- 1Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, Taizhou Hospital of Zhejiang Province Affiliated to Wenzhou Medical University, Taizhou, Zhejiang, China

- 2Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, Enze Hospital, Taizhou Enze Medical Center (Group), Taizhou, Zhejiang, China

Background: Administering adjuvant therapy following liver resection is crucial for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) exhibiting high-risk recurrence factors. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are effective against unresectable HCC; however, their effectiveness and safety for this specific patient group remain uncertain.

Methods: We conducted an extensive literature search across four scholarly databases to identify relevant studies. Our primary endpoints were overall survival (OS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), and adverse events (AEs). OS and RFS were quantified using hazard ratios (HRs), whereas the 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS and RFS rates were expressed as risk ratios (RRs). Additionally, the incidence of AEs was calculated.

Results: Our meta-analysis included 11 studies (N = 3,219 patients), comprising two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nine retrospective studies. Among these, eight studies reported HRs for OS, showing a statistically significant improvement in OS among patients receiving adjuvant ICIs (HR, 0.60; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.45–0.80; p < 0.0001). All included studies reported HRs for RFS, indicating a favorable impact of adjuvant ICIs (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.52–0.73; p < 0.0001). Moreover, aggregated data demonstrated improved 1- and 2-year OS and RFS rates with adjuvant ICIs. The incidence rate of AEs of any grade was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.49–0.91), with grade 3 or above AEs occurring at a rate of 0.12 (95% CI, 0.05–0.20).

Conclusion: Adjuvant ICI therapy can enhance both OS and RFS rates in patients with HCC exhibiting high-risk recurrence factors, with manageable AEs.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#recordDetails PROSPERO, identifier CRD42023488250.

Introduction

Liver cancer ranks sixth in global cancer prevalence and is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality (1). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), accounting for approximately 90% of primary liver cancer cases, dominates in incidence (2). Liver resection is the primary treatment for HCC (2); however, the notable recurrence rate following liver resection significantly affects patient prognosis (3), particularly in cases with high-risk recurrence factors such as tumor size exceeding 5 cm, presence of multiple tumors, satellite nodules, microvascular invasion (MVI), and portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT), all of which substantially elevate the risk of early recurrence (4–10). Therefore, integrating adjuvant therapies is crucial for reducing postoperative recurrence risk in these patients (11). Several adjuvant therapies, including transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, and sorafenib, have demonstrated efficacy (12–14).

Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are recognized as effective therapies for unresectable HCC (15–17), their role as adjuvant therapy after HCC resection is debatable (18, 19). This meta-analysis aims to clarify the efficacy of ICIs as adjuvant treatment following liver resection in patients with HCC exhibiting high-risk recurrence factors.

Methods

This systematic review is registered in PROSPERO (registration no. CRD42023488250).

Search strategy

Comprehensive searches were conducted on four primary databases—Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library—up to November 30, 2023, with an update of the search results on April 20, 2024. The search terms comprised a combination of MeSH terms and keywords, including “hepatocellular carcinoma,” “immune checkpoint inhibitors,” “immunotherapy,” and “adjuvant therapy.” Detailed search strategies for each database are presented in Supplementary Material S1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria comprised the following (1): Studies, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs, that investigated the comparative outcomes of adjuvant ICIs versus no adjuvant ICIs in patients with HCC exhibiting high-risk recurrence factors (2); studies on interventions involving ICI monotherapy or their combination with TACE or tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), considered as adjuvant ICI interventions (3); studies providing data on at least one primary outcome measure, such as overall survival (OS) or recurrence-free survival (RFS). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Studies involving patients lacking high-risk recurrence factors; (2) studies comparing various combinations of ICIs with other treatment modalities; (3) non-comparative studies, abstracts, case reports, and review articles.

Definitions

OS was defined as the duration from the date of surgical intervention to mortality, whereas RFS was defined as the period from the date of surgery until tumor reappearance. OS and RFS were primary endpoints analyzed as time-to-event outcomes. The 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS and RFS rates indicated the proportion of patients who remained alive or free from tumor recurrence at these intervals after liver resection, respectively. Adverse events (AEs) were assessed following the guidelines outlined in the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 5.0.

Quality assessment and data extraction

Initial quality assessment and data extraction were conducted by two independent investigators. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) assessed the quality of nonrandomized comparative trials, with scores categorized as low (≤5 points), medium (6–7 points), and high (≥8 points) (20). The Cochrane risk of bias tool was employed to assess potential biases in each study (21). Customized, structured forms were employed for data extraction, including the first author’s name, publication year, patient demographics, and tumor characteristics, as well as primary outcomes, including OS; RFS; the 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS and RFS rates; and AEs. In cases of discordance, a third researcher was consulted to achieve consensus.

Statistical analysis

Hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the inverse variance method. Risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% CIs were computed via the Mantel–Haenszel method. Incidence rates of AEs of any grade and those graded 3 or higher were also computed with corresponding 95% CIs. Heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using the Q statistic and I2 index, with I2 values of 25% and 50% indicating low and moderate heterogeneity, respectively. Depending on the observed level of heterogeneity, the appropriate test model was employed; specifically, a random-effects model was employed when I2 exceeded 50% (20). Sensitivity analysis was conducted to validate the robustness of the findings. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots. Subgroup analyses were planned based on variables such as study design, patient age, tumor characteristics (size, number), presence of MVI and satellites, Edmondson-Steiner (ES) grade, treatment modality, and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.3.1.

