Abstract

Background:

Research on the limits of compensatory right heart remodeling and the effects of pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) targeted therapies on these mechanisms is limited.

Method:

Chest x-ray and echocardiographic data were collected from 143 deceased patients with PAH confirmed by right heart catheterization at their end-stage disease. Right heart remodeling was compared across different PAH treatment strategies.

Results:

This study of 143 deceased PAH patients (49 ± 17 years, 74.1% female) characterized right heart remodeling at the time of death. Mean cardiothoracic ratio (CTR), right atrial area (RAA) and mid-cavity RV linear dimension (RVD) measured by echocardiography were 0.61 ± 0.09, 27 cm2 (median 27, IQR 21–38), and 4.97 ± 0.97 cm, respectively, with extremes of 0.88, 102 cm2, and 7.50 cm. Intensive therapy resulted in larger CTR (0.63 ± 0.08 vs. 0.60 ± 0.09, p = 0.016), RAA (30 [(24–40)] vs. 25 [(19–34)] cm2, p = 0.020), and RVD (5.30 ± 0.97 vs. 4.65 ± 0.85 cm, p < 0.001) compared with non triple therapy. After adjusting for confounders, intensive therapy independently predicted increases in CTR (0.03, 95% CI 0.00-0.05, p = 0.054), RAA (6.63 cm2, 95% CI 1.46-11.80, p = 0.013), and RVD (0.66 cm, 95% CI 0.34-0.98, p < 0.001).

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that more aggressive PAH treatment is associated with greater right heart remodeling, highlighting the complex relationship between therapeutic intervention and disease progression in PAH patients.

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) encompasses various conditions characterized by elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), including idiopathic, heritable, and PAH associated with connective tissue disease or congenital heart disease (1–3). Persistent elevation in pulmonary artery pressure increases right ventricular afterload, triggering adaptive changes to maintain cardiac output (4). Over time, chronic pressure overload eventually leads to maladaptive right ventricular (RV) remodeling, marked by myocardial cell proliferation and fibrosis. This structural and functional remodeling represents a critical turning point in PAH progression (5). RV remodeling not only alters cardiac morphology but also impairs contractility, decreasing cardiac output and potentially leading to right heart failure, a major cause of mortality in PAH (6).

Significant advancements in drug therapies have markedly impacted right heart remodeling and improved the prognosis for patients with PAH (7). Current treatments target four main signaling pathways: endothelin-1 (8, 9), nitric oxide (10–12), prostacyclin (13), and the Activin/morphogenetic protein(BMP) pathway (14). While monotherapy options exist, combination therapies (7), including current triple and emerging quadruple drug regimens, have demonstrated greater efficacy. For those who remain unresponsive to these advanced therapies, lung transplantation remains a last resort.

Despite these therapeutic advances, disease progression, irreversible RV remodeling, and death still occur. Currently, limited research explores the limits of RV remodeling compensation and the impact of targeted therapies on these compensatory mechanisms. Therefore, further investigation is warranted to determine how these pharmacological strategies affect the limits of RV adaptation and to elucidate whether these limits vary among PAH patients.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in department of pulmonary circulation, Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital. All patients diagnosed with PAH in our department undergo regular follow-up, and for those whose deaths are confirmed during this follow-up period, we gather their information. We collected clinical data at baseline and the last visit data of these patients, encompassing demographic characteristics, laboratory test results, echocardiographic findings, chest radiographs and hemodynamic data. Our study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the ethics committee of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (approval number: K16-293).

Patients had to meet the following criteria to be included in the study: (i) diagnosis between January 1, 2013, and June 30, 2024; (ii) confirmed diagnosis of Group 1 PAH, defined as mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) >20 mmHg, pulmonary artery wedge pressure(PAWP) <15 mmHg and pulmonary vascular resistance(PVR) > 2WU by right heart catheterization (RHC) at the time of diagnosis; (iii) visit data available within one year before death; (iv) death confirmed by telephone or visit. Patients who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for PAH and those lacking relevant visit data within one year before death were excluded.

Clinical, functional and hemodynamic characteristics

A comprehensive evaluation of clinical data was performed, including demographic information such as age, sex, as well as medical and family histories. The hemodynamic data were collected, including mPAP, PAWP and right atrial pressure (RAP). The cardiac index (CI) was determined by measuring cardiac output (CO) with the standard thermodilution technique and divided by body surface area. PVR was calculated using the formula: (mPAP-PAWP)/CO (15).

Cardiothoracic ratio and echocardiography assessment

The cardiothoracic ratio (CTR) on a chest x-ray is determined by comparing the width of the heart to the width of the chest (16). All patients underwent CTR measurements at both baseline and during their last visit.

