- 1Department of Entomology, University of Georgia, Tifton, GA, United States

- 2Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

- 3Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria

- 4Department of Zoology and Entomology, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

- 5Department of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Lincoln University of Missouri, Jefferson, MO, United States

- 6Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Design, North Carolina A&T State University, Greensboro, NC, United States

- 7Department of Entomology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, United States

- 8Department of Horticulture, University of Georgia, Tifton, GA, United States

- 9International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology, Nairobi, Kenya

- 10Department of Life Science, South Eastern Kenya University, Kitui, Kenya

Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) is a globally destructive pest that is particularly damaging to tropical and subtropical agricultural systems. The sap-feeding behavior, coupled with its rapid reproduction, causes substantial direct crop damage and facilitates the transmission of over 350 plant viruses, leading to significant yield losses in crops such as tomato, potato, cabbage, cotton and soybean among others. Conventional control strategies rely heavily on synthetic insecticides; however, their intensive use has led to the emergence of insecticide resistance in B. tabaci biotypes, environmental degradation, and detrimental effects on non-target organisms. Biological control using natural enemies, including predators, parasitoids, and entomopathogens, serves as a sustainable option within several integrated pest management (IPM) frameworks. In this review, the effectiveness of key biocontrol agents such as predatory beetles (Delphastus catalinae), mirid bugs (Macrolophus pygmaeus), parasitoid wasps (Encarsia formosa), and entomopathogens in controlling B. tabaci populations is evaluated. It highlights implementation challenges, including environmental sensitivity, host specificity, cost, scalability, and insecticide compatibility. Further, future directions are discussed with a focus on genetic and ecological innovations, improved delivery mechanisms for entomopathogens, climate-resilient biocontrol agents, and farmer-centric training and policy support. Promoting these multidisciplinary strategies is crucial for enhancing long-term pest suppression while preserving ecological communities and the integrity of agricultural landscapes by reducing reliance on synthetic insecticides.

1 Introduction

The whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), specifically the Middle East-Asia Minor 1 (MEAM1) known as biotype B (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), is a cryptic species, globally distributed and a highly economically destructive pest that affects a wide range of agronomic, vegetable, and horticultural crops. It poses a significant threat to agricultural plants productivity, particularly in cotton and vegetable systems, due to both direct damage and its role as a virus vector (Oliveira et al., 2001; Wei et al., 2006; Prompiboon et al., 2010; Bowers et al., 2020; Abubakar et al., 2022). Bemisia tabaci is a polyphagous and multivoltine sap-feeding insect that can feed on more than 1,000 plant species, ensuring its survival and year-round proliferation across various agroecosystems (Oliveira et al., 2001; Simmons et al., 2008; Li et al., 2011).

Its capacity to utilize diverse plant resources throughout the year contributes to the persistence and stability of populations (Abd-Rabou and Simmons, 2010; Barman et al., 2022). Notably, B. tabaci is one of the most prolific virus vectors, capable of transmitting over 350 plant viruses, including members of the genera Carlavirus, Begomovirus, Ipomovirus, Crinivirus, and Torradovirus (Brown, 1992; Wei et al., 2006; De Barro et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2014). This viral transmission ability leads to significant yield losses in crops such as potato, tomato, okra, soybean, and cassava, with Begomovirus infections alone causing yield reduction of up to 100% (Taggar and Singh, 2020; Sani et al., 2020; Srinivasan et al., 2024). Threshold levels, such as four nymphs per leaf or one adult per seedling tray, can result in economic losses for tomato growers (Abubakar et al., 2022). The biological complexity of B. tabaci further complicates its management. It is now known that B. tabaci consists of at least 43 different cryptic species that require using mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (COI) markers as well as morphological methods for identification, as they look very similar (de Moya et al., 2019; Peng et al., 2025). Each species differ in host preference, virus transmission efficiency, insecticide resistance, and response to biological control (de Moya et al., 2019; Abubakar et al., 2022).

Bemisia tabaci was initially identified as a tobacco pest in Greece in 1889 (Zafar et al., 2016), but it gained global recognition as a major pest following the introduction of the biotype B into the southwestern United States through the ornamental plant trade in the 1980s. Since then, it spread across the Middle East, Southeast Asia, East Asia, North America, Central America, South America, and Africa, establishing itself as a globally invasive pest (Gerling et al., 2001; Oliveira et al., 2001; Peng et al., 2025). Warm climates and abundant host availability contribute to explosive population growth, which can lead to severe crop damage through phloem-feeding, honeydew secretion, and viral transmission. Both nymphs and adults inflict damage by extracting plant sap and excreting sugary honeydew, supporting the growth of sooty mold which interferes with photosynthesis, reduces fruit quality, and marketability of the produce. Moreover, B. tabaci introduces salivary enzymes during feeding that modulate plant physiological processes, resulting in chlorosis, leaf curling, stunted growth, and deformation of fruits (Tan et al., 2016; Hasanuzzaman et al., 2016).

Management of B. tabaci has primarily relied on synthetic insecticides, though insecticide resistance has emerged as a significant challenge, highlighting the need for alternative control strategies (Yang et al., 2013; Perier et al., 2022). Overreliance on insecticides for management has also led to a resurgence of secondary pest populations, environmental pollution, and non-target effects, which include harm to pollinators and natural enemies (Horowitz et al., 2005; Ou et al., 2019; Zhang et al, 2020a). The high cost of insecticides further limits effective control for small farmers, which contributes to persistent B. tabaci infestations and reduced crop productivity. Hence, biological control has gained renewed attention as a cornerstone of sustainable pest control through integrated pest management (IPM). The use of natural enemies including predators, parasitoids, and entomopathogenic fungi, bacteria, and viruses offers an ecologically sound alternative to synthetic insecticides. These natural enemies can suppress B. tabaci populations through parasitism, predation, and pathogen induced mortality, thereby reducing pest pressure with minimal adverse side effects compared to synthetic insecticides (Shah et al., 2015; Hasanuzzaman et al., 2016; Vafaie et al., 2020; Abubakar et al., 2022; Shapiro-Ilan and Lewis, 2024). Integrating natural enemies into IPM programs can provide long-term, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly control of B. tabaci. However, challenges concerning their establishment, effectiveness under field conditions and compatibility with other control strategies exist (Ou et al., 2019; Pirzadfard et al., 2020). This review critically examines the role of predators, parasitoids, and entomopathogens, in the management of B. tabaci, highlighting their successes, limitations, and potential for integration into comprehensive IPM strategies.

2 Keywords used in collecting peer-reviewed literature

This review summarizes existing research on the role of entomopathogens, parasitoids, and predators as biological control agents of B. tabaci. A comprehensive literature search was carried out across multiple academic databases including PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Web of Science, using keywords like “B. tabaci biocontrol,” “predators,” “parasitoids,” “IPM programs,” “environmental variability to B. tabaci,” “B. tabaci virus as well as vectors,” “synthetic insecticides,” “pest ecological niche,” and “entomopathogens to B. tabaci,” to identify relevant peer-reviewed articles and scientific reports. The selected studies were screened for relevance based on their focus on whitefly biology, pest management, and the use and/or evaluation of natural enemies within agroecosystems. The relevant literature was then thematically organized, with key findings synthesized into the major categories discussed in the subsequent sections.

3 Natural enemies in Bemisia tabaci management

Biological control is a fundamental component of IPM that involves the use of natural enemies, such as predators, parasitoids, and beneficial microorganisms, to regulate pest populations through conservation, augmentation, or classical introduction in agroecosystems (Naranjo, 2001, Naranjo, 2007; Dainese et al., 2017; Ou et al., 2019). This method of control has deep evolutionary roots; having the natural enemies’ prey on and parasitize pests for over 500 million years, thus shaping ecological interactions across terrestrial habitats (Naranjo and Ellsworth, 2009; Vacante and Bonsignore, 2017). Even without direct human intervention, biological control is a pervasive and essential ecological process that can offer substantial economic benefits in agricultural settings.

Entomopathogenic microorganisms such as fungi, bacteria, viruses, nematodes, and microsporidia play a key role in the natural regulation of insect populations (Wei et al., 2006; Khan et al., 2012; Deka et al., 2021; Legarrea et al., 2022b) and are often highly specific to pest species. Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF), particularly those in the Entomophthoromycotina subphylum, demonstrate a wide breadth of host specificity. While these fungi can infect a variety of insect species, their host specificity can vary greatly depending on the environmental conditions and the pathogen’s ecological niche (Cuthbertson et al., 2005a, Cuthbertson et al., 2007; Sacco and Hajek, 2023). This specificity allows them to effectively target pest species while minimizing effects on non-target organisms, making them invaluable for integrated pest management (IPM) strategies. Arthropod-associated microbes have increasingly been recognized for their potential in biocontrol, with interactions between pests and microbial pathogens offering promising strategies for B. tabaci suppression (Naranjo, 2001; Deka et al., 2021; Li et al., 2024). Highly specific interactions between pests and pathogen enemies contrast with broad-spectrum insecticide applications that kill pest and non-pest species as well as eliminating beneficial organisms, destabilizing ecosystem balance and reducing biodiversity (Dainese et al., 2017; Vacante and Bonsignore, 2017).

Improving natural enemy populations through habitat manipulation and/or augmentative releases has emerged as a key strategy for restoring ecological balance and minimizing insecticides use. This approach not only improves biological control but also promotes sustainable pest management by fostering resilient ecosystems. Habitat manipulation, such as the strategic use of cover crops, floral resources, and refuge areas, can significantly enhance the abundance and diversity of natural enemies, thereby improving pest control efficacy (Naranjo, 2001; Venzon et al., 2006; Naranjo and Ellsworth, 2009; Gurr et al., 2017; Bowers et al., 2020). Furthermore, augmentative releases of natural enemies have shown promise in enhancing biological control, particularly in regions where pest pressures are high. For example, in South America, studies demonstrated the effectiveness of habitat manipulation strategies in improving conservation biological control, offering a more sustainable alternative to conventional pest control methods and contributing to the restoration of ecological balance in agroecosystems (Peñalver-Cruz et al., 2019).

