- Department of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences, Università degli Studi di Milano, Lodi, Italy

Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) poses a significant health and economic challenge in cattle farming, particularly affecting young calves. Although previous SNP-based genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified candidate loci linked to BRD susceptibility, they only explain a fraction of the trait’s heritability. Using genotypes from a previous study that employed a selective genotyping approach, we analyzed Holstein calves classified as BRD-resistant or BRD-susceptible, based on thoracic ultrasonography and clinical scoring. In particular, structural variations, specifically copy number variants (CNVs) and runs of homozygosity (ROH), were investigated due to their emerging role as complementary genomic features that may be involved in disease resistance. A total of 2,666 CNVs were identified, and the CNV-GWAS revealed 10 significant CNV regions (CNVRs), encompassing or near 15 candidate genes. While the ROH analysis identified 8,226 segments, we further applied a fixed-window approach to compare ROH frequencies between groups, revealing 19 regions with significantly different ROH frequencies. Gene annotation of both CNVRs and differential ROH windows uncovered genes linked to immune response, lung development, and known BRD-associated pathways. Functional enrichment analyses using DAVID and Cytoscape-GeneMANIA indicated involvement of antiviral responses, GPCR signaling, calcium signaling, and estrogen receptor pathway in disease resistance. Notably, 37% of the genes identified in this study overlapped with those reported in previous BRD-related studies. This integrative genomic analysis highlights the relevance of structural variation in shaping BRD resistance and susceptibility in dairy calves. By integrating CNV mapping, ROH analysis, and functional annotation approaches, we identified novel and previously reported candidate genes potentially involved in innate immune processes. These findings support the implementation of precision breeding strategies aimed at improving disease resilience in cattle.

1 Introduction

Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) is one of the most significant health challenges in cattle farms worldwide, with substantial impacts on both animal welfare and economic profitability (Overton, 2020). The disease is particularly prevalent in intensive farming systems, where high animal density and poor management practices can facilitate pathogen transmission. This scenario exemplifies the complex, multifactorial nature of BRD, wherein the interplay of infectious agents, external stressors, and individual factors (such as anatomical, genetic, and immune system characteristics) plays a crucial role in the disease’s development and progression (Ackermann et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2010). Despite advances in vaccination protocols and management practices, controlling BRD remains a significant challenge, particularly due to another substantial challenge characterizing the disease: the poor accuracy of its clinical signs, which thus complicates the definition of single or multiple cases (Buczinski and Pardon, 2020). This issue underscores the need for a deeper understanding of individual factors underlying its susceptibility.

The genetic predisposition plays a critical role in the variation of susceptibility to a disease across individuals (Tsairidou et al., 2019). Previous genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on BRD using single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as markers have identified candidate genes and loci associated with immune response, lung development, and pathogen defense (Lipkin et al., 2016; Quick et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022). However, SNPs alone do not fully capture the heritable component of BRD, prompting further exploration of structural genomic variations such as copy number variants (CNVs) and runs of homozygosity (ROHs). CNVs represent structural genomic variations where segments of DNA are duplicated or deleted (Mills et al., 2011). These variants can influence gene dosage or alter gene regulation, potentially impacting the animal’s immune response and overall disease resilience (MaChado and Ottolini, 2015). CNVs have been linked to traits such as growth (Zhou et al., 2016), reproduction (Oliveira et al., 2024), environmental and climatic adaptation (Salehian-Dehkordi et al., 2023), and various productive and adaptive traits (Salehian-Dehkordi et al., 2021), as well as disease resistance in cattle (Durán Aguilar et al., 2017), making them a promising target for understanding BRD susceptibility. On the other hand, ROHs are continuous stretches of homozygous genotypes that can arise from inbreeding or selective breeding. The length and frequency of ROH vary across populations, reflecting different breeding strategies and genetic backgrounds. The knowledge of ROH patterns can provide insights into the genetic architecture underlying disease resistance or susceptibility in livestock species. In cattle, specific ROH regions have been associated with loci influencing immune response and resilience to infectious diseases (Biscarini et al., 2016). Detecting and characterizing ROH associated with disease-related traits can therefore support genomic selection strategies aimed at enhancing animal health and reducing dependence on antibiotics.

This study aimed to enhance the understanding of genetic resistance to BRD in Holstein calves by building on previous SNP-based GWAS involving a cohort of BRD-resistant (R-BRD) and BRD-susceptible (S-BRD) individuals (Strillacci et al., 2025). These individuals were phenotypically characterized through the evaluation of lung lesions detected using thoracic ultrasonography (TUS), which represents a more advanced diagnostic method compared to relying solely on clinical signs related to BRD. Specifically, the objectives were i) to conduct a CNV-based GWAS to identify structural variants potentially associated with resistance to BRD-related TUS lesions and ii) to investigate ROHs that differentiate resistant calves from susceptible ones, to identify possible regions under selection or linked to disease susceptibility and resistance. The genotypic raw data of the samples used in this study were those available from Strillacci et al. (2025).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling

This study used phenotypic and genotypic data obtained from a previous study (Strillacci et al., 2025) that included samples collected from 10 intensive farms in Northern Italy, which had a reported history of respiratory disease in pre-weaned Holstein-Friesian calves. Briefly, clinical data were collected from 240 calves housed in group pens, none of which had received antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory treatments in the 15 days preceding the study. Each calf was evaluated using the Wisconsin Clinical Scoring System (WISC) (McGuirk and Peek, 2014) and underwent bilateral TUS (intercostal spaces 10–1 on the right and 10–2 on the left) using the ventral landmark protocol described by Ollivett et al. (2015). The severity of the disease was scored using the method described by Ollivett and Buczinski (2016), resulting in scores ranging from 0 to 5. BRD-susceptible calves (S-BRD, n = 47) were defined as those with a TUS score of 5, regardless of WISC score. BRD-resistant calves (R-BRD, n = 47) were defined as those with a TUS score of 0 or 1, a total WISC score ≤4, and absence of coughing. This classification enabled the application of a selective genotyping experimental design (Darvasi and Soller, 1992), which treats individuals from the tails of the phenotypic distribution as if they were case and control samples (Strillacci et al., 2025).

2.2 Statistical analysis

2.2.1 CNV detection and CNV association analysis

CNV detection was performed using the available raw genotyping data (log R ratio, LRR), obtained with the GeneSeek® Genomic Profiler Bovine 100K microarray by NEOGEN. These data were already available at the Animal Genomics Laboratory of the Department of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences. The reference genome used for mapping the SNPs was the ARS-UCD1.2. Quality control of the LRR values was performed using the SVS software by Golden Helix (Bozeman, MT, http://goldenhelix.com), with the dedicated statistical packages. This process involved i) examining the overall distribution of derivative log ratio spread (DLRS) values and ii) evaluating the GC content using the wave detection factor algorithm, which accounts for GC-related long-range waviness in LRR values.

Eight samples were excluded from further analysis due to elevated DLRS and GC wave factor (GCWF) values. CNVs were then detected using the Copy Number Analysis Module (CNAM) in SVS through a univariate segmentation analysis of LRR data. The analysis was performed using the following parameters: a maximum of 100 segments per 10,000 markers, a minimum of 3 markers per segment, and 2,000 permutations per pair with a P-value threshold of 0.05.

To perform the association analysis, the “segment list” for each calf (genomic segments where copy number variations with CNV were detected) was converted by SVS software into a categorical variable using a three-state coding scheme: −1 for losses, 0 for normal, and 1 for gain states. The classification threshold values (−0.30 for deletions and +0.30 for duplications) were defined through a histogram analysis (implemented in SVS) of the mean LRR values for each segment. Only CNVs ranging from 1,000 bp to 2.5 Mb in length were retained for the association analysis.

Phenotypic information (R-BRD as control = 0 and S-BRD as case = 1) was combined with the discretized CNV states for each individual to generate a unified dataset for the association analysis. The association analysis of CNVs was carried out using a statistical correlation/trend test implemented in SVS software. Due to the specific characteristics of CNVs (lower frequency, larger effect sizes, and more complex genomic architecture compared to SNPs), CNV-GWAS differs fundamentally from SNP-GWAS in terms of the number of tests performed. Therefore, a nominal threshold (here, P < 0.01) was adopted to prioritize CNVs significantly associated with our phenotype (Reid et al., 2019; Stylianou et al., 2024).

