- 1Department of Psychology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States

- 2Canadore College, North Bay, ON, Canada

- 3Department of Psychology, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, IA, Canada

Systemic racism—the institutional and structural exclusion of and bias against people of color—negatively affects Black Americans. The present research seeks to address how beliefs about the permanence of systemic racism impact Black Americans' intentions to engage in collective action. In Study 1 we validate a scale measuring perceptions of the permanence of systemic racism (PSR). In Study 2, we found that the more that Black Americans perceive systemic racism to be permanent, the lower their intentions to engage in collective action. In Study 3, Black Americans attention to current events during a period when antiracist movement related to their beliefs in the permanence of systemic racism and their intentions to engage in collective action. In Study 4 we find that Black Americans who believe systemic racism is more permanent are more likely to perceive social justice actions and policies as ineffective and therefore indicate lesser intentions to support these efforts, suggesting that believing that systemic racism is permanent may undermine intentions to engage in anti-racist activities through undermining beliefs in their effectiveness.

Introduction

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” - Baldwin (1962)

James Baldwin reminds us that we must face and acknowledge the deep-rooted systemic racism in America before we can dismantle it. However, once acknowledged, a critical question remains: do we believe it can be changed?

Some scholars argue that racism is a permanent feature of the American sociopolitical system (Bell, 1992; Wilderson III, 2020). They point to historical patterns in which overturned racist institutions are replaced by new ones that maintain racial hierarchies. These patterns invite divergent interpretations—individuals vary in their beliefs about whether systemic racism is malleable or permanent. These beliefs, we argue, are distinct from beliefs about the malleability of individual prejudice (Ivy, 2024; Wilmot, 2019). Whereas, beliefs about individual prejudice focus on whether biased attitudes can be changed through education or interpersonal contact, beliefs about systemic racism concern whether structural inequalities can be dismantled through collective effort to remove ethnocentric biases from policies and institutions and address the legacy of generational harms. This distinction is crucial because changing individual minds may feel achievable without large-scale mobilization, whereas changing systems often requires coordinated, goal-directed action. As such, beliefs about the permanence of systemic racism may be more directly tied to individuals' motivation to engage in conventional collective action.

Beliefs about the permanence or malleability of traits shape motivation and behavior (Carr et al., 2012; Rattan and Dweck, 2010; Yeager and Dweck, 2012). When people believe traits are changeable, they tend to demonstrate greater resilience and goal pursuit; by contrast, beliefs in permanence can undermine motivation. For example, when minority-group members confront racism by a co-worker they have more pessimistic expectations about that co-worker's future behavior to the extent that they believe that individual racism is permanent (Rattan and Dweck, 2010). We extend this logic to systemic racism, proposing that people's beliefs about its malleability or permanence influence their willingness to confront it. When systemic racism is seen as changeable, individuals may feel empowered to act—pursuing goals, confronting injustice, and engaging in reformist activism. When seen as permanent, these actions may feel futile.

This idea builds on decades of research in psychology showing that people's beliefs about traits like intelligence, athleticism, or prejudice shape behavior (Chiu et al., 1997). Just as people are more motivated when they believe personal traits can change, we propose similar dynamics may apply to systems. However, the changeability of systemic racism is especially complex. Critical Race Theory (CRT), for example, argues that racism is embedded in systems and structures, not merely the result of individual biases (Bell, 1992). This systemic lens makes clear that racism can persist within the structures of the system even when individuals hold egalitarian beliefs (Bonilla-Silva, 2021; Murphy et al., 2018; Salter et al., 2018).

Systemic racism is defined as the institutional, cultural, and structural privilege of dominant racial groups, often through formal and informal policies, practices, and norms (Banaji et al., 2021; Payne and Hannay, 2021; Rucker and Richeson, 2021a). Such racism persists across domains—even in the absence of explicitly racist actors (Roithmayr, 2014; Bullard et al., 2007). It is therefore essential to distinguish racism at the individual and systemic level. A system can produce inequitable outcomes even when its individual actors are not consciously biased (Murphy et al., 2018). Moreover, individuals can unconsciously adopt and reproduce dominant ideologies that maintain systemic racism (Salter et al., 2018). People's beliefs about the permanence of systemic racism may be shaped by their lived experiences (Bonam et al., 2019). For example, Black Americans—who are frequent targets of systemic racism—may be more likely than White Americans to perceive systemic racism as permanent, and they may have a stronger recognition of the distinctions between individual and systemic racism.

We hypothesize that these perceptions have motivational consequences. When people view racism targeting their group as permanent, they may report lower efficacy and weaker intentions to engage in collective action. When people interpret their experiences as negative, global, and stable, motivation toward their goals tends to decline (Abramson et al., 1978). Racism, by its very nature, is perceived as negative and global—harming communities of color and infiltrating multiple American institutions and structures (Banaji et al., 2021). Research shows that when people perceive injustice as stable or unchangeable, they are more likely to rationalize existing inequalities and regard them as inevitable or justified (Kay et al., 2009; Laurin et al., 2013). These system-justifying beliefs may reduce motivation to challenge racism, particularly when the system is seen as fixed. However, we propose a boundary to this pattern. For members of groups who directly bear the burdens of systemic injustice—such as Black Americans—the costs of endorsing an unchangeable system may outweigh the psychological comfort of rationalization. In these cases, perceiving racism as permanent may not lead to system justification, but instead foster rejection of the system alongside pessimism about the prospects of systemic reform. This may be particularly true when reformist efforts appear ineffective, and when continued harm is clearly linked to system preservation.

In this paper, we explore how beliefs about the permanence of systemic racism influence Black Americans' motivation to engage in these various forms of collective action. People's beliefs about the permanence of systemic racism are not formed in a vacuum. When deciding whether to engage in antiracist or collective action, individuals often draw on cues from the current sociopolitical environment (Thomas and McGarty, 2009; van Zomeren et al., 2008). For example, people may consider whether recent news or events—such as trials, protests, policy changes, or political rhetoric—signal that systemic change is malleable or permanent. In addition, individuals may assess the efficacy of various forms of action; the perceived effectiveness of activism will likely relate to intentions to engage. Antiracist efforts vary in their strategies and goals—from conventional (e.g., police reform) to disruptive (e.g., abolitionist calls to defund or dismantle oppressive systems). We present two categories of social justice actions in the present research. Reformative or conventional actions seek to make favorable alterations to the system, but not drastically change or remove current systems entirely (Nielsen, 1971). The second type we highlight is disruptive actions which are more revolutionary and seek to tear down the current biased systems and rebuild more equitable systems in their place. Thus, beliefs about the permanence of racism may be connected to perceived societal momentum and beliefs about the strategic effectiveness of one's actions.

