Abstract

Post-COVID new-onset hypertension (PCNH) is an increasingly reported complication among COVID-19 survivors. PCNH can emerge up to 12 months postinfection, with elevated risks observed among older patients, particularly those who experienced severe COVID-19, and among females, implicating the possibility of age and hormonal influence. Leading theories converge on enduring dysregulation of the angiotensin pathway and endothelial dysfunction. In addition to renin–angiotensin alterations, sustained inflammation, lung vascular damage, deconditioning, and mental health decline may also impact the likelihood of PCNH. Conventional renin–angiotensin system (RAS) antagonists may help improve pathway distortions, while novel anti-inflammatory agents and recombinant ACE2 biologics can help mitigate endothelial injury to alleviate cardiovascular burden. This review highlights the multifaceted mechanisms driving PCNH and the need to elucidate timing, predictors, pathophysiology, and tailored interventions to address this parallel pandemic among COVID-19 survivors.

1 Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on public health, causing widespread physical and psychological consequences. With over 6.5 million deaths worldwide and immediate effects on different systems of the human body, the pandemic has raised major concerns globally (1). More recently, as a result of worldwide vaccination and a substantial decrease in the mortality rate, researchers are working to improve the understanding of the potential long-term health effects on survivors.

One area of growing concern is the development of post-COVID-19 new-onset hypertension (PCNH) in individuals who have recovered from COVID-19. Initial evidence suggests that even after complete remission from COVID-19 disease, some patients may be diagnosed with hypertension for the first time (2, 3) or experience a worsening of preexisting hypertension (4). Studies reported a significant prevalence of PCNH in patients who recovered from COVID-19. Additionally, we observed an increase in cardiovascular mortality associated with hypertensive disease in the first year of the pandemic (5, 6).

Understanding the mechanisms underlying COVID-19-induced hypertension is crucial for effective management and treatment strategies. In this review, we aim to explore the current literature surrounding the development of hypertension following COVID-19 infection, including potential mechanisms, risk factors, clinical implications, and therapeutic interventions. By understanding this emerging issue, we can better support the long-term health of COVID-19 survivors, particularly from a hypertension standpoint.

2 Method and search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive literature search using PubMed/MEDLINE and Embase databases from December 2019 to December 2024 to capture all relevant publications since the emergence of COVID-19.

2.1 Search strategy and terms

The search was performed using various combinations of the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords: “COVID-19,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “coronavirus,” “hypertension,” “blood pressure,” “new-onset hypertension,” “post-COVID,” “long COVID,” “post-acute COVID-19 syndrome,” and “COVID-19 sequelae.” Additional search terms included “post-COVID new-onset hypertension (PCNH),” “cardiovascular complications,” “renin-angiotensin system,” “ACE2,” “endothelial dysfunction,” and “systemic inflammation.” Boolean operators (AND, OR) and truncation symbols were used to capture variations in terminology and spelling.

2.2 Study selection criteria

We included peer-reviewed original research articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and case series published in English that reported on hypertension development following COVID-19 infection. Studies were included if they (1) involved human subjects with confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis, (2) reported new-onset hypertension or blood pressure changes postinfection, (3) had follow-up periods of at least 30 days post-acute infection, and (4) provided quantitative data on prevalence, incidence, or risk factors. We excluded case reports with fewer than 10 patients, conference abstracts without full-text availability, preprints without peer review, and studies focusing solely on preexisting hypertension management during acute COVID-19.

2.3 Additional sources

We supplemented our database searches with manual screening of reference lists from included studies and relevant review articles. We also searched clinical trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) for ongoing studies. Gray literature was examined through Google Scholar and relevant professional organization websites to identify additional reports and guidelines.

3 Prevalence of post-COVID hypertension

The emergence of post-COVID-19 hypertension represents one of the most compelling cardiovascular sequelae of the pandemic. Multiple large-scale studies have demonstrated a consistent pattern of increased hypertension risk following COVID-19 infection, with evidence spanning millions of patients worldwide.

Meta-analyses encompassing over 19 million individuals reveal that COVID-19 survivors face a 65%–70% increased risk of developing new-onset hypertension compared with uninfected controls (7). The clinical magnitude of this phenomenon is substantial, with studies reporting PCNH rates ranging from 10.85% in non-hospitalized patients to 20.6% in hospitalized COVID-19 survivors within 6 months of recovery (8). Recent longitudinal population-based studies demonstrate a dramatic temporal increase in hypertension incidence during the pandemic years, with rates more than doubling from pre-pandemic levels and continuing to rise through 2023 (13).

The temporal dynamics of PCNH reveal additional complexity, with peak risk occurring within 30 days postinfection, though some studies suggest this risk may normalize by 91–120 days (9). Beyond new-onset cases, COVID-19 appears to exacerbate preexisting hypertension, with over half of previously hypertensive patients experiencing worsened blood pressure control post-recovery (4). Healthcare practitioners globally report increased diagnoses of new-onset hypertension in COVID-19 survivors, with some studies documenting PCNH in up to one-third of patients at 1-year follow-up (10, 11).

Collectively, these findings establish PCNH as a significant and persistent cardiovascular legacy of COVID-19, affecting millions of survivors worldwide and reshaping our understanding of post-viral cardiovascular disease. Detailed study characteristics and findings are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Study | Population | Sample size | Follow-up | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delilac et al. (4) | Hypertensive COVID patients | 32 | NR | Worsened hypertension control: 17/32 (53%) showed worsened BP control post-COVID |

| Zuin et al. (7) | Meta-analysis, five population studies | >19 million | 7 months | New-onset hypertension: 12.7/1,000 COVID vs. 8.17/1,000 controls (HR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.46–1.97, p < 0.0001) |

| Zhang et al. (8) | COVID-19 vs. influenza patients | NR | 6 months | New-onset hypertension: 20.6% hospitalized, 10.85% non-hospitalized COVID patients; higher than influenza |

| Chevinski et al. (9) | COVID-19 survivors | NR | 30–120 days | New-onset hypertension: OR 2.3 at 30 days, returned to baseline by 91–120 days |

| Vyas et al. (10) | COVID-19 survivors | 248 | 1 year | New-onset hypertension: 32.3% (n = 80) developed |

| Krishnakumar et al. (11) | Healthcare practitioner survey | NR | NR | New-onset hypertension: 66% of practitioners reported increased cases in COVID survivors |

| Angeli et al. (12) | Pooled analysis, four studies | NR | NR | New-onset hypertension: 65% increased risk (OR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.34–2.05); 9% COVID vs. 5% controls |

| Trimarco et al. (13) | Longitudinal cohort | >200,000 | 7 years | New-onset hypertension incidence: 2.11/100 person-years (2017–2019) → 5.20/100 (2020–2022) → 6.76/100 (2023) |

| Kazemi et al. (14) | Hospitalized COVID-19 patients, Iran | 690 | During hospitalization | New-onset hypertension: 67 patients (10%) |

