- Sustainable Europe Research Institute, Köln, Germany

The debate about care has intensified in the COVID-19 crisis. A consensus appears to be emerging that care work—mostly provided by women—is not only essential to our societies, but also undervalued, reputationally as well as—for the paid work—regarding its remuneration. As care is essential for the cohesion of societies, there is an urgent need to improve the situation. However, care comes in too many forms for general recommendations for improving the situation to be effective. Its majority in terms of working hours is unpaid, but the paid part of it in health, caring or education, is indispensable for any society built upon a division of labor. Finally, not every activity is work, and not every work is care—thus leisure activities are not necessarily care work. Care can be motivated by a plethora of reasons, and take a diversity of forms. To allow for effective suggestions for improvement to be formulated, we deem it necessary to more systematically distinguish different classes of care (each class of course being an ideal type including a wide range of activities). We suggest doing so by first using the “potential third party” criterion to distinguish work and non-work activities, secondly classify work according to the beneficiaries (which is closely linked to but not the same as organizational characteristics), and thirdly characterize the specific role of care work in these categories. The beneficiaries also reflect the motivation held by agents why care work is undertaken, although rarely any motivation comes in isolation. Starting from the proximate causes, the first class of care is caring for oneself, be it in terms of health care, hygiene, or the self-production of consumer goods, both short and long lived. The second class we suggest is caring for the family (native and chosen family including friends). It again includes caring for their health, but also their household (either the common one, or the one the caretaker is managing for the care receiver). It often includes nursing the elderly, disabled or young children, but can also be a kind of neighborhood support, from joint gardening to mutual help in building or renovating a flat or house. Extending the reach of care even wider, we come to care for the public good, with the community from village or city district to higher levels being the beneficiaries. This includes the volunteers working with environment, development, feminist, trade unions, food banks or belief organizations. Finally, there is a whole range of professional care activities, with the possibility to take over any of the previously mentioned activities if there is a financial benefit to be expected, or one is offered by (government) subsidies. We observe a permanent process of substituting professional, exchange value oriented care work for voluntary, use value based care, and vice versa. This dynamic, in combination with the ongoing changes of technology, social security systems and work organization in the remunerated work sets the framework conditions which will determine the future of care, commercial and societal. However, such trends are no destiny; they can be shaped by political interventions. Whether or not a professional or voluntary approach is preferable, depends on the assessment criteria applied which in turn represent political, ethical and cultural preferences.

Care, Work and Care Work

Care work is a social practice emerging or generated under specific circumstances and in relation to something—the self, a person or group of persons, the social or natural environment (Shove et al., 2012). It includes a recognition of mutual dependency, amongst humans as well as in the human-nature relationship and constitutes a mutual responsibility (Brettin, 2021). Care work encompasses a broad spectrum of activities contributing to human well-being and quality of life—improving one's own living conditions, the well-being of one's own (chosen) family or caring for the local, regional, national or international community. A “chosen family” consists of friends, relatives and acquaintances who have established intensive relationships of trust and care among themselves. The traditional family is often a subgroup of the chosen family. Care work can be a profession that is practiced for money and/or with dedication (“vocation”)1, which can be observed especially in times when the health system is overburdened as in the Corona pandemic—and which probably in many cases prevented the collapse of the system.

Most forms of care work or care (the terms are used synonymously here) require physical work, but also mental activities such as organizing the smooth daily life of the chosen family and the cohabitation of its members (Jürgens and Reinecke, 1998; Emma, 2017). Nevertheless, many types of care are often not recognized as work, but are classified as a voluntary activity, leisure activity or hobby. This classification also dominates in economics, for which work is necessarily associated with “work suffering,” which is rewarded by compensation payments (wages, salaries). Those who do not demand compensation have not suffered and therefore have not worked, according to the logic of neoclassical economists—unpaid work, including care work outside the formal economy, is therefore not work but pleasure.

Everyone who has done care work knows that this assessment is wrong. This has also been proven by social science studies showing that care is not a pleasure but mostly the fulfillment of social, informally institutionalized duties that are mainly imposed on women. In these studies, care workers documented a variety of negative feelings due to physical and mental stress in the time diaries they kept as part of the research (Scherhorn, 2000). However, such feelings were perceived as not socially appropriate and were quickly repressed, so that retrospective descriptions did not necessarily correspond to the immediate feelings recorded in the diaries. Positive feelings developed only after, not during, care work, caused by the “feeling of having done the right thing, even if it was not always easy” and without reflection on the social norm that was thereby followed and reproduced.

The extent to which time outside paid work is enjoyed as leisure and activity or spent in other forms of work, especially care work, is thus not primarily a question of personal preferences. Rather, it is decisively shaped by values, norms, social situation, gender role attributions and the available social-ecological infrastructures shaping social practices and behavioral options (Spangenberg and Lorek, 2019; Großer et al., 2020). For all these reasons, we consider care work as a socially necessary component of the work members of a society do to maintain the functioning of that very society.

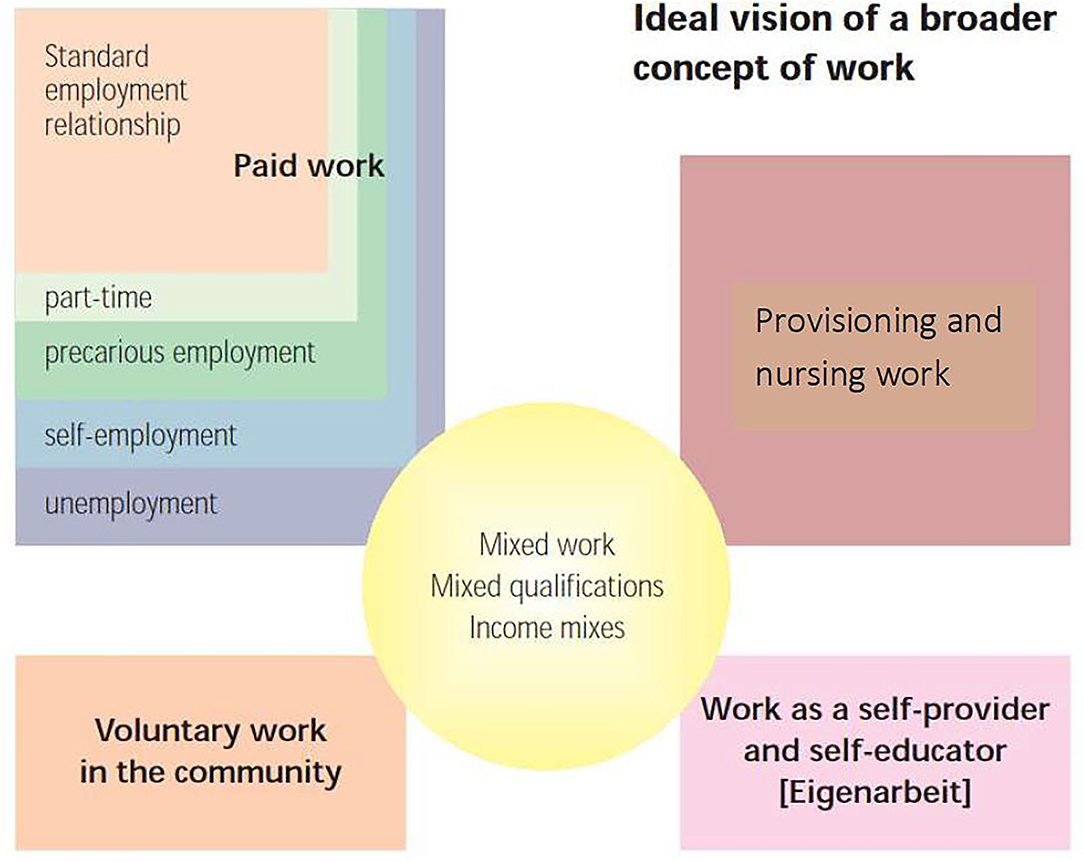

If care work is understood as a key part of socially necessary work in the sense outlined, the structure of the whole work provided in a society must be considered first, in order to understand the significance of care work, an aspect so far underemphasised in the literature. We hold that a new, systemic perspective on the different forms of work and its organization is needed to address the crisis of care, with work defined using the “potential third party criterion”, see Box 1. Therefore, in the following we first describe the development of the total of work before looking at the role of care work in the individual segments and introduce the concept of ‘mixed work' as one option, not yet established in the English language literature, how to reconcile different dimensions of societally useful work, with an emphasis on care.

