Abstract

Background:

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) can coexist with potential for serious complications. Trends involving both conditions remain unexplored and this study aims to explore them.

Methods:

Nationwide mortality records were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC-WONDER) database from 1999 to 2023 among U.S. adults >45 years with AF (ICD-10 code: I48) and RHD (I05-I09). Age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) were calculated per 100,000 population and stratified by demographic variables. Joinpoint regression analysis was used to determine the average and annual percent change (AAPC and APC).

Results:

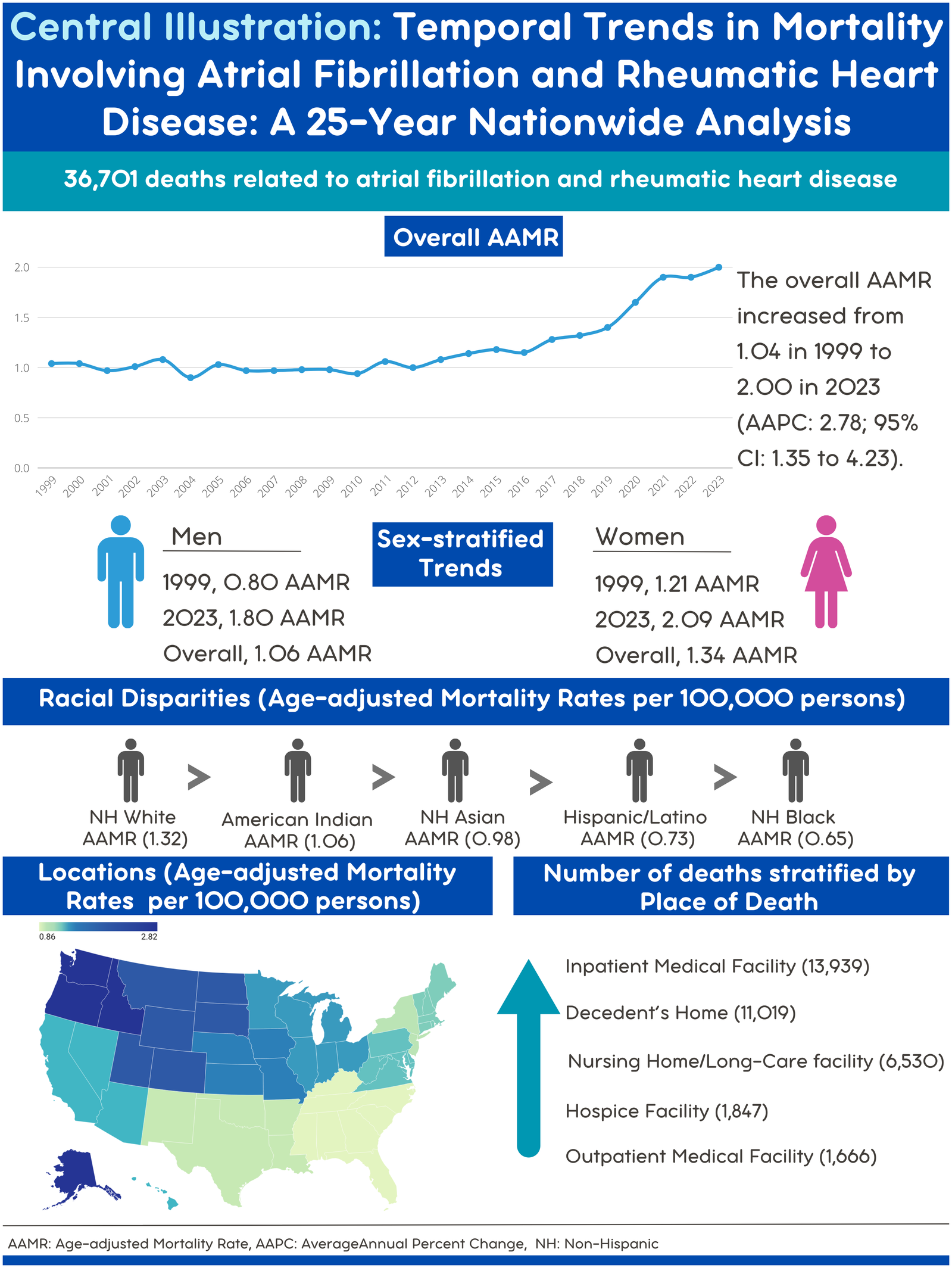

From 1999 to 2023, a total of 36,701 deaths were reported among individuals aged >45 years with AF and RHD in the U.S. The AAMR increased from 1.04 in 1999 to 2.00 in 2023 (AAPC: 2.78; p = 0.001). Women had higher overall AAMR (1.34) (AAPC: 2.48; p < 0.001) than men (1.06) (AAPC: 4.14; p < 0.001). Racially, the highest overall AAMR was in Non-Hispanic (NH) White (1.32) while the overall AAMR in Hispanics was (0.73). Regionally, the highest overall AAMR was noticed in the West (1.68), followed by the Midwest (1.36). The majority of deaths occurred in inpatient medical facilities (13,939 deaths, 38%). Rural areas had higher overall AAMR (1.2) compared to urban areas (1.1).

Conclusion:

Trends in AF and RHD mortality increased lately. Higher trends observed in women, rural areas, the West region, NH white population and inpatient medical facilities.

1 Introduction

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), a worldwide health issue, is viewed to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality (1, 2). RHD develops as a complication of acute rheumatic fever that occurs after a throat infection due to group A beta-hemolytic streptococci infection. In individuals with genetic predisposition, an autoimmune reaction occurs against connective tissues and organs, particularly the heart, causing permanent valve injury and cardiac failure (2, 3). Globally, it affects more than 40.5 million individuals, resulting in more than 300,000 deaths annually, and is considered a significant public health issue. In 2015, the worldwide prevalence of RHD was approximately 34 million cases, with around 320,000 deaths related to RHD (2, 4). A study regarding demographics and mortality trends of valvular heart diseases (VHDs) in older adults in the US demonstrated that there was an increase in age adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) for rheumatic VHDs (APC: 5.01 [95% CI: 2.01–6.92]) from 2017 to 2019 regarding previous years (5).

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a highly prevalent cardiac problem characterized by cardiac dysrhythmia and lack of coordinated contractions, enhancing blood coagulation, clot formation, and embolic stroke (6). AF affects millions worldwide and increases the risk of stroke by fivefold, considered the most frequently diagnosed dysrhythmia in clinical practice (7). Several risk factors increase the risk of AF, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, age, valvular heart disease, and cardiomyopathy (8). Historically, RHD was recognized as an important etiological contributor to AF, particularly in younger populations and in regions with high RHD prevalence (9, 10). AF is expected to affect 6–12 million individuals in the USA by 2050 and 17.9 million in Europe by 2060. AF utilizes significant health resources globally, considering it a public health challenge with increased mortality risk (9).

Patients with RHD, particularly mitral stenosis, have an increased risk of developing AF. A study regarding the prevalence and predictors of atrial fibrillation in rheumatic valvular heart disease demonstrates that chronic AF is detected in 29% of 250 patients with pure mitral stenosis (10). Regarding this association, AF and RHD can coexist with the potential for serious complications, demonstrating that the onset of AF in RHD patients is a clinical marker of bad outcomes and is associated with greater morbidity and mortality as compared with the non-rheumatic population (11, 12). Although AF and RHD frequently coexist with significant morbidity and mortality, few studies have examined long-term temporal trends describing how the association between AF and RHD has evolved over recent decades.

This study aims to analyze the temporal trends in atrial fibrillation associated with rheumatic heart disease over a period of 25 years. This study obtained data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC-WONDER) database from 1999 to 2023 to evaluate temporal trends in mortality of AF associated with RHD among US adults aged over 45 years. Ultimately, this analysis seeks to provide an essential tool for identifying high-risk populations to reduce AF associated RHD related death.

