- 1Department of Residency, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia

- 2Latvian Centre of Cardiology, Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia

- 3Faculty of Medicine and Life Sciences, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia

- 4Department of Genetics and Rare Diseases, Riga East University Hospital, Riga, Latvia

Background: Elevated triglycerides have been established as a cardiovascular risk marker and the literature suggests an association with lipid-rich plaques. We report a case of severe hypertriglyceridaemia that did not result in lipid-rich atherosclerotic lesions.

Case summary: Coronary angiography of a 54-year-old man with a triglyceride level >113.00 mmol/L revealed severe multivessel disease. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) demonstrated a low plaque lipid content, including the maximum lipid-core burden index within 4 mm of 0 in the right coronary artery (RCA), with >90% stenosis in the middle segment. To achieve a rapid reduction in the triglyceride level, intravenous administration of insulin and heparin combined with subsequent plasmapheresis was used, and a triglyceride level of 5.79 mmol/L was achieved before discharge. Genetic testing confirmed familial hypertriglyceridaemia with a pathogenic variant in the lipoprotein lipase gene.

Conclusions: In a patient with severely elevated serum triglycerides and premature three-artery disease, low plaque lipid content was established with the NIRS investigation. Pharmacological management of very severe hypertriglyceridaemia with intravenous insulin and heparin therapy can rapidly decrease triglyceride levels.

1 Introduction

Hypertriglyceridaemia is associated with an increased risk of pancreatitis, as well as coronary artery disease (1, 2) and promotion of early atherosclerosis progression (3). Data suggest that elevated triglycerides are markers of residual cardiovascular risk and biomarkers of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins that are associated with early atherogenesis (4). Higher triglyceride levels have been associated with vulnerable plaque characteristics in intravascular imaging including lipid-rich lesions (5).

We present a case that demonstrates intravascular imaging results and management of coronary artery disease on the background of severely elevated serum triglycerides. Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for extreme hypertriglyceridaemia are also addressed.

2 Case description

2.1 Patient presentation

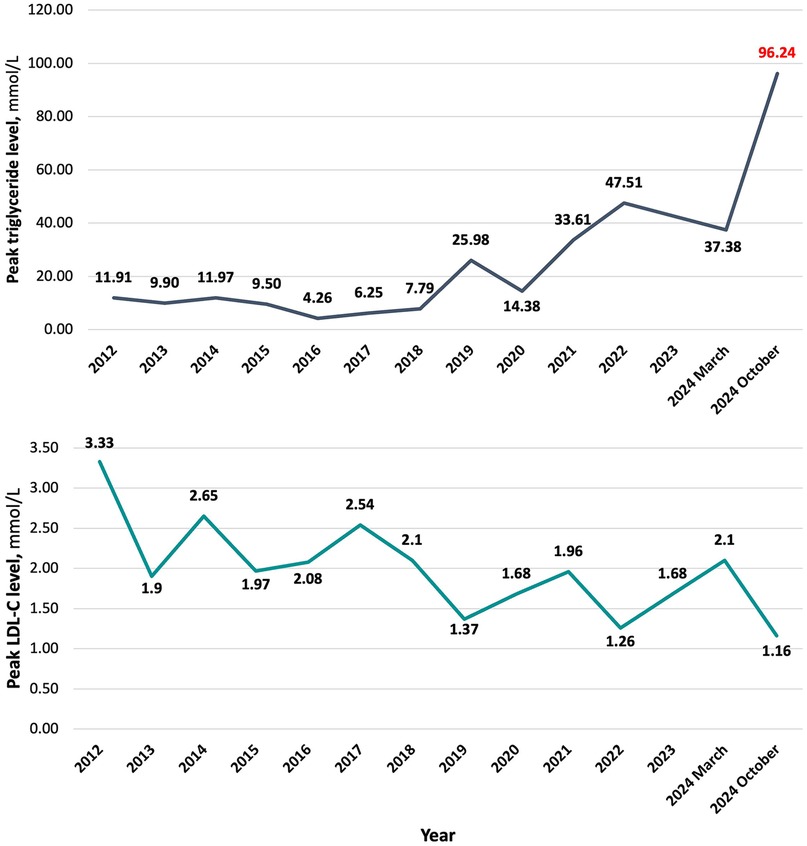

A 54-year-old man was admitted for a scheduled coronary angiography with complaints of pressing and stabbing pain on the left side of the chest that was not associated with physical exercise. Patients height was 187 cm, weight – 100 kg with the corresponding body mass index (BMI) of 28.6 kg/m2. Outpatient clinic blood test results before hospitalization revealed a triglyceride level of 96.24 mmol/L. The blood test results are summarized in Table 1.