Predators, particularly arthropods like mites in the family Phytoseiidae, are widely used in augmentative biological control due to their generalist feeding behavior, short reproduction times, and rapid life cycles. Predatory mites account for over 60% of the global arthropod natural enemy sales (van Lenteren et al., 2017; Knapp et al., 2018; Kheirodin et al., 2020). However, thier effectiveness is limited due to plant morphological traits, like glandular trichomes on tomato plants, that release defensive exudates that hinder predator mobility and reduce survival (Schuurink and Tissier, 2019; Legarrea et al., 2022a). Despite these limitations, species such as Amblyseius herbicolus (Chant) (Acari: Phytoseiidae) and A. tamatavensis Blommers (Acari: Phytoseiidae) have shown significant predatory activity against B. tabaci (Cavalcante et al., 2016; Barbosa et al., 2019; Cardoso et al., 2025). Moreover, parasitoids and predators are commonly used to manage B. tabaci at every life stage, from eggs to pupae, thereby acting as essential biological regulators (Arnó et al., 2010).

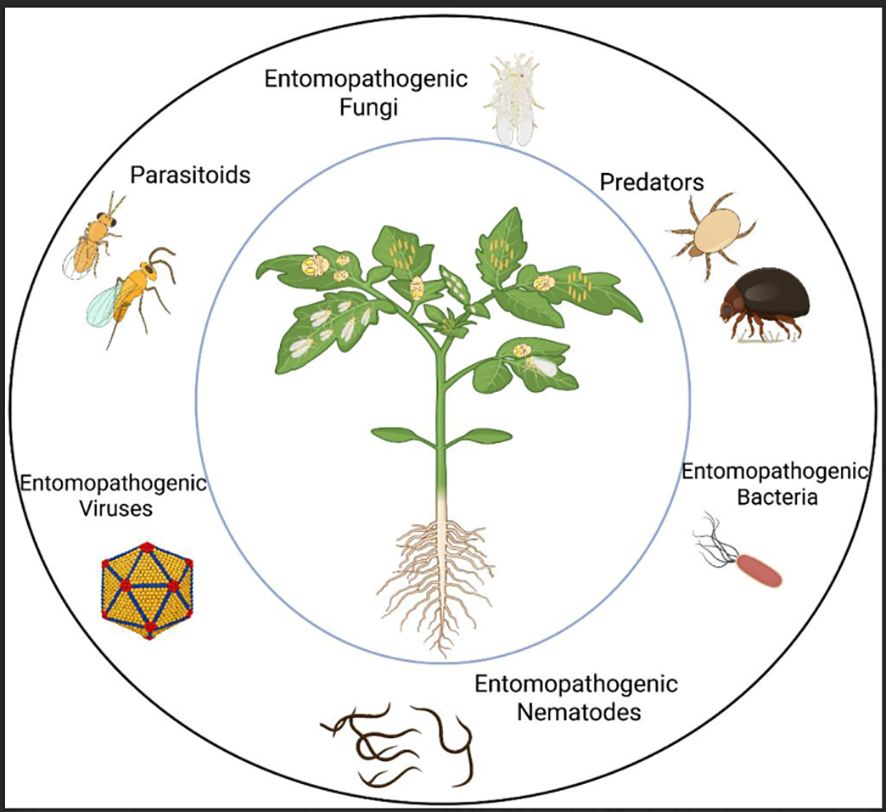

The goal of biological control is to harness these natural enemies, with their behaviors and ecological interactions, to reduce reliance on insecticides and enhance the overall effectiveness of IPM .(Figure 1). Field tests and controlled experiments have shown that introducing or conserving natural predators effectively suppresses B. tabaci populations (Naranjo and Ellsworth, 2009; Vandervoet et al., 2018; Zhang et al, 2020a). Habitat manipulation is a vital approach employed to augment the efficacy of natural enemies. This involves maintaining indigenous predator and parasitoid species by minimizing the use of insecticides, introducing new biocontrol species, or cultivating companion crops that offer refugia and alternative prey (Zhang et al., 2018, Zhang et al., 2020a; Taggar and Singh, 2020). Yet, choosing the suitable species or combination of natural enemies necessitates careful evaluation of existing pest-enemy interactions. Policies should therefore be informed by field-based research, ecological modeling, and life table analysis to accurately forecast outcomes and support sustainable, long-term success (Arnó et al., 2008, Arnó et al., 2010; Vafaie et al., 2020).

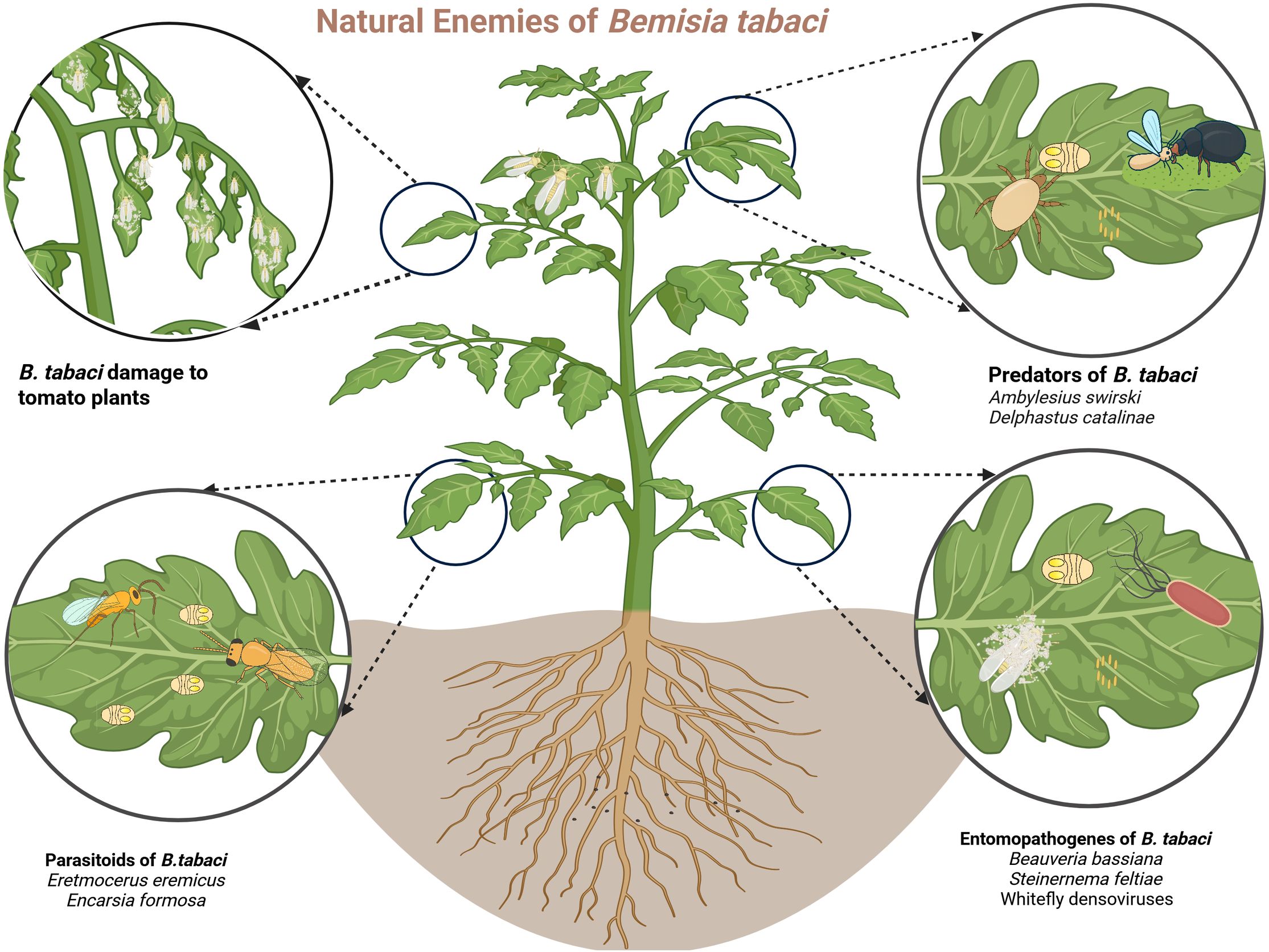

Figure 1. Illustration of a tomato plant infested by the whitefly Bemisia tabaci, with insets depicting its principal natural enemies. The top left inset shows characteristic plant damage caused by the pest; the bottom left illustrates parasitoids (e.g., Eretmocerus eremicus); the top right presents predators (e.g., Amblyseius swirskii); and the bottom right depicts entomopathogens (e.g., Beauveria bassiana) (image created in Biorender)..

