Abstract

Background:

Although beta-blockers improve clinical outcomes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, the benefit of beta-blockers in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is uncertain. Global longitudinal strain (GLS) is a robust predictor of heart failure outcomes, and recent studies have shown that beta-blockers are associated with improved survival in those with low GLS (GLS <14%) but not in those with GLS ≥14% among patients with LVEF ≥40%. Therefore, the objective of this trial is to evaluate the effect of sustained-release carvedilol (carvedilol-SR) on the outcome [N-terminal pro-B-natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) concentration] in patients with hypertension and HFpEF and will assess the differential effects of these drugs on the outcome, according to the GLS categories.

Methods:

This prospective randomized double-blind multicenter trial (CARE-preserved HF) will include 100 patients with HFpEF from three tertiary hospitals in South Korea. Patients with HFpEF and hypertension aged ≥20 years who have evidence of functional and structural heart disease on echocardiography and elevated natriuretic peptide will be enrolled. Eligible participants will be randomized 1:1 to either the carvedilol-SR group (n = 50) or the placebo group (n = 50). Patients in the carvedilol-SR group will receive 8, 16, 32, or 64 mg carvedilol-SR once daily for 6 months, and the dose of carvedilol will be up-titrated at the discretion of the treating physicians. The primary efficacy outcome was the time-averaged proportional change in N-terminal pro-B-natriuretic peptide concentration from baseline to months 3 and 6. We will also evaluate the differential effects of carvedilol-SR on primary outcomes according to GLS, using a cut-off of 14% or the median value.

Discussion:

This randomized controlled trial will investigate the efficacy and safety of carvedilol-SR in patients with HFpEF and hypertension.

Clinical Trial Registration:

ClinicalTrial.gov, identifier NCT05553314.

Introduction

The prevalence of heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is increasing (1–3). Approximately 50% of all HF patients have HFpEF, and in the general population aged ≥60 years, over 4% were identified with HFpEF (4–7). Beta-blockers are known to reduce mortality in HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (8) and are recommended by current guidelines (9–11). However, the effects of beta-blockers on HFpEF remain controversial. The SENIORS randomized controlled trial, examining the effects of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular admissions, revealed an overall benefit in patients with an left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) >35% (12); however, the study had insufficient patients and events to draw any conclusions in those with a more preserved LVEF (LVEF ≥50%). In previous randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses, the effect of beta-blockers was not consistent in patients with HFpEF (13–16). Also, in many real-world cohorts, the use of beta-blockers in patients with HFpEF is not associated with improved clinical outcomes of HF (17, 18). Although a recent meta-analysis including 16 randomized trials or observational cohort studies showed that beta-blocker therapy reduces all-cause mortality in patients with HFpEF (15), the benefit of beta-blockers in HFpEF is considered unclear. In addition, a post hoc analysis of the TOPCAT trial showed that beta-blockers were associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for HF in patients with HFpEF (19). However, in real-world clinical practice or recent trials, a large proportion of patients with HFpEF are currently receiving beta-blockers (19–22), reflecting the potential benefits of beta-blockers in HFpEF through sympathetic antagonism, including lower blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) and prolong diastolic filling time (16, 23).

Myocardial strain is based on the speckle-tracking method and is an emerging parameter for evaluating the systolic function of the heart in a more sophisticated manner than conventional methods (24, 25). In a recent study, Park et al. showed that left ventricular (LV) global longitudinal strain (GLS) was a better predictor of clinical outcomes than LVEF and that patients with similar GLS had similar prognoses, regardless of LVEF (26). Moreover, a significant proportion of patients with HFpEF have low GLS despite preserved LVEF (27). Recently, in a retrospective study of 1,969 patients with HF and LVEF of ≥40%, beta-blockers were associated with improved survival in those with low GLS (GLS <14%) but not in those with GLS ≥14% (28).

Because HFpEF is a heterogeneous and complex syndrome rather than a single disease entity (7), we hypothesized that GLS may be a factor determining the effects of beta-blockers in HFpEF. Carvedilol is a non-selective beta-blocker that has been extensively studied in patients with HFrEF (8, 29). Recently, sustained-release carvedilol (carvedilol-SR) has been developed, which can maintain an effective plasma concentration without exceeding the critical level for adverse effects (30). Carvedilol-SR has the advantage of being administered only once a day compared with the twice-daily administration of immediate-release carvedilol (carvedilol-IR). Therefore, this trial aim to evaluate the efficacy of carvedilol-SR on the outcome [N-terminal pro-B-natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) concentration] in patients with hypertension and HFpEF, and will assess the differential effects of these drugs on the outcome, according to GLS categories.

