Abstract

Background:

β-blockers (BB) are the cornerstone of treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). However, due to potential adverse effects, guidelines recommend starting with a low dose and gradually titrating upwards. Hypertensive patients with HFrEF tend to have better drug responsiveness and prognosis, but it remains unclear whether they can tolerate initial high-dose BB. Therefore, this study aims to assess the tolerance of this population to initial high-dose BB therapy.

Methods:

A retrospective observational study included 307 hypertensive patients with HFrEF who initiated BB therapy and were admitted to the cardiology department at West China Hospital, Sichuan University. Patients’ demographic and clinical information was collected through the electronic medical record (EMR) system. Patients were categorized into a high-dose group if their initial BB dose exceeded 1/8 of the target dose, all other patients were assigned to the standard-dose group. Multivariate logistic forward regression analysis was performed to explore factors influencing the prescriptions of intial high-dose BB and adverse safety outcomes related to BB therapy during hospitalization, including bradycardia, hypotension, acute HF, wheezing requiring bronchodilator therapy, and BB dose reduction or cessation.

Results:

Seventy patients (22.8%) were initially prescribed high-dose BB. Logistic forward regression analysis revealed that only coronary heart disease was negatively associated with the prescriptions of initial high-dose BB, with an odds ratio of 0.435 (95% CI: 0.247–0.763, P = 0.004). Further logistic regression analysis demonstrated no independent association between the initial high-dose BB therapy and the occurrence of adverse safety outcomes, including bradycardia, hypotension, acute HF, wheezing requiring bronchodilator therapy, or BB dose reduction or discontinuation (all p < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Prescriptions of initial high-dose BB in hypertensive patients with HFrEF were not associated with an increased incidence of adverse safety outcomes. These findings indicate that initial high-dose BB therapy could be a viable strategy for this population.

1 Introduction

Heart failure (HF) represents the terminal stage of various cardiovascular diseases and is classified by ejection fraction (EF) into three categories: HF with reduced EF (HFrEF, EF < 40%), HF with mildly reduced EF (HFmrEF, EF 41%–49%), and HF with preserved EF (HFpEF, EF ≥ 50%) (1). Data from the China Hypertension Survey indicate an overall HF prevalence of 0.3% among 22,158 participants, with 40% having HFrEF, 23% with HFmrEF, and 36% with HFpEF (2). HF is associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and reduced quality of life. Among its various subtypes, HFrEF is linked to the poorest prognosis, HFrEF was associated with a nearly two-fold increased risk of 5 year mortality than HFpEF. Patients with HFrEF face a nearly two-fold higher risk of 5-year mortality compared to those with HFpEF (3).

The overactivation of the neuroendocrine system, including the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, is a key pathophysiological mechanism in HFrEF (4). β-blockers (BB), essential neuroendocrine antagonists in the management of HFrEF, have robust evidence supporting their efficacy in improving patient outcomes (5). However, BB are often associated with adverse effects, such as bradycardia, hypotension, and bronchospasm, which may prevent patients from reaching target doses or lead to treatment discontinuation (6). As a result, clinical practice guidelines recommend a “start low, go slow” approach, initiating BB at low doses (no more than 1/8 of the target dose) and gradually titrating upwards (7). Despite this, some clinicians advocate for initial higher-dose BB during hospitalization to avoid delays or failures in uptitration after discharge, as general practitioners may be less familiar with their use in HF management (8, 9).

HF is a complex syndrome with multiple etiologies, leading to varied mechanisms of cardiac structural changes and prognosis (10–12). Accordingly, responses to pharmacological treatments may differ (13). Hypertension is a common cause of HF (1), and hypertension accounting for 39% of HF cases in men and 59% in women (14). Marco Bobbo et al. further observed that patients with hypertensive cardiomyopathy respond rapidly to optimal HF therapy and have a favorable cardiovascular prognosis (15). However, it remains unclear whether hypertensive patients with HFrEF can tolerate initial high-dose BB therapy.

Therefore, in this study, we aim to utilized inpatient data to investigate the association between initial high-dose BB therapy and the occurrence of adverse safety outcomes during hospitalization in hypertensive patients with HFrEF, providing a basis for further exploration of treatment strategies tailored to different HF etiologies.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study population