All echocardiographic data were acquired using commercially available equipment (Vivid 7, GE Healthcare) in standard views. Measurements were obtained from the mean of three consecutive beats based on the American Society of Echocardiography Guidelines (17). The echo parameters and derived assessments that we focused on common and widely available for daily clinical practice, including RA area, mid-cavity RV linear dimension(RVD), left ventricular end diastolic diameter (LVEDD), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular end-diastolic eccentricity index (LV-EId), pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (PASP), tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), and presence of pericardial effusion.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages, while continuous data are presented as either mean ± SD or median with interquartile range (IQR), depending on the data distribution. Continuous data were compared using Welch Two Sample t-test or one-way ANOVA for parametric data, and Wilcoxon signed-rank/Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test for nonparametric data. Linear regression analysis is used to describe the relationship between intensity of PAH therapy and the extent of heart remodeling. Multiple models were constructed, each adjusting for a different set of covariates to provide a nuanced understanding of how these covariates influence the observed association. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant for all statistical tests.

Results

Characteristics of study population

A total of 143 deceased PAH patients met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Demographic, classification, hemodynamic, baseline right ventricular morphology and function, treatment, and cardiac remodeling data of the study population are presented in Table 1. The average age was 49 ± 17 years, with 37 (25.9%) males and 106 (74.1%) females. Time from symptom onset to death was 6.3 ± 4.5 years, and time from diagnosis to death was 3.4 ± 3.6 years. PAH classifications were idiopathic (63, 44.1%), heritable (4, 2.8%), connective tissue disease (51, 35.7%), portal hypertension (2, 1.4%), congenital heart disease (20, 14.0%), and PVOD/PCH (3, 2.1%).

Table 1

| Characteristic | N = 143a |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 49 ± 17 |

| Female | 106 (74.1%) |

| Symptom-to-death intervalb, yr | 6.3 ± 4.5 |

| Diagnosis-to-death intervalc, yr | 3.4 ± 3.6 |

| PAH Classifications | |

| Idiopathic | 63 (44.1%) |

| Heritable | 4 (2.8%) |

| Connective tissue disease | 51 (35.7%) |

| Portal hypertension | 2 (1.4%) |

| Congenital heart disease | 20 (14.0%) |

| PVOD/PCH | 3 (2.1%) |

| Baseline Characteristicsd | |

| RHC | |

| MPAP, mmHg | 57 ± 16 |

| PAWP, mmHg | 7.1 ± 4.4 |

| RAP, mmHg | 6.1 ± 5.0 |

| CI, L/min/m2 | 2.60 ± 1.11 |

| PVR, Wood units | 13 ± 7 |

| SVO2, % | 58 ± 14 |

| Chest x-ray and Echocardiography | |

| CTR | 0.62 ± 0.09 |

| RAA, cm2 | 26.72 ± 12.77 |

| LVEDD, cm | 3.56 ± 0.73 |

| LV-EId | 1.55 ± 0.35 |

| TAPSE | 1.57 ± 0.36 |

| PAH therapy | |

| Mono-therapy | 20 (14.0%) |

| Double-therapy | 56 (39.2%) |

| Triple-therapy | 67 (46.9%) |

| Cause of death | |

| Sudden death | 41 (28.7%) |

| Right heart failure | 89 (62.2%) |

| Othere | 13 (9.1%) |

Clinical characteristics of deceased patients with PAH.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and number (percentage) for categorical variables.

Time was calculated from initial onset of PAH-related symptoms to time of death.

Time from the date of PAH confirmation by right heart catheterization (RHC) to death.

All clinical parameters reflect the patients’ terminal status, with the exception of hemodynamic measurements obtained during baseline RHC.

Non-cardiovascular causes of death comprised: Infectious complications (n = 6); Massive hemoptysis (n = 3); Intracranial hemorrhage (n = 2); Post-transplant mortality (n = 1); Procedural complications during colonoscopy (n = 1).

PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PVOD, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease; PCH, pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis; RHC, right heart catheterization; MPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PAWP, pulmonary artery wedge pressure; RAP, right atrial pressure; CI, cardiac index; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; SvO₂: Mixed venous oxygen saturation; CTR, cardiothoracic ratio; RAA, right atrial area; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LV-EId, left ventricular end-diastolic eccentricity index; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

At diagnosis, right heart catheterization demonstrated mPAP of 57 ± 16 mmHg, PAWP of 7.1 ± 4.4 mmHg, RAP of 6.1 ± 5.0 mmHg, CO of 3.08 ± 2.23 L/min, CI of 2.60 ± 1.11 L/min/m2, PVR of 13 ± 7 Wood units, and a mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO₂) of 58 ± 14%. For baseline Chest x-ray and Echocardiography, we obtained data on some indicators, with CTR being 0.62 ± 0.09, RAA being 26.72 ± 12.77, LVEDD being 3.56 ± 0.73, LV-EId being 1.55 ± 0.35, and TAPSE being 1.57 ± 0.36. With respect to PAH-specific treatments, 20 (14.0%) received monotherapy (14 on phosphodiesterase type 5 [PDE5] inhibitors, 6 on endothelin receptor antagonists [ERAs]), 56 (39.2%) received double therapy (all on PDE5 inhibitors plus ERAs), and 67 (46.9%) were treated with triple therapy (ERAs, PDE5 inhibitors, and prostacyclin analogues). The primary cause of death was right heart failure in 89 (62.2%) patients. Sudden death accounted for 41 (28.7%) deaths. Other causes of death included infection (n = 6), hemoptysis (n = 3), cerebral hemorrhage (n = 2), transplant-related death (n = 1), and colonoscopy complications (n = 1).

