- Department of Cardiology, Provincial Clinical Medical College of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou University Affiliated Provincial Hospital, Fuzhou, Fujian, China

Objective: Our previous studies revealed that knockdown of JNK pathway-associated phosphatase (JKAP) facilitates atherosclerotic progression by regulating CD4+ T-cell differentiation. Moreover, CD4+ T-cell subtypes are dysregulated and can serve as a prognosis biomarker in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). This study aims to further investigate the correlation between JKAP with CD4+ T-cell subtypes and prognosis in ACS patients who have undergone PCI.

Methods: This study included 173 ACS patients, for whom serum JKAP levels were detected before PCI and 1 month (M1) after PCI via an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Short physical performance battery (SPPB) scores at M1 and major adverse cardiac event (MACE) data were collected. Moreover, serum JKAP levels were detected in 32 healthy control subjects.

Results: JKAP levels were significantly lower in ACS patients vs. healthy control subjects (P < 0.001) and were increased at M1 after PCI vs. before PCI in ACS patients (P < 0.001). JKAP negatively correlated with T-helper (Th)17 cells (P = 0.002) and tended to negatively associate with Th1 cells (P = 0.060), but did not correlate with Th2 or T-regulatory cells. Importantly, JKAP before PCI and at M1 after PCI showed good values in predicting MACE risk via receiver operating curve analyses [area under curve (AUC) = 0.721, AUC = 0.778, respectively]; however, JKAP demonstrated relatively weaker values in predicting an SPPB score of ≤6 points at M1 (AUC = 0.638, AUC = 0.649, respectively). Multivariable analyses revealed that JKAP at M1 after PCI independently predicted a lower risk of MACE (P = 0.045) and an SPPB score of ≤6 points at M1 (P = 0.025).

Conclusion: JKAP may serve as a prognostic biomarker in ACS patients who have undergone PCI.

1 Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is one of the leading causes of global morbidity and mortality, encompassing ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and unstable angina (UA) (1). The underlying pathogenesis of ACS primarily stems from the destabilization of coronary atherosclerotic plaques, and vulnerable plaques—characterized by thin fibrous caps, large lipid cores, and inflammatory cell infiltration—may rupture or erode, triggering platelet aggregation and thrombus formation, ultimately leading to partial or complete vascular occlusion (2, 3). Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) serves as a cornerstone in the management of ACS (4). In cases of STEMI, early PCI facilitates rapid reperfusion of the occluded vessel, salvaging ischemic myocardium, significantly reducing mortality, and improving long-term outcomes; in cases of NSTEMI and UA, PCI aids in plaque stabilization and mitigates the risk of recurrent ischemia (4–8).

JNK pathway-associated phosphatase (JKAP), also called dual-specificity phosphatase 22 (DUSP22), can dephosphorylate the phosphorylated residues of tyrosine, serine, and threonine (9, 10). JKAP is reported to specifically regulate the JNK pathway and modify ERK and NF-κB pathways via dephosphorylating focal adhesion kinase (11, 12); the three pathways are critical for the signaling involved in immunity and inflammation responses (13–15). Moreover, JKAP represses the TCR signaling-mediated T-cell activation, Lck-mediated immune response and autoimmunity, and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines (9, 10, 16–18). Immunity and inflammation are two important triggers for the development and progression of ACS (19–21). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that JKAP might be related to the risk and prognosis of ACS.

We have conducted two previous studies on related topics (22, 23). In the first study, we observed that the deficient JKAP levels promoted atherosclerotic progression by regulating CD4+ T-cell differentiation and inflammatory cytokines through ERK and NF-κB pathways (22). In the other study, we discovered that blood CD4+ T-cell subtypes including T helper (Th) 1, Th2, Th17, and T regulatory (Treg) cells were dysregulated in ACS patients and changed during PCI treatment; moreover, Th1 and Th17 cell proportions could predict physical function recovery and major adverse cardiac event (MACE) risk in these patients (23).

Therefore, in this study, we aim to further investigate the abnormal level of serum JKAP, its correlation with CD4+ T-cell subtypes and clinical characteristics, and its prognostic value in ACS patients who have undergone PCI.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

A total of 173 ACS patients who underwent a PCI procedure between February 2020 and November 2021 were included in this study. The main eligibility criteria were ACS diagnosis, age above 18 years, having undergone a PCI procedure, survival during hospitalization, and normal discharge. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria of ACS patients can be found in our previous study (23). Moreover, 32 healthy control subjects were also included, with the inclusion and exclusion criteria as established in our previous study (23). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuzhou University Affiliated Provincial Hospital (approval number K2024-09-014). Informed consent was obtained from the participants or their immediate families.

2.2 Data collection and prognosis information

This following information relating to ACS patient characteristics was collected for this study: demographics, disease history, biochemical indexes, and disease-related and PCI-related information. The short physical performance battery (SPPB) score was evaluated 1 month (M1) following PCI. The scoring criteria for SPPB were adopted from a previous study (24), and an SPPB score of ≤6 was defined as a mild limitation of physical performance, based on criteria established in our previous study (23). MACE was evaluated according to the follow-up data. The criteria for MACE were established in another study (25), which documented the occurrence of all-cause mortality, acute myocardial infarction, or unplanned coronary revascularization, whichever occurred first.