3.1 Predators of Bemisia tabaci

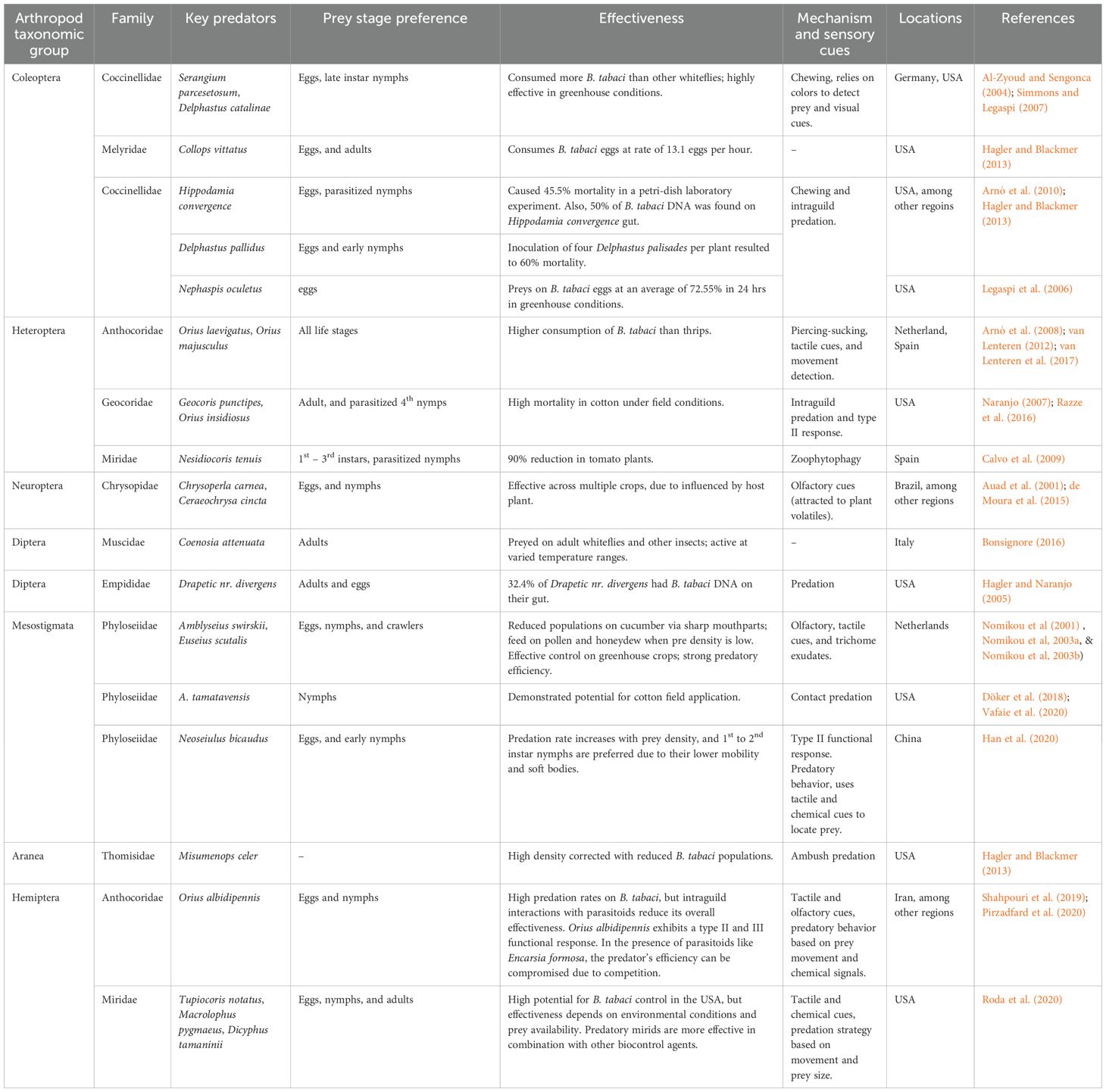

Abubakar et al. (2022) reported that more than 150 species of natural enemies have been identified, although comprehensive evaluations have been limited to only a few taxonomic groups. A diverse range of naturally occurring predators for B. tabaci has been identified, but only a limited number have been studied and assessed for biocontrol effectiveness (Arnó et al., 2008; Calvo et al., 2009; Cardoso et al., 2025) (Table 1). Key predators on B. tabaci include coccinellid beetles, lacewings, mirid bugs, predatory mites, and anthocorids (Li et al., 2021a) (Table 1). The coccinellid Delphastus catalinae (Horn) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), D. pusillus (LeConte) and predatory mites Amblyseius barkeri (Hughes) (Acarina: Gamasida: Phytoseiidae) and A. cucumeris (Oudemans) as well as Neoseiulus bicaudus (Wainstein) (Acari: Phytoseiidae) have been widely utilized in greenhouse conditions and have demonstrated significant effectiveness in decreasing B. tabaci populations on tomato among other plants (Al-Zyoud and Sengonca, 2004; Simmons and Legaspi, 2007; Han et al., 2020). Likewise, introducing six Macrolophus pygmaeus Rambur (Hemiptera: Miridae), per plant substantially reduced whitefly populations in watermelon (Abubakar et al., 2022). In regulated greenhouse conditions, Nesidiocoris tenuis Reuter (Hemiptera: Miridae), suppressed whitefly populations by more than 90% on tomato plants (Calvo et al., 2009). However, its efficacy against whiteflies feeding on sweet peppers was negligible (Legaspi et al., 2006). Additionally, Chrysoperla carnea (Stephens) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae), green lacewing, has been shown to manage B. tabaci when introduced at a density of 10 adults per plant in tomato greenhouses. Moreover, the synergistic use of C. carnea, Orius albidipennis Reuter (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae), and Phytoseiulus persimilis Athias-Henriot (Acari Phytoseiidae), a predatory mite, augmented the control of pests and increased cucumber production (Hagler and Naranjo, 2005; Arnó et al., 2008, Arnó et al., 2010). Table 1 shows a summary of the key predators of B. tabaci with notes on their preference and effectiveness. Additionally, certain species, such as Dicyphus hesperus Knight (Hemiptera: Miridae), have been shown to reduce B. tabaci egg and nymph populations by up to 60%, with the most significant impact observed during the nymphal stages (Smith and Krey, 2019). Similarly, some species, like Serangium parcesetosum Sicard (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), suppress the B. tabaci population within six weeks of release on Euphorbia pulcherrima plants (Ellis et al., 2001; Kheirodin et al., 2020), while A. tamatavensis (predatory mite) colonized nightshade infested with B. tabaci, and has the potential to be utilized as a predator against this pest (Döker et al., 2018) (Table 1).

3.1.1 Effectiveness of predators in different environments

The efficacy of predators in managing B. tabaci varies significantly across agroecological regions such as open agricultural fields, greenhouses, and controlled habitats. These differences are influenced by several factors, including temperature, humidity, prey availability, release rates, timing, habitat complexity, and existing management programs (Arnó et al., 2008; Gurr et al., 2017; Kheirodin et al., 2020). In open-field environments, predators such as D. catalinae and M. pygmaeus shows potential as a predator of this pest. Delphastus catalinae is specifically adapted to conditions that are favorable to B. tabaci, including moderate temperature and humidity (Simmons and Legaspi, 2007). However, extreme vapor pressure conditions, ranging from as low as 5.04 millibars (mb) to as high as 30.25 mb, can limit its field effectiveness by decreasing its survival and predation efficiency. These vapor pressure levels correspond to very low and high humidity conditions, respectively. Macrolophus pygmaeus has demonstrated positive effects in field evaluation; introducing six individuals per watermelon plant resulted in a 90% decrease in B. tabaci density (Cavalcante et al., 2016). These results demonstrate its potential for broader application in outdoor agricultural farming systems based upon ideal environmental conditions. Predatory species typically exhibit greater efficiency in controlled greenhouses because of constant microclimatic conditions. Predators such as O. laevigatus and Amblyseius swirskii (Athias-Henriot) (Acari: Phytoseiidae) efficiently prey on whitefly eggs and early nymphs in stable humidity and temperature conditions (Arnó et al., 2008; van Lenteren et al., 2017; Knapp et al., 2018). Amblyseius swirskii may endure low prey densities by consuming alternate food sources, including pollen and honeydew (Knapp et al., 2018). Amblyseius tamatavensis Blommers (Mesostigmata: Phytoseiidae) demonstrates enhanced efficacy when provided with cattail pollen, as evidenced by Cardoso et al. (2025), underscoring the significance of food supplementation for predator survival and dispersal in greenhouse environments. Notwithstanding their successes in greenhouse conditions, difficulties exist regarding sustainability and economic viability in commercial farming. Successfully incorporating predators into protected agricultural farming systems necessitates habitat modification, thorough species selection, and ongoing monitoring.

The timing of predator release is essential for optimal management. In greenhouse research, Nephaspis oculatus demonstrated superior suppression of B. tabaci populations when introduced at a beetle-to-whitefly ratio of 1:4 one day post-infestation, in contrast to later releases at reduced ratios (Liu and Stansly, 2005). These findings highlight the significance of adequate release rates and quick implementation for achieving optimal biological control. Roda et al. (2020) conducted field tests to compare the predatory effectiveness of three mirid species, N. tenuis, M. praeclarus, and Engytatus modestus, on tomato crops. All three species markedly reduced B. tabaci populations; however, the phytophagous activities of N. tenuis and E. modestus caused crop damage, including necrotic rings. Conversely, M. praeclarus caused negligible harm, rendering it a more appropriate option for integrated approaches. Moreover, companion planting with sesame increased mirid populations, underscoring the potential of habitat alteration to boost predator survival and effectiveness. Intraguild predation (IGP), in which generalist predators feed on both pests and beneficial parasitoids, is an important ecological interaction that can impact biological control outcomes. Naranjo (2007) conducted laboratory tests to examine IGP interactions among G. punctipes, O. insidiosus, H. convergens, and the parasitoid Eretmocerus sp. nr. emiratus. The results revealed that these predators frequently consumed parasitized whitefly nymphs, demonstrating a lack of preference between parasitized and non-parasitized hosts and a general preference for readily available prey. However, field data revealed that IGP had a minimal negative impact on the overall suppression of B. tabaci. This indicates that, although intraguild may occur under certain conditions, generalist predators still contribute significantly to pest management across varied habitats, particularly when predator densities are high and pest pressure is substantial (Naranjo and Ellsworth, 2009).

