional invasion is identified and removed in two steps: a macroscopic phase [using intraoperative MRI (ioMRI)] and (3) a microscopic phase involving GNPs suitable for Raman imaging, fluorescent imaging, photoacoustic imaging, photoacoustic flow cytometry. (4) The GNPs can be loaded with therapeutic agents, such as chemotherapy agents, that can target and destroy potential tumor residuals. If the tumor should recur, the cycle may be repeated.

Nomenclature

| Anti-EGFR Ab | Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| Cyto647 | Cytochrome 647 |

| EPR effect | Enhanced permeability and retention effect |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| Fluo | Fluorescent imaging |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared imaging |

| Gd | Gadolinium |

| GNC | Gold nanocage |

| GNP | Gold nanoparticle |

| GNP-Dox | GNP conjugated with doxorubicin |

| GNR | Gold nanorod |

| GNS | Gold nanosphere |

| GNSt | Gold nanostar |

| LRP-1 | Low-density lipoprotein-receptor-related protein-1 |

| MPM | Multiphoton microscopy |

| MPR | Magnetic resonance imaging–photoacoustic imaging–Raman imaging |

| MRgFUS | MRI-guided focused ultrasound |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MUA | Mercapto-urodecanoic acid |

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| PAFC | Photoacoustic imaging |

| PAM | Photoacoustic microscopy |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| Pt4 | Phthalocyanine 4 |

| PTC | Photothermal cytometry |

| PVP | Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) |

| RADyK-GNC | Gold nanocage conjugated with protein RADyK |

| RADyK-GNSt | Gold nanostar conjugated with protein RADyK |

| RGDyK-GNSt | Gold nanostar conjugated with integrin RGDyK |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SERS | Surface-enhanced Raman scattering |

| SynCT | Synchrotron-based CT |

| TAT | Transactivator of transcription |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| Tf | Transferrin |

| TXM | Tridimensional X-ray microscopy |

| 5-ALA | 5-aminolevulinic acid |

Author Contributions

AM and SC concept and design, AM and NC data collection and tables and figures, AM, JR, SC, and MS analysis of data, AM and JR drafting of the paper, JR and SC critical review of the manuscript, All the authors final approval.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for support from Carol Bade and Craig and Kim Darian to SC.

Funding

Carol Bade and Craig and Kim Darian supported SC.

References

1. Buckner JC. Factors influencing survival in high-grade gliomas. Semin Oncol (2003) 30(6 Suppl 19):10–4. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.11.031

2. Duffau H. Surgery of low-grade gliomas: towards a ‘functional neurooncology’. Curr Opin Oncol (2009) 21(6):543–9. doi:10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283305996

3. Duffau H. Brain Mapping: From Neural Basis of Cognition to Surgical Applications. Wien/New York: Springer (2011). xii, 392 p.

4. Grabowski MM, Recinos PF, Nowacki AS, Schroeder JL, Angelov L, Barnett GH, et al. Residual tumor volume versus extent of resection: predictors of survival after surgery for glioblastoma. J Neurosurg (2014) 121(5):1115–23. doi:10.3171/2014.7.JNS132449

5. McRobbie DW. MRI from Picture to Proton. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK/New York: Cambridge University Press (2007). xii, 394 p.

6. Brindle KM, Izquierdo-Garcia JL, Lewis DY, Mair RJ, Wright AJ. Brain tumor imaging. J Clin Oncol (2017) 35(21):2432–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.72.7636

7. Cha S. Update on brain tumor imaging: from anatomy to physiology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol (2006) 27(3):475–87.

8. Li YM, Suki D, Hess K, Sawaya R. The influence of maximum safe resection of glioblastoma on survival in 1229 patients: can we do better than gross-total resection? J Neurosurg (2016) 124(4):977–88. doi:10.3171/2015.5.JNS142087

9. Ewelt C, Floeth FW, Felsberg J, Steiger HJ, Sabel M, Langen KJ, et al. Finding the anaplastic focus in diffuse gliomas: the value of Gd-DTPA enhanced MRI, FET-PET, and intraoperative, ALA-derived tissue fluorescence. Clin Neurol Neurosurg (2011) 113(7):541–7. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.03.008

10. Youns M, Hoheisel JD, Efferth T. Therapeutic and diagnostic applications of nanoparticles. Curr Drug Targets (2011) 12(3):357–65. doi:10.2174/138945011794815257

11. Nune SK, Gunda P, Thallapally PK, Lin YY, Forrest ML, Berkland CJ. Nanoparticles for biomedical imaging. Expert Opin Drug Deliv (2009) 6(11):1175–94. doi:10.1517/17425240903229031

