- Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Georgia Health Policy Center, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

Background: Adolescents recovering from substance use face developmentally specific challenges requiring tailored supports. Recovery capital (RC), defined as internal and external resources sustaining recovery, offers a framework to address these needs. Guided by the Recovery Capital for Adolescents Model (RCAM), this study explored how adolescents and caregivers experienced RC and investigated perceptions of the Recovery Clubhouse as a context for building and sustaining these resources.

Methods: Matched semi-structured interviews were conducted with seven adolescent–caregiver pairs. Adolescents aged 16–18 participated, using guides tailored to age and role. Caregivers completed interviews in either English or Spanish. Interviews were thematically analyzed using RCAM as the guiding framework.

Results: Adolescents and caregivers identified multiple internal and external resources as essential to recovery, often framed in relation to Recovery Clubhouse involvement. Within community recovery capital (CRC), both groups emphasized the value of enjoyable, substance-free activities and creative expression offered through the Clubhouse. In human recovery capital (HRC), adolescents described how intrinsic motivation developed over time, replacing initial external pressures such as court mandates or parental requirements, and noted that Clubhouse participation supported this process. Financial recovery capital (FRC) was also influential: caregivers valued Clubhouse-provided resources for easing financial strain, while adolescents saw employment as a motivator and pathway to independence and long-term goals. Social recovery capital (SRC) revealed the most divergence: adolescents emphasized relationships with Clubhouse staff and friendships outside the program, including peers who used substances. Caregivers viewed these external friendships as risks and instead highlighted the protective role of the Clubhouse's peer network. Interconnections across RC domains were evident, with gains in one area reinforcing others (e.g., CRC participation supporting HRC via coping skills). Additional themes included the importance of family involvement and language-accessible services.

Discussion: The RCAM framework provided a comprehensive lens for understanding recovery resources perceived as valuable by adolescents and caregivers. Findings suggest recovery supports should be developmentally tailored, incorporating engaging activities, opportunities for economic empowerment, staff relationships, and culturally responsive family programming. Recovery Clubhouses were perceived not only as access points for these resources, but also as environments where RC was built and sustained.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Of the 2.9 million adolescents in need of specialized substance use disorder (SUD) care, only 38.9% receive treatment (1). Even among those who do access services, many continue to struggle with substance use, highlighting the need for appropriate recovery support services (2–5). Recovery is a dynamic process shaped by the interplay of personal, social, financial, and community resources that are collectively termed recovery capital (RC) (6, 7). While RC has advanced adult recovery paradigms, its application to adolescents remains underexplored despite their distinct developmental needs, including identity formation, peer influence, and socioeconomic dependence on caregivers (8, 9). Identifying which resources adolescents recognize and prioritize is essential to designing effective, developmentally appropriate strategies that support recovery.

1.2 RCAM as the theoretical framework

To address these adolescent-specific needs, the Recovery Capital for Adolescents Model (RCAM) was developed as a strengths-based, ecological framework designed to examine the resources that facilitate recovery across four domains: human, social, financial, and community (8). Each domain is tailored to the developmental context of adolescence. Human recovery capital (HRC) includes internal assets such as coping skills, self-esteem, emotional regulation, spiritual beliefs, and school engagement. Social recovery capital (SRC) refers to the relationships and connections formed by adolescents, enabling them to bond and engage (e.g., peer relationships and family dynamics). Financial recovery capital (FRC) pertains to economic stability, acknowledging the impact of caregiver income, education, and access to health insurance on adolescents' well-being while also considering adolescents' own financial resources and opportunities. Community recovery capital (CRC) refers to the availability and accessibility of recovery resources within an adolescent's environment. RCAM emphasizes the multidimensional and interconnected nature of recovery, suggesting that growth in one domain can enhance others. While previous research on RC has been conducted in specific contexts such as Recovery High Schools (10–12) and Alternative Peer Groups (10), continued exploration across diverse recovery programs can provide deeper insight into the resources that support adolescent recovery.

1.3 The Georgia recovery support clubhouse program

Addressing this gap, the present study draws on the Georgia Recovery Support Clubhouse program (hereafter referred to as the Recovery Clubhouse) to explore how RC is understood and supported in this setting. The Recovery Clubhouse supports adolescents ages 13–17 and their families as they work to improve health and wellness while decreasing or abstaining from alcohol and substance use. It provides a year-round, no-cost environment that not only supports adolescents in reducing substance use but also addresses the broader environmental and developmental factors that influence recovery.