| Azami et al. (15) | Non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients, Iran | 5,355 | 12.5 ± 0.4 months | New-onset hypertension: 408 patients (17%) Total new/exacerbated hypertension: 864 patients (16%) |

| Daugherty et al. (16) | UnitedHealth Group, adults 18–65 | 193,113 | 4 months | New-onset hypertension: HR 1.56 (95% CI: 1.48–1.65), RD 1.10 (0.88–1.32) per 100 people vs. 2020 controls |

| Abdulan et al. (17) | Post-COVID patients, Romania | 70 | 30 days | Worsened hypertension: Pre-COVID 68.57% → post-COVID 90% (p = 0.005) Risk factors: age, female gender, elevated BMI |

| Cohen et al. (18) | Medicare Advantage adults ≥65 years | 87,337 COVID+ matched pairs | 120 days post-acute | New-onset hypertension: RD 4.43 (2.27–6.37) per 100 patients vs. 2020 controls; HR 1.76 (1.58–1.97) |

| Mizrahi et al. (19) | Israeli healthcare members, mild COVID-19 | 299,870 matched pairs | 30–360 days | New-onset hypertension: HR 1.16 (1.05–1.27), RD 8.3 (2.4–14.1) per 10,000 patients in late period (180–360 days) |

Studies reporting post-COVID-19 new-onset hypertension.

BP, blood pressure; NR, not reported; RD, risk difference.

4 Contributing risk factors

The risk factors for the development of new-onset hypertension are not yet fully understood; however, meta-analysis has indicated a higher prevalence among women (p = 0.03) (7). This finding contrasts with the higher number of recorded COVID-19 cases and hospital admissions in men (20). Moreover, older age (p = 0.001) and history of cancer (p < 0.0001) were significantly associated with a higher risk of PCNH. Al-Aly et al. and Tisler et al. reported a significantly increased risk of hypertension in hospitalized and ICU-admitted patients compared with the non-hospitalized subjects. These results can indirectly indicate the role of the severity of the infection in the increased risk of PCNH (3, 21). On the other hand, there are conflicting data regarding the relationship between PCNH and some of the biomarkers of severity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, including variations in cycle threshold (CT) scores and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (10, 22).

5 Probable engaged pathways

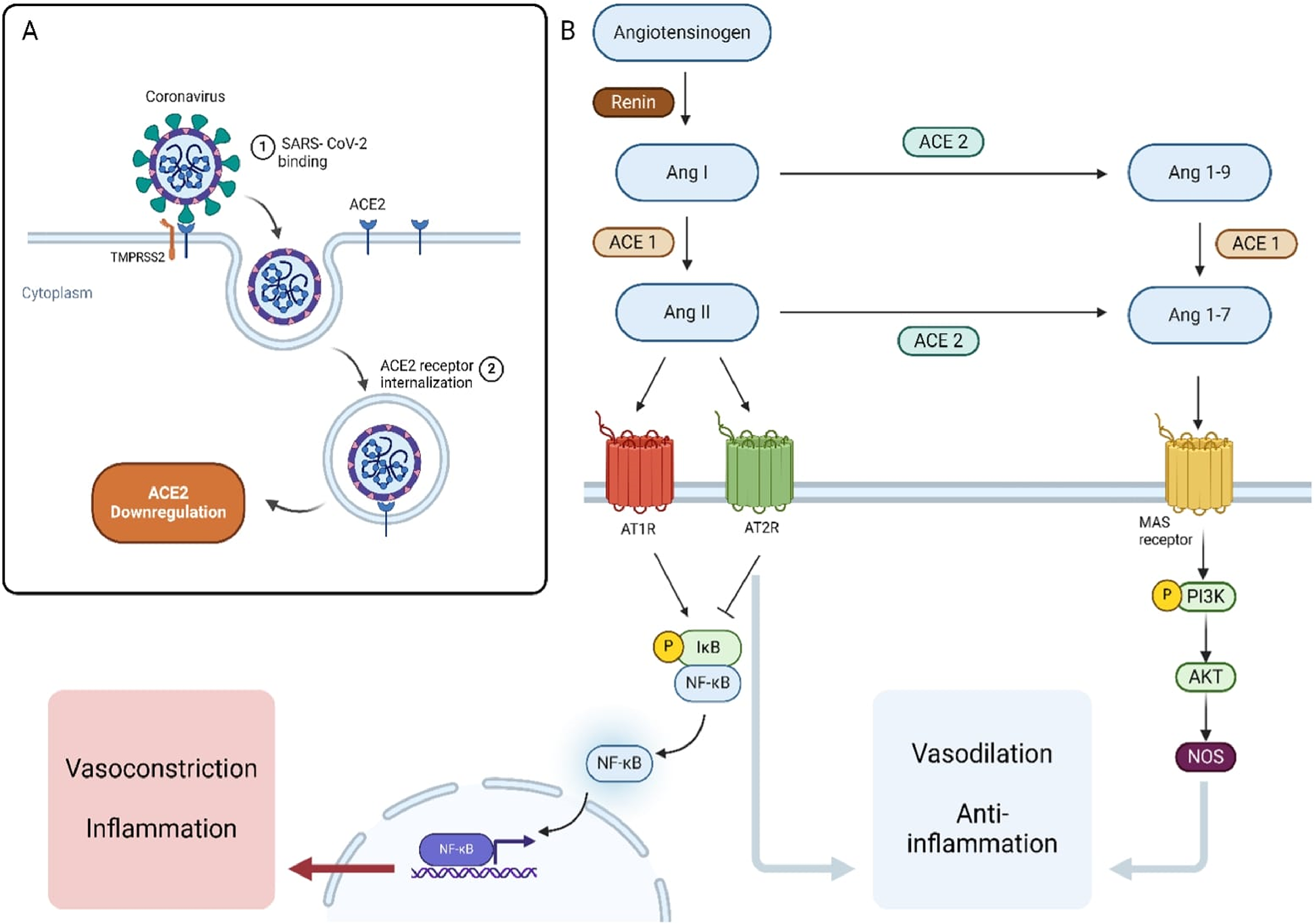

SARS-CoV-2 enters the cell by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor using the spike (S) protein. The membrane fusion requires the S protein to bind to both ACE2 and TMPRSS2 (23). Co-expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 is particularly high in four types of cells: type II pneumocytes, ileal absorptive enterocytes, endothelial smooth muscle cells, and nasal goblet secretory cells (24). These cells serve as primary targets for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Once the virus enters the cell, it exerts various effects in two major pathways discussed in more detail below (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Interaction with the Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS) and Its Downstream Effects. (A) SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2 receptor on the host cell surface, leading to receptor internalization and downregulation of ACE2 expression. (B) The RAS pathway involves the conversion of angiotensinogen to Angiotensin I (Ang I) by renin, and then to Angiotensin II (Ang II) by ACE1. Ang II can bind to AT1R, promoting vasoconstriction and inflammation via the NF-κB pathway. Alternatively, Ang II can be converted by ACE2 into Ang 1–7, which acts through the MAS receptor to promote vasodilation and anti-inflammatory effects through the PI3K/AKT/NOS signaling pathway. ACE2 also converts Ang I to Ang 1-9, which can be further processed by ACE1.

