- 1Institute of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Sciences, Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hangzhou, China

- 2College of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Southwest Minzu University, Chengdu, China

- 3Ganzi Prefecture Animal Science Research Institute, Kangding, China

- 4Institute of Agro-Product Safety and Nutrition, Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hangzhou, China

Introduction: Reducing feed costs and promoting sustainability are key challenges in yak production. This study aimed to comprehensively evaluate the potential of four locally available agricultural by-products—pumpkin vines (PV), sweet potato vines (SPV), grape vines (GV), and pepper straw (PS)—as alternative feed resources for yaks.

Methods: First, the chemical composition (dry matter-DM, crude protein, neutral detergent fiber-NDF, acid detergent fiber-ADF) of each by-product was analyzed. Subsequently, a 72-hour in vitro ruminal fermentation experiment was conducted to evaluate fermentation parameters. Finally, high-throughput sequencing was used to analyze associated shifts in the rumen bacterial microbiota, and Spearman correlation analysis was performed to link key microbial genera with fermentation outcomes.

Results and Discussion: 1) GV and PV had a higher crude protein content, while PS had the highest levels of dry matter (DM), neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF, P< 0.001); 2) After 72 hours of in vitro fermentation, PV and SPV had superior gas production and nutrient degradability (DM, NDF and ADF, P< 0.001); 3) The fermentation parameters showed that SPV and GV promoted more efficient fermentation, characterized by a lower pH and a lower acetate-to-propionate ratio, but higher microbial protein (MCP) levels (P< 0.001). PV yielded the highest concentrations of volatile fatty acids (P< 0.001). 4) Rumen microbiota analysis identified distinct, diet-specific enrichments of bacterial genera (P< 0.05), including: g_Fusobacterium and g_Basfia in PV; g_Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group and g_Streptococcus in SPV; g_norank_f:p-251-o5 and g_Butyricicoccus in PS; g_Lachnospira and g_Pseudobutyrivibrio in GV Critically, Spearman correlation analysis linked these microbial shifts to fermentation outcomes: Genera such as g_Fusobacterium and g_Basfia were found to be positively correlated with MCP (P< 0.05), while g_Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group and g_Butyricicoccus were positively associated with total volatile fatty acids (P< 0.05). In conclusion, while all four by-products show potential as alternative feeds, SPV and GV show better overall feeding value for yaks, supported by their balanced nutrient composition, improved fermentability, and positive associations with rumen microbiota. This integrated assessment provides a strong basis for utilizing them to enhance the sustainability of yak production.

1 Introduction

As animal husbandry develops rapidly, the efficient use of feed resources has become a key focus for the industry (Chen et al., 2024). As a major agricultural producer, China generates large quantities of crop by-products each year, such as grape vines (GV), sweet potato vines (SPV), pepper straw (PS) and pumpkin vines (PV), etc. which are usually considered agricultural waste and some are incinerated or discarded (Lyu et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022), causing resources waste and potential environmental pollution. However, numerous studies have demonstrated that these crop by-products contain high levels of nutrients such as cellulose, hemicellulose, proteins, and minerals (Melesse et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2020; Song et al., 2022). They can serve as roughage resources for ruminants, playing a significant role in reducing farming costs, improving resource utilization efficiency, and promoting sustainable agricultural development.

The yak (Bos grunniens) is endemic to China’s Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and is primarily distributed across the provinces of Qinghai, Sichuan, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and Yunnan. The yak is highly adaptable to alpine and low-oxygen environments, and it is also an important source of income for local herders (Das et al., 2019). Due to the uneven seasonal supply of pasture on the plateau and the scarce pasture in winter, yaks often suffer from nutritional deficiencies (Liu et al., 2022) that constrain its economic and ecological roles in supporting herder livelihoods and maintaining grassland ecosystems. Utilizing crop by-products as supplementary feed can alleviate winter feed shortages and improve the utilization rate of agricultural waste, thereby promoting the circular development of agriculture and animal husbandry. Nevertheless, few studies have examined the nutrient value and rumen fermentation properties of PV, SPV, PS and GV for yak feeding, which limits the rational utilization of these resources.

The annual production of grapes in China was 13.50 million tons, accounting for 48% of the world’s total grape output. Xinjiang Province yielded 3.48 million tons of grapes in 2023, representing 21.51% of the national total (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023). GV are rich in lignocellulose and various nutrients. Appropriate supplementation helps balance animal feed formulations, improve animal health, and enhance the quality of livestock products (Acquadro et al., 2020). GV also contain multiple bioactive compounds with antioxidant, antibacterial, and gut-morphology-regulating functions (Fernandes et al., 2020). According to the study by Costa-Silva et al. (2022), replacing wheat straw with GV in the diet did not significantly alter the daily weight gain of meat rabbits. China’s sweet potato cultivation area was 2.2×106 km², with a total yield of 4.7×107 tons in 2022, accounting for 29.8% and 54.2% of the global sweet potato cultivation area and total production, respectively (Chen et al., 2024). The sweet potato cultivation area in Sichuan Province has exceeded 9114.7 km2 in 2023. Sweet potato leaves contained relatively high levels of crude protein (CP), metabolizable energy, and micro nutrients, particularly iron and manganese, making it a suitable feed resource in livestock nutrition such as pigs and sheep (Melesse et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022; Tadesse et al., 2025). According to the latest statistics from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 2023), global annual pepper production exceeded 41.88 million tons, with China accounting for 41% of the global total. Major production areas are concentrated in Guizhou, Yunnan, and Sichuan provinces. Li et al. (2024) reported that PS contains abundant CP, neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), water-soluble carbohydrates, and ether extract (EE). Additionally, PS contains various bioactive compounds (e.g., capsaicinoids, flavonoids, and polyphenolic compounds) that can positively enhance animal production performance and immunity (Lu et al., 2020). Research indicates that incorporating 10-15% PS into lamb diets enhances meat quality without adversely affecting rumen fermentation (Li et al., 2025). The cultivation area of pumpkins in China is approximately 350,000 hectares (Chen et al., 2019), with Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang provinces being significant growing regions. Pumpkin by-products encompass pumpkin seeds, pumpkin pulp residue, and PV. Research on the use of pumpkin by-products in animal feed has primarily focused on pumpkin seeds and pulp residue (Li et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024), with limited studies on the utilization of PS. In recent years, PS have garnered increasing attention due to their relatively high CP content (Korićanac et al., 2025; Mijalković et al., 2024; Song et al., 2022).

Apart from the usual nutrients, the feeding value of fibrous by-products is primarily determined by the structure and composition of their plant cell walls, especially the amount of lignin and tannins. Lignin, a complex phenolic polymer, is a key anti-nutritional factor in forages as it forms recalcitrant complexes with cellulose and hemicellulose, physically shielding them from microbial enzymatic attack (Dumitrache et al., 2017). High lignin content is strongly and negatively correlated with digestibility, as it reduces the accessible surface area for rumen microbes, thereby depressing dry matter intake, fermentation rate, and overall energy availability for the host animal (Jung and Allen, 1995). Similarly, condensed tannins, prevalent in many vine crops and fruit residues, can exert dual effects. At moderate levels, they may protect dietary protein from excessive ruminal degradation (Oliveira et al., 2023), but at higher concentrations, they may reduce feed intake and nutrient digestibility, further contributing to potential adverse effects on productive performance (Peng et al., 2025). Given the distinct botanical origins of the four by-products under investigation, we hypothesize that their in vitro fermentation characteristics will be determined by the interplay of their fiber composition (especially lignin content) and the potential presence of tannins. Specifically, 1) Superior in vitro dry matter digestibility (IVDMD) and higher cumulative gas production (GP) will be exhibited by by-products with lower lignin content (anticipated in PV and SPV given their lower ADF). 2) PS, which is expected to have a higher lignified fiber fraction, will demonstrate the lowest fermentability, as reflected by diminished IVDMD, volatile fatty acid (VFA) production and microbial protein (MCP) yield. 3) GV, which may be high in protein, may have limited fermentation efficiency due to the possible presence of tannins. This could lead to different patterns in ammonia-nitrogen and VFA profiles compared to the other by-products.

In vitro rumen fermentation is an important tool for assessing the nutrient value of feeds, which provide a controlled environment that mitigates the ethical concerns, high costs, and intrinsic variability associated with animal studies (Kour et al., 2025). In recent years, this technology has been widely used in the development and evaluation of new feed resources (Scicutella et al., 2025).

Based on the above background, the conventional nutrient value of this four common agricultural by-products was determined by chemical analysis, and their fermentation characteristics were evaluated by in vitro fermentation technology. This study aims to provide a theoretical basis for expanding yak feed resources, as well as technical support for the high-value utilization of agricultural by-products and the sustainable development of agriculture and animal husbandry. We hypothesize that these regionally available agricultural byproducts can be effectively converted into high-quality supplementary feed for yaks. This would simultaneously address waste management and winter feeding challenges in a sustainable manner.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental design and treatments

Four kinds of crop by-products were manually collected as fresh samples from local fields in Meishan City, Sichuan Province, in August 2024 (local altitude: 515 m; temperature: 35 °C). The plants were harvested at a mature stage post-fruit harvest. All samples were dried in an electric constant-temperature drying oven (DHG-9035, Deyang, China) at 65 °C and ground to pass through a 40-mesh screen. For chemical composition analysis and in vitro rumen incubation, five biological replicates were used for each roughage type, with each replicate originating from a different individual plant within the region. Detailed information on the roughage and its sources is provided in Table 1.

