Abstract

Background:

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is an ophthalmic emergency that signals a markedly increased risk of ischemic stroke and systemic vascular events. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) offers advanced imaging of carotid plaque vulnerability, but its diagnostic utility in CRAO remains inadequately explored.

Objective:

To evaluate the diagnostic value of CEUS in identifying vulnerable carotid plaques in patients with acute CRAO.

Methods:

In this retrospective, propensity score–matched study, 110 patients with acute CRAO and 110 matched healthy controls were enrolled. Matching was performed for age, sex, and key cardiovascular risk factors. All participants underwent standardized carotid duplex ultrasound and CEUS, with plaque vulnerability assessed by intraplaque neovascularization grading. Logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors of CRAO. Diagnostic performance was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Results:

Compared to controls, CRAO patients had a significantly higher prevalence of vulnerable carotid plaques (CEUS enhancement scores ≥2: 85.5% vs. 21.8%, p < 0.001). Key ultrasound predictors of CRAO included increased intima-media thickness, plaque length, higher peak systolic velocity, resistance index, pulsatility index, and CEUS enhancement score. The combined diagnostic model, integrating both conventional and CEUS parameters, demonstrated superior accuracy (AUC = 0.916) compared to conventional ultrasound (AUC = 0.738) or CEUS alone (AUC = 0.754).

Conclusions:

CEUS significantly improves the detection of vulnerable carotid plaques in patients with acute CRAO and, when combined with conventional ultrasound, markedly enhances diagnostic performance. Incorporating CEUS into routine vascular assessment may facilitate better risk stratification and inform personalized secondary prevention strategies for CRAO patients.

1 Introduction

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is an ophthalmic emergency characterized by sudden, painless monocular vision loss due to obstruction of the central retinal artery (1, 2). While traditionally considered an isolated ocular event, CRAO is now increasingly recognized as an indicator of elevated risk for subsequent ischemic stroke and cardiovascular disease (3). Accordingly, current guidelines classify CRAO as a subtype of ocular stroke, necessitating urgent vascular assessment and the implementation of secondary prevention strategies (4). Embolic events account for a significant proportion of CRAO cases, with unstable atherosclerotic plaques in the ipsilateral carotid artery frequently serving as the embolic source (5). While conventional duplex ultrasonography can assess the degree of luminal stenosis, it provides limited information regarding plaque composition and vulnerability—key factors in determining embolic potential (6).

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) addresses these limitations by delineating plaque morphology and visualizing intraplaque neovascularization—an established marker of plaque instability (7, 8). Although CEUS is increasingly used for risk stratification in ischemic stroke and cardiovascular disease, its clinical utility in CRAO remains insufficiently characterized (9).

In this propensity score–matched case-control study, we aimed to evaluate the diagnostic utility of CEUS for identifying vulnerable carotid plaques in patients with acute CRAO, as compared to matched healthy controls.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and participants