5.1 ACE pathway

5.1.1 ACE1 and ACE2 balance

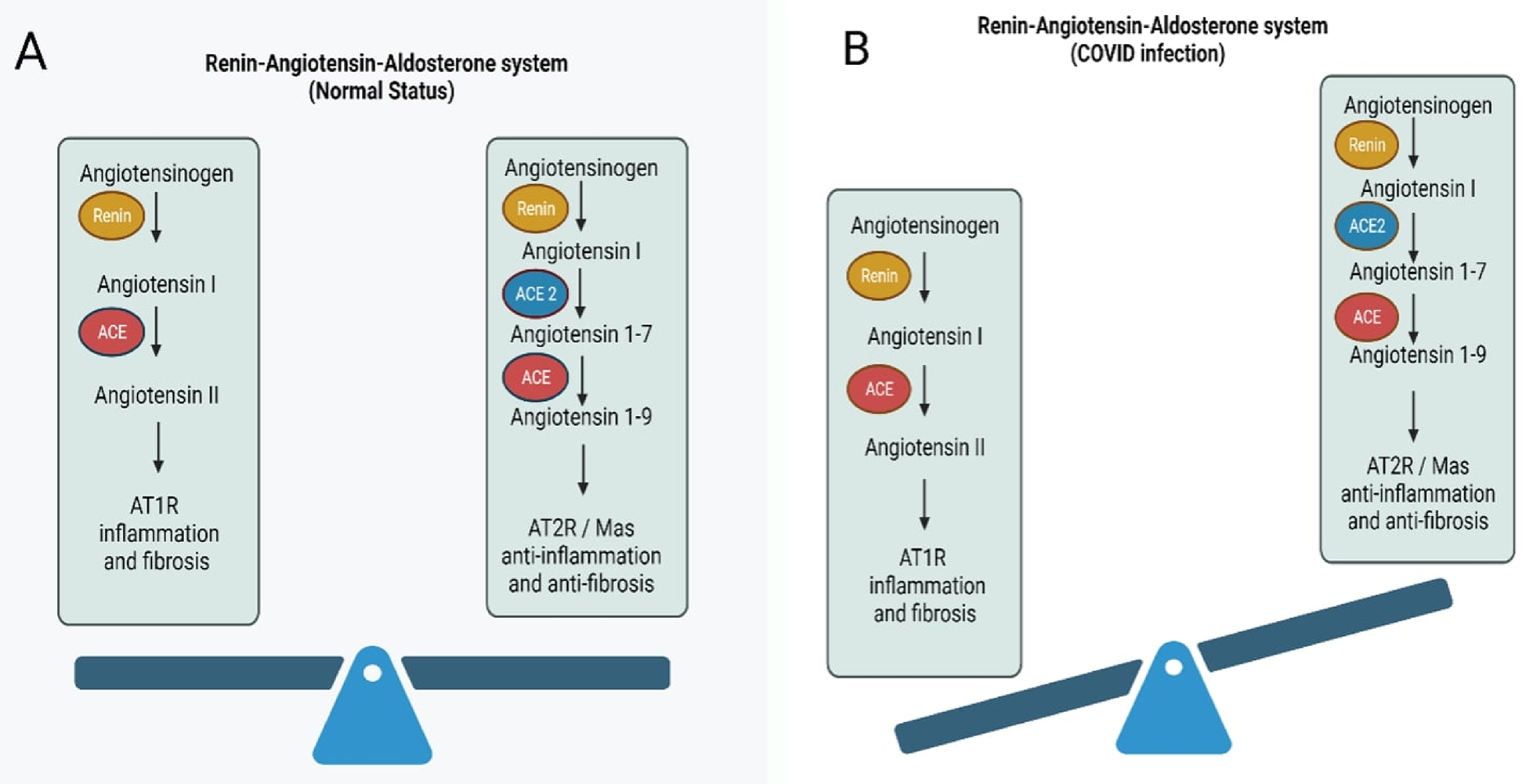

ACE1 converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II, driving vasoconstriction and increasing blood pressure (25, 26). Its overactivity also induces inflammation and fibrosis via increasing the reactive oxygen species (27, 28). In contrast, ACE2 inactivates angiotensin II into anti-inflammatory, vasodilatory angiotensin 1–7 to reduce blood pressure (29). Overall, balanced ACE1/ACE2 regulation of angiotensin tone is central for blood pressure regulation. Advancing age may shift the ACE2-mediated homeostasis toward ACE1-driven inflammation and hypertension. Similarly, SARS-CoV-2 downregulates ACE2 activity through viral binding and internalization (30), shifting the balance toward dysregulated ACE1/angiotensin II signaling, vasoconstriction, and fibrosis (31, 32) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Disruption of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) During COVID-19 Infection. (A) Under normal conditions, the RAAS maintains a balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signals. (B) During COVID-19 infection, ACE2 is downregulated following SARS-CoV-2 binding, reducing the conversion of Angiotensin I and II to their protective forms.

5.1.2 Age-related disparity in ACE1 and ACE2 expression

Age alters the ACE1 and ACE2 expression in tissues (33). Younger children have lower ACE2 expression in lung alveolar epithelium compared with older children and adults, which may explain lower rates of severe SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infections (34). However, from a vascular standpoint, ACE2 expression decreases with age. As mentioned earlier, the dominance of ACE1 signaling in older adults can lead to dysregulated inflammation and fibrosis in blood vessels, potentially contributing to higher hypertension risk (35). This provides a potential explanation for advanced age being a major risk factor for PCNH. As noted earlier, SARS-CoV-2 infection reduces endothelial ACE2 expression in blood vessels, which can exacerbate ACE1/ACE2 imbalance and shift the pathway toward further inflammation and fibrosis.

5.1.3 Gender-related disparity in ACE1 and ACE2 expression

Females also have higher ACE2 expression compared with males. This is partly attributed to estrogen-enhancing ACE2 levels in various tissues, including lung alveolar cells. Additionally, the ACE2 gene is located on the X chromosome (36). While X chromosome inactivation generally silences most female genes, the process is incomplete for certain regions such as ACE2 (37). This overexpression helps explain the lower hypertension prevalence in females of fertile age. As noted by Gillis et al. (38), hypertension in the general population is more common in men. However, this gap narrows with age, likely due to declining ACE2 expression (39). Moreover, postmenopausal hypertension risk increases with dramatically reduced estrogen (39, 40).

