Abstract

Atherosclerosis, driven primarily by cumulative exposure to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), is the major cause of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). This narrative review examines the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, linking risk factors, inflammatory pathways, and lipid abnormalities to the formation and progression of atheromatous plaques. Plaque characteristics such as volume, lipid content, fibrous cap thickness, and minimum lumen area are closely associated with cardiovascular outcomes, particularly the risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACEs). Intensive LDL-C lowering through statins, ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, and emerging agents like bempedoic acid has demonstrated clear benefits in regressing plaques, stabilizing their morphology, and significantly reducing cardiovascular risks. Despite guideline recommendations advocating intensive lipid-lowering strategies, real-world practice reveals considerable gaps, with many high- and very-high-risk patients failing to achieve LDL-C targets. Contributing factors include poor adherence, underuse of combination therapies, and treatment inertia. Early detection and preemptive management of subclinical atherosclerosis, particularly among younger individuals, are gaining attention as strategies to intercept the progression of disease before clinical events occur. Moreover, elevated lipoprotein(a) levels are increasingly recognized as an independent causal factor for ASCVD, and ongoing trials are evaluating specific Lp(a)-lowering therapies. Overall, optimizing lipid management through intensive, early intervention, patient adherence, and personalized treatment approaches holds the key to reducing the global burden of ASCVD. Addressing residual risks and refining early detection strategies will further advance the prevention and management of this chronic, progressive vascular disease.

1 Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic disease originating from deposition of atheromatous plaques inside arterial walls, leading to lumen stenosis and hardening of arteries. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is a causal and cumulative factor in the development of atherosclerosis and subsequent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) (1, 2). This narrative review describes the role of atherosclerotic plaque in the onset of ASCVD, relationship between LDL-C level, plaque characteristics, and cardiovascular outcomes as well as clinical implications from the interrelation. However, discrepancy exists between guideline-recommended LDL-C targets and real-world practice for primary and secondary prevention of ASCVD (2). This review also reveals challenges in real-world lipid management and looks forward to optimal atherosclerotic management, suggesting that early detection and treatment of subclinical atherosclerosis at younger age or intensive lipid-lowering strategy is necessary to reduce ASCVD risks.

2 Atherosclerosis

2.1 Pathogenesis and risk factors

The pathogenic process of atherosclerosis begins with endothelial cell dysfunction, leading to the accumulation and oxidation of LDL-C particles, activation of endothelial cells, and recruitment of monocytes into the intima. In the early stage of atherogenesis, macrophages differentiated from bound monocytes engulf the oxidized LDL and form foam cells. Immune cells such as T cells also contribute to the progression of fatty streak formation. Subsequently, smooth muscle cells from the media migrate and proliferate in the intima, the extracellular matrix such as collagen degrades, and necrosis and calcification develop, resulting in reduced stability of atherosclerotic plaques and eventual rupture (3). Finally, platelets become activated and thrombus formation occurs in the advanced stage of atherosclerosis (3, 4).

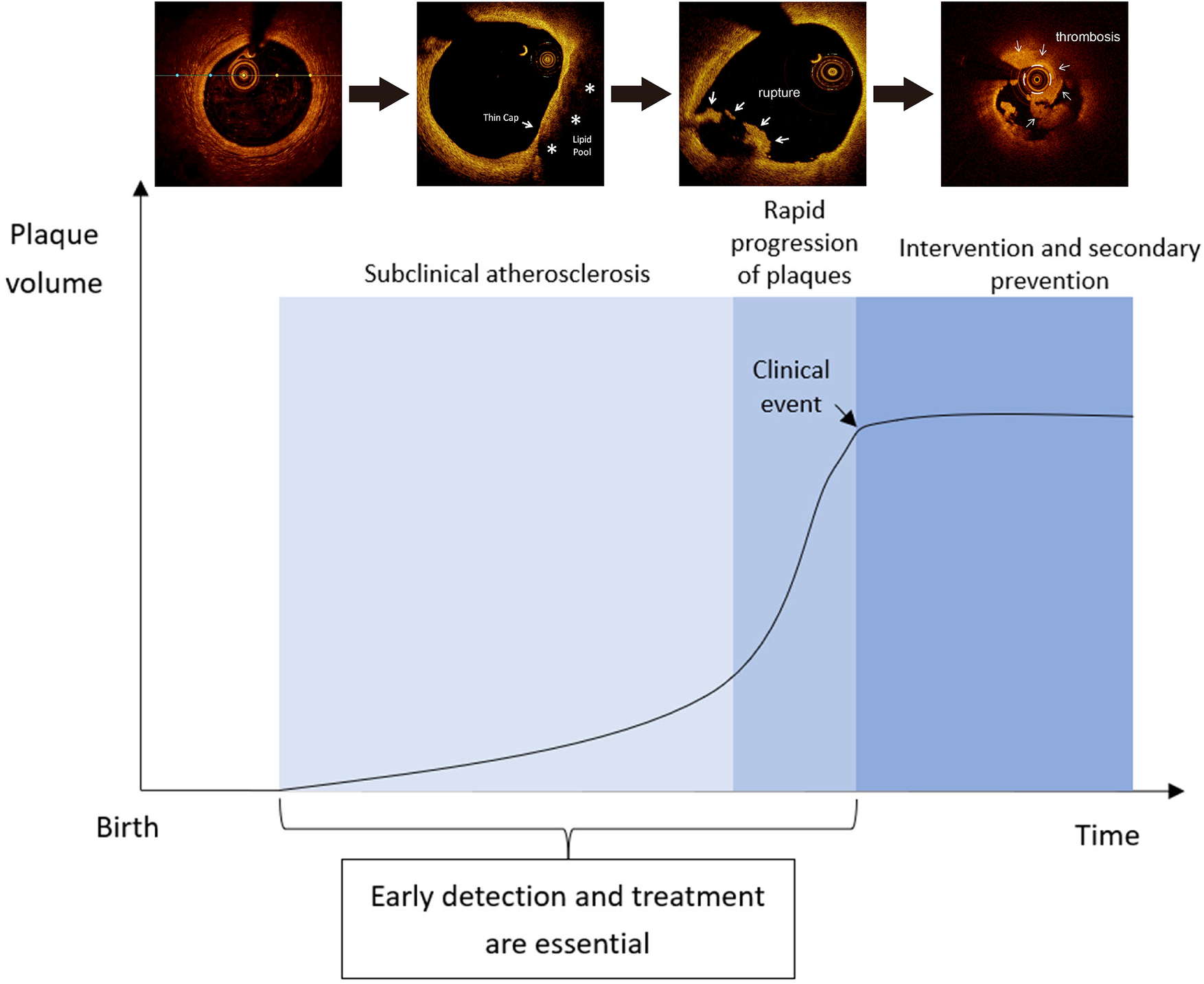

Oxidized LDL has conventionally been considered as the primary driver of atherogenesis; however, recent evidence suggests that aggregated LDL associated with proteoglycan, or adaptive immune responses to native LDL, may also be involved in the mechanisms of plaque formation (5). Another factor linked to atherosclerosis is inflammation. Studies have shown that angiotensin II and adaptive T cell immunity, which participate in the pathogenesis of hypertension, can also provide inflammatory pathways for atherosclerosis (6). Biomarkers of inflammation, especially C-reactive protein, are increasingly deemed as predictors of cardiovascular risk (6). It was shown in randomized controlled trial setting that interleukin-1β inhibition in patients with history of myocardial infarction and raised high-sensitive C-reactive protein may potentially reduce subsequent cardiovascular events (7). Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential, which refers to age-related clonal expansion of blood stem cells with mutations linked to hematologic cancers, is a novel risk factor for inflammation-mediated atherosclerosis and adverse cardiovascular outcomes (6, 8). Microplastics and nanoplastics are also emerging as a potential risk factor for atherosclerosis through activating inflammatory pathways (9). Exposure to the above risk factors may alter the homeostatic properties of the endothelial monolayer, facilitating the initiation of atherogenesis (6). Continued accumulation of lipid and lipid-engorged cells allows the progression of atherosclerotic plaques, many of which will further develop calcification due to dysregulated deposition and impaired clearance of lipids, leading to the potential for rupture and thrombosis (Figure 1) (10, 11).

Figure 1

Histological features of atherosclerosis at different stages (11).

