- Department of Cardiology, Chongzhou People’s Hospital, Chongzhou, Sichuan, China

Heart failure (HF) is a major global health problem associated with high illness rates, mortality, and healthcare costs. Although advances in diagnosis and therapy have improved outcomes for some patients, effective treatment—especially for HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)—remains limited. HF develops through complex interactions among neurohormonal activation, metabolic remodeling, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, fibrosis, and microvascular impairment. Recent discoveries in these areas have revealed new molecular and cellular targets that may lead to more precise therapies. Novel pharmacological agents, metabolic modulators, device-based interventions, and regenerative approaches are reshaping the treatment landscape. In addition, personalized strategies such as multi-omics profiling, biomarker-guided management, and artificial intelligence–assisted diagnosis hold promise for better risk prediction and individualized care. However, translating mechanistic discoveries into clinical benefit remains a challenge. Future research integrating molecular insights with clinical phenotyping will be essential to achieve precision treatment and improved outcomes in patients with HF.

1 Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome characterized by impaired ventricular filling or ejection due to structural or functional cardiac abnormalities. It leads to symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, and edema, and is associated with poor quality of life and prognosis (1). Based on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), HF is classified into HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, LVEF <40%), mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF, 40%–49%), and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, ≥50%) (2, 3). Notably, HFpEF now accounts for more than half of all HF cases and represents a major therapeutic challenge (4).

Despite significant progress in pharmacological and device-based therapies, the overall prognosis of HF remains poor, with high rates of hospitalization and mortality (5). While neurohormonal inhibition with ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists has greatly improved outcomes in HFrEF, similar success has not been achieved in HFpEF (6). No current treatment convincingly reduces mortality in HFpEF, largely because of its heterogeneous mechanisms involving metabolic abnormalities, inflammation, microvascular dysfunction (MVD), and systemic comorbidities (7). These limitations highlight an urgent unmet clinical need for new, mechanism-based and precision-oriented therapeutic strategies.

This review therefore summarizes recent advances in understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms of HF and discusses how these insights can inform novel pharmacological, device-based, and personalized treatment approaches aimed at improving outcomes across diverse HF phenotypes.

2 Methodological framework

This narrative review was conducted to synthesize recent advances in the mechanistic understanding and emerging therapeutic strategies of HF. A structured literature search was performed across the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases for studies published between January 2010 and September 2025. The search combined the following keywords and Boolean operators: “heart failure” AND (“molecular mechanism” OR “pathophysiology” OR “metabolic remodeling” OR “mitochondrial dysfunction” OR “fibrosis” OR “epigenetic regulation” OR “precision medicine” OR “therapeutic strategies”). Inclusion criteria were: (1) peer-reviewed original articles or reviews; (2) studies involving human subjects, relevant animal models, or translational data; and (3) publications in English. Exclusion criteria included case reports, editorials, conference abstracts, and non-peer-reviewed materials (8).

Reference lists of relevant articles and recent high-impact reviews were also screened to ensure comprehensive coverage. The quality and relevance of studies were assessed based on methodological rigor and contribution to mechanistic or therapeutic understanding. While this review is primarily narrative in scope, it follows key principles of the PRISMA-ScR framework, ensuring transparent reporting of literature identification and selection. All included references were cross-verified for accuracy and represent the most recent and impactful studies available at the time of writing (9).

3 Novel insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms of HF

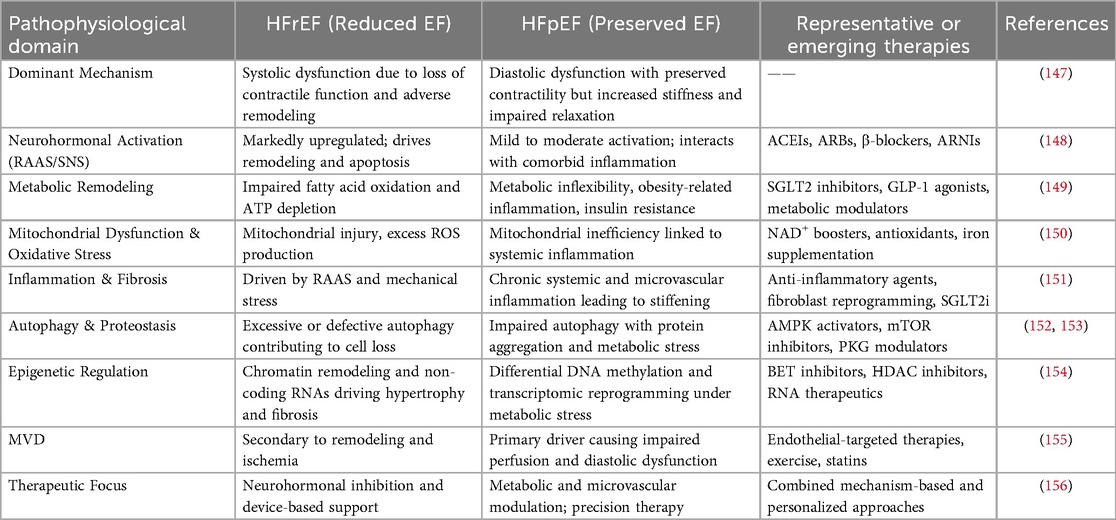

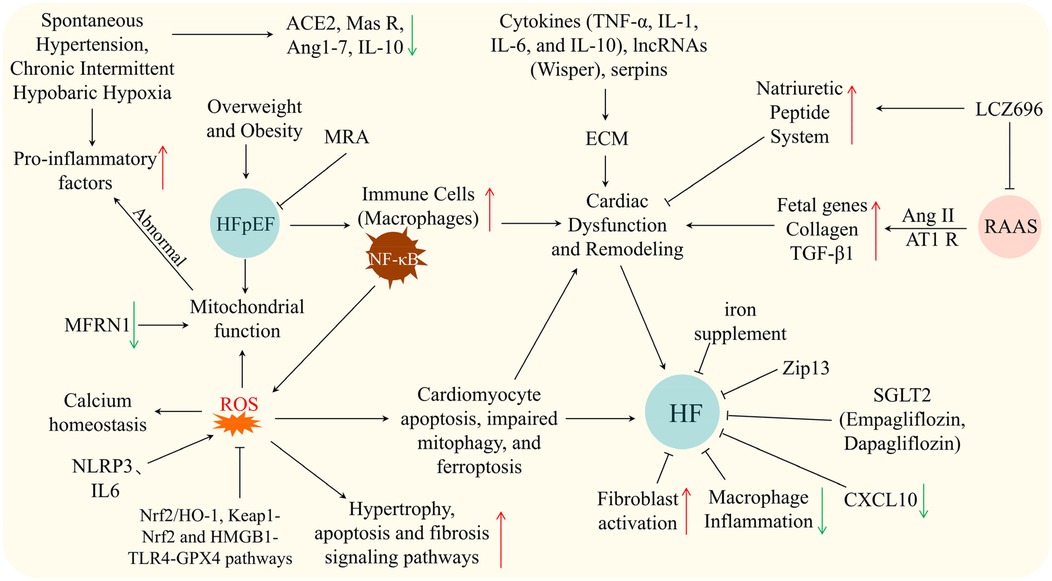

The pathophysiology of HF is highly complex, involving multiple mechanisms such as neuroendocrine activation, metabolic remodeling, inflammatory responses, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cellular senescence (10). These interacting processes, summarized in Figure 1, highlight the multi-layered nature of HF progression. In recent years, advances in experimental techniques have progressively elucidated more specific molecular mechanisms, providing a theoretical foundation for precision therapy.

Figure 1. Schematic showing mechanisms and therapies in HF/HFpEF: triggers (hypertension, hypoxia, obesity), pathways (inflammation, ROS, RAAS, cytokines), cellular events, and interventions. Arrows: ↑ upregulation, ↓ downregulation, black for causal relationships, ⊥ for inhibition.