Results

Study search and selection

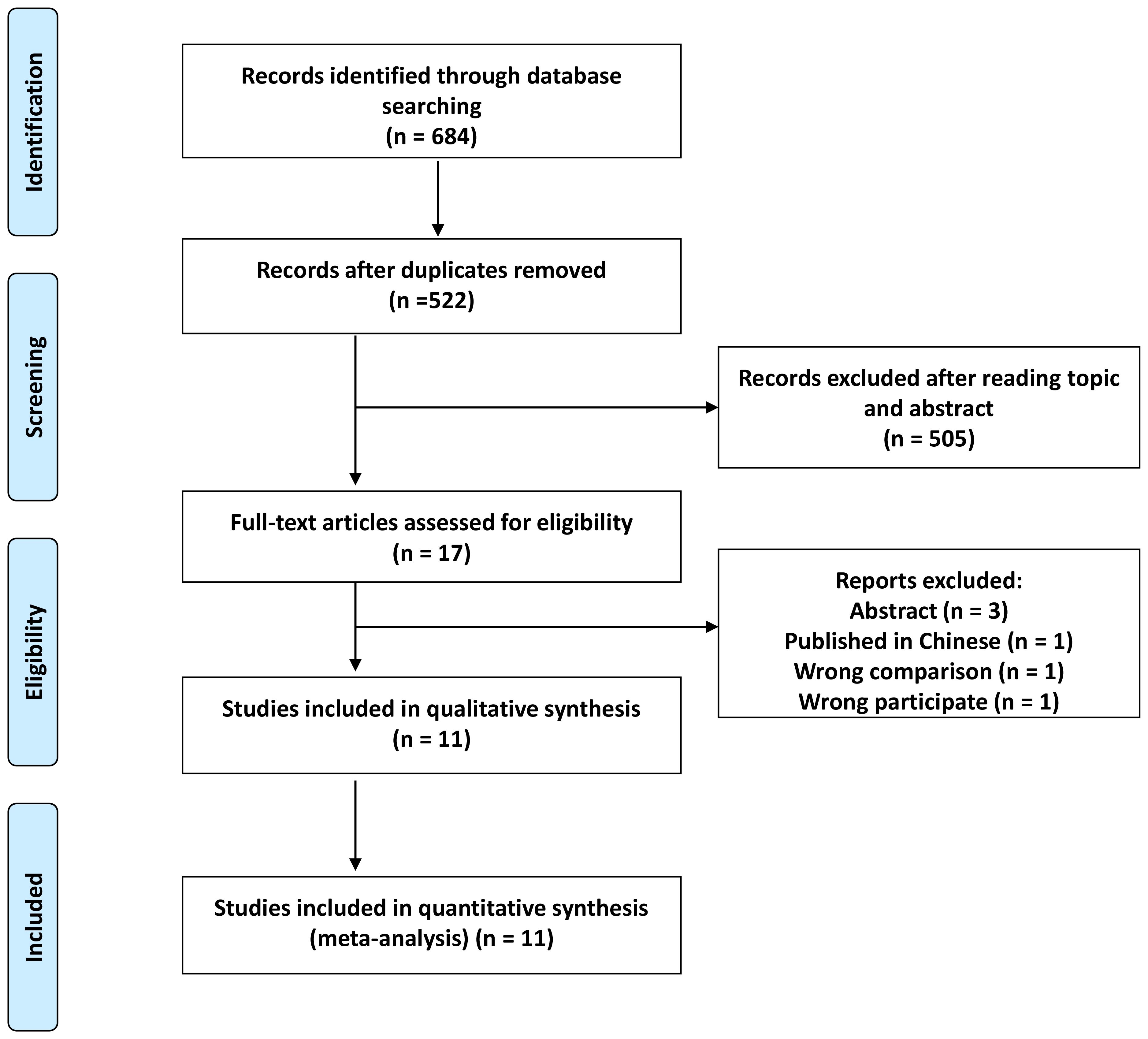

A comprehensive search initially yielded 684 records, from which 162 duplicates were removed, resulting in 522 unique records. Subsequent screening of titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 505 studies, leaving 17 articles for further scrutiny. After applying predetermined criteria, six articles were further excluded, resulting in 11 studies eligible for inclusion in our meta-analysis (Figure 1) (18, 19, 22–30).