Federally funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and managed by the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, Office of Addictive Diseases (DBHDD, OAD), the program operates at eight sites across rural and urban Georgia, serving approximately 200–300 youth annually (30–60 per clubhouse). Daily operations are overseen by community service providers, including Community Service Boards, which function as Georgia's public safety-net behavioral health providers and ensure the program remains accessible and responsive to local needs. Clubhouses typically operate 30 hours per week during the academic year and 40 hours per week in the summer, offering non-traditional hours after school and on weekends. Programming includes tutoring and academic support, nutrition education, vocational training, résumé building, interview preparation, mentoring, family engagement opportunities, and community-based outings that foster resilience and connection.

The program is guided by six objectives: (1) decrease substance use; (2) decrease involvement with the Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ); (3) decrease behavioral problems; (4) increase positive social functioning; (5) increase school attendance and performance; and (6) improve family involvement and relationships.

1.4 Current study

This study had two aims: to apply the RCAM framework to investigate how adolescents and their caregivers experience and perceive RC, and to explore the perceived role of Recovery Clubhouses in building and sustaining these resources. As the study was embedded within an ongoing programmatic evaluation, interview questions also invited youth and caregivers to reflect on their recovery experiences in relation to clubhouse participation. Consequently, participants often situated their descriptions of RC within this setting. Together, these two aims serve the broader goal of advancing understanding of adolescent RC and highlighting youth and caregiver perspectives on Recovery Clubhouses to guide the refinement and development of more effective adolescent recovery strategies.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and data collection

Matched semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted between August 2023 through April 2024 with two participant groups: currently enrolled adolescents and their caregivers.

Inclusion criteria for adolescents included: 1) enrollment in the Recovery Clubhouse for at least 3 months and no more than 12 months, 2) regular participation (defined as participating in clubhouse activities at least once a month), 3) completion of at least two program-specific behavioral health assessments, and 4) the establishment of programmatic goals. A requirement of the Recovery Clubhouse is that youth set three goals in collaboration with a counselor, with at least one goal directly addressing substance use. These goals are youth-defined and reflect how adolescents define short-and-long term success and highlight what they consider important in their recovery. Examples of youth-defined goals include “stop using,” “reduce use,” “move forward in life after probation,” and “don't get angry and throw things.” Caregivers were eligible to participate if their adolescent met these criteria. Two interview guides were developed — one for adolescents (available only in English) and one for caregivers (available in both English and Spanish). While the guides were customized for each group using age-appropriate language for adolescents, they shared a similar structure and covered comparable key topics. Interview questions for adolescents focused on their goals, recovery needs, and relationships, while caregivers were asked about their support role and changes in their relationship with their adolescent. For example, adolescents were asked, “What is essential for you to reach your goals and be supported in your recovery?”. Caregivers were asked, “What is essential for you to support your youth in their recovery journey?”

Recruitment involved two approaches: first, Clubhouse staff distributed an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved message to members and provided the research team with contact information of currently enrolled members. Following this message, the research team directly contacted families, obtaining parental permission for adolescents under 18 years old. Informed consent or assent was collected from all participants, with Spanish-speaking caregivers receiving consent and permission forms in Spanish.

All interviews were conducted over the phone, with caregivers given the option to be interviewed in either English or Spanish. Youth and their matched caregivers were interviewed separately. Interviews were scheduled at convenient times for participants, with confidentiality emphasized throughout the process. As substance use is often linked to prior traumatic experiences, a suicide safety protocol was implemented at the beginning of each interview for all participants. This protocol was intended to provide immediate support if any distress or suicidal ideation arose from participants.

Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes, and participants were compensated with a $35 electronic gift card. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and de-identified using a third-party transcription service, adhering to the guidelines of the Georgia State University (GSU) IRB. Interviews conducted in Spanish were first transcribed in Spanish and then translated into English for analysis. Data collection concluded once saturation was reached, defined as no substantially new or dissimilar responses emerging within youth interviews or separately within caregiver interviews.

This study followed all ethical guidelines set by the GSU IRB, ensuring participant confidentiality, voluntary participation, and the collection of informed consent or assent from all participants.

