- 1Chair of Business and Social Psychology, School of Business, Economics, and Society, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Germany

- 2Department of Psychology, MSH Medical School Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

This study addresses today's insecure career context, which entails significant stress for many employees. While career insecurity's negative effects on well-being have been extensively documented, existing research often overlooks a critical daily concern: employees' fear of missing out on career-relevant resources at work. To explore this gap, we introduce the concept of Fear of Missing Out at Work (FoMO at work) to the career literature, conceptualizing it through a Conservation of Resources Theory lens. We specifically posit that career insecurity triggers the fear of missing out on informational and relational resources at work, thereby undermining psychological well-being. Furthermore, we propose that employees' affiliation at work can mitigate these detrimental effects. Results from OLS regressions on data from 206 employees across two time points three weeks apart revealed that changes in career insecurity predicts increased fear of informational and relational exclusion. In turn, the fear of relational exclusion promotes irritation and overall stress. Additionally, we found evidence that affiliation at work buffers the effects of career insecurity on the fear of informational exclusion. These findings improve our empirical understanding of FoMO at work as a resource-based fear and provide practical recommendations for mitigating its negative effects within today's insecure career context.

Introduction

Fear of Missing Out at Work has recently gained significant attention as an emerging phenomenon of contemporary work environments (Budnick et al., 2020). It represents the fear of missing out on informational and relational resources at work, specifically, the fear and apprehension of missing out on critical job-related information and opportunities to build and strengthen professional networks. However, modern work environments have changed how individuals access these resources compared to only a decade ago. For example, in a hybrid work situation—where time is spent both in the office and working remotely—it may be more difficult to expand one's social capital because informal conversations and meetings do not occur as frequently as they would in an on-site setting. Additionally, the digitalization of professional communication via email, messaging apps, and networking platforms such as LinkedIn makes informational resources more accessible. However, the amount of information has increased tremendously, making it more difficult to keep up with new information and identify relevant data. These circumstances lead to the emergence of Fear of Missing Out at Work reflecting employees' concerns about lacking access to or missing out on task- and career-relevant informational or relational resources at work.

Informational and relational resources are essential for successfully navigating the complexities of contemporary careers. Access to information about the labor market, industry trends, and organizational dynamics enables individuals to make informed career decisions. And relational resources, such as social networks and supportive colleagues, provide guidance and growth opportunities. While Fear of Missing Out at Work (FoMO at work) gained traction as a phenomenon born of our technologized, media-rich work environments, we posit that it also reflects underlying career insecurity that makes access to informational and relational resources feel indispensable. Given the current career context—characterized by the rise of remote work, recent economic downturns, and employees' growing concerns of being replaced by AI and automated systems—the latter assumption seems particularly plausible. This assumption implies that an insecure career naturally triggers FoMO at work, and that affiliation at work counteracts respective impairments: Individuals who are well-connected and socially included at work may feel less anxious about missing out on information and opportunities to strengthen and build professional contacts, suggesting affiliation at work as a resource that prevents insecure career environments from translating into day-to-day impairments.

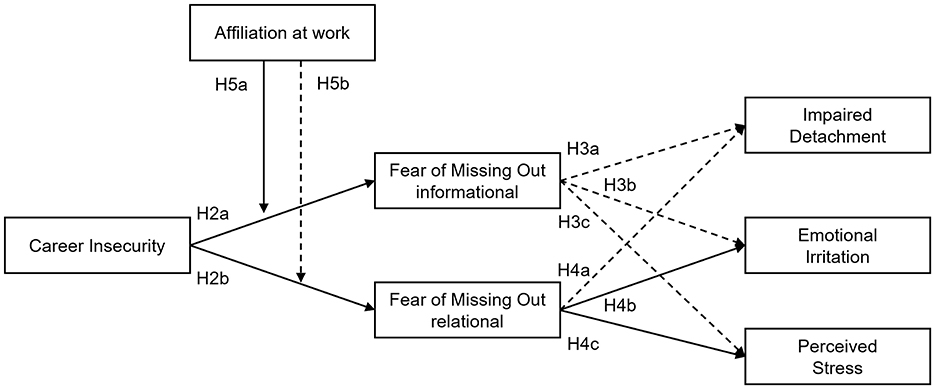

In line with these premises, our study has two objectives. First, we introduce FoMO at work to the career literature. Specifically, we aim to demonstrate that career insecurity, a stressor on the macro-level, not only relates to impairments of psychological well-being but also manifests as fear of missing out on informational and relational resources at work. Second, we explore the assumption that these effects are mitigated when people feel well-connected in their work environment (cf. Figure 1). With these goals in mind, the study contributes to a better empirical understanding of FoMO at work and provides practical recommendations for mitigating the negative effects of insecure careers on employees' well-being.

Figure 1. Theoretical model and hypotheses on the relationships between career insecurity, affiliation at work, informational and relational fear of missing out at work, and well-being impairments. The direct effects of career insecurity on well-being impairments (H1a, H1b, and H1c) are not depicted; solid lines indicate significant effects; dashed lines indicate non-significant effects.

Theoretical framework

Theories that focus on explaining how individuals acquire, protect and use resources provide an ideal framework for understanding the antecedents and outcomes of FoMO at work in the current insecure career context. One such framework is the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (e.g., Hobfoll, 1989), which conceptualizes stress as a response to the loss or threat of loss of valued resources. COR theory (e.g., Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018) has been widely applied to the domains of work (Bakker and Demerouti, 2017; Nielsen et al., 2017) and careers (De Cuyper et al., 2012; Sullivan and Al Ariss, 2022) and has proven relevant for understanding stress in professional environments (Westman et al., 2004; Hobfoll, 2011).

According to COR theory, individuals are motivated to obtain, retain, and protect valuable resources. Resources can be objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies that are either inherently valuable or necessary to achieve other valued goals. When resource loss occurs or is anticipated, individuals are likely to experience psychological stress. The theory further emphasizes that losing resources has a greater impact than gaining them. It also highlights that individuals must invest their resources in order to acquire new ones and prevent further loss (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001, 2011; Halbesleben et al., 2014). Furthermore, the importance of acquiring resources increases under conditions of actual or threatened of loss of resources, as described by the Gain Paradox Principle of COR. Hobfoll (1989) also acknowledged the relevance of broader environmental conditions in shaping resource dynamics. For instance, economic instability can jeopardize an individual's access to essential resources. This ecological perspective has gained traction in more recent COR literature, where the concept of resource passageways has emerged. These passageways can be understood as conditional factors, such as the labor market as a macro-level context, that influence the availability, accessibility, and subjective value of resources (Hobfoll, 2011; Hobfoll et al., 2018). By facilitating or hindering resource acquisition, these passageways play a pivotal role in determining individuals' capacity to maintain psychological well-being. In this regard, the modern career environment can be conceptualized as a critical resource passageway (Hobfoll, 2012; Hobfoll et al., 2018; Holmgreen et al., 2017). It provides, limits, or threatens access to a variety of valued resources such as job security, financial security, professional identity, and development opportunities. However, the current labor market is often characterized by volatility, precarious employment, and organizational changes, all of which contribute to the perception of career insecurity. Thus, career insecurity poses a constant threat to valued resources according to COR theory and signifies today's career context as resource passageway that threatens access to resources, and thus, impairs psychological well-being.

Career insecurity and psychological impairment

The contemporary career context is consistently labeled as insecure (Jiang et al., 2025; Spurk et al., 2022), and many employees worldwide experience the accompanying uncertainty and unpredictability (e.g., employees in scientific careers; Alisic and Wiese, 2020; actors in the gig economy; e.g., Callanan et al., 2017; in precarious employment; e.g., Llosa et al., 2018). At the heart of career insecurity is the individual's experience of a “sense of powerlessness to maintain desired employability” (Colakoglu, 2011, p. 48), which has been shown to negatively impact both physical and mental health (Spurk et al., 2022). For instance, it has been associated with emotional exhaustion, anxiety, low life satisfaction, and depression (Llosa et al., 2018). And even the perceived threat of losing valued job features (i.e., qualitative job insecurity) is significantly related to mental health complaints (Iliescu et al., 2017).

