- 1Department of Soil and Geological Sciences, Sokoine University of Agriculture, College of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania

- 2Department of Environmental Science and Technology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, United States

Sulphur (S) deficiency in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), driven by soil degradation and S-free fertilisers, threatens crop yield and protein quality. This systematic review synthesises four decades of studies (1980–2024) to assess soil S status, analysis methods, management challenges, and recommended rates for effective fertilisation to improve sustainable productivity. A systematic literature review was conducted following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) framework to synthesise available evidence on S nutrient management in agricultural soils across SSA. The review revealed that S concentrations were generally higher in surface horizons compared to sub-surface layers, with vertical distribution influenced by soil texture, pedogenic processes, organic matter content, and fertiliser inputs. In highly weathered soils, S depletion was pronounced, contributing to widespread deficiencies across SSA’s agricultural landscapes. Analysis of S fertilisation practices showed a research cereal crop (s) emphasis, accounting for 65% of studies, followed by legumes with 25% and oilseeds with 10%. Most of the cereal studies have reported S application rates between 0 and 30 kg S/ha, with 71% of studies applying ≤20 kg S/ha. Legumes, by contrast, received higher rates (21–40 kg S/ha), typically through potassium sulphate or nitrogen-phosphorus-sulphur (NPS) blended fertilisers. Yield responses to S application varied significantly by crop type. Maize exhibited the higher yield increase, ranging from 20% to 260% depending on the fertiliser application rate, followed by wheat and rice. Legumes such as soybeans showed more modest increase of 25%, while oilseeds like canola and sesame responded minimally, even under higher S inputs. These findings underscore the need for crop- and site-specific S management strategies in SSA. The adoption of soil testing and decision-making frameworks such as the 4R nutrient stewardship (right source, rate, time, and place) is recommended to optimise crop yield and reduce environmental risks associated with nutrient mismanagement.

1 Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goal 2.2 aims to end all forms of malnutrition. However, many countries are not on track to achieve this target (Scott et al., 2020). Malnutrition remains a global challenge, particularly in regions where food security is compromised (Al-Worafi, 2023). Among the often-overlooked contributors to malnutrition and food insecurity is soil fertility, which directly influences the nutritional content of crops (Lehmann et al., 2020; Ramaswwamyreddy and Basavaraju, 2022). Soil infertility not only reduces crop yields but also diminishes the nutritional quality of food, disrupting overall food production. Therefore, a soil fertility approach is essential to improve both the productivity and nutritional value of food crops, thereby strengthening food systems (Havlin and Heiniger, 2020).

Sulphur (S) constitutes approximately 0.06–0.10% of the earth’s crust, making it the 13th most abundant element and an essential nutrient for plant growth (Udayana et al., 2021). Mineralisation of soil organic matter provides about 95% of plant-available S (SO4²-) in most soils, contributing about 4–12 kg S ha-¹ annually (Sharma et al., 2024; Weil and Brady, 2016). Plants can also absorb gaseous S (GS) from atmospheric hydrogen sulphide and sulphur dioxide (SO2) (Telman and Dietz, 2019). S is involved in the synthesis of amino acids, proteins, and enzymes, which are critical for plant structure and physiological processes, including photosynthesis, respiration, and nutrient uptake, and form part of various vitamins, coenzymes, and secondary metabolites (de Mello Prado, 2021b; Havlin et al., 2017; Mengel and Kirkby, 2001).

Over the past decade, the atmospheric composition of SO2 has been decreasing (Opio et al., 2021). Although this is positive in the environmental protection context, it negatively affects the amount of atmospheric GS taken up by plants (Narayan et al., 2022). At the same time, land degradation and climate change threaten soil organic matter, a key source of S (Das et al., 2024). This growing vulnerability of S sources underscores the need to integrate S into nutrient management programs alongside nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) (Sharma et al., 2024). S deficiency has become a global concern, with plant-available S in soils estimated to have declined by 34–86% (Sharma et al., 2024). Reduced atmospheric deposition, coupled with seasonal burning of vegetation and crop residues, further limits S availability for crops (Cassou, 2018; Harou et al., 2022).

In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), trends in S application reveal critical gaps in nutrient management. Over 80% of smallholder farmers rely on nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium (NPK) fertilisers that contain little or no S (Johnson et al., 2023). Despite widespread fertiliser use, S is often excluded from government recommendations in many SSA countries, such as Tanzania (Hemesh, 2020; Michelson, 2017). The Limited adoption of S-containing fertilisers, such as superphosphates or ammonium sulphate, is driven by factors including higher cost, low availability and lack of awareness among farmers and extension agents (Johnson et al., 2023). Moreover, the environmental risks associated with poorly managed S fertiliser use remain underexplored in SSA, adding to the existing knowledge gap. Research on S nutrition in SSA remains fragmented, with limited region-specific recommendations that account for local soil types, crop types, and environmental conditions. This lack of integrated knowledge limits the development of effective strategies to mitigate S depletion, exacerbating hidden hunger and yield gaps. Exploring S nutrition management is therefore critical to optimise fertiliser use, enhance crop productivity and nutritional quality, and contribute to food security.

To address these challenges, this systematic literature review was conducted to synthesize existing knowledge on S nutrient management in agricultural soils of SSA. The review aimed to examine the current status of S in soils, its implications for crop productivity and environmental sustainability, and available recommendations for optimal S management. It also critically assessed soil sampling depths and extraction methods, which are essential for accurate evaluation of soil S status. Covering studies from 1980 to 2024, this review highlights the potential of improved S management as a strategy to strengthen food security in SSA.

2 Methodology

2.1 Literature search

The review utilised the preferred reporting Items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) framework, as described by Page et al. (2021), for collecting and reporting information on S in agricultural soils in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). This method is widely recognised for evaluating published systematic reviews through critical analysis (Hutton et al., 2015). To find and download journal articles and published reports, a literature search was conducted in four academic databases and search engines: Web of Science (http://apps.webofknowledge.com/), ScienceDirect (https://www.sciencedirect.com/), PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/) The systematic search aimed at selecting fully published journal articles by carefully crafting search strings, ensuring that the majority of relevant articles for the review objective were included.

All search terms were based on predefined keywords related to the title, keywords, and abstract of the articles. To refine and hone the search results, specific keywords included (“Sulphur” OR “Sulfur”) AND (“fertiliz*” OR “fertilis*” OR “nutrition” OR “deficiency” OR “status”) AND (“crop production” OR “yield” OR “growth”) AND (“sub-Saharan Africa” OR names of specific countries like “Tanzania” OR “Kenya” OR “Nigeria”). The search was limited to English-language articles in the fields of agriculture, biological sciences, and plant sciences.

2.2 Article screening and classification

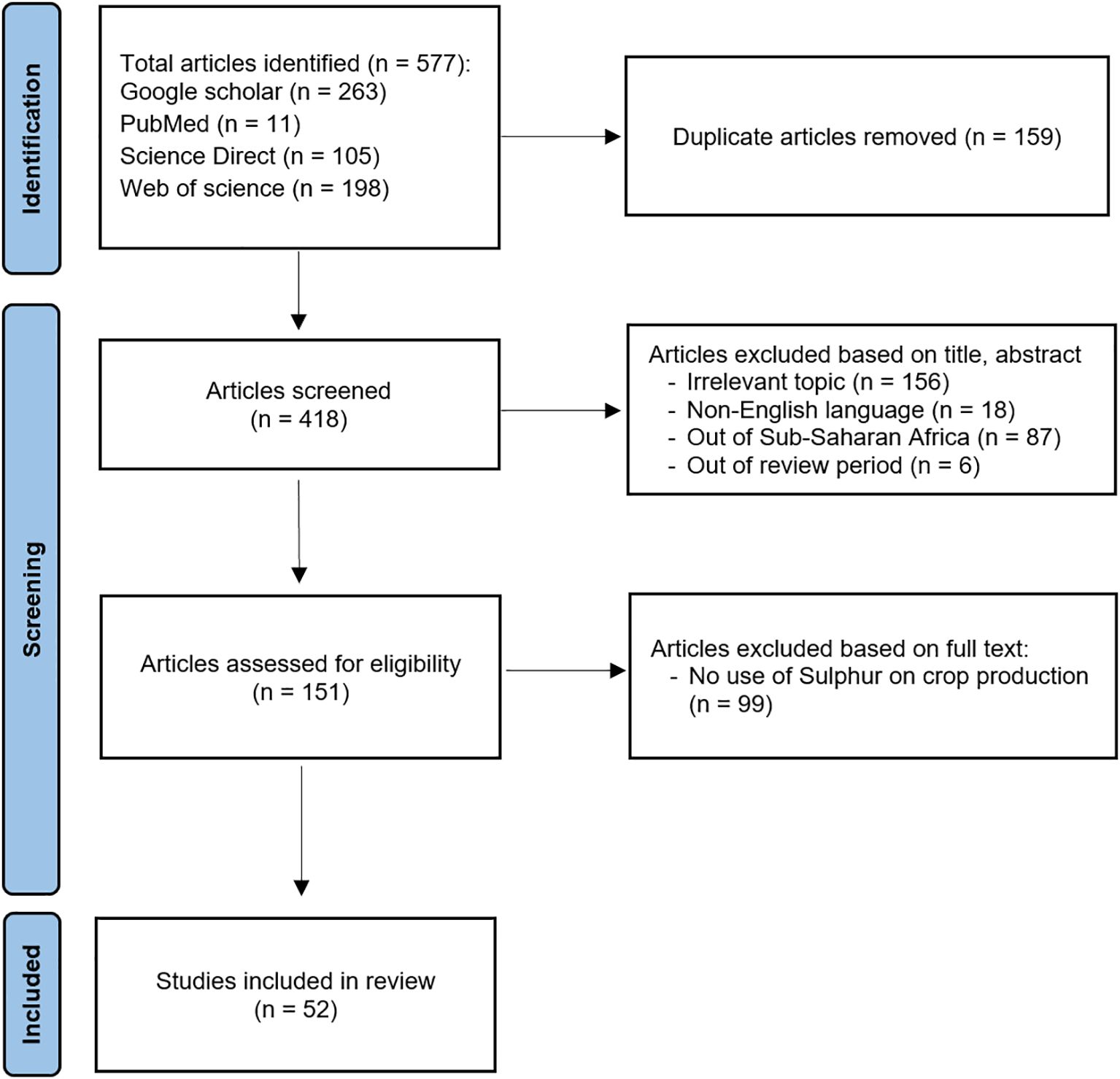

A total of 577 journal articles were identified through a search conducted to identify articles published between January 1980 to June 30, 2024. Of these, 156 articles were removed as duplicates, and the remaining 419 articles were further screened. The inclusion criteria used included (i) original research studies, (ii) studies that investigated soil S status and management in crop production, (iii) studies conducted within Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (iv) studies published within the time frame of 1980 – 2024, and (v) studies written exclusively in the English language. During the initial screening of titles and abstracts, 267 articles out of 419 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Following a thorough filtering, 97 out of the 152 remaining articles were eliminated because the main text did not contain relevant information directly related to the review’s scope. In the end, 55 articles were included after a thorough full-text screening. The flowchart of the entire process from identifying the relevant literatures to making the final inclusion decision is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The articles screening flowchart, based on the preferred reporting Items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) approach modified by Page et al. (2021).