2.2 Data analysis

The analysis began with a set of a priori codes based on the four domains — human, financial, social, and community — of recovery capital as outlined in the RCAM. The initial codebook was tested on the first two matched interviews. The research team convened to discuss inductive codes and finalize the codebook. Three team members independently applied the final codebook to all transcripts, resolving any discrepancies through discussion. NVivo software was used for coding. Broader thematic categories were identified through collaborative analysis. This included examining contrasting cases to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the data, such as differing participant perspectives on recovery-related terminology [e.g., “sober” versus “clean”; (13–15)].

3 Results

3.1 Demographics

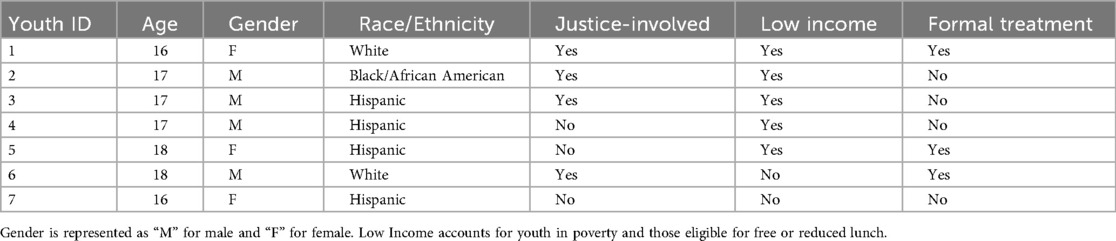

Fourteen matched interviews were conducted with seven adolescents (age 16–18) and their seven caregivers. The adolescent participants were 57.1% male and 71.4% Hispanic, with 57.1% reporting juvenile justice involvement and 71.4% either living in poverty or qualifying for free/reduced lunch. More than half (57.1%) had not received prior formal treatment for SUD. Among caregivers, 57.1% were Spanish-speaking (Table 1). Demographic data were not collected from caregivers.

3.2 Themes by recovery capital domain

The findings are organized according to the domains of RCAM, with additional themes included where relevant. To distinguish perspectives, findings are labeled (A) for adolescents and (C) for caregivers. When possible, matched adolescent-caregiver perspectives are presented together to highlight areas of agreement or divergence. Participant anonymity is maintained through randomly assigned participant numbers.

3.2.1 Community recovery capital

3.2.1.1 Engagement in substance-free activities

Both caregivers and adolescents identified the Recovery Clubhouse as a key source of community recovery capital (CRC), supporting adolescents' recovery by offering enjoyable, substance-free experiences and opportunities for creative expression. One adolescent explained, “…they [Clubhouse staff] were always introducing me to new stuff to do that caught my attention” (A5). Similarly, their caregiver remarked, “As soon as she started, she began to progress a lot. She learned new things like painting, which kept her mind busy” (C5).

3.2.2 Human recovery capital

3.2.2.1 Development of coping skills

Adolescents and caregivers both emphasized the role of Recovery Clubhouse enrollment (CRC) in helping youth to develop coping skills. These skills were important for managing stress and navigating external challenges, ultimately supporting decreased reliance and use of substances. One significant stressor shared by multiple youth involved the death of a loved one. Four adolescents recounted experiences of profound loss. One adolescent described how their father's passing led to substance use as a way to cope:

“See, the reason I really started smoking was, so I actually started.. I ain't never ever talk about…but I actually started smoking the day of my dad's funeral in 2018. Yeah, it was 2018. I was in last year of middle school in 2018. And it just made me feel better about everything. I don't think too much. You understand me…The program really kind of helped me with my coping skills. Every time I think about it, I just.. I don't know, I don't even think about it no more. My mind be on other stuff now,” (A2).

Another adolescent shared how they applied the strategies that they learned, “I use my coping skills..won't get mad or nothing. I'll just go to my room, take a break, and chill out” (A1). Their caregiver confirmed the impact of the Recovery Clubhouse, stating, “It helped with her coping mechanisms..” (C1).

