- 1School of Archaeology and Anthropology, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia

- 2IDN Being Human Lab, Institute of Psychology, University of Wroclaw, Wroclaw, Poland

Introduction

Love is an important aspect of human life. It is the glue that keeps families together, ensures the raising of viable offspring, and is the basis for romantic relationship formation (Kowal et al., 2024) and maintenance (Fletcher et al., 2015). It is understudied and the contributions that researchers make to this field should contribute to an accurate understanding of this important phenomenon. There have been circumstances where theories about love (e.g., Fisher, 1998) have been widely adopted despite lack of empirical evidence. This diminishes the work of love researchers and misdirects scientific efforts and inquiry. It also burdens the science of love with the perception that it lacks rigor and evidence. Therefore, it is important that reviews of the biology of love are complete and accurate.

One recent paper by Babková and Repiská (2025) in International Journal of Molecular Sciences aimed to review the molecular underpinnings of love. The authors reviewed primarily endocrinological studies, specifically those related to neurotrophins, cortisol, serotonin, dopamine, endorphins, testosterone, oxytocin, and vasopressin. It is unclear whether the authors are taking an inductive or deductive approach to the topic, for reasons detailed below. It appears to be somewhat inductive in that it relies exclusively on findings related to romantic love. However, it also appears somewhat deductive as it makes overarching claims which are not supported by evidence in text. Additionally, Babková and Repiská (2025) tackled potential “side effects of the modern world” on love experiences. Although we appreciate scholars' interest in love, we would like to comment on several shortcomings of the target paper which we think are important to note and clarify. We focus here on some of the main shortcomings with particular reference to romantic love, one of our areas of expertise.

Our main criticisms of Babková and Repiská (2025) are that the review (i) lacks clarity about what love is and the different types of love, (ii) is incomplete and does not include some of the biopsychological science of love, (iii) makes claims that are not supported by the evidence, and (iv) inadequately supports their claims. We attempted to have this opinion published as a comment in the journal in which the article was published, International Journal of Molecular Sciences. It was desk rejected.

Lack of clarity about what is meant by “love”

The authors do not provide a definition of love and do not clearly delineate the different types of love. This is important because different types of love (e.g., romantic love, companionate love, maternal love, filial love, love of pets, love of a god, etc.) all have both similar and unique functions (Machin, 2022). For example, romantic love serves a number of reproductive functions (Bode and Kushnick, 2021), whereas love of a pet does not. Additionally, each type of love would be characterized by shared and unique mechanisms that underly their expression (e.g., Rinne et al., 2024). The title of the article suggests that the topic of the review is love, generally, but then the authors rely entirely on studies related to romantic love.

Incompleteness

The article cites, primarily, research on romantic love. However, there are a number of important studies that are omitted. The authors fail to cite important studies on love that demonstrated activity of dopamine, endorphins, oxytocin, and vasopressin. Connected to the above point on the lack of clarity on the definition of love and which type of love is within the scope of focus, the target article also fails to reference studies on the role of neurochemicals in other types of love (e.g., maternal love).

Dopamine

The authors do not cite any studies for the claim that dopamine is involved in romantic love. They do cite one hypothesis article (Fisher et al., 2002) that proposed that dopamine plays a role in discriminating among potential partners and focuses courtship activities. There are numerous fMRI studies demonstrating involvement of dopamine rich structures, such as the mesolimbic pathway, in romantic love (for a review see Xu et al., 2015). There has also been one study (Marazziti et al., 2017) demonstrating lower density of lymphocyte dopamine transporter in individuals experiencing romantic love compared to controls, indicating an up-regulated dopamine system in romantic love.

Endorphins

The authors do not cite any studies to support the claim that opioids are involved in romantic love. Importantly, one study (Ulmer-Yaniv et al., 2016) demonstrated higher levels of beta-endorphins in people in the early stages of a romantic relationship (presumably experiencing romantic love) compared to single controls. The same study also demonstrated higher beta-endorphin levels in new parents compared to singles, suggesting a role for these neuropeptides in parental love as well. Additionally, the authors do not reference the Brain Opioid Theory of Social Attachment (see Machin and Dunbar, 2011). This theory proposes that social bonding, including both romantic and parental attachment, is mediated by the brain's opioid system, providing compelling evidence of endorphins' involvement in love.

