- 1Hubert Department of Global Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 2Gangarosa Department of Environmental Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 3Civic Fulcrum, Chennai, India

Introduction: Sanitation research in India has emphasized the disproportionate burden that unsafe and inadequate WASH can have on women and girls. However, there is a gap in research exploring women's agency in relation to their sanitation experiences, and agency is an integral domain of their empowerment.

Methods: Cognitive interviews related to sanitation and empowerment were conducted with women in three life stages in India to validate survey tools that measure urban sanitation and women's empowerment; this paper is a secondary thematic analysis of qualitative data generated from 11 cognitive interviews in Tiruchirappalli, India, that focus on agency, specifically the sub-domains of decision-making, leadership, collective action, and freedom of movement. Women had the freedom to move to and from sanitation facilities and initiatives, with no restrictions from household members.

Results: We observed differences at the household and community levels with women voicing more confidence, as well as the responsibility, to make sanitation-related decisions in the household than at the community level. Women mentioned strong trust and belief in women's sanitation-related leadership capabilities and support for women-led sanitation initiatives. However, many did not hold leadership positions themselves due to various limitations, from gendered responsibilities to women's lack of self-confidence. Women also discussed anecdotes of collectively working with other women toward improving the local sanitation environment.

Discussion: This analysis highlights the value of strong trust and confidence among women in their ability to make important sanitation-related decisions at all levels of society. Maintaining and strengthening trust in female community members and highlighting women-led groups' achievements in the sanitation space should be prioritized. Community spaces must incorporate provisions that encourage women to share sanitation-related opinions in an environment that respects their engagement. WASH programming must engage with authority figures, leaders, and officials when seeking to increase women's agency and involvement with sanitation-related issues.

1. Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly established Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 to “ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all” by 2030 (UN, 2015). Access to safe sanitation and clean water is integral for human health and wellbeing (WHO, 2022) yet an estimated 3.6 billion people lack access to safely managed sanitation services, including 494 million who practice open defecation (WHO and UNICEF, 2021). Within SDG 6, Target 6.2 emphasizes the need to pay “special attention” to the sanitation and hygiene needs of women, girls, and vulnerable populations (UN, 2015). Studies have highlighted how the division of water- or sanitation-related tasks and the challenges in accessing safely managed sanitation facilities disproportionately impact women and girls (Sorenson et al., 2011; Graham et al., 2016; Fisher et al., 2017). Specifically, social norms, power hierarchies, and inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure result in gender inequities in workloads and access to WASH services (Caruso et al., 2017, 2022a,b; Routray et al., 2017; Ashraf et al., 2022; Carrard et al., 2022).

In India, despite expanding coverage of sanitation facilities throughout the country, sanitation challenges persist for women in particular, related to their sanitation access and sanitation-related experiences, responsibilities, and decision-making (IIPS and ICF, 2021). Specifically, research in both rural and urban areas has found there to be a lack of safe, private, physically, and financially accessible toilets that adequately meet the needs of women and girls (Hirve et al., 2015; Hulland et al., 2015; Sahoo et al., 2015; Khanna and Das, 2016; Caruso et al., 2017, 2018; Saleem et al., 2019; Ashraf et al., 2022). Women's sanitation experiences in India have been found to be linked to psychosocial impacts, including anxiety, depression, and distress, even among those with access to a household sanitation facility (Hirve et al., 2015; Sahoo et al., 2015; Caruso et al., 2018). Further, a study in Rajasthan, India found that responsibilities and tasks surrounding the maintenance of household sanitation predominantly fall on women (O'Reilly, 2010). Finally, in Odisha, India women were not actively engaged—and in some cases bypassed—in decision-making for household sanitation infrastructure design initiatives (Routray et al., 2017).

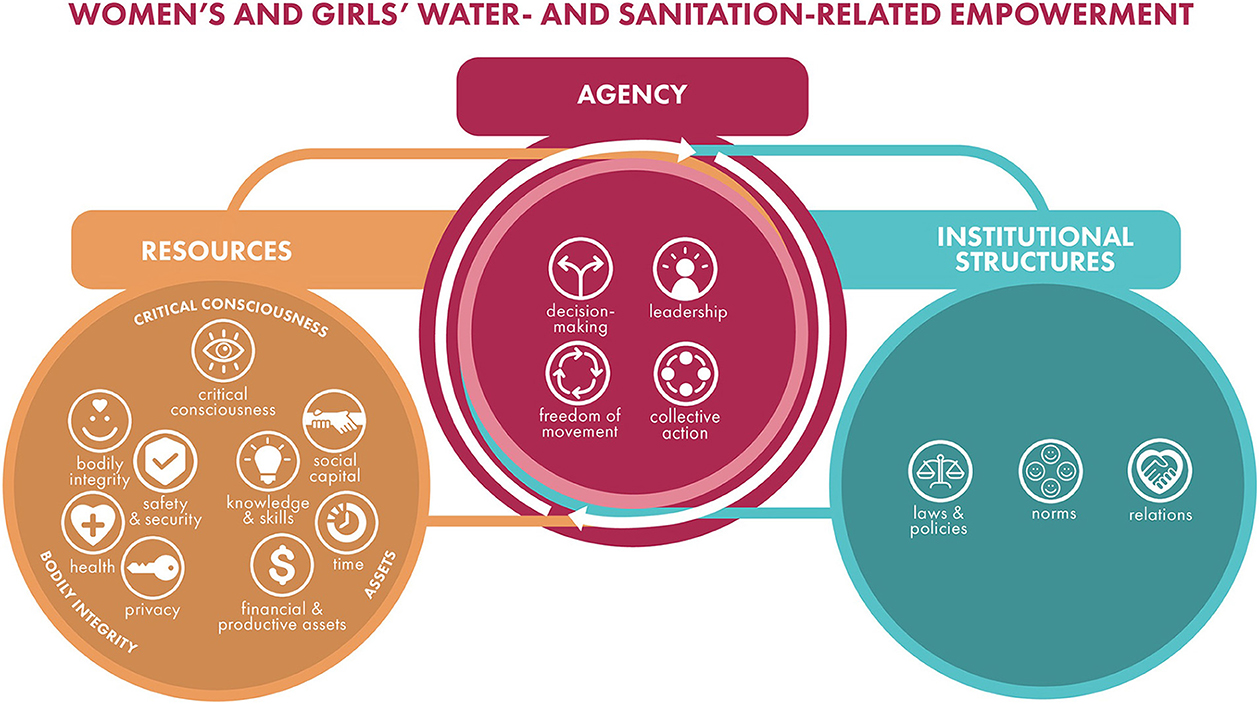

Prevailing gendered sanitation experiences and outcomes underscore the need for exploring how sanitation conditions and policies can influence women's empowerment, particularly their agency. This study adopts the conceptualization of agency from the women's empowerment framework by van Eerdewijk et al. (2017), which defines agency as “the ability to pursue goals, express voice, and influence and make decisions free from violence and retribution” (van Eerdewijk et al., 2017). It aligns with Kabeer's (1999) presentation of agency as “the ability to define one's goals and act upon them”. Existing literature on agency as a domain of women's empowerment presents it as the ability to define individual and collective goals while being able to freely act on them. This translates to agency being more than an observable action, but also as grounded in maintaining internalized motivation, meaning, and purpose toward this action (Kabeer, 1999, p. 438; Gammage et al., 2016). The present study further explores agency with a focus on the sub-domains presented in van Eerdewijk et al.'s (2017) framework: decision-making, leadership, and collective action. A recent systematic review exploring water, sanitation, and empowerment identified “freedom of movement” as an additional subdomain of agency relevant to water and sanitation, which is also included in this study (Caruso et al., 2022a). The adapted figure from the systematic review illustrates the relationship between these domains and subdomains (Figure 1) (Caruso et al., 2022a). Of the three empowerment domains explored in the review, including agency, resources, and institutional structures, the agency domain was the least explored; only one paper covered all four subdomains of agency (Caruso et al., 2022a). As a result, the review identified a need for more comprehensive research on agency and sanitation (Caruso et al., 2022a).