3.2 Parasitoids of Bemisia tabaci

Parasitoids are crucial agents for biological control in the suppression of whiteflies (Table 2), as they exploit B. tabaci nymphs for reproduction and larval development as well as nourishment (Gelman et al., 2005; Childs et al., 2011; Shah et al., 2015; Ebrahimifar and Jamshidnia, 2022). They are taxonomically diverse and widely distributed across different agroecological regions (Table 2). Gerling et al. (2001) and Goolsby et al. (2008) identified 34 Encarsia and 12 Eretmocerus (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) species, along with additional species from genera such as Amitus, Metaphycus, and Signiphora. Arnó et al. (2010) further documented 10 Eretmocerus and 15 Encarsia species across Mediterranean regions. In Western Sydney, Childs et al. (2011) discovered eight species from the Encarsia and Eretmocerus genera. Li et al. (2011) recorded 51 parasitoid species from multiple regions in China. To date, over 115 whitefly parasitoid species have been identified across 23 genera and five families, including Aphelinidae, Encyrtidae, and Platygastridae (Lahey and Stansly, 2015; Liu et al., 2015; Sani et al., 2020). Among these, the genera Encarsia and Eretmocerus (Hymenoptera) dominate and are widely used in biocontrol strategies (Zang and Liu, 2007; Zang et al., 2011; van Lenteren et al., 2017). These reports highlight the ecological richness and importance of parasitoids in the biological management of pests such as B. tabaci across different geographic locations (Table 2).

Parasitoid efficacy is shaped by host stage preference. Several studies indicate that whitefly parasitoids preferentially target 2nd and 3rd instar nymphs for oviposition, though parasitism of late nymphal stages can occur depending on species and environmental context (Antony et al., 2003, Antony et al. (2004)) (Table 2). For instance, Eretmocerus (Er) melanoscutus and Encarsia (En) pergandiella show strong host feeding and parasitism of B. tabaci nymphs (3rd instar), particularly under high density conditions (Zang et al., 2011). Encarsia sophia and Er. hayati effectively parasitizes early instars but avoids late instars (Shah et al., 2015). Host feeding of female parasitoids provides nutrients for egg production rather than oviposition, while honeydew availability enhances fecundity and longevity (Qiu et al., 2004b; Antony et al., 2004; Gauthier et al., 2015). Depriving adult parasitoids of food for six hours before release increases parasitism and feeding rates. Host-feeding by females, where parasitoids consume the host instead of ovipositing, is essential for obtaining nutrients for egg maturation and increases parasitism potential when food is limited (Luo and Liu, 2011; Zang et al., 2011). Interestingly, some species such as En. sophia demonstrate a preference for larger hosts, likely due to greater nutritional resources, even though smaller instars are more efficiently controlled (Luo and Liu, 2011). Manipulating environmental conditions, such as withholding food for brief periods before field release, has been shown to boost feeding and parasitism activity among adults (Qiu et al., 2004a). Moreover, parasitoids suppress B. tabaci populations either through oviposition within the host or by external feeding (Table 2), both of which disrupt development and reduce pest numbers effectively in field and greenhouse environments (van Lenteren et al., 2017).

3.2.1 Parasitoid efficiency and impact in ecological interactions

The growth and development of parasitoids are strongly influenced by the suitability of the host species. According to Luo and Liu (2011), adults of En. sophia that emerged from T. vaporariorum were larger and more fecund than those from B. tabaci, even though their development durations were equal. Increased parasitism and feeding rates were observed when females were sexed, as demonstrated under high-density host conditions for En. melanoscutus and En. sophia (Zang et al., 2011). Parasitoids need to modulate their host’s physiology in order to successfully develop. For example, Gelman et al. (2005) reported that parasitoids enhance their developmental success by suppressing the host’s immune response through the injection by the adults or production of immunosuppressive biochemicals by the embryos. Using parasitoids and predators simultaneously can improve or delay biological control results. Tan et al. (2016) studied the relationships of En. formosa, En. sophia, and the predatory ladybird Harmonia axyridis (Pallas) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). They observed that while predation and parasitism increased when the species were introduced together, H. axyridis markedly decreased parasitoid emergence. This underscores the necessity for compatibility evaluation while employing diverse natural enemy populations in IPM. Vafaie et al. (2020) compared Eretmocerus eremicus and Amblyseius swirskii in integrated pest control against conventional insecticides-based strategies in poinsettia greenhouses in the USA. Significantly, B. tabaci populations were comparable in both systems, indicating that biological control presents a practical and environmentally advantageous alternative to whitefly management in commercial horticulture.

3.3 Entomopathogens of Bemisia tabaci

Entomopathogenic organisms, including fungi, viruses, nematodes, and bacteria, are commonly used to mitigate B. tabaci damage and serve as key components of many pests’ management programs (Deshpande, 1999; Grewal et al., 2005; Bahadur, 2018; Deka et al., 2021; Bonaterra et al., 2022). These biological agents are an environmentally sustainable alternative to synthetic insecticides and are less harmful to farmers, non-target insect-pests, and other organisms (Oliveira et al., 2001; Abubakar et al., 2022; Li et al., 2024). Due to their natural occurrence in many pest-infested production systems, several entomopathogens have been studied and commercialized as biopesticides (Mascarin et al., 2013; Islam et al, 2014; Bahadur, 2018; Deka et al., 2021).

Entomopathogenic nematodes such as Steinernema feltiae and St. carpocapsae are virulent against B. tabaci (Cuthbertson et al., 2007, Cuthbertson et al., 2008; Li et al., 2021a, Cuthbertson et al., 2008; Perier et al., 2025a). For example, St. feltiae caused mortality rates of 32% and 28% of whiteflies in tomato and cucumber plants, respectively (Head et al., 2004). When combined with synthetic insecticides like thiacloprid and spiromesifen, St. carpocapsae caused mortality rates of 86.5% and 94.3%, respectively (Cuthbertson et al., 2008), highlighting the potential for synergistic applications for improved B. tabaci management. Similarly, Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF), such as Beauveria bassiana, Isaria fumosorosea (now redescribed as Cordyceps javanica), and Lecanicillium muscarium, have been widely explored (Cuthbertson et al., 2005b; Gabarty et al., 2014; Li et al., 2024). For instance, studies have demonstrated that over 90% of these EPF caused nymphal mortality within 8 days after application in vegetable crops like cucumber, melon, and zucchini squash (Wraight et al., 2000; Cuthbertson et al., 2005a, Cuthbertson et al., 2005b; Olleka et al., 2009; Mascarin et al., 2013). In controlled laboratory conditions, combinations of C. fumosorosea (C. javanica) with neem-based products like azadirachtin or with other fungal agents have achieved up to 90% mortality on various crops including beans, cucumbers, and melons (James and Elzen, 2001; Cuthbertson et al., 2005a; Mascarin et al., 2013).

3.3.1 Fungal pathogens

Entomopathogenic fungi are effective against a broad spectrum of insect pests, including sap-sucking pests like B. tabaci (Sani et al., 2020) (Table 3). EPF infect the host via direct contact, with conidia adhering to the cuticle, germinating, and penetrating through enzymatic and mechanical means (Sandhu et al., 2012; Gabarty et al., 2014; Li et al., 2021a; Ma et al., 2024). The infection efficiency of EPF depends heavily on surface contact and host susceptibility. Some insects secrete compounds that inhibit or enhance conidial adhesion and germination (Sani et al., 2020). After adhesion, the fungus forms an appressorium, a specialized structure that generates pressure and enzymatic action to breach the cuticle. Once inside the insect body, the fungus acts parasitically until the host dies, after which it shifts to saprophytic behavior, colonizing the cadaver and releasing new infective spores. Recent advancements in EPF formulations, such as incorporating biosurfactants, oils, and UV-protectants, have markedly enhanced spore viability and persistence under field conditions (Wraight et al., 2000; Zafar et al., 2016). Formulation techniques such as solid-state, liquid, and diphasic fermentation have facilitated large-scale EPF production from insect cadavers and soil sources (Esparza-Mora et al., 2016). New strains like Clonostachys rosea are under evaluation for pathogenicity and potential commercial use (Sani et al., 2020). Mycoinsecticides are now used both alone and in combination with other biological agents. For instance, C. javanica and Metarhizium anisopliae have demonstrated the ability to target multiple whitefly life stages, making them promising candidates for integration into IPM frameworks (Islam et al., 2014, Islam et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2020). Additionally, new strains are still being identified, therefore increasing the options of EPF that target B. tabaci (Wu et al., 2023a).

Many studies are increasingly exploring EPF as effective biological control agents against B. tabaci. These fungi initiate infection when their conidia adhere to the insect cuticle and germinate under favorable humidity. The resulting germ tube physically penetrates the cuticle through a combination of mechanical pressure and enzymatic activity. Once inside the hemocoel, the fungi proliferate as hyphal bodies that utilize the host internal nutrients, leading to nutrient depletion, physiological dysfunction, and eventually death. In addition, EPF produces toxins that invade host tissues and obstruct hemolymph circulation, further increasing whitefly mortality (Sandhu et al., 2012; Gabarty et al., 2014; Li et al., 2021a, Li et al., 2021b; Ma et al., 2024). Most current studies focus on fungal groups within the Entomophthorales and Hyphomycetes orders, which collectively comprise about 700 identified species (Khan et al., 2012; Gabarty et al., 2014; Anwar et al., 2018). Among these, B. bassiana, M. anisopliae, Isaria fumosorosea, L. lecanii, and A. aleyrodis have demonstrated promising efficacy in both greenhouse and open-field settings. The virulence of these EPF’s can vary depending on environmental conditions (e.g., humidity, temperature, host stage), the developmental stage of B. tabaci, and the fungal strain used (Liu et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2010a, Huang et al., 2010b; Islam et al., 2014, Islam et al., 2015; Zafar et al., 2016; Sani et al., 2020). Large-scale production of EPF from insect cadavers on soil can be achieved using solid-state, liquid-state, or di-phasic fermentation in artificial media (Esparza-Mora et al., 2016). Application methods such as foliar spraying or leaf dipping have proven effective for direct delivery of spores to B. tabaci infested surfaces. Table 3 provides a summary of the use of EPF’s in greenhouse and open-field settings in B. tabaci control.

