- 1Section of Child and Adolescent Neuropsychiatry, Department of Human Neuroscience, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 2Behavioural Neuroscience, Section of Child and Adolescent Neuropsychiatry, Department of Human Neuroscience, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 3Department of Public Health and Infectious Diseases, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 4Department of Maternal and Child Health and Urological Science, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 5Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Background: Some studies have demonstrated the high impact of headache and migraine in several areas of children and adolescents' life. In recent years, there has been an increase in scientific interest in the relationship between migraine and emotional regulation, investigating the possible consequences of emotional dysregulation on physical and mental health. While some studies have been carried out on the relationship between alexithymia and headache or migraine (especially in adults), no data exist on relationship between Theory of Mind (TOM), metacognition, and alexithymia in children and adolescents with migraine.

Methods: Children with diagnosis of migraine without aura (MWoA) (36 males and 34 females) were compared to a healthy control group (31 males and 39 females). The age range was from 8 to 13 years in both groups. All children completed the Alexithymia Questionnaire for Children (AQC) for the assessment of alexithymia levels and the Domain of Social Perception included in the NEPSY-II to evaluate levels of TOM. Metacognitive development was evaluated with Io e La Mia Mente for children aged between 8 and 10 years and with Metacognitions Questionnaire for Children (MCQ-C) for children from 11 to 13.

Results: There were no differences between children with MWoA and the control group in metacognitive abilities; only in the subscale “Negative Meta Worrying” of MCQ-C girls scored higher than boys, regardless of the group they were part of. Also, in the NEPSY-II subscale there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups. Children with MWoA scored higher in the AQC subscales “Difficulty Identifying Feelings” and “Difficulty Describing Feelings” than controls. Moreover, children between 8 and 10 years statistically differed from older children in “Difficulty Identifying Feelings” and in Total Score.

Conclusion: Our data suggest that children with MWoA have no metacognitive and TOM problems compared to a healthy group. The experimental group showed higher traits of alexithymia, confirming what suggested by other studies in the literature. Future research will have to focus on migraine with aura and tension-type headache to evaluate any differences with children with MWoA.

Introduction

Headache is one of the most common neurological symptoms reported in childhood and adolescence and constitutes a serious health problem that may lead to high levels of school absenteeism and to impairment in several other areas (1, 2). Furthermore, it is a disorder associated with numerous comorbid conditions that can determine a negative impact on the quality of life and individual well-being (3, 4). For example, headache is often associated to emotional and behavioral problems, especially internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety, medical problems like asthma, allergies, sleep disorders, obesity, etc. (5). These factors can negatively affect child and family alike interfering in daily activities, social interaction, and negatively affecting school performance (6). Recently, many researchers are focusing their interest on the relationship between headache or migraine and emotional regulation and, in particular, they are trying to explore the possible consequences of emotional dysregulation on physical and mental health (7, 8). An interesting research line concerns the relationship between alexithymia and headache. Alexithymia refers to a difficulty in identifying, verbalizing and describing feelings, to a reduced level of emotional experience and to a limited imagination (9). Starting from the 1990s, there had been accumulating evidence of alexithymic characteristics in adult patients with primary headache (10–12). However, little research has been conducted on the relationship between alexithymia and primary headache in developmental age, and no study has investigated the cognitive and socio-relational aspects associated with this disorder (13). We decided to investigate a possible connection between alexithymia and metacognitive abilities or Theory Of Mind (TOM) disfunctions in subjects with primary headache. In fact, metacognition refers to the perception and regulation of emotions (in oneself and in other people), to their development, to their receiving causal attribution and meaning (14). Cognitive monitoring and the ability to mentally represent one's own and others' mental state can be considered fundamental pre-requisites for the recognition and the autonomous regulation of emotions (15). Currently only few studies have addressed the association between headache or migraine and impairment on metacognitive or TOM abilities in children and adolescents (16).

For these reasons, we picked as primary objective of this case-control study the comparison of the prevalence of alexithymia and deficit in TOM and metacognition abilities in pediatric patients with migraine without aura (MWoA) and in healthy control subjects. Our secondary objective was the comparison of test scores between children and pre-adolescents and between males and females. Finally, we intended to highlight any significant results within the experimental Group (EG).