Since there are many approaches to assessing well-being impairments, it is crucial to acknowledge and depict potential psychological impairments caused by career insecurity (e.g., worries, exhaustion, depression) as thoroughly as possible and, ideally, stratified across perceptual levels, generalizability across life domains, and intensity gradients, representing sequential stages of stress progression. First, at the perceptual level, the triple-match principle (de Jonge and Dormann, 2006) distinguishes cognitive, emotional, and physical strain. Second, generalizability differentiates work-specific stress (e.g., work-related irritation; Mohr et al., 2006) from generalized stress (e.g., perceived stress; Cohen et al., 1983), and reflects whether career threats may permeate broader life domains. Third, intensity gradients reveal a progression from mild precursors (e.g., difficulty detaching from work; Sonnentag and Bayer, 2005) to intermediate markers of dysfunction (e.g., irritation as a depression precursor; Mohr et al., 2006), culminating in clinically severe impairment (e.g., perceived stress; Schneider et al., 2020).

To capture this stratification comprehensively, we consider three outcome measures as crucial: impaired detachment, emotional irritation, and perceived stress. Impaired detachment—defined as the inability to disengage from work-related thoughts during non-work time—operates at the cognitive perceptual level and represents the mildest intensity of impairment (Cropley and Zijlstra, 2011; Sonnentag et al., 2017; Sonnentag and Fritz, 2015). It constitutes the initial stage where career threats penetrate personal life, serving as the earliest detectable sign of work-related strain. Emotional irritation—characterized as work-induced negative affective reactivity after work such as frustrated or volatile mood—functions at the emotional perceptual level and indicates moderate impairment intensity. It emerges when detachment failure triggers affective spillover (Mohr et al., 2006), acting as a temporally intermediate stress marker. This state embodies emotional exhaustion stemming from unresolved career threats and predicts clinical outcomes like depression, reflecting its transitional severity (Dormann and Zapf, 2002). Perceived stress—manifesting as a sense of global psychological overload—operates at the systemic perceptual level and denotes the most severe non-clinical intensity of well-being impairment. It materializes when career strain generalizes beyond the work domain (Cohen et al., 1983). Perceived stress signifies cross-domain resource depletion and demonstrates robust correlations with mental health impairments (Schneider et al., 2020), positioning it as a critical precursor of clinical strain symptoms. Collectively, these measures allow to map a cascading pathway depicting well-being impairments of career insecurity as fueling cognitive intrusion (detachment failure), triggering emotional spillover (emotional irritation), and ultimately causing systemic overload (perceived stress), and are thus examined in an initial replication hypothesis, which also serves as a basis for the development of consequent hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1. Career insecurity is positively associated with impaired detachment (H1a), emotional irritation (H1b), and perceived stress (H1c).

Career insecurity and Fear of Missing Out at Work

Thus far, the resource-based perspective has been used to illustrate that career insecurity—as a resource passageway threatening valued resources—leads to stress. However, a resource-based perspective can also explain why employees who perceive career insecurity may develop an increased fear of missing out on informational and relational resources: According to COR theory, in a career context where the threat and loss of resources is characteristic, the importance of career-related resources increases, and the loss of career-related resources becomes more salient—the Fear of Missing Out at work emerges.

FoMO at work as resource threat experience

The concept of Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) was originally introduced in the context of (social) media use and referred to as the fear of being excluded from social interactions and events (Przybylski et al., 2013). Budnick et al. (2020) transferred the concept to the workplace, coining the term FoMO at work. FoMO at work (also workplace FoMO) describes the worry about missing important work-related updates, valuable work- and career-related information, and opportunities to build and strengthen professional relationships. According to Budnick et al. (2020), workplace FoMO encompasses two primary facets—relational exclusion and informational exclusion. Informational FoMO at work is characterized by anxiety about missing critical work-related updates and insights. It centers on the possibility of not receiving essential, timely information that could promote daily task fulfillment or overall career advancement (Budnick et al., 2020; Ebner et al., 2025a). Relational FoMO at work emphasizes concerns about not capitalizing on networking opportunities or interpersonal interactions that could strengthen one's social capital within the workplace. It thus refers to the apprehension surrounding missed opportunities to nurture and maintain meaningful work relationships and professional networks, which are essential to career development (Budnick et al., 2020; Ebner et al., 2025a).

We suggest that the fear of being excluded from the flow of information and access to professional connections at work can be interpreted as missing out on important career-promoting resources sensu COR theory. Fundamentally, COR theory defines resources as objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies that are either valued for themselves or because they facilitate the acquisition or protection of other resources (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001). According to Hobfoll's taxonomy of resources Hobfoll (1989, 2001), informational FoMO would entail both, the fear of missing out on condition resources (e.g., up to date labor market insights, industry trends, or organizational updates) and energy resources (e.g., saved cognitive effort to stay updated, positive time-and attention-budget to get information), and relational FoMO would entail the fear of missing out on social resources (e.g., professional network, peer support) and personal resources (e.g., self-esteem, group identity). Thus, while career insecurity—driven by external factors such as economic instability, technological advancements, and changing labor market demands—negatively affects workers' well-being as a threat of resources on a macro-level, FoMO at work is regarded as a natural micro-level consequence of navigating an insecure career context, in which individuals naturally become more vigilant and concerned about missing out on career-relevant opportunities and resources.

In summary, we argue that the fear of lacking access to informational or relational resources at work is a psychological response to career insecurity and an everyday manifestation of individuals' concerns about employability and career setbacks. We therefore hypothesize that individuals with greater career insecurity are more likely to experience heightened informational and relational FoMO at work.

Hypothesis 2. Career insecurity is positively associated with informational Fear of Missing Out at Work (H2a) and relational Fear of Missing Out at Work (H2b).

FoMO at work and psychological impairment

Based on the theoretical proposition that career insecurity exacerbates FoMO at work, it is evident that these day-to-day worries may be a potent predictor of impairments in psychological well-being. From the perspective of COR theory, FoMO at work begins as an aversive emotional reaction to the threat of losing resources. This anxiety leads to compensatory behaviors aimed at preserving or regaining these resources, such as investing energy, time, and attention (Hobfoll, 2001; Halbesleben et al., 2014), exemplarily as constant connectivity, compulsive checking of work communication, and heightened vigilance toward social and informational cues. However, when the perceived benefits (e.g., staying updated) fail to offset the emotional and cognitive costs of sustained engagement (Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012), chronic resource investment without adequate gain results in resource depletion, which is a well-established precursor to emotional exhaustion, burnout, and strain (Bakker and Demerouti, 2017). For example, FoMO at work drives maladaptive coping strategies in response to resource threats, fueling problematic media use behaviors such as compulsive connectivity, which has been shown to result in poorer social relationships, affective impairments, depression, and anxiety (Milyavskaya et al., 2018; Blackwell et al., 2017; Elhai et al., 2017; Kross et al., 2013). Similarly, FoMO, experienced as the constant need to stay informed and connected, directly correlates with difficulties mentally detaching from work, increased emotional irritation, and daily stress (Ebner et al., 2025b). Furthermore, excessive attempts to maintain informational and relational resources may further erode personal resources (e.g., self-efficacy and autonomy), thereby accelerating resource loss spirals (Hobfoll et al., 2018). In this way, FoMO at work functions as a psychological demand that consumes resources and additionally drains access to other valued resources needed for recovery and psychological well-being, thus predicting short-term stress and more intense strain.

Hypothesis 3. Informational Fear of Missing Out at Work is positively associated with impaired detachment (H3a), emotional irritation (H3b), and perceived stress (H3c).

Hypothesis 4. Relational Fear of Missing Out at Work is positively associated with impaired detachment (H4a), emotional irritation (H4b), and perceived stress (H4c).

Affiliation at work as a buffer

Given that individuals who perceive their careers as insecure are prone to suffer from FoMO at work, studies further point to the role of basic human needs in this relationship (e.g., Beyens et al., 2016). According to self-determination theory (SDT), basic human needs—the need for competence, the need for autonomy and the need for relatedness—are “innate, organismic needs” that are essential for psychological growth and well-being, motivation, and behavior (Deci and Ryan, 2000, p. 229). Satisfied basic human needs at work are known to positively correlate with job satisfaction, work engagement, job and organizational commitment, performance, life satisfaction, and general health (e.g., Baard et al., 2004; Deci et al., 2008; Van den Broeck et al., 2008), as well as subjective career success, perceived person-vocation fit, and career commitment (Ng and Feldman, 2014; Dahling and Lauricella, 2017; Dose et al., 2019). Conversely, unsatisfied psychological needs while pursuing career goals are associated with greater psychological distress and hinder career goal progress (Holding et al., 2020).