3.3.2 Viral pathogens

In recent years, insect-specific viral pathogens have emerged as potential biocontrol agents for B. tabaci. These viruses are distinct from plant-infecting viruses such as Begomovirus and Torradovirus, which B. tabaci transmits as a vector (Nouri et al., 2018). Instead, insect-targeting viruses infect and disrupt the whitefly physiological processes, resulting in reduced fitness, reproduction, mobility, and ultimately lead to mortality (Nouri et al., 2018; Legarrea et al., 2022b). Among these, iridoviruses (double-stranded DNA viruses) have shown high mortality rates. Given that these pathogens are highly host-specific, there are no negative impacts on non-target organisms such as beneficial arthropods and pollinators, an advantage over synthetic insecticides. However, their relatively slow action presents a challenge. Unlike synthetic insecticides, viral pathogens may take several days to weeks to establish infection and cause significant population suppression and death (Zhang et al, 2020a). Laboratory studies have demonstrated that Invertebrate iridescent virus 6 (IIV-6) can cause mortality rates exceeding 70% in B. tabaci, with visible signs of infection including iridescence and reduced movement (Prompiboon et al., 2010). Similarly, Whitefly densoviruses (WFDVs), a group of parvoviruses, have been isolated from B. tabaci and shown to induce high nymphal and adult mortality, while also impairing feeding behavior and virus transmission ability (Wei et al., 2006). The mode of action begins, when viral particles attach to the whitefly’s cuticle and penetrate via natural openings and/or wounds. After entering, they replicate in host cells, leading to tissue degradation and host’s death. These viral pathogens are highly host-specific, minimizing risks to non-target organisms such as pollinators and predatory arthropods. This ecological specificity presents a key advantage over broad-spectrum synthetic insecticides. Moreover, some viruses also reduce the ability of whiteflies to transmit plant pathogens by interfering with their internal physiology (e.g., salivary gland function), thereby offering dual benefits, direct pest suppression and reduced vector competence (Lee et al., 2014; Legarrea et al., 2022b).

Despite promising laboratory outcomes, large-scale adoption of viral biological control agents remains limited. Challenges include the high cost of mass production, formulation instability under open-field conditions, and the need for continuous applications due to the B. tabaci rapid reproduction rates, hence regular treatments are needed to reduce populations. Bemisia tabaci typically acquire the virus through contact or ingestion, after which the particles enter via natural openings (e.g., spiracles, mouthparts, or wounds), replicate within host cells, degrade tissue integrity, and cause lethal effects or lead to death (Nouri et al., 2018; Legarrea et al., 2022b). Environmental conditions, including temperature, humidity, and UV radiation, can impact these viruses stability and effectiveness. For instance, UV rays can destroy virus particles before they infect hosts, significantly impacts viral efficacy. As a result, UV-protective formulations are under development to improve open-field performance and efficacy (Firdaus et al., 2012). Ongoing research aims to identify novel viral strains, improve environmental tolerance, use of recombinant viral constructs to increase virulence and specificity, and develop cost-effective delivery systems. Moreover, integrating other IPM components, such as EPF and/or selective insecticides as well as development of microencapsulated and oil-based delivery for improved environmental tolerance to improve synergistic outcomes. Additionally, advances in formulation technology, field validation, and delivery mechanisms are necessary to move from experimental applications to widespread open-field use.

3.3.3 Pathogenic bacteria

Bacterial biocontrol agents have garnered increasing interest in B. tabaci management due to their environmental safety, host specificity, and compatibility with IPM strategies (Bravo et al., 2007; Abubakar et al., 2022). Among these, Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), have gained prominence due to their high specificity and safety profile, and are commonly used to manage chewing insect pests. Bacillus thuringiensis is a Gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium that produces crystal (Cry) and cytolytic (Cyt) proteins that are toxic to several insect pests, including B. tabaci. These proteins are activated in the alkaline midgut of the insects, where they bind to epithelial cell receptors, forming pores that disrupt osmotic balance as well as ion transport. This leads to cell lysis, gut paralysis, and increasing insect mortality (Bravo et al., 2007; Soberón et al., 2010; Palma et al., 2014). Interestingly, some Bt toxins serve as an attractive component of IPM program due to its high specificity, which reduces the risk of harming non-target organisms such as pollinators and natural enemies. Laboratory assays have demonstrated promising efficacy against B. tabaci, however, field testing yielded inconsistent results. One major limitation is that the B. tabaci phloem sap feeding behavior limits ingestion of Bt toxins, compared to chewing pests like Lepidopteran larvae that consume large quantities of treated plant tissue (Bravo et al., 2007; Abubakar et al., 2022). Synergistic strategies have been established to address this issue. This involves integrating Bt with EPF and/or chemical surfactants can enhance spore adhesion to the insect cuticle and increase the likelihood of and ingestion. Genetic engineering has resulted in transgenic plants that produce Bt toxins designed for sap-feeding insects, yet regulatory and environmental challenges remain (Esparza-Mora et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2020). Beyond Bt, other bacterial species have shown potential in controlling B. tabaci. Some strains have demonstrated moderate toxicity and behavioral deterrence in greenhouse trials (Sani et al., 2020; Abubakar et al., 2022). For example, Chromobacterium subtsugae and Burkholderia spp. These species have also emerged as naturally occurring soil bacteria with insecticidal properties; has been developed into commercial formulations that have shown promising effects against soft-bodied insects, including B. tabaci under semi-field conditions. Its cell-free extracts significantly reduce adult survival and nymph counts, with bioactive compounds that remain stable under various environmental conditions. These species have also emerged as potential biocontrol agents, certain strains may interfere with whitefly symbionts and reduce vector capacity, although field validation is still limited (Martin et al., 2007; Abubakar et al., 2022; Shannag, 2025).

Despite these promising avenues, several environmental stressors hinder the large-scale use of bacterial biocontrol agents, including UV light and hot temperatures, can deteriorate Bt spores and Cry proteins, among other bacteria spp., thereby reducing their efficacy. Techniques such as encapsulation and UV-protective coating have been explored to mitigate such limitations (Bravo et al., 2007; Esparza-Mora et al., 2016). Another challenge is the emergence of insecticide resistance in target populations (Huang et al., 2010a, Huang et al., 2020). To ensure sustained effectiveness, resistance management measures, including habitat planting and the rotation of Bt strains with different modes of action, are crucial (Palma et al., 2014; Vacante and Bonsignore, 2017). To enhance the sustainability of pest management, ongoing advancements in formulation technologies, resistance management, and integration with other IPM tools will be crucial for improving the effectiveness and field adoption of bacterial biocontrol agents.

3.3.4 Entomopathogenic nematodes

Entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) are efficient biocontrol agents due to their active host-seeking behavior and high pathogenicity (Koppenhöfer and Kaya, 2001; Perier et al., 2025a). EPNs are naturally found in the soil. However, increasing reports of efficacy in several pest species have led to more adaptation of their use in other systems, such as above-ground areas (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2002a; Shapiro-Ilan and Gaugler, 2002b). Steinernema and Heterorhabditis are the most prevalent pest control genera, which are commercially available (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2016). These nematodes enter hosts through natural openings (like spiracles, anus, and mouth), releasing symbiotic bacteria, such as Xenorhabdus spp., in Steinernema, and Photorhabdus in Heterorhabditis, which rapidly proliferates and digest host tissues within approximately 24–48 hours, ultimately providing nutrients for EPN development and reproduction. Upon depletion of host resources, infective juveniles (IJs) emerge to seek new hosts (Head et al., 2004; Oliveira-Hofman et al., 2023; Shapiro-Ilan and Lewis, 2024). Infective juveniles are the only free-living stage of the EPN lifecycle, making them prime targets for many pests management programs (Shapiro-Ilan and Lewis, 2024). EPN infective juveniles are virulent against B. tabaci under several experimental conditions, including laboratory, greenhouse, and open-field settings, specifically targeting whitefly immature and adult life stages on the undersides of plant leaves (Cuthbertson et al., 2008; Li et al., 2021a, Li et al., 2021b; Perier et al., 2025a).