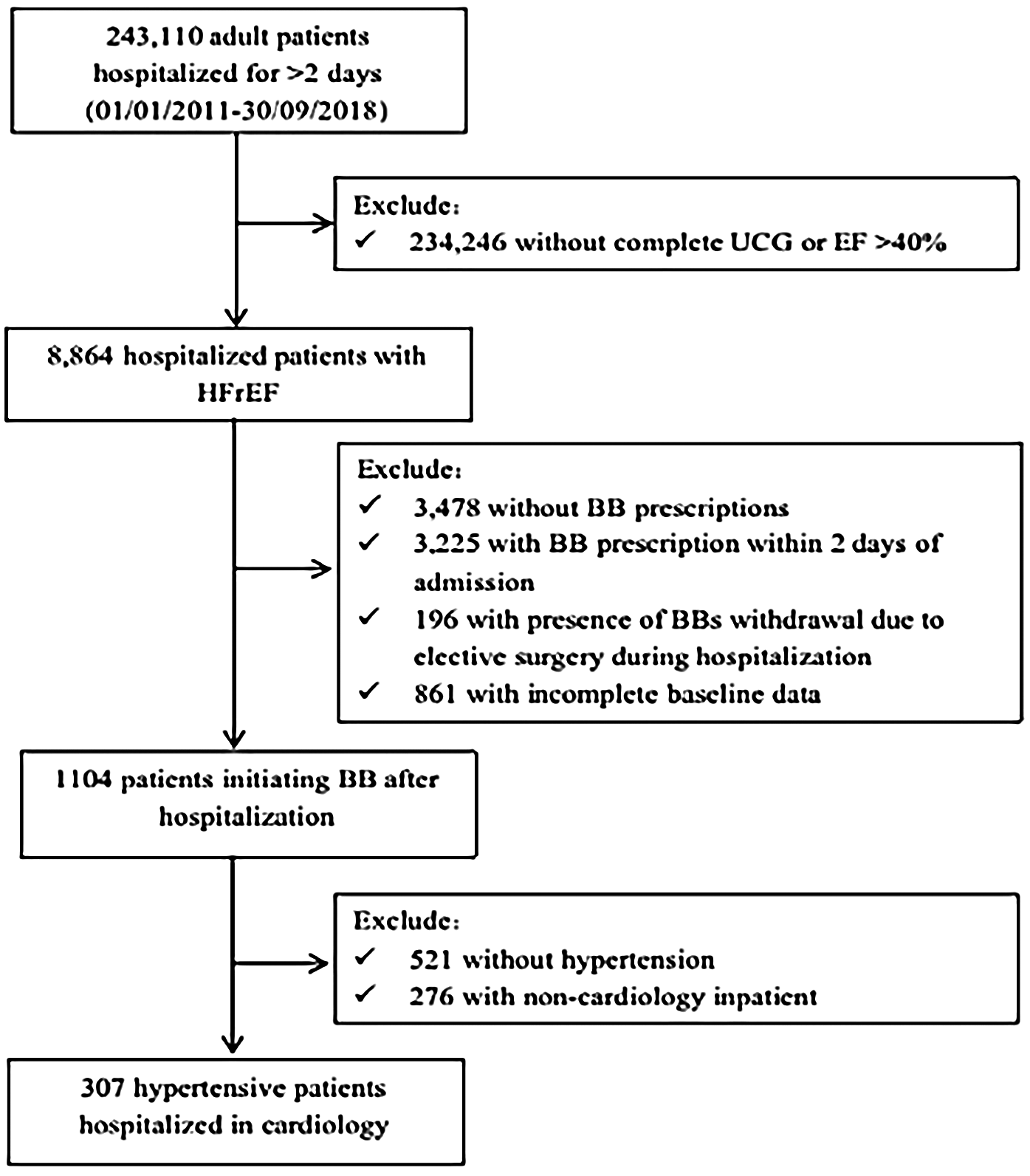

We conducted a retrospective cohort study utilizing electronic medical records (EMRs) to identify hypertensive patients with HFrEF. The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients aged over 18 years who were hospitalized at West China Hospital of Sichuan University between January 1, 2011, and September 30, 2018; echocardiographic evidence of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <40%; a documented history of hypertension at discharge; admission to the cardiology department; and initiation of BB therapy during hospitalization, defined as starting treatment on or after the third day of admission (16). Exclusion criteria included a hospital stay of less than 2 days, incomplete laboratory or vital sign data, or patients who underwent any non-cardiac surgical procedures. A total of 307 hypertensive patients with HFrEF who initiated BB therapy were enrolled in the study (The inclusion and exclusion flowchart is shown in Figure 1). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

Figure 1

Flow chat. UCG, ultrasound cardiac imaging; EF, ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; BB, beta-blockers.

2.2 Data collection

We collected the following data from the inpatient EMR system: demographic information, including age, sex, smoking status, and alcohol consumption; vital signs, including systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate (HR) and respiratory rate; physical measurements, including height and weight; left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) from echocardiographic data; prescription records; laboratory test results; and discharge diagnoses based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10 codes). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). Baseline data were defined using prescription records from the first two calendar days following admission, the earliest recorded vital signs, and the initial laboratory test results. The laboratory test results included fasting blood glucose (FBG), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), white blood cells (WBC), hemoglobin (Hb), N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), cardiac troponin T (cTnT), uric acid, and creatinine. Discharge diagnoses, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary heart disease (CHD), arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy, rheumatic heart disease, and acute myocardial infarction (AMI), were identified using ICD-10 codes I10–I15, E10–E14, I20–I25, I44–I49, I42, I01–I09, and I21–I23, respectively. For patients with multiple hospitalizations, we analyzed data from their first admission.