3.2.2.2 Intrinsic versus extrinsic catalysts for change

Adolescents frequently reported that setting goals and finding personal motivation were essential to their recovery, particularly in reducing or stopping substance use. Many acknowledged that their motivation initially came from external sources, such as pressure from caregivers, probation officers, or other authority figures. These pressures often stemmed from negative consequences, including poor academic performance, expulsion, or involvement in the criminal justice system. Youth described how these external influences helped them to recognize a problem that they had not fully acknowledged. Over time, what began as extrinsic motivation gradually shifted into intrinsic motivation. This transformation strengthened their self-control and reduced their likelihood of returning to substance use. As one adolescent explained:

“I had to move in with my dad, and I didn't want to put my dad under the stress that I put my mom on. So, I just ultimately decided to just do better, and it all worked out. By now, I have really good self-control. I don't get tempted. I'm past the temptation and all of that” (A3).

Another adolescent similarly shared:

“Mostly it was because my mom was on my ass. She was like, ‘Take this drug test, and do this.’ That was one of the main reasons I stopped really, but mostly because of school..I was like, ‘Okay, let's stop messing around. Let's do this’” (A4).

3.2.3 Financial recovery capital

3.2.3.1 Employment and recovery motivation

Both adolescents and caregivers highlighted employment or the goal of future employment as crucial factors in supporting recovery. Adolescents viewed work as a way to remain accountable and financially independent, enabling them to pursue personal goals such as buying clothes or a car. One adolescent explained:

“I feel like when I get off probation, I would do it [smoking] from time to time, but not as much as I would when I was 15, just because I have actual things going in my life. I have work and stuff. You can't go to work high.. getting a job helps. It keeps your mind off drugs and stuff” (A3).

Caregivers also noticed positive changes when their adolescents began working, reporting that employment fostered a sense of responsibility and motivation. One caregiver shared, “Since he started working part-time, he's more motivated to work and go to school..he's picked up all his subjects, and his grades have improved” (C3).

In addition, some adolescents connected their desire to work with long-term goals. One participant stated, “I'm really into trying to get into a real estate program, but I need to work first to pay for the test and get my license” (A5). Their caregiver supported this ambition: “We're going to get her a little job so she can take a course in real estate” (C5).

3.2.3.2 Caregiver resource barriers

Another prominent theme within FRC was the barriers caregivers faced in supporting their young person's recovery and the resource constraints that limited their ability to provide consistent support. These barriers primarily included financial constraints, lack of transportation, and time limitations. While these challenges often made it difficult for caregivers to provide consistent recovery support, many emphasized that the Recovery Clubhouse helped mitigate these obstacles, allowing their adolescents to remain engaged in the program. Financial constraints were a major concern for caregivers, particularly when it came to providing recreational opportunities for their adolescents. One caregiver explained, “There are times when you can't [take your child out] since you just, well, don't have the money” (C7). This same caregiver also highlighted the transportation challenges that made it difficult to access recovery-supportive activities: “It's not like I can take her out all the time..I have to take a taxi. The Clubhouse takes her everywhere, to places we’ve never even heard of” (C7). One caregiver shared, “If it wasn't for them picking her up and bringing her home, I wouldn't be able to do it. She wouldn't be able to attend the program” (C1).

Time was another significant barrier, particularly for caregivers balancing multiple responsibilities. Three caregivers described how personal and family-related challenges limited their ability to provide the level of support they wanted. One caregiver, a single mother of four, expressed the relief provided by the Clubhouse's academic support:

“Being a single mom of four kids, the extra attention for my [youth] with [their] schoolwork and stuff really helps me out a lot. Because she don't have to come in here and be like, ‘Mom, I need help with this’” (C1).

Another caregiver spoke about the strain of managing court-related responsibilities and how these demands affected her ability to support her adolescent:

“I'm not saying my schedule doesn't revolve around my kids, but it revolves around my kids. I felt like I was having to spend more time taking him to court, dealing with this and that.. I just told him he was stressing me out” (C2).

For some caregivers, these barriers were compounded by significant life challenges. One caregiver described how a family tragedy—her younger son becoming a quadriplegic after a car accident—dramatically increased both her financial and caregiving burdens, making it even more difficult to support her adolescent's recovery:

“I had gone from working a full-time job to part-time, and just a lot more responsibility for all of us. We went from being active, outdoorsy people to having to plan around medical equipment. It was just a huge change in all of our lives, affecting us both financially and timewise,” (C6).

