- 1School of Nursing, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

- 2Vascular Access Clinic, Lanzhou University Second Hospital, Lanzhou, China

- 3Department of Cardiovascular, Lanzhou University Second Hospital, Lanzhou, China

- 4Department of Nursing, Lanzhou University Second Hospital, Lanzhou, China

Objective: This study explored latent profiles of Health Information-Seeking Behavior (HISB) among stroke patients and analyzed its influencing factors.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, 311 stroke participants from two tertiary care hospitals in Gansu Province, China, were recruited between January and May 2025 using convenience sampling. Data were collected using a general information questionnaire, the Health Information-Seeking Behavior Scale, and the Health Behavior Decision-Making Assessment Scale for Stroke Patients. Latent profile analysis (LPA) was employed to identify distinct HISB profiles.

Results: Three latent profiles were identified: the high-demand low-barrier positive group, the moderate-balanced group, and the low-demand high-barrier negative group. Key predictors of profile membership included age, education level, monthly personal income, and the presence of comorbid chronic diseases.

Conclusion: The identification of three distinct HISB trait types provides an evidence-based foundation for developing personalized health education and tailored decision support interventions. Healthcare professionals can leverage this classification system to customize communication strategies for patients with different traits, deliver tiered information support, and ultimately empower patients to achieve better health behaviors and health outcomes.

1 Introduction

Stroke represents a clinical syndrome arising from a group of vascular risk factors. Data from the 2021 Global Burden of Disease(GBD) Study indicate that stroke was the third most common GBD level 3 cause of death in 2021, accounting for 10.7% of all deaths. It was also the fourth leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), representing 5.6% of total DALYs (1). In 2021, there were 93.8 million prevalent cases of stroke globally, with 11.9 million new cases occurring annually (1). China bears the most significant stroke burden globally (2). In 2021, the number of stroke patients in China accounted for 28.1% of the global total. Furthermore, it is projected that by 2050, the number of stroke patients will reach 34.27 million. As a chronic disease, stroke imposes a substantial health and economic burden on patients, their families, and society (3).

Research both domestically and internationally has reached a consensus that stroke is preventable and controllable and that about 84% of strokes are associated with correctable risk factors, such as behavioral, metabolic, psychosocial, and environmental factors (4). Behavioral change interventions are the most direct and effective interventions for controlling stroke risk factors and preventing morbidity and recurrence (5). Studies indicate that comprehensive behavioral interventions such as promoting healthy diets, regular exercise, and smoking cessation can reduce stroke incidence by 18 to 29%, often yielding greater overall benefits than drug interventions alone (6). A Brazilian study trained community health workers to enhance public awareness of stroke risks and promote behavioral changes, significantly improving participants’ lifestyles and quality of life (7). Thus, with behavioral change at its core, implementing multidimensional health management for stroke patients can effectively reduce the disability rate, mortality rate, disease burden, and recurrence risk of stroke and ultimately realize the overall improvement of the patient’s quality of life and functional independence (8).

With the development of modern economic society and mobile Internet communication technology, health information has become a crucial factor influencing people’s behavior and social activities in contemporary society. It has gradually evolved into a key variable influencing individual health behaviors (9, 10). On the one hand, by actively acquiring health information, individuals can systematically improve their knowledge of disease-related information, thereby significantly enhancing their ability to assess and recognize disease risk. On the other hand, health behaviors are influenced by how individuals cognitively process information and how information is presented. Patients make health behavior decisions by evaluating the efficacy of the queried health information and then implementing scientifically based health behaviors to prevent or control diseases (11, 12). Improving health information access behaviors in stroke patients may positively affect changing health behaviors and promoting functional recovery (13, 14). In recent years, multiple studies have provided direct evidence supporting this assertion. A qualitative study of elderly stroke patients found that active information-seeking behavior was significantly associated with higher self-efficacy and healthier behaviors, affirming the positive role of health information in secondary stroke prevention (15). Another multicenter cross-sectional study demonstrated that patients who effectively accessed and understood health information during rehabilitation achieved significantly superior self-management capabilities and functional independence scores. The health behavior decisions facilitated by this effective information access substantially enhanced patients’ quality of life and long-term prognosis outcomes (16). Therefore, research on health information-seeking behavior and health behavior decision-making in stroke patients can help solve health behavior management problems, and it has particular theoretical value and practical significance for implementing precise behavioral interventions and improving individual health outcomes.

However, the relationship between health Information-seeking behavior and behavioral decision-making in stroke patients remains underexplored. Furthermore, previous studies have evaluated patients’ health information-seeking behaviors based on scale scores, ignoring inter-individual heterogeneity (17, 18) and limiting themselves to a single variable or relationship between variables on the other, which deviates from the complex cognitive patterns of individuals in real life (19). Latent profile analysis (LPA), as an individual-centred classification technique (20), can identify patient subgroups exhibiting distinct health information-seeking behaviors. Based on this, healthcare professionals can move beyond one-size-fits-all educational approaches. By designing and implementing tailored interventions that address the behavioral characteristics of different subgroups, they can better match specific patient needs. This facilitates more effective translation of health information into sustained health behavior decisions.

Therefore, the present study employed latent profile analysis to investigate the latent characteristics of health information access behaviors among stroke patients and their relationship with health behavior decision-making, aiming to provide a robust evidence base for targeted behavioral interventions, improve patients’ access to health information. We believe that achieving more effective and personalized patient education will significantly enhance long-term clinical outcomes, including improved functional independence and reduced risk of stroke recurrence.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design, participants, and ethics

This cross-sectional study utilized a convenience sampling method to recruit 311 stroke patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria from January to May 2025 from the neurology, neurosurgery, and cerebrovascular disease departments of two tertiary-level A hospitals in Lanzhou City, serving as the survey subjects. Inclusion criteria comprised of patients who: (1) Meeting stroke diagnostic criteria (21); (2) patients aged ≥18 years old; (3) are conscious and in stable condition and able to complete the questionnaire survey either independently or with the assistance of the researchers; (4) signing an informed consent form to participate in this voluntarily The patients signed the informed consent and voluntarily participated in the study. Exclusion criteria included patients: (1) those with severe psychiatric disorders or aphasia; (2) those with severe physical diseases such as cardiac, pulmonary, and renal diseases; (3) those who are participating in other studies. Based on Sinha’s recommendation, a minimum of 50 subjects per subgroup was needed for accurate model fit in LPA (22). Since there were three profiles in this study, the required sample size should have been at least 150, considering a 20% inefficiency rate. Therefore, the minimum sample size needed was 188. A total of 330 questionnaires were distributed in this study. After excluding invalid responses due to irregular completion patterns, 311 valid questionnaires were recovered, with a valid recovery rate of 94.2%. The sample size was adequate for LPA-based analysis under these conditions. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University (Approval No.2025A-110). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