Gene annotation within CNVs significantly associated with BRD was performed using the Genome Data Viewer tool from the NCBI database, freely available online (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/gdv/browser/gene/?id=785567). Lastly, the functional gene annotation was performed using both the Cytoscape software (Shannon et al., 2003) and the DAVID online database (https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov).

2.2.2 ROH detection and inbreeding coefficient values (FROH)

ROH identification was performed using the “detectRUNS” library (RStudio software), applying the “consecutive RUNS” method. The following parameters were set, as previously reported in other studies using the same SNP chip (Bernini et al., 2023; Punturiero et al., 2023): i) minimum number of SNPs: 30; 2) minimum ROH length: 1,000 kb; iii) no missing genotypes nor heterozygous SNPs allowed; and iv) maximum gap between consecutive SNPs of 1 Mbp.

To assess potential differences in the distribution of ROH between R-BRD and S-BRD calves, a “fixed window approach” was implemented based on the ROH output generated using the detectRUNS R package. A custom R script was developed to scan the genome using non-overlapping fixed-size windows of 100 kb, to avoid overestimating the extent of overlapping ROH regions and to balance genomic resolution and statistical power (Cozzi et al., 2015). This window size allows meaningful group-level comparisons without introducing excessive fragmentation or artificial overlap of signals. For each window, the number of individuals in which at least one ROH overlapped the interval was counted separately for the S-BRD and R-BRD groups. ROH frequencies were then calculated as the proportion of individuals with an ROH in the given window relative to the total number of individuals within each group. To assess whether ROH occurrence differed significantly between groups, Fisher’s exact test was applied to each window. To reduce the risk of false positives due to marginal differences, an additional filter was applied: only windows showing a minimum absolute difference of at least 10 individuals between groups were retained. This threshold helped ensure that only biologically meaningful differences in ROH distribution were considered.

This approach enabled the identification of genomic regions where ROHs were significantly more frequent in one group compared to the other, including i) regions where the conventional “Top_ROH” threshold (e.g., >50% of individuals with ROH; see Additional File 1) was not reached by either group and ii) regions where both groups exceeded this threshold but showed statistically significant differences in ROH frequency. Overall, this strategy provided a more refined and complementary perspective on ROH distribution, enabling the detection of regions potentially associated with genetic resistance or susceptibility to BRD.

Genes within these windows were annotated using the same pipeline adopted for CNVs.

Additionally, the genomic inbreeding coefficient (FROH) for all samples within five class of length (<2 Mbp, 2–4 Mbp, 4–8 Mbp, 8–16 Mbp, and >16 Mbp) were calculated as the ratio between the sum of length of all ROH segment per cow and the length of the autosomal genome covered by SNPs (formula implemented in DetectRUNs library of RStudio).

3 Results

3.1 Copy number variant identification and GWAS

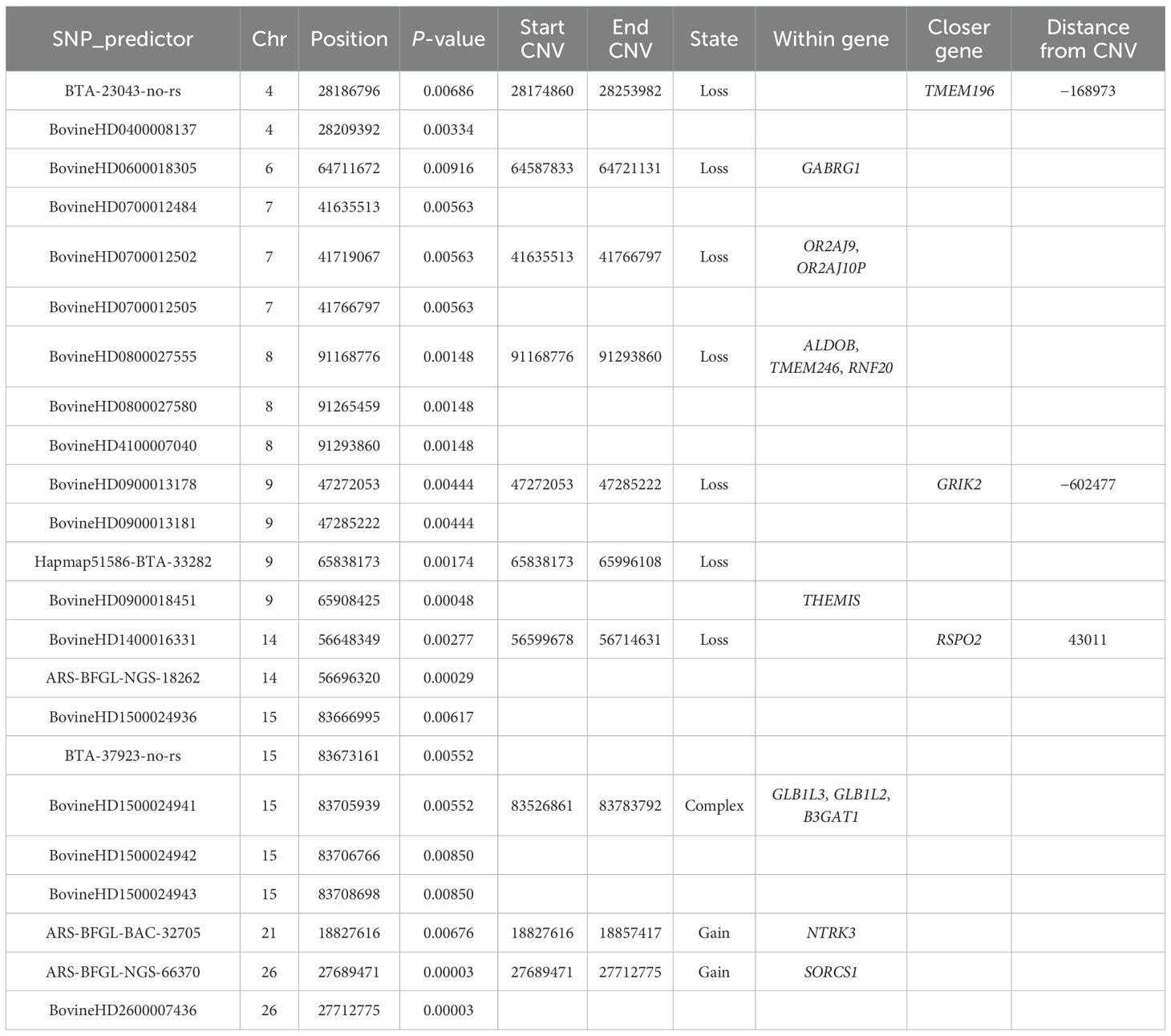

A total of 2,666 CNVs were identified across all calves, after quality control filtering, with descriptive statistics summarized in Table 1. A 100% correlation was observed between the number of calves in the R-BRD and S-BRD groups and the corresponding total number of CNVs, including both gains and losses. Figure 1 shows the graphical representation of the GWAS analysis result.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the identified copy number variants (CNVs) in R-BRD and S-BRD calves.

Figure 1. Graphical representation of the CNV-GWAS results. The gray line shows the significance threshold, corresponding to a P-value of 0.01.

Table 2 presents the results of the GWAS. As shown, 23 SNP_predictors were identified as significantly associated with our phenotype. In SVS, a SNP_predictor refers to a variable that treats CNVs as genetic markers, enabling the application of standard association tests to structural variants. These markers allowed the definition of 10 CNVRs, consisting of 7 losses, 1 complex, and 2 gains. Each CNV region can be defined by one or more adjacent SNP_predictors, and the boundaries of a region correspond to the CNV segment they tag. Gene annotation was performed for genes located either within a CNVR (n = 12) or in its proximity (within 1 Mb from the start or end of the CNV; n = 3). These were designated as candidate genes potentially involved in BRD susceptibility or resistance.