Study characteristics

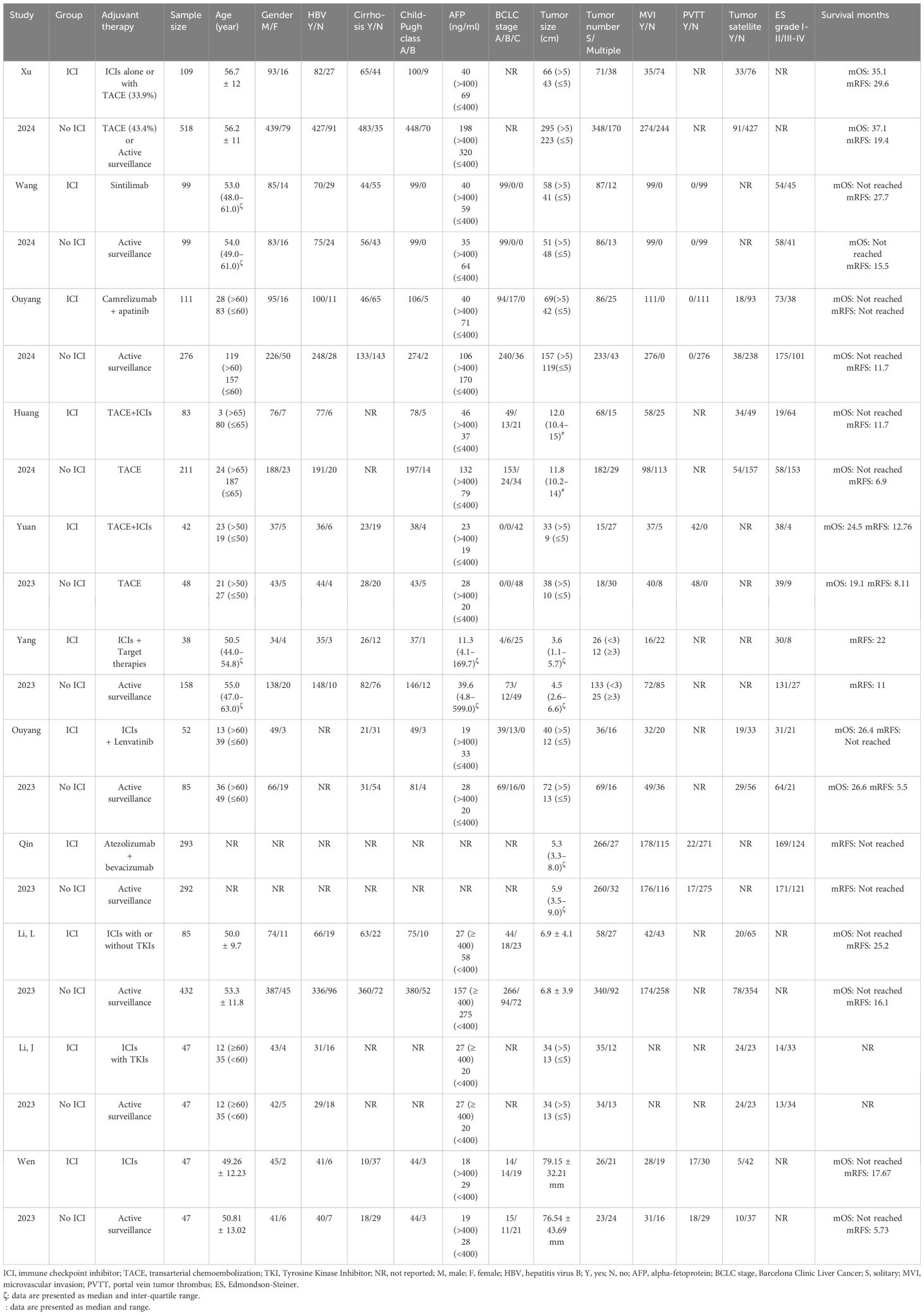

Our analysis incorporated 11 studies, including two RCTs and nine retrospective studies, with a total of 3,219 patients. Among these, eight studies utilized propensity score matching (PSM) to derive outcomes (22–30). Five studies explicitly excluded patients who had received alternative adjuvant therapies, such as TACE or TKI monotherapy (23–25, 28, 29), whereas another five studies included varying proportions of patients who had undergone these additional treatments (18, 22, 26, 27, 30). Notably, one study investigated the efficacy of adjuvant ICIs in patients with HCC who had undergone either liver resection or radiofrequency ablation (18); however, our analysis exclusively focused on patients who underwent liver resection. The adjuvant therapies examined in these studies ranged from combinations such as TACE+ICIs and ICIs combined with lenvatinib or other TKIs to atezolizumab in conjunction with bevacizumab. Table 1 and Supplementary Material S2 provide detailed characteristics of the included studies, including those employing PSM. Quality assessment utilizing the NOS rated five studies at 7 points, four studies at 8 points, and one study at 9 points (Supplementary Material S3). The RCT conducted by Wang et al. was appraised as high risk in two blinded domains and low risk in the remainder (Supplementary Material S4).

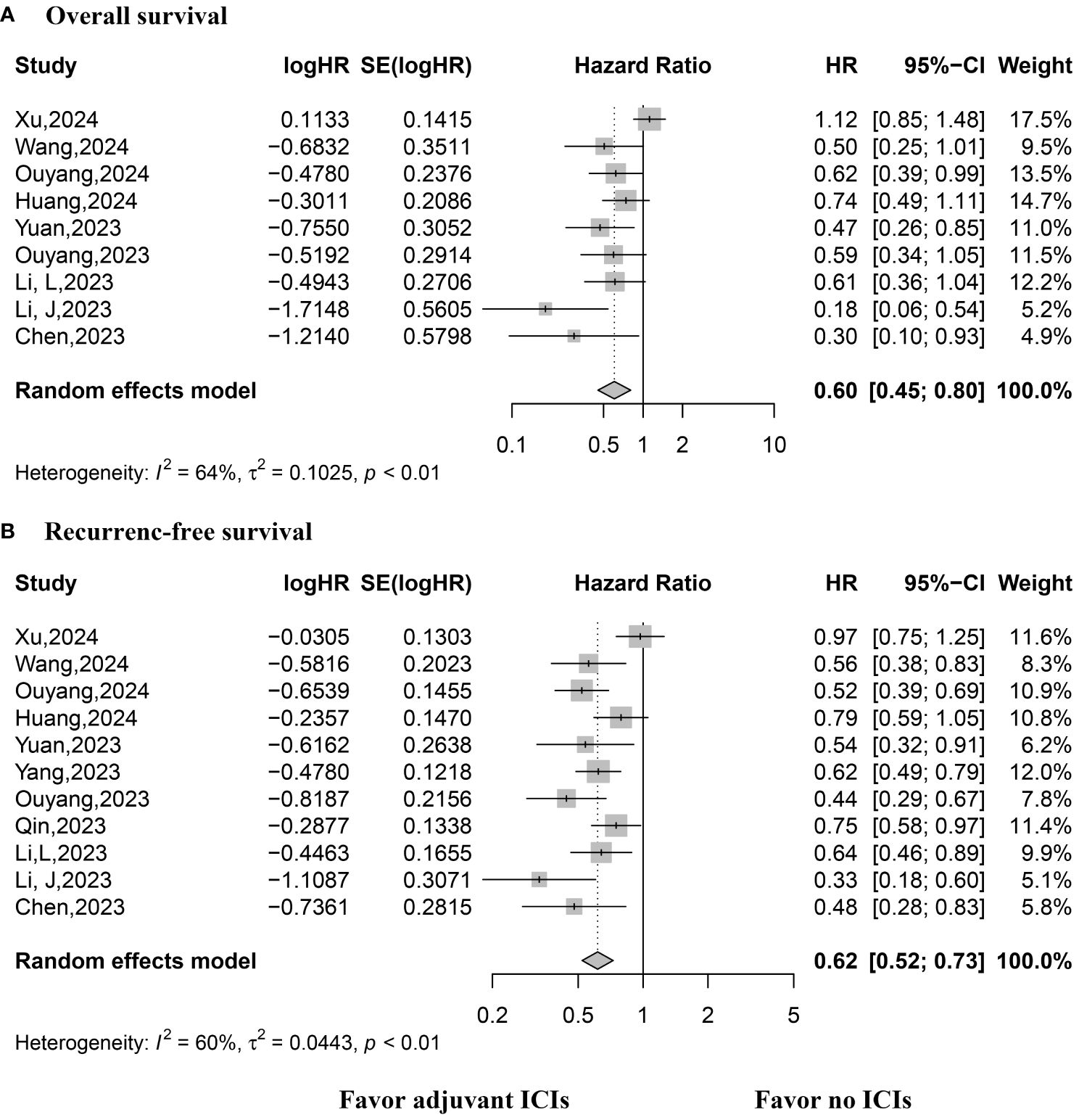

OS and RFS

Eight studies reported HRs for OS, necessitating the use of a random-effects model due to considerable variability. The pooled analysis demonstrated improved OS among patients who received adjuvant ICIs (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.445–0.80; p < 0.0001; Figure 2). Similarly, all included studies reported HRs for RFS, with a random-effects model employed due to substantial heterogeneity. The synthesized results indicated improved RFS in patients receiving adjuvant ICIs (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.52–0.73; p < 0.0001; Figure 2).