The current research

Psychological scholarship has historically focused on individual-level racism (Allport, 1954; Paluck et al., 2021). In the present work, we extend this focus by examining how lay beliefs about the permanence of systemic racism influence activism and policy support intentions.

First, we develop a scale for the measurement of system permanence beliefs in Study 1. Then in Study 2, we test whether beliefs about systemic racism predict Black Americans' intentions to engage in conventional collective action. In Study 3, we assess whether attention to real-world events during a period of heightened antiracist activism influences these beliefs and associated motivations. In Study 4, we investigate whether efficacy beliefs help explain the relationship between permanence beliefs and social justice intentions.

We hypothesize that: (1) perceiving systemic racism as permanent will be associated with lower intentions to participate in collective action (2) paying attention to current events during when systemic racism was being publicly confronted will be associated with lower permanence beliefs and greater willingness to engage in collective action; and (3) beliefs about the effectiveness of collective action will mediate the link between permanence beliefs and action intentions.

This research offers a novel contribution by applying mindset theory to the domain of systemic injustice—demonstrating that beliefs about the malleability of racism may shape individuals' motivation to challenge it. Across four studies, we explore whether and how these beliefs influence antiracist engagement, particularly among Black Americans. Understanding these beliefs has implications for social change efforts: if systemic racism is perceived as immovable, even well-intentioned individuals may disengage from activism. Recognizing the motivational impact of permanence beliefs can inform how scholars, educators, and advocates frame racial justice messaging.

Study 1

We assessed the psychometric properties of an eight-item Permanence of Systemic Racism (PSR) Scale, originally developed by Wilmot (2019) and modeled on Carr et al.'s (2012) measure of individual prejudice malleability. Items assess the extent to which participants view systemic racism as a fixed, enduring feature of society (e.g., “Racism cannot be removed from society;” see Supplementary Materials for full scale). Participants responded using a 6-point scale (1 = very strongly disagree to 6 = very strongly agree); higher scores indicate greater perceived permanence. Final analyses were conducted with a sample of 424 participants (61% women, 39% men; 54% White, 46% Black; Mage = 29.62, SDage = 8.25; see SOM for additional information). Internal consistency was high across the full sample (α = 0.83), as well as within both Black (α = 0.82) and White (α = 0.84) participants.

We hypothesized that Black and White Americans' beliefs about the permanence of systemic racism might differ. Specifically, because of Black Americans' lived experience confronting systemic racism, we reasoned that they would be more aware of the ways that racism persists in the system despite outward changes, and thus they would be more likely to perceive systemic racism as permanent compared to White Americans. Furthermore, because systemic racism has different implications for the life outcomes of Black Americans and White Americans, we hypothesized that their belief that systemic racism is permanent would have different associations with other attitudes and motivations for these two groups.

Measures

Discriminant and convergent validity measures. To establish discriminant and convergent validity of the system permanence beliefs scale, we included three well-established measures that perceptions of racism and the sociopolitical system: Theories of individual prejudice scale (Carr et al., 2012; α = 0.82), Social Dominance Orientation (Ho et al., 2015; α = 0.95), and System Justification scale (Kay and Jost, 2003; α = 0.84) (see SOM for measures).

Results

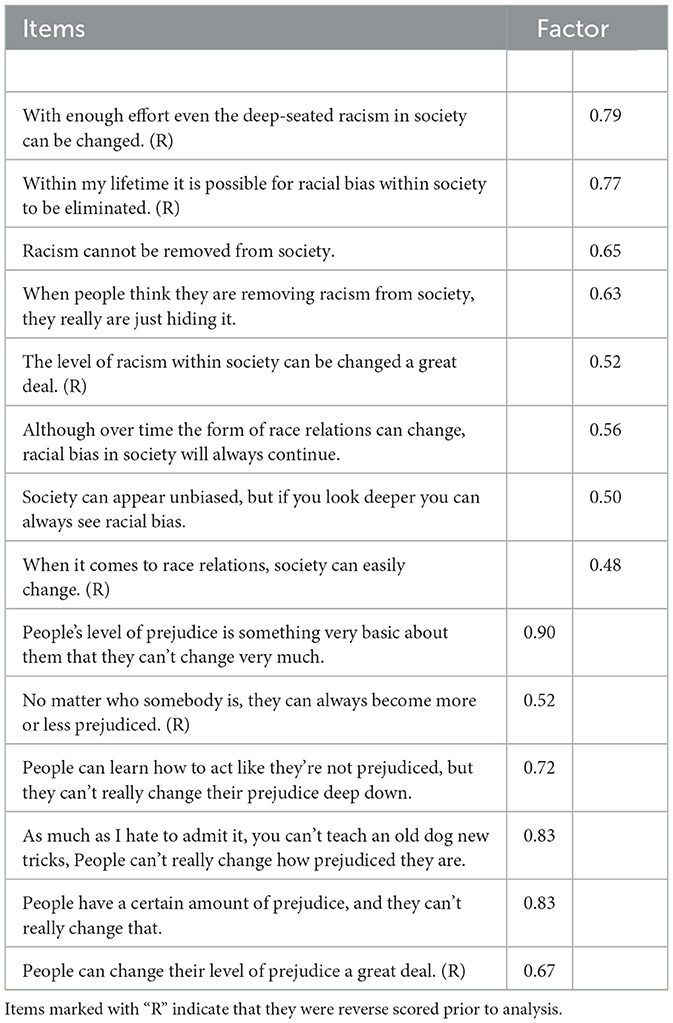

We conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on the system permanence measure using principal axis factoring with oblimin rotations. The EFA supported a single-factor solution, with all items loading strongly onto one factor (eigenvalue > 3.0). Next, we submitted the system permeance measure and the theories of individual prejudice scale (further referred to as Individual Permanence) to a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) testing whether these measures could be distinguished in a two-factor model. The two-factor model fit the data significantly better than a one-factor model (Δχ2 (1) = 577.4, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.84, RMSEA = 0.12, SRMR = 0.08), and items loaded cleanly onto their respective factors (βs ≥ 0.48 for system items; βs ≥ 0.52 for individual items). These results provide evidence of discriminant validity, supporting the distinction between beliefs about the permanence of systemic racism and beliefs about individual permanence (see Table 1).