Methods

Participants

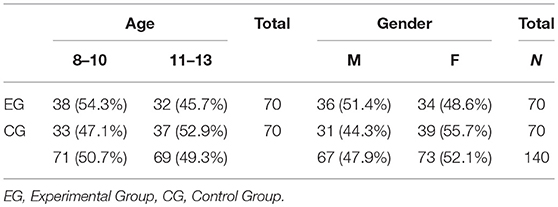

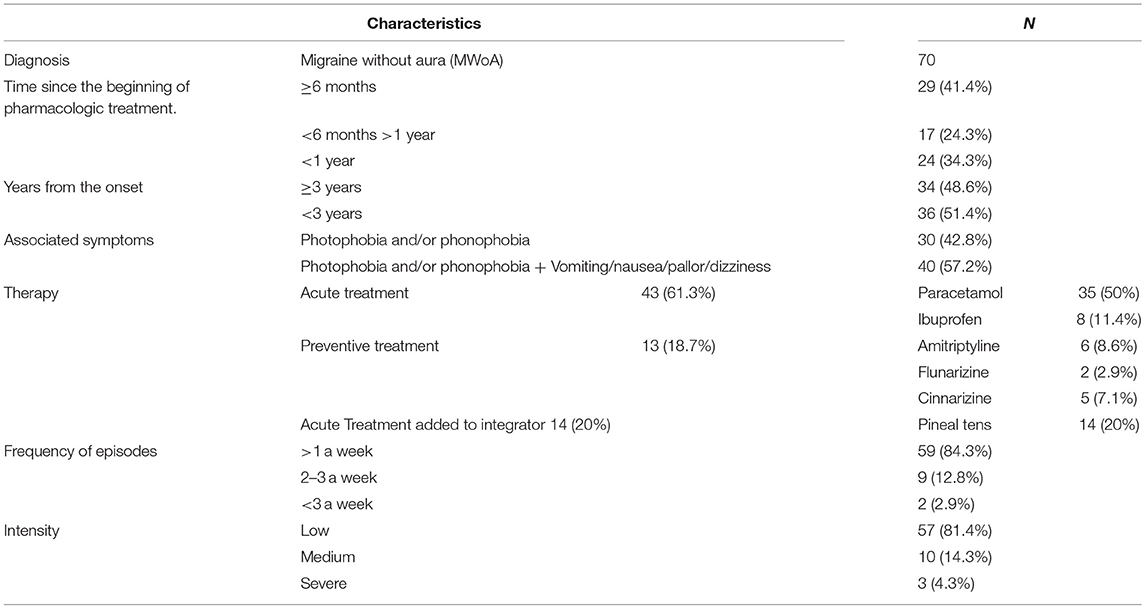

The study involved a total of 140 subjects divided into two groups: EG consisted of 70 subjects (36 males and 34 females) aged 8 to 13 years (mean age 10.18, SD 1.55), attending the Center for the diagnosis and treatment of Juvenile Headache located in the Department of Pediatrics of the Policlinico Umberto I Hospital in Rome. These children and pre-adolescents had previously received a diagnosis of MWoA according to The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition beta version (ICHD-3B) (17). The inclusion criteria were the presence of an established diagnosis of MWoA and the absence of any psychiatric disorders or a diagnosis of a secondary headache. Table 1 presents the basic demographic data for the two groups. Table 2 lists the key characteristics of the EG.

The control group (CG) consisted of 70 healthy subjects (31 males and 39 females) (mean age 10.57 SD 1.66), of age and gender matched to the EG. The exclusion criteria were the presence of a medical history of primary and secondary headaches and any psychiatric disease. Both parents of all the children signed a written consent before their inclusion in the research. The EG clinical information were collected through both the headache diary and the clinical record.

Written informed consent was obtained from all parent's subjects. The study was conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome (Prot. N 336/19).

Measures

Alexithymia

Alexithymia was assessed by the validated Italian version (18) of the Alexithymia Questionnaire for Children (AQC) (19), a simplified form of the original adult questionnaire for alexithymia developed by Bagby et al. (20) (Toronto Alexithymia Scale, TAS-20). Consistent with the TAS-20, this 20-item self-rating questionnaire measures the following three factors: Difficulty Identifying Feelings (DIF), Difficulty Describing Feelings (DDF), externally-oriented thinking (EOT). Responses to each item are given using a 3-point Likert scale with a score ranging from 0 (not true), 1 (a bit true) to 2 (true). This different approach from the traditional 5-point scale (used for the TAS-20) was used to simplify the response scale for children and to provide clear verbal labels for each answer category. DIF is an index of respondents' difficulty in identifying an experience as an affective state: seven items (1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 13, 14) assess the ability to identify feelings and to distinguish them from the somatic sensation that accompanies emotional arousal. DDF consists of five items (2, 4, 11, 12, 17) that assess the capacity to name and describe feelings to other people. EOT consists of eight items (5, 8, 10, 15, 16, 18–20) assessing EOT. Finally, there is the Total Score obtained by the sum of all scores: a high total score indicates greater alexithymic tendencies. Based on other research, this test can be administrated to children 8 years of age and older (21, 22).

Metacognition

To measure the level of metacognitive development of subjects aged between 8 and 10 years, the questionnaire “Io e la mia mente” (IeLMM) was administered (23). This questionnaire allows to assess the child's basal metacognitive level. The items stimulate a reflection on the mental world and on the strategies used for memory and learning tasks. All the items are accompanied by a graphic representation that simplifies the content and helps with the compilation of the test. It is a 15-item self-rating questionnaire with multiple choice answers and it can be administered individually or collectively, with no time limits. The final score is obtained by adding the score of correct answers; higher scores indicate greater metacognitive abilities.