2.3 Initiating dose of BB

The standardized initiating dose for each patient was determined by dividing the original initiating dose documented in the EMR by the target dose of BB. According to recent guidelines, patients were categorized into a high-dose group if their standardized initiating dose exceeded 1/8 of the target dose, while all other patients were assigned to the standard-dose group (7).

2.4 Adverse safety outcomes

According to the study by Zhou et al. (16), the adverse safety outcomes associated with BB therapy include bradycardia (defined as a HR below 60 beats per min after BB administration), hypotension (characterized by a SBP below 90 mmHg following BB treatment), acute HF (indicated by the administration of morphine or intravenous milrinone post-BB administration), wheezing requiring bronchoconstriction (defined as receiving intravenous methylprednisolone, aminophylline, or doxofylline after BB treatment), dose reduction events (described as a standardized BB dose lower than that of the previous day), and cessation events (defined as the discontinuation of BB therapy during hospitalization).

2.5 Statistical analysis

The study population's characteristics were summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. Differences between the two groups were analyzed using the Chi-square test for categorical variables, independent t-tests for normally distributed variables, and Mann–Whitney or Wilcoxon tests for non-normally distributed variables. Multivariate logistic forward regression analysis was used to explore the factors influencing the prescriptions of initial high-dose BB and adverse safety outcomes related to BB therapy during hospitalization in hypertensive patients with HFrEF. Univariate regression analyses were conducted for each independent variable and the dependent variable, and variables with p-values less than 0.15 and the initial high-dose BB therapy were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. A significant difference was set at a p-value <0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 23.0.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline characteristics in the initial standard-dose and high-dose BB therapy groups

A total of 307 hypertensive patients with HFrEF admitted to the cardiology department were included in the analyses. The baseline characteristics of the patients were presented in Table 1. Seventy patients (22.8%) were prescribed BB at doses higher than the guideline recommendation, of which 48 (68.6%) were male. Compared to the initial standard-dose BB therapy group, patients in the high-dose group were younger, exhibited lower cTnT levels, showed a reduced prevalence of CHD and AMI, and had an increased prevalence of cardiomyopathy and rheumatic heart disease. For adverse safety outcomes during hospitalization, the high-dose BB therapy group exhibited a significantly higher proportion of BB dose reduction or cessation events. However, no significant differences were observed between the two groups with respect to bradycardia, hypotension, new episodes of acute HF, or wheezing requiring bronchodilator therapy. Further comparison of baseline characteristics stratified by gender is presented in Supplement Table 1. Among female patients, there was no significant difference in the incidence of adverse safety outcomes between the initial high-dose group and the low-dose group. In contrast, among male patients, the incidence of dose reduction or discontinuation was higher in the high-dose group than in the low-dose group.

Table 1

| Variables | Standard- dose group |

High-dose group |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 237 (77.2) | 70 (22.8) | |

| Age, years | 67.2 ± 12.1 | 63.9 ± 11.1 | 0 . 045 * |

| Male, n (%) | 159 (67.1) | 48 (68.6) | 0.816 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 130 (54.8) | 38 (54.2) | 0.933 |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | 87 (36.7) | 28 (40) | 0.617 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.4 ± 3.8 | 24.0 ± 3.4 | 0.364 |

| HR, beats/min | 90.0 ± 22.4 | 88.3 ± 25.0 | 0.583 |

| SBP, mmHg | 128 ± 23.3 | 132.4 ± 20.2 | 0.158 |

| DBP, mmHg | 78.8 ± 16.3 | 80.9 ± 18.2 | 0.364 |

| FBG, umol/L | 8.1 ± 3.9 | 8.7 ± 4.7 | 0.272 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.43 ± 0.86 | 1.50 ± 0.91 | 0.55 |

| TC, mmol/L | 3.89 ± 1.08 | 3.77 ± 1.02 | 0.398 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.09 ± 0.35 | 1.12 ± 0.32 | 0.521 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.26 ± 0.89 | 2.11 ± 0.84 | 0.204 |

| Uric Acid | 428.5 ± 146.6 | 439.2 ± 144.2 | 0.59 |

| Creatine | 115.2 ± 74.2 | 109.2 ± 47.5 | 0.527 |

| WBC | 9.2 ± 5.3 | 8.3 ± 3.8 | 0.216 |

| Hb, g/L | 123.0 ± 20.9 | 131.6 ± 16.7 | 0.56 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 7,024.6 ± 6,399.0 | 6,474.4 ± 7,373.7 | 0.542 |