3.1 Experimental insights into RAAS-mediated neuroendocrine activation in HF

Overactivation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is a major driving factor in the onset and progression of HF (11, 12). Under pathological conditions such as myocardial injury and hypertension, the key RAAS effector molecule angiotensin II (Ang II) mediates signal transduction via the AT1A receptor, upregulating the expression of fetal genes, collagen, and TGF-β1 in non-infarcted regions, thereby promoting left ventricular dilation, fibrosis, and dysfunction, and accelerating ventricular remodeling and HF progression (13). Multiple animal studies have confirmed the cardioprotective effects of RAAS inhibition on cardiac structure and function. For instance, Woźniak et al. (14) demonstrated in a Tgaq*44 dilated cardiomyopathy mouse model that early combined administration of an ACE inhibitor (perindopril) and an aldosterone receptor antagonist (canrenone) preserved systolic function, whereas late intervention mainly attenuated ventricular dilation, indicating a stage-dependent therapeutic effect. Chen et al. (15) reported in spontaneously hypertensive rats that chronic intermittent hypobaric hypoxia downregulated ACE and AT1 receptor expression, upregulated ACE2 and Mas receptor expression, reduced Ang II and pro-inflammatory cytokines, and increased Ang1–7 and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, thereby improving vascular relaxation and remodeling. Hawlitschek et al. (16) found that captopril alone or in combination with nifedipine significantly reduced blood pressure, alleviated cardiac hypertrophy, and prevented myocardial fibrosis. Yi et al. (17) showed that time-restricted feeding suppressed the ACE–Ang II–AT1 axis, reducing Ang II-mediated cardiac remodeling and dysfunction, thereby lowering blood pressure and exerting cardioprotective effects. Clinically, McMurray et al. (18) demonstrated in the PARADIGM-HF trial that the angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) LCZ696 not only inhibited RAAS activity but also enhanced natriuretic peptide system function, synergistically improving cardiac load and neurohormonal imbalance, and producing greater reductions in cardiovascular mortality and HF rehospitalization compared with the ACE inhibitor enalapril. Collectively, these findings underscore the central pathological role of RAAS in cardiovascular disease progression, and indicate that RAAS inhibition yields significant improvements in cardiac structure and function in experimental models, with clear prognostic benefits in clinical practice.

3.2 Exercise and metabolic modulation in HF

Metabolic abnormalities are a key component of HF pathophysiology. Overweight and obesity, even in the absence of metabolic syndrome, significantly increase HF risk (by 37%–85%), with cardiovascular event risk rising proportionally with the number of metabolic syndrome components (19). In HFpEF, epicardial adipose tissue volume is markedly increased and correlates with cardiac dysfunction, metabolic abnormalities, and inflammatory markers (20).

Pharmacologically, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) reduce HF hospitalization and cardiovascular mortality in HFrEF, with more modest benefits in HFmrEF/HFpEF and an increased risk of hyperkalemia (21). Non-steroidal MRA finerenone significantly reduces HF composite outcomes in patients with recent worsening HF (WHF) without increasing adverse events (22), while finerenone also lowers the risk of new-onset diabetes by 24% in HF patients without baseline diabetes (23). Among SGLT2 inhibitors, dapagliflozin achieves similar diuretic efficacy to metolazone but with less electrolyte disturbance and renal function deterioration (24), whereas empagliflozin shows no short-term improvement in myocardial energy metabolism (25). The mitochondrial uncoupler HU6 may enhance metabolic flexibility and potentially improve cardiac function in obesity-related HFpEF (26).

Exercise interventions show heterogeneous effects. In HFpEF, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) does not outperform moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in improving peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) (27). However, in coronary artery disease and some chronic HF populations, HIIT significantly improves VO2peak, heart rate variability, and left ventricular function (28–30). Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) reduces HF and all-cause rehospitalization and improves exercise capacity and quality of life, with no mortality benefit (31), while hybrid comprehensive telerehabilitation (HCTR) yields short-term functional gains without long-term clinical benefit (32). Additionally, exercise oscillatory ventilation independently predicts mortality and heart transplantation in HFrEF (33). Other interventions, such as oral polysaccharide iron in iron-deficient HFrEF, do not improve exercise capacity or cardiac function (34). Collectively, these findings highlight the need for integrated metabolic control, optimized pharmacotherapy, and individualized exercise prescriptions to maximize benefits in HF management.

3.3 Mitochondrial dysfunction and iron metabolism in HF

Accumulating evidence from basic and clinical studies indicates that mitochondrial dysfunction is a central mechanism in the development and progression of HF. Impaired mitochondrial respiration in cardiomyocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) exacerbates systemic inflammation. Zhou et al. (35) demonstrated that MitoDAMPs suppress complex I activity in PBMCs via IL-6 induction, whereas supplementation with the NAD+ precursor nicotinamide riboside (NR) enhances mitochondrial respiration and attenuates pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. Disruption of mitochondrial iron homeostasis also contributes critically to HF pathophysiology. Li et al. (36) reported that cardiac-specific Zip13 knockout mice exhibit severe contractile dysfunction, with decreased mitochondrial iron and elevated cytosolic iron; iron supplementation or overexpression of the mitochondrial iron transporter MFRN1 partially restores mitochondrial function, highlighting the essential role of ZIP13 in maintaining myocardial mitochondrial iron balance. Clinically, approximately 23% of HF patients present with left ventricular myocardial iron deficiency, which correlates with reduced activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes and TCA cycle enzymes, as well as impaired oxidative stress defense (37). In vitro iron deprivation further confirms that impaired Fe–S cluster-dependent complex I–III activity significantly inhibits ATP production and cardiomyocyte contractility, which can be reversed by iron supplementation (38). Furthermore, frataxin deficiency or SLC25A3 loss perturbs NAD+ metabolism, mitochondrial biogenesis, and fusion/fission dynamics, leading to metabolic dysfunction, Ca2+ handling abnormalities, and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (39, 40), while mitochondrial transplantation partially rescues these phenotypes. In endothelial cells, lipid droplet formation mitigates lipotoxicity, preserves mitochondrial function, and inhibits ferroptosis, thereby protecting cardiac microvascular integrity (41). Clinically, intravenous iron administration or SGLT2 inhibition with empagliflozin improves mitochondrial energy metabolism, enhances iron utilization and erythropoiesis, and subsequently improves cardiac and skeletal muscle function, leading to enhanced exercise capacity and left ventricular performance in HF patients (42–45). Collectively, mitochondrial dysfunction in HF involves deficits in energy metabolism as well as dysregulation of iron homeostasis and NAD+ levels, and targeting mitochondrial pathways represents a promising therapeutic strategy to improve cardiac function.

3.4 Inflammation in HF

A growing body of epidemiological and clinical evidence demonstrates that inflammation plays a central role in the onset, progression, and prognosis of HF, particularly HFpEF. Elevated systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) is positively associated with HF risk in multiple populations, including NHANES cohorts, smokers, and patients with diabetes (46, 47). Chronic immune-inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, increase the risk of both ischemic and non-ischemic HF, with the highest risk observed in rheumatoid factor–positive individuals (48). HFpEF is frequently accompanied by metabolic abnormalities and activation of systemic inflammatory protein networks, in which specific mediators—TNFR1, UPAR, IGFBP7, and GDF-15—partially mediate structural and functional cardiac impairment (49), while distinct inflammatory patterns are associated with adverse outcomes, reduced exercise capacity, and impaired quality of life (50). These findings support the existence of a “comorbidity–inflammation–HF” pathological axis, in line with mechanistic insights that metabolic derangements and inflammatory burden interact to drive metabolic inflammation (metainflammation) (51), promoting ventricular remodeling through immune cell polarization, pro-inflammatory cytokine release, oxidative stress, and pathological fibrosis. Experimental studies further demonstrate that HF is associated with pro-inflammatory activation of immune cells (e.g., macrophages), mitochondrial dysfunction, and activation of key signaling pathways such as NF-κB; inhibiting macrophage inflammation, promoting M2 polarization, or restoring mitochondrial function can attenuate cardiac dysfunction and remodeling (35, 52). In terms of anti-inflammatory interventions, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as empagliflozin and dapagliflozin exhibit significant cardioprotective effects in HF models and patients (53, 54), partly independent of SGLT2 itself, involving downregulation of CXCL10 (55), suppression of macrophage inflammation, and modulation of fibroblast activation. Additional approaches—including low-level transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (56, 57), selenium-enriched diets (58), NAD precursors (35), NF-κB pathway inhibitors, and certain herbal preparations such as processed Aconitum extracts (59)—have also demonstrated potential to improve cardiac function via inflammation attenuation. However, previous trials of anti-inflammatory agents such as TNF-α antagonists have shown limited or even harmful effects in HF (48), suggesting that non-specific or isolated anti-inflammatory strategies may be insufficient. Collectively, these findings underscore that although inflammation is an indispensable mechanistic link in HF, the efficacy of anti-inflammatory therapy depends on pathway selectivity, timing of intervention, and alignment with patient phenotype, rather than broad cytokine inhibition. Future therapies may benefit from biomarker-guided and phenotype-specific strategies that better match the underlying inflammatory pathways in HF.

3.5 Oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte injury in HF

In HF, the high metabolic activity of cardiomyocytes renders them a primary source of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS), while neurohormonal activation, adrenergic overstimulation, and excessive mechanical stress induce cellular stress that disrupts redox homeostasis and impairs mitochondrial function (60, 61). Major ROS sources include mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes I/III, NADPH oxidases (Nox2/Nox4), xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR), nitric oxide synthases (NOS), monoamine oxidases (MAO), and p66shc. Enhanced activity of these enzymes establishes a ROS-driven vicious cycle, damaging mitochondrial DNA, proteins, and lipids, perturbing calcium homeostasis, and activating hypertrophic, apoptotic, and fibrotic signaling pathways (62–64). Excess ROS can further induce cardiomyocyte apoptosis, impaired mitophagy, and ferroptosis through IGF2BP2-dynamin2, PDE4D-CREB-SIRT1-PINK1/Parkin, and Piezo1/Yap1 signaling axes, accelerating myocardial remodeling and HF progression (65–67). Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome also exacerbates cardiomyocyte injury by promoting oxidative stress and pyroptosis (68). Under pathological conditions, excessive ROS generation combined with impaired antioxidant defense systems, including SOD, GSHPx, catalase, Trx/TrxR, and GSH, leads to cumulative oxidative damage, further compromising cardiomyocyte structure and function (62). Therapeutic strategies activating Nrf2/HO-1, Keap1-Nrf2, and HMGB1-TLR4-GPX4 pathways can suppress ROS production, restore mitochondrial function, and mitigate cardiomyocyte apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis, thereby improving pathological cardiac remodeling (69–71). Collectively, ROS generation in cardiomyocytes and its dynamic regulation constitute a central driver of myocardial remodeling and HF progression, providing a mechanistic basis for targeted interventions against cardiomyocyte oxidative stress (72).