The included articles focused on various parameters, including the year of publication, the S extraction method used, the study country, as well as study target. Additionally, we assessed the target crop, S materials, and rates used to supply S for the crop production. The summary of the evaluated parameters is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Overview of the relevant articles

3.1.1 Spatial and temporal trend of sulphur researches

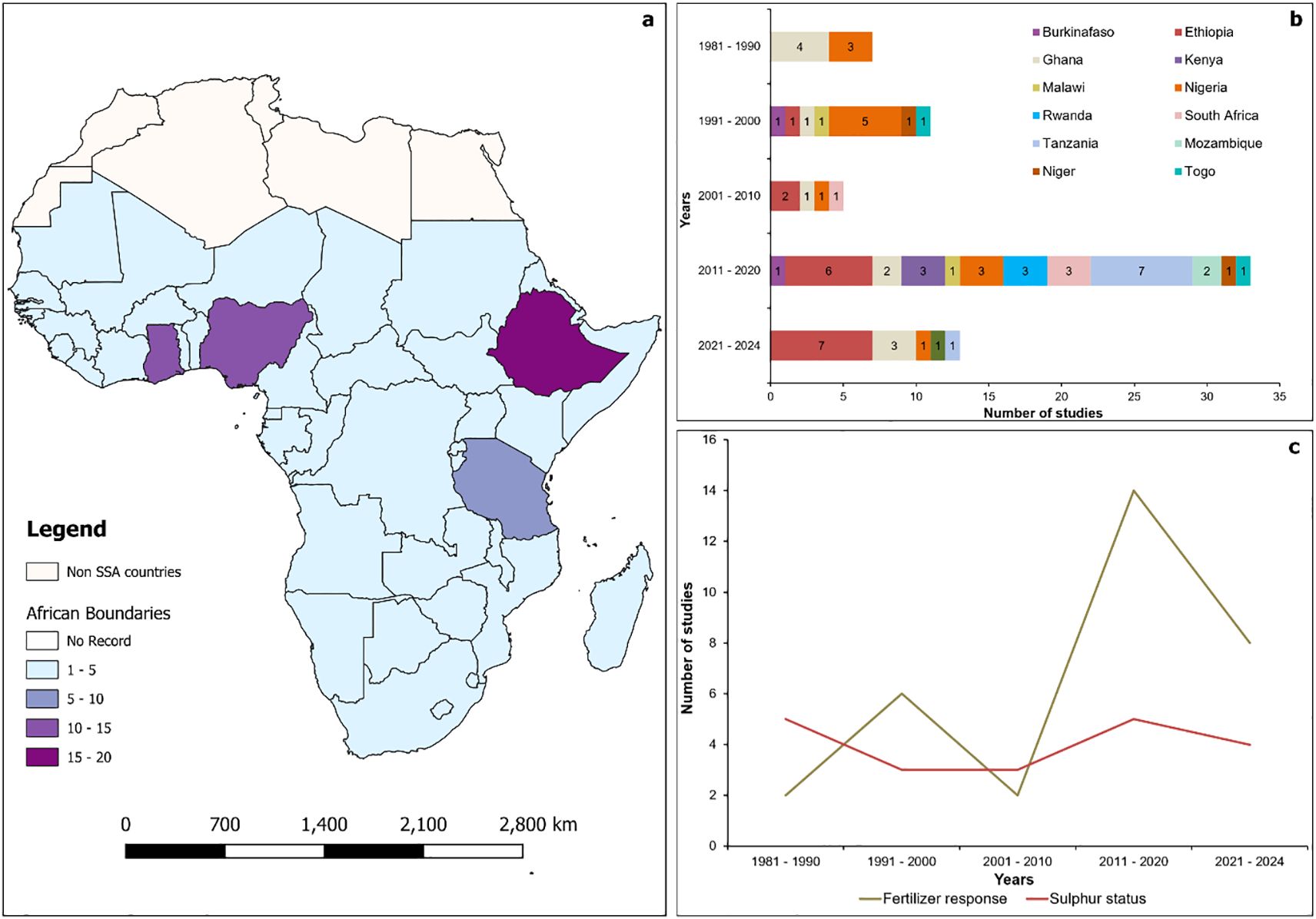

The spatial and temporal distributions of sulphur (S) studies across various regions in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are as illustrated in Figure 2. Over the past four decades, there has been a noticeable general increase in research focused on S and its impact on crop production. While many SSA countries began studying S in the 1990s, the number of studies has significantly increased since 2011 (Figure 2b). Nigeria has maintained a consistent focus on S management throughout all decades, whereas a significant number of the research (24% of the articles) has been concentrated in Ethiopia. Among the analysed articles, 58% (30 articles) investigated the role of S in plants, 27% (14 articles) focused on S in soils, and 15% (8 articles) examined both soil and plants. Additionally, 62% (32 articles) of the studies assessed how various crops respond to different S-containing fertilisers, while 38% (20 articles) evaluated the status of S in the soil (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Trend on S related studies across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) for the period between 1980 to June 2024 (a) Africa map showing sulphur (S) studies per SSA countries (b) A graph showing number of S articles published per each decade in SSA countries, and (c) A graph showing trend of S studies type over the past four decades.

The increase in soil S research across sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) since the 1990s is largely driven by nutrient depletion due to the soil degradation caused by climate change and unsustainable nutrient management (Abebe and Beyene, 2021; Lal and Stewart, 2019). Nigeria’s consistent studies into S management highlight the country’s long-standing recognition of S deficiency as a significant barrier to crop productivity, especially in its Savannah zone (Adetunji, 1992; Kang et al., 1981; Kwari et al., 2009). Ethiopia’s prominence (24% of studies) reflects its efforts in improving crop performance through the alternative use of S-containing materials in various crop plants (Getachew et al., 2017; Habtegebrial and Singh, 2009; Tehulie and Yimer, 2021).

The predominance of plant-focused studies (58% of articles) and the emphasis on crop responses to S-containing fertilisers (62% of articles) indicate some efforts to tackle S deficiencies, which have been worsened by the prolonged use of low-S nitrogen-phosphorus or nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium (NPK) fertilisers along with a decline in soil organic matter (Getinet et al., 2022; Harou et al., 2022). However, the relatively small proportion of studies analysing soil-S status (38%) highlights a research need, so as to understand long-term S cycling and availability, especially in regions with heavy rainfall and weathered soils that are susceptible to leaching (Ulén, 2020).

3.1.2 Soil sulphur extraction methods in Sub-Saharan Africa

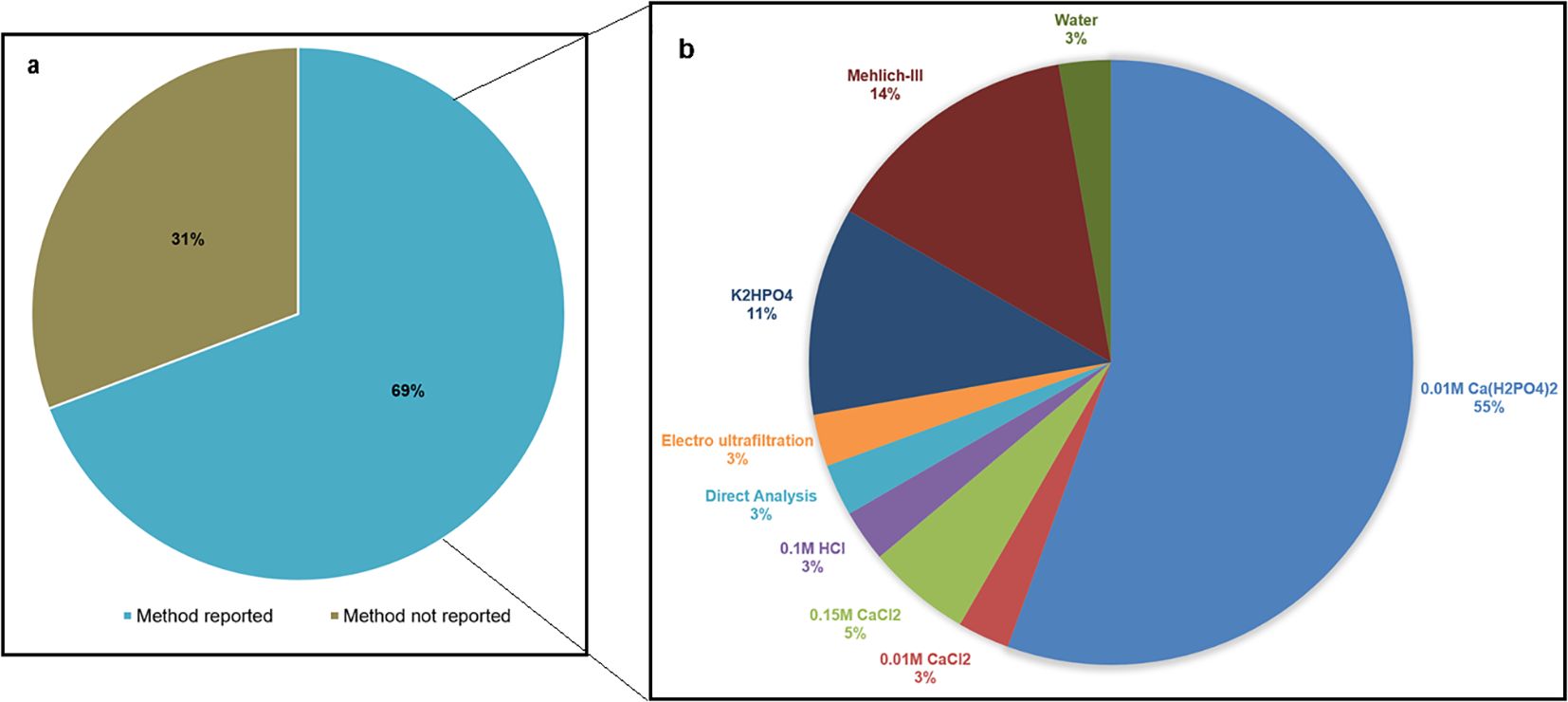

The results showed significant methodological variation in soil S extraction across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) studies (Figure 3). Among the reviewed articles, 69% (36 studies) explicitly reported soil-S extraction protocols, while 31% omitted methodological details (Figure 3a). Of the reported methods, the 0.01 M monocalcium phosphate (Ca(H2PO4) 2) extraction method dominated, accounting for 55% (20 articles), followed by Mehlich-III at 14% (5 articles) and monopotassium phosphate (KH2PO4) at 11% (4 articles). Less common methods included 0.015 M CaCl2 (5%, 2 articles), water extraction, and 0.1M HCl (3% each, 1 article) (Figure 3b). Two studies that used electro ultrafiltration and direct analysis on dried soil samples applied ion chromatography and X-ray fluorescence method of analysis, respectively.