Box 1. What is work?

We distinguish work from activities in that work could in principle also be performed by third parties for payment of whatever amount. This criterion is derived from the fact that in a capitalist market economy based on the division of labor, the recognition of social benefit—which is undisputed in the area of care—manifests itself through a potential willingness to pay.

The Development of Work and Care Work

The gendered division of labor emerged in the eighteenth century with the growth of the bourgeois middle class and its emerging specific family structure (beforehand, few families could afford a situation where not all household members were contributing to the household income). While in the eighteenth century bourgeois family the “lady of the house” was a leadership role, commanding multiple staff members, the decreasing middle class income in the nineteenth century enforced the internalization of formerly externalized work, constituting the role of the housewife as unpaid care worker. With industrialization, this family model spread far beyond its social class origin and became dominant, surviving even the erosion of its group of origin, and cumulating in the hegemonic model of the bread provider core family which emerged in the aftermath of WW II (Ruffles, 2021).

As a result, throughout society, a separation of the male and female worlds of life and work was established. They were divided into the public sphere of the labor economy, defined as professionally qualified male achievement, and the private sphere of the care economy, characterized as emotionally qualified maternal care. This division forms the basis of the distinction made in economics between “productive” and “unproductive” labor and still influences our thinking today. Care work, considered as unproductive, is undervalued and professionally underpaid, with few, mostly male exemptions (star cooks, chief physicians, etc.). But while the two spheres appear rather prevalent, only updated due to technical and economic developments, today sex and gender do not necessarily always coincide—women often make a career following male patterns and behavioral strategies. Still a man caring for the household risks stigmatizing (Zykunov, 2022).

This idea has only ever described an idealized, not a real “normal state.” In today's society, however, it must be recognized as outdated in several ways. On the one hand, the increasing propensity of women to take on paid work is gradually causing the basic prerequisite of the model, unpaid reproductive work, to become scarce. Secondly, age stratification, lifestyles, family structures, forms of cooperation and communication are changing and being replaced by other forms of living and relationship networks in which care work must be organized differently (Spitzner, 1999). In particular among the younger generations, maintaining the web of relations has become unthinkable without communication technologies, a hybridization transforming a formerly social relation into a socio-technical one with consequences not yet fully recognized. At the same time, new mixed forms of work are becoming established, complementing paid work in ways specific to inclinations, situations and phases of life. Thus, a welfare pluralism is emerging in which individual wellbeing as well as the functioning of the community depend not only on paid labor in the formal sector, but also on unpaid work in the informal sector—and on the quality of social security systems. Care work is taking place in both areas. For example, family provisioning, nursing, education, voluntary work and do-it-yourself are welfare-creating care work as much as paid work is. Nevertheless, the gendered allocation of forms of work is still often reproduced: in positions of social power and responsibility, women are still underrepresented—in both the paid and the unpaid sectors.

Between these two areas, a continuous substitution takes place, driven by new societal developments. As a result, the provisioning of a certain service can shift from one to the other work category, in the process changing the time budgets and the forms and levels of remuneration, but not the standard of living measured as service availability. Economic growth figures do not capture such substitution processes between value added from labor and non-labor2. The transformation from an industrial to a service economy (even in Germany more than ¾ of all workers are now employed in the service sector) and the changes within the sectors have led to certain activities of the formal economy being outsourced to the informal care economy, and vice versa. In the distribution of goods, for example, paid work has declined significantly over decades. Commercial distribution from wholesale to retail has been individualized by consumers collecting goods in “greenfield” markets, and retail distribution work has increasingly been replaced by self-service in supermarkets. Recently, there has again been a shift back to the formal economy. Triggered by online commerce and the willingness to pay for the immediate fulfillment of all wants at any time, new, and to a large extent precarious, employment relationships are increasingly emerging in delivery services, causing particular traffic problems within urban areas (Morganti et al., 2014). In the banking and travel sector, work that had long been in the paid sector has become self-providing through internet portals, e.g., through online banking and online bookings for trains and flights.

Conversely, increasing professionalization (e.g., in nursing and education by replacing domestic provisioning or private tutoring by care professionals) generates an increase in GNP—statistically, but not in real living standards of those enjoying the services: the rather unchanged provisioning service is merely commercialized. However, on the—now (miserably) paid—care giver side, policies to reduce the burden of women's unpaid care and domestic work through the state-supported marketization have been shown to widen the income gap between women who can purchase these services and those who cannot by creating a vulnerable group of under-paid care and domestic workers, often migrants from the Global South (Yamane, 2021).

This outsourcing of unprofitable services from the formal economy of paid work is associated with a decline in employment, which is countered by a commercialization of formerly unpaid care and other unpaid work (professional nursing for the elderly, fast-food production). A quantitative assessment of the shifts is hardly possible because unpaid care work is not statistically recorded as such. The GDP is of little help in this case because it distinguishes numerous sectors and groups of goods, but aggregates services summarily in one position, and mostly ignores the unpaid care work. Hence these important differentiations are not visible: the GDP is stuck in the industrial society.

At the same time, paid work is also the basis for individual engagement in the informal sector; since more than 30 years now it is known—shown by sociological surveys—that it is mainly those who are most stably anchored in the formal economy who are informally active and engaged in voluntary work: for the unemployed, self-employment is not an alternative (Mückenberger, 1990).

What (Care) Work? cui bono?

For further systematization, we propose a concept of work (and thus also of care work) that differentiates according to the cui bono criterion of which persons or groups benefit from the work performed (Brandl, Hildebrandt, 2002; Spangenberg, 2003). We distinguish between: work as a self-provider, provisioning work for a “family of choice” of friends, relatives and acquaintances with the traditional family often as a subgroup, community work, which includes all activities for (organized) third parties with whom there is no direct relationship, such as citizens' initiatives, environmental and welfare associations, churches and trade unions, and finally paid work.

Work as a Self-Provider

Such work means being productively active on one's own behalf and for one's own benefit—manually, socially or culturally. Work is linked to self-formulated needs and their use value. It leads to reduced monetary expenditure. Examples are not only do-it-yourself work, handicraft labor, and—more recently—maker spaces, but also gardening and self-service—which of these activities can or must be counted as care work depends on the concrete criteria chosen for what is societally useful.