As noted above, according to COR theory, career insecurity reflects a threat to resources. Thus, it motivates behaviors to resolve or overcome the threat, that is, behaviors that lead to the satisfaction of (unsatisfied) needs (Sheldon and Gunz, 2009). This assumption is based on psychological needs theories, which posit that unsatisfied needs lead to motive activation and the motivation to engage in behaviors that overcome or counteract the perceived threat (e.g., Schaller et al., 2017; Sheldon, 2011). In the context of career insecurity, one basic human need seems to be particularly relevant: the need for connectedness. This basic human need has been referred to as the affiliative motive, the psychological need to belong, or the need for relatedness. It drives behaviors to establish, maintain, or repair friendly relations with others (McClelland and Jemmott III, 1980). When this need is satisfied in the workplace, individuals experience themselves as part of a group (e.g., a work team), share group goals and resources, care for and help others, and engage in meaningful social interactions (Kenrick et al., 2010).

According to COR theory, satisfied social motives such as the affiliation motive, result in external resources that individuals can use to acquire or preserve other resources (Hobfoll and Ford, 2007). Affiliation should thus mitigate the negative effects of career insecurity as demonstrated by, for example, Naswall et al. (2005), who showed that social support mitigates negative effects of job insecurity on strain. Specifically, since social integration at work provides individuals with important informational resources (e.g., sharing relevant career information or market knowledge) and relational resources (e.g., a professional network to rely on), we argue that both types of resources—informational and relational—depend on the satisfaction of affiliative needs at work. A solid affiliation at work—manifested as an individual's sense of belonging to a professional group and being able to rely on others—thus serves as conditional factor that modifies the strength with which career insecurity promotes FoMO at work. In that way, affiliation at work mitigates the effects of career insecurity on informational and relational FoMO at work. This theoretical reasoning leads to a hypothesis that complements our assumptions about the interplay between career insecurity, affiliation at work and FoMO at work.

Hypothesis 5. Affiliation at work mitigates the positive association between career insecurity and informational Fear of Missing Out at Work (H5a) and relational Fear of Missing Out at Work (H5b). When affiliation at work is high, the association will be weaker.

Methods

Recruiting and sample

Participants were invited via email from a major commercial data collection service provider to take part in a two-wave study. Participants were pre-selected based on the following eligibility criteria: Only individuals who were of legal age who were employed part-time or full-time were invited. Specifically, they were invited to participate in two data collection sessions, 3 weeks apart. Participants were fully informed of the study's purpose and procedures, as well as the applicable privacy regulations. They gave informed consent and received a € 2.00 financial incentive for participating. At the first measurement time, we collected data on all constructs and control variables, including affiliation at work. At the second measurement time after 3 weeks, we collected data on career insecurity, FoMO at work, and stress measures (detachment, emotional irritation, and perceived stress).

A total of 354 individuals responded to the study invitation at Time 1. After excluding 148 individuals who did not fully meet the eligibility criteria or who did not provide data at Time 2, the final sample consisted of 206 participants (50.0% male), aged 22 to 68 years (M = 44.80 years; SD = 11.77), who lived in Germany during the study period. A dropout analysis revealed no significant differences between those who remained and those who dropped out regarding any of the constructs assessed at Time 1. All study participants were employed in dependent part-time or full-time jobs, working an average of 35.15 h per week by contract (SD = 8.50) and 37.63 h per week effectively (SD = 10.64). On average, participants worked remotely 39.60% of the time (SD = 40.66%; minimum: 0%; maximum: 100%). The mean proportion of working time spent using a computer or laptop was 72.55% (SD = 34.10%).

Measures

Career insecurity

Career insecurity was assessed using the Career Insecurity Scale (Höge et al., 2012). The scale is a widely used German measure (e.g., Spurk et al., 2016) with four items to be answered on a six-point Likert scale from 1 (does not apply at all) to 6 (applies completely). An example item is “I am uncertain that I will achieve my career goals” (English translation by the authors). All items express insecurity about whether self-set career goals are achievable or whether one's career future appears unpredictable (Höge et al., 2012). Cronbach's alpha was α = 0.81 (Time 1) and α = 0.81 (Time 2), respectively.

Fear of Missing Out at Work

The workplace FoMO scale by Budnick et al. (2020), translated into German (Ebner et al., 2025a), was used to measure respondents' fear of missing out at work during the past week. The measure represents an employee's pervasive concern about missing out on valuable information or career opportunities and consists of two five-item subscales to be responded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example items are “I worry that I will miss out on important information that is relevant to my job” (informational exclusion) and “I worry that I will miss out on networking opportunities that my coworkers will have” (relational exclusion). Cronbach's alpha for the informational exclusion subscale was α = 0.96 (Time 1) and α = 0.95 (Time 2), respectively; Cronbach's alpha for the relational exclusion subscale was α = 0.95 (Time 1) and α = 0.95 (Time 2).

Affiliation at work

To assess affiliation at work, we used the German version of the Fundamental Social Motives Inventory adapted to the work context (Neel et al., 2016; German version: Steiner et al., 2025). Participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which their current work life fulfills their need for belonging and inclusion as reflected in the experience of affiliation. Specifically, respondents indicated the degree of fulfillment of the instruments' six-item affiliation motive-subscales “group” and “exclusion concern,” which refer to the positive aspects of group affiliation and social inclusion at work from 1 (not at all fulfilled) to 7 (fully fulfilled). Example items are “In my working life, I am part of a group” and “In my working life, people do things without me” (reverse coded; translation by the authors). Items of the exclusion concern subscale were reverse coded so that high scores on both subscales indicated high levels of affiliation at work. Cronbach's alpha was α = 0.83 (Time 1).

Impaired detachment

Impaired detachment was measured using the psychological detachment subscale of the Recovery Experience Questionnaire (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). The four items of this subscale represent an individual's ability to mentally disengage from work at the end of the day. Respondents were asked to indicate their ability to recover in the evenings and the absence of work-related ruminative intrusions during their free-time in the past week from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An example item is “I didn't think about work at all” (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). All items were reverse scored. Cronbach's alpha was α = 0.94 (Time 1) and α = 0.93 (Time 2).

Emotional irritation

The irritation scale by Mohr et al. (2005) was used to measure emotional irritation. The emotional irritation subscale intends to capture psychological strain stemming from an imbalance of work-related demands and resources that manifests beyond the work context as agitated irritability (Mohr et al., 2005). Respondents indicated retrospectively the extent to which they reacted with anger, grumpiness, or emotional tension after work during the last week on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). An example of the five-item subscale reads: “I got grumpy when others approached me after work” (Mohr et al., 2006). Cronbach's alpha was α = 0.93 (Time 1) and α = 0.95 (Time 2).

Perceived stress

The abbreviated German version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10; Klein et al., 2016) by Cohen et al. (1983) was used to measure participants' psychological stress. The scale uses 10 items to capture the extent to which participants perceived their lives as unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overwhelming in the past week (Cohen et al., 1983). Respondents are asked to answer the scale items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) with regard to the previous week. An example item reads, “In the last week. how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems?” (item derived from Cohen et al., 1983). Cronbach's alpha was α = 0.79 (Time 1) and α = 0.81 (Time 2).

Control variables

We controlled for age and gender as controls because of their associations with social motives, career threats, perceptions of career insecurity, stress, and coping strategies (Giunchi et al., 2016; Menéndez-Espina et al., 2019; Neel et al., 2016). We also controlled for regular weekly work hours by dividing the sample into two groups: full-time workers (more than 35 h per week) and part-time workers (<35 h per week). The resulting variable “working part-time” was dummy coded as 0 (working full-time) and 1 (working part-time). Additionally, we controlled for the percentage of respondents' average weekly work hours spent in the home office. This variable is referred to as working remotely in the analyses. These two measures will probably affect how likely people are to have access to the necessary information and relationships at work.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R 4.2.2 (R Core Team, 2022). We performed linear regression analyses and assessed model adequacy in accordance with the recommendations of Shatz (2023) using the R-package performance (Lüdecke et al., 2021). Overall, the assumptions were met in all models (linearity, homogeneity of variance, collinearity, influential observations, and normality of residuals).

Since for the behavioral sciences, Cohen et al. (2003) recommend relying on regressed changes rather than change scores for two-time-point data, we predicted the outcome variable at Time 2 while statistically controlling for the corresponding variable at Time 1. This approach controls for between-subject effects and predicts the change in each outcome variable. We accordingly entered the predictor variables into the regression separately for both measurement times. Thereby, the effect of Time 2 indicates the influence of the change in the predictor on the change in the outcome variable. For example, when testing the hypotheses, the effect of career insecurity at Time 2 is particularly important because this predictor represents a within-subject effect, which allows initial conclusions to be drawn about causality (Cohen et al., 2003).