2.3 Detections

Serum JKAP levels in ACS patients were detected before PCI and at M1 after PCI using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay commercial kit (Meilian Bio-tech, Shanghai, China), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg cell proportions in CD4+ T cells of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from ACS patients were measured before PCI through the application of the Th1/Th2/Th17 Staining Kit (Multi Science, Hangzhou, China) and Regulatory T-Cell Staining Kit (Multi Science, Hangzhou, China) using a flow cytometry assay. The detailed information on flow cytometry has been provided in our previous study (23). Moreover, serum JKAP levels from healthy control subjects were also measured after the inclusion.

2.4 Statistics

SPSS version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, USA) and GraphPad version 9.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, USA) were used for statistical analyses and graphs, respectively. Comparisons were determined using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, or Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate. Correlations were determined using Spearman's rank correlation test. The ability of the parameters to distinguish patients with an SPPB score ≤ 6 at M1 from those with an SPPB score > 6 at M1 was determined by a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the presence of area under the curve (AUC). The same approach was used to evaluate the ability of the parameters to distinguish patients who experienced MACE from those who did not. Cumulative MACE risk was determined using the Kaplan–Meier curve. Furthermore, all biochemical parameters were included in the analyses of independent parameters related to risk of an SPPB score of ≤6 at M1 or MACE using multivariable logistic regression with the conditional forward method that utilized the following variables: JKAP, Th1, Th2, Th17, Treg, red blood cell (RBC), hemoglobin (Hb), white blood cell (WBC), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), serum creatinine (Scr), blood glucose, triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP), cardiac troponin I (cTnI), and creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB). A P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of ACS patients

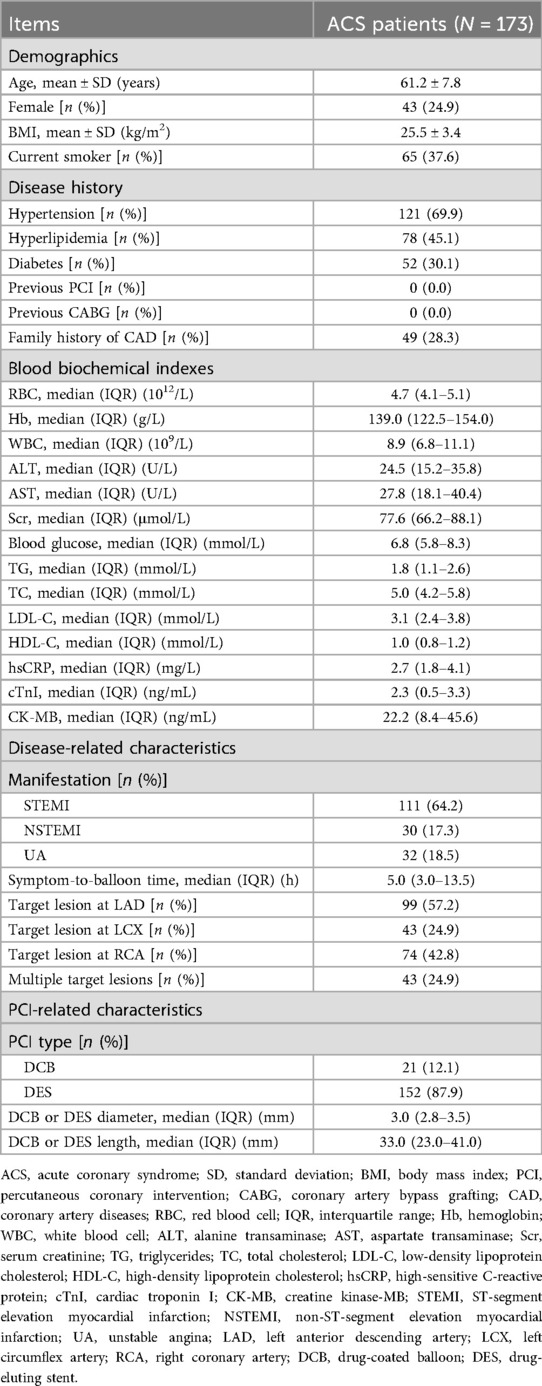

A total of 173 ACS patients were included at the age range of 61.2 ± 7.8 years, comprising 24.9% females and 75.1% males. Of these, 69.9%, 45.1%, and 30.1% of the patients had a medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, respectively. The majority of the patients were diagnosed with STEMI (64.2%), while 17.3% of the patients had NSTEMI and 18.5% had UA. The symptom-to-balloon time was 5.0 [interquartile range (IQR): 3.0–13.5] h. The clinical characteristics of the ACS patients are presented in Table 1.

3.2 JKAP level in ACS patients

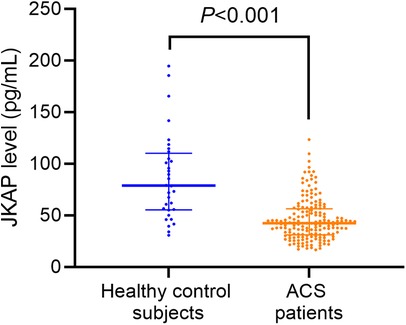

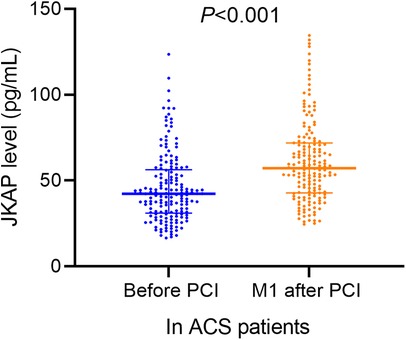

Serum JKAP levels were predominantly lower in ACS patients vs. healthy control subjects [median (IQR): 42.3 (31.1–56.4) vs. 78.8 (55.4–110.1) pg/mL, P < 0.001, Figure 1]. Moreover, serum JKAP levels were increased from 42.3 (31.1–56.4) pg/mL before PCI to 57.2 (IQR: 42.8–71.9) pg/mL at M1 after PCI in ACS patients (P < 0.001, Figure 2).