3.2.4 Social recovery capital

3.2.4.1 Therapeutic relationships with staff

A salient theme was the supportive relationships adolescents developed with Recovery Clubhouse staff (CRC), which were often viewed as essential to their recovery. One adolescent expressed, “I feel like I've developed really helpful relationships with the staff” (A6). Another shared, “They're really comforting, and if me and my mom got into an argument, the first people I would tell are the staff members” (A5). The importance of this staff support was further emphasized by another adolescent: “I ain't going to lie, they give me a lot of support. Really all of them as a group. Everybody had a helping hand for real. You can call them at any time” (A2).

Caregivers echoed the value of these relationships, often describing the staff as “family.” One caregiver remarked, “Yeah, he always talks about the staff.. They're like a family. He has his own little family” (C2). This sense of familial support from the staff was seen as vital in helping adolescents sustain their recovery and providing a trusted source of guidance.

3.2.4.2 Peer relationships

Both adolescents and caregivers frequently emphasized the role that peers played in shaping substance use prior to joining the Recovery Clubhouse. Most adolescents, or their caregivers, identified peer influence as a key factor in initiating and continuing substance use. For example, one adolescent (A1) shared, “It was a bad area. It was like a bunch of gang members and stuff. And I used to hang out with them. When I'd get around, there would be bad influence around me.” Their corresponding caregiver (C1) echoed this perspective, noting, “Well, I would say peer pressure,” which they believed played a central role in their adolescent's substance use.

However, not all experiences followed this pattern. One adolescent (A6) described a different situation, where their friends actively encouraged them to stop using substances:

“Really before, whenever I was smoking, the majority of my friends were people that would encourage me to stop smoking, and I'd tell them that I'd quit and I'd been quit for a week but then I'd go right back to it anytime I got the opportunity,” (A6).

Following enrollment in the Recovery Clubhouse, the narratives surrounding friendships and their role in recovery were similarly complex. Some adolescents described a complete reshaping of their social networks, while others mentioned reconnecting with old friends. For instance, A1 noted, “We moved away. So, I don't talk to them no more. They're not really friends. My new friends are not bad influences, they're actually my old friends I used to hang out with.”

Another adolescent (A4) explained the ongoing complexity of their social circles:

“I mean, right now, some old friends, for example, the guy showed me how to smoke for the first time, that guy's arrested and I blocked his number because he got into hard stuff. My new friends, they smoke, but they don't smoke on a regular basis. They just smoke during every two weeks or so during lunch, during school,” (A4).

In contrast, A5 adopted a more decisive approach to changing their social network:

“I mean, I've stopped being friends with a lot of people, mostly in school. Ever since I transferred to online, I had to cut people off because I know if I would stay friends with them, I would eventually go back to the old ways and I didn't want that, so I just cut a few people,” (A5).

Interestingly, few adolescents mentioned peers within the Recovery Clubhouse as primary sources of friendship or support. Instead, they tended to focus on relationships outside of the Recovery Clubhouse. Caregivers, on the other hand, often emphasized the importance of the friendships that their adolescents formed within the Recovery Clubhouse. For example, while A1 reflected on reconnecting with old friends, their caregiver (C1) focused more on the supportive relationships built within the Recovery Clubhouse, stating, “She sees that you can have fun without getting high. You can have friends without getting high. And they're facing the same challenges she's facing. So it helps motivate each other.”

3.2.4.3 Family involvement

Caregivers consistently praised caregiver and family group meetings, as well as family involvement in therapy sessions. These opportunities provided valuable insights into the recovery process, helping caregivers better understand their adolescent's needs and improve communication strategies.

Spanish-speaking caregivers highlighted the significance of receiving services in their native language, which helped to bridge gaps in understanding as well as facilitating more effective support for their adolescents. One caregiver shared:

“Those [family] meetings have opened.. They have opened my eyes a lot, a lot, because I’m telling you, I didn't know, I was in the world – you hear rumors and everything, but it's not the same as going to those meetings that explain everything step by step. So, I feel like as a mother, I’ve learned a lot, because now I’m very alert,” (C5).

Sentiments around family engagement varied among adolescents. Some expressed indifference about whether their caregivers attended meetings or events. For instance, one adolescent said, “I don't really care if my family comes or not” (A7). However, others expressed a desire for their caregivers to be more involved. As one adolescent shared, “I really do want to bring my family up there, to meet everybody, on family night. But we've really got a lot of stuff going on” (A1). Another adolescent felt that their caregivers could benefit from the engagement, saying, “I feel like they can learn a thing or two” (A3).