Figure 3. Percentage presentation of (a) reporting status and (b) the reported soil-S extraction methods by various studies in sub-Saharan Africa.

Variation in extraction methods has important practical implications for S-related soil research in SSA. The predominance of 0.01 M Ca(H2PO4)2 aligns with its global acceptance for estimating SO4²--S in acidic to neutral soils (Bankole et al., 2022; Tabatabai, 1982), which are common across SSA. Its cost-effectiveness and simplicity make it ideal for low-resource laboratories. However, its reliance on SO4²- extraction overlooks organic S pools (Watkinson and Kear, 1996), which are critical in contributing about 95% of available plant-S in soils (Haneklaus et al., 2007; Tabatabai, 1982; Weil and Brady, 2016). Thus, imposing risk in misinterpreting S availability, especially in organic-rich soils, where mineralisation rates may affect crop uptake. The underuse of other methods, such as electro ultrafiltration and direct analysis, coincides with infrastructural limitations, favouring resource-rich institutions such as those used by Fischer et al. (2020) and Uloro and Mengel (1994). Conversely, the CaCl2 extraction method is underutilised despite its relevance in efficiently extracting soil-S (Amuri et al., 2023; Ketterings et al., 2011). The omission of extraction methods in 31% of studies hinders study reproducibility and undermines data harmonisation for policy frameworks like national and regional fertiliser and soil health programs.

3.2 Available guide for the soil sulphur interpretation

Soil sulphur (S) levels are interpreted relative to the extraction method used, as each extractant varies in its ability to extract different S fractions, and associated crop responses to applied S. In Tanzania, for example, Amuri et al. (2023) reported a critical concentration range of 4.1–4.8 mg S/kg for S extracted using 0.01 M CaCl2 with the SoilDoc method, providing a localised benchmark for deficiency assessment. In Ethiopia, a critical range of 20–80 mg/kg following extraction by Mehlich-III has been proposed by the Ethiopia Soil Information System [EthioSIS], 2014, as reported by (Lelago et al., 2016). For the widely used 0.01 M Ca(H2PO4)2 method, Horneck et al. (2011) proposed the following classification: < 2 mg S/kg as very low, 2–5 mg/kg as low, 5–20 mg/kg as medium, and >20 mg/kg as high. In tropical contexts, Landon (1991) recommended slightly higher threshold values, classifying a critical range of 6–12 mg S/kg as adequate for various extraction methods. Furthermore, Peverill et al. (1999) suggested a general sufficiency range of 5–10 mg S/kg that could apply to multiple methods, including both 0.01 M Ca(H2PO4)2 and KCl extractions. These ratings provide essential context for interpreting soil S data and identifying potential deficiencies, based on the specific extraction method used. However, for efficient and accurate interpretation, there is a pressing need to align critical values with both the extraction method and geographic context.

3.3 Sulphur fertility status in Sub-Saharan Africa agricultural soils

Sulphur (S) status in soils varies with soil depth. Thus, to determine general S fertility status in soils, this study categorised sampling depth into two groups (shallow topsoil sampling: 0–15 cm, and deeper sampling: 0 – 20/30 cm). A total of 14 studies were conducted at the 0–15 cm depth, with the majority located in West Africa, notably in Nigeria and Ghana, between 1987 and 2022. Studies with shallow-depth sampling are comparatively rare in East and Southern Africa, with only one example from Malawi (Weil and Mughogho, 2000). In contrast, the 0–20/30 cm category dominates the literature, comprising 34 studies spread across East, Southern, and West Africa. This deeper sampling approach has been prevalent from the early 1990s through to 2024, reflecting a widespread emphasis on deeper sampling S dynamics.

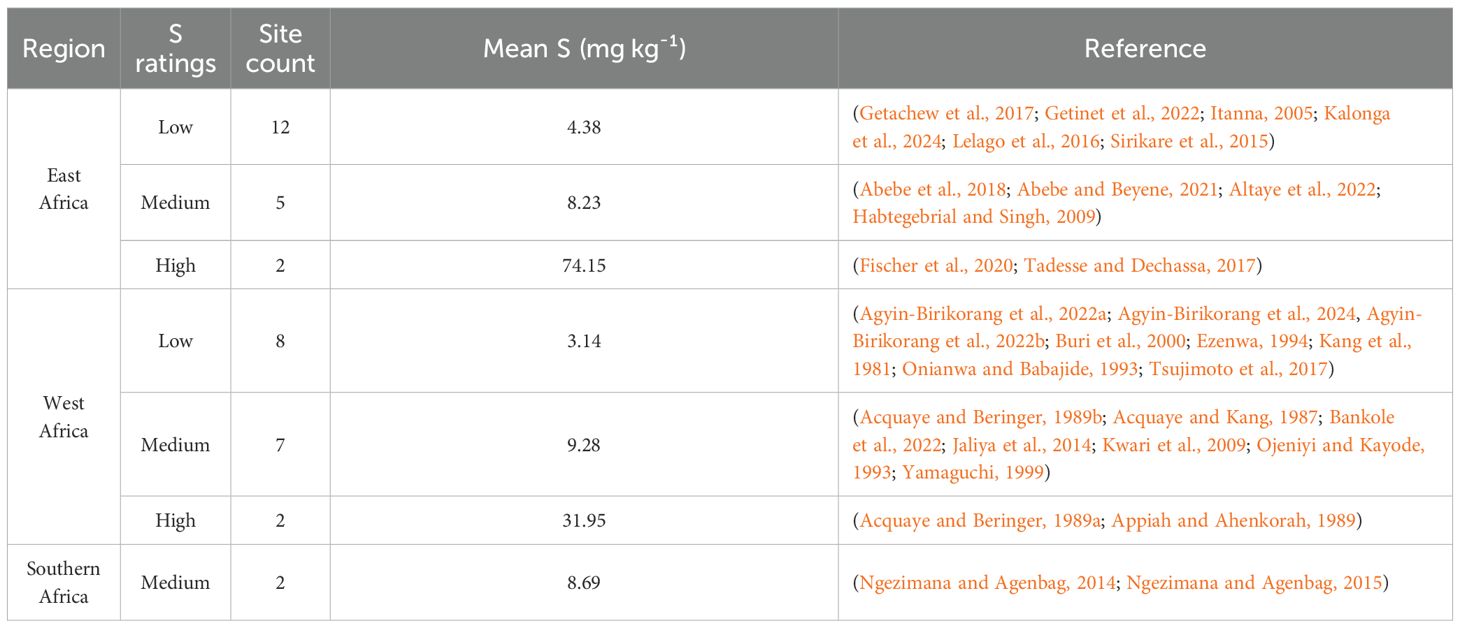

Of the 52 reviewed articles, 31 reported soil S status, covering 38 experimental sites across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). A regional assessment of soil S status revealed distinct regional variability (Table 1). In East Africa (n = 19), the majority of sites (63.2%, n = 12) were classified as having low S levels, with a mean extractable S concentration of 4.38 mg kg-¹. Medium and high S levels accounted for 26.3% (n = 5; mean = 8.23 mg kg-¹) and 10.5% (n = 2; mean = 74.15 mg kg-¹) of sites, respectively. In West Africa (n = 17), low S was observed at 47.1% of sites (n = 8; mean = 3.14 mg kg-¹), followed by medium S (41.2%, n = 7; mean = 9.28 mg kg-¹) and high S (11.8%, n = 2; mean = 31.95 mg kg-¹). In Southern Africa (n = 2), both sites fell within the medium S category, with a mean S concentration of 8.69 mg kg-¹. Overall, low S status was the most prevalent across the SSA fields, representing 55.3% of all observations. Ratings were determined using interpretation ranges for most commonly used extraction reagents based on Landon (1991) and for the Mehlich-III thresholds by Ethiosis (2014), as cited in (Lelago et al., 2016).

Table 1. Summary of rating for status of the extractable soil sulphur reported in various sites in Sub Saharan Africa.