2.2 Chemical composition analysis

The contents of DM, CP, crude ash (Ash), and EE were measured following the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC, 2005): DM was determined via the drying method, CP content was assessed using an automatic Kjeldahl nitrogen tester (K9860, Zhengzhou Jinshimai Technology Co., LTD, Zhengzhou, China), and Ash content was measured at 550°C for six hours with a muffle furnace (SX2-2.5-10, Shanghai Jiecheng Laboratory Instrument Co., LTD, Shanghai, China). The EE content was determined using a Soxhlet extractor (HT6+SOX416, Gerhardt Analytical Systems, Bonn, Germany). NDF and ADF were determined using a fiber analyzer (FT 12, Gerhardt Analytical Systems, Bonn, Germany) according to the method of Van Soest (Van Soest et al., 1991). The analysis included the use of heat-stable α-amylase and sodium sulfite during the NDF procedure to remove interfere with starch and protein, respectively.

2.3 Estimated energy value for feed formulation

Total digestible nutrients (TDN) were calculated using the method of Lithourgidis et al. (2006). The formula provided by NRC (2000) was used to calculate digestible energy (DE), metabolic energy (ME), net energy for maintenance (NEm) and net energy for gain (NEg).

.

2.4 In vitro fermentation trial

Four groups were established with PV, SPV, GV, and PS as fermentation substrates. Exactly 2.0 g (± 1 mg) of air-dry substrate was weighed into each syringe using an analytical balance (ATY224, Shimadzu Management (China) Co., LTD, Shanghai, China). Each group was incubated in the rumen in five replicates. According to Menke et al. (1979) , the buffer was prepared as follows: 400 mL of water was mixed with 0.1 mL of solution A (containing 13.2 g CaCl2·2H2O, 10.0 g MnCl2·4H2O, 1.0 g CoCl2·6H2O, and 8.0 g FeCl3·6H2O per 100 mL of water), 200 mL of solution B (39.0 g NaHCO3 in 1000 mL of water), 200 mL of solution C (5.7 g Na2HPO4, 6.2 g KH2PO4, and 0.6 g MgSO4·7H2O per 1000 mL of water), 1 mL of resazurin (0.1% w/v), and 40 mL of a reduction solution (comprising 95 mL of water, 4 mL of 1 M NaOH, and 625 mg of Na2S·9H2O). The syringes were placed in a constant temperature shaker at 39 °C for preheating. Ruminal fluid was collected from six 4-year-old, rumen-fistulated Maiwa yaks. All animals were cared for in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Ganzi Prefecture Animal Science Research Institute (Sichuan, China; approval number: P20240810-2). The donor yaks were maintained on a basal diet of mixed roughage and concentrate, which was provided twice daily at 08:00 and 17:00, with ad libitum access to water. A representative sample of the active fermentation phase was to be ensured, so rumen contents were to be collected via the fistula two hours after the morning feeding. Contents from all yaks were combined in equal volumes, homogenized, and filtered through four layers of gauze. The filtrate was immediately transferred to a pre-warmed thermos flask, which was continuously purged with CO2 to preserve strict anaerobiosis. The filtrate was then quickly transported back to the laboratory and thoroughly mixed with the buffer at a volume ratio of 1:2 to prepare the in vitro culture medium. The medium was placed in a 39 °C thermostatic water bath and continuously sparged with carbon dioxide. 100 mL of the medium was injected into each syringe containing the substrate; after thorough shaking to remove residual gas, the syringes were sealed (coated with petroleum jelly) and placed in a 39 °C constant-temperature shaker (55 r/min). The position of the piston was read per four hours. If gas production exceeded 50 mL the clip was opened and the piston moved back to the 100 mL position. All readings were taken quickly to avoid a change in temperature. Cumulative GP was recorded at 8, 16, 24, 36, 48, and 72 hours sequentially. Two blank samples (100 mL of mixture only) were set up for GP correction. After 72 hours of incubation, the syringes were immediately placed in an ice bath to terminate the incubation. The culture fluid was filtered through a nylon cloth, and the pH of the filtrate was measured immediately using a portable pH meter (AZOVTES AE8601, Dongguan Frank Technology Co., Ltd.). Part of the filtrate was aliquoted into six 10 mL centrifuge tubes and stored in a -80 °C ultra-low-temperature refrigerator for fourteen days for subsequent determination of NH3-N, MCP, VFA and rumen microbiota diversity. The residue in the syringe was flushed onto a nylon cloth with distilled water and dried in a 105 °C oven to determine of IVDMD, in vitro neutral detergent fiber disappearance rate (IVNDFD) and in vitro acid detergent fiber disappearance rate (IVADFD).

VFA in the culture fluid were analyzed by gas–liquid chromatography (Agilent 7890B, Palo Alto, CA, USA) according to the procedure described by Mao et al. (2008). The total volatile fatty acid (TVFA) were the sum of acetate, propionate, valerate and butyrate. The NH3-N concentration was measured according to the method of Chaney and Marbach (1962). The MCP concentration was determined by direct measurement according to the method of Lv et al. (2023). Techniques by Tilley and Terry were used to assess IVDMD after 72 hours of incubation (Tilley and Terry, 1963). The percentages of IVDMD, IVNDFD and IVADFD were calculated using the following equations:

2.5 Rumen microbiota diversity analysis

Total microbial genomic DNA was extracted from 20 samples using the FastDNA® Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and concentration of DNA were determined by 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, United States). The hypervariable region V3-V4 of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with primer pairs 338F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) (Liu et al., 2016) by T100 Thermal Cycler PCR thermocycler (BIO-RAD, USA). The PCR reaction mixture included 4 μL 5×Fast Pfu buffer, 2 μL 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 μL each primer (5 μM), 0.4 μL Fast Pfu polymerase, 0.2 μL BSA, 10 ng of template DNA, and ddH2O to a final volume of 20 µL. PCR amplification cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 27 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 45 s, and single extension at 72 °C for 10 min, and ending at 4 °C. The PCR products were extracted from 2% agarose gel and purified using the PCR Clean-Up Kit (YuHua, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified using Qubit 4.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts and paired-end sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA) by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China) according to the standard protocols. Raw sequencing reads were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (Accession Number: SRP610274).

After demultiplexing, sequences were quality-filtered with fastp (0.19.6) (Chen et al., 2018) and merged with FLASH (v1.2.11) (Magoč and Salzberg, 2011). High-quality sequences were denoised using DADA2 (Callahan et al., 2016) plugin in the QIIME 2 (Bolyen et al., 2019) (version 2024) pipeline with recommended parameters to obtain amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) (single-nucleotide resolution based on sample error profiles). To minimize the impact of sequencing depth on Alpha and Beta diversity, the number of sequences per sample was rarefied to 50,201, which still yielded an average Good’s coverage of 99.80%. Taxonomic annotation of ASVs was performed using the Naive Bayes consensus taxonomic classifier implemented in QIIME 2 (V2022.2) and the SILVA 16S rRNA database (v138.2). To compare Alpha diversity indices between the four groups, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was applied. The indices included Sobs, ACE, Chao, Shannon, and Simpson. Assessment of Beta diversity was done using principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA), which analyzed community structure similarities among different samples based on the Bray-Curtis distance metric. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) combined with effect size (LEfSe) method was used to identify bacterial taxa that showed differential representation across various groups and taxonomic levels. A threshold of LDA effect size greater than 2 was applied. Spearman rank correlation were applied to analyze the correlation heatmap between fermentation parameters and the selected species.

2.6 Statistical analysis

The number of replicates per treatment was decided based on what is normally done in in vitro rumen fermentation studies. These studies have shown that five replicates are enough to spot big changes in major fermentation parameters (Xiao et al., 2025; Bai et al., 2025). Initial data were managed using Microsoft Excel 2019. Rumen fermentation parameters among groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA in SPSS 26.0 software. Data were analyzed according to the following model:

where Yij is the observed value, μ is the overall mean, Ti is the fixed effect of treatment (PV, SPV, GV, PS), and eij is the random residual error. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Duncan’s multiple range test was used to compare statistical differences between the treatments, with P ≤ 0.05 indicating significance, and 0.05< P ≤ 0.10 considereda trend.

Alpha diversity indices were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test using the stats package in R (v3.3.1). PCoA based on Bray-Curtis distance was used to determine the similarity among the microbial communities using the vegan package in R (v3.3.1). A Spearman’s correlation coefficient analysis was completed using the Mantel test. A probability value of P< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Chemical composition of the four agricultural by-products

The chemical composition of the four agricultural by-products was shown in Table 2. The DM content of the four by-products ranged from 93.52% to 95.11%, with PS having the highest content (P< 0.001). PV had the highest ash content of 23.25% (P< 0.001), while the highest EE content of 2.91% was found in SPV (P< 0.001). The CP contents of PS, SPV, PV, and GV were 5.39%, 7.49%, 15.25% and 16.19%, respectively. The NDF content of PS (49.38%) was significantly higher than that of SPV, GV and PV (P< 0.001), and PS also had the highest ADF (39.04%) content (P< 0.001).