Oxytocin and vasopressin

The authors fail to cite any of the three human studies (Schneiderman et al., 2014, 2012; Ulmer-Yaniv et al., 2016) which are suggestive of increased oxytocin activity in romantic love, one of which (Ulmer-Yaniv et al., 2016) indicates a role of oxytocin in early parental love. The authors also fail to cite studies which provide indirect evidence of vasopressin's involvement in romantic love. Specifically, studies employing fMRI techniques (see Ortigue et al., 2010 for a meta-analysis) implicate vasopressin-rich structures in romantic love and one study employing genetic and fMRI methods (Acevedo et al., 2020) implicates polymorphisms regulating oxytocin and vasopressin receptors in romantic love.

Maternal love

The second most studied type of love from a biopsychological perspective is maternal love (see Rigo et al., 2019). The authors fail to cite any studies on maternal love, which is a major shortcoming in an article purporting to review the molecular basis of love. Key studies include a meta-analysis of fMRI studies of maternal love (Rigo et al., 2019) and individual studies investigating circulating peptide levels in new parents (Ulmer-Yaniv et al., 2016), and, specifically, new mothers (Feldman et al., 2010).

Claims unsupported by evidence

The target article proposes a phases model of romantic love running from sexual desire to intimacy and emotional closeness to bonding and commitment. This is not informed by evidence and the authors provide no citation to justify this model. As active researchers of romantic love, we are not aware of any high-quality literature that provides empirical support for this model. We have never seen this model proposed elsewhere.

The authors' claim that the serotonin system is involved in the obsessive aspects of romantic love was drawn from a 2005 review (Meloy and Fisher, 2005) which considered only two fMRI studies of romantic love, relied on an outdated model of mammalian reproduction (Fisher, 1998), did not incorporate one of the serotonin studies of romantic love (Langeslag et al., 2012), and had an inaccurate outdated interpretations of another study (Marazziti et al., 1999). A review (Bode and Kushnick, 2021), hypothesis (Bode, 2023), and empirical study published since the review in question was submitted (Bode et al., 2025) have provided contradictory evidence for the hypothesis that the same serotonergic mechanisms involved in obsessive compulsive disorder are responsible for the obsessive thinking characteristic of romantic love.