In addition to the material benefits, there are also psychological benefits from work as a self-provider. The acquisition of skills associated with it gives a sense of independence and self-esteem (Wolf and McQuitty, 2011). Thus, it offers meaningful psychologically, socially and economically enriching work opportunities during non-working time, which improves one's life situation and offers a productive rather than consumptive use of free time. It offers options for people, in particular young adults, who want to become creative or do something themselves, or who choose self-production instead of buying goods for cost reasons (Collier and Wayment, 2018). It also includes self-education as opposed to learning in institutional, professional contexts. An appropriate infrastructure, means of production and knowledge of the “how” of production or repair are prerequisites that are available partly privately (“do it yourself”), partly in neighborhood help or in institutions such as repair cafés. If in such processes things are made or repaired for the (chosen) family or other members of a social group, then self-provisioning work and reproductive work overlap and the character as care work becomes even more obvious. However, despite these benefits, Becker (1998) has argued that it could be both, a contribution to an environmentally benign economy, but also a patriarchist trap for women, depending on the social attribution of tasks and duties in self-providing work. Environmentally, self-made goods tend to be more resource consuming than goods from efficient industrial production, but they tend to be used longer due to their emotion-based high regard; the overall balance is unclear.

Provisioning Work in and for the Chosen Family

Provisioning work refers to the part of socially important work which is “associated with the active, engaged, everyday, long-term oriented, (relationally) contextualized, nursing and provisioning care of people in physical, psychological and mental terms” (Spitzner, 1997). It is a central component of care work that is expected to increase in the future, especially where public services are already inadequate or at risk to become so following austerity programmes in the wake of the Corona financial crisis. Such provisioning work is work for the chosen family. It includes care for a traditional family (which is however defined in very different ways in the culturally diverse urban settings where the majority of humans live now), and distinguished from a family based on kinship by the voluntary character of choosing its members—knowing that the freedom of choice ends once a decision is taken and mutual obligations are established.

It is functional for the persons (e.g., partner, child, loved ones) constituting the family, but also for third parties (e.g., employer, school). One of its core functions (although usually not deliberate aim or motivation) is reproducing labor power. Examples are psychosocial caring, teaching, cooking, nursing, shopping—in other words, work that in the pandemic was to a considerable extent shifted back into the household from the commercialized and professionalized areas of society (Power, 2020). What lasting consequences the temporarily externally enforced (and much lamented) retraditionalisation of gender-specific role attribution will have is not yet foreseeable.

The idealization of the self-determined character of provisioning work found in the literature and in some social discourses is unrealistic, if not cynical. Rather, they are duties imposed on individuals according to social norms, which are often perceived as burdensome and unpleasant in their performance—regardless of the ex-post perceived satisfaction of having done “the right thing.” However, the acceptability is changing: Koo (2018) found a pervasive loss of meaningfulness in doing “housework” (the traditional form of provisioning work as discussed here) in the younger generation, even revealing harmful effects of doing housework on achieving an individuated self, separated from others and embedded into society. That care work in the sector apostrophised as “informal” is anything but free has been illustrated by the experiences with housekeeping, care work and home schooling in the Corona pandemic.

Finally, it should be mentioned that provisioning work also includes disposal, i.e., collecting, sorting and transporting waste for recycling; this unpaid disposal work is also currently performed predominantly by women. It can be surmised that the widespread implementation of the circular economy as a central goal of the European Green Deal presupposes a significant increase in such work, a further stepping up of the “feminisation of environmental responsibility” (Wichterich, 1992; Schultz, 1993).

Community Work

Community work includes self-organized or institutionally organized work outside private households in exchange with other people (community-oriented private resp. public work). It is the most political form of care work, because in its private form it offers an indicator of deficits regarding the performance of social care institutions, and in its public form it represents demands for remedial action. In community-oriented private work, the exchange relations are not predetermined, but are agreed upon in each case. The work content benefits the people working here and their social environment; the labor power is spent in one's own interest so that the use value and not the exchange value as in formal paid work is dominating. Examples are neighborhood help, self-help groups or exchange rings, sometimes associated with local, non-convertible currencies. The latter may be experiencing a new upswing due to the social crisis, but also due to easier organizational possibilities via the internet, WhatsApp, Facebook, etc.

Community-oriented public work is work that takes place in organizational contexts. The work content does not primarily benefit the people working here and their environment. It does not facilitate self-sufficiency, but rather is work for the common good, with “good” usually understood morally, in ecological or social terms. This category includes voluntary work, activities in environmental associations, consumer, social, human rights, women's and other political organizations.

A gender-specific division of labor is also prevalent in voluntary community-oriented work. While women tend to devote themselves to social support activities, men are more attracted to hierarchical functions, which have power and prestige and are partly financially endowed (Deutscher Frauenrat, 2021). Thus, public community work, traditionally based on money-free exchange processes, is undergoing a transition, at least at the higher functional levels of civil society organization. As a result, on the one hand, a professionalization can be observed at the top level, which partly results, as a necessity, from the functional logic of organizations wanting to exert political influence. Below this level, what used to be purely voluntary work is more often than before replaced by work for a “recognition wage” far below a market payment. A typical example of this is the youth coach of a sports team who does not receive a salary but an allowance that is far below the standard wage. The same applies to volunteers in civil society organizations of all kinds.

These tendencies indicate a beginning differentiation in the monetary recognition of different forms of care work. It could constitute an intermediate form of unpaid and paid work, be a beginning of monetary recognition of the value of care work, but also lead to a new low-wage sector in professional care work. The outcome does not seem to be fixed yet, and different actors pursue different interests. Therefore, it still seems possible to influence the direction of development of this important segment of care work through targeted interventions.

Paid Work

The term paid work refers to a wide range of forms of work, and forms of financial security through work. Full-time work with permanent work contracts, social security provisions and institutionally guaranteed workers' rights is socially secure, as long as the salaries are sufficient for a decent life in the respective society, i.e., not producing “working poor” (Ehrenreich, 2001)3. Part-time work includes various forms of permanent employment with working hours below full-time work. Precarious employment relationships are often temporary and without significant social benefits. They do not offer protection against dismissal, as is the case with bogus self-employed workers, or they are contracts for work and services whose remuneration is not based on the hours worked, but on a work result, or even zero-hour jobs. In addition, there is the area of self-employment and entrepreneurial work (but not unearned income without own active work, like capital rent income). Finally, we also count unemployment as part of paid work4.

Paid work is the basis of our “working society” and apart from income, also offers social contacts and—at least for many—social prestige. The former is often very pronounced in care professions such as nursing and education; the latter, on the other hand, is often less so, e.g., for employees with cleaning jobs. Care work in paid work includes paid work in an institutionalized context, and is as diverse as paid work as a whole. Teachers and doctors as typical representatives of full-time work are socially protected in most countries, while work in social welfare and community support is often precarious and organized in the form of time-limited projects. Midwives are often self-employed, and quite some trained social workers are unemployed, despite the urgent need for their services.