3.2 Estimated energy value for feed formulation

The results are presented in Table 3. PV showed the highest estimated values across all parameters, consistent with its superior IVDMD and GP metrics. SPV and GV followed, while the PS group exhibited the lowest values (P< 0.001).

3.3 Gas production and nutrient disappearance rate in vitro from four agricultural by-products

The IVDMD, IVNDFD, IVADFD and GP of the four agricultural by-products are shown in Table 4. The IVDMD of roughage feeds ranged from 51.09% to 86.37%, with PV exhibiting the highest value and PS the lowest (P< 0.001). The IVNDFD and IVADFD were also found to be higher in PV (80.24%; 76.27%) than in GV (43.56%; 41.18%) and PS (19.24%; 17.52%, P< 0.001). The GP increased with longer incubation times. After 72 h of incubation, GP ranged from 71.60 to 194.20 mL per 2.00 g of substrate. At all incubation periods, the cumulative GP from PV was significantly higher than that of SPV, PS and GV (P< 0.001). Furthermore, PS had the lowest cumulative GP from 24 h to 72 h (P< 0.001).

3.4 Rumen fermentation parameters of the four by-products

Table 5 shows the data on the in vitro fermentation parameters of the different by-products. Significant differences in nitrogen utilization were observed among the by-products. The NH3-N concentration was highest in the fermentation of PV, followed by SPV and PS; GV yielded the lowest level (P< 0.001). Conversely, MCP synthesis showed a distinct pattern. GV and SPV supported the greatest MCP production, which was significantly higher than that from PV and PS (P< 0.001). This suggests that, despite releasing less NH3-N, GV facilitated the most efficient incorporation of nitrogen into MCP. TVFA production was highest for PV and lowest for PS (P< 0.001). The proportions of individual VFAs revealed distinct fermentation patterns. PV fermentation produced the highest levels of acetate and propionate, resulting in an intermediate A:P ratio of 2.40. PS fermentation was characterized by low propionate and butyrate levels, leading to the highest A:P ratio among all by-products. SPV promoted a more balanced fermentation, producing the lowest A:P ratio, while GV produced a notably high proportion of valerate (P< 0.001). The final fermentation pH differed significantly between substrates. PV and PS resulted in a higher pH than SPV and GV (P< 0.001).

3.5 Rumen microbiota diversity

3.5.1 Sampling depth

Analysis of the rumen microbiota diversity of 20 samples yielded in 1,629,692 optimized sequences, totaling 685,479,822 bases (bp). The average length of the quality sequences was 420 bp. These sequences were effectively clustered and analyzed into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) defined by 97% similarity, yielding a total of 8,407 ASVs. These belonged to 21 phyla, 37 classes, 82 orders, 161 families, 387 genera and 786 species. To minimize statistical bias, the number of sequences per sample was rarefied to 50,201. Additionally, the ASV Good’s coverage index value for all samples was over 99%, and the rarefaction curves increased slowly and approached saturation (Figure 1), indicating that the constructed library effectively reflects the abundance and diversity of the microbial communities in the samples.

Figure 1. (a) Increasing sequencing depth did not result in a sustained increase in observed species diversity (Sobs index richness). When sequencing reached approximately 50,000 sequences, the Sobs curve entered a distinct plateau phase and leveled off. (b) At the ASV level, the Good’s Coverage index for all samples exceeded 0.99, indicating that the sequencing depth in this study has covered the vast majority of microbial sequences within each sample.

3.5.2 Rumen microbiota diversity indices

Ace, Chao, Shannon, and Simpson indices were obtained by analysis of the Alpha diversity index, as shown in Table 6. The results showed that the Ace, Chao, Shannon, and Simpson indices of the four by-products were different (P< 0.001). PV had the highest ACE, Chao, Shannon and Sobs indices (P< 0.001), while their Simpson index was lower than that of PS and GV (P< 0.001). Furthermore, the GV had higher ACE, Chao and Sobs than SPV and PS (P< 0.001) and there were no significant differences in Ace, Chao, Shannon, Simpson and Sobs indices between SPV and PS (P > 0.05).

Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of the rumen microbiota based on Bray-Curtis distance matrices between each sample is shown in Figure 2A. The contribution values of principal components PC1 and PC2 accounted for 41.58% and 20.80% of the total variation, respectively. Rumen microbiota structure had aggregation distribution within each group, indicating significant differences in rumen microbial Beta diversity among groups (P< 0.05). The Venn diagram is shown in Figure 2B, and the total number of ASVs was 8407. In the PV group (T1), the number of ASVs was 4849, with 2789 unique ASVs. In the SPV group (T2), the number of ASVs was 3179, with 1431 unique ASVs. In the PS group (T3), the number of ASVs was 3326, with 1235 unique ASVs. In the GV group (T4), the number of ASVs was 3856, with 1868 unique ASVs. A total of 204 ASVs (2.43% of the total) were shared among the four groups.

Figure 2. (a) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity reveals that samples within the same group cluster relatively closely, indicating similar species composition within groups. Samples from different groups show a clear separation trend, indicating significant differences in species composition between groups. The two principal coordinate axes (PC1 and PC2) together explain 61.58% of the total variation in the communities. (b) A total of 8,407 ASVs were identified across all samples. 204 ASVs were shared across all groups, accounting for approximately 2.43% of the total. The number of ASVs unique to each group was as follows: Group T1: 2,789; Group T2: 1,431; Group T3: 1,235; Group T4: 1,868.

3.5.3 Taxonomic classification levels of the bacterial communities

In this experiment, a total of 21 microbial phyla were identified, the relative abundance of the top ten phyla are shown in Table 7 and Figure 3A. The predominant phyla (>99% of total) were Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteriota, Desulfobacterota, Actinobacteriota, Spirochaetota, Fibrobacterota, Patescibacteria and unclassified_k:norank_d:Bacteria. Compared with the SPV group, the Actinobacteriota was significantly lower in PV, PS and GV groups (P< 0.05). Desulfobacterota was higher in SPV and PS groups than in PV and GV groups (P< 0.05). The highest abundances of Fibrobacterota and Spirochaetota were observed in GV group; however, the Proteobacteria abundance in GV group was lower than in the other groups (P< 0.05). Firmicutes abundance was higher in SPV and GV groups than in PV and PS groups (P< 0.05), while Fusobacteria was lower in SPV and GV group than in PV and PS group (P< 0.05). The highest Patescibacteria was observed in PS group (P< 0.05). Notably, Bacteroidota and Firmicutes collectively accounted for 65% of rumen microbial diversity in yaks. At the genus level, 387 microbial genera were identified, and the relative abundances of the top ten genera in terms of ruminal microbial genus-level abundance were shown. These included Bacteroides, Prevotella, Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group, norank_f:p-251-o5, Streptococcus, Lachnospira, Oribacterium, Fusobacterium, Escherichia-Shigella and Basfia. As shown in Table 8 and Figure 3B, except for Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut group, the abundance of the remaining nine genera in the four groups was significantly different (P< 0.05).

Figure 3. (a) Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria were the three most dominant phyla across all groups, accounting for 41.68%, 34.78%, and 14.25% of total sequence abundance on average. (b) The most abundant genera within each group were: Streptococcus, Fusobacterium, and Bacteroides for T1; norank_f:p-251-o5, Streptococcus, and Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group for T2; norank_f:p-251-o5, Streptococcus, and Fusobacterium for T3; norank_f:p-251-o5, Streptococcus, and Lachnospira for T4.

A LEfSe analysis was performed to determine the functional communities in the samples and identify the specific microbiota in the rumen fluid of the four treatment groups of yaks (Figure 4). Microbiota with a linear discriminant analysis (LDA) > 2 were considered specific microbiota. The results showed that the g_Fusobacterium, g_Basfia, g_Anaeroplasma, g_Bacteroides and g_Veillonella were significantly enriched in the PV group (P< 0.05); the g_Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut group, g_Streptococcus, g_Oribacterium, g_Schwartzia and g_Megasphaera were significantly enriched in the SPV group (P< 0.05); the g_norank_f:p-251-o5, g_Butyricicoccus, g_Enterococcus, g_Succinivibrio and g_Desulfovibrio were significantly enriched in the PS group (P< 0.05); and the g_Lachnospira, g_Pseudobutyrivibrio, g_Butyrivibrio, g_Prevotellaceae_Ga6A1_group and g_Prevotellaceae_UCG-003 were significantly enriched in the GV group (P< 0.05).

Figure 4. LEfSe analysis systematically identifies key microbial biomarkers associated with different groups (LDA>2). Results show the top 5 LDA values for each group are: g:Fusobacterium and g:Basfia for T1; g:Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group and g:Streptococcus for T2; g:norank_f:p-251-o5 and g:Butyricicoccus for T3; g:Lachnospira and g:Pseudobutyrivibrio for T4.