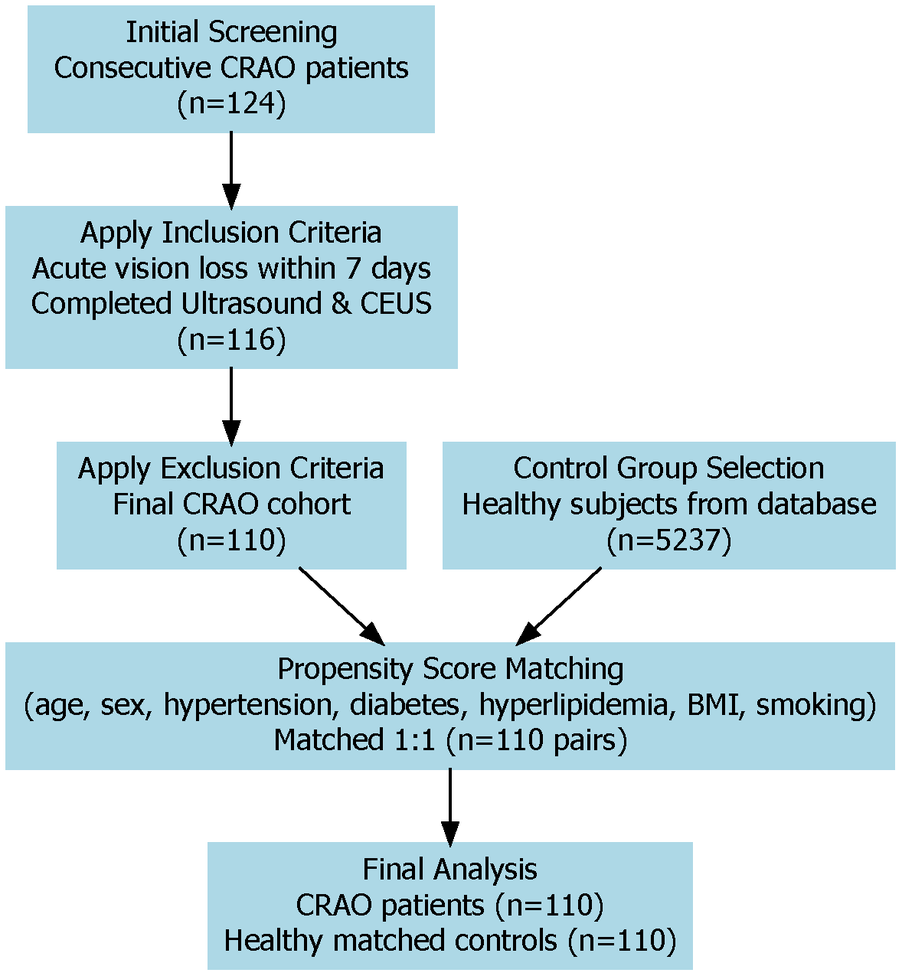

We conducted a retrospective observational study at a tertiary medical institution. All consecutive patients diagnosed with acute CRAO between January, 2023, and December, 2024, were systematically screened for eligibility. The diagnosis of CRAO was established through comprehensive clinical assessments and fundus fluorescein angiography in adherence to the 2021 American Heart Association Scientific Statement guidelines. Following stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, 110 patients with confirmed CRAO constituted the case cohort. The control group consisted of 110 healthy individuals selected from the hospital's health examination database, matched 1:1 with CRAO patients by age, sex, and major cardiovascular risk factors via propensity score matching, ensuring balanced baseline characteristics. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jinan People's Hospital (Approval No. 2025-LW-045). See Figure 1 for the detailed flow chart.

Figure 1

Study flow chart of patient selection and matching. This diagram shows how patients with CRAO and healthy controls were chosen for the study. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 110 CRAO patients and 110 matched controls were enrolled using propensity score matching. Both groups received carotid ultrasound and CEUS examinations.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible patients presented with acute-onset monocular vision loss within seven days, had CRAO confirmed by ophthalmologic evaluation and angiographic findings, and underwent bilateral carotid duplex ultrasound and CEUS within 72 h of diagnosis. Exclusion criteria encompassed prior carotid interventions (endarterectomy or stenting), known autoimmune vasculitis or coagulopathies, cardiac embolic sources such as atrial fibrillation with documented left atrial thrombus, or incomplete clinical or ultrasound data.

2.3 Propensity score matching methodology

To mitigate selection bias and ensure comparability of baseline characteristics, propensity scores were computed using logistic regression models. Included covariates were age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, body mass index, and current smoking status. We utilized nearest-neighbor matching with a caliper width of 0.2 standard deviations and no replacement, ultimately achieving 110 balanced pairs for analysis.

2.4 Carotid duplex ultrasound and CEUS protocol

All participants underwent standardized carotid duplex ultrasound using a 7–15 MHz linear array transducer. The following parameters were systematically evaluated: intima-media thickness (IMT), plaque presence and morphology, plaque length according to NASCET criteria, peak systolic velocity (PSV), resistance index (RI), and pulsatility index (PI).

Immediately after conventional ultrasound assessment, CEUS was performed using an intravenous bolus of 2.4 ml SonoVue contrast agent, maintaining a low mechanical index (<0.10) during three minutes of continuous imaging. Intraplaque neovascularization was evaluated via a validated semi-quantitative grading system: grade 0 (no enhancement), grade 1 (punctate enhancement), grade 2 (punctate enhancement with one to two short linear foci), and grade 3 (linear or extensive traversing enhancement). Plaques receiving grades 2 or 3 were categorized as “vulnerable,” indicative of substantial intraplaque neovascularization and heightened embolic potential, in accordance with previously validated criteria (10). Two experienced, board-certified sonographers independently performed plaque grading, blinded to clinical data, with adjudication by a third senior reviewer in cases of discrepancy to ensure high interobserver reliability.

2.5 Sample size estimation

Based on preliminary data suggesting a 40% difference in vulnerable plaque prevalence between CRAO patients and controls, a minimum of 94 subjects per group was required for 90% power at a two-sided alpha of 0.05. To account for potential attrition, 110 participants were enrolled in each group.