2.2 Survey tools

2.2.1 Demographic characteristics

The questionnaire developed by the research team through a comprehensive review of the literature and in conjunction with the research objectives and study content of this study, encompassed social demographic data (such as age, gender, literacy level, region of residence, marital status, personal monthly income, medical payment method, primary caregiver) as well as disease-related information including type of stroke, whether it was the first stroke, whether it was a smoking and drinking habit, whether it was comorbid with other chronic diseases, the degree of neurological deficits and recovery (MRS score), and self-care ability (Barthel Index).

2.2.2 Health information-seeking behavior scale

The Health Information-seeking Behavior Scale, developed initially by Zamani et al. (23) and subsequently revised by Sun et al. (24). It has been widely adopted among patients with chronic diseases, comprises 43 items categorized into four dimensions: attitude towards health information-seeking (6 items), information demands (14 items), information sources (15 items), and barriers to acquiring health information (8 items) in the Chinese version. Using the Likert 5-level scoring method, one is very unimportant, and five is very important. The total score ranged from 0 to 215 points, with higher scores indicating a higher level of patients’ health information-seeking behavior. This scale has been validated in Chinese stroke patients. It demonstrates good reliability (25), with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.90. In our study, Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.87.

2.2.3 Behavioral decision-making scale for stroke patients

The Behavioral Decision-making Scale for Stroke Patients was developed by Beilei Lin et al. (26). Specifically designed for stroke patients in China and widely used in this population (26). This scale comprises 30 items distributed across four dimensions: behavior change motivation (10 items), behavior change intention (9 items), decision-making factors (5 items), and decision-making balance (6 items). Each item was rated on a Likert 5-level scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” with scores ranging from 0 to 4 points. The total score ranged from 0 to 150 points, with higher scores indicating a greater level of behavioral decision-making on behalf of stroke patients and facilitating the stimulation of healthy behavioral decision-making and the production of healthy behaviors. The scale’s reliability was good, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.934. In our study, Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.765.

2.3 Data collection method

In this study, the survey subjects were screened in strict accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, with questionnaires administered face-to-face by the trained investigators, and the purpose of the study, content, and filling requirements were explained in detail to the study subjects before the survey to obtain their consent of the patients. For participants with lower educational attainment and older adults, all questionnaire items were read aloud, asked, and recorded by the researcher on a question-by-question basis. Questionnaires were filled out on the spot and recalled for inspection. Data were double-entered and double-checked.

2.4 Statistical method

Mplus 8.3 was used for latent profile analysis of HISB in stroke patients. By using the mean values of the four-dimensional scores of the HISB scale as the manifest indicator, LPA was performed to fit models with 1 to 5 profiles sequentially. Model fit indices included: Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and adjusted BIC (aBIC), as well as Entropy, Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio (LMR), and Bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT). Lower values of AIC, BIC, and aBIC indicated a better fit, while an Entropy value closer to 1 indicated a more precise classification. LMR and BLRT (p < 0.05) suggested that the k models were superior to the k-1 models.

SPSS software (version 27.0) was used to analyze the data. Quantitative data conforming to normal distribution were described by mean ± standard deviation ( ±s), and qualitative data were described by frequency and percentage (%). One-way analysis was performed by chi-squared test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparison between groups of quantitative data, and unordered multicategorical logistic regression analysis was used to analyze influencing factors, with a significance level set at α = 0.05. In addition to p-values, effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported to quantify the magnitude and precision of the observed effects. The regression model adjusted for all statistically significant variables (p < 0.05) in the univariate analysis. This included demographic, clinical, and disease-related factors to control for potential confounding effects.

3 Results

3.1 Results of potential profiling of HISB in stroke patients

Based on the four dimensions’ scores of the health information-seeking behavior of stroke patients, divided into 1 to 5 potential profile models, Table 1 illustrates the possible profiles of the health information-seeking behavior of stroke patients. With the increase in the number of profiles, the values of AIC, BIC, and aBIC gradually decreased, and when three profiles were retained, the score of the Entropy indicator was 0.952. The LMRT and BLRT were statistically significant. Considering the accuracy and parsimony of the model by combining all indicators, model 3 was the best-fitting model, so the health information-seeking behavior of stroke patients was divided into three potential profiles.

Table 1. Fitting index for the latent profile model of the health information-seeking behavior in stroke patients.

