Abstract

Background:

Handgrip strength (HGS) is a marker of frailty that is associated with major adverse cardiovascular outcomes. The relationship between HGS and outcomes in a cardiovascular intensive care unit (CVICU) setting has not been previously studied.

Methods:

We measured handgrip strength upon admission to the CVICU among 330 consecutive adult patients. Subsequent clinical outcomes of interest included readmission to the CVICU, CVICU and hospital length of stay (LOS), 30-day hospital readmission, and in-hospital mortality. Mean values were compared using the student t-test and Pearson's r was used to test bivariate correlation.

Results:

330 patients underwent HGS assessment. HGS was significantly inversely correlated with hospital LOS (r = −0.165, P = 0.003) and mean LOS was 3 days longer among the lowest quartile (HGS <18 kg; P = 0.049). HGS was not associated with either CVICU or 30-day readmission and mortality. Among non-procedural admissions to the CVICU, linear regression identified HGS, age, and albumin as significant predictors of hospital LOS (r = 0.38; P < 0.001). Following an elective procedure, the Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score (OASIS) score (r = 0.426, P < 0.001) and albumin (r = −0.380, p < 0.001) were better predictors of LOS than HGS.

Conclusions:

Hand grip strength provides a simple point of care assessment in the CVICU for determination of patient frailty. Lower values are independently associated with hospital length of stay among non-procedural patients.

Introduction

The modern cardiovascular intensive care unit (CVICU) has evolved from providing rapid resuscitation to a place where comprehensive critical care is provided (1). Advancing age and severe multisystem comorbid illness commonly co-exist alongside cardiovascular disease serving to increase the complexity of patients treated in the CVICU (2). In addition, advances in treating valvular heart disease, cardiac arrhythmias and the utilization of increasingly complex mechanical circulatory support systems have fundamentally changed the case mix in the contemporary CVICU (3).

Intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalization can have a negative impact on an individual's quality of life up to 5 years after hospital discharge (4). Functional and psychological limitations appear to persist with associated increases in cost and utilization of health care services (5). Intensive care unit acquired weakness (ICUAW), defined as a clinically detectable weakness that is attributable to the critical illness itself (6), appears to play a key role in this long-term disability syndrome. ICUAW appears to be remarkably common with an incidence of 40% (7) and is associated with higher morbidity, mortality and longer length of stay (8). Identification of patients at risk for ICUAW and its accompanying adverse outcomes is critical to deploy the necessary therapeutic strategies in a timely fashion.

Among various indices of frailty, bedside assessment of hand-grip strength (HGS) is an accurate and reliable (4) correlate of global muscle strength that predicts length of stay as well as mortality in critically ill medically treated ICU patients (9). Numerous epidemiological studies have shown that lower hand grip strength is associated with increased risk of functional limitations and disability, increased long term mortality, higher activities of daily living dependence, cause specific and total mortality, cardiovascular mortality and respiratory mortality (10). Low HGS is a marker of the frailty phenotype (11) which is predictive of risk of falls, immobility, hospitalizations, and death in a community-dwelling cohort aged >65 years. HGS has been studied as a marker of old age disability (12) and nutritional status. Low HGS has also been associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction and stroke (13). No study to date has examined HGS in the CVICU patient population, and the relationship between baseline HGS and outcomes following admission to the CVICU is not known. We aimed to describe normal distribution of HGS in a cardiovascular intensive care unit, compare HGS to established validated clinical frailty scales and describe the relationship between HGS and ICU length of stay (LOS), mortality and readmission.

Methods

Study design

This prospective cohort study was conducted in consecutive patients over a 6 month period from December 2018 to May 2019 who were admitted at our institution's CVICU. The study was approved by the institutional review board and all patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients over the age of 18 years admitted to CVICU who were able to participate in HGS assessment were included in the study. We excluded patients who had history of dementia, experienced delirium in the past 24 h, were not able to speak and/or understand English, not oriented to time, place and person and who declined consent to participate. Subjects who were sedated and unable to cooperate with HGS testing (mechanically ventilated, paralyzed, or delirious) underwent HGS assessment on the first day of their CVICU stay in which they could cooperate. Eligible subjects included patients admitted for acute medical conditions and those admitted following elective cardiovascular (nonsurgical) procedures.

