Abstract

Objective:

Systematic review and meta-analysis of the incidence and risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmissions in patients with chronic heart failure(CHF).

Methods:

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, Medline, CINAHL, and Chinese databases up to February 2025. Data were analyzed by using Stata 17.0.

Results:

Among 4,040 screened publications, 21 studies were included. The incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission in CHF patients was 17.7% (95% CI: 13.9%–21.5%). Age ≥65 years (OR = 1.35, P = 0.024), diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (OR = 1.26, P = 0.000), diabetes (OR = 1.49, P = 0.001), atrial fibrillation (AF) (OR = 1.12, P = 0.005), coronary heart disease (CHD) (OR = 5.28, P = 0.000), cardiomyopathy (OR = 1.44, P = 0.000), NYHA class ≥Ⅲ or Ⅳ (OR = 1.64, P = 0.000), use of beta blockers (OR = 1.25, P = 0.000), loop diuretics (OR = 1.41, P = 0.004), thiazides (OR = 1.22, P = 0.000), LVEF < 40% (OR = 1.44, P = 0.000), and length of stay (LOS) (OR = 1.16, P = 0.000) were risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmission in CHF patients.

Conclusions:

The incidence of 30-day unplanned readmissions in patients with CHF is moderate but concerning. Accurate identification of identified risk factors for targeted interventions to reduce the need for readmissions.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024610843, PROSPERO CRD42024610843.

1 Introduction

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is the end stage of all types of cardiovascular diseases, and its incidence is rising globally (1). Current estimates indicate that approximately 64.3 million individuals worldwide are affected by HF, resulting in treatment costs as high as $100 billion annually. Notably, over 60% of these expenditures are attributed to managing CHF patients who require readmission within one year of discharge (2). Moreover, nearly one-third of these readmissions occur unexpectedly within just 30 days post-discharge, highlighting the substantial clinical and economic burden associated with this condition (3).

Unplanned readmissions, which are defined as unanticipated readmissions within 30 days of discharge for the same or a related condition, are a significant indicator of healthcare quality and are strongly associated with the standard of medical care and discharge planning during the patient's most recent hospitalization (4). Research indicates that up to 25% of unplanned readmissions for CHF could be preventable (5).

Several studies have examined the incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission among CHF patients (6); however, there are significant differences in the findings due to factors such as the study population, geographic region, and sample size. To date, no comprehensive systematic review has been conducted on both the incidence rates and associated risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmissions in this patient group. Thus, this study quantitatively synthesizes the available evidence to identify predictors influencing 30-day unplanned readmission in CHF patients. The findings will facilitate early risk identification, preventive interventions, and optimized nursing management, ultimately improving patient outcomes while reducing the economic burden on healthcare systems.

2 Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. It was registered in the National Institute for Health Research PROSPERO database with registration number CRD42024610843.

2.1 Search strategy

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, CINAHL, Medline, Scopus, China Knowledge Network (CNKI), Wanfang Database, Chinese Biomedical Database (CBM), and Chinese Science and Technology Journal Database (VIP) from inception to February 28, 2025. The search strategies used a combination of MeSH terms and entry terms. The search terms included heart failure, cardiac failure, heart decompensation, patient readmission*, unplanned readmission*, 30-day readmission*, hospital readmission*, risk factor*, influencing factor*, impact factor*, dangerous factor*, influence factor*, predictive factor*, contributing factor*, relevant factor*, relevant factor*, correlative factor*, associated factor*, prevalence*, incidence. The detailed search strategies are shown in Supplementary Appendix A1.

2.2 Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Study population: patients diagnosed with chronic heart failure (CHF) and aged ≥18 years; (2) Type of study: observational studies, including cohort studies, case-control studies and cross-sectional studies; (3) Study content: the study focuses on unplanned readmissions within 30 days post-discharge among patients with CHF; (4) Outcome indicator: incidence and/or risk factors of 30-day unplanned readmissions.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Literature with incomplete information or from which the full text cannot be obtained; (2) Duplicate publication; (3) Non-Chinese and English literature.

2.3 Study selection

Two researchers with training in evidence-based research independently screened, retrieved, and cross-checked the literature. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third researcher to reach a consensus. Duplicated literature was excluded by using the literature management program Endnote X9. The titles and abstracts were initially read to eliminate any irrelevant literature, and then the full texts were read for re-screening to determine the final literature to be included.

2.4 Data extraction

Two reviewers independently reviewed and extracted data from the included studies. They extracted relevant information from the last included studies using a standardized data extraction form, including first author, publication year, region, study design, sample size, the incidence of 30-day unplanned readmissions in CHF, influencing factors, and Odds ratio (OR) or Hazard ratio (HR) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

2.5 Quality assessment

Two researchers independently assessed the quality of the included literature using a back-to-back approach, applying the most appropriate quality assessment tool based on the type of literature. In cases of conflicting opinions, a third researcher was consulted to resolve discrepancies. The methodological quality of cohort and case-control studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) (7).

Three aspects make up the NOS: selection, comparability, and exposure. Each dimension is evaluated using 8 items for a total score of 9 points. The quality of cross-sectional studies was evaluated according to the quality evaluation criteria for cross-sectional studies recommended by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) (8), which contains 11 entries, with a total score of 11 points. A rating of 0–3 indicates low quality, 4–7 indicates medium quality, and 8–11 indicates high quality.

2.6 Statistical analysis

In this study, a meta-analysis of the incidence and risk factors of 30-day unplanned readmissions in CHF patients was performed using Stata 17.0 software. The OR and 95% CI were used to express the count data, and the MD and 95% CI were selected for the measurement data. Moreover, the I2 was used to evaluate the statistical heterogeneity. In addition, a meta-analysis was performed by using a random effects model when P < 0.1 and/or I2 > 50%. When P ≥ 0.1 and I2 ≤ 50%, the data were retested by using a fix effects model. Egger linear regression tests and funnel plots were combined to assess potential publication bias, and P > 0.05 suggested that there was no publication bias.