3.2 Nomenclature and characterization of potential profiles of HISB in stroke patients

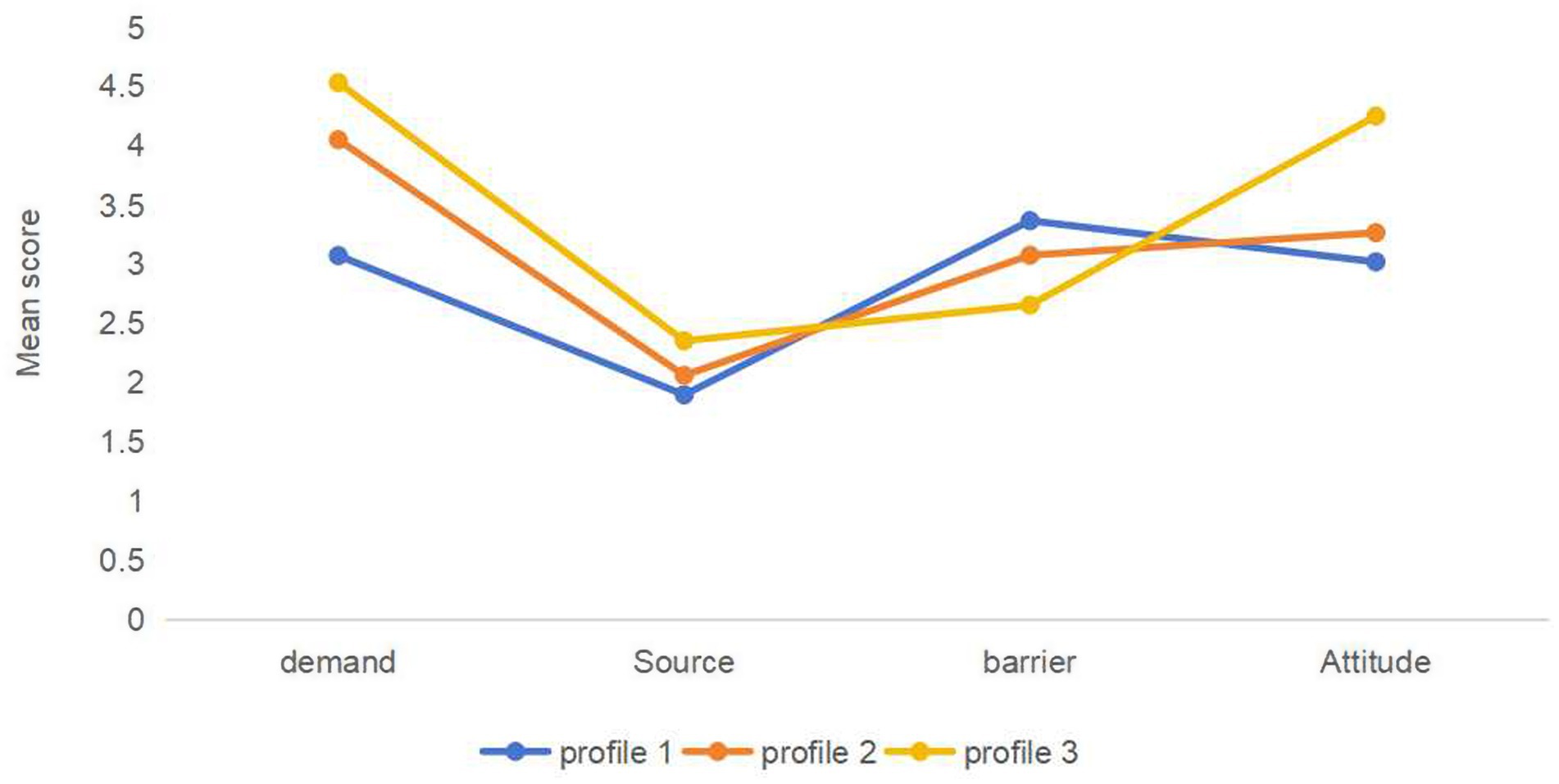

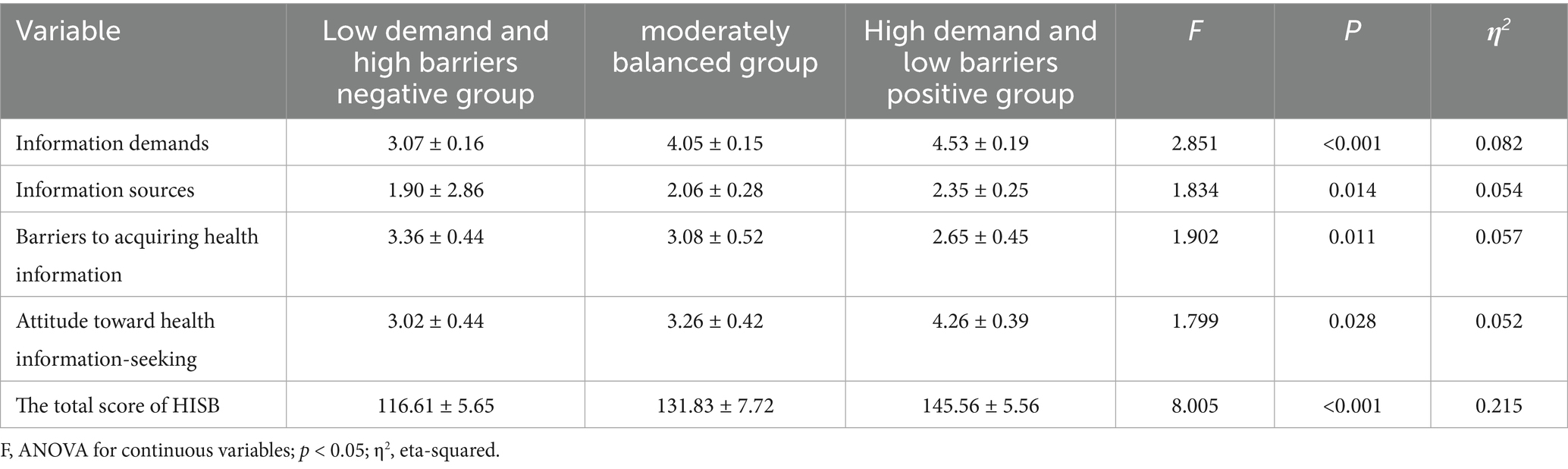

According to the scores on the four dimensions of the Health Information-seeking Behavior Scale (HISB) for the three profiles of stroke patients, it is clear that they showed different response characteristics, as shown in Figure 1. Stroke patients in profile 1 had low scores on the dimensions of information-seeking demands, sources, and attitudes, and the highest scores on the dimension of barriers to access. Accordingly, this category was named the “low demand and high barrier negative group,” with 62 cases (19.9%). Profile 2 had moderate scores in all dimensions, so it was named the “moderately balanced group,” with a total of 183 cases (59.1%). Stroke patients in profile 3 had the highest scores in information-seeking demands, sources, and attitudes, and the lowest in the dimensions of barriers to information-seeking. Thus, this category was termed the “high demand and low barrier positive group,” with 66 cases (21%), as shown in Table 2.