The current, but not new developments in paid work can be described with the three terms intensification, precarisation and mechanization/automation, and these three trends also apply to care work. For example, the number of patients per care giver (nurses, doctors, …) is now so high that it is at the expense of personal care quality, and of the health and wellbeing of care givers whose emotional dedication to their work and the patients they care for is exploited. Often migrants or ethnic minority members (with specific problems in and for their communities of origin: Kofman and Raghuram, 2012), they are “overworked and underpaid” (Razavi and Staab, 2010). Temporary contracts contribute to precarisation and salaries are so low that qualified personnel were turned into working poor: in the pandemic, nurses had to make use of food banks in the UK. Sadly, while all the professions and jobs recognized as “essential” early in the pandemic were care work (nobody suggested to consider investment bankers as essential), this has not led to improvements in the living and working conditions (yet)—the real salaries are currently declining. Absence statistics point to a significantly increased need for care for those in paid work due to exhaustion caused by the time compression in paid work in combination with hierarchical labor organization. The increasing numbers of “essential workers” quitting their jobs during COVID, from lorry drivers to nurses and hospitality workers, demonstrate this significant need for better care for the carers, to maintain viable working conditions by mitigating the effects of intensification, precarisation and mechanization/automation. However, so far that development appears unbroken—the management level seems to be unaware of the increasing shop floor challenges. One reason possibly is that, according to the largest single study worldwide on narcissism (people who only care for themselves and not at all for the entity they are supposed to serve), it is not widely spread in the population at large, but a frequent phenomenon amongst business leaders and across age groups, and more prevalent in men. It results in CEOs and CFOs overestimating their own abilities and desiring constant admiration and affirmation without any reciprocity. Such people are not liked by their peers, but tolerated (although they are also the ones most likely to commit fraud and exhibit a lack of integrity) as they do not hesitate to take socially harmful decisions to enhance profit levels. So their influence shapes corporate cultures (Auxenfants, 2021). Another reason particularly affecting women is the androcentric institutional structure of our societies which creates employment for unfettered, male connoted singles with no social responsibilities, the imagined homini oeconomici of neoliberal theory, and discriminates against those employees actually or potentially involved in care work. As a consequence, in the UK three out of five women say their caring responsibilities for children and other vulnerable or elderly relatives are preventing them from applying for a new job or promotion, while only one in five men says the same, and even among women who identify as joint carers, 52% say they do “more than my fair share”, in comparison to 10% of men, mostly because their partner's working pattern or culture is unsupportive of work and care (BITC, 2022).

Regarding mechanization/automation, electronic “helpers” are supposed to save human labor and thus increase productivity, not only in diagnosis but also in care. The human attention and empathy required by care work cannot be replaced by artificial intelligence and offers a mere pseudo-understanding that does not solve problems, but ultimately throws those in need of help back on themselves. Relationality with machines is hardly possible, even in those cases when the care receivers are able to build a mutual if asymmetric relationship (which is often not the case)—although they “have more time,” at best such a substitute can create the illusion of attention like the cuddle machines for patients with dementia.

Care giving work can either be organized in institutions created for this purpose, from day care centers via schools, hospitals and nursing homes to doctors' surgeries and food banks, or it can be provided as an external service, e.g., by cleaning firms, to the community or in households. Such personal and household services (PHS) contribute to the domestic well-being of (chosen) families and their members. In the EU, they consist of about 60% person-related care work (e.g., care for children, the elderly and people with disabilities) and 40% household-related work. This includes, for example, assistance with housework, ironing, domestic repairs, and gardening (European Federation for Services to Individuals, 2019), often provided by non-for-profit organizations (although the commercialization pressure is strong). However, amongst those employed in civil society organizations such as NGOs and foundations, the gender imbalance is as obvious as in the commercial sector: 70% of employees are women, while on the leadership level the female share is only 40%. In international average, a man has three times as good a chance to reach a leadership position in a civil society organization than a woman (in Germany even 5 times) (FAIR SHARE of Women Leaders e.V., 2021, https://fairsharewl.org).

Mixed Work

The four-dimensional unity of overlapping, parallel or consecutive forms of work has been referred to as “mixed work” (Hildebrandt, 1997, Figure 1). It goes hand in hand with mixed experiences, requires or shapes mixed qualifications and leads to mixed incomes. Mixed work is first of all a descriptive notion without normative implications—it is not a priori “good work.” While if realized as a self-chosen combination of work and income forms and hours, mixed work can contribute to the quality of life, it can also be an expression of social hardship, for example when a single mother is forced to perform all forms of work in parallel and alone. Especially provisioning and nursing work as part of mixed work is very often stressful, unpleasant, externally determined and little recognized, and is composed differently in different biographical phases (Brandl and Hildebrandt, 2002). The fact that it is still predominantly demanded of women has become even more apparent in the pandemic (Giurge et al., 2021). Emerging research suggests that the crisis and its subsequent shutdown response have resulted in a dramatic increase in this burden; it is likely that the negative impacts for women and families will last for years without proactive interventions (Power, 2020). In the UK, for instance, when lockdown happened, women were more likely to be furloughed and working mothers were more likely to lose their jobs than working fathers (BITC, 2022).

Figure 1. A broader concept of work. Source: Hans-Böckler-Stiftung (2000). Pathways to a sustainable future. Results from the work and environment interdisciplinary project. HBS, Düsseldorf; modified.

Provisioning and nursing work, and community work, private and public, are also referred to collectively as reproductive work; we use the term here in its feminist rather than in its Marxist, production-focussed interpretation. Reproductive labor in this sense is reproductive for the production process, but at the same time highly productive for society and its wellbeing (Biesecker and Hofmeister, 2007, 2010). The patterns of separation between such unpaid and paid work are not given by nature, but—as already explained—are socially produced and changeable. Since the distribution of paid and unpaid work has so far often followed gender-specific role attributions, gender justice is a central issue for the future-oriented design of working environments.

To be a contribution to overall welfare, mixed work requires a framework of social and institutional protection, accident insurance and safety regulations, but above all through social recognition of the extent and quality of the (care) services provided. As human preferences are context dependent and change over time, a changing composition of mixed work over the working life (paid and voluntary) will most probably emerge. This requires a modernization of the welfare state, so that support is provided in phases dedicated to chosen family/provisioning work, with low or no income from paid work. As a rule of thumb, community work for the public good is complementary to paid work, but in a variety of cases it can become so time consuming that either professionalization occurs, turning it into paid work, or compensation payments are required, for instance for members of citizen juries or those deeply involved in public participation processes. Consequently, for community work a decision should be taken case by case, but this as well requires institutional settings which can respond to the respective situation.

One way to contribute to the necessary value recognition change is through counting unpaid care work for later pension calculations, for instance by extending the parental leave with equal share obligations, and having similar regulations for other forms of unpaid care—this would avoid female old age poverty resulting from low pensions. Another option would be qualification measures in unpaid work offering testified certificates that are also recognized as valid qualification proofs in professional work. If proof of care experience were a condition for management positions in the formal economy, companies would probably be managed differently, not only by reverting the promotion of narcistic characters into its opposite. Mixed work could also level the playing field between gender insofar as a broader experience can modify subjective value attribution. So far, women tend to better recognize and value the social cost of professional advancement, making them considering it as equally attainable, but less desirable than men tend to do (Gino et al., 2015).

Recognition of all forms of socially useful work would increase permeability between different forms of work and thus promote the creation of freedom of choice, which in turn is an important component of quality of life. Therefore, permeability and the gender-equitable shaping and distribution of reproductive/care as well as paid work are one of the necessary concerns of a socio-ecological transformation, and a major challenge for a still androcentric society (Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, 2000; Spangenberg, 2003).

Such considerations are of central importance for the future of care work. After 20 years of stagnation, discussions about the forms and extent of a reduction of the standard definition of full-time working time are picking up speed again. In the future, there will be probably more phases of life in which a needs- and gender-appropriate distribution of unpaid and care work will be possible to realize, with a return to paid work still part of the life plan. Only in the context of working time models and substitution processes will it be possible to estimate the extent and content of future care work.