3.3 Correlation between JKAP level and CD4+ cell subtypes in ACS patients

Serum JKAP levels were negatively correlated with Th17 cells (r = −0.235, P = 0.002), and showed a tendency to be reversely associated with Th1 cells, but did not reach statistical significance (r = −0.143, P = 0.060) in ACS patients (Table 2). However, JKAP levels were not correlated with Th2 cells (r = 0.119, P = 0.120) or Treg cells (r = 0.092, P = 0.231) in ACS patients.

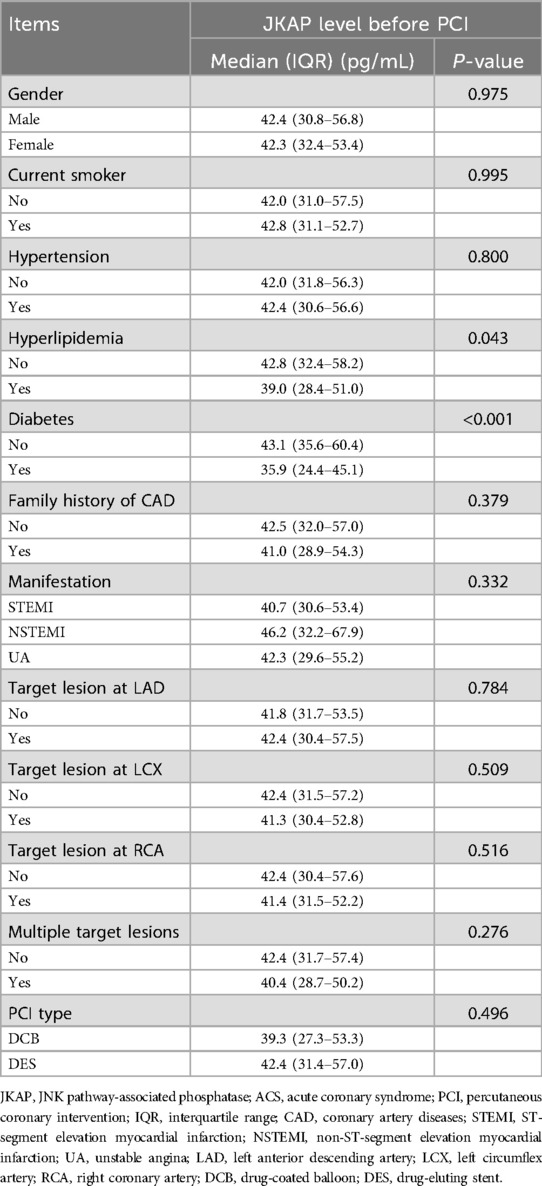

3.4 Correlation between JKAP levels and characteristics in ACS patients

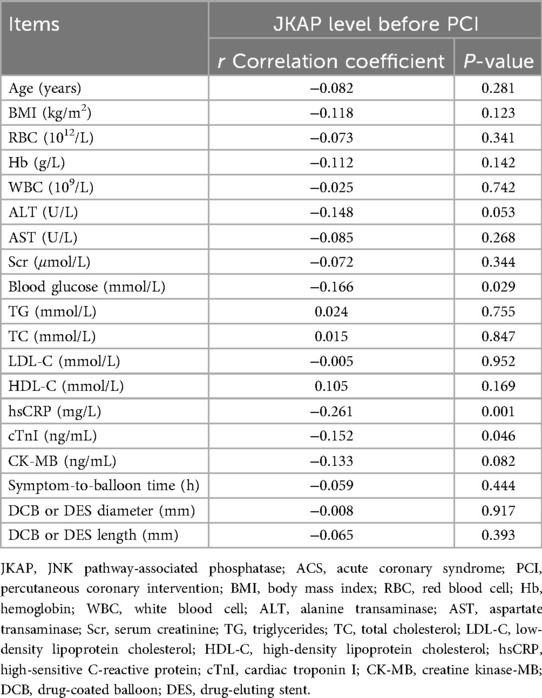

In terms of continuous clinical characteristics, serum JKAP levels were negatively correlated with blood glucose (r = −0.166, P = 0.029), hsCRP (r = −0.261, P = 0.001), and cTnI (r = −0.152, P = 0.046) in ACS patients (Table 3). Regarding categorical clinical characteristics, JKAP levels were negatively associated with the medical history of hyperlipidemia (P = 0.043) and medical history of diabetes (P < 0.001) in ACS patients (Table 4). However, no correlation was found in ACS patients between JKAP levels and other clinical characteristics.

3.5 Prognostic value of JKAP to PCI treatment in ACS patients

The SPPB score at M1 and MACE information after the PCI procedure were collected for prognostic evaluation in ACS patients. Subsequently, the SPPB score at M1 after PCI was found to be 8.0 ± 1.5 points (Supplementary Figure S1A), with 20.7% patients experiencing a mild limitation in physical performance that was defined as an SPPB score of ≤6 points (Supplementary Figure S1B). Regarding MACE, using the Kaplan–Meier curve, the 1-year accumulated MACE risk was 6.6% ± 2.3% and the 2-year accumulated MACE risk was 15.2% ± 4.4% (Supplementary Figure S1C). According to direct calculations, 7.5% of patients experienced MACE while the other 92.5% of patients did not (Supplementary Figure S1D).