3.3 Univariate analysis of factors influencing potential HISB profiles in stroke patients

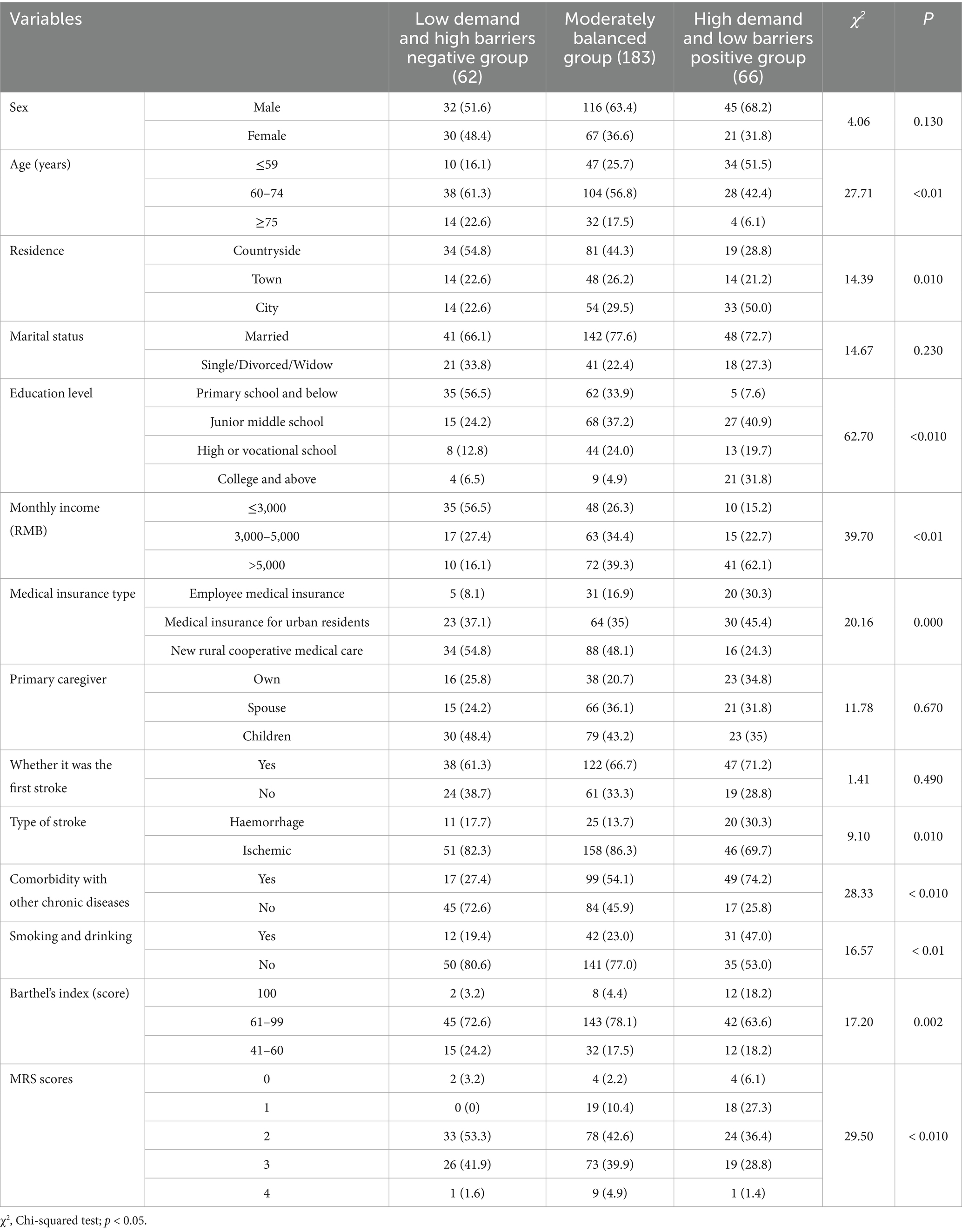

Differences in health information-seeking behaviors among different potential profiles of stroke patients were statistically significant (p < 0.05) in the distributions of age, region of residence, literacy level, monthly personal income, method of payment for medical care, type of stroke, Barthel Index, and MRS scores across the three potential profiles, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Univariate analysis of factors influencing the potential profile of HISB in stroke patients.

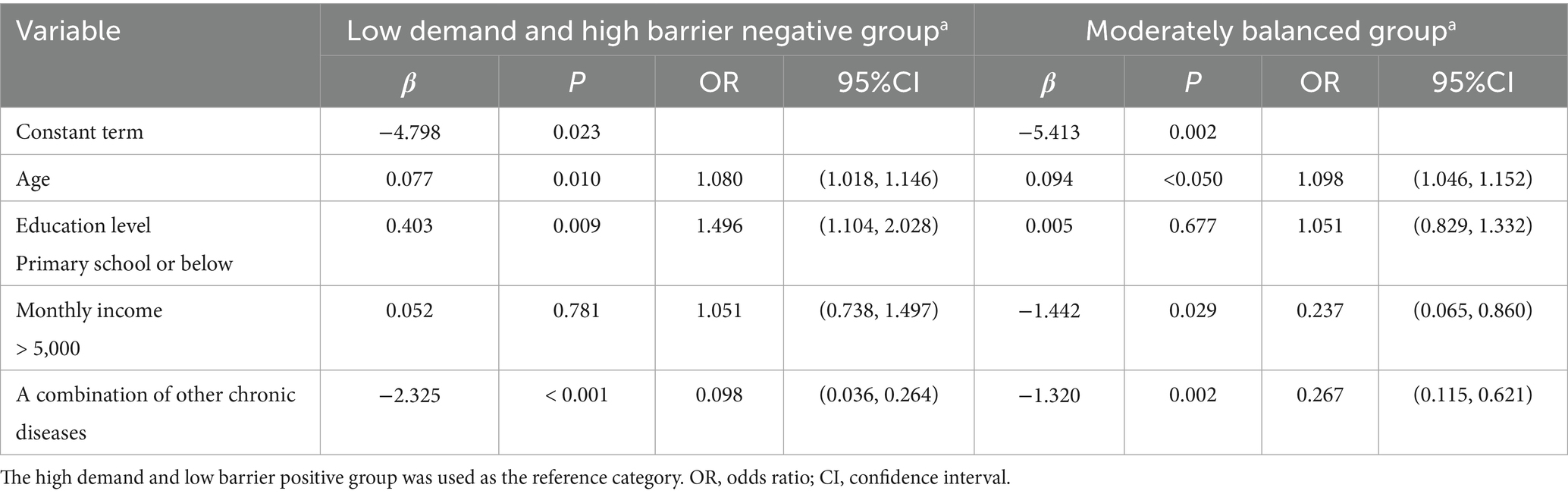

3.4 Multifactorial analysis of factors influencing potential HISB profiles in stroke patients

An unordered multicategorical logistic regression was performed with the three potential profiles of health information-seeking behavior of stroke patients as dependent variables (low demand and high barrier negative group = 1, moderately balanced group = 2, high demand and low barrier positive group = 3) with variables that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis as independent variables. The independent variables were assigned: literacy level: Primary school and below = 1, Junior middle school = 2, High or vocational school = 3, college and above = 4; personal monthly income: <3,000 = 1, 3,000–5,000 = 2, >5,000 = 3; and whether or not to comorbid with other chronic diseases: yes = 1, no = 2. The results showed that age, literacy level, personal monthly income, and whether or not to be comorbid with other chronic diseases were the different potential profiles of the significant influencing factors (p < 0.05), see Table 4.