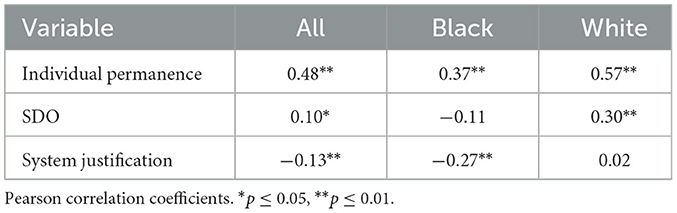

As predicted, Black participants endorsed system permanence beliefs (M = 3.01; SD = 0.98) significantly more than White participants did (M = 2.83; SD = 0.94); t(418) = −1.98, p = 0.050, d = 0.19). Also, individual and system permanence beliefs were more highly correlated for White Americans than for Black Americans (see Table 2). This aligns with our theoretical claim that lived experience with systemic racism may shape how different groups perceive the possibility of social change.

Correlational analyses revealed that system permanence beliefs were weakly positively associated with social dominance orientation (SDO; r = 0.10, p = 0.044), and negatively associated with system justification (r = −0.13, p = 0.007). However, these associations differed by race (see Table 2).

For Black participants, the more they believed systemic racism was permanent, the less they justified the system. Black participants also showed a trending negative correlation between system permanence beliefs and social dominance orientation (SDO). For White participants PSR was uncorrelated with system justification and it was related to higher SDO scores, indicating their greater preference for inequality amongst social groups. Overall, results revealed that participants' PSR beliefs were conceptually related to but distinct from other measures.

Study 2

We examined the relation between permanence of systemic racism beliefs and willingness to engage in conventional collective action. The scale development results indicated that Black Americans' system permanence beliefs were associated with significantly lower system justification. To the extent that Black Americans with high system permanence beliefs perceive this deeply rooted racism is unjustified, one might expect that they would be more motivated to engage in collective action to challenge that system. However, such a prediction overlooks that willingness to support efforts to change the system depend not just on seeing that system as unjustified but also perceiving change as possible (Van Stekelenburg and Klandermans, 2017). Because Black Americans' system permanence beliefs entail viewing system reform as implausible, we predicted such beliefs should decrease their willingness to participate in antiracist collective action despite their belief that this system is unjustified.

Method

Participants

We recruited 241 Black participants (49.8% male, 47.3% female, Mage = 35.2, SDage = 12.3) from Prolific's online platform. To be eligible to participate, Prolific workers had to report their race/ethnicity as Black/African American, from the United States, and 18 or older. A total of 16 participants were excluded from analyses for failing the reCAPTCHA question prior to the study, not completing our main measures, or not identifying as Black/African American.

Measures

Permanence of systemic racism (PSR) scale. We assessed people's beliefs in the permanence of systemic racism scale described in the scale development section. The scale includes eight items (α = 0.82), and responses were scored on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree), i.e., “Racism cannot be removed from society.” Four items were reverse coded prior to analysis so that higher scores indicate the belief that racism is more permanent in society.

Theories of individual prejudice scale. We assessed people's theories about the malleability of individual prejudice using an existing measure (Carr et al., 2012). This measure consists of five items (α = 0.88) and gauges the extent to which individuals believe that personal prejudice is malleable or permanent (i.e., “People have a certain level of prejudice and there's not much they can do to change that”). Participants responded on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree). Higher scores indicate that participants perceive individual prejudice as more permanent.

Collective action intentions. Participants reported on a 4-item, 6-point scale (1 = extremely unlikely, 6 = extremely likely) how likely they would be to support racial justice movements, such as the Black Lives Matter movement by engaging in various activities (i.e., participating in a protest, marching in the streets, etc.) (α = 0.89). Higher scores indicate greater intentions to engage in race-based collective action. The collective action scale maps most closely onto conventional activism.

Procedure

After providing their informed consent, participants completed our systemic and individual belief measures. Next, participants answered a question about their willingness to engage in collective action (CA) for racial justice. Participants answered questions about anger and importance (see Supplement for details). Finally, participants completed demographics, were debriefed, and thanked for their time.

Results

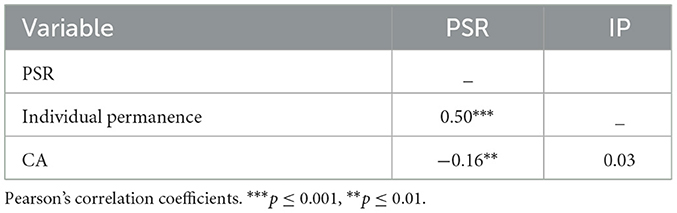

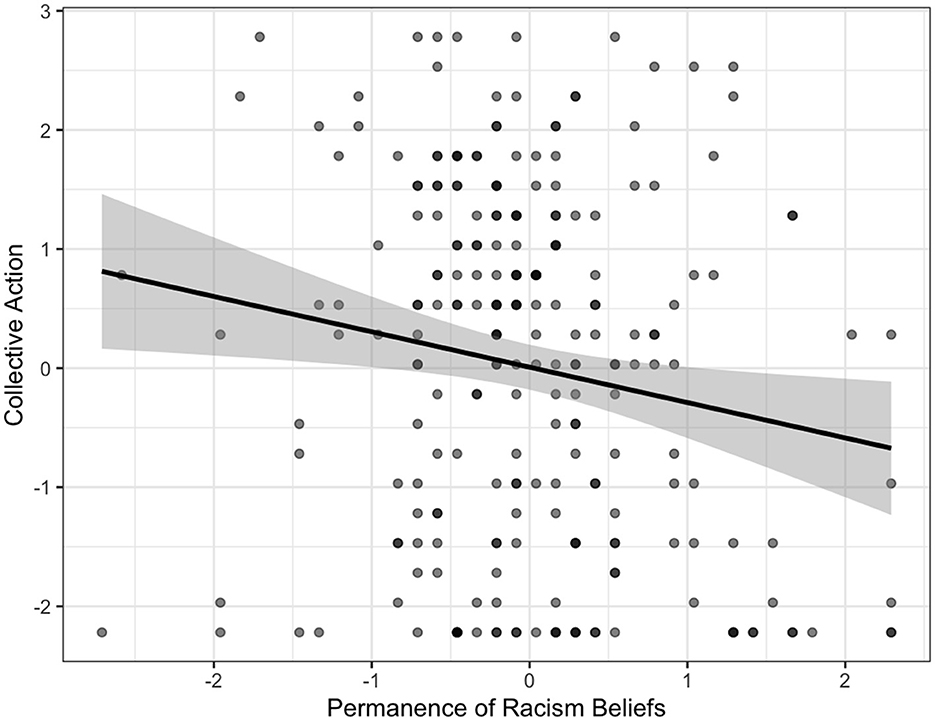

We examined the correlations between permanence beliefs and conventional collective action. As predicted, participants who believed that systemic racism is more permanent were also less likely to indicate intentions for collective action (r = −0.16, t(237) = −2.55, p = 0.012; see Figure 1). In contrast, beliefs about the permanence of individual prejudice were uncorrelated with CA intentions (r = 0.03, t(237) = 0.51, p = 0.611) (Table 3).