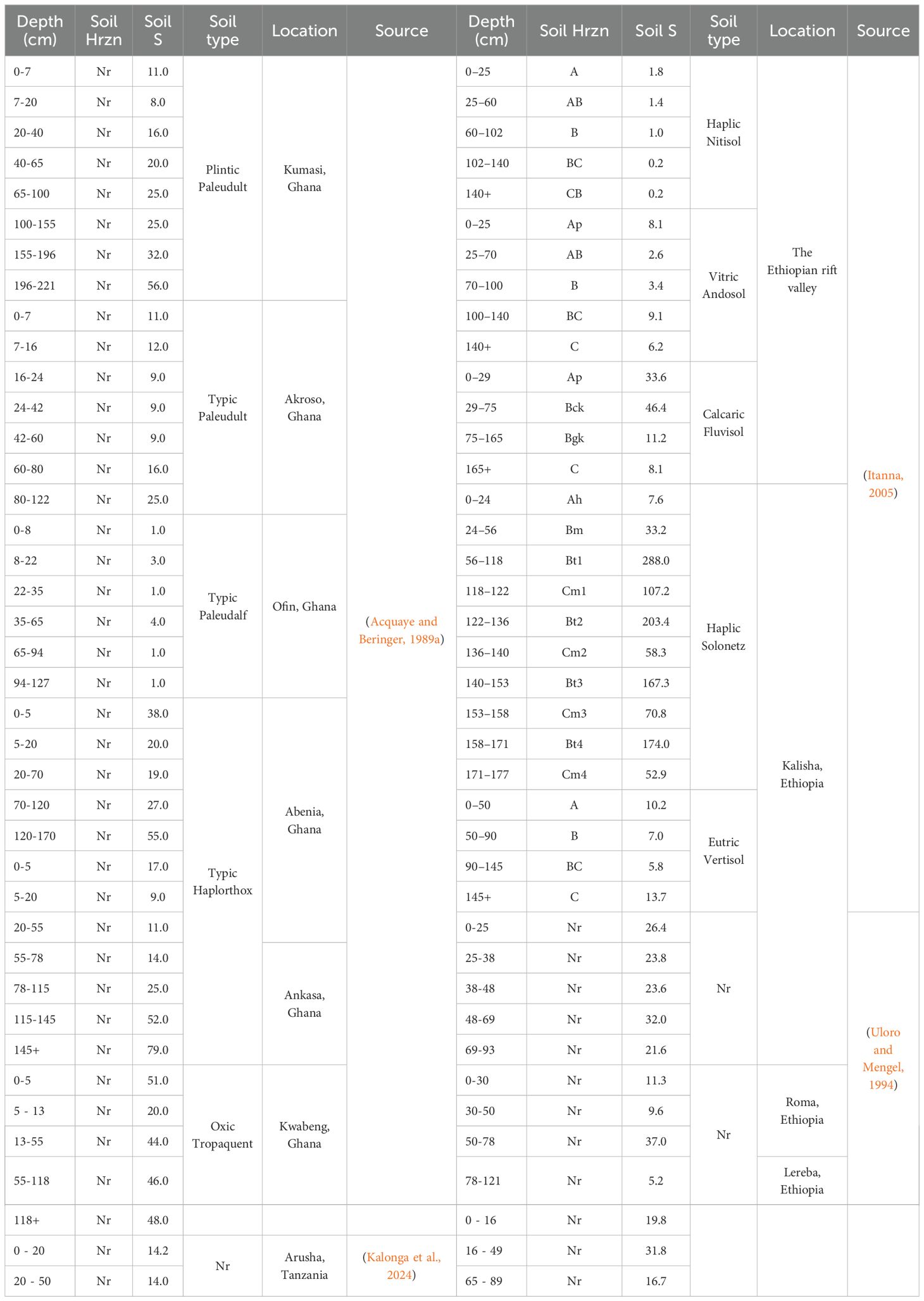

S concentrations in soil profiles varied significantly with depth, showing distinct vertical distribution patterns across sites and soil types (Table 2). S levels in the topsoil (0–20 cm) ranged broadly from 1.0 to 51.0 mg/kg. Low values were observed in Typic Paleudalf profiles in semi-deciduous rain forest of Ofin, Ghana, with 1.0–4.0 mg/kg, while high concentrations were recorded in Typic Haplorthox (38.0 mg/kg) and Oxic Tropaquent (51.0 mg/kg) of Ankasa and Kwabeng profiles, respectively (Acquaye and Beringer, 1989a). Uloro and Mengel (1994) reported 26.4 mg/kg in the 0–25 cm layer in Loam soils of Kalisha, Ethiopia, while Kalonga et al. (2024) reported 14.2 mg/kg at 0–20 cm and 13.95 mg/kg at 20–50 cm at the Maasai landscape of Arusha, Tanzania, indicating low Mehlich-III S levels. In the Ethiopian rift valley, Haplic Nitisols had low S levels; at 25–60 cm depth was 1.4 mg/kg, while at 60–102-cm depth was 1.0 mg/kg (Itanna, 2005). In contrast, Calcaric Fluvisols recorded elevated values: 33.6 mg/kg at 0–29 cm and 46.4 mg/kg at 29–75 cm. Similarly, Haplic Solonetz profiles showed 7.6 mg/kg in the Ah horizon (0–24 cm) and 33.2 mg/kg in Bm (24–56 cm), with progressively higher values in deeper clay horizons. S concentrations were highly variable in deeper layers, ranging from 0.2 to 288.0 mg/kg. In profiles like the Vitric Andosol and Haplic Nitisol, very low S levels were recorded (e.g., 0.2–1.0 mg/kg between 60 and 140 cm) (Itanna, 2005). However, Haplic Solonetz showed extraordinarily high values in Bt and Cm horizons: 288.0 mg/kg (56–118 cm), 107.2 mg/kg (118–122 cm), and 203.4 mg/kg (122–136 cm). Loam soil in Kalisha, Ghana, exhibited high S levels from 25 to 93 cm, ranging between 23.6 and 32.0 mg/kg (Uloro and Mengel, 1994).

Table 2. Variation in sulphur levels in the soil profile as reported across Sub-Saharan African countries. Note: S – soil sulphur (mg/kg), Nr – not reported, Soil Hrzn – soil horizon.

The increased focus on deeper sampling aligns with agronomic research prioritising cereals (maize, sorghum) and legumes (soybean, common beans), whose root systems often extend >15 cm deep (Supplementary Table 1). Determining S in deeper soil is critical for these crops, as grain filling and nitrogen fixation depend on sustained S availability beyond surface layers. The observed regional differences in soil S status reflect underlying variations in agroecological conditions, soil parent material, land use intensity, and fertiliser management across SSA. The predominance of low S concentrations in East and West Africa soils is consistent with the inherently low S reserves of many weathered tropical soils and may be further exacerbated by continuous cropping, low use of S-containing fertilisers, and nutrient depletion (Tabatabai, 1982).

The low mean S levels remain below agronomically sufficient thresholds in East and West Africa regions (4.07 mg/kg in East Africa and 3.87 mg/kg in West Africa), highlighting a widespread risk of S deficiency that could limit crop productivity (Haneklaus et al., 2007; Landon, 1991). Conversely, the high S values of 74.15 mg/kg and 31.95 mg/kg occurred in a few East and West African sites, respectively. These observed high S values suggest localised enrichment, potentially due to site-specific factors, for instance, deposition from volcanic ash such as in parts of Kenya (Omenda, 2011), manure or compost applications, or mineralogical contributions from the parent rock (Haneklaus et al., 2007; Weil and Brady, 2016). The medium S levels in Southern Africa, though based on limited data, may reflect inherent soil characteristics or more effective nutrient management practices (Ngezimana and Agenbag, 2014; Ngezimana and Agenbag, 2015). However, these findings highlight the need for more comprehensive representative data to enable more robust conclusions. Overall, the spatial heterogeneity in soil S levels underscores the need for site-specific diagnostics and the integration of S into balanced fertilisation strategies. These findings also emphasise the importance of providing extraction methods used for accurate compilation or comparisons to scale to support informed nutrient management recommendations. Soil S stratification with depth is primarily shaped by pedogenic processes, texture, and leaching intensity (Weil and Brady, 2016). Surface horizons typically exhibit high soil S concentrations (Table 2), which may be attributed to organic matter inputs and fertiliser additions (Acquaye and Beringer, 1989a; de Mello Prado, 2021a). Subsurface layers often retain moderate S levels, as seen in Calcaric Fluvisols and Haplic Solonetz (Table 2), where limited leaching or higher clay content restricts vertical S movement. In contrast, sharply reduced S levels (to values less than 1.0 mg/kg) in Haplic Nitisols reflect the influence of organic matter accumulation in surface horizons of highly weathered profiles (Itanna, 2005). Exceptionally high S accumulation (up to 288 mg/kg) in the Bt horizon of clay-rich Haplic Solonetz is likely due to SO4²- illuviation and restricted drainage. Data from Tanzania show similarly low Mehlich-III S in both topsoil (14.2 mg/kg) and subsoil (13.95 mg/kg), potentially due to S depletion from continuous cultivation and limited organic inputs (Kalonga et al., 2024).

Organic matter stabilises S through microbial mineralisation–immobilisation cycles, which decline with depth (Das et al., 2024). Moreover, routine soil tests may underestimate subsoil S in clay-rich profiles due to strong adsorption onto mineral surfaces, rendering some S non-extractable (Bankole et al., 2022; Tabatabai, 1982; Weil and Brady, 2016). Such conditions may explain the widespread low S reported in subsoils (Acquaye and Beringer, 1989a; Bankole et al., 2022). Soil texture and organic matter further mediate S retention by influencing leaching and adsorption: loam soils, for instance, maintained moderate to high S (21.6–32.0 mg/kg) throughout the upper 90 cm due to favourable nutrient-holding capacity (Uloro and Mengel, 1994). In contrast, coarse-textured, weakly developed soils readily lose SO4²-, while highly weathered tropical soils with abundant Fe and Al oxides can strongly retain it (Weil and Brady, 2016). These findings underscore the importance of depth-specific S assessments in developing tailored nutrient management strategies for diverse agroecosystems across SSA.

3.4 Yield response to sulphur-containing fertilisers

3.4.1 Status of sulphur fertiliser use in Sub-Saharan Africa

Crop sulphur (S) response studies have been conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) targeting the four main groups of staple crops, Cereals: Barley, Maize, Sorghum, wheat and rice; Legumes: common beans, soybeans; Oilseeds: canola and sesame; and other crops like banana and cotton. The analysis revealed that cereals dominate the S management research, accounting for about 65% of study articles. Legumes represent about 25% of studies, while oilseeds are under-represented, with about 10% of study articles. Only 5% of articles focus on other crops, indicating a critical need for research on non-cereal crops.