| cTnT, ng/L | 927.9 ± 1,709.00 | 459.9 ± 1,370.6 | 0.041* |

| LVEF (%) | 31.2 ± 5.7 | 32.0 ± 5.0 | 0.255 |

| Antihypertensive drugs | |||

| ACEI, n (%) | 126 (53.1) | 51 (44.2) | 0.570 |

| ARB, n (%) | 88 (37.1) | 35 (50.0) | 0.054 |

| CCB, n (%) | 72 (30.3) | 25 (35.7) | 0.399 |

| Venous furosemide, n (%) | 178 (75.1) | 47 (67.1) | 0.186 |

| Oral furosemide, n (%) | 80 (33.7) | 25 (35.7) | 0.761 |

| Oral thiazide, n (%) | 33 (13.9) | 12 (17.1) | 0.503 |

| Aldosterone receptor antagonist, n (%) | 202 (85.2) | 54 (77.1) | 0.110 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 101 (42.6) | 32 (45.7) | 0.646 |

| CHD, n (%) | 174 (73.4) | 37 (52.8) | 0.001 # |

| AMI, n (%) | 82 (34.5) | 12 (17.1) | 0.005 # |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 23 (9.7) | 12 (18.5) | 0.043 * |

| Rheumatic heart disease, n (%) | 5 (2.1) | 5 (7.1) | 0.037* |

| Arrhythmia, n (%) | 91 (38.3) | 36 (51.4) | 0.052 |

| Adverse safety Outcome during Hospitalization | |||

| Bradycardia, n (%) | 62 (26.2) | 24 (34.3) | 0.183 |

| Hypotension, n (%) | 36 (15.2) | 10 (14.3) | 0.852 |

| Acute HF, n (%) | 26 (11.0) | 10 (14.3) | 0.449 |

| Wheezing needing bronchoconstriction, n (%) | 20 (8.4) | 8 (11.4) | 0.445 |

| Dose reduction or cessation, n (%) | 86 (36.3) | 35 (50.0) | 0.039 * |

Baseline characteristics in the initial standard-dose and high-dose BB therapy groups.

n, number; BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; HR, heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBG, fasting blood glucose; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; WBC, white blood cells; Hb, hemoglobin; NT-proBNP, N terminal pro B type natriuretic peptide; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; LVEF, Left Ventricular Ejection Fractions; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; CCB, calcium channel blockers; BB, β-blockers; HF, heart failure.

A P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

3.2 Logistic regression analysis for influencing factors of initial high-dose BB prescription

Logistic forward regression analysis was used to identify the factors influencing the initial high-dose BB prescription. Variables with p-values less than 0.15 from the univariate regression analysis, including age, CHD, AMI, cardiomyopathy, rheumatic heart disease, arrhythmia, SBP, cTnT, ARB, and aldosterone receptor antagonist, were integrated into the analysis. The results revealed that only CHD was negatively associated with initial high-dose BB prescription, with an OR value of 0.435 (95% CI: 0.247–0.763, P = 0.004). The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

| Independent Variable | Model 1 | p-Value | Model 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.978 (0.957–1.000) | 0.047 | Not include | Not include |

| CHD | 0.406 (0.234–0.704) | 0.001 | 0.435 (0.247–0.763) | 0.004* |

| AMI | 0.391 (0.199–0.769) | 0.007 | Not include | Not include |

| Cardiomyopathy | 2.122 (1.012–4.448) | 0.046 | Not include | Not include |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 3.569 (1.003–12.706) | 0.05 | Not include | Not include |

| Arrhythmia | 1.699 (0.993–2.906) | 0.053 | Not include | Not include |

| SBP | 1.009 (0.997–1.021) | 0.158 | Not include | Not include |

| cTnT | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.051 | Not include | Not include |

| ARB | 0.055 (0.989–2.898) | 0.055 | Not include | Not include |

| Aldosterone Receptor Antagonist | 0.113 (0.301–1.135) | 0.113 | Not include | Not include |

Logistic regression analysis for influencing factors of initial high-dose BB prescription.

CHD, coronary heart disease; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; BB, β-blockers.

Model 1: The variables with a p-value less than 0.15 in the logistic univariate regression analysis was presented in Model 1.

Model 2: Logistic forward regression analysis adjusting for variables with p-values less than 0.15 from univariate analysis, including age, CHD, AMI, cardiomyopathy, rheumatic heart disease, arrhythmia, SBP, cTnT, ARB, aldosterone receptor antagonist.

A P-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

P < 0.05.