Figure 1. Relationship between collective action engagement and performance of racism beliefs. Variables are mean centered.

We then entered both belief types into a multiple regression predicting CA intentions. System permanence beliefs remained a significant negative predictor (b = −0.44, t(238) = −3.38, p = 0.001), while individual prejudice beliefs now emerged as a positive predictor (b = 0.32, t(238) = 2.84, p = 0.005). This shift suggests a suppressor effect: controlling for systemic beliefs appears to clarify the distinct predictive role of individual beliefs. To further probe this, we tested a System × Individual Beliefs interaction, which was significant (b = −0.25, t(238) = −3.27, p = 0.001).

Simple slopes analyses revealed that when systemic beliefs were more malleable (−1 SD), stronger belief in the permanence of individual prejudice predicted greater CA intentions (b = 0.53, t(235) = 3.73, p < 0.001). When system permanence beliefs were high, individual beliefs were unrelated to action intentions (b = 0.11, t(235) = 0.97, p = 0.33).

Discussion

This study provided initial support for our central prediction: beliefs about the permanence of systemic racism, but not beliefs about the permanence of individual prejudice, negatively predicted willingness to engage in conventional collective action. Specifically, participants who viewed systemic racism as permanent were less inclined to participate in activism aimed at reforming the system. Notably, individual prejudice beliefs were unrelated to collective action intentions in single-predictor analyses and became positively related only after controlling for systemic beliefs. This finding, though unexpected, suggests a suppressor effect, indicating that distinguishing between systemic and individual-level racism perceptions warrants further exploration. In Study 3 we examined how beliefs about the permanence of systemic racism are related to attention to real world events that are directly related to challenging systemic racism.

Study 3

In Study 3, we sought to replicate Study 2 during a period of heightened media attention on systemic racism—the Derek Chauvin trial, in which a White police officer was tried for the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man. Our goals were to assess the permanence of systemic racism (PSR) scale in a context of real-world confrontation with racist policing and replicate the relationship between PSR beliefs and social justice intentions. Firstly, we predicted that greater PSR beliefs would be associated with lesser intentions to engage in collective action, as in Study 2. Secondly, we predicted that Black Americans' attention to current events would relate to perceptions of systemic racism. Lastly, we predicted that Black Americans' attention to current events would relate to their systemic racism beliefs and thereby intentions to engage in collective action. Specifically, we surveyed three different samples at three distinct periods (pre-verdict, post-verdict, and sentencing) during the Chauvin trial

Method

Participants

Participants were 458 Black American male and female adults recruited online from Prolific. Data collection occurred in 2021 in early April (pre-verdict), early May (post-verdict), and in late June (after sentencing). At each stage of data collection, participants were excluded based on predetermined criteria. Across all three data collection points, 51 participants were excluded for failing reCAPTCHA scores or not completing the study, 13 were excluded for not identifying as Black/African American, one participant was excluded for not identifying as American, and lastly four participants were excluded for not passing attention checks. Final analyses included 389 Black participants (45.6% male, 53.3% female, Mage = 33.1, SDage = 10).

Materials

Participants completed the same PSR scale (α = 0.83) used in Study 1 and 2.

Attention to current events. To assess whether participants' attention to current events during the trial, participants reported on five current events. Participants were asked “How much have you been paying attention to the following current events” and responded from 1 (none at all) to 5 (a great deal). Events varied based on time of data collection and trending news stories at the time. At pre-verdict, participants were asked to report how much attention they paid to the following events: Derek Chauvin trial, COVID-19 pandemic, accusations of sexual misconduct against Matt Gaetz, President Biden's actions on gun control, and Georgia voting laws. Participants during the post-verdict and sentencing data collection periods were asked to respond to the following events: Derek Chauvin trial, COVID-19 pandemic, President Biden's actions, Israeli airstrikes, and policing in America. Responses to each event were compiled, such that higher scores meant more attention to current events during the trial.

Collective action intentions (CA). Participants responded to a race-based measure of collective action adapted from Tropp and Ulug (2019). Participants reported their willingness to support racial justice movements by engaging in various behaviors associated with collective action on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (always). Participants were asked, “How willing are you to support racial justice movements such as the Black Lives Matter movement by…” (α = 0.88). Behaviors included marching in the streets, attending forums, meetings, or discussion groups, and posting messages on social media.

Procedure

After providing their informed consent, participants completed the following measures in a fixed order. Participants completed the same individual prejudice and permanence of racism measures from Study 2. Participants completed additional measures relating to perceived prevalence of racism, frequency of prejudiced experiences, personal goals, and a brief attention check. Participants then reported their willingness to support anti-racist protest and how much attention they had been paying to current events. Finally, participants provided demographic information, were debriefed, and compensated.

Results

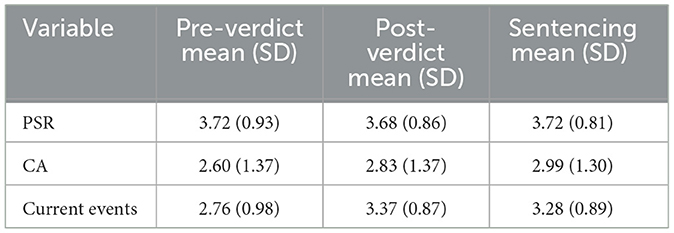

There was not meaningful variation in our variables and relationships of interest across time points (see Supplementary material). Given the smaller sample sizes N's <140 for each timepoint we also combine samples for greater statistical power. Therefore, we compiled the data, and reported results across time points (see Table 4).

Table 4. Unstandardized means and standard deviation of permanence of racism, attention to current events, and willingness to engage in collective action for all time points.

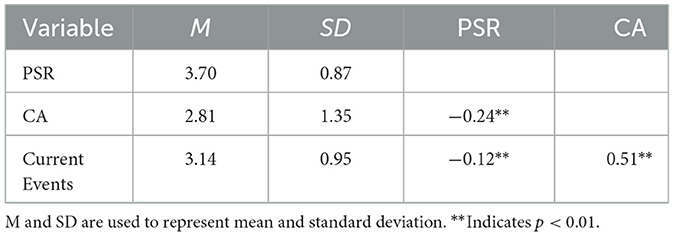

As predicted higher PSR predicted lower CA (r = −0.24, t(386) = −4.81, p < 0.001) unstandardized means and standard deviations for each of the variables and bivariate correlations between variables for our compiled samples are reported in Table 5. We found that attention to current events during the time of the Chauvin trial predicted lower PSR beliefs (r = −0.12, t(386) = −2.37, p = 0.018) and higher CA (r = 0.51, t(385) = 11.60, p < 0.001). However, we should note that attention to the Chauvin trial alone did not predict PSR beliefs (r = −0.02, t(387) = −0.038, p = 0.71). Therefore, as predicted, attention to current events and PSR beliefs are related, notably the relationship is not unique to the Chauvin trial but more general attention to current events.

