- Department of Neurology, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is a debilitating neuroimmune condition characterized by recurrent inflammatory episodes that result in progressive disability, substantial psychological distress, and significant economic burdens. While current immunosuppressive therapies reduce relapse rates, they fail to achieve a definitive cure. Cellular therapy has emerged as a novel therapeutic strategy, offering potential disease modification through immune cell modulation and immune system reorganization via in vivo transplantation of adult stem cells or genetically engineered somatic cells. This review synthesizes recent advancements in cellular therapy for NMOSD, aiming to improve understanding of it in NMOSD disease and provide a roadmap for future research.

1 Introduction

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), first described by Eugène Devic in 1894 and historically termed Devic’s disease, is a neuroimmune demyelinating disorder characterized by recurrent inflammatory attacks predominantly targeting the optic nerves and spinal cord (1). The prevalence of this disease exhibits considerable geographic variation, being highest in Africa and lowest among Caucasian populations. Incidence rates also differ across age groups, with adult prevalence ranging from 0.34 to 10 per 100,000, compared to 0.06 to 0.22 per 100,000 in pediatric populations (2). Notably, the female-to-male prevalence ratio ranges from 2.3 to 7.6 times higher in women among both Caucasian and African ethnic groups. Regional disparities in mortality rates have been documented, though comprehensive global studies remain unavailable (3, 4). Relapses of the disease lead to cumulative neurological disability, severely compromising patients’ quality of life and imposing profound socioeconomic burdens on affected individuals and their families, even increasing the risk of death (4, 5). Current therapeutic strategies rely on immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, inebilizumab, and satralizumab to mitigate relapse frequency (6, 7). However, these treatments fail to achieve complete remission, with observational studies reporting that nearly 50% of NMOSD patients experience one or more relapses despite adherence to immunosuppressive regimens (8). Current medications only suppress the immune system, target specific pathological pathways, or decrease the production of pathogenic antibodies; however, they do not inhibit the disease at its origin (9). Consequently, there is a need to develop drugs or modulatory therapies that can target the very early stages of the disease, which could potentially lead to a cure for individuals at the biological stage of the disease or offer preventive treatment for those at risk. Furthermore, approaches that can restore the dysregulated immune system are also necessary.

Cellular therapy has emerged as a promising frontier in immune-mediated disorders (10). Adult stem cells—including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and neural stem cells—have demonstrated therapeutic potential in preclinical and clinical studies of autoimmune diseases (11–14). For instance, HSC transplantation and MSC infusion have shown efficacy in resetting dysregulated immune responses and promoting tissue repair in multiple sclerosis (15, 16). Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has shown a higher rate of disability improvement in the treatment of active relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis and is more effective in preventing relapses compared to other immune-modulating treatments (17–19). Also, genetically modified chimeric antigen receptor T cells, utilizing gene editing techniques, have achieved impressive results in the treatment of the disease, providing hope for a cure for patients suffering from immune disorders (20–22). Building on these advances, this review synthesizes recent progress in cellular therapy for NMOSD, with a focus on clinical applications and challenges (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The mechanism of action of different cell therapies in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. T lymphocytes derived from allogeneic or autologous sources are genetically modified to become CD19-targeting T cells (CAR-T). Following ex vivo expansion, these engineered cells are reinfused into the patient, where they specifically identify and eliminate CD19-positive B lymphocytes and antibody-secreting plasma cells. A subset of these cells further differentiates into memory T lymphocytes, thereby mediating long-term immunosurveillance. Autologous hematopoietic stem cells are reinfused into the myeloblast host, where they differentiate into new immune cells and reconstitute the immune system. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells exert neuroprotective effects via the secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-21, and/or through the modulation of T follicular helper (Tfh) lymphocytes. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells act on astrocytes to ameliorate blood–brain barrier injury. Additionally, they secrete MFGE8, which inhibits immune-induced NF-κB activation and reduces the release of pro-inflammatory factors, thereby attenuating inflammatory infiltration and protecting motor neurons from damage.

2 Adult stem cell therapy

2.1 Autologous hematopoietic stem cells

Hematopoietic stem cells play a crucial role in disease treatment due to their ease of acquisition and well-established extraction and preservation techniques. Based on their source, hematopoietic stem cells can be classified as autologous or allogeneic. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a therapeutic approach that involves removing abnormal cells from the body through radiotherapy or chemotherapy, followed by the infusion of the patient’s own or another person’s hematopoietic stem cells to restore normal hematopoietic and immune functions. In this manner, the disease can be cured by eliminating defective inflammatory responses and immune cells from the autoimmune system and establishing a self-tolerant immune system. Autologous hematopoietic stem cells are popular for many diseases due to the absence of autoimmune rejection.