Steinernema feltiae and H. bacteriophora are among the most efficacious EPNs that have been tested for virulence against B. tabaci among other insect-pests (Koppenhöfer and Kaya, 2001; Cuthbertson et al., 2007; Laznik and Trdan, 2014; Li et al., 2021b). EPN variability in efficacy can also be improved with pheromone treatments (Oliveira-Hofman et al., 2019; Perier et al., 2024) based on their biological compounds (Kaplan et al., 2012), even when managing B. tabaci (Perier et al., 2025b). EPN success in pest management is based on environmental factors, including humidity, temperature, and protection from UV light (Wu et al., 2023b; Perier et al., 2025b). High humidity is vital for their survival, movement, and host infection, reducing the application of EPNs in arid environments (Koppenhöfer and Kaya, 2001). One key advantage of EPNs in whitefly management is their ability to infect concealed or sedentary life stages, such as later nymphal instars and pupae, which are often physically protected from predators, parasitoids, and foliar-applied agents like fungi. EPNs can be applied using conventional agricultural sprayers and irrigation systems, enhancing their compatibility with established farming methods (Koppenhöfer and Kaya, 2001; Cuthbertson et al., 2007; Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2002a, Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2016). Innovations such as gel-based carriers and UV-protective coatings are being investigated to improve field performance (Pirzadfard et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2023b; Shapiro-Ilan and Lewis, 2024; Perier et al., 2025a, Perier et al., 2025b). The compatibility of EPNs also extends to other management tools, such as biocontrol agents, insecticides, and other entomopathogens (Naranjo and Ellsworth, 2009; Laznik and Trdan, 2014; Oliveira-Hofman et al., 2023; Perier et al., 2024, Perier et al., 2025b). Notwithstanding its potential, the application of EPNs requires strict adherence to its optimum conditions in any crop production setting. The production and formulation for extensive deployment can be expensive, which may further limit their use (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2002a; Shapiro-Ilan and Gaugler, 2002b). However, farmers may utilize adapted methods for EPN production for management uses (Oliveira-Hofman et al., 2023). Moreover, methods for the in vivo production of EPNs continue to improve (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2016).

4 Integration of natural enemies into integrated pest management

Integrated pest management is a cornerstone of modern agriculture, aimed at minimizing reliance on the use of synthetic insecticides to mitigate their adverse effects on human health, non-target organisms and the environment (Firdaus et al., 2012; van Lenteren, 2012; Parkins et al., 2024). To manage B. tabaci, effective IPM strategies include integrating biological control, host plant resistance, cultural practices, and judicious usage of selective insecticides (Sani et al., 2020; Perier et al., 2022). Biological control utilizing predators, parasitoids, and entomopathogens is essential for attaining sustainable and environmentally friendly pest management. These methods not only help to maintain pest populations below economic threshold level but also promote biodiversity and ecosystem health. By fostering natural enemies and employing diverse agricultural practices, farmers can create resilient systems that are better equipped to withstand pest pressures (Gurr et al., 2017; Vandervoet et al., 2018; Abubakar et al., 2022). The intricacy of pest ecosystems necessitates coordinated and particular approaches that ensure maximum effectiveness (Firdaus et al., 2012).

4.1 Benefits of synergistic interactions of predators, parasitoids, and pathogens

Using predators, parasitoids, and entomopathogens together enhances the effectiveness of B. tabaci management, as these natural enemies work via complementary mechanisms and collectively target multiple stages of the pests life. While there is overlap in the stages they attack, and some degree of IGP may occur, these agents can still function synergistically within an IPM framework. For example, generalist predators like M. pygmaeus and D. catalinae actively feed on whitefly eggs, nymphs, and adults, which suppresses B. tabaci numbers at different stages of development and/or life cycle. These predators are not only voracious but also highly adaptable to diverse environmental conditions and cropping systems, making them valuable assets in IPM programs (Cuthbertson et al., 2007; Arnó et al., 2010; Shah et al., 2015; Cavalcante et al., 2016; Bowers et al., 2020; Pirzadfard et al., 2020). Meanwhile, parasitoids such as En. formosa and Er. eremicus attack immature whitefly life stages (2nd and 3rd instars), thereby reducing the number of individuals (B. tabaci nymphs) that progress to adulthood (Naranjo, 2007). Studies have shown that even low release rates of these parasitoids can result in significant parasitism levels and contribute to long-term suppression of B. tabaci populations (Liu and Stansly, 2005; Liu et al., 2015).

Entomopathogens, for example Bt, Beauveria bassiana, and St. feltiae, act through infection, leading to internal tissue degradation and eventual host death. These microbial agents are integral components of IPM due to their high host specificity and relatively low impact on target pests/organisms (Bahadur, 2018; Abubakar et al., 2022). While they may persist in the environment under favorable conditions, such as adequate humidity, moderate temperatures, and protection from UV exposure, their effectiveness can decline rapidly when exposed to environmental stressors (Faria and Wraight, 2001; Inglis et al., 2001). Therefore, the success of microbial control strategies depends heavily on matching the agent to the local agroecological conditions and optimizing application timing and formulation for improved persistence. Additionally, integrating these biological agents into a unified IPM strategy can prevent pest resurgence and escape, which are common limitations when using a single control method (Cuthbertson et al., 2008). For instance, EPNs, pathogens and parasitoids are especially effective against stationary life stages such as nymphs and pupae, while predators are more efficient at capturing mobile stages. Using Beauveria bassiana with Er. hayati has been found to reduce whiteflies more than using either one alone (Olleka et al., 2009; Ou et al., 2019). Also, using lower dose of chemical insecticides help keep pollinators safe, supports beneficial insects, and slows down pests from becoming resistant, which is essential for the long-term success of IPM (Zhang et al, 2020a).

Combining biological agents leads to synergistic interactions that enhance pest suppression beyond the sum of individual effects (Liu and Stansly, 2005). For example, using Er. mundus and predatory mites like A. swirskii have greatly reduced B. tabaci populations in crops grown in greenhouses. These combinations use different behaviors and attack methods to target various life stages of the pests, which helps reduce the chances of the pests adapting or becoming resistant (Liu et al., 2015). Similarly, the co-application of EPF with selective insecticides can improve efficacy, although success depends on compatibility between agents and the precise timing of their applications (Razze et al., 2016; Abubakar et al., 2022). A similar synergistic effect is observed when generalist predators are combined with selective insecticides for managing B. tabaci populations. Recent studies have shown that selective insecticides can affect both the direct and indirect interactions between predators and prey, with varying impacts on predator efficiency. The combination of insecticides with predators, particularly those targeting B. tabaci, can either increase or reduce predator performance depending on the insecticides toxicity, residual activity, and impact on predator behavior (Parkins et al., 2024). When thoughtfully integrated, these strategies minimize non-target impacts and enhance ecosystem resilience. Reduced insecticides inputs lower the risk of resistance development, mitigate environmental pollution, and support consumer demand for residue-free agricultural plant products. Furthermore, these methods are particularly valuable for small farmers, as they reduce reliance on costly synthetic insecticides and improve productivity in low-resource settings (Vandervoet et al., 2018; Sani et al., 2020; Ghongade and Sangha, 2021).

5 Biocontrol enhancement approaches and factors influencing beneficial fauna

The effectiveness of entomopathogens, predators, and parasitoids in controlling B. tabaci largely depends on establishment, augmentation, and preservation of their native populations within the agroecosystem. Habitat diversity strategies, such as cover cropping, intercropping, and mixed cropping systems, as well as plants like floral strips and banker plants, provide pollen and nectar, thus influencing the abundance and diversity of natural enemies (Abd El-Baky, 2009; Mkenda et al., 2019; Bowers et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022; Abubakar et al., 2022). According to Bianchi and Wäckers (2008), the attractiveness of flowers and the presence of nectar are the two most important elements that increase natural enemies population in open-field plant settings. Whiteflies have been shown to be effectively suppressed by natural enemies, whose abundance and diversity are enhanced by the floral nectar of non-crop plants in arable systems (Hernandez et al., 2013; Mkenda et al., 2019). Moreover, sustainable farming practices such as crop rotation and mulching protect agricultural fields thereby improving quality and quantity of ecological habitats of natural enemies (Mkenda et al., 2019). A careful release of important biocontrol agents listed in Tables 1–Mw== positively enhanced B. tabaci control in open agricultural fields and greenhouse conditions (Naranjo and Ellsworth, 2009; Xu et al., 2013; Razze et al., 2016; van Lenteren et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2023a). Similarly, selective application of biopesticides as well as natural plant base produce are equally significant in reducing the non-target effects and aligns with IPM programs (Cuthbertson et al., 2008; Ayilara et al., 2023; Ghongade and Sangha, 2021; Abubakar et al., 2022).

Agroecological and environmental conditions have a significant impact on beneficial fauna efficiency. The impact of these abiotic factors on performance at the cell, tissue and organ level is often indicated in suppression of whole organism behavior. For example, Beauveria bassiana is most effective in humid conditions, while abiotic factors like humidity, temperature, and light have a positive impact on predator and parasitoid growth and feeding performance (Mishra et al., 2015). Moreover, these factors have a significant influence on effectiveness of entomopathogens (Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2002a; Qiu et al., 2004a , Qiu et al., 2004b; Javar et al., 2023). While sublethal levels of synthetic insecticides may inhibit predator feeding or oviposition of parasitoids (Parkins et al., 2024), plant chemical and morphological traits could contribute (either positively or negatively) and impair biocontrol. The intraguild interactions, such as hyperparasitoid activity and predator ingestion of target or non-target insect-pests, may further limit the effectiveness of biocontrol (Velasco-Hernández et al., 2013). Integrating sustainable cropping systems, preservation of ecological habitats and minimal exposure to environmental hazards will positively enhance the management approaches that maximize natural enemy populations in the long-term management of B. tabaci (Naranjo and Ellsworth, 2009; Peñalver-Cruz et al., 2019; Li et al., 2022). However, the efficiency of natural enemies maybe frequently reduced by monoculture cropping systems.