3.2 ROH and FROH

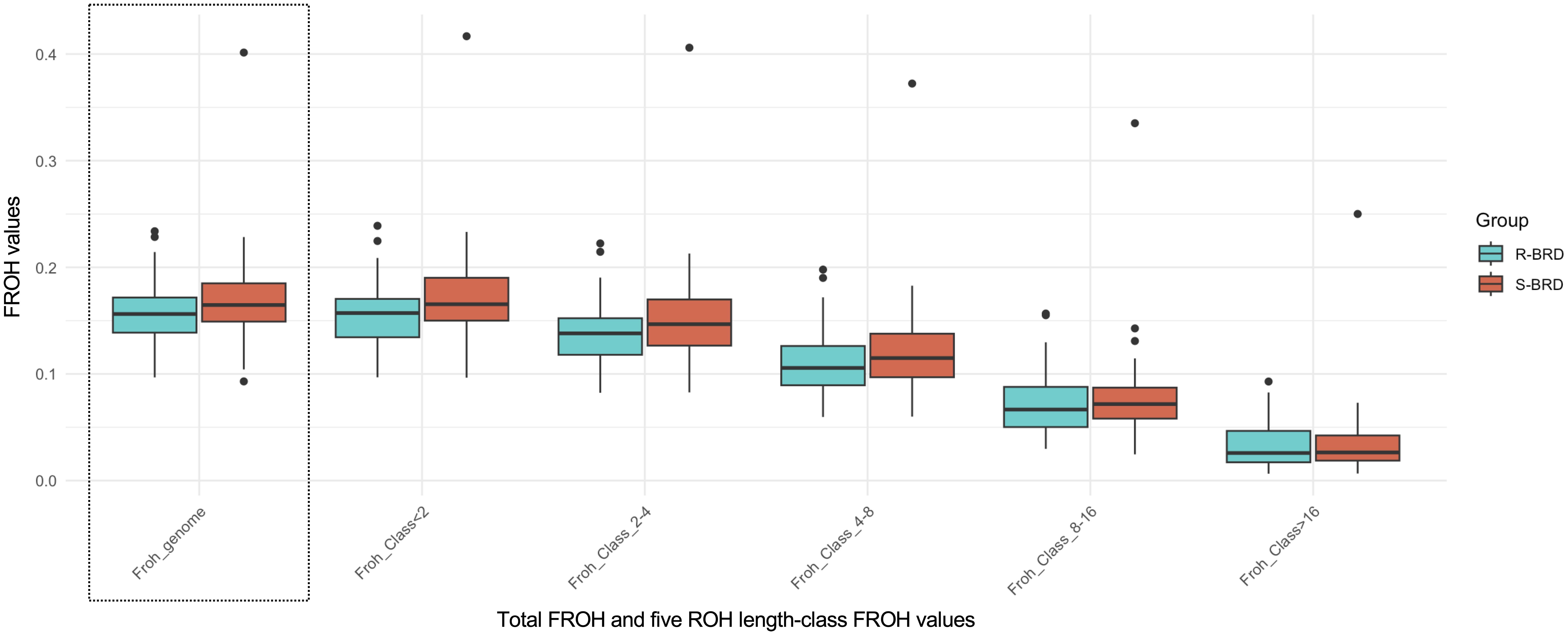

A total of 4,249 ROH were identified in S-BRD (n = 46) and 3,977 in R-BRD (n = 47) calves, with an average length of 4.51 and 4.43 Mbp, respectively. In both groups, the majority of ROH fell within the short-to-medium range (1–8 Mbp), whereas long ROH segments (≥8 Mbp) were less frequent. ROH in the longest length class accounted for 3.6% and 4% of the total ROH in the S-BRD and R-BRD groups, respectively. This overall distribution pattern likely reflects comparable breeding choices among farmers (e.g., for productive, functional, and morphological traits) in recent years (Mastrangelo et al., 2018; Wirth et al., 2024). The average FROH coefficients calculated from ROH longer than 16 Mbp were very similar between S-BRD and R-BRD calves, both averaging approximately 3%.