Care in Crisis

For some years now, an eco-social crisis of care work has been observed; it can be illustrated with data from the German Statistical Office's time use survey 2012/13 (the survey is taken every 10 years) (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2015a,b). According to these data, provisioning work for the chosen family is in average 3:07 hours a day, and community work 0:21 hours. Provisioning is mainly composed of work in the kitchen (0:40), shopping (0:34), housekeeping (0:27), garden and pets (0:20), travel (0:17) and caring for children (0:13). This also illustrates why community work can be easily accompanying paid work, while for provisioning work this is more of a challenge. Women provide 61% of this care work, with a daily average of 4:10 hours (men 2:45). As compared to 20 years earlier, the total volume of unpaid chosen family and community care work has been declining, from 3:58 hours (1992) to 3:28 hours (2012). Women reduced their contribution from 5:00 hours (1992) to 4:10 (2021), and men theirs from 2:48 (1992) to 2:45 (2012) (Statistisches Bundesamt, 1995a,b).

In paid work the distribution as well as the dynamic is the opposite: the average daily paid work is 2:43 hours (2012); 1992 it was 3:14, with men working 3:19 hours per day in paid work (1992: 4:25 hours) and women 2:19 (1992: 2:11). In total, paid work now counts for 44% of all work done, and unpaid work for 56%. Comparing the data with the 1992 survey reveals that while the tasks have been changing and the allocation between paid and unpaid work has been fluid, women have reduced their time in unpaid (mostly care) work, while men have reduced their time in paid work without shouldering additional unpaid work. As a result, even if additional time has been invested in paid care work, it is by far not enough to compensate for the loss in the unpaid care. Although of the total daily average working hours, paid and unpaid added, of 6:11 hours (1992, 7:12) about two thirds are care work, the trend—which is expected to continue—is toward a “care-less” society and a challenge to sustainable development (Spangenberg, 2002). This is all the more worrying as the demand for care work is increasing as demographic developments are exacerbating the situation through increased care work demand for an aging population, and the climate crisis threatens to significantly increase the pressure on the health system (Romanello et al., 2021), while a scarcity of paid work is emerging in this sector—in Germany, the estimated deficit is almost 200,000 workers caring for the elderly by 2030.

In addition, there is an increase in—often part time—female employment, curtailing the time available for unpaid reproductive work. Add to this the said trend toward intensification, and the resulting exhaustion from time compression will increase the demand for care even further, within and beyond the professional working life.

Obviously, neither paid nor unpaid care work are limitless but shrinking resources in times of increasing demand, which in a market economy means they should fetch a high price, in money or else. Instead we observe precarisation, caused by the serious discrepancy between the practice of utilization and the rationality of valuation or non-valuation in the societal treatment of care work, resulting in badly paid jobs and a lack of recognition for unpaid care work as described above. However, as the outburst of voluntary help efforts in both the COVID and the Ukrainian war crises have shown, there is a high potential of willingness to care for people suffering, be it in terms of care work, or—as in case of the flood victims in summer 2021—in both labor and financial donation terms. Parts of that may be available on a more regular basis, if the conditions are right.

Designing work according to such ideas places not only a heavy burden on the care givers, but also alienates them from their clients, the receivers of care. One way to address at least part of these challenges has been developed in the Netherlands, where the nurse-led community care network Buurtzsorg since 2006 successfully established a different approach, based on rotating self-management of small teams and informal networks to tailor their care services to the needs of the local community, resulting in significant cost reductions. That the largely bureaucracy-free model has expanded to more than 10,000 nurses and assistants working in 850 self-managed teams in 25 counties, with high staff commitment and client satisfaction levels which are the highest of any healthcare organization, testifies for a demand for such new approaches, complementing specialized hospital treatments (https://www.buurtzorg.com/about-us). All these factors combine to create the risk that eco-social problems will multiply exponentially and that the potential of care work will be lost in the longer term.

Care Work and the Environment

That care, environment and sustainability are interlinked has long been an issue of debate (Spitzner and Röhr, 2011; Floro, 2012). The interaction works both ways—the way we practice care affects the environment, and the state of care influences how we relate to and care for the environment, in consumption and other practices (Yates and Evans, 2016). Hence we address both perspectives, starting with the practices of care work while having in mind that we talk about citizens in different roles, who through political engagement can challenge the rules which apply to them in their role as consumers.

The Environmental Impact of Care Work

In material terms, the ecological consequences of paid and unpaid care work can be related to the consumption of raw materials and energy and the intensity of land use associated with the production and consumption of care services and the goods this requires. The resource consumption resulting from the transformation of nature by human work into products is not on the one hand determined by the volume of goods demanded, which is increased by the dedication to growth and moderated by sufficiency, and by the efficiency of resource use (despite the rebound effects which necessarily come with efficiency, and which are the flipside of any win-win strategy for efficiency improvement, Reimers et al., 2021), which in turn is significantly influenced by the form of organization of care work.

Generally, it can be said that industrial production has a high efficiency of product-specific resource use in the production of goods (including services), which clearly exceeds that of most forms of material goods produced in work as a self-provider. On the other hand, such goods are mostly repairable and are used longer (in care as in other work) due to the higher emotional attachment to the product (Anwar et al., 2011). However, which products we use and which services we demand is not an individual free choice based on personal preferences by the atomistic individuals on the micro level economic theory postulates. While preferences play a role, decisions are taken in a social context, most often on the meso level of chosen families and households (Gram-Hanssen, 2008). Choices are restricted not only by law, but also by social norms and embedded in routines and social practices, which are enforced not by legal means but through emotions. Such norms are not constant but evolve, often demanding a resource-intensive way of providing care, for instance by using products or technologies being advertised (Røpke, 1999; Shove, 2003). Living in core families necessitates fragile elder relatives moving to care homes, or, if aging in place, being supported by mobile health and provisioning services—an increasing part of road traffic. Furthermore, macro level trends like communication habits and fashion co-evolve with the advertising of certain goods or brands (influencers play a role here) create demand in the care sector as much as in other sectors, e.g. for specific nutrition or cleaning products. The vast majority of goods is not discarded for being no longer functional, but not being fashionable any more. Political and legal interventions play a role too, like the COVID-19 mask obligations, and interact with the prevailing work situation. In particular, the time compression in the professional health care sector enforces the use of one-way products, resulting in hospital waste being the largest fraction of COVID-19 induced waste.

Sufficiency is an attempt to counter the ever increasing consumption levels, which in affluent countries do not enhance the life satisfaction anyway (Kahneman and Deaton, 2010; Wilkinson et al., 2011). The main routes to sufficiency discussed so far are absolute reductions, modal shifts, product longevity, and sharing practices (Sandberg, 2021), and they can be applied to care as well. For instance, in order to increase the useful life of products, infrastructures such as repair cafés and maker spaces are necessary, in which users, individually or collectively, do their self-providing work and sometimes provisioning work. These infrastructures themselves are often operated in community work. To move from an extensive to an intensive form of use of goods, sharing is another option, in particular if organized non-commercially in community work, while commercial sharing in paid work is often a means of increasing product sales (Clausen et al., 2017). Non-commercial sharing of means of production, e.g. tools or means of transport, is typical for community work, which also reduces resource consumption (Scholl et al., 2018).

However, for such options to become mainstream, a cultural change is necessary, including a changed perception of the value and importance in particular of unpaid care work for the chosen family and the community.

Care and Pro-environment Behavior

Care work can provide emotional bonding between humans as it safeguards against potential threats by assuring the proximity to caring and protective others. When individuals feel this as a reliable given, the activation of the caregiving behavioral system is facilitated: reliable care availability is a social process with positive feedback loops. Nisa et al. (2021) have shown that this situation does not only affect immediate and social relations, but also influences how much people care about climate change through an increased empathy for humanity even in conservative persons otherwise not inclined to climate change mitigation actions.