Figure 1. Relationship between the domains and sub-domains of women's and girls' water and sanitation-related empowerment (Caruso et al., 2022a).

This qualitative study aimed to understand women's agency related to sanitation in urban Tiruchirappalli, India. The paper is structured to cover the study methodology, followed by results in the order of agency sub-domains, and finally a discussion on key themes, findings, and implications. Organizations and policymakers working on sanitation can utilize findings to inform sanitation-related interventions that empower women and girls, with specific relevance to urban India and potentially other urban contexts.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

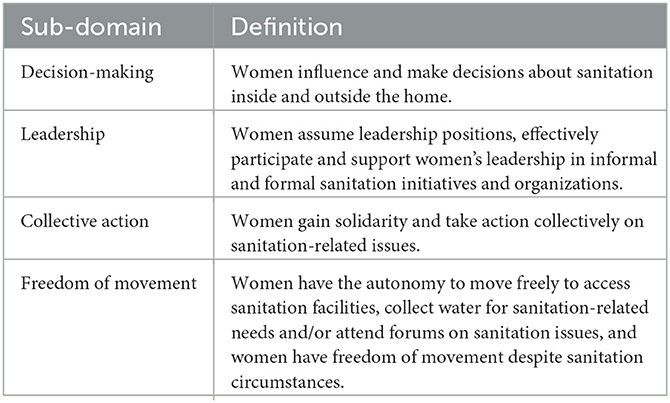

This study is a secondary analysis of textual data collected as part of cognitive interviews (CI) carried out in August 2019 as part of the Measuring Urban Sanitation and Empowerment (MUSE) project. The goal of MUSE is to develop and validate scales to measure sanitation-related women's empowerment in urban areas (Sinharoy et al., 2022). The primary goal of the CIs was to confirm the face validity of survey items and ensure they were culturally relevant and understood as intended (Beatty and Willis, 2007). CIs serve to strengthen the survey tools before large-scale deployment (Beatty and Willis, 2007). The resulting tool, called ARISE (Agency, Resources, and Institutional Structures for Sanitation-related Empowerment), measures subdomains of women's empowerment based on the model developed by van Eerdewijk et al. (2017), Sinharoy et al. (2022, 2023). As the CI data included rich responses and went beyond cognitive debriefing, there was scope for further analysis. This secondary analysis leverages the rich data collected during the agency-specific cognitive interviews, with an exploration of the subdomains i.e., leadership, decision-making, collective action, and, the newly identified subdomain, freedom of movement (Table 1) (van Eerdewijk et al., 2017; Caruso et al., 2022a). Sinharoy et al.'s sanitation-specific definitions of the agency sub-domains (Table 1), alongside Figure 1, informed this analysis (Caruso et al., 2022a; Sinharoy et al., 2022).

Table 1. Sanitation-specific definitions of the subdomains of agency (Sinharoy et al., 2022).

2.2. Study area

In Tiruchirappalli, which is in the state of Tamil Nadu in South India, 78.1% of households have access to a toilet facility (IIPS and ICF, 2021). A greater proportion of urban households in Tiruchirappalli (89.2%) have access to a toilet facility, compared to rural households (67.8%) (IIPS and ICF, 2021). 67.1% of the households in the district have improved sanitation facilities (IIPS and ICF, 2021). As of 2021, 3,483 Individual Household Latrines and 13 community toilets were built in Tiruchirappalli through the Swacch Bharat Mission (SBM), which aimed to eliminate open defecation in India and improve solid waste management (SBM, 2021). The specific neighborhood in this study was selected in partnership with the local organization IIHS (Indian Institute of Human Settlements), mainly due to its economic diversity.

2.3. Study eligibility

Women aged 18 and above who spoke either Tamil or English and lived in Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, India were eligible to participate. CIs targeted specific sub-populations of women from three life course stages (unmarried women 18–25, married women aged 25–40 years, and women aged 40 and above) as studies in India have found that women of varying life stages have different sanitation experiences, levels of agency, and decision-making power within their families (Caruso et al., 2017; Routray et al., 2017).

2.4. Recruitment strategy

Participants were recruited through convenience and snowball sampling. Trained interviewers knocked on doors in one selected neighborhood to identify eligible women across different life stages. When it was difficult to recruit enough women from a certain life stage, interviewers utilized the snowball sampling approach whereby they asked participating women or community members to recommend other potential participants who could take part in this study. Once an adequate number of women were recruited in each sub-group, interviewers stopped recruitment. A total of 11 participants from all three life stages and occupations were recruited.

2.5. Data collection

All interviewers were female, college-educated, and fluent in Tamil. Each data collection team had two members: one interviewer and one notetaker. All data collection team members underwent a 5-day training and an ethical orientation workshop. During training sessions, interviewers provided feedback to the research team about the tool to ensure that questions were both culturally sensitive and relevant to the local sanitation context. The CI guide was translated into Tamil from English.

With each eligible participant, a trained interviewer administered a short screening and demographic survey in the preferred language and then proceeded to ask the CI questions. As interviews for the larger MUSE project were domain-specific, the 11 recruited participants only answered the agency domain-specific questions. Interviewers read each survey question that was to be assessed and asked the participant to select one of the potential response options. Participants were then asked to describe what they were thinking while responding and were encouraged to describe their thought process by “thinking aloud.” This process ensured the participants' thought processes reflected the correct comprehension of the survey question. For example, if the participant answered “strongly agree” to “In this community, women have a voice in making decisions about community sanitation” in the decision-making section, she was further probed, “What does this mean to you? How would you put it in your own words?”. Interviewers also probed if participants appeared to be confused or hesitant about the wording or meaning of specific questions. This process was repeated for each question. At the end of the interview, there were open-ended questions for participants to express any further thoughts on the topics covered. Interviews lasted between 60 and 120 mins.

2.6. Data management and analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and then translated into English by trained research assistants for analysis. The transcripts were deidentified and uploaded to a folder available only to the research team to maintain participant confidentiality. After every few interviews, data collection teams debriefed with the onsite Emory MUSE team who maintained a debriefing workbook.