To measure the level of metacognitive development of subjects aged between 11 and 13 years the Italian validated version (24) of the “Metacognitions Questionnaire for Children” (MCQ-C) (25) was administered. The adaptation by Bacow et al. (25) consists in simplifying the language of some items for use with young children. It allows to separate functional vs. dysfunctional forms of the meta-cognitive processes and it comprises 22 items and five subscales: Positive Meta-Worry (PMW); Negative Meta-Worry (NMW); Superstition, Punishment and Responsibility (SPR); Cognitive Monitoring (CM). Participants respond using a 4-point Likert scale indicating the agreement with each statement (from 1 “do not agree to 4” agree very much). The total score is considered a general measure of metacognitive awareness and processes and it range from 22 to 88, with higher scores indicating greater negative metacognitive activity. Since the MCQ-C test in Italy had already been used on children aged 11 and over (24), according to our knowledge, we preferred to use a different test for younger children, separating younger children from pre-adolescents. Furthermore, we noticed that a few 8-year-olds had some difficulty in understanding the questions of the MCQ-C and therefore we opted for this alternative method.

Theory of Mind

The level of the development of the theory of mind was assessed by two sub-tests from the Domain of Social Perception included in the NEPSY-II (26, 27), a battery for neuropsychological assessment in children aged between 3 and 16 years. These two tests investigate the ability to interpret the intentions and point of view of others and the ability to understand how these affect people's behavior. It is divided in two parts: Part A (Verbal Task) assesses the ability to understand mental constructs (such as beliefs, intentions, emotions, fantasy, and fiction) as well as the ability to understand that others have their thoughts, ideas, feelings that may differ from the observer's. It includes 15 items (questions on stories and pictures that require an understanding of the other's point of view). Part B (Contextual Task) assesses the ability to understand how emotions are connected to a social context and to recognize the appropriate state of mind. It includes eight items (a picture representing a social context and four alternative photos that represent the possible mood of the protagonist). Each item can get a score of 0 or 1 depending on the accuracy of the answer and the total is calculated by adding the scores of all the items.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data were recorded as absolute frequencies and percentages. Sub-scale scores were summarized in terms of median and interquartile ranges. Since the data are not normally distributed, the study employed Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis Test to find out differences between the groups at different tests (IeLMM, MCQ, AQC, TOM). Spearman correlation test was used to assess the correlation between sub-scale scores. The data were analyzed with the free statistical software R, version 3.5.1 (https://www.r-project.org/), and for each statistical analysis were considered significant P < 0.05.

Results

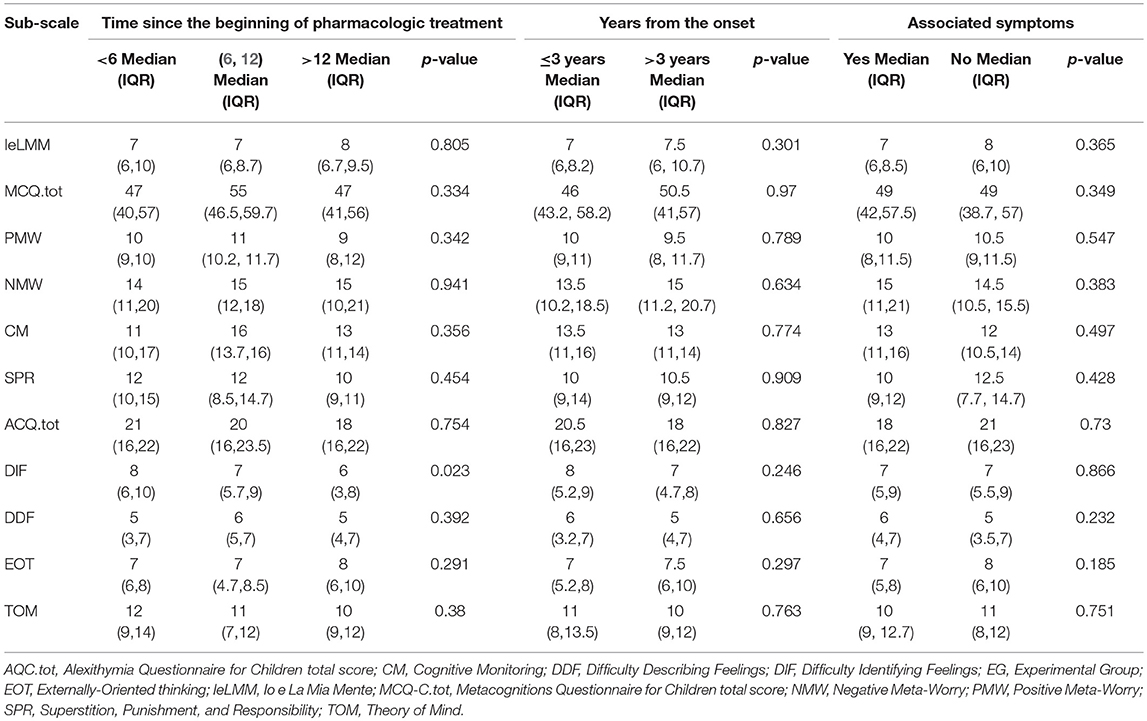

The scores tests of the EG and the CG were compared, then, were compared males and females regardless of group and age and finally, children and pre-adolescents (8–10 vs. 11–13 years). We also study features within the EG. Initially, several clinical variables were collected in the migraine patients, with the idea of looking for a possible association between the psychological measures detected and the headache characteristics. However, the variables “frequency” (≤ 2 weeks/between 2 and 3 weeks/>3 weeks), “intensity” (low/medium/severe), and “therapy” were excluded from the analysis because they were characterized by a strong heterogeneity and it was not possible to make a comparison (as shown in Table 2). Instead, the variables “years from onset,” (more or less than 3 years), “associated symptoms” (presence of other symptoms besides phonophobia and photophobia) and “Time since the beginning of pharmacologic treatment” (≤6 months–between 6 months and 1 year, >1 year) have been studied.