6 Challenges in the implementation of biocontrol

One of the major significant challenges in the implementation of biocontrol lies in the establishment of biocontrol agents, as well as the frequent lack of consistency in its performance over time. Several biocontrol agents exhibit positive results in greenhouse and laboratory settings. However, they do not often thrive well in an open agricultural field conditions where their ability to reproduce and survive are negatively influenced by climatic conditions (Gerling et al., 2001; Nomikou et al., 2003a, Nomikou et al., 2003b). Even though using natural enemies is a sustainable way to control B. tabaci, many scientific, ecological, and practical problems make it hard to incorporate it into IPM programs (Table 4). These challenges include biological limitations (e.g., host specificity, prey scarcity, and IGP), climatic conditions and environmental sensitivity (such as UV light, humidity, atmospheric pressure, and temperature), scalability issues and high cost of mass-rearing, and incompatibility with commonly used synthetic insecticides (Gerling et al., 2001; Nomikou et al., 2003a, Nomikou et al., 2003b; Gould et al., 2009; van Lenteren et al., 2017) (Table 4). Also, prolonged insecticide use has resulted in resistance development and genetic alterations in B. tabaci, adding complexity to biocontrol efforts and requiring integrated, simultaneous multi-tactic management approaches (Oliveira et al., 2001; Horowitz et al., 2005; De Barro et al., 2011; Taggar and Singh, 2020).

Table 4. Key challenges and recommended solutions for integrating natural enemies and entomopathogens into whitefly Integrated Pest Management programs .

6.1 Future directions

To overcome current limitations and enhance biological control integration in IPM, future pest management should focus on filling knowledge gaps and developing technologies that improve efficiency, scalability, and farmer adoption. Breeding and genetic alteration can improve natural enemy and entomopathogen adaptability, fecundity, and host-finding capacity. In open-field strategies such as planting flower strips, cover crops, mixtures, and/or intercropping systems provide alternative food sources and habitats for natural enemies, enhancing their persistence in cropping systems. Technological advances in metagenomics, 16s amplicon sequencing, and molecular gut content analysis offer promising avenues for identifying novel microbial consortia and endophytic fungi, and evaluating trophic interactions between pests and natural enemies (Hagler and Naranjo, 2005; Dinsdale et al., 2010; González-Chang et al., 2016; Gurr et al., 2017). These tools can inform better matching of predators and parasitoids to specific agroecosystems and crop diversification. To efficiently control B. tabaci populations in the future, a synthesis of RNA interference (RNAi) approaches, as described by Shelby et al. (2020), should be explored for targeting important whitefly genes, along with chemical control measures such as cyantraniliprole. This method not only reduces whitefly populations but also limits the spread of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus (TYLCV), hence improving IPM strategy and fostering more sustainable pest control (Lee et al., 2014). Also, the use of transgenic crops and entomopathogens that are tolerant to adverse environmental conditions and support natural enemies are needed.

Further studies should explore application technology to improve the delivery efficiency of biological control agents. For instance, novel sprayer tips that target the abaxial leaf surface, where whiteflies, among other pests, predominantly reside, may improve entomopathogens propagule deposition (Ou et al., 2019; Li et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2024). Additionally, anti-desiccation and UV-protection innovations for entomopathogens are urgently needed to maintain efficacy under field conditions. Future studies should also assess the compatibility of biological agents with synthetic insecticides, ensuring minimal antagonistic interactions while improving efficacy (Sani et al., 2020; Quesada-Moraga et al., 2023). Co-operative extension programs must provide farmer training on integrating biological control into pest management practices, including the timing and application of selective insecticides. Public awareness and marketing support will also be crucial in encouraging broader adoption of biocontrol products (Dainese et al., 2019).

Many whitefly biocontrol studies have focused on laboratory or greenhouse settings, limiting their practical application. There is a need for research under commercial open-field settings, including studies on landscape complexity and different agroecological zones, which influence the recruitment and movement of natural enemies (Dinsdale et al., 2010; Dainese et al., 2019; Gurr et al., 2017; Bowers et al., 2020). Additionally, research in the USA, has predominantly focused on cotton, despite whiteflies being a significant pest in vegetable crops. Given the variation in plant architecture and cropping systems, whitefly control strategies must be tailored to crop type and regional conditions. Regional field trials should optimize natural enemy release ratios and identify dominant predator guilds based on local climate conditions and crop cycles (Goolsby et al., 2008; Bowers et al., 2020).

Projecting forward, it is critical to understand that the efficiency of biocontrol strategies against B. tabaci will depend on policies that promote effective extension and outreach programs alongside developments in scientific research. The contribution of extension services to addressing the knowledge gap between research and practice is equally significant. Real-time recommendations on pest pressure and natural enemy activity can be obtained by routine field scouting, farmer field schools, and digital decision-support technologies. Sustainable biocontrol implementation can be advanced through policies that promote IPM programs, encourage diversified ecological farming practices, restrict the use of broad-spectrum synthetic pesticides, and provide subsidies for biocontrol inputs. Overall, these approaches will help growers make informed decisions about the timing and type of control strategy, chemical or biological, based on current pest pressures and natural enemy dynamics (Wilson and Daane, 2017; Goode et al., 2019).

7 Conclusion

This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of natural enemies’ critical role in the sustainable management of B. tabaci, a globally destructive and genetically diverse pest species. Predators, parasitoids, and beneficial microbes (like fungi, bacteria, viruses, and nematodes) can effectively control B. tabaci by attacking it at different stages of its life cycle. Their integration within IPM frameworks reduces pest populations and aligns with environmentally conscious farming practices by minimizing the reliance on conventional insecticides. The effectiveness of these natural enemies comes from how they work together. For example predators like Macrolophus pygmaeus feed on eggs, nymphs, and adult pests; parasitoids such as Encarsia formosa and Encarsia eremicus weaken whitefly nymphs by laying eggs inside them; and entomopathogens infect whiteflies in various ways, leading to death. These biocontrol agents provide a combined strategy that improves whitefly control while protecting beneficial pollinators, biodiversity, and the environment. The overuse of synthetic insecticides poses serious environmental challenges, including disruption of food chains, loss of beneficial species, and the development of insecticide resistance in B. tabaci, underscoring the need to adopt natural pest control strategies. However, environmental variability, including UV exposure, humidity, and temperature extremes, limits the field efficacy of biocontrol agents like entomopathogens. Host specificity of some agents restricts their use in mixed-pest systems, while high production and application costs hinder adoption among farmers.

The new generation of IPM must adopt a multidisciplinary approach to tackle B. tabaci control. Future research should focus on evolutionary biology and population genetics to monitor resistance development and optimize natural enemy deployment. Advancements in biotechnology, precision application technologies, and expanding biological control trials to diverse cropping systems and landscapes will enhance biocontrol applicability. Strengthening extension services, policy support, and farmer education is crucial for promoting the widespread adoption of biocontrol tools, while reducing dependency on broad-spectrum chemical insecticides, will help to pave the way for more sustainable and resilient agricultural systems. Realizing the full potential of biocontrol agents will depend on sustained investment in research, capacity building, public-private collaboration, and policy support. With coordinated global and local actions, natural enemies can become the cornerstone of climate-smart B. tabaci management, contributing to food security, environmental conservation, and resilient agroecosystems.

Author contributions

AJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OU: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AE: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MT: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work is supported by the Non-Assistance Cooperative Agreement #58-6080-4-016 from the USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the Department of Entomology, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, University of Georgia, for their invaluable support and the use of their facilities during the development of this review paper

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abd El-Baky H. H. (2009). Field application of entomopathogenic fungi for whitefly control in Egypt. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 42, 1045–1053. doi: 10.1080/03235400701820935

Abd-Rabou S. and Simmons A. M. (2010). Survey of reproductive host plants of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in Egypt, including new host records. Entomological News 121, 456–465. doi: 10.3157/021.121.0507

Abubakar M., Koul B., Chandrashekar K., Raut A., and Yadav D. (2022). Whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) management (WFM) strategies for sustainable agriculture: A Review. Agriculture 12, 1317. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12091317

Al-Zyoud F. and Sengonca C. (2004). Prey consumption preferences of Serangium parcesetosum Sicard (Col., Coccinelidae) for different prey stages, species and parasitized prey. J. Pest Sci. 77, 197–204. doi: 10.1007/s10340-004-0054-5

Antony B., Palaniswami M. S., and Henneberry T. J. (2003). Encarsia transvena (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) development on different Bemisia tabaci Gennadius (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) instars. Environ. Entomology 32, 584–591. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X-32.3.584

Antony B., Palaniswami M. S., Kirk A. A., and Henneberry T. J. (2004). Biology of Encarsia bimaculata (Heraty and Polaszek) (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) on Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae). BioControl 49, 565–582. doi: 10.1023/b:bico.0000047153.26420.3e

Anwar W., Ali S., Nawaz K., Iftikhar S., Javed M. A., Hashem A., et al. (2018). Entomopathogenic fungus Clonostachys rosea as a biocontrol agent against whitefly (Bemisia tabaci). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 28, 750–760. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2018.1487030

Arnó J., Gabarra R., Liu T. X., Simmons A. M., and Gerling D. (2010). Natural enemies of Bemisia tabaci: Predators and parasitoids. Ed. Stansly P. A. (Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2460-2_12

Arnó J., Roig J., and Riudavets J. (2008). Evaluation of Orius majusculus and O. laevigatus as predators of Bemisa tabaci and estimation of their prey preference. Biol. control 44, 1–6. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2460-2_15

Auad A. M., Toscano L. C., Boiça A. L. Jr., and de Freitas S. (2001). Aspectos biológicos dos estádios imaturos de Chrysoperla externa (Hagen) e Ceraeochrysa cincta (Schneider) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) alimentados com ovos e ninfas de Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) Biótipo B (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Neotropical Entomology 30, 429–432. doi: 10.1590/S1519-566X2001000300015

Ayilara M. S., Adeleke B. S., Akinola S. A., Fayose C. A., Adeyemi U. T., Gbadegesin L. A., et al. (2023). Biopesticides as a promising alternative to synthetic pesticides: a case for microbial pesticides, phytopesticides, and nanobiopesticides. Front. Microbiol. 14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1040901