Table 5. Unstandardized means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and bivariate correlations between racism permanence, current events, and willingness to engage in collective action across all time points.

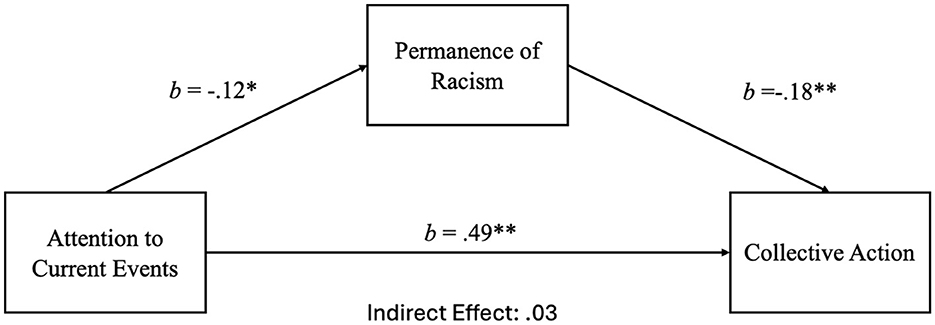

Given the link between PSR and activism intentions we aimed to test the prediction that real world issues predict perceptions of systemic racism, which in turn predict intentions for collective action engagement. We examined a simple mediation pathway. Attention to current events predicted PSR (b = −0.12, p = 0.017) and PSR predicted lower CA (b = −0.18, p < 0.001; see Figure 2). There was an indirect effect of attention to news on CA [indirect = 0.03, 95% CI (0.004, 0.066)], suggesting that PSR may mediate the relationship between the two. In support of hypotheses, PSR beliefs seem to be associated with real-world situations and are malleable to current events and perceptions of society. These updated beliefs may then be used to predict activism. However, we cannot speak to the causal relationship between these variables, as further analysis suggests that other pathways are likely (see Supplementary material).

Figure 2. Mediation pathway from attention to current events to collective action intentions via performance of racism beliefs. * <0.05, ** <0.001.

Discussion

In Study 3 we sought to validate the PSR scale for real-life application and to replicate the relationship between PSR beliefs and social justice. We found support for the use of the PSR scale to examine reactions to real-life events that relate to Black Americans' perceptions of systemic racism. We found that while paying attention to current events during the trial was associated with lower PSR beliefs, paying attention to the Derek Chauvin trial in particular was not associated with PSR. Given the design of Study 3 we cannot make clear predictions about the exact role of attention to current events. Systemic racism is pervasive and present in many aspects of the Black American experience, it would make sense that one instance of progression, such as accountability for one instance of police brutality, would not sway beliefs about systemic racism. We chose this period to examine PSR beliefs not solely for the Chauvin trial, but because there were increased conversations about systemic racism, collective action, and other events that would have encouraged Black Americans to think about systemic racism. We believed that the more exposure Black Americans had to current events such as the Chauvin trial and the other measured events, they might believe that systemic racism can be challenged and ultimately changed. It is also possible that those who believe that systemic racism is malleable are more likely to pay attention to news that may confirm those beliefs. Results supported our prediction that attention to news during a period of antiracist movement gains predicted reduced belief in the permanence of systemic racism and thereby greater willingness to participate in CA. Overall, Study 3 provides support for the use of the PSR scale in reflecting Black Americans' responses to instances of systemic racism and the relationship between PSR beliefs and social justice intentions.

Study 4

In previous studies we explored collective action intentions broadly, in Study 4 we break down different potential forms of collective action. We argue that support for these types of social justice may differ based on peoples' beliefs about the systems around them. Black Americans should most likely support conventional action when they believe that the system is capable of change as demonstrated in Studies 2 and 3. In Study 4 we explore the relationship between disruptive activism and PSR beliefs.

In Study 4 we sought to examine the mechanism by which Black Americans disengage from or support social activism and policies. We predicted that Black Americans who perceive racism as permanent would perceive lower effectiveness for actions, particular conventional actions and lesser perceived effectiveness would relate to lesser intentions to engage in such activism. We also predicted that the relationship between effectiveness and policy support would not be as strong as for action. Potentially due to the relative ease of supporting or voting for a policy compared to actively participating in collective behaviors. We also examined whether Black Americans' perceptions of systemic racism as permanent differentially predict intentions to support conventional vs. system disruptive policies.

Method

Participants

Analyses were conducted with 170 Black participants (40% male, 60% female, Mage = 41.37, SDage = 13.27) from Prolific's online platform. To be eligible to participate, Prolific workers had to report their race/ethnicity as Black/African American, be from the United States and be 18 or older. A total of 40 participants were excluded from analyses for failing the reCAPTCHA question prior to the study, being flagged as duplicate data by Qualtrics, or not identifying as Black/African American.

Measures

Permanence of systemic racism beliefs (α= 0.83) was measured as in all studies previously.

Social justice actions. Two items were used to assess conventional action (α = 0.82) and two items for disruptive action (α = 0.74). Participants were asked on a scale 1(extremely unlikely) to 7(extremely likely)” How likely would you be to engage in the following actions?” The conventional action items included, “Post/repost messages on social media to call attention to police brutality” and “Attend a march to advocate for lives unjustly lost at the hands of the police.” The disruptive action items included, “Participate in a rally at police headquarters to decrease funding for police” and “Disrupt court proceedings for people of color who may be unjustly accused of a crime by a biased police officer.”

Social justice policies. Two items were used to assess conventional policy support (α = 0.73) and two items for system disruptive policy support (α = 0.85). Participants were asked on a scale 1(extremely unlikely) to 7(extremely likely) “How likely would you be to support the following policies?” Conventional policies included, “Increase funding for police officer training on bias in the field” and “Increase funding to internal affairs to investigate bias and corruption within police units.” Disruptive policies included, “Abolish the police department and reallocate funding to communities” and “Eliminate use of guns by police and provide them with nonlethal weapons only.” For each of these actions and policies above we measured both intentions to engage and perceived effectiveness.

Collective action intentions. Participants were asked to indicate the likelihood of engagement of support for each set of social justice actions and policies below (0.85≥α′s≥0.73; see Supplement). Higher scores indicate greater intentions to support.