An initial codebook with deductive codes based on both the subdomains of agency (decision-making, leadership, collective action, and freedom of movement) and the CI guide (Supplementary material A) was developed. Each transcript was then uploaded into MAXQDA, a qualitative and mixed-method analysis computer software (version 22.1.0) (VERBI Software, 2021). The first author (RD) utilized analytic memos for the inductive code development process, noting themes and ideas generated from the data. After the inductive codes were added and the codebook (Supplementary material B) was finalized, the textual data was fully coded by author (RD) and the transcripts were organized according to these codes. The codebook development and coding process included regular meetings and communication with author (BC), and discussions with members of the Emory MUSE team, including authors AC, MP, and SS. Summary code reports were generated to begin a deeper exploration of coded data and review patterns and themes specific to each code. Applied thematic analysis explored properties and key dimensions of decision-making, leadership, collective action, and freedom of movement (Guest et al., 2012).

Salient themes alongside supporting quotes are presented in the results section and have been further validated by review of authors directly involved in data collection (SA and VR). The findings have intentionally not been quantified or represented with numbers to prevent generalization and overinterpretation of findings (Maxwell, 2010, p. 470–480; Neale et al., 2014; Hennink et al., 2020). Additionally, the data included spontaneous reporting from participants, so it is recommended to limit enumeration when not all participants had an opportunity to speak about a certain concept (Neale et al., 2014).

2.7. Ethics and consent

The MUSE study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board (USA; IRB 00110271) in the United States and by the Azim Premji University Institutional Review Board (India; Ref. No. 2019/SOD/Faculty/5.1) in India. Verbal consent to participate and be recorded was obtained immediately before each interview.

3. Results

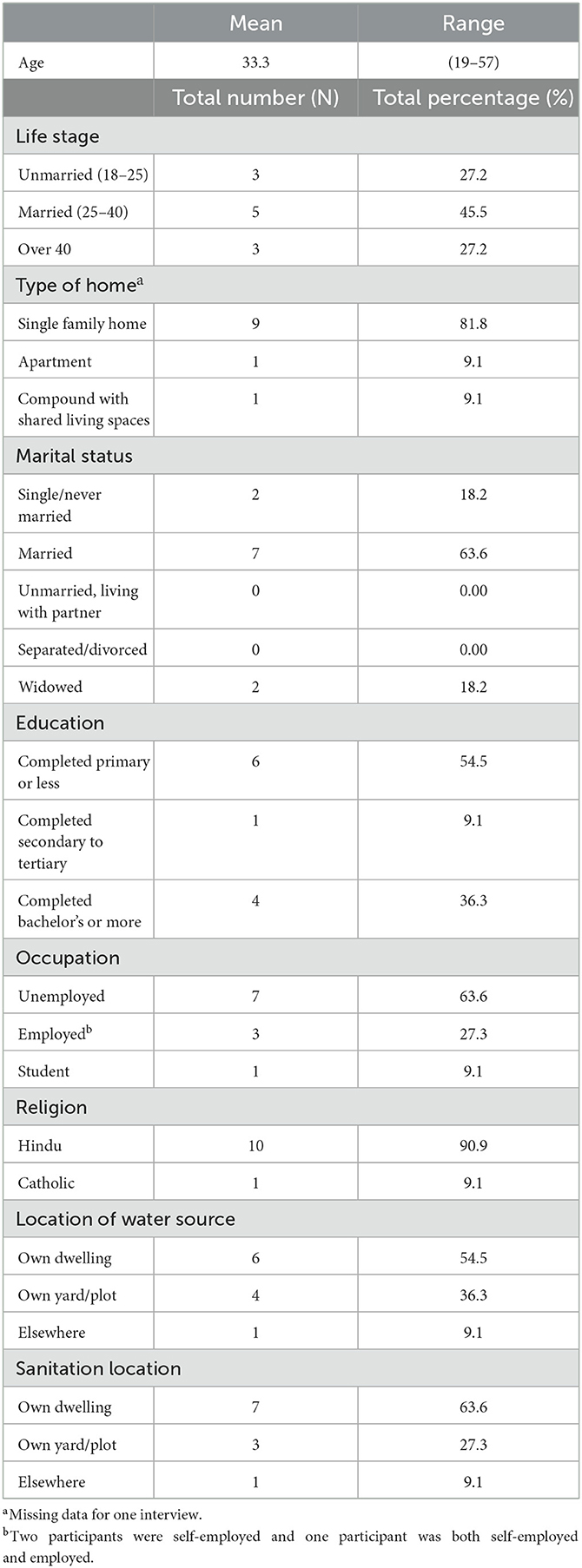

Women who were interviewed represented various life stages, educational backgrounds, and occupational statuses (Table 2). The age range of the women interviewed was 19–57 years and comprised women at three life stages: unmarried (n = 3), married (n = 5), and over 40 (n = 3). More than half of the women (n = 7) had sanitation facilities in their dwellings. All the women indicated caring for dependents and that sanitation is an issue in their community.

The results are organized by subdomains of agency—freedom of movement, decision-making, leadership, and collective action—starting with the individual level, to the household level, and thereafter, the community level. Our findings showed participants had the freedom and autonomy to move to and from sanitation facilities and initiatives, with no restrictions from household members. With decision-making, we observed differences at the household and community levels with participants voicing more confidence, as well as the responsibility, to make sanitation-related decisions in the household than at the community level. When discussing leadership, they mentioned strong trust and belief in women's sanitation-related leadership capabilities and support for women-led sanitation initiatives. However, participants did not hold leadership positions themselves due to various limitations, from gendered responsibilities to women's lack of self-confidence. Finally, for collective action, they discussed personal anecdotes of women collectively working toward improving local sanitation infrastructure and providing sanitation/hygiene education. The challenges women faced with collective action were otherwise the same as those that limited leadership. Key themes and patterns that explore women's sanitation-related experiences within each subdomain of agency were identified and are further discussed in the following sections. Of note, when discussing community-level sanitation efforts or challenges, participants sometimes referred to garbage and sewage (which remains consistent with Swachh Bharat Mission's scope for national sanitation), instead of solely toilet use which frames the definition of sanitation for this research.

3.1. Freedom of movement

Participants reported having the autonomy to move freely to access sanitation facilities and attend sanitation-focused meetings and events most of the time. When barriers to women's sanitation-related freedom of movement were discussed, they were often at the societal and community level, rather than at the household level. In urgent situations, participants expressed the freedom to use toilets in other known households: “Now there is a latrine, there's one at uncle's house. In that emergency, we can go there” (CI01, Married).

While participants could freely access sanitation facilities and attend sanitation-related meetings, there was overall agreement that women should inform their family members when leaving the house to ensure safety and awareness of their whereabouts: “If I am going to a program, in the house you should let them know, right?... The people in the house must know that I'm going here, to let them know, definitely I inform and then go” (CI07, Unmarried). Most participants did not seek permission for any sanitation-related movement and had a common belief that women, regardless of whether married or unmarried should not have to ask for permission to leave the house for sanitation purposes: “I: Do you have to ask a lot, or can you go without asking? P: Without saying we can go. We can go and come [back].” (CI02, Married). In contrast, two married participants believed that those who are newly married may have restrictions on leaving the house for sanitation-related purposes or initiatives. Only a few participants required accompaniment if they wished to attend sanitation-focused meetings or programs: “Alone if I go, they won't let me. If 4 people go together, then they'll ask me to go and come back.” (CI08, Married). In situations where only one person was accompanying the woman, family members felt comfortable only if the person accompanying was a relative or a close friend.