3.6 Fibrosis and extracellular matrix remodeling in HF

Myocardial fibrosis is a central pathological process in the development and progression of HF, characterized by the activation of cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) and their differentiation into myofibroblasts (myoFbs), which mediate excessive deposition and crosslinking of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, ultimately leading to ventricular stiffening, myocardial remodeling, and functional impairment (73–75). Fibrosis can represent either a reparative response or maladaptive remodeling: acute myocardial injury, such as myocardial infarction, induces replacement fibrosis to preserve myocardial structural integrity, whereas chronic pressure overload triggers reactive fibrosis, resulting in diffuse interstitial and perivascular collagen accumulation and persistent disruption of left and right ventricular function (76, 77).

CFs sense mechanical stress and integrate signaling via integrin-FAK pathways, AngII downstream cascades, and TGF-β/Smad and non-canonical MAPK/PI3K/AKT pathways to regulate proliferation, migration, and phenotypic transformation, thereby driving excessive deposition of type I/III collagen and other matrix proteins (73, 74, 78, 79). Additionally, immune cell-mediated inflammation, cytokines (including TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-10), long noncoding RNAs such as Wisper, fibronectin, and serpins participate in myocardial ECM remodeling by modulating fibroblast activity, collagen crosslinking, and matrix degradation, further influencing fibrotic progression (80–83).

Myocardial fibrosis not only reduces diastolic compliance and impairs systolic function but also disrupts intercellular signaling and increases the risk of arrhythmias (84, 85). Interventions such as left ventricular assist device (LVAD) unloading, HDAC inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors, and direct fibroblast reprogramming have been shown to partially reverse fibrosis and structural-functional abnormalities, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target in HF (75, 86–88). Collectively, myocardial fibrosis, through ECM remodeling, plays a pivotal role in HF pathogenesis, and the complex molecular regulatory networks and cellular heterogeneity underlying this process provide important directions for future precision therapies (89–91).

3.7 Autophagy and proteostasis dysregulation in HF

Autophagic dysregulation and protein homeostasis imbalance play central roles in the pathogenesis and progression of HF. Autophagy maintains cardiomyocyte protein quality control (PQC), clears misfolded and toxic proteins, and preserves mitochondrial function, with moderate activation conferring cardioprotection (92, 93). However, excessive or insufficient autophagy disrupts protein homeostasis, induces mitochondrial damage, and triggers apoptosis or autophagy-dependent cell death (autosis), exacerbating cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, and HF progression (94, 95). PKG signaling and PQC dysfunction accelerate hypertrophy, remodeling, and cardiomyocyte loss, whereas pharmacological PKG activation restores PQC and improves cardiac function (96). BAG3 maintains protein homeostasis via chaperone-assisted selective autophagy (CASA), and its deficiency leads to age-dependent autophagic dysregulation and early-onset cardiomyopathy (97).

In HFpEF, diabetes promotes NF-κB/IL-6/NLRP3-mediated inflammation and oxidative stress, suppresses NO-sGC-cGMP-PKG and AKT/AMPK/mTOR-regulated autophagy, and impairs HSP27/HSP70-dependent PQC, increasing myocardial stiffness and diastolic dysfunction (98). Nrf2 regulates the ubiquitin–proteasome system and autophagy-related genes, and its dysfunction drives protein misfolding, hypertrophy, and HF development (99). Persistent mTORC1/4EBP1 activation under aging or metabolic–hypertensive stress disrupts protein homeostasis, accelerates toxic protein accumulation, and exacerbates HFpEF and cardiac aging (100, 101). Additional regulators, including ROR2, TRIM24, and Txlnb, modulate protein folding, ubiquitination, and calcium handling, further destabilizing protein homeostasis and impairing contractile function (102–105). Models of chronic kidney disease, premature aging, and rapid-growth broiler cardiomyopathy demonstrate that protein oxidation, glycation, and PQC disruption, combined with autophagic and mitochondrial dysfunction, accelerate pathological remodeling (106–108).

Recent studies have further delineated the crosstalk between autophagy, mitochondrial health, and proteostasis. Dysregulated mitophagy contributes to the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and excessive ROS generation, amplifying cardiomyocyte injury and maladaptive remodeling (109). Crosstalk between mTOR, AMPK, and sirtuin signaling fine-tunes autophagic flux, linking nutrient status, metabolic stress, and cellular aging to HF progression (110). Moreover, key autophagy mediators such as Beclin-1, ATG5, and TFEB are increasingly recognized as potential therapeutic targets because restoration of balanced autophagy—neither excessive nor suppressed—attenuates hypertrophy, fibrosis, and contractile dysfunction in preclinical models (111). These findings reinforce the translational potential of modulating the AMPK–mTOR–TFEB axis or enhancing mitophagy to improve proteostasis and delay HF progression.

Therapeutically, interventions such as tanshinone IIA, rapamycin, ginsenosides, and components of Si-Miao-Yong-An decoction modulate AMPK–mTOR–Beclin1-dependent autophagy, inhibit mTORC1 and ER stress, or restore mitophagy, thereby reducing apoptosis, improving function, and attenuating remodeling (112–115). Nutritional status further influences autophagic activity, highlighting the interplay between autophagy and protein homeostasis as a potential therapeutic target in chronic HF (116). Collectively, autophagic dysregulation and protein homeostasis imbalance constitute central mechanisms driving cardiomyocyte injury, remodeling, and HF progression, providing avenues for precision therapy (117).

3.8 MVD and endothelial abnormalities in HF

Multiple studies have demonstrated that MVD and coronary microvascular endothelial dysfunction are highly prevalent and play critical pathogenic roles in HF, particularly in HFpEF. Even in HFpEF patients without obstructive coronary artery disease, approximately 81% exhibit coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD), suggesting it as a potential therapeutic target (118). CMD can reduce coronary flow reserve and myocardial perfusion, thereby exacerbating myocardial ischemia, diastolic dysfunction, and oxidative stress, ultimately promoting HF progression and increasing cardiovascular risk (119). In HFpEF patients, coronary microvascular endothelial dysfunction involves both endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent mechanisms, with the latter closely associated with impaired diastolic function and adverse outcomes (120, 121).

MVD impairs endothelial cell function, decreases nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, and reduces coronary flow reserve, promoting left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and restrictive remodeling while compromising myocardial oxygen supply and preload reserve through multiple interacting pathways (122). Peripheral microvascular reactivity is also correlated with left ventricular structural and diastolic alterations, highlighting its role in early cardiac remodeling in HFpEF (123). Endothelial dysfunction in HF patients manifests as impaired vascular tone regulation, antioxidant capacity, and inflammatory modulation, which may be systemic or localized, and can serve as a prognostic marker while being partially modifiable by ACE inhibitors, statins, and regular exercise (124). Clinical studies further indicate that CMD restricts cardiac filling during exercise, reduces exercise capacity, and is closely linked to left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and myocardial ischemia (120). Additionally, HFpEF patients often present with arterial stiffening, impaired microvascular vasodilation, and abnormal venous capacitance, which collectively contribute to a complex pathophysiological network (125).

In summary, MVD and endothelial impairment constitute key pathogenic mechanisms in HF and HFpEF, promoting disease progression through myocardial ischemia, diastolic dysfunction, and adverse cardiac remodeling, while representing critical targets for early diagnosis, risk stratification, and individualized therapeutic intervention.

3.9 Epigenetic and transcriptomic regulation in HF

HF, particularly as a consequence of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), is intricately regulated by epigenetic and transcriptomic mechanisms. CFs, in response to injury, transition from a quiescent state to a highly collagen-secreting phenotype, thereby driving fibrosis and cardiac remodeling through excessive ECM deposition. This activation is precisely controlled by gene transcription, DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and intercellular signaling networks (126). Non-coding RNAs, including the lncRNA Wisper, interact with TIA1-related proteins to modulate pro-fibrotic enzyme expression, promoting fibrosis and adverse remodeling post-myocardial infarction, whereas antisense oligonucleotide-mediated silencing significantly alleviates fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction (83). Similarly, NAT10-mediated N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) modification of mRNAs enhances the stability and translation efficiency of CD47 and ROCK2 transcripts, thereby facilitating cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, fibrosis, and inflammatory responses; inhibition of NAT10 or treatment with Remodelin effectively improves left ventricular structure and function (127). Epitranscriptomic enzymes and non-coding RNAs—including miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs—coordinate gene transcription and translation in cardiomyocytes and the cardiac immune microenvironment, influencing remodeling, diastolic dysfunction, inflammation, and fibrosis, and thus represent promising targets for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic intervention in HF (128, 129).