2 Methods

2.1 Study setting and population

In this population-based retrospective mortality trend analysis, we conducted an analysis using death certificate data retrieved from the CDC WONDER database and analyzed data for adults aged 45 and older between 1999 and 2023 to examine mortality trends pertaining AF associated with RHD. Diagnostic coding was employed using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems-10th Revision (ICD-10) as follows: I48 for AF and I05–I09 for RHD. These ICD codes have been previously used to identify Atrial Fibrillation and RHD in administrative databases (13–15). We utilized the Multiple Cause of Death database to identify deaths in which both AF and RHD were listed as either underlying or contributing causes. This approach captures deaths where AF and RHD coexisted, reflecting their combined mortality burden, rather than implying causality between the two conditions. Adults were defined as those who were 45 years or older at the time of death. Similar age cutoff has been used by previous studies to define older adults (16, 17). This age threshold was selected based on the reliability and completeness of data within the CDC WONDER database. Preliminary explorations indicated substantial suppression of mortality data among individuals under 45 years due to small cell counts, which could lead to unstable rate estimates. Therefore, focusing on adults aged ≥45 years allowed for consistent trend evaluation and demographic comparisons. Institutional review board approval was not required for this study as it used de-identified public use data provided by the government and adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting (18).

2.2 Data abstraction

Data for population size, year and demographics such as Sex, Age, Race, region and states was extracted. Place of Death was categorized into Medical Facilities, Hospice, Home and Nursing Home/Long-Term care facilities. Racial and ethnic categories were classified as non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, NH American Indian or Alaskan Native, and NH Asian or Pacific Islander. The National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme was used to assess the population by urban (large metropolitan area [population ≥1 million], medium/small metropolitan area [population 50,000–999,999]) and rural (population <50,000) counties per the 2013 U.S. census classification (19). Regions were stratified into Northeast, Midwest, South, and West according to the U.S. Census Bureau definitions (20).

2.3 Statistical analysis

Crude and age adjusted mortality rates (CMRs and AAMRs) per 100,000 population from 1999 to 2023 by year, sex, race/ethnicity, state, and urban-rural status with 95% CIs were calculated, using the 2000 U.S. population as the standard (21). Crude mortality rates were determined by dividing the number of AF and RHD related deaths by the corresponding U.S. population of that year. To quantify national annual trends in Atrial Fibrillation and RHD-related mortality, the Joinpoint Regression Program (Joinpoint V 5.4.0.0, National Cancer Institute) was used to determine the annual percent change (APC) with 95% CI in AAMR (22). This method allows identification of significant changes in AAMR over time by fitting log-linear regression models where temporal variation occurred. APCs were considered increasing or decreasing if the slope describing the change in mortality was significantly different from zero using two tailed t testing. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This analysis is descriptive and ecological in nature; no individual-level covariate adjustment or causal inference was performed.

3 Results

A total of 36,701 deaths occurred among individuals aged >45 years with AF and RHD between 1999 and 2023 in the United States. The highest number of deaths was recorded in inpatient medical facilities (13,939), followed by the decedent's home (11,019), nursing homes (6,530), hospice (1,847), and outpatient medical facilities (1,666) (Figure 1) (Supplementary Tables 1, 2).

Figure 1

Central illustration. Map created with Datawrapper.

3.1 Overall trends

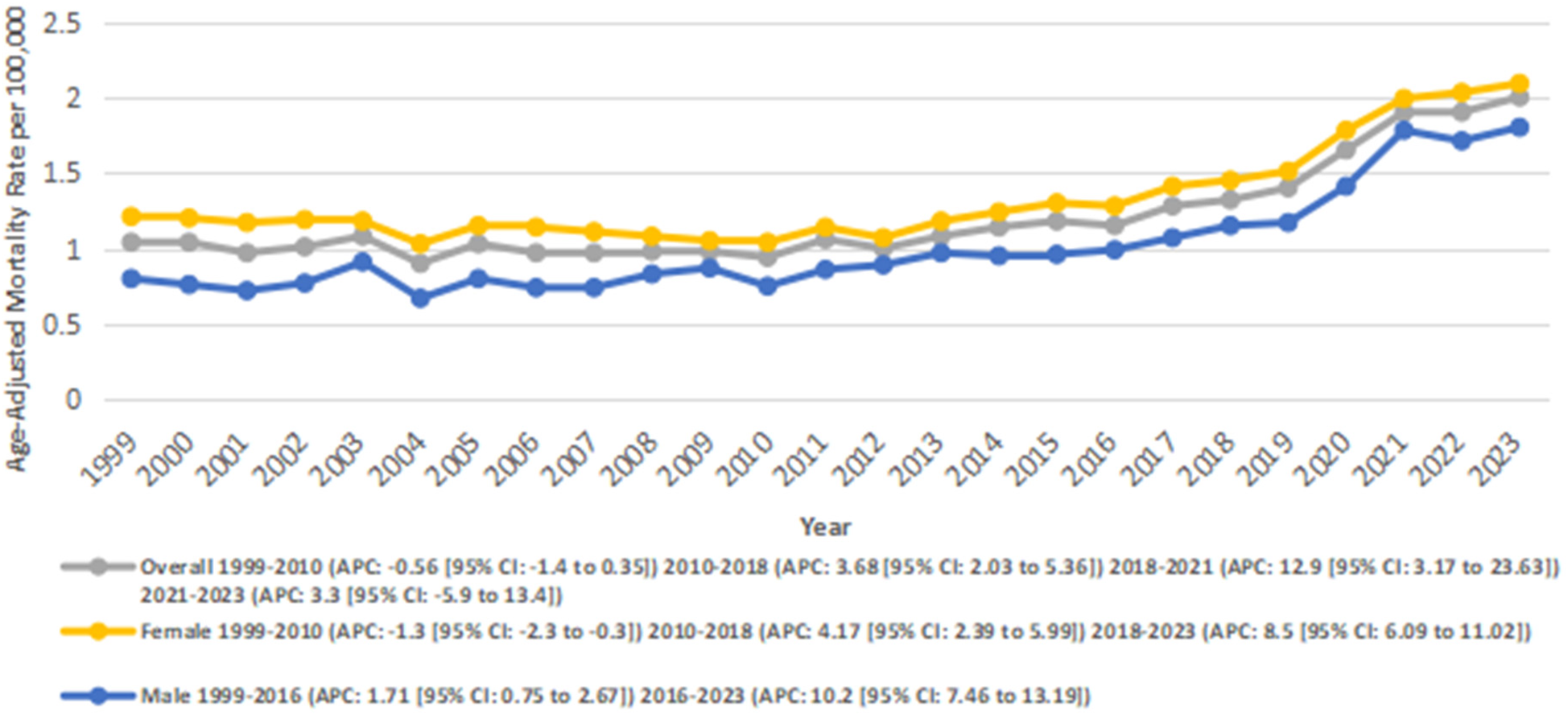

The AAMR for AF- and RHD-related mortality in adults increased significantly from 1.04 in 1999 to 2.00 in 2023, with an AAPC of 2.78* (95% CI: 1.35–4.23; p = 0.001). A decrease in AAMR was observed from 1.04 in 1999 to 0.94 in 2010 (APC: −0.56; 95% CI: −1.47 to 0.36; p = 0.21), followed by a significant rise between 2010 and 2018 as the AAMR increased from 0.94 to 1.32 (APC: 3.69*; 95% CI: 2.04–5.37; p = 0.002), and from 1.32 to 1.9 between 2018 and 2021(APC: 12.95*; 95% CI: 3.18–23.64; p = 0.012). This was followed by a nonsignificant increase in AAMRs from 1.9 in 2021 to 2.00 in 2023 (APC: 3.31; 95% CI: −5.90 to 13.43; p = 0.47) (Figure 2) (Supplementary Tables 1, 3, 4).