2.2 Past medical history

The patient had a known history of type 2 diabetes for approximately 10 years and dyslipidaemia. Three years ago, he had been hospitalized with an acute pancreatitis episode. Triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) peak level dynamics since 2012 are summarized in Figure 1. All LDL-C values were determined with direct measurement. At the time of diagnosis of diabetes, HbA1c level was 6.70%, subsequently levels ranging around 6.50%–8.00% on the background of treatment. Peak HbA1c level throughout all years of having the diagnosis was 9.19%, detected approximately 6 months before the admission. The medications taken on a regular basis were atorvastatin 80 mg o.d., empagliflozin/metformin 12.5/1,000 mg b.i.d., gliclazide 60 mg o.d., and weekly injections of 1 mg semaglutide. Regarding lipid-lowering therapy – he had been taking atorvastatin for around 6 months. Previously, 40 mg of rosuvastatin were used for approximately a year. He had been a current smoker with a history of approximately 30 pack years and admitted to alcohol consumption once every two weeks in amount of around four to five units. There was no data on family history of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular events or death (before age 55 in men and 60 in women).

2.3 Investigations and diagnostics

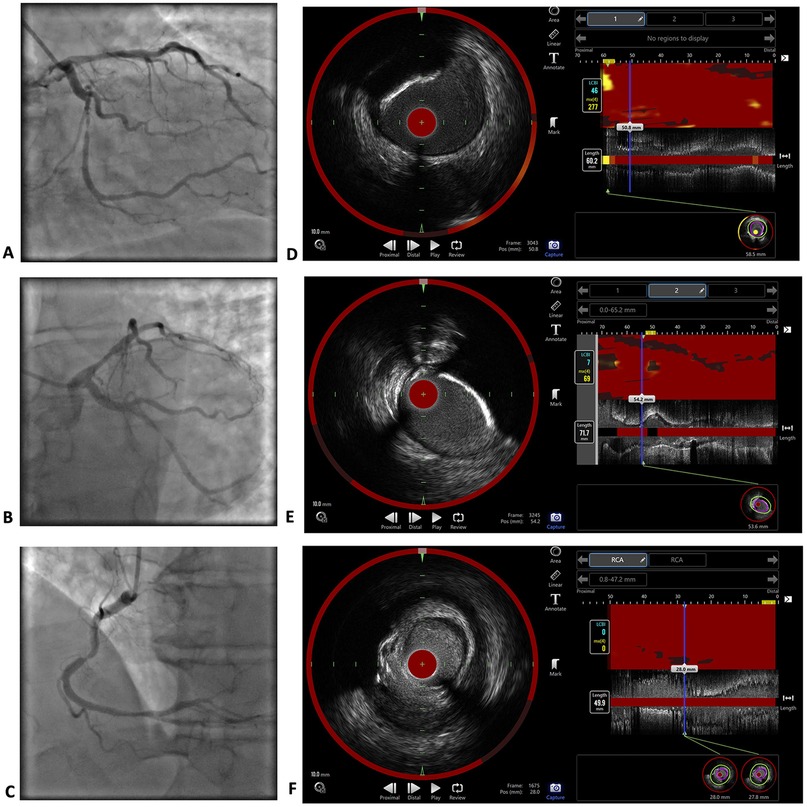

Coronary angiography revealed three-vessel disease with critical >90% stenoses of LCx middle segment and RCA middle third. Additionally, near-infrared spectroscopy-intravascular ultrasound (NIRS-IVUS) was performed for the RCA, LCx and LAD using an automated Dualpro™ catheter (Infraredx, Inc., Burlington, MA, USA) with a 0.5 mm/s pullback. The pullback was performed from the distal third of a coronary artery to the ostium (LM was included in the LAD and LCx pullbacks). The NIRS investigation of the RCA revealed a maximum lipid-core burden index within 4 mm (maxLCBI4 mm) of 0, which corresponds to no lipid content. MaxLCBI4 mm in the LCx and LAD were 69 and 277, respectively; nevertheless, the largest lipid content in the LAD was proximal to the most significant part of the lesion. Coronary angiography and NIRS-IVUS images are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Coronary angiography and NIRS-IVUS imaging results. Coronary angiography images of the LM, LAD and LCx (A,B) and RCA (C) The investigation revealed critical stenoses >90% in the middle third of the LCx and middle third of the RCA, as well as 60%–70% borderline stenoses in the proximal LAD and distal part of the RCA. NIRS-IVUS images of the LAD (D), LCx (E) and RCA (F) The maxLCBI4 mm in the RCA was 0, which corresponds to no lipid content. The maxLCBI4 mm was 277 in the LAD, and 69 in the LCx.

Given the presence of significant coronary artery disease, dopplerography of the brachiocephalic and leg arteries was performed, in which only initial atherosclerosis was detected. To evaluate changes in the pancreas with severe hypertriglyceridaemia, abdominal ultrasound was performed, and no signs of pathology were detected.

Blood tests in the hospital revealed triglyceride levels >113.00 mmol/L. Additionally, lipoprotein(a) testing was performed, with a value of 2.3 nmol/L. The high-sensitivity c-reactive protein (hs-CRP) concentration was 1.02 mg/L. To differentiate elevated haemoglobin level, the erythropoietin level was tested, and a normal value of 18.80 µIU/mL was detected. Lipase level of 59 U/L also did not indicate pathology.

