Abstract

We report the rare case of 16-year-old male monozygotic twins, born to first cousins, who developed acute end-stage heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy, requiring emergency heart transplantations within days of each other. Both twins presented with rapid-onset symptoms and progressed to refractory cardiogenic shock despite inotropic support, necessitating veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Heart transplantation was performed within 3 weeks of admission, and both twins have remained clinically stable 3 years posttransplantation. Family history was negative for cardiomyopathy. Genetic testing identified the following four shared variants: a homozygous FLNC variant (p.Tyr786Asp), two heterozygous SCN5A variants (p.Gln1366His and p.Thr1367Ser), and a heterozygous MYH7 variant (p.Ile1927Phe). All were classified as variants of uncertain significance. Segregation analysis showed that both parents were heterozygous carriers of the FLNC variant; their daughter (the twins' sister) was homozygous for FLNC and carried both SCN5A variants; however, she was asymptomatic. A muscle biopsy from one twin showed pathological features consistent with a diagnosis of myofibrillar myopathy, including fiber disarray and desmin accumulation. In silico analysis suggested structural disruption associated with the MYH7 variant. This case likely represents an unclassified genetic cardiomyopathy with skeletal and cardiac muscle involvement. It underscores the diagnostic complexity of consanguineous pedigrees and the limitations of current variant classification systems. The synchronous disease onset in these monozygotic twins suggests a potential genetic or epigenetic trigger and highlights the value of integrating family studies, histopathology, and computational modeling in the evaluation of inherited cardiomyopathies.