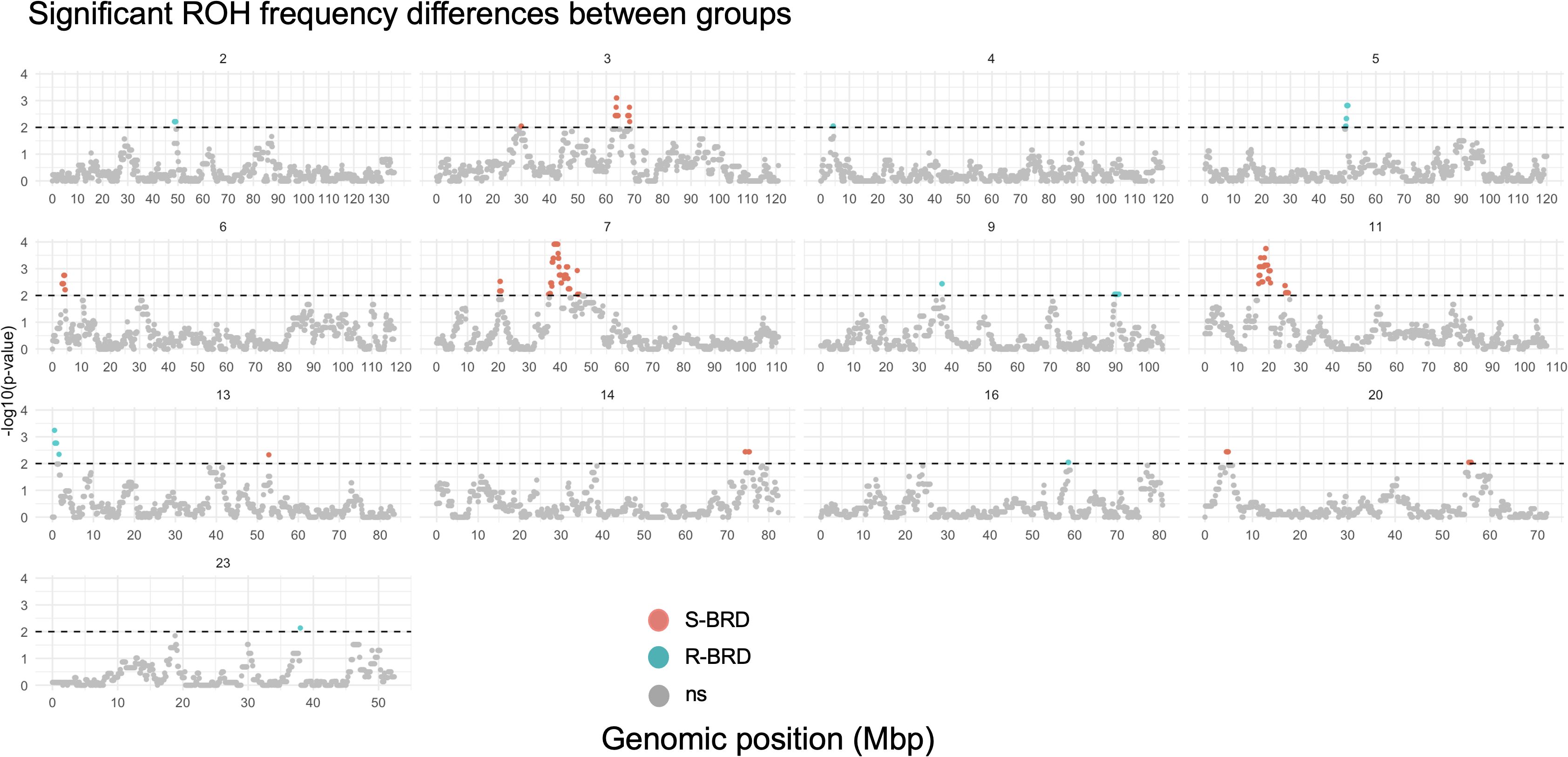

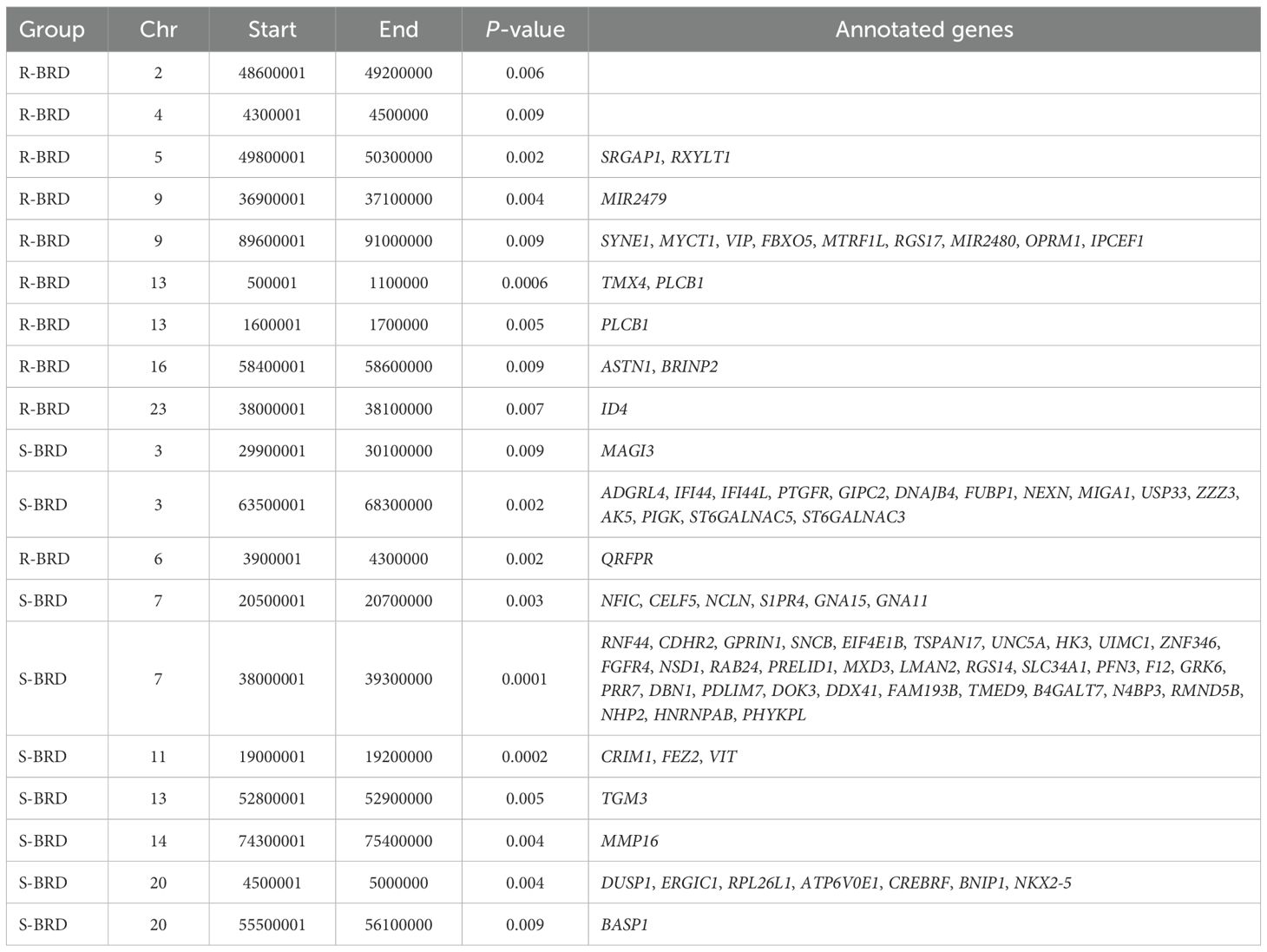

Table 3 reports the genomic windows where ROH frequencies significantly differed between R-BRD and S-BRD calves. A total of 19 regions were identified, with 10 enriched in R-BRD calves and 9 in S-BRD calves. Notably, the most significant differences in the S-BRD group were observed on BTAs 3, 7, and 11, while R-BRD calves showed enriched ROH regions distributed across several chromosomes, including BTAs 5 and 13 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Manhattan plots showing genomic windows where ROH frequencies differ significantly between R-BRD and S-BRD calves (Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.01).“ ns” indicates non-significant regions. Numbers at the top of each plot correspond to the chromosomes.

FROH coefficients (Figure 3), calculated across the five ROH length classes for each calf in the two groups, were slightly lower in R-BRD calves compared to S-BRD. However, these differences alone are unlikely to account for the observed variation in resistance to BRD-related lung lesions.

Figure 3. Boxplots comparing the genomic inbreeding coefficient (FROH) between R-BRD and S-BRD calves. Results are displayed as both the total FROH (Froh_genome) and the values calculated across five ROH length classes. A dashed outline marks the distribution of the total FROH.

4 Discussion

This study builds upon previous work that employed a selective genotyping approach to investigate genetic resistance to BRD in Holstein calves. By leveraging the same well-characterized cohort (R-BRD vs. S-BRD) (Strillacci et al., 2025), we extended the genomic analysis beyond the traditional SNP-based GWAS to include both CNV-based association testing and ROH characterization of the two groups. The selective genotyping design, which involved a one-gate reverse flow strategy across all enrolled farms, ensured that both R-BRD and S-BRD calves originated from a common source population with comparable exposure to BRD pathogens. This design reduced the risk of confounding due to differential pathogen pressure and yielded results that are robust and potentially generalizable (Rutjes et al., 2005) as discussed in our previous study (Strillacci et al., 2025).

While our previous findings highlighted candidate QTL associated with BRD resistance, in the present study, several CNVs were significantly associated with the trait, supporting the contribution of structural variation to the genetic architecture underlying BRD susceptibility. In parallel, the ROH analysis revealed distinct patterns of homozygosity between the two groups, including genomic regions that may reflect historical selection or ongoing selective pressure related to immune function.

Nonetheless, as previously discussed, the observational nature of the study, based on a single TUS assessment during the preweaning period, limits our ability to capture the temporal dynamics of lung lesion progression. Consequently, our results primarily reflect innate, rather than adaptive, immune mechanisms underlying resistance to BRD (Chase et al., 2008). In this context, the identification of CNVs and ROH regions associated with resistance traits is particularly valuable, as it highlights specific genomic loci potentially involved in early-life immune defense mechanisms.

To better understand the biological relevance of the identified genomic regions, we examined the gene content within both the CNV regions significantly associated with TUS-detected lung lesions and the ROH segments that differed significantly in frequency between the R-BRD and S-BRD groups. The functional annotation of these genes provides insights into molecular mechanisms potentially underlying resistance or susceptibility to BRD-related lung lesions. Notably, several genes within the associated regions have previously been linked to production (SORCS1, RMND5B) (Palombo et al., 2018; Honerlagen et al., 2021), morphological (TSPAN17, HK3, UIMC1, and UNC5A) (MaChado et al., 2022), and reproductive traits in cattle (PLCB1, SYNE1) (Galliou et al., 2020). Their presence within BRD-associated loci may suggest pleiotropic effects or reflect historical selection strategies that, while trying to improve productivity or fertility, may have inadvertently affected disease susceptibility. This is particularly relevant in the context of Holstein breeding, where strong genetic correlations among health, production, and reproductive traits have been well documented (Hu et al., 2024). Although direct evidence of genetic correlations between BRD resistance and production or fertility traits in Holsteins remains limited, findings from other infectious diseases, especially mastitis, offer valuable parallels (Rupp and Boichard, 2003). An example of these interrelated traits is the observed association between BRD-related lung consolidation in calves and adverse long-term outcomes, such as reduced milk yield in first lactation, delayed age at first calving, and an increased incidence of dystocia (Quick et al., 2020).