3.2. Decision-making

3.2.1. Household decision-making

Most participants believed that women should make decisions about sanitation and water issues in the household and that the men in the household should seek women's views if they make decisions. Many participants described how women would influence their family's decisions, while others noted that women's influence was limited. One participant said, “If women tell, men will listen” (CI−08, Married) about all household-related decisions. Joint decision-making with their husband, when possible, was considered best for their household's sanitation infrastructure and environment. However, if mutual decision-making was not possible, many believed that women should be the deciding authority for sanitation-related issues.

Participants generally voiced confidence in women's ability to participate in household decision-making. They said that family members, including husbands, were typically receptive and supportive of women's sanitation-related decisions and choices. Participants also agreed that in the family, women have the right to decide where toilets or latrines should be located. A key theme was the perception that women know what is best for the children and family members, and so husbands will listen to women's opinions: “Only when a woman is involved, can a man do.” (CI11, Over 40). All the participants described having a decision-making influence in determining how a sanitation facility environment is cleaned and maintained. However, some participants expressed limited decision-making influence regarding their household's sanitation construction and believed it was acceptable for husbands to make the final decision without seeking their views. This idea will be further expanded in the section below that discusses women's perceptions of men's decision-making roles at the household level.

An overarching belief was that women had primary responsibility for the care of the household's sanitation needs and environment, so their role in making decisions about cleaning and maintenance of the household sanitation facility was a foregone conclusion rather than an active expression of their agency. The sentiment of “not having a choice” with maintaining and caring for the household's sanitation needs was common. One participant said that she would decide to divide tasks among her family “Only if I'm not able to do the work.” (CI05, Over 40) and when asked about water-related decision-making noted that “There is no need for decision-making” because she must do all the work in the family anyway. Another participant supported this sentiment, saying that while she could theoretically request her husband to purchase items like soap or cleaning liquid for the sanitation facility, she does not do so because maintaining the sanitation environment is her responsibility.

Participants reported having decision-making power over small expenses but noted that larger expenditures required more household discussion. Some women had been involved in decisions related to large expenses (e.g., construction or repairs of a sanitation facility), while all women were involved in decisions related to smaller expenses (e.g., buying cleaning agents and soap). Many believed financial management to be better handled by women. One participant believed this because more women are getting educated, and “[women] look after their family budget at home, about how to spend. So, because of that they can look after” (CI04, Unmarried). There was variation in women's experiences with major sanitation-related investments and purchases. Some participants believed that larger financial decisions should be made jointly. One participant stated, “I can [be involved with decisions about big sanitation-related purchases] with the help of my husband only. All decisions should take place with men around” (CI05, Over 40). Another participant agreed, saying “We decide such things [high budget decisions] together” (CI10, Married)

Men were either described as the final decision-maker in the family or as a supporter of women's household sanitation decisions. Some women believed that the male head of the family should seek women's views when making these decisions, but ultimately, they found it acceptable for male heads to make the final decisions for the household. One participant believed it would be “good” if her husband made important sanitation decisions without asking her as they normally align with her decisions. Another specifically described that her husband could make the correct sanitation decisions and mentioned “when I can myself make those decisions, they can too” (CI09, Married). While many participants generally believed that male partners making important sanitation-related decisions without asking their wives is completely unacceptable: “Only they [women] know everything, about where the waste is thrown, water need[ed]” (CI11, Over 40), an alternative idea was that few participants appreciated their male partners taking care of the household's sanitation needs on their own accord. An overarching idea was that men must consider women's views when making household sanitation decisions as participants believed women are more aware of household sanitation needs and the environment.

3.2.2. Community decision-making

Despite their comfort with many household-level decisions, participants voiced more challenges with feeling comfortable openly sharing their opinions or having their decisions accepted at the community level. Several participants noted that, while women have opportunities to voice their opinions, community members and organizations may not accept or act upon them—“But they [men] don't agree with our opinions. They tell and ask us to accept that only. If we tell, they don't accept it…they say that they [men] have spoken and they [men] have done it.” (CI01, Married). There was, however, consensus that women must be involved in the community's sanitation and water decisions. Participants were more aware of community-level sanitation matters but felt it would be beneficial to have mutual decision-making between women and men (with whoever is more capable of having the final say).

Despite participants believing that women are more aware and proactive about sanitation issues in the community, they believed that their role in decision-making remains limited. Participants mentioned that women do more sanitation work for their community and primarily take care of their family's sanitation needs, especially because men do not have time to stay involved due to their work responsibilities. Another participant noted, “Women take part more than men. Because when it comes to sanitation, women only open their mouths.” (CI11, Over 40). Overall, many believed that women know more about community sanitation, and it is their duty to be involved in sanitation but noted that they have fewer opportunities than men to influence their community's sanitation-related decisions, limiting their role in community decision-making. All participants completely agreed that women should be more involved in making these decisions and that their community leaders and organizations must seek women's opinions to fully understand the local sanitation environment.

Participants were very comfortable being involved in decision-making at community sanitation meetings that comprised only women. Generally, participants indicated feeling completely comfortable expressing their sanitation-related opinions when among other women, even if there were women who disagreed with their views during discussions. Participants' community-level decision-making was observed in the construction of sanitation-related infrastructure or addressing other community issues such as garbage disposal, clogged drains, or street maintenance. The overall perception was that “women-only” groups provided a space where women could listen and share their opinions with no restrictions on topics that were covered.

In contrast, there were accounts that men's presence in these community meetings created an environment that stifled some women's open expression about sanitation, especially during disagreements or when contrasting viewpoints were presented. As one participant described, “P: If men were not present then women would be able to participate. I: Why is that? P: Men ask why the women are interfering when they are talking” (CI05, Over 40). She noted, “I won't talk at all,” when asked if she would be able to express her opinions in a meeting where men and women are present. It was more challenging when men led these forums or meetings, especially when topics related to constructing sanitation facilities or personal hygiene were discussed. It was much easier to have conversations surrounding “simpler” topics such as maintaining the drainage, garbage, or local streets. One participant noted, “I don't think men will appreciate women talking. So, it is better to gauge the group and then talk. Whereas, if the meeting is conducted exclusively by women, then she can freely discuss her issues” (CI10, Married). In voicing her opinion, one participant asked “How can we talk about such [general sanitation] issues in the presence of a man? It is little difficult to speak but more convenient when men and women are present” (CI11, Over 40). A minority of participants agreed that men should be making sanitation-related decisions for their community, and one participant mentioned that while men can solely make decisions for the community, joint decision-making is more prevalent in the household. In contrast, another participant mentioned that men in her community encouraged women to share their sanitation-related opinions: “Be it menstrual problems or sanitation, anything, be it ladies or girls, they ask us to openly tell them. Even if only men are present, they encourage us to speak, so we can tell. It's not wrong. We can tell all this because a lot of diseases are spreading because of improper sanitation” (CI04, Unmarried).