Introduction

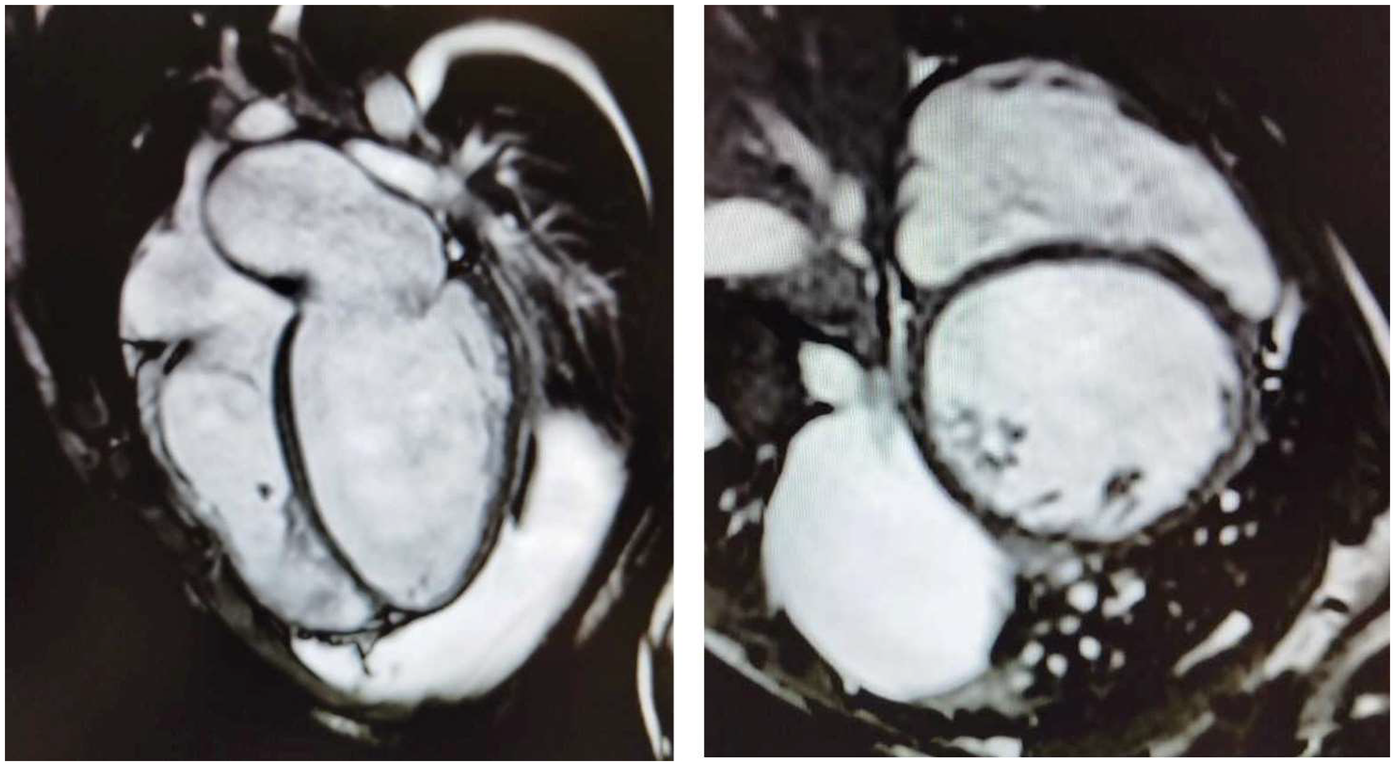

Herein, we describe the cases of two 16-year-old identical male twins who presented with acute end-stage heart failure (HF) requiring emergency heart transplantation (HT), secondary to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). The patients provided informed consent for the publication of their cases. The twins, who are the sons of first cousins, were born at term and were previously in good health, had no past medical history, and no cardiovascular or neuromuscular symptoms. They were diagnosed within 15 days of each other and underwent successful HTs within a week of each other. Twin A had been in good health until he developed a worsening cough and dyspnea. Echocardiography revealed a new diagnosis of DCM with severely reduced systolic function. He was transferred to the coronary care unit (CCU), where intravenous milrinone, furosemide, and norepinephrine were administered. Cardiac MRI confirmed severe biventricular dysfunction with myocardial fibrosis (Figure 1). Myocarditis screening was negative. He was diagnosed with acute HF secondary to idiopathic DCM and listed for an HT (status 2). As his clinical condition worsened to refractory cardiogenic shock, he was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), intubated, and placed on femoro-femoral veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO). Due to progressive left ventricular (LV) distention with pulmonary edema, the patient underwent rescue percutaneous atrial septectomy to obtain LV venting. The patient was listed as status 1 and underwent an HT within 24 days. His postoperative course was complicated by pneumothorax, requiring chest tube insertion. He was discharged on postoperative day 40. He experienced a single episode of acute cellular rejection (grade 2R), which was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone. The patient is thriving 3 years after the HT, with preserved biventricular function and no evidence of cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV).

Figure 1

Four-chamber (left) and short-axis (right) cine images from cardiac magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating severe bi-ventricular dilatation, accompanied by myocardial wall thinning and fibrosis.

Twin B presented 15 days after his brother, with worsening fatigue and tachycardia. He had been in good health until the appearance of symptoms. Echocardiography showed DCM with severely reduced systolic function. He was transferred to the CCU, where milrinone and norepinephrine were initially administered and later replaced by epinephrine due to severe hypotension. He was diagnosed with familial DCM and listed for an HT. Identical to his twin, his condition rapidly deteriorated to refractory cardiogenic shock, necessitating VA-ECMO support with subsequent LV venting via percutaneous atrial septectomy. He underwent HT 17 days after admission, 1 week after his brother. His postoperative course was complicated by a lower airway obstruction that led to a brief episode of cardiac arrest, after which he was successfully resuscitated without neurological sequelae. He also developed bilateral pneumothorax. He was discharged on postoperative day 50. Similar to his identical twin, this patient is thriving 3 years after transplantation, with good biventricular function and no evidence of acute rejection or CAV.