Methods and analysis

Study design

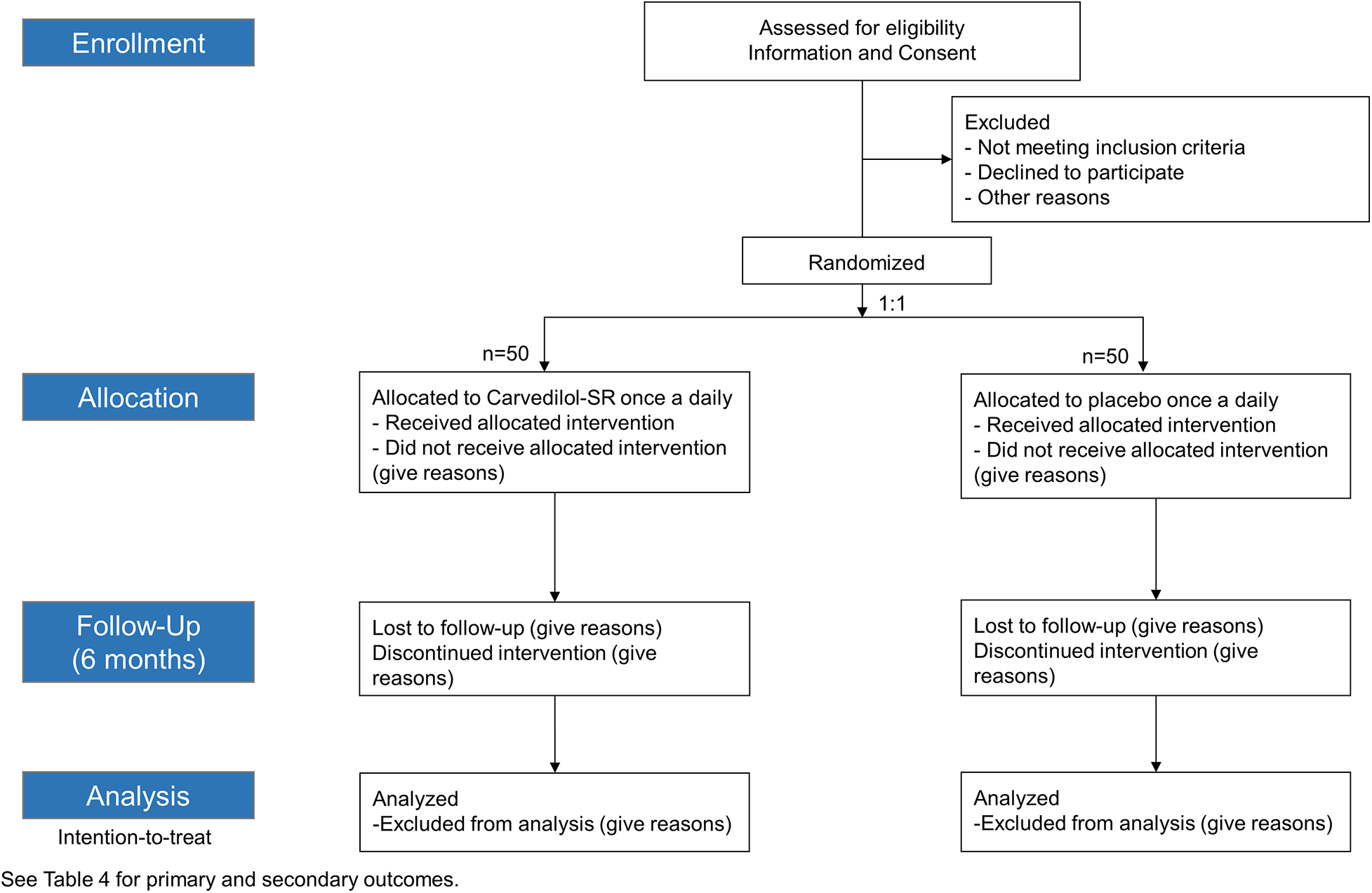

Sustained-release CARvedilol in patients with hypErtension and Heart failure with Preserved ejection fraction (CARE-preserved HF) is a multicenter, prospective, randomized, double blinded, phase 4 pilot study that assesses the efficacy of carvedilol-SR compared with placebo in patients with hypertension and HFpEF. The study flow chart is presented in Figure 1. Three tertiary university hospitals in South Korea participated in the study. Enrollment began in November 2021, is ongoing and is expected to be completed by early 2024. The trial design was registered at ClinicalTrial.gov (NCT05553314).

Figure 1

Study flowchart. Carvedilol-SR, sustained-release carvedilol.