3 Results

3.1 Search results

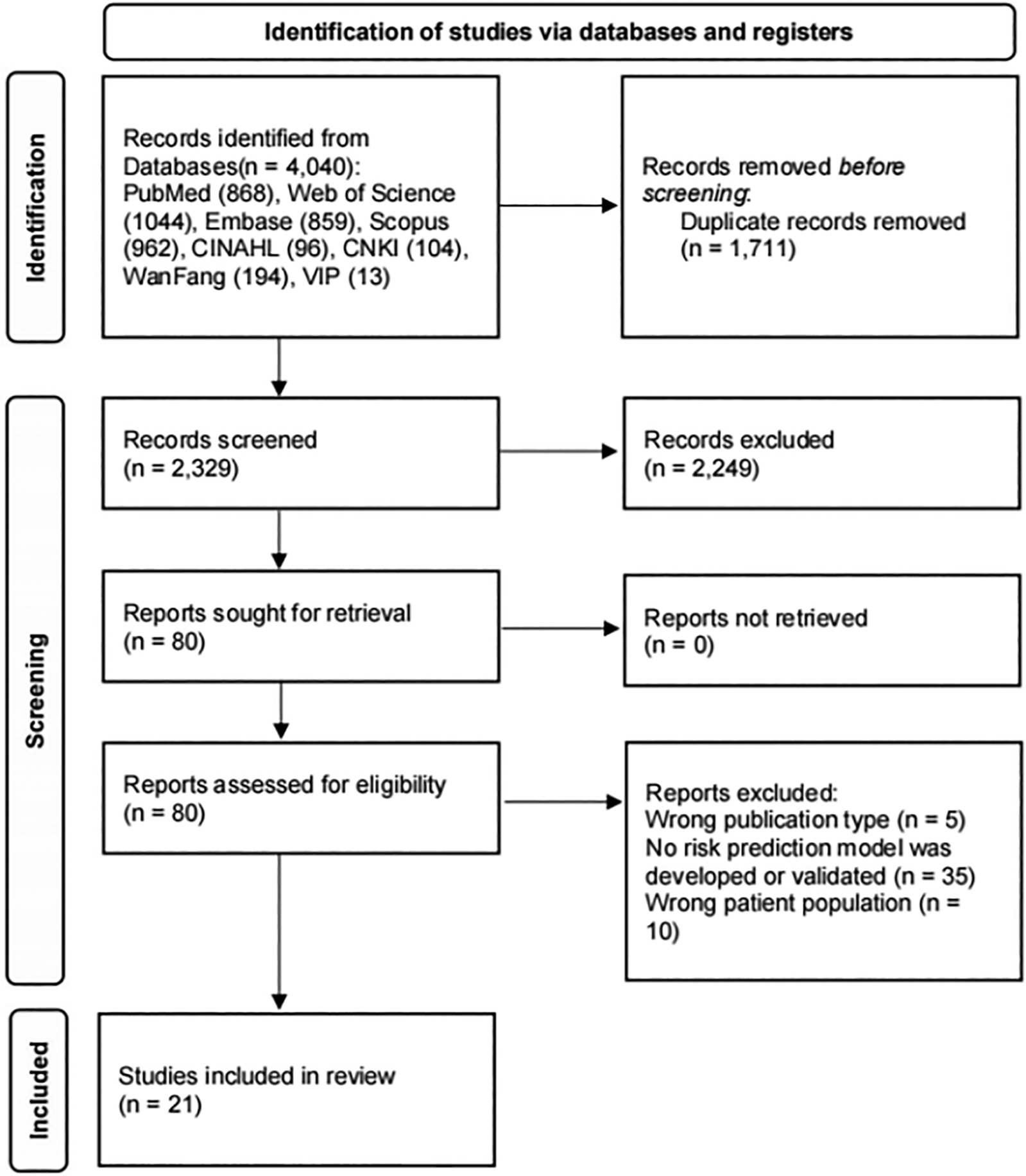

The initial literature search identified 4,040 studies, which were reduced to 2,329 after the removal of duplicates. After the screening of titles and abstracts, 80 articles were retrieved for full-text evaluation. Ultimately, 21 studies (9–29) met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into this meta-analysis. The study flowchart according to the PRISMA statement is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Flowchart of study inclusion.

3.2 Study characteristics

The sixteen included studies were mainly from the USA (n = 10) (9–18), China (n = 4) (19–22), Japan (n = 2) (23, 24), Korea (n = 2) (25, 26), Lebanon (n = 1) (27), Canada (n = 1) (28), and Ethiopia (n = 1) (29). The 21 studies comprised 18 cohort studies, two case-control studies, and one cross-sectional study. Among them, there were 18 English papers and 3 Chinese papers. The sample size (excluding missing data) ranged from 187 to 10,978,056. The predicted results were 30-day unplanned readmission, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| ID | Study | Country | Study type | Sample size | Male (%) | CHF (n) | Overall incidence | Risk factors included | Quality score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOS | AHRQ | |||||||||

| 1 | Alzaghari 2019 (9) | US | Cross-sectional study | 270 | 140 (52) | 138 | 51 | CKD, use of CPAP machine, BNP | 7 | |

| 2 | Arora 2016 (10) | US | Retrospective study | 301,892 | (49.4) | 64,264 | 21.29 | CCI, obesity, DM, CPD, peripheral vascular disease, renal failure, electrolyte imbalance, anemia, coagulation defect, depression, psychosis, substance abuse, index admission type(non elective/elective), disposition(home/facility/others), LOS | 8 | |

| 3 | Carlson 2019 (11) | US | Retrospective study | 189 | 79 (42) | 10 | 5.3 | emergent admission, AF | 6 | |

| 4 | Fudim 2017 (12) | US | Retrospective study | 6,584 | (66) | 751 | 11.00 | chronic respiratory disease, cerebrovascular disease, cardiac resynchronization therapy, loop diuretics, ACEI or ARB | 8 | |

| 5 | Kwok 2019 (13) | US | Retrospective study | 109,780 | 52,936 (48.22) | 16,576 | 15.1 | renal failure, cancer, circulatory support, discharge against medical advice | 7 | |

| 6 | Mirkin 2017 (14) | US | Retrospective study | 155,146 | 74,082 (47.75) | 35,294 | 22.8 | sex, race, coverage by medicare, comorbidity, discharge to a skilled nursing facility or with a home nurse, LOS, admission from another facility, emergent admission | 8 | |

| 7 | Gusto 2023 (15) | US | Case-control study | 450 | 234 (52) | – | – | Living arrangements, CRF | 7 | |

| 8 | Jain 2023 (16) | US | Retrospective study | 48,971 | 26,542 | 10,370 | 21.2 | sex, socioeconomic status, index admission type(non elective/elective), AF, COPD, CKD, anemia, CCI | 6 | |

| 9 | Jha 2022 (17) | US | Retrospective study | 60,514 | 23,358 | 12,708 | 21 | medicaid insurance, Charlson co-morbidity score, LOS, age, sex | 6 | |

| 10 | Kim 2023 (18) | US | Retrospective study | 43,111 | 15,804 | 8,794 | 20.4 | Age, Elixhauser co-morbidity indexes, number of diagnoses, renal failure | 6 | |

| 11 | Shao 2021 (19) | China | Retrospective study | 3,129 | 1,473 (47.08) | 713 | 22.79 | DM, renal insufficiency, AMI, LOS, quality of post-discharge care | 7 | |

| 12 | Hu 2022 (20) | China | Prospective study | 2,254 | 1,324 (58.74) | 101 | 7.1 | LVEF, left ventricular end-diastolic size, hs-cTn, NT-proBNP, hemoglobin, RDW-CV, albumin | 9 | |

| 13 | Zhang 2023 (21) | China | Retrospective study | 14,843 | 6,713 (45.227) | 1,479 | 9.964 | NT-proBNP, LOS, triglycerides, blood phosphorus, blood potassium, lactate dehydrogenase | 8 | |

| 14 | Zhuang 2022 (22) | China | Retrospective study | 390 | 239 (61.28) | – | – | alcohol abuse, regular exercise, cardiac function classification, hypertension, DM, CHD, hyperlipidemia, arrhythmia | 6 | |

| 15 | Aizawa 2015 (23) | Japan | Case-control study | 68,257 | 2,351 (52.5) | 4,479 | 6.56 | age, NYHA classification, CCI, beta-blockers, loop diuretics, thiazide, nitrates, LOS, BMI, ACEI or ARB, CCB, spironolactone | 7 | |

| 16 | Miyazaki 2023 (24) | Japan | Retrospective study | 180,125 | 93,182 | 10,283 | 5.71 | LOS,sex, smoking, age, BMI, barthel index, artificial ventilator, beta-blockers, thiazides, tolvaptan, loop diuretics, carperitide, class Ⅲ antiarrhythmic agents, MI, DM, renal disease, AF, dilated cardiomyopathy, discharge to home | 7 | |

| 17 | Chung 2017 (25) | Korea | Retrospective study | 19,128 | 8,918 (46.6) | 5,286 | 27.6 | paralysis, metastatic cancer, loop diuretics, ACEI or ARB | 9 | |

| 18 | Lim 2018 (26) | Korea | Prospective study | 4,566 | 2,347 (51.40) | 446 | 9.8 | age, NYHA classification, hypertension, HF, COPD, etiology of cardiomyopathy, SBP, LVEF, serum sodium level, BNP or NT-proBNP, beta blockers, ACEI or ARB | 8 | |

| 19 | Deeka 2016 (27) | Lebanon | Retrospective study | 187 | 111 (59.40) | 28 | 15.00 | DM, CAD, LOS, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase levels | 7 | |

| 20 | Sharma 2022 (28) | Canada | Prospective study | 9,845 | 5,539 (56) | 2,165 | 22.00 | – | 9 | |

| 21 | Ayenew 2024 (29) | Ethiopia | Retrospective study | 572 | 303 (52.8) | 151 | 26.4 | age, rural residency, comorbidity, platelet, volume, hemoglobin | 9 | |

Characteristics of included studies.

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BMI, Body mass index; BNP, B-type Natriuretic Peptide; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCB, calcium channel blockers; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CHD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CPD, chronic pulmonary disease; CRF, chronic renal failure; DM, diabetes mellitus; hs-cTn, hypersensitive cardiac troponin T; LOS, length of stay; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RDW-CV, coefficient of variation of red cell distribution width; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

3.3 Quality assessment

Among the included studies, one cross-sectional study (9) received a quality score of 7, two case-control studies (15, 23) each scored 7 points, and eighteen cohort studies (10–14, 16–22, 24–29) received scores ranging from 6 to 9. Overall, the results of the literature quality evaluation showed that nine of the 21 literature were of high quality, and 12 were of medium quality.