Inadequate support of claims

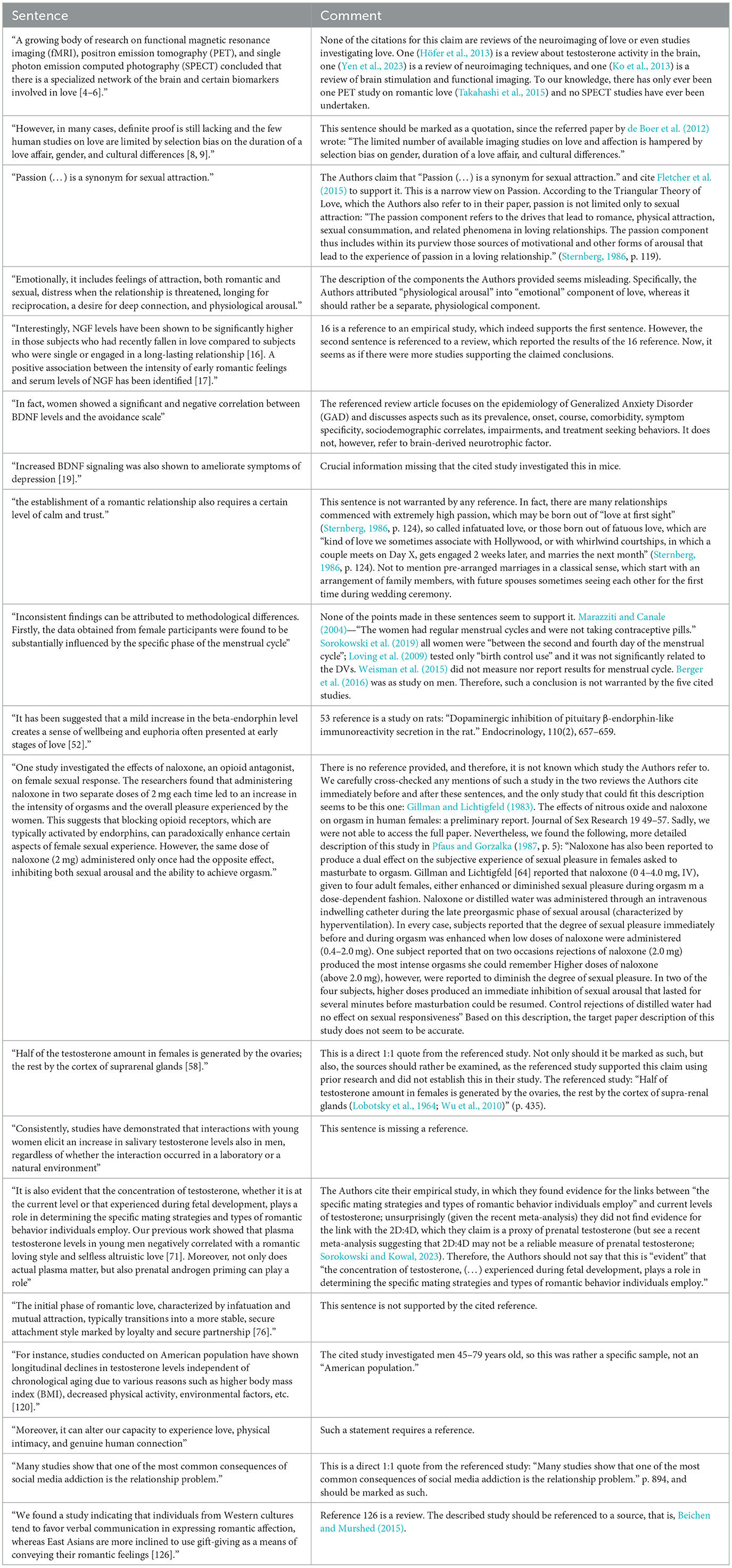

Key among our concerns is the use of inappropriate citations to justify claims. For example, the target article reads, “Recently, there has also been growing interest in understanding the biological underpinnings of love. A growing body of research on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and single photon emission computed photography (SPECT) concluded that there is a specialized network of the brain and certain biomarkers involved in love [4, 5, 6].” None of the citations for this claim are reviews of the neuroimaging of love or even studies investigating love. One (Höfer et al., 2013) is a review about testosterone activity in the brain, one (Yen et al., 2023) is a review of neuroimaging techniques, and one (Ko et al., 2013) is a review of brain stimulation and functional imaging. None of these articles include the word “love” in text. To our knowledge, there has only ever been one PET study on romantic love (Takahashi et al., 2015) and no SPECT studies have ever been undertaken. This type of mis-referencing and questionable support for claims is common throughout the article. Table 1 presents some of our concerns about the citations used in the target article.

Table 1. Concerns about citations in text of Babková and Repiská (2025).

Table 1 of the target article includes two major shortcomings. The authors intend for the table to provide a summary of the love-related molecule, psychological effect, brain region, and receptor/interacting molecule implicated in love. The authors, however, fail to provide evidence that the psychological effects stated are associated with love. Additionally, despite there being more than 20 fMRI studies of romantic love (Bode and Kowal, 2023), the authors only cite three fMRI studies of romantic love (Aron et al., 2005; Scheele et al., 2013; Song et al., 2015) and one early meta-analysis of love (Ortigue et al., 2010). Each brain region in the table should have been accompanied by a list of citations referring to fMRI studies implicating that specific brain region in love. Because of the poor reliability of fMRI studies (see Eklund et al., 2016; Elliott et al., 2020), it is important to have replicated evidence of specific brain region involvement in romantic love (see Bode and Kushnick, 2021 for an example of how this can be done). For example, a meta-analysis of nine fMRI studies of romantic love (Shih et al., 2022) found only the ventral tegmental area could be reliably associated with romantic love. Simply because a neurotransmitter or neurohormone is associated with love does not mean that it is specifically involved in all regions where that factor is active. The citations provided by the authors are insufficient evidence of involvement of all the stated brain regions in love.