Right heart remodeling at the time of death

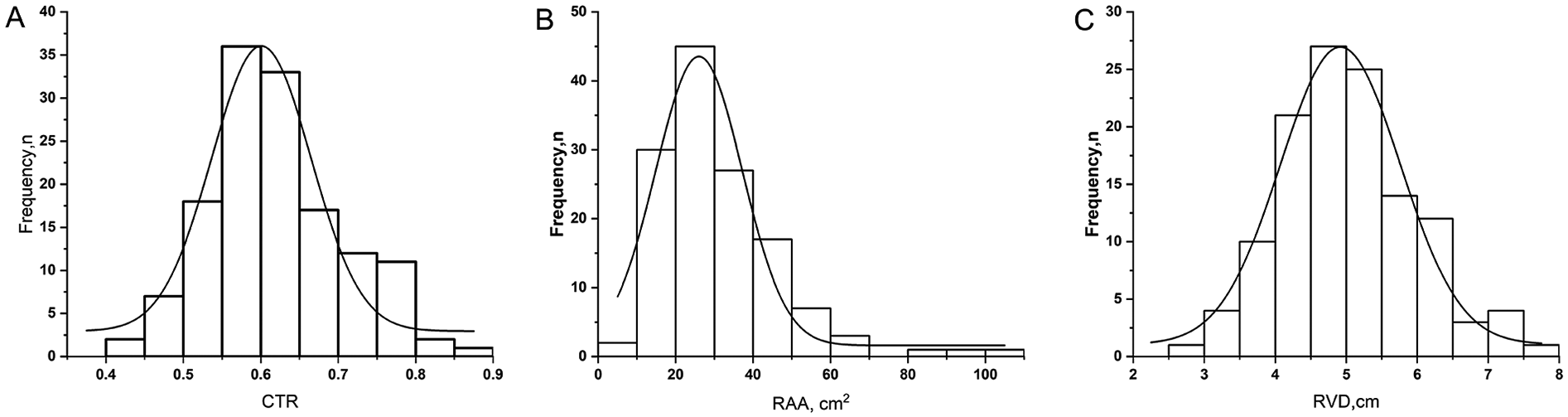

At death, chest radiography showed a CTR of 0.61 ± 0.09. Echocardiography revealed RAA of 27 cm2 (median 27, IQR 21–38), RVD of 4.97 ± 0.97 cm, LVEDD of 3.40 cm (median 3.40, IQR 3.00–4.00), and LV-EID of 1.56 (median 1.56, IQR 1.34–1.75) (Table 2). Notably, the extreme limits of compensatory remodeling in end-stage disease included a CTR as high as 0.88, an RAA of 102 cm2, and an RVD of 7.50 cm. Figure 1 illustrates the frequency distribution of right ventricular remodeling parameters at death.

Table 2

| Characteristic | Total N = 143 |

PAH target therapy | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono-therapy N = 20a |

Double-therapy N = 56a |

Triple-therapy N = 67a |

|||

| CTR | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 0.60 ± 0.09 | 0.60 ± 0.09 | 0.63 ± 0.08 | 0.054b |

| RAA, cm2 | 27 (21, 38) | 21 (18, 32) | 26 (20, 34) | 30 (24, 40) | 0.037c |

| RVD, cm | 4.97 ± 0.97 | 4.19 ± 0.87 | 4.79 ± 0.80 | 5.30 ± 0.97 | <0.001b |

| LVEDD, cm | 3.40 (3.00, 4.00) | 3.80 (3.20, 4.50) | 3.20 (2.80, 3.90) | 3.40 (3.00, 4.05) | 0.059c |

| LV-EId | 1.56 (1.34, 1.75) | 1.43 (1.37, 1.69) | 1.56 (1.32, 1.72) | 1.57 (1.34, 1.85) | 0.514c |

Compensatory cardiac remodeling in PAH patients under different treatment strategies.

Mean ± SD; Median (IQR).

One-way ANOVA.

Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test.

PAH, pulmonary Arterial Hypertension; CTR, cardiothoracic Ratio; RAA, right atrial Area; RVD, mid-cavity right ventricular linear dimension; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LV-Eid, left ventricular end-diastolic eccentricity index.

Figure 1

Frequency distribution of right ventricular remodeling parameters at the time of death in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The histograms show the distribution of (A) CTR (cardiothoracic ratio measured from chest x-ray), (B) RAA (Right Atrial Area measured by echocardiography, cm2), and (C) RVD (Mid-cavity Right Ventricular Linear Dimension by echocardiography, cm). The superimposed curves represent unimodal probability density functions fitted to the respective histograms.

Before death, varying treatment strategies were associated with different degrees of right heart remodeling (Table 2). Monotherapy (20 patients) resulted in a CTR of 0.60 ± 0.09, RAA of 21 cm2 (median 18, IQR 18–32), and RVD of 4.19 ± 0.87 cm; double therapy (56 patients) showed a CTR of 0.60 ± 0.09, RAA of 26 cm2 (median 20, IQR 20–34), and RVD of 4.79 ± 0.80 cm; and triple therapy (67 patients) led to a CTR of 0.63 ± 0.08, RAA of 30 cm2 (median 24, IQR 24–40), and RVD of 5.30 ± 0.97 cm. Statistical analysis indicated significant differences between treatment groups for RAA (p = 0.037) and RVD (p < 0.001), and a near-significant difference for CTR (p = 0.054). LVEDD and LV-EID remained relatively consistent across the different treatment approaches.