4 Discussion

4.1 Overview

This study was twofold: it applied the RCAM to investigate how adolescents and caregivers experience and perceive recovery capital, and it explored the perceived role of Recovery Clubhouses in building and sustaining those resources. The findings indicate that all four RC domains (CRC, HRC, FRC, and SRC) were important for adolescent recovery, and that the Recovery Clubhouse operated as a form of CRC through which participants accessed substance-free, developmentally engaging activities, supportive staff relationships, and practical supports. The multidimensional nature of recovery was evident in participants' accounts, with both adolescents and caregivers highlighting how substance-free activities, internal motivation, coping skills and emotion regulation, supportive relationships with staff, employment, and financial empowerment were important to their recovery. While adolescents and caregivers largely agreed on the importance of these resources, they differed in their views on peer relationships and family involvement within SRC, underscoring its complexity.

Both adolescents and caregivers consistently identified substance-free, enjoyable activities and opportunities for creative expression as essential components of CRC accessed through the Recovery Clubhouse. This reflects the importance of building recovery strategies and programs that are engaging, fun, and developmentally appropriate. These findings align with previous research on Recovery Support models such as Recovery High Schools and Alternative Peer Groups, which emphasize the need for age-appropriate environments that support recovery through engaging activities that adolescents perceive as more rewarding than substance use (16, 22–24). The activities offered in the Recovery Clubhouse not only kept adolescents engaged but also played a role in fostering resilience and emotional well-being.

HRC emerged as an important domain, particularly through the development of coping skills, emotional regulation, and goal-setting. Both adolescents and caregivers recognized that learning to manage stress and external pressures was crucial for recovery. Initially, many adolescents were driven by external motivators — such as legal requirements related to justice involvement or family expectations — rather than by intrinsic motivation. This is consistent with national findings indicating that 96.6% of adolescents with SUD do not perceive a need for treatment (19). Over time, however, external pressures often transformed into internal, self-driven motivations to remain in recovery. This finding reinforces previous research that suggests adolescents may not begin treatment by choice but can gradually internalize motivation as they progress (10). Caregivers supported this view, observing a shift in their adolescents' self-awareness and emotional resilience as they advanced in their recovery journey.

Caregivers particularly appreciated how the program alleviated financial burdens, such as covering transportation and providing recreational opportunities that they might not otherwise afford for their adolescents. Additionally, the Recovery Clubhouse helped address time-related barriers that caregivers faced, especially for those balancing multiple responsibilities or dealing with complex family dynamics. The ability to access these resources was crucial for consistent program participation as well as helping caregivers feel more equipped to support their adolescents. On the other hand, adolescents placed more emphasis on their personal employment as a key factor in their recovery. For them, employment not only offered financial independence but also served as a way to stay accountable and pursue long-term goals. While previous research has confirmed the importance of caregiver financial resources (12), this study expands upon these findings by demonstrating that adolescents also view financial empowerment (employment or future career goals) as an essential driver of recovery. While financial instability has been identified as a barrier to recovery among emerging adults between the ages of 18-25 (20), this study highlights that for younger adolescents (16–18), financial empowerment plays a similarly important role in supporting recovery. The emphasis on employment among these younger participants likely reflects the fact that 71.34% of adolescent participants come from low-income backgrounds. This highlights the importance of incorporating economic empowerment strategies in recovery programs, especially for economically disadvantaged youth.

Adolescents and caregivers presented differing perspectives on SRC. Prior to joining the Recovery Clubhouse, many adolescents reported that peers played a significant role in their substance use. While some reshaped their social networks during recovery, others maintained old friendships. Adolescents rarely mentioned peers within the Clubhouse as primary sources of support. Instead, they emphasized relationships with Recovery Clubhouse staff as their main source of connection and guidance within the program, while highlighting friendships outside the Clubhouse — sometimes with peers who continued using substances — as meaningful. Conversely, caregivers frequently viewed the friendships formed within the Clubhouse as vital to their young person's recovery. The contrast between how adolescents and caregivers prioritize types of friendships could also reflect differences in how adolescents perceive the benefits of friendships compared to their caregivers. These findings align with prior literature that highlights the dual influence of social networks (11). For instance, recovering adolescents described substance-using friends as a source of emotional support, while simultaneously recognizing them as a barrier to reducing or stopping substance use (11).