Results

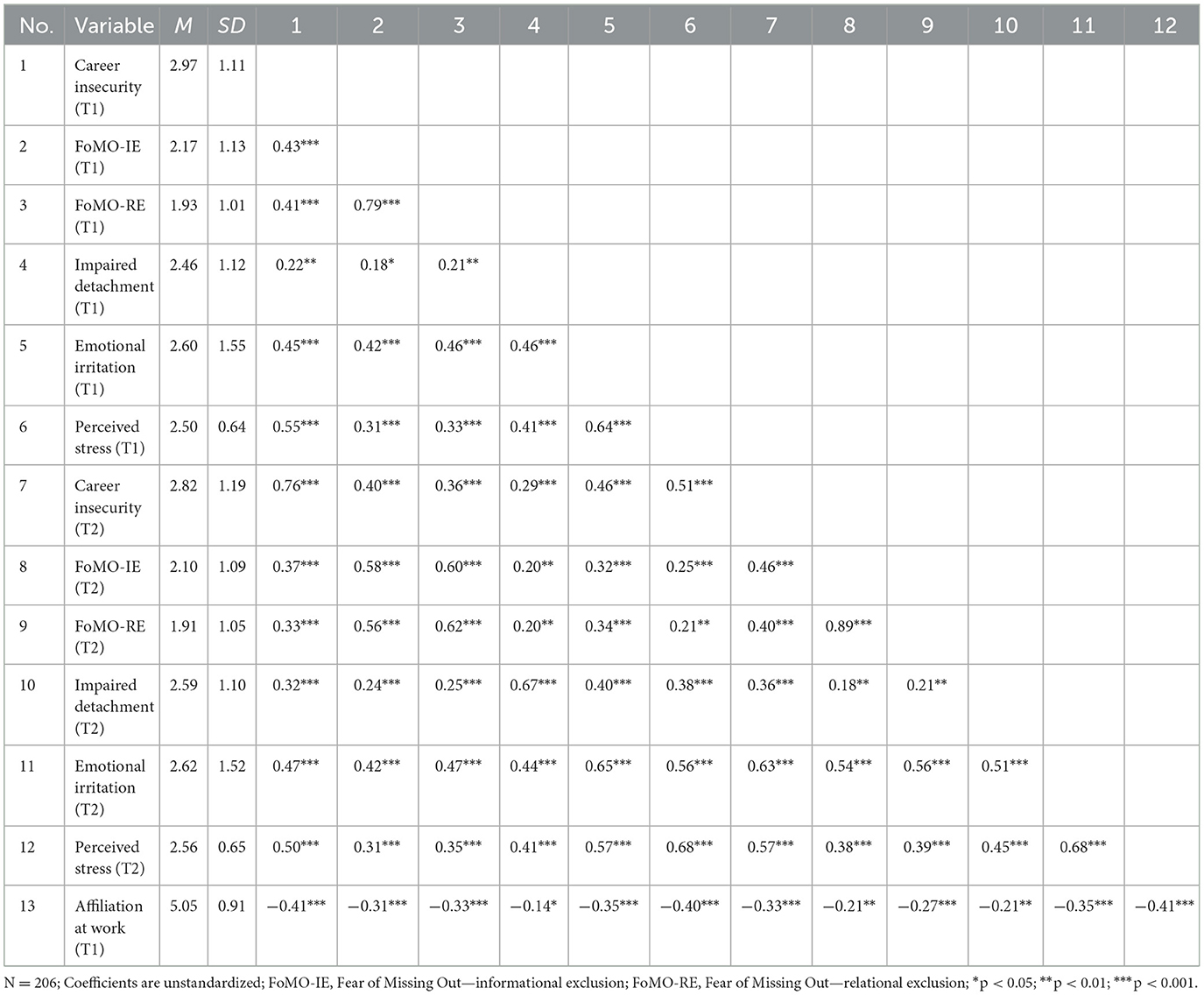

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the study variables. Central to our hypotheses, career insecurity at T1 and at T2 correlated positively with both FoMO facets at T1 and T2. Both facets of FoMO correlated significantly with all outcomes indicating well-being impairments in the hypothesized directions. Affiliation correlated negatively with career insecurity, FoMO at work, and the well-being outcomes, suggesting buffering potential.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2).