Interestingly, despite higher protective ACE2 levels in females and more COVID-19 cases in men, post-COVID hypertension is more prevalent among women. Women also make up the majority of the COVID-19 long haulers (41). This paradox highlights the likely role of disproportionate immune activation and inflammation in driving this outcome in females (42). While women tend to have greater baseline ACE2 expression across age and race subgroups compared with males, SARS-CoV-2 infection may trigger a more drastic shift toward ACE1 dominance and away from vasoprotective ACE2 signaling. The resulting imbalance could initiate hypertension development. More severe ACE1/ACE2 distortion in infected women vs. men could explain the elevated risk of vascular complications such as hypertension. Additional research investigating sex differences in COVID-19 cardiovascular sequelae is still needed to unravel these complex mechanisms. Determining the contribution of both inflammation and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) signaling dysregulation specifically in females will provide critical insights into the unexpectedly increased susceptibility of women to PCNH.

5.1.4 Soluble ACE2 and autoantibodies against the soluble ACE2

ACE2 is a transmembrane protein that is originally located in the membrane of various cells. Studies have shown that several enzymes such as ADAM17 and TMPRSS2 can cleave the membrane-binding domain of ACE2, causing it to be released into the bloodstream. This form of ACE2 is known as soluble ACE2 (sACE2) (43).

Many observational studies have reported a positive association between the level of sACE2 in the blood and the severity of COVID-19 disease (44–46). Of note, sACE2 cannot inactivate angiotensin II (47). However, sACE2 can still serve as a receptor for SARS-CoV-2 (48). Interestingly, SARS-CoV-2 itself mediates ACE2 shedding and increases the sACE2 level in patients' serum (49). Therefore, we can assume that sACE2 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 spreading throughout the body and deteriorates the dysregulated inflammation caused by the virus.

On the other hand, studies have shown that some patients produce autoantibodies against soluble ACE2 (sACE2) after recovering from COVID-19. These autoantibodies can interfere with the function of both ACE2 and sACE2, which can lead to the overactivation of the angiotensin II/AT1 receptor pathway (50). This, in turn, could be a potential mechanism for PCNH. More research is needed to measure the levels of these autoantibodies in patients with and without PCNH to better understand the underlying mechanisms.

5.2 Inflammation

The role of inflammation in hypertension has been well-established in recent years (51–53). A recent study by Eberhardt et al. (54) on autopsies of eight patients who died as a result of severe COVID-19 infection demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 has a tropism for vascular lesion macrophages and foam cells in the coronary vasculature, suggesting the role of the virus in triggering inflammation, particularly in the previously damaged areas. It is worth noting that macrophages and foam cells have a very low expression of ACE 2 and TMPRSS2. Therefore, SARS-CoV-2 infects these cells with a specific entry mechanism using a particular type of cell surface glucose-related protein (55).

Furthermore, in another study conducted by Chen et al. (22), patients with post-COVID new-onset hypertension exhibited significantly higher levels of troponin I (median interquartile 22, 95% CI: 18.20–30.00 vs. 3.86, 95% CI: 2.49–5.15) and procalcitonin (median interquartile 82, 95% CI: 53–430 vs. 49, 95% CI: 28–73), suggesting a potential inflammatory process. According to studies, the SARS-CoV-2 N-protein can activate NLRP3 inflammasomes, initiating an inflammatory cascade that plays a protective role against viral spread in the early stages. However, prolonged dysregulation of this pathway can damage the vasculature and lead to hypertension (56).

On the other hand, another major inflammatory pathway is primarily led by type I interferons (IFNs) which is inhibited by SARS-CoV-2. Studies have suggested that loss-of-function mutations in type I IFN or autoantibodies against type I IFN are associated with severe COVID-19 infections and increased mortality (57, 58). The type I interferon pathway appears to have less tendency toward prolonged hyperinflammation and subsequent hypertension (59). Therefore, we can infer that there is another balanced system between these two inflammatory pathways in the body, and dysregulation in either can shift toward hyperinflammation and hypertension.

Studies also demonstrated the crucial role of inflammation in the pulmonary vasculature in patients with COVID-19 infection (60). High levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines along with uncontrolled complement activation can lead to activation of coagulation pathways and microthrombi formation (61), all are correlated with the emergence of pulmonary hypertension in patients with COVID-19 infection (62, 63).

6 Genetic aspects of hypertension and COVID

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and Mendelian randomization (MR) methods elucidated the shared genetic structure between hypertension and COVID-19 infection (57, 64). Baranova et al. (57) analyzed the genome of hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 infection and showed that patients with genetic liability to hypertension may have an increased risk of severe COVID-19 infection (OR = 1.05, p = 0.03. This may or may not be aligned to PCNH, given that many such patients may have been diagnosed with hypertension earlier. Nevertheless, the presence of a shared genetic structure between hypertension and severe COVID-19 enhances the likelihood that genetic factors may potentiate the development of PCNH in predisposed individuals. This study also highlighted a shared genetic structure linking the loci related to the immune system and blood group proteins to genetic susceptibility to COVID-19 infection. In other words, people harboring some variants in the genes related to the immune system and blood groups may experience more severe COVID-19 infection.

Additionally, another Mendelian randomization study found that genetic variants associated with COVID-19 at genome-wide significance were also associated with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, using the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) and MR-Egger methods (OR = 1.11, p = 0.001) (58), suggesting a shared genetic architecture between hypertension and genetic liability to COVID-19 infection.

In support of this, Yang et al. (65) characterized the genetic landscape of ACE2—the receptor for SARS-CoV-2—and identified rare coding variants and regulatory polymorphisms that differ across sex and ancestry. Some of these variants may impair ACE2 expression or function, exacerbating RAS imbalance during infection. This functional depletion of ACE2 could tip the physiological axis toward vasoconstriction, inflammation, and hypertension, highlighting a plausible mechanism through which genetically susceptible individuals may develop post-COVID new-onset hypertension (PCNH).

Similarly, Faustine et al. (66) demonstrated that specific genotypes in the ACE (rs4331) and ACE2 (rs2074192) genes were associated with increased COVID-19 severity in patients with hypertension. Males with the GG (ACE) and TT (ACE2) genotypes experienced the highest rates of moderate-to-severe disease, suggesting that individuals with certain ACE/ACE2 polymorphisms may not only be at greater risk of severe infection but may also be more vulnerable to persistent RAS dysregulation and the development of PCNH.

Based on another research by Cheng et al., COVID-19 and hypertension genetic pathways can disproportionately affect females through the SPEG gene variant rs12474050. This genetic variant is associated with both severe COVID-19 outcomes and hypertension in women, suggesting that females may be at higher risk for developing PCNH. The study reveals that SPEG expression is naturally higher in female heart tissue and becomes further upregulated during SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly in cardiomyocytes, which may explain why women experience more severe cardiovascular complications from COVID-19. This sex-specific genetic vulnerability could contribute to the observed increased incidence of new-onset hypertension in female COVID-19 patients compared with males (67).