3.3. Leadership

Few participants reported holding formal or informal leadership positions for sanitation initiatives in their community. Projects led by women included advocating for toilet construction, petitioning for sanitation-related changes in their community, and organizing sanitation education workshops. One participant, who identified herself as an informal leader, mentioned that a lack of response from the local sanitation office resulted in her leading a group of women organizing a community cleaning initiative. Participants also reported that community members listened to their opinions and that they informally led meetings about keeping toilets clean, maintaining sanitation facilities, and discussing hygiene concerns among small groups of 10 people or fewer. Many participants, however, said that they were not leaders of any community-based sanitation organizations and/or that they did not wish to hold leadership positions. Reasons for this sentiment included: no time due to major responsibilities at home, perceptions of the education level or knowledge required of a leader, lack of connection with the local community, lack of acceptance of women as leaders in the community, the perception that others were more capable, and a simple lack of interest.

All participants believed in women's capacity as leaders for sanitation initiatives. They expressed that they, alongside other women in the community, would support female sanitation organization leaders completely. Some participants noted that women's overall expertise in household sanitation and hygiene made them more suitable leaders. Participants mentioned that women can effectively lead, confidently make decisions, and efficiently address the community's needs, particularly women's sanitation and hygiene concerns. One participant noted “If women are there, I'll completely trust” (CI06, Married).

Participants expressed a range of opinions about family and local community members' support for women's leadership. Most participants reported that both male and female family members would support them completely if they took on a leadership position. Only one participant mentioned that she did not know if female family members would offer her support to lead a sanitation initiative and that her husband would not encourage her to take up a leading role. Some women also felt that the community was completely accepting and encouraging of women's leadership for sanitation initiatives, as long as the woman was competent. A participant explained, “They [community members] accept them completely. If a leader stands, they take them. If they think she's right.” (CI11, Over 40). This participant emphasized that it was most important to have someone effective, regardless of gender “if they're doing something good for us, it doesn't matter if it is a man or a woman” (CI11, Over 40).

At the same time, some participants indicated that community members, particularly men, do not fully accept women's leadership. One participant attempted to lead a sanitation group through her church to clean the community and spread sanitation education. However, the community undermined the participant's decision-making power and did not accept her leadership. She explained “We were a small group who tried to clean and create awareness through our church. We were about 6–7 people, but people frowned upon our work so we stopped.” (CI05, Over 40). Other participants described how men were particularly unsupportive and desired to be “the first” leaders. Additionally, some participants explained that men believe only their opinions to be true and felt they could not share issues with women. One participant noted, “[men] can't accept my being in authority. I'll say something they'll say another thing, which will lead to disagreements. “Who is she to tell us off?” is the type of mentality they have.” (CI05, Over 40).

There was variation in participants' perceptions of whether local leaders and authority figures would support women's leadership in sanitation organizations. While some noted that leaders are completely accepting, others believed they would only be partially accepting or not at all. A prevalent sentiment was that if local leaders knew the woman's background and qualifications for the leadership position, they completely accepted her leadership. As one participant reported, “If they don't know who it is, what they'll do, getting their support is difficult. So, similarly for this also, complete support won't be there, they will partially support”. Similarly, a participant mentioned that local leaders would not accept her as a leader because she is new in the area and has not spoken to anyone in the community.

Many participants indicated that they did not believe that men alone should lead sanitation initiatives, explaining that men cannot take care of the house better than women, do not care about sanitation or hygiene, do not have time to lead such initiatives due to their work, and that woman cannot talk openly to male leaders about certain issues. One participant shared her personal experience of continuously speaking with male councilors but never feeling heard by them. Participants also supported the idea of both women and men being leaders together. They expressed that both women and men are equal, and that men's and women's opinions can be heard if both are leaders. A participant added “…when there is a situation with just male leaders, they don't care, we [women] won't feel comfortable.. I say this out of personal experience. But when there are male as well as female leaders, work definitely gets done....” (CI05, Over 40).

3.4. Collective action

Participants agreed that collective action by the community is the best way to address a sanitation problem. Many mentioned experiences where women successfully collaborated to improve their communities' existing sanitation environment and organized sanitation and hygiene education initiatives. Some participants perceived strong solidarity among women in their community; others, however, doubted whether women in their community would work together if a common sanitation issue presented itself and persisted.

Participants were described as more proactive in voicing their sanitation-related opinions and acting on sanitation improvement in the community compared to men. An example of women's sanitation-related collective action was a women's group that advocated for free public toilets and bathing facilities for women. The group was inspired by observing how women coming from other towns, especially for funerals, faced difficulty locating toilets. Participants in the community who previously practiced open defecation also worked together to advocate for household toilets: “We used to go in the open. After that slowly everyone started building it [a toilet]. For those who don't have [a toilet], we spoke with them and formed a group of 5.5 of us joined…and told them [the local sanitation office] that we don't have a toilet. Sanitation should be clean we told, and we asked we need one for the house.” (CI03, Over 40). Another women-led initiative was redeveloping existing public toilets in the neighborhood. When asked about collective sanitation efforts, women reported having acted collectively to address other issues, including drainage, garbage disposal, and water shortages around the community.

Participants described similar barriers to engaging in collective action as they did to engaging in leadership roles. Participants voiced a lack of time, being new in the community, work responsibilities, household responsibilities, and lack of acceptance as reasons for not being personally involved in sanitation-related community groups. Time was one of the most common limitations: “I don't know about others, I work from morning to evening outside, so I don't know about the situation now. Plus, I've been on leave for the past one month.” (CI05, Over 40). Another participant added that her role as the sole earner and caretaker in the household left no time for joining sanitation groups. A younger female student mentioned, “The reason is for all these years, I was studying and then working at a job, so I have no time and I didn't think about it also.” (CI04, Unmarried). Another participant, who was newly married and recently moved to the neighborhood, lacked familiarity with local sanitation-related community groups and community members: “I don't know... how to get membership … I just came here. So, I don't have that much familiarity with the area or know that many people too” (CI06, Unmarried).

While a rare perception, some participants believed that women may find it difficult to work together; resolving a sanitation issue together would be challenging because “whenever ladies get together, they end up arguing” (CI10, Married). When discussing whether participants were open to providing resources such as money and energy for helping develop sanitation facilities, distrust in the motivation of those who collect these funds was expressed by some. “Depends on the people...some people work just for the cause, but some others might launder money” (CI05, Over 40). Uncertainty on whether women would be willing to give their time and money for sanitation-related projects was expressed at times while others stated that those who cannot afford to contribute money would invest their time in these initiatives instead.