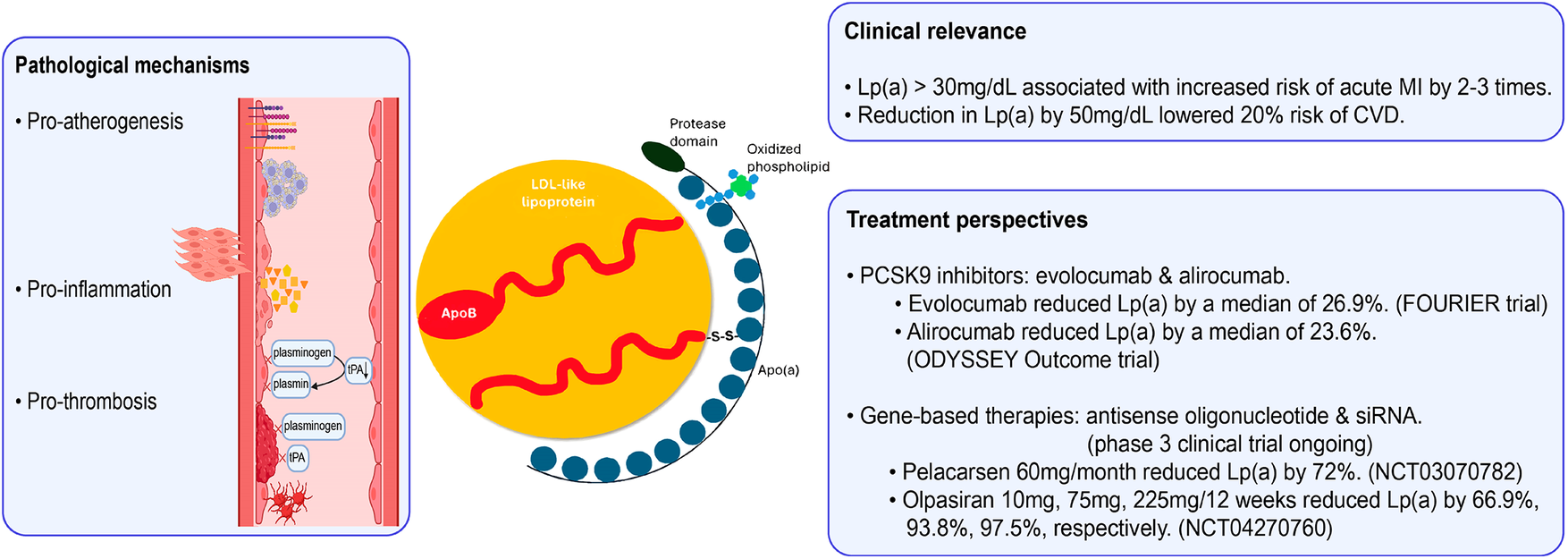

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] has been increasingly recognized to be a contributor to the development of atherosclerosis via several proposed mechanisms (Figure 2) (12). First, Lp(a) may have a pro-atherogenic effect, stimulating the formation of foam cells, proliferation of smooth muscle cells, and production of adherence molecules in endothelial cells of arteries (13). Second, it competes with plasminogen for binding sites on endothelial cells, resulting in antifibrinolytic and pro-thrombotic effects (14). Third, Lp(a) may stimulate inflammatory cytokines, which include interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, possibly increasing the risk of inflammation and thus atherosclerosis (15). Recent research suggests that, although the underlying pathophysiology is not fully understood, an increase in Lp(a) level is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD) (12).

Figure 2

Role of lipoprotein(a) in the atherosclerotic process (12). Apo(a), apolipoprotein(a); ApoB, apolipoprotein B; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha. Created using Biorender.

2.2 Plaque characteristics and cardiovascular events

Once established, atherosclerotic plaques continue to encroach upon the arterial lumen, leading to the formation of flow-limiting lesions and ischemia, and subsequently plaque rupture (10), which is the most common cause of acute thrombosis of coronary arteries leading to myocardial infarction (MI) (16, 17). Recent studies using serial angiographic data demonstrated that progression of atherosclerotic plaques can be rapid, possibly due to plaque disruption and subsequent thrombotic organization shortly (i.e., within 1–3 months) before the onset of an acute clinical event, such as MI (18, 19). Thus, early detection and treatment of subclinical atherosclerosis at a younger age have been increasingly emphasized to modify plaque progression, reduce rupture, and prevent atherosclerotic clinical events (18).

A number of studies using coronary angiography (Table 1) revealed that plaque progression in terms of luminal stenosis shortly before or at the onset of an acute MI, recurrent MI, or major adverse cardiac event (MACE, which is generally defined as the composite of cardiac death, non-fatal MI, unstable angina, or coronary revascularization) (20–24). One study in Japan demonstrated the process of plaque progression in coronary artery disease using four serial coronary arteriograms within 1 year (25). Among 36 patients, 14 (39%) had vessels with marked plaque progression and a sudden surge in the mean stenosis observed from the third (46 ± 13%) to the fourth arteriogram (88 ± 10%); 71% of these patients sustained acute coronary syndrome (25). In contrast, only three (14%) of the 22 patients with gradual progression of stenosis throughout four arteriograms had an acute coronary event (25). Taken together, current coronary angiography studies suggest that rapid, substantial plaque progression is a critical predictor of plaque rupture and subsequent MI or other MACEs.

Table 1

| Study | No. of patients/lesions | Time of measurement | Mean (SD) diameter stenosis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ojio et al. (20) | 20 | 6–18 months before MI | 30 (18) |

| 20 | ≤1 week before MI | 71 (12) | |

| Glaser et al. (21) | 157 | At the time of initial PCI | 41.8 (20.8) |

| At the onset of a recurrent event (follow-up, 1 year) | 83.9 (13.9) | ||

| PROSPECT (22) | 74 | Baseline | 32.3 (20.6) |

| At the onset of a MACE (median follow-up, 3.4 years) | 65.4 (16.3) | ||

| Zaman et al. (23) | 34 | >3 months before MI | 36.5 (20.6) |

| 7 | ≤3 months before MI | 59.1 (31.5) | |

| PROSPECT II (24) | 66 | Baseline | 46.9 (15.9) |

| At the onset of a MACE (median follow-up, 3.7 years) | 68.4 (17.7) |

Coronary angiography studies on changes in luminal stenosis from atherosclerosis to an acute event.

MACE, major adverse cardiac event; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SD, standard deviation.

In addition to stenosis, features of plaque morphology, such as plaque burden, minimum lumen area (MLA), fibrous cap thickness (FCT), lipid burden, and lipid arc, have also been shown to be associated with the risk of MACEs in multiple studies using optical coherence tomography (OCT), intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), or near-infrared spectroscopy (Table 2) (22, 24, 26–28). In the PROSPECT study (22), a plaque burden ≥70% (hazard ratio [HR], 5.03; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.51–10.11; P < 0.001), an MLA ≤4.0 mm2 (HR, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.61–6.42; P = 0.001), and a classification of thin-cap fibroatheromas (TCFAs; HR, 3.35; 95% CI, 1.77–6.36; P < 0.001) were significant risk factors for recurrent MACEs related to non-culprit lesions. The LRP study (26) showed that each 100-unit increase in the maximum 4-mm Lipid Core Burden Index (maxLCBI4 mm) significantly elevated the risk of non-culprit MACEs, with unadjusted and adjusted HRs on a patient level 1.21 (95% CI, 1.09–1.35; P = 0.0004) and 1.18 (95% CI, 1.05–1.32; P = 0.0043), respectively; and unadjusted HR on a lesion level 1.45 (95% CI, 1.30–1.60; P < 0.0001) (26). Likewise, the PROSPECT II study (24) showed that a high lipid burden (maxLCBI4 mm ≥ the upper quartile of all non-culprit lesions) and a large plaque burden (≥70%) were independent predictors of non-culprit MACEs (24). In the CLIMA study (27) of 1,776 non-culprit plaques, an MLA <3.5 mm2 (HR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.0), FCT <75 mm (HR, 4.7; 95% CI, 2.4–9.0), lipid arc circumferential extension >180° (HR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.2–4.8), and the presence of OCT-defined macrophages (HR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.2–6.1) were associated with an elevated risk of cardiac death or target segment MI (27). The recent COMBINE OCT-FFR study (28) provided further insights into the classification of lipid-rich plaque (LRP) lesions that increased the risk of MACEs. LRP lesions were associated with a higher risk of MACEs (HR, 3.9; 95% CI, 0.9–16.5; log-rank P = 0.049) than non-LRP lesions; however, TCFAs, which accounted for one-third of LRP lesions, had a significantly higher risk of MACEs compared with thick-cap fibroatheromas (ThCFAs; HR, 3.8; 95% CI, 1.5–9.5; P < 0.01) as well as non-LRP lesions (HR, 7.7; 95% CI, 1.7–33.9; P < 0.01) (25). ThCFAs and non-LRP lesions were not significantly different in terms of the risk of MACEs (HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 0.42–9.7; P = 0.38) (28).