The differential diagnosis for hypertriglyceridaemia included familial chylomicronaemia syndrome due to extreme triglyceride levels, familial hypertriglyceridaemia and combined hypertriglyceridaemia. Secondary hypertriglyceridaemia was also considered due to risk factors such as diabetes mellitus and alcohol consumption. Nevertheless, with such severe elevation of triglyceride levels, secondary hypertriglyceridaemia was unlikely to be the only explanation. Genetic testing revealed a heterozygous pathogenic variant in the lipoprotein lipase (LPL) gene NM_000237.3(LPL):c.701C>T (p.Pro234Leu). This genetic change is well known, and in the heterozygous state is considered pathogenic, confirming the diagnosis of familial hypertriglyceridaemia (ORPHA:444490). Patients family testing was also performed, and this pathology was not found in children.

2.4 Management

Percutaneous coronary intervention with two drug-eluting stents (DESs) was performed for the RCA first, followed by scheduled angioplasty for the LCx with a DES and the LAD with a DES.

Since patient had extremely high triglyceride levels with risk for pancreatitis, alongside necessity to perform prompt percutaneous coronary intervention with DES implantation under these circumstances with limited data in this regard, there was a need for rapid triglyceride level reduction. Standard pharmacotherapy including fibrates was not expected to demonstrate results that quickly, as well as insufficient effect for such high triglycerides was foreseen. Therefore, to manage severely elevated triglycerides, it was decided to perform plasmapheresis. The first procedure was unsuccessful because of filter clogging due to the large amount of triglycerides and chylous blood. Therefore, there was a need to reduce triglyceride levels via pharmacotherapy. Data regarding rapid triglyceride level lowering is mostly based on published case reports and case series. Insulin and heparin are suggested for quick and effective triglyceride reduction (6). Insulin therapy dosing along with intravenous fluid therapy was calculated and administered following case series-based recommendations published by Hoff and Piechowski (7). Intravenous insulin was administered at a rate of 10 units/hour for patient's weight 100 kg. To avoid hypoglycaemia, 250 mL of 5% glucose solution every hour was used every hour. To prevent hypokalaemia, 20 mEq of potassium chloride premix in 250 mL of Ringer's solution was also administered in parallel every hour. Additionally, intravenous heparin with a bolus dose of 4,000 IU, followed by 1,000 IU/hour infusion in normal saline premix, was used. Dosing of heparin was done according to the standard scheme used in our hospital. After two hours of intensive intravenous insulin and heparin therapy, a triglyceride level of 71.17 mmol/L was achieved. Afterwards, successful plasmapheresis could be performed, and three procedures (two consecutive days and skipping one day) were performed. Before plasmapheresis sessions, intravenous insulin treatment was repeated according to the described scheme. At the time of discharge, the triglyceride level was 5.79 mmol/L. Triglyceride level dynamics while in the hospital are summarized in Table 2.