Figure 2 Forest plot of overall and recurrence-free survival rates. (A) Overall survival; (B) Recurrence-free survival.

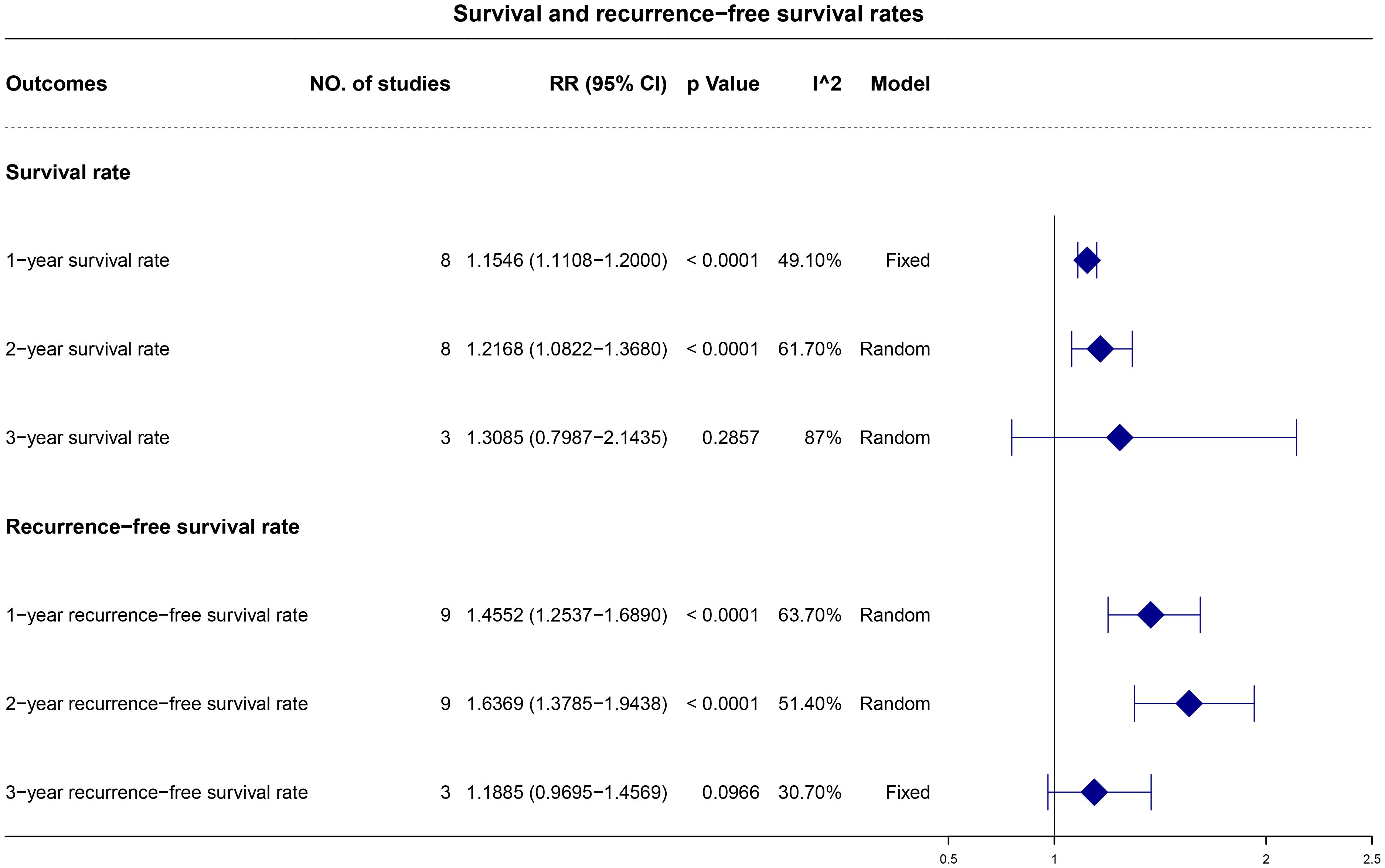

The 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS rates were reported in eight, eight, and three studies, respectively. A fixed-effects model was applied for the 1-year OS analysis, whereas a random-effects model was utilized for the 2- and 3-year OS analysis due to observed heterogeneity. The pooled results demonstrated higher 1- and 2-year OS rates with adjuvant ICI therapy (1-year RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.11–1.20; p < 0.0001 and 2-year RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.08–1.37; p < 0.0001), with similar 3-year OS rates (Figure 3).

The 1-, 2-, and 3-year RFS were reported in nine, nine, and three studies, respectively. A random-effects model was applied, except for the 3-year RFS analysis, which exhibited low heterogeneity. The synthesized data indicated higher 1- and 2-year RFS rates with adjuvant ICI therapy (1-year RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.25–1.69 and p < 0.0001; 2-year RR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.38–1.94; p < 0.0001), with comparable 3-year RFS rates (Figure 3).