In multiple sclerosis (MS), HSCT has been demonstrated to be effective in preventing relapses and reducing disease severity in a relatively safe and cost-effective manner (18, 23). A follow-up study found that HSCT treatment improved disability, reduced relapse rates, and thus enhanced the quality of life in patients with NMOSD (24). The conversion to negative AQP4 antibodies after treatment may indicate that patients can remain free of immunosuppressive drugs for an extended period, potentially related to the immune reconstitution of the organism. AHSCT is capable of reconstituting the repertoire of self-tolerant T and B lymphocytes, thereby rebuilding the immune system and altering the inflammatory milieu (25). However, the precise characteristics of immune reconstitution following AHSCT in patients with NMOSD remain poorly characterized. Given the remodeling role of AHSCT in immune disorders, Koh Yeow Hoay proposed that AHSCT could serve as an alternative therapy to conventional immunotherapy in patients with severe NMOSD, providing an option for those who have difficulty receiving conventional immunotherapy (26). Autologous peripheral hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may also contribute to reducing the frequency of neuromyelitis optica attacks (27). However, unlike malignant hematologic diseases, NMOSD may recur at a later time point despite transient remission after AHSCT treatment for NMOSD, which aligns with the description provided by Joachim Burman et al. (28, 29). AHSCT treatment rebuilds the immune system and offers hope for curing the disease, but the presence of complications should not be overlooked, such as fever, infection, hematopenia, and secondary autoimmune diseases (30–32). Similar complications can be observed in multiple sclerosis (33). Meanwhile, most of the current studies on the role of AHSCT in the treatment of NMOSD have been conducted in adults, and the therapeutic value in pediatric NMOSD remains to be further determined (34–36). These factors restrict the broader utilization of hematopoietic stem cells in clinical settings. Overall, the effectiveness of AHSCT therapy in patients with NMOSD represents a therapeutic alternative worthy of consideration, particularly for patients experiencing recurrent or refractory NMOSD (26, 32, 37, 38). Future studies will focus on large-sample, multicenter data collection and clarifying the therapeutic dose of hematopoietic stem cells in NMOSD.

2.2 Mesenchymal stem cells

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation involves the isolation of MSCs from donor tissues, followed by in vitro expansion, purification, and subsequent reintroduction into patients to modulate disease pathology. As multipotent stromal cells, MSCs exhibit robust differentiation capacity, self-renewal potential, and paracrine activity mediated through cytokine secretion, T lymphocytes to suppress proliferation, and extracellular vesicle release (39–41). Critically, MSCs demonstrate low immunogenicity due to minimal MHC class I expression, alongside advantages such as abundant tissue sources (e.g., bone marrow, umbilical cord, placental tissue, adipose) and absence of ethical controversies, rendering them widely utilized in regenerative and immunomodulatory therapies (42, 43). These properties position MSC-based therapies as a promising strategy for immune reconstitution in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), particularly in recalcitrant cases unresponsive to conventional immunosuppression.

2.2.1 Human umbilical cord- derived mesenchymal stem cells

Emerging evidence suggests that human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs) exhibit therapeutic potential in ameliorating clinical signs and symptoms of NMOSD without reported adverse effects (44). A 10-year longitudinal follow-up study further corroborated the safety and feasibility of combined intravenous and intrathecal (IT) administration of hUC-MSCs, with no severe treatment-related complications documented (45). Short-term clinical evaluations have additionally confirmed the efficacy and favorable safety profile of hUC-MSCs in managing severe NMOSD cases (46). A prospective multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial systematically investigated hUC-MSC-based therapy for NMOSD, providing robust evidence for its clinical safety and therapeutic efficacy while establishing critical groundwork for optimizing stem cell dosing protocols (47). In the animal model of NMOSD, treatment with hUC-MSCs was observed to improve dyskinesia by inhibiting astrocyte injury mediated by AQP4 antibodies and complement, attenuating inflammatory infiltration of the spinal cord, and reducing damage to the blood–brain barrier (48). Furthermore, hUC-MSCs secrete MFGE8, which interacts with the ITGB3 receptor on astrocytes. This ligand-receptor binding inhibits immune-induced NF-κB activation and reduces the release of pro-inflammatory factors, thereby protecting motor neurons from damage and ameliorating motor deficits (49).