Study population

We have been enrolling patients with hypertension and HFpEF aged ≥20 years. Patients must have symptoms of HF and elevated natriuretic peptides at the screening visit: NT-proBNP ≥220 pg/ml [or B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) ≥80 pg/ml] for patients with sinus rhythm (SR), or ≥660 pg/ml (or BNP ≥240 pg/ml) for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). For the hypertension criteria: (1) patients' average systolic blood pressure (SBP) must be ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, obtained from BP measured three times on the reference arm in the sitting position at screening; (2) for those taking anti-hypertensive medications who are on stable antihypertensive dosage that has not been adjusted for 8 weeks, the SBP must be ≥110 mmHg. Patients with SBP <110 mmHg or resting HR <60 beats/min at the screening visit will be excluded. For the HFpEF criteria, we referred to the consensus recommendation of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (31). LVEF should be ≥50% on echocardiography within 2 months before randomization. In addition, patients should have one or both of the following evidence of structural heart disease: (a) left atrial volume index ≥29 ml/m2 in patients with SR or ≥34 ml/m2 in patients with AF, (b) left ventricular mass index ≥115 g/m2 in males or ≥95 g/m2 in females. Patients should also have at least one indication of functional heart disease in terms of average E/e', septal and lateral e', peak tricuspid regurgitation velocity, and pulmonary artery systolic pressure. Patients will be excluded if they are taking any beta-blockers within 4 weeks prior to enrollment or if they have a contraindication to beta-blockers. Patients with severe chronic kidney disease (creatinine >2.4 mg/dl) or liver enzyme levels three times the normal upper limit will be excluded. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

AF, atrial fibrillation; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GLS, global longitudinal strain; HF, heart failure; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SR, sinus rhythm.

HF symptoms include dyspnea on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, or leg swelling.

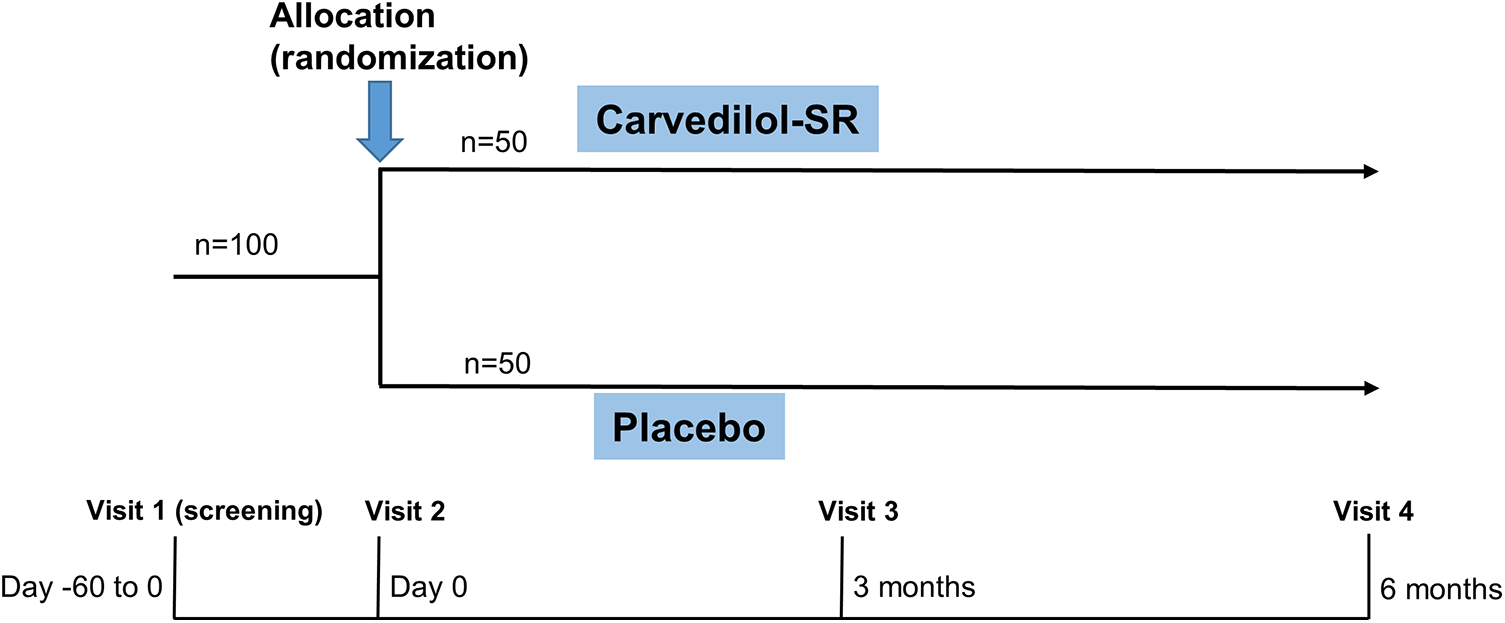

Patient recruitment and randomization

Potential participants will be screened (visit 1) on an outpatient or inpatient basis (Figure 2). After a comprehensive interview, eligible participants will be asked to provide written informed consent to participate in the trial. A baseline survey of eligible participants covering demographics and cardiovascular comorbidities will be conducted by research nurses (Table 2). Then, using a web-based central randomization service (http://matrixmdr.com), eligible participants will then be randomly assigned to either the carvedilol-SR group or the placebo group in a 1:1 ratio (visit 2). The randomization block will be generated by an independent statistician unrelated to this study using the SAS randomization program.

Figure 2

Study design of CARE-preserved HF. Patients will be randomized to either carvedilol-SR group or placebo groups. Carvedilol-SR, sustained-release carvedilol.