Hence a sufficient level of emotional bonding, supported by social networks of chosen family care, can facilitate not only community care, but even the relatively abstract notion of empathy with humanity. Among younger “digital natives,” for whom social bonding has become hybridized with a mixture of personal, face-to-face and technology facilitated, long distance contacts, developing such a broader perspective appears particularly plausible—it might even be one of the processes providing for the success of movements such as “Fridays for Future.”

This in turn is a condition for stringent policy action in times of group conflicts in many societies: the empathy for and identification with meta-groups and their vital interests, in this case environmental health and sustainable development.

Outlook and Goals

Care and housework is no private affair—it keeps our economic system function through a process of productive reproduction (Biesecker and Hofmeister, 2007) and should therefore be recognized as constitutive and hence valuable for the society and its economy. Consequently, most recommendations and demands do not focus of individual behaviors and attitudes, but on necessary systemic changes enabling good care as part of the overall transformation of work.

Under current policies, however, the trends of intensification, precarisation and mechanization/automation described are likely to continue in all sectors. In paid care work, mechanization could facilitate many work processes that today still involve heavy physical workloads, but not the mental work that is central to care. Digitalisation allows for further intensification and poses the risk of influencing paid care work mainly in a negative manner through the transition from working time to work output as a basis for remuneration: contracts for work and labor, bogus self-employment and freelancers are evidence of this. Finally, flexibilisation, with working time accounts and working time flexibilisation, offers on the one hand possibilities of enhanced self-determination in the organization of work. On the other hand, there is the threat of income losses and the expansion of fixed-term, part-time and temporary work, which contribute to precarisation (Spangenberg, 2011). On the part of the non-privileged, subjective precariousness leads to insecurity and thus to blackmail exposure. This is especially true in paid work, with the consequence that, for example, unpaid overtime is accepted without contradiction—a particularly widespread phenomenon in care work, where employees' intrinsic motivation and ethical principles are abused and instrumentalised against their rights and material interests.

However, while the pandemic may turn out to be the straw that broke the camel's neck for the health system, it may also turn out otherwise: the fact that salary increases in the health sector were too low to compensate for inflation, and hence in the midst of a pandemic health workers were confronted with a further decline of their often already low wages has led to industrial action in the UK and Germany, an unusual process in care work, and the riders of delivery services have gone on strike despite their social vulnerability. Both groups could count on public support and sympathy, as the public appears to better understand the importance of essential workers, most of them care workers, than many decision makers. In a nutshell, the future of paid care work is dependent on the outcome of an economic and social power conflict—which has not become easier by the amounts of money now earmarked for militarisation, which can be considered the ultimate antithesis to care. Both the budgetary implications (reduced budgets for other public goods) and the impact of this move on the public attitudes toward care work, both remunerated and unpaid, remain to be seen.

Unpaid care work in the society at large is in a different but equally precarious situation; in particular, the mental load (a significant share of care work consists of organizing) is often becoming almost unbearable (Ruffles, 2021). The overall time dedicated to chosen family and community care work has been shrinking and is expected to continue doing so, without being compensated by an increase in paid care work. At the same time, since the financial crisis of 2007–2012, the impression of personal threat has intensified even among the better-off (if and how the collectively perceived threat of the Ukraine war will modify this is not yet detectable). This has led to a lack of solidarity among the upper classes, devaluation of socially weak groups and the preservation of vested interests at (almost) any price. “Civilized, tolerant, differentiated attitudes in higher income groups seem to change into uncivilized, intolerant—brutalized—attitudes” (Heitmeyer, 2010). Such attitudes flourish in a society with loosening social cohesion, probably not least to a care deficit, a process they further boost. Distrust in authorities and institutions including science grow, and selfish, partly short-sighted and unreflected behavior prevails, as in the case vaccination refusal and violent protests against COVID-19 policies (without giving up the right to care in case of being infected).

Against these tendencies, a crisis-proof stabilization of the social-ecological infrastructures must be enforced, including robust social security systems, to cater not only to the unemployed, but also to protect people who consciously do not participate in paid work. Only resilient societies glued together by sufficient levels of care will be able to withstand foreign challenges. While care work is anything but “voluntary” and “self-determined,” the engagement of unpaid care workers, often performing a considerable part of provisioning work or community work (whether out of intrinsic motives or as a result of social role attribution, placing particular responsibility on women), will be of increasing, but not necessarily recognized, importance for sustaining the fundamentals of inclusive democratic societies.

That the rightly demanded better “recognition” of care work is neither self-sustaining nor sufficient has been shown again by the Corona pandemic (clapping, but no bonus). The vast majority of the professions identified as “essential” were those of professional care work and the role of unpaid care and community work, from home schooling to (chosen) family nursing was highly praised in the pandemic crisis. However, the verbal praise for the “essential professions” did not lead to the provision of either the necessary equipment or adequate pay if it was not gained through industrial action. As a result, between 2019 and 2020, 421,000 care workers left the sector, driven by low pay, poor working conditions and a lack of recognition (Federation of European Social Employers, 2022)—at a time where aging societies would require an increase, not a decrease of the number of care professionals. Consequently, staff shortage in paid care work is increasing across Europe with 85% of responding organizations in a poll by the Federation of European Social Employers reporting staff shortages, with 1/3 suffering from more than 10% unfilled positions, with professional care for the elderly most affected. In the area of unpaid care, much was reported about the family burdens, but the fact that a retraditionalisation took place in the process and that care work was to a large extent imposed on women was not in the foreground (Power, 2020).

In the short and medium term, it is to be feared that these tendencies will continue: already today, there are more and more (neoliberal and right-wing conservative) voices calling for a post-COVID austerity to reduce the national debt incurred in the crisis, i.e. the dismantling of state services from health to environmental protection. In doing so, they are counting on being able to replace these with the mobilization of unpaid social care work, if only this is sufficiently verbally recognized and praised. The crisis of reproductive work thus threatens to intensify to such an extent that social cohesion as a whole would be endangered: sufficient and good anchoring of care as unpaid work and improved working and payment conditions in paid work are in this respect an important prerequisite for civilized coexistence, for social sustainability in a comprehensive sense.

In the medium and long term, societal reproduction requires enabling and supportive formal and informal institutional structures to end the crisis of care. In particular, besides paid and unpaid care for the chosen family, the volume of work dedicated to the social and natural environment needs to grow to safeguard social cohesion and sustainable development. This in turn requires both a crisis-proof organization of paid work, social security for unpaid care work, and a shift of societal values:

➢ First of all, in times of increasingly frequent patchwork biographies, in which unemployment and extended vocational training or retraining interrupt employment, an unemployment insurance is necessary that safely carries those affected through these intermediate employment phases, i.e., does not expire after too short a time. These periods should be increasingly used to acquire qualifications, also and in particular in care work.

➢ Secondly, a functioning welfare state needs a poverty-proof basic income of whatever model, but including a minimum pension above the poverty threshold. In Germany, for instance, 60% of all married women have a work income below thousand €/month and are hence at risk of old age poverty (Zykunov, 2022). In this context, the catalog of benefit-free qualifying periods, such as education, social service and parenthood, should be gradually extended to other areas of unpaid care work and be combined with publicly funded health and accident insurance for times in care work. Already today, in some countries the pension insurance system fakes periods of membership for bringing up children and caring for them, and, like for military services, pays tax-financed allowances, etc. Hence in these countries, the social security coverage of unpaid but socially important care work is an established part of the pension system, but it should be expanded with a view to the socially necessary provisioning, nursing and community work.