Table 2

| Study | No. of patients | Follow-up (months) | Primary endpoint | Imaging tool | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROSPECT (22) | 697 | 40.8 | Culprit and non-culprit MACEs | IVUS | Plaque burden ≥70% (vs. <70%), MLA ≤4.0 (vs. >4.0 mm2), and TCFA (vs. ThCFA) were significant risk factors for recurrent MACEs related to non-culprit lesions |

| LRP (26) | 1271 | 24 | Non-culprit MACEs | NIRS-IVUS | Each 100-unit increase in maxLCBI4mm significantly elevated the risk of non-culprit MACEs |

| CLIMA (27) | 1,003 | 12 | Cardiac death and target segment MI | OCT | MLA <3.5 (vs. ≥3.5 mm2), FCT <75 (vs. ≥75 µm), lipid arc circumferential extension >180° (vs. ≤180°), and the presence of OCT-defined macrophages were associated with an elevated risk of cardiac death or target segment MI |

| PROSPECT II (24) | 898 | 44.4 | Non-culprit MACEs | NIRS-IVUS | MaxLCBI4 mm ≥ 324.7 (vs. <324.7) and plaque burden ≥70% (vs. <70%) were independent predictors of non-culprit MACEs |

| COMBINE OCT-FFR (28) | 390 | 18 | Non-culprit MACEs | OCT + FFR | LRP (vs. non-LRP) lesions were associated with a higher risk of MACEs; LRP-TCFA (FCT ≤65 µm; lipid arc >90°) had a significantly higher risk of MACEs vs. LRP-ThCFA (FCT >65 µm) and non-LRP lesions; ThCFAs and non-LRP lesions were not significantly different in terms of the risk of MACEs |

Characteristics of selected studies that investigated relationships between plaque morphology and the risk of cardiac events.

FCT, fibrous cap thickness; FFR, fractional flow reserve; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LRP, lipid-rich plaque; MACE, major adverse cardiac event; maxLCBI4 mm, maximum 4 mm Lipid Core Burden Index; MI, myocardial infarction; MLA, minimum lumen area; NIRS, near-infrared spectroscopy; OCT, optical coherence tomography; TCFA, thin-cap fibroatheroma; ThCFA, thick-cap fibroatheroma.

3 Management of atherosclerosis

Lipid-lowering therapy targeting reductions in LDL-C levels remains the primary medicinal intervention for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Statins are the most widely used lipid-lowering agents. Ezetimibe (29) and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors (30, 31) are feasible treatment options to further reduce LDL-C levels. Bempedoic acid is a recently developed lipid-lowering agent that can be used in statin-intolerant patients (32). The sections below discuss the clinical data on relationships between reductions in LDL-C levels with lipid-lowering therapies, the morphology of coronary atherosclerotic plaques, and the risk of cardiovascular disease.

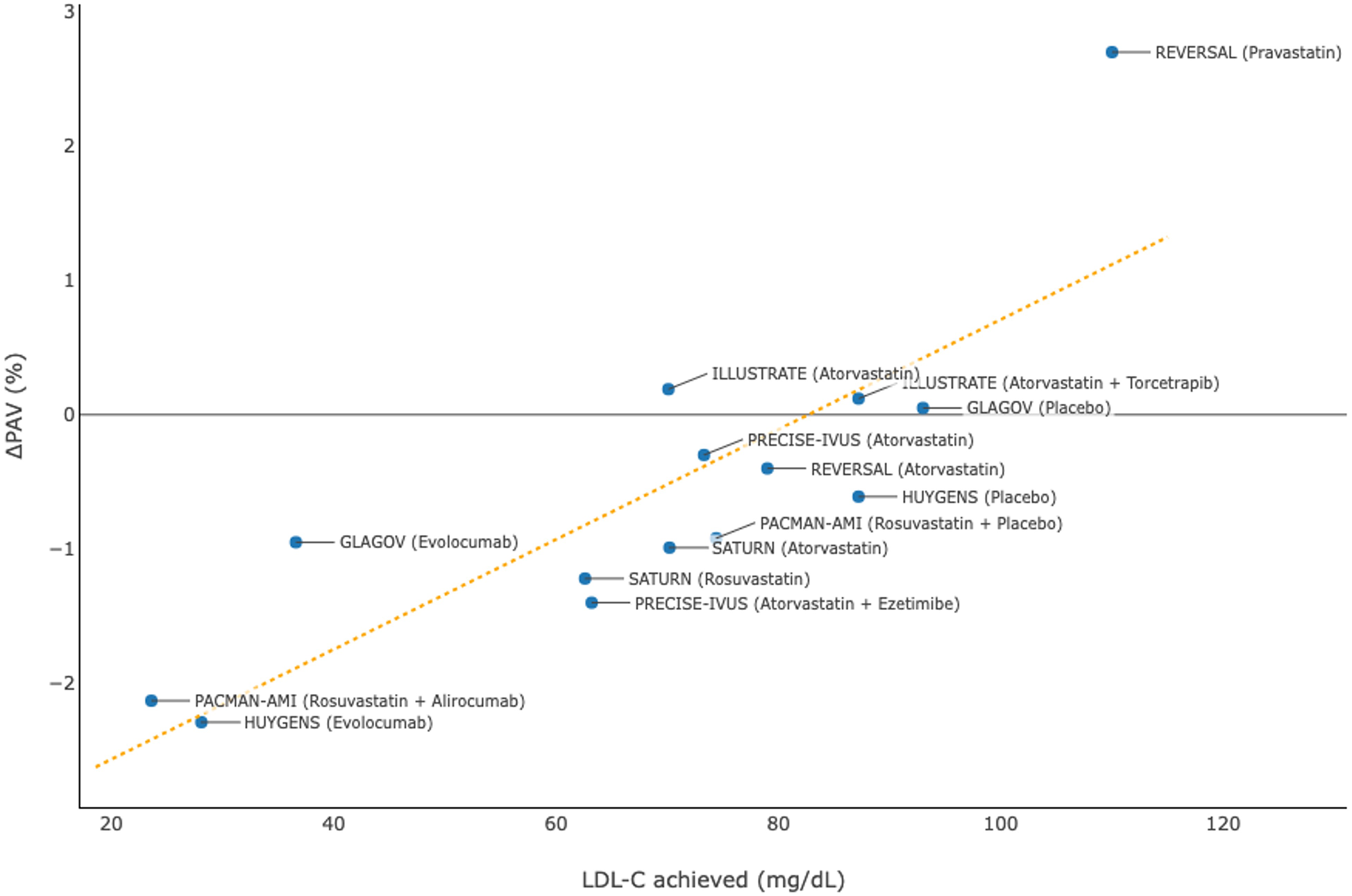

3.1 Correlation between achieved LDL-C levels and plaque characteristics

Multiple clinical studies (29–31, 33–37) have been conducted to investigate the effects of intensive lipid-lowering therapies, including high-dose statins and PCSK9 inhibitors, on reducing the progression of atherosclerotic plaques among patients with coronary artery disease (at least one vessel with stenosis ≥20%; target segment with stenosis ≤50%) using IVUS imaging (Table 3). Clinical trial results were identified from PubMed and pooled data from these studies demonstrated that a lower level of achieved LDL-C was associated with more substantial regression of atherosclerotic plaques in terms of percent atheroma volume (Figure 3).

Table 3

| Study | No. of patients | Follow-up (months) | Study arm | Comparator arm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | LDL-C (mg/dl) | Change in PAV (%) | Treatment | LDL-C (mg/dl) | Change in PAV (%) | |||

| REVERSAL (33) | 502 | 18 | Atorvastatin | 79 | +0.6 | Pravastatin | 110 | +1.9 |

| ILLUSTRATE (35) | 910 | 24 | Atorvastatin + Torcetrapib | 70.1 | +0.12 | Atorvastatin | 87.2 | +0.19 |

| SATURN (36) | 1,039 | 24 | Rosuvastatin | 62.6 | −1.22 | Atorvastatin | 70.2 | −0.99 |

| PRECISE-IVUS (29) | 202 | 9–12 | Atorvastatin + Ezetimibe | 63.2 | –1.4 | Atorvastatin | 73.3 | –0.3 |

| GLAGOV (37) | 968 | 19 | Evolocumab | 36.6 | –0.95 | Placebo | 93.0 | +0.05 |

| HUYGENS (30) | 161 | 12 | Evolocumab | 28.1 | –2.29 | Placebo | 87.2 | –0.61 |

| PACMAN-AMI (31) | 300 | 12 | Rosuvastatin + Alirocumab | 23.6 | –2.13 | Rosuvastatin + Placebo | 74.4 | –0.92 |

Prospective and randomized trials on the effects of intensive lipid-lowering therapies on the regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaques using intravascular ultrasonography.

LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PAV, percent atheroma volume.

Figure 3

Association between achieved levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and change in percent atheroma volume (PAV) in clinical trials using intravascular ultrasonography.

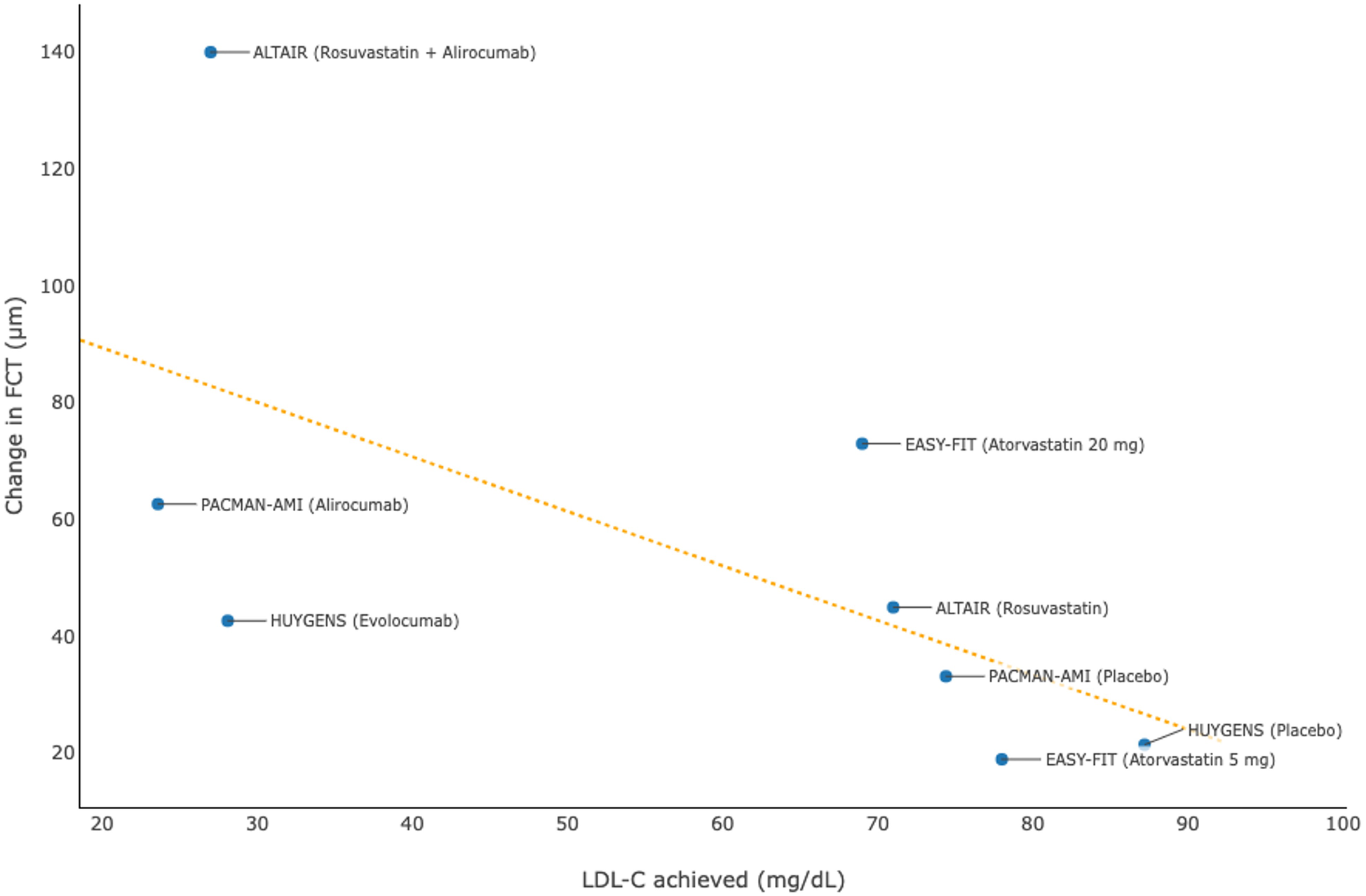

Studies using OCT (30, 31, 38–40) also showed that intensive lipid-lowering therapies were associated with favorable changes in plaque composition and microstructure, which included evaluation of FCT, lipid burden, MLA, and macrophage accumulation among patients with acute coronary syndrome (Table 4). The aggregated evidence, particularly from the HUYGENS (30) and PACMAN-AMI (31) studies on PCSK9 inhibitors, revealed that a lower level of LDL-C achieved was associated with a more marked increase in FCT (Figure 4), suggesting a higher degree of stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques.

Table 4

| Study | No. of patients | Follow-up (months) | Study arm | Comparator arm | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | LDL-C achieved (mg/dl)a | Change in FCT (µm) | Change in lipid burden (degree) | Change in MLA (mm2) | Macrophage accumulationb | Treatment | LDL-C achieved (mg/dl)a | Change in FCT (µm) | Change in lipid burden (degree) | Change in MLA (mm2) | Macrophage accumulationb | |||

| EASY-FIT (38) | 60 | 12 | Atorvastatin 20 mg qd | 69 | +73 | −50 | −0.05 | −4.5 | Atorvastatin 5 mg qd | 78 | +19 | −10 | −0.09 | −2.0 |

| ALTAIR (40) | 24 | 9 | Rosuvastatin + Alirocumab | 27 | +140 | −26.2% (lipid index) | NR | −28.4 | Rosuvastatin | 71 | +45 | −2.8% (lipid index) | NR | −10.2 |

| HUYGENS (30) | 161 | 12 | Evolocumab | 28.1 | +42.7 | −57.5 | NR | −3.17 | Placebo | 87.2 | +21.5 | −31.4 | NR | −1.45 |

| PACMAN-AMI (31) | 300 | 12 | Alirocumab | 23.6 | +62.67 | −79.42 (LCBI) | NR | −25.98 | Placebo | 74.4 | +33.19 | −37.60 (LCBI) | NR | −15.95 |

Prospective and randomized trials on the effects of intensive lipid-lowering therapies on the stabilization of coronary plaques using optical coherence tomography.

FCT, fibrous cap thickness; LCBI, Lipid Core Burden Index (maximum 4-mm); MLA, minimum lumen area; NR, not reported; qd, once daily.

Median levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were reported in the EASY-FIT and ALTAIR studies; mean levels of LDL-C were reported in the HUYGENS and PACMAN-AMI studies.

Accumulation grades were reported in EASY-FIT and ALTAIR; data on angular extension were reported in PACMAN-AMI; macrophages indexes were reported in HUYGENS.

Figure 4

Association between achieved levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and change in fibrous cap thickness (FCT) in clinical trials using optical coherence tomography.

Taken together, clinical trials using IVUS and OCT have consistently shown that intensive reductions in LDL-C levels are associated with regression and stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques in patients with CHD.

Although we must acknowledge potential limitations of using imaging as a surrogate endpoint, such as imperfect correlation with clinical outcomes and measurement variability, it remains a valuable tool for assessing structural changes and providing insight into plaque progression in the process of atherosclerosis.