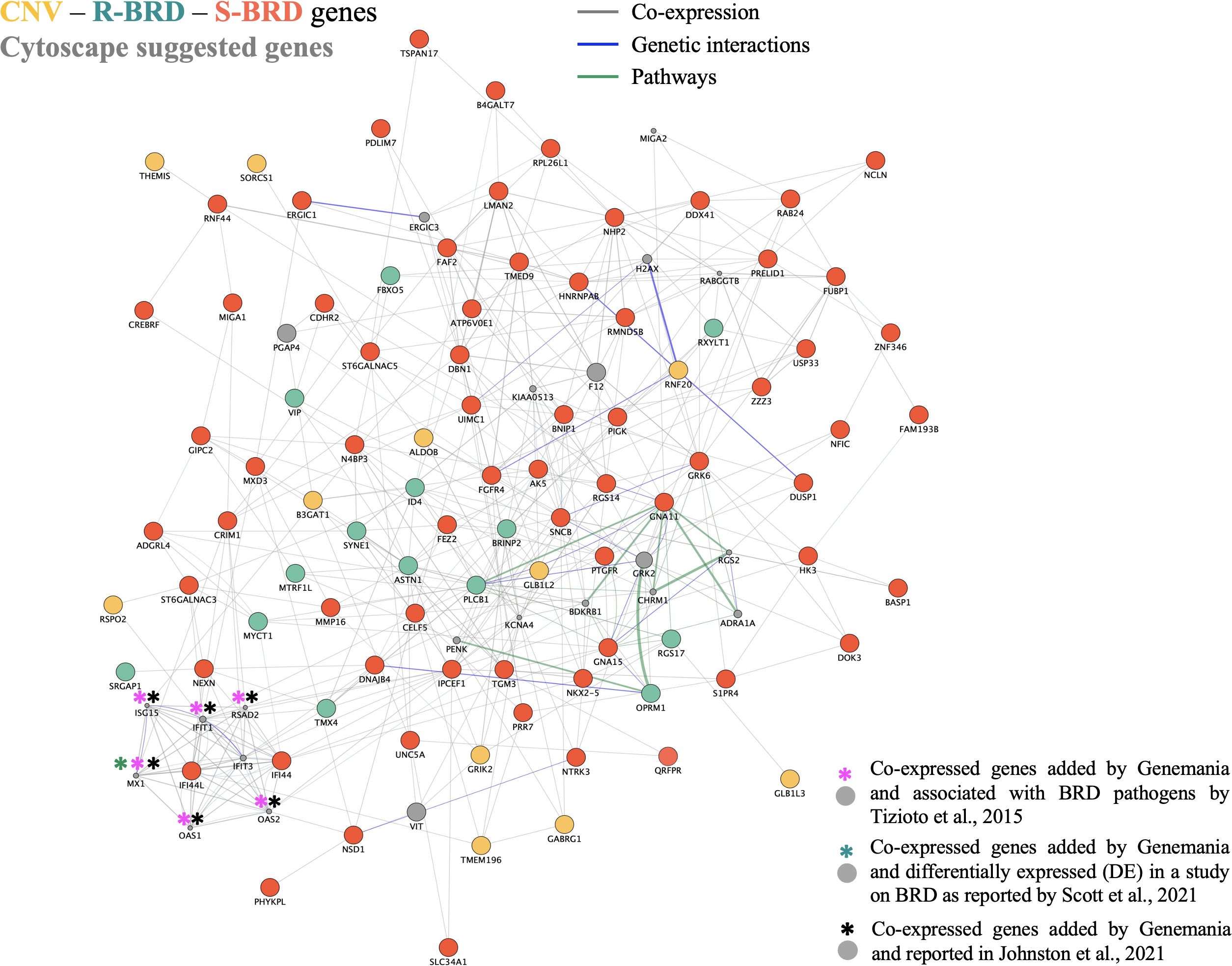

To explore the potential interactions among the identified genes and gain a broader understanding of the underlying biological pathways, we constructed a gene network using GeneMANIA implemented in the Cytoscape software. Figure 4 illustrates the resulting network, which includes 94 of the 102 genes listed in Tables 2, 3 (comprising those from the CNV-GWAS and ROH analyses). The network highlights both known and predicted functional relationships. In the network, the gray full-circled genes were added by the GeneMANIA tool as predicted interaction partners, based on integrated reference datasets using the Homo sapiens background. Notably, eight of these genes (including IFI44L, identified in the S-BRD group) are involved in response to virus (GO:0009615), as detailed in Supplementary Table S1. This biological process is a key component of innate immunity, involving the recognition of viral nucleic acids, activation of antiviral signaling cascades, and induction of interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines to limit viral replication and spread (Schneider et al., 2014). The response to acetylcholine (GO:1905144), involving both genes here identified as candidate genes (PLCB1, OPRM1, GNA11, GNA15) and gray full-circled genes (GRK2, CHRM1), participates in the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, regulating cytokine production and modulating inflammation during infections (Tracey, 2009; Pavlov et al., 2018). In addition, the gray full-circled RGS2, ADRA1A, and CHRM1 genes, together with PTGFR, OPRM1, GNA11, VIP, S1PR4, ADGRL4, and GNA15 identified in this study, are involved in G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling pathways linked to cyclic nucleotide second messengers (GO:0007187), particularly within the adenylate cyclase-modulating GPCR signaling pathway (GO:0007188). These signaling cascades regulate intracellular cAMP levels, which are critical for modulating immune cell activation, cytokine production, and the resolution of inflammation during infection. Dysregulation of these signaling pathways may compromise host immune defense, and several pathogens are known to exploit GPCR–cAMP signaling to modulate host responses and promote infection (Aronoff et al., 2004; Lattin et al., 2008; Smrcka, 2013). When applying a q-value threshold of <0.10, the GO term “regulation of phospholipase activity” (GO:0010517) was also enriched (Supplementary Table S1). This category includes RGS2 and ADRA1A (gray genes) and S1PR4, NTRK3, and GNA15 (detected in this study), suggesting a possible role of phospholipase-mediated pathways in host defense. Phospholipases play essential roles in cellular signaling and membrane remodeling, and some isoforms modulate inflammatory processes and pathogen–host interactions, the production of lipid mediators, and the activation of immune cells (Dennis et al., 2011; Murakami et al., 2011). Moreover, various pathogens have developed mechanisms to subvert host phospholipase signaling, thereby facilitating infection and survival. In the gene network, the gray full-circle genes marked with a colored asterisk (*) correspond to candidate or differentially expressed genes identified in other studies focused on BRD (Tizioto et al., 2015; Johnston et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2021).

Figure 4. Gene interaction network generated using the GeneMANIA tool implemented in Cytoscape. Co-expressed genes are the ones found in the entire Cytoscape database (Homo sapiens species as background). Gray full-circled genes identified in other studies and added by Cytoscape. Asterisks (*) indicate genes previously associated with BRD in other studies.

In addition to the network-based functional insights, the presence of CNVs affecting four genes (THEMIS, RNF20, B3GAT1, and RSPO2) highlights their potential involvement in immune responses. These genes are functionally associated with T-cell development, chromatin remodeling in antiviral defense, and epithelial barrier integrity maintenance, all critical components of the host’s response to respiratory pathogens. The THEMIS gene encodes a T-cell-specific protein essential for thymocyte selection and the proper maturation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the thymus. Its absence impairs T-cell development and weakens immune responses (Lesourne et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2022). However, its potential role in the immune response to BRD may relate to the well-documented importance of CD8+ T cells in antiviral defense in other contexts (Schmidt and Varga, 2018). RNF20 encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in chromatin remodeling through histone H2B monoubiquitination, which is critical for antiviral responses. In humans, RNF20 is targeted by SARS-CoV-2 to evade immunity (Zhang et al., 2021). Given the role of bovine coronavirus in BRD, a similar immune evasion mechanism may occur in cattle, and a loss of CNV at this locus could compromise antiviral defense. B3GAT1 encodes a glycosyltransferase that inhibits viral entry by interfering with sialic acid receptor formation on host cells. It shows broad antiviral activity against sialic-acid-dependent viruses (Trimarco et al., 2022). Deletion of this gene may impair this protective mechanism, increasing susceptibility to BRD pathogens. Finally, RSPO2, a regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway, is essential for lung development and maintaining alveolar barrier integrity (Bell et al., 2008; Jackson et al., 2020). It may help limit neutrophil infiltration and inflammation in the lung, processes implicated in BRD pathogenesis.