3.4 The overall incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission in CHF patients

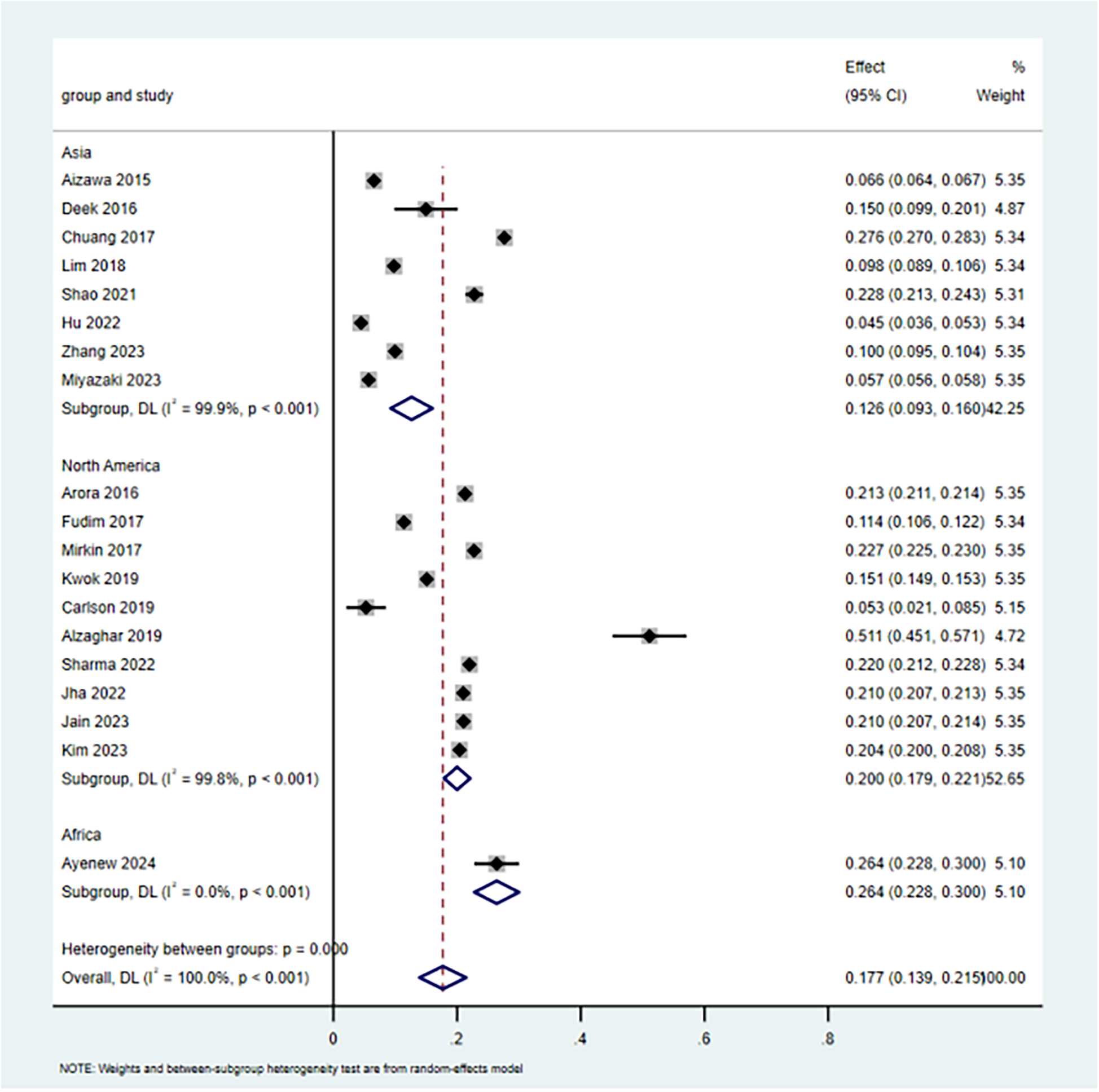

Of the 21 included studies, nineteen studies (9–14, 16–21, 23–29) reported the incidence of 30-day unplanned readmissions. Of the 19 included studies available for meta-analysis, the incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission ranged from 6% to 51%. As there was high heterogeneity between studies [I2 = 99.966%, P < 0.001], a random-effects model was employed for the meta-analysis. The estimated incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission was 17.7% (95% CI: 13.9%–21.5%). Subgroup analysis by region revealed the incidence of 20.2% (95% CI: 17.9%–22.1%) in North America, 12.6% (95% CI: 9.3%–16.0%) in Asia, and 26.4% (95% CI: 22.8%–30.2%) in Africa. The results of the study were relatively strong, and sensitivity analysis showed that the overall incidence did not change significantly when individual studies were excluded on a case-by-case basis (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission in CHF patients.

3.5 Meta-analysis results

A total of 83 risk factors were included in the study, of which 27 risk factors were eligible for meta-analysis: age, sex, NYHA classification, the longer length of stay(LOS), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin II receptor blockers(ARB), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease(COPD), chronic kidney disease(CKD), beta-blockers, renal failure, loop diuretics, thiazide, DM, LVEF, BNP or NT-proBNP, body mass index(BMI), index admission type(non elective/elective), coronary heart disease(CHD), acute myocardial infarction(AMI),medicaid insurance, hemoglobin, atrial fibrillation(AF), complications, use of artificial ventilator, hypertension, and cardiomyopathy. These 24 risk factors can be divided into four categories: demographic factors, disease-related factors, drug-related factors, and hospitalization-related factors, as shown in Table 2, the forest plots of risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmissions in patients with CHF are shown in Supplementary Appendix A2.

Table 2

| Risk factors | Number of studies | Heterogeneity test | Effects model | Meta-analysis results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I 2 (%) | P | Odds ration(OR) | P | |||

| Demographic factors | ||||||

| Age ≥65 | 5 | 99.6 | <0.001 | Random | 1.35 (1.04,1.75) | 0.024 |

| Female | 4 | 95.5 | <0.001 | Random | 1.03 (0.92,1.15) | 0.625 |

| Medicaid insurance | 2 | 97.8 | <.001 | Random | 0.96 (0.67,1.37) | 0.807 |

| Disease-related factors | ||||||

| COPD | 2 | 70.9 | 0.064 | Random | 1.28 (1.00,1.64) | 0.054 |

| CKD | 7 | 72.9 | 0.001 | Random | 1.26 (1.21,1.32) | 0.000 |

| DM | 5 | 87.9 | <0.001 | Random | 1.49 (1.17,1.89) | 0.001 |

| AF | 3 | 69.2 | 0.039 | Random | 1.12 (1.04–1.22) | 0.005 |

| CHD | 2 | 63.8 | 0.096 | Random | 5.28 (2.52,11.04) | 0.000 |

| Complication | 2 | 76.6 | 0.039 | Random | 1.27 (0.87,1.85) | 0.216 |

| AMI | 2 | 78.9 | 0.03 | Random | 1.61 (0.77,3.40) | 0.209 |

| Hypertension | 2 | 85.4 | 0.009 | Random | 1.96 (0.85,4.50) | 0.113 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 2 | 0 | 0.804 | Fix | 1.44 (1.26,1.65) | 0.000 |

| NYHA class ≥Ⅲ or Ⅳ | 2 | 0 | 0.767 | Fix | 1.64 (1.44,1.86) | 0.000 |

| Use of artificial ventilator | 2 | 83.4 | 0.014 | Random | 0.64 (0.16,2.58) | 0.533 |

| Drug factors | ||||||

| ACEI or ARB | 4 | 93.1 | <0.001 | Random | 0.88 (0.72,1.08) | 0.216 |

| Beta-blockers | 3 | 60.5 | 0.08 | Random | 1.25 (1.12,1.38) | 0.000 |

| Loop diuretics | 3 | 84.8 | 0.001 | Random | 1.41 (1.12,1.78) | 0.004 |

| Thiazide | 2 | 21.9 | 0.258 | Fix | 1.22 (1.14,1.30) | 0.000 |

| Laboratory indications | ||||||

| LVEF < 40% | 2 | 0 | 0.497 | Fix | 1.44 (1.19,1.75) | 0.000 |

| BNP ≥ 400 pg/mL or NTproBNP ≥ 1,800 pg/mL | 4 | 93.3 | <0.001 | Random | 1.53 (0.95,2.44) | 0.078 |

| Hemoglobin < 110 g/L | 2 | 94.7 | <0.001 | Random | 2.97 (0.71,12.40) | 0.136 |

| BMI | 2 | 97.5 | <0.001 | Random | 0.80 (0.54,1.18) | 0.263 |

| Hospitalization-related factors | ||||||

| Non-elective Admission(emergent admission) | 4 | 98.8 | <0.001 | Random | 1.15 (0.89,1.48) | 0.297 |

| LOS | 8 | 98.9 | <0.001 | Random | 1.16(1.08,1.24) | 0.000 |

Meta-analysis results of risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF.