Assessment of hand grip strength and clinical variables

Patients admitted to the CVICU underwent HGS testing using a Lafayette hand dynamometer (Figure 1; Lafayette, IN) on the first day of their CVICU stay using a standardized protocol. Subjects were asked to perform a maximal isometric contraction with each hand three consecutive times with each contraction followed by a 5 s rest period. Both peak grip strength and averages measured in pounds for each hand were taken. For each patient we collected baseline demographic, clinical and laboratory data, calculated Charlson comorbidity index and assessed severity of illness using Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score (OASIS).

Figure 1

Lafayette hand dynamometer. (Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette IN).

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was overall hospital length of stay. Secondary endpoints included CVICU LOS, mortality, and readmission to either the CVICU or hospital at 30 days.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 29 (IBM, Inc). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as number and percentages of the total group number. Group comparisons were made using the χ2 or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. For variables that do not follow a Gaussian distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. A stratified subgroup analysis was performed to assess variables affecting hospital length of stay. We also performed a stratified analysis of grip strength in quartiles. A two-sided P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. For multivariate analyses, linear and logistic regression was used to determine if hand grip strength was an independent predictor of continuous and categorical outcomes including variables of univariate significance (P < 0.20).

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of our study population are listed in Table 1. The mean age was 69 ± 15 years and 37.7% were female. Most common reasons for admission to the CVICU were congestive heart failure (33.3%), acute coronary syndrome (30.9%) and after a scheduled procedure (29.1%). Common comorbidities included congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Mean albumin level was 2.93 gm/dl and mean lactic acid level was 2.29 mmol/L. Most patients were right hand dominant (85.5%). Peak grip strength was 26 ± 11 kg. Mean CVICU length of stay was 3.8 ± 4.4 days and mean hospital length of stay was 10.5 ± 10.5 days.

Table 1

| Characteristic | N = 330 (N, %) |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) – years | 68.6 (14.8) |

| Body mass index | 29.4 (7.4) |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 125 (37.7) |

| Race (%) | |

| African American | 161 (48.8) |

| Caucasian | 141 (42.7) |

| Comorbidities (%) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 173 (52.4) |

| Myocardial infarction | 94 (28.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 101 (30.6) |

| Diabetes | 112 (34) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 101 (30.6) |

| Malignancy (active or past) | 49 (14.8) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 243 (73.6) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 37 (11.2) |

| Chronic lung disease | 41 (12.4) |

| Tobacco use | 178 (53.9) |

| Reason for admission (%) | |

| Congestive Heart failure | 110 (33.3) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 102 (30.9) |

| Scheduled procedure | 96 (29.1) |

| Cardiac arrest | 16 (14.8) |

| NYHA functional class (%) | |

| I | 87 (26.6) |

| II | 106 (32.1) |

| III | 97 (29.4) |

| IV | 40 (12.1) |

| Mean lactic acid (SD) – mmol/L | 2.29 (2.31) |

| Mean albumin level (SD) – gm/dl | 2.93 (0.59) |

| Vasopressor use (%) | 84 (25.5) |

| Inotrope use (%) | 77 (23.3) |

| Mechanical circulatory support | |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 41 (12.4) |

| Impella | 3 (0.9) |

| Mechanical respiratory support | |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 57 (17.3) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 53 (16.1) |

| Right hand dominance | 282 (85.5) |

| Grip strength (SD) – kg | |

| Peak | 26.23 (11.09) |

Baseline characteristics.