Table 2

| Study period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolment (screening) | Allocation | Post-allocation | Close-out | |

| Timepoint | Visit 1 (day −60–0) | Visit 2 (day 0) | Visit 2 (3 months) | Visit 3 (6 months) |

| Enrolment | ||||

| Eligibility screen | X | |||

| Informed consent | X | |||

| Allocation | X | |||

| Interventions | ||||

| Intervention |

|

|||

| Control |

|

|||

| Assessments | ||||

| Baseline characteristics | X | |||

| NT-proBNP | X | X | X | |

| Echocardiography | X | X | ||

| 12 lead electrocardiogram | X | |||

| Vital signs | X | X | X | X |

| Secondary endpoints | X | X | X | |

Standard protocol items: recommendation for interventional trials (SPIRIT) checklist.

NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

Intervention and follow-up

After randomization, patients in the carvedilol-SR group will receive carvedilol-SR 8, 16, 32, or 64 mg once daily for 6 months. Carvedilol-SR (trade name: Dilatrend SR) was manufactured and distributed by Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical Corporation in South Korea. The carvedilol dose will be up-titrated at the discretion of the treating physician. The use of beta-blockers other than carvedilol will not be allowed during the study. To avoid drug-drug interactions that may cause confounding effects, drugs with potential pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interference will be prohibited during clinical trials (Table 3).

Table 3

| Contraindication details |

|---|

|

Drugs contraindicated during this clinical trial.

Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and antiarrhythmics should be used with caution.

Follow-up visits will be scheduled at 3 (visit 3) and 6 (visit 4) months after randomization (Figure 2 and Table 2). Each clinic visit comprises history-taking, physical examination, laboratory tests, and echocardiography. Drug compliance, adverse effects, and the use of additional concomitant drugs will also be checked. Unscheduled visits will be recorded.

Study outcomes and variables

The outcomes of this study are presented in Table 4. The primary efficacy outcome will be the time-averaged proportional change in NT-proBNP concentration from baseline through months 3 and 6. The secondary endpoints included the proportion of patients with an NT-proBNP decrease >20% from baseline through months 3 and 6, composite of all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization at 6 months. We will also assess changes in BP, HR, New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, and quality of life at 6 months. Rate of BP control were under controlled will be compared between the two groups, which is defined as SBP <140 mmHg and diastolic BP <90 mmHg at 6 months. In addition, drug adherence and changes in echocardiographic parameters, including left atrial volume index, left ventricular mass index, E/e', e', pulmonary artery systolic pressure, and GLS will be assessed between the two groups. All adverse reactions and the incidence of the following adverse events of special interest during treatment will be assessed: symptomatic hypotension and bradycardia (investigator-reported).

Table 4

| Endpoints detail | |

|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | Time-averaged proportional change in NT-proBNP concentration from baseline through months 3 and 6 |

| Secondary endpoints | Proportion of patients with NT-proBNP decrease >20% from baseline through months 3 and 6 |

| Composite of all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization at 6 months | |

| Change in blood pressure and heart rate at 6 months | |

| Rate of blood pressure control at 6 months | |

| Change in NYHA classification at 6 months | |

| Change in quality of life assessed by visual analog scale (0–10) | |

| Drug adherence at 6 months | |

| Changes in echocardiographic parameter including LAVI, LVMI, E/e’, e’, pulmonary artery systolic pressure and GLS at 6 months |

Primary and secondary endpoints.

GLS, global longitudinal strain; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Blood sampling tests at the screening visit will be conducted by the laboratories at each participating institute, which are certified by the Korean Association of Quality Assurance for Clinical Laboratory. Measurement of NT-proBNP by an electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay method using cobas® 8,000 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) will be performed in a central laboratory at randomization and at 6 months (visit 4). Quality of life will be assessed using a visual analog scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 being the worst and 10 being best. Drug adherence will be assessed by “pill count” measurements. The patients will bring the remaining tables to each scheduled visit, and trained and certified researchers will count the number of returned drugs and calculate drug adherence as follows:Baseline echocardiographic data collected within 2 months before randomization will be used. All images will be obtained using a standard ultrasound system with 2.5 MHz probes manufactured by GE, Phillips, and Siemens. Standard techniques will be used to obtain the M-mode, two-dimensional, and Doppler measurements. The LV dimensions, LVEF, and other echocardiographic parameters will be obtained according to the guidelines of American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (32). Echocardiographic parameters at each institution will be archived in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format. GLS will be evaluated by a central echocardiography laboratory at the Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. GLS will be assessed using two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography (2D-STE) on index echocardiography (33). The 2D-STE data will be analyzed using TomTec software (Image Arena 4.6, Munich, Germany) for deformation analyses (2-dimensional cardiac performance analysis) (27). For deformation analysis, endocardial borders are traced on the end-systolic frame in three apical views (4-, 2-, and 3-chamber), with end-systole defined by the QRS complex or as the smallest LV volume during the cardiac cycle. The software tracks speckles along the endocardial border and myocardium throughout the cardiac cycle. The peak longitudinal strain is computed automatically, generating regional data from six segments (anterior, anteroseptal, anterolateral, inferior, inferoseptal, and inferolateral) and an average value for each view. The GLS is determined as the average peak longitudinal strain of 18 LV segments from standard apical views. For patients with SR, analyses will be performed on a single cardiac cycle; for patients with AF, the strain values will be calculated as the average of three cardiac cycles. All strain measurements will be performed by strain specialists who are blinded to other data of each patient. All strain analyses will be performed by a single investigator. In our previous study, intra-observer variability in GLS was assessed in 30 randomly selected patients (34). The coefficient of variation has been identified as 5.8% for the GLS, and the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.95 for GLS [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.91–0.98].