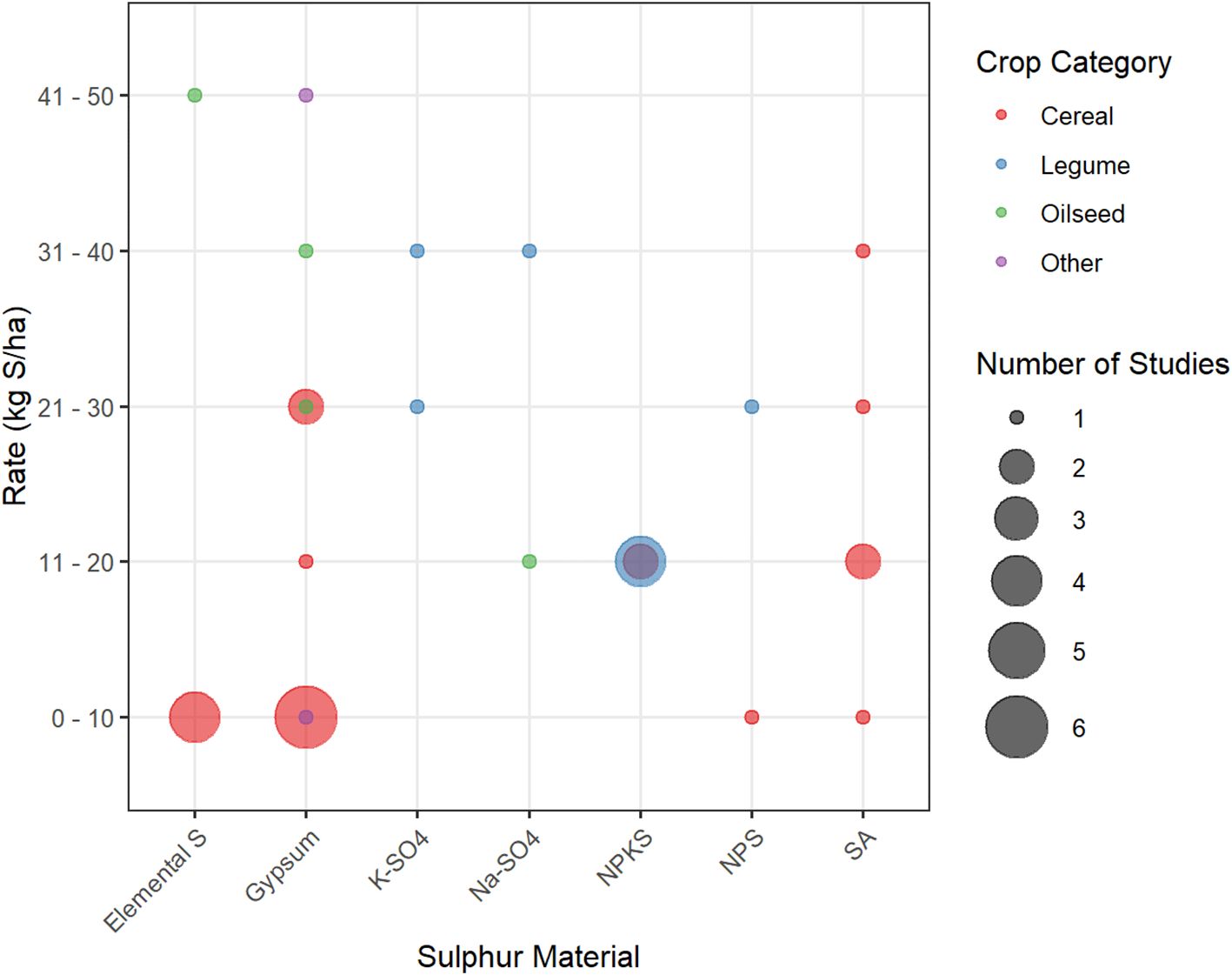

The analysis of S fertilisation practices across crop categories reveals distinct patterns in material selection and application rates (Figure 4). Cereals predominantly received low to moderate S rates (0–30 kg S/ha), with gypsum (CaSO4.2H2O) and SA as the most frequently applied materials. Notably, 71% of cereal-focused applications used ≤20 kg S/ha, often in compound fertilisers (NPKS, SA), suggesting integration with macronutrient management. Legumes were treated with higher S rates (21–40 kg S/ha), primarily via potassium sulphate and NPS blends, reflecting legume high S demands. Oilseeds exhibited the widest rate range (11–50 kg S/ha), with sodium sulphate, gypsum and elemental-S used at maximal doses (41–50 kg S/ha).

Figure 4. Reported use of sulphur amendments and their corresponding rates across various researched crop categories in Sub-Saharan Africa. Note. S, Sulphur; Na-SO4, Sodium sulphate; K-SO4, Potassium sulphate; SA, Ammonium sulphate.

The predominance of cereal-focused S research in SSA reflects their socio-economic importance as staple crops, particularly maize and rice, which dominate smallholder diets and cropping systems (Agyin-Birikorang et al., 2022a; Amuri et al., 2023; Bekele et al., 2022; Sirikare et al., 2015). However, this emphasis often neglects legumes and oilseeds, despite their critical roles in nutrition and soil health. The observed variations reflect crop-specific S demands and agronomic management. Cereals frequently received S applications via gypsum, NPKS or SA, which align with cost-effective, multi-nutrient strategies in staple crop systems.

The prevalence of ≤20 kg S/ha rates aligns with cereals’ moderate S uptake (10–15 kg S/ha) from the soil for grain protein synthesis (Scherer, 2001). These rates may suffice in systems where deep-rooted cereals access subsoil S reserves, reducing dependency on surface applications (Kihara et al., 2017). The yield variations underscore the critical role of S in optimising cereal productivity. The high percentage yield increase in maize at 21–30 kg S/ha aligns with studies linking S to enhanced nitrogen use efficiency and chlorophyll synthesis in C4 plants (Marschner, 2012). However, the variability in responses at identical S rates suggests the variation in genetic potential of crop varieties and the environmental limitations, such as nutrient and drought stresses.

3.4.2 Crop yield response to sulphur fertilisation

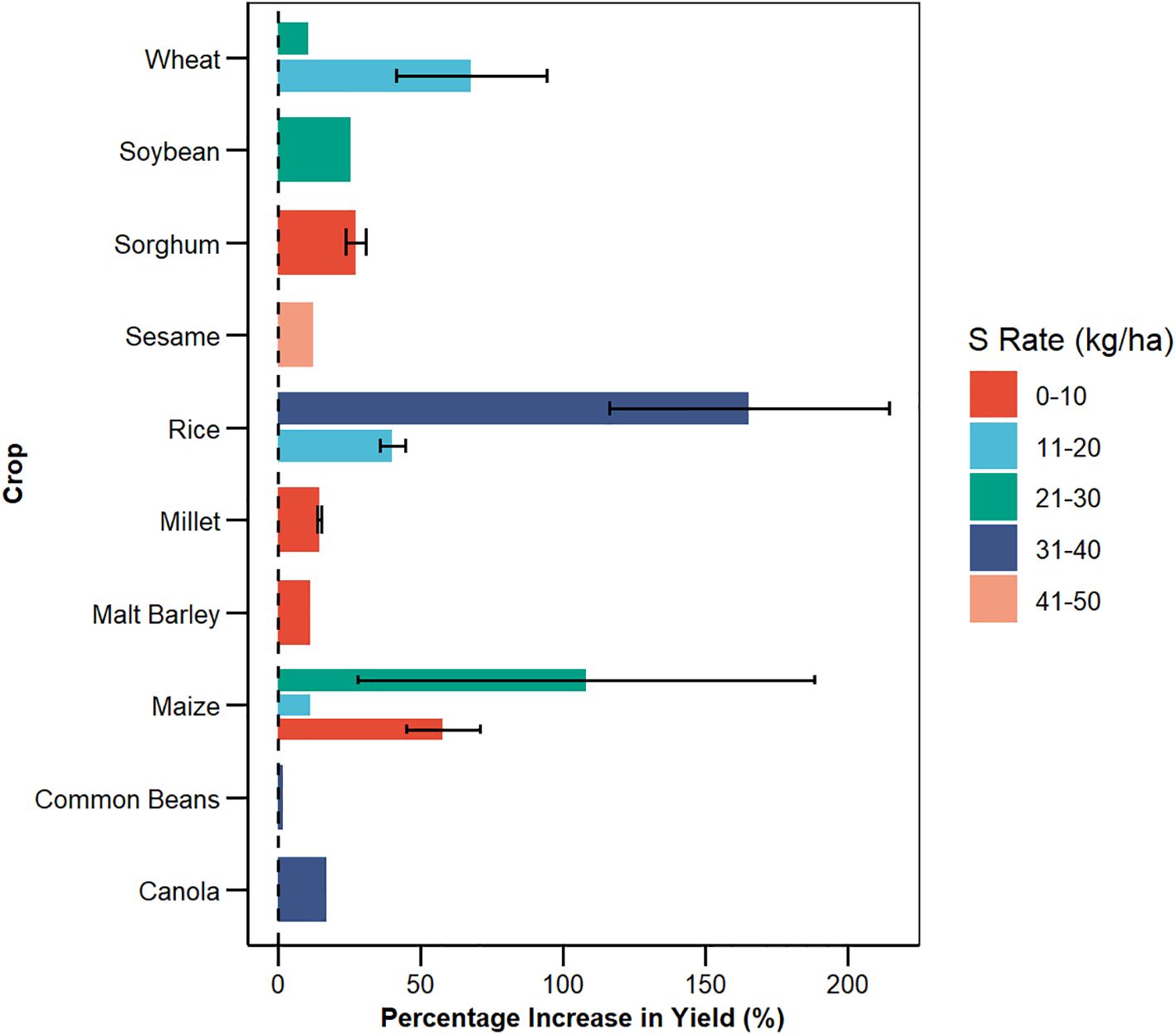

S application demonstrated notable yield improvements across various crops, though the magnitude of response varied by crop and application rate (Figure 5). Maize exhibited the most significant increases, with percentage yield gains ranging from 20.1% to 125.4% under 0–10 kg S/ha, and reaching up to 260.9% at 21–30 kg S/ha (Bekele et al., 2022; Friesen, 1991; Getinet et al., 2022; Malley et al., 2013; Sirikare et al., 2015). Wheat responded strongly at 11–20 kg S/ha, with increases of 59.7–79.9%, while rice showed gains of 26.0–61.7% at the same rate and a peak of 214.4% at 31–40 kg S/ha (Assefa et al., 2020; Habtegebrial and Singh, 2009). Sorghum and millet demonstrated moderate improvements of 23.6–30.7% and 13.9–15.2%, respectively, at 0–10 kg S/ha (Friesen, 1991). In contrast, legumes and oilseeds showed more modest responses. Soybean increased by 25.4% at 21–30 kg S/ha (Getachew et al., 2017), and canola, sesame, and common beans displayed minimal responses (17.2%, 12.5%, and 1.9%, respectively) even at higher rates (31–50 kg S/ha) (Daudi et al., 2016; Ngezimana and Agenbag, 2014; Tadesse and Dechassa, 2017). These results highlight crop-specific differences in response to S fertilisation.

Figure 5. Yield increase (%) of various crops under Sulphur treatments across different S application rate categories in Sub-Saharan Africa. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean yield increase.

Legumes required higher S rates (21–40 kg/ha), reflecting their demand for S-rich amino acids (cysteine, methionine) during nodulation and protein synthesis (Amir and Hacham, 2008; Haneklaus et al., 2007; Scherer, 2001). The preference for potassium sulphate and NPS blends suggests that targeted S supplementation alongside other nutrients such as potassium (K) and phosphorus (P), synergistically enhances root development and nitrogen fixation efficiency (Assefa et al., 2021; Marschner, 2012; Philp et al., 2021). Moreover, unlike acid-forming sources such as AS [(NH4)2SO4] and elemental S, potassium sulphate (K2SO4) does not significantly lower soil pH, reducing the risk of S-induced acidification. Notably, S applications in legume were kept below 40 kg S/ha might be a deliberate strategy to additionally protect soil pH (Kılıç and Sönmez, 2024). Oilseeds’ extreme application rate (up to 50 kg S/ha) underscores their sensitivity to S availability for lipid and glucosinolate synthesis (Ahmad et al., 2001; Scherer, 2001).

Economic and edaphic factors may further explain material choices. Gypsum’s dual role in S and Ca delivery makes it cost-effective for smallholders, while compound fertilisers (NPKS) are more suited to commercial farms prioritising operational efficiency. Conversely, the minimal use of elemental S may be due to its slow oxidation in soils, which makes it less effective for short-season crops (Degryse et al., 2018). Similarly, the sodium build-up from repeated applications that threaten soil structure may explain the low adoption of Sodium sulphate as an S source.