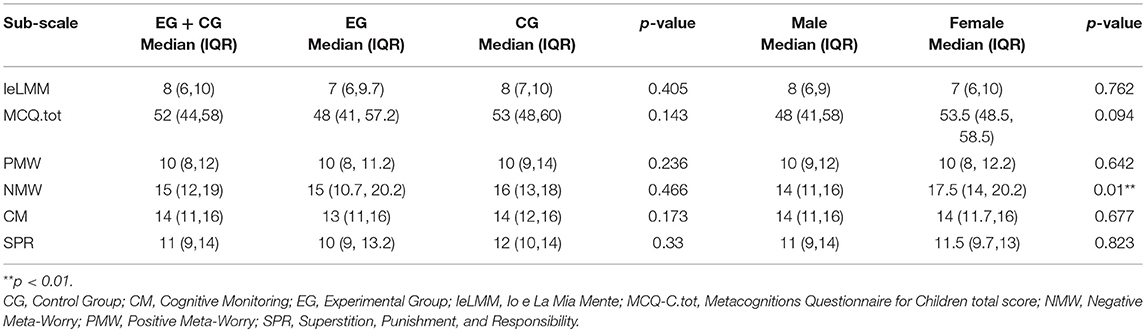

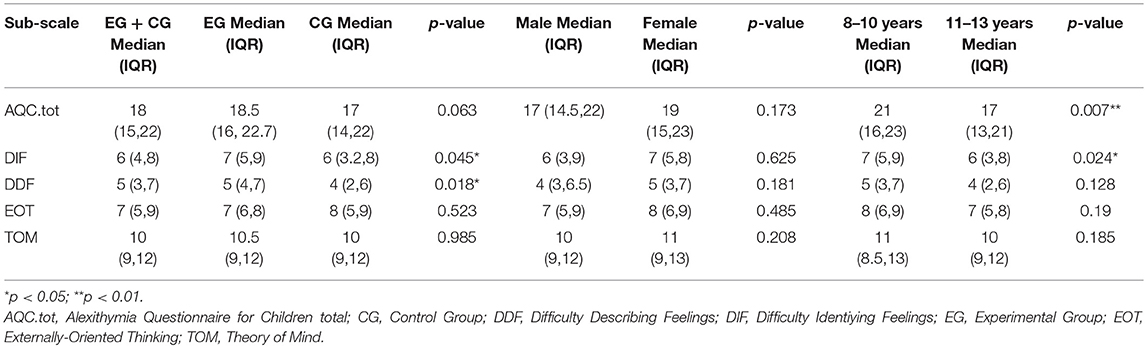

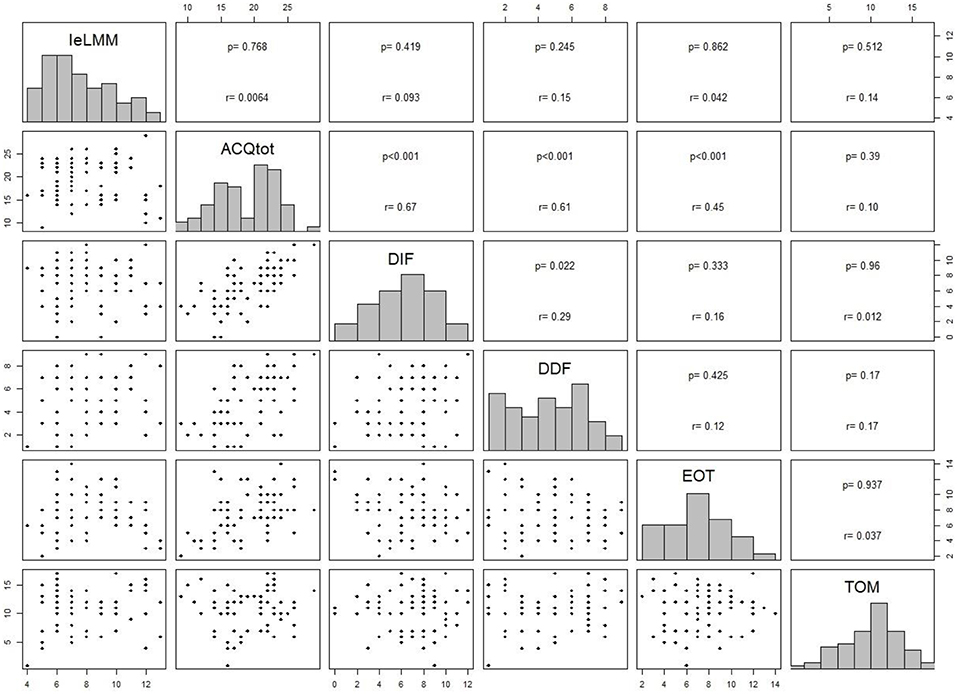

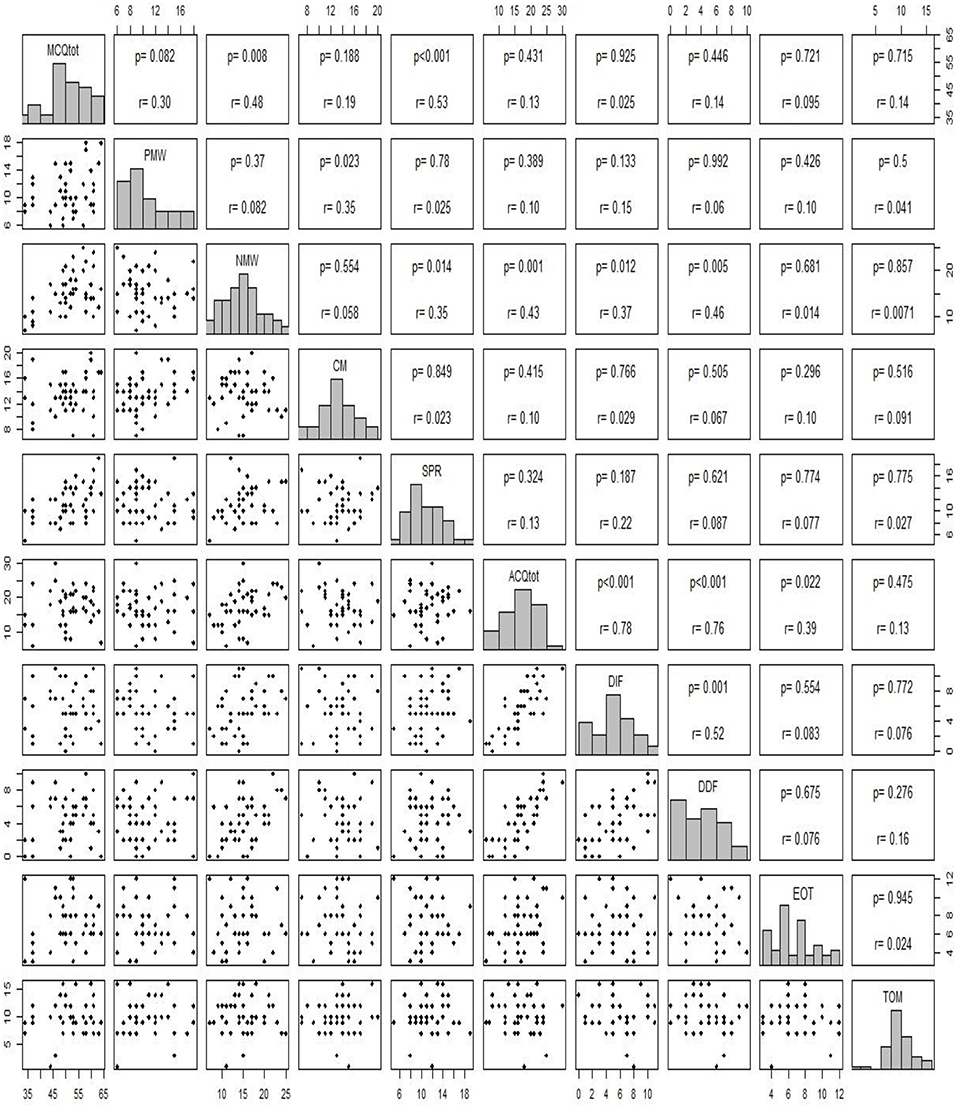

In Table 3 we report the comparison of IeLMM and MCQ-C between EG and CG and between Males and Females. Table 4 shows the comparison of AQC and TOM of EG vs. CG, Male vs. Female and children aged 8–10 vs. pre-adolescents 11–13. In Table 5 there are within group results. In Figure 1 there are the correlation between MCQ-C, AQC and TOM and in Figure 2 between IeLMM, AQC, and TOM.

Alexithymia

The AQC scores were significantly different between the experimental group and the control group in the subscales DDF and DIF (respectively, p = 0.04; p = 0.01), where the clinical group scored higher better in both subscales. Younger children (8–10) obtained higher scores in the total score (AQC.Tot) and in the DIF than pre-adolescents (11–13). There were no other significant differences among groups or between males and females. We observed no significant differences within the clinical group, for any of the variables. Finally, the total score of the AQC was statistically positive correlated as expected, with the three subscales DIF, DDF, EOT (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the DIF subscale correlated significantly, in a positive way, with the DDF subscale (p < 0.05). The total, DIF, and DDF subscales correlated positively with NMW (p < 0.001; p < 0.01; p = 0.005, respectively).

Metacognition

No significant difference was identified neither between the children of the EG and those of the CG, nor between the males and the females. Furthermore, there were no significant differences within the EG. Even in the total score and in each subscale of the MCQ-C there were no significant differences between the migraineurs and the healthy pre-adolescents. The only significant difference was observed between males and females in the NMW subscale, with girls reporting higher scores (p = 0.01). The correlation analysis showed that the PMW scale positively correlated with the CM subscale (p = 0.02) and that NMW correlated positively with SPR (p = 0.01). Furthermore, there is a positive correlation between NMW subscale and all the subscales of ACQ, excepting for EOT. Visibly, each sub-scale of the MCQ-C positively correlated with the MCQ total score, except for CM.