Sample size and statistical analysis

To date, no previous study has evaluated the effects of carvedilol-SR on HFpEF. Due to the absence of prior research and the pioneering nature of our intervention, a sample size calculation was not conducted at this preliminary stage. As this was a pilot study to explore the benefit of carvedilol-SR for HFpEF, we decided to enroll a total of 100 participants (50 in the carvedilol-SR group and 50 in the control group) across the three institutes, considering the duration of the study and the number of participating hospitals.

Categorical variables will be reported as frequencies (percentages), and continuous variables will be expressed as means ± standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges. Categorical variables will be compared using Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, and continuous variables will be compared using Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test.

Primary analysis of the proportional change in NT-proBNP concentration from baseline on a logarithmic scale will be performed using an analysis of covariance model with an adjustment for the baseline value. This will be calculated as the average of the geometric means of NT-proBNP at months 3 and 6 divided by the geometric mean of NT-proBNP at baseline in a natural logarithmic scale (i.e., ratio of geometric means) and summarized as the difference between the treatment groups in the ratio of the geometric means. Cumulative clinical-event rates will be calculated according to the Kaplan–Meier method, and the differences in clinical outcomes between the two treatment groups will be assessed using the log-rank test. Hazard ratios and associated 95% CIs will be calculated using a Cox proportional-hazards model. The incidence of adverse events will be calculated as relative risks with associated 95% CIs.

Missing values due to unevaluable samples or early study discontinuation will not be imputed. Patients with missing baseline NT-proBNP and/or missing 3 and 6 months will not be included in the primary analysis. The data will be primarily analyzed using intention-to-treat analysis, including all randomized patients. We will also perform a per-protocol analysis, which include all randomized patients who receive at least one dose of the study drug during the double-blind period and have no major protocol deviations. Safety outcomes will be analyzed in the safety set of patients who received the trial drug at least once.

Primarily, we will assess the efficacy of carvedilol-SR on the reduction of NT-proBNP in HFpEF compared with a placebo. In addition, we will evaluate the differential effects of carvedilol-SR on primary outcomes according to prespecified variables, including baseline GLS, and NT-proBNP, LVEF. We planned to use the cutoff value of 14% GLS, taking into account a previous study (28), and also planned to use the median cutoff value of the GLS.

All tests will be two-tailed, and a P-value <0.05 will be considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses will be performed using R version 4.2.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Discussion

This randomized controlled trial will investigate the efficacy and safety of carvedilol-SR in reducing NT-proBNP levels in patients with HFpEF and hypertension. We believe that this prospective double-blind multicenter trial will be particularly helpful in evaluating the differential effects of these drugs on HFpEF according to GLS.

The effects of beta-blockers on patients with HFpEF remain controversial. The SENIORS trial sub-analysis showed a trend towards a beneficial effect of nebivolol on HF outcomes in patients with LVEF >35% (12). However, the proportion of patients with LVEF ≥50% was not high (only 15%), limiting the ability to draw conclusions about HFpEF. Recently, in a HFpEF analysis in the SwedeHF registry, β-blockers were not associated with a change in risk for HF admissions or cardiovascular deaths (17). In addition, in the largest propensity score-adjusted cohort of 435,897 patients with HF and EF ≥40%, beta-blocker use was associated with a higher risk of HF hospitalization as EF increased (18). Potential benefits were observed in patients with HF with mildly reduced EF, while potential risks were observed in patients with higher EF (particularly >60%). Although a more recent meta-analysis showed that beta-blocker therapy reduced all-cause mortality in patients with HFpEF (15), overall, the results of studies on the benefits of beta-blockers in HFpEF are inconsistent, and LVEF may be an important predictor of response to beta-blockers in HFpEF. Moreover, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and coronary artery disease are common comorbidities that may benefit from beta-blockers in patients with HFpEF. Based on previous studies, we designed a trial of carvedilol SR in patients with HFpEF and hypertension. Considering only a few randomized clinical trials were performed and the LVEF cut-off value was different among studies (12–14), we will enroll patients with LVEF ≥50% and hypertension, regardless of atrial fibrillation or coronary artery disease.