Figure 2

Overall and Sex-stratified atrial fibrillation and rheumatic heart disease-related AAMRs per 100,000 in adults in the United States 1999–2023.

3.2 Sex-stratified trends

Women had a higher overall number of deaths as compared to men (24274 vs. 12427). Women also experienced an overall higher AAMR compared to men (1.32 vs. 1.00).

In males, the AAMR increased significantly overall from 0.8 in 1999 to 1.8 in 2023 (AAPC: 4.14*; 95% CI: 3.16–5.14; p < 0.001). A significant increase in AAMR was observed from 0.8 to 0.99 between 1999 and 2016 (APC: 1.71*; 95% CI: 0.75–2.68; p = 0.0013), and from 0.99 in 2016 to 1.8 in 2023 (APC: 10.30*; 95% CI: 7.47–13.20; p < 0.001).

Similarly, in females, the AAMR increased significantly from 1.21 in 1999 to 2.09 in 2023 (AAPC: 2.48*; 95% CI: 1.65–3.33; p < 0.001). A slight decrease in AAMRs was observed from 1.21 to 1.04 between 1999 and 2010 (APC: −1.33; 95% CI: −2.35 to −0.31; p = 0.014), followed by a significant increase from 1.04 in 2010 to 1.45 in 2018 (APC: 4.18; 95% CI: 2.39–6.0; p = 0.001)., and from 1.45 to 2.09 between 2018 and 2023 (APC: 8.53*; 95% CI: 6.09–11.03; p = 0.001) (Figure 2) (Supplementary Tables 1, 3, 4).

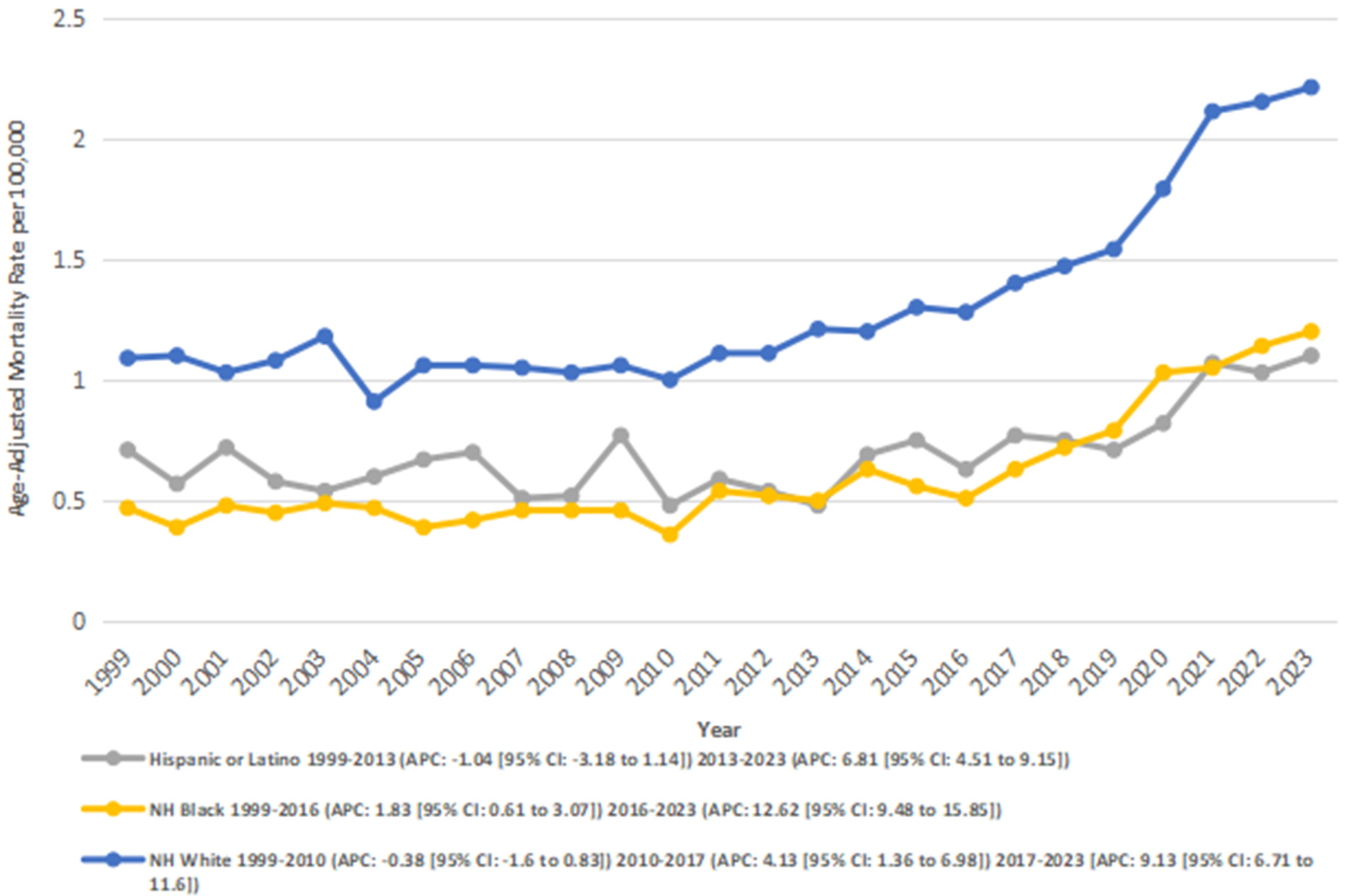

3.3 Stratified by race

When stratified by race, the highest number of deaths was recorded for the NH White population (32,055), followed by the NH Black population (1,754), and Hispanics (1,594). NH Whites also had the highest overall AAMR (1.30), followed by the Hispanics (0.69), and NH Blacks (0.60).

Among the Hispanic or Latino population, mortality rates declined significantly from 0.71 in 1999 to 0.48 in 2013 (APC: −1.05*; 95% CI: −3.18 to 1.14; p = 0.33). From 2013 to 2023, mortality rates increased significantly from 0.48 to 1.1 (APC: 6.81*; 95% CI: 4.51–9.16; p = 0.000004). Overall, from 1999 to 2023, AAMR increased significantly from 0.71 to 1.1 (AAPC: 2.15*; 95% CI: 0.67–3.67; p = 0.004).

Among NH Black or African American individuals, mortality rates increased significantly from 0.47 in 1999 to 0.51 in 2016 (APC: 1.84*; 95% CI: 0.61–3.07; p = 0.005), and from 0.51 in 2016 to 1.2 in 2023 (APC: 12.63*; 95% CI: 9.48–15.86; p < 0.001). Overall, the AAMR increased significantly from 0.47 in 1999 to 1.2 in 2023 (AAPC: 4.87*; 95% CI: 3.71–6.05; p < 0.001).

In the NH White population, a nonsignificant decline was observed from 1.09 in 1999 to 1.00 in 2010 (APC: −0.39; 95% CI: −1.6 to 0.84; p = 0.51), followed by a significant increase from 1.00 in 2010 to 1.4 in 2017 (APC: 4.14*; 95% CI: 1.36–7.00; p = 0.005), and from 1.4 in 2017 to 2.21 in 2023 (APC: 9.13*; 95% CI: 6.71–11.60; p < 0.001) Overall, the AAMR increased significantly from 1.09 in 1999 to 2.21 in 2023 (AAPC: 3.24*; 95% CI: −2.17 to 4.32; p < 0.001) (Figure 3) (Supplementary Tables 1, 3, 5).

Figure 3

Atrial fibrillation and rheumatic heart disease-related AAMRs per 100,000 stratified by race in adults in the United States 1999–2023.