The RCAM posits that the domains of RC interact synergistically, and the findings of this study support this synergistic interaction. Improvements in one domain often led to gains in others. For instance, participation in substance-free activities (CRC) not only created engaging environments but also helped adolescents develop coping skills (HRC). Similarly, adolescents' pursuit of employment (FRC) contributed to internal motivation (HRC) by fostering a sense of accountability and offering a path toward financial independence. These findings emphasize the importance of addressing all RC domains in a holistic, integrated manner, where each domain reinforces the others to support long-term recovery.

4.2 Limitations

One limitation of this study is the lack of detailed demographic data on caregivers, which limits our understanding of the economic and social factors influencing their ability to support adolescent recovery. This gap is particularly relevant to the FRC findings, as it hinders a deeper exploration of why adolescents emphasized financial independence, such as having a job, as an important factor in their recovery. While youth-level data confirm that participants received free or reduced lunch and were living in poverty, the absence of caregiver-specific information, including household income, insurance coverage, and financial stability, prevents a more thorough exploration of how financial circumstances shape both caregiver support and youth recovery experiences.

Although conducting interviews by telephone limited access to nonverbal and contextual cues and may have led to shorter or less detailed responses (21, 22), this approach supported feasibility given the statewide sample. Prior studies also note that telephone interviews can enhance convenience, privacy, and disclosure, and often yield data comparable to face-to-face methods (23, 24).

4.3 Future directions and conclusion

Building on these findings, future research should examine how adolescent employment and financial independence contribute to long-term recovery outcomes. Investigating the integration of economic empowerment strategies into recovery programs could expand understanding of FRC and its impact on adolescents from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Additionally, the complexity of peer relationships in adolescent recovery warrants further exploration, with a focus on how adolescents reshape their social networks over time and how social recovery capital (SRC) evolves.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore recovery capital through matched interviews with adolescents and their caregivers, offering a unique dual perspective that underscores the alignment between the experiences of both groups while revealing differences in their perceptions of certain domains. This study reinforces the relevance of using the RCAM framework to conceptualize adolescent recovery from the perspectives of youth enrolled in a Recovery Clubhouse program and their caregivers. The findings highlight the importance of a multidimensional, strengths-based approach that addresses the unique developmental and social challenges adolescents face in their recovery journeys.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the sensitive nature of the qualitative data and the involvement of a vulnerable population (adolescents in substance use recovery). Full interview transcripts cannot be shared, as participants were assured strict confidentiality during the informed consent process. The data include personal narratives that could be potentially identifiable, even if de-identified. Requests to access the datasets should be directed tod2F2aWxhMUBnc3UuZWR1.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Georgia State University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participant and the participant's legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

WA: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization. CS: Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BT: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SM: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was part of a mixed-methods evaluation funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Funds from SAMHSA were distributed to the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, which provided financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article [#: 44100-906-CMA00003452].

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude to the adolescents, their families, and the Recovery Clubhouse staff for their invaluable contributions to this research. Special thanks to Kristal Davidson, Program Specialist at the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, Office of Addictive Diseases, for her support and guidance throughout the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP24-07-021, NSDUH Series H-59). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2024). Available online at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2023-nsduh-annual-national-report (Accessed September 19, 2024).

2. Brown SA, Vik PW, Creamer VA. Characteristics of relapse following adolescent substance abuse treatment. Addict Behav. (1989) 14(3):291–300. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90060-9

3. Burleson JA, Kaminer Y, Burke RH. Twelve-month follow-up of aftercare for adolescents with alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. (2012) 42(1):78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.07.001

4. Cornelius JR, Maisto SA, Pollock NK, Martin CS, Salloum IM, Lynch KG, et al. Rapid relapse generally follows treatment for substance use disorders among adolescents. Addict Behav. (2003) 28(2):381–6. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00247-7

5. Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Funk RR, Passetti LL, Petry NM. A randomized trial of assertive continuing care and contingency management for adolescents with substance use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2014) 82(1):40–51. doi: 10.1037/a0035264

6. Cloud W, Granfield R. Conceptualizing recovery capital: expansion of a theoretical construct. Subst Use Misuse. (2008) 43(12–13):1971–86. doi: 10.1080/10826080802289762