Other concerns

In addition to the shortcomings detailed above, we note a number of other issues with the article, including contradictory statements, misrepresentation of studies, irrelevant considerations, and the detailed consideration of 2D:4D ratios as a proxy for prenatal testosterone exposure (something which is convincingly in doubt; see Sorokowski and Kowal, 2023). The authors also conflate passion with sexual attraction, and mischaracterize the cognitions, emotions, and behaviors of romantic love.

Suggestion for researchers

In essence, we found the review by Babková and Repiská (2025) to be incomplete and misleading. As a result, we caution researchers against relying on this review to inform their understanding of the biochemistry of love. Instead, researchers should refer to established and rigorous reviews in the literature (e.g., Bode and Kushnick, 2021) individual studies (see Bode and Kowal, 2023 for a list of biological studies of romantic love), and theory (e.g., Bode, 2023) to guide an appreciation of the biochemistry of romantic love. Additionally, other works can provide insights into the biochemistry of maternal love (Rigo et al., 2019).

Author contributions

AB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. MK was supported by the Foundation for Polish Science START Scholarship.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acevedo, B. P., Poulin, M. J., Collins, N. L., and Brown, L. L. (2020). After the honeymoon: neural and genetic correlates of romantic love in newlywed marriages. Front. Psychol. 11:634. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00634

Aron, A., Fisher, H., Mashek, D. J., Strong, G., Li, H. F., and Brown, L. L. (2005). Reward, motivation, and emotion systems associated with early-stage intense romantic love. J. Neurophysiol. 94, 327–337. doi: 10.1152/jn.00838.2004

Babková, J., and Repiská, G. (2025). The molecular basis of love. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26:1533. doi: 10.3390/ijms26041533

Beichen, L., and Murshed, F. (2015). Culture, expressions of romantic love, and gift-giving. J. Int. Bus. Res. 14, 68–84.

Berger, J., Heinrichs, M., von Dawans, B., Way, B. M., and Chen, F. S. (2016). Cortisol modulates men's affiliative responses to acute social stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 63, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.004

Bode, A. (2023). Romantic love evolved by co-opting mother-infant bonding. Front. Psychol. 14:1176067. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1176067

Bode, A., and Kowal, M. (2023). Toward consistent reporting of sample characteristics in studies investigating the biological mechanisms of romantic love. Front. Psychol. 14:983419. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.983419

Bode, A., Kowal, M., Cannas Aghedu, F., and Kavanagh, P. S. (2025). SSRI use is not associated with the intensity of romantic love, obsessive thinking about a loved one, commitment, or sexual frequency in a sample of young adults experiencing romantic love. J. Affect. Disord. 375, 472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2025.01.103

Bode, A., and Kushnick, G. (2021). Proximate and ultimate perspectives on romantic love. Front. Psychol. 12:573123. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.573123

de Boer, A., van Buel, E. M., and Ter Horst, G. J. (2012). Love is more than just a kiss: a neurobiological perspective on love and affection. Neuroscience 201, 114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.11.017

Eklund, A., Nichols, T. E., and Knutsson, H. (2016). Cluster failure: why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 7900–7905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602413113

Elliott, M. L., Knodt, A. R., Ireland, D., Morris, M. L., Poulton, R., Ramrakha, S., et al. (2020). What is the test-retest reliability of common task-functional MRI measures? N. Empir. Evid. Meta Anal. Psychol. Sci. 31, 792–806. doi: 10.1177/0956797620916786

Feldman, R., Gordon, I., Schneiderman, I., Weisman, O., and Zagoory-Sharon, O. (2010). Natural variations in maternal and paternal care are associated with systematic changes in oxytocin following parent-infant contact. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 1133–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.01.013