Theory of Mind

In the Domain of Social Perception of Nepsy-II there were no significant differences neither between the children in the EG and those in the CG, nor between males and females, or between children aged 8–10 and those aged 11–13 and within the EG. Moreover, the TOM test scores did not correlate with the score of any other test or subscale considered.

Discussion

The first relevant result of this study is the association found among children with migraine and the higher presence of some alexithymic traits. In fact, the EG scored higher on DIF and DDF compared to the CG. This could suggest that children with MWoA have a greater difficulty identifying and describing their emotions than children without any disease. Although only a few publications in the literature have provided data on the association between headache (in particular migraine) and alexithymia in childhood, our results are in line with the evidence available on children with TTH (21, 28), on adolescents (8) and on adult patients (10–12). In addition, younger children (8–10 years), regardless of the group they belonged to, scored higher than the older children (11–13 years) in AQC.tot and DIF. Indeed, younger children could show more difficult to identifying and describe their feelings for a physiological immaturity of cognitive and emotional development as suggested by other studies (29–31).

The absence of statistical significance for all the analyses conducted within the experimental group could be explained by the fact that the variables we assessed (“Time since the beginning of pharmacological treatment,” “Years from the onset” and “Associated Symptoms”), do not affect the abilities of emotional recognition and expression. Probably the frequency and the intensity of the migraine attacks might have a greater impact (32).

There are not many studies that investigated the association between metacognition and TOM abilities and headache in childhood and adolescence (16). However, given the importance of beliefs and metacognitive processes for emotional regulation, it has been hypothesized that the cephalalgic subjects, in addition to having greater alexithymic traits, may also have lower metacognitive skills than healthy subjects. This hypothesis would be consistent with the slight cognitive dysfunction found in recent studies in migraine patients (33, 34). From the present research, no significant difference emerged in metacognitive abilities between the clinical group and the control group either in 8–10 year-old children nor in 11–13 pre-adolescents.

It is probable that despite the fact that the questionnaire Io e La Mia Mente is a reliable tool with a good internal consistency, it focuses more on the metacognitive strategies that help to improve learning abilities compared to the assessment of monitoring and understanding of interior personal experience. On the other hand, we can hypothesize that the life conditions of children with headache, do not influence the metacognitive abilities as much as those linked to alexithymia, and perhaps the differences in this area manifest themselves more at a later age. For this reason, we expected different results in older children in whom the MCQ-C more directly investigated the phenomenon of “worry,” a cognitive-emotional process often linked to negative outcomes and individual discomfort (24). Also in this case, there were no significant differences between the group of migraine patients and the control group. It is possible that the degree of awareness of the cognitive monitoring of one's thoughts is not necessarily linked to psychopathological outcomes and consequently the clinical and non-clinical groups do not differ even in the positive/negative beliefs reported.

However, we can assume that the significant difference emerged in the NMW subscale between male and female, where girls scored higher than boys is probably linked to the fact that generally during the transition to adolescence, and during adolescence itself, girls tend to have higher levels of anxiety, rumination, and depressive symptoms, as well as a negative attribution style compared to boys (24, 35, 36).

The observation that NMW positively correlates significantly with the AQC.tot, DIF, and DDF can be attributed to the fact that having greater negative metacognitive beliefs also results in greater difficulty in managing one's own feelings. Vice versa greater difficulty in recognizing and expressing one's emotions could lead to greater negative metacognitive beliefs. Finally, we were surprised by finding no difference between the CG and the EG in consideration of the close relationship between TOM and affective regulation. It would seem that TOM is independent from all the variables we studied and, moreover, that the migraine condition does not influence the development of this ability. In a future study it would be interesting to use a different tool for evaluating TOM.

In our sample we do not enrolled children and adolescents with chronic migraine. The chronicity process of pain, and in particular of migraine, in addition to an early onset may have an impact on mentalization and emotional awareness (37). It would be interesting to make a comparison between children and adolescents with chronic and episodic migraine and to detect any differences in mentalization and theory of mind abilities.

Limitations and Future Prospective

One of the limitations of this research is the relatively low number of participants. A larger sample would allow to investigate and compare the variables excluded in this work such as: the intensity and the frequency of the migraine attacks, the familiarity, and the type of therapy. A second limitation is that the clinical sample includes a specific population of patients with MWoA who voluntarily attends a specialist center, and which could result in a selection bias. Finally, having used self-administered tests, the component of social desirability must be taken into account. Our plan is to compare children with migraine with aura, without aura and those with TTH to verify the impact of the diagnosis and of the different cephalalgic characteristics.

Conclusion

Main results of this study showed no differences between children with MWoA and healthy subjects in Theory of Mind and in metacognitive abilities, but the experimental group has showed higher alexithymia traits compared to control group. Moreover, migraine characteristics do not seem to affect the psychological construct studied in this research.