Family members, including the patients’ parents and a 21-year-old sister, were asymptomatic from a cardiovascular and neuromuscular point of view. Physical examinations, ECGs, and echocardiography of their parents and sister were negative. Their sister is currently asymptomatic and continues active surveillance with yearly clinical examinations, ECG, and echocardiography, while reproductive counseling has not yet been planned.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing was performed, and the following four variants in three different genes were identified in both twins:

Homozygous c.2356T > G in the FLNC gene (NM_001458), resulting in p.Tyr786Asp.

Heterozygous c.4098G > T in the SCN5A gene (NM_198056), resulting in p.Gln1366His.

Heterozygous c.4099A > T in the SCN5A gene (NM_198056), resulting in p.Thr1367Ser.

Heterozygous c.5779A > T in the MYH7 gene (NM_000257), resulting in p.Ile1927Phe.

The

SCN5Avariants have not been previously described, and their significance remains undetermined. The

MYH7variant has been linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, but its role in DCM remains unclear. The

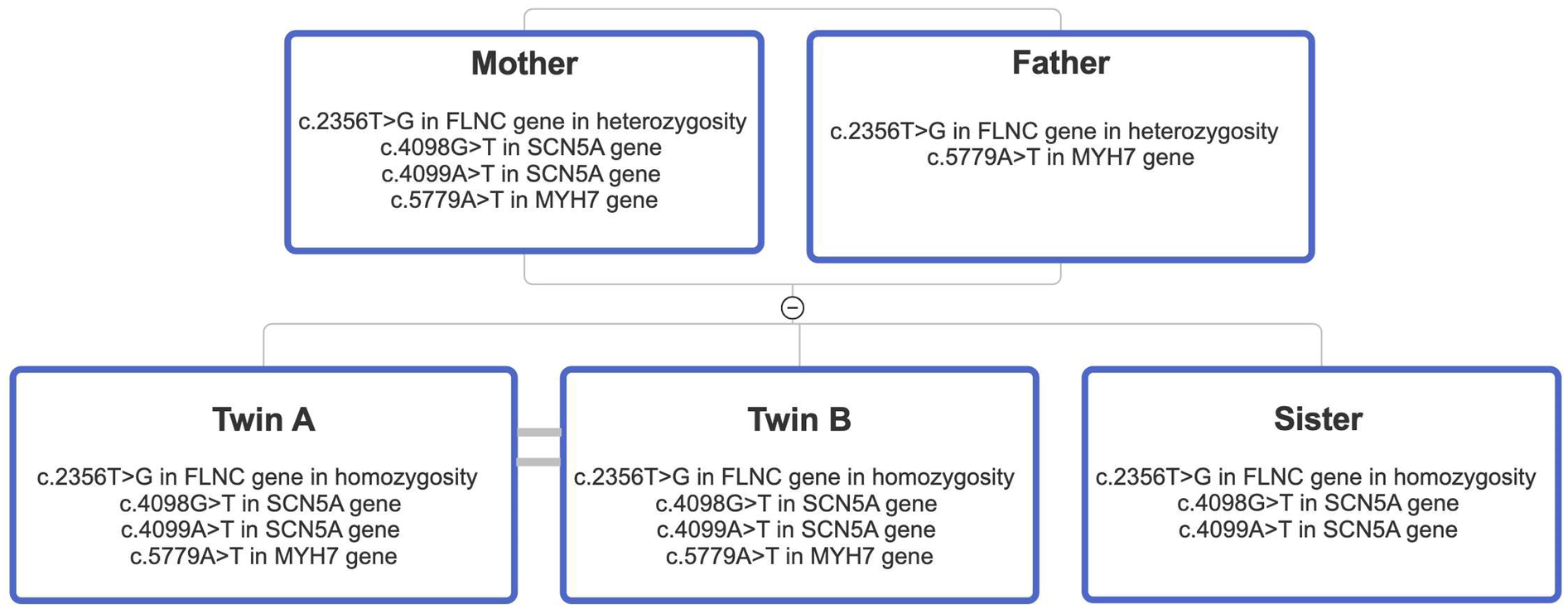

FLNCvariant, absent from control databases, is classified as of uncertain clinical significance according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria. A family segregation study was conducted (