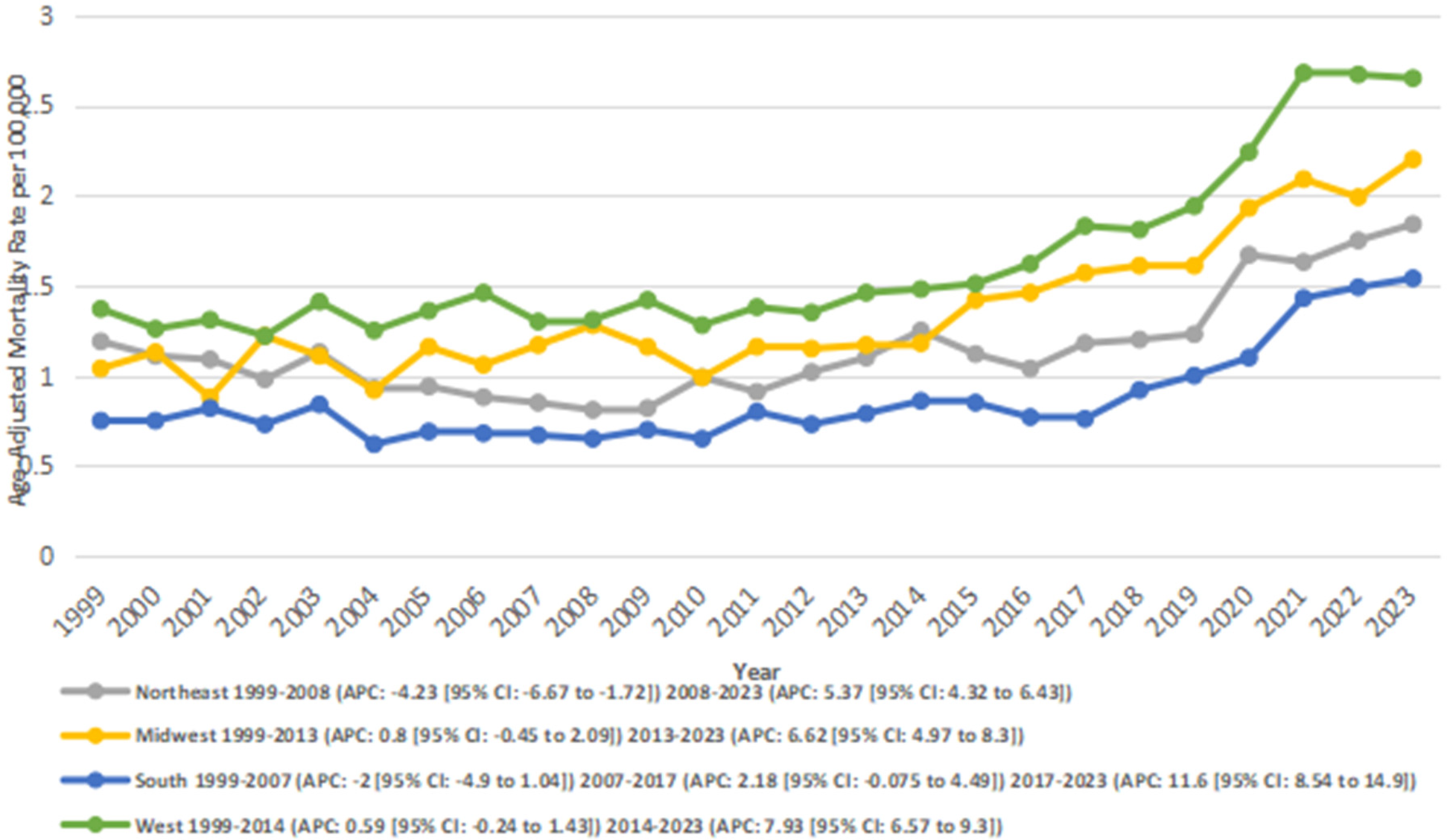

3.4 Stratified by census region

AAMRs were analyzed by the U.S. Census Region to evaluate geographic variation. Differences in AAMRs and the number of deaths were observed across the four regions. The West had the highest overall AAMR (overall AAMR: 8.13; number of deaths: 118,777), followed by the Midwest (overall AAMR: 1.35; number of deaths: 9315), the Northeast (overall AAMR: 1.15; number of deaths: 7,018), and the South (overall AAMR: 0.86; number of deaths: 9,647).

In the Northeast, from 1999 to 2008, there was a significant decrease in AAMRs from 1.19 to 0.81 (APC: −4.23*; 95% CI: −6.67 to −1.72; p = 0.002). This was followed by a period of significant increase from 0.81 in 2008 to 1.84 in 2023 (APC: 5.37*; 95% CI: 4.32–6.43; p < 0.00001). Overall, the AAMRs increased significantly from 1.19 to 1.84 between 1999 and 2023 (AAPC: 1.66*; 95% CI: 0.57–2.77; p = 0.002).

In the Midwest, the AAMRs increased significantly from 1.04 in 1999 to 2.2 in 2023 (AAPC: 3.20*; 95% CI: 2.25–4.15; p < 0.001). Between 1999 and 2013, there was a nonsignificant annual increase in AAMR from 1.04 to 1.17 (APC: 0.81; 95% CI: −0.45 to 2.10; p = 0.20). This was followed by a significant rise in AAMR from 1.17 in 2013 to 2.2 in 2023 (APC: 6.63*; 95% CI: 4.98–8.30; p < 0.001).

In the South, AF- and RHD-related mortality rates decreased nonsignificantly from 0.75 in 1999 to 0.67 in 2007 (APC: −2.01; 95% CI: −4.97 to 1.04; p = 0.18). This was followed by a nonsignificant increase from 0.67 in 2007 to 0.76 in 2017 (APC: 2.19; 95% CI: −0.075 to 4.50; p = 0.06), and a significant increase from 0.76 to 1.54 between 2017 and 2023 (APC: 11,69*; 95% CI: 8.54–14.93; p < 0.001). Overall, between 1999 and 2023, the AAMRs increased significantly from 0.75 to 1.54 (AAPC: 3.03*; 95% CI: 1.55–4.54; p = 0.005).

Similarly, in the West region, an overall significant increase in AAMR was observed from 1.37 in 1999 to 2.65 in 2023 (AAPC: 3.28; 95% CI: 2.60–3.97; p < 0.001). In segments, AAMRs were observed to increase nonsignificantly from 1.37 in 1999 to 1.48 in 2014 (APC: 0.59; 95% CI: −0.24 to 1.44; p = 0.16), and this was followed by a significant increase from 1.48 in 2014 to 2.65 in 2023 (APC: 7.93*; 95% CI: 6.57–9.31; p < 0.001) (Figure 4) (Supplementary Tables 3, 6).

Figure 4

Atrial fibrillation and rheumatic heart disease-related AAMRs per 100,000 stratified by census region in adults in the United States 1999–2023.