Some participants described facing resistance when interacting with authority figures, government officials, and the local sanitation office to address sanitation problems, but reported having success working with men in the community. For example, the local sanitation office did not take any steps when women expressed concerns about the “messy” community environment. Additionally, another participant expressed that “Male leaders don't care much about hygiene and sanitation. We tried talking to the male councilors a lot; they never listened to us” (CI05, Over 40). After the local government failed to organize cleaning efforts, women collectively paid for cleaning common areas in the neighborhood. On the other hand, most participants expressed feeling comfortable working with male community members for sanitation initiatives. While women's groups often collaborated to address sanitation-related issues, men and women in the community also jointly worked together for sanitation improvement. Collectively, men and women have worked together to solve common sanitation issues—such as building a toilet for the community, collecting funds for sanitation infrastructure, acquiring land/location for related issues, and sanitation education.

4. Discussion

This qualitative analysis aimed to explore the subdomains of women's sanitation-related agency—decision-making, leadership, collective action, and freedom of movement—in urban areas of Tiruchirappalli, India. Our results demonstrated how trust in women's competency, belief in their ability to work together, and expectations of women's duties influenced their leadership, collective action, and aspects of their household and community-level decision-making. While participants showed strong support for women's leadership and decision-making abilities for local sanitation initiatives, there were many day-to-day barriers to exercising their agency in their lived experiences. Participants expressed a lack of confidence, interest, or time for involvement in sanitation-related initiatives. Support from male partners and family members to pursue leadership roles and attend sanitation meetings was common among those interviewed. However, some women expressed discomfort with community-level decision-making amongst other male community members. Furthermore, our findings emphasized the value of supportive leadership and sanitation governance for women's involvement in sanitation initiatives or discussions; we found women expressing how challenges faced with local governance and community norms affected their collective action, leadership, and freedom of movement.

The results of our study provide insight into potential entry points for sanitation programming to bring about gender transformative change. MacArthur et al. (2022) describe how gender transformative approaches need to address deeply rooted systemic inequalities within the relevant sector sector. According to MacArthur et al. (2022) gender transformative approaches “aim to reshape gender dynamics by redistributing resources, expectations and responsibilities between women, men, and non-binary gender identities, often focusing on norms, power, and collective action.” The results from this study introduce different areas of focus for gender transformative change in sanitation among the study population. The interaction between women's individual and community-level agency with the systems within local sanitation governing bodies emphasizes an entry point for higher-level structural change. Overseeing and restricting the bodies that process community requests and oversee community engagement can ultimately feed into better support among women to collectively act or pursue sanitation leadership roles. Our results and interpreted themes in the discussion align with MacArthur et al.'s (2022) third principle i.e., “Grounded in strategic gender interests” as they unpack causes related to challenges to women's sanitation-related agency. These can be utilized to strengthen sanitation interventions at the individual, household, community, and organizational levels, or prevent sanitation interventions from contributing to the existing challenges women face with agency. Similarly, across the WASH sector, it is important to explore agency in relation to water and hygiene and integrate gender transformative approaches in their respective programming.

4.1. Trust and belief in women's competency

Participants deemed women's sanitation-related leadership completely trustworthy, which is consistent with existing research. Specifically, research in rural Sri Lanka found that community members place strong trust in women leaders for water and sanitation projects in their villages (Aladuwaka and Momsen, 2010). In our findings, trust in women's leadership facilitated some participants' engagement in sanitation initiatives and positively influenced collective action. Similarly, research in rural Kenya with household heads found that high trust in community leaders influenced collective engagement and participation in WASH initiatives (Abu et al., 2019). A study in Indonesia among women who engage in WASH-related economic activities, including as business owners, mobilizers, and public sector employees, highlighted how having a trusted network of supportive women in one's local area could contribute to women's empowerment (Indarti et al., 2019).

Participants expressed more trust and faith in women's financial management for sanitation organizations than in men's, supported by their trust in women managing finances and working together to make decisions for the community's sanitation environment, which is a sentiment noted in research elsewhere as well. Research in northern Kenya that explored women's role in water management and conflict resolution, demonstrated how not only women but the larger community placed more trust in financial decisions and resource utilization when women were involved (Yerian et al., 2014). In our research, participants who had been leaders of formal and informal sanitation groups described successful initiatives that brought forth sanitation improvement in their community. Recognizing women's competency in addressing sanitation issues could increase the community's trust in women's capabilities and provide successful examples of women-led sanitation initiatives. Therefore, maintaining and strengthening trust in female community members, and highlighting women-led groups' achievements in the sanitation space should be prioritized in WASH programming.

4.2. Expectations of women's duties

This study, consistent with many others, found that women are often responsible for sanitation-related maintenance and cleanliness in the household. Because women do the majority of sanitation upkeep in the household, they feel that they are more capable of making decisions on household sanitation-related issues than community-related issues. However, the gendered roles and responsibilities that provide women with this expertise also serve as barriers, with many women having neither the time nor the energy to participate in community-level decision-making or sanitation initiatives, or to pursue leadership roles. Some women may prefer not to have sole responsibility for these household sanitation decisions but feel restricted due to these gendered responsibilities. Similarly, a study in Odisha, India demonstrated that prevailing socio-cultural practices and a lack of exposure to the community outside the household limited women's sanitation-related decision-making power (Routray et al., 2017). Our findings showed freedom of movement for sanitation-related purposes was restricted, most commonly among the newly married, a finding consistent with a study in Odisha, India where family members did not give recently married women permission to attend sanitation-related focus group discussions (Caruso et al., 2017).

Despite many participants supporting women's ability to make sanitation-related decisions, as found in other studies, some participants in this research lacked the self-confidence to contribute to sanitation-related discussions in their community, and organizations also failed to recognize women's expertise. Research has highlighted the impact of gendered social norms on women's perceptions of their abilities to lead sanitation initiatives (Young, 2005; Jalali, 2021). While women's expertise in sanitation was recognized by this study's participants and other research, our findings showed participants sought joint decision-making for large sanitation decisions and financial decisions, whereas they were more comfortable making smaller decisions alone, such as fixing the tiles/lights or buying cleaning agents. Existing research also has found women have less access to financial resources and are often financially dependent on their husbands or male family members to make larger decisions (Routray et al., 2017; Jalali, 2021). In addition, Routray et al. call attention to NGOs that rarely seek female household members' participation or opinions for latrine construction projects and instead directly approach male household members (Routray et al., 2017). Equitable approaches are required to ensure that women's opinions on effective methods to increase female sanitation-related involvement are considered while ensuring that interventions neither further marginalize women nor add burden to their existing responsibilities.

4.3. Men's support and role in gender-sensitive WASH

In contrast to other studies, our findings show that male family members were supportive of women's involvement in sanitation groups and did not limit women's sanitation-related freedom of movement. Research in urban north-Indian cities found male family members restrict women's sanitation-related freedom of movement and decision-making (Singh, 2013; Kulkarni et al., 2017). Despite male family members' support, participants in our study found it difficult to express their opinions comfortably in public settings where male community members were present, especially when discussing personal hygiene and sanitation-related experiences; some of this difficulty was attributed to past experiences where women's concerns were not respectfully received in community spaces. Research in central Vietnam among men and women recognized a gap in “solidarity within and between women and men” and “the extent to which women”s perspectives were listened to at the community level' for WASH decisions (Leahy et al., 2017). Leahy et al. (2017) emphasized a need to shift men's views regarding the value of women's community-level participation. There is a need for gender-sensitive WASH programming to focus not only on women but also to work with men to transform the power dynamics and social norms that determine women's sanitation experiences. Our findings are especially supportive of Leahy et al.'s (2017) push for interventions that allow men and women in the community to discuss their opinions both separately and together, which could help reduce discomfort without completely segregating men and women during sanitation discussions.