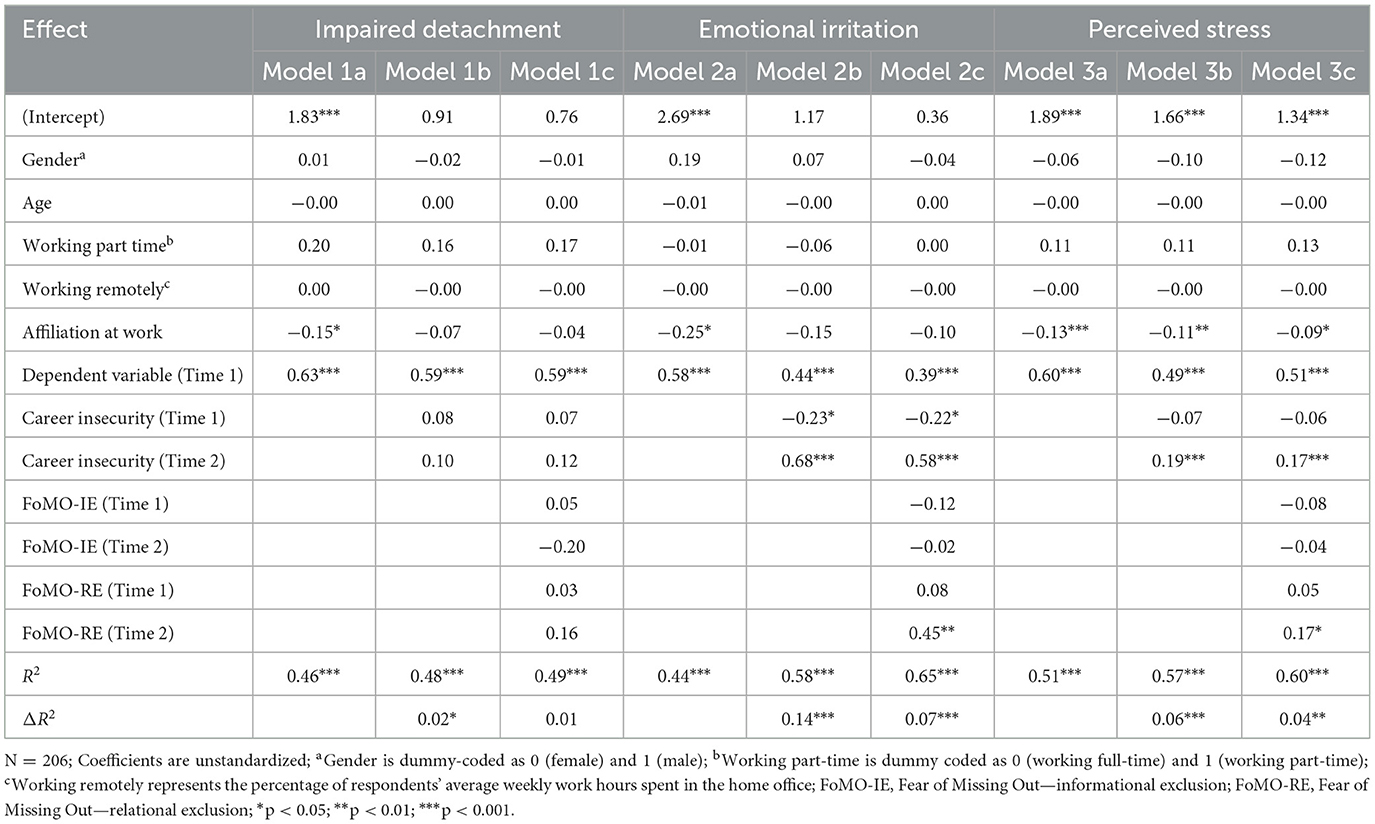

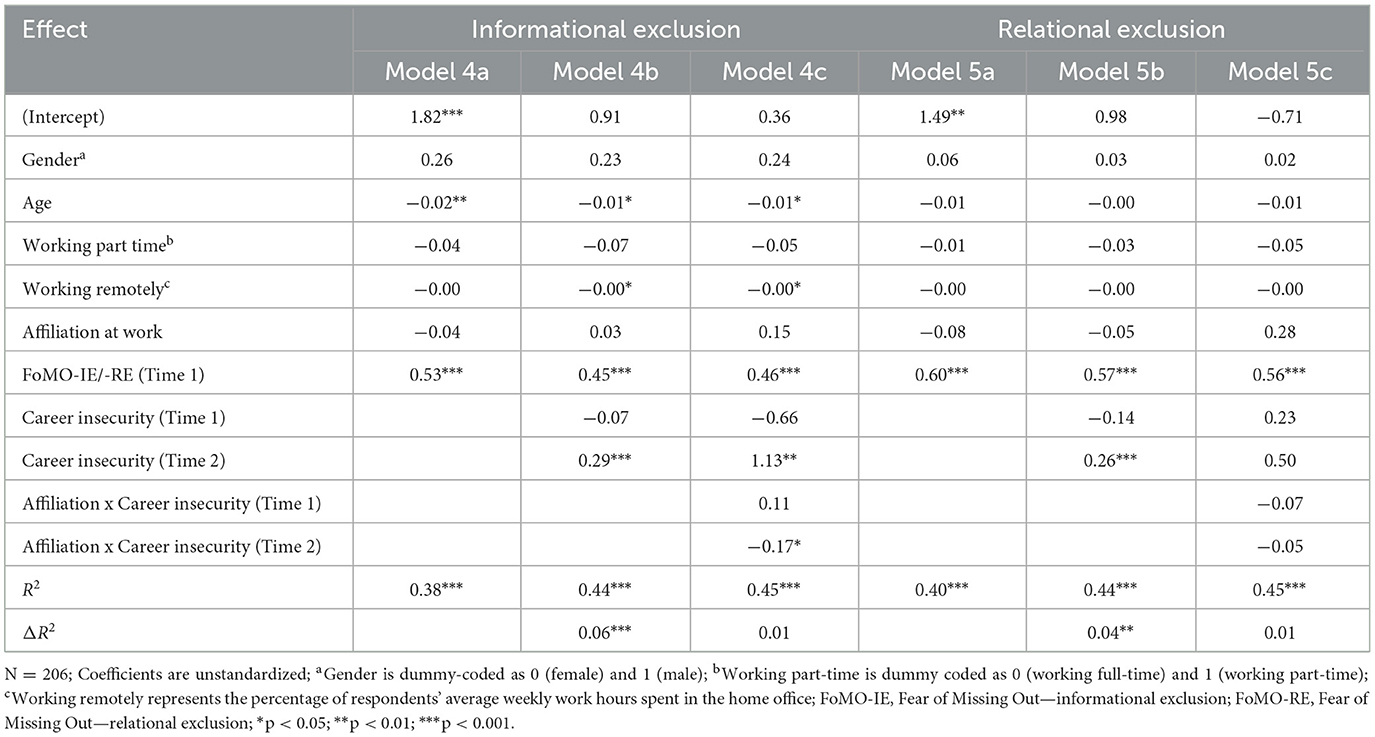

Tables 2, 3 present hierarchical regression models that predict the outcome variables at Time 2. In all models, we first included the control variables of gender, age, working part-time, working remotely, and affiliation at work. We also included the Time 1 measure of the respective outcome variable; while controlling for T1, the regression models predict change in the respective criterion variable.

Table 2. Hierarchical regression analyses for career insecurity and FoMO at Work predicting detachment, irritation, and stress.

Table 3. Hierarchical regression analyses for career insecurity predicting FoMO at Work moderated by affiliation at work.

Career insecurity and psychological impairment

To validate previous research, we tested a replication hypothesis positing that career insecurity should be positively associated with impaired detachment (H1a), emotional irritation (H1b), and perceived stress (H1c). To test Hypothesis H1a, we conducted a hierarchical regression analysis predicting impaired detachment at Time 2 (cf. Table 2). In Model 1a, we included the control variables and impaired detachment at Time 1 to predict changes in impaired detachment at Time 2. In Model 1b, we included career insecurity at Time 1 and Time 2. However, neither the initial level of career insecurity at Time 1, b = 0.08, p = 0.333, nor career insecurity at Time 2, b = 0.10, p = 0.191, affected detachment impairments from work at Time 2. Thus, Hypothesis H1a was not supported. Hypothesis H1b predicted that an increase in career insecurity would be positively associated with emotional irritation (cf. Table 2). Model 2b, which included career insecurity at Time 1 and Time 2, revealed a positive relationship between career insecurity at Time 2 and emotional irritation at Time 2, b = 0.68, p = 0.007. This result supports Hypothesis H1b, indicating that an increase in career insecurity is associated with an increase in emotional irritation. Hypothesis H1c proposed that an increase in career insecurity is positively associated with an increase in perceived stress (cf. Table 2). The results of Model 3b supported this hypothesis, indicating that career insecurity at Time 2 was positively related to perceived stress at Time 2, b = 0.19, p < 0.001. Thus, an increase in career insecurity was found to be associated with an increase in perceived stress.

In summary, although career insecurity was not significantly associated with impaired detachment (H1a), an increase in career insecurity was positively associated with greater emotional irritation (H1b) and perceived stress (Hypothesis H1c), demonstrating the negative relationship between career insecurity and psychological well-being.

Career insecurity and FoMO at Work

Hypothesis 2 proposes that an individual's career insecurity predicts would be positively associated with FoMO at work. We conducted two hierarchical regression analyses to predict the two dimensions of FoMO at work, informational and relational exclusion (cf. Table 3). Regarding informational exclusion, career insecurity at Time 2 was positively associated with an increase in informational exclusion at Time 2, b = 0.29, p < 0.001 (Model 4b), confirming Hypothesis H2a. Regarding relational exclusion, career insecurity at Time 2 was associated with an increase in relational exclusion at Time 2, b = 0.26, p < 0.001 (Model 5b), supporting Hypothesis H2b. Overall, an increase in career insecurity was positively associated with an increase in both informational and relational FoMO at work.

FoMO at Work and psychological impairment

Hypotheses 3 and 4 further posit that an increase in FoMO at work is positively associated to impaired detachment, emotional irritation, and perceived stress. To test these hypotheses, we included the subdimensions of FoMO for Time 2 while statistically controlling for Time 1 (cf. Table 2, Models 1c, 2c, and 3c). However, informational FoMO at Time 2 was not associated with impaired detachment at Time 2, b = −0.20, p = 0.105, emotional irritation at Time 2, b = −0.02, p = 0.905, or perceived stress at Time 2, b = −0.04, p = 0.571. Hypotheses H3a through H3c were accordingly not supported. Regarding relational exclusion at Time 2, there was no relationship with impaired detachment at Time 2, b = 0.16, p = 0.222, rejecting Hypothesis 4a. However, relational exclusion at Time 2 predicted emotional irritation at Time 2, b = 0.45, p = 0.003, and perceived stress at Time 2, b = 0.17, p = 0.028 (cf. Table 2). Therefore, hypotheses H4b and H4c were supported, indicating that individuals experience increased emotional irritation and stress when they become more concerned about being excluded from relational resources at work.

FoMO at Work as mediator

Combining Hypothesis 2 with hypotheses 3 and 4 suggests that career insecurity is indirectly associated with changes in our measures of psychological well-being through FoMO at work. Therefore, we tested for indirect effects by including all control variables and examining the effects of the predictor, mediator, and outcome variables at Time 2, while statistically controlling for Time 1. After combining the effects predicted by hypotheses H2b with H4b and H4c, we found significant positive indirect effects of career insecurity on emotional irritation and perceived stress via relational FoMO. The indirect effect on emotional irritation was b = 0.12, 95% CI [0.018, 0.275], and the indirect effect on perceived stress was b = 0.05, 95% CI [0.007, 0.091].

Affiliation at work as moderator

Finally, Hypothesis 5 posits that the affiliation at work mitigates the association between career insecurity and FoMO at work. We tested this hypothesis for the two dimensions of FoMO at work as shown in Table 3. Regarding informational exclusion, the results revealed a negative interaction between affiliation at work and career insecurity at Time 2, b = −0.17, p = 0.036 (cf. Model 4c). Thus, the effect of career insecurity on informational FoMO at Time 2 is weaker when the affiliation at work is stronger, confirming Hypothesis H5a (cf. Figure 2). Regarding relational exclusion, the interaction between affiliation at work and career insecurity at Time 2 was not significant, b = −0.05, p = 0.493 (cf. Model 5c), contradicting Hypothesis H5b. In summary, affiliation at work moderated the relationship between career insecurity and informational exclusion. These results indicate that individuals with higher levels of affiliation at work experience less FoMO on informational resources at work compared to those with lower levels.