Table 4. Multivariate logistic regression analysis on the latent profile of HISB in stroke patients.

3.5 Relationship between HISB latent profiles and health behavior decision-making in stroke patients

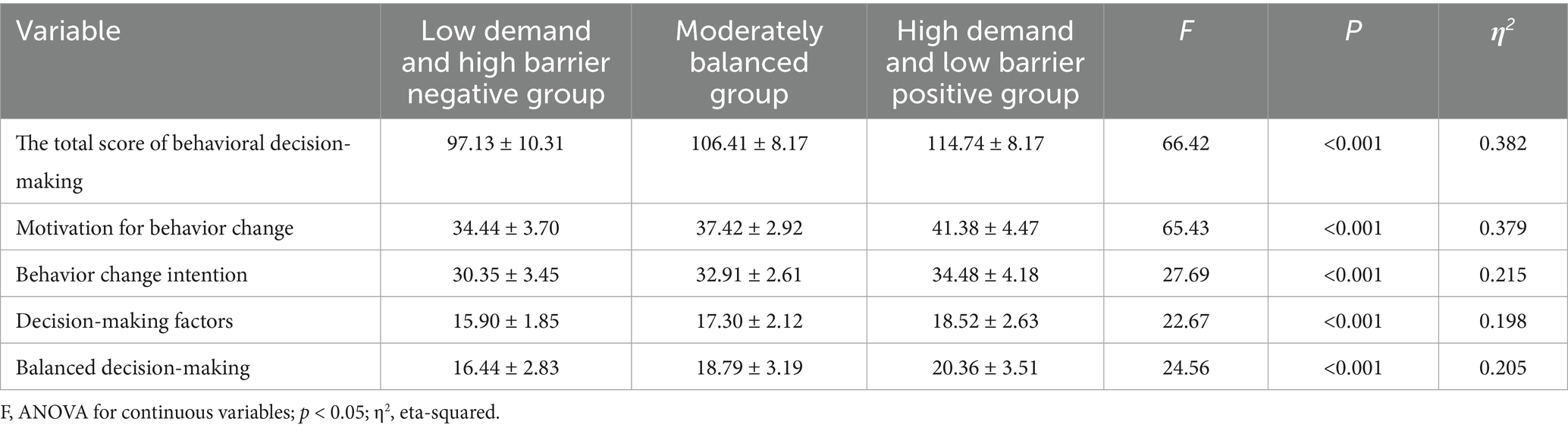

The results of ANOVA showed that the differences between different potential profiles of HISB in stroke patients were statistically significant in motivation to change behavior, intention to change behavior, decision-making factors, and decision-making balance (p < 0.001), as shown in Table 5.

4 Discussion

4.1 Heterogeneity in health information-seeking behavior among stroke patients

Health information-seeking behavior, also known as health information query behavior and health information search behavior, refers to individuals seeking information about health, risk, disease, and health protection in specific events or situations (27). In this study, we found that the total score of health information-seeking behavior of stroke patients was (131.71 ± 11.58), which was at a low level, slightly lower than the results of the related study by Yufan et al. (25). This may be related to the fact that most of the study subjects included in this study were elderly patients in the more economically backward areas of Northwest China, and that due to the limitations of physical function and cognitive level, the elderly have relatively limited ability and channels to obtain information and low comprehension of information (28). Health information-seeking behaviors among stroke patients exhibit group heterogeneity. Among them, 21.1% of the patients’ health information-seeking behavior was high. The patients had a strong demand for disease knowledge, rehabilitation skills, and other information, and a positive attitude toward acquiring knowledge; and the barriers to accessing information sources were relatively low. The patients alleviated the uncertainty of the disease by seeking a high demand for information to improve their self-efficacy, which is consistent with the viewpoint that “a sense of information mastery promotes proactive participation” in the theory of health empowerment (29). This is consistent with the idea that “information mastery promotes active participation” in health empowerment theory (29). It may be related to the fact that patients in this category are mainly concentrated in the middle-aged (≤59 years old) and higher education (high school/secondary school and above) groups, which generally have a higher level of health literacy and a greater ability to learn and cognitively perceive specialised medical knowledge. The majority of patients (59.9%) were at the moderately balanced level, which may be because the patients in this profile were concentrated in the age group of 60–74 years old, and their education was mainly in junior high school, so their knowledge learning ability and seeking of information and cognitive comprehension were limited. 19.9% of patients were in the low-demand, high-barrier, and negative group, characterised by negative attitudes toward the disease and a significant limitation in their demand. This group may have been affected by cognitive bias toward the disease or inadequate health literacy due to their old age; however, their health literacy was generally high. They may be affected by disease cognitive bias or health literacy, and have high barriers to information-seeking due to their age, low literacy level, and a single source of information seeking channels, suggesting that clinical healthcare professionals need to identify the differences in the nursing care needs of different categories of the population as early as possible and implement personalized nursing care interventions to improve the level of patients’ health information-seeking behaviors.

4.2 Factors influencing different potential profiles of HISB in stroke patients

The results of this study indicate that older and less educated patients are more likely to be categorized into the low-demand, high-barrier negative group. Analyzing the reasons, younger patients tend to have higher health awareness and treatment compliance. They are more active in communicating with the outside world to obtain help and enhance their understanding of disease information. Older adults often experience age-related cognitive and psychological changes, manifested as declines in work capacity, memory, and information processing speed, which can diminish their ability to absorb complex health information. Additionally, elderly patients may exhibit lower self-efficacy and greater technophobia when navigating the healthcare system, further inhibiting proactive information-seeking behaviors (30). Patients with higher literacy levels are more inclined to proactively acquire health information. First, their educational background furnishes them with superior cognitive resources, including enhanced health literacy and comprehension of medical terminology, which lowers the cognitive barrier to processing complex information (31). Beyond this, Education can foster forward-thinking health concepts and enhance self-efficacy, thereby stimulating the intrinsic motivation to manage one’s health proactively (32). In addition, the advantage of digital literacy brought by an educational background also increased their efficiency in utilizing smart devices and reducing technical barriers to information access (33). It is suggested that healthcare professionals should pay attention to the level of information-seeking behaviors of elderly and low-education patients, guide their families to help them communicate with healthcare professionals about their conditions and participate in medical decision-making, and adopt an easy-to-understand approach to inform patients about their conditions and treatments to make it easier for them to understand.