2.2.2 Bone marrow marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells

Bone marrow serves as a primary source of mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs), which have demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in hematologic disorders. In the NMOSD, BM-MSC therapy may reduce disease relapse rates and mitigate neurological disability. A two-year prospective observational study established that BM-MSC administration promotes structural restoration of the optic nerve and spinal cord in NMOSD patients, with sustained clinical benefits observed during follow-up (50). Mechanistic studies suggest that BM-MSCs mediate neuroprotection via immunomodulatory effects on T follicular helper (Tfh) cells and suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and IL-21. Intriguingly, systemic absorption of MSCs through pressure ulcer sites has been proposed as an alternative delivery mechanism (51). However, BM-MSCs isolated from NMOSD patients exhibit intrinsic limitations, characterized by reduced proliferative capacity and accelerated senescence compared to healthy donor-derived counterparts (52). Furthermore, allogeneic BM-MSCs lack immune privilege and may trigger both humoral and cellular immune responses, potentially leading to treatment-related complications (53). These constraints highlight challenges in optimizing BM-MSC-based therapies for NMOSD. Exosomes derived from BM-MSCs represent a promising therapeutic strategy. Studies demonstrate their efficacy in promoting neural stem cell proliferation in spinal cord ischemia–reperfusion injury models (54). Moreover, in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) models, they ameliorate central nervous system inflammation and demyelination, potentially via modulating microglial polarization or directly targeting oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Nevertheless, their therapeutic potential for NMOSD requires further investigation (55).

2.2.3 Limitations of mesenchymal stem cell therapy

Despite the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in NMOSD, the translation of laboratory findings to clinical applications encounters considerable challenges, including immunocompatibility, stability, heterogeneity, differentiation capacity, and migratory efficiency (56). Systemic infusion of MSCs may elicit severe adverse effects, such as thrombosis and embolism, especially with MSCs derived from non-bone marrow sources (57). To date, limited data are available on MSC-related adverse events in NMOSD treatment, and most studies have focused on umbilical cord- and bone marrow-derived MSCs. Drawing inspiration from CAR-T cell technology, Olivia Sirpilla et al. proposed that chimeric antigen receptor-engineered MSCs (CAR-MSCs) demonstrate enhanced immunosuppressive efficacy in murine models by upregulating immune checkpoint genes, T-cell inhibitory receptors, and immunosuppressive cytokines, without compromising cellular phenotype or safety profiles (58). This innovative approach may overcome current limitations and open new avenues for clinical translation of MSC therapies in neuroinflammatory disorders. Overall, MSC therapy exhibits promising efficacy, safety, and stability in the management of NMOSD, with umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) demonstrating comparative advantages in proliferation capacity and immunomodulatory properties.

3 Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy

CAR-T cell therapy involves the genetic engineering of autologous or allogeneic T cells through the design of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) structures, selection of viral vectors, and transduction in vitro, followed by reinfusion into patients to treat disease (59, 60). While this approach has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in oncology, its application in autoimmune disorders like NMOSD is emerging (59, 61). In contrast to the immune reconstitution achieved by hematopoietic stem cells or the indirect immunomodulatory effects of mesenchymal stem cells, CAR-T cells can effectively cross the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier, directly act on pathological sites within the central nervous system, eliminate B cells in the cerebrospinal fluid, and reduce the production of autoantibodies, thereby suppressing neuroinflammation. Importantly, engineered CAR-T cells enable precise targeting of CD19-positive cells and eradicate antibody-producing plasma cells, achieving a targeted therapeutic strategy (62).

Notably, CAR-T cells exhibit potent in vivo expansion and generate memory T-cell populations, enabling sustained therapeutic effects—a potential foundation for disease remission (21, 63). In relapsed/refractory NMOSD patients unresponsive to conventional immunosuppression, CAR-T therapy demonstrates controllable safety and promising efficacy. A dose of ≤1.0 × 106 CAR-T cells/kg has shown clinical stability and unexpected improvements in coexisting autoimmune conditions (64, 65). However, treatment-related toxicities, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), remain significant concerns (65). Evidence on CAR-T efficacy in CNS-targeted autoimmunity is sparse, with only anecdotal reports of individual benefits (66). However, the mechanisms of action of CAR-T cells in the treatment of NMOSD remain to be fully elucidated. Post-infusion infections (particularly within 28 days) correlate with CRS severity, mirroring observations in hematologic malignancies (67). Theoretical risks of CAR-T-induced oncogenesis necessitate long-term surveillance (68). Prohibitive pricing (€307,200–€350,000 per treatment) restricts accessibility for most patients (69). While CAR-T therapy represents a paradigm shift in NMOSD management, multicenter trials with larger cohorts are urgently needed to optimize dosing, mitigate neurotoxicity, and validate cost-effectiveness (see Tables 1, 2).