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BMI, Body mass index; BNP, B-type Natriuretic Peptide; CHD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; LOS, length of stay; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI,myocardial infarction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

3.5.1 Demographic factors

The meta-analysis showed that age ≥65 years [OR = 1.35, 95% CI (1.04, 1.75), P = 0.024] was a risk factor for 30-day unplanned readmissions in patients with CHF. Moreover, female sex [OR = 1.03, 95% CI (0.92, 1.15), P = 0.625] and Medicaid insurance coverage [OR = 0.96, 95% CI (0.67, 1.37), P = 0.807] were not associated with the development of 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF.

3.5.2 Disease-related factors

The meta-analysis showed that diagnosed with CKD[OR = 1.26, 95%CI (1.21,1.32), P = 0.000], diabetes[OR = 1.49, 95%CI (1.17,1.89), P = 0.001], AF[OR = 1.12, 95%CI (1.04,1.22), P = 0.005], CHD[OR = 5.28, 95%CI (2.52,11.40), P = 0.000], cardiomyopathy[OR = 1.44, 95%CI (1.26,1.65), P = 0.000], and NYHA class ≥Ⅲ or Ⅳ[OR = 1.64, 95%CI (1.44,1.86), P = 0.000], were risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF. However, diagnosed with COPD [OR = 1.28, 95%CI (1.10,1.64), P = 0.054], AMI[OR = 1.61, 95%CI (0.77,3.40), P = 0.209], hypertension[OR = 1.96, 95%CI (0.85,4.50), P = 0.113], with complication(OR = 1.27, and use of artificial ventilator[OR = 0.64, 95%CI (0.16,2.58), P = 0.533],95%CI (0.87,1.85), P = 0.216), were not associated with the development of 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF.

3.5.3 Drug factors

The meta-analysis showed that the use of beta blockers at discharge [OR = 1.25, 95% CI (1.12, 1.38), P = 0.000], loop diuretics [OR = 1.41, 95% CI (1.12, 1.78), P = 0.004], and thiazides [OR = 1.22, 95% CI (1.14, 1.30), P = 0.000] were risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF. Moreover, the prescription of ACEI or ARB at discharge [OR = 0.88, 95%CI (0.16,2.58), P = 0.216] was not associated with the development of 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF.

3.5.4 Laboratory indications

The meta-analysis showed that LVEF < 40%[OR = 1.44, 95%CI(1.19,1.75), P = 0.000] was a risk factor for 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF. However, BNP ≥ 400 pg/mL or NTproBNP ≥ 1,800 pg/mL[OR = 1.53, 95%CI(0.95,2.44), P = 0.078], haemoglobin <110 g/L[OR = 2.97, 95%CI(0.71,12.40), P = 0.136], and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2[OR = 0.80, 95%CI(0.54,1.18), P = 0.297] were not associated with the development of 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF.

3.5.5 Hospitalization-related factors

The meta-analysis showed that longer LOS in the hospital[OR = 1.16, 95%CI(1.08,1.24), P = 0.000] was a risk factor for 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF. Moreover, non-elective admission(emergent admission)[OR = 1.15, 95%CI(0.89,1.48), P = 0.297] was not associated with the development of 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF.

3.6 Meta-analyses heterogeneity and publication bias

3.6.1 Sensitivity analyses

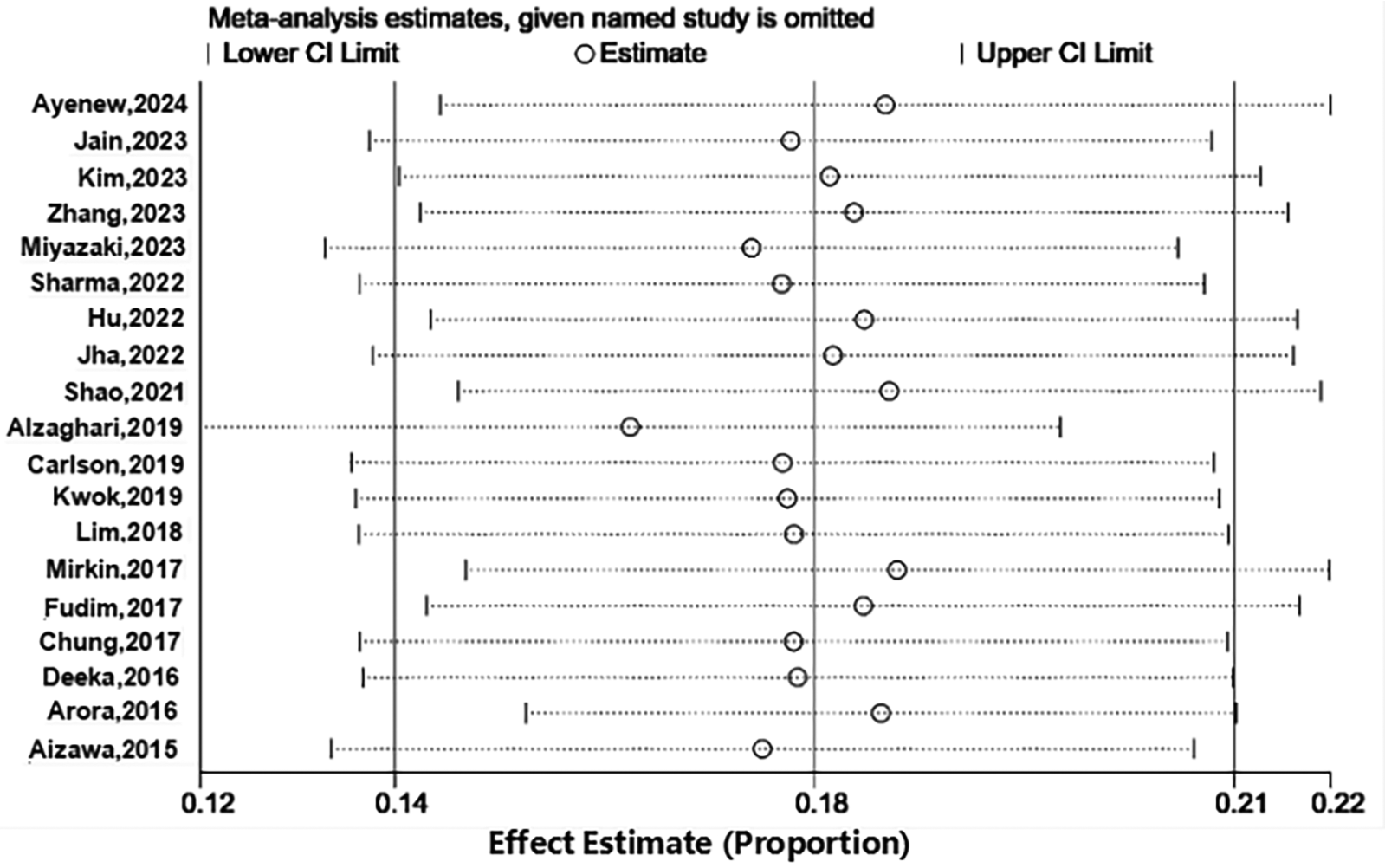

We performed a sensitivity analysis to furtherly explore the potential origin of heterogeneity by detaching each article from our meta-analysis independently. As shown in Figure 3, the pooled incidence demonstrated that our results were credible, and omitting any article did not obviously affect study heterogeneity.

Figure 3

Sensitive analysis of prevalence.