The results of this study showed that patients with a personal monthly income of more than 5,000 yuan were more likely to be categorized as high-demand, low-barrier positive group, probably because the higher the income level, the higher the level of economic capital, educational advantages, social network, and medical accessibility (34). Higher income provides access to broader social networks, which serve as channels for obtaining health information. Furthermore, income inequality creates disparities in exposure to health information, with higher-income individuals more frequently engaging with health-literate social circles and health management programs. Beyond this tangible resource, greater economic resources typically experience enhanced psychological security, which reduces the cognitive burden associated with health concerns and frees up mental resources for information seeking (35). Therefore, healthcare professionals should pay attention to the assessment of patients’ economic level, pay attention to low-income patients’ demands for health information and access to health information, develop concise health education tools covering disease awareness and rehabilitation guidance, and instruct them to master basic information retrieval skills and enhance patients’ ability to obtain health information by optimizing the comprehensibility and ease of operation of the educational content.

The results of this study showed that the greater the likelihood that patients with comorbid chronic diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes, would be categorized as moderately well-balanced and high-demand low-barrier active, similar to the results of Wang et al. (36). The reason may be that, First, the comorbid state forces patients to manage multiple health problems simultaneously, and the demand for health information is more urgent, which leads to active interdisciplinary access to health-related information to optimize decision-making. Second, patients with chronic diseases have developed habits of regular monitoring and medication adjustments (37). Their long-term management experience enhances their information efficacy. Their self-efficacy supports the screening and application of complex information, while stroke events further catalyze patients’ demand for systematic knowledge (38). Third, patients with comorbidities of other chronic diseases were more likely to have access to professional guidance due to frequent doctor visits, and the advantage of resource utilization was more pronounced, which could significantly reduce their barriers to information seeking (39). This suggests that healthcare workers should dynamically assess the changes in information demands of different patients, pay more attention to patients with lower levels of health information-seeking behavior, and strengthen publicity and guidance. For patients with higher levels of health information-seeking behavior, systematic and interdisciplinary integrated knowledge services should be provided.

4.3 Relationship between different potential profiles of HISB and health behavior decisions in stroke patients

This study revealed that stroke patients with varying potential profiles demonstrated significant differences in health behavior decision-making and related dimensions. Patients with high-demand, low-barrier positive profiles showed optimal health behavior decision-making ability, demonstrated higher initiative and adaptability in health behavior change, and perceived fewer external barriers, which may be attributed to the fact that patients with strong demand are more inclined to explore information proactively (40), and those with positive attitudes are more willing to invest time and energy in understanding the information, which in turn translates into concrete actions (41). This positive information-seeking tendency leads to a greater likelihood of forming clear behavioral intentions and translating them into actual actions, which is conducive to the prognosis of the disease (42). In contrast, negative patients with low demands and high barriers may be limited by insufficient motivation or limited sources of information seeking, which interferes with the patient’s comprehensive assessment of decision-making, thus affecting the quality of health behavioral decision-making and facing greater resistance to behavioral change, and consequently, involving the implementation of the overall health behaviors (43). Moderately balanced patients fall between extremes, and multifactorial dynamics may influence their behavioral decisions. This difference in typology underscores the demand for individualized strategies in clinical interventions. Clinical staff can focus on continuously optimizing information supply and providing positive feedback reinforcement for patients with high demand and low barriers.

In contrast, patients with low demand and negative obstacles require strengthening motivational and cognitive interventions, enhancing their health information sensitivity through motivational interviews and health writing, and systematically addressing challenges at the environmental and social support levels. The systematic reduction of ecological and social support barriers. In this way, we can more effectively improve the health information-seeking behavior of stroke patients, stimulate health behavior decision-making, and promote the formation and maintenance of health behaviors.

4.4 Implications for clinical practice and health policy

By identifying three distinct latent profiles of HISB, this study provides critical evidence for developing targeted patient education and support strategies. Clinically, interventions must be tailored to each profile: For the high demand and low barrier positive group, healthcare professionals should deliver systematic, in-depth, and multidisciplinary health information to satisfy their strong initiative and reinforce their already optimized health behavior decision-making capacity. For the moderately balanced group, standardized health education programs centered on foundational knowledge and skill development are essential to effectively enhance their information efficacy. Most critically, interventions for the low demand and high barrier negative group, typically older, less educated, and lower-income patients, should combine motivational interviewing to overcome negative attitudes, simplify health materials for improved comprehension, and actively engage family or caregivers to bridge the information gap (44). To systematically support these tailored interventions, future policy measures could include integrating health literacy assessments into routine clinical care, developing tiered health education resources, enhancing training for primary healthcare workers, and promoting the establishment of integrated information support networks linking hospitals, communities, and households (45). Furthermore, given that factors like age, education level, income, and comorbidities significantly influence health information-seeking patterns, screening for these characteristics upon admission enables early identification of high-risk patients. Ultimately, behavior-based interventions that remove barriers and cultivate proactive information-seeking mindsets will effectively promote healthier behavioral decisions, thereby accelerating functional recovery and reducing stroke recurrence rates among stroke patients.

5 Limitations and future research

This study had some limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, the reliance on self-reported measures is susceptible to reporting biases, such as social desirability and recall bias, which may affect the accuracy of the data on health information-seeking behavior and decision-making. Secondly, the cross-sectional design precludes the determination of causal relationships between the identified latent profiles, their predictors, and health behavior decision-making. Lastly, the relatively small sample size limits the representativeness of the findings and thus constrains the generalizability of the results. Future research should employ longitudinal or mixed-methods designs with multi-center, increase the sample size, randomized sampling strategies to validate the identified profiles, explore their stability over time, and establish causal pathways. Additionally, incorporating objective measures of health information-seeking could complement self-reported data and provide a more comprehensive understanding.