3.3 Logistic regression analysis for influencing factors of adverse safety outcomes during hospitalization

Logistic forward regression analysis was employed to identify the factors influencing adverse safety outcomes related to BB during hospitalization, including bradycardia, hypotension, acute HF, wheezing requiring bronchoconstriction, and BB dose reduction or cessation events. The initial high-dose BB therapy and variables with p-values less than 0.15 from the univariate regression analysis were integrated into the multivariate regression analysis. The results revealed the following associations: bradycardia events were positively correlated with arrhythmia (OR = 2.057, 95% CI: 1.196–3.537, P = 0.009), oral furosemide (OR = 1.929, 95% CI: 1.103–3.372, P = 0.021), and intravenous furosemide (OR = 3.817, 95% CI: 1.827–7.971, P < 0.001), while negatively correlated with WBC (OR = 0.911, 95% CI: 0.852–0.974, P = 0.006), as shown in Table 3; hypotension events were positively associated with AMI (OR = 2.563, 95% CI: 1.272–5.161, P = 0.008) and intravenous furosemide (OR = 3.044, 95% CI: 1.025–9.042, P = 0.045), while negatively correlated with SBP (OR = 0.977, 95% CI: 0.961–0.994, P = 0.008), as presented in the Table 4; acute HF events were positively associated with CHD (OR = 4.982, 95% CI: 1.645–15.082, P = 0.004), CCB (OR = 3.346, 95% CI: 1.556–7.196, P = 0.002), and intravenous furosemide (OR = 15.706, 95% CI: 2.080–118.613, P = 0.008), as presented in the Table 5; wheezing events were positively associated with CCB (OR = 2.490, 95% CI: 1.119–5.540, P = 0.025) and venous furosemide (OR = 5.739, 95% CI: 1.328–24.998, P = 0.020), as presented in the Table 6; BB Dose reduction or cessation events were positively correlated only with arrhythmia (OR = 2.321, 95% CI: 1.451–3.713, P < 0.001), as presented in the Table 7. It was worth noting that we have not found an independent correlation between the initial high-dose BB therapy and the occurrence of adverse safety outcomes.

Table 3

| Independent Variable | Model 1 | p-Value | Model 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial high-dose of BB | 1.473 (0.831–2.610) | 0.185 | Not include | Not include |

| Male | 0.607 (0.362–1.020) | 0.059 | Not include | Not include |

| Arrhythmia | 2.124 (1.281–3.521) | 0.003 | 2.057 (1.196–3.537) | 0.009* |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 4.069 (1.119–14.794) | 0.033 | Not include | Not include |

| FBG | 0.924 (0.858–0.996) | 0.038 | Not include | Not include |

| LDL-C | 0.757 (0.553–1.037) | 0.083 | Not include | Not include |

| Uric Acid | 1.001 (1.000–1.003) | 0.117 | Not include | Not include |

| WBC | 0.942 (0.885–1.002) | 0.056 | 0.911 (0.852–0.974) | 0.006* |

| ARB | 1.762 (1.065–2.917) | 0.028 | Not include | Not include |

| Oral furosemide | 1.820 (1.089–3.040) | 0.022 | 1.929 (1.103–3.372) | 0.021* |

| Venous furosemide | 2.859 (1.459–5.601) | 0.002 | 3.817 (1.827–7.971) | <0.001# |

| Oral thiazide | 1.902 (0.986–3.670) | 0.055 | Not include | Not include |

| Aldosterone receptor antagonist | 1.731 (0.825–3.634) | 0.147 | Not include | Not include |

Logistic regression analysis for influencing factors of bradycardia events during hospitalization.

FBG, fasting blood glucose; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; WBC, white blood cells; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; BB, β-blockers.

Model 1: The variables with a p-value less than 0.15 in the logistic univariate regression analysis was presented in Model 1.

Model 2: Logistic forward regression analysis adjusting for Initial high dose of beta-blockers and variables with p-values less than 0.15 from univariate analysis, including male, arrhythmia, rheumatic heart disease, FBG, LDL-C, uric acid, WBC, ARB, oral furosemide, venous furosemide, oral thiazide, aldosterone receptor antagonist.

A P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

Table 4

| Independent Variable | Model 1 | p-Value | Model 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial high-dose of BB | 0.931 (0.436–1.985) | 0.852 | Not include | Not include |

| Alcohol | 1.656 (0.881–3.114) | 0.118 | Not include | Not include |

| CHD | 4.389 (1.676–11.495) | 0.003 | Not include | Not include |

| AMI | 3.690 (1.936–7.034) | <0.001 | 2.563 (1.272–5.161) | 0.008* |

| SBP | 0.979 (0.964–0.993) | 0.004 | 0.977 (0.961–0.994) | 0.007* |

| cTnT | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.009 | Not include | Not include |

| Venous furosemide | 3.432 (1.306–9.014) | 0.012 | 3.044 (1.025–9.042) | 0.045* |

Logistic regression analysis for influencing factors of hypotension events during hospitalization.

CHD, coronary heart disease; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; BB, β-blockers.

Model 1: The variables with a p-value less than 0.15 in the logistic univariate regression analysis was presented in Model 1.

Model 2: Logistic forward regression analysis adjusting for Initial high dose of beta-blockers and variables with p-values less than 0.15 from univariate analysis, including alcohol, CHD, AMI, SBP, cTnT.

A P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

P < 0.05.