Several drugs that have been shown to be effective in HFrEF have failed to reduce mortality in patients with HFpEF (20, 35–37). Because HFpEF is a heterogeneous and complex syndrome rather than a single disease entity, medical therapy can be challenging, and only specific phenotypes may respond to a particular therapeutic intervention (7, 38). Given the clinical importance of identifying a group for whom beta-blockers are effective in HFpEF, we assumed that GLS could be used to identify patients with HFpEF who would benefit from these drugs. The previous study showed that beta-blockers were associated with improved survival in patients with low GLS (GLS <14%) but not in those with GLS ≥14% among patients with LVEF of ≥40% (28). Although this previous study differs from ours in that it included patients with HF who had mildly reduced ejection fraction (LVEF 41%–49%) and focused on 5-year mortality, which exceeds that of the present study, we hypothesized that patients with HFpEF and reduced GLS might benefit similarly from beta blockers, like those with HFrEF, among whom most patients have reduced GLS. Therefore, we will measure the GLS at the central echocardiography laboratory and analyze the differential effect of carvedilol-SR on change in NT-proBNP level according to the GLS categories. We will use the cutoff value of 14% GLS based on a previous study (28), and also plan to use the median cutoff value of the GLS.

The mechanism by which beta-blockers may confer benefits in HFpEF is not clearly understood. The main potential mechanism includes sympathetic antagonism of beta-blockers with the potential benefits of lowering BP and R, enhancing relaxation, increasing diastolic filling, improving ventricular remodeling, decreasing myocardial oxygen demand, and lowering arrhythmic threshold (16, 23). Moreover, beta-blockers might confer benefit in HFpEF through improving metabolic activity and endothelial inflammation. Because the effectiveness of beta-blockers in HFpEF has not been clearly demonstrated in large trials and the mechanisms are not well understood, these limitations led us to conduct a pilot randomized controlled trial to investigate the effectiveness of beta-blockers in HFpEF.

There are at least 20 commercially available beta-blockers for clinical use. Although beta-blockers share common mechanisms, they differ in their specific activities, particularly in their selectivity for the adrenergic receptors (16, 39). Carvedilol, one of the third-generation beta-blockers, has a nonselective alpha-1, beta-1, and beta-2 adrenergic activities and has been extensively studied in patients with HFrEF (8, 29). Some studies have shown that carvedilol improve diastolic dysfunction, cardiac remodeling, or NYHA functional class in HFpEF (40–42). Although we presume that there might be a class effect of beta-blockers in HFpEF rather than a specific drug effect, we decided to evaluate the effect of carvedilol-SR in HFpEF, taking into account data from these previous studies.

Many patients with HF are older and have multiple comorbidities; therefore, they take multiple medications (1). Complex medication regimens lead to poor medication adherence and poor clinical outcomes (43). In addition, the high levels of medication adherence observed in well-controlled clinical trials may differ from those observed in real-world clinical practice. To improve drug compliance with carvedilol, a longer-acting carvedilol-SR has been developed and is known to maintain an effective plasma concentration without exceeding the critical value for adverse effects (30). Carvedilol-SR has the advantage of being administered only once a day and is non-inferior to standard carvedilol-IR administered twice a day in patients with HFrEF (44). Therefore, we used long-acting carvedilol-SR instead of carvedilol-IR in this study population with HFpEF and hypertension, which may represent a potential strength.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several limitations. First, it will only include East Asian patients, raising concerns about the extrapolation of these results to other ethnicities. Second, the number of participants to be enrolled in this study is not large, and it has a pilot study perspective. Third, the carvedilol dose will be up-titrated at the discretion of the treating physician and not according to the standard protocol in this trial, which could be a confounding factor. Fourth, the primary endpoint, change in NT-proBNP levels is a surrogate marker and may be influenced by confounding factors, such as the usage or dose of diuretics, which may be unequally controlled between the two groups. A high body mass index may also affect the level of this biomarker. Fifth, there will be no objective measure of functional status in terms of the 6-minute walk test or maximal oxygen uptake from the cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Despite these limitations, a major strength is that this study is a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded controlled trial with a novel design to evaluate the efficacy of carvedilol-SR in patients with hypertension and HFpEF and to assess the differential effects of these drugs according to GLS.

Statements

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB B-2003-601-002). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. S-JP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. B-SY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. D-JC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This project is an investigator-initiated trial and is funded by an unrestricted grant from Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical Corporation. Chong Kun Dang is a manufacturer of original formulation of carvedilol-SR in Republic of Korea. This work was Supported by grant no 18-2023-0015 from the SNUBH Research Fund. This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI21C1074).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Tsao CW Aday AW Almarzooq ZI Anderson CAM Arora P Avery CL et al Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. (2023) 147(8):e93–e621. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123

2.

Oktay AA Rich JD Shah SJ . The emerging epidemic of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Curr Heart Fail Rep. (2013) 10(4):401–10. 10.1007/s11897-013-0155-7

3.

Park JJ Lee CJ Park SJ Choi JO Choi S Park SM et al Heart failure statistics in Korea, 2020: a report from the Korean society of heart failure. Int J Heart Fail. (2021) 3(4):224–36. 10.36628/ijhf.2021.0023

4.