12. Shubayev VI, Pisanic TR II, Jin S. Magnetic nanoparticles for theragnostics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev (2009) 61(6):467–77. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.007

13. Thakor AS, Jokerst J, Zavaleta C, Massoud TF, Gambhir SS. Gold nanoparticles: a revival in precious metal administration to patients. Nano Lett (2011) 11(10):4029–36. doi:10.1021/nl202559p

14. Saha K, Agasti SS, Kim C, Li X, Rotello VM. Gold nanoparticles in chemical and biological sensing. Chem Rev (2012) 112(5):2739–79. doi:10.1021/cr2001178

15. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ (2009) 339:b2700. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2700

16. Cho EC, Zhang Y, Cai X, Moran CM, Wang LV, Xia Y. Quantitative analysis of the fate of gold nanocages in vitro and in vivo after uptake by U87-MG tumor cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl (2013) 52(4):1152–5. doi:10.1002/anie.201208096

17. De Jong WH, Hagens WI, Krystek P, Burger MC, Sips AJ, Geertsma RE. Particle size-dependent organ distribution of gold nanoparticles after intravenous administration. Biomaterials (2008) 29(12):1912–9. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.037

18. van Vlerken LE, Vyas TK, Amiji MM. Poly(ethylene glycol)-modified nanocarriers for tumor-targeted and intracellular delivery. Pharm Res (2007) 24(8):1405–14. doi:10.1007/s11095-007-9284-6

19. Kircher MF, de la Zerda A, Jokerst JV, Zavaleta CL, Kempen PJ, Mittra E, et al. A brain tumor molecular imaging strategy using a new triple-modality MRI-photoacoustic-Raman nanoparticle. Nat Med (2012) 18(5):829–34. doi:10.1038/nm.2721

20. Huang R, Harmsen S, Samii JM, Karabeber H, Pitter KL, Holland EC, et al. High precision imaging of microscopic spread of glioblastoma with a targeted ultrasensitive SERRS molecular imaging probe. Theranostics (2016) 6(8):1075–84. doi:10.7150/thno.13842

21. Gao X, Yue Q, Liu Z, Ke M, Zhou X, Li S, et al. Guiding brain-tumor surgery via blood-brain-barrier-permeable gold nanoprobes with acid-triggered MRI/SERRS signals. Adv Mater (2017) 29(21):1–9. doi:10.1002/adma.201603917

22. Pohlmann ES, Patel K, Guo S, Dukes MJ, Sheng Z, Kelly DF. Real-time visualization of nanoparticles interacting with glioblastoma stem cells. Nano Lett (2015) 15(4):2329–35. doi:10.1021/nl504481k

23. Lai SF, Ko BH, Chien CC, Chang CJ, Yang SM, Chen HH, et al. Gold nanoparticles as multimodality imaging agents for brain gliomas. J Nanobiotechnology (2015) 13:85. doi:10.1186/s12951-015-0140-2

24. Kempen PJ, Kircher MF, de la Zerda A, Zavaleta CL, Jokerst JV, Mellinghoff IK, et al. A correlative optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy approach to locating nanoparticles in brain tumors. Micron (2015) 68:70–6. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2014.09.004

25. Dixit S, Novak T, Miller K, Zhu Y, Kenney ME, Broome AM. Transferrin receptor-targeted theranostic gold nanoparticles for photosensitizer delivery in brain tumors. Nanoscale (2015) 7(5):1782–90. doi:10.1039/c4nr04853a

26. Dixit S, Miller K, Zhu Y, McKinnon E, Novak T, Kenney ME, et al. Dual receptor-targeted theranostic nanoparticles for localized delivery and activation of photodynamic therapy drug in glioblastomas. Mol Pharm (2015) 12(9):3250–60. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00216

27. Cheng Y, Dai Q, Morshed RA, Fan X, Wegscheid ML, Wainwright DA, et al. Blood-brain barrier permeable gold nanoparticles: an efficient delivery platform for enhanced malignant glioma therapy and imaging. Small (2014) 10(24):5137–50. doi:10.1002/smll.201400654

28. Diaz RJ, McVeigh PZ, O’Reilly MA, Burrell K, Bebenek M, Smith C, et al. Focused ultrasound delivery of Raman nanoparticles across the blood-brain barrier: potential for targeting experimental brain tumors. Nanomedicine (2014) 10(5):1075–87. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2013.12.006

29. Yuan H, Wilson CM, Xia J, Doyle SL, Li S, Fales AM, et al. Plasmonics-enhanced and optically modulated delivery of gold nanostars into brain tumor. Nanoscale (2014) 6(8):4078–82. doi:10.1039/c3nr06770j