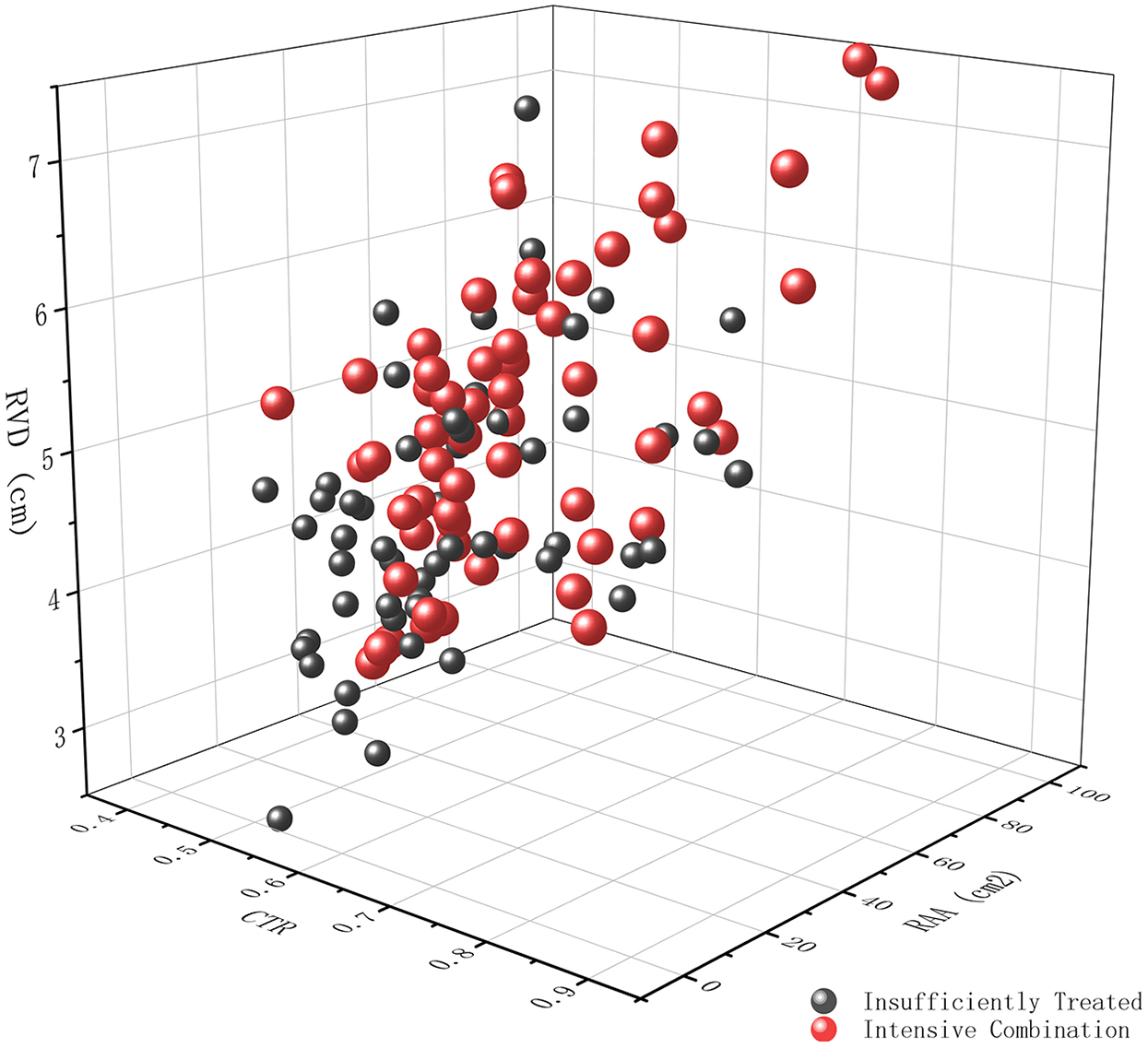

Compared with those who were insufficiently treated, patients receiving intensive combination therapy had a significantly larger RVD (5.30 ± 0.97 cm vs. 4.65 ± 0.85 cm, p < 0.001) and RAA (30 [24–40] cm2 vs. 25 [19–34] cm2, p = 0.020) (Table 3, Figure 2). However, no significant differences were observed in LVEDD or LV-EID. The CTR was slightly higher under intensive combination therapy (0.63 ± 0.08 vs. 0.60 ± 0.09, p = 0.016).

Table 3

| Characteristic | PAH target therapy | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficiently treated N = 76a | Intensive combination N = 67a | ||

| CTR | 0.60 ± 0.09 | 0.63 ± 0.08 | 0.016b |

| RAA, cm2 | 25 (19, 34) | 30 (24, 40) | 0.020c |

| RVD, cm | 4.65 ± 0.85 | 5.30 ± 0.97 | <0.001b |

| LVEDD, cm | 3.35 (2.93, 4.00) | 3.40 (3.00, 4.05) | 0.845c |

| LV-EId | 1.55 (1.32, 1.71) | 1.57 (1.34, 1.85) | 0.299c |

Compensatory cardiac remodeling in PAH comparing insufficient and intensive therapy approaches.