Steinberg BA Zhao X Heidenreich PA Peterson ED Bhatt DL Cannon CP et al Trends in patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence, therapies, and outcomes. Circulation. (2012) 126(1):65–75. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.080770

5.

van Riet EE Hoes AW Wagenaar KP Limburg A Landman MA Rutten FH . Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. A systematic review. Eur J Heart Fail. (2016) 18(3):242–52. 10.1002/ejhf.483

6.

Clark KAA Reinhardt SW Chouairi F Miller PE Kay B Fuery M et al Trends in heart failure hospitalizations in the US from 2008 to 2018. J Card Fail. (2022) 28(2):171–80. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.08.020

7.

Shim CY . Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the major unmet need in cardiology. Korean Circ J. (2020) 50(12):1051–61. 10.4070/kcj.2020.0338

8.

Packer M Bristow MR Cohn JN Colucci WS Fowler MB Gilbert EM et al The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. U.S. Carvedilol heart failure study group. N Engl J Med. (1996) 334(21):1349–55. 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101

9.

Heidenreich PA Bozkurt B Aguilar D Allen LA Byun JJ Colvin MM et al 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2022) 79(17):e263–421. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.012

10.

McDonagh TA Metra M Adamo M Gardner RS Baumbach A Bohm M et al Corrigendum to: 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42(48):4901. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab670

11.

Youn J-C Kim D Cho JY Cho D-H Park SM Jung M-H et al Korean society of heart failure guidelines for the management of heart failure: treatment. Korean Circ J. (2023) 53(4):217–38. 10.4070/kcj.2023.0047

12.

van Veldhuisen DJ Cohen-Solal A Bohm M Anker SD Babalis D Roughton M et al Beta-blockade with nebivolol in elderly heart failure patients with impaired and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: data from SENIORS (study of effects of nebivolol intervention on outcomes and rehospitalization in seniors with heart failure). J Am Coll Cardiol. (2009) 53(23):2150–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.046

13.

Yamamoto K Origasa H Hori M Investigators JD . Effects of carvedilol on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Japanese diastolic heart failure study (J-DHF). Eur J Heart Fail. (2013) 15(1):110–8. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs141

14.

Cleland JGF Bunting KV Flather MD Altman DG Holmes J Coats AJS et al Beta-blockers for heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: an individual patient-level analysis of double-blind randomized trials. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39(1):26–35. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx564

15.

Kaddoura R Madurasinghe V Chapra A Abushanab D Al-Badriyeh D Patel A . Beta-blocker therapy in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (B-HFpEF): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2024) 49(3):102376. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2024.102376

16.

Kaddoura R Patel A . Revisiting beta-blocker therapy in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2023) 48(12):102015. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.102015

17.

Meyer M Lavallaz JDF Benson L Savarese G Dahlström U Lund LH . Association between β-blockers and outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: current insights from the SwedeHF registry. J Card Fail. (2021) 27(11):1165–74. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.04.015

18.

Arnold SV Silverman DN Gosch K Nassif ME Infeld M Litwin S et al Beta-blocker use and heart failure outcomes in mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. (2023) 11(8 Pt 1):893–900. 10.1016/j.jchf.2023.03.017

19.

Silverman DN Plante TB Infeld M Callas PW Juraschek SP Dougherty GB et al Association of β-blocker use with heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular disease mortality among patients with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction: a secondary analysis of the TOPCAT trial. JAMA Netw Open. (2019) 2(12):e1916598. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16598

20.

Solomon SD McMurray JJV Anand IS Ge J Lam CSP Maggioni AP et al Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. (2019) 381(17):1609–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1908655

21.

Anker SD Butler J Filippatos G Ferreira JP Bocchi E Bohm M et al Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385(16):1451–61. 10.1056/NEJMoa2107038

22.

Kim SH Yun SC Park JJ Lee SE Jeon ES Kim JJ et al Beta-blockers in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: results from the Korea acute heart failure (KorAHF) registry. Korean Circ J. (2019) 49(3):238–48. 10.4070/kcj.2018.0259

23.

Harada D Asanoi H Noto T Takagawa J . The impact of right ventricular dysfunction on the effectiveness of beta-blockers in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Cardiol. (2020) 76(4):325–34. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2020.05.001

24.

Cho G-Y Marwick TH Kim H-S Kim M-K Hong K-S Oh D-J . Global 2-dimensional strain as a new prognosticator in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2009) 54(7):618–24. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.061

25.

Kovacs A Olah A Lux A Matyas C Nemeth BT Kellermayer D et al Strain and strain rate by speckle-tracking echocardiography correlate with pressure-volume loop-derived contractility indices in a rat model of athlete’s heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2015) 308(7):H743–8. 10.1152/ajpheart.00828.2014

26.

Park JJ Park JB Park JH Cho GY . Global longitudinal strain to predict mortality in patients with acute heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 71(18):1947–57. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.064

27.