7 Other potential causes of post-COVID new-onset hypertension

7.1 Obesity and metabolic syndrome

Obesity and related comorbidities are increasingly being viewed as a pandemic. During the COVID-19 outbreak, statistical analyses have indicated a substantial rise in the prevalence of obesity. Restrepo studied the average BMI of US citizens in 2020, compared with pre-pandemic data (68), the average BMI in US citizens increased by +0.6 (p < 0.05), and the obesity prevalence rates also increased by 3% (p < 0.05) (69). Aminian et al. (70) performed a study on 2,839 patients recovering from COVID-19 and found a significantly increased risk of cardiac (HR: 1.87, 95% confidence interval or CI: 1.41–2.48, p < 0.001) and vascular (HR: 2.43, 95% CI: 1.38–4.27, p = 0.13) complications among participants with a BMI over 35. This highlights the role of both preexisting and post-COVID-19 obesity in elevating the risk of PCNH.

7.2 Corticosteroids

This class of medications was widely used during the COVID-19 pandemic for both hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients (71). Although valid guidelines have approved their potential role in the outcome of critically ill patients (72, 73), studies show that these medications were overused in many countries and health systems (71). Hypertension accounts for one of the side effects of corticosteroid overuse among patients who recovered from a previous COVID-19 episode (64, 65). Corticosteroids can increase blood pressure by increasing the amount of salt and water that the body retains, although these effects may be transient. Corticosteroids can also reduce the production of nitric oxide, a molecule that contributes to vasodilation (10, 74, 75).

7.3 Physical inactivity

Physical inactivity is a well-known risk factor for hypertension (HR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.66) (76), and it has been more common among people during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (77). Analyses demonstrate that a decrease in physical activity during the pandemic involved all ages including the younger population (78). Physical inactivity can lead to weight gain, which is also another major risk factor for hypertension.

7.4 Closer monitoring postinfection

Greater engagement with the healthcare system among COVID-19 survivors may lead to the identification of previously undiagnosed conditions, such as hypertension (79).

8 Discussion

Post-COVID new-onset hypertension is a well-documented condition, reported in both hospital-based and population-based studies (77). In this review, we summarize the proposed mechanisms underlying PCNH, including the direct effects of the virus—primarily through ACE receptors and alterations in the renin–angiotensin system—as well as the roles of inflammation and endothelial injury. We also explore the contribution of genetic predisposition and the shared genetic architecture between severe COVID-19 and hypertension.

Recognizing the PCNH as a distinct clinical entity carries significant implications beyond academic interest. While the immediate management of elevated blood pressure might appear similar regardless of etiology, identifying PCNH enables targeted screening of COVID-19 survivors, particularly among traditionally low-risk populations such as younger females without conventional cardiovascular risk factors. Given the unprecedented scale of COVID-19 infection globally, even a modest increased risk of PCNH could translate into a substantial population-level burden of cardiovascular disease, particularly considering the younger age of onset compared with essential hypertension. This understanding should inform healthcare resource planning, as systems need to prepare for an increased burden of hypertension-related complications in previously low-risk populations.

Therefore, while we continue to investigate the exact mechanisms and optimal management strategies, the recognition and study of PCNH remain crucial for both individual patient care and broader public health preparedness strategies in the post-COVID era.

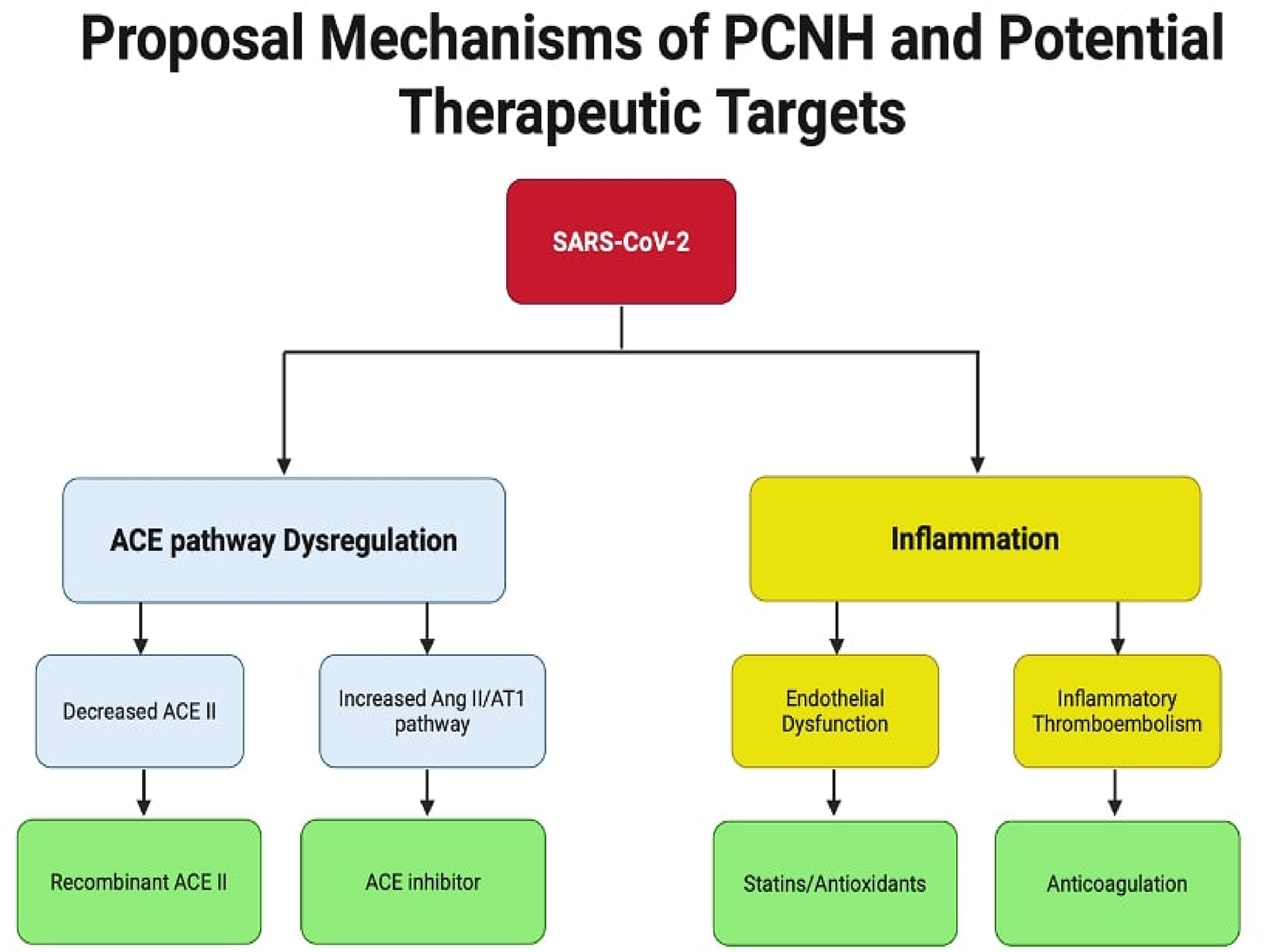

Despite the growing evidence supporting an association between COVID-19 and PCNH, several critical knowledge gaps warrant further investigation. The long-term natural history of PCNH remains poorly understood, while most current studies are limited to 6–12 months of follow-up. Moreover, while several mechanisms have been proposed, the relative contribution of each pathway particularly the ACE2 regulation, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction to PCNH development remains unclear. The paradoxical higher prevalence in women despite their typically higher ACE2 expression requires more in-depth mechanistic investigation. Figure 3 presented potential therapeutic targets.