Fisher, H., Aron, A., Mashek, D., Li, H., Strong, G., and Brown, L. L. (2002). The neural mechanisms of mate choice: a hypothesis. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 23(Suppl. 4), 92–97. doi: 10.1023/a:1019888024255

Fisher, H. E. (1998). Lust, attraction, and attachment in mammalian reproduction. Hum. Nat. 9, 23–52. doi: 10.1007/s12110-998-1010-5

Fletcher, G. J. O., Simpson, J. A., Campbell, L., and Overall, N. C. (2015). Pair-bonding, romantic love, and evolution: the curious case of Homo sapiens. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 20–36. doi: 10.1177/1745691614561683

Gillman, M. A., and Lichtigfeld, F. J. (1983). “Naloxone fails to antagonize nitrous oxide analgesia for clinical pain”: comment. Pain 17, 103–104. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90134-3

Höfer, P., Lanzenberger, R., and Kasper, S. (2013). Testosterone in the brain: neuroimaging findings and the potential role for neuropsychopharmacology. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 23, 79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.04.013

Ko, J. H., Tang, C. C., and Eidelberg, D. (2013). “Chapter 8 - brain stimulation and functional imaging with fMRI and PET,” in Handbook of Clinical Neurology, vol. 116, eds. A. M. Lozano and M. Hallett (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 77–95. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53497-2.00008-5

Kowal, M., Bode, A., Koszałkowska, K., Roberts, S. C., Gjoneska, B., Frederick, D., et al. (2024). Love as a commitment device. Hum. Nat. 35, 430–450. doi: 10.1007/s12110-024-09482-6

Langeslag, S. J. E., van der Veen, F. M., and Fekkes, D. (2012). Blood levels of serotonin are differentially affected by romantic love in men and women. J. Psychophysiol. 26, 92–98. doi: 10.1027/0269-8803/a000071

Lobotsky, J., Wyss, H. I., Segre, E. J., and Lloyd, C. W. (1964). Plasma testosterone in the normal woman. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 24, 1261–1265. doi: 10.1210/jcem-24-12-1261

Loving, T. J., Crockett, E. E., and Paxson, A. A. (2009). Passionate love and relationship thinkers: experimental evidence for acute cortisol elevations in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34, 939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.01.010

Machin, A. J., and Dunbar, R. I. M. (2011). The brain opioid theory of social attachment: a review of the evidence. Behaviour 148, 985–1025. doi: 10.1163/000579511X596624

Marazziti, D., Akiskal, H. S., Rossi, A., and Cassano, G. B. (1999). Alteration of the platelet serotonin transporter in romantic love. Psychol. Med. 29, 741–745. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798007946

Marazziti, D., Baroni, S., Giannaccini, G., Piccinni, A., Mucci, F., Catena-Dell‘Osso, M., et al. (2017). Decreased lymphocyte dopamine transporter in romantic lovers. CNS Spectr. 22, 290–294. doi: 10.1017/S109285291600050X

Marazziti, D., and Canale, D. (2004). Hormonal changes when falling in love. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29, 931–936. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.08.006

Meloy, J., and Fisher, H. (2005). Some thoughts on the neurobiology of stalking. J. Forensic Sci. 50:JFS2004508-2004509. doi: 10.1520/JFS2004508

Ortigue, S., Bianchi-Demicheli, F., Patel, N., Frum, C., and Lewis, J. W. (2010). Neuroimaging of love: fMRI meta-analysis evidence toward new perspectives in sexual medicine. J. Sex. Med. 7, 3541–3552. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01999.x

Pfaus, J. G., and Gorzalka, B. B. (1987). Opioids and sexual behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 11, 1–34. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(87)80002-7

Rigo, P., Kim, P., Esposito, G., Putnick, D. L., Venuti, P., and Bornstein, M. H. (2019). Specific maternal brain responses to their own child's face: an fMRI meta-analysis. Dev. Rev. 51, 58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2018.12.001