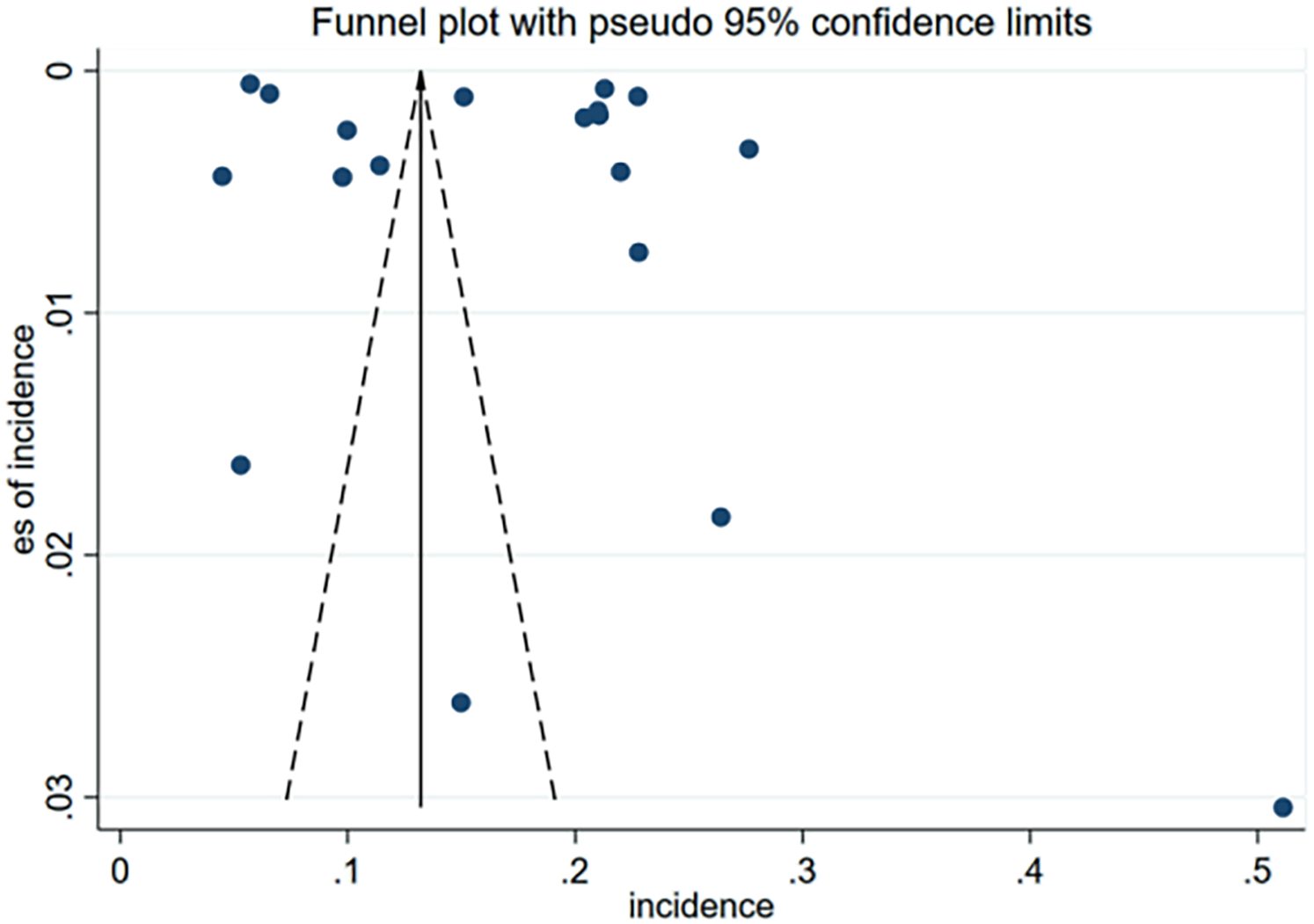

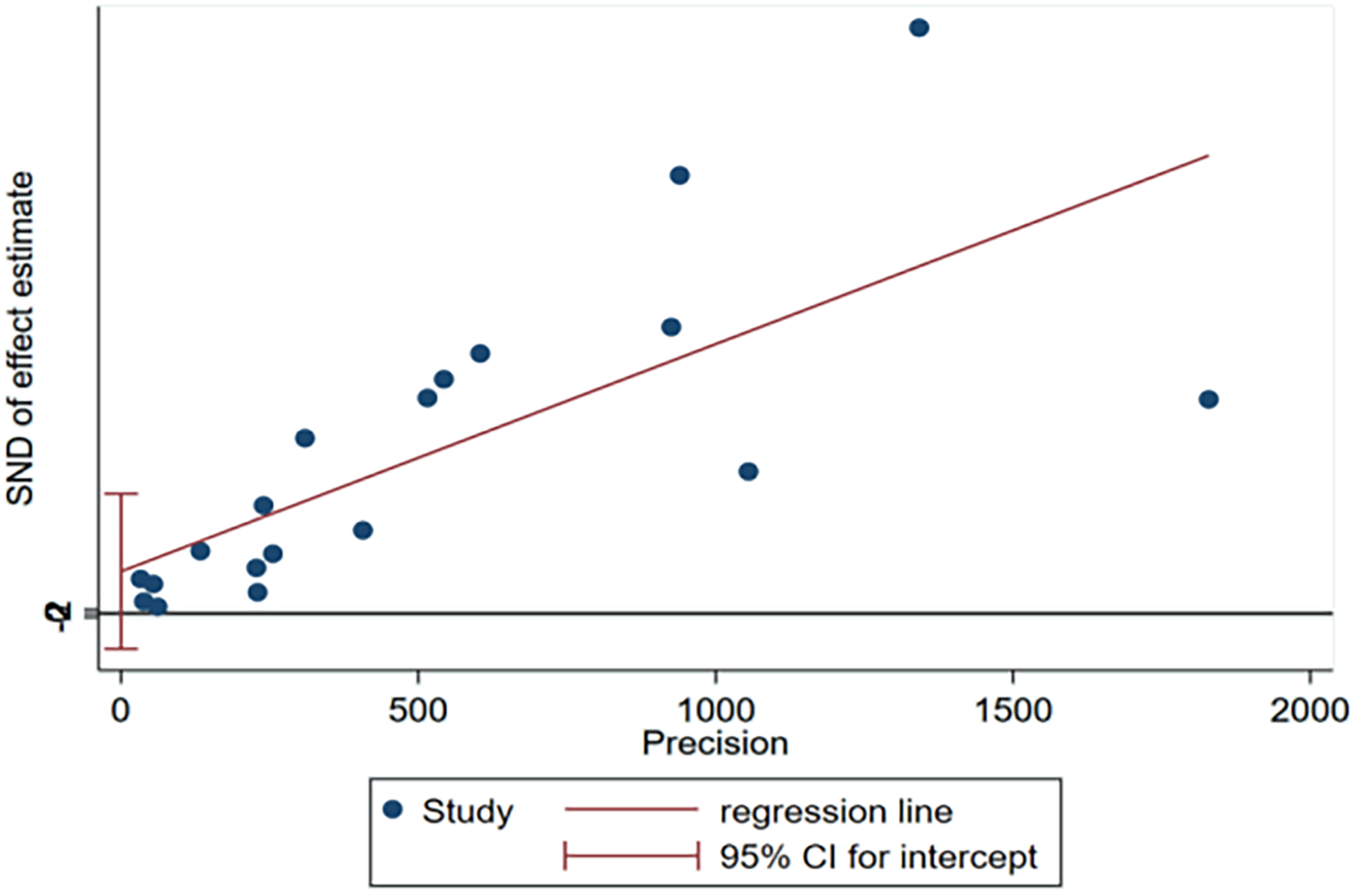

3.6.2 Publication bias

No significant publication bias was observed for the incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission in the funnel plot (Figure 4) or result from Egger test (Figure 5). As the number of articles analyzed on each risk factor was less than 10, we did not further analyze the publication bias.

Figure 4

Funnel plot of incidence for publication bias of included studies.

Figure 5

Egger's test plot of incidence for publication bias of included studies.