Strict lifestyle modifications were discussed with the patient: a fat-free diet, no added sugars, and alcohol abstinence were recommended.

For long-term hypolipidaemic therapy, atorvastatin/ezetimibe 40/10 mg o.d., fenofibrate 200 mg o.d. and icosapent ethyl 2 g b.i.d. were prescribed. Statin and ezetimibe combination, as well as fibrate were started on the first day of admission, while patient started taking icosapent ethyl only after a couple of months due to limited availability of medication in our country. Taking into consideration high risk of pancreatitis, semaglutide therapy for diabetes was discontinued as a potential additional contributing factor (8, 9).

2.5 Follow-up and outcomes

After two weeks, the triglyceride level of the patient increased to 50.26 mmol/L. From the prescribed lipid-lowering therapy, the patient had not started taking icosapent ethyl but was adherent to the intake of other medications. The lack of icosapent ethyl in therapy is explained by the limited availability of medication in the country. The patient was not strictly compliant with lifestyle modifications, nevertheless understanding the importance of this component of treatment. After discussion with the patient, in addition to pharmacological treatment, plasmapheresis sessions were continued in an outpatient setting. With this treatment, triglyceride levels were maintained at approximately 12 mmol/L. Both pharmacotherapy and plasmapheresis sessions are continued, with good tolerability and no adverse events.

3 Discussion

A patient with extreme hypertriglyceridaemia and severe coronary artery disease is presented.

Elevated triglyceride levels have been associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (10) and increased cardiovascular event risk, including the mechanism of low-grade inflammation (11, 12). Post-hoc analysis of TNT study has demonstrated an association of elevated triglyceride-rich lipoprotein (TRL) levels and adverse cardiovascular event risk (13), triglycerides being the remnant markers of TRL catabolism (14). A recently published study by Shuitema et al. has shown the relation of elevated triglyceride levels to residual cardiovascular risk in patients with established cardiovascular disease, leading to higher cardiovascular events and mortality, irrespective of other lipid target achievement and intensity of lipid-lowering therapy (15). Other supporting data have been published in a PESA study subgroup analysis including patients with low to moderate cardiovascular risk. In this group even in patients having normal LDL-C levels, elevated triglyceride levels were associated with subclinical atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation (16). In the presented patient an increased level of triglycerides has been present for many years and furthermore, demonstrating progressively negative dynamics. Therefore, based on available data, triglycerides should be considered as an important contributor to the extensive coronary artery disease in our patient. Nevertheless, other cardiovascular risk factors are also important, including, smoking and long history of diabetes with insufficient metabolic compensation. Interestingly, in our patient, a low lipid content in the coronary artery lesions was detected with NIRS. In the RCA with critical stenosis, the maxLCBI4 mm value was 0, which corresponds to no lipid content. A possible explanation could be provided by the fact that triglyceride particles that are carried in TRLs – chylomicrons and very-low-density lipoproteins – can not cross the endothelium due to their size (4). While LDL-C is known to be a causal factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, triglycerides are thought to have greater contributions through metabolic dysregulation and proinflammatory effects on endothelial cells and macrophages (2, 17), potentially promoting the early onset of atherosclerosis. TRLs with high content of triglycerides have demonstrated upregulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), thus inducing expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in endothelial cells, leading to monocyte adhesion (18). Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that remnant particles produced through TRL lipolysis are sufficiently small to penetrate subendothelial space and be taken up by arterial wall macrophages (19). Additionally, these remnants are even more atherogenic than LDL-C (20). Another important consideration is investigations performed on high-dose statin therapy and good LDL-C control. The YELLOW trial demonstrated plaque stabilization by lipid burden reduction as evaluated by NIRS in patients taking high-intensity rosuvastatin (21). The EASY-FIT study involving optical coherence tomography revealed a greater increase in plaque fibrous cap thickness and lipid arc reduction with 20 mg atorvastatin therapy than with 5 mg atorvastatin therapy (22). Our patient had been on high-intensity statin treatment for around 1.5 years – 1 year of 40 mg of rosuvastatin and 6 months of 80 mg of atorvastatin, which therefore could have contributed to plaque delipidation at the moment of intravascular imaging being performed.