Mean ± SD; Median (IQR).

Welch Two Sample t-test.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; CTR, cardiothoracic ratio; RAA, right atrial area; RVD, mid-cavity right ventricular linear dimension; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LV-Eid, left ventricular end-diastolic eccentricity index.

Figure 2

Three-dimensional scatter plot demonstrating the impact of treatment intensity on right ventricular remodeling. The plot depicts the relationship between cardiothoracic ratio (CTR) measured from chest x-ray, Mid-cavity Right Ventricular Linear Dimension (RVD, cm), and right atrial area (RAA, cm2) measured by echocardiography, in patients receiving either insufficient treatment (dark grey spheres) or intensive combination therapy (red spheres).

Impact of PAH therapy on right ventricular remodeling limits

Linear regression analysis demonstrated a clear association between the intensity of PAH therapy and the extent of right ventricular remodeling, as detailed in Table 4. Here, we defined intensive therapy as triple therapy, while non triple therapy is defined as insufficient treatment. Patients receiving intensive combination therapy experienced significantly greater increases in CTR, RAA, and RVD compared to those receiving insufficient therapy. The analysis revealed that intensive therapy led to a 0.04 increase in CTR (95% CI 0.01–0.06, p = 0.016), a 6.12 cm2 increase in RAA (95% CI 0.87–11.36, p = 0.024), and a 0.65 cm increase in RVD (95% CI 0.33–0.98, p < 0.001). Adjusting for age and sex (Model I) maintained the statistical significance of these findings, the increase in CTR was 0.03 (95% CI 0.00-0.06, p = 0.016), the increase in RAA was 5.67 cm2 (95% CI 0.40–10.95, p = 0.037), and the increase in RVD was 0.63 cm (95% CI 0.31-0.95, p < 0.001). Further adjusting for PAH classifications (Model II) also demonstrated significant increases with intensive therapy for CTR (0.03, 95% CI 0.00–0.06, p = 0.051), RAA (6.85 cm2, 95% CI 1.62–12.08, p = 0.011), and RVD (0.67 cm, 95% CI 0.35-0.99, p < 0.001). Finally, even after adjusting for cause of death in addition to age, sex, and PAH classifications (Model III), intensive therapy remained significantly associated with increased CTR (0.03, 95% CI 0.00-0.05, p = 0.054), RAA (6.63 cm2, 95% CI 1.46–11.80, p = 0.013), and RVD (0.66 cm, 95% CI 0.34–0.98, p < 0.001).

Table 4

| Characteristic | Unadjusted | Model I | Model II | Model III | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | 95% CI | p | Beta | 95% CI | p-value | Beta | 95% CI | p | Beta | 95% CI | p | |

| CTR | ||||||||||||

| Insufficient therapy | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Intensive therapy | 0.04 | 0.01, 0.06 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.00, 0.06 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.00, 0.06 | 0.051 | 0.03 | 0.00, 0.05 | 0.054 |

| RAA | ||||||||||||

| Insufficient therapy | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Intensive therapy | 6.12 | 0.87, 11.36 | 0.024 | 5.67 | 0.40,10.95 | 0.037 | 6.85 | 1.62, 12.08 | 0.011 | 6.63 | 1.46, 11.80 | 0.013 |

| RVD | ||||||||||||

| Insufficient therapy | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Intensive therapy | 0.65 | 0.33,0.98 | <0.001 | 0.63 | 0.31,0.95 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.35, 0.99 | <0.001 | 0.66 | 0.34, 0.98 | <0.001 |

Association between PAH therapy intensity and compensatory cardiac remodeling (linear regression).

Model I: adjusted for age and gender.

Model II: adjusted for Model I + PAH Classifications.

Model III: adjusted for Model II + PAH Classifications + Cause of death.

PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; CTR, cardiothoracic Ratio; RAA, right atrial area; RVD, mid-cavity right ventricular linear dimension; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that patients with PAH exhibit varying degrees of right heart remodeling in the terminal stage, with extreme cases showing CTR up to 0.88, RAA up to 102 cm2, and RVD up to 7.50 cm. Intensive combination therapy (triple therapy) was significantly associated with more pronounced right heart remodeling compared to monotherapy or double therapy. Specifically, patients receiving triple therapy had larger CTRs, RAAs, and RVDs, as evidenced by both chest x-rays and echocardiography. Linear regression analysis confirmed that the intensity of PAH therapy independently correlated with increased right ventricular remodeling, regardless of age, sex, PAH classification and cause of death.