4 Other stem cell therapies

Neural stem cells (NSCs) demonstrate differentiation potential into oligodendrocytes, facilitating axonal myelination and neural regeneration. In murine models of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), CFHR1-modified NSCs exhibit dual therapeutic effects: mitigating inflammatory infiltration and attenuating immune-mediated astrocytic damage. These modified NSCs achieve therapeutic efficacy through targeted inhibition of complement cascade activation, particularly by suppressing membrane attack complex (MAC) formation (70). While promising, comprehensive investigations regarding long-term therapeutic sustainability and biosafety profiles remain imperative. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) possess inherent capacity for oligodendrocytic differentiation and myelin sheath reconstitution, positioning them as potential therapeutic agents for diverse central nervous system pathologies including Alzheimer’s disease (71, 72). Notably, clinical translation of OPC-based therapies in NMOSD remains unexplored, potentially limited by serum factor interference and age-dependent efficacy variations observed in patient populations (73). The current paucity of OPC-focused NMOSD research underscores a critical knowledge gap in this therapeutic domain.

5 Conclusion

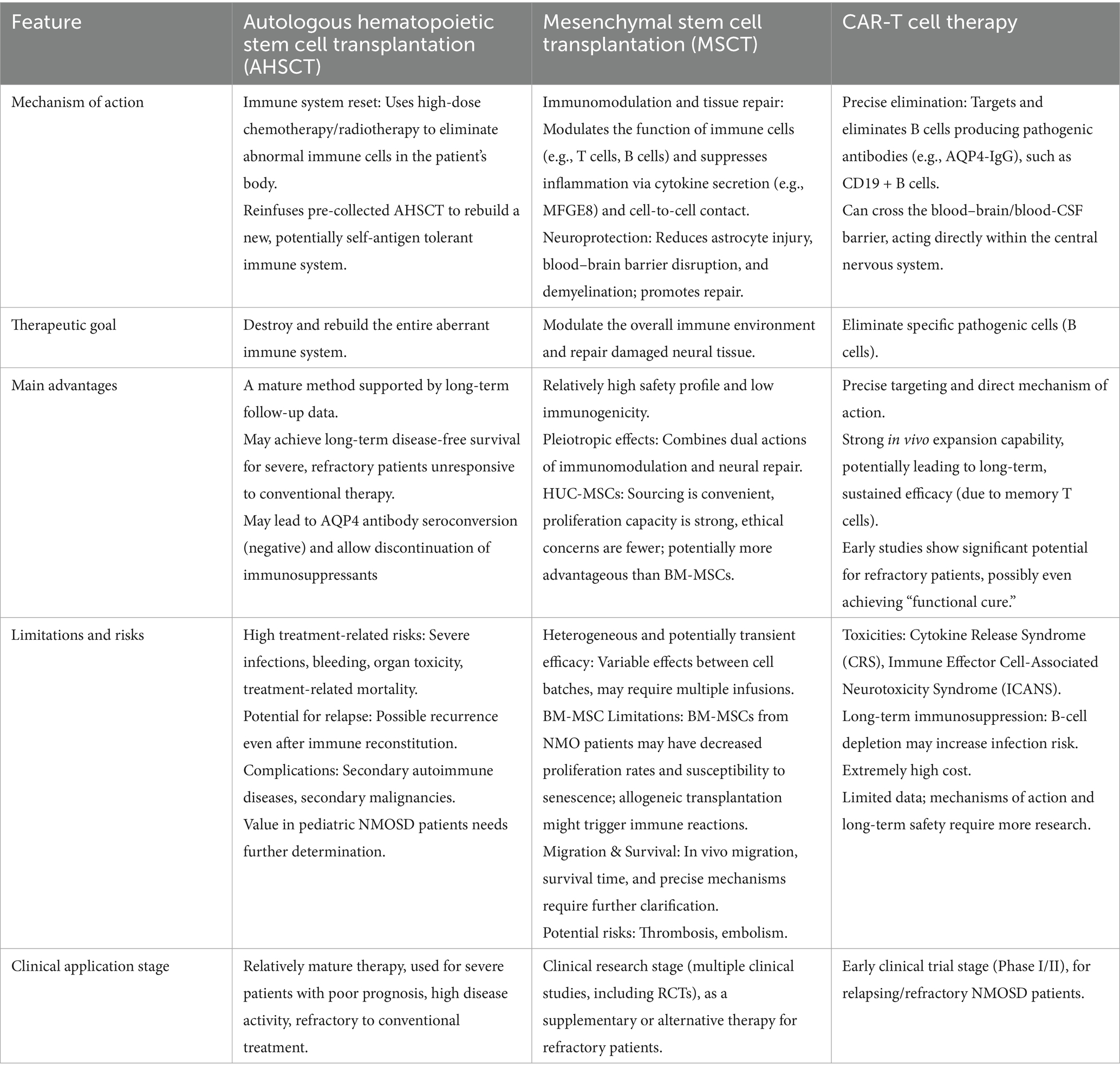

In conclusion, cell-based therapies play a significant role in the treatment of NMOSD, particularly in patients with relapsing or refractory disease, and may even hold the potential to achieve a cure. Each cellular therapeutic approach possesses distinct advantages and limitations. Advancements in genetic engineering technologies, the prospects for cell therapy—especially CAR-T cell therapy—are considerable. To realize clinical potential, future investigations must prioritize: (1) multi-center randomized controlled trials with extended follow-up periods; (2) comprehensive safety assessments including off-target effects and cytokine release syndromes; (3) optimization of cell persistence and functional stability; and (4) mechanistic studies addressing therapeutic heterogeneity across patient subgroups.

Author contributions

KZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YT: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Wingerchuk, DM, Lennon, VA, Lucchinetti, CF, Pittock, SJ, and Weinshenker, BG. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol. (2007) 6:805–15. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70216-8

2. Papp, V, Magyari, M, Aktas, O, Berger, T, Broadley, SA, Cabre, P, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of neuromyelitis optica: a systematic review. Neurology. (2021) 96:59–77. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011153

3. Du, Q, Shi, Z, Chen, H, Zhang, Y, Wang, J, Qiu, Y, et al. Mortality of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders in a Chinese population. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. (2021) 8:1471–9. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51404

4. Francis, A, Gibbons, E, Yu, J, Johnston, K, Rochon, H, Powell, L, et al. Characterizing mortality in patients with AQP4-ab+ neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. (2024) 11:1942–7. doi: 10.1002/acn3.52092