AEs

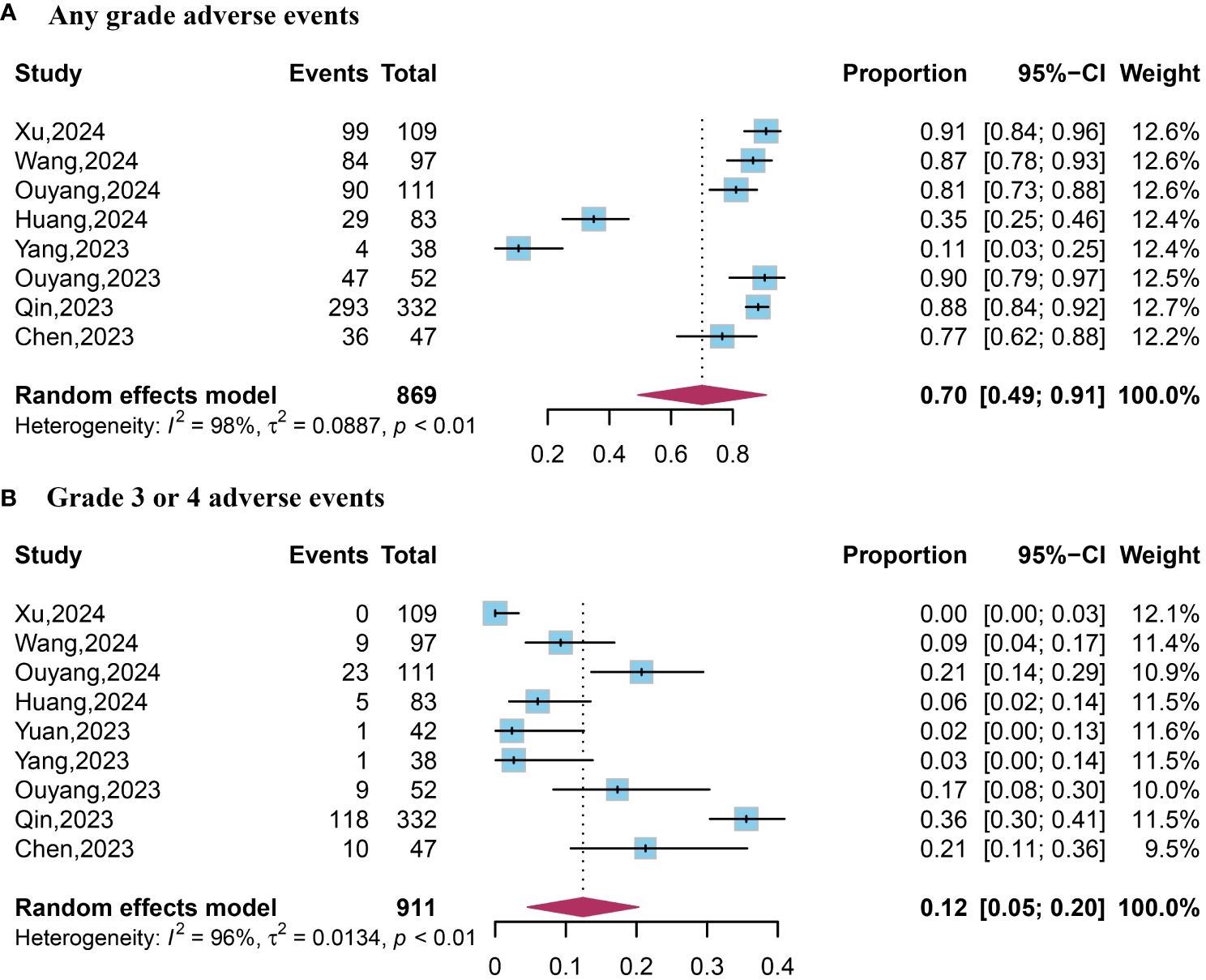

Data on AEs of any grade were available from eight studies. The pooled analysis revealed an occurrence rate of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.49–0.91) for AEs of any grade (Figure 3). Data on grade 3 or 4 AEs were extracted from five studies. The pooled data reported an occurrence rate of 0.12 (95% CI, 0.05–0.20) for grade 3 or 4 AEs (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Forest plot of any grade and grade 3 or 4 adverse events. (A) Any grade adverse events; (B) Grade 3 or 4 adverse events.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

Sensitivity analysis findings are presented in Supplementary Material S5. Funnel plots for OS and RFS exhibited asymmetry, with Egger tests indicating significant publication bias (Supplementary Material S6). To address this bias, the trim and fill method was used to identify its potential influence on the results. We identified four studies for adjustment in both OS and RFS analysis (Supplementary Material S7). Subsequent forest plots based on the adjusted data revealed that the results for OS may have been impacted by publication bias, whereas those for RFS remained unaffected (Supplementary Material S8).