4.1 Comparison with references

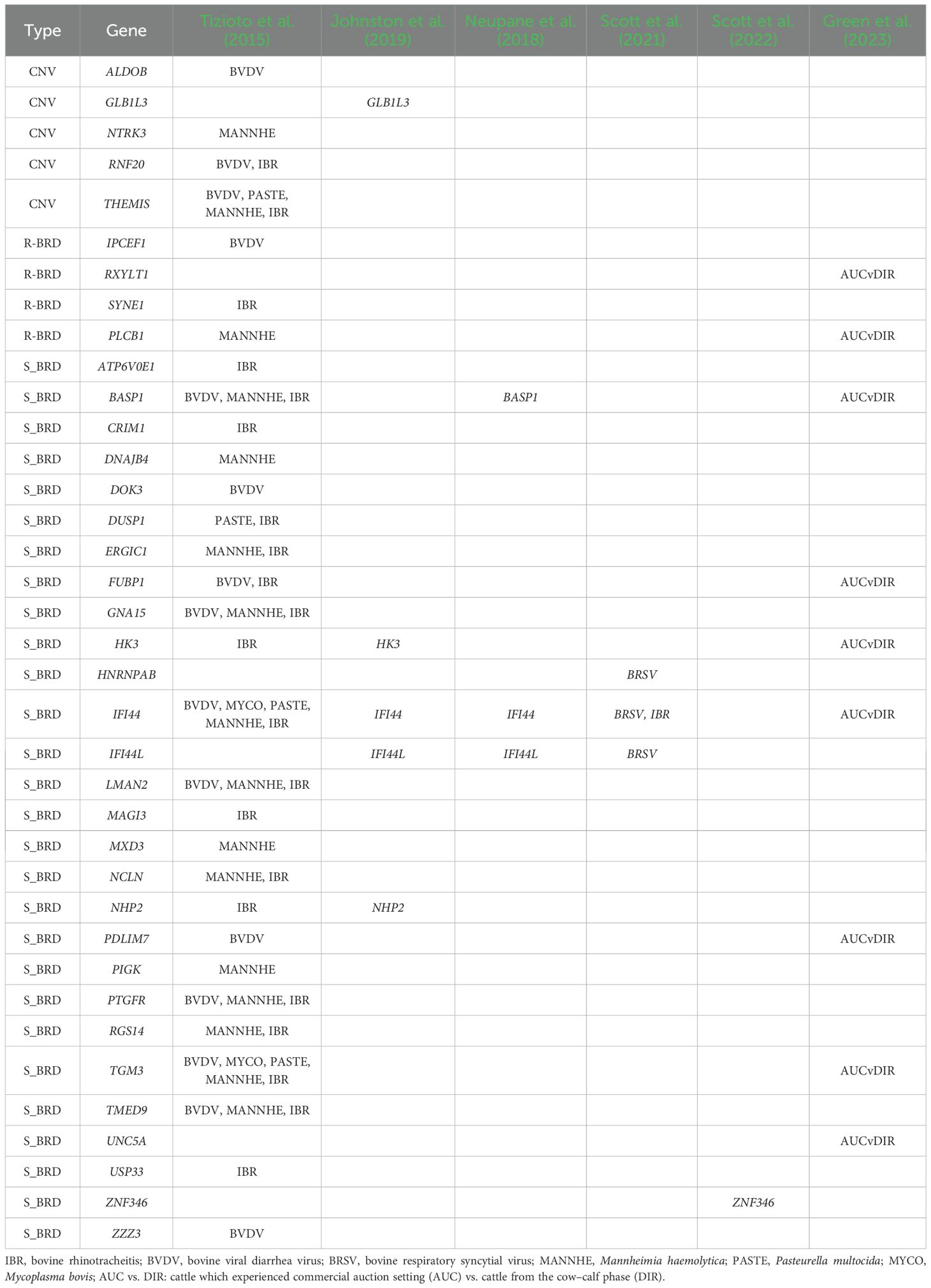

The comparison with the current literature (Table 4) (Tizioto et al., 2015; Neupane et al., 2018; Johnston et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2021, 2022; Green et al., 2023) allowed us to identify 37 protein-coding genes, representing 36.27% of the 102 genes listed in Tables 2, 3, that had already been associated with BRD. Among these, five genes (PLCB1, FUBP1, NHP2, PDLIM3, and TGM3) were reported in at least two independent studies; BASP1, HK3, and IFI44L emerged as common candidate genes in at least three BRD-related studies, while IFI44 stood out as one of the most consistently identified genes, being reported in six studies, including the present work.

Table 3. Details of ROH resulted significantly different in terms of frequencies between R-BRD and S-BRD calves.

Table 4. List of genes reported in Tables 2, 3 already associated with bovine respiratory disease in previous studies.

By integrating the data from this study with those from the previous SNP-based GWAS (Strillacci et al., 2025), whose GeneMANIA network is shown in Supplementary Figure S1, we identified several enriched pathways that had not been previously reported but which may play roles in modulating host responses to BRD. Among these, the enrichment of the “estrogen signaling pathway” (KEGG:bta04915) (Supplementary Table S2) highlights the multifaceted role of estrogens in immune defense. Estrogen is not only central to reproductive physiology but also crucial for immune regulation during viral infection (Harding and Heaton, 2022). Additionally, estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), which are expressed in immune cells and respiratory tissues, regulate cytokine production, T-cell responses, and epithelial barrier integrity. Notably, estrogen receptor activation has been shown to reduce viral replication in bronchial epithelial cells, suggesting that this pathway may confer protection against respiratory viral infections (Millas and Duarte Barros, 2021).

The “calcium signaling pathway” (KEGG: bta04020) (Supplementary Table S2) was also significantly enriched in our analysis, suggesting a potential role in modulating host–pathogen interactions during BRD. Calcium (Ca²+) is a ubiquitous and versatile second messenger that regulates essential cellular functions such as immune activation and inflammation. Notably, the disruption of Ca²+ homeostasis is a common viral strategy to manipulate host cell signaling pathways to their advantage (Chen et al., 2019; Qu et al., 2022). Calcium signaling is crucial for multiple stages of the viral life cycle, including entry, genome replication, virion assembly, and release. For instance, several Ca²+ channel blockers have shown antiviral activity by inhibiting infections caused by influenza viruses, flaviviruses, and coronaviruses. Through manipulation of host cell Ca²+ signaling pathways, viruses can also modulate apoptosis and evade immune responses, ultimately facilitating persistent infection (Qu et al., 2022). Although a direct association between the “parathyroid hormone signaling pathway” (KEGG:bta04928) and infectious respiratory diseases has not been clearly established in cattle, its potential relevance may lie in its role in the regulation of calcium homeostasis. As discussed above, calcium signaling plays a critical role in viral infection dynamics, and parathyroid hormone (PTH) is a key regulator of systemic calcium levels. In humans, PTH not only regulates systemic calcium balance but also modulates immune cell functions, particularly in T cells and macrophages, thereby influencing inflammatory responses and susceptibility to infection (Geara et al., 2010; Comănescu et al., 2025). These findings suggest that genetic variation in components of the PTH pathway could indirectly affect host resistance to respiratory pathogens through its immunomodulatory effects.

5 Conclusions

This study demonstrates that integrating CNV and ROH analyses alongside SNP-based approaches can significantly enhance our understanding of the complex genetic architecture underlying BRD. Structural variants such as CNVs and ROHs provide complementary genomic insights that capture disease susceptibility signals not detected by SNP markers alone. Our findings highlight the potential of leveraging structural genomic information to inform precision breeding strategies aimed at improving disease resilience in cattle, thereby reducing reliance on antimicrobial treatments. Notably, this is the first study to simultaneously integrate CNV-based GWAS, ROH detection, and SNP-association analysis within a selectively genotyped cohort of Holstein calves phenotypically classified using TUS-detected lung lesions for BRD resistance. The rigorous phenotyping protocol used, which combined detailed clinical scoring and thoracic ultrasound, strengthens the accuracy of case/control classification and underpins the robustness of our findings.

Several key genes emerged from this integrative analysis as particularly relevant to BRD susceptibility and immune defense. Among these, IFI44 and IFI44L were consistently identified across multiple independent studies and are involved in antiviral responses and interferon signaling. PLCB1, GNA15, and S1PR4, enriched in pathways regulating phospholipase activity and G protein-coupled receptor signaling, play roles in the modulation of inflammation through calcium- and cAMP-dependent mechanisms. THEMIS and RNF20, affected by CNVs, are implicated in T-cell development and chromatin remodeling in antiviral defense, whereas RSPO2 contributes to epithelial barrier integrity in the lung. These loci collectively point to a network of genes governing innate immune regulation, antiviral response, and epithelial protection, which are central to host resistance against respiratory pathogens. Furthermore, pathway analysis revealed the involvement of estrogen and calcium signaling pathways—mechanisms not previously emphasized in BRD genetics but with strong immunomodulatory relevance. Their implication highlights new biological perspectives linking endocrine and immune functions in respiratory disease resilience.