30. Schultke E, Menk R, Pinzer B, Astolfo A, Stampanoni M, Arfelli F, et al. Single-cell resolution in high-resolution synchrotron X-ray CT imaging with gold nanoparticles. J Synchrotron Radiat (2014) 21(Pt 1):242–50. doi:10.1107/S1600577513029007

31. Astolfo A, Schultke E, Menk RH, Kirch RD, Juurlink BH, Hall C, et al. In vivo visualization of gold-loaded cells in mice using x-ray computed tomography. Nanomedicine (2013) 9(2):284–92. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2012.06.004

32. Nedosekin DA, Juratli MA, Sarimollaoglu M, Moore CL, Rusch NJ, Smeltzer MS, et al. Photoacoustic and photothermal detection of circulating tumor cells, bacteria and nanoparticles in cerebrospinal fluid in vivo and ex vivo. J Biophotonics (2013) 6(6–7):523–33. doi:10.1002/jbio.201200242

33. Noreen R, Pineau R, Chien CC, Cestelli-Guidi M, Hwu Y, Marcelli A, et al. Functional histology of glioma vasculature by FTIR imaging. Anal Bioanal Chem (2011) 401(3):795–801. doi:10.1007/s00216-011-5069-1

34. Salome M, Peyrin F, Cloetens P, Odet C, Laval-Jeantet AM, Baruchel J, et al. A synchrotron radiation microtomography system for the analysis of trabecular bone samples. Med Phys (1999) 26(10):2194–204. doi:10.1118/1.598736

35. Galanzha EI, Zharov VP. Photoacoustic flow cytometry. Methods (2012) 57(3):280–96. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.06.009

36. Zavaleta CL, Kircher MF, Gambhir SS. Raman’s “effect” on molecular imaging. J Nucl Med (2011) 52(12):1839–44. doi:10.2967/jnumed.111.087775

37. Harmsen S, Huang R, Wall MA, Karabeber H, Samii JM, Spaliviero M, et al. Surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering nanostars for high-precision cancer imaging. Sci Transl Med (2015) 7(271):271ra7. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3010633

38. Etchegoin PG, Meyer M, Blackie E, Le Ru EC. Statistics of single-molecule surface enhanced Raman scattering signals: fluctuation analysis with multiple analyte techniques. Anal Chem (2007) 79(21):8411–5. doi:10.1021/ac071231s

39. Yamamoto Y, Shinohara K. Application of X-ray microscopy in analysis of living hydrated cells. Anat Rec (2002) 269(5):217–23. doi:10.1002/ar.10166

40. Yao J, Wang LV. Photoacoustic microscopy. Laser Photon Rev (2013) 7(5):758–78. doi:10.1002/lpor.201200060

41. Yuan H, Fales AM, Vo-Dinh T. TAT peptide-functionalized gold nanostars: enhanced intracellular delivery and efficient NIR photothermal therapy using ultralow irradiance. J Am Chem Soc (2012) 134(28):11358–61. doi:10.1021/ja304180y

42. Sonavane G, Tomoda K, Makino K. Biodistribution of colloidal gold nanoparticles after intravenous administration: effect of particle size. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces (2008) 66(2):274–80. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.07.004

43. Pan Y, Neuss S, Leifert A, Fischler M, Wen F, Simon U, et al. Size-dependent cytotoxicity of gold nanoparticles. Small (2007) 3(11):1941–9. doi:10.1002/smll.200700378

44. Chithrani BD, Chan WC. Elucidating the mechanism of cellular uptake and removal of protein-coated gold nanoparticles of different sizes and shapes. Nano Lett (2007) 7(6):1542–50. doi:10.1021/nl070363y

45. Aillon KL, Xie Y, El-Gendy N, Berkland CJ, Forrest ML. Effects of nanomaterial physicochemical properties on in vivo toxicity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev (2009) 61(6):457–66. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.010

46. Goodman CM, McCusker CD, Yilmaz T, Rotello VM. Toxicity of gold nanoparticles functionalized with cationic and anionic side chains. Bioconjug Chem (2004) 15(4):897–900. doi:10.1021/bc049951i

47. Thakor AS, Luong R, Paulmurugan R, Lin FI, Kempen P, Zavaleta C, et al. The fate and toxicity of Raman-active silica-gold nanoparticles in mice. Sci Transl Med (2011) 3(79):79ra33. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3001963

48. Palmer DG, Dunckley JV. Gold levels in serum during the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with gold sodium thiomalate. Aust N Z J Med (1973) 3(5):461–6. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.1973.tb03123.x

49. Walz DT, DiMartino MJ, Griswold DE, Intoccia AP, Flanagan TL. Biologic actions and pharmacokinetic studies of auranofin. Am J Med (1983) 75(6A):90–108. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(83)90481-3