3.5 Effect of soil S levels and application rates on crop yield response

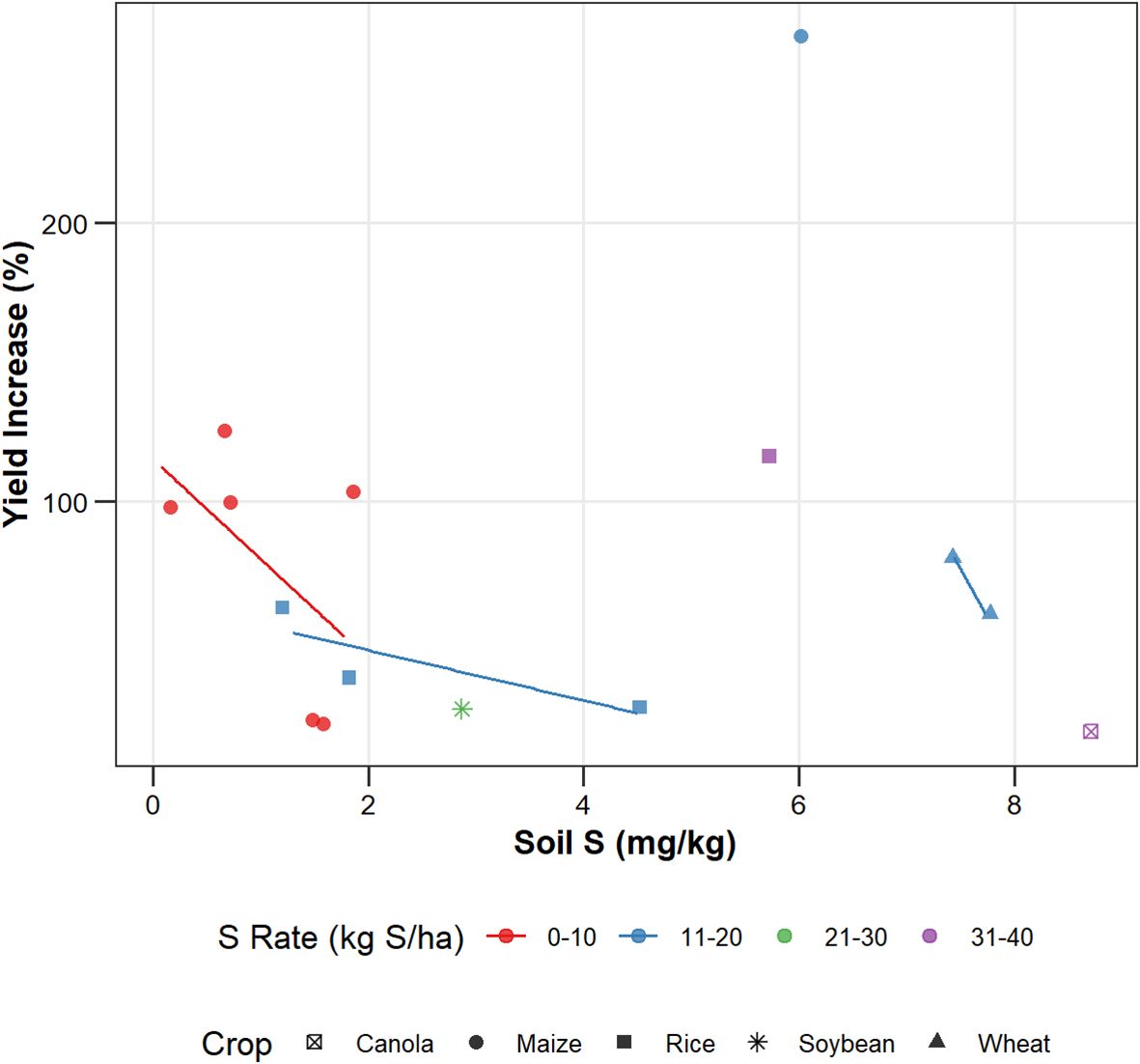

The relationship between soil S concentration and yield response was evaluated across six crops (maize, rice, wheat, soybean, canola, and soybean) under varying S application rates (Figure 6). Yield responses were most reported at soil S concentrations below 2.0 mg/kg, where treatments resulted in yield increases exceeding 50% in many cases. For example, in soils with <1.5 mg S/kg, maize achieved yield increases up to 125% at 0–10 kg S/ha, while rice responded with yield increases as high as 62% at 11–20 kg S/ha. Linear regression lines fitted for each S application rate and crop combination further confirmed that yield responses diminished as soil S levels increased. In contrast, crops grown in soils with medium S levels (>6 mg S/kg) exhibited minimal response, with per cent yield increases ranging from 17% to 60% for canola and wheat, respectively.

Figure 6. Crop yield response to sulphur (S) by soil S levels and application rate in diverse soils in Sub-Saharan Africa.

These results indicate that yield benefits from S fertilisation are crop- and site-specific, with the greatest yield response achieved under low soil S conditions. Excessive application in soils with S levels above 6.0 mg/kg yielded no significant advantage in some crops, reinforcing the need for site-specific fertiliser recommendations based on soil test results (Amuri et al., 2023; Bekele et al., 2022).

3.6 The environmental implications and the need for the management of sulphur containing amendments

The use of S-containing amendments and fertilisers such as Sub-Saharan Africa (SA) and elemental S is critical for improving soil fertility and crop yields. However, these amendments may have environmental side effects that must be carefully managed to prevent undesirable consequences. Among primary concerns associated with S amendments is soil and water acidification (Gerson and Hinckley, 2023). When elemental S is applied to the soil, it undergoes microbial oxidation to form sulfuric acid (Tabatabai, 1982), which can lower soil pH (Marschner, 2012; Mengel and Kirkby, 2001), potentially harming crops not adapted to acidic conditions and disrupting soil microbial communities (Gerson and Hinckley, 2023). In Tanzania, soil acidification is a substantial concern, particularly in cashew-growing regions where S is used to control powdery mildew disease (Dondeyne et al., 2001). This practice leads to reduced crop yields and soil fertility, especially in sandy soils with low buffering capacity (Dondeyne et al., 2001; Majule and Omollo, 2009). Acidification can lead to nutrient imbalances, affecting plant health and growth (Gerson and Hinckley, 2023; Mengel and Kirkby, 2001; Weil and Brady, 2016). According to Gilliam et al. (2020), extreme soil acidity can raise the solubility of heavy metals such as aluminium to a toxic level, and render the availability of phosphorus, further hampering plant development. Runoff from acidic soils can carry S material into water bodies, leading to the acidification of water ecosystems (Munodawafa, 2007). This can be observed in poorly managed soils where water erosion can easily carry away soil to nearby water bodies.

Studies have primarily examined the effects of nitrogen fertilisation on greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions like CO2, CH4, and N2O (Mosongo et al., 2022; Pelster et al., 2017). However, the particular influence of S fertilisation on GHG emissions in SSA has been less explored. In other areas, S fertilisation is recognised for its ability to regulate methane (CH4) emissions from wetland environments like flooded rice fields (Gauci et al., 2004). However, using these materials can lead to the release of S gases like SO2 upon oxidation, which play a significant role in climate change (Ward, 2009). The use of elemental S increases the solubility and availability of heavy metals such as iron (Fe) and cadmium (Cd), aiding plants in absorbing other metals like zinc (Zn), manganese (Mn), lead (Pb), and cadmium in maize (Safaa et al., 2013). This is attributed to the decrease in soil pH, which facilitates the solubility of these metals in the soil. This situation threatens food safety and human health, as toxic metals can accumulate in crops and infiltrate the food chain.

In the long run, applying elemental S and SA regularly without effective management can increase soil and environmental susceptibility to degradation, thereby reducing soil productivity. The use of these amendments should be tailored to agro-ecological zones and crops, based on the results of soil analysis, with application right fertiliser source, at the right rate, the right time, and in the right place (4R fertiliser stewardship) (Nalivata et al., 2017). S amendments should be sourced appropriately, ensuring high-quality sources free from impurities, and applied at the correct rates, timings, and placements in line with soil nutrient recommendations. Integrated soil fertility management, combining S with other nutrients and organic matter, can enhance long-term environmental and soil health by promoting soil biodiversity and structure, improving nutrient retention, and ultimately boosting agricultural production.

4 Conclusion and recommendation

This systematic review highlights the growing recognition of sulphur as a critical nutrient in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) crop production. The increasing number of researches, particularly from countries like Ethiopia, Nigeria and Tanzania, reflects rising S deficiencies in agricultural soils. S status across soil profiles shows clear vertical stratification, shaped by soil type, leaching, and texture, with generally higher concentrations in surface layers and highly variable subsoil. Studies should explicitly report the S extraction methods to improve data comparability and enhance the development of regionally relevant recommendations. Addressing infrastructural limitations through investment in laboratory facilities and technical training is crucial to support the adoption of new and advanced technologies for accurate and routine S analysis across SSA. Moreover, integrating S into broader nutrient management frameworks is an essential step toward sustainable agricultural intensification in SSA.

Consistent evidence indicates that S application significantly enhances crop yields, especially in cereals such as maize and rice, by improving nitrogen use efficiency and promoting photosynthetic activity. However, the varied responses among crop types underscore the need for crop-specific and site-specific S management strategies. The widespread use of S-containing amendments, including elemental S and SA, raises concerns about soil acidification, heavy metal mobilisation, and potential environmental degradation. To balance productivity and sustainability, S management must follow 4R nutrient stewardship (right source, rate, time, and place) and be integrated into broader soil fertility frameworks. Site-specific strategies that combine S with organic inputs and other nutrients are essential to enhance soil health, crop productivity, and environmental safety across SSA.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MM: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis. NA: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RW: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Food Shot Global Ground Breaker Prize.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fagro.2025.1656622/full#supplementary-material

References

Abebe A., Abera G., and Beyene S. (2018). Assessment of the limiting nutrients for wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) growth using Diagnosis and Recommendation Integrated System (DRIS). Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 49, 2653–2663. doi: 10.1080/00103624.2018.1526951

Abebe T. N. and Beyene S. (2021). Growth limiting nutrient(s) and their effects on the yield and nutrient uptake of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) in nitisols, southern Ethiopia. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 11, 7–20. doi: 10.7176/JEES/11-12-02

Acquaye D. K. and Beringer H. (1989a). Sulfur in Ghanaian soils: I. Status and distribution of different forms of sulfur in some typical profiles. Plant Soil 113, 197–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02280181

Acquaye D. K. and Beringer H. (1989b). Sulfur in Ghanain soils: II. Assessment of sulfur availability status of the surface soils. Plant Soil 113, 205–211. doi: 10.1007/BF02280182

Acquaye D. K. and Kang B. T. (1987). Sulfur status and forms in some surface soils of Ghana. Soil Sci. 144, 43–52. doi: 10.1097/00010694-198707000-00008

Adetunji M. T. (1992). Effect of lime and phosphorus application on sulfate-adsorption capacity of south-western Nigerian soils. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 62, 150–152.