4 Discussion

4.1 The incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission for CHF patients is moderate, but still a cause for concern

The results of this study demonstrated a 17.7% (95% CI: 13.9%–21.5%) incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission for CHF patients, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies. However, the meta-analysis revealed substantial heterogeneity, potentially attributable to variations in study sample sizes, diverse data sources, and differences in heart failure subtypes across the included studies (30). Subgroup analysis revealed regional variations in the incidence of 30-day unplanned readmissions among patients with CHF. Africa demonstrated the highest incidence, followed by North America, while Asia showed the lowest rates. These geographical disparities can be explained by differences in healthcare infrastructure, socioeconomic conditions, and post-discharge care systems. In many African countries, economic instability,limited hospital capacity, shortages of trained personnel, and uneven distribution of resources make structured follow-up difficult and raise the likelihood of readmission (29). In contrast, North America benefits from advanced medical technologies and specialized heart failure programs, yet care coordination remains inconsistent (31). Fragmented systems, variable insurance coverage, and gaps in follow-up planning often leave patients vulnerable to deterioration once they leave the hospital (32). Some high-income Asian nations present another picture: well-organized primary care networks and strong hospital–community links may facilitate smoother transitions, though inequities persist in rural and low-income areas. Meanwhile, emerging strategies in Asia, including government-funded home visits, community health worker involvement, and integrated electronic health records—suggest promising avenues for strengthening continuity of care (33). Moreover, a significant methodological issue is to whether CHF was recognized as the primary cause of hospitalization or as a secondary diagnosis alongside other acute conditions. Numerous studies failed to distinctly differentiate among these diagnostic groups (34). For example, clinical practice reveals that while some chronic patients are admitted with other symptoms as the primary diagnosis, these symptoms are often triggered by heart failure. Therefore, it is challenging to strictly distinguish whether patients are admitted with CHF as the primary or secondary diagnosis (35). This discrepancy may have resulted in case-mix heterogeneity. Including both diagnostic groups indiscriminately may consequently either inflate or deflate the actual incidence of CHF readmissions (36). This meta analysis notably did not find any pertinent studies from Europe; nonetheless, of the four principal papers discovered regarding post-discharge “home” BNP/NT-proBNP follow-up, three originated from the UK (37–39). This presents a paradox: although European researchers have significantly contributed to assessing the feasibility and potential advantages of home BNP monitoring, they have not supplied analogous intra-hospital datasets for indicators predicting early readmission. In contrast, researchers from several regions, including North America, Asia, and Africa, have amassed substantial in-hospital prognostic data but have contributed minimally to the evidence base for home BNP monitoring post-discharge. The disparities in location indicate an imbalance in the global research landscape regarding CHF management. Some areas focus more on inpatient risk profiling, while others focus more on outpatient biomarker-guided care. To fill in these gaps, countries will need to work together to pay attention to the incidence of readmission, find in-hospital predictors and evaluate structured post-discharge interventions. This will make sure that there is more complete and regionally representative evidence to guide practice (40).

4.2 Risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF are high and should be better identified

4.2.1 Demographic factors

The results of meta-analysis showed that age ≥65 years was a risk factor for the 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF. In 2020, a study showed that HF was one of the most common diagnoses in hospitalized older patients aged >65 years (41). According to the Report on Cardiovascular Health and Diseases in China: An Updated Summary of 2023, the risk of HF prevalence increases with age, 3.09% in people aged 60–79 years and 7.55% in people over 80 years (42). In 2015, a study showed that the incidence of HF was significantly higher in the elderly than in the young and middle-aged, with the risk of incidence increasing approximately 1-fold for every 10-year increase in age (43). However, the age dispersion of study populations may also lead to potential selection bias. Inconsistent reporting of age-stratified analyses across studies impeded the assessment of age-specific risk gradients for readmission. Older persons often exhibit heightened frailty, cognitive impairments, and functional decline, which impact post-discharge self-management and compliance. In the absence of appropriate age-stratified reporting, aggregated estimates may obscure clinically important disparities in risk profiles between younger and older geriatric patients.

4.2.2 Disease-related factors

This study found that CKD, DM, AF, CHD, NYHA, and cardiomyopathy were risk factors for the 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF. Individuals with ischemic CHF, frequently attributed to CAD, typically experience concurrent health issues, including DM, CKD, and peripheral vascular disease (PVD). The presence of these comorbidities, coupled with the risk of recurrent ischemia or arrhythmia, may increase the likelihood of rapid deterioration in the patient's condition, necessitating hospital readmission (44). Conversely, non-ischemic etiologies such as cardiomyopathy may have a distinct trajectory, with decompensation frequently associated with increasing pump failure, arrhythmias, or uncontrolled hypertension. Numerous observational studies have demonstrated that ischemia etiologies are associated with elevated short-term readmission and death rates compared to non-ischemic causes (44). The strength of this association may be contingent upon the adherence of medical care to established recommendations. From a clinical standpoint, distinguishing between ischemia and non-ischemic congestive heart failure is essential for risk evaluation and determining follow-up intensity. Ischemic CHF patients may benefit from enhanced post-hospitalization monitoring, secondary prevention programs targeting coronary disease, and early cardiac rehabilitation. Conversely, the care of non-ischemic instances may concentrate on regulating the underlying conditions that precipitated the issue (45). Moreover, the distribution and impact of comorbidities constitute a considerable source of potential bias. The majority of individuals with CHF, particularly the elderly, possess many chronic health conditions. These comorbidities influence both the probability of initial hospitalization and the risk of subsequent early readmission (46). Nevertheless, the studies analyzed demonstrated considerable diversity in their definitions, measures, and adjustments for comorbidities, leading to residual confounding. In other cases, comorbidities were recorded only after discharge or obtained from administrative databases, which may result in an underrepresentation of their prevalence and reduce the comparability of findings between studies.

4.2.3 Drug factors

The results of the meta-analysis showed that the use of beta-blockers, loop diuretics, and thiazides at discharge was a risk factor for 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF. Beta-blockers are important for reducing long-term mortality and hospitalization rates. Nevertheless, Aizawa et al. (23) claim that initiating or escalating the dosage may temporarily exacerbate symptoms due to their negative inotropic and chronotropic effects, particularly in those with advanced disease. This may partially clarify the short-term readmissions observed after discharge. Loop diuretics are crucial for alleviating congestion; however, their use often signifies heightened disease severity or diuretic resistance, both of which are indicators of adverse outcomes (47). The observed correlation likely reflects the severity of the underlying condition rather than a direct negative effect of the medication. Thiazide diuretics are infrequently utilized as first-line therapies for congestive heart failure; nevertheless, they could be employed in conjunction with loop diuretics to manage diuretic resistance or regulate refractory volume overload. The frequent use of thiazides typically indicates that patients belong to a cohort with more severe or treatment-resistant conditions, rather than suggesting that thiazides themselves elevate the risk of readmission. Thiazides are frequently administered in conjunction with other medications, such as ACE inhibitors or ARBs, complicating the assessment of their individual effects (48). The observed link between thiazide consumption and readmission likely indicates confounding by indication, where thiazide prescription serves as a clinical marker of advanced or complex heart failure care rather than a direct risk factor.

When considered comprehensively, these findings showed that medication-related predictors of readmission should be analyzed within the context of the clinical situation. Future prospective studies incorporating dosage, treatment sequence, and outpatient follow-up data are necessary to clarify these connections.

4.2.4 Laboratory indications

The results of the meta-analysis showed that LVEF < 40% was a risk factor for unplanned 30-day readmission in patients with CHF. While systolic dysfunction is intuitively associated with negative outcomes, the precise processes by which reduced LVEF results in early readmission remain poorly understood. The variable reporting on functional status, self-care ability, or outpatient follow-up complicates the evaluation of whether LVEF serves as a true physiological driver of readmission or merely as an indicator of disease chronicity and management intensity. Additional study integrating echocardiographic measures with longitudinal clinical data is essential to clarify this link. In addition, although our meta-analysis did not initially include studies evaluating home-based monitoring of BNP or NT-proBNP, existing studies (37–39) have proposed that serial, post-discharge measurement of these biomarkers in the home setting may offer dynamic, real-time information on a patient's hemodynamic status and volume profile. Such an approach could enable earlier identification of subclinical deterioration and prompt therapeutic adjustment by specialists, heart failure nurses, and primary care physicians in a coordinated fashion. BNP or NT-proBNP are well-established prognostic indicators in congestive heart failure, and their serial assessment may more accurately represent disease progression than isolated in-hospital measurements. When incorporated into a systematic follow-up strategy, home BNP/NT-proBNP monitoring could potentially reduce the incidence of unplanned readmissions by facilitating earlier intervention. This method, while not yet often utilized in standard clinical practice, merits additional investigation in forthcoming trials and meta-analyses due to its potential as a low-burden, biomarker-guided follow-up instrument.