Effectiveness. Participants were asked “How effective do you think these actions/policies would be in reducing racism in society?” for each set of social justice intentions (0.83≥α′s≥0.63). Higher scores indicate greater perceived effectiveness.

Procedure

After providing their informed consent, participants completed the PSR scale. Next, participants answered a question about their intentions to engage and the effectiveness of collective actions and social justice policies. Finally, participants completed demographics, were debriefed, and thanked for their time.

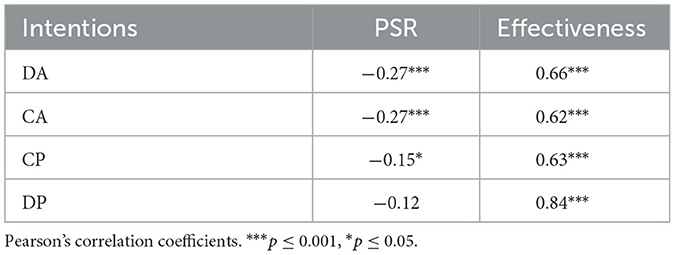

Results

PSR beliefs were negatively correlated with all forms of actions and policies (see Table 6). The greater the belief that systemic racism is permanent, the less likely participants were to indicate intentions for activism. The correlations between PSR and conventional action (CA) and disruptive action (DA) were stronger than for the policy items, reflecting the relationship found in studies 1 and 2 demonstrating that beliefs and actions are linked. There is a weaker relationship between PSR beliefs and policy support. The correlation with conventional policy (CP) was small (p = 0.053) and the correlation with disruptive policy (DP) was non-significant (p = 0.117). As predicted, PSR does seem to differentially predict policies vs. actions. The slightly attenuated relationship between PSR and policy support may reflect lower effort requirements or differing motivational processes when supporting policy vs. engaging in direct action. Further explanations should be explored in future research.

Participants perceived the greatest effectiveness for CP (M = 3.54, SD = 1.10) and CA (M = 3.34, SD = 1.21) followed by DA (M = 2.64, SD = 1.15) and DP (M = 2.46, SD = 1.31). We tested the correlation between effectiveness of the action or policy and PSR beliefs. For all types of social justice intentions, greater PSR was correlated with lesser perceptions of effectiveness (−0.39 ≤ r's ≤ −0.20).

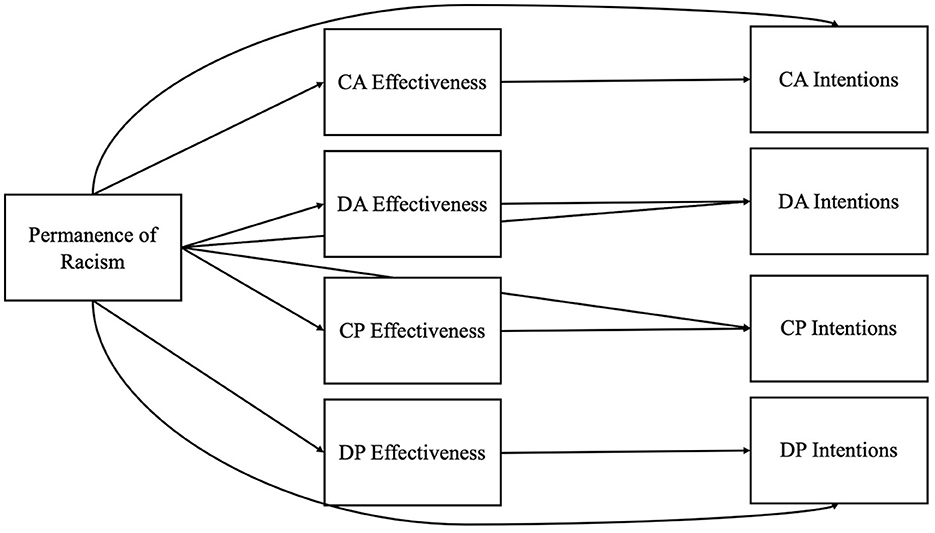

Given the relationship between variables, we propose one possible explanation for the relationship; when people believe that systemic racism is permanent, they are less likely to believe that activism will be effective, and therefore less likely to engage in action. Therefore, we hypothesized that perceived effectiveness would mediate the relationship between PSR beliefs and social justice intentions, particularly for actions (see Figure 3). To test this, we conducted a parallel mediation SEM using the Lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012) where PSR predicts each type of effectiveness, which then predicts each type of intention.

Figure 3. Path model for perceived effectiveness mediating the relationship between PSR and social justice intentions.

We examine the pathway for each social justice action type to test our prediction that social justice effectiveness will mediate the relationship between PSR and intentions for conventional activism and disruptive activism, but not for conventional or disruptive policies.

Conventional action mediation

While the overall model tested every mediator–outcome pairing at once, the following focuses on each single path, starting with whether PSR beliefs predict CA intentions indirectly through perceived effectiveness. Results indicated a significant path from PSR to efficacy, b = −0.52, p < 0.001, and a significant path from efficacy to CA intentions, b = 0.99, p < 0.001. The indirect effect was significant, indirect = −0.51, 95% CI [−0.77, −0.28], p < 0.001. There was no direct effect of PSR on intentions when accounting for effectiveness, b = −0.10, p = 0.546. The total effect was significant (total = −0.60, p < 0.001). Therefore, as predicted, perceived effectiveness mediates the relationship between PSR beliefs and CA intentions.

Disruptive action mediation

We next examined intentions to engage in disruptive activism (DA). As predicted, effectiveness again acted as the mediator. PSR significantly predicted effectiveness, b = −0.47, p < 0.001, and effectiveness significantly predicted DA intentions, b = 0.98, p < 0.001. The indirect effect was significant, indirect = −0.45, 95% CI [−0.67, −0.27], p < 0.001. The direct effect was not significant, b = −0.10, p = 0.46, and the total effect (total = −0.56, p < 0.001) was significant, again indicating mediation.

Conventional policy mediation

We next examined intentions to support conventional policy via effectiveness. PSR was positively associated with effectiveness, b = −0.25, p = 0.031, and effectiveness predicted conventional policy intentions, b = 0.99, p < 0.001. The indirect effect was significant, indirect = −0.25, 95% CI [−0.52, −0.02], p = 0.048. Again, no direct effect remained, b = −0.03, p = 0.84, but for CP there was no overall total effect (total = −0.28, p = 0.112). Counter to our predictions, effectiveness did mediate the relationship for conventional policy.