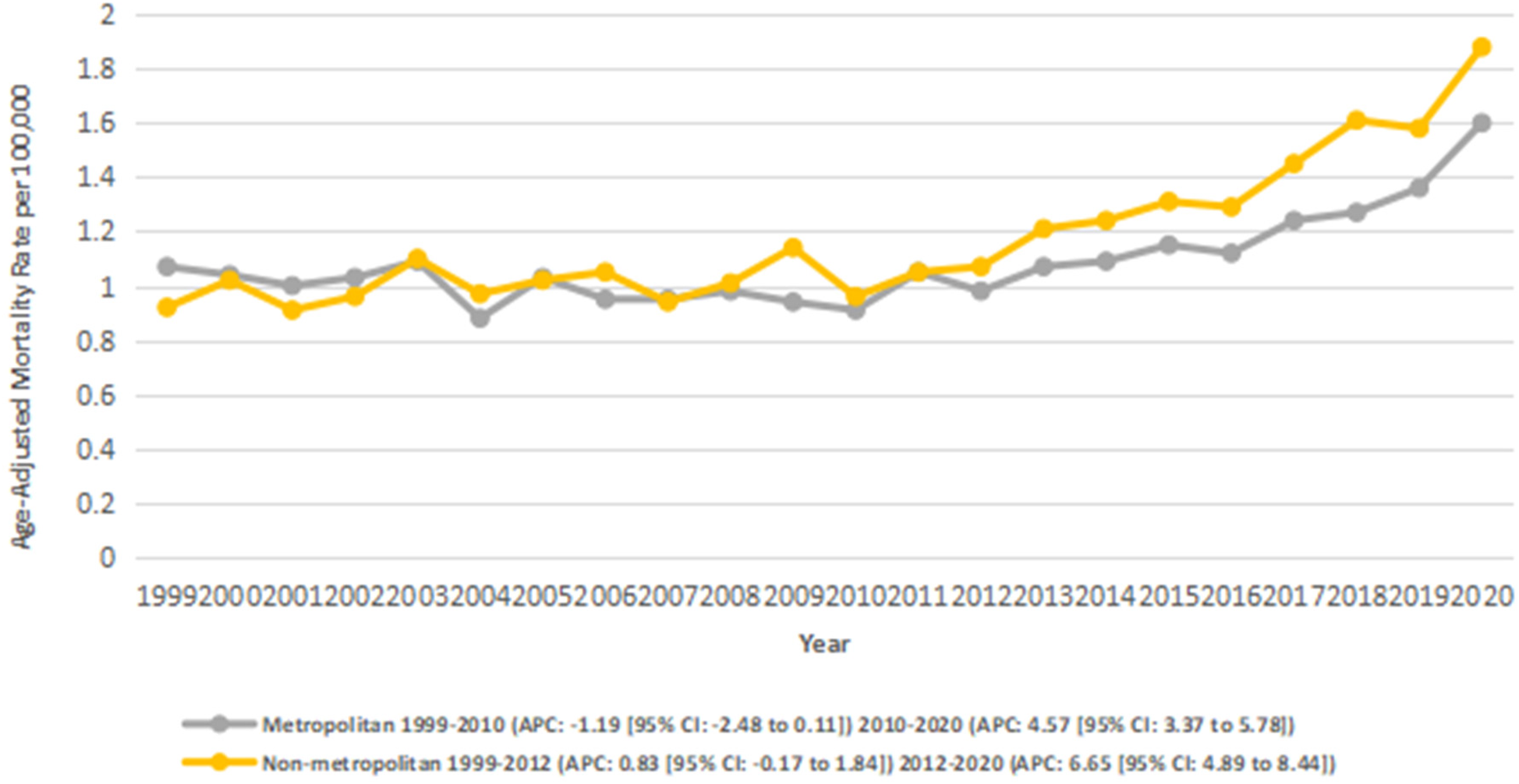

3.5 Stratified by urbanization

Across the study period, nonmetropolitan areas exhibited consistently higher AAMRs compared to metropolitan areas, with overall AAMRs of 1.2 and 1.1, respectively. Both metropolitan and nonmetropolitan regions experienced overall increasing trends from 1999 to 2020. In non-metropolitan areas, the AAMRs increased significantly (AAPC: 3.01*; 95% CI: 2.17–3.87; p < 0.001), and from 2 to 3 in metropolitan areas (AAPC: 1.51*; 95% CI: 0.68–2.34; p = 0.003).

According to segmental data, metro areas showed a nonsignificant decline from 7.17 in 1999 to 4.38 in 201 (APC: −1.19; 95% CI: −2.49 to 0.12; p = 0.072), followed by a significant increase from 4.38 in 2010 to 4.89 in 2020 (APC: 4.57*; 95% CI: 3.38–5.78; p < 0.001).

In non-metro areas, there was an initial non-significant incline from 7.87 in 1999 to 7.22 in 2012 (APC: 0.83; 95% CI: −0.17 to 1.85; p = 0.10), which was followed by a significant increase from 7.22 in 2012 to 5.34 in 2020 (APC: 6.66*; 95% CI: 4.90–8.45; p < 0.001) (Figure 5) (Supplementary Tables 3, 7).

Figure 5

Atrial fibrillation and rheumatic heart disease-related AAMRs per 100,000 stratified by urban-rural Status in adults in the United States 1999–2020.

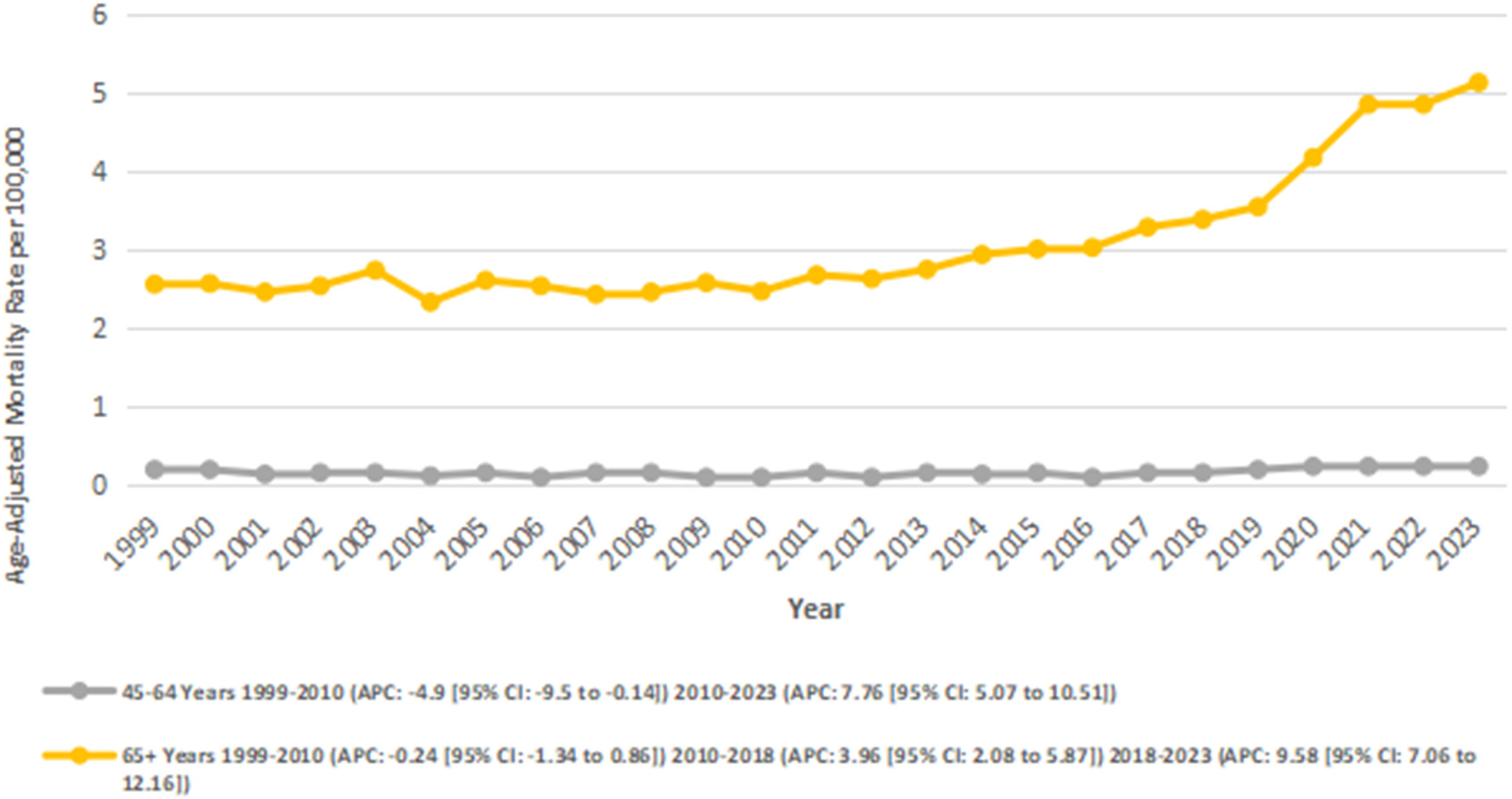

3.6 Stratified by age groups

We also analyzed data for age groups: 45–64 and 65+. The highest number of deaths occurred in the 65+ age group (number of deaths: 33,848; overall AAMR: 3.05), followed by the 45–64 age group (number of deaths: 2,853; overall AAMR: 0.14).