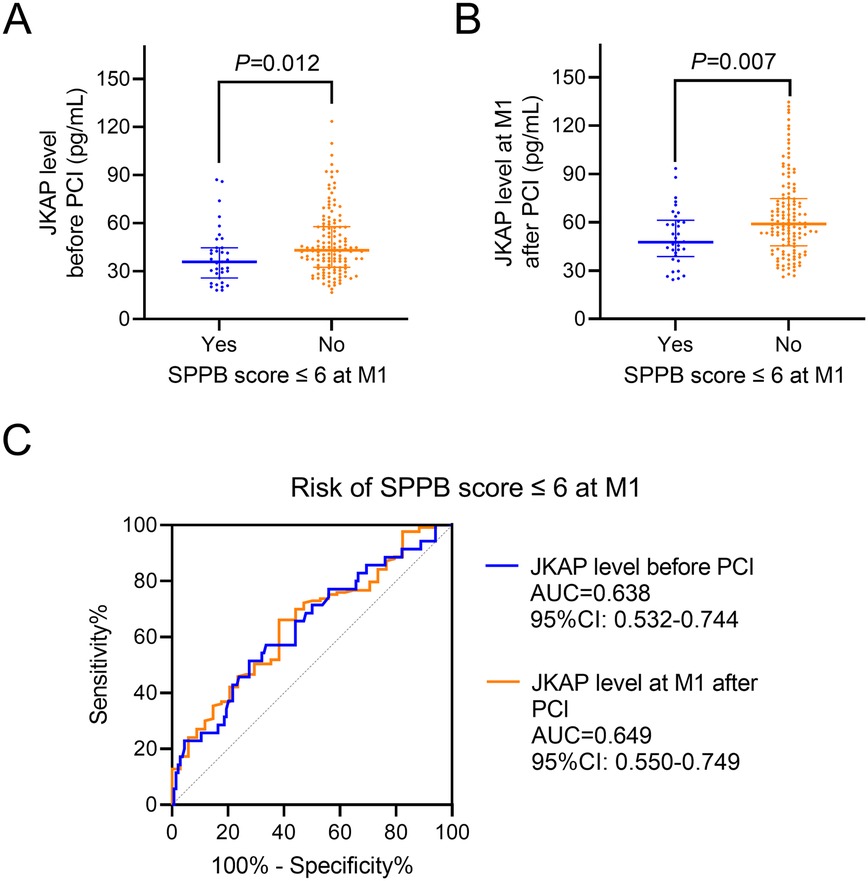

Serum JKAP levels before PCI were lower in patients with an SPPB score of ≤6 at M1 vs. those with scores ≥6 [median (IQR): 35.8 (25.7–44.6) vs. 43.0 (32.4–57.7) pg/mL, P = 0.012, Figure 3A]. JKAP levels at M1 after PCI were also lower in patients with an SPPB score of ≤6 at M1 vs. those with scores ≥6 [median (IQR): 47.7 (38.8–61.3) vs. 59.0 (45.4–74.7) pg/mL, P = 0.007, Figure 3B]. Moreover, JKAP levels before PCI (AUC = 0.638, 95% CI: 0.532–0.744) and JKAP at M1 after PCI (AUC = 0.649, 95% CI: 0.550–0.749) could predict the risk of an SPPB score of ≤6 at M1 in ACS patients who had undergone PCI (Figure 3C), but the predictive values were not strong (both AUC < 0.700).

Figure 3. Correlation between JKAP levels and physical function recovery. Comparison of JKAP levels before PCI (A) and at M1 after PCI (B) between patients having an SPPB score ≤6 at M1 and patients having an SPPB score ≥6. ROC analyses of JKAP levels before PCI and at M1 after PCI for the risk of SPPB score ≤6 at M1 (C).