Figure 2. Interaction effect of career insecurity and affiliation at work on informational exclusion.

Discussion

The study aimed to introduce the concept of FoMO at work as a quasi-natural experience for individuals with career insecurity and to investigate whether affiliation at work prevents its emergence. In line with previous findings on the well-being impairing effects of career insecurity, we found that career insecurity is positively associated with increased emotional irritation and perceived stress. Furthermore, the results revealed that an increase in career insecurity predicts an increase in Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) at work, which in turn was related to impairments in psychological well-being. More specifically, an increase in career insecurity was indirectly associated with short term irritability and perceived stress via worries about not having access to relational resources (relational FoMO). These results suggest that the fear of missing out on important social and professional interactions may exacerbate stress in contexts of career insecurity. Turning to protective factors, a stronger sense of belonging and experiences of inclusion—in other words: a solid affiliation at work—were found to protect against concerns about missing career-relevant updates, news, and information.

The findings demonstrate that adopting a resource-based perspective improves our understanding of how career insecurity affects psychological well-being while incorporating FoMO at work into the career context: According to the theory, career insecurity is perceived as a threat to resources, which prompts individuals to behave in ways that maintain resources or protect against resource loss. Since career insecurity is a macro-level threat beyond the control of individuals (Halbesleben et al., 2014), the focus shifts to micro-level resources that are more easily influenced, acquired, and protected. These resources are of informational and relational nature. Therefore, conceptualizing FoMO at work as a fear response to the perceived threat of resource loss stemming from career insecurity is a valuable addition to the existing literature.

Furthermore, affiliation at work was shown to reduce informational FoMO (fear of missing out on career-relevant news and updates) triggered by career insecurity. This confirms the observation that, in modern work environments such as those of the knowledge workers in this study, the perception of connectedness as expressed through the satisfaction of employees' wish for affiliation at work is a significant pathway through which individuals perceive access to career resources. This underscores the practical benefits of maintaining strong interpersonal relationships in the face of career insecurity. In practice, individuals seem to perceive their informational career resources as contingent on their integration into their workgroups and organizational networks. Consequently, they may experience heightened psychological stress when feeling socially isolated, as social integration enables informal knowledge sharing, access to insider information, and other career opportunities, that are mainly shared informally during day-to-day social interactions.

Theoretical implications

The primary objective of the study was to incorporate FoMO at work into the career literature. A noteworthy innovation was the investigation of FoMO at work as opposed to the prevailing emphasis on considering (and measuring) media-related FoMO. This perspective aligns with previous research on the importance of informational and relational resources gained through social connections in the workplace (Seibert et al., 2001) and draws on COR theory.

According to COR theory, an insecure career context impairs psychological well-being by threatening important resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018): Career insecurity reflects economic threats, threats to one's career goals, or even threats of not having a fulfilling live, and thus transforms the current career environment into one “in which there is the threat of a net loss of resources” (Hobfoll, 1989, p. 516). However, the absence of a significant relationship between career insecurity and impaired detachment may initially seem to contradict the proposed sequential stages of stress development in this regard. Nevertheless, this null finding actually sharpens our understanding of how career insecurity affects psychological functioning. Specifically, it suggests that detachment is not the earliest or most sensitive indicator of stress in the context of career threats. One possibility is that employees facing career insecurity may attempt to overcompensate by mentally disengaging from work in their off-hours. Alternatively, individuals may appraise the threat of career insecurity as abstract or long-term, not triggering the type of immediate task-focused rumination that impairs detachment. In this sense, emotional and general stress reactions such as irritation and perceived stress appear to accumulate beneath the surface when career insecurity is present.

Further aligning with COR theory, which states that especially in the context of resource loss the importance of acquiring resources increases, an insecure career context was posited to increase the subjective importance of resources explaining why FoMO at work emerges. Specifically, individuals with career insecurity fear missing out on know-whom competencies and know-how competencies. The former provide access to information, influence, guidance, and support, while the latter provide job-related knowledge (DeFillippi and Arthur, 1994). Both competencies are relevant career resources as means for achieving better career security (Spurk et al., 2016). However, the findings reveal an important distinction between informational and relational FoMO. First, the non-significant effects of informational FoMO on psychological distress suggest that the fear of missing work- and task-related information does not represent potential threats to resources. Rather, the fear of not having access to, or missing out on opportunities to build and expand one's extra-organizational networks leads to emotional strain and perceived stress, signifying those resources as more valued in light of career insecurity. This finding aligns with COR theory's principle that scarce, difficult-to-replace resources generate greater psychological distress when threatened (Hobfoll, 1989). Extra-organizational networks represent particularly valuable yet unpredictable career resources, with networking opportunities that are often irreplaceable once missed. Information resources that are anchored in a structured organizational context, on the other hand, seem to be experienced as a matter of individuals' agency in informational needs and thus more controllable and predictable, reducing threat to resources.

The differentiated psychological consequences of relational vs. informational FoMO become particularly salient when interpreted through the proposed three-stage stress development: impaired detachment, emotional irritation, and perceived stress. First, the lack of significant findings for impaired detachment—both in direct response to career insecurity and via either form of FoMO—suggests that the initial phase of psychological strain characterized by work-related thoughts intruding into personal time, is not the most sensitive indicator of FoMO-induced stress. The data further show that relational FoMO significantly predicts emotional irritation, while informational FoMO does not. This suggests that relational FoMO may bypass the cognitive intrusion phase and exert its influence more directly on emotional states which supports the idea that it is not just the presence of resource-related fears that matters, but what type of resource is at stake. Relational FoMO, grounded in fears of exclusion from status-bearing, opportunity-rich networks, appears to trigger a strong affective reaction. In line with our interpretive framework, this indicates that relational FoMO activates the affective spillover that occurs when career threats penetrate emotional boundaries, leading to irritability and dysregulated mood. Likewise, perceived stress—the generalization of work-related strain into broader psychological stress—is also uniquely predicted by relational FoMO. This final stage of the stress trajectory reflects a loss of resource security that extends beyond the workplace. FoMO appears to translate career-related fear into a more global state of stress. Again, informational FoMO fails to exert this influence, further emphasizing its limited psychological impact in this trajectory, which has implications for future research. For example, the absence of an effect on detachment raises the possibility that relational FoMO operates outside traditional cognitive stress markers and demands greater focus on affective and existential dimensions of strain. Longitudinal research could explore, for example, whether persistent relational FoMO erodes affective resilience over time.

Finally, and consistent with previous findings regarding social integration at work as a career resource, affiliation was found to mitigate the effect of career insecurity on informational FoMO at work but surprisingly not on relational FoMO. Thus, a strong sense of belonging within one's immediate work group protects against the fear of missing out on task-relevant information, but fails to mitigate anxiety over missed networking opportunities. From a Conservation of Resources perspective, group inclusion thus operates as a conditional resource that facilitates the flow of task-relevant knowledge and updates. In contrast, cultivating new or broader professional networks requires actively investing time, effort, and social capital beyond one's immediate work group. Even in an environment of high group inclusion, employees must invest beyond their established group to cultivate a broader professional network. Therefore, affiliation with one's work group and proximal inner-organizational networks does not seem to open the necessary passageway for acquiring new relational resources, and consequently does not buffer the relationship between career insecurity and relational Fear of Missing Out. Future research should thus consider expanding the current theoretical and empirical understanding of FoMO at work in a more nuanced way. This research should also align with career resources frameworks (e.g., Hirschi et al., 2018) in order to adapt this newly labeled phenomenon to individuals' work realities in today's career contexts.

Limitations

Although this study had some strengths, its limitations should be considered. First, the study relied on voluntary participation, where individuals who are more motivated or opinioned are more likely to respond. Furthermore, the participants were pre-selected based on eligibility criteria such as a computer- or laptop-based job, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, the findings are assumed to be valid for employees in knowledge occupations, which is noteworthy given that they comprise over 36% of the total employed population both in the EU and the USA (Research and Innovation Observatory, 2017).