The present research provides new and original data on the relationship between MWoA and alexithymia in childhood and pre-adolescence. This is a field where there are very few studies in literature and none has analyzed in depth the metacognitive and TOM aspects in these age groups. Our results on alexithymia are in line with the current theoretical assumptions and experimental evidences, and they contribute to confirm the existence of a statistically significant association between migraine and alexithymic traits in children and pre-adolescents. In addition, our results also allow to further validate the AQC, the only tool available to measure the construct of alexithymia in pediatric age. Furthermore, the identification of no difference between metacognitive and TOM abilities and MWoA between groups merits further investigation.

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all parent's subjects. The study was conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome (Prot. N 336/19).

Author Contributions

VG, GN, AQ, and NF conceived and designed the study and they are responsible for data acquisition. DAF, AV, GT, DC, BB, RC, PV, FG, CP, and TG were responsible for critical revision of this manuscript. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

AQC, Alexithymia Questionnaire for Children; CG, Control Group; CM, Cognitive Monitoring; DDF, Difficulty Describing Feelings; DIF, Difficulty Identifying Feelings; EG, Experimental Group; EOT, Externally-Oriented Thinking; IeLMM, Io e La Mia Mente; MCQ-C, Metacognitions Questionnaire for Children; MWoA, Migraine Without Aura; NMW, Negative Meta-Worry; PMW, Positive Meta-Worry; SPR, Superstition, Punishment and Responsibility; TOM, Theory of Mind.

References

1. Öztop DB, Taşdelen BI, PoyrazogLu HG, Ozsoy S, Yilmaz R, Sahin N, et al. Assessment of psychopathology and quality of life in children and adolescents with migraine. J Child Neurol. (2016) 31:837–42. doi: 10.1177/0883073815623635

2. Ferracini GN, Dach F, Speciali JG. Quality of life and health-related disability in children with migraine. Headache. (2014) 54:325–34. doi: 10.1111/head.12251

3. Blaauw BA, Dyb G, Hagen K, Holmen TL, Linde M, Wentzel-Larsen T, et al. Anxiety, depression and behavioral problems among adolescents with recurrent headache: the Young-HUNT study. J Headache Pain. (2014) 15:38. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-15-38

4. Rocha-Filho PA, Santos PV. Headaches, quality of life, and academic performance in schoolchildren and adolescents. Headache. (2014) 54:1194–202. doi: 10.1111/head.12394

5. Bellini B, Arruda M, Cescut A, Saulle C, Persico A, Carotenuto M, et al. Headache and comorbidity in children and adolescents. J Headache Pain. (2013) 24:79. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-14-79

6. Dyb G, Stensland S, Zwart JA. Psychiatric comorbidity in childhood and adolescence headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. (2015) 19:5. doi: 10.1007/s11916-015-0479-y

7. Nimnuan C, Asawavichienjinda T, Srikiatkhachorn A. Potential risk factors for psychiatric disorders in patients with headache. Headache. (2012) 52:90–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.02038.x

8. Cerutti R, Valastro C, Tarantino S, Valeriani M, Faedda N, Spensieri V, et al. Alexithymia and psychopathological symptoms in adolescent outpatients and mothers suffering from migraines: a case control study. J Headache Pain. (2016) 17:39. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0640-y

9. Galván EL. 2014 Alexithymia: indicator of communicative deficit in emotional health 6th International Conference on Intercultural Education “Education and Health: From a transcultural perspective.” Soci Behav Sci. (2014) 132:603–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.360

10. Wise TN, Mann LS, Jani N, Jani S. Illness beliefs and alexithymia in headache patients. Headache. (1994) 34:362–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3406362.x

11. Yücel B, Kora K, Ozyalçín S, Alçalar N, Ozdemir O, Yücel A, et al. Depression, automatic thoughts, alexithymia, and assertiveness in patients with tension-type headache. Headache. (2002) 42:194–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02051.x

12. Muftuoglu MN, Herken H, Demirci H, Virit O, Neyal A. Alexithymic features in migraine patients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2004) 254:182–6. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0466-5

13. Natalucci G, Faedda N, Calderoni D, Cerutti R, Verdecchia P, Guidetti V. Headache and alexithymia in children and adolescents: what is the connection? Front Psychol. (2018) 9:48. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00048

14. Bonfils KA, Luther L, George S, Buck KD, Lysaker PH. The role of metacognitive self-reflectivity in emotional awareness and subjective indices of recovery in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2016) 204:903–8. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000599

15. Fonagy P, Gergely G, Jurist E. Affect Regulation, Mentalization and The Development of the Self. London: Karnac Books (2004).