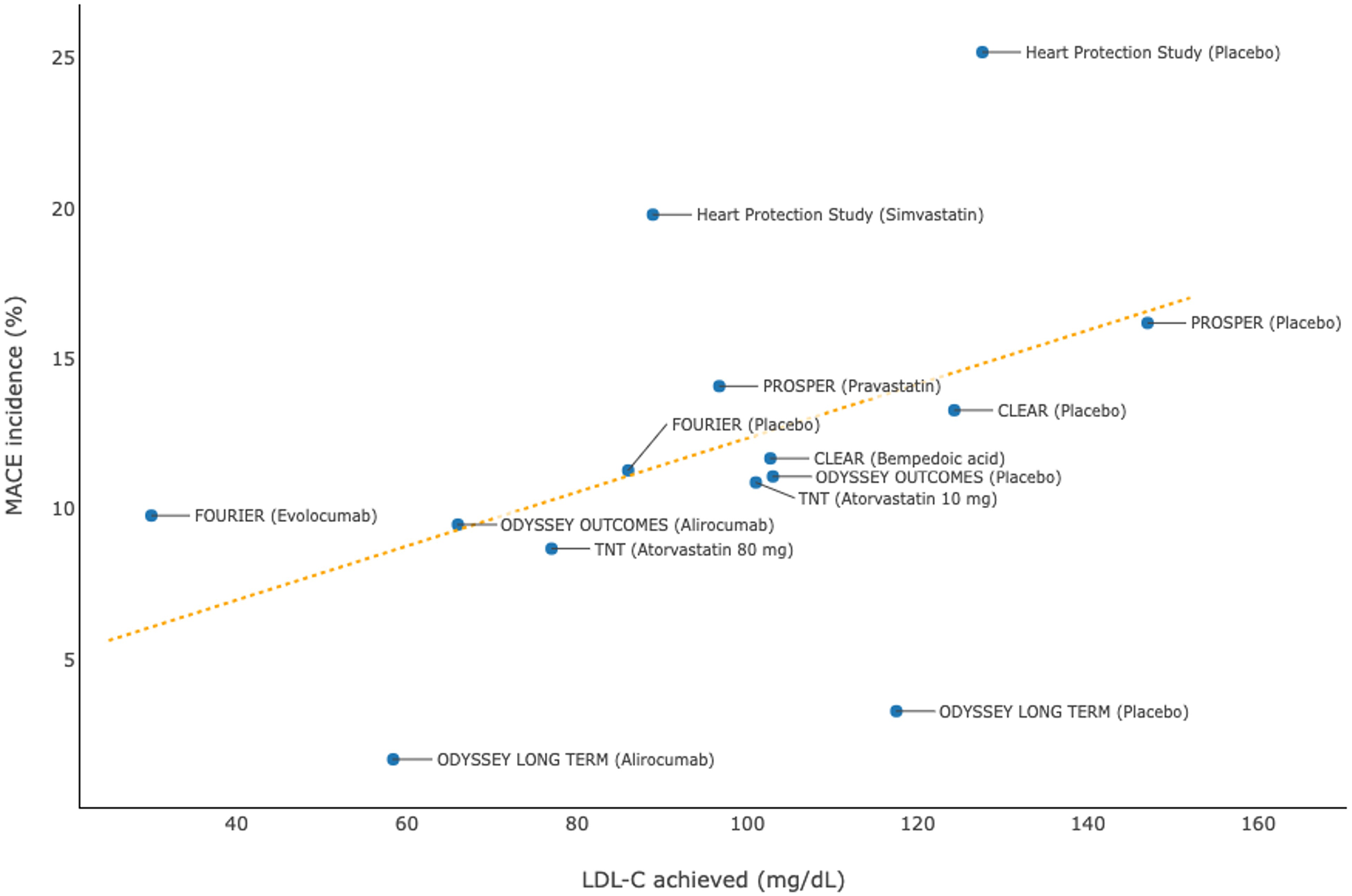

3.2 Correlation between achieved LDL-C levels and cardiovascular outcomes

A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 17 prospective studies of dyslipidemia therapies showed that a 1% decrease in the mean percent atheroma volume resulted from these treatments was associated with a 20% reduction in the risk of MACEs (adjusted odds ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70–0.95; P = 0.011) (41). In line with the beneficial effects on modifying the morphology of atherosclerotic plaques, intensive lipid-lowering therapies significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease among patients with or without a history of CHD. A number of large-scale, long-term randomized controlled trials (Table 5) demonstrated that intensive reductions in levels of LDL-C using high-dose statins, PCSK9 inhibitors, or bempedoic acid significantly reduced the risk of first-onset or recurrent MACEs, which were generally referred to as the composite of cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, unstable angina, or coronary revascularization (32, 42–50). Pooled data from each randomized treatment arm showed that a lower level of LDL-C achieved was strongly associated with a lower incidence of MACEs (Figure 5). Likewise, greater absolute reductions in LDL-C levels resulted from intensive lipid-lowering therapies compared with controls were associated with more substantial reductions in the relative risk of MACEs (i.e., lower HRs were reported in the randomized controlled trials), suggesting that there is a dose-dependent effect of LDL-C reduction on lowering the cardiovascular risk, regardless of the history of CHD (32, 42–50).

Table 5

| Study | Level of prevention | No. of patients | Follow-up (years)a | Study arm | Comparator arm | Absolute reduction in LDL-C (mg/dl) | Relative risk reduction in MACE (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | LDL-C achieved (mg/dl)b | MACE incidence (%)c | Treatment | LDL-C achieved (mg/dl)b | MACE incidence (%)c | ||||||

| PROSPER (42) | Secondary | 5,804 | 3.2 | Pravastatin | 96.7 | 14.1 | Placebo | 146.5 | 16.2 | 49.8 | 15 |

| Heart Protection Study (43) | Secondary | 20,536 | 4.8–5.0 | Simvastatin | 88.9 | 19.8 | Placebo | 127.6 | 25.2 | 38.7 | 24 |

| TNT (44) | Secondary | 10,001 | 4.9 | Atorvastatin 80 mg qd | 77.0 | 8.7 | Atorvastatin 10 mg qd | 101.0 | 10.9 | 24.0 | 22 |

| JUPITER (45) | Primary | 17,802 | 1.9 | Rosuvastatin | 55.0 | 1.6 | Placebo | 109.0 | 2.8 | 54.0 | 44 |

| ODYSSEY LONG TERM (46) | Secondary | 2,341 | 1.5 | Alirocumab | 58.4 | 1.7 | Placebo | 117.5 | 3.3 | 59.1 | 48 |

| HOPE-3 (47) | Primary | 12,705 | 5.6 | Rosuvastatin | 95.0 | 4.4 | Placebo | 124.5 | 5.7 | 29.5 | 25 |

| OSLER (48) | Primary | 4,465 | ∼1.0 | Evolocumab + SOC | 48.0 | 1.0 | SOC | Not reported | 2.2 | 73.0d | 53 |

| FOURIER (49) | Secondary | 27,564 | 2.2 | Evolocumab | 30.0 | 9.8 | Placebo | Not reported | 11.3 | 56.0d | 15 |

| ODYSSEY OUTCOMES (50) | Secondary | 18,924 | 2.8 | Alirocumab | 66.0 | 9.5 | Placebo | 103.0 | 11.1 | 37.0 | 15 |

| CLEAR (32) | Secondary | 13,970 | 3.4 | Bempedoic acid | 102.7 | 11.7 | Placebo | 124.3 | 13.3 | 21.6 | 13 |

Randomized controlled trials on the efficacy of intensive lipid-lowering therapies in reducing the cardiovascular risk in high-risk patients (primary prevention) or patients with a history of coronary heart disease (secondary prevention).

qd, once daily; SOC, standard of care.

Mean durations of follow-up were reported in the PROSPER, Heart Protection, and ODYSSEY LONG TERM studies; the remaining studies reported median durations of follow-up.

Median levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were reported in the JUPITER, OSLER, and FOURIER studies; the remaining studies reported mean levels of LDL-C.

A major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) was generally defined as the composite of cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, unstable angina, or coronary revascularization.

In OSLER and FOURIER, reductions in LDL-C were means, whereas achieved LDL-C levels were medians.

Figure 5

Association between achieved levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and incidences of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs): pooled data from randomized controlled trials.

3.3 Guideline recommendations for intensive lipid-lowering treatment

In a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) (4), LDL-C is recognized as both a causal and a cumulative factor for the initiation and progression of ASCVD. The lower the LDL-C level achieved with lipid-lowering agents, the greater the clinical benefit amassed (4). Both relative and absolute risk reduction in major cardiovascular events resulting from lowering LDL-C will depend on a patient's baseline LDL-C level, the absolute magnitude of LDL-C reduction, and the duration of lipid-lowering treatment (4).

More recently, the guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia established jointly by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the EAS have articulated the dose-dependent effect of LDL-C-lowering agents on reducing the risk of ASCVD (51). The guidelines have also highlighted that the primary goal of targeted lipid management is to reduce atherosclerotic risk by markedly lowering LDL-C to levels that were attained in randomized controlled trials of PCSK9 inhibitors. In patients at high or very high cardiovascular risk, reducing LDL-C to as low a level as possible or a minimum 50% reduction from the baseline LDL-C level, along with achieving the tailored goal is suggested (51).