Bromodomain and extra terminal domain (BET) family proteins, particularly BRD4, recognize histone acetylation marks and integrate super-enhancer and promoter regions of pro-fibrotic genes under cardiac stress, orchestrating NF-κB- and TGF-β-dependent fibrosis and contractile dysfunction while maintaining mitochondrial respiration and energy homeostasis under baseline conditions (130–132). Other epigenetic regulators, including DNA methyltransferases, protein methyltransferases, MLF1, HAND1, and Bmi1, modulate chromatin accessibility, enhancer-promoter looping, and mRNA splicing, thereby governing cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, fibrosis, calcium handling, and age-associated transcriptional programs (133–138). Environmental factors, such as bisphenol A and its analogs, can induce cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and alter DNA methylation patterns, illustrating the interplay between transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms in cardiac toxicity (139). Multi-omics analyses reveal disease-specific DNA methylation and non-coding RNA expression patterns across HF patients of distinct etiologies, with epigenetic reprogramming and transcriptional dysregulation jointly dictating myocardial function, fibrosis, and remodeling (140, 141). Furthermore, stem cells and their derived cardiomyocytes, through optimized differentiation and maturation, can repair myocardial infarction-induced injury and improve cardiac function in HF patients (142).

Beyond individual epigenetic modifiers, emerging multi-omics studies have revealed coordinated epigenetic remodeling that regulates transcriptional plasticity in both cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts. Disease-specific DNA methylation signatures correlate with metabolic impairment and hypertrophy, whereas histone acetylation and m6A RNA modifications fine-tune gene networks that govern fibrosis, inflammation, and energy metabolism (143). Notably, pharmacological modulation of epigenetic pathways—such as inhibition of BRD4 or HDACs—has demonstrated the ability to reverse maladaptive gene expression, attenuate fibrosis, and improve ventricular function in preclinical models (144). These findings underscore epigenetic regulation as a mechanistically distinct yet clinically relevant avenue for precision therapy in both HFrEF and HFpEF (Table 1).

Collectively, HF pathogenesis is orchestrated by multilayered networks encompassing non-coding RNA regulation, epigenetic enzymes, chromatin remodeling, and epitranscriptomic modifications, providing a comprehensive molecular framework for mechanistic understanding and potential precision therapeutic strategies (145, 146).

3.10 Evidence quality and limitations of current data

The strength of available evidence across HF mechanisms and therapies varies substantially. Mechanistic insights are often derived from preclinical or single-center translational studies, which provide valuable biological understanding but are limited by small sample sizes, short durations, and lack of clinical endpoints (157). Conversely, large RCTs—such as those evaluating RAAS inhibition, β-blockers, and SGLT2 inhibitors—offer high-level evidence but typically target broad HF populations without molecular stratification (158). Conflicting findings among studies frequently reflect differences in experimental design, patient phenotype, and outcome measures. Future research should aim to integrate mechanistic precision with rigorous clinical trial methodology to close this translational gap.

4 Therapeutic advances in HF

HF results from complex interactions among neurohormonal activation, metabolic dysregulation, inflammation, fibrosis, and vascular dysfunction. Understanding these mechanisms has guided the development of targeted therapies. The following sections summarize current and emerging strategies in HF, including pharmacological, device-based, and regenerative approaches.

4.1 Pharmacological and metabolic therapies in HF

HF is a complex cardiovascular syndrome with multifactorial pathophysiology, in which neurohormonal dysregulation plays a pivotal role. In HFrEF, chronic activation of the SNS and the RAAS initially maintains hemodynamic stability but ultimately exacerbates cardiac workload, promotes myocardial remodeling, and accelerates disease progression (159, 160). RAAS and SNS hyperactivity are also implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiorenal syndrome and pulmonary arterial hypertension-related right ventricular failure, highlighting the potential clinical value of neurohormonal inhibition (161, 162).

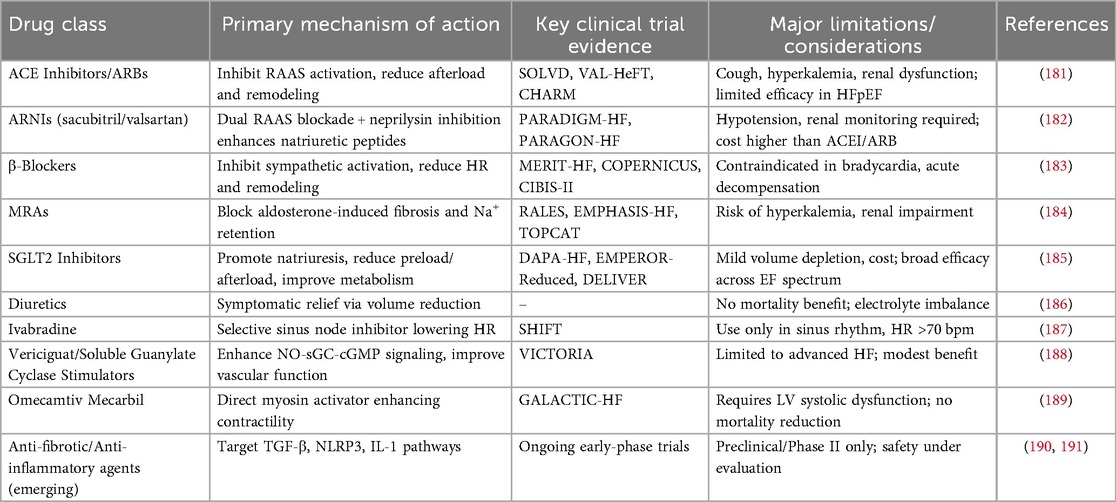

Evidence-based pharmacotherapy for HFrEF includes ACE inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), β-adrenergic blockers, and MRAs. ACEIs and ARBs improve cardiovascular and renal outcomes by suppressing RAAS activity, whereas β-blockers attenuate β1-adrenergic overstimulation, reducing apoptosis, inflammation, and adverse remodeling; their effects on myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) signaling and downstream gene networks further contribute to improved left ventricular function and survival (163–165). A comprehensive overview of the mechanisms, clinical evidence, and limitations of these pharmacological strategies is provided in Table 2. Combination therapy strategies, such as ACEI/ARB plus β-blocker and MRA, or the use of ARNIs, which simultaneously block RAAS and enhance natriuretic peptide (NP) signaling, have demonstrated significant reductions in cardiovascular mortality and HF hospitalization, with favorable tolerability in clinical practice (166–170). Nevertheless, real-world utilization of these guideline-directed therapies remains suboptimal, and polypharmacy may increase the risk of renal impairment and hyperkalemia, underscoring the need for individualized dosing and combination strategies (171, 172).

For HFpEF and HFmrEF, conventional RAAS inhibitors and β-blockers show limited efficacy, and no definitive treatment exists (173–175). Recently, metabolic-targeted therapies, including sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and GLP-1 receptor agonists, have shown promise. SGLT2i exert cardiovascular benefits not only through renal glucose and sodium transport inhibition but also via modulation of cardiomyocyte ionic homeostasis, attenuation of inflammation and oxidative stress, thereby improving outcomes in both HFrEF and HFpEF patients (25, 176–178). GLP-1 receptor agonists ameliorate cardiac metabolic dysfunction, reduce myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis, and improve cardiac function (179). Moreover, SGLT2i confer substantial cardiovascular benefits in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, and metabolic interventions may also mitigate oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, potentially improving cognitive decline, though clinical evidence remains limited (180).

Overall, HF pharmacotherapy is transitioning from simple suppression of maladaptive neurohormonal activation toward restoration of neuroendocrine balance and multi-targeted interventions. Future HF management may integrate conventional RAAS and β-blocker therapy with novel agents such as ARNIs, SGLT2i, and GLP-1 receptor agonists, along with metabolic interventions, to achieve cardiac protection, hemodynamic optimization, and metabolic homeostasis, providing a foundation for precision and individualized therapy (159).