5. Knapp, RK, Hardtstock, F, Wilke, T, Maywald, U, Deiters, B, Schneider, S, et al. Evaluating the economic burden of relapses in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a real-world analysis using German claims data. Neurol Ther. (2022) 11:247–63. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00311-x

6. Li, R, Li, C, Huang, Q, Liu, Z, Chen, J, Zhang, B, et al. Immunosuppressant and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: optimal treatment duration and risk of discontinuation. Eur J Neurol. (2022) 29:2792–800. doi: 10.1111/ene.15425

7. Yin, Z, Qiu, Y, Duan, A, Fang, T, Chen, Z, Wu, J, et al. Different monoclonal antibodies and immunosuppressants administration in patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Neurol. (2023) 270:2950–63. doi: 10.1007/s00415-023-11641-1

8. Royston, M, Kielhorn, A, Weycker, D, Shaff, M, Houde, L, Tanvir, I, et al. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: clinical burden and cost of relapses and disease-related care in US clinical practice. Neurol Ther. (2021) 10:767–83. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00253-4

9. Carnero Contentti, E, and Correale, J. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: from pathophysiology to therapeutic strategies. J Neuroinflammation. (2021) 18:208. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02249-1

10. Wiewiórska-Krata, N, Foroncewicz, B, Mucha, K, and Zagożdżon, R. Cell therapies for immune-mediated disorders. Front Med (Lausanne). (2025) 12:1550527. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1550527

11. Zhuang, X, Hu, X, Zhang, S, Li, X, Yuan, X, and Wu, Y. Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy as a new approach for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. (2023) 64:284–320. doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08892-z

12. Jasim, SA, Yumashev, AV, Abdelbasset, WK, Margiana, R, Markov, A, Suksatan, W, et al. Shining the light on clinical application of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in autoimmune diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2022) 13:101. doi: 10.1186/s13287-022-02782-7

13. Hohlfeld, R. Mesenchymal stem cells for multiple sclerosis: hype or hope? Lancet Neurol. (2021) 20:881–2. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00324-0

14. Alexander, T, Greco, R, and Snowden, JA. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune disease. Annu Rev Med. (2021) 72:215–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-070119-115617

15. Kvistad, CE, Lehmann, AK, Kvistad, SAS, Holmøy, T, Lorentzen, ÅR, Trovik, LH, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis: long-term follow-up data from Norway. Mult Scler. (2024) 30:751–4. doi: 10.1177/13524585241231665

16. Petrou, P, Kassis, I, Levin, N, Paul, F, Backner, Y, Benoliel, T, et al. Beneficial effects of autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in active progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain. (2020) 143:3574–88. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa333