Peak hand grip strength and outcomes

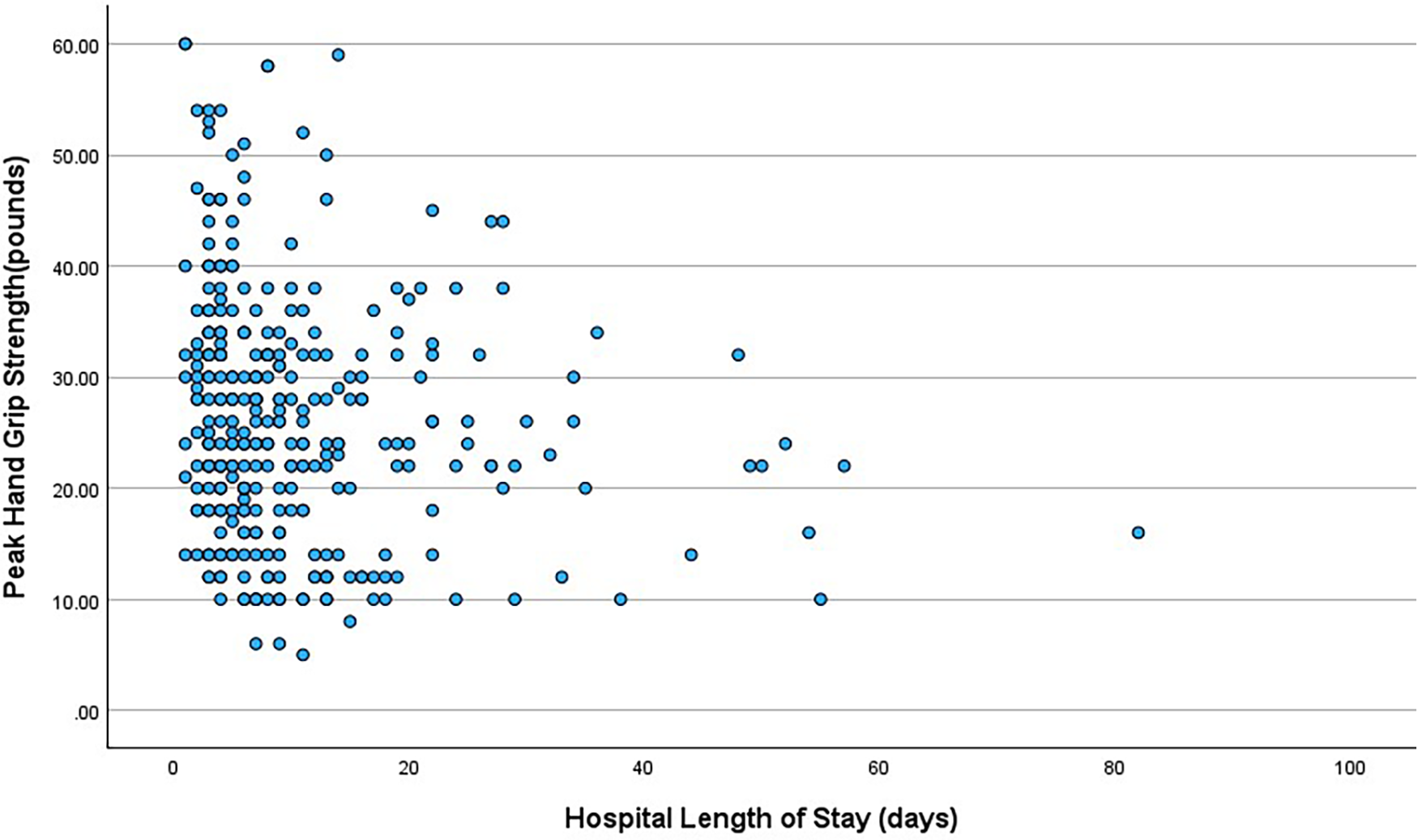

HGS was significantly inversely correlated with hospital LOS (r = −0.165, P = 0.003) (Figure 2) but not with CVICU length of stay (r = −0.053, P = 0.34). Similar correlation coefficients were observed for subgroups of female and male subjects, although statistically significant only in male subjects due to larger sample size. HGS was only related to hospital LOS in patients with non-procedural CVICU admissions (r = −0.222, P < 0.001). There was no relationship among patients with procedural admissions (r = −0.012, P = 0.91). Median hospital length of stay was longer among the lowest quartile of HGS (8.5 days; Interquartile range 5–13) compared to the upper quartiles (7 days; Interquartile range 4–12) which was statistically significant (P = 0.019) (Table 2). HGS was not associated with either CVICU or 30-day readmission and mortality. Among non-procedural admissions to the CVICU, linear regression identified HGS, age and albumin as strongest predictors of hospital LOS (r = 0.38, P < 0.001). Following an elective procedure, the OASIS score (r = 0.426, P < 0.001) and albumin (r = −0.380, P < 0.001) were better predictors of LOS than HGS (Table 3). In multivariate linear regression, HGS remained a predictor of the primary study endpoint of hospital LOS in non-procedural CVICU admissions.