Kraigher-Krainer E Shah AM Gupta DK Santos A Claggett B Pieske B et al Impaired systolic function by strain imaging in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 63(5):447–56. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.052

28.

Park JJ Choi HM Hwang IC Park JB Park JH Cho GY . Myocardial strain for identification of beta-blocker responders in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2019) 32(11):1462–9.e8. 10.1016/j.echo.2019.06.017

29.

Packer M Fowler MB Roecker EB Coats AJ Katus HA Krum H et al Effect of carvedilol on the morbidity of patients with severe chronic heart failure: results of the carvedilol prospective randomized cumulative survival (COPERNICUS) study. Circulation. (2002) 106(17):2194–9. 10.1161/01.cir.0000035653.72855.bf

30.

Packer M Lukas MA Tenero DM Baidoo CA Greenberg BH Study G . Pharmacokinetic profile of controlled-release carvedilol in patients with left ventricular dysfunction associated with chronic heart failure or after myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. (2006) 98(7A):39l–45l. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.018

31.

Pieske B Tschöpe C De Boer RA Fraser AG Anker SD Donal E et al How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA–PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the heart failure association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. (2019) 40(40):3297–317. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz641

32.

Lang RM Badano LP Mor-Avi V Afilalo J Armstrong A Ernande L et al Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American society of echocardiography and the European association of cardiovascular imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2015) 16(3):233–71. 10.1093/ehjci/jev014

33.

Potter E Marwick TH . Assessment of left ventricular function by echocardiography: the case for routinely adding global longitudinal strain to ejection fraction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2018) 11(2 Pt 1):260–74. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.11.017

34.

Chung D Hong SW Lee J Chung JW Bang OY Kim GM et al Topographical association between left ventricular strain and brain lesions in patients with acute ischemic stroke and normal cardiac function. J Am Heart Assoc. (2023) 12(15):e029604. 10.1161/JAHA.123.029604

35.

Yusuf S Pfeffer MA Swedberg K Granger CB Held P McMurray JJ et al Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-preserved trial. Lancet. (2003) 362(9386):777–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7

36.

Cleland JG Tendera M Adamus J Freemantle N Polonski L Taylor J et al The perindopril in elderly people with chronic heart failure (PEP-CHF) study. Eur Heart J. (2006) 27(19):2338–45. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl250

37.

Pitt B Pfeffer MA Assmann SF Boineau R Anand IS Claggett B et al Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. (2014) 370(15):1383–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1313731

38.

Becher PM Fluschnik N Blankenberg S Westermann D . Challenging aspects of treatment strategies in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: “why did recent clinical trials fail?”. World J Cardiol. (2015) 7(9):544. 10.4330/wjc.v7.i9.544

39.

do Vale GT Ceron CS Gonzaga NA Simplicio JA Padovan JC . Three generations of beta-blockers: history, class differences and clinical applicability. Curr Hypertens Rev. (2019) 15(1):22–31. 10.2174/1573402114666180918102735

40.

Domagoj M Branka JZ Jelena M Davor M Duska G . Effects of carvedilol therapy in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction—results from the Croatian heart failure (CRO-HF) registry. Med Clin (Barc). (2019) 152(2):43–9. 10.1016/j.medcli.2018.02.011

41.

Bergstrom A Andersson B Edner M Nylander E Persson H Dahlstrom U . Effect of carvedilol on diastolic function in patients with diastolic heart failure and preserved systolic function. Results of the Swedish Doppler-echocardiographic study (SWEDIC). Eur J Heart Fail. (2004) 6(4):453–61. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.02.003

42.

Wernhart S Papathanasiou M Rassaf T Luedike P . The controversial role of beta-blockers in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Pharmacol Ther. (2023) 243:108356. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108356

43.

Yam FK Lew T Eraly SA Lin H-W Hirsch JD Devor M . Changes in medication regimen complexity and the risk for 90-day hospital readmission and/or emergency department visits in US veterans with heart failure. Res Social Adm Pharm. (2016) 12(5):713–21. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.10.004

44.

Park CS Park JJ Lee H-Y Kang S-M Yoo B-S Jeon E-S et al Clinical characteristics and outcome of immediate-release versus SLOW-release carvedilol in heart failure patient (SLOW-HF): a prospective randomized, open-label, multicenter study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. (2023) 37(3):529–37. 10.1007/s10557-021-07238-3

Summary

Keywords

beta-blocker, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, hypertension, sustained-release carvedilol, global longitudinal strain

Citation

Yoon M, Park S-J, Yoo B-S and Choi D-J (2024) The effect of sustained-release CARvedilol in patients with hypErtension and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial (CARE-preserved HF). Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1375003. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1375003

Received

23 January 2024

Accepted

15 April 2024

Published

26 April 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Francesco Gentile, Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies, Italy

Reviewed by

Sarawut Siwamogsatham, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand

Rasha Kaddoura, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Yoon, Park, Yoo and Choi.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Dong-Ju Choi djchoi@snubh.org

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.