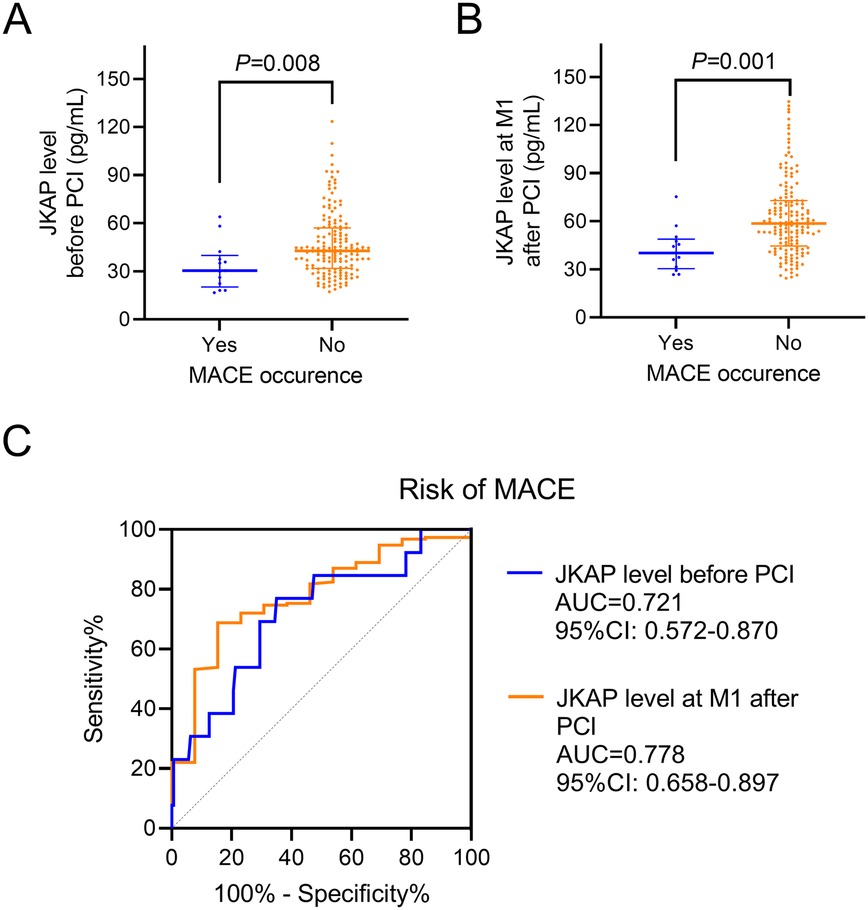

Significantly, JKAP levels before PCI were reduced in patients who experienced MACE vs. those who did not [median (IQR): 30.4 (20.2–39.9) vs. 42.7 (31.8–57.0) pg/mL, P = 0.008, Figure 4A]. JKAP levels at M1 after PCI were also lower in patients who experienced MACE vs. those who did not [median (IQR): 40.2 (30.4–48.9) vs. 58.6 (44.6–72.8) pg/mL, P = 0.001, Figure 4B]. Furthermore, serum JKAP levels before PCI (AUC = 0.721, 95% CI: 0.572–0.870) and JKAP at M1 after PCI (AUC = 0.778, 95% CI: 0.658–0.897) were able to predict risk of MACE in ACS patients who had undergone PCI (Figure 4C), and the predictive values were robust (both AUC > 0.700).

Figure 4. Correlation between JKAP levels and MACE. Comparison of JKAP levels before PCI (A) and at M1 after PCI (B) between patients who experienced MACE and patients who did not. ROC analyses of JKAP levels before PCI and at M1 after PCI for the risk of MACE (C).

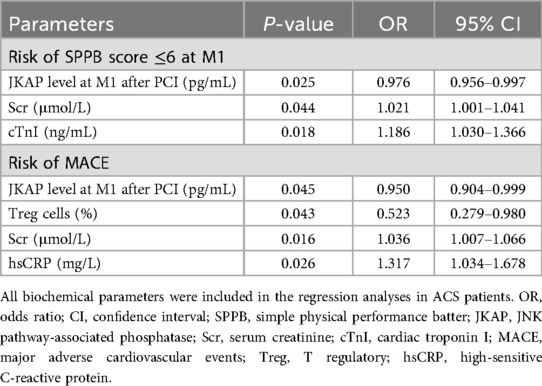

3.6 Prognostic value of JKAP and other biochemical parameters in PCI treatment among ACS patients

All biochemical parameters were included in the multivariable logistic regression with conditional forward method, to analyze their independent correlation with the risk of SPPB score ≤6 at M1 and MACE, respectively (Table 5). JKAP levels at M1 after PCI [odds ratio (OR) = 0.976, P = 0.025] were independently correlated with a lower risk of an SPPB score of ≤6 at M1, while Scr (OR = 1.021, P = 0.044) and cTnI (OR = 1.186, P = 0.018) were independently associated with a higher risk of an SPPB score of ≤6 at M1. Regarding MACE risk, JKAP levels at M1 after PCI (OR = 0.950, P = 0.045) and Treg cells (OR = 0.523, P = 0.043) could independently predict a lower risk of MACE, but Scr (OR = 1.036, P = 0.016) and hsCRP (OR = 1.317, P = 0.026) could independently predict a higher risk of MACE.

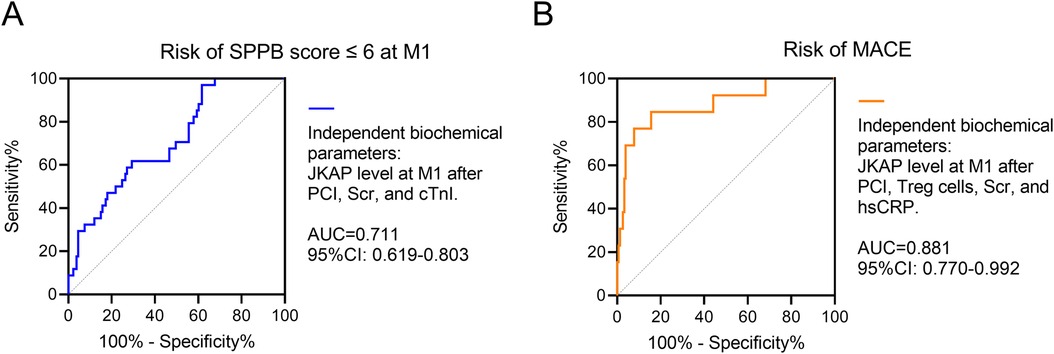

ROC curve analyses further revealed that independent biochemical parameters—including JKAP levels at M1 after PCI, Scr, and cTnI—had a good value (AUC = 0.711, 95% CI: 0.619–0.803) in predicting risk of an SPPB score of ≤6 at M1 in ACS patients who had undergone PCI (Figure 5A). Moreover, the independent biochemical parameters—including JKAP levels at M1 after PCI, Treg cells, Scr, and hsCRP—had an excellent value (AUC = 0.881, 95% CI: 0.770–0.992) in predicting risk of MACE in ACS patients who had undergone PCI (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Independent biochemical parameters for prognosis. ROC analysis of independent biochemical parameters including JKAP levels at M1 after PCI, Scr, and cTnI for the risk of SPPB score ≤6 at M1 (A) ROC analysis of independent biochemical parameters including JKAP levels at M1 after PCI, Treg cells, Scr, and hsCRP for the risk of MACE (B).