4.4. Leadership's support and sanitation-related governance

Our findings align with existing research, which shows that local leadership, sanitation programming, and the community's sanitation expectations limited women's agency. In Indonesia, research found that local leaders and community members criticized or were confused by women's engagement in sanitation-related initiatives (Indarti et al., 2019). Our results indicated that local leaders were more likely to support women's leadership when the women were well-known and had clear qualifications, suggesting that a woman's social capital may influence the support or acceptance she receives as a sanitation leader. We also found that women were discouraged by previous negative experiences they faced with local leadership or organizations; some expressed frustration with government bodies that failed to address issues surrounding dirty streets or spoke about how high government officials only adequately address women's complaints if the women have high positions in organizations. Similarly, in their research in northern India, Scott et al. (2017) showed how “fragmented and opaque administrative accountability” created barriers for women to gain access to those leadership positions. The present study supports calls to engage authority figures, leaders, and officials when seeking to increase women's agency and involvement with sanitation-related issues (Leahy et al., 2017; Scott et al., 2017). Women's roles are integral in encouraging equity in sanitation initiatives and leadership internally recognizing women's vital role in sanitation-related decision-making (Leahy et al., 2017).

4.5. Strengths and limitations

The cognitive interviews allowed women to share their perspectives and experiences in response to the agency-related survey questions. As the cognitive interviews were primarily aimed to validate the MUSE survey tool, the structure, and purpose of the cognitive interview limited probing opportunities for specific responses. Open-ended questions might have elicited more detail. Still, the cognitive interviews elicited details about women's perceptions and experiences related to women's sanitation-related agency, including factors affecting leadership, decision-making, freedom of movement, and collective action at the individual, household, and community levels. While men's perspectives were not included in this analysis, the women participants provided their perceptions on whether men were supportive of women's sanitation-related agency and at times, spoke about men's role in community and household-level WASH. Future research could explore men's perspectives and support for women's agency with sanitation. Additionally, there is scope for future research to explore the sub-domains of agency in a rural setting as factors such as access to resources, land terrain, cultural norms and social structure could lead to different results. There was also variability in some participants' perception of sanitation with references made to garbage and sewage, instead of solely toilet use (i.e., the definition of sanitation used for this research). However, participants were not directed to speak only about toilet use to prevent bias in the interviews and clearly capture their honest perspectives. This was noted in the results section to ensure transparent reporting of the participants' sanitation experiences.

5. Conclusion

Women's agency is central to women's empowerment. This qualitative analysis highlights the value of strong trust among women and confidence in their ability to make important sanitation-related decisions at all levels of society in urban Tiruchirappalli. Programs must recognize women's expertise in large or small sanitation-related issues. Highlighting successes among both formal and informal women-led sanitation initiatives may encourage women to participate in similar initiatives. Communities should have physical and social environments where women's sanitation-related opinions can be comfortably shared and governance that respects and encourages women's engagement in addressing sanitation issues. There is a need to engage men when addressing gender-based sanitation-related restrictions. Future efforts in WASH programs and research should address and explore women's agency in conjunction with other empowerment domains, (i.e., resources and institutional structures).

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed in this article will be posted to a public data repository upon publication of the research. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to BC, YmNhcnVzb0BlbW9yeS5lZHU=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Emory University Institutional Review Board (USA; IRB 00110271) and Azim Premji University Institutional Review Board (India; Ref. No. 2019/SOD/Faculty/5.1). The participants provided verbal consent to participate and be recorded in this study.

Author contributions

RD: formal analysis, interpretation, data curation, validation, writing—original edit, writing—review and editing, and final approval. MP and AC: investigation, methodology, data curation, project administration, validation, writing—review and editing, and final approval. VR: investigation, data curation, project administration, validation, writing—review and editing, and final approval. SA: validation, writing—review and editing, and final approval. SS: conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing, and final approval. BC: conceptualization, formal analysis, interpretation, methodology, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing, and final approval. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation OPP1191625. Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the engagement and cooperation of the 11 women from Tiruchirappalli, India who participated in the cognitive interviews. We also appreciate the work and efforts of the local data collection team.

Conflict of interest

VR and SA were employed by Civic Fulcrum.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frwa.2023.1048772/full#supplementary-material

References

Abu, T. Z., Bisung, E., and Elliott, S. J. (2019). What if your husband doesn't feel the pressure? An exploration of women's involvement in WaSH decision making in Nyanchwa, Kenya. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 1763. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101763

Aladuwaka, S., and Momsen, J. (2010). Sustainable development, water resources management and women's empowerment: the Wanaraniya Water Project in Sri Lanka. Gender Develop. 18:1, 43–58. doi: 10.1080/13552071003600026

Ashraf, S., Kuang, J., Das, U., Shpenev, A., Thulin, E., Bicchieri, C., et al. (2022). Social beliefs and women's role in sanitation decision making in Bihar, India: an exploratory mixed method study. PLoS ONE 17, e0262643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262643

Beatty, P. C., and Willis, G. B. (2007). Research synthesis: the practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opin. Q. 71, 287–311. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfm006

Carrard, N., MacArthur, J., Leahy, C., Soeters, S., and Willetts, J. (2022). The water, sanitation and hygiene gender equality measure (WASH-GEM): conceptual foundations and domains of change. Women's Stud. Int. Forum. 91. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102563

Caruso, B. A., Clasen, T., Yount, K. M., Cooper, H., Hadley, C., Haardörfer, R., et al. (2017). Assessing women's negative sanitation experiences and concerns: the development of a novel sanitation insecurity measure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 14, 755. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070755

Caruso, B. A., Conrad, A., Patrick, M., Owens, A., Kviten, K., Zarella, O., et al. (2022a). Water, sanitation, and women's empowerment: a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLOS Water 1, e0000026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pwat.0000026

Caruso, B. A., Cooper, H. L. F., Haardörfer, R., Yount, K. M., Routray, P., Torondel, B., et al. (2018). The association between women's sanitation experiences and mental health: a cross-sectional study in Rural, Odisha India. SSM Popul Health. 5, 257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.06.005

Caruso, B. A., Sclar, G. D., Routray, P., Nagel, C. L., Majorin, F., Sola, S., et al. (2022b). Effect of a low-cost, behaviour-change intervention on latrine use and safe disposal of child faeces in rural Odisha, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Planetary Health. 6, e110–e121. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00324-7

Fisher, N., Cavill, S., and Reed, B. (2017). Mainstreaming gender in the WASH sector: dilution or distillation? Gender Develop. 25.2, 185–204. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2017.1331541

Gammage, S., Kabeer, N., and van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. (2016). Voice and Agency: Where Are We Now?. Fem. Econ. 22, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2015.1101308

Graham, J., Hirai, M., and Kim, S. (2016). An analysis of water collection labor among women and children in 24 Sub-Saharan African countries. PLoS ONE 11, e0155981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155981

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., and Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781483384436

Hennink, M., Hutter, I., and Bailey, A. (2020). Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Limited.