4.2 Device-based and advanced interventional therapies in HF

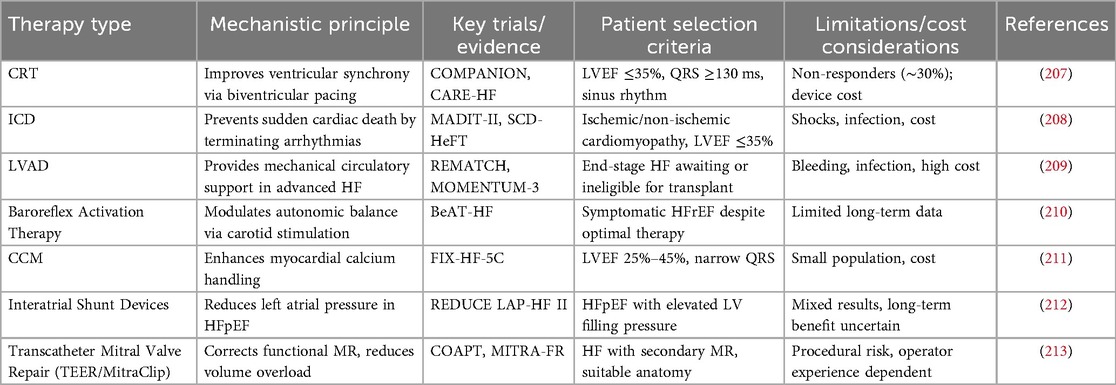

HF patients continue to experience substantial residual risk despite guideline-directed medical therapy, including persistent symptoms, high rates of hospitalization, and mortality (192–194). These limitations have driven the rapid development of device-based interventions, which provide individualized therapies according to HF phenotype and severity. Key device therapies include cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD), mechanical circulatory support (MCS), and heart transplantation. An overview of these device-based and interventional approaches, including their indications, underlying mechanisms, and clinical limitations, is summarized in Table 3. CRT improves ventricular mechanical synchrony, enhancing left ventricular systolic function, reducing mitral regurgitation, promoting reverse remodeling, improving NYHA functional class and exercise capacity, and decreasing hospitalization and mortality (195–197). ICDs are primarily indicated for patients with moderate to severe HF or those at high risk, effectively preventing sudden cardiac death and ventricular arrhythmias, with outcomes influenced by NYHA class and cardiac function (198). For end-stage HF, MCS and heart transplantation provide definitive interventions, improving survival and quality of life, although device-related complications and limited availability remain challenges.

Clinical studies indicate that approximately one-third of CRT recipients are non-responders, with key contributing factors including suboptimal atrioventricular (AV) and interventricular (VV) timing, non-left bundle branch block (non-LBBB), and electromechanical dyssynchrony (199, 200). To address this, emerging device-based sensor technologies and automated optimization algorithms have shown promise in improving long-term clinical outcomes and reducing HF-related rehospitalization, with some evidence suggesting superiority over conventional echocardiography-guided optimization (201, 202). Moreover, concomitant atrial fibrillation (AF) may attenuate CRT-mediated improvements in left ventricular function, and AF burden should be considered in therapeutic strategy and device selection (203). Cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) improves left ventricular systolic function and promotes reverse remodeling in patients with mild QRS prolongation, achieving effects comparable to CRT in this subgroup, though CRT remains more effective in patients with severe QRS prolongation (204).

In elderly HF patients (≥75 years), CRT-D therapy has been shown to reduce HF progression, mortality, and the risk of ventricular arrhythmias, with device reintervention rates comparable to younger populations. However, older patients are at higher risk of device-related complications, and current clinical trials provide limited evidence regarding quality of life and end-of-life care considerations in this population (205, 206). Real-world data also indicate that HF functional class significantly impacts device outcomes: in patients receiving ICD alone, NYHA class III/IV patients exhibit higher risk of HF-related events or death compared with class I/II, whereas CRT-D attenuates this disparity; additionally, patients with milder HF are more prone to ventricular arrhythmias (198).

In summary, device-based therapies play a pivotal role in HF management by improving ventricular synchrony, preventing sudden cardiac death, and providing advanced circulatory support. Integration of individualized indications, outcome evaluation, and emerging device technologies—including automated optimization algorithms, minimally invasive lead placement, and sensor-based monitoring—offers precise and personalized interventions, highlighting the potential of these strategies to reduce residual risk and optimize clinical outcomes across diverse HF populations.

4.3 Emerging biological and personalized therapies in HF

HF is a complex syndrome involving interactions among cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, immune cells, and vascular endothelial cells. Myocardial fibrosis plays a central role in HF progression, and its extent and pattern are closely associated with disease development and prognosis, which can be assessed via imaging and circulating biomarkers (214). Traditional biomarkers such as BNP and NT-proBNP remain essential indicators of myocardial stress and volume overload, whereas multi-marker strategies integrating ST2, Galectin-3, and Copeptin provide deeper insight into HF pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets (215–219).

Intervention strategies have expanded beyond conventional therapy. SGLT2 inhibitors have demonstrated reductions in HF hospitalization and mortality, potentially through modulation of myocardial inflammation and the STAT1-STING-mediated cellular senescence pathway (220, 221). Lifestyle interventions, including adherence to a Mediterranean diet, can improve metabolic profiles and reduce systemic inflammation (222). Cutting-edge biological approaches, such as targeting activated CFs, gene- and cell-based therapies, and recombinant human ACE2 administration, aim to repair or mitigate pathological cardiac remodeling (223, 224). Integrating multi-omics, circulating biomarkers, and clinical variables facilitates precision management, particularly in patients with HFpEF, renal comorbidities, or metabolic disturbances (225–228).

Clinical studies indicate that rapid initiation and titration of guideline-directed therapies in acute HF reduces short-term mortality and rehospitalization, whereas strict sodium restriction in chronic HF has not shown significant outcome improvement (229, 230). Mechanism-targeted interventions, including IL-1/IL-6 blockade, corticosteroids, and colchicine, show potential in acute HF, while triacylglycerol supplementation demonstrates efficacy in triglyceride deposit cardiomyopathy (231, 232). Combining genetic markers, advanced imaging, and artificial intelligence-assisted diagnostics can optimize patient stratification and individualized therapeutic strategies (233). Collectively, emerging biological and personalized therapies provide multidimensional approaches to improve outcomes and slow disease progression in HF patients.

5 Future perspectives and conclusions

Although significant advances have been made in delineating the pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for HF, several challenges persist. Current treatments predominantly target neurohormonal pathways (e.g., RAAS and SNS), yet they only partially mitigate maladaptive cardiac remodeling and fail to adequately address the phenotypic heterogeneity observed in HFpEF patients (160, 234). Furthermore, limited mechanistic understanding of metabolic dysregulation, inflammation, and MVD constrains the development of fully effective interventions. Emerging strategies integrating mechanistic insights and advanced technologies may overcome these limitations. Machine learning–based models have demonstrated superior predictive accuracy for hospitalization and mortality by combining clinical parameters with biomarker and imaging data (235). Multi-omics approaches, including transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiling, have revealed novel pathways involved in cardiomyocyte energy metabolism, iron handling, and ECM remodeling, offering potential targets for personalized therapy (74, 236).

Building on these developments, future research should prioritize integrating omics-derived biomarkers with machine learning and systems biology tools to refine risk prediction models and uncover mechanistically distinct HF subgroups. Such integrative frameworks may enable dynamic, individualized monitoring and more accurate identification of patients who are likely to respond to specific therapeutic modalities (236). In addition, developing personalized therapeutic approaches for distinct HF phenotypes—including HFpEF subgroups defined by metabolic dysfunction, systemic inflammation, or microvascular disease—will be crucial. Aligning therapeutic selection with molecular signatures and comorbidity profiles may help overcome the historical limitations of “one-size-fits-all” treatment paradigms (237). Finally, future clinical trial designs should better incorporate real-world patient complexity, including frailty, multimorbidity, and sex-specific differences that influence treatment response and tolerability. Adaptive and phenotype-stratified trial frameworks may enhance the evaluation of both established and emerging therapies, while digital health tools and patient-reported outcomes can improve longitudinal assessment of functional status and quality of life (238).

Together, these directions underscore the importance of integrating high-resolution mechanistic data with patient-specific phenotyping to enable precision-guided interventions. Translational studies combining experimental models, omics-based biomarker discovery, and clinical validation are expected to refine risk stratification, optimize therapeutic selection, and ultimately improve functional outcomes and survival in HF.