From a methodological standpoint, the study relied on self-report measures at two time points, which may have introduced social desirability bias and common method bias. The two-wave design with a 3-week interval captures short-term dynamics, which limits the understanding of longer-term changes. Nevertheless, this design yields immediate associations and potential causal insights, thereby contributing to the literature on career insecurity, FoMO at work, and psychological well-being. However, future research could benefit from incorporating longer follow-up periods to capture interactions over time.

Finally, to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of how career insecurity affects psychological well-being while stimulating the fear of missing out on career-resources, future studies might explore additional influential factors. Specifically, the characteristics of individuals' professional networks (e.g., size, composition, and heterogeneity) and their networking behaviors could provide valuable insights into how and when affiliation at work interacts with career insecurity and relates to FoMO at work.

Practical implications

Practical implications are derived from the elaboration of three questions. The first question is how to reduce career insecurity and thus reduce its negative impact on psychological well-being. Interestingly, working part-time or remotely did not significantly impact individuals' self-reported fear of missing out on career-related opportunities. This suggests that these working conditions do not exacerbate concerns arising from career insecurity. However, the study found that the two facets of FoMO at work were strongly related, indicating that career insecurity creates a general fear of missing out on career opportunities. Organizations can address this issue by providing clear career development paths and measures that promote employees' (perception of) internal and external marketability (Spurk et al., 2016).

The second question to consider is how to counteract relational fear of missing out on professional relationships, since relational FoMO was found to be a significant predictor of psychological stress. One effective measure is to incorporate employee career development into management tasks, particularly focusing on strengthening employees' career-relevant networks. Mentoring programs seem valuable in this regard, benefiting both employees and the organization (Singh et al., 2009).

A third question that arises is how to satisfy workers' affiliation motives at work. Since connectedness is a subjective need, providing a range of opportunities for employees to interact with others helps meeting individual preferences. Given the increasing prevalence of remote work, it is essential to facilitate interaction, communication, and relationship-building among employees, even when they are physically distant (e.g., Barker Scott and Manning, 2024). Examples include maintaining and encouraging engagement on social interaction platforms, holding virtual team activities, forming employee resource groups, conducting regular one-on-one check-ins with managers, and assigning collaborative tasks between different sub-teams. This way, organizations can help to ensure that each employee can find a way to satisfy their social needs in a way that works for them.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Participants provided informed consent after being briefed on data-protection measures and applicable legal regulations. Data collection was performed completely anonymously, in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. The first author ensured full compliance with all guidelines of her school's ethics committee.

Author contributions

KE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was partially supported by the Universitätsbund Erlangen-Nürnberg. The funder provided financial support for collecting the data. The funder had no role in study design, analysis, or publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alisic, A., and Wiese, B. S. (2020). Keeping an insecure career under control: the longitudinal interplay of career insecurity, self-management, and self-efficacy. J. Vocat. Behav. 120:103431. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103431

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: a motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 34, 2045–2068. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02690.x

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 273–285. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000056

Barker Scott, B. A., and Manning, M. R. (2024). Designing the collaborative organization: a framework for how collaborative work, relationships, and behaviors generate collaborative capacity. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 60, 149–193. doi: 10.1177/00218863221106245

Beyens, I., Frison, E., and Eggermont, S. (2016). “I don't want to miss a thing”: adolescents' fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents' social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Comput. Human Behav. 64, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.083

Blackwell, D., Leaman, C., Tramposch, R., Osborne, C., and Liss, M. (2017). Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Pers. Individ. Dif. 116, 69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.039

Budnick, C. J., Rogers, A. P., and Barber, L. K. (2020). The fear of missing out at work: examining costs and benefits to employee health and motivation. Comput. Human Behav. 104:106161. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.106161

Callanan, G. A., Perri, D. F., and Tomkowicz, S. M. (2017). Career management in uncertain times: challenges and opportunities. Career Dev. Q. 65, 353–365. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12113

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., and Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd Edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., and Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 386–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404

Colakoglu, S. N. (2011). The impact of career boundarylessness on subjective career success: the role of career competencies, career autonomy, and career insecurity. J. Vocat. Behav. 79, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.09.011

Cropley, M., and Zijlstra, F. R. H. (2011). “Work and rumination,” in Handbook of Stress in the Occupations, eds. J. Langan-Fox and C. L. Cooper (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 487–501. doi: 10.4337/9780857931153.00060

Dahling, J. J., and Lauricella, T. K. (2017). Linking job design to subjective career success: a test of self-determination theory. J. Career Assess. 25, 371–388. doi: 10.1177/1069072716639689

De Cuyper, N., Mäkikangas, A., Kinnunen, U., Mauno, S., and Witte, H. D. (2012). Cross-lagged associations between perceived external employability, job insecurity, and exhaustion: testing gain and loss spirals according to the conservation of resources theory. J. Organ. Behav. 33, 770–788. doi: 10.1002/job.1800

de Jonge, J., and Dormann, C. (2006). Stressors, resources, and strain at work: a longitudinal test of the triple-match principle. J. Appl. Psychol. 91, 1359–1374. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1359

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., and Vansteenkiste, M. (2008). “Self-determination theory and the explanatory role of psychological needs in human well-being,” in Capabilities and Happiness, eds. L. Bruni and F. Comim (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 187–223. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780199532148.003.0009

DeFillippi, R. J., and Arthur, M. B. (1994). The boundaryless career: a competency-based perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 15, 307–324. doi: 10.1002/job.4030150403

Dormann, C., and Zapf, D. (2002). Social stressors at work, irritation, and depressive symptoms: accounting for unmeasured third variables in a multi-wave study. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 75, 33–58. doi: 10.1348/096317902167630

Dose, E., Desrumaux, P., and Bernaud, J. L. (2019). Effects of perceived organizational support on objective and subjective career success via need satisfaction: a study among French psychologists. J. Employ. Counsel. 56, 144–163. doi: 10.1002/joec.12130

Ebner, K., Soucek, R., and Iliescu, D. (2025a). A Psychometric Examination of the Workplace Fear of Missing Out Scale in German-Speaking Employees. Manuscript in preparation.

Ebner, K., Wehrt, W., and Soucek, R. (2025b). Navigating stress in the multi-device, multi-channel work environment: the role of subjective interruptedness and Fear of Missing Out at work. Int. J. Workplace Health Manage. doi: 10.1108/IJWHM-12-2024-0249. [Epub ahead of print].

Elhai, J. D., Dvorak, R. D., Levine, J. C., and Hall, B. J. (2017). Problematic smartphone use: a conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 207, 251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.030

Giunchi, M., Emanuel, F., Chambel, M. J., and Ghislieri, C. (2016). Job insecurity, workload and job exhaustion in temporary agency workers (TAWs): gender differences. Career Dev. Int. 21, 3–18. doi: 10.1108/CDI-07-2015-0103

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., and Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manage. 40, 1334–1364. doi: 10.1177/0149206314527130

Hirschi, A., Nagy, N., Baumeler, F., Johnston, C. S., and Spurk, D. (2018). Assessing key predictors of career success: development and validation of the career resources questionnaire. J. Career Assess. 26, 338–358. doi: 10.1177/1069072717695584

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychologist 44, 513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 50, 337–421. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 84, 116–122. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

Hobfoll, S. E. (2012). Conservation of resources and disaster in cultural context: the caravans and passageways for resources. Psychiatry Interpersonal Biol. Processes 75, 227–232. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2012.75.3.227

Hobfoll, S. E., and Ford, J. S. (2007). “Conservation of resources theory,” in Encyclopedia of Stress, Vol. 51, Issue 4, ed. G. Fink (Cambridge, MA: Elsevier), 562–567. doi: 10.1016/B978-012373947-6.00093-3

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., and Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5, 103–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Höge, T., Brucculeri, A., and Iwanowa, A. N. (2012). Karriereunsicherheit, Zielkonflikte und Wohlbefinden bei Nachwuchswissenschaftlerinnen und -wissenschaftlern. Zeitschrift Arbeits Organisationspsychologie 56, 159–172. doi: 10.1026/0932-4089/a000088

Holding, A. C., St-Jacques, A., Verner-Filion, J., Kachanoff, F., and Koestner, R. (2020). Sacrifice – but at what price? A longitudinal study of young adults' sacrifice of basic psychological needs in pursuit of career goals. Motivation Emotion 44, 99–115. doi: 10.1007/s11031-019-09777-7