Disruptive policy mediation

Finally, for the disruptive policy outcome, effectiveness again served as the mediator. PSR significantly predicted effectiveness, b = −0.29, p = 0.01, and effectiveness significantly predicted disruptive policy intentions, b = 1.29, p < 0.001. The indirect effect was significant, indirect = −0.38, 95% CI [−0.66, −0.09], p = 0.01, while the direct effect was not significant, b = −0.10, p = 0.282. The total effect was not significant (total = −0.27, p ≤ 0.132). Therefore, contrary to predictions, effectiveness mediated the relationship between PSR and intentions for both activist intentions and policy support.

Discussion

In Study 4 we sought to examine the mechanism by which Black beliefs influence participation in social justice actions. Our hypotheses were partially Americans' PSR supported. We found the predicted replication of the relationship between PSR and conventional actions. Interestingly, disruptive actions showed the same pattern of relationship. We predicted that perceived effectiveness would mediate the relationship between PSR beliefs and collective action intentions but not for policy support. However, effectiveness mediated the relationship between PSR and intentions for all antiracism measures. To the extent that Black Americans believe systemic racism is more permanent, they are more likely to believe antiracist activism and policies are ineffective in producing change, and this perceived ineffectiveness relates to lesser intentions to engage. We do note that other explanations for the relationship between PSR and activism exist. It is possible that people examine the activism they have engaged in or not and justify inaction or ineffective action by perceiving the system as unchangeable.

General discussion

We developed and validated a scale measuring perceived permanence of systemic racism, showing it relates to—but differs from—individual-level permanence beliefs and varies by race. Results showed that compared to White Americans Black Americans perceive systemic racism as more permanent and perceive a sharper distinction between permanence of racism at the individual and systemic levels. Also, perceived systemic permanence showed different associations with systemic justification and social dominance motivation for Black (vs. White) Americans. Overall, these patterns suggest that Black Americans' lived experiences confronting racism in their own lives and through generations in their families give them a different understanding of systemic racism compared to White Americans.

Then, in three correlational studies, we establish that to the extent that Black Americans believe racism is permanent, they indicate lower intentions to engage in collective activism aimed at reforming current systems. In Study 3 we find that paying attention to current events during a period when antiracist movements were making gains was associated with perceiving systemic racism as less permanent and thereby greater intentions of joining antiracist activism. Consistent across all studies is the link between PSR and collective action; Black Americans who perceive systemic racism to be more permanent, also tend to indicate lesser intentions for collective action. In Study 4 we explored various types of activism. We found that greater PSR was related to lesser intentions for disruptive actions. We were curious if this relationship would be attenuated, or potentially even flipped. It is possible that Black Americans who perceive systemic racism as permanent may be more supportive of disruptive collective actions that seek to tear down those biased systems and replace them with a truly egalitarian system. This may still be true given some conditions or situations. Future research should explore this variable. In Study 4 we explored this pathway between PSR and activism by suggesting that PSR beliefs could predict perceived effectiveness of social justice actions, which in turn would relate to intentions to engage. Results indicated that perceived effectiveness in achieving social justice change mediates the link between permanence of systemic racism beliefs and intentions to participate in action and support antiracism policies.

Limitations

The present measure of permanence of systemic racism beliefs and topic of research has focused on racism and Black Americans' perceptions. We would predict comparable results across other groups and facing systemic prejudices, but the present research does not test these predictions. Future research should examine racism permanence beliefs with other samples and types of prejudice.

An additional limitation was the sample composition in Study 3. Ideally, it would have been much more informative to conduct a panel study and examine changes as the trial progressed. Due to time constraints, we were not able to coordinate recruitment efforts to do so. Future research would benefit from a more controlled examination of the impact of real-world events on PSR beliefs.

Another key limitation was the operationalization of social justice activism. These measures were exploratory and as such have room for further psychometric development and validation. To determine the distinction between conventional vs. disruptive forms of actions and policies further study is necessary.

We also missed the opportunity to ask participants about whether social justice was a major concern for them, whether engaging in any type of social justice action was a goal of theirs, or whether they believe systemic racism is a pressing social issue. We assumed that with a Black sample, most of the participants would care about social justice for Black people and police reform and believe that systemic racism exists and is a major concern for their group. However, there likely is important variability here. These variations could have impacted our findings and warrant future consideration.

Importantly, there are many alternative explanations to the results presented above. Further research should explore these alternative routes and potential causality. Across all studies, it is clear that there is a relationship between PSR and activism. It is less clear and most likely the case that the causal relationship varies among people and situations. Some people may base their beliefs about the system based on real world events and then choose how to engage in activism. It is also possible that people pay attention to current events in response to actions they have already participated in based on firmly held beliefs. Black Americans who perceive activism as ineffective would therefore perceive racism as permanent and be less likely to engage in activism. The interconnected and complex relationship between these variables warrants further explorations.

Theoretical contribution

Systemic racism is an important but understudied topic in psychology. The present research is part of a growing literature (Rucker and Richeson, 2021b; Banaji et al., 2021; Sommers and Norton, 2006) in social psychology that explores how people perceive racism at the system level. The current studies also integrate ideas from Critical Race Theory (CRT) into social psychology by examining variation in laypeople's beliefs in CRT's permanence of racism thesis (Bell, 1992; Wilderson III, 2020). We documented meaningful variation in this belief, and these variations impact people's motivations and actions.

Our research also makes a valuable contribution to the social movement literature. Previous research has highlighted the role of efficacy beliefs in determining intentions to participate in social activism (Van Stekelenburg and Klandermans, 2017; van Zomeren et al., 2008). Our research builds on this by showing that theories about the malleability of sociopolitical structures—in this case, malleability of systemic racism—may be a key source of effectiveness perceptions. Future research can build on this to examine whether lay theories about the malleability of other components of the sociopolitical system influence change effectiveness perceptions and activist intentions for other social movements.

We extend research on the lay theories of changeability of social phenomena to the important domain of systemic racism (Carr et al., 2012). It is important to understand how people perceive the malleability of systemic racism to understand how they might interact (or disengage) with the world around them, similar to previous research that has documented motivational impacts of other lay theories of change (Plaks et al., 2009).

Practical consequences

The findings that PSR beliefs are associated with reduced motivation to participate in collective action among Black Americans might seem to suggest the need for interventions to challenge individuals' permanence beliefs in order to reduce these negative outcomes, similar to interventions that challenge laypeople's entity theories about abilities and traits. However, we believe that the idea that permanence of systemic racism beliefs are problematic and need to be “fixed” is deeply misguided. Rather than trying to “fix” Black Americans' beliefs that systemic racism is permanent we should aim to listen carefully in order to understand what these views tell us about their intergenerational experiences of struggling to cope with this system's racist institutions and practices. Then, rather than intervening at the individual level to change Black Americans' perceptions of the system we might instead ask what interventions might be needed at the system level to generate more authentic hope that systemic racism can eventually be eliminated.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ohio State University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because participants provided online consent.