Author contributions

FZ: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. JJ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. XZ: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. CZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JG: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Bozkurt B, Coats A, Tsutsui H. Universal definition and classification of heart failure. J Card Fail. (2021) 27(4):387–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.01.022

2. Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2022) 145:e895–e1032. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063

3. Maryam , Varghese TP, Tazneem B. Unraveling the complex pathophysiology of heart failure: insights into the role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Curr Probl Cardiol. (2024) 49:102411. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2024.102411

4. Abdin A, Bohm M, Shahim B, Karlstrom P, Kulenthiran S, Skouri H, et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment strategies. Int J Cardiol. (2024) 412:132304. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.132304

5. Laborante R, Restivo A, Mele D, Di Francesco M, Ferreira JP, Vasques-Novoa F, et al. Device-based strategies for monitoring congestion and guideline-directed therapy in heart failure: the who, when and how of personalised care. Card Fail Rev. (2025) 11:e11. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2025.01

6. Castiglione V, Gentile F, Ghionzoli N, Chiriaco M, Panichella G, Aimo A, et al. Pathophysiological rationale and clinical evidence for neurohormonal modulation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Card Fail Rev. (2023) 9:e09. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2022.23

7. Juillière Y, Venner C, Filippetti L, Popovic B, Huttin O, Selton-Suty C. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systemic disease linked to multiple comorbidities, targeting new therapeutic options. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. (2018) 111:766–81. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2018.04.007

8. Palaparthi EC, Padala T, Singamaneni R, Manaswini R, Kantula A, Aditya Reddy P, et al. Emerging therapeutic strategies for heart failure: a comprehensive review of novel pharmacological and molecular targets. Cureus. (2025) 17:e81573. doi: 10.7759/cureus.81573

9. Koontalay A, Botti M, Hutchinson A. Narrative synthesis of the effectiveness and characteristics of heart failure disease self-management support programmes. ESC Heart Fail. (2024) 11:1329–40. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.14701

10. Schwinger RHG. Pathophysiology of heart failure. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. (2021) 11:263–76. doi: 10.21037/cdt-20-302

11. Jia G, Aroor AR, Hill MA, Sowers JR. Role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation in promoting cardiovascular fibrosis and stiffness. Hypertension. (2018) 72:537–48. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11065

12. Volpe M, Tocci G, Pagannone E. Activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in heart failure. Ital Heart J. (2005) 6(1):16S–23. Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15945296/15945296

13. Harada K, Sugaya T, Murakami K, Yazaki Y, Komuro I. Angiotensin II type 1A receptor knockout mice display less left ventricular remodeling and improved survival after myocardial infarction. Circulation. (1999) 100:2093–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.20.2093

14. Wozniak M, Tyrankiewicz U, Drelicharz L, Skorka T, Jablonska M, Heinze-Paluchowska S, et al. The effect of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition on myocardial function in early and late phases of dilated cardiomyopathy in Tgaq*44 mice. Kardiol Pol. (2013) 71:730–7. doi: 10.5603/KP.2013.0161

15. Chen H, Yu B, Guo X, Hua H, Cui F, Guan Y, et al. Chronic intermittent hypobaric hypoxia decreases high blood pressure by stabilizing the vascular renin-angiotensin system in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Front Physiol. (2021) 12:639454. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.639454

16. Hawlitschek C, Brendel J, Gabriel P, Schierle K, Salameh A, Zimmer HG, et al. Antihypertensive and cardioprotective effects of different monotherapies and combination therapies in young spontaneously hypertensive rats—a pilot study. Saudi J Biol Sci. (2022) 29:339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.08.093

17. Yi X, Abas R, Raja Muhammad Rooshdi RAW, Yan J, Liu C, Yang C, et al. Time-restricted feeding reduced blood pressure and improved cardiac structure and function by regulating both circulating and local renin-angiotensin systems in spontaneously hypertensive rat model. PLoS One. (2025) 20:e0321078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0321078

18. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. Dual angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibition as an alternative to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: rationale for and design of the prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to determine impact on global mortality and morbidity in heart failure trial (PARADIGM-HF). Eur J Heart Fail. (2013) 15:1062–73. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft052

19. Lind L, Riserus U, Elmstahl S, Arnlov J, Michaelsson K, Titova OE. Combinations of BMI and metabolic syndrome and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2025) 35:104102. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2025.104102

20. Menghoum N, Badii MC, Leroy M, Parra M, Roy C, Lejeune S, et al. Exploring the impact of metabolic comorbidities on epicardial adipose tissue in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2025) 24:134. doi: 10.1186/s12933-025-02688-7

21. Jhund PS, Talebi A, Henderson AD, Claggett BL, Vaduganathan M, Desai AS, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure: an individual patient level meta-analysis. Lancet. (2024) 404:1119–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01733-1

22. Desai AS, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Kulac IJ, Jhund PS, Cunningham J, et al. Finerenone in patients with a recent worsening heart failure event: the FINEARTS-HF trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2025) 85:106–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.09.004

23. Butt JH, Jhund PS, Henderson AD, Claggett BL, Desai AS, Viswanathan P, et al. Finerenone and new-onset diabetes in heart failure: a prespecified analysis of the FINEARTS-HF trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2025) 13:107–18. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00309-7

24. Yeoh SE, Osmanska J, Petrie MC, Brooksbank KJM, Clark AL, Docherty KF, et al. Dapagliflozin vs. metolazone in heart failure resistant to loop diuretics. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44:2966–77. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad341

25. Hundertmark MJ, Adler A, Antoniades C, Coleman R, Griffin JL, Holman RR, et al. Assessment of cardiac energy metabolism, function, and physiology in patients with heart failure taking empagliflozin: the randomized, controlled EMPA-VISION trial. Circulation. (2023) 147:1654–69. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062021

26. Kitzman DW, Lewis GD, Pandey A, Borlaug BA, Sauer AJ, Litwin SE, et al. A novel controlled metabolic accelerator for the treatment of obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: rationale and design of the Phase 2a HuMAIN trial. Eur J Heart Fail. (2024) 26:2013–24. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.3305

27. Mueller S, Winzer EB, Duvinage A, Gevaert AB, Edelmann F, Haller B, et al. Effect of high-intensity interval training, moderate continuous training, or guideline-based physical activity advice on peak oxygen consumption in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2021) 325:542–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26812

28. Besnier F, Labrunee M, Richard L, Faggianelli F, Kerros H, Soukarie L, et al. Short-term effects of a 3-week interval training program on heart rate variability in chronic heart failure. A randomised controlled trial. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. (2019) 62:321–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2019.06.013

29. Wang C, Xing J, Zhao B, Wang Y, Zhang L, Wang Y, et al. The effects of high-intensity interval training on exercise capacity and prognosis in heart failure and coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Ther. (2022) 2022:4273809. doi: 10.1155/2022/4273809

30. Wisloff U, Stoylen A, Loennechen JP, Bruvold M, Rognmo O, Haram PM, et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation. (2007) 115:3086–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675041

31. Yamamoto S, Okamura M, Akashi YJ, Tanaka S, Shimizu M, Tsuchikawa Y, et al. Impact of long-term exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with chronic heart failure- A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ J. (2024) 88:1360–71. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-23-0820

32. Piotrowicz E, Pencina MJ, Opolski G, Zareba W, Banach M, Kowalik I, et al. Effects of a 9-week hybrid comprehensive telerehabilitation program on long-term outcomes in patients with heart failure: the telerehabilitation in heart failure patients (TELEREH-HF) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. (2020) 5:300–8. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5006

33. Gama F, Rocha B, Aguiar C, Strong C, Freitas P, Brizido C, et al. Exercise oscillatory ventilation improves heart failure prognostic scores. Heart Lung Circ. (2023) 32:949–57. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2023.04.291

34. Lewis GD, Malhotra R, Hernandez AF, McNulty SE, Smith A, Felker GM, et al. Effect of oral iron repletion on exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and iron deficiency: the IRONOUT HF randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2017) 317:1958–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5427

35. Zhou B, Wang DD, Qiu Y, Airhart S, Liu Y, Stempien-Otero A, et al. Boosting NAD level suppresses inflammatory activation of PBMCs in heart failure. J Clin Invest. (2020) 130:6054–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI138538

36. Li H, Wang X, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Zhang JZ, Zhou B. SLC39A13 Regulates heart function via mitochondrial iron homeostasis maintenance. Circ Res. (2025) 137(6):e144–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.125.326201

37. Zhang H, Jamieson KL, Grenier J, Nikhanj A, Tang Z, Wang F, et al. Myocardial iron deficiency and mitochondrial dysfunction in advanced heart failure in humans. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11:e022853. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.022853

38. Hoes MF, Grote Beverborg N, Kijlstra JD, Kuipers J, Swinkels DW, Giepmans BNG, et al. Iron deficiency impairs contractility of human cardiomyocytes through decreased mitochondrial function. Eur J Heart Fail. (2018) 20:910–9. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1154

39. Chiang S, Braidy N, Maleki S, Lal S, Richardson DR, Huang ML. Mechanisms of impaired mitochondrial homeostasis and NAD(+) metabolism in a model of mitochondrial heart disease exhibiting redox active iron accumulation. Redox Biol. (2021) 46:102038. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102038

40. Li S, Zhang J, Fu W, Cao J, Li Z, Tian X, et al. Mitochondrial transplantation rescues Ca(2+) homeostasis imbalance and myocardial hypertrophy in SLC25A3-related hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cell Rep. (2024) 43:115065. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.115065

41. Wang YT, Moura AK, Zuo R, Wang Z, Roudbari K, Hu JZ, et al. Defective lipid droplet biogenesis exacerbates oleic acid-induced cellular homeostasis disruption and ferroptosis in mouse cardiac endothelial cells. Cell Death Discov. (2025) 11:374. doi: 10.1038/s41420-025-02669-5

42. Angermann CE, Sehner S, Gerhardt LMS, Santos-Gallego CG, Requena-Ibanez JA, Zeller T, et al. Anaemia predicts iron homoeostasis dysregulation and modulates the response to empagliflozin in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the EMPATROPISM-FE trial. Eur Heart J. (2025) 46:1507–23. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae917