6 Conclusion

This study reveals significant group heterogeneity in health information-seeking behaviors among stroke patients and explores the relationship between their underlying profiles and health behavior decision-making. These findings can guide clinicians in designing precision education or intervention programs tailored to specific patient subgroups. Shifting clinical practice from standardized education to precision-targeted interventions, this strategy constructs an effective pathway for health information to guide rational decision-making, ultimately promoting the formation and maintenance of health.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Lanzhou University Second Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

Zr-Z: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. MY: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Supervision. Jj-F: Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Ym-L: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Jp-Z: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Wp-L: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Xl-W: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Xm-D: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The study was supported by the “Gansu Province Joint Fund-General Project” (grant no. 24JRRA925), “Gansu Province Health Industry Plan Project” (grant no. GSWGHL2023-17), and “Gansu Province Healthcare Industry Research Project” (grant no. GSWSQN2024-06).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate all the beneficial comments from our instructor and research group members. We thank the participants for their valuable contributions to the data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Feigin, VL, Abate, MD, Abate, YH, Abd ElHafeez, S, Abd-Allah, F, Abdelalim, A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Neurol. (2024) 23:973–1003. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(24)00369-7

2. Tu, WJ, and Wang, LD. China stroke surveillance report 2021. Mil Med Res. (2023) 10:33. doi: 10.1186/s40779-023-00463-x

3. Yao, M, Ren, Y, Jia, Y, Xu, J, Wang, Y, Zou, K, et al. Projected burden of stroke in China through 2050. Chin Med J. (2023) 136:1598–605. doi: 10.1097/cm9.0000000000002060

4. Yusuf, S, Joseph, P, Rangarajan, S, Islam, S, Mente, A, Hystad, P, et al. Modifiable risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 155 722 individuals from 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. (2020) 395:795–808. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32008-2

5. Bam, K, Olaiya, MT, Cadilhac, DA, Donnan, GA, Murphy, L, and Kilkenny, MF. Enhancing primary stroke prevention: a combination approach. Lancet Public Health. (2022) 7:e721–4. doi: 10.1016/s2468-2667(22)00156-6

6. Feigin, VL, and Owolabi, MO. Pragmatic solutions to reduce the global burden of stroke: a world stroke organization-lancet neurology commission. Lancet Neurol. (2023) 22:1160–206. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(23)00277-6

7. Feigin, VL, Brainin, M, Norrving, B, Martins, SO, Pandian, J, Lindsay, P, et al. World stroke organization: global stroke fact sheet 2025. Int J Stroke. (2025) 20:132–44. doi: 10.1177/17474930241308142

8. Wang, J, Zhao, CX, Tian, J, Li, YR, Ma, KF, Du, R, et al. Effect of hospital-community-home collaborative health management on symptoms, cognition, anxiety, and depression in high-risk individuals for stroke. World J Psychiatry. (2025) 15:99152. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i3.99152

9. Rao, N, Tighe, EL, and Feinberg, I. The dispersion of health information-seeking behavior and health literacy in a state in the southern United States: cross-sectional study. JMIR Form Res. (2022) 6:e34708. doi: 10.2196/34708

10. Andreadis, K, Buderer, N, and Langford, AT. Patients' understanding of health information in online medical records and patient portals: analysis of the 2022 health information National Trends Survey. J Med Internet Res. (2025) 27:e62696. doi: 10.2196/62696

11. Beilei, L, Yujia, J, and Yongxia, M. Preliminary construction of recurrence risk perception and Behavioral decision model in stroke patients. Military. Nursing. (2024) 41:1–5. doi: 10.3969/i.issn.2097-1826.2024.06.001

12. Antonio, MG, Williamson, A, Kameswaran, V, Beals, A, Ankrah, E, Goulet, S, et al. Targeting patients' cognitive load for telehealth video visits through student-delivered helping sessions at a United States federally qualified health Center: equity-focused, mixed methods pilot intervention study. J Med Internet Res. (2023) 25:e42586. doi: 10.2196/42586

13. Helbach, J, Hoffmann, F, Hecht, N, Heesen, C, Thomalla, G, Wilfling, D, et al. Information needs of people who have suffered a stroke or TIA and their preferred approaches of receiving health information: a scoping review. Eur Stroke J. (2024):23969873241272744. doi: 10.1177/23969873241272744

14. Ansari, A, Fahimfar, N, Noruzi, A, Fahimifar, S, Hajivalizadeh, F, Ostovar, A, et al. Health information-seeking behavior and self-care in women with osteoporosis: a qualitative study. Arch Osteoporos. (2021) 16:78. doi: 10.1007/s11657-021-00923-8

15. Hu, Y, Qiu, X, Ji, C, Wang, F, He, M, He, L, et al. Post-stroke experiences and health information needs among Chinese elderly ischemic stroke survivors in the internet environment: a qualitative study. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:1150369. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1150369

16. Zeng, M, Liu, Y, He, Y, and Huang, W. Relationship between stroke knowledge, health information literacy, and health self-management among patients with stroke: Multicenter cross-sectional study. JMIR Med Inform. (2025) 13:e63956. doi: 10.2196/63956

17. Liu, F, Kong, X, Xia, T, and Guo, H. Exploring the impact of discharged patients' characteristics on online health information-seeking behaviors: insights from patients' dilemmas. Front Psychol. (2025) 16:1500627. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1500627

18. Rong, H, Lu, L, He, M, Guo, T, Li, X, Tao, Q, et al. Online health information-seeking Behaviors among the Chongqing population: cross-sectional questionnaire study. JMIR Form Res. (2025) 9:e56028. doi: 10.2196/56028

19. Shi, G, Yu, J, Zhang, J, Zhao, J, Peng, Z, and Shang, L. Factors affecting online health information-seeking behavior in young and middle-aged patients with stroke. PLoS One. (2025) 20:e0321791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0321791

20. Yang, Q, Zhao, A, Lee, C, Wang, X, Vorderstrasse, A, and Wolever, RQ. Latent profile/class analysis identifying differentiated intervention effects. Nurs Res. (2022) 71:394–403. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000597

21. D, LW. Updated key points and interpretation of Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute intracerebral hemorrhage, 2019. Cardio-cerebrovascular Disease Prevention Treatment. (2021) 21:13–7. doi: 10.3969/i.issn.1009-816x.2022.04.002