Figure 2). The mother presented with the

FLNCvariant in heterozigosity together with both

SCN5Avariants and the

MYH7one. The father was found to carry the heterozygous

FLNCand

MYH7variants, while the sister was found to be a carrier of the

FLNCvariant in homozygosity, along with both

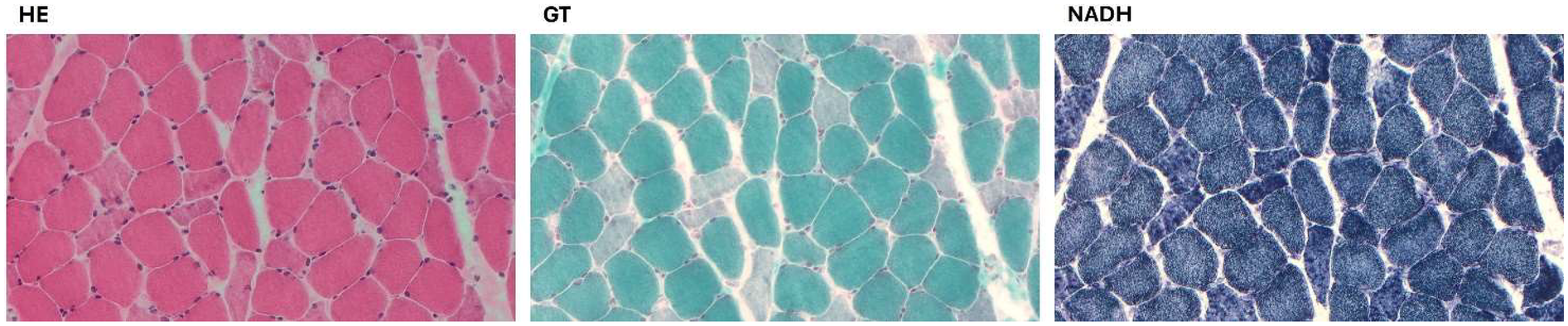

SCN5Avariants. Clinical examinations and echocardiography of the family members revealed no cardiovascular disease. A biopsy of the deltoid muscle was performed on one of the two siblings during the index hospitalization, which showed increased fiber size variation, rimmed vacuoles, loss/reduction of ATPase activity, and an irregular intermyofibrillar network (