Hirve, S., Lele, P., Sundaram, N., Chavan, U., Weiss, M., Steinmann, P., et al. (2015). Psychosocial stress associated with sanitation practices: experiences of women in a rural community in India. J. Water Sanitation Hygiene Develop. 5, 115–126. doi: 10.2166/washdev.2014.110

Hulland, K. R., Chase, R. P., Caruso, B. A., Swain, R., Biswal, B., Sahoo, K. C., et al. (2015). Sanitation, stress, and life stage: a systematic data collection study among women in Odisha, India. PLoS ONE 10, e0141883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141883

Indarti, N., Rostiani, R., Megaw, T., and Willetts, J. (2019). Women's involvement in economic opportunities in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) in Indonesia: examining personal experiences and potential for empowerment. Develop. Stud. Res. 6, 76–91. doi: 10.1080/21665095.2019.1604149

Jalali, R. (2021). The role of water, sanitation, hygiene, and gender norms on women's health: a conceptual framework. Gendered Perspect. Int. Develop. 1, 21–44. doi: 10.1353/gpi.2021.0001

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women's empowerment. Dev. Change 30, 435–464.

Khanna, T., and Das, M. (2016). Why gender matters in the solution towards safe sanitation? Reflections from rural India. Glob. Public Health. 11, 1185–1201. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1062905

Kulkarni, S., O'Reilly, K., and Bhat, S. (2017). No relief: lived experiences of inadequate sanitation access of poor urban women in India. Gender Develop. 25, 167–183. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2017.1331531

Leahy, C., Winterford, K., Nghiem, T., Kelleher, J., Leong, L., Willetts, W., et al. (2017). Transforming gender relations through water, sanitation, and hygiene programming and monitoring in Vietnam. Gender Develop. 25, 283–301. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2017.1331530

MacArthur, J., Carrard, N., Davila, F., Grant, M., Megaw, T., Willetts, J., et al. (2022). Gender-transformative approaches in international development: a brief history and five uniting principles. Womens Stud. Int. Forum. 95, 102635. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102635

Maxwell, J. A. (2010). Using numbers in qualitative research. Qualitat. Inquiry. 16, 475–82. doi: 10.1177/1077800410364740

Neale, J., Miller, P., and West, R. (2014). Reporting quantitative information in qualitative research: guidance for authors and reviewers. Addiction 109, 175–176. doi: 10.1111/add.12408

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. (2021). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India, Volume I. Mumbai: IIPS.

O'Reilly, K. (2010). Combining sanitation and women's participation in water supply: an example from Rajasthan. Dev. Pract. 20, 45–56. doi: 10.1080/09614520903436976

Routray, P., Torondel, B., Clasen, T., and Schmidt, W. P. (2017). Women's role in sanitation decision making in rural coastal Odisha, India. PLoS ONE 12, e0178042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178042

Sahoo, K. C., Hulland, K. R., Caruso, B. A., Swain, R., Freeman, M. C., Panigrahi, P., et al. (2015). Sanitation-related psychosocial stress: a grounded theory study of women across the life-course in Odisha, India. Soc. Sci. Med. 139, 80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.031

Saleem, M., Burdett, T., and Heaslip, V. (2019). Health and social impacts of open defecation on women: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 19, 158. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6423-z

SBM (2021). About Us|Swachh Bharat Mission—Gramin, Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation. Available online at: https://swachhbharatmission.gov.in/SBMCMS/about-us.htm (accessed April 17, 2022).

Scott, K., George, A. S., Harvey, S. A., Mondal, S., Patel, G., Ved, R., et al. (2017). Beyond form and functioning: understanding how contextual factors influence village health committees in northern India. PLoS ONE 12, e0182982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182982

Singh, N. (2013). Translating human right to water and sanitation into reality: a practical framework for analysis. Water Policy 15, 943–960. doi: 10.2166/wp.2013.020

Sinharoy, S. S., Conrad, A., Patrick, M., McManus, S., and Caruso, B. A. (2022). Protocol for development and validation of instruments to measure women's empowerment in urban sanitation across countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa: the Agency, Resources and Institutional Structures for Sanitation-related Empowerment (ARISE) scales. BMJ Open 12, e053104. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053104

Sinharoy, S. S., McManus, S., Conrad, A., Patrick, M., and Caruso, B. A. (2023). The agency, resources, and institutional structures for sanitation-related empowerment (ARISE) scales: development and validation of measures of women's empowerment in urban sanitation for low- and middle-income countries. World Develop. 164, 106183. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106183

Sorenson, S. B., Morssink, C., and Abril Campos, P. (2011). Safe access to safe water in low income countries: water fetching in current times. Available online at: https://repository.upenn.edu/spp_papers/166

UN (2015). Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication

van Eerdewijk, A., Wong, F., Vaast, C., Newton, J., Tyszler, M., Pennington, A., et al. (2017). A Conceptual Model of Women and Girls' Empowerment. Available online at: https://www.gatesgenderequalitytoolbox.org/wp-content/uploads/Conceptual-Model-~of-Empowerment-Final.pdf

VERBI Software. (2021). MAXQDA 2022 [computer software]. Berlin: VERBI Software. Available online at: maxqda.com

WHO and UNICEF (2021). Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000–2020: five years into the SDGs. Licence: CC BY NC-SA 3, 0. IGO.

Yerian, S., Hennink, M., Greene, L. E., Kiptugen, D., Buri, J., Freeman, M. C., et al. (2014). The role of women in water management and conflict resolution in Marsabit, Kenya. Environ. Manage. 54, 1320–1330. doi: 10.1007/s00267-014-0356-1

Keywords: sanitation and hygiene (WASH), gender, agency, India, Tiruchirappalli, agency–structure

Citation: Doma R, Patrick M, Conrad A, Ramanarayanan V, Arun S, Sinharoy SS and Caruso BA (2023) An exploration of sanitation-related decision-making, leadership, collective action, and freedom of movement among women in urban Tiruchirappalli, India. Front. Water 5:1048772. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2023.1048772

Received: 20 September 2022; Accepted: 06 March 2023;

Published: 28 March 2023.

Edited by:

Jane Wilbur, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Naomi Carrard, University of Technology Sydney, AustraliaSue Cavill, Berkshire, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 Doma, Patrick, Conrad, Ramanarayanan, Arun, Sinharoy and Caruso. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bethany A. Caruso, YmNhcnVzb0BlbW9yeS5lZHU=

Rinchen Doma

Rinchen Doma Madeleine Patrick

Madeleine Patrick Amelia Conrad2

Amelia Conrad2 Bethany A. Caruso

Bethany A. Caruso