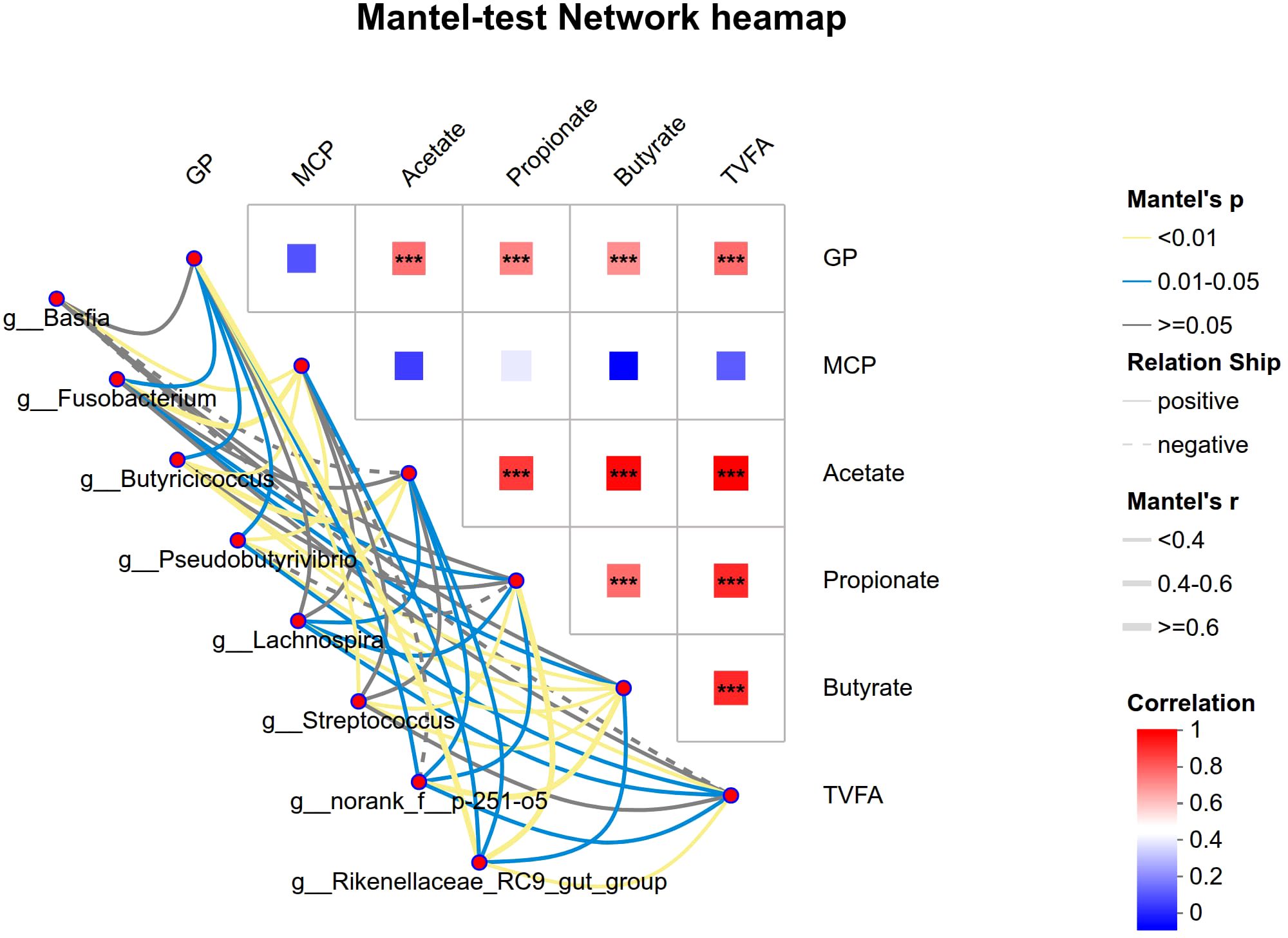

3.5.4 Spearman correlation analysis

The relationship between changes in the rumen microbial community (identified by LEfSe, top 2) and variations in fermentation parameters of four different crop by-products was analyzed using mantel test. The results are shown in Table 9 and Figure 5. The results showed that there were significant and organized links, suggesting that the changed bacteria were closely connected to the host’s fermentation metabolic phenotype. Several genera exhibited broad and strong positive correlations with core indicators of fermentation activity. Notably, g_Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group showed the strongest positive correlations with GP (Mantel r = 0.476, P = 0.001) and propionate (Mantel r = 0.563, P = 0.001), as well as being positively associated with acetate, butyrate and total volatile fatty acids (TVFA) (Mantel r = 0.353, P = 0.003). In the same way, g_Streptococcus was strongly linked to GP (Mantel *r* = 0.348, P = 0.001), propionate (Mantel *r* = 0.246, P = 0.007), and butyrate (Mantel *r* = 0.259, P = 0.007). Furthermore, g_norank_f_p-251-o-5 and g_Butyricicoccus were positively associated with multiple VFAs, including butyrate (Mantel r = 0.430 and 0.283, respectively; P ≤ 0.001). This cluster likely represents a core functional microbiome that drives energy harvest (GP) and the production of key metabolic end-products (VFAs). g_Fusobacterium, g_Basfia, and g_Butyricicoccus were positively correlated with MCP (r = 0.466, 0.312, and 0.268, respectively; P< 0.05). g_Pseudobutyrivibrio and g_Lachnospira displayed a broader association spectrum. Both were positively correlated with acetate, butyrate and total VFA (TVFA). While a positive correlation was identified between g_Lachnospira and propionate (Mantel *r* = 0.134, P = 0.042), a positive link was found between g_Pseudobutyrivibrio and MCP (Mantel *r* = 0.254, P = 0.008), suggesting a potential additional role in supporting protein synthesis.

Figure 5. Mantel test heatmap: Lines represent correlations between differential bacteria and fermentation parameters; the heatmap depicts correlations among fermentation parameters. Line thickness indicates correlation strength between differential bacteria and fermentation parameters, plotted using Mantel’s r (the absolute value of R). Relationship: Positive and Negative denote positive and negative correlations between differential bacteria and fermentation parameters respectively; Different colors in the heatmap represent positive and negative correlations, with color intensity indicating correlation strength. Asterisks within color blocks denote significance: *0.01< P ≤ 0.05, **0.001< P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

The correlation matrix among the fermentation parameters themselves (Table 10) further underscored the coordinated nature of the fermentation process. GP was strongly and positively correlated with all major VFAs—acetate, propionate, butyrate and TVFA (*r* ranging from 0.691 to 0.757, P ≤ 0.001). Moreover, TVFA showed an extremely strong intrinsic correlation with its individual components (e.g. acetate, propionate and butyrate, *r* > 0.8, P< 0.05), confirming that these metabolic products are highly co-variant during fermentation.

4 Discussion

4.1 The chemical composition of the four by-products

This study conducted a systematic analysis of the conventional nutritional components of four agricultural by-products, revealing significant differences specific to each raw material. In terms of nutritional composition, PV and GV exhibited remarkable CP content—substantially higher than that of traditional roughages such as corn stalks (approximately 6-8%). A recent study on pumpkin leaves in the food field has found that a protein component rich in RuBisCo can be isolated from green pumpkin leaves, which are regarded as a high-value protein extracts with notable food functional properties (Mijalković et al., 2024). Although such proteins have not been fully explored in the feed industry, their abundance, availability, renewability, sustainable production, cost-effectiveness, and good functional properties make them potentially valuable for feed applications (Perović et al., 2024). Notably, the CP content in GV approaches that of some high-quality leguminous forages like alfalfa and onobrychis viciifolia (Jiang et al., 2025; Bhattarai et al., 2018), indicating their potential as a new protein feed source. However, the practical utilization of GV as a feedstuff may be affected by certain anti-nutritional factors. As is the case with a considerable number of lignocellulosic by-products, GV has the capacity to contain elevated levels of lignin and condensed tannins (El Achkar et al., 2018). A high lignin content inherently restricts fiber digestibility, as demonstrated by the comparatively lower IVNDFD of GV in comparison to PV in our investigation. Therefore, future research should quantify the levels of lignin and tannins in GV from different sources, and evaluate processing methods such as physical disruption, chemical treatment or ensiling with tannin-binding agents, to mitigate these limitations and realize the full protein value of GV.