17. Boffa, G, Signori, A, Massacesi, L, Mariottini, A, Sbragia, E, Cottone, S, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in people with active secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology. (2023) 100:e1109–22. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000206750

18. Nabizadeh, F, Pirahesh, K, Rafiei, N, Afrashteh, F, Ahmadabad, MA, Zabeti, A, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Ther. (2022) 11:1553–69. doi: 10.1007/s40120-022-00389-x

19. Kalincik, T, Sharmin, S, Roos, I, Freedman, MS, Atkins, H, Burman, J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant vs fingolimod, natalizumab, and ocrelizumab in highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. (2023) 80:702–13. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.1184

20. Müller, F, Taubmann, J, Bucci, L, Wilhelm, A, Bergmann, C, Völkl, S, et al. CD19 CAR T-cell therapy in autoimmune disease – a case series with follow-up. N Engl J Med. (2024) 390:687–700. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2308917

21. Qin, C, Zhang, M, Mou, DP, Zhou, LQ, Dong, MH, Huang, L, et al. Single-cell analysis of anti-BCMA CAR T cell therapy in patients with central nervous system autoimmunity. Sci Immunol. (2024) 9:eadj9730. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.adj9730

22. Bulliard, Y, Freeborn, R, Uyeda, MJ, Humes, D, Bjordahl, R, de Vries, D, et al. From promise to practice: CAR T and Treg cell therapies in autoimmunity and other immune-mediated diseases. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1509956. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1509956

23. Brittain, G, Coles, AJ, Giovannoni, G, Muraro, PA, Palace, J, Petrie, J, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for immune-mediated neurological diseases: what, how, who and why? Pract Neurol. (2023) 23:139–45. doi: 10.1136/pn-2022-003531

24. Burt, RK, Balabanov, R, Han, X, Burns, C, Gastala, J, Jovanovic, B, et al. Autologous nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. (2019) 93:e1732–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008394

25. Malmegrim, KCR, Lima-Júnior, JR, Arruda, LCM, de Azevedo, JTC, de Oliveira, GLV, and Oliveira, MC. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases: from mechanistic insights to biomarkers. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:2602. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02602

26. Hoay, KY, and Ratnagopal, P. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of neuromyelitis optica in Singapore. Acta Neurol Taiwanica. (2018) 27:26–32.

27. Peng, F, Qiu, W, Li, J, Hu, X, Huang, R, Lin, D, et al. A preliminary result of treatment of neuromyelitis optica with autologous peripheral hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Neurologist. (2010) 16:375–8. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181b126e3

28. Greco, R, Bondanza, A, Oliveira, MC, Badoglio, M, Burman, J, Piehl, F, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in neuromyelitis optica: a registry study of the EBMT autoimmune diseases working party. Mult Scler. (2015) 21:189–97. doi: 10.1177/1352458514541978

29. Burman, J, Tolf, A, Hägglund, H, and Askmark, H. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for neurological diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2018) 89:147–55. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-316271

30. Nabizadeh, F, Masrouri, S, Sharifkazemi, H, Azami, M, Nikfarjam, M, and Moghadasi, AN. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci. (2022) 105:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2022.08.020

31. Jang, HM, Bae, S, Jung, J, Cho, H, Yoon, DH, and Kim, SH. Immunity against measles in Korean autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. J Korean Med Sci. (2024) 39:e224. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e224

32. Jaime-Pérez, JC, Meléndez-Flores, JD, Ramos-Dávila, EM, González-Treviño, M, and Gómez-Almaguer, D. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for uncommon immune-mediated neurological disorders: a literature review. Cytotherapy. (2022) 24:676–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2021.12.006

33. Cohen, JA, and Cross, AH. Is autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant better than high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies for relapsing multiple sclerosis? JAMA Neurol. (2023) 80:669–72. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.0467

34. Khan, TR, Zimmern, V, Aquino, V, and Wang, C. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in a pediatric patient with aquaporin-4 neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler Relat Disord. (2021) 50:102852. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.102852

35. Hau, L, Kállay, K, Kertész, G, Goda, V, Kassa, C, Horváth, O, et al. Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in a refractory case of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler Relat Disord. (2020) 42:102110. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102110

36. Ceglie, G, Papetti, L, Figà Talamanca, L, Lucarelli, B, Algeri, M, Gaspari, S, et al. T-cell depleted HLA-haploidentical HSCT in a child with neuromyelitis optica. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. (2019) 6:2110–3. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50843