Figure 3

Summary of potential mechanisms of PCNH and therapeutic targets. Two main pathways contribute to post-COVID-19 new onset hypertension: ACE pathway dysregulation and inflammation. The ACE pathway leads to hypertension through either decreased ACE2 levels via receptor internalization or overactivation of the Ang II/AT1R pathway, ultimately causing fibrosis and inflammation. The inflammation pathway results directly from interleukin release and can also be triggered by AT1R pathway activation. Systemic inflammation promotes both endothelial dysfunction and hypercoagulable states, contributing to cardiovascular complications. ACE II, angiotension converting enzyme II; Ang II, angiotensin II; AT1R, angiotensin II type I receptor.

Additionally, standardized protocols for PCNH screening and early detection are lacking, as are predictive biomarkers for identifying high-risk patients. Future research priorities should include large-scale prospective cohort studies with extended follow-up periods, standardization of PCNH definition and diagnostic criteria, investigation of sex-specific mechanisms, and development of predictive models for early identification.

Furthermore, the establishment of large-scale, multicenter registries could help address many of these knowledge gaps while providing valuable data for clinical decision-making in the post-COVID era.

8.1 Study limitations and evidence quality

Current evidence is limited by heterogeneous PCNH definitions, variable follow-up periods, and potential confounding from lifestyle changes and increased healthcare utilization post-COVID. Most studies focus on hospitalized patients, potentially overestimating severity. Standardized diagnostic criteria and longer-term prospective studies with community-based populations are needed to better characterize this emerging condition.

9 Conclusion

In this review, we examined the prevalence, potential mechanisms, and public health significance of PCNH. Studies have linked COVID-19 infection with the development of hypertension as well as the worsening of preexisting hypertension. Proposed causal mechanisms for this link include dysregulated ACE1/ACE2 balance, inflammation, soluble ACE2 autoantibodies, and shared genetic susceptibility between the conditions. Other potential causes of PCNH, such as stress, anxiety, obesity, metabolic syndrome, physical inactivity, and corticosteroid side effects, have also been implicated. The long-term progression, natural course, and optimal management of PCNH, beyond conventional therapies, are not yet well understood and warrant further investigations.

Statements

Author contributions

AT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DA: Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SN: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. DG: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. GH-B: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

CDC. COVID-19 mortality overview. Available online at:https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/mortality-overview.htm(Accessed September 12, 2023).

2.

Akpek M . Does COVID-19 cause hypertension?Angiology. (2022) 73(7):682–7. 10.1177/00033197211053903

3.

Al-Aly Z Bowe B Xie Y . Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. (2022) 28(7):1461–7. 10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0

4.

Delalic D Jug J Prkacin I . Arterial hypertension following COVID-19: a retrospective study of patients in a central European tertiary care center. Acta Clin Croat. (2022) 61(Suppl 1):23–7. 10.20471/acc.2022.61.s1.03

5.

Kobo O Abramov D Fudim M Sharma G Bang V Deshpande A et al Has the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic reversed the trends in CV mortality between 1999 and 2019 in the United States? Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. (2023) 9(4):367–76. 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcac080

6.

Chaganty SS Abramov D Van Spall HGC Bullock-Palmer RP Vassiliou V Myint PK et al Rural and urban disparities in cardiovascular disease-related mortality in the USA over 20 years; have the trends been reversed by COVID-19? Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev. (2023) 19:200202. 10.1016/j.ijcrp.2023.200202

7.

Zuin M Rigatelli G Bilato C Pasquetto G Mazza A . Risk of incident new-onset arterial hypertension after COVID-19 recovery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. (2023) 30(3):227–33. 10.1007/s40292-023-00574-5

8.

Zhang V Fisher M Hou W Zhang L Duong TQ . Incidence of new-onset hypertension post-COVID-19: comparison with influenza. Hypertension. (2023) 80(10):2135–48. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.123.21174

9.

Chevinsky JR Tao G Lavery AM Kukielka EA Click ES Malec D et al Late conditions diagnosed 1-4 months following an initial coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) encounter: a matched-cohort study using inpatient and outpatient administrative data-United States, 1 March–30 June 2020. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 73(Suppl 1):S5–16. 10.1093/cid/ciab338

10.

Vyas P Joshi D Sharma V Parmar M Vadodariya J Patel K et al Incidence and predictors of development of new onset hypertension post COVID-19 disease. Indian Heart J. (2023) 75(5):347–51. 10.1016/j.ihj.2023.06.002

11.

Krishnakumar B Christopher J Prasobh PS Godbole S Mehrotra A Singhal A et al Resurgence of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases in patients recovered from COVID-19: an Indian perspective. J Family Med Prim Care. (2022) 11(6):2589–96. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_973_21

12.

Angeli F Zappa M Verdecchia P . Global burden of new-onset hypertension associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Eur J Intern Med. (2024) 119:31–3. 10.1016/j.ejim.2023.10.016

13.

Trimarco V Izzo R Pacella D Trama U Manzi MV Lombardi A et al Incidence of new-onset hypertension before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic: a 7-year longitudinal cohort study in a large population. BMC Med. (2024) 22(1):127. 10.1186/s12916-024-03328-9

14.

Kazemi E Daliri S Chaman R Rohani-Rasaf M Binesh E Sheibani H . Cardiovascular disease development in COVID-19 patients admitted to a tertiary medical centre in Iran. Br J Cardiol. (2024) 31(2):26. 10.5837/bjc.2024.026

15.

Azami P Vafa RG Heydarzadeh R Sadeghi M Amiri F Azadian A et al Evaluation of blood pressure variation in recovered COVID-19 patients at one-year follow-up: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2024) 24(1):240. 10.1186/s12872-024-03916-w

16.

Daugherty SE Guo Y Heath K Dasmarinas MC Jubilo KG Samranvedhya J et al Risk of clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: retrospective cohort study. Br Med J. (2021) 373:n1098. 10.1136/bmj.n1098

17.

Abdulan IM Feller V Oancea A Mastaleru A Alexa AI Negru R et al Evolution of cardiovascular risk factors in post-COVID patients. J Clin Med. (2023) 12(20):6538. 10.3390/jcm12206538

18.

Cohen K Ren S Heath K Dasmarinas MC Jubilo KG Guo Y et al Risk of persistent and new clinical sequelae among adults aged 65 years and older during the post-acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: retrospective cohort study. Br Med J. (2022) 376:e068414. 10.1136/bmj-2021-068414

19.

Mizrahi B Sudry T Flaks-Manov N Yehezkelli Y Kalkstein N Akiva P et al Long COVID outcomes at one year after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: nationwide cohort study. Br Med J. (2023) 380:e072529. 10.1136/bmj-2022-072529

20.