4 Discussion

4.1 General discussion

JKAP levels have been found to be dysregulated in a number of immunity- and inflammation-related diseases (22, 26–28). Serum JKAP levels are lower in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and are negatively correlated with systemic inflammation and general disease activity (26). JKAP is also lower in sepsis patients and is inversely associated with levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17 and disease severity-related scales (27). Moreover, JKAP levels are lower in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; JKAP is also inversely related to pulmonary function and IFN-γ and IL-17A levels (28). Our earlier study had revealed that JKAP levels were lower in patients with coronary heart disease, which was negatively associated with CRP, inflammatory cytokines, and stenosis degree; even though the sample size of our previous study was relatively small, it implied the potential involvement of JKAP in ACS patients (22). The present study involved 173 ACS patients and found that JKAP levels were lower in ACS patients, which it was negatively correlated with blood glucose, hsCRP, cTnI, and a medical history of hyperlipidemia and diabetes. The reasons underlying these findings may include the following: (1) Atherosclerosis, aberrant immunity, and chronic inflammation are important triggers of ACS (19–21, 29). JKAP is able to repress the progression of atherosclerosis, immunity, and inflammation (9, 10, 16–18, 22). Through this connection, JKAP levels are reduced in ACS patients. (2) JKAP regulates the JNK, ERK, and NF-κB pathways (11, 12), which provide important signals for glycometabolism and lipid metabolism (30–32); thus, JKAP was negatively correlated with blood glucose and a medical history of hyperlipidemia and diabetes. (3) JKAP represses inflammation and atherosclerotic progression (16–18, 22); thus, JKAP was negatively correlated with hsCRP and cTnI. In addition, this study also found that JKAP levels were increased at M1 after PCI treatment compared to those before PCI possibly because the body is recovering after PCI, leading to revascularization and reduced inflammation; therefore, JKAP levels are higher following PCI.

JKAP is a regulator of CD4+ T-cell differentiation. In brief, it represses the CD4+ T cell from differentiating into Th1 and Th17 cells, and to some degrees promotes its differentiation into Th2 and Treg cells (18, 22, 33). Clinically, JKAP is negatively correlated with Th17 cells while it is positively associated with Th2 cells in patients with diabetes mellitus (34). JKAP is also positively correlated with Th1 cells and Th17 cells in patients with Alzheimer's disease (35). Moreover, a negative relation between JKAP and Th17 cells is also reported in patients with sepsis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (27, 28). Our previous study revealed that JKAP represses the CD4+ T cell from differentiating into Th1 and Th17 cells in vitro and in vivo and is negatively correlated with Th1 and Th17 cells in blood from patients with coronary heart disease (22). This present study found that JKAP was negatively associated with Th17 cells in ACS patients. The reasons underlying these findings may include the following: (1) JKAP represses Th17 differentiation by regulating ERK and NF-κB pathways (22). (2) JKAP plays an important role in regulating the TCR pathway (9, 16), and the TCR pathway is closely implicated in the Th17 differentiation (36).

Given its important role in regulating immunity and inflammation, JKAP has been reported to possess robust prognostic value across several diseases (27, 37, 38). For instance, a lower serum level of JKAP at admission is related to a higher risk of mortality in sepsis patients (27), and a lower level of JKAP at admission is also correlated with a higher risk of stroke recurrence and mortality risk in patients with acute ischemic stroke (37). Moreover, even though JKAP levels at admission are not related to outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, level after treatment are correlated with treatment response and remission to some degree in these patients (38). The present study found that JKAP levels before PCI (AUC = 0.721) and JKAP at M1 after PCI (AUC = 0.778) showed good values in predicting risk of MACE in ACS patients who had undergone PCI. Lower levels of JKAP were associated with a higher risk of MACE. The reasons for these finding may include the following: (1) JKAP represses systemic inflammation (16–18), and reduced inflammation contributes to a lower MACE risk in ACS patients (39). (2) JKAP attenuates the progression of atherosclerotic (22), and decreased atherosclerotic progression leads to a lower MACE risk in ACS patients (29). In addition, this present study also found that JKAP before PCI (AUC = 0.638) and JKAP at M1 after PCI (AUC = 0.649) could predict an SPPB score of ≤6 at M1 in ACS patients who had undergone PCI; however, the predictive values in identifying patients at risk of an SPPB score of ≤6 at M1 were not stronger compared to their predictive strength for MACE. This is possibly because SPPB is affected by numerous factors apart from cardiovascular condition recovery, such as age, original physical status, diet, and lifestyle.

The present study further analyzed the independent biochemical parameters involving JKAP associated with the risk of an SPPB score ≤6 at M1 and MACE. The findings demonstrated that JKAP levels at M1 after PCI proved to be an independent factor predicting lower risk of both an SPPB score ≤6 at M1 and MACE in ACS patients who had undergone PCI. Meanwhile, Tregs, Scr, hsCRP, and cTnI were also independent factors related to the risk of an SPPB score ≤6 at M1 or MACE. Significantly, the independent biochemical parameters comprising JKAP levels at M1 after PCI, Scr, and cTnI showed a robust value (AUC = 0.711) in predicting risk of an SPPB score ≤ 6 at M1; the independent biochemical parameters consisting of JKAP levels at M1 after PCI, Treg cells, Scr, and hsCRP also revealed an excellent value (AUC = 0.881) in predicting risk of MACE in ACS patients who had undergone PCI. These findings further confirm the prognostic value of JKAP in ACS patients who have undergone PCI.