37. Zhang, P, and Liu, B. Effect of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2020) 55:1928–34. doi: 10.1038/s41409-020-0810-z

38. Burton, JM, Duggan, P, Costello, F, Metz, L, and Storek, J. A pilot trial of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant in neuromyelitis optic spectrum disorder. Mult Scler Relat Disord. (2021) 53:102990. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.102990

39. López-García, L, and Castro-Manrreza, ME. TNF-α and IFN-γ participate in improving the immunoregulatory capacity of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells: importance of cell-cell contact and extracellular vesicles. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:9531. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179531

40. Vellasamy, S, Tong, CK, Azhar, NA, Kodiappan, R, Chan, SC, Veerakumarasivam, A, et al. Human mesenchymal stromal cells modulate T-cell immune response via transcriptomic regulation. Cytotherapy. (2016) 18:1270–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.06.017

41. Cuerquis, J, Romieu-Mourez, R, François, M, Routy, JP, Young, YK, Zhao, J, et al. Human mesenchymal stromal cells transiently increase cytokine production by activated T cells before suppressing T-cell proliferation: effect of interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α stimulation. Cytotherapy. (2014) 16:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.11.008

42. Oh, JY, Kim, H, Lee, HJ, Lee, K, Barreda, H, Kim, HJ, et al. MHC class I enables MSCs to evade NK-cell-mediated cytotoxicity and exert immunosuppressive activity. Stem Cells. (2022) 40:870–82. doi: 10.1093/stmcls/sxac043

43. Maqsood, M, Kang, M, Wu, X, Chen, J, Teng, L, and Qiu, L. Adult mesenchymal stem cells and their exosomes: sources, characteristics, and application in regenerative medicine. Life Sci. (2020) 256:118002. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118002

44. Lu, Z, Ye, D, Qian, L, Zhu, L, Wang, C, Guan, D, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell therapy on neuromyelitis optica. Curr Neurovasc Res. (2012) 9:250–5. doi: 10.2174/156720212803530708

45. Lu, Z, Zhu, L, Liu, Z, Wu, J, Xu, Y, and Zhang, CJ. IV/IT hUC-MSCs infusion in RRMS and NMO: a 10-year follow-up study. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:967. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00967

46. Aouad, P, Li, J, Arthur, C, Burt, R, Fernando, S, and Parratt, J. Resolution of aquaporin-4 antibodies in a woman with neuromyelitis optica treated with human autologous stem cell transplant. J Clin Neurosci. (2015) 22:1215–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.02.007

47. Yao, XY, Xie, L, Cai, Y, Zhang, Y, Deng, Y, Gao, MC, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells to treat neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum disorder (hUC-MSC-NMOSD): a study protocol for a prospective, Multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:860083. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.860083

48. Xue, C, Yu, H, Pei, X, Yao, X, Ding, J, Wang, X, et al. Efficacy of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell in the treatment of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: an animal study. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2025) 16:51. doi: 10.1186/s13287-025-04187-8

49. Xu, H, Jiang, W, Li, X, Jiang, J, Afridi, SK, Deng, L, et al. hUC-MSCs-derived MFGE8 ameliorates locomotor dysfunction via inhibition of ITGB3/ NF-κB signaling in an NMO mouse model. NPJ Regen Med. (2024) 9:4. doi: 10.1038/s41536-024-00349-z

50. Fu, Y, Yan, Y, Qi, Y, Yang, L, Li, T, Zhang, N, et al. Impact of autologous mesenchymal stem cell infusion on neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a pilot, 2-year observational study. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2016) 22:677–85. doi: 10.1111/cns.12559

51. Dulamea, AO, Sirbu-Boeti, MP, Bleotu, C, Dragu, D, Moldovan, L, Lupescu, I, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells applied on the pressure ulcers had produced a surprising outcome in a severe case of neuromyelitis optica. Neural Regen Res. (2015) 10:1841–5. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.165325

52. Yang, C, Yang, Y, Ma, L, Zhang, GX, Shi, FD, Yan, Y, et al. Study of the cytological features of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from patients with neuromyelitis optica. Int J Mol Med. (2019) 43:1395–405. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4056

53. Ankrum, JA, Ong, JF, and Karp, JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: immune evasive, not immune privileged. Nat Biotechnol. (2014) 32:252–60. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2816

54. Yang, Y, Li, Y, Zhang, S, Cao, L, Zhang, Y, and Fang, B. miR-199a-5p from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell exosomes promotes the proliferation of neural stem cells by targeting GSK-3β. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin Shanghai. (2023) 55:783–94. doi: 10.3724/abbs.2023024