2.6 Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.1). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) and compared using t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests as appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, analyzed by chi-square or Fisher's exact test. Binary logistic regression identified independent predictors of CRAO, reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Diagnostic performance was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC). A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline clinical characteristics

A total of 220 subjects were included, comprising 110 patients with acute CRAO and 110 healthy controls matched for age, sex, and major cardiovascular risk factors using propensity score matching (Table 1). The two groups were well balanced in terms of demographic features and baseline cardiovascular risk profiles, with no significant differences in age, sex distribution, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, or alcohol use (all p > 0.05). Laboratory parameters—including white blood cell, neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet, fibrinogen, and HDL cholesterol—were also comparable. Notably, the CRAO group exhibited higher levels of creatinine, uric acid, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol (all p < 0.05); however, most standardized mean differences remained below 0.2, indicating minimal residual imbalance. Overall, the two groups were sufficiently comparable, minimizing potential confounders before carotid ultrasound evaluation.

Table 1

| Variable | Level | Control (N = 110) | CRAO (N = 110) | t/x 2 | p-value | SMD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | Female | 43 (39.1) | 45 (40.9) | 0.019 | 0.891 | 0.037 |

| Male | 67 (60.9) | 65 (59.1) | ||||

| Age [mean (SD)] | 56.89 (9.49) | 56.46 (11.84) | 0.301 | 0.768 | 0.040 | |

| BMI [mean (SD)] | 26.02 (3.20) | 26.30 (3.59) | −0.611 | 0.541 | 0.082 | |

| Hypertension (%) | No | 57 (51.8) | 61 (55.5) | 0.165 | 0.685 | 0.073 |

| Yes | 53 (48.2) | 49 (44.5) | ||||

| Diabetes (%) | No | 95 (86.4) | 92 (83.6) | 0.143 | 0.706 | 0.076 |

| Yes | 15 (13.6) | 18 (16.4) | ||||

| Smoking (%) | No | 94 (85.5) | 97 (88.2) | 0.159 | 0.690 | 0.081 |

| Yes | 16 (14.5) | 13 (11.8) | ||||

| Drinking (%) | No | 101 (91.8) | 101 (91.8) | 0.000 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 9 (8.2) | 9 (8.2) | ||||

| WBC [mean (SD)] | 6.32 (1.67) | 6.09 (1.75) | 1.00 | 0.326 | 0.133 | |

| Neutrophil [mean (SD)] | 3.55 (1.19) | 3.64 (1.29) | −0.54 | 0.596 | 0.072 | |

| Lymphocyte [mean (SD)] | 1.78 (0.56) | 1.83 (0.64) | −0.62 | 0.536 | 0.084 | |

| Platelet [mean (SD)] | 210.97 (49.17) | 201.66 (59.34) | 1.27 | 0.207 | 0.171 | |

| Creatinine [mean (SD)] | 63.23 (12.70) | 73.96 (22.41) | −4.37 | <0.001 | 0.589 | |

| Triglyceride [mean (SD)] | 1.43 (0.77) | 1.87 (0.93) | −3.82 | <0.001 | 0.517 | |

| Total Cholesterol [mean (SD)] | 4.50 (0.91) | 4.77 (1.03) | −2.06 | 0.045 | 0.271 | |

| HDL [mean (SD)] | 1.12 (0.30) | 1.09 (0.27) | 0.78 | 0.413 | 0.111 | |

| LDL [mean (SD)] | 2.59 (0.66) | 2.84 (0.95) | −2.27 | 0.030 | 0.294 | |

| Fibrinogen [mean (SD)] | 2.88 (0.62) | 2.96 (0.67) | −0.92 | 0.393 | 0.115 |

Baseline characteristics.

3.2 Carotid ultrasound and CEUS findings

Building on the baseline comparability of the study cohorts, conventional carotid duplex ultrasound revealed that CRAO patients had significantly increased IMT, longer plaque length, and higher PSV, RI, and PI compared to controls (all p < 0.001). The prevalence of carotid plaque was also markedly higher among CRAO patients (84.5% vs. 40.0%).

To further characterize plaque vulnerability, CEUS was performed in both groups. A significantly higher proportion of CRAO patients (85.5%) demonstrated plaques with CEUS enhancement scores ≥2, compared to 21.8% in the control group (p < 0.001), see Table 2.