Abate BB Kassie AM Kassaw MW Aragie TG Masresha SA . Sex difference in coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2020) 10(10):e040129. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040129

21.

Tisler A Stirrup O Pisarev H Kalda R Meister T Suija K et al Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 among hospitalized patients in Estonia: nationwide matched cohort study. PLoS One. (2022) 17(11):e0278057. 10.1371/journal.pone.0278057

22.

Chen G Li X Gong Z Xia H Wang Y Wang X et al Hypertension as a sequela in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. PLoS One. (2021) 16(4):e0250815. 10.1371/journal.pone.0250815

23.

Amraei R Rahimi N . COVID-19, renin-angiotensin system and endothelial dysfunction. Cells. (2020) 9(7):1652. 10.3390/cells9071652

24.

Ziegler CGK Allon SJ Nyquist SK Mbano IM Miao VN Tzouanas CN et al SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. (2020) 181(5):1016–35.e19. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035

25.

Lanza K Perez LG Costa LB Cordeiro TM Palmeira VA Ribeiro VT et al COVID-19: the renin-angiotensin system imbalance hypothesis. Clin Sci. (2020) 134(11):1259–64. 10.1042/CS20200492

26.

Kreutz R Algharably EAE Azizi M Dobrowolski P Guzik T Januszewicz A et al Hypertension, the renin-angiotensin system, and the risk of lower respiratory tract infections and lung injury: implications for COVID-19. Cardiovasc Res. (2020) 116(10):1688–99. 10.1093/cvr/cvaa097

27.

Savoia C Volpe M Kreutz R . Hypertension, a moving target in COVID-19: current views and perspectives. Circ Res. (2021) 128(7):1062–79. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318054

28.

Santos RA Brosnihan KB Chappell MC Pesquero J Chernicky CL Greene LJ et al Converting enzyme activity and angiotensin metabolism in the dog brainstem. Hypertension. (1988) 11(2 Pt 2):I153–7. 10.1161/01.HYP.11.2_Pt_2.I153

29.

Sharifkashani S Bafrani MA Khaboushan AS Pirzadeh M Kheirandish A Yavarpour Bali H et al Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor and SARS-CoV-2: potential therapeutic targeting. Eur J Pharmacol. (2020) 884:173455. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173455

30.

Hoffmann M Kleine-Weber H Schroeder S Kruger N Herrler T Erichsen S et al SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. (2020) 181(2):271–80.e8. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052

31.

Sparks MA South AM Badley AD Baker-Smith CM Batlle D Bozkurt B et al Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, COVID-19, and the renin-angiotensin system: pressing needs and best research practices. Hypertension. (2020) 76(5):1350–67. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15948

32.

Datta PK Liu F Fischer T Rappaport J Qin X . SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and research gaps: understanding SARS-CoV-2 interaction with the ACE2 receptor and implications for therapy. Theranostics. (2020) 10(16):7448–64. 10.7150/thno.48076

33.

Lee IT Nakayama T Wu CT Goltsev Y Jiang S Gall PA et al ACE2 localizes to the respiratory cilia and is not increased by ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Nat Commun. (2020) 11(1):5453. 10.1038/s41467-020-19145-6

34.

Silva MG Falcoff NL Corradi GR Di Camillo N Seguel RF Tabaj GC et al Effect of age on human ACE2 and ACE2-expressing alveolar type II cells levels. Pediatr Res. (2023) 93(4):948–52. 10.1038/s41390-022-02163-z

35.

AlGhatrif M Tanaka T Moore AZ Bandinelli S Lakatta EG Ferrucci L . Age-associated difference in circulating ACE2, the gateway for SARS-COV-2, in humans: results from the InCHIANTI study. Geroscience. (2021) 43(2):619–27. 10.1007/s11357-020-00314-w

36.

Bukowska A Spiller L Wolke C Lendeckel U Weinert S Hoffmann J et al Protective regulation of the ACE2/ACE gene expression by estrogen in human atrial tissue from elderly men. Exp Biol Med. (2017) 242(14):1412–23. 10.1177/1535370217718808

37.

Tukiainen T Villani AC Yen A Rivas MA Marshall JL Satija R et al Landscape of X chromosome inactivation across human tissues. Nature. (2017) 550(7675):244–8. 10.1038/nature24265

38.

Gillis EE Sullivan JC . Sex differences in hypertension: recent advances. Hypertension. (2016) 68(6):1322–7. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.06602

39.

Writing Group Members, MozaffarianDBenjaminEJGoASArnettDKBlahaMJet alHeart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2016) 133(4):e38–360. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350

40.

Yoon SS Gu Q Nwankwo T Wright JD Hong Y Burt V . Trends in blood pressure among adults with hypertension: United States, 2003 to 2012. Hypertension. (2015) 65(1):54–61. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04012

41.

Lippi G Sanchis-Gomar F Henry BM . COVID-19 and its long-term sequelae: what do we know in 2023?Pol Arch Intern Med. (2023) 133(4):16402. 10.20452/pamw.16402

42.

Sylvester SV Rusu R Chan B Bellows M O'Keefe C Nicholson S . Sex differences in sequelae from COVID-19 infection and in long COVID syndrome: a review. Curr Med Res Opin. (2022) 38(8):1391–9. 10.1080/03007995.2022.2081454

43.

Schiffrin EL Flack JM Ito S Muntner P Webb RC . Hypertension and COVID-19. Am J Hypertens. (2020) 33(5):373–4. 10.1093/ajh/hpaa057

44.

Vassiliou AG Zacharis A Keskinidou C Jahaj E Pratikaki M Gallos P et al Soluble angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is upregulated and soluble endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is downregulated in COVID-19-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Pharmaceuticals. (2021) 14(7):695. 10.3390/ph14070695

45.

Mohammadi P Varpaei HA Seifi A Zahak Miandoab S Beiranvand S Mobaraki S et al Soluble ACE2 as a risk or prognostic factor in COVID-19 patients: a cross-sectional study. Med J Islam Repub Iran. (2022) 36:135. 10.47176/mjiri.36.135

46.

Osman IO Melenotte C Brouqui P Million M Lagier JC Parola P et al Expression of ACE2, soluble ACE2, angiotensin I, angiotensin II and angiotensin-(1-7) is modulated in COVID-19 patients. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:625732. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.625732

47.

Zhang H Lv P Jiang J Liu Y Yan R Shu S et al Advances in developing ACE2 derivatives against SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Microbe. (2023) 4(5):e369–78. 10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00011-3

48.

Wang J Zhao H An Y . ACE2 shedding and the role in COVID-19. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2021) 11:789180. 10.3389/fcimb.2021.789180

49.

Mamedov T Gurbuzaslan I Yuksel D Ilgin M Mammadova G Ozkul A et al Soluble human angiotensin- converting enzyme 2 as a potential therapeutic tool for COVID-19 is produced at high levels in Nicotiana benthamiana plant with potent anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity. Front Plant Sci. (2021) 12:742875. 10.3389/fpls.2021.742875

50.