55. Zhang, J, Buller, BA, Zhang, ZG, Zhang, Y, Lu, M, Rosene, DL, et al. Exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells promote remyelination and reduce neuroinflammation in the demyelinating central nervous system. Exp Neurol. (2022) 347:113895. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113895

56. Zhou, T, Yuan, Z, Weng, J, Pei, D, du, X, He, C, et al. Challenges and advances in clinical applications of mesenchymal stromal cells. J Hematol Oncol. (2021) 14:24. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01037-x

57. Moll, G, Ankrum, JA, Kamhieh-Milz, J, Bieback, K, Ringdén, O, Volk, HD, et al. Intravascular mesenchymal stromal/stem cell therapy product diversification: time for new clinical guidelines. Trends Mol Med. (2019) 25:149–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.12.006

58. Sirpilla, O, Sakemura, RL, Hefazi, M, Huynh, TN, Can, I, Girsch, JH, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells with chimaeric antigen receptors for enhanced immunosuppression. Nat Biomed Eng. (2024) 8:443–60. doi: 10.1038/s41551-024-01195-6

59. Caël, B, Bôle-Richard, E, Garnache Ottou, F, and Aubin, F. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy: recent updates and challenges in autoimmune diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2025) 155:688–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2024.12.1066

60. Liu, J, Zhao, Y, and Zhao, H. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1492552. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1492552

61. Brudno, JN, and Kochenderfer, JN. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies for lymphoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2018) 15:31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.128

62. Huang, R, Li, X, He, Y, Zhu, W, Gao, L, Liu, Y, et al. Recent advances in CAR-T cell engineering. J Hematol Oncol. (2020) 13:86. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00910-5

63. Schett, G, Mackensen, A, and Mougiakakos, D. CAR T-cell therapy in autoimmune diseases. Lancet. (2023) 402:2034–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01126-1

64. Qin, C, Tian, DS, Zhou, LQ, Shang, K, Huang, L, Dong, MH, et al. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy CT103A in relapsed or refractory AQP4-IgG seropositive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: phase 1 trial interim results. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2023) 8:5. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01278-3

65. Haghikia, A, Schett, G, and Mougiakakos, D. B cell-targeting chimeric antigen receptor T cells as an emerging therapy in neuroimmunological diseases. Lancet Neurol. (2024) 23:615–24. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00140-6

66. Konitsioti, AM, Prüss, H, Laurent, S, Fink, GR, Heesen, C, and Warnke, C. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for autoimmune diseases of the central nervous system: a systematic literature review. J Neurol. (2024) 271:6526–42. doi: 10.1007/s00415-024-12642-4

67. Hill, JA, Li, D, Hay, KA, Green, ML, Cherian, S, Chen, X, et al. Infectious complications of CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell immunotherapy. Blood. (2018) 131:121–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-793760

68. Verdun, N, and Marks, P. Secondary cancers after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. N Engl J Med. (2024) 390:584–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2400209

69. Heine, R, Thielen, FW, Koopmanschap, M, Kersten, MJ, Einsele, H, Jaeger, U, et al. Health economic aspects of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies for Hematological cancers: present and future. Hema. (2021) 5:e524. doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000524

70. Shi, K, Wang, Z, Liu, Y, Gong, Y, Fu, Y, Li, S, et al. CFHR1-modified neural stem cells ameliorated brain injury in a mouse model of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. J Immunol. (2016) 197:3471–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600135

71. Zou, P, Wu, C, Liu, TCY, Duan, R, and Yang, L. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in Alzheimer's disease: from physiology to pathology. Transl Neurodegener. (2023) 12:52. doi: 10.1186/s40035-023-00385-7

72. Zveik, O, Rechtman, A, Ganz, T, and Vaknin-Dembinsky, A. The interplay of inflammation and remyelination: rethinking MS treatment with a focus on oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Mol Neurodegener. (2024) 19:53. doi: 10.1186/s13024-024-00742-8

Keywords: neuromyelitis optica spectrum disease (NMOSD), autologous hematopoietic stem cells (AHSC), chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T), bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs), human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs)

Citation: Zhong K and Tang Y (2025) Cellular therapy in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Front. Neurol. 16:1709474. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1709474

Edited by:

Stefania Dalise, Pisana University Hospital, ItalyReviewed by:

Sepehr Dadfar, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, IranCopyright © 2025 Zhong and Tang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yulan Tang, dGFuZ3l1bGFuN0AxNjMuY29t

Kang Zhong

Kang Zhong Yulan Tang*

Yulan Tang*