Table 2

| Variable | Level | Control | CRAO | t/x 2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMT [mean (SD)] | 0.84 (0.15) | 1.11 (0.18) | −12.09 | <0.001 | |

| Plaque (%) | No | 66 (60.0) | 17 (15.5) | 44.577 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 44 (40.0) | 93 (84.5) | |||

| Plaque_Length [mean (SD)] | 7.40 (1.68) | 11.36 (2.90) | −12.39 | <0.001 | |

| PSV [mean (SD)] | 96.50 (15.29) | 124.84 (20.11) | −11.77 | <0.001 | |

| RI [mean (SD)] | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | −8.75 | <0.001 | |

| PI [mean (SD)] | 0.99 (0.18) | 1.40 (0.29) | −12.60 | <0.001 | |

| CEUS_Enhancement_Score (%) | 0 | 45 (40.9) | 5 (4.5) | 93.432 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 41 (37.3) | 11 (10.0) | |||

| 2 | 20 (18.2) | 58 (52.7) | |||

| 3 | 4 (3.6) | 36 (32.7) | |||

| Neovascularization_HighRisk (%) | Low | 86 (78.2) | 16 (14.5) | 87.024 | <0.001 |

| High | 24 (21.8) | 94 (85.5) |

Comparison of carotid ultrasound parameters between control and CRAO groups.