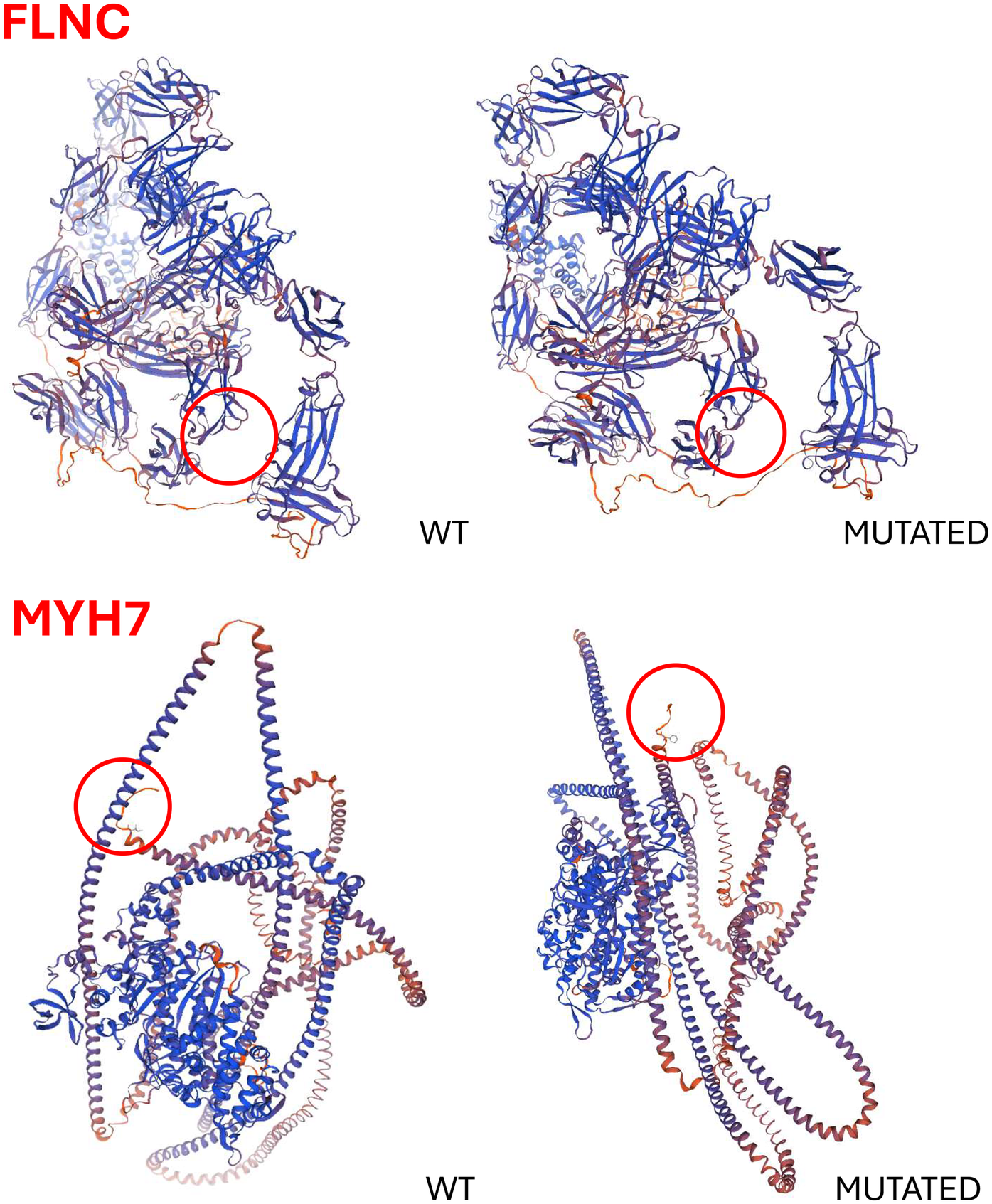

Figure 3). Using immunofluorescence, irregular areas of increased reactivity for desmin, αB-crystallin, and myotilin were observed within the abnormal fibers. The histological and immunohistochemical findings were suggestive of myofibrillar myopathy (MFM). Given the suspicion of a pathogenic role of the

FLNCand

MYH7variants, an

in silicoanalysis was performed, and the wild-type and mutant protein structures were predicted using SWISS-MODEL and AlphaFold. Only the

MYH7gene variant appeared to the associated to an altered three-dimensional structure of the protein (

Figure 4).

Figure 2

Pedigree diagram illustrating the segregation analysis performed in the family of the two probands. Notably, both parents are heterozygous carriers of both the MYH7 and FLNC variants. In contrast, the sister is homozygous for the FLNC variant and wild-type for the MYH7 variant.

Figure 3

A biopsy of the deltoid muscle showing increased fiber size variation, rimmed vacuoles in a few fibers, and several fibers with amorphous eosinophilic material, loss/reduction of ATPase activity, and an irregular intermyofibrillar network. (HE, hematoxylin and eosin; GT, modified Gomori trichrome; NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-tetrazolium reductase).