4.2.5 Hospitalization-related factors

This study found that shorter LOS or longer LOS were risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF. Some studies (24, 49) have shown that shorter LOS may provide insufficient medical care; patients with longer LOS are typically elderly and very sick, as their organ function has deteriorated and they have suffered a physical injury from a severe disease. These circumstances can lead to a worse recovery and a lower body's tolerance to external stimuli, which may cause heart attacks during emergency events and necessitate readmission.

5 Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the global incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission in patients with CHF and synthesize the evidence regarding its risk factors. Using random-effects models, subgroup analyses, and heterogeneity assessments made the pooled estimates stronger by taking into account differences between studies. Stratified analyses based on region, comorbidities, and treatment-related factors enhanced the clinical significance of the findings by pinpointing subgroups with an elevated risk of readmission. This review offers a globally representative perspective on early readmission patterns in CHF by synthesizing evidence from various healthcare systems across continents.

However, this study also had some limitations. First, one significant limitation of this meta analysis is the absence of data from Europe, particularly regarding the various hospital factors (symptoms, signs, clinical scores, and BNP levels) that may affect 30-day readmission rates in CHF patients. European data, which could yield insights into this extensive and varied population, are conspicuously limited in the evaluated studies. This absence could reflect a lack of focus in European healthcare policies on addressing the post-discharge readmission problem, despite its significant economic burden. Second, we limited our analysis to published works in Chinese and English. This criterion may have contributed to some publication bias in the results. Third, due to variations in outcome measures and analytical methods, the available HR and OR data were insufficient to conduct a thorough examination of all risk factors, even in studies with large sample sizes. Moreover, several included studies had small samples (<30 cases), which may reduce the reliability of the pooled estimates and limit confidence in the findings. However, we retained these studies to preserve the completeness of available evidence and because their exclusion did not materially change the pooled results in sensitivity analyses. Lastly, given the insufficient number of studies, the meta analysis and subgroup analysis on the effect size and heterogeneity of some risk factors’ impact could not be conducted.

6 Implications for practice and research

This study found several predictors of 30-day unplanned readmission in CHF, and these findings have significant implications for healthcare policy. First, standardized discharge risk assessment, integrating these variables into proven models, could inform the prioritizing of high-risk patients for rigorous follow-up. Policies should guarantee organized early post-discharge communication within 7–14 days through clinic visits or telemedicine to assess stability and compliance (50). Second, multidisciplinary HF teams—consisting of cardiologists, nurses, pharmacists, nutritionists, and primary care physicians can enhance the management of HF and comorbidities, especially in elderly patients or those with CKD or DM (51). Hospital protocols should ensure the beginning and optimization of guideline-directed therapy prior to discharge, with mechanisms for post-discharge titration established. Third,assistance for home-based monitoring, encompassing BNP/NT-proBNP tests, daily weight assessments, and remote blood pressure surveillance, is crucial for patients with diminished LVEF or other comorbidities (52). Such measures could shift CHF care from reactive to preventive, improving outcomes and resource efficiency.

7 Conclusions

In our meta-analysis, we found that the incidence of 30-day unplanned readmission for patients with CHF was 17.7%. This finding suggested that age ≥65, COPD, CKD, DM, AF, CHD, cardiomyopathy, NYHA class ≥III or IV, beta-blockers, loop diuretics, thiazides, LVEF < 40%, and shorter LOS and longer LOS were significant independent risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmission in CHF patients. Clinical staff can refer to the results of this study to understand the risk factors associated with the readmission of CHF patients, identify areas of high readmission incidence, and provide early warning to the clinic. This will enable them to take scientific preventive measures to reduce the incidence of readmission among CHF patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TC: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. HS: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported in part by grant 202202-027 from Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences Youth Science Fund Cultivation Grant Program. Another portion was supported by the 2025 General Project of Shandong Humanities and Social Sciences Research Fund. Due to the special nature of this project, it currently lacks a grant number.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1663018/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Cui L Wei X Liang T Yan R Du M Alimire T et al Factors influencing unplanned readmission within 30 days in patients with heart failure and their predictive value: a prospective study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2025) 25(1):269. 10.1186/s12872-025-04674-z

2.

Malhotra C Chaudhry I Keong YK Sim KLD . Multifactorial risk factors for hospital readmissions among patients with symptoms of advanced heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. (2024) 11(2):1144–52. 10.1002/ehf2.14670

3.

Lim YMF Ong SM Koudstaal S Hwong WY Liew HB Rajadurai J et al Trends for readmission and mortality after heart failure hospitalisation in Malaysia, 2007 to 2016. Glob Heart. (2022) 17(1):20. 10.5334/gh.1108

4.

Xiao H Quan H Pan S Yin B Luo W Tang M et al Incidence, causes and risk factors for 30-day readmission after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a retrospective study of 2,023 patients. Sci Rep. (2018) 8(1):10582. 10.1038/s41598-018-28850-8

5.

Khan MS Sreenivasan J Lateef N Bougergi MS Greene SJ Ahmad T et al Trends in 30- and 90-day readmission rates for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. (2021) 14(4):e008335. 10.1161/circheartfailure.121.008335

6.

Lv Q Zhang X Wang Y Xu X He Y Liu J et al Multi-trajectories of symptoms and their associations with unplanned 30-day hospital readmission among patients with heart failure: a longitudinal study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2024) 23(7):737–45. 10.1093/eurjcn/zvae038

7.

Stang A . Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. (2010) 25(9):603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

8.

Ma LL Wang YY Yang ZH Huang D Weng H Zeng XT . Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: what are they and which is better?Mil Med Res. (2020) 7(1):7. 10.1186/s40779-020-00238-8

9.

Alzaghari O Wallace DC . The impact of physiological factors on 30-day unplanned rehospitalization in adults with heart failure. J Community Health Nurs. (2019) 36(1):31–41. 10.1080/07370016.2018.1555308

10.

Arora S Patel P Lahewala S Patel N Patel NJ Thakore K et al Etiologies, trends, and predictors of 30-day readmission in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. (2017) 119(5):760–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.11.022

11.

Carlson B Hoyt H Gillespie K Kunath J Lewis D Bratzke LC . Predictors of heart failure readmission in a high-risk primarily hispanic population in a rural setting. J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2019) 34(3):267–74. 10.1097/jcn.0000000000000567

12.

Fudim M O'Connor CM Dunning A Ambrosy AP Armstrong PW Coles A et al Aetiology, timing and clinical predictors of early vs. Late readmission following index hospitalization for acute heart failure: insights from ASCEND-HF. Eur J Heart Fail. (2018) 20(2):304–14. 10.1002/ejhf.1020

13.

Kwok CS Seferovic PM Van Spall HG Helliwell T Clarson L Lawson C et al Early unplanned readmissions after admission to hospital with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. (2019) 124(5):736–45. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.05.053

14.

Mirkin KA Enomoto LM Caputo GM Hollenbeak CS . Risk factors for 30-day readmission in patients with congestive heart failure. Heart Lung. (2017) 46(5):357–62. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.06.005

15.

Gusto JM Prehn AW . Socioeconomic and health-related factors affecting congestive heart failure readmissions. Fam Community Health. (2023) 46(1):79–86. 10.1097/fch.0000000000000350

16.

Jain A Arora S Patel V Raval M Modi K Arora N et al Etiologies and predictors of 30-day readmission in heart failure: an updated analysis. Int Heart Fail. (2023) 5(3):159–68. 10.36628/ijhf.2023.0015

17.

Jha AK Ojha CP Krishnan AM Paul TK . Thirty-day readmission in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: insights from the nationwide readmission database. World J Cardiol. (2022) 14(9):473–82. 10.4330/wjc.v14.i9.473

18.

Kim MJ Tabtabai SR Aseltine RH Jr . Predictors of 30-day readmission in patients hospitalized with heart failure as a primary versus secondary diagnosis. Am J Cardiol. (2023) 207:407–17. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.08.111

19.

Shao L Wang Y Gao B Zou H Xu J Cai L . Analysis of factors influencing readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge in patients with heart failure. Nurs Rehabil. (2021) 20(02):26–9.

20.

Hu J . Construction of a predictive model for 30-day rehospitalization risk in heart failure based on clinical data. Bachelor's degree. Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing (2022). Available online at:http://link--cnki--net--https.cnki.qfsy.qfclo.com:7002/doi/10.27674/d.cnki.gcyku.2022.001750

21.