Forages with ash content exceeding 20% are often indicative of soil or dust contamination during harvesting, handling or drying processes (Wilman and Altimimi, 1984). Such contamination is a common issue with crops that come into contact with the ground, such as PV. If the high ash is indeed largely due to soil, it would artificially inflate the DM weight while diluting the concentration of nutritionally valuable organic components. Consequently, the true nutritive value of the organic portion of the biomass may be higher than our analyses suggest on an as-sampled basis. Furthermore, soil ingestion can pose risks to animal health, including the excessive intake of undesirable minerals and potential exposure to pathogens or toxins. Therefore, in practical applications, it is crucial to implement improved harvesting techniques (e.g. cutting above ground level) and cleaning procedures to minimize contamination. It is vital that future studies explicitly account for or determine the ash composition so that a distinction can be made between nutritive minerals and contaminant inert material. SPV are mainly composed of stems and leaves. Previous studies have indicated that the CP content in SPV ranges from 10% to 14% (Ishida et al., 2000), and they are also rich in water-soluble carbohydrates (Ali et al., 2019). Baba et al. (2017) assessed the nutritional components across twelve varieties of SPV and found that their CP content varied between 10.82% and 20.58%, while NDF content ranged from 21.14% to 35.37%. In this study, the NDF content of SPV was found to be 39.95%, which is at the higher end of previously reported ranges, but still consistent. However, the CP content was only 7.49%. This deviation from the typical range can be reasonably attributed to several agronomic and post-harvest factors: 1) CP is concentrated in the leaves, while stems are more fibrous and lower in protein. A lower proportion of leaves in the harvested material, which is common in bulk or late-harvested vines, would significantly decrease the overall CP content (Liebhardt et al., 2022). 2) Harvesting at a later growth stage leads to translocation of nitrogen from the vines to the roots and increased lignification of stems, both of which reduce vine CP content (Ma et al., 2023). 3) Wilting, drying, or prolonged field exposure before sampling can cause substantial loss of highly digestible leaf protein through respiration and leaf shatter, while the more resistant fibrous components (NDF, ADF) remain, further diluting the CP percentage on a DM basis. Therefore, the observed low CP value likely reflects a combination of these practical factors (Temoche Socola et al., 2025). Despite having a moderate protein content, the EE content reached 2.91%, indicating that SPV possess high-energy characteristics and potential special value when utilized as ruminant feed.

The nutritional characteristics of PS in this study exhibited typical features associated with low-quality roughage; they demonstrated high fiber levels (NDF 49.38%, ADF 39.04%) coupled with low CP content (5.39%). These attributes likely contributed to the low GP and low MCP observed during in vitro rumen fermentation. The high NDF and ADF contents indicate a dense lignocellulosic structure, which is resistant to microbial degradation and results in slower and less extensive fermentation, thereby reducing cumulative GP (García-Rodríguez et al., 2019). Furthermore, the low CP content may have limited the availability of nitrogen and other essential nutrients for rumen microbes, impairing their growth and metabolic activity, which in turn restricted MCP synthesis (Hristov et al., 2019). This is consistent with the low IVDMD, IVNDFD and IVADFD observed for PS, collectively underscoring its poor fermentability and nutritive value for ruminants. In summary, the nutrient value of the four by-products varies greatly. When using them as roughage for ruminants, it is important to consider the appropriate amount to add based on the nutrient content of each by-product.

4.2 Ruminal DM degradation and gas production analysis

The results of in vitro fermentation tests elucidated the dynamic degradation characteristics of four by-products within the rumen of yaks. The composition of NDF and ADF in roughage significantly influences its rumen IVDMD, with a higher content being negatively correlated with IVDMD (Du et al., 2016). This study identified notable differences in the IVDMD among the four by-products. PV demonstrated outstanding fermentation performance, achieving an IVDMD of up to 86.37% within 72 hours, which was significantly higher than that of other by-products. Conventional nutritional analysis also showed that PV has considerably lower levels of NDF and ADF than other by-products, which may explain its elevated DMD. This favorable fiber profile strongly suggests a higher content of highly digestible cell contents, such as non-structural carbohydrates, which include water-soluble carbohydrates, such as sugars, and starch (Perović et al., 2025). These are rapidly and almost completely fermented by rumen microbes, contributing to the early and high GP observed. These rapid fermentation characteristics make PV a suitable energy supplement for high-yield yaks. However, it is important to note that excessive feeding could result in acidosis. In contrast, the fermentation characteristics of PS were entirely different. Its IVDMD over 72 hours was only 51.09%, consistent with its nutritional profile characterized by high fiber and low CP content. It is worth noting that the DMD of these four by-products are comparable to or even exceed those of traditional legume forages such as alfalfa. This suggests that in practical production, these by-products could be considered as suitable substitutes for alfalfa to conserve alfalfa forage resources (Chang et al., 2022).

In vitro GP serves as a vital indicator for assessing feed digestibility, it primarily arises from the microbial breakdown of organic matter present in feed within ruminants’ rumens and is positively correlated with digestibility (Lei et al., 2018). In this study, significant differences were observed regarding both 72 hours GP and DMD across the four by-products; moreover, these two values demonstrated a positive correlation aligned with theoretical expectations. The marked differences in GP and IVDMD among by-products are not just a result of the substrate composition, but also due to distinct changes in the rumen microbial community structure. As revealed by our microbial diversity analysis (Table 8 and Figure 2), fermentation of PS, with its recalcitrant fiber matrix, likely favored a microbial consortium that was less efficient at degrading the overall substrate. The low IVDMD and GP of PS may therefore be associated with a lower relative abundance of key fibrolytic bacteria capable of degrading cellulose, such as Bacteroides, Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group and Streptococcus, or with a community dominated by slow-growing, oligotrophic taxa adapted to low-quality forages. On the other hand, the higher fermentation of PV probably encouraged a community that was more active and varied, with lots of primary degraders of soluble carbohydrates and hemicellulose, resulting in faster and more extensive gas production. Consequently, the discrepancies in GP can be directly correlated with the functional capacity of the substrate-driven microbial ecosystem. Furthermore, as time progressed, the cumulative GP of the four by-products continued to rise, indicating that these by-products were consistently utilized by the rumen microbiota in yaks. However, over time, the degradation rate exhibited a pattern of initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease. This phenomenon may be attributed to a reduction in substrate availability during the later stages, which could lead to a gradual decline in GP rate (Chen et al., 2024). Additionally, as fermentation products such as MCP, VFA, and NH3-N are generated, alterations occur in the composition of the culture medium. These changes may hinder microbiota growth and consequently diminish their capacity to digest and utilize roughage (McDonald and Edwards, 1976).

Effective utilization of these seasonal by-products in yak feeding systems requires consideration of post-harvest management. PV and SPV have high moisture content. They require immediate processing, such as ensiling. This is to prevent spoilage and preserve nutrients. Their high water-soluble carbohydrate content makes them ideal for ensiling. GV and PS are drier and more suitable for drying and baling. In order to enhance the utilization of high-fiber by-products such as PS and GV, physical or chemical processing could be explored to improve digestibility (Zhao et al., 2018). In terms of seasonal integration, these by-products can play complementary roles: high-energy vines (PS and SPV) can serve as a primary energy source during the fattening period in autumn, while GV, which has better quality protein, can be used as a protein supplement during winter and spring when forage quality is poor. PS may primarily function as bulk roughage to maintain rumen fill in maintenance diets.

4.3 In vitro fermentation fluid parameters

Ruminant livestock have an organ composed of a large number of microbiota, the rumen, which is a natural anaerobic space, providing the necessary environment for the rumen microbiota to reproduce and develop. The rumen microbiota synthesize VFA, NH3-N and MCP during the fermentation process, which are important indicators of the physiological health of the rumen and its ability to transform nutrients. Rumen fluid pH is an important indicator for evaluating the rumen fermentation status and is influenced by multiple factors, such as dietary structure, salivary secretion volume, rumen VFA content, and rumen absorption rate, etc (Gunun et al., 2013). If the pH deviates significantly from the optimal range, it can adversely affect the activity of rumen microbiota, resulting in fermentation abnormalities. In this study, the pH range of the four roughage types was 6.72 to 6.97, slightly higher than the optimal pH range (5.5–6.4) for rumen bacteria (Calsamiglia et al., 2002). This may be influenced by the physiological condition of the donor cattle or the composition of the substrate.

NH3-N is produced by breaking down nitrogen-containing compounds in feed. This process reflects the degradation of dietary protein and its subsequent utilization by microbiota for synthesizing bacterial proteins. Therefore, NH3-N is a crucial marker for rumen metabolism. An optimal NH3-N level can support the proliferation of microbiota and the synthesis of bacterial proteins. The optimal NH3-N concentration for rumen microbiota growth ranges from 6.3 to 27.5 mg/dL (Murphy and Kennelly, 1987). In this experiment, the NH3-N concentrations of the four types of roughage were 7.68–18.18 mg/dL, which fell within the normal concentration range. Nevertheless, the absolute concentration at a solitary time point furnishes a paucity of insight; the kinetics of NH3-N production and uptake are more pivotal for microbial efficiency. These kinetics are heavily influenced by the nature of the dietary nitrogen source. Nutritional sources abundant in soluble protein fractions or non-protein nitrogen compounds are swiftly degraded to NH3-N, resulting in a precipitous rise in NH3-N concentration. In the absence of adequate fermentable energy to accompany this rapid release, the excess NH3-N may be absorbed and subsequently excreted as urea, rather than being incorporated into MCP (Hristov et al., 2019). This may explain the contrasting patterns observed in our study. PV, which had the highest NH3-N concentration (18.18 mg/dL) but the lowest MCP yield, likely contains a proportion of nitrogen that degrades rapidly. The high IVDMD confirms ample energy availability; however, the low MCP yield suggests a potential mismatch between the rate at which NH3-N is released and the rate at which it is captured by microbes. In contrast, GV, with the lowest NH3-N (7.68 mg/dL) but the highest MCP, may have a nitrogen source that is less soluble or more slowly degraded, providing a steadier, more synchronized supply of NH3-N that rumen bacteria can efficiently utilize in conjunction with available energy. SPV, with intermediate NH3-N and high MCP, appear to strike a more favorable balance. Therefore, while all NH3-N levels were adequate, the efficiency of converting feed nitrogen into MCP varied substantially, likely due to differences in the solubility and degradation rate of the nitrogenous compounds present in each by-product.