50. Gottlieb NL, Smith PM, Smith EM. Tissue gold concentration in a rheumatoid arthritic receiving chrysotherapy. Arthritis Rheum (1972) 15(1):16–22. doi:10.1002/art.1780150103

51. Gottlieb NL. Comparison of the kinetics of parenteral and oral gold. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl (1983) 51:10–4. doi:10.3109/03009748309095338

52. Berry CC, Wells S, Charles S, Aitchison G, Curtis AS. Cell response to dextran-derivatised iron oxide nanoparticles post internalisation. Biomaterials (2004) 25(23):5405–13. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.046

53. Gupta AK, Gupta M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials (2005) 26(18):3995–4021. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.012

54. D’Souza AJ, Schowen RL, Topp EM. Polyvinylpyrrolidone-drug conjugate: synthesis and release mechanism. J Control Release (2004) 94(1):91–100. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.09.014

55. Gref R, Minamitake Y, Peracchia MT, Trubetskoy V, Torchilin V, Langer R. Biodegradable long-circulating polymeric nanospheres. Science (1994) 263(5153):1600–3. doi:10.1126/science.8128245

56. Kwon GS. Polymeric micelles for delivery of poorly water-soluble compounds. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst (2003) 20(5):357–403. doi:10.1615/CritRevTherDrugCarrierSyst.v20.i5.20

57. Greish K. Enhanced permeability and retention of macromolecular drugs in solid tumors: a royal gate for targeted anticancer nanomedicines. J Drug Target (2007) 15(7–8):457–64. doi:10.1080/10611860701539584

58. Voigt M, Braig F, Gothel M, Schulte A, Lamszus K, Bokemeyer C, et al. Functional dissection of the epidermal growth factor receptor epitopes targeted by panitumumab and cetuximab. Neoplasia (2012) 14(11):1023–31. doi:10.1593/neo.121242

59. Krpetic Z, Saleemi S, Prior IA, See V, Qureshi R, Brust M. Negotiation of intracellular membrane barriers by TAT-modified gold nanoparticles. ACS Nano (2011) 5(6):5195–201. doi:10.1021/nn201369k

60. Patel V, Papineni RV, Gupta S, Stoyanova R, Ahmed MM. A realistic utilization of nanotechnology in molecular imaging and targeted radiotherapy of solid tumors. Radiat Res (2012) 177(4):483–95. doi:10.1667/RR2597.1

61. Cheng Y, Meyers JD, Agnes RS, Doane TL, Kenney ME, Broome AM, et al. Addressing brain tumors with targeted gold nanoparticles: a new gold standard for hydrophobic drug delivery? Small (2011) 7(16):2301–6. doi:10.1002/smll.201100628

62. Olubiyi OI, Ozdemir A, Incekara F, Tie Y, Dolati P, Hsu L, et al. Intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging in intracranial glioma resection: a Single-Center, Retrospective Blinded Volumetric Study. World Neurosurg (2015) 84(2):528–36. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.04.044

63. Tonn JC, Stummer W. Fluorescence-guided resection of malignant gliomas using 5-aminolevulinic acid: practical use, risks, and pitfalls. Clin Neurosurg (2008) 55:20–6.

64. Nie S, Emory SR. Probing single molecules and single nanoparticles by surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Science (1997) 275(5303):1102–6. doi:10.1126/science.275.5303.1102

65. Bian X, Song ZL, Qian Y, Gao W, Cheng ZQ, Chen L, et al. Fabrication of graphene-isolated-Au-nanocrystal nanostructures for multimodal cell imaging and photothermal-enhanced chemotherapy. Sci Rep (2014) 4:6093. doi:10.1038/srep06093

66. Ferrari M. Cancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Cancer (2005) 5(3):161–71. doi:10.1038/nrc1566

Keywords: gold, nanoparticle, brain tumor, Raman scattering, magnetic resonance imaging, photoacoustic imaging, glioma, blood-brain barrier

Citation: Meola A, Rao J, Chaudhary N, Sharma M and Chang SD (2018) Gold Nanoparticles for Brain Tumor Imaging: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 9:328. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00328

Received: 03 February 2018; Accepted: 25 April 2018;

Published: 14 May 2018

Edited by:

Adam M. Sonabend, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Brad E. Zacharia, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, United StatesDavid M. Peereboom, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, United States

Copyright: © 2018 Meola, Rao, Chaudhary, Sharma and Chang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Antonio Meola, YW1lb2xhQHN0YW5mb3JkLmVkdQ==

Antonio Meola

Antonio Meola Jianghong Rao

Jianghong Rao Navjot Chaudhary

Navjot Chaudhary Mayur Sharma

Mayur Sharma Steven D. Chang

Steven D. Chang