Table 5

| Independent Variable | Model 1 | p-Value | Model 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial high-dose of BB | 1.353 (0.618–2.961) | 0.45 | Not include | Not include |

| Male | 0.434 (0.215–0.876) | 0.02 | Not include | Not include |

| Alcohol | 1.794 (0.892–3.608) | 0.101 | Not include | Not include |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2.590 (1.258–5.331) | 0.01 | Not include | Not include |

| CHD | 4.112 (1.411–11.98) | 0.01 | 4.982 (1.645–15.082) | 0.004* |

| Cardiomyopathy | 0.193 (0.026–1.451) | 0.11 | Not include | Not include |

| AMI | 2.566 (1.268–5.193) | 0.009 | Not include | Not include |

| HR | 1.013 (0.999–1.027) | 0.071 | Not include | Not include |

| DBP | 1.017 (0.997–1.038) | 0.089 | Not include | Not include |

| FBG | 1.092 (1.018–1.171) | 0.014 | Not include | Not include |

| WBC | 1.054 (0.994–1.118) | 0.081 | Not include | Not include |

| NT-proBNP | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.011 | Not include | Not include |

| CCB | 2.765 (1.366–5.598) | 0.005 | 3.346 (1.556–7.196) | 0.002* |

| Venous furosemide | 14.921 (2.01–110.773) | 0.008 | 15.706 (2.080–118.613) | 0.008* |

Logistic regression analysis for influencing factors of acute HF events during hospitalization.

CHD, coronary heart disease; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; HR, heart rate; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBG, fasting blood glucose; WBC, white blood cells; NT-proBNP, N terminal pro B type natriuretic peptide; CCB, calcium channel blockers; BB, β-blockers; HF, heart failure.

Model 1: The variables with a p-value less than 0.15 in the logistic univariate regression analysis was presented in Model 1.

Model 2: Logistic forward regression analysis adjusting for Initial high dose of beta-blockers and variables with p-values less than 0.15 from univariate analysis, including male, alcohol, diabetes mellitus, CHD, cardiomyopathy, AMI, HR, DBP, FBG, WBC, NT-proBNP, CCB, venous furosemide.

A P-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

P < 0.05.

Table 6

| Independent Variable | Model 1 | p-Value | Model 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial high-dose of BB | 1.400 (0.588–3.332) | 0.447 | Not include | Not include |

| Alcohol | 2.065 (0.945–4.514) | 0.069 | Not include | Not include |

| HR | 1.013 (0.998–1.029) | 0.084 | Not include | Not include |

| Uric Acid | 0.997 (0.994–1.000) | 0.085 | Not include | Not include |

| Creatine | 1.004 (1.000–1.008) | 0.006 | Not include | Not include |

| WBC | 1.069 (1.005–1.137) | 0.034 | Not include | Not include |

| CCB | 2.361 (1.078–5.172) | 0.032 | 2.490 (1.119–5.540) | 0.025* |

| Venous furosemide | 5.226 (1.212–22.536) | 0.027 | 5.739 (1.318–24.998) | 0.02* |

Logistic regression analysis for influencing factors of wheezing events during hospitalization.

HR, heart rates; WBC, white blood cells; CCB, calcium channel blockers; BB, β-blockers.

Model 1: The variables with a p-value less than 0.15 in the logistic univariate regression analysis was presented in Model 1.

Model 2: Logistic forward regression analysis adjusting for Initial high dose of beta-blockers and variables with p-values less than 0.15 from univariate analysis, including alcohol, HR, uric acid, creatine, WBC, CCB, venous furosemide.

A P-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

P < 0.05.

Table 7

| Independent Variable | Model 1 | p-Value | Model 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial high-dose of BB | 1.756 (1.025–3.007) | 0.04 | Not include | Not include |

| HR | 1.010 (1.000–1.020) | 0.048 | Not include | Not include |

| Creatine | 1.003 (0.999–1.006) | 0.129 | Not include | Not include |

| NT-proBNP | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.07 | Not include | Not include |

| Arrhythmia | 2.321 (1.451–3.713) | <0.001 | 2.321 (1.451–3.713) | <0.001# |

| Aldosterone receptor antagonist | 1.898 (0.978–3.684) | 0.058 | Not include | Not include |

Logistic regression analysis for influencing factors of BB dose reduction or cessation during hospitalization.

HR, heart rate; NT-proBNP, N terminal pro B type natriuretic peptide; BB, β-blockers.

Model 1: The variables with a p-value less than 0.15 in the logistic univariate regression analysis was presented in Model 1.

Model 2: Logistic forward regression analysis adjusting for Initial high dose of beta-blockers and variables with p-values less than 0.15 from univariate analysis, including HR, Creatine, Arrhythmia, NT-proBNP, Aldosterone receptor antagonist.

A P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

P < 0.001.

4 Disscusion

This study found that among hypertensive patients with HFrEF, 22.8% were initially prescribed high-dose BB. Patients with CAD were less likely to be prescribed a high-dose BB. After adjusting for confounding variables, initial high-dose BB therapy was not associated with an increased incidence of adverse safety outcomes, including bradycardia, hypotension, acute HF, bronchoconstriction requiring bronchodilator therap, or BB dose reduction or cessation events.