3.3 Independent predictors of CRAO

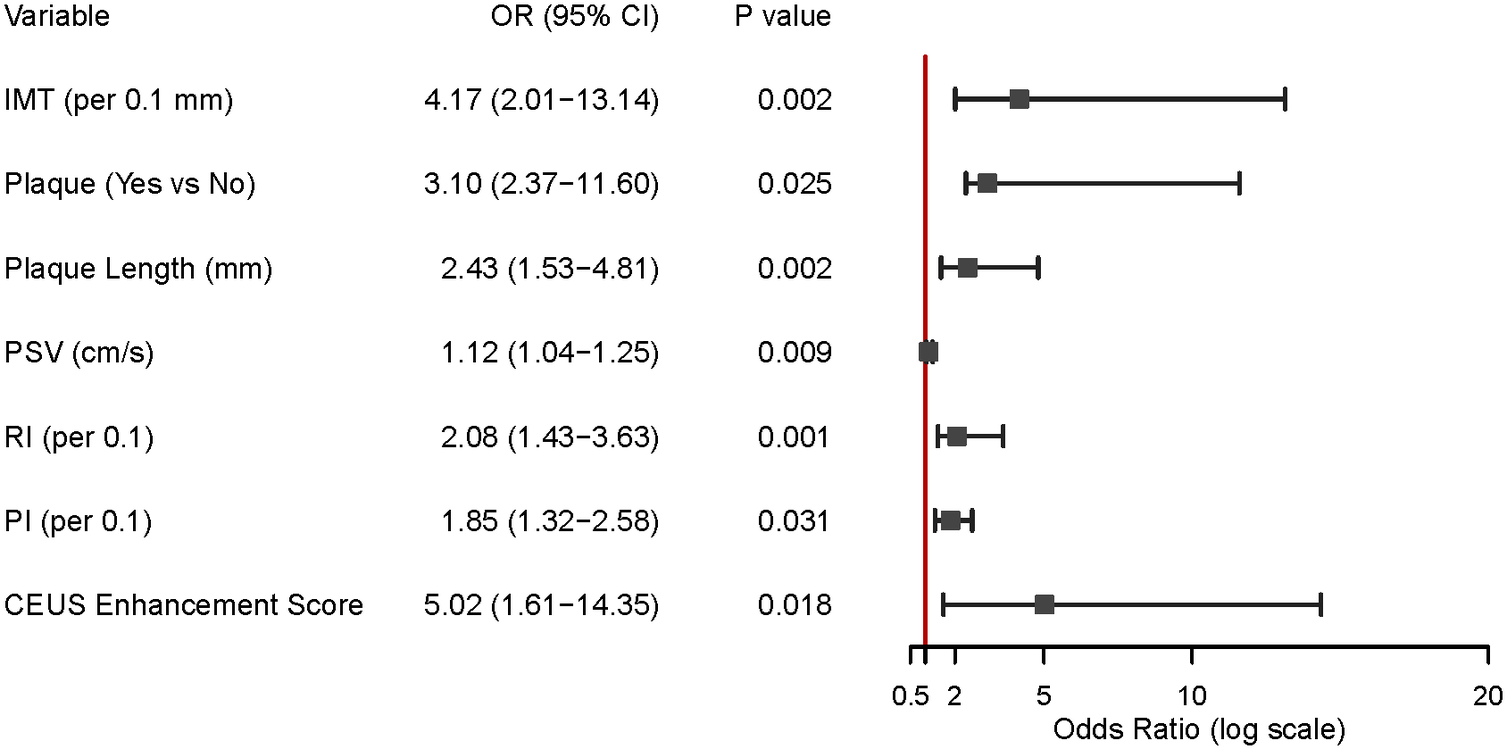

To further delineate the independent risk factors for CRAO, we performed a binary logistic regression analysis incorporating key carotid ultrasound and CEUS parameters as listed in Figure 2. The results demonstrated that IMT was independently associated with CRAO, with each 0.1 mm increase in IMT conferring a more than fourfold increase in risk (OR = 4.17, 95% CI: 2.01–13.04, p = 0.002). The presence of carotid plaque (OR = 3.10, 95% CI: 2.37–11.60, p = 0.025), greater plaque length (OR = 2.43 per mm, 95% CI: 1.53–4.81, p = 0.002), and higher peak systolic velocity (PSV) (OR = 1.12 per cm/s, 95% CI: 1.04–1.25, p = 0.009) were also significant independent predictors of CRAO.

Figure 2

Key carotid ultrasound predictors of CRAO. This figure displays the results of logistic regression analysis, identifying factors that increase CRAO risk. Important predictors include thicker intima-media, the presence and length of carotid plaque, higher peak systolic velocity (PSV), resistance index (RI), pulsatility index (PI), and higher CEUS enhancement scores. All of these measures were independently linked with a greater risk of CRAO.

Additionally, both RI (OR = 2.08 per 0.1 increase, 95% CI: 1.43–3.63, p = 0.001) and PI (OR = 1.85 per 0.1 increase, 95% CI: 1.32–2.58, p = 0.031) were associated with increased CRAO risk. Notably, a higher CEUS enhancement score was a strong independent risk factor for CRAO (OR = 5.02, 95% CI: 1.61–26.35, p = 0.018). (See Figure 2).