Figure 2

Bivariate correlation between peak hand grip strength and hospital length of stay.

Table 2

| Outcome | Lowest HGS quartile | HGS quartiles 2–4 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| CVICU mortality | 5 (5.7) | 8 (3.3) | 0.33 |

| Total in-hospital mortality | 7 (8) | 13 (5.4) | 0.38 |

| CVICU readmission | 4 (4.5) | 16 (6.6) | 0.50 |

| 30-day readmission | 18 (20.5) | 40 (16.6) | 0.42 |

| Median CVICU length of stay in days (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 2 (1–4) | 0.36 |

| Median hospital length of stay in days (IQR) | 7 (4–12) | 8.5 (5–13) | 0.019 |

Outcomes.

CVICU, cardiovascular intensive care unit; HGS, hand grip strength; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Group comparisons were made using the χ2 or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. For variables that do not follow a Gaussian distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was used.

Table 3

| Baseline characteristics | Nonprocedural admissions | Patients admitted after scheduled procedure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson correlation | P value | Pearson correlation | P value | |

| Peak grip strength | −0.222 | 0.01 | −0.012 | 0.91 |

| Age | −0.125 | 0.56 | −0.207 | 0.04 |

| Body mass index | 0.003 | 0.960 | 0.000 | 1.0 |

| Serum albumin | −0.299 | <0.001 | −0.380 | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity points | 0.003 | 0.968 | −0.084 | 0.42 |

| OASIS score | 0.205 | 0.02 | −0.426 | <0.001 |

Predictors of hospital length of stay for CVICU patients.

Discussion

HGS is a validated and safe assessment tool of global muscle function that is included in several frailty scoring systems (11, 14–17) and its feasibility has been demonstrated in multiple studies to date (9, 11, 15–19). HGS correlates well with elbow flexion, knee extension and trunk extension (20, 21) and this allows for assessment of muscle function without placing critically ill, deconditioned patients with poor exertional tolerance at risk of injury from physical exertion (16). Low grip strength is a consistent predictor of death and high grip strength is a consistent predictor of survival in studies with a diverse sample of subjects (22). To our knowledge, this is the first study of assessment of handgrip strength in the CVICU population.

Predicting which patients have risk for long length of stay holds relevance for both patients and to health care organization to maximize resource allocation, develop an effective service plan and improve outcomes. Our study showed an inverse association between HGS and hospital overall hospital LOS. Many other studies have also shown an association of lower hand grip strength with increased likelihood of complications or increased length of stay (22). In a different population of elder medical inpatients, higher admission HGS was associated with increased likelihood of discharge home (23). Potential contributors to the relationship between HGS and LOS include the known meaningful relationship between HGS and both general functional and nutritional status.

In contrast to various population studies that have associated HGS with mortality, we found that hand grip strength was not associated with CVICU or in-hospital mortality. Our findings match those of a study of 167 elderly patients undergoing coronary artery surgery in which frail patients identified using Cardiovascular Health Study frailty index criteria had a longer median length of stay but similar perioperative outcomes (24). It should be noted that in addition to grip strength, Cardiovascular Health study criteria also use weight loss, exhaustion, physical activity and gait speed as markers of frailty. In another study of 110 patients in a surgical ICU setting, manual muscle testing rather than grip strength measurements predicted mortality and length of stay (25) suggesting that global muscle weakness rather than HGS predicts mortality in intensive care unit. Further study of this relationship is warranted to exclude small relationships through larger sample size, and in populations enriched with higher mortality rates.

Because patients admitted emergently to the CVICU with heart failure, arrythmias and cardiac arrest represent a different cohort of population compared to patients admitted for monitoring after an interventional or electrophysiology procedure, we studied predictors of length of stay in both these cohorts. We found that handgrip strength predicted hospital length of stay better in patients admitted for an acute cardiovascular illness compared to those admitted for monitoring in the CVICU after a scheduled procedure. In patients admitted for monitoring after a procedure, OASIS score was a better predictor of hospital length of stay than hand grip strength. Serum albumin, however, was a predictor of length of stay in both groups of patients. A similar relationship of albumin with length of stay was also noted in a study of HGS in a surgical intensive care unit (25). Serum albumin has also been noted to be an independent prognostic tool for predicting mortality and morbidity in surgical patients.