Familial hypertriglyceridaemia affects approximately 1% of the population, and triglyceride levels usually reach 11.2 mmol/L (23). Regarding the genetic basis, in our patient a heterozygous mutation in LPL gene was found. Mutations in LPL gene, but when in autosomal recessive biallelic pathogenic variant or compound heterozygous variant, cause more than 80% of cases of familial chylomicronemia syndrome that is an extremely rare variant of hypertriglyceridaemia (prevalence is in the range of 1:100 000 to 1:1 000 000) with a very prominent effect. In familial hypertriglyceridaemia the origin is typically either polygenic with cumulative effect of multiple common variants with smaller effect on triglyceride levels, or rare heterozygous variants with a larger effect on triglyceride levels. One of the genes with heterozygous variant implicated in familial hypertriglyceridaemia is the LPL gene, affecting the function of LPL (24). LPL variants are the most prevalent pathogenic variants in heterozygous patients, accounting for 60%–80% of cases (25). In a cohort of patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia in Brazil, the most frequent variant in LPL gene was the c.701C>T (p.Pro234Leu) (26), which was also the one detected in our patient. In patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia in Italy, this was also one of the mutations detected (27). Overall allele frequency is the highest in Europe (7:100 000), it is absent from African and Asia populations (28), but has a strong founder effect in French-Canadian population (29). Heterozygous patients have residual lipolytic capacity of LPL, however secondary factors can overwhelm already genetically compromised lipolysis (25). Our patient had a combination of genetically determined hypertriglyceridaemia with type 2 diabetes, alcohol consumption, and smoking.

The state of hypertriglyceridaemia can interfere with haematological laboratory values. In our patient high haemoglobin level alongside normal red blood cell count and haematocrit was detected. For differentiation of the cause, erythropoietin level was determined, which was normal. Literature data suggests false increase of haemoglobin in samples with high triglycerides with the common colorimethric method, since triglycerides increase blood turbidity (30). Regarding LDL-C estimation, elevated triglycerides do not have significant impact on the values with the use of direct enzymatic assays, while the mathematical Friedewald formula can not be used in cases of severe hypertriglyceridaemia (31). LDL-C values estimated in our patient were all detected by direct assays. Interference of severely elevated triglycerides with NIRS imaging readouts has not been described.

The American College of Cardiology Consensus document states that in patients with elevated triglyceride levels ≥5.65 mmol/L, the primary goal for lowering triglyceride levels is a reduction in pancreatitis risk. Lifestyle recommendations are one of the main hypertriglyceridaemia management pillars (32). For triglyceride-lowering pharmacotherapy with regard to cardiovascular risk reduction, the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias recommend statins as the first choice, followed by combination with icosapent ethyl and fibrate in high-risk patients (31). This strategy was recommended for our patient; nevertheless, the real-life availability of icosapent ethyl in our country attenuated the initiation of the medication. However, considering the severely elevated triglyceride levels, high pancreatitis risk, three-vessel coronary artery disease, and PCI with DES implantation in our patient, the need for rapid triglyceride level reduction was addressed. Although pharmacologial triglyceride-lowering therapy was optimized already on admission, the onset of action as well as expected extent of triglyceride reduction was not sufficient. For fibrates, the estimated triglyceride level reduction ranges are around 30%–50% (33). REDUCE-IT trial demonstrated tiglyceride lowering by 18.3% baseline to 1 year (34). In addition, omega-3 unsaturated fatty acids, specifically icosapent ethyl, are recomenndef with focus on cardiovascular event reduction (35). Therefore, plasmapheresis was the method of choice; nevertheless, the first session was unsuccessful because the plasma separator was clogged with chylous plasma, thus the initial triglyceride level had to be lowered with pharmacological methods. Case series data suggest the efficacy and safety of intravenous insulin and heparin administration for rapid triglyceride lowering. Insulin has the capacity to promote LPL synthesis and activation, whereas heparin helps dissociate heparan sulfate from LPL, resulting in the acceleration of lipoprotein metabolism (7, 36). In our case, dosing calculations were performed based on previously published data, and effective triglyceride level reduction from >113.00 mmol/L to 5.79 mmol/L was achieved by combining a pharmacological approach and plasmapheresis. However, at the time of follow-up, the maintenance of the results was not permanent, presumably due to a lack of compliance with lifestyle modifications.