PAH is a progressive condition characterized by escalating pulmonary vascular resistance, which places an increased afterload on the right heart (2, 18, 19). In response, the right ventricle initially compensates by thickening its walls and enhancing contractility (19, 20). Over time, however, sustained pressure overload can lead to significant right heart enlargement, a process intimately linked to patient survival (21–24). Although extreme cases of right heart remodeling in PAH are rarely documented, our findings indicate a remarkable capacity for structural adaptation, with right atrial areas reaching five to six times the upper limit of normal and right ventricular diameters exceeding twice the normal threshold (25). This degree of remodeling is shaped by an intricate interplay of factors, including neurohormonal activation, coronary perfusion, myocardial metabolism, disease onset rate, underlying etiology, and emerging genetic or epigenetic influences (20, 26, 27). Notably, our findings demonstrate that therapeutic strategies are another significant clinical factor influencing right heart remodeling. While cardiac dimensions are influenced by various confounding factors such as age (28), sex (29), PAH classification (30), and cause of death (31), our analysis demonstrates that even after adjusting for these factors, treatment intensity remains significantly associated with right heart remodeling.

PAH-targeted therapies have been shown to influence right heart remodeling (32–34). Novel agents like sotatercept improve right ventricular structure by reducing pulmonary vascular resistance (35), thereby prolonging the clinical course of PAH. Focusing on the concept of cardiac compensatory limits, our study elucidates the complex relationship between PAH-targeted therapy and right heart remodeling. We found a positive correlation between right heart size and treatment intensity, with significantly greater remodeling observed in patients receiving triple therapy before death compared to those without adequate treatment. Furthermore, the extent of right heart remodeling demonstrated a linear relationship with the duration of PAH management (data not shown). These results suggest that more comprehensive pharmacologic treatment allows for greater cardiac compensation, effectively extending right heart adaptation closer to its functional limits.

Right heart remodeling in PAH presents a complex duality. While the heart's initial remodeling response to increased pulmonary artery pressure is beneficial, enabling it to compensate and prolong survival (19, 36), especially with therapeutic intervention, this adaptive process eventually becomes detrimental. Prolonged remodeling leads to significant right heart enlargement, a key predictor of poor prognosis (37). This creates a critical challenge: While early intervention aims to reverse remodeling, the focus for advanced disease shifts to slowing its progression and maximizing the heart's compensatory capacity.

The emergence of “super-remodelers"—patients exhibiting extreme right heart enlargement despite prolonged PAH-targeted therapy—poses a significant challenge in lung transplantation decisions. While previous research suggests comparable outcomes between bilateral lung transplantation (BLT) and heart-lung transplantation (HLT) (38, 39), the decision-making process becomes more complex for these individuals. Although improved survival rates with PAH medications may be reducing the overall need for lung transplants, the rise of extreme right heart remodeling necessitates a closer look at optimal surgical strategies for this specific patient population. Further research focusing on the potential reversibility of this severe remodeling post-transplant is crucial for refining treatment approaches and determining whether BLT or HLT offers the best long-term outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, the retrospective nature of our study design means that baseline assessments were performed at our center following referral, rather than at initial disease onset. This pre-referral treatment exposure fundamentally limits our ability to establish true baseline cardiac structural characteristics, and completely account for potential confounding effects of prior therapies on subsequent remodeling patterns. These factors may introduce systematic bias in our interpretation of treatment effects. Meanwhile the establishment of causal relationships was still influenced due to retrospective design and confounding by indication (sicker patients receive more therapy). Second, we lacked data on treatment changes over the disease course, hindering analysis of dynamic interactions between evolving treatment strategies and right heart remodeling progression. This prevented us from evaluating the impact of treatment modifications on remodeling over time. Third, cardiac remodeling at the time of death was assessed using chest radiography and echocardiography (40–42). While these modalities are readily available and accepted methods for evaluating right heart structure, the absence of MRI data limited our ability to fully characterize end-stage remodeling, especially in cases with extreme enlargement.

Conclusion

Right heart remodeling in PAH progresses throughout the disease course, culminating in significant changes in the terminal stage. PAH-targeted therapies influence the extent of this cardiac remodeling, effectively pushing the limits of compensatory adaptation. This influence is independent of age, sex, PAH classification, and cause of death. While these therapies enhance the heart's compensatory capacity, allowing it to reach structural extremes, this phenomenon presents a complex duality. The emergence of “super-remodelers,” patients exhibiting extreme right heart enlargement despite prolonged PAH-targeted therapy, underscores the challenges in managing advanced PAH, particularly regarding decisions surrounding lung transplantation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

S-GG: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Q-HZ: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Supervision. J-YZ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis. QZ: Writing – review & editing. RZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. H-LQ: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. C-JL: Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. H-TL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Visualization. W-HW: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. PY: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Visualization. JH: Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JX: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Visualization, Data curation. J-ML: Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Q-HZ: Investigation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization. LW: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Data curation, Project administration, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China 2022YFC2703902 (LW), the National Key Research and Development Program of China 2023YFC2507200 (LW) and Three-Year Action Plan for Promoting Clinical Skills and Clinical Innovation in Municipal Hospitals (SHDC2024CRI065).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Randall PA Heitzman ER Bull MJ Scalzetti EM Williams SK Gordon LP et al Pulmonary arterial hypertension: a contemporary review. Radiographics. (1989) 9:905–27. 10.1148/radiographics.9.5.2678297

2.

Hassoun PM . Pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:2361–76. 10.1056/NEJMra2000348

3.