➢ Thirdly, it makes sense to recognize and support care work through qualification certificates which are also recognized in the employment sphere and gradually become a prerequisite for certain leadership functions. This would not only enhance the permeability between paid and unpaid work, but could contribute to better working environments throughout the production sector. For example, proven participation in reproductive work (e.g., caring work in the charitable sector) for women and men could be evaluated as a qualification necessary for professional management tasks and classified as social insurance-relevant work with pension entitlement. It would also be the basis for better management, emphasizing the care in work, and increasing the work satisfaction (which in turn would reduce unnecessary compensatory consumption). It could also help introducing gender and care sensitive forms of work organization in the industrial and broader service sectors.

➢ Fourthly, paid care work must be made more attractive by reducing working hours, making work easier and increasing wages while making them mandatory for all employers, also in order to end the “flight from care” (Whillans et al., 2017). This should be accompanied by improved access to technical and financial assistance for care and community work, strengthening the complementarity of the different forms of care work instead of ever increasing substitution. Simultaneously, it is necessary to rethink the organization of formal work which so is often designed to fit to individuals, mostly male, with no caring obligations, but cannot accommodate single parents.

➢ Finally, as the assumption of permanent economic growth and ever rising standards of living will be disappointed by the effects of increasing environmental crises, new attitudes will emerge, worse or better. As Nisa et al. (2021) have shown, securing a good level of all kinds of care could contribute to attitudes which help overcoming not only the prevailing environmental, but also the social crises and enhance the resilience of societies—a process which would be facilitated by focussing on a different philosophical basis in education and everyday life than the prevailing utilitarian world view (Whiting et al., 2018).

On this basis, non-professional care work could make a decent contribution to the social security of individuals and to the overall standard of living. To this end, as shown, it is necessary to free it from its function of being a vicarious agent of paid work and to make it an just as attractive option as paid work. A contribution to this would be to simplify the switching between paid and unpaid work according to the concept of mixed work. Such an increased permeability between the different spheres of work would allow the individual to make a life-stage-specific choice regarding the respective composition of his/her work, choosing from different forms of paid and unpaid work, without precluding future choices for a different composition (Hildebrandt, 2002).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In German, profession (“Beruf”) and vocation (“Berufung”) are closely related, giving the profession a social and ethical meaning “jobs” are devoid of. This explains much of the training-intensive education system for many professions, and the strong rule systems inhibiting outsiders practicing a profession as a job.

2. ^A significant share of the economic growth since the beginning of the industrial revolution can be explained by the shift of formerly unpaid agricultural work into the formal labor sector, and the migration of local populations working outside the monetised economy, e.g., in subsistence agriculture, to the monetised world of factory work.

3. ^Obviously, terms like “full-time,” “socially secure” and “decent life” are socially defined and change over time.

4. ^In German statistics, paid work also includes unemployment; according to German social law, the condition for receiving unemployment benefits is to be available to the labor market full-time at all times.

References

Anwar, A., Gulzar, A., and Anwar, A. (2011). Impact of self-designed products on customer satisfaction. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 3, 546–552. Available online at: ijcrb.webs.com

Auxenfants, M. (2021). Zortify Points Out Narcissism As A Risk Factor For Businesses. Silicon Luxembourg. Available online at: https://www.siliconluxembourg.lu/zortify-points-out-narcissism-as-a-risk-factor-for-businesses/ (accessed April 23, 2021).

Becker, R. (1998). Eigenarbeit—Modell für ökologisches Wirtschaften oder patriarchale Falle für Frauen? W. Bierter, Winterfeld, Uta von.Zukunft der Arbeit—welcher Arbeit? Berlin, Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag.

Biesecker, A., and Hofmeister, S. (2010). Focus: (Re)productivity: sustainable relations both between society and nature and between the genders. Ecol. Econ. 69, 1703–1711. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.03.025

BITC (2022). Who Cares? Transforming How We Combine Work With Caring Responsibilities. Available online at: https://www.bitc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/bitc-gender-report-whocares-march2022.pdf

Brandl, S., and Hildebrandt, E. (2002). Zukunft der Arbeit und soziale Nachhaltigkeit. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Brettin, S. (2021). Feministische Perspektive auf landwirtschaftliche Produktion. Ökologisches Wirtschaften 36, 28–29. doi: 10.14512/OEW360428

Clausen, J., Bienge, K., Bowry, J., and Schmitt, M. (2017). The five Shades of Sharing. Ökolgisches Wirtschaften 32, 30–34. doi: 10.14512/OEW320430

Collier, A. F., and Wayment, H. A. (2018). Psychological benefits of the “maker” or do-it-yourself movement in young adults: a pathway towards subjective well-being. J. Happ. Stud. 19, 1217–1239. doi: 10.1007/s10902-017-9866-x

Deutscher Frauenrat (2021). Ehrenamtliches Engagement von Frauen in Verbänden, Vereinen und Parteien für Demokratie und Gesellschaft. Berlin: Deutscher Frauenrat. Available online at: https://www.frauenrat.de/shortinfo/ (accessed February 12, 2022).

Ehrenreich, B. (2001). Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America. New York: Metropolitan Books.

European Federation for Services to Individuals (2019). 10 Proposals for high quality accessible and affordable PHS. Brussels: EFSI.

FAIR SHARE of Women Leaders e.V. (2021). FAIR SHARE Monitor 2021. Available online at: https://fairsharewl.org/de/german-monitor-2021/

Federation of European Social Employers (2022). Staff Shortages in Social Services across Europe. Brussels: FESE.

Floro, M. S. (2012). The crises of environment and social reproduction: Understanding their linkages. J. Gender Stud. 15, 13–31. doi: 10.1080/15240657.2012.640218

Gino, F., Wilmuth, C. A., and Brooks, A. W. (2015). Compared to men, women view professional advancement as equally attainable, but less desirable. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 12354–12359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502567112

Giurge, L. M., Whillans, A. V., and Yemiscigil, A. (2021). A multicountry perspective on gender differences in time use during COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118:e2018494118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2018494118

Gram-Hanssen, K. (2008). Consuming technologies—developing routines. J. Clean. Prod. 16, 1181–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2007.08.006

Großer, E., von Jorck, G., Kludas, S., Mundt, I., and Sharp, H. (2020). Sozial-ökologische Infrastrukturen—Rahmenbedingungen für Zeitwohlstand und neue Formen der Arbeit. Ökologisches Wirtschaften 35, 14–15. doi: 10.14512/OEW350414

Hans-Böckler-Stiftung (ed.), (2000). Arbeit und Ökologie, Endbericht. Düsseldorf: Hans Böckler Stiftung.

Heitmeyer, W. (2010). “Krisen—Gesellschaftliche Auswirkungen, individuelle Verarbeitungen und Folgen für die gruppenbezogene Menschenfeindlichkeit,” in Deutsche Zustände, Folge 8, ed. W. Heitmeyer (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp), 13–46.

Hildebrandt, E. (1997). “Nachhaltige Lebensführung unter den Bedingungen sozialer Krise—einige Überlegungen,” in Nachhaltige Entwicklung—Eine Herausforderung an die Soziologie, ed. K.-W. Brand (Opladen: Leske + Buderich), 244–258.

Hildebrandt, E. (2002). “Nachhaltige Entwicklung und die Zukunft der Arbeit. Soziale Nachhaltigkeit: Von der Umweltpolitik zur Nachhaltigkeit?,” in Informationen zur Umweltpolitik 149. (Wien: Bundeskammer für Arbeiter und Angestellte), 126.

Jürgens, K., and Reinecke, K. (1998). Zwischen Volks- und Kinderwagen. Auswirkungen der 28,8-Stunden-Woche bei der VW AG auf die familiale Lebensführung von Industriearbeitern. Berlin: Edition Sigma.