Animals primarily utilize the nutrients in their diet in the form of VFAs and MCP following fermentation in the rumen. VFAs serve as the main energy source for ruminants, while MCP is their primary protein source (Kansagara et al., 2022). Acetate is the main precursor for the synthesis of milk fat, and propionate is the precursor for the synthesis of glucose, which can supply most of the energy required by the organism. Butyrate, as one of the main products of rumen fermentation, can be preferentially absorbed by the rumen epithelium, thereby promoting the proliferation and differentiation of rumen epithelial cells and enhancing the rumen’s ability to absorb nutrients (Lee et al., 2015). Studies have shown that roughage contains a large amount of fiber-like substances, which can be fermented in the rumen to produce more acetate (Iwamoto and Asanuma, 2001). In this experiment, all four types of roughage had the highest content of acetate after 72 hours of fermentation, which is related to the fiber content of roughage, and their fermentation in the rumen would produce a relatively high proportion of acetate and a lower proportion of propionate. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the TVFA content produced during the fermentation process of all four by-products was higher than that of conventional alfalfa forage (Bai et al., 2025). In addition, the MCP content in the GV group was the highest, while the NH3-N content was the lowest. This indicates that rumen microbiota in yaks utilize nitrogen-containing substances in GV more efficiently than those in the other three by-products. Although the PV group produced more VFA, its MCP content was lower. This suggests that, when considered as a substitute for yak protein roughage, GV are more suitable than PV.

4.4 Rumen microbiota diversity

The rumen’s ecosystem and its digestive processes are in a state of equilibrium, which relies on the variety of microbiota that inhabit it. These microbiota can be affected by a range of factors, including diet, age of the animal, environmental conditions, and feed additives (Belanche et al., 2012; O’Hara et al., 2020). Two pivotal metrics for assessing the diversity of microbial communities are Alpha diversity and Beta diversity. The relative abundance of each species within a community is quantified by Alpha diversity, also known as core diversity. This reflects the richness and evenness of different microbial taxa. Beta diversity examines the compositional differences between communities. It highlights shifts in population structure. It also reveals the stability and functional dynamics of microbial communities within ecosystems (Jami et al., 2014). As found by Gu et al. (2024), the type of roughage fed to yaks can change the rumen microbiota. The dominant rumen microbiota are Firmicutes and Bacteroidota (Singh et al., 2012; de Oliveira et al., 2013), which play an important role in rumen fermentation. Bacteroidota contributes to the synthesis of propionate in the rumen and the degradation of proteins and carbohydrates (Luo et al., 2017; Macfarlane and Macfarlane, 2003), while Firmicutes plays a significant role in energy utilization (Wu et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2015). The dominant phyla in yaks’rumen flora were consistent with results from previous studies (Zhu et al., 2025). In this experiment, the proportions of Firmicutes and Bacteroidota in the PV, SPV, PS and GV groups were 36.73% and 31.27%, 45.53% and 33.92%, 31.74% and 37.34%, and 52.88% and 36.44%, respectively. The proportions of Firmicutes and Bacteroidota were high in all four groups. The relative abundance of Firmicutes was significantly higher in the SPV and GV groups than in the PV and PS groups. This indicates that feeding SPV and GV could promote the proliferation of Firmicutes, thus improving the utilization efficiency of nutrients.

The results of Spearman correlation analysis showed that the abundances of g:Basfia, g:Fusobacterium, g:Butyricicoccus and g:Pseudobutyrivibrio were significantly positively correlated with the content of rumen MCP in yaks. g:Basfia and g:Fusobacterium were the dominant bacterium in the PV group, while the CP content in the PV group was 15.25%, significantly higher than that in the SPV and PS groups (7.49% and 5.39%). However, the content of MCP in this group was significantly lower than that in the SPV group. This suggests that g:Basfia and g:Fusobacterium may be associated with the rumen protein degradation process in ruminants. Khiaosa-Ard et al. (2023) reported that when 3.7% commercial grape seed extract was added to the diet, the abundance of g_Pseudobutyrivibrio increased. In this study, g_Pseudobutyrivibrio was significantly enriched in the GV group, which was similar to the above research results. It indicates that certain substances in the grape by-products may be conducive to the colonization and growth of the g_Pseudobutyrivibrio. Chen et al (2025) reported that the TVFA content in the rumen was found to be considerably higher than that found in the abomasum, jejunum and colon. Furthermore, the Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut group in the rumen was also significantly higher than in the abomasum, jejunum and colon of yaks. Therefore, we speculate that the Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut group is closely related to the synthesis of VFAs in the rumen of yaks. In this study, the Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut group was significantly and positively correlated with TVFA content in yaks, which is consistent with previous research results. Zhao et al. (2024) reported that g_Streptococcus was correlated significantly positively with both primary bile acid biosynthesis and arachidonic acid metabolism. It has been established that arachidonic acid regulates milk lipid synthesis and secretion (Dozsa et al., 2014). The g_Streptococcus was significantly enriched in the SPV group, and was significantly and positively correlated with the content of propionate and butyrate in yaks in this study. It indicates that using SPV as the diet of yaks is beneficial for the synthesis of rumen VFA. However, while the sample size (n=5) employed in this study is consistent with standard practices for in vitro rumen experiments and proved adequate for detecting significant differences in most fermentation parameters, it is important to acknowledge its potential limitation concerning the analysis of microbial diversity. High-throughput sequencing data are inherently variable, and a larger number of biological replicates might provide greater power to detect subtler, yet biologically relevant, shifts in microbial community structure. Future studies aiming for a highly resolved comparison of microbiome dynamics might consider increasing the replication level.

5 Conclusions

The optimal rumen fermentation profiles of grape and sweet potato vines make them suitable for use as high-quality feed ingredients. However, due to fiber resistance, pepper straw has limited direct value and requires pretreatment for practical use. Despite favorable chemistry, pumpkin vines exhibited inefficient nitrogen utilization. These findings provide yak producers with ideas on how to reduce feed costs and make better use of local ingredients. They also contribute to the sustainable utilization of agricultural by-products. While this in vitro assessment is a critical first step, future in vivo trials are essential to validate nutrient availability, determine optimal inclusion rates, and evaluate long-term impacts on animal health and productivity.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, SRP610274.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Animal Care and Use Committee of Ganzi Prefecture Animal Science Research Institute. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LH: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Methodology. ZY: Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation. YZ: Writing – review & editing, Resources. YP: Writing – review & editing, Resources. RL: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Resources, Formal Analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Public Welfare Technology Application Research of Zhejiang Province of China (NO. LTGD23C040006).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acquadro S., Appleton S., Marengo A., Bicchi C., Sgorbini B., Mandrone M., et al. (2020). Grape vine green pruning residues as a promising and sustainable source of bioactive phenolic compounds. Molecules. 25, 464. doi: 10.3390/molecules25030464

Ali A. I. M., Wassie S. E., Korir D., Merbold L., Goopy J. P., Butterbach-Bahl K., et al. (2019). Supplementing tropical cattle for improved nutrient utilization and reduced enteric methane emissions. Animals. 9, 210. doi: 10.3390/ani9050210

AOAC International (2005). Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. 20th ed (Gaithersburg (MD: AOAC International).