The overall trend was stable for adults aged 45–64 as the AAMR increased nonsignificantly from 0.18 to 0.22 between 1999 and 2023 (AAPC: 1.74; 95% CI: −0.75 to 4.30; p = 0.17), with notable fluctuations across periods. A significant decrease was observed from 0.18 in 1999 to 0.08 in 2010 (APC: −4.94*; 95% CI: −9.51 to −0.14; p = 0.044), followed by a significant increase from 0.08 in 2010 to 0.22 in 2023 (APC: 7.76*; 95% CI: 5.07 to 10.52; p = 0.005).

In the 65+ age group, there was a significant overall increase in AAMR from 2.55 in 1999 to 5.13 in 2023 (AAPC: 3.14*; 95% CI: 2.25–4.03; p < 0.001). This group experienced a mild and nonsignificant decline in AAMRs from 2.55 in 1999 to 2.46 in 2010 (APC: −0.24; 95% CI: −1.34 to 0.87; p = 0.65), followed by a significant increase from 2.46 in 2010 to 3.38 in 2018 (APC: 3.96*; 95% CI: 2.09–5.87; p = 0.003), and from 3.38 in 2018 to 5.13 in 2023 (APC: 9.59*; 95% CI: 7.07–12.17; p < 0.001) (Figure 6) (Supplementary Tables 3, 8).

Figure 6

Atrial fibrillation and rheumatic heart disease-related AAMRs per 100,000 stratified by Age in adults in the United States from 1999 to 2023.

4 Discussion

AF and RHD are of major concern to cardiovascular disease entities globally—especially for low- and middle-income countries but still a latent contributor to morbidity and mortality in higher-income countries such as the United States (12, 23, 24). Together they bring risk and exacerbate negative cardiovascular events by creating a separate, high-risk population. In this study, we present the study of national mortality trends from all cause deaths related to AF-RHD-related deaths across groups, geographic regions, and structural characteristics from 1999 to 2023.

Among US adults ages 45 and older, there were 36,701 deaths attributed to AF-RHD from 1999 to 2023. For adults 45 and older, the AAMR rose dramatically from 1.04 to 2.00. This upward trend was consistent with the national data showing an increasing mortality rate especially among older adults with AF-RHD, most likely due to an increasing burden of comorbidities (25–27). In the first decade, 1999–2010, there was a decline in AAMR, though not statistically significant. We speculate the decline might reflect some small early on cardiovascular improvements due to changing care and a focus on secondary prevention. After 2010, there was a steady and statistically significant increase in AAMR related to AF-RHD with the largest increase from 2018 to 2021 as potentially driven by age, more comorbidities, later complications and delayed chronic care management in the wake of COVID-19 (26, 28). The period from 2021 to 2023 appears to show a disturbing plateau, which could be attributable to an observational lag and/or time lag associated with system recovery, but we will need to continue to monitor the trends.

Women demonstrated a quite disproportionate higher death rate and consistent higher AAMR, despite AF usually predominating in men. This sex-based paradox exists amongst multiple population-based work, possibly because women with AF have greater stroke risk, which may also be related to under-treatment, under-diagnosis (27, 29, 30). The increased mortality was in both sexes post-2010, with recurrently higher relative increase in mortality shown in men compared to women. This recurring increase of death, is consistent with emerging literature regarding sex-differences in AF complications and suggests more nuanced clinical algorithms be developed that incorporate specific female risk stratification (31, 32). Notably, women experienced approximately twice the mortality rate of men, highlighting a substantial and persistent sex-based disparity. This finding reinforces evidence that women with AF often present later, receive less aggressive rhythm or anticoagulation therapy, and may have underrecognized valvular or structural heart disease. The higher mortality among females despite the lower overall prevalence of AF underscores the importance of sex-specific diagnostic vigilance, individualized anticoagulation strategies, and equitable access to specialized cardiovascular care.

We stratified by race and ethnicity and noted considerable differences. NH white individuals had the largest estimated absolute mortality burden and the highest age-adjusted mortality risk. The NH White data showed an interesting trajectory; there was a slight decline until 2010, and then there was a relatively large and sustained increase. This trajectory mirrors wider cardiometabolic literature describing increased mortality in mid-to-later life White Americans attributed to chronic disease and behavioral health comorbidities (33, 34). NH black adults had the most delayed rise in mortality rates, however the recent steep rise may confirm systemic barriers to timely diagnosis and anticoagulation, as well as a higher baseline prevalence of hypertension and heart failure (35). Hispanic adults also showed reversal from early declines to large increases in mortality rates post-2013.

Geographic differences were notable, with the highest overall AAMRs in the West, followed the Midwest, Northeast, and South. The higher mortality in the Western region may be multifactorial, reflecting demographic shifts, aging population growth, limited access to specialized cardiovascular care in rural Western states, and higher prevalence of metabolic risk factors such as obesity and diabetes. These factors collectively contribute to delayed diagnosis, treatment gaps, and poorer outcomes in AF-RHD patients (36, 37). Decreasing rates for the Northeast from 1999 to 2008 also had decent rate increases closely followed in other regions. The South being described as the “Stroke Belt” had the lowest overall baseline AAMRs but had the largest increase post-2017 for all regions reflective of a regional increase in cardiometabolic syndromes and healthcare access challenges (38). The West and Midwest realized significant epidemics in their late mortality AAMR rates. This trend highlights issues of healthcare infrastructure, deferred outpatient management or limited local expertise in forward rheumatic disease follow-up on mortality rates (2, 39). Regional variation supports a rationale for local context specific intervention strategies based on regional epidemiology, health system capacity and social determinants (40).

Urbanization analysis indicated that non-metropolitan areas had greater AAMR than metropolitan areas. Non-metropolitan mortality steadily increased overall, with an overwhelming temporal increase between 2012 and 2020. The fact that the mortality rates in rural areas are higher correlates with other cardiovascular findings that infer a multitude of concepts stemmed from the access to specialists earlier in the disease course, distance travelled to see specialist services, socioeconomic status, and hospital closures (41, 42). In urban metropolitan areas, AAMRs declined strongly in the early period, but the rate of decline slowed significantly after around 2010, consistent with previous studies showing a plateau in urban cardiovascular mortality trends (43).

Mortality was primarily seen in adults aged ≥65, where a clear increase in AAMR from 1999 to 2023. The acceleration since 2018 likely reflects increased frailty, polypharmacy, and the late AF/RHD complications in older patients (44). Adults aged 45–64 had much lower mortality, but also had a faster increase since 2010 which points to earlier onset, or delayed treatment in mid-life. This highlights the pressing need for age-appropriate primary prevention, especially adherence to anticoagulation and early detection of valvular disease in both middle aged and older adults (45, 46).