Agyin-Birikorang S., Adu-Gyamfi R., Tindjina I., Fugice J., Dauda H. W., Singh U., et al. (2022a). Ameliorating incongruent effects of balanced fertilization on maize productivity in strongly acid soils with liming. J. Plant Nutr. 45, 2597–2610. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2022.2064293

Agyin-Birikorang S., Boubakry C., Kadyampakeni D. M., Adu-Gyamfi R., Chambers R. A., Tindjina I., et al. (2024). Synergism of sulfur availability and agronomic nitrogen use efficiency. Agron. J. 116, 753–764. doi: 10.1002/agj2.21535

Agyin-Birikorang S., Tindjina I., Fugice J. Jr., Dauda H. W., Issahaku A. R., Iddrissu M., et al. (2022b). Optimizing sulfur fertilizer application rate for profita ble maize production in the savanna agroecological zones of Northern Ghana. J. Plant Nutr. 45, 2315–2331. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2022.2063740

Ahmad A., Khan I., Abdin M., Abrol Y., and Srivastava G. (2001). Lipid biosynthesis in rapeseed as influenced by sulphur nutrition. Plant Nutrition: Food Secur. Sustainability Agro-Ecosystems through Basic Appl. Res. 92, 334–335. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47624-X_161

Altaye A., Tena W., and Melese A. (2022). Effects of mesorhizobium inoculation, phosphorus and sulfur application on nodulation, growth and yield of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Ethiopian J. Appl. Sci. Technology. 13, 11–23.

Al-Worafi Y. M. (2023). “Malnutrition in Developing Countries.” In Al-Worafi Y. M. Ed. Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries: Education, Practice, and Research, vol. 18, 1–19 (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-74786-2_296-1

Amir R. and Hacham Y. (2008). Methionine metabolism in plants. Sulfur: A Missing Link between Soils Crops Nutr. 50, 251–279. doi: 10.2134/agronmonogr50.c16

Amuri N. A., Semoka J. M. R., Weil R., Mzimbiri M., Gatere L., Palm C., et al. (2023). Validating SoilDoc kit for site-specific fertilizer recommendations for maize production in Tanzania. Agronomy Journal. Mach. Learn. Agric. 116(6), 2641–2656. doi: 10.1002/agj2.21472

Appiah M. and Ahenkorah Y. (1989). Determination of available sulfate in some soils of Ghana using 5 extraction methods. Biol. Fertility Soils 8, 80–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00260521

Assefa S., Haile W., and Tena W. (2021). Effects of phosphorus and sulfur on yield and nutrient uptake of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) on Vertisols, North Central, Ethiopia. Heliyon 7, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06614

Assefa S., Shewangizaw B., and Kassie K. (2020). Response of Bread Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) to Sulfur Fertilizer Rate under Balanced Fertilization at Basona Warena District of North Shewa Zone of Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 51, 2606–2615. doi: 10.1080/00103624.2020.1845361

Bankole G. O., Sakariyawo O. S., Odelana T. B., Aghorunse A. C., Adejuyigbe C. O., and Azeez J. O. (2022). Sulfur fractions, distribution and sorption characteristics in some soils of ogun state, southwestern Nigeria. Commun. In Soil Sci. And Plant Anal. 53, 1887–1902. doi: 10.1080/00103624.2022.2069798

Bekele I., Lulie B., Habte M., Boke S., Hailu G., Mariam E. H., et al. (2022). Response of maize yield to nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and sulphur rates on Andosols and Nitisols in Ethiopia. Exp. Agric. 58, 1–17. doi: 10.1017/S0014479722000035

Buri M., Masunaga T., and Wakatsuki T. (2000). Sulfur and zinc levels as limiting factors to rice production in West Africa lowlands. GEODERMA 94, 23–42. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7061(99)00076-2

Cassou E. (2018). Field burning (Washington, DC: World Bank). Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/29504 (Accessed March 09, 2024).

Das S., Pendall E., Malik A. A., Nannipieri P., and Kim P. J. (2024). Microbial control of soil organic matter dynamics: Effects of land use and climate change. Biol. Fertility Soils 60, 1–3. doi: 10.1007/s00374-023-01788-4

Daudi H., Mponda O., and Mkandawile C. (2016). Effects of sulphur and lime application on yield of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) in southern Tanzania. J. Biol. 6(14), 5.

Degryse F., da Silva R. C., Baird R., Beyrer T., Below F., and McLaughlin M. J. (2018). Uptake of elemental or sulfate-S from fall- or spring-applied co-granulated fertilizer by corn—A sta ble isotope and modeling study. Field Crops Res. 221, 322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2017.07.015

de Mello Prado R. (2021a). “Mineral nutrition of tropical plants,” in Mineral nutrition of tropical plants (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-71262-4

de Mello Prado R. (2021b). “Sulfur,” in Mineral nutrition of tropical plants. Ed. de Mello Prado R. (Springer, Cham: Springer International Publishing), 99–112. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-71262-4_5

Dondeyne S., Ngatunga E. L., Cools N., Dondeyne S., Deckers J. A., and Merckx R. (2001). Buffering capacity of cashew soils in South Eastern Tanzania. Soil Use Manage. 17, 155–162. doi: 10.1079/SUM200167

Ethio SIS (Ethiopia Soil Information System) (2014). Soil fertility status and fertilizer recommendation atlas for tigray regional state (Ethiopia: Ethiopia Soil Information System).

Ezenwa I. (1994). Early growth of leucaena at different levels of sulfur and phosphorus application. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 25, 2639–2648. doi: 10.1080/00103629409369214

Fischer S., Hilger T., Piepho H.-P., Jordan I., Karungi J., Towett E., et al. (2020). Soil and farm management effects on yield and nutrient concentrations of food crops in East Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 716, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137078

Friesen D. (1991). Fate and efficiency of sulfur fertilizer applied to food crops in west africa. Fertilizer Res. 29, 35–44. doi: 10.1007/BF01048987

Gauci V., Matthews E., Dise N., Walter B., Koch D., Granberg G., et al. (2004). Sulfate suppression of the wetland methane source in the 20th and 21st centuries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America 101, 12583–12587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404412101

Gerson J. R. and Hinckley E.-L. S. (2023). It is time to develop sustainable management of agricultural sulfur. Earth’s Future 11, e2023EF003723. doi: 10.1029/2023EF003723

Getachew Z., Abera G., and Beyene S. (2017). Rhizobium inoculation and sulphur fertilizer improved yield, nutrients uptake and protein quality of soybean (Glysine max L.) varieties on Nitisols of Assosa area, Western Ethiopia. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 11, 123–132. doi: 10.5897/AJPS2017.1519

Getinet H., Selassie Y. G., and Balemi T. (2022). Yield Response and Nutrient use Efficiencies of Maize (Zea mays L.) As Determined through Nutrient Omission trial in Jimma Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 7, 30–42. doi: 10.20372/jaes.v7i1.858

Gilliam F. S., Adams M. B., and Peterjohn W. T. (2020). Response of soil fertility to 25 years of experimental acidification in a temperate hardwood forest. J. Environ. Qual. 49, 961–972. doi: 10.1002/jeq2.20113

Habtegebrial K. and Singh B. R. (2009). Response of wheat cultivars to nitrogen and sulfur for crop yield, nitrogen use efficiency, and protein quality in the semiarid region. J. Plant Nutr. 32, 1768–1787. doi: 10.1080/01904160903152616

Haneklaus S., Bloem E., Schnug E., de Kok L. J., and Stuleni I. (2007). “Sulfur,” in Handbook of plant nutrition (USA: CRC Press), 117632.

Harou A. P., Madajewicz M., Michelson H., Palm C. A., Amuri N., Magomba C., et al. (2022). The joint effects of information and financing constraints on technology adoption: Evidence from a field experiment in rural Tanzania. J. Dev. Econ 155, 102707. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102707

Havlin J. L. and Heiniger R. (2020). Soil fertility management for better crop production. Agronomy 10, 1349. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10091349

Havlin J. L., Tisdale S. L., Nelson W. L., and Beaton J. D. (2017). “Sulfur, calcium, and magnesium,” in Soil fertility and fertilizers: An introduction to nutrient management, 8th ed (India: Pearson), 243–256.

Hemesh K. (2020). Role of sulphur in cereal crops: A review. J. Pharmacognosy Phytochem. 9, 1864–1869. doi: 10.22271/phyto.2020.v9.i6aa.13220

Horneck S., Sullivan D. M., Owen J. S., and Hart J. M. (2011). Soil Test Interpretation Guide (No. EC1478; p. 12) (Oregon State University). Available online at: https://extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/default/files/catalog/auto/EC1478 (Accessed March 10, 2024).

Hutton B., Salanti G., Caldwell D. M., Chaimani A., Schmid C. H., Cameron C., et al. (2015). The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: Checklist and explanations. Annals of Internal Medicine, 162(11), 777–784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385

Itanna F. (2005). Sulfur distribution in five Ethiopian Rift Valley soils under humid and semi-arid climate. J. Of Arid Environments 62, 597–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2005.01.010

Jaliya M. M., Sani B. M., Rilwanu A. Y., Ahmed I., and Aminu I. S. (2014). Uptake of nitrogen and sulfur as influenced by interaction between maize variety and nitrogen fertilizer at samaru, zaria. Nigerian J. Sci. Res. 13, 49–54.

Johnson J.-M., Ibrahim A., Dossou-Yovo E. R., Senthilkumar K., Tsujimoto Y., Asai H., et al. (2023). Inorganic fertilizer use and its association with rice yield gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Global Food Secur. 38, 100708. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2023.100708

Kalonga J., Mtei K., Massawe B., Kimaro A., and Winowiecki L. A. (2024). Characterization of soil health and nutrient content status across the North-East Maasai Landscape, Arusha Tanzania. Environ. Challenges 14, 100847. doi: 10.1016/j.envc.2024.100847

Kang B. T., Okoro E., Acquaye D., and Osiname O. A. (1981). Sulfur status of some Nigerian soils from the savanna and forest zones. Soil Sci. 132, 220–227. doi: 10.1097/00010694-198109000-00005

Ketterings Q., Miyamoto C., Mathur R. R., Dietzel K., and Gami S. (2011). A comparison of soil sulfur extraction methods. Soil Sci. Soc. America J. 75, 1578–1583. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2010.0407

Kihara J., Sileshi G. W., Nziguheba G., Kinyua M., Zingore S., and Sommer R. (2017). Application of secondary nutrients and micronutrients increases crop yields in sub-Saharan Africa. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 37, 25. doi: 10.1007/s13593-017-0431-0

Kılıç F. N. and Sönmez O. (2024). The Effect of Different Sulphur Sources Applied at Various Rates on Soil pH. Turkish J. Agric. - Food Sci. Technol. 13, 59–64. doi: 10.24925/turjaf.v13i1.59-64.7256

Kwari J. D., Kamara A. Y., Ekeleme F., and Omoigui L. O. (2009). Relation of yields of soybean and maize to sulphur, zinc and copper status of soils under intensifying cropping systems in the tropical savannas of north-east Nigeria. J. Food Agric. Environ. 7, 129–133.