Study limitations

We found a low event rate experienced by our study sample, consistent with modern CVICU cohorts. It remains possible that in a much larger sample of patients, peak grip strength may be related to mortality as has been seen in many population studies. We used hand grip strength as a single objective measure based upon its simple and accessible nature vs. other markers of frailty. We did not measure hand grip strength before admission and did not conduct longitudinal follow up measurements. Patients requiring significant doses of sedatives and those who have delirium as part of their clinical condition underwent grip strength assessment when deemed suitable by treating physician which may cause heterogeneity in the study. The timing of when to perform grip strength assessments related to sedation or interventions such as mechanical ventilation should be noted as a consideration in clinical translation. We only studied CVICU population of a single tertiary care hospital and this may not be generalizable to other intensive care settings. Finally, use of the highest grip strength value obtained for each patient may have resulted in measurement bias.

Conclusions

HGS has the potential to be used as a simple, inexpensive, and widely applicable point of care assessment similar to an additional “vital sign” that is understood to objectively quantifies frailty in the critically ill CVICU patient. In this study, we identify the clinical correlates of that relationship, namely that lower values of HGS were independently associated with hospital length of stay among non-procedural patients. Prompt recognition of the frailty phenotype will potentially allow for early and targeted mobilization of often limited resources such as physical and occupational therapy to the most relevant patients in need of interventions that could ultimately reduce ICU length of stay as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with ICUAW.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by MedStar Georgetown Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

BB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. NG: Data curation, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PN: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. EC: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AAT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CA: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AJT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

CVICU, cardiovascular intensive care unit; HGS, hand-grip strength; LOS, length of stay; OASIS, Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score.

References

1.

Morrow DA Fang JC Fintel DJ Granger CB Katz JN Kushner FG et al Evolution of critical care cardiology: transformation of the cardiovascular intensive care unit and the emerging need for new medical staffing and training models: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2012) 126:1408–28. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826890b0

2.

Quinn T Weston C Birkhead J Walker L Norris R Group MS . Redefining the coronary care unit: an observational study of patients admitted to hospital in England and Wales in 2003. QJM. (2005) 98:797–802. 10.1093/qjmed/hci123

3.

Katz JN Turer AT Becker RC . Cardiology and the critical care crisis: a perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2007) 49:1279–82. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.11.036

4.

Hermans G Clerckx B Vanhullebusch T Segers J Vanpee G Robbeets C et al Interobserver agreement of medical research council sum-score and handgrip strength in the intensive care unit. Muscle Nerve. (2012) 45:18–25. 10.1002/mus.22219

5.

Herridge MS Tansey CM Matte A Tomlinson G Diaz-Granados N Cooper A et al Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. (2011) 364:1293–304. 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802

6.

Stevens RD Marshall SA Cornblath DR Hoke A Needham DM deJonghe B et al A framework for diagnosing and classifying intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Crit Care Med. (2009) 37:S299–308. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6ef67

7.

Appleton RT Kinsella J Quasim T . The incidence of intensive care unit-acquired weakness syndromes: a systematic review. J Intensive Care Soc. (2015) 16:126–36. 10.1177/1751143714563016

8.

Hermans G Van Mechelen H Clerckx B Vanhullebusch T Mesotten D Wilmer A et al Acute outcomes and 1-year mortality of intensive care unit-acquired weakness. A cohort study and propensity-matched analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2014) 190:410–20. 10.1164/rccm.201312-2257OC

9.

Ali NA O'Brien JM Jr Hoffmann SP Phillips G Garland A Finley JC et al Acquired weakness, handgrip strength, and mortality in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2008) 178:261–8. 10.1164/rccm.200712-1829OC

10.

Norman K Stobaus N Gonzalez MC Schulzke JD Pirlich M . Hand grip strength: outcome predictor and marker of nutritional status. Clin Nutr. (2011) 30:135–42. 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.09.010

11.