7. Cloud W, Granfield R. Natural recovery from substance dependency: lessons for treatment providers. J Soc Work Pract Addict. (2001) 1(1):83–104. doi: 10.1300/J160v01n01_07

8. Hennessy EA, Cristello JV, Kelly JF. Rcam: a proposed model of recovery capital for adolescents. Addict Res Theory. (2019) 27(5):429–36. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2018.1540694

9. Hennessy EA. Recovery capital: a systematic review of the literature. Addict Res Theory. (2017) 25(5):349–60. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2017.1297990

10. Nash AJ, Hennessy EA, Collier C. Exploring recovery capital among adolescents in an alternative peer group. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2019) 199:136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.02.025

11. Jurinsky J, Cowie K, Blyth S, Hennessy EA. “A lot better than it used to be”: a qualitative study of adolescents’ dynamic social recovery capital. Addict Res Theory. (2023) 31(2):77–83. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2022.2114076

12. Hennessy EA, Finch AJ. Adolescent recovery capital and recovery high school attendance: an exploratory data mining approach. Psychol Addict Behav J Soc Psychol Addict Behav. (2019) 33(8):669–76. doi: 10.1037/adb0000528

13. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, Panter AT, Rindskopf D, Sher KJ, editors. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association (2012). p. 57–71. (APA handbooks in psychology®).

14. Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E. Applied Thematic Analysis. 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States: SAGE Publications, Inc. (2012). Available online at: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/applied-thematic-analysis (Accessed September 10, 2023).

15. Riessman CK. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Los Angeles: Sage Publications (2008). p. 251.

16. Nash A, Marcus M, Engebretson J, Bukstein O. Recovery from adolescent substance use disorder: young people in recovery describe the process and keys to success in an alternative peer group. J Groups Addict Recovery. (2015) 10(4):290–312. doi: 10.1080/1556035X.2015.1089805

17. Yule AM, Kelly JF. Recovery high schools may be a key component of youth recovery support services. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2018) 44(2):141–2. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1380033

18. McKay JR. Making the hard work of recovery more attractive for those with substance use disorders. Addiction. (2017) 112(5):751–7. doi: 10.1111/add.13502

19. SAMHSA. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. (2024). Available online at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt47095/National%20Report/National%20Report/2023-nsduh-annual-national.pdf (Accessed August 31, 2024).

20. Elswick A, Fallin-Bennett A, Ashford K, Werner-Wilson R. Emerging adults and recovery capital: barriers and facilitators to recovery. J Addict Nurs. (2018) 29(2):78. doi: 10.1097/JAN.0000000000000218

21. Irvine A. Duration, dominance and depth in telephone and face-to-face interviews: a comparative exploration. Int J Qual Methods. (2011) 10(3):202–20. doi: 10.1177/160940691101000302

22. Irvine A, Drew P, Sainsbury R. ‘Am I not answering your questions properly?’ clarification, adequacy and responsiveness in semi-structured telephone and face-to-face interviews. Qual Res. (2013) 13(1):87–106. doi: 10.1177/1468794112439086

23. Novick G. Is there a bias against telephone interviews in qualitative research? Res Nurs Health. (2008) 31(4):391–8. doi: 10.1002/nur.20259

Keywords: adolescent, recovery capital, Recovery Capital for Adolescents Model, recovery, qualitative

Citation: Avila Rodriguez W, Smith C, Taylor BJ and McLaren S (2025) Understanding recovery capital: voices of adolescents and caregivers from the Georgia recovery support clubhouse program. Front. Adolesc. Med. 3:1599348. doi: 10.3389/fradm.2025.1599348

Received: 24 March 2025; Accepted: 28 October 2025;

Published: 27 November 2025.

Edited by:

Jo-Hanna H Ivers, Trinity College Dublin, IrelandReviewed by:

Ulla-Karin Schön, Stockholm University, SwedenJordan Jurinsky, Tufts University, United States

Copyright: © 2025 Avila Rodriguez, Smith, Taylor and McLaren. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wendy Avila Rodriguez, d2F2aWxhMUBnc3UuZWR1

Wendy Avila Rodriguez

Wendy Avila Rodriguez Colleen Smith

Colleen Smith Brittany J. Taylor

Brittany J. Taylor Susan McLaren

Susan McLaren