Baba M., Nasiru A., Kark I., Muh I., and Rano N. (2017). Nutritional evaluation of sweet potato vines from twelve cultivars as feed for ruminant animals. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 13, 25–29. doi: 10.3923/ajava.2018.25.29

Bai J., Tang L., Liu M., Jiao T., and Zhao G. (2025). Effects of substituting alfalfa silage with whole plant quinoa silage on rumen fermentation characteristics and rumen microbial community of sheep in vitro. Front. Vet. Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1565497

Belanche A., Doreau M., Edwards J. E., Moorby J. M., Pinloche E., and Newbold C. J. (2012). Shifts in the rumen microbiota due to the type of carbohydrate and level of protein ingested by dairy cattle are associated with changes in rumen fermentation. J. Nutr. 142, 1684–1692. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.159574

Bhattarai S., Coulman B., Beattie A. D., and Biligetu B. (2018). Assessment of sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia Scop.) germplasm for agro-morphological traits and nutritive value. Grass Forage Sci. 73, 958–966. doi: 10.1111/gfs.12372

Bolyen E., Rideout J. R., Dillon M. R., Bokulich N. A., Abnet C. C., Al-Ghalith G. A., et al. (2019). Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9

Callahan B. J., McMurdie P. J., Rosen M. J., Han A. W., Johnson A. J. A., and Holmes S. P. (2016). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583. doi: 10.1038/NMETH.3869

Calsamiglia S., Ferret A., and Devant M. (2002). Effects of pH and pH fluctuations on microbial fermentation and nutrient flow from a dual-flow continuous culture system. J. Dairy Sci. 85, 574–579. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02(02)74111-8

Chaney A. L. and Marbach E. P. (1962). Modified reagents for determination of urea and ammonia. Clin. Chem. 8, 130–132. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/8.2.130

Chang S., Xie K., Du W., Jia Q., Yan T., Yang H., et al. (2022). Effects of mowing times on nutrient composition and in vitro digestibility of forage in three sown pastures of China loess Plateau. Animals 12, 2807. doi: 10.3390/ani12202807

Chen S., Cui C., Qi Y., Ma B., Zhang M., Jian C., et al. (2025). Studies on fatty acids and microbiota characterization of the gastrointestinal tract of Tianzhu white yaks. Front. Microbiol. 15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1508468

Chen Y. B., Lan D. L., Tang C., Yang X. N., and Li J. (2015). Effect of DNA extraction methods on the apparent structure of yak rumen microbial communities as revealed by 16S rDNA sequencing. Pol. J. Microbiol. 64, 29–36. doi: 10.33073/pjm-2015-004

Chen Q., Lyu Y., Bi J., Wu X., Jin X., Qiao Y., et al. (2019). Quality assessment and variety classification of seed-used pumpkin by-products: Potential values to deep processing. Food Sci. Nutr. 7, 4095–4104. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1276

Chen H., Sun Q., Tian C., Tang X., Ren Y., and Chen W. (2024). Assessment of the nutrient value and in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics of garlic peel, sweet potato vine, and cotton straw. Fermentation 10, 464. doi: 10.3390/FERMENTATION10090464

Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., and Gu J. (2018). Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, 1884–1890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

Costa-Silva V., Pinheiro V., Alves A., Silva J. A., Marques G., Lorenzo J., et al. (2022). Effects of dietary incorporation of grape stalks untreated and Fungi-treated in growing rabbits: a preliminary study. Animals. 12, 112. doi: 10.3390/ani12010112

Das P. P., Krishnan G., Doley J., Bhattacharya D., Deb S. M., Chakravarty P., et al. (2019). Establishing gene Amelogenin as sex-specific marker in yak by genomic approach. J. Genet. 98, 1–6. doi: 10.1007/s12041-019-1061-x

de Oliveira M. N. V., Jewell K. A., Freitas F. S., Benjamin L. A., Tótola M. R., Borges A. C., et al. (2013). Characterizing the microbiota across the gastrointestinal tract of a Brazilian Nelore steer. Vet. Microbiol. 164, 307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.02.013

Dozsa A., Dezso B., Toth B. I., Bacsi A., Poliska S., Camera E., et al. (2014). PPARγ-mediated and arachidonic acid-dependent signaling is involved in differentiation and lipid production of human sebocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 910–920. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.413

Du S., Xu M., and Yao J. (2016). Relationship between fiber degradation kinetics and chemical composition of forages and by-products in ruminants. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 44, 189–193. doi: 10.1080/09712119.2015.1031767

Dumitrache A., Tolbert A., Natzke J., Brown S. D., Davison B. H., and Ragauskas A. J. (2017). Cellulose and lignin colocalization at the plant cell wall surface limits microbial hydrolysis of Populus biomass. Green Chem. 19, 2275–2285. doi: 10.1039/C7GC00346C

El Achkar J. H., Lendormi T., Salameh D., Louka N., Maroun R. G., Lanoisellé J. L., et al. (2018). Influence of pretreatment conditions on lignocellulosic fractions and methane production from grape pomace. Bioresour. Technol. 247, 881–889. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.182

Fernandes J. M., Fraga I., Sousa R. M., Rodrigues M. A., Sampaio A., Bezerra R. M., et al. (2020). Pretreatment of grape stalks by fungi: effect on bioactive compounds, fiber composition, saccharification kinetics and monosaccharides ratio. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 5900. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165900

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2023). FAOSTAT: Crops - Chillies and peppers, green (Production Quantity) [dataset] (Rome: FAO). Available online at: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/data/QCL (Accessed August 27, 2025).

García-Rodríguez J., Ranilla M. J., France J., Alaiz-Moretón H., Carro M. D., and López S. (2019). Chemical composition, in vitro digestibility and rumen fermentation kinetics of agro-industrial by-products. Animals. 9, 861. doi: 10.3390/ani9110861

Gu Y., An L., Zhou Y., Xue G., Jiao Y., Yang D., et al. (2024). Effect of oat hay as a substitute for alfalfa hay on the gut microbiome and metabolites of yak calves. Animals 14, 3329. doi: 10.3390/ani14223329

Gunun P., Wanapat M., and Anantasook N. (2013). Effects of physical form and urea treatment of rice straw on rumen fermentation, microbial protein synthesis and nutrient digestibility in dairy steers. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 26, 1689–1697. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2013.13190

Hristov A. N., Bannink A., Crompton L. A., Huhtanen P., Kreuzer M., McGee M., et al. (2019). Invited review: Nitrogen in ruminant nutrition: A review of measurement techniques. J. Dairy Sci. 102, 5811–5852. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-15829

Ishida H., Suzuno H., Sugiyama N., Innami S., Tadokoro T., and Maekawa A. (2000). Nutritive evaluation on chemical components of leaves, stalks and stems of sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas poir). Food Chem. 68, 359–367. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(99)00206-X

Iwamoto M. and Asanuma N. (2001). Effects of pH and electron donors on nitrate and nitrite reduction in ruminal microbiota. Nihon Chikusan Gakkaiho. 72, 117–125. doi: 10.2508/chikusan.72.117

Jami E., White B. A., and Mizrahi I. (2014). Potential role of the bovine rumen microbiome in modulating milk composition and feed efficiency. PloS One 9, e85423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085423

Jiang Y., Zhou J., Chen X., Kang Y., Yan T., and Hou F. (2025). Effect of alfalfa hay quality in an alfalfa-maize diet on the digestion, metabolism, and growth rate of goats in the Longdong Loess Plateau. Grassl. Res. 4, 140–150. doi: 10.1002/glr2.70009

Jung H. G. and Allen M. S. (1995). Characteristics of plant cell walls affecting intake and digestibility of forages by ruminants. J. Anim. Sci. 73, 2774–2790. doi: 10.2527/1995.7392774x

Kansagara Y. K., Savsani H. H., Chavda M. R., Chavda J. A., Belim S. Y., Makwana K. R., et al. (2022). Rumen microbiota and nutrient metabolism: A review. Bhartiya Krishi Anusandhan Patrika 37, 320–327. doi: 10.18805/bkap486

Khiaosa-Ard R., Mahmood M., Mickdam E., Pacífico C., Meixner J., Traintinger L., et al. (2023). Winery by-products as a feed source with functional properties: dose–response effect of grape pomace, grape seed meal, and grape seed extract on rumen microbial community and their fermentation activity in RUSITEC. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 14, 92. doi: 10.1186/S40104-023-00892-7

Korićanac M., Mijalković J., Petrović P., and Pavlović N. (2025). Exploring green proteins from pumpkin leaf biomass: assessing their potential as a novel alternative protein source and functional alterations via pH-Shift treatment. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 12, 102. doi: 10.1186/s40643-025-00945-x

Kour H., Malik R., Datt C., and Rana P. (2025). A low-cost continuous rumen simulation system for sustainable in vitro fermentation and feed evaluation in ruminant production. MethodsX 15, 103581. doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2025.103581

Lee C., Oh J., Hristov A. N., Harvatine K., Vazquez-Anon M., and Zanton G. I. (2015). Effect of 2-hydroxy-4-methylthio-butanoic acid on ruminal fermentation, bacterial distribution, digestibility, and performance of lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 98, 1234–1247. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8904

Lei Y., Li X. Y., Wang Y., Li Z., Chen Y., and Yang Y. X. (2018). Determination of ruminal dry matter and crude protein degradability and degradation kinetics of several concentrate feed ingredients in cashmere goat. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 46, 134–140. doi: 10.1080/09712119.2016.1276916

Li J., Bai Y., Ma K., Ren Z., Li J., Zhang J., et al. (2022). Dihydroartemisinin alleviates deoxynivalenol induced liver apoptosis and inflammation in piglets. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 241, 113811. doi: 10.1016/J.ECOENV.2022.113811

Li J., Guo T., Zang C., Zhang Z., Guzalnur A., and Tuo Y. (2024). Effect of different pepper stalk level diets on growth performance, nutrient apparent digestibility and serum indices of Dorper ×Hu hybrid lambs. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 36, 4531–4543. doi: 10.12418/CJAN2024.389