Subgroup analysis

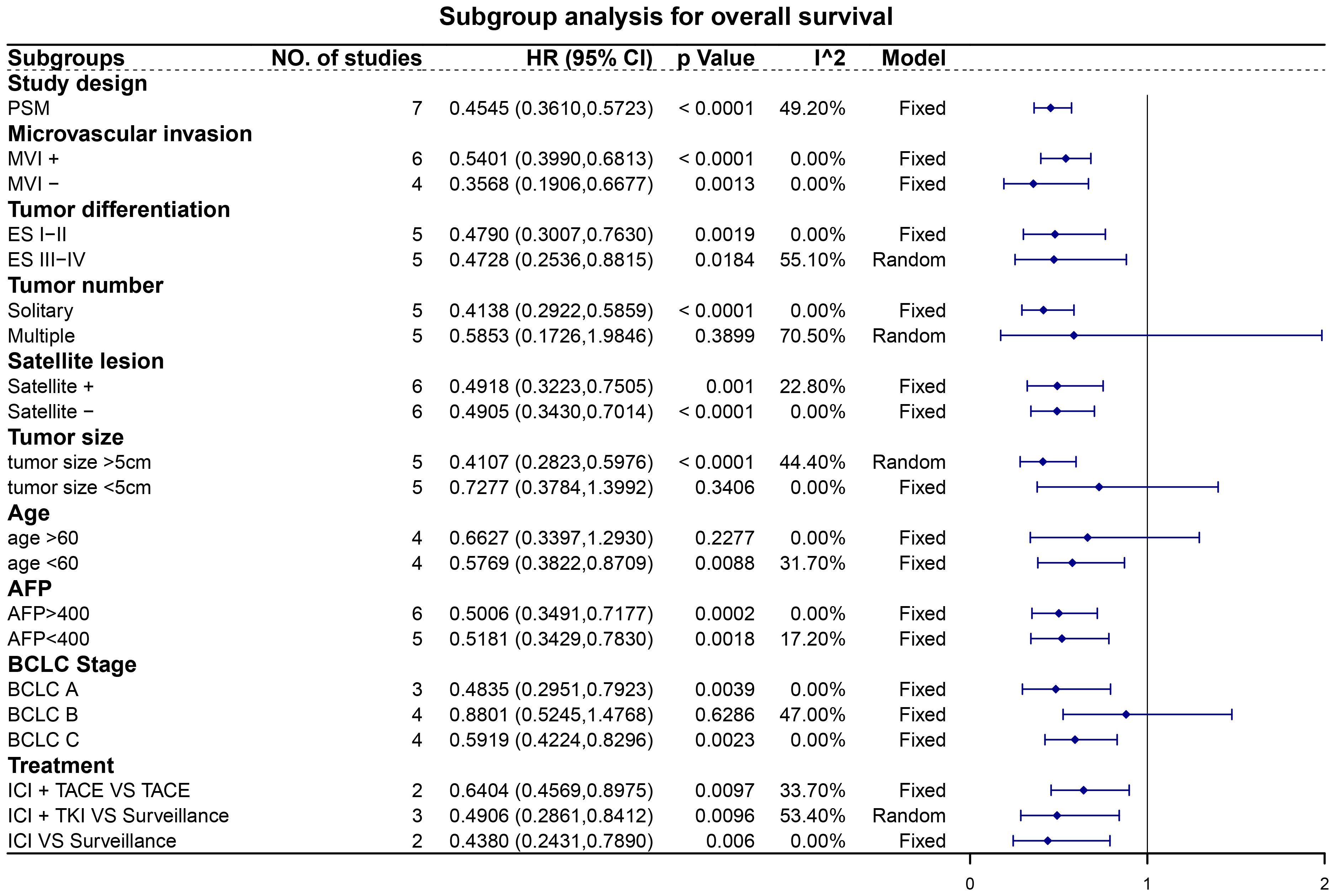

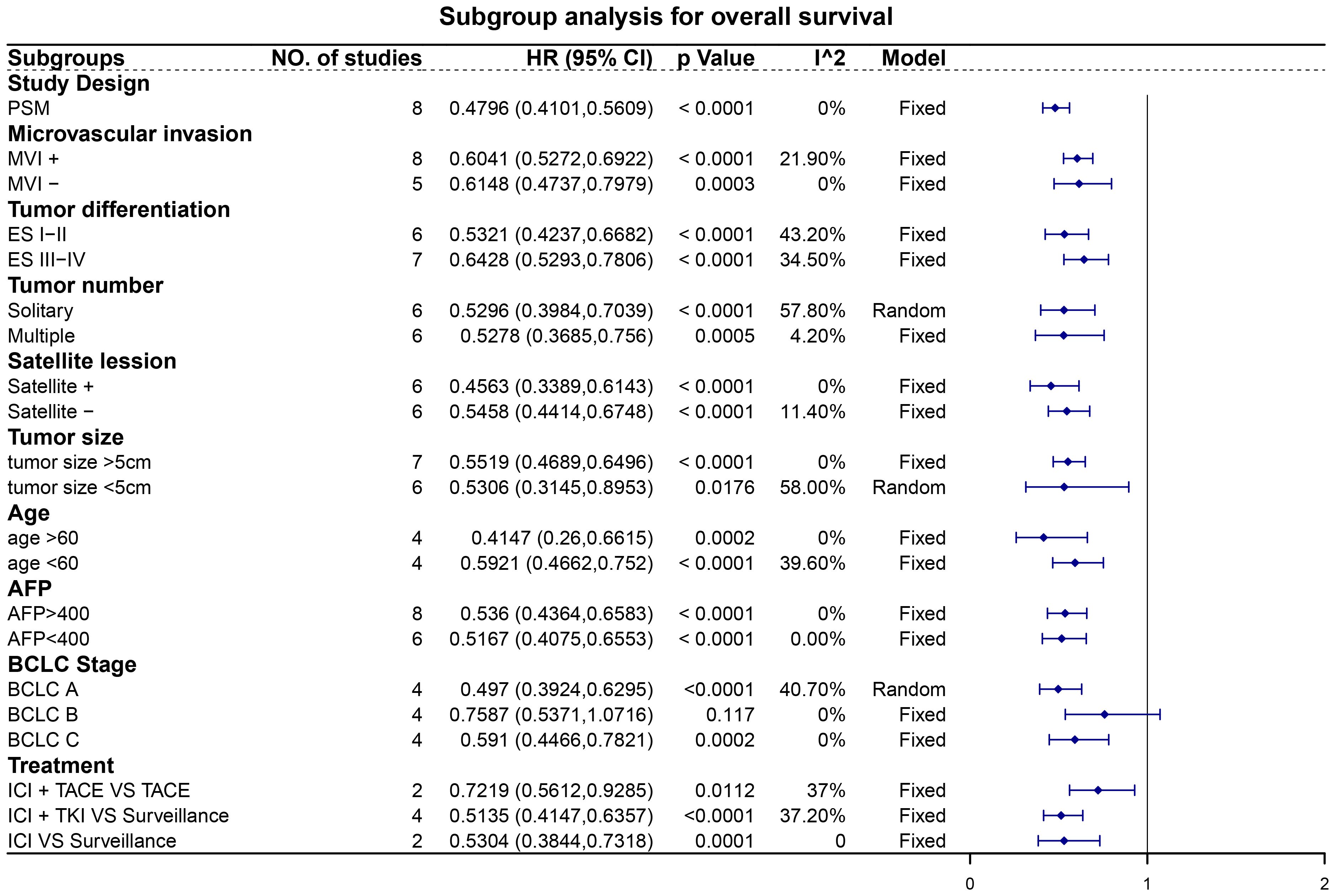

Subgroup analyses revealed noteworthy findings (Figures 5, 6). Among the studies employing PSM, pooled data demonstrated that patients receiving adjuvant ICIs exhibited improved OS and RFS rates, with HRs of 0.45 (95% CI, 0.36–0.57; p < 0.0001) for OS and 0.48 (95% CI, 0.41–0.56; p < 0.0001) for RFS. Additionally, within the subgroups stratified according to high-risk recurrence factors, adjuvant ICIs notably improved OS among patients with MVI, ES grade III-IV, satellite lesions, tumor size > 5 cm, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels > 400 ng/mL, and HCC categorized under BCLC stage C. Similarly, improvements in RFS rates were observed among patients with MVI, ES grade III-IV, multiple tumors, satellite lesions, tumor size > 5 cm, AFP levels > 400 ng/mL, and BCLC stage C HCC, regardless of whether adjuvant ICIs were combined with TACE and TKIs.