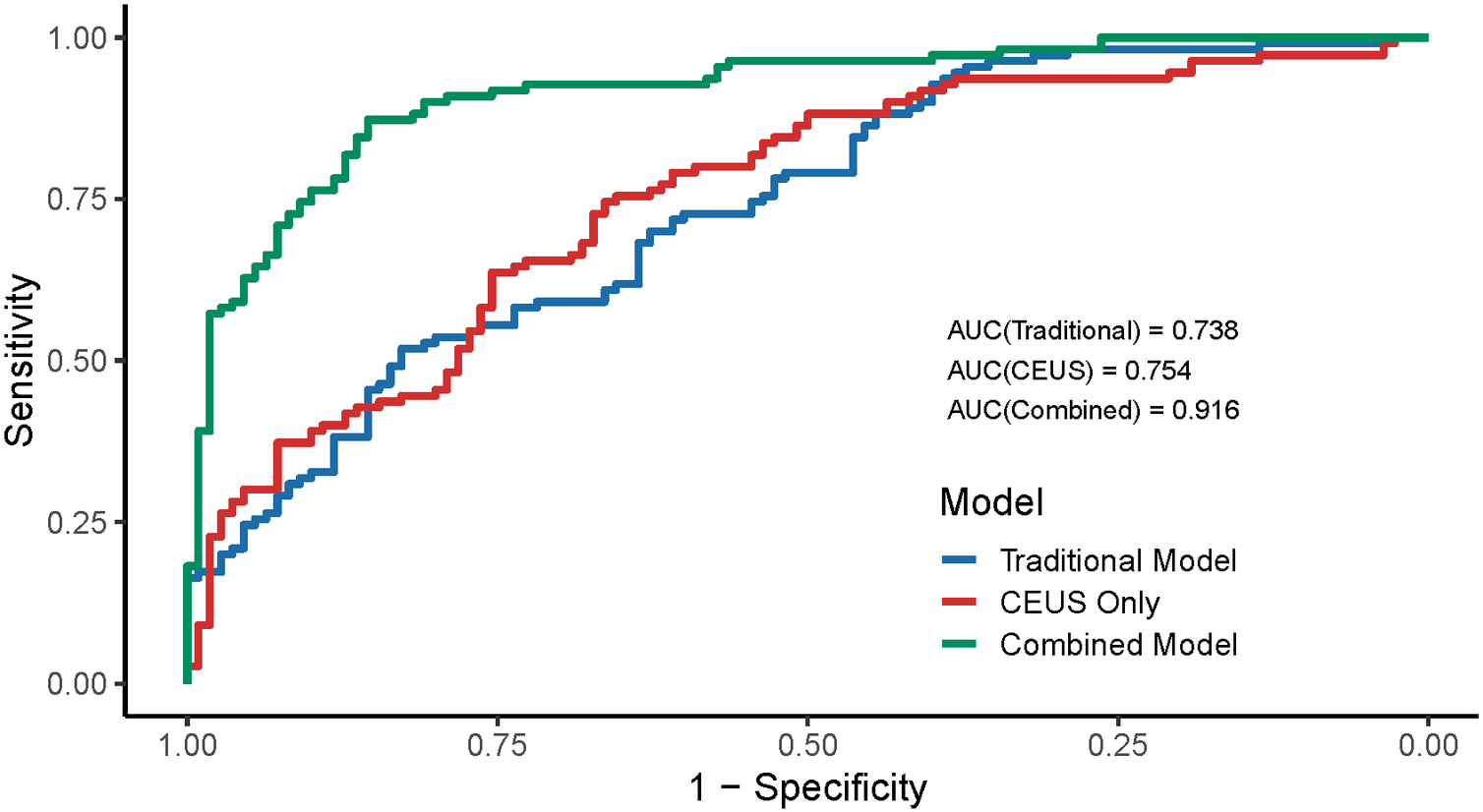

3.4 ROC analysis for diagnostic value

ROC curve analysis was conducted to assess the diagnostic value of different carotid ultrasound models for CRAO (see Table 2 for parameter definitions). The conventional ultrasound model, which included IMT, plaque presence, plaque length, PSV, RI, and PI, demonstrated moderate discriminatory power with an AUC of 0.738. The CEUS-only model, incorporating the CEUS enhancement score as an indicator of intraplaque neovascularization, provided a slightly higher AUC of 0.754, reflecting improved sensitivity and specificity compared to conventional ultrasound alone.

Crucially, the combined diagnostic model, which integrated both conventional ultrasound parameters and CEUS-derived measures, achieved the highest diagnostic accuracy, with an AUC of 0.916 (see Figure 3). These results demonstrate that while both conventional and contrast-enhanced ultrasound independently aid in non-invasive CRAO detection, integrating CEUS significantly improves diagnostic performance.

Figure 3

Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound and CEUS for CRAO. This graph compares the accuracy of three models for diagnosing CRAO: conventional ultrasound alone, CEUS alone, and both methods combined. The combined model had the highest area under the curve (AUC = 0.916), meaning it best distinguishes CRAO patients from controls. Adding CEUS to standard ultrasound greatly improves diagnostic performance.

4 Discussion

In this propensity score–matched observational study, we demonstrated that CEUS significantly enhances the detection of vulnerable carotid plaques in patients presenting with acute CRAO. Notably, CRAO patients exhibited a substantially higher prevalence of plaques graded ≥2 for intraplaque neovascularization compared to healthy controls (85.5% vs. 21.8%). Furthermore, integrating CEUS-derived parameters with conventional ultrasound measures markedly improved diagnostic accuracy, achieving an AUC of 0.916. These findings robustly support our hypothesis that CEUS provides incremental value in identifying high-risk plaques and refining embolic risk stratification in CRAO (11).

Our results extend and reinforce existing literature underscoring CEUS's role in vascular risk stratification, particularly within cerebrovascular pathology. Although widely implemented in assessing symptomatic carotid plaques linked to ischemic stroke, CEUS's application in CRAO remains comparatively under-investigated. Previous studies have documented that CEUS effectively identifies intraplaque neovascularization in 60%–70% of symptomatic plaques, even absent significant stenosis (12). Aligning closely with data derived from acute ischemic stroke populations, our study confirms that elevated CEUS enhancement scores independently correlate with CRAO. This observation highlights the clinical significance of plaque microangiogenesis as an indicator of embolic potential specifically within ophthalmic circulation. The enhanced diagnostic precision achieved through CEUS, particularly when complemented by conventional imaging techniques, aligns with contemporary multicenter findings in stroke research (13).

Moreover, our findings indicate that CRAO patients exhibit significantly elevated serum creatinine, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol levels relative to healthy controls. Elevated creatinine levels may reflect underlying renal dysfunction, a condition intrinsically linked to heightened systemic vascular risk due to accelerated atherosclerotic progression and increased vascular inflammation (14). Similarly, elevated triglycerides likely contribute to plaque instability by promoting lipid accumulation and inflammatory processes within arterial walls (15). Increased LDL cholesterol levels further underscore a well-established relationship with accelerated atherosclerotic plaque formation, serving as a critical, modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity (16). These biochemical differences further support the concept of CRAO as a systemic vascular event with underlying metabolic dysregulation, rather than an isolated ocular condition.