Bahadur A. B. (2018). Entomopathogens: role of insect pest management in crops. Trends Horticulture 1. 1, 1–8. doi: 10.24294/th.v1i4.833

Barbosa M. F. C., Poletti M., and Poletti E. C. (2019). Functional response of Amblyseius tamatavensis Blommers (Mesostigmata: Phytoseiidae) to eggs of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) on five host plants. Biol. Control 138, 104030. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104030

Barman A. K., Roberts P. M., Prostko E. P., and Toews M. D. (2022). Seasonal occurrence and reproductive suitability of weed hosts for sweetpotato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), in South Georgia. J. Entomological Sci. 57, 1–11. doi: 10.18474/jes20-94

Bianchi F. J. J. A. and Wäckers F. L. (2008). Effects of flower attractiveness and nectar availability in field margins on biological control by parasitoids. Biol. Control. 46, 400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.04.010

Bonaterra A., Badosa E., Daranas N., Francés J., Roselló G., and Montesinos E. (2022). Bacteria as biological control agents of plant diseases. Microorganisms 10, 1759. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10091759

Bonsignore C. P. (2016). Environmental factors affecting the behavior of Coenosia attenuata, a predator of Trialeurodes vaporariorum in tomato greenhouses. Entomologia Experimentalis Applicata 158, 87–96. doi: 10.1111/eea.12385

Bowers C., Toews M., Liu Y., and Schmidt J. M. (2020). Cover crops improve early season natural enemy recruitment and pest management in cotton production. Biol. Control 141, 104149. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104149

Bravo A., Gill S. S., and Soberón M. (2007). Mode of action of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry and Cyt toxins and their potential for insect control. Toxicon 49, 423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.11.022

Brown J. K. (1992). Whitefly-Transmitted Geminiviruses and associated disorders in the Americas and the Caribbean Basin. Plant Dis. 76, 220–220. doi: 10.1094/pd-76-0220

Calvo J., Bolckmans K., Stansly P. A., and Urbaneja A. (2009). Predation by Nesidiocoris tenuis on Bemisia tabaci and injury to tomato. BioControl 54, 237–246. doi: 10.1007/s10526-008-9164-y

Cardoso A. C., Marcossi Í., Fonseca M. M., Kalile M. O., Francesco L. S., Pallini A., et al. (2025). A predatory mite as potential biological control agent of Bemisia tabaci on tomato plants. J. Pest Sci. 98, 277–289. doi: 10.1007/s10340-024-01809-7

Cherry A. J., Pugh M., and Akintola A. J. (2004). Suppression of Bemisia tabaci on cassava in Nigeria with Metarhizium anisopliae. Mycopathologia 157, 111–118. doi: 10.1023/B:MYCO.0000024184.77479.2a

Childs I. J., Gunning R. V., and Mansfield S. (2011). Parasitoids of economically important whiteflies associated with greenhouse vegeta ble crops in Western Sydney. Aust. J. Entomology 50, 296–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-6055.2011.00806.x

Cavalcante A. C., Mandro A., Paes M. E. A., and Gilberto E. R. (2016). Amblyseius tamatavensis Blommers (Acari: Phytoseiidae) a candidate for biological control of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) biotype B (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in Brazil. International Journal of Acarology, 43(1), 10–15.

Cuthbertson A. G. S., Blackburn L. F., and Northing P. (2005a). Pathogenicity of the entomopathogenic fungus Lecanicillium muscarium against the sweet potato whitefly Bemisia tabaci under laboratory and glasshouse conditions. Mycopathologia 160, 315–319. doi: 10.1007/s11046-005-0122-2

Cuthbertson A. G., Mathers J. J., Northing P., Prickett A. J., and Walters K. F. (2008). The integrated use of chemical insecticides and the entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema carpocapsae (Nematoda: Steinernematidae), for the control of sweetpotato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Insect Sci. 15, 447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2008.00232.x

Cuthbertson A. G., Walters K. F., and Deppe C. (2005b). Compatibility of the entomopathogenic fungus Lecanicillium muscarium and insecticides for eradication of sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci. Mycopathologia 160, 35–41. doi: 10.1007/s11046-005-1114-1

Cuthbertson A. G. S., Walters K. F. A., Northing P., and Luo W. (2007). Efficacy of the entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema feltiae, against sweetpotato whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) under laboratory and glasshouse conditions. Bull. Entomological Res. 97, 9–14. doi: 10.1017/S0007485307004701

Dainese M., Martin E. A., Aizen M. A., Albrecht M., Bartomeus I., Bommarco R., et al. (2019). A global synthesis reveals biodiversity-mediated benefits for crop production. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax0121. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax0121

Dainese M., Schneider G., Krauss J., and Steffan-Dewenter I. (2017). Complementarity among natural enemies enhances pest suppression. Sci. Rep. 7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08316-z

De Barro P. J., Liu S.-S., Boykin L. M., and Dinsdale A. B. (2011). Bemisia tabaci: A statement of species Status. Annu. Rev. Entomology 56, 1–19. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085504

Deka B., Baruah C., and Babu A. (2021). Entomopathogenic microorganisms: their role in insect pest management. Egypt J. Biol. Pest Control , 31, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s41938-021-00466-7

de Moura A. P., Guimarães J. A., da Costa R. I. F., and Brioso P. S. T. (2015). Species of Chrysopidae (Neuroptera) associated to trellised tomato crops in two cities of Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Arq. Inst. Biol. São Paulo 82, 1–4. doi: 10.1590/1808-1657000412013

de Moya R. S., Brown J. K., Sweet A. D., Walden K. K., Paredes-Montero J. R., Waterhouse R. M., et al. (2019). Nuclear orthologs derived from whole genome sequencing indicate cryptic diversity in the Bemisia tabaci (Insecta: Aleyrodidae) complex of whiteflies. Diversity 11, 151. doi: 10.3390/d11090151

Deshpande M. V. (1999). Mycopesticide production by fermentation: potential and challenges. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 25, 229–243. doi: 10.1080/10408419991299220

Dinsdale A., Cook L. G., Riginos C., Buckley Y. M., and De P. J. (2010). Refined global analysis of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Aleyrodoidea: Aleyrodidae) mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase 1 to identify species level genetic boundaries. Ann. Entomological Soc. America 103, 196–208. doi: 10.1603/an09061

Döker İ., Hernandez Y. V., Mannion C., and Carrillo D. (2018). First report of Amblyseius tamatavensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) in the United States of America. Int. J. Acarology 44, 101–104. doi: 10.1080/01647954.2018.1461132

Ebrahimifar J. and Jamshidnia A. (2022). Host stage preference in the parasitoid wasp, Eretmocerus delhiensis, for parasitism and host-feeding. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 42, 327–332. doi: 10.1007/s42690-021-00549-w

Ekesi S., Maniania N. K., and Mohamed H. A. (2002). Biological control of whiteflies on vegetab les in Kenya using entomopathogenic fungi. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 12, 399–409. doi: 10.1080/0958315021000016198

Ellis D., McAvoy R., Ayyash L. A., Flanagan M., and Ciomperlik M. (2001). Evaluation of Serangium parcesetosum (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) for biological control of silverleaf whitefly, Bemisia argentifolii (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae), on poinsettia. Florida Entomologist 84, 215–221. doi: 10.2307/3496169

Esparza-Mora M. A., Costa-Rouws J. R., and Fraga M. E. (2016). Occurrence of entomopathogenic fungi in atlantic forest soils. Microbiol. Discov. 4, 1. doi: 10.7243/2052-6180-4-1

Faria M. and Wraight S. P. (2001). Biological control of Bemisia tabaci with fungi. Crop Prot. 20, 767–778. doi: 10.1016/s0261-2194(01)00110-7

Firdaus S., van Heusden A. W., Hidayati N., Supena E. D. J., Visser R. G. F., and Vosman B. (2012). Resistance to Bemisia tabaci in tomato wild relatives. Euphytica 187, 31–45. doi: 10.1007/s10681-012-0704-2

Gabarty A., Salem H. M., Fouda M. A., Abas A. A., and Ibrahim A. A. (2014). Pathogencity induced by the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae in Agrotis ipsilon (Hufn.). J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 7, 95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jrras.2013.12.004

Gauthier N., Outreman Y., Mieuzet L., and Simon J. C. (2015). Influence of honeydew on the performance of parasitoids: A case study with the aphid parasitoid Aphidius ervi. J. Appl. Entomology 139, 496–504. doi: 10.1111/jen.12198

Gelman D. B., Gerling D., and Blackburn M. B. (2005). Host-parasite interactions between whiteflies and their parasitoids. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 60, 209–222. doi: 10.1002/arch.20101

Gerling D., Alomar O., and Arnó J. (2001). Biological control of Bemisia tabaci using predators and parasitoids. Crop Prot. 20, 779–799. doi: 10.1016/S0261-2194(01)00111-9

Ghongade S. S. and Sangha M. K. (2021). Efficacy of biopesticides against the whitefly, Bemisia tabaci, on cucumber under net house conditions. Egyptian J. Biol. Pest Control 31, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s41938-021-00365-x

Ghongade D. S. and Sood A. K. (2023). Biological characteristics and parasitization potential of Encarsia formosa Gahan (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) on the whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum Westwood (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), a pest of greenhouse crops in north-Western Indian Himalayas. Egyptian J. Biol. Pest Control 33, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s41938-023-00646-7

González-Chang M., Wratten S. D., Lefort M. C., and Boyer S. (2016). Food webs and biological control: a review of molecular tools used to reveal trophic interactions in agricultural systems. Food Webs 9, 4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.fooweb.2016.04.003