Kovacs G Bartolome S Denton CP Gatzoulis MA Sue G Khanna D et al Definition, classification and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. (2024) 64(4):2401324. 10.1183/13993003.01324-2024

4.

Dini FL Pugliese NR Ameri P Attanasio U Badagliacca R Correale M et al Right ventricular failure in left heart disease: from pathophysiology to clinical manifestations and prognosis. Heart Fail Rev. (2023) 28(4):757–66. 10.1007/s10741-022-10282-2

5.

Werbner B Tavakoli-Rouzbehani OM Fatahian AN Boudina S . The dynamic interplay between cardiac mitochondrial health and myocardial structural remodeling in metabolic heart disease, aging, and heart failure. J Cardiovasc Aging. (2023) 3(1):9. 10.20517/jca.2022.42

6.

Naeije R Richter MJ Rubin LJ . The physiological basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. (2022) 59(6):2102334. 10.1183/13993003.02334-2021

7.

Chin KM Gaine SP Gerges C Jing ZC Mathai SC Tamura Y et al Treatment algorithm for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. (2024) 64(4):2401325. 10.1183/13993003.01325-2024

8.

Pulido T Adzerikho I Channick RN Delcroix M Galiè N Ghofrani HA et al Macitentan and morbidity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. (2013) 369:809–18. 10.1056/NEJMoa1213917

9.

Galie N Olschewski H Oudiz RJ Torres F Frost A Ghofrani HA et al Ambrisentan for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of the ambrisentan in pulmonary arterial hypertension, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, efficacy (ARIES) study 1 and 2. Circulation. (2008) 117(23):3010–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742510

10.

Galie N Brundage BH Ghofrani HA Oudiz RJ Simonneau G Safdar Z et al Tadalafil therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. (2009) 119(22):2894–903. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.839274

11.

Sastry BK Narasimhan C Reddy NK Raju BS . Clinical efficacy of sildenafil in primary pulmonary hypertension: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2004) 43:1149–53. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.056

12.

Ghofrani HA Galie N Grimminger F Grünig E Humbert M Jing ZC et al Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. (2013) 369(4):330–40. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209655

13.

Simonneau G Barst RJ Galie N Naeije R Rich S Bourge RC et al Continuous subcutaneous infusion of treprostinil, a prostacyclin analogue, in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2002) 165(6):800–4. 10.1164/ajrccm.165.6.2106079

14.

Hoeper MM Badesch DB Ghofrani HA Gibbs JS Gomberg-Maitland M McLaughlin VV et al Phase 3 trial of sotatercept for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388(16):1478–1490. 10.1056/NEJMoa2213558

15.

Humbert M Kovacs G Hoeper MM Badagliacca R Berger RM Brida M et al 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. (2023) 61(1):2200879. 10.1183/13993003.00879-2022

16.

Truszkiewicz K Poreba R Gac P . Radiological cardiothoracic ratio in evidence-based medicine. J Clin Med. (2021) 10(9):2016. 10.3390/jcm10092016

17.

Rudski LG Lai WW Afilalo J Hua L Handschumacher MD Chandrasekaran K et al Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2010) 23(7):685–713; quiz 786–688. 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010

18.

Simonneau G Montani D Celermajer DS Denton CP Gatzoulis MA Krowka M et al Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. (2019) 53(1):1801913. 10.1183/13993003.01913-2018

19.

Vonk Noordegraaf A Westerhof BE Westerhof N . The relationship between the right ventricle and its load in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 69:236–43. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.047

20.

Vonk-Noordegraaf A Haddad F Chin KM Forfia PR Kawut SM Lumens J et al Right heart adaptation to pulmonary arterial hypertension: physiology and pathobiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 62(25 Suppl):D22–33. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.027

21.

Raymond RJ Hinderliter AL Willis PW Ralph D Caldwell EJ Williams W et al Echocardiographic predictors of adverse outcomes in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2002) 39(7):1214–9. 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01744-8

22.

van Wolferen SA Marcus JT Boonstra A Marques KM Bronzwaer JG Spreeuwenberg MD et al Prognostic value of right ventricular mass, volume, and function in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. (2007) 28(10):1250–7. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl477

23.

Vonk Noordegraaf A Chin KM Haddad F Hassoun PM Hemnes AR Hopkins SR et al Pathophysiology of the right ventricle and of the pulmonary circulation in pulmonary hypertension: an update. Eur Respir J. (2019) 53(1):1801900. 10.1183/13993003.01900-2018

24.

Badagliacca R Poscia R Pezzuto B Papa S Reali M Pesce F et al Prognostic relevance of right heart reverse remodeling in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2017):S1053-2498(17)32041-7. 10.1016/j.healun.2017.09.026

25.

Soulat-Dufour L Addetia K Miyoshi T Citro R Daimon M Fajardo PG et al Normal values of right atrial size and function according to age, sex, and ethnicity: results of the World Alliance Societies of Echocardiography Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2021) 34(3):286–300. 10.1016/j.echo.2020.11.004

26.

Voelkel NF Quaife RA Leinwand LA Barst RJ McGoon MD Meldrum DR et al Right ventricular function and failure: report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on cellular and molecular mechanisms of right heart failure. Circulation. (2006) 114(17):1883–91. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632208

27.