Figure 5 Subgroup analysis for overall survival. Abbreviations: PSM, propensity score matching; MVI, microvascular invasion; ES, Edmondson-Steiner; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Figure 6 Subgroup analysis for recurrence-free survival. Abbreviations: PSM, propensity score matching; MVI, microvascular invasion; ES, Edmondson-Steiner; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Discussion

This meta-analysis highlights the potential of adjuvant ICI therapy following resection to improve both OS and RFS in patients with HCC exhibiting high-risk recurrence factors, with manageable AEs. Our study represents a pioneering endeavor to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adjuvant ICIs in patients with HCC exhibiting high-risk recurrence factors. The findings, bolstered by a statistically robust sensitivity analysis, provide credible evidence of the prognostic benefits associated with adjuvant ICI therapy in HCC cases. Subgroup analyses, particularly those utilizing PSM, revealed consistent findings, further reinforcing this conclusion. Moreover, these analyses, focusing on diverse tumor recurrence risk factors, underscore the potential of ICIs to ameliorate prognosis in patients with HCC exhibiting varied high-risk recurrence factors (10).

Early HCC recurrence often indicates tumors associated with heightened recurrence risks (31). Aggressive treatment of residual tumor cells could potentially enhance both RFS and OS, considering that occult micrometastases are present at initial HCC diagnosis. Several high-quality RCTs have investigated the efficacy and safety of ICIs, either alone or in combination with TKIs, for managing unresectable HCC (16, 17, 32–35). These trials have demonstrated that ICI therapy, alone or in combination with TKIs, yields comparable or superior prognoses compared with sorafenib treatments. ICIs function by reactivating effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cell functions via immune checkpoint inhibition, whereas TKIs optimize vascularization to enhance drug delivery and foster more robust tumor immune surveillance, potentially resulting in a synergistic effect in combination therapies. Consequently, ICIs, with or without TKIs, hold promise for targeting residual liver tumor cells (36). Furthermore, AEs appear less frequent with adjuvant therapies compared with first-line treatments for unresectable HCC, indicating a favorable safety profile for adjuvant ICIs (15–17, 32).

Despite variations in tumor characteristics and treatment modalities observed across the included studies, adjuvant ICI therapy consistently yielded improved prognoses. Nonetheless, the optimal adjuvant treatment strategy remains uncertain, emphasizing the need for tailored treatment selection based on individual patient characteristics, disease stage, and treatment response. Moreover, vigilant monitoring and adjustment as needed are crucial to optimize outcomes (37).

Our analysis is not without limitations. First, the number of included studies was modest, and most studies were retrospective. Second, although our subgroup analyses were extensive, their findings should be interpreted cautiously due to sample size limitations. Finally, publication bias was observed. These limitations warrant additional high-quality research to corroborate our findings.

Conclusion

Adjuvant ICIs have demonstrated the potential to improve OS and RFS rates in patients with HCC exhibiting high-risk recurrence factors, with manageable AEs. However, additional high-quality research is needed to strengthen these findings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

LH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YQ: Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AW: Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by grants from Zhejiang Provincial Basic Public Welfare Research Project (Grant no. LTGY23H030008), Taizhou Science and Technology Planning Project (Grant no. 20ywb25 and 22ywa34), Medical and Health Technology Plan of Zhejiang Province (Grant no. 2021RC140 and 2024KY1825), Taizhou Highlevel Talents Special Support Program (The third level).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2024.1374262/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

2. Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2021) 7:6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3

3. Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. (2019) 380:1450–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263

4. Choi KK, Kim SH, Choi SB, Lim JH, Choi GH, Choi JS, et al. Portal venous invasion: the single most independent risk factor for immediate postoperative recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2011) 26:1646–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06780.x

5. Chen ZH, Zhang XP, Feng JK, Li LQ, Zhang F, Hu YR, et al. Actual long-term survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with microvascular invasion: a multicenter study from China. Hepatol Int. (2021) 15:642–50. doi: 10.1007/s12072-021-10174-x

6. Shinkawa H, Tanaka S, Takemura S, Amano R, Kimura K, Kinoshita M, et al. Nomograms predicting extra- and early intrahepatic recurrence after hepatic resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. (2021) 169:922–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.10.012

7. Chen ZH, Zhang XP, Lu YG, Li LQ, Chen MS, Wen TF, et al. Actual long-term survival in HCC patients with portal vein tumor thrombus after liver resection: a nationwide study. Hepatol Int. (2020) 14:754–64. doi: 10.1007/s12072-020-10032-2

8. Orimo T, Kamiyama T, Kakisaka T, Nagatsu A, Asahi Y, Aiyama T, et al. Hepatectomy is beneficial in select patients with multiple hepatocellular carcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol. (2022) 29:8436–45. doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-12495-z

9. Kokudo T, Hasegawa K, Matsuyama Y, Takayama T, Izumi N, Kadoya M, et al. Survival benefit of liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with portal vein invasion. J Hepatol. (2016) 65:938–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.044

10. Yao LQ, Chen ZL, Feng ZH, Diao YK, Li C, Sun HY, et al. Clinical features of recurrence after hepatic resection for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma and long-term survival outcomes of patients with recurrence: A multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. (2022) 29(8):5206. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.2022S1.EP-20

11. Zhang W, Zhang B, Chen XP. Adjuvant treatment strategy after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Med. (2021) 15:155–69. doi: 10.1007/s11684-021-0848-3

12. Hu L, Zheng Y, Lin J, Shi X, Wang A. Does adjuvant hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy improve patient outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma following liver resection? A meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. (2023) 21:121. doi: 10.1186/s12957-023-03000-1