Li J., Tuo Y., He L., Ma Y., Zhang Z., Cheng Z., et al. (2025). Effects of chili straw on rumen fermentation, meat quality, amino acid and fatty acid contents, and rumen bacteria diversity in sheep. Front. Microbiol. 15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1525612

Li Y., Zhang G. N., Fang X. P., Zhao C., Wu H. Y., Lan Y. X., et al. (2021). Effects of replacing soybean meal with pumpkin seed cake and dried distillers grains with solubles on milk performance and antioxidant functions in dairy cows. Animal 15, 100004. doi: 10.1016/j.animal.2020.100004

Liebhardt P., Maxa J., Bernhardt H., Aulrich K., and Thurner S. (2022). Comparison of a conventional harvesting technique in alfalfa and red clover with a leaf stripping technique regarding dry matter yield, total leaf mass, leaf portion, crude protein and amino acid contents. Agronomy. 12, 1408. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12061408

Lithourgidis A. S., Vasilakoglou I. B., Dhima K. V., Dordas C. A., and Yiakoulaki M. D. (2006). Forage yield and quality of common vetch mixtures with oat and triticale in two seeding ratios. Field Crops Res. 99, 106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2006.03.008

Liu H., Li Z., Pei C., Degen A., Hao L., Cao X., et al. (2022). A comparison between yaks and Qaidam cattle in in vitro rumen fermentation, methane emission, and bacterial community composition with poor quality substrate. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 291, 115395. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2022.115395

Liu C., Zhao D., Ma W., Guo Y., Wang A., Wang Q., et al. (2016). Denitrifying sulfide removal process on high-salinity wastewaters in the presence of Halomonas sp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 1421–1426. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-7039-6

Lu M., Chen C., Lan Y., Xiao J., Huang J., Huang Q., et al. (2020). Capsaicin—The major bioactive ingredient of chili peppers: Bio-efficacy and delivery systems. Food Funct. 11, 2848–2860. doi: 10.1039/D0FO00351D

Luo D., Gao Y., Lu Y., Qu M., Xiong X., Xu L., et al. (2017). Niacin alters the ruminal microbial composition of cattle under high-concentrate condition. Anim. Nutr. 3, 180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.04.005

Lv X., Chen L., Zhou C., Zhang G., Xie J., Kang J., et al. (2023). Application of different proportions of sweet sorghum silage as a substitute for corn silage in dairy cows. Food Sci. Nutr. 11, 3575–3587. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3347

Lyu Y., Bi J., Chen Q., Wu X., Qiao Y., Hou H., et al. (2021). Bioaccessibility of carotenoids and antioxidant capacity of seed-used pumpkin byproducts powders as affected by particle size and corn oil during in vitro digestion process. Food Chem. 343, 128541. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128541

Ma J., Dai H., Liu H., and Du W. (2023). Effects of harvest stages and lactic acid bacteria additives on the nutritional quality of silage derived from triticale, rye, and oat on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. PeerJ. 11, e15772. doi: 10.7717/PEERJ.15772

Macfarlane S. and Macfarlane G. T. (2003). Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc. Nutr. Soc 62, 67–72. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002207

Magoč T. and Salzberg S. L. (2011). FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507

Mao S. Y., Zhang G., and Zhu W. Y. (2008). Effect of disodium fumarate on ruminal metabolism and rumen bacterial communities as revealed by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 140, 293–306. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.04.001

McDonald P. and Edwards R. A. (1976). The influence of conservation methods on digestion and utilization of forages by ruminants. Proc. Nutr. Soc 35, 201–211. doi: 10.1079/PNS19760033

Melesse A., Steingass H., Schollenberger M., and Rodehutscord M. (2018). Component composition, in vitro gas and methane production profiles of fruit by-products and leaves of root crops. J. Agric. Sci. 156, 949–958. doi: 10.1017/S0021859618000928,2-s2.0-85058271257

Menke K. H., Raab L., Salewski A., Steingass H., Fritz D., and Schneider W. (1979). The estimation of the digestibility and metabolizable energy content of ruminant feeding stuffs from the gas production when they are incubated with rumen liquor in vitro. J. Agric. Sci. 93, 217–222. doi: 10.1017/S0021859600086305

Mijalković J., Šekuljica N., Jakovetić Tanasković S., Petrović P., Balanč B., Korićanac M., et al. (2024). Ultrasound as green technology for the valorization of pumpkin leaves: intensification of protein recovery. Molecules 29, 4027. doi: 10.3390/molecules29174027

Murphy J. J. and Kennelly J. J. (1987). Effect of protein concentration and protein source on the degradability of dry matter and protein in situ. J. Dairy Sci. 70, 1841–1849. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(87)80223-0

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2023). National data: grape planting area and output [Data set]. Available online at: http://data.stats.gov.cn (Accessed August 27, 2025).

National Research Council (2000). Nutrient requirements of beef cattle. Seventh Revised Edition (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press).

O’Hara E., Kenny D. A., McGovern E., Byrne C. J., McCabe M. S., Guan L. L., et al. (2020). Investigating temporal microbial dynamics in the rumen of beef calves raised on two farms during early life. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 96, 203. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiz203

Oliveira L. N., Pereira M. A., Oliveira C. D., Oliveira C. C., Silva R. B., Pereira R. A., et al. (2023). Effect of low dietary concentrations of Acacia mearnsii tannin extract on chewing, ruminal fermentation, digestibility, nitrogen partition, and performance of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. .106, 3203–3216. doi: 10.3168/jds.2022-22521

Peng R., Räisänen S. E., Rauch R., Rytz A., Zhang Y., Ma X., et al. (2025). Effects of tannins and additional rumen-protected protein on nitrate responses in dairy cows: Lactational performance, enteric methane emissions, nitrogen utilization, and blood metabolites. . J. Dairy Sci. 109, 372–389. doi: 10.3168/jds.2025-26786

Perović M., Bojanić N., Tomičić Z., Milošević M., Kostić M., Jugović Z. K., et al. (2025). Nutritional quality, functional properties and in vitro digestibility of protein concentrates from hull-less pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) leaves. J. Food Compos. Anal. 142, 107408. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2025.107408

Perović M. N., Knežević Jugović Z. D., and Antov M. G. (2024). Heat-induced nanoparticles from pumpkin leaf protein for potential application as β-carotene carriers. Future Foods. 9, 100310. doi: 10.1016/j.fufo.2024.100310

Scicutella F., Foggi G., Daghio M., Mannelli F., Viti C., Mele M., et al. (2025). A review of in vitro approaches as tools for studying rumen fermentation and ecology: Effectiveness compared to in vivo outcomes. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 24, 589–608. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2025.2463507

Singh K. M., Ahir V. B., Tripathi A. K., Ramani U. V., Sajnani M., Koringa P. G., et al. (2012). Metagenomic analysis of Surti buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) rumen: a preliminary study. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 4841–4848. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1278-0

Song C., Li J., Xing J., Wang C., Li J., and Shan A. (2022). Effects of molasses interacting with formic acid on the fermentation characteristics, proteolysis and microbial community of seed-used pumpkin leaves silage. J. Clean. Prod. 380, 135186. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135186

Tadesse A., Titze N., Rodehutscord M., and Melesse A. (2025). Effect of substituting concentrate mix with sweet potato vines on growth performances and carcass components of yearling rams and its potential in mitigating methane production. Vet. Med. Int. 1, 1054348. doi: 10.1155/vmi/1054348

Temoche Socola V. A., Vasquez C., Riojas J., Sessarego E., Rodríguez A., Ruiz J., et al. (2025). Optimizing harvest stage and drying time to enhance yield and nutritive quality of whole-plant Tithonia diversifolia forage meal in arid tropics. Front. Plant Sci. 16. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1644949

Tilley J. M. A. and Terry D. R. (1963). A two-stage technique for the in vitro digestion of forage crops. Grass Forage Sci. 18, 104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2494.1963.tb00335.x

Van Soest P. J., Robertson J. B., and Lewis B. A. (1991). Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 74, 3583–3597. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2

Wang R., Sun B., Yue Z., Zheng H., Zhou Q., Bao C., et al. (2022). Effects of sweet potato vine silage supplementation on meat quality, antioxidant capacity and immune function in finishing pigs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 107, 556–563. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13737

Wilman D. and Altimimi M. A. (1984). The in-vitro digestibility and chemical composition of plant parts in white clover, red clover and lucerne during primary growth. J. Sci. Food Agric. 35, 133–138. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740350203

Wu G. D., Chen J., Hoffmann C., Bittinger K., Chen Y. Y., Keilbaugh S. A., et al. (2011). Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 334, 105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344

Xiao M., Du L., Wei M., Wang Y., Dong C., Ju J., et al. (2025). Effects of quercetin on in vitro rumen fermentation parameters, gas production and microflora of beef cattle. Front. Microbiol. 16. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1527405

Zhang N., Zhou Y., Ali A., Wang T., Wang X., and Sun X. (2024). Effect of molasses addition on the fermentation quality and microbial community during mixed microstorage of seed pumpkin peel residue and sunflower stalks. Fermentation. 10, 314. doi: 10.3390/fermentation10060314