Zhang Y Wang H Yin C Shu T Yu J Jian C et al Development of a prediction model for the risk of 30-day unplanned readmission in older patients with heart failure: a multicenter retrospective study. Nutr, Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2023) 33(10):1878–87. 10.1016/j.numecd.2023.05.034

22.

Zhuang D Zhuang L Chen H Zheng B Liu L . Analysis of risk factors for unplanned multiple admissions in patients with chronic heart failure. Knowl Cardiovasc Dis Prev Treat. (2022) 12(23):8–11. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-3015(x).2022.23.002 (in Chinese).

23.

Aizawa H Imai S Fushimi K . Factors associated with 30-day readmission of patients with heart failure from a Japanese administrative database. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2015) 15:134. 10.1186/s12872-015-0127-9

24.

Miyazaki D Tarasawa K Fushimi K Fujimori K . Risk factors with 30-day readmission and the impact of length of hospital stay on it in patients with heart failure: a retrospective observational study using a Japanese national database. Tohoku J Exp Med. (2023) 259(2):151–62. 10.1620/tjem.2022.J114

25.

Chung JE Noh E Gwak HS . Evaluation of the predictors of readmission in Korean patients with heart failure. J Clin Pharm Ther. (2017) 42(1):51–7. 10.1111/jcpt.12471

26.

Lim NK Lee SE Lee HY Cho HJ Choe WK Kim H et al Risk prediction for 30-day heart failure-specific readmission or death after discharge: data from the Korean acute heart failure (KorAHF) registry. J Cardiol. (2019) 73(2):108–13. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2018.07.009

27.

Deeka H Skouri H Noureddine S . Readmission rates and related factors in heart failure patients: a study in Lebanon. Collegian. (2016) 23(1):61–8. 10.1016/j.colegn.2014.11.001

28.

Sharma V Kulkarni V McAlister F Eurich D Keshwani S Simpson SH et al Predicting 30-day readmissions in patients with heart failure using administrative data: a machine learning approach. J Card Fail. (2022) 28(5):710–22. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.12.004

29.

Ayenew B Kumar P Hussein A . Incidence and predictors of unplanned 30-day hospital readmissions among heart failure patients in Ethiopia: a 5-year retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. (2024) 14(1):23473. 10.1038/s41598-024-71257-x

30.

Dharmarajan K Hsieh AF Lin Z Bueno H Ross JS Horwitz LI et al Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. (2013) 309(4):355–63. 10.1001/jama.2012.216476

31.

Sadiq AM Chamba NG Sadiq AM Shao ER Temu GA . Clinical characteristics and factors associated with heart failure readmission at a tertiary hospital in North-Eastern Tanzania. Cardiol Res Pract. (2020) 2020:2562593. 10.1155/2020/2562593

32.

Duran K Copel LC Hinkle JL . Examining the implications of social determinants of health on hospital readmission for patients with heart failure: a scoping review. Disc Soc Sci Health. (2025) 5(1):121. 10.1007/s44155-025-00284-4

33.

Koontalay A Samai T Samutalai C Onthuam W Fonghiranrat D . Effectiveness of nurse-led heart failure transitional care services in improving clinical outcomes and applicability to low-resource settings: a meta-analysis. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. (2024) 13(2):60–8. 10.4103/WHO-SEAJPH.WHO-SEAJPH_26_23

34.

Blecker S Paul M Taksler G Ogedegbe G Katz S . Heart failure–associated hospitalizations in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 61(12):1259–67. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.038

35.

Bueno H Goñi C Salguero-Bodes R Palacios B Vicent L Moreno G et al Primary vs. Secondary heart failure diagnosis: differences in clinical outcomes, healthcare resource utilization and cost. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:818525. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.818525

36.

Carey SA Bass K Saracino G East C Felius J Grayburn PA et al Probability of accurate heart failure diagnosis and the implications for hospital readmissions. Am J Cardiol. (2017) 119(7):1041–6. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.12.010

37.

McDonald K Troughton R Dahlström U Dargie H Krum H Meer P et al Daily home BNP monitoring in heart failure for prediction of impending clinical deterioration: results from the HOME HF study. Eur J Heart Fail. (2018) 20(3):474–80. 10.1002/ejhf.1053

38.

Maisel A Barnard D Jaski B Frivold G Marais J Azer M et al Primary results of the HABIT trial (heart failure assessment with BNP in the home). J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 61(16):1726–35. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.052

39.

Chami J Fleming S Taylor CJ Bankhead CR James T Shine B et al Point-of-care NT-proBNP monitoring for heart failure: observational feasibility study in primary care. BJGP Open. (2022) 6(3):1–10. 10.3399/bjgpo.2022.0005

40.

Ran J Zhou P Wang J Zhao X Huang Y Zhou Q et al Global, regional, and national burden of heart failure and its underlying causes, 1990–2021: results from the global burden of disease study 2021. Biomark Res. (2025) 13(1):16. 10.1186/s40364-025-00728-8

41.

Nair N . Epidemiology and pathogenesis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Rev Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 21(4):531–40. 10.31083/j.rcm.2020.04.154

42.

Center For Cardiovascular Diseases The Writing Committee Of The Report On Cardiovascular H, Diseases In China N. Report on cardiovascular health and diseases in China 2023: an updated summary. Biomed Environ Sci. (2024) 37(9):949–92. 10.3967/bes2024.162

43.

Feldman DE Platt R Déry V Kapetanakis C Lamontagne D Ducharme A et al Seasonal congestive heart failure mortality and hospitalisation trends, Quebec 1990–1998. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2004) 58(2):129–30. 10.1136/jech.58.2.129

44.

Zhang ZH Meng FQ Hou XF Qian ZY Wang Y Qiu YH et al Clinical characteristics and long-term prognosis of ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Indian Heart J. (2020) 72(2):93–100. 10.1016/j.ihj.2020.04.004

45.

Manzi L Buongiorno F Narciso V Florimonte D Forzano I Castiello DS et al Acute heart failure and non-ischemic cardiomyopathies: a comprehensive review and critical appraisal. Diagnostics. (2025) 15(5):1–39. 10.3390/diagnostics15050540

46.

Murru V Belfiori E Sestu A Casanova A Serra C Scuteri A . Patterns of comorbidities differentially impact on in-hospital outcomes in heart failure patients. BMC Geriatr. (2025) 25(1):371. 10.1186/s12877-025-06002-8

47.

Wu L Rodriguez M El Hachem K Krittanawong C . Diuretic treatment in heart failure: a practical guide for clinicians. J Clin Med. (2024) 13(15):1–30. 10.3390/jcm13154470

48.

Gogikar A Nanda A Janga LSN Sambe HG Yasir M Man RK et al Combination diuretic therapy with thiazides: a systematic review on the beneficial approach to overcome refractory fluid overload in heart failure. Cureus. (2023) 15(9):e44624. 10.7759/cureus.44624

49.

Arundel C Lam PH Faselis C Sheriff HM Dooley DJ Morgan C et al Length of stay and readmission in older adults hospitalized for heart failure. Arch Med Sci. (2021) 17(4):891–9. 10.5114/aoms.2019.89702

50.

Radakrishnan A Zegarra D Naidu I Every H Makam S Pant K et al Evaluating heart failure postdischarge follow-up: a single-center experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2025) 85(12_Supplement):1576. 10.1016/S0735-1097(25)02060-1

51.

Craigo CL Dow CM Malkhasian YM Minissian MB Zadikany R Zimmer R . A multidisciplinary transition of care approach to reduce 30-day readmissions in heart failure patients. Heart Lung. (2025) 71:76–80. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2025.03.001

52.

Stevenson Lynne W Ross Heather J Rathman Lisa D Boehmer John P . Remote monitoring for heart failure management at home. JACC. (2023) 81(23):2272–91. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.04.010

Summary

Keywords

chronic heart failure, readmission, incidence, risk factors, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation

Chen T, Wang R and Song H (2026) Incidence and influencing factors of 30-day unplanned readmission in chronic heart failure patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1663018. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1663018

Received

10 July 2025

Revised

22 November 2025

Accepted

26 November 2025

Published

14 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Filippo Valbusa, Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital (IRCCS), Italy

Reviewed by

Angelo Scuteri, University of Cagliari, Italy

Rishabh Kumar Kumar Rana, Shaheed Nirmal Mahto Medical College and Hospital, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Chen, Wang and Song.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Hongxia Song 18670495009@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.