Figure 4

Predicted three-dimensional structures of the wild-type and mutant FLNC and MYH7 proteins. In silico analyses were performed using SWISS-MODEL and AlphaFold to assess the structural impact of the identified variants. Notably, only the MYH7 variant appears to significantly alter the protein's three-dimensional conformation.

Discussion

DCM is characterized by ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction, often leading to HF requiring an HT (1). Genetic factors play a central role in the pathogenesis of DCM, with mutations in genes encoding cardiac sarcomeric proteins, cytoskeletal components, and other critical proteins. The key genes implicated in inherited forms of DCM include TTN, LMNA, SCN5A, MYH7, and FLNC, among others (2). Variants of uncertain significance (VUSs) are often identified in genetic testing, which complicates diagnosis and clinical management (3). In the case of these twins, we report a previously unreported form of genetic cardiomyopathy, where the identification of VUSs in three genes, namely, MYH7, SCN5A, and FLNC, posed challenges in determining the pathogenic role of these variants. Family segregation studies help clinicians to identify whether a variant segregates with disease, offering an insight into its pathogenicity. However, the utility of segregation studies is limited in consanguineous families. Indeed, close genetic relationships increase the likelihood of shared genetic variants, potentially leading to false-positive associations, in which benign variants appear to cosegregate with disease (4). In this case, the consanguinity of the parents complicated the interpretation of the genetic results. A muscle biopsy played a fundamental role in establishing the final diagnosis of MFM. MFMs are a group of neuromuscular disorders characterized by clinical and genetic heterogeneity (5). The clinical spectrum mainly consists of progressive muscle weakness in the upper and/or lower limbs, which is frequently associated with cardiomyopathy. Causative genes include DES, CRYAB, MYOT, LDB3, FLNC, MYH7, and BAG3, which encode for Z-disk or Z-disk-associated proteins, and the disease is usually transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait (6–8). In silico analyses can predict the impact of genetic variants on the three-dimensional structure and interactions of proteins (9). In our study, these analyses identified a potentially pathogenic role for the MYH7 gene variant. Regardless of the molecular aspects of the disease, the exact cause of the abrupt and simultaneous presentation of congestive HF in these identical twins remains elusive. Whether a silent timer of disease onset is concealed in this previously unknown genetic variant or whether psychological/social factors may have elicited the abrupt appearance of cardiogenic shock is presently unclear. At present, we have to assume that this dramatic and timed presentation may be inscribed in the rare genetic mutations associated with this disease.

This clinical case also underscores the fact that genetic diagnosis in cardiomyopathy does not end with variant identification, but also extends to family counseling and follow-up. Integrating genetic testing, clinical surveillance, and reproductive counseling for all relatives, whether symptomatic or not, represents the best medical practice (10) and is an ethical responsibility.

Conclusion

Since a clear diagnosis of a previously reported genetic cardiomyopathy has not yet been reached in this familial case, we believe this to be a newly identified genetic cardiomyopathy. It is important to note that monozygotic twins offer a unique opportunity to investigate the genetic basis of complex diseases such as DCM. The identification of variants of uncertain significance, the complexity of family segregation studies in consanguineous families, and the complementary role of muscle biopsies in confirming the diagnosis are all important aspects of this case. Genetic testing, alongside clinical evaluation and muscle biopsy, plays a crucial role in improving the accuracy of the diagnosis, while also pointing to the need for further research into the functional role of specific mutations.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

This study involving humans was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata di Verona. This study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

GL: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Visualization, Conceptualization, Project administration, Validation. CP: Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Validation. AG: Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. VM: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation. MC: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Validation. RM: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation. LS: Writing – original draft, Validation, Visualization. PT: Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. GV: Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. SH: Validation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. AF: Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. GM: Validation, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Visualization. AG: Data curation, Visualization, Validation, Writing – original draft. LG: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation. GF: Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Validation. FO: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation. ED: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Visualization, Investigation, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Bando Ricerca Finalizzata, grant# RF-2019-12370413 to EDP) and by “Ricerca Corrente” funding from the Italian Ministry of Health to IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CAV, cardiac allograft vasculopathy; CCU, Coronary Care Unit; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; FLNC, filamin 5; HF, heart failure; HT, heart transplantation; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; LMNA, lamin A; LV, left ventricle; MFM, myofibrillar myopathy; MYH7, myosin heavy chain 7; SCN5A, sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 5; TTN, titin; VA-ECMO, veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

References

1.