Future research incorporating longitudinal monitoring of both clinical and subclinical BRD phenotypes, alongside high-resolution genomic data, will be essential to validate these results and clarify whether the detected genetic signals also contribute to long-term and adaptive immune responses. Collectively, these insights pave the way toward more effective genomic-informed breeding strategies that enhance cattle health and sustainability.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

All the procedures conformed to European and Italian laws (2010/63/UE D. and Lgs n. 2014/26) and were approved by the Animal Welfare Body of the Università degli Studi di Milano (OPBA) and by the Italian Minister of Health (protocol number OPBA_68_2023). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

FB: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. ABo: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AD: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. VB: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. GL: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. ABa: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. ABa received funding for this study that was carried out within the Agritech National Research Center and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (PIANO NAZIONALE DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA (PNRR) – MISSIONE 4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.4 – D.D. 1032 17/06/2022, CN00000022). The authors acknowledge the support of the University of Milan’s departmental fund (ABo received the “Line 2 Research Support Plan”).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used exclusively to improve the English grammar and style; no content generation or data analysis was performed.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions; neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2025.1700819/full#supplementary-material

References

Ackermann M. R., Derscheid R., and Roth J. A. (2010). Innate immunology of bovine respiratory disease. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 26, 215. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2010.03.001

Aronoff D. M., Canetti C., and Peters-Golden M. (2004). Prostaglandin E2 inhibits alveolar macrophage phagocytosis through an E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in intracellular cyclic AMP. J. Immunol. 173, 559–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.559

Bell S. M., Schreiner C. M., Wert S. E., Mucenski M. L., Scott W. J., and Whitsett J. A. (2008). R-spondin 2 is required for normal laryngeal-tracheal, lung and limb morphogenesis. Development 135(6):1049–58. doi: 10.1242/dev.013359

Bernini F., Punturiero C., Vevey M., Blanchet V., Milanesi R., Delledonne A., et al. (2023). Assessing major genes allele frequencies and the genetic diversity of the native Aosta cattle female population. Ital J. Anim. Sci. 22, 1008–1022. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2023.2259221

Biscarini F., Biffani S., Morandi N., Nicolazzi E. L., and Stella A. (2016) Using runs of homozygosity to detect genomic regions associated with susceptibility to infectious and metabolic diseases in dairy cows under intensive farming conditions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1601.07062. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1601.07062

Buczinski S. and Pardon B. (2020). Bovine respiratory disease diagnosis: What progress has been made in clinical diagnosis? Vet. Clinics: Food Anim. Pract. 36, 399–423. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2020.03.004

Chase C. C. L., Hurley D. J., and Reber A. J. (2008). Neonatal immune development in the calf and its impact on vaccine response. Vet. Clinics North America: Food Anim. Pract. 24, 87–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2007.11.001

Chen X., Cao R., and Zhong W. (2019). Host calcium channels and pumps in viral infections. Cells 9, 94. doi: 10.3390/cells9010094

Comănescu M.-P., Boişteanu O., Hînganu D., Hînganu M. V., Grigorovici R., and Grigorovici A. (2025). Perspectives on the parathyroid–thymus interconnection—A literature review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 6000. doi: 10.3390/ijms26136000

Cozzi P., Milanesi L., and Bernardi G. (2015). Segmenting the human genome into isochores. Evol. Bioinf. 11, EBO.S27693. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S27693

Darvasi A. and Soller M. (1992). Selective genotyping for determination of linkage between a marker locus and a quantitative trait locus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 85, 353–359. doi: 10.1007/BF00222881

Dennis E. A., Cao J., Hsu Y.-H., Magrioti V., and Kokotos G. (2011). Phospholipase A2 enzymes: physical structure, biological function, disease implication, chemical inhibition, and therapeutic intervention. Chem. Rev. 111, 6130–6185. doi: 10.1021/cr200085w

Durán Aguilar M., Román Ponce S. I., Ruiz López F. J., González Padilla E., Vásquez Peláez C. G., Bagnato A., et al. (2017). Genome‐wide association study for milk somatic cell score in holstein cattle using copy number variation as markers. J Animal Breeding and Genetics. 134 (1), 49–59. doi: 10.1111/jbg.12238

Galliou J. M., Kiser J. N., Oliver K. F., Seabury C. M., Moraes J. G. N., Burns G. W., et al. (2020). Identification of loci and pathways associated with heifer conception rate in US Holsteins. Genes (Basel) 11, 767. doi: 10.3390/genes11070767

Geara A. S., Castellanos M. R., Bassil C., Schuller-Levis G., Park E., Smith M., et al. (2010). Effects of parathyroid hormone on immune function. J. Immunol. Res. 2010, 418695. doi: 10.1155/2010/418695

Green M. M., Woolums A. R., Karisch B. B., Harvey K. M., Capik S. F., and Scott M. A. (2023). Influence of the at-arrival host transcriptome on bovine respiratory disease incidence during backgrounding. Vet. Sci. 10, 211. doi: 10.3390/vetsci10030211

Harding A. T. and Heaton N. S. (2022). The impact of estrogens and their receptors on immunity and inflammation during infection. Cancers (Basel) 14, 909. doi: 10.3390/cancers14040909

Honerlagen H., Reyer H., Oster M., Ponsuksili S., Trakooljul N., Kuhla B., et al. (2021). Identification of genomic regions influencing N-metabolism and N-excretion in lactating Holstein-Friesians. Front. Genet. 12, 699550. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.699550

Hu H. H., Mu T., Zhang Z. B., Zhang J. X., Feng X., Han L. Y., et al. (2024). Genetic analysis of health traits and their associations with longevity, fertility, production, and conformation traits in Holstein cattle. Animal 18, 101177. doi: 10.1016/j.animal.2024.101177

Jackson S. R., Costa M. F. D. M., Pastore C. F., Zhao G., Weiner A. I., Adams S., et al. (2020). R-spondin 2 mediates neutrophil egress into the alveolar space through increased lung permeability. BMC Res. Notes 13, 54. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-4930-8

Johnston D., Earley B., McCabe M. S., Lemon K., Duffy C., McMenamy M., et al. (2019). Experimental challenge with bovine respiratory syncytial virus in dairy calves: bronchial lymph node transcriptome response. Sci. Rep. 9, 14736. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51094-z

Lattin J. E., Schroder K., Su A. I., Walker J. R., Zhang J., Wiltshire T., et al. (2008). Expression analysis of G Protein-Coupled Receptors in mouse macrophages. Immunome Res. 4, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/1745-7580-4-5

Lesourne R., Uehara S., Lee J., Song K., Li L., Pinkhasov J., et al. (2010). Themis, a T cell-specific protein important for late thymocyte development. Nat. Immunol. 11, 97. doi: 10.1038/ni0110-97d

Li J., Mukiibi R., Jiminez J., Wang Z., Akanno E. C., Timsit E., et al. (2022). Applying multi-omics data to study the genetic background of bovine respiratory disease infection in feedlot crossbred cattle. Front. Genet. 13, 1046192. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.1046192

Lipkin E., Strillacci M. G., Eitam H., Yishay M., Schiavini F., Soller M., et al. (2016). The use of Kosher phenotyping for mapping QTL affecting susceptibility to Bovine respiratory disease. PloS One 11, e0153423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153423

MaChado P. C., Brito L. F., Martins R., Pinto L. F. B., Silva M. R., and Pedrosa V. B. (2022). Genome-wide association analysis reveals novel loci related with visual score traits in nellore cattle raised in pasture–based systems. Animals 12, 3526. doi: 10.3390/ani12243526

MaChado L. R. and Ottolini B. (2015). An evolutionary history of defensins: a role for copy number variation in maximizing host innate and adaptive immune responses. Front. Immunol. 6, 115. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00115

Mastrangelo S., Sardina M. T., Tolone M., Di Gerlando R., Sutera A. M., Fontanesi L., et al. (2018). Genome-wide identification of runs of homozygosity islands and associated genes in local dairy cattle breeds. Animal 12, 2480–2488. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118000629

McGuirk S. M. and Peek S. F. (2014). Timely diagnosis of dairy calf respiratory disease using a standardized scoring system. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 15, 145–147. doi: 10.1017/S1466252314000267

Millas I. and Duarte Barros M. (2021). Estrogen receptors and their roles in the immune and respiratory systems. Anat Rec 304, 1185–1193. doi: 10.1002/ar.24612

Mills R. E., Walter K., Stewart C., Handsaker R. E., Chen K., Alkan C., et al. (2011). Mapping copy number variation by population-scale genome sequencing. Nature 470, 59–65. doi: 10.1038/NATURE09708

Murakami M., Taketomi Y., Miki Y., Sato H., Hirabayashi T., and Yamamoto K. (2011). Recent progress in phospholipase A2 research: from cells to animals to humans. Prog. Lipid Res. 50, 152–192. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.12.001