Holmgreen, L., Tirone, V., Gerhart, J., and Hobfoll, S. E. (2017). “Conservation of resources theory: resource caravans and passageways in health contexts,” in The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide to Research and Practice, eds. C. L. Cooper and J. C. Quick (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell), 443–457. doi: 10.1002/9781118993811.ch27

Iliescu, D., Macsinga, I., Sulea, C., Fischmann, G., Vander Elst, T., and De Witte, H. (2017). The five-factor traits as moderators between job insecurity and health: a vulnerability-stress perspective. Career Dev. Int. 22, 399–418. doi: 10.1108/CDI-08-2016-0146

Jiang, L., Debus, M. E., Xu, X., Hu, X., Lopez-Bohle, S., Petitta, L., et al. (2025). Preparing for a rainy day: a regulatory focus perspective on job insecurity and proactive career behaviors. Appl. Psychol. 74:e70004. doi: 10.1111/apps.70004

Kenrick, D. T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S. L., and Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the pyramid of needs: contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 5, 292–314. doi: 10.1177/1745691610369469

Klein, E. M., Brähler, E., Dreier, M., Reinecke, L., Müller, K. W., Schmutzer, G., et al. (2016). The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale–psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry 16:159. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0875-9

Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Lee, D. S., Lin, N., et al. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE 8:e69841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069841

Llosa, J. A., Menéndez-Espina, S., Agulló-Tomás, E., and Rodríguez-Suárez, J. (2018). Job insecurity and mental health: a meta-analytical review of the consequences of precarious work in clinical disorders. Anales Psicología 34, 211–223. doi: 10.6018/analesps.34.2.281651

Lüdecke, D., Ben-Shachar, M., Patil, I., Waggoner, P., and Makowski, D. (2021). Performance: an R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J. Open Source Softw. 6:3139. doi: 10.21105/joss.03139

McClelland, D. C., and Jemmott, J. B. III (1980). Power motivation, stress and physical illness. J. Human Stress 6, 6–15. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1980.9936101

Menéndez-Espina, S., Llosa, J. A., Agulló-Tomás, E., Rodríguez-Suárez, J., Sáiz-Villar, R., and Lahseras-Díez, H. F. (2019). Job insecurity and mental health: the moderating role of coping strategies from a gender perspective. Front. Psychol. 10:286. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00286

Milyavskaya, M., Saffran, M., Hope, N., and Koestner, R. (2018). Fear of missing out: prevalence, dynamics, and consequences of experiencing FOMO. Motiv. Emot. 42, 725–737. doi: 10.1007/s11031-018-9683-5

Mohr, G., Müller, A., Rigotti, T., Aycan, Z., and Tschan, F. (2006). The assessment of psychological strain in work contexts: concerning the structural equivalency of nine language adaptations of the irritation scale. Euro. J. Psychol. Assess. 22, 198–206. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.22.3.198

Mohr, G., Rigotti, T., and Müller, A. (2005). Irritation – Ein Instrument zur Erfassung psychischer Beanspruchung im Arbeitskontext. Skalen- und Itemparameter aus 15 Studien. Zeitschrift Arbeits Organisationspsychologie 49, 44–48. doi: 10.1026/0932-4089.49.1.44

Naswall, K., Sverke, M., and Hellgren, J. (2005). The moderating effects of work-based and non-work based support on the relation between job insecurity and subsequent strain. SA J. Indus. Psychol. 31, 57–64. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v31i4.214

Neel, R., Kenrick, D. T., White, A. E., and Neuberg, S. L. (2016). Individual differences in fundamental social motives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 110, 887–907. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000068

Ng, T. W., and Feldman, D. C. (2014). Subjective career success: a meta-analytic review. J. Vocat. Behav. 85, 169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.06.001

Nielsen, K., Nielsen, M. B., Ogbonnaya, C., Känsälä, M., Saari, E., and Isaksson, K. (2017). Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Work Stress 31, 101–120. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2017.1304463

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., and Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Human Behav. 29, 1841–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

R Core Team (2022). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed January, 13, 2023).

Research and Innovation Observatory (2017). Knowledge-Intensive Activities as a Percentage of Total Employment. Available online at: https://elobservatoriosocial.fundacionlacaixa.org/en/-/employment_kia (Accessed June 6, 2024).

Schaller, M., Kenrick, D. T., Neel, R., and Neuberg, S. L. (2017). Evolution and human motivation: a fundamental motives framework. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 11:e12319. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12319

Schneider, E. E., Schönfelder, S., Domke-Wolf, M., and Wessa, M. (2020). Measuring stress in clinical and nonclinical subjects using a German adaptation of the Perceived Stress Scale. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 20, 173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.03.004

Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., and Liden, R. C. (2001). A social capital theory of career success. Acad. Manage. J. 44, 219–237. doi: 10.2307/3069452

Shatz, I. (2023). Assumption-checking rather than (just) testing: the importance of visualization and effect size in statistical diagnostics. Behav. Res. Methods 56, 826–845. doi: 10.3758/s13428-023-02072-x

Sheldon, K. M. (2011). Integrating behavioral-motive and experiential-requirement perspectives on psychological needs: a two process model. Psychol. Rev. 118, 552–569. doi: 10.1037/a0024758

Sheldon, K. M., and Gunz, A. (2009). Psychological needs as basic motives, not just experiential requirements. J. Pers. 77, 1467–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00589.x

Singh, R., Ragins, B. R., and Tharenou, P. (2009). What matters most? The relative role of mentoring and career capital in career success. J. Vocational Behav. 75, 56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.03.003

Sonnentag, S., and Bayer, U. V. (2005). Switching off mentally: redictors and consequences of psychological detachment from work during off-job time. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 10, 393–414. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.393

Sonnentag, S., and Fritz, C. (2007). The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 12, 204–221. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204

Sonnentag, S., and Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: the stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. J. Organ. Behav. 36, S72–S103. doi: 10.1002/job.1924

Sonnentag, S., Venz, L., and Casper, A. (2017). Advances in recovery research: what have we learned? What should be done next? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 365–380. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000079

Spurk, D., Hofer, A., Hirschi, A., De Cuyper, N., and De Witte, H. (2022). Conceptualizing career insecurity: toward a better understanding and measurement of a multidimensional construct. Pers. Psychol. 75, 253–294. doi: 10.1111/peps.12493

Spurk, D., Kauffeld, S., Meinecke, A. L., and Ebner, K. (2016). Why do adaptable people feel less insecure? Indirect effects of career adaptability on job and career insecurity via two types of perceived marketability. J. Career Assess. 24, 289–306. doi: 10.1177/1069072715580415

Steiner, T. H., Bekk, M., Moser, K., and Spörrle, M. (2025). Fundamental Social Motives Inventory in German: A Short Measurement to Assess Fundamental Social Motives. Manuscript in preparation.

Sullivan, S. E., and Al Ariss, A. (2022). A conservation of resources approach to inter-role career transitions. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 32:100852. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2021.100852

Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., and Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work-home interface: the work-home resources model. Am. Psychol. 67, 545–556. doi: 10.1037/a0027974

Van den Broeck, A., Vansteenkiste, M., De Witte, H., and Lens, W. (2008). Explaining the relationships between job characteristics, burnout, and engagement: the role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Work Stress 22, 277–294. doi: 10.1080/02678370802393672

Westman, M., Hobfoll, S. E., Chen, S., Davidson, O. B., and Laski, S. (2004). “Organizational stress through the lens of conservation of resources (COR) theory,” in Research in Occupational Stress and Well-being: Vol. 4. Interpersonal Dynamics, eds. P. L. Perrewé and D. C. Ganster (Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing), 167–220. doi: 10.1016/S1479-3555(04)04005-3

Keywords: career insecurity, Fear of Missing Out at Work, stress, irritation, detachment, affiliation

Citation: Ebner K, Soucek R and Steiner TH (2025) Fear of Missing Out at Work in times of career insecurity: well-being impairments and affiliation as buffer. Front. Organ. Psychol. 3:1469769. doi: 10.3389/forgp.2025.1469769

Received: 24 July 2024; Accepted: 04 July 2025;

Published: 30 July 2025.

Edited by:

Shaozhuang Ma, University Institute of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Ranjita Islam, Queensland University of Technology, AustraliaAnggara Wisesa, Bandung Institute of Technology, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Ebner, Soucek and Steiner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katharina Ebner, a2F0aGFyaW5hLmVibmVyQGZhdS5kZQ==

Katharina Ebner

Katharina Ebner Roman Soucek

Roman Soucek Thomas Heinrich Steiner

Thomas Heinrich Steiner