Seferović PM Polovina M Rosano G Bozkurt B Metra M Heymans S et al State-of-the-art document on optimal contemporary management of cardiomyopathies. Eur J Heart Fail. (2023) 25:174–89. 10.1002/ejhf.2979

2.

Rosenbaum AN Agre KE Pereira NL . Genetics of dilated cardiomyopathy: practical implications for heart failure management. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2020) 17:286–97. 10.1038/s41569-019-0284-0

3.

Richards S Aziz N Bale S Bick D Das S Gastier-Foster J et al Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants. Genet Med. (2015) 17:405–24. 10.1038/gim.2015.30

4.

Bennett RL Motulsky AG Bittles A Hudgins L Uhrich S Doyle DL et al Genetic counseling and screening of consanguineous couples and their offspring: recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. (2002) 11:97–119. 10.1023/A:1014593404915

5.

Schroder R Schoser B . Myofibrillar myopathies: a clinical and myopathological guide. Brain Pathol. (2009) 19:483–92. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00289.x

6.

Fichna JP Maruszak A Zekanowski C . Myofibrillar myopathy in the genomic context. J Appl Genet. (2018) 59:431–9. 10.1007/s13353-018-0463-4

7.

de Frutos F Ochoa JP Navarro-Peñalver M Baas A Bjerre JV Zorio E et al Natural history of MYH7-related dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2022) 80:1447–61. 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.07.023

8.

Kley RA Leber Y Schrank B Zhuge H Orfanos Z Kostan J et al FLNC-associated myofibrillar myopathy: new clinical, functional, and proteomic data. Neurol Genet. (2021) 7:e590. 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000590

9.

Cannon S Williams M Gunning AC Wright CF Ellard S . Evaluation of in silico pathogenicity prediction tools for the classification of small in-frame indels. BMC Med Genomics. (2023) 16:36. 10.1186/s12920-023-01454-6

10.

Hershberger RE Givertz MM Ho CY Judge DP Kantor PF McBride KL et al Genetic evaluation of cardiomyopathy: a clinical practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. (2018) 20:899–909. 10.1038/s41436-018-0039-z

Summary

Keywords

heart transplantation (HT), heart failure, cardiomyopathy, genetic testing, myofibrillar myopathy

Citation

Luciani GB, Panico C, Galeone A, Medeghini V, Ciuffreda M, Mineri R, San Biagio L, Tonin P, Vattemi GN, Hoxha S, Francica A, Mazzeo G, Gambaro A, Gottin L, Faggian G, Onorati F and Di Pasquale E (2025) Case Report: Simultaneous presentation of end-stage heart failure with cardiogenic shock requiring emergency transplantation in monozygotic twins with myofibrillar myopathy: a previously unknown genetic disease?. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1673907. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1673907

Received

12 August 2025

Revised

06 November 2025

Accepted

07 November 2025

Published

02 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Martin Koestenberger, Medical University of Graz, Austria

Reviewed by

Elisabeth Seidl-Mlczoch, Medical University of Vienna, Austria

Ralf Geiger, Medical University Innsbruck, Austria

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Luciani, Panico, Galeone, Medeghini, Ciuffreda, Mineri, San Biagio, Tonin, Vattemi, Hoxha, Francica, Mazzeo, Gambaro, Gottin, Faggian, Onorati and Di Pasquale.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Cristina Panico cristina.panico@hunimed.eu Antonella Galeone antonella.galeone@univr.it

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.