Contrary to our findings, Zhou et al. reported that among 1,104 HFrEF patients who initiated BB therapy during hospitalization, 27.5% received high-dose BB treatment, which was associated with a higher risk of dose reduction or withdrawal (16). The discrepancies between these findings may be attributed to the varying etiologies of HF. HF is a heterogeneous condition, representing the final stage of numerous cardiac diseases, with hypertension being the most prevalent cause (1). Persistent hypertension leads to left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction through direct hemodynamic overload and indirect neuroendocrine mechanisms (14, 17). Over time, this pathological state, further aggravated by coronary microvascular dysfunction, myocardial fibrosis, and comorbidities such as diabetes and obesity, progresses to dilated cardiomyopathy with HFrEF (18). Compared to ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertensive HF is associated with a better prognosis and a more favorable response to pharmacotherapy (15). Additionally, previous research has indicated that lower pre-treatment BP is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality (19, 20), but it did not perform subgroup analyses based on the etiology of heart failure. The improvement in clinical symptoms following HF treatment is often accompanied by an elevation in BP (21). These findings suggest that in patients with HFrEF, higher baseline BP may reflect better compensatory capacity of myocardial contractility (15). This may partially account for our observation that initial high-doses BB did not elevate the risk of adverse safety outcomes among hypertensive patients with HFrEF.

The REBOOT trial recently suggested that BB use may be harmful in women with MI and HFpEF, particularly at higher doses—a finding not observed in men (22). Unlike REBOOT, our study, while noting more frequent dose reduction or discontinuation in high-dose males, found no independent link between sex and adverse outcomes in multivariate analysis. This difference may arise from distinct patient cohorts: REBOOT reported a significant interaction between sex and BB use in patients with HFpEF, but not in those with HFmrEF, whereas we only included HFrEF, a group with marked neurohormonal activation. Moreover, our analysis was limited to the initial in-hospital BB dose without follow-up data. Further research is needed to clarify sex-based responses to BB dosing across heart failure subtypes.

Additionally, studies indicate that BB therapy can provide mortality and morbidity benefits within 2–3 weeks of initiation (23). Furthermore, in real-world clinical practice, community general practitioners may lack familiarity with the use of BB in HF management, potentially leading to delays or failures in the uptitration of therapy following hospital discharge. Therefore, some clinicians advocate for initial high-doses BB during hospitalization (8, 9). Overall, we hypothesize that initial high-dose BB therapy in hypertensive patients with HFrEF could improve outcomes, though further research is needed to confirm this.

There are several limitations to our study. First, as a retrospective analysis, medication data were collected from the inpatient EMR system, which may miss unrecorded self-administered medications, especially in non-cardiology wards. To reduce this bias, we limited the study to cardiology department patients. Additionally, the study focused solely on hospitalization data without follow-up information, which may not fully capture the compliance and effectiveness of long-term BB use. However, given the challenges of obtaining comprehensive data from real-world outpatient settings and the importance of initiating BB during hospitalization for long-term adherence, our analysis was limited to inpatient BB use. Lastly, the etiology of HF in the included patients may include ischemic or other causes, rather than being solely attributable to hypertension. Further research is needed to validate these findings in patients with HFrEF where hypertension is the sole underlying cause.

5 Conclusion

In conclusin, the initial high-dose BB therapy in hypertensive patients with HFrEF does not increase the risk of adverse safety outcomes, including bradycardia, hypotension, acute HF, bronchoconstriction requiring bronchodilator therapy, or BB dose reduction or cessation events. These findings suggest that a initial high dose BB therapy may be a feasible strategy in this population. Further research is warranted to explore the long-term benefits of initiating high-dose BB therapy.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

XL: Writing – original draft. XY: Writing – original draft. YZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. SW: Writing – review & editing. XC: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant numbers: 2023NSFSC0581, Sichuan, China).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Information Center of West China Hospital, Sichuan University, for their invaluable assistance in data extraction.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1672940/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Savarese G Becher PM Lund LH Seferovic P Rosano GMC Coats AJS . Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res. (2023) 118(17):3272–87. 10.1093/cvr/cvac013

2.

Hu SS . Heart failure in China: epidemiology and current management. J Geriatr Cardiol. (2024) 21(6):631–41. 10.26599/1671-5411.2024.06.008

3.

Chen S Huang Z Liang Y Zhao X Aobuliksimu X Wang B et al Five-year mortality of heart failure with preserved, mildly reduced, and reduced ejection fraction in a 4880 Chinese cohort. ESC Heart Fail. (2022) 9(4):2336–47. 10.1002/ehf2.13921

4.