16. Faedda N, Natalucci G, Calderoni D, Cerutti R, Verdecchia P, Guidetti V. Metacognition and headache: which is the role in childhood and adolescence? Front Neurol. (2017) 8:650. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00650

17. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). Cephalalgia. (2013) 33:629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658

18. Di Trani M, Tomassetti N, Bonadies M, Capozzi F, De Gennaro L, Presaghi F, et al. Un Questionario Italiano per l'Alessitimia in Età Evolutiva: struttura fattoriale e attendibilità. Psicologia Della Salute. (2009) 131–43. doi: 10.3280/PDS2009-002009

19. Rieffe C, Oosterveld P, Terwogt MM. An alexithymia questionnaire for children: factorial and concurrent validation results. Pers Individ Dif . (2006) 40:123–33. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.05.013

20. Bagby RM, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale—I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psycosom Res. (1994) 38:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1

21. Gatta M, Canetta E, Zordan M, Spoto A, Ferruzza E, Manco I, et al. Alexithymia in juvenile primary headache sufferers: a pilot study. J Headache Pain. (2011) 12:71–80. doi: 10.1007/s10194-010-0248-6

22. Donfrancesco R, Di Trani M, Gregori P, Auguanno G, Melegari MG, Zaninotto S, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and alexithymia: a pilot study. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. (2013) 5:361–7. doi: 10.1007/s12402-013-0115-9

23. Friso G, Drusi S, Cornoldi C. II questionario ≪Io e la mia mente≫: standardizzazione di uno strumento per la valutazione delle abilità metacognitive. Difficoltà Di Apprendimento. (2013) 18, 355–367.

24. Benedetto L, Di Blasi D, Pacicca P. Worry and meta-cognitive beliefs in childhood anxiety disorders. MJCP. (2014) 1. doi: 10.6092/2282-1619/2013.1.932

25. Bacow TL, Pincus DB, Ehrenreich JT, Brody LR. The metacognitions questionnaire for children: development and validation in a clinical sample of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. (2009) 23:727–36. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.02.013

26. Korkman M, Kirk U, Kemp S NEPSY-II: A Developmental Neuropsychology Assessment. 2nd Edition. Firenze: Giunti O.S. Organizzazioni Speciali (2011).

27. Urgesi C, Campanella F, Fabbro F. NEPSY-II. 2nd Edition. Contributo alla taratura italiana. Firenze: Giunti O.S. Organizzazioni Speciali (2011).

28. Gatta M, Spitaleri C, Balottin U, Spoto A, Balottin L, Mangano S, et al. Alexithymic characteristics in pediatric patients with primary headache: a comparison between migraine and tension-type headache. J Headache Pain. (2015) 16:98. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0572-y

29. van der Velde J, Gromann PM, Swart M, Wiersma D, de Haan L, Bruggeman R, et al. Alexithymia influences brain activation during emotion perception but not regulation. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. (2015) 10:285–93. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu056

30. Pouga L, Berthoz S, de Gelder B, Grzes J. Individual differences in socioaffective skills influence the neural bases of fear processing: the case of alexithymia. Hum Brain Mapp. (2010) 31:1469–81. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20953

31. Lane RD, Schwartz GE. Levels of emotional awareness: a cognitivedevelopmental theory and its application to psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry. (1987) 144:133–43. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.2.133

32. Huang L, Dong HJ, Wang Y, Xiao Z. Duration and frequency of migraines affect cognitive function: evidence from neuropsychological tests and event-related potentials. J Headache Pain. (2017) 18:54. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0758-6

33. Santangelo G, Russo A, Trojano L, Falco F, Marcuccio L, Siciliano M, et al. Cognitive dysfunctions and psychological symptoms in migraine without aura: a cross-selectional study. J Headache Pain. (2016) 17:76. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0667-0

34. Lee SH, Kang Y, Cho SJ. Subjective cognitive decline in patients with migraine and its relationship with depression, anxiety, and sleep quality. J Headache Pain. (2017) 18:77. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0779-1

35. Isensee C, Fernandez Castelao C, Kröner-Herwig B. Developmental trajectories of paediatric headache–sex-specific analyses and predictors. J Headache Pain. (2016) 17:32. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0627-8

36. Gard MG, Kring AM. Sex differences in the time course of emotion. Emotion. (2007) 7:429–37 doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.429

Keywords: alexithymia, metacognition, theory of mind, children, pre-adolescents, migraine without aura, MWoA

Citation: Natalucci G, Faedda N, Quinzi A, Alunni Fegatelli D, Vestri A, Turturo G, Verdecchia P, Bellini B, Pirisi C, Calderoni D, Giannotti F, Cerutti R, Giacolini T and Guidetti V (2019) Alexithymia, Metacognition, and Theory of Mind in Children and Preadolescents With Migraine Without Aura (MWoA): A Case-Control Study. Front. Neurol. 10:774. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00774

Received: 12 May 2019; Accepted: 02 July 2019;

Published: 17 July 2019.

Edited by:

Massimiliano Valeriani, Bambino Gesù Children Hospital (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Aynur Özge, Mersin University, TurkeyMarco Carotenuto, University of Campania, Luigi Vanvitelli Caserta, Italy

Copyright © 2019 Natalucci, Faedda, Quinzi, Alunni Fegatelli, Vestri, Turturo, Verdecchia, Bellini, Pirisi, Calderoni, Giannotti, Cerutti, Giacolini and Guidetti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vincenzo Guidetti, dmluY2Vuem8uZ3VpZGV0dGlAdW5pcm9tYTEuaXQ=

Giulia Natalucci1

Giulia Natalucci1 Noemi Faedda

Noemi Faedda Annarita Vestri

Annarita Vestri Paola Verdecchia

Paola Verdecchia Rita Cerutti

Rita Cerutti Teodosio Giacolini

Teodosio Giacolini Vincenzo Guidetti

Vincenzo Guidetti