43. Charles-Edwards G, Amaral N, Sleigh A, Ayis S, Catibog N, McDonagh T, et al. Effect of iron isomaltoside on skeletal muscle energetics in patients with chronic heart failure and iron deficiency. Circulation. (2019) 139:2386–98. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038516

44. Packer M, Ferreira JP, Butler J, Filippatos G, Januzzi JL Jr., Gonzalez Maldonado S, et al. Reaffirmation of mechanistic proteomic signatures accompanying SGLT2 inhibition in patients with heart failure: a validation cohort of the EMPEROR program. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2024) 84:1979–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.07.013

45. van der Meer P, van der Wal HH, Melenovsky V. Mitochondrial function, skeletal muscle metabolism, and iron deficiency in heart failure. Circulation. (2019) 139:2399–402. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040134

46. He Z, Gao B, Deng Y, Wu J, Hu X, Qin Z. Associations between systemic immune-inflammation index and heart failure: a cross-sectional study. Medicine. (2024) 103:e40096. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000040096

47. Zheng H, Yin Z, Luo X, Zhou Y, Zhang F, Guo Z. Associations between systemic immunity-inflammation index and heart failure: evidence from the NHANES 1999–2018. Int J Cardiol. (2024) 395:131400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.131400

48. Heidenreich P. Inflammation and heart failure: therapeutic or diagnostic opportunity? J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 69:1286–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.013

49. Sanders-van Wijk S, Tromp J, Beussink-Nelson L, Hage C, Svedlund S, Saraste A, et al. Proteomic evaluation of the comorbidity-inflammation paradigm in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: results from the PROMIS-HFpEF study. Circulation. (2020) 142:2029–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.045810

50. de Boer RA. Myeloperoxidase in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a target against inflammation? JACC Heart Fail. (2023) 11:788–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2023.04.009

51. Schiattarella GG, Rodolico D, Hill JA. Metabolic inflammation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc Res. (2021) 117:423–34. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa217

52. Dong X, Jiang J, Lin Z, Wen R, Zou L, Luo T, et al. Nuanxinkang protects against ischemia/reperfusion-induced heart failure through regulating IKKbeta/IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB-mediated macrophage polarization. Phytomedicine. (2022) 101:154093. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154093

53. Benedetti R, Chianese U, Papulino C, Scisciola L, Cortese M, Formisano P, et al. Unlocking the power of empagliflozin: rescuing inflammation in hyperglycaemia-exposed human cardiomyocytes through comprehensive multi-level analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. (2025) 27:844–56. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.3566

54. Wu Q, Yao Q, Hu T, Yu J, Jiang K, Wan Y, et al. Dapagliflozin protects against chronic heart failure in mice by inhibiting macrophage-mediated inflammation, independent of SGLT2. Cell Rep Med. (2023) 4:101334. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101334

55. Guo W, Zhao L, Huang W, Chen J, Zhong T, Yan S, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, inflammation, and heart failure: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2024) 23:118. doi: 10.1186/s12933-024-02210-5

56. Kittipibul V, Fudim M. Tackling inflammation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: resurrection of vagus nerve stimulation? J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11:e024481. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.024481

57. Stavrakis S, Elkholey K, Morris L, Niewiadomska M, Asad ZUA, Humphrey MB. Neuromodulation of inflammation to treat heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11:e023582. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.023582

58. Bhattarai U, Xu R, He X, Pan L, Niu Z, Wang D, et al. High selenium diet attenuates pressure overload-induced cardiopulmonary oxidative stress, inflammation, and heart failure. Redox Biol. (2024) 76:103325. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2024.103325

59. Xing Z, Chen J, Yu T, Li X, Dong W, Peng C, et al. Aconitum carmichaelii Debx. Attenuates heart failure through inhibiting inflammation and abnormal vascular remodeling. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:5838. doi: 10.3390/ijms24065838

60. Aimo A, Borrelli C, Vergaro G, Piepoli MF, Caterina AR, Mirizzi G, et al. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic heart failure: current evidence and potential approaches. Curr Pharm Des. (2016) 22:4807–22. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160701075027

61. Aimo A, Castiglione V, Borrelli C, Saccaro LF, Franzini M, Masi S, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation in the evolution of heart failure: from pathophysiology to therapeutic strategies. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2020) 27:494–510. doi: 10.1177/2047487319870344

62. D'Oria R, Schipani R, Leonardini A, Natalicchio A, Perrini S, Cignarelli A, et al. The role of oxidative stress in cardiac disease: from physiological response to injury factor. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2020) 2020:5732956. doi: 10.1155/2020/5732956

63. Li T, Wang N, Yi D, Xiao Y, Li X, Shao B, et al. ROS-mediated ferroptosis and pyroptosis in cardiomyocytes: an update. Life Sci. (2025) 370:123565. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2025.123565

64. Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Matsushima S. Oxidative stress and heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2011) 301:H2181–2190. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2011

65. Fu J, Su C, Ge Y, Ao Z, Xia L, Chen Y, et al. PDE4D Inhibition ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure by activating mitophagy. Redox Biol. (2025) 81:103563. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2025.103563

66. Ren H, Hu W, Jiang T, Yao Q, Qi Y, Huang K. Mechanical stress induced mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: novel mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Biomed Pharmacother. (2024) 174:116545. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116545

67. Wang J, Li S, Yu H, Gao D. Oxidative stress regulates cardiomyocyte energy metabolism through the IGF2BP2-dynamin2 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2022) 624:134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.07.089

68. Ye X, Lin ZJ, Hong GH, Wang ZM, Dou RT, Lin JY, et al. Pyroptosis inhibitors MCC950 and VX-765 mitigate myocardial injury by alleviating oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in acute myocardial hypoxia. Exp Cell Res. (2024) 438:114061. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2024.114061

69. Hou X, Hu G, Wang H, Yang Y, Sun Q, Bai X. Acot1 overexpression alleviates heart failure by inhibiting oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis through the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Exp Anim. (2025). doi: 10.1538/expanim.24-0129

70. Wang Z, Zhang Y, Wang L, Yang C, Yang H. NBP relieves cardiac injury and reduce oxidative stress and cell apoptosis in heart failure mice by activating Nrf2/HO-1/Ca(2+)-SERCA2a axis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2022) 2022:7464893. doi: 10.1155/2022/7464893

71. Zhu K, Fan R, Cao Y, Yang W, Zhang Z, Zhou Q, et al. Glycyrrhizin attenuates myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury by suppressing inflammation, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis via the HMGB1-TLR4-GPX4 pathway. Exp Cell Res. (2024) 435:113912. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2024.113912

72. Peoples JN, Saraf A, Ghazal N, Pham TT, Kwong JQ. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in heart disease. Exp Mol Med. (2019) 51:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0355-7

73. Czubryt MP, Hale TM. Cardiac fibrosis: pathobiology and therapeutic targets. Cell Signal. (2021) 85:110066. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.110066

74. Ghazal R, Wang M, Liu D, Tschumperlin DJ, Pereira NL. Cardiac fibrosis in the multi-omics era: implications for heart failure. Circ Res. (2025) 136:773–802. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.124.325402

75. Liu M, Lopez de Juan Abad B, Cheng K. Cardiac fibrosis: myofibroblast-mediated pathological regulation and drug delivery strategies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. (2021) 173:504–19. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.03.021

76. Andersen S, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Vonk Noordegraaf A, de Man FS. Right ventricular fibrosis. Circulation. (2019) 139:269–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035326

77. Schimmel K, Ichimura K, Reddy S, Haddad F, Spiekerkoetter E. Cardiac fibrosis in the pressure overloaded left and right ventricle as a therapeutic target. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:886553. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.886553

78. Li R, Frangogiannis NG. Integrins in cardiac fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2022) 172:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2022.07.006

79. Yao Y, Hu C, Song Q, Li Y, Da X, Yu Y, et al. ADAMTS16 Activates latent TGF-beta, accentuating fibrosis and dysfunction of the pressure-overloaded heart. Cardiovasc Res. (2020) 116:956–69. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz187

80. Andenaes K, Lunde IG, Mohammadzadeh N, Dahl CP, Aronsen JM, Strand ME, et al. The extracellular matrix proteoglycan fibromodulin is upregulated in clinical and experimental heart failure and affects cardiac remodeling. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0201422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201422

81. Deng B, Zhang Y, Zhu C, Wang Y, Weatherford E, Xu B, et al. Divergent actions of myofibroblast and myocyte beta(2)-Adrenoceptor in heart failure and fibrotic remodeling. Circ Res. (2023) 132:106–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.321816

82. Frangogiannis NG. Cardiac fibrosis: cell biological mechanisms, molecular pathways and therapeutic opportunities. Mol Aspects Med. (2019) 65:70–99. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2018.07.001

83. Micheletti R, Plaisance I, Abraham BJ, Sarre A, Ting CC, Alexanian M, et al. The long noncoding RNA Wisper controls cardiac fibrosis and remodeling. Sci Transl Med. (2017) 9:eaai9118. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai9118