5 Strengths and limitations

This study represents the most recent longitudinal assessment of trends in AF-RHD mortality in the U.S. using comprehensive CDC WONDER data while stratifying by multiple variables. The longitudinal aspect of 25 years, a joinpoint analysis, and potential comparisons based on age-adjusted mortality rates enhances the interpretability and rigor of the findings. Limitations of this assessment include reliance on death certificate data, which may have misdiagnosed or downplayed AF or RHD as a contributory cause of a patient's death.

Also, there was no data collected on socioeconomic status, clinical comorbidities, and treatment exposures, which limits causal inference. Additionally, some racial categories and suppression of certain state-level data made it impossible to conduct some analysis.

6 Clinical and policy implications

The findings point to an urgent need for integrated management of AF and RHD, especially among women, older people, and populations outside of metropolitan areas. Population health initiatives ought to advocate for increased use of screening for valvular dysfunction, enhanced access to anticoagulation clinics, and expanded telehealth options for rural living (47–49). Geographic and racial disparities considered, explicit consideration of health inequities should inform policy changes that enable integrated management, culturally competent care access, accessibility to cardiac rehabilitation programs, and prevention initiatives built within communities (50–53). In light of the dramatic increase in mortality that began after 2018, and the dramatic rise in AF-RHD multifactorial approaches to improving healthcare system readiness for crises (such as pandemics) is warranted.

7 Conclusion and future directions

Between 1999 and 2023, mortality due to AF and RHD almost doubled in the United States, with the most pronounced acceleration occurring over the past decade. Substantial disparities by sex, race, region, and urbanization persist and appear to be widening. These trends highlight the need for prevention, early detection and equitable access to specialized cardiovascular care. Future studies designed to investigate these mortality trends should use real-world longitudinal cohorts and evaluate the impact of health system interventions to mitigate the mortality trends related to atrial fibrillation and rheumatic heart disease.

Statements

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were used in this study. The data can be accessed through the CDC WONDER platform, including the Multiple Cause of Death database available at: https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html.

Author contributions

MHe: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MSag: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AI: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AGo: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Writing – original draft. KP: Writing – original draft. ES: Writing – original draft. MHu: Writing – original draft. AGa: Writing – review & editing. MA: Writing – original draft. MSaj: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MJ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests that could have influenced the objectivity or outcome of this research.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1687555/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Noubiap JJ Nyaga UF Ndoadoumgue AL Nkeck JR Ngouo A Bigna JJ . Meta-Analysis of the incidence, prevalence, and correlates of atrial fibrillation in rheumatic heart disease. Glob Heart. (2020) 15(1):38. 10.5334/gh.807

2.

Salman A Larik MO Amir MA Majeed Y Urooj M Tariq MA et al Trends in rheumatic heart disease-related mortality in the United States from 1999 to 2020. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2024) 49(1):102148. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.102148

3.

Stacey I Seth R Nedkoff L Wade V Haynes E Carapetis J et al Excess deaths associated with rheumatic heart disease, Australia, 2013–2017. Emerg Infect Dis. (2024) 30(1):146. 10.3201/eid3001.230905

4.

Bennett J Zhang J Leung W Jack S Oliver J Webb R et al Incidence of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease among ethnic groups, New Zealand, 2000–2018. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27(1):36. 10.3201/eid2701.191791

5.

Ali E Mashkoor Y Latif F Zafrullah F Alruwaili W Nassar S et al Demographics and mortality trends of valvular heart disease in older adults in the United States: insights from CDC-wonder database 1999–2019. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev. (2024) 22:200321. 10.1016/j.ijcrp.2024.200321

6.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Atrial fibrillation as a contributing cause of death and Medicare hospitalization—United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2003) 52(7):128, 130-1. PMID: .

7.

Naveed MA Neppala S Chigurupati HD Rehan MO Ali A Naveed H et al Trends in stroke-related mortality in atrial fibrillation patients in the United States: insights from the CDC WONDER database. Am Heart J Plus. (2025) 49:100491. 10.1016/j.ahjo.2024.100491

8.

Khan MZ Patel K Patel KA Doshi R Shah V Adalja D et al Burden of atrial fibrillation in patients with rheumatic diseases. WJCC. (2021) 9(14):3252–64. 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i14.3252

9.

Wen-Hang QI , Society of Cardiology, Chinese Medical Association. Retrospective investigation of hospitalised patients with atrial fibrillation in mainland China. Int J Cardiol. (2005) 105(3):283–7. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.12.042

10.

Diker E Aydogdu S Özdemir M Kural T Polat K Cehreli S et al Prevalence and predictors of atrial fibrillation in rheumatic valvular heart disease. Am J Cardiol. (1996) 77(1):96–8. 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89145-x

11.

John B Lau CP . Atrial fibrillation in valvular heart disease. Card Electrophysiol Clin. (2021) 13(1):113–22. 10.1016/j.ccep.2020.11.007

12.

Shenthar J . Management of atrial fibrillation in rheumatic heart disease. Heart Rhythm O2. (2022) 3(6):752–9. 10.1016/j.hroo.2022.09.020

13.

Ahmad O Farooqi HA Ahmed I Jamil A Nabi R Ullah I et al Temporal trends in mortality related to stroke and atrial fibrillation in the United States: a 21-year retrospective analysis of CDC-WONDER database. Clin Cardiol. (2024) 47(12):e70058. 10.1002/clc.70058

14.

Akhtar M Dawood MH Khan M Raza M Akhtar M Jahan S et al Mortality patterns of coronary artery diseases and atrial fibrillation in adults in the United States from 1999 to 2022: an analysis using CDC WONDER. Am J Med Sci. (2025) 370(1):59–64. 10.1016/j.amjms.2025.03.011

15.

Antonioli M Mousavi I Medrano V Misra A Jia X Nimri N et al DEMOGRAPHIC DIFFERENCES IN CHRONIC RHEUMATIC HEART DISEASE MORTALITY IN THE UNITED STATES FROM 2016–2020. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2024) 83(13 Suppl):2142. 10.1016/S0735-1097(24)04132-9

16.

Grobman B Mansur A Lu CY . Social vulnerability and chronic kidney disease-associated mortality in the United States: 1999–2020. J Nephrol. (2025) 38:2397–405. 10.1007/s40620-025-02369-4

17.

Ibrahim AA Hemida MF Hussein M Saghir M Faisal MR Kritika FNU et al Disparities and trends in polycythemia Vera–related mortality in U.S. Adults aged ≥45 years from 1999 to 2023. ASIDE Int Med. (2025) 2(3):24–32. 10.71079/ASIDE.IM.092725233

18.

Von Elm E Altman DG Egger M Pocock SJ Gøtzsche PC Vandenbroucke JP . The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. (2008) 61(4):344–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

19.

Aggarwal R Chiu N Loccoh EC Kazi DS Yeh RW Wadhera RK . Rural-Urban disparities: diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and stroke mortality among black and white adults, 1999–2018. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77(11):1480–1. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.01.032

20.

Ingram DD Franco SJ . 2013 NCHS urban-rural classification scheme for counties. Vital Health Stat 2. (2014) (166):1–73. PMID: .

21.

Anderson RN Rosenberg HM . Age standardi-zation of death rates: implementation of the year 2000 standard. Natl Vital Stat Rep. (1998) 47(3):1–16, 20. PMID: .

22.

Joinpoint trend analysis software. Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 2016. Surveillance Research Program. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute (2025). Available online at:https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/(Accessed April 16, 2025).

23.

Amarasekara M Rodrigues TS Wijayarathne P Wong G Farouque O Lim H . Atrial fibrillation in developing and developed countries: a global epidemiological study. Heart Lung Circ. (2023) 32:S188. 10.1016/j.hlc.2023.06.152

24.

Ghamari S Abbasi-Kangevari M Saeedi Moghaddam S Aminorroaya A Rezaei N Shobeiri P et al Rheumatic heart disease is a neglected disease relative to its burden worldwide: findings from global burden of disease 2019. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11(13):e025284. 10.1161/JAHA.122.025284

25.