Fried LP Tangen CM Walston J Newman AB Hirsch C Gottdiener J et al Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2001) 56:M146–56. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146

12.

Rantanen T Guralnik JM Foley D Masaki K Leveille S Curb JD et al Midlife hand grip strength as a predictor of old age disability. JAMA. (1999) 281:558–60. 10.1001/jama.281.6.558

13.

Leong DP Teo KK Rangarajan S Lopez-Jaramillo P Avezum A Jr Orlandini A et al Prognostic value of grip strength: findings from the prospective urban rural epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet. (2015) 386:266–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62000-6

14.

Chang YT Wu HL Guo HR Cheng Y Tseng C Wang M et al Handgrip strength is an independent predictor of renal outcomes in patients with chronic kidney diseases. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2011) 26:3588–95. 10.1093/ndt/gfr013

15.

Izawa KP Watanabe S Osada N Kasahara Y Yokoyama H Hiraki K et al Handgrip strength as a predictor of prognosis in Japanese patients with congestive heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. (2009) 16:21–7. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32831269a3

16.

Rantanen T Volpato S Ferrucci L Heikkinen E Fried LP Guralnik JM . Handgrip strength and cause-specific and total mortality in older disabled women: exploring the mechanism. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2003) 51:636–41. 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00207.x

17.

Sasaki H Kasagi F Yamada M Fujita S . Grip strength predicts cause-specific mortality in middle-aged and elderly persons. Am J Med. (2007) 120:337–42. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.04.018

18.

Chung CJ Wu C Jones M Kato TS Dam TT Givens RC et al Reduced handgrip strength as a marker of frailty predicts clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure undergoing ventricular assist device placement. J Card Fail. (2014) 20:310–5. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.02.008

19.

Purser JL Kuchibhatla MN Fillenbaum GG Harding T Peterson ED Alexander KP . Identifying frailty in hospitalized older adults with significant coronary artery disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2006) 54:1674–81. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00914.x

20.

Massy-Westropp NM Gill TK Taylor AW Bohannon RW Hill CL . Hand grip strength: age and gender stratified normative data in a population-based study. BMC Res Notes. (2011) 4:127. 10.1186/1756-0500-4-127

21.

Trampisch US Franke J Jedamzik N Hinrichs T Platen P . Optimal jamar dynamometer handle position to assess maximal isometric hand grip strength in epidemiological studies. J Hand Surg Am. (2012) 37:2368–73. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.08.014

22.

Bohannon RW . Hand-grip dynamometry predicts future outcomes in aging adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther. (2008) 31:3–10. 10.1519/00139143-200831010-00002

23.

Kerr A Syddall HE Cooper C Turner GF Briggs RS Sayer AA . Does admission grip strength predict length of stay in hospitalised older patients?Age Ageing. (2006) 35:82–4. 10.1093/ageing/afj010

24.

Ad N Holmes SD Halpin L Shuman DJ Miller CE Lamont D . The effects of frailty in patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery. J Card Surg. (2016) 31:187–94. 10.1111/jocs.12699

25.

Lee JJ Waak K Grosse-Sundrup M Xue F Lee J Chipman D et al Global muscle strength but not grip strength predicts mortality and length of stay in a general population in a surgical intensive care unit. Phys Ther. (2012) 92:1546–55. 10.2522/ptj.20110403

Summary

Keywords

hand grip strength, cardiovascular intensive care, frailty, outcome study, length of stay

Citation

Basyal B, Jarrett H, Gupta N, Nelson P, Czulada E, Taylor AA, Adams CE and Taylor AJ (2026) A prospective study of hand grip strength and cardiovascular outcomes in a cardiovascular intensive care unit. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1677500. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1677500

Received

31 July 2025

Accepted

27 October 2025

Published

05 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Sascha Treskatsch, Charité University Medicine Berlin, Germany

Reviewed by

Marc Rohner, University of Bonn, Germany

Stefan Kreyer, University of Bonn, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Basyal, Jarrett, Gupta, Nelson, Czulada, Taylor, Adams and Taylor.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Allen J. Taylor Allen.taylor@medstar.net

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.