Kahneman, D., and Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 16489–16493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011492107

Kofman, E., and Raghuram, P. (2012). Women, migration, and care: explorations of diversity and dynamism in the global south. Social Polit. Int. Stud. Gender, State Soc. 19, 408–432. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxs012

Koo, E. (2018). “Where Is the Value of Housework?” Re-conceptualizing Housework as Family Care Activity. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Morganti, E., Seidel, S., Blanquart, C., Dablanc, L., and Lenz, B. (2014). The impact of E-commerce on final deliveries: alternative parcel delivery services in France and Germany. Transp. Res. Proc. 4, 178–190. doi: 10.1016/j.trpro.2014.11.014

Mückenberger, U. (1990). Allein wer Zugang zum Beruf hat, ist frei sich für Eigenarbeit zu entscheiden. Formen der Eigenarbeit. Heinze: Westdeutscher Verlag, 197–211.

Nisa, C. F., Belanger, J. J., Schumpe, B. M., and Sasin, E. M. (2021). Secure human attachment can promote support for climate change mitigation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118:e2101046118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101046118

Power, K. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 16, 67–73. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2020.1776561

Razavi, S., and Staab, S. (2010). Underpaid and overworked: a cross-national perspective on care workers. Int. Labour Rev. 149, 407–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1564-913X.2010.00095.x

Reimers, H., Jacksohn, A., Appenfeller, D., Lasarov, W., Hüttel, A., Rehdanz, K., Balderjahn, I., and Hoffmann, S. (2021). Indirect rebound effects on the consumer level: a state-of-the-art literature review. Clean. Responsib. Consump. 3, 100032. doi: 10.1016/j.clrc.2021.100032

Romanello, M., McGushin, A., Di Napoli, C., Drummond, P., Hughes, N., Jamart, L., et al. (2021). The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. Lancet. 398, 1619–1662. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(1021)01787-01786

Røpke, I. (1999). The dynamics of willingness to consume. Ecol. Econ. 28, 399–420. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(98)00107-4

Sandberg, M. (2021). Sufficiency transitions: a review of consumption changes for environmental sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 293, 126097. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126097

Scherhorn, G. (2000). “Die produktive Verwendung der freien Zeit,” in Zukunftsfähigkeit als Leitbild? Leitbilder, Zukunftsfähigkeit und die reflexive Moderne, eds E. Hildebrandt, G. Linne (Berlin: Edition Sigma), 343–377.

Scholl, G., Behrendt, S., Gossen, M., Henseling, C., Ludmann, S., Pentzien, J., and Peuckert, J. (2018). Ökobilanz der sharing economy: Teilen allein nützt der Umwelt wenig. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 27, 176–177. doi: 10.14512/gaia.27.1.14

Schultz, I. (Ed). (1993). GlobalHaushalt: Globalisierung von Stoffströmen-Feminisierung von Verantwortung. Forschungstexte des Instituts für Sozial-Ökologische Forschung. Frankfurt: Verlag für Interkulturelle Kommunikation.

Shove, E. (2003). Converging conventions of comfort, cleanliness and convenience. J. Consum. Policy 26, 395–418. doi: 10.1023/A:1026362829781

Shove, E., Pantzar, M., and Watson, M. (2012). The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Spangenberg, J. H. (2002). The changing contribution of unpaid work to the total standard of living in sustainable development scenarios. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 5, 461–475. doi: 10.1504/IJSD.2002.003764

Spangenberg, J. H., (ed.). (2003). Vision 2020. Arbeit, Umwelt, Gerechtigkeit: Strategien und Konzepte für ein zukunftsfähiges Deutschland. München: Ökom Verlag.

Spangenberg, J. H. (2011). Arbeitsgesellschaft im Wandel: Die Grenzen der Natur setzen neue Signale. Politische Ökologie 29, 15–24. https://www.academia.edu/657105/Arbeitsgesellschaft_im_Wandel_Die_Grenzen_der_Natur_setzen_neue_Signale

Spangenberg, J. H., and Lorek, S. (2019). Sufficiency and consumer behaviour: from theory to policy. Energy Policy 129, 1070–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2019.03.013

Spitzner, M. (1997). “Distanz zu Leben, Arbeit und Gemeinschaft? Über den “göttlichen Ingenieur” und die Verkehrswissenschaft im konstruierten Raum,” in Vom Zwischenruf zum Kontrapunkt, ed U. v. Winterfeld, A. Biesecker, B. Duden, M. Spitzner (Frauen, Wissenschaft: Natur. Bielefeld, Kleine Verlag), 53–84.

Spitzner, M. (1999). “Krise der Reproduktionsarbeit—Kerndimension der Herausforderungen eines öko-sozialen Strukturwandels. Ein feministisch-ökologischer Theorieansatz aus dem Handlungsfeld Mobilität,” in Nachhaltigkeit und Feminismus: Neue Perspektiven—Alte Blockaden, eds I. Weller, E. Hoffmann, S. Hofmeister (Bielefeld: Kleine Verlag), 151–165.

Spitzner, M., and Röhr, U. (2011). Klimawandel und seine Wechselwirkungen mit Geschlechterverhältnissen. Forum Wissenschaft 2011, 4–9. https://www.linksnet.de/artikel/27213

Statistisches Bundesamt (1995a). Die Zeitverwendung der Bevölkerung. Methoden und erste Ergebnisse der Zeitbudgeterhebung 1991/92 (Tabellenband I). Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

Statistisches Bundesamt (1995b). Die Zeitverwendung der Bevölkerung. Familien und Haushalte (Tabellenband III). Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2015a). Zeitverwendungserhebung. Aktivitäten in Stunden und Minuten für ausgewählte Personengruppen 2012/2013. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2015b). Zeitverwendungserhebung, ZVE 2012/2013. Qualitätsbericht. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

Whillans, A. V., Dunn, E. W., Smeets, P., Bekkers, R., and Norton, M. I. (2017). Buying time promotes happiness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 8523–8527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706541114

Whiting, K., Konstantakos, L., Carrasco, A., and Carmona, G. L. (2018). Sustainable development, wellbeing and material consumption: a stoic perspective. Sustainability 10, 474. doi: 10.3390/su10020474

Wichterich, C. (1992). Die Erde bemuttern: Frauen und Ökologie nach dem Erdgipfel in Rio: Berichte, Analysen, Dokumente. Köln: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung.

Wolf, M., and McQuitty, S. (2011). Understanding the do-it-yourself consumer: DIY motivations and outcomes. AMS Rev. 1, 154–170. doi: 10.1007/s13162-011-0021-2

Yamane, S. (2021). Gender equality, paid and unpaid care and domestic work: disadvantages of state-supported marketization of care and domestic work. Jpn. Polit. Econ. 47, 44–63. doi: 10.1080/2329194X.2021.1874826

Keywords: care work, societally necessary work, paid work, reproductive work, own work, community work

Citation: Spangenberg JH and Lorek S (2022) Who Cares (For Whom)? Front. Sustain. 3:835295. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2022.835295

Received: 14 December 2021; Accepted: 23 March 2022;

Published: 21 April 2022.

Edited by:

Aurianne Stroude, National University of Ireland Galway, IrelandReviewed by:

Kiriaki M. Keramitsoglou, Democritus University of Thrace, GreeceRifat Rifat, Université de Fribourg, Switzerland

Copyright © 2022 Spangenberg and Lorek. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joachim H. Spangenberg, joachim.spangenberg@seri.de

Joachim H. Spangenberg

Joachim H. Spangenberg Sylvia Lorek

Sylvia Lorek