4 Conclusions

In a patient with severe hypertriglyceridaemia, premature three-artery disease with low plaque lipid content was established. Effective triglyceride level reduction was achieved by combining pharmacological treatment and plasmapheresis.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Riga Stradins University Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

BK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ML: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. RR: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AE: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. KT: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Neifert AR, Su D, Chaar CIO, Sumpio BE. Premature atherosclerosis: a review of current literature. JVS Vasc Insights. (2023) 1:100013. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsvi.2023.100013

2. Toth P. Triglycerides and atherosclerosis: bringing the association into sharper focus. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77(24):3042–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.058

3. Brunzell JD. Clinical practice. Hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. (2007) 357(10):1009–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp070061

4. Farnier M, Zeller M, Masson D, Cottin Y. Triglycerides and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: an update. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. (2021) 114(2):132–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2020.11.006

5. Asakura K, Minami Y, Kinoshita D, Katamine M, Kato A, Katsura A, et al. Impact of triglyceride levels on plaque characteristics in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. (2022) 348:134–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.12.008

6. Garg R, Rustagi T. Management of hypertriglyceridemia induced acute pancreatitis. Biomed Res Int. (2018) 2018:4721357. doi: 10.1155/2018/4721357

7. Hoff A, Piechowski K. Treatment of hypertriglyceridemia with aggressive continuous intravenous insulin. J Pharm Pharm Sci. (2021) 24:336–42. doi: 10.18433/jpps32116

8. Faour O, Boktor M, Yau H, Kinaan M, Mansi IA. GLP-1 receptor agonists initiation and risk of acute pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: a real-world comparative study. AJM Open. (2025) 14:100114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajmo.2025.100114

9. Guo H, Guo Q, Li Z, Wang Z. Association between different GLP-1 receptor agonists and acute pancreatitis: case series and real-world pharmacovigilance analysis. Front Pharmacol. (2024) 15:1461398. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1461398

10. Balling M, Afzal S, Davey Smith G, Varbo A, Langsted A, Kamstrup PR, et al. Elevated LDL triglycerides and atherosclerotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2023) 81(2):136–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.10.019

11. Miller M, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, Qin J, Ray KK, Braunwald E. Impact of triglyceride levels beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol after acute coronary syndrome in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2008) 51(7):724–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.038

12. Nordestgaard BG. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: new insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. Circ Res. (2016) 118(4):547–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306249

13. Vallejo-Vaz AJ, Fayyad R, Boekholdt SM, Hovingh GK, Kastelein JJ, Melamed S, et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein cholesterol and risk of cardiovascular events among patients receiving statin therapy in the TNT trial. Circulation. (2018) 138(8):770–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032318

14. Gugliucci A. Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism: key regulators of their flux. J Clin Med. (2023) 12(13):4399. doi: 10.3390/jcm12134399 Published June 29, 2023.37445434

15. Schuitema PCE, Visseren FLJ, Nordestgaard BG, Teraa M, van der Meer MG, Ruigrok YM, et al. Elevated triglycerides are related to higher residual cardiovascular disease and mortality risk independent of lipid targets and intensity of lipid-lowering therapy in patients with established cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. (2025) 408:120411. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2025.120411

16. Raposeiras-Roubin S, Rosselló X, Oliva B, Fernández-Friera L, Mendiguren JM, Andrés V, et al. Triglycerides and residual atherosclerotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77(24):3031–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.059

17. Ginsberg HN, Packard CJ, Chapman MJ, Borén J, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Averna M, et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants: metabolic insights, role in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and emerging therapeutic strategies-a consensus statement from the European atherosclerosis society. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42(47):4791–806. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab551

18. Rosenson RS, Davidson MH, Hirsh BJ, Kathiresan S, Gaudet D. Genetics and causality of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 64(23):2525–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.042

19. Heo JH, Jo SH. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and remnant cholesterol in cardiovascular disease. J Korean Med Sci. (2023) 38(38):e295. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e295 Published September 25, 2023.37750369

20. Björnson E, Adiels M, Gummesson A, Taskinen MR, Burgess S, Packard CJ, et al. Quantifying triglyceride-rich lipoprotein atherogenicity, associations with inflammation, and implications for risk assessment using non-HDL cholesterol. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2024) 84(14):1328–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.07.034

21. Kini AS, Baber U, Kovacic JC, Limaye A, Ali ZA, Sweeny J, et al. Changes in plaque lipid content after short-term intensive versus standard statin therapy: the YELLOW trial (reduction in yellow plaque by aggressive lipid-lowering therapy). J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 62(1):21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.058