4.2 Limitations

The limitations of the present study are as follows: First of all, serum JKAP levels were compared between ACS patients and healthy control subjects; however, there were no disease control subjects in this study. Therefore, the value of JAKP levels in the ability to distinguish between ACS and other cardiac/cardiovascular diseases can be explored in a future study. Second, the follow-up time in the present study was relatively short for comprehensive evaluation of MACE; thus, long-term evaluation can be explored in a future study. Third, the mechanism of JKAP in predicting MACE or physical function recovery was not directly investigated in this study, which can be explored in a future study. Fourth, blood samples were taken for JKAP level measurement in this study, while JKAP levels through other source samples were not used. Therefore, measurement of JKAP levels in other types of samples could be explored in a future study.

5 Conclusion

JKAP correlates with CD4+ T-cell subtypes and provides prognosis for ACS patients who have undergone PCI, potentially due to its role in immune modulation. However, further large-scale long-term follow-up studies are required for future validation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuzhou University Affiliated Provincial Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Fujian Science and Technology Innovation Joint Funding Project Plan (2024Y9010) and Fujian Provincial Natural Science Funding Project (2025J01068).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1631896/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Singh A, Museedi AS, Grossman SA. Acute Coronary Syndrome. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls (2025). Disclosure: Abdulrahman Museedi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Shamai Grossman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

2. Santos-Gallego CG, Picatoste B, Badimon JJ. Pathophysiology of acute coronary syndrome. Curr Atheroscler Rep. (2014) 16(4):401. doi: 10.1007/s11883-014-0401-9

3. Yuan D, Chu J, Qian J, Lin H, Zhu G, Chen F, et al. New concepts on the pathophysiology of acute coronary syndrome. Rev Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 24(4):112. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm2404112

4. Rao SV, O'Donoghue ML, Ruel M, Rab T, Tamis-Holland JE, Alexander JH, et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI guideline for the management of patients with acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. (2025) 151(13):e771–862. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001309

5. Harper RW, Lefkovits J. Prehospital thrombolysis followed by early angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention where appropriate—an underused strategy for the management of STEMI. Med J Aust. (2010) 193(4):234–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03876.x

6. Foo CY, Bonsu KO, Nallamothu BK, Reid CM, Dhippayom T, Reidpath DD, et al. Coronary intervention door-to-balloon time and outcomes in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Heart. (2018) 104(16):1362–9. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312517

7. Zhang MB, Guo C, Li M, Lv YH, Fan YD, Wang ZL. Comparison of early and delayed invasive strategies in short-medium term among patients with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2019) 14(8):e0220847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220847

8. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E. Unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: part II. Coronary revascularization, hospital discharge, and post-hospital care. Am Fam Physician. (2004) 70(3):535–8.15317440

9. Li JP, Yang CY, Chuang HC, Lan JL, Chen DY, Chen YM, et al. The phosphatase JKAP/DUSP22 inhibits T-cell receptor signalling and autoimmunity by inactivating Lck. Nat Commun. (2014) 5:3618. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4618

10. Shih YC, Chen HF, Wu CY, Ciou YR, Wang CW, Chuang HC, et al. The phosphatase DUSP22 inhibits UBR2-mediated K63-ubiquitination and activation of Lck downstream of TCR signalling. Nat Commun. (2024) 15(1):532. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-44843-w

11. Chen AJ, Zhou G, Juan T, Colicos SM, Cannon JP, Cabriera-Hansen M, et al. The dual specificity JKAP specifically activates the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. (2002) 277(39):36592–601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200453200

12. Ge C, Tan J, Dai X, Kuang Q, Zhong S, Lai L, et al. Hepatocyte phosphatase DUSP22 mitigates NASH-HCC progression by targeting FAK. Nat Commun. (2022) 13(1):5945. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33493-5

13. Huang G, Shi LZ, Chi H. Regulation of JNK and p38 MAPK in the immune system: signal integration, propagation and termination. Cytokine. (2009) 48(3):161–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.08.002

14. Gorelik G, Richardson B. Key role of ERK pathway signaling in lupus. Autoimmunity. (2010) 43(1):17–22. doi: 10.3109/08916930903374832

15. Freigeh GE, Michniacki TF. NF-kappaB and related autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. (2023) 49(4):805–23. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2023.06.008

16. Chuang HC, Tan TH. MAP4K family kinases and DUSP family phosphatases in T-cell signaling and systemic lupus erythematosus. Cells. (2019) 8(11):1433. doi: 10.3390/cells8111433

17. Chen MH, Chuang HC, Yeh YC, Chou CT, Tan TH. Dual-specificity phosphatases 22-deficient T cells contribute to the pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis. BMC Med. (2023) 21(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-02745-6

18. Zhou R, Chang Y, Liu J, Chen M, Wang H, Huang M, et al. JNK pathway-associated phosphatase/DUSP22 suppresses CD4(+) T-cell activation and Th1/Th17-cell differentiation and negatively correlates with clinical activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:781. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00781

19. Flego D, Liuzzo G, Weyand CM, Crea F. Adaptive immunity dysregulation in acute coronary syndromes: from cellular and molecular basis to clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2016) 68(19):2107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.036

20. Wang H, Liu Z, Shao J, Lin L, Jiang M, Wang L, et al. Immune and inflammation in acute coronary syndrome: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. J Immunol Res. (2020) 2020:4904217. doi: 10.1155/2020/4904217