To achieve the ESC/EAS-recommended goals for LDL-C in patients at very high cardiovascular risk, even treatment with high-dose statins is often insufficient (52). Ray et al. proposed that the treatment paradigm for these patients should be shifted from an “intensive statin therapy first” approach to an “intensive lipid-lowering combination therapy” approach using ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor as an adjunct agent to facilitate effective LDL-C lowering and thus cardiovascular risk reduction (52).

4 Barriers to real-world lipid management

4.1 Discrepancy between guideline recommendations and routine clinical practice

In view of the evidence-based cardioprotective benefits, intensive LDL-C–lowering therapy has been recommended for patients at risk of ASCVD (4, 51). However, achieving and maintaining guideline-recommended LDL-C goals in real-world practice remains a therapeutic challenge. A retrospective cohort study in the U.S. revealed that nearly 50% of patients aged ≥65 years discontinued statin treatment within the first year of the initial prescription, with a substantial decline in the adherence rate over time (53). Real-world clinical data from Germany (54) and Poland (55) showed that only 20% of very high-risk patients attained the LDL-C goal of <1.8 mmol/L as recommended by the ESC/EAS at the time of the studies. More recently, the cross-sectional DA VINCI study conducted in 18 European countries found that only 25% and 11% of individuals at high risk and very high risk, respectively, achieved the LDL-C targets for primary prevention, and that only 18% of patients with established ASCVD attained the LDL-C goals (56).

4.2 Possible reasons for not achieving the target LDL-C level

There are several possible reasons behind the failure to achieve guideline-recommended LDL-C goals. Non-adherence to lipid-lowering treatment is one major obstacle. Muscle symptoms, such as myalgia, are the most frequent adverse event (AE) that interrupts statin therapy (10). Other factors, such as patient education, complexity of treatment regimens, availability of drugs, reimbursement policies, and physician practice, also affect patient adherence (58). Another obstacle is the low use of guideline-recommended combination therapy for high- and very high-risk patients. The DA VINCI study (56) showed that moderate-intensity statin monotherapy was the most commonly used regimen for primary prevention of ASCVD in patients at high risk (64%) and very high risk (69%). Across all risk categories, merely 9% of patients received ezetimibe in combination with a statin, and 1% of patients received a PCSK9 inhibitor with a statin and/or ezetimibe (56).

Some clinicians and patients have concern about the safety of achieving “extremely low” LDL-C (59). Post-hoc analysis of randomized controlled trials involving PCSK9 inhibitors revealed no increased risk of new or recurrent cancer, cataract-related adverse events, hemorrhagic stroke, new-onset diabetes, neurocognitive adverse events, muscle-related events, or non-cardiovascular death, were found in patients with LDL-C <0.5 mmol/L (60).

4.3 Optimizing the management of ASCVD

The benefits of intensive LDL-C–lowering observed in clinical trials will only materialize in real-world practice if patients adhere to treatment. Patients who are suspected to have statin intolerance should consider careful statin re-challenge, because continued statin use after experiencing an AE remains effective in reducing the risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality, especially in high-risk patients (61–63). Lipid-lowering combination therapy should be promoted to facilitate the attainment of guideline-recommended LDL-C goals in patients at high and very high risk (52). Treatment adherence should be enhanced by improving health literacy. Even after achieving and maintaining LDL-C goals, patients should address the long-term residual risk of cardiovascular events by adhering to optimal management of comorbidities and recommended lifestyle modifications.

4.4 Emerging evidence on functionality of high-density lipoprotein (HDL)

While intensive LDL-C lowering remains a cornerstone of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease prevention, emerging evidence indicates that considerable residual risk persists even after achieving very low LDL-C levels. This observation suggests that lipid-related risk extends beyond LDL-C concentration alone. Increasing recognition of dysfunctional HDL challenges the traditional paradigm that higher HDL-C invariably confers protection, underscoring that lipoprotein functionality may be as important as its circulating levels (57). Oxidative and inflammatory modifications can render HDL pro-atherogenic, impairing its cholesterol efflux, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties (57). These findings collectively question whether further LDL-C reduction alone can meaningfully address residual risk. A more holistic approach that targets the restoration of lipoprotein quality and function may offer greater benefit in mitigating cardiovascular disease burden.

5 Future development

5.1 Preemptive management of subclinical atherosclerosis

With a slow progression, atherosclerosis begins decades before the advent of clinical symptoms, which are often related to luminal stenosis or thrombotic obstruction. Studies have shown that subclinical atherosclerosis occurs and progresses early in life (10). In the PESA prospective cohort study of asymptomatic participants (mean age, 45.8 years) from a Spanish bank (64), subclinical atherosclerosis was detected using ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) in 63% of the overall cohort (71% for males; 48% for females). An analysis (65) of Framingham Heart Study revealed that participants with no established risk factors at 50 years of age had a minimal lifetime risk for ASCVD (51.7% for men; 39.2% for women) and a long survival (median, 30 years for men; 36 years for women). These data suggest that addressing subclinical atherosclerosis and other risk factors at younger ages before symptom onset should be an emerging paradigm for the prevention of ASCVD.

An early, intensive reduction in LDL-C levels during young adulthood is increasingly considered an effective approach for the prevention of ASCVD via minimization of the progression of atherosclerotic plaque (66, 67). Six-year follow-up data from the PESA cohort study (66) demonstrated that one-third of middle-aged (40–55 years at baseline), asymptomatic individuals had progression of subclinical atherosclerosis, and that the effect of elevated LDL-C on the risk of atherosclerotic progression was more significant in younger participants (age groups, 40–43, 44–47, and ≥48 years; P for interaction = 0.04). These findings highlight the importance of strictly controlling risk factors at young ages for the prevention of atherosclerotic progression (66). Recently, a phase IV open-label single-arm ARCHITECT trial utilized a non-invasive quantitative CT scan to assess changes in coronary plaque burden and its morphology in patients who received alirocumab for familial hypercholesterolemia and had no clinical ASCVD (68). After 78 weeks of treatment, the patients demonstrated significant plaque regression (burden reduced from 34.6% to 30.4%; P < 0.001) and plaque stabilization (fibro-fatty and necrotic plaque reduced by 3.9% [P < 0.001] and 0.6% [P < 0.001], respectively) on CT angiography (68). The ongoing PRECAD randomized trial (67) investigates the effect of maintaining LDL-C levels <70 mg/dl, along with rigorous control of blood pressure and glucose, on the risk of new-onset atherosclerosis and/or its progression in individuals aged 20–39 years without known cardiovascular disease. The results will inform the future prospect of primary prevention strategies for ASCVD in young adults.

5.2 Lp(a)

Elevated Lp(a) levels have been increasingly recognized as a causal and continuous risk factor for cardiovascular events. It is estimated that each 50 nmol/L increase in the Lp(a) level compared to the median is associated with an approximately 20% surge in the risk of MACEs (69). Despite strong genetic and epidemiological evidence linking elevated Lp(a) to ASCVD risk, no specific Lp(a)-lowering therapy has yet received regulatory approval. While we eagerly anticipate the results of large-scale randomized controlled trials investigating the impact of specific Lp(a)-lowering therapies on the risk of MACEs in patients with ASCVD, including Lp(a)HORIZON on pelacarsen (NCT04023552) and OCEAN(a) on olpasiran (NCT05581303), an extra reduction in LDL-C could be considered to mitigate the residual risk associated with an elevation in Lp(a) at different ages (69). Additionally, reductions in Lp(a) induced by PCSK9 inhibitors may further reduce the risk of cardiovascular events. In a pre-specified analysis of the phase III randomized FOURIER trial, evolocumab reduced the risk of CHD death, MI or urgent revascularization by 23% (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.67–0.88) in patients with a higher-than-median level of Lp(a) at baseline, and by 7% (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.80–1.08; Pinteraction = 0.07) in patients with a Lp(a) level not exceeding the median at baseline (70). In a pre-specified analysis of the phase III randomized ODYSSEY Outcomes trial, a 1 mg/dl reduction in Lp(a) with alirocumab was associated with an HR of 0.994 (95% CI, 0.990–0.999; P = 0.0081) for the risk of MACEs (71).