22. Sinha, P, Calfee, CS, and Delucchi, KL. Practitioner's guide to latent class analysis: methodological considerations and common pitfalls. Crit Care Med. (2021) 49:e63–79. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000004710

23. Zamani, M, Soleymani, MR, Afshar, M, Shahrzadi, L, and Zadeh, AH. Information-seeking behavior of cardiovascular disease patients in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences hospitals. J Educ Health Promot. (2014) 3:83. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.139249

24. Sun, Q, Zhou, W, and Zhang, Y. Investigation and analysis of health information-seeking behavior among patients with chronic disease. J Nurs Sci. (2019) 34:84–6. doi: 10.3870/i.issn.1001-4152.2019.09.084

25. Yufan, H, Lei, H, Dy, J, Cuiling, PY, and Lu, C. Analysis of factors and paths influencing the health information-seeking behavior of stroke patients. J Nurs Adm. (2024) 24:201–5. doi: 10.3969/i.issn.1671-315x.2024.03.004

26. Beilei, L, Zhenxiang, Z, and Yongxia, M. Development and psychometric test of the Behavioral decision-making scale for stroke patients. Chin J Nurs. (2022) 57:1605–10. doi: 10.3761/i.issn.0254-1769.2022.13.011

27. Song, M, Elson, J, Haas, C, Obasi, SN, Sun, X, and Bastola, D. The effects of patients' health information Behaviors on shared decision-making: evaluating the role of Patients' Trust in physicians. Healthcare. (2025) 13:11. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13111238

28. Zhang, C, Mohamad, E, Azlan, AA, Wu, A, Ma, Y, and Qi, Y. Social media and eHealth literacy among older adults: systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res. (2025) 27:e66058. doi: 10.2196/66058

29. Li, H, Gan, L, Sun, Y, and Yu, HT. A randomized controlled study on systematic nursing care based on health empowerment theory and its effect on the self-care and functional abilities of patients with spinal fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. (2023) 18:821. doi: 10.1186/s13018-023-04317-z

30. Xin, X, Liu, Q, Jia, S, Li, S, Wang, P, Wang, X, et al. Correlation of muscle strength, information processing speed, and cognitive function in the elderly with cognitive impairment--evidence from EEG. Front Aging Neurosci. (2025) 17:1496725. doi: 10.3389/fnagi2025.1496725

31. Aihemaiti, Y, Li, Z, Tong, Y, Ma, L, and Li, F. Influence of health literacy and self-management on quality of life among older adults with hypertension and diabetes in Northwest China. Exp Gerontol. (2025) 206:112776. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2025.112776

32. Li, R, Zhu, D, and Tan, Z. The effects of self-management education on self-efficacy, self-esteem, and health behaviors among patients with stroke. Medicine. (2025) 104:e40758. doi: 10.1097/md0000000000040758

33. Cho, MK, Han, A, Lee, H, Choi, J, Lee, H, and Kim, H. Current status of information and communication technologies utilization, education needs, Mobile health literacy, and self-care education needs of a population of stroke patients. Healthcare (Basel). (2025) 13. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13101183

34. Beasant, B, Anderson, K, Lee, G, Lotfaliany, M, Tembo, M, McCoombe, S, et al. Health literacy and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a scoping review. Public Health Rep. (2025):333549251322649. doi: 10.1177/00333549251322649

35. Baute, S. Health inequality attributions and support for healthcare policy. Soc Sci Med. (1982) 2025:117946. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2025.117946

36. Wang, J. Connotation and improvement strategies of the sense of gain in health Management for Chronic Disease Patients in China. Med Soc. (2024) 37:97–102. doi: 10.13723/j.yxysh.2024.10.015

37. Huang, Y, Li, S, Lu, X, Chen, W, and Zhang, Y. The effect of self-management on patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel). (2024) 12:2151. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12212151

38. Clancy, B, Bonevski, B, English, C, and Guillaumier, A. The online health information-seeking Behaviors of people who have experienced stroke: qualitative interview study. JMIR Form Res. (2024) 8:e54827. doi: 10.2196/54827

39. Ma, YY, Wu, TT, Wang, L, Qian, YF, Wu, J, and Geng, GL. Determinants of transitional care utilization among older adults with chronic diseases: An analysis based on Andersen's Behavioral model. Clin Interv Aging. (2025) 20:349–67. doi: 10.2147/cia.S490166

40. Zhang, L, and Jiang, S. Linking health information seeking to patient-centered communication and healthy lifestyles: an exploratory study in China. Health Educ Res. (2021) 36:248–60. doi: 10.1093/her/cyab005

41. Zhao, YC, Zhao, M, and Song, S. Online health information seeking among patients with chronic conditions: integrating the health belief model and social support theory. J Med Internet Res. (2022) 24:e42447. doi: 10.2196/42447

42. Liu, D, Yang, S, Cheng, CY, Cai, L, and Su, J. Online health information seeking, eHealth literacy, and health Behaviors among Chinese internet users: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. (2024) 26:e54135. doi: 10.2196/54135

43. Wang, X, Jiang, H, Zhao, Z, Kevine, NT, An, B, Ping, Z, et al. Mediation role of Behavioral decision-making between self-efficacy and self-management among elderly stroke survivors in China: cross-sectional study. Healthcare (Basel). (2025) 13:704. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13070704

44. Wang, Q, Xin, X, and Li, X. Latent profile analysis for patient activation in patients with essential hypertension. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2025) 19:2635–45. doi: 10.2147/ppa.S524968

Keywords: stroke, health information-seeking behavior, behavioral decision-making, influencing factors, latent profile analysis

Citation: Zhao Z-r, Yang M, Feng J-j, Lan Y-m, Zhong J-p, Li W-p, Wang X-l and Dou X-m (2025) Health information-seeking behavior in stroke patients and its relationship with Behavioral decision-making: a latent profile analysis. Front. Neurol. 16:1683198. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1683198

Edited by:

Aleksandras Vilionskis, Vilnius University, LithuaniaReviewed by:

Ira Suarilah, Airlangga University, IndonesiaRami Elshatarat, Taibah University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2025 Zhao, Yang, Feng, Lan, Zhong, Li, Wang and Dou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xin-man Dou, ZG91eG1AbHp1LmVkdS5jbg==

Ze-run Zhao

Ze-run Zhao Meng Yang1

Meng Yang1 Xin-man Dou

Xin-man Dou