Landon J. R. (1991). Booker tropical soil manual: A handbook for soil survey and agricultural land evaluation in the tropics and subtropics (1st ed.) (Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781315846842

Lehmann J., Bossio D. A., Kögel-Knabner I., and Rillig M. C. (2020). The concept and future prospects of soil health. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 544–553. doi: 10.1038/s43017-020-0080-8

Lelago A., Mamo T., Haile W., and Shiferaw H. (2016). Assessment and mapping of status and spatial distribution of soil macronutrients in kambata tembaro zone, southern Ethiopia. Adv. Plants Agric. Res. 4, 1–14. doi: 10.15406/apar.2016.04.00144

Majule A. and Omollo J. (2009). The performance of maize crop during acid amelioration with organic residues in soils of Mtwara, Tanzania. Tanzania J. Sci. 34. doi: 10.4314/tjs.v34i1.44285

Malley Z. J. U., Mmari W. N., Marandu A., Ngailo J., and Mzimbiri M. (2013). “Response of maize crop to Sulphur in Ruvuma Region, Tanzania,” in Joint proceedings of the 27th soil science society of east africa and the 6th african soil science society, Nakuru, Kenya: Joint proceedings of the 27th Soil Science Society of East Africa and the 6th African Soil Science Society 197–202. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319230813 (Accessed February 19, 2024).

Marschner H. (2012). Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (3rd ed.) (Elsevier Science). Available online at: https://books.google.co.tz/books?id=_a-hKcXXQuAC (Accessed August 26, 2023).

Mengel K. and Kirkby E. A. (2001). “Principles of plant nutrition,” in Principles of plant nutrition (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands). doi: 10.1007/978-94-010-1009-2

Michelson H. (2017). Variable soils, variable fertilizer quality, and variable. Prospects. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 10, 194008291772066. doi: 10.1177/1940082917720661

Mosongo P. S., Pelster D. E., Li X., Gaudel G., Wang Y., Chen S., et al. (2022). Greenhouse gas emissions response to fertilizer application and soil moisture in dry agricultural uplands of central Kenya. Atmosphere 13, 463. doi: 10.3390/atmos13030463

Munodawafa A. (2007). Assessing nutrient losses with soil erosion under different tillage systems and their implications on water quality. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 32, 1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.pce.2007.07.033

Nalivata P., Kibunja C., Mutegi J., Tetteh F., Tarfa B., Dicko M., et al. (2017). “Integrated soil fertility management in sub-saharan africa,” in Fertilizer use optimization in sub-saharan africa. Eds. Wortmann C. and Sones K. (Nairobi, Kenya: CABI). doi: 10.1079/9781786392046.0000

Narayan O. P., Kumar P., Yadav B., Dua M., and Johri A. K. (2022). Sulfur nutrition and its role in plant growth and development. Plant Signaling Behav. 18(1), 12. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2022.2030082

Ngezimana W. and Agenbag G. A. (2014b). The effect of nitrogen and sulphur on the grain yield and quality of canola (Brassica napus L.) grown in the Western Cape, South Africa. South Afr. J. Plant Soil 31, 69–75. doi: 10.1080/02571862.2014.907451

Ngezimana W. and Agenbag G. A. (2015). The effect of nitrogen and sulphur on the agronomical and water use efficiencies of canola (Brassica napus L.) grown in selected localities of the Western Cape province, South Africa. South Afr. J. Plant Soil 32, 71–76. doi: 10.1080/02571862.2014.988302

Ojeniyi S. O. and Kayode G. O. (1993). Response of maize to copper and sulfur in tropical regions. J. Agric. Sci. 120, 295–299. doi: 10.1017/S0021859600076450

Omenda P. A. (2011). “The Geology and Geothermal Activity of the East African Rift [Geothermal activity, East African Rift],” in Exploration for Geothermal Resources(Naivasha, Kenya). Available online at: https://www.academia.edu/64287051/The_geology_and_geothermal_activity_of_the_East_African_Rift (Accessed May 20, 2025).

Onianwa P. C. and Babajide A. O. (1993). Sulphate-sulphur levels of topsoils related to atmospheric sulphur dioxide pollution. Environ. Monit. Assess. 25, 141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00549135

Opio R., Mugume I., and Nakatumba-Nabende J. (2021). Understanding the trend of NO2, SO2 and CO over east africa from 2005 to 2020. Atmosphere 12(10), 1283. doi: 10.3390/atmos12101283

Page M. J., Moher D., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D., et al. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160

Pelster D., Rufino M., Rosenstock T., Mango J., Saiz G., Diaz-Pines E., et al. (2017). Smallholder farms in eastern African tropical highlands have low soil greenhouse gas fluxes. Biogeosciences 14, 187–202. doi: 10.5194/bg-14-187-2017

Peverill K. I., Sparrow L. A., Reuter D. J., and Douglas J. (1999). Soil analysis: An interpretation manual (CSIRO). Available online at: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130000795100273024 (Accessed May 27, 2025).

Philp J. N. M., Cornish P. S., Te K. S. H., Bell R. W., Vance W., Lim V., et al. (2021). Insufficient potassium and sulfur supply threaten the productivity of perennial forage grasses in smallholder farms on tropical sandy soils. Plant And Soil 461, 617–630. doi: 10.1007/s11104-021-04852-w

Ramaswwamyreddy S. and Basavaraju P. (2022). “Effect of water and soil quality on crop productivity,” in Clean water and sanitation. Eds. Leal Filho W., Azul A. M., Brandli L., Lange Salvia A., and Wall T. (Springer, Cham: Springer International Publishing), 1–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-70061-8_65-1

Safaa M., Khaled S. M., and Hanan S. S. (2013). “Effect of Elemental Sulphur on Solubility of Soil Nutrients and Soil Heavy Metals and Their Uptake by Maize Plants. J. Am. Sci. 9, 19–24.

Scherer W. H. (2001). Sulphur in crop production—Invited paper. Eur. J. Agron. 14, 81–111. doi: 10.1016/S1161-0301(00)00082-4

Scott N., Delport D., Hainsworth S., Pearson R., Morgan C., Huang S., et al. (2020). Ending malnutrition in all its forms requires scaling up proven nutrition interventions and much more: A 129-country analysis. BMC Med. 18, 356. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01786-5

Sharma R. K., Cox M. S., Oglesby C., and Dhillon J. S. (2024). Revisiting the role of sulfur in crop production: A narrative review. J. Agric. Food Res. 15, 101013. doi: 10.1016/j.jafr.2024.101013

Sirikare N. S., Marwa E. M., Semu E., and Naramabuye F. X. (2015). Liming and sulfur amendments improve growth and yields of maize in Rubona Ultisol and Nyamifumba Oxisol. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B — Soil Plant Sci. 65, 713–722. doi: 10.1080/09064710.2015.1052547

Tabatabai M. A. (1982). “Sulfur,” in Methods of soil analysis: part 2 chemical and microbiological properties, 2nd ed.Page A. L. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd), 501–538. doi: 10.2134/agronmonogr9.2.2ed.c28

Tadesse N. and Dechassa N. (2017). Effect of nitrogen and sulphur application on yield components and yield of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in eastern Ethiopia. Acad. Res. J. Agric. Sci. Res. 5, 77–89. doi: 10.14662/ARJASR2016.053

Tehulie N. and Yimer Z. (2021). Effects of blended fertilizer rates on growth, yield and quality of malt barley (Hordeum distichum L.) varieties at mekdela district, south wollo, Ethiopia. J. Gen. Virol. 10, 32–44. doi: 10.37591/RRJoB

Telman W. and Dietz K.-J. (2019). Thiol redox-regulation for efficient adjustment of sulfur metabolism in acclimation to abiotic stress. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 4223–4236. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz118

Tsujimoto Y., Inusah B., Katsura K., Fuseini A., Dogbe W., Zakaria A. I., et al. (2017). The effect of sulfur fertilization on rice yields and nitrogen use efficiency in a floodplain ecosystem of northern Ghana. Field Crops Res. 211, 155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2017.06.030

Udayana S. K., Singh P., Maverick J., and Roy A. (2021). Sulphur: A boon in agriculture. Pharma Innovation J. 10, 912–921.

Ulén B. (2020). Nutrient leaching driven by rainfall on a vermiculite clay soil under altered management and monitored with high-frequency time resolution. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B — Soil Plant Sci. 70, 392–403. doi: 10.1080/09064710.2020.1750686

Uloro Y. and Mengel K. (1994). Response of ensete (ensete-ventricosum W) to mineral fertilizers in southwest Ethiopia. Fertilizer Res. 37, 107–113. doi: 10.1007/BF00748551

Watkinson J. H. and Kear M. J. (1996). Sulfate and mineralisable organic sulfur in pastoral soils of New Zealand. II*. A soil test for mineralisable organic sulfur. Soil Res. 34, 405–412. doi: 10.1071/sr9960405

Weil R. R. and Brady N. C. (2016). The nature and properties of soils. Pearson. Available online at: https://books.google.co.tz/books?id=42DzjwEACAAJ.

Weil R. R. and Mughogho S. K. (2000). Sulfur nutrition of maize in four regions of Malawi. Agron. J. 92, 649–656. doi: 10.2134/agronj2000.924649x

Keywords: agricultural soils, crop yield response, nutrient management, nutrient stewardship (4R), soil fertility, Sub-Saharan Africa, sulphur application rates, sulphur deficiency

Citation: Moshi MM, Amuri NA and Weil RR (2025) Sulphur nutrition management in Sub-Saharan Africa crop production: a systematic review. Front. Agron. 7:1656622. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2025.1656622

Received: 30 June 2025; Accepted: 10 November 2025; Revised: 08 September 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Durgesh K. Jaiswal, Graphic Era University, IndiaReviewed by:

Khuong Nguyen Quoc, Can Tho University, VietnamDr. Knight Nthebere, National University of Lesotho, Lesotho

Copyright © 2025 Moshi, Amuri and Weil. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martin M. Moshi, bWFydGluLm1vc2hpQHN1YS5hYy50eg==

Martin M. Moshi

Martin M. Moshi Nyambilila A. Amuri

Nyambilila A. Amuri Ray R. Weil

Ray R. Weil