21. Occhipinti G, Brugaletta S, Abbate A, Pedicino D, Del Buono MG, Vinci R, et al. Inflammation in coronary atherosclerosis: diagnosis and treatment. Heart. (2025) 111(17):801–10. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2024-325408

22. Chen X, Fang M, Hong J, Guo Y. JNK pathway-associated phosphatase deficiency facilitates atherosclerotic progression by inducing T-helper 1 and 17 polarization and inflammation in an ERK- and NF-kappaB pathway-dependent manner. J Atheroscler Thromb. (2024) 31(10):1460–78. doi: 10.5551/jat.64754

23. Chen X, Fang M, Hong J, Guo Y. Longitudinal variations in Th and Treg cells before and after percutaneous coronary intervention, and their intercorrelations and prognostic value in acute syndrome patients. Inflammation. (2025) 48(1):316–30. doi: 10.1007/s10753-024-02062-x

24. Volpato S, Cavalieri M, Sioulis F, Guerra G, Maraldi C, Zuliani G, et al. Predictive value of the short physical performance battery following hospitalization in older patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2011) 66(1):89–96. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq167

25. Belkacemi A, Agostoni P, Nathoe HM, Voskuil M, Shao C, Van Belle E, et al. First results of the DEB-AMI (drug eluting balloon in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction) trial: a multicenter randomized comparison of drug-eluting balloon plus bare-metal stent versus bare-metal stent versus drug-eluting stent in primary percutaneous coronary intervention with 6-month angiographic, intravascular, functional, and clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2012) 59(25):2327–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.027

26. Sun L, Tu J, Chen X, Dai M, Xia X, Liu C, et al. JNK pathway-associated phosphatase associates with rheumatoid arthritis risk, disease activity, and its longitudinal elevation relates to etanercept treatment response. J Clin Lab Anal. (2021) 35(4):e23709. doi: 10.1002/jcla.23709

27. Yu D, Peng X, Li P. The correlation between Jun N-terminal kinase pathway-associated phosphatase and Th1 cell or Th17 cell in sepsis and their potential roles in clinical sepsis management. Ir J Med Sci. (2021) 190(3):1173–81. doi: 10.1007/s11845-020-02382-5

28. Gao W, Gao L, Yang F, Li Z. Circulating JNK pathway-associated phosphatase: a novel biomarker correlates with Th17 cells, acute exacerbation risk, and severity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. J Clin Lab Anal. (2022) 36(1):e24153. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24153

29. Gotlieb AI. Atherosclerosis and acute coronary syndromes. Cardiovasc Pathol. (2005) 14(4):181–4. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2005.03.007

30. Han Y, Zhang Z, Song Q, Sun S, Li W, Yang F, et al. Modulation of glycolipid metabolism in T2DM rats by Rubus irritans Focke extract: insights from metabolic profiling and ERK/IRS-1 signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. (2024) 332:118341. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.118341

31. Vallerie SN, Hotamisligil GS. The role of JNK proteins in metabolism. Sci Transl Med. (2010) 2(60):60rv5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001007

32. Capece D, Verzella D, Flati I, Arboretto P, Cornice J, Franzoso G. NF-kappaB: blending metabolism, immunity, and inflammation. Trends Immunol. (2022) 43(9):757–75. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2022.07.004

33. Yang Q, Zhuang J, Cai P, Li L, Wang R, Chen Z. JKAP Relates to disease risk, severity, and Th1 and Th17 differentiation in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. (2021) 8(9):1786–95. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51420

34. Tong M, Gu C, Yu Q, Ma J. Serum JKAP reflects Th2 and Th17 cell levels, and diabetic nephropathy risk and severity in diabetes mellitus patients. Biomark Med. (2023) 17(17):701–10. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2023-0422

35. Zeng J, Liu J, Qu Q, Zhao X, Zhang J. JKAP, Th1 cells, and Th17 cells are dysregulated and inter-correlated, among them JKAP and Th17 cells relate to cognitive impairment progression in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Ir J Med Sci. (2022) 191(4):1855–61. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02749-2

36. Woo JS, Srikanth S, Kim KD, Elsaesser H, Lu J, Pellegrini M, et al. CRACR2A-mediated TCR signaling promotes local effector Th1 and Th17 responses. J Immunol. (2018) 201(4):1174–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800659

37. Zhang J, Yang J, Hu J, Zhao W. Clinical value of serum JKAP in acute ischemic stroke patients. J Clin Lab Anal. (2022) 36(4):e24270. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24270

38. Song D, Zhu X, Wang F, Sun J. Longitudinal monitor of Jun N-terminal kinase pathway associated phosphatase reflects clinical efficacy to triple conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs treatment in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Inflammopharmacology. (2021) 29(4):1131–8. doi: 10.1007/s10787-021-00823-w

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, percutaneous coronary intervention, JKAP, CD4+ T cells, prognosis

Citation: Chen X and Hong J (2025) Serum JKAP as a potential prognostic biomarker in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1631896. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1631896

Received: 20 May 2025; Revised: ;

Accepted: 29 October 2025;

Published: 12 December 2025.

Edited by:

Dragos Cretoiu, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, RomaniaReviewed by:

Larisa Anghel, Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases, RomaniaAzmi Eyiol, Konya Beyhekim State Hospital, Türkiye

Copyright: © 2025 Chen and Hong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinjing Chen, Y2hlNTg5NTcxNTJAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Xinjing Chen

Xinjing Chen Jingxuan Hong

Jingxuan Hong