6 Conclusion

The formation, evolution, and rupture of atherosclerotic plaque are the major risk factors for the development of ASCVD, which is a critical public health threat worldwide. Plaque progression in terms of luminal stenosis and morphological features is associated with an elevated risk of acute coronary syndrome. Reductions in LDL-C levels have dose-dependent effects on the regression and stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques, as well as the reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease. The relationships between LDL-C levels, plaque morphology, and clinical outcomes have supported the central role of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in the prevention of ASCVD. Current guidelines recommend that individuals at very high risk should consider combination therapy to facilitate the attainment of the LDL-C goal. In real-world practice, patient adherence is the prerequisite to acquire the clinical benefits of intensive lipid-lowering therapy. Considering the rapidity of plaque progression, subclinical atherosclerosis should be detected, preferably with non-invasive imaging tools, at early stages, facilitating early management of LDL-C levels and prevention of ASCVD in the long term.

Statements

Author contributions

FC-CT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. M-QL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. T-HL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. H-FT: Writing – review & editing. C-KW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Sanofi provided Editorial support. The authors are responsible for all content and editorial decisions and received no payment from Sanofi directly or indirectly related to this publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CHD, coronary heart disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESC/EAS, European Society of Cardiology/European Atherosclerosis Society; FCT, fibrous cap thickness; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LRP, lipid-rich plaque; Lp(a) , lipoprotein(a); MACE, major adverse cardiac event; MI, myocardial infarction; MLA, minimum lumen area; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; TCFAs, thin-cap fibroatheromas; ThCFAs, thick-cap fibroatheromas.

References

1.

Madaudo C Coppola G Parlati ALM Corrado E . Discovering inflammation in atherosclerosis: insights from pathogenic pathways to clinical practice. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:6016. 10.3390/ijms25116016

2.

Underberg J Toth PP Rodriguez F . LDL-C target attainment in secondary prevention of ASCVD in the United States: barriers, consequences of nonachievement, and strategies to reach goals. Postgrad Med. (2022) 134:752–62. 10.1080/00325481.2022.2117498

3.

Rafieian-Kopaei M Setorki M Doudi M Baradaran A Nasri H . Atherosclerosis: process, indicators, risk factors and new hopes. Int J Prev Med. (2014) 5:927–46. PMID: 25489440

4.

Ference BA Ginsberg HN Graham I Ray KK Packard CJ Bruckert E et al Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European atherosclerosis society consensus panel. Eur Heart J. (2017) 38:2459–72. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144

5.

Libby P . The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature. (2021) 592:524–33. 10.1038/s41586-021-03392-8

6.

Jaiswal S Natarajan P Silver AJ Gibson CJ Bick AG Shvartz E et al Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:111–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719

7.

Ridker PM Everett BM Thuren T MacFadyen JG Chang WH Ballantyne C et al Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:1119–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914

8.

Gumuser ED Schuermans A Cho SMJ Sporn ZA Uddin MM Paruchuri K et al Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential predicts adverse outcomes in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2023) 81:1996–2009. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.03.401

9.

Marfella R Prattichizzo F Sardu C Fulgenzi G Graciotti L Spadoni T et al Microplastics and nanoplastics in atheromas and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. (2024) 390:900–10. 10.1056/NEJMoa2309822

10.

Libby P Buring JE Badimon L Hansson GK Deanfield J Bittencourt MS et al Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2019) 5:56. 10.1038/s41572-019-0106-z

11.

Fan J Watanabe T . Atherosclerosis: known and unknown. Pathol Int. (2022) 72:151–60. 10.1111/pin.13202

12.

Rehberger Likozar A Zavrtanik M Šebeštjen M . Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to clinical relevance and treatment options. Ann Med. (2020) 52:162–77. 10.1080/07853890.2020.1775287

13.

Rawther T Tabet F . Biology, pathophysiology and current therapies that affect lipoprotein (a) levels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2019) 131:1–11. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.04.005

14.

Hajjar KA Gavish D Breslow JL Nachman RL . Lipoprotein(a) modulation of endothelial cell surface fibrinolysis and its potential role in atherosclerosis. Nature. (1989) 339:303–5. 10.1038/339303a0

15.

Ramharack R Barkalow D Spahr MA . Dominant negative effect of TGF-beta1 and TNF-alpha on basal and IL-6-induced lipoprotein(a) and apolipoprotein(a) mRNA expression in primary monkey hepatocyte cultures. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (1998) 18:984–90. 10.1161/01.atv.18.6.984

16.

Bentzon JF Otsuka F Virmani R Falk E . Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ Res. (2014) 114:1852–66. 10.1161/circresaha.114.302721

17.

Libby P . Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. (2013) 368:2004–13. 10.1056/NEJMra1216063

18.

Ahmadi A Argulian E Leipsic J Newby DE Narula J . From subclinical atherosclerosis to plaque progression and acute coronary events: jACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2019) 74:1608–17. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.012

19.

Araki M Yonetsu T Kurihara O Nakajima A Lee H Soeda T et al Predictors of rapid plaque progression: an optical coherence tomography study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2021) 14:1628–38. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.08.014

20.

Ojio S Takatsu H Tanaka T Ueno K Yokoya K Matsubara T et al Considerable time from the onset of plaque rupture and/or thrombi until the onset of acute myocardial infarction in humans: coronary angiographic findings within 1 week before the onset of infarction. Circulation. (2000) 102:2063–9. 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2063

21.

Glaser R Selzer F Faxon DP Laskey WK Cohen HA Slater J et al Clinical progression of incidental, asymptomatic lesions discovered during culprit vessel coronary intervention. Circulation. (2005) 111:143–9. 10.1161/01.Cir.0000150335.01285.12

22.

Stone GW Maehara A Lansky AJ de Bruyne B Cristea E Mintz GS et al A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. (2011) 364:226–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1002358

23.

Zaman T Agarwal S Anabtawi AG Patel NS Ellis SG Tuzcu EM et al Angiographic lesion severity and subsequent myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. (2012) 110:167–72. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.008

24.

Erlinge D Maehara A Ben-Yehuda O Botker HE Maeng M Kjoller-Hansen L et al Identification of vulnerable plaques and patients by intracoronary near-infrared spectroscopy and ultrasound (PROSPECT II): a prospective natural history study. Lancet. (2021) 397:985–95. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00249-X

25.

Yokoya K Takatsu H Suzuki T Hosokawa H Ojio S Matsubara T et al Process of progression of coronary artery lesions from mild or moderate stenosis to moderate or severe stenosis: a study based on four serial coronary arteriograms per year. Circulation. (1999) 100:903–9. 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.903

26.

Waksman R Di Mario C Torguson R Ali ZA Singh V Skinner WH et al Identification of patients and plaques vulnerable to future coronary events with near-infrared spectroscopy intravascular ultrasound imaging: a prospective, cohort study. Lancet. (2019) 394:1629–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31794-5

27.

Prati F Romagnoli E Gatto L La Manna A Burzotta F Ozaki Y et al Relationship between coronary plaque morphology of the left anterior descending artery and 12 months clinical outcome: the CLIMA study. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41:383–91. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz520

28.

Fabris E Berta B Roleder T Hermanides RS IJsselmuiden AJ Kauer F et al Thin-Cap fibroatheroma rather than any lipid plaques increases the risk of cardiovascular events in diabetic patients: insights from the COMBINE OCT-FFR trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2022) 15:e011728. 10.1161/circinterventions.121.011728

29.

Tsujita K Sugiyama S Sumida H Shimomura H Yamashita T Yamanaga K et al Impact of dual lipid-lowering strategy with ezetimibe and atorvastatin on coronary plaque regression in patients with percutaneous coronary intervention: the multicenter randomized controlled PRECISE-IVUS trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2015) 66:495–507. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.065

30.

Nicholls SJ Kataoka Y Nissen SE Prati F Windecker S Puri R et al Effect of evolocumab on coronary plaque phenotype and burden in statin-treated patients following myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2022) 15:1308–21. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.03.002

31.

Raber L Ueki Y Otsuka T Losdat S Haner JD Lonborg J et al Effect of alirocumab added to high-intensity statin therapy on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the PACMAN-AMI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2022) 327:1771–81. 10.1001/jama.2022.5218

32.

Nissen SE Lincoff AM Brennan D Ray KK Mason D Kastelein JJP et al Bempedoic acid and cardiovascular outcomes in statin-intolerant patients. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388:1353–64. 10.1056/NEJMoa2215024

33.

Nissen SE Tuzcu EM Schoenhagen P Brown BG Ganz P Vogel RA et al Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. (2004) 291:1071–80. 10.1001/jama.291.9.1071

34.

Nissen SE Nicholls SJ Sipahi I Libby P Raichlen JS Ballantyne CM et al Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA. (2006) 295:1556–65. 10.1001/jama.295.13.jpc60002

35.