The underlying pathophysiology supporting these findings is biologically coherent. Vulnerable carotid plaques frequently exhibit extensive immature microvascular networks arising from the vasa vasorum, predisposing plaques to hemorrhage, lipid-rich core expansion, and potential fibrous cap disruption (17). CEUS uniquely facilitates the dynamic visualization of these neovessels, providing nuanced insights into plaque instability beyond traditional structural imaging modalities (18). Additionally, observed elevations in intima-media thickness, plaque length, peak systolic velocity, resistance index, and pulsatility index in CRAO patients indicate significant underlying structural and hemodynamic disturbances conducive to microembolization. These cumulative findings reinforce the conceptualization of CRAO as a manifestation of systemic vascular disease rather than a purely ocular event.

Clinically, our findings advocate for the incorporation of CEUS as a minimally invasive imaging tool to enhance early risk stratification for recurrent embolic episodes in CRAO. By identifying high-risk plaques that may evade detection via conventional duplex ultrasound—typically reliant solely on luminal stenosis assessment—CEUS could facilitate individualized secondary prevention strategies (19). Specifically, extensive intraplaque neovascularization detection could prompt intensified antiplatelet or lipid-lowering regimens and, selectively, consideration for carotid revascularization even in the absence of significant stenosis (20). Consequently, CEUS emerges as a valuable imaging biomarker reflective of systemic atherosclerotic burden, holding potential to substantially mitigate subsequent cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events in this vulnerable patient population (21, 22). From a healthcare economics perspective, while CEUS adds incremental cost to routine carotid assessment, the potential to prevent recurrent strokes—which carry substantial healthcare costs and disability burden—may justify this investment. Formal cost-effectiveness analyses incorporating stroke prevention rates, quality-adjusted life years, and healthcare utilization costs would be valuable to inform healthcare policy decisions regarding CEUS implementation in routine CRAO evaluation (23, 24).

Despite these compelling results, our study has several limitations that should be considered. First, as a single-center retrospective study, the generalizability of our findings is limited and subject to inherent biases. However, we attempted to mitigate these issues through rigorous propensity score matching and standardized imaging protocols to enhance internal validity. Second, the interpretation of CEUS requires specialized expertise, which may hinder widespread clinical adoption. Nevertheless, the high interobserver reliability observed in this study suggests that consistent results can be achieved with proper training and experience. Finally, our analysis focused solely on imaging-based phenotypes and did not include long-term clinical outcomes. Therefore, prospective, multicenter studies are needed to validate our findings, determine the prognostic value of CEUS-derived neovascularization scores in CRAO, and assess the long-term effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

5 Conclusion

CEUS significantly enhances the detection of vulnerable carotid plaques in patients with CRAO. Its integration with conventional ultrasound could improve embolic risk stratification and inform individualized secondary prevention strategies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of Jinan People's Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ZS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft. CZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. NY: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. ZH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. BL: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft. YS: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all participants and relevant medical staff.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Dagra A Lucke-Wold B McGrath K Mehkri I Mehkri Y Davidson CG et al Central retinal artery occlusion: a review of pathophysiological features and management. Stroke Vasc Interv Neurol. (2024) 4(1):e000977. 10.1161/SVIN.123.000977

2.

Hayreh SS . Central retinal artery occlusion. Indian J Ophthalmol. (2018) 66(12):1684–94. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1446_18

3.

Tiwari V Bagga SSJ Prasad R Mathurkar S . A review of current literature on central retinal artery occlusion: its pathogenesis, clinical management, and treatment. Cureus. (2024) 16(3):e55814. 10.7759/cureus.55814

4.

Mac Grory B Schrag M Biousse V Furie KL Gerhard-Herman M Lavin PJ et al Management of central retinal artery occlusion: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. (2021) 52(6):e282–94. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000366

5.

Chen SN Hwang JF Huang J Wu SL . Retinal arterial occlusion with multiple retinal emboli and carotid artery occlusion disease. Haemodynamic changes and pathways of embolism. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. (2020) 5(1):e000467. 10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000467

6.

Cassola N Baptista-Silva JC Nakano LC Flumignan CD Sesso R Vasconcelos V et al Duplex ultrasound for diagnosing symptomatic carotid stenosis in the extracranial segments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2022) 7(7):CD013172. 10.1002/14651858

7.

Rafailidis V Li X Sidhu PS Partovi S Staub D . Contrast imaging ultrasound for the detection and characterization of carotid vulnerable plaque. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. (2020) 10(4):965. 10.21037/cdt.2020.01.08

8.

Schinkel AF Bosch JG Staub D Adam D Feinstein SB . Contrast-enhanced ultrasound to assess carotid intraplaque neovascularization. Ultrasound Med Biol. (2020) 46(3):466–78. 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.10.020

9.