McMillan P Dexhiemer T Neubig RR Uhal BD . COVID-19—a theory of autoimmunity against ACE-2 explained. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:582166. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.582166

51.

Kleinewietfeld M Manzel A Titze J Kvakan H Yosef N Linker RA et al Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature. (2013) 496(7446):518–22. 10.1038/nature11868

52.

De Ciuceis C Amiri F Brassard P Endemann DH Touyz RM Schiffrin EL . Reduced vascular remodeling, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in resistance arteries of angiotensin II-infused macrophage colony-stimulating factor-deficient mice: evidence for a role in inflammation in angiotensin-induced vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2005) 25(10):2106–13. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000181743.28028.57

53.

Wilck N Matus MG Kearney SM Olesen SW Forslund K Bartolomaeus H et al Salt-responsive gut commensal modulates TH17 axis and disease. Nature. (2017) 551(7682):585–9. 10.1038/nature24628

54.

Eberhardt N Noval MG Kaur R Amadori L Gildea M Sajja S et al SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers pro-atherogenic inflammatory responses in human coronary vessels. Nat Cardiovasc Res. (2023) 2(10):899–916. 10.1038/s44161-023-00336-5

55.

Han B Lv Y Moser D Zhou X Woehrle T Han L et al ACE2-independent SARS-CoV-2 virus entry through cell surface GRP78 on monocytes - evidence from a translational clinical and experimental approach. EBioMedicine. (2023) 98:104869. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104869

56.

Patrick DM Van Beusecum JP Kirabo A . The role of inflammation in hypertension: novel concepts. Curr Opin Physiol. (2021) 19:92–8. 10.1016/j.cophys.2020.09.016

57.

Baranova A Cao H Zhang F . Causal associations and shared genetics between hypertension and COVID-19. J Med Virol. (2023) 95(4):e28698. 10.1002/jmv.28698

58.

Tan JS Liu NN Guo TT Hu S Hua L . Genetic predisposition to COVID-19 may increase the risk of hypertension disorders in pregnancy: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Pregnancy Hypertens. (2021) 26:17–23. 10.1016/j.preghy.2021.08.112

59.

Vora SM Lieberman J Wu H . Inflammasome activation at the crux of severe COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. (2021) 21(11):694–703. 10.1038/s41577-021-00588-x

60.

Halawa S Pullamsetti SS Bangham CRM Stenmark KR Dorfmuller P Frid MG et al Potential long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the pulmonary vasculature: a global perspective. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2022) 19(5):314–31. 10.1038/s41569-021-00640-2

61.

Swenson KE Ruoss SJ Swenson ER . The pathophysiology and dangers of silent hypoxemia in COVID-19 lung injury. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2021) 18(7):1098–105. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202011-1376CME

62.

Tudoran C Tudoran M Lazureanu VE Marinescu AR Pop GN Pescariu AS et al Evidence of pulmonary hypertension after SARS-CoV-2 infection in subjects without previous significant cardiovascular pathology. J Clin Med. (2021) 10(2):199. 10.3390/jcm10020199

63.

Pagnesi M Baldetti L Beneduce A Calvo F Gramegna M Pazzanese V et al Pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular involvement in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. Heart. (2020) 106(17):1324–31. 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317355

64.

Hemani G Zheng J Elsworth B Wade KH Haberland V Baird D et al The MR-base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife. (2018) 7:e34408. 10.7554/eLife.34408

65.

Yang Z Macdonald-Dunlop E Chen J Zhai R Li T Richmond A et al Genetic landscape of the ACE2 coronavirus receptor. Circulation. (2022) 145(18):1398–411. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057888

66.

Faustine I Marteka D Malik A Supriyanto E Syafhan NF . Genotype variation of ACE and ACE2 genes affects the severity of COVID-19 patients. BMC Res Notes. (2023) 16(1):194. 10.1186/s13104-023-06483-z

67.

Luo YS Shen XC Li W Wu GF Yang XM Guo MY et al Genetic screening for hypertension and COVID-19 reveals functional variation of SPEG potentially associated with severe COVID-19 in women. Front Genet. (2022) 13:1041470. 10.3389/fgene.2022.1041470

68.

Hales CM Carroll MD Fryar CD Ogden CL . Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief. (2020) (360):1–8.

69.

Restrepo BJ . Obesity prevalence among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Prev Med. (2022) 63(1):102–6. 10.1016/j.amepre.2022.01.012

70.

Aminian A Bena J Pantalone KM Burguera B . Association of obesity with postacute sequelae of COVID-19. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2021) 23(9):2183–8. 10.1111/dom.14454

71.

Bradley MC Perez-Vilar S Chillarige Y Dong D Martinez AI Weckstein AR et al Systemic corticosteroid use for COVID-19 in US outpatient settings from April 2020 to August 2021. J Am Med Assoc. (2022) 327(20):2015–8. 10.1001/jama.2022.4877

72.

Group RC Horby P Lim WS Emberson JR Mafham M Bell JL et al Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384(8):693–704. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

73.

ISDA. IDSA guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19 (2025). Available online at:https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-treatment-and-management/(Accessed May 30, 2025).

74.

Akter F Araf Y Hosen MJ . Corticosteroids for COVID-19: worth it or not?Mol Biol Rep. (2022) 49(1):567–76. 10.1007/s11033-021-06793-0

75.

National library of medicine (US) CgiNReoC-tR.

76.

Medina C Janssen I Barquera S Bautista-Arredondo S Gonzalez ME Gonzalez C . Occupational and leisure time physical inactivity and the risk of type II diabetes and hypertension among Mexican adults: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. (2018) 8(1):5399. 10.1038/s41598-018-23553-6

77.

Ali AM Kunugi H . COVID-19: a pandemic that threatens physical and mental health by promoting physical inactivity. Sports Med Health Sci. (2020) 2(4):221–3. 10.1016/j.smhs.2020.11.006

78.

Do B Kirkland C Besenyi GM Carissa Smock M Lanza K . Youth physical activity and the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Prev Med Rep. (2022) 29:101959. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101959

79.

Koumpias AM Schwartzman D Fleming O . Long-haul COVID: healthcare utilization and medical expenditures 6 months post-diagnosis. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22(1):1010. 10.1186/s12913-022-08387-3

Summary

Keywords

post-COVID complications, new-onset hypertension, angiotensin-converting enzyme pathway, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction

Citation

Teymourzadeh A, Abramov D, Norouzi S, Grewal D and Heidari-Bateni G (2025) Infection to hypertension: a review of post-COVID-19 new-onset hypertension prevalence and potential underlying mechanisms. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1609768. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1609768

Received

10 April 2025

Accepted

22 July 2025

Published

18 August 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Tlili Barhoumi, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), Saudi Arabia

Reviewed by

Sandra Karanovic Stambuk, University Hospital Centre Zagreb, Croatia

Roberto Giovanni Carbone, University of Genoa, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Teymourzadeh, Abramov, Norouzi, Grewal and Heidari-Bateni.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Giv Heidari-Bateni heidaribg@armc.sbcounty.gov

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.