Nissen SE Tardif JC Nicholls SJ Revkin JH Shear CL Duggan WT et al Effect of torcetrapib on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. (2007) 356:1304–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa070635

36.

Nicholls SJ Ballantyne CM Barter PJ Chapman MJ Erbel RM Libby P et al Effect of two intensive statin regimens on progression of coronary disease. N Engl J Med. (2011) 365:2078–87. 10.1056/NEJMoa1110874

37.

Nicholls SJ Puri R Anderson T Ballantyne CM Cho L Kastelein JJ et al Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: the GLAGOV randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2016) 316:2373–84. 10.1001/jama.2016.16951

38.

Komukai K Kubo T Kitabata H Matsuo Y Ozaki Y Takarada S et al Effect of atorvastatin therapy on fibrous cap thickness in coronary atherosclerotic plaque as assessed by optical coherence tomography: the EASY-FIT study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 64:2207–17. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.045

39.

Räber L Koskinas KC Yamaji K Taniwaki M Roffi M Holmvang L et al Changes in coronary plaque composition in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with high-intensity statin therapy (IBIS-4): a serial optical coherence tomography study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2019) 12:1518–28. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.08.024

40.

Sugizaki Y Otake H Kawamori H Toba T Nagano Y Tsukiyama Y et al Adding alirocumab to rosuvastatin helps reduce the vulnerability of thin-cap fibroatheroma: an ALTAIR trial report. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2020) 13:1452–4. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.01.021

41.

Bhindi R Guan M Zhao Y Humphries KH Mancini GBJ . Coronary atheroma regression and adverse cardiac events: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Atherosclerosis. (2019) 284:194–201. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.03.005

42.

Shepherd J Blauw GJ Murphy MB Bollen EL Buckley BM Cobbe SM et al Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2002) 360:1623–30. 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11600-x

43.

Collins R Armitage J Parish S Sleigh P Peto R , Heart Protection Study Collaborative G. MRC/BHF heart protection study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. (2003) 361:2005–16. 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13636-7

44.

LaRosa JC Grundy SM Waters DD Shear C Barter P Fruchart JC et al Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. (2005) 352:1425–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa050461

45.

Ridker PM Danielson E Fonseca FA Genest J Gotto AM Jr Kastelein JJ et al Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. (2008) 359:2195–207. 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646

46.

Robinson JG Farnier M Krempf M Bergeron J Luc G Averna M et al Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372:1489–99. 10.1056/NEJMoa1501031

47.

Yusuf S Bosch J Dagenais G Zhu J Xavier D Liu L et al Cholesterol lowering in intermediate-risk persons without cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:2021–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1600176

48.

Sabatine MS Giugliano RP Wiviott SD Raal FJ Blom DJ Robinson J et al Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372:1500–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1500858

49.

Sabatine MS Giugliano RP Keech AC Honarpour N Wiviott SD Murphy SA et al Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. (2017) 376:1713–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664

50.

Schwartz GG Steg PG Szarek M Bhatt DL Bittner VA Diaz R et al Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379:2097–107. 10.1056/NEJMoa1801174

51.

Mach F Baigent C Catapano AL Koskinas KC Casula M Badimon L et al 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41:111–88. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

52.

Ray KK Reeskamp LF Laufs U Banach M Mach F Tokgözoğlu LS et al Combination lipid-lowering therapy as first-line strategy in very high-risk patients. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43:830–3. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab718

53.

Benner JS Glynn RJ Mogun H Neumann PJ Weinstein MC Avorn J . Long-term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients. JAMA. (2002) 288:455–61. 10.1001/jama.288.4.455

54.

Fox KM Tai MH Kostev K Hatz M Qian Y Laufs U . Treatment patterns and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) goal attainment among patients receiving high- or moderate-intensity statins. Clin Res Cardiol. (2018) 107:380–8. 10.1007/s00392-017-1193-z

55.

Dyrbus K Gasior M Desperak P Nowak J Osadnik T Banach M . Characteristics of lipid profile and effectiveness of management of dyslipidaemia in patients with acute coronary syndromes—data from the TERCET registry with 19,287 patients. Pharmacol Res. (2019) 139:460–6. 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.12.002

56.

Ray KK Molemans B Schoonen WM Giovas P Bray S Kiru G et al EU-Wide Cross-Sectional observational study of lipid-modifying therapy use in secondary and primary care: the DA VINCI study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2021) 28:1279–89. 10.1093/eurjpc/zwaa047

57.

Madaudo C Bono G Ortello A Astuti G Mingoia G Galassi AR et al Dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and coronary artery disease: a narrative review. J Pers Med. (2024) 14:996. 10.3390/jpm14090996

58.

Cabana MD Rand CS Powe NR Wu AW Wilson MH Abboud PA et al Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. (1999) 282:1458–65. 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458

59.

Cure E Cumhur Cure M . Emerging risks of lipid-lowering therapy and low LDL levels: implications for eye, brain, and new-onset diabetes. Lipids Health Dis. (2025) 24:185. 10.1186/s12944-025-02606-6

60.

Gaba P O'Donoghue ML Park JG Wiviott SD Atar D Kuder JF et al Association between achieved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and long-term cardiovascular and safety outcomes: an analysis of FOURIER-OLE. Circulation. (2023) 147:1192–203. 10.1161/circulationaha.122.063399

61.

Newman CB Preiss D Tobert JA Jacobson TA Page RL 2nd Goldstein LB et al statin safety and associated adverse events: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2019) 39:e38–81. 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000073

62.

Stroes ES Thompson PD Corsini A Vladutiu GD Raal FJ Ray KK et al Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy-European atherosclerosis society consensus panel statement on assessment, aetiology and management. Eur Heart J. (2015) 36:1012–22. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv043

63.

Zhang H Plutzky J Shubina M Turchin A . Continued statin prescriptions after adverse reactions and patient outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. (2017) 167:221–7. 10.7326/m16-083864

64.

Fernández-Friera L Peñalvo JL Fernández-Ortiz A Ibañez B López-Melgar B Laclaustra M et al Prevalence, vascular distribution, and multiterritorial extent of subclinical atherosclerosis in a middle-aged cohort: the PESA (progression of early subclinical atherosclerosis) study. Circulation. (2015) 131:2104–13. 10.1161/circulationaha.114.014310

65.

Lloyd-Jones DM Leip EP Larson MG D'Agostino RB Beiser A Wilson PW et al Prediction of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease by risk factor burden at 50 years of age. Circulation. (2006) 113:791–8. 10.1161/circulationaha.105.548206

66.

Mendieta G Pocock S Mass V Moreno A Owen R García-Lunar I et al Determinants of progression and regression of subclinical atherosclerosis over 6 years. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2023) 82:2069–83. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.09.814

67.

Devesa A Ibanez B Malick WA Tinuoye EO Bustamante J Peyra C et al Primary prevention of subclinical atherosclerosis in young adults: jACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2023) 82:2152–62. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.09.817

68.

Perez de Isla L Diaz-Diaz JL Romero MJ Muniz-Grijalvo O Mediavilla JD Argueso R et al Alirocumab and coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic patients with familial hypercholesterolemia: the ARCHITECT study. Circulation. (2023) 147:1436–43. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062557

69.

Kronenberg F Mora S Stroes ESG Ference BA Arsenault BJ Berglund L et al Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European atherosclerosis society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43:3925–46. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac361

70.

O'Donoghue ML Fazio S Giugliano RP Stroes ESG Kanevsky E Gouni-Berthold I et al Lipoprotein(a), PCSK9 inhibition, and cardiovascular risk. Circulation. (2019) 139:1483–92. 10.1161/circulationaha.118.037184

71.

Bittner VA Szarek M Aylward PE Bhatt DL Diaz R Edelberg JM et al Effect of alirocumab on lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular risk after acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 75:133–44. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.057

Summary

Keywords

atherosclerosis, low density lipoprotein, lipoprotein (a), statin, ezetimibe, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors

Citation

Tam FC-C, Lin M-Q, Lam T-H, Tse H-F and Wong C-K (2025) Atherosclerotic plaque, cardiovascular risk, and lipid-lowering strategies: a narrative review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1659228. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1659228

Received

03 July 2025

Accepted

16 October 2025

Published

16 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Alexander Akhmedov, University of Zurich, Switzerland

Reviewed by

Achuthan Raghavamenon, Amala Cancer Research Centre, India

Cristina Madaudo, University of Palermo, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Tam, Lin, Lam, Tse and Wong.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Chun-Ka Wong wongeck@hku.hk

ORCID Hung-Fat Tse orcid.org/0000-0003-4665-7887

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.