Rinne, P., Lahnakoski, J. M., Saarimäki, H., Tavast, M., Sams, M., and Henriksson, L. (2024). Six types of loves differentially recruit reward and social cognition brain areas. Cereb. Cortex 34:bhae331. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhae331

Scheele, D., Wille, A., Kendrick, K. M., Stoffel-Wagner, B., Becker, B., Gunturkun, O., et al. (2013). Oxytocin enhances brain reward system responses in men viewing the face of their female partner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 20308–20313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314190110

Schneiderman, I., Kanat-Maymon, Y., Zagoory-Sharon, O., and Feldman, R. (2014). Mutual influences between partners' hormones shape conflict dialog and relationship duration at the initiation of romantic love. Soc. Neurosci. 9, 337–351. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2014.893925

Schneiderman, I., Zagoory-Sharon, O., Leckman, J. F., and Feldman, R. (2012). Oxytocin during the initial stages of romantic attachment: relations to couples' interactive reciprocity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, 1277–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.12.021

Shih, H.-C., Kuo, M.-E., Wu, C. W., Chao, Y.-P., Huang, H.-W., and Huang, C.-M. (2022). The neurobiological basis of love: a meta-analysis of human functional neuroimaging studies of maternal and passionate love. Brain Sci. 12:830. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12070830

Song, H. W., Zou, Z. L., Kou, J., Liu, Y., Yang, L. Z., Zilverstand, A., et al. (2015). Love-related changes in the brain: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9:13. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00071

Sorokowski, P., and Kowal, M. (2023). Relationship between the 2D:4D and prenatal testosterone, adult level testosterone, and testosterone change: meta-analysis of 54 studies. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 183, 20–38. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.24852

Sorokowski, P., Zelazniewicz, A., Nowak, J., Groyecka, A., Kaleta, M., Lech, W., et al. (2019). romantic love and reproductive hormones in women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:4224. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16214224

Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychol. Rev. 93, 119–135. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.93.2.119

Takahashi, K., Mizuno, K., Sasaki, A. T., Wada, Y., Tanaka, M., Ishii, A., et al. (2015). Imaging the passionate stage of romantic love by dopamine dynamics. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9:6. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00191

Ulmer-Yaniv, A., Avitsur, R., Kanat-Maymon, Y., Schneiderman, I., Zagoory-Sharon, O., and Feldman, R. (2016). Affiliation, reward, and immune biomarkers coalesce to support social synchrony during periods of bond formation in humans. Brain Behav. Immun. 56, 130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.02.017

Weisman, O., Schneiderman, I., Zagoory-Sharon, O., and Feldman, R. (2015). Early stage romantic love is associated with reduced daily cortisol production. Adapt. Hum. Behav. Physiol. 1, 41–53. doi: 10.1007/s40750-014-0007-z

Wu, F. C., Tajar, A., Beynon, J. M., Pye, S. R., Silman, A. J., Finn, J. D., et al. (2010). Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911101

Xu, X. M., Weng, X. C., and Aron, A. (2015). “The mesolimbic dopamine pathway and romantic love,” in Brain Mapping: An Encyclopedic Reference, eds. A. W. Toga, M. M. Mesulam, and S. Kastner (Oxford: Elsevier). doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397025-1.00057-9

Keywords: biology, love, romantic love, molecular science, review, comment

Citation: Bode A and Kowal M (2025) We know more and less about love: a comment on Babková and Repiská (2025). Front. Behav. Neurosci. 19:1602582. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2025.1602582

Received: 30 March 2025; Accepted: 07 July 2025;

Published: 31 July 2025.

Edited by:

Federico d'Oleire Uquillas, Princeton University, United StatesReviewed by:

Barnaby James Wyld Dixson, The University of Queensland, AustraliaCopyright © 2025 Bode and Kowal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adam Bode, YWRhbS5ib2RlQGFudS5lZHUuYXU=

†ORCID: Adam Bode orcid.org/0000-0003-4593-5179

Marta Kowal orcid.org/0000-0001-9050-1471

Adam Bode

Adam Bode Marta Kowal

Marta Kowal