Narayan SI Terre GV Amin R Shanghavi KV Chandrashekar G Ghouse F et al The pathophysiology and new advancements in the pharmacologic and exercise-based management of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a narrative review. Cureus. (2023) 15(9):e45719. 10.7759/cureus.45719

5.

de Oliveira MT Baptista R Chavez-Leal SA Bonatto Marcely Gimenes . Heart failure management with Β-blockers: can we do better?Curr Med Res Opin. (2024) 40(Suppl 1):43–54. 10.1080/03007995.2024.2318002

6.

Marti H-P Pavía López AA Schwartzmann P . Safety and tolerability of Β-blockers: importance of cardioselectivity. Curr Med Res Opin. (2024) 40(sup1):55–62. 10.1080/03007995.2024.2317433

7.

Ponikowski P Voors AA Anker SD Bueno H Cleland JGF Coats AJS et al 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (Hfa) of the esc. Eur Heart J. (2016) 37(27):2129–200. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128

8.

Hancock HC Close H Fuat A Murphy JJ Hungin APS Mason JM . Barriers to accurate diagnosis and effective management of heart failure have not changed in the past 10 years: a qualitative study and national survey. BMJ Open. (2014) 4(3):e003866. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003866

9.

Smeets M Van Roy S Aertgeerts B Vermandere M Vaes B . Improving care for heart failure patients in primary care, Gps’ perceptions: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Open. (2016) 6(11):e013459. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013459

10.

Youn JC Ahn Y Jung HO . Pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail Clin. (2021) 17(3):327–35. 10.1016/j.hfc.2021.02.001

11.

Spitaleri G Zamora E Cediel G Codina P Santiago-Vacas E Domingo M et al Cause of death in heart failure based on etiology: long-term cohort study of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. J Clin Med. (2022) 11(3):784. 10.3390/jcm11030784

12.

Barkoudah E Yancy CW . Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Med Clin N Am. (2025) 109(6):1157–73. 10.1016/j.mcna.2025.04.010

13.

Silverdal J Bollano E Henrysson J Basic C Fu M Sjöland H . Treatment response in recent-onset heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: non-ischaemic vs. ischaemic aetiology. ESC Heart Fail. (2023) 10(1):542–51. 10.1002/ehf2.14214

14.

Gallo G Savoia C . Hypertension and heart failure: from pathophysiology to treatment. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25(12):6661. 10.3390/ijms25126661

15.

Bobbo M Pinamonti B Merlo M Stolfo D Iorio A Ramani F et al Comparison of patient characteristics and course of hypertensive hypokinetic cardiomyopathy versus idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. (2017) 119(3):483–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.10.014

16.

Zhou Y Zeng Y Wang S Li N Wang M Mordi IR et al Guideline adherence of Β-blocker initiating dose and its consequence in hospitalized patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:770239. 10.3389/fphar.2021.770239

17.

Nwabuo CC Vasan RS . Pathophysiology of hypertensive heart disease: beyond left ventricular hypertrophy. Curr Hypertens Rep. (2020) 22(2):11. 10.1007/s11906-020-1017-9

18.

Di Palo KE Barone NJ . Hypertension and heart failure: prevention, targets, and treatment. Heart Fail Clin. (2020) 16(1):99–106. 10.1016/j.hfc.2019.09.001

19.

Seidu S Lawson CA Kunutsor SK Khunti K Rosano GMC . Blood pressure levels and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. (2024) 26(5):1111–24. 10.1002/ejhf.3108

20.

Fonarow GC Adams KF Abraham WT Yancy CW Boscardin WJ . Risk stratification for in-hospital mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure: classification and regression tree analysis. JAMA. (2005) 293(5):572–80. 10.1001/jama.293.5.572

21.

Ather S Bangalore S Vemuri S Cao LB Bozkurt B Messerli FH . Trials on the effect of cardiac resynchronization on arterial blood pressure in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. (2011) 107(4):561–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.014

22.

Rossello X Dominguez-Rodriguez A Latini R Sanchez PL Raposeiras-Roubin S Anguita M et al Beta-blockers after myocardial infarction: effects according to sex in the reboot trial. Eur Heart J. (2025). 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf673

23.

Williams RE . Early initiation of beta blockade in heart failure: issues and evidence. J Clin Hypertens. (2005) 7(9):520–8; quiz 9–30. 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2005.04273.x

Summary

Keywords

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, hypertension, initial high-dose beta-blockers, toleration, treatment strategy

Citation

Li X, Yang X, Zhou Y, Wang S and Chen X (2025) Initial high-dose β-blockers toleration with reduced ejection fraction heart failure of hospitalized hypertensive patients. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1672940. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1672940

Received

25 July 2025

Revised

09 November 2025

Accepted

27 November 2025

Published

15 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Chun Chin Chang, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taiwan

Reviewed by

Agustín Clemente Moragón, Spanish National Centre for Cardiovascular Research, Spain

Cyndiana Widia Dewi Sinardja, Udayana University, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li, Yang, Zhou, Wang and Chen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Si Wang 27880114@qq.com Xiaoping Chen xiaopingchen22@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.