Cheng S He J Han Y Han S Li P Liao H et al Global burden of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter and its attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2021. Europace. (2024) 26(7):euae195. 10.1093/europace/euae195

26.

Romiti GF Corica B Lip GYH Proietti M . Prevalence and impact of atrial fibrillation in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. (2021) 10(11):2490. 10.3390/jcm10112490

27.

Jackevicius CA . Sex differences in stroke risk among older patients with recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation. JAMA. (2012) 307(18):1952. 10.1001/jama.2012.3490

28.

Dimri I Roguin A Hamuda N Abu Fanne R Barel M Leshem E et al The trends in atrial fibrillation-related mortality before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic peak in the United States. J Clin Med. (2024) 13(16):4813. 10.3390/jcm13164813

29.

Buhari H Fang J Han L Austin PC Dorian P Jackevicius CA et al Stroke risk in women with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(2):104–13. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad508

30.

Piazza G Hurwitz S Goldhaber SZ . Stroke risk factors and outcomes among hospitalized women with atrial fibrillation. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2021) 52(4):1023–31. 10.1007/s11239-021-02482-8

31.

Preda A Giordano F Giani V Guarracini F Mazzone P . Accelerated adverse atrial remodeling in women with atrial fibrillation: results from studies using electroanatomic mapping systems. Am J Cardiol. (2023) 203:524–5. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.07.124

32.

Campbell ML Larson J Farid T Westerman S Lloyd MS Shah AD et al Sex-based differences in procedural complications associated with atrial fibrillation catheter ablation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2020) 31(12):3176–86. 10.1111/jce.14758

33.

Qamar U Naeem F Agarwal S . Trends and disparities in atrial fibrillation-related mortality among adults with co-morbid diabetes mellitus in the United States. Eur J Clin Invest. (2025) 55(5):e14393. 10.1111/eci.14393

34.

Wattigney WA . Increased atrial fibrillation mortality: united States, 1980–1998. Am J Epidemiol. (2002) 155(9):819–26. 10.1093/aje/155.9.819

35.

Jain V Rao B Quintero E Shah AD Merchant FM El-Chami MF et al Trends and disparities in atrial fibrillation and stroke related mortality in the United States from 1999 to 2020. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. (2025) 48(2):280–3. 10.1111/pace.15111

36.

Parcha V Kalra R Suri SS Malla G Wang TJ Arora G et al Geographic variation in cardiovascular health among American adults. Mayo Clin Proc. (2021) 96(7):1770–81. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.12.034

37.

Cheema ZZ Atout M Dohadwala TK Deiab AT Abouayana A Mesmar H et al Trends and disparities in dilated cardiomyopathy related mortality among adults in the United States: a CDC WONDER analysis (1999–2023). PLoS One. (2025) 20(10):e0333525. 10.1371/journal.pone.0333525

38.

Singh G . Widening geographical disparities in cardiovascular disease mortality in the United States, 1969–2011. Int J MCH AIDS. (2014) 3(2):134. 10.21106/ijma.46

39.

Pincus T Gibson KA Block JA . Premature mortality: a neglected outcome in rheumatic diseases?Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). (2015) 67(8):1043–6. 10.1002/acr.22554

40.

Chew DS Au F Xu Y Manns BJ Tonelli M Wilton SB et al Geographic and temporal variation in the treatment and outcomes of atrial fibrillation: a population-based analysis of national quality indicators. CMAJ Open. (2022) 10(3):E702–13. 10.9778/cmajo.20210246

41.

Moustafa A Elzanaty A Karim S Eltahawy E Maraey A Kahaly O et al Mortality post in-patient catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in rural versus urban areas: insights from national inpatient sample database. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2024) 49(1):102183. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.102183

42.

Teppo K Airaksinen KEJ Halminen O Jaakkola J Linna M Haukka J et al Rural–urban and geographical differences in prognosis of atrial fibrillation in Finland: a nationwide cohort study. Scand J Public Health. (2024) 52(7):785–92. 10.1177/14034948231189918

43.

Cross SH Mehra MR Bhatt DL Nasir K O'Donnell CJ Califf RM et al Rural-Urban differences in cardiovascular mortality in the US, 1999–2017. JAMA. (2020) 323(18):1852–4. 10.1001/jama.2020.2047

44.

Nguyen TN Cumming RG Hilmer SN . The impact of frailty on mortality, length of stay and Re-hospitalisation in older patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. (2016) 25(6):551–7. 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.12.002

45.

Rich MW . Anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: time to revise the paradigm?J Am Geriatr Soc. (2023) 71(2):365–7. 10.1111/jgs.18159

46.

Parks AL Frankel DS Kim DH Ko D Kramer DB Lydston M et al Management of atrial fibrillation in older adults. Br Med J. (2024) 386:e076246. 10.1136/bmj-2023-076246

47.

Orchard JJ Neubeck L Freedman B Webster R Patel A Gallagher R et al Atrial fibrillation screen, management and guideline recommended therapy (AF SMART II) in the rural primary care setting: an implementation study protocol. BMJ Open. (2018) 8(10):e023130. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023130

48.

d’Arcy JL Coffey S Loudon MA Kennedy A Pearson-Stuttard J Birks J et al Large-scale community echocardiographic screening reveals a major burden of undiagnosed valvular heart disease in older people: the OxVALVE population Cohort Study. Eur Heart J. (2016) 37(47):3515–22. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw229

49.

Chambers JB Shah BN Prendergast B Lawford PV McCann GP Newby DE et al Valvular heart disease: a call for global collaborative research initiatives. Heart. (2013) 99(24):1797–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303964

50.

Garg K Satti DI Yadav R Brumfield J Akwanalo CO Mesubi OO et al Global health inequities in electrophysiology care. JACC Adv. (2024) 3(12):101387. 10.1016/j.jacadv.2024.101387

51.

Bugiardini R Gale CP Gulati M Anand SS Maas AHEM Townsend N et al Announcing the lancet regional health-Europe commission on inequalities and disparities in cardiovascular health. Lancet Reg Health Eur. (2024) 41:100926. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.100926

52.

Ayinde H Markson F Ogbenna UK Jackson L . Addressing racial differences in the management of atrial fibrillation: focus on black patients. J Natl Med Assoc. (2024) 116(5):490–8. 10.1016/j.jnma.2023.11.007

53.

Benjamin EJ Thomas KL Go AS Desvigne-Nickens P Albert CM Alonso A et al Transforming atrial fibrillation research to integrate social determinants of health. JAMA Cardiol. (2023) 8(2):182. 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.4091

Summary

Keywords

atrial fibrillation, rheumatic heart disease, trends, mortality, joinpoint regression analysis

Citation

Hemida MF, Saghir M, Ibrahim AA, Goel A, Amir Jalal A, Patel K, Saghir E, Hussein M, Gamal A, Alsaadi M, Sajjad M, Tablawy M, Alkasabrah O and Jaber Amin MH (2025) Temporal trends in mortality involving atrial fibrillation and rheumatic heart disease: a 25-year nationwide analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1687555. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1687555

Received

17 August 2025

Revised

14 November 2025

Accepted

21 November 2025

Published

12 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Nicola Mumoli, ASST Valle Olona, Italy

Reviewed by

Adam Hartley, Imperial College London, United Kingdom

Mohammad Amin Khadembashiri, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Hamidreza Fallahabadi, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Hemida, Saghir, Ibrahim, Goel, Amir Jalal, Patel, Saghir, Hussein, Gamal, Alsaadi, Sajjad, Tablawy, Alkasabrah and Jaber Amin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Mohammed Hammad Jaber Amin mohammesjaber123@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.