Golemati S Cokkinos DD . Recent advances in vascular ultrasound imaging technology and their clinical implications. Ultrasonics. (2022) 119:106599. 10.1016/j.ultras.2021.106599

10.

Chen W Ni M Huang H Cong H Fu X Gao W et al Chinese expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of coronary microvascular diseases (2023 edition). MedComm. (2023) 4(6):e438. 10.1002/mco2.438

11.

Huang Z Cheng XQ Liu HY Bi XJ Liu YN Lv WZ et al Relation of carotid plaque features detected with ultrasonography-based radiomics to clinical symptoms. Transl Stroke Res. (2022) 13(6):970–82. 10.1007/s12975-021-00963-9

12.

Zeng P Zhang Q Liang X Zhang M Luo D Chen Z . Progress of ultrasound techniques in the evaluation of carotid vulnerable plaque neovascularization. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2024) 53(4):479–87. 10.1159/000534372

13.

Cao J Zeng Y Zhou Y Yao Z Tan Z Huo G et al The value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in assessing carotid plaque vulnerability and predicting stroke risk. Sci Rep. (2025) 15(1):5850. 10.1038/s41598-025-90319-2

14.

Kelly D Rothwell PM . Disentangling the multiple links between renal dysfunction and cerebrovascular disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2020) 91(1):88–97. 10.1136/jnnp-2019-320526

15.

Servadei F Anemona L Cardellini M Scimeca M Montanaro M Rovella V et al The risk of carotid plaque instability in patients with metabolic syndrome is higher in women with hypertriglyceridemia. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2021) 20(1):98. 10.1186/s12933-021-01277-8

16.

Pan Z Guo H Wang Q Tian S Zhang X Li C et al Relationship between subclasses low-density lipoprotein and carotid plaque. Transl Neurosci. (2022) 13(1):30–7. 10.1515/tnsci-2022-0210

17.

Wang Y Wang T Luo Y Jiao L . Identification markers of carotid vulnerable plaques: an update. Biomolecules. (2022) 12(9):1192. 10.3390/biom12091192

18.

Fabiani I Palombo C Caramella D Nilsson J De Caterina R . Imaging of the vulnerable carotid plaque: role of imaging techniques and a research agenda. Neurology. (2020) 94(21):922–32. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009480

19.

Wang B Chen Y Qiao Q Dong L Xiao C Qi Z . Evaluation of carotid plaque vulnerability with different echoes by shear wave elastography and CEUS. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2023) 32(3):106941. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2022.106941

20.

Heck D Jost A . Carotid stenosis, stroke, and carotid artery revascularization. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. (2021) 65:49–54. 10.1016/j.pcad.2021.03.005

21.

Yan H Wu X He Y Staub D Wen X Luo Y . Carotid intraplaque neovascularization on contrast-enhanced ultrasound correlates with cardiovascular events and poor prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. (2021) 47(2):167–76. 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.10.013

22.

Yang N Wang Q Qi H Song Z Zhou C Zhang S et al TCD-Guided management in carotid endarterectomy: a retrospective study. J Cardiothorac Surg. (2024) 19(1):588. 10.1186/s13019-024-03069-z

23.

Li W Li L Zhuang B-W Ruan S-M Hu H-T Huang Y et al Inter-reader agreement of CEUS LI-RADS among radiologists with different levels of experience. Eur Radiol. (2021) 31(9):6758–67. 10.1007/s00330-021-07777-1

24.

Lioznovs A Radzina M Saule L Grinbergs PE Lacis A . What is the added value of carotid CEUS in the characterization of atherosclerotic plaque?Medicina (Kaunas). (2024) 60(3):375. 10.3390/medicina60030375

Summary

Keywords

central retinal artery occlusion, contrast-enhanced ultrasound, carotid plaques, embolic risk, propensity score matching

Citation

Song Z, Zhou C, Yang N, Huang Z, Li B and Si Y (2026) Contrast-enhanced carotid ultrasound improves vulnerable plaque detection in acute central retinal artery occlusion: a propensity score–matched study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1664769. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1664769

Received

12 July 2025

Accepted

16 October 2025

Published

05 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Emil Marian Arbanasi, George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science, and Technology of Targu Mures, Romania

Reviewed by

Francesca D'Auria, University of Salerno, Italy

Zoltan Bajko, George Emil Palade University of Medicine Pharmacy, Science, and Technology of Targu Mures, Romania

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Song, Zhou, Yang, Huang, Li and Si.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Changjiang Zhou jnsrmyyzcj@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.