13. Huang S, Li D, Zhuang L, Sun L, Wu J. A meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. World J Surg Oncol. (2021) 19:168. doi: 10.1186/s12957-021-02280-9

14. Esagian SM, Kakos CD, Giorgakis E, Burdine L, Barreto JC, Mavros MN. Adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization following curative-intent hepatectomy versus hepatectomy alone for hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancers (Basel). (2021) 13(12):2984. doi: 10.3390/cancers13122984

15. Xu J, Shen J, Gu S, Zhang Y, Wu L, Wu J, et al. Camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (RESCUE): A nonrandomized, open-label, phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res. (2021) 27:1003–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2571

16. Ren Z, Xu J, Bai Y, Xu A, Cang S, Du C, et al. Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): a randomized, open-label, phase 2–3 study. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:977–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00252-7

17. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1894–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745

18. Qin S, Chen M, Cheng AL, Kaseb AO, Kudo M, Lee HC, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus active surveillance in patients with resected or ablated high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma (IMbrave050): a randomized, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2023) 402:1835–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01796-8

19. Ouyang J, Wang Z, Yuan K, Yang Y, Zhou Y, Li Q, et al. Adjuvant lenvatinib plus PD-1 antibody for hepatocellular carcinoma with high recurrence risks after hepatectomy: A retrospective landmark analysis. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2023) 10:1465–77. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S424616

20. Wells GA, Wells G, Shea B, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, et al eds. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses (2014). Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Newcastle-Ottawa-Scale-(NOS)-for-Assessing-the-Wells-Wells/c293fb316b6176154c3fdbb8340a107d9c8c82bf.

21. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Bmj. (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

22. Yuan L, Feng J, Zhang Y, Lu C, Xu L, Liang C, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization plus immune checkpoint inhibitor as postoperative adjuvant therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: A multicenter cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. (2023) 49:1226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2023.01.020

23. Yang J, Jiang S, Chen Y, Zhang J, Deng Y. Adjuvant ICIs plus targeted therapies reduce HCC recurrence after hepatectomy in patients with high risk of recurrence. Curr Oncol. (2023) 30:1708–19. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30020132

24. Li L, Wu PS, Liang XM, Chen K, Zhang GL, Su QB, et al. Adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors associated with higher recurrence-free survival in postoperative hepatocellular carcinoma (PREVENT): a prospective, multicentric cohort study. J Gastroenterol. (2023) 58:1043–54. doi: 10.1007/s00535-023-02018-2

25. Li J, Wang WQ, Zhu RH, Lv X, Wang JL, Liang BY, et al. Postoperative adjuvant tyrosine kinase inhibitors combined with anti-PD-1 antibodies improves surgical outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma with high-risk recurrent factors. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1202039. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1202039

26. Chen W, Hu S, Liu Z, Sun Y, Wu J, Shen S, et al. Adjuvant anti-PD-1 antibody for hepatocellular carcinoma with high recurrence risks after hepatectomy. Hepatol Int. (2023) 17:406–16. doi: 10.1007/s12072-022-10478-6

27. Xu X, Wang MD, Xu JH, Fan ZQ, Diao YK, Chen Z, et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy improves recurrence-free and overall survival following surgical resection for intermediate/advanced hepatocellular carcinoma a multicenter propensity matching analysis. Front Immunol. (2024) 14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1322233

28. Wang K, Xiang YJ, Yu HM, Cheng YQ, Liu ZH, Qin YY, et al. Adjuvant sintilimab in resected high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized, controlled, phase 2 trial. Nat Med. (2024) 30:708–15. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02786-7

29. Ouyang JZ, Yang Y, Zhou YZ, Chang X, Wang ZZ, Li QJ, et al. Adjuvant camrelizumab plus apatinib in resected hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion: a multi-center real world study. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. (2024). doi: 10.21037/hbsn

30. Huang H, Liao W, Zhang K, Wang H, Cheng Q, Mei B. Adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization plus immunotherapy for huge hepatocellular carcinoma: A propensity score matching cohort study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2024) 11:721–35. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S455878

31. Wu JC, Huang YH, Chau GY, Su CW, Lai CR, Lee PC, et al. Risk factors for early and late recurrence in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. (2009) 51:890–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.07.009

32. Qin S, Chan SL, Gu S, Bai Y, Ren Z, Lin X, et al. Camrelizumab plus rivoceranib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (CARES-310): a randomized, open-label, international phase 3 study. Lancet. (2023) 402:1133–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00961-3

33. Llovet JM, Kudo M, Merle P, Meyer T, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus lenvatinib plus placebo for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (LEAP-002): a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2023) 24:1399–410. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00469-2

34. Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, Cheng AL, Mathurin P, Edeline J, et al. Nivolumab versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 459): a randomized, multicenter, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2022) 23:77–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00604-5

35. Kelley RK, Rimassa L, Cheng AL, Kaseb A, Qin S, Zhu AX, et al. Cabozantinib plus atezolizumab versus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (COSMIC-312): a multicenter, open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2022) 23:995–1008. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00326-6

36. Llovet JM, Castet F, Heikenwalder M, Maini MK, Mazzaferro V, Pinato DJ, et al. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2022) 19:151–72. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00573-2

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, immune checkpoint inhibitors, prognosis, liver resection, adjuvant therapy

Citation: Hu L, Kong Y, Qiao Y and Wang A (2024) Can adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors improve the long-term outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma with high-risk recurrent factors after liver resection? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Front. Oncol. 14:1374262. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1374262

Received: 21 January 2024; Accepted: 13 May 2024;

Published: 24 May 2024.

Edited by:

Antonella Argentiero, National Cancer Institute Foundation (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Fabrizio Pappagallo, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico di Bari, ItalyEndrit Shahini, National Institute of Gastroenterology S. de Bellis Research Hospital (IRCCS), Italy

Copyright © 2024 Hu, Kong, Qiao and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yingli Qiao, qiao-ying-li@126.com; Aidong Wang, wangaidong@enzemed.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Lingbo Hu

Lingbo Hu Yenan Kong1†

Yenan Kong1† Yingli Qiao

Yingli Qiao Aidong Wang

Aidong Wang