Neupane M., Kiser J. N., and Neibergs H. L. (2018). Gene set enrichment analysis of SNP data in dairy and beef cattle with bovine respiratory disease. Anim. Genet. 49, 527–538. doi: 10.1111/age.12718

Oliveira H. R., Chud T., Oliveira G. A., Hermisdorff I. C., Narayana S. G., Rochus C. M., et al. (2024). Genome-wide association analyses reveals copy number variant regions associated with reproduction and disease traits in Canadian Holstein cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 107 (9), 7052–7063. doi: 10.3168/jds.2023-24295

Ollivett T. L. and Buczinski S. (2016). On-farm use of ultrasonography for bovine respiratory disease. Vet. Clin.: Food Anim. Pract. 32, 19–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2015.09.001

Ollivett T. L., Caswell J. L., Nydam D. V., Duffield T., Leslie K. E., Hewson J., et al. (2015). Thoracic ultrasonography and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis in H olstein calves with subclinical lung lesions. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 29, 1728–1734. doi: 10.1111/jvim.13605

Overton M. W. (2020). Economics of respiratory disease in dairy replacement heifers. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 21, 143–148. doi: 10.1017/S1466252320000250

Palombo V., Milanesi M., Sgorlon S., Capomaccio S., Mele M., Nicolazzi E., et al. (2018). Genome-wide association study of milk fatty acid composition in Italian Simmental and Italian Holstein cows using single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. J. Dairy Sci. 101, 11004–11019. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-14413

Pavlov V. A., Chavan S. S., and Tracey K. J. (2018). Molecular and functional neuroscience in immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 36, 783–812. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053158

Punturiero C., Milanesi R., Bernini F., Delledonne A., Bagnato A., and Strillacci M. G. (2023). Genomic approach to manage genetic variability in dairy farms. Ital J. Anim. Sci. 22, 769–783. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2023.2243977

Qu Y., Sun Y., Yang Z., and Ding C. (2022). Calcium ions signaling: targets for attack and utilization by viruses. Front. Microbiol. 13, 889374. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.889374

Quick A. E., Ollivett T. L., Kirkpatrick B. W., and Weigel K. A. (2020). Genomic analysis of bovine respiratory disease and lung consolidation in preweaned Holstein calves using clinical scoring and lung ultrasound. J. Dairy Sci. 103, 1632–1641. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-16531

Reid B. M., Permuth J. B., Chen Y. A., Fridley B. L., Iversen E. S., Chen Z., et al. (2019). Genome-wide analysis of common copy number variation and epithelial ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 28, 1117–1126. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0833

Rupp R. and Boichard D. (2003). Genetics of resistance to mastitis in dairy cattle. Vet. Res. 34, 671–688. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2003020

Rutjes A. W. S., Reitsma J. B., Vandenbroucke J. P., Glas A. S., and Bossuyt P. M. M. (2005). Case–control and two-gate designs in diagnostic accuracy studies. Clin. Chem. 51, 1335–1341. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.048595

Salehian-Dehkordi H., Huang J.-H., Pirany N., Mehrban H., Lv X.-Y., Sun W., et al. (2023). Genomic landscape of copy number variations and their associations with climatic variables in the world’s sheep. Genes (Basel) 14, 1256. doi: 10.3390/genes14061256

Salehian-Dehkordi H., Xu Y.-X., Xu S.-S., Li X., Luo L.-Y., Liu Y.-J., et al. (2021). Genome-wide detection of copy number variations and their association with distinct phenotypes in the world’s sheep. Front. Genet. 12, 670582. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.670582

Schmidt M. E. and Varga S. M. (2018). The CD8 T cell response to respiratory virus infections. Front. Immunol. 9, 678. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00678

Schneider W. M., Chevillotte M. D., and Rice C. M. (2014). Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120231

Scott M. A., Woolums A. R., Swiderski C. E., Finley A., Perkins A. D., Nanduri B., et al. (2022). Hematological and gene co-expression network analyses of high-risk beef cattle defines immunological mechanisms and biological complexes involved in bovine respiratory disease and weight gain. PloS One 17, e0277033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277033

Scott M. A., Woolums A. R., Swiderski C. E., Perkins A. D., and Nanduri B. (2021). Genes and regulatory mechanisms associated with experimentally-induced bovine respiratory disease identified using supervised machine learning methodology. Sci. Rep. 11, 22916. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02343-7

Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N. S., Wang J. T., Ramage D., et al. (2003). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303

Smrcka A. V. (2013). Molecular targeting of Gα and Gβγ subunits: a potential approach for cancer therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34, 290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.02.006

Strillacci M. G., Ferrulli V., Bernini F., Pravettoni D., Bagnato A., Martucci I., et al. (2025). Genomic analysis of bovine respiratory disease resistance in preweaned dairy calves diagnosed by a combination of clinical signs and thoracic ultrasonography. PloS One 20, e0318520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0318520

Stylianou C. E., Wiggins G. A. R., Lau V. L., Dennis J., Shelling A. N., Wilson M., et al. (2024). Germline copy number variants and endometrial cancer risk. Hum. Genet. 143, 1481–1498. doi: 10.1007/s00439-024-02707-9

Taylor J. D., Fulton R. W., Lehenbauer T. W., Step D. L., and Confer A. W. (2010). The epidemiology of bovine respiratory disease: What is the evidence for predisposing factors? Can. Vet. J. 51, 1095.

Tizioto P. C., Kim J., Seabury C. M., Schnabel R. D., Gershwin L. J., Van Eenennaam A. L., et al. (2015). Immunological response to single pathogen challenge with agents of the bovine respiratory disease complex: an RNA-sequence analysis of the bronchial lymph node transcriptome. PloS One 10, e0131459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131459

Tracey K. J. (2009). Reflex control of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 418–428. doi: 10.1038/nri2566

Trimarco J. D., Nelson S. L., Chaparian R. R., Wells A. I., Murray N. B., Azadi P., et al. (2022). Cellular glycan modification by B3GAT1 broadly restricts influenza virus infection. Nat. Commun. 13, 6456. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34111-0

Tsairidou S., Anacleto O., Woolliams J. A., and Doeschl-Wilson A. (2019). Enhancing genetic disease control by selecting for lower host infectivity and susceptibility. Heredity (Edinb) 122, 742–758. doi: 10.1038/s41437-018-0176-9

Wirth A., Duda J., Emmerling R., Götz K.-U., Birkenmaier F., and Distl O. (2024). Analyzing runs of homozygosity reveals patterns of selection in German brown cattle. Genes (Basel) 15, 1051. doi: 10.3390/genes15081051

Yang C., Blaize G., Marrocco R., Rouquié N., Bories C., Gador M., et al. (2022). THEMIS enhances the magnitude of normal and neuroinflammatory type 1 immune responses by promoting TCR-independent signals. Sci. Signal 15, eabl5343. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.abl5343

Zhang S., Wang J., and Cheng G. (2021). Protease cleavage of RNF20 facilitates coronavirus replication via stabilization of SREBP1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2107108118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2107108118

Keywords: copy number variants, runs of homozygosity, ultrasonographic lung lesions, Holstein calves, BRD

Citation: Bernini F, Boccardo A, Delledonne A, Bronzo V, Lanfredi G, Bagnato A and Strillacci MG (2025) Bovine respiratory disease-associated ultrasonographic lung lesions in Holstein calves: a genomic perspective on copy number variants and homozygosity. Front. Anim. Sci. 6:1700819. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2025.1700819

Received: 07 September 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Carrie S. Wilson, Agricultural Research Service (USDA), United StatesReviewed by:

Hosein Salehian Dehkordi, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaMaja Maurić Maljković, University of Zagreb, Croatia

Copyright © 2025 Bernini, Boccardo, Delledonne, Bronzo, Lanfredi, Bagnato and Strillacci. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria G. Strillacci, bWFyaWEuc3RyaWxsYWNjaUB1bmltaS5pdA==

Francesca Bernini

Francesca Bernini Antonio Boccardo

Antonio Boccardo Andrea Delledonne

Andrea Delledonne Valerio Bronzo

Valerio Bronzo Giacomo Lanfredi

Giacomo Lanfredi Alessandro Bagnato

Alessandro Bagnato Maria G. Strillacci

Maria G. Strillacci