Author contributions

VI: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NC-R: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MW: Writing – original draft, Data curation. RE: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. SS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

This study was partially funded by Society for Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI) Grant-in aid, $1,000 Fall 2023 recipient.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2025.1537489/full#supplementary-material

References

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E., and Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: critique and reformulation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 87:49. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.87.1.49

Banaji, M. R., Fiske, S. T., and Massey, D. S. (2021). Systemic racism: individuals andinteractions, institutions and society. Cognitive Res. 6, 1–21. doi: 10.1186/s41235-021-00349-3

Bell, D. A. (1992). Faces at the Bottom of the Well : The Permanence of Racism. New York: BasicBooks.

Bonam, C. M., Nair Das, V., Coleman, B. R., and Salter, P. (2019). Ignoring history, denying racism: mounting evidence for the Marley hypothesis and epistemologies of ignorance. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 10, 257–265. doi: 10.1177/1948550617751583

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2021). What makes systemic racism systemic? Sociol. Inq. 91, 513–533. doi: 10.1111/soin.12420

Bullard, R. D., Mohai, P., Saha, R., and Wright, B. (2007). “Dismantling toxic racism,” in Special Environmental Justice Issues of the NAACP's The Crisis Magazine 114.

Carr, P. B., Dweck, C. S., and Pauker, K. (2012). “Prejudiced” behavior without prejudice? Beliefs about the malleability of prejudice affect interracial interactions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 103:452. doi: 10.1037/a0028849

Chiu, C. Y., Hong, Y. Y., and Dweck, C. S. (1997). Lay dispositionism and implicit theories of personality. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 73:19. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.19

Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Pratto, F., Henkel, K. E., et al. (2015). The nature of social dominance orientation: theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO7 scale. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 109:1003. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000033

Ivy, V. (2024). Social justice intentions and belief in the permanence of systemic racism. (Doctoral Dissertation). The Ohio State University, Columbus, United States.

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., Peach, J. M., Laurin, K., Friesen, J., Zanna, M. P., et al. (2009). Inequality, discrimination, and the power of the status quo: Direct evidence for a motivation to see the way things are as the way they should be. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 97, 421–434. doi: 10.1037/a0015997

Kay, A. C., and Jost, J. T. (2003). Complementary justice: effects of “poor but happy” and “poor but honest” stereotype exemplars on system justification and implicit activation of the justice motive. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 85823. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.823

Laurin, K., Gaucher, D., and Kay, A. (2013). Stability and the justification of social inequality. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 43, 246–254. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1949

Murphy, M. C., Kroeper, K. M., and Ozier, E. M. (2018). Prejudiced places: how contexts shape inequality and how policy can change them. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 5, 66–74. doi: 10.1177/2372732217748671

Nielsen, K. (1971). On the choice between reform and revolution. Inquiry 14, 271–295. doi: 10.1080/00201747108601635

Paluck, E. L., Porat, R., Clark, C. S., and Green, D. P. (2021). Prejudice reduction: progress and challenges. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 72, 533–560. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-071620-030619

Payne, B. K., and Hannay, J. W. (2021). Implicit bias reflects systemic racism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 25, 927–936. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2021.08.001

Plaks, J. E., Levy, S. R., and Dweck, C. S. (2009). Lay theories of personality: cornerstones of meaning in social cognition. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 3, 1069–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00222.x

Rattan, A., and Dweck, C. S. (2010). Who confronts prejudice? The role of implicit theories in the motivation to confront prejudice. Psychol. Sci. 21, 952–959. doi: 10.1177/0956797610374740

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rucker, J. M., and Richeson, J. A. (2021a). Toward an understanding of structural racism: implications for criminal justice. Science 374, 286–290. doi: 10.1126/science.abj7779

Rucker, J. M., and Richeson, J. A. (2021b). “Beliefs about the interpersonal vs. structural nature of racism and responses to racial inequality,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Discrimination, Prejudice and Stereotyping, eds. C. Tileagă, M. Augoustinos, and K. Durrheim (Routledge), 13–25.

Salter, P. S., Adams, G., and Perez, M. J. (2018). Racism in the structure of everyday worlds: a cultural-psychological perspective. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 27, 150–155. doi: 10.1177/0963721417724239

Sommers, S. R., and Norton, M. I. (2006). Lay theories about white racists: what constitutes racism (and what doesn't). Group Processes Intergroup Relat. 9, 117–138. doi: 10.1177/1368430206059881

Thomas, E. F., and McGarty, C. (2009). The role of efficacy and moral outrage norms in creating the potential for collective action: an integrated social identity model. J. Soc. Issues 65, 727–748. doi: 10.1348/014466608X313774

Tropp, L. R., and Ulug, Ö. M. (2019). Are white women showing up for racial justice? Intergroup contact, closeness to people targeted by prejudice, and collective action. Psychol. Women Quart. 43, 335–347. doi: 10.1177/0361684319840269

Van Stekelenburg, J., and Klandermans, B. (2017). “Individuals in movements: a social psychology of contention,” in Handbook of Social Movements across Disciplines, eds. C. Roggeband and B. Klandermans (Springer, Cham), 103–139.

van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., and Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: a quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 134, 504–535. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

Wilmot, M. (2019). A “Bad Apple” or a “Spoiled Barrel”?: Observing Overt Racism Predicts Diverging Perceptions of Racism and Race Relations in America. University of Waterloo.

Keywords: systemic racism, collective action, activism, social justice, beliefs

Citation: Ivy V, Corley-Rigoni N, Wilmot M, Eibach RP and Spencer S (2025) Belief in the permanence of systemic racism as a barrier to antiracist activism. Front. Soc. Psychol. 3:1537489. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2025.1537489

Received: 01 December 2024; Accepted: 24 June 2025;

Published: 16 July 2025.

Edited by:

Kristin Laurin, University of British Columbia, CanadaReviewed by:

Peter Ditto, University of California, Irvine, United StatesDiana Betz, Loyola University Maryland, United States

Copyright © 2025 Ivy, Corley-Rigoni, Wilmot, Eibach and Spencer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vanessa Ivy, dmFuZXNzYWxpdnkxNUBnbWFpbC5jb20=; Natarshia Corley-Rigoni, Y29ybGV5LXJpZ29uaS4xQGJ1Y2tleWVtYWlsLm9zdS5lZHU=

Vanessa Ivy

Vanessa Ivy Natarshia Corley-Rigoni

Natarshia Corley-Rigoni Matthew Wilmot2

Matthew Wilmot2 Richard P. Eibach

Richard P. Eibach Steven Spencer

Steven Spencer