22. Komukai K, Kubo T, Kitabata H, Matsuo Y, Ozaki Y, Takarada S, et al. Effect of atorvastatin therapy on fibrous cap thickness in coronary atherosclerotic plaque as assessed by optical coherence tomography: the EASY-FIT study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 64(21):2207–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.045

23. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, Goldberg IJ, Sacks F, Murad MH, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline [published correction appears in J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(12):4685. Doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3649.]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2012) 97(9):2969–89. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3213

24. Carrasquilla GD, Christiansen MR, Kilpeläinen TO. The genetic basis of hypertriglyceridemia. Curr Atheroscler Rep. (2021) 23(8):39. doi: 10.1007/s11883-021-00939-y

25. Hegele RA. What is the phenotype of heterozygous lipoprotein lipase deficiency? Curr Opin Lipidol. (2025) 36(2):96–103. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000974

26. Mendes C, Loureiro T, Villela D, Bittencourt MI, Sobreira J, Bermeo D, et al. Germline variant analysis from a cohort of patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia in Brazil. Mol Genet Metab Rep. (2024) 40:101100. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2024.101100 Published June 7, 2024.38933898

27. Rabacchi C, Pisciotta L, Cefalù AB, Noto D, Fresa R, Tarugi P, et al. Spectrum of mutations of the LPL gene identified in Italy in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia. Atherosclerosis. (2015) 241(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.04.815

28. Gudmundsson S, Singer-Berk M, Watts NA, Phu W, Goodrich JK, Solomonson M, et al. Variant interpretation using population databases: lessons from gnomAD. Hum Mutat. (2022) 43(8):1012–30. doi: 10.1002/humu.24309

29. Ma Y, Henderson HE, Murthy V, Roederer G, Monsalve MV, Clarke LA, et al. A mutation in the human lipoprotein lipase gene as the most common cause of familial chylomicronemia in French Canadians. N Engl J Med. (1991) 324(25):1761–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106203242502

30. Shi X, Feng K. Hypertriglyceridemia interferes with hemoglobin detection and calibration methods. Clin Lab. (2024) 70(8):10.7754/Clin.Lab.2024.240316. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2024.240316

31. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk [published correction appears in Eur Heart J. 2020 nov 21;41(44):4255. Doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz826.]. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41(1):111–88. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

32. Virani SS, Morris PB, Agarwala A, Ballantyne CM, Birtcher KK, Kris-Etherton PM, et al. 2021 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the management of ASCVD risk reduction in patients with persistent hypertriglyceridemia: a report of the American College of Cardiology solution set oversight committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 78(9):960–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.06.011

33. Skulas-Ray AC, Wilson PWF, Harris WS, Brinton EA, Kris-Etherton PM, Richter CK, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids for the management of hypertriglyceridemia: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2019) 140(12):e673–91. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000709

34. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, Ketchum SB, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. (2019) 380(1):11–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812792

35. Mach F, Koskinas KC, Roeters van Lennep JE, Tokgözoglu L, Badimon L, Baigent C, et al. 2025 focused update of the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J. (2025) 46(42):4359–78. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf190

Keywords: case report, severe hypertriglyceridaemia, premature atherosclerosis, multivessel disease, intravascular imaging, near-infrared spectroscopy, plasmapheresis

Citation: Kokina B, Lapsovs M, Roze R, Lace B, Erglis A and Trusinskis K (2025) Case Report: Severe hypertriglyceridaemia and multivessel coronary artery disease – management and plaque characteristics. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1622667. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1622667

Received: 4 May 2025; Revised: 20 October 2025;

Accepted: 17 November 2025;

Published: 8 December 2025.

Edited by:

Tommaso Gori, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, GermanyReviewed by:

Miodrag Janic, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, SloveniaJosipa Josipovic, UHC Sestre Milosrdnice, Croatia

Copyright: © 2025 Kokina, Lapsovs, Roze, Lace, Erglis and Trusinskis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baiba Kokina, YmFpYmEua29raW5hQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Baiba Kokina

Baiba Kokina Maris Lapsovs

Maris Lapsovs Rudolfs Roze2,3

Rudolfs Roze2,3 Andrejs Erglis

Andrejs Erglis