Hemnes AR Celermajer DS D'Alto M Haddad F Hassoun PM Prins KW et al Pathophysiology of the right ventricle and its pulmonary vascular interaction. Eur Respir J. (2024) 64(4):2401321. 10.1183/13993003.01321-2024

28.

Henein M Waldenstrom A Morner S Lindqvist P . The normal impact of age and gender on right heart structure and function. Echocardiography. (2014) 31:5–11. 10.1111/echo.12289

29.

Westaby JD Zullo E Bicalho LM Anderson RH Sheppard MN . Effect of sex, age and body measurements on heart weight, atrial, ventricular, valvular and sub-epicardial fat measurements of the normal heart. Cardiovasc Pathol. (2023) 63:107508. 10.1016/j.carpath.2022.107508

30.

Ascha M Renapurkar RD Tonelli AR . A review of imaging modalities in pulmonary hypertension. Ann Thorac Med. (2017) 12:61–73. 10.4103/1817-1737.203742

31.

Tonelli AR Arelli V Minai OA Newman J Bair N Heresi GA et al Causes and circumstances of death in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2013) 188(3):365–9. 10.1164/rccm.201209-1640OC

32.

Vonk Noordegraaf A Channick R Cottreel E Kiely DG Marcus JT Martin N et al The REPAIR study: effects of macitentan on RV structure and function in pulmonary arterial hypertension. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2022) 15(2):240–53. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2021.07.027

33.

Zhao QH Chen J Chen FD Ruan HY Zhang W Zhou YL et al Evaluating the efficacy and safety of oral triple sequential combination therapy for treating patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a multicenter retrospective study. Pulm Circ. (2024) 14(1):e12351. 10.1002/pul2.12351

34.

D'Alto M Badagliacca R Argiento P Romeo E Farro A Papa S et al Risk reduction and right heart reverse remodeling by upfront triple combination therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. (2020) 157(2):376–83. 10.1016/j.chest.2019.09.009

35.

Souza R Badesch DB Ghofrani HA Gibbs JS Gomberg-Maitland M McLaughlin VV et al Effects of sotatercept on haemodynamics and right heart function: analysis of the STELLAR trial. Eur Respir J. (2023) 62(3):2301107. 10.1183/13993003.01107-2023

36.

Todaro MC Carerj S Zito C Trifirò MP Consolo G Khandheria B et al Echocardiographic evaluation of right ventricular-arterial coupling in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. (2020) 10(4):272–83.

37.

Dardi F Boucly A Benza R Frantz R Mercurio V Olschewski H et al Risk stratification and treatment goals in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. (2024) 64(4):2401323. 10.1183/13993003.01323-2024

38.

Brouckaert J Verleden SE Verbelen T Coosemans W Decaluwé H Leyn PD et al Double-lung versus heart-lung transplantation for precapillary pulmonary arterial hypertension: a 24-year single-center retrospective study. Transpl Int. (2019) 32(7):717–29. 10.1111/tri.13409

39.

Savale L Benazzo A Corris P Keshavjee S Levine DJ Mercier O et al Transplantation, bridging, and support technologies in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. (2024) 64(4):2401193. 10.1183/13993003.01193-2024

40.

Remy-Jardin M Ryerson CJ Leung AN Wild JM Hoeper MM Schiebler ML et al Imaging of pulmonary hypertension in adults: a position paper from the Fleischner Society. Eur Respir J. (2021) 57(1):2004455. 10.1183/13993003.04455-2020

41.

Farber HW Foreman AJ Miller DP McGoon MD . REVEAL Registry: correlation of right heart catheterization and echocardiography in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Congest Heart Fail. (2011) 17:56–64. 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00202.x

42.

Fisher MR Forfia PR Chamera E Housten-Harris T Champion HC Girgis RE et al Accuracy of Doppler echocardiography in the hemodynamic assessment of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2009) 179(7):615–21. 10.1164/rccm.200811-1691OC

Summary

Keywords

pulmonary arterial hypertension, death, right heart remodeling, treatment intensity, targeted therapies

Citation

Gong S-G, Zhang Q-H, Zhang J-Y, Zhang Q, Zhang R, Qiu H-L, Luo C-J, Li H-T, Wu W-H, Yuan P, He J, Xu J, Liu J-M, Zhao Q-H and Wang L (2025) Right heart remodeling in end-stage pulmonary arterial hypertension and the impact of treatment intensity. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1643983. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1643983

Received

09 June 2025

Accepted

29 August 2025

Published

26 September 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Jiafu Ou, Washington University in St. Louis, United States

Reviewed by

Vladimir Uspenskiy, Almazov National Medical Research Centre, Russia

Tengteng Zhu, Central South University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Gong, Zhang, Zhang, Zhang, Zhang, Qiu, Luo, Li, Wu, Yuan, He, Xu, Liu, Zhao and Wang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Lan Wang lanwang@tongji.edu.cn Qin-Hua Zhao zhaoqinhua2014@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

ORCID Qin-Hua Zhao orcid.org/0000-0003-4309-8880 Lan Wang orcid.org/0000-0002-7270-1397

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.