84. Li L, Zhao Q, Kong W. Extracellular matrix remodeling and cardiac fibrosis. Matrix Biol. (2018) 68–69:490–506. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.01.013

85. Segura AM, Frazier OH, Buja LM. Fibrosis and heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. (2014) 19:173–85. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9365-4

86. Farris SD, Don C, Helterline D, Costa C, Plummer T, Steffes S, et al. Cell-specific pathways supporting persistent fibrosis in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 70:344–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.040

87. Pandey AK, Bhatt DL, Pandey A, Marx N, Cosentino F, Pandey A, et al. Mechanisms of benefits of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44:3640–51. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad389

88. Travers JG, Wennersten SA, Pena B, Bagchi RA, Smith HE, Hirsch RA, et al. HDAC inhibition reverses preexisting diastolic dysfunction and blocks covert extracellular matrix remodeling. Circulation. (2021) 143:1874–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046462

89. Frangogiannis NG. Cardiac fibrosis. Cardiovasc Res. (2021) 117:1450–88. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa324

90. Travers JG, Kamal FA, Robbins J, Yutzey KE, Blaxall BC. Cardiac fibrosis: the fibroblast awakens. Circ Res. (2016) 118:1021–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306565

91. Valiente-Alandi I, Schafer AE, Blaxall BC. Extracellular matrix-mediated cellular communication in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2016) 91:228–37. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.01.011

92. Bielawska M, Warszynska M, Stefanska M, Blyszczuk P. Autophagy in heart failure: insights into mechanisms and therapeutic implications. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. (2023) 10:352. doi: 10.3390/jcdd10080352

93. Li J, Zhang D, Wiersma M, Brundel B. Role of autophagy in proteostasis: friend and foe in cardiac diseases. Cells. (2018) 7:279. doi: 10.3390/cells7120279

94. Nah J, Zablocki D, Sadoshima J. The role of autophagic cell death in cardiac disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2022) 173:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2022.08.362

95. Tang Y, Xu W, Liu Y, Zhou J, Cui K, Chen Y. Autophagy protects mitochondrial health in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. (2024) 29:113–23. doi: 10.1007/s10741-023-10354-x

96. Oeing CU, Mishra S, Dunkerly-Eyring BL, Ranek MJ. Targeting protein kinase G to treat cardiac proteotoxicity. Front Physiol. (2020) 11:858. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00858

97. Maroli G, Schanzer A, Gunther S, Garcia-Gonzalez C, Rupp S, Schlierbach H, et al. Inhibition of autophagy prevents cardiac dysfunction at early stages of cardiomyopathy in Bag3-deficient hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2024) 193:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2024.06.001

98. Delalat S, Sultana I, Osman H, Sieme M, Zhazykbayeva S, Herwig M, et al. Dysregulated inflammation, oxidative stress, and protein quality control in diabetic HFpEF: unraveling mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2025) 24:211. doi: 10.1186/s12933-025-02734-4

99. Cui T, Lai Y, Janicki JS, Wang X. Nuclear factor erythroid-2 related factor 2 (Nrf2)-mediated protein quality control in cardiomyocytes. Front Biosci. (2016) 21:192–202. doi: 10.2741/4384

100. Kobak KA, Zarzycka W, King CJ, Borowik AK, Peelor FF 3rd, Baehr LM, et al. Proteostatic imbalance drives the pathogenesis and age-related exacerbation of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Basic Transl Sci. (2025) 10:475–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2024.11.006

101. Zarzycka W, Kobak KA, King CJ, Peelor FF, Miller BF, Chiao YA. Hyperactive mTORC1/4EBP1 signaling dysregulates proteostasis and accelerates cardiac aging. bioRxiv. (2024). doi: 10.1101/2024.05.13.594044

102. Hartman H, Uy G, Uchida K, Scarborough EA, Yang Y, Barr E, et al. ROR2 drives right ventricular heart failure via disruption of proteostasis. bioRxiv. (2025). doi: 10.1101/2025.02.01.635961

103. McLendon JM, Zhang X, Stein CS, Baehr LM, Bodine SC, Boudreau RL. A specialized centrosome-proteasome axis mediates proteostasis and influences cardiac stress through Txlnb. bioRxiv. (2024). doi: 10.1101/2024.02.12.580020

104. McLendon JM, Zhang X, Stein CS, Baehr LM, Bodine SC, Boudreau RL. Gain and loss of the centrosomal protein taxilin-beta influences cardiac proteostasis and stress. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2025) 201:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2025.02.008

105. Neu M, Deshpande A, Borlepawar A, Hammer E, Alameldeen A, Vocking P, et al. TRIM24 Regulates chromatin remodeling and calcium dynamics in cardiomyocytes. Cell Commun Signal. (2025) 23:312. doi: 10.1186/s12964-025-02323-8

106. Fanjul V, Jorge I, Camafeita E, Macias A, Gonzalez-Gomez C, Barettino A, et al. Identification of common cardiometabolic alterations and deregulated pathways in mouse and pig models of aging. Aging Cell. (2020) 19:e13203. doi: 10.1111/acel.13203

107. Narayanan G, Halim A, Hu A, Avin KG, Lu T, Zehnder D, et al. Molecular phenotyping and mechanisms of myocardial fibrosis in advanced chronic kidney disease. Kidney360. (2023) 4:1562–79. doi: 10.34067/KID.0000000000000276

108. Olkowski AA, Wojnarowicz C, Laarveld B. Pathophysiology and pathological remodelling associated with dilated cardiomyopathy in broiler chickens predisposed to heart pump failure. Avian Pathol. (2020) 49:428–39. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2020.1757620

109. Li A, Gao M, Liu B, Qin Y, Chen L, Liu H, et al. Mitochondrial autophagy: molecular mechanisms and implications for cardiovascular disease. Cell Death Dis. (2022) 13:444. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04906-6

110. Cetrullo S, D'Adamo S, Tantini B, Borzi RM, Flamigni F. mTOR, AMPK, and Sirt1: key players in metabolic stress management. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. (2015) 25:59–75. doi: 10.1615/critreveukaryotgeneexpr.2015012975

111. Maejima Y, Titus AS, Zablocki D, Sadoshima J. Recent progress regarding the role of autophagy in cardiac disease. Cardiovasc Res. (2025):cvaf203. [Online ahead of print]. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaf203

112. Liao M, Xie Q, Zhao Y, Yang C, Lin C, Wang G, et al. Main active components of Si-Miao-Yong-An decoction (SMYAD) attenuate autophagy and apoptosis via the PDE5A-AKT and TLR4-NOX4 pathways in isoproterenol (ISO)-induced heart failure models. Pharmacol Res. (2022) 176:106077. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106077

113. Wang D, Lv L, Xu Y, Jiang K, Chen F, Qian J, et al. Cardioprotection of Panax Notoginseng saponins against acute myocardial infarction and heart failure through inducing autophagy. Biomed Pharmacother. (2021) 136:111287. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111287

114. Zhang X, Wang Q, Wang X, Chen X, Shao M, Zhang Q, et al. Tanshinone IIA protects against heart failure post-myocardial infarction via AMPKs/mTOR-dependent autophagy pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. (2019) 112:108599. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108599

115. Gao G, Chen W, Yan M, Liu J, Luo H, Wang C, et al. Rapamycin regulates the balance between cardiomyocyte apoptosis and autophagy in chronic heart failure by inhibiting mTOR signaling. Int J Mol Med. (2020) 45:195–209. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4407

116. Corsetti G, Pasini E, Romano C, Chen-Scarabelli C, Scarabelli TM, Flati V, et al. How can malnutrition affect autophagy in chronic heart failure? Focus and perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:3332. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073332

117. Hu L, Gao D, Lv H, Lian L, Wang M, Wang Y, et al. Finding new targets for the treatment of heart failure: endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. (2023) 16:1349–56. doi: 10.1007/s12265-023-10410-9

118. Rush CJ, Berry C, Oldroyd KG, Rocchiccioli JP, Lindsay MM, Touyz RM, et al. Prevalence of coronary artery disease and coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. (2021) 6:1130–43. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.1825

119. Singh A, Ashraf S, Irfan H, Venjhraj F, Verma A, Shaukat A, et al. Heart failure and microvascular dysfunction: an in-depth review of mechanisms, diagnostic strategies, and innovative therapies. Ann Med Surg. (2025) 87:616–26. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000002971

120. Ahmad A, Corban MT, Toya T, Verbrugge FH, Sara JD, Lerman LO, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is associated with exertional haemodynamic abnormalities in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. (2021) 23:765–72. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2010

121. Yang JH, Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Redfield MM, Lerman A, Borlaug BA. Endothelium-dependent and independent coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. (2020) 22:432–41. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1671

122. Gamrat A, Surdacki MA, Chyrchel B, Surdacki A. Endothelial dysfunction: a contributor to adverse cardiovascular remodeling and heart failure development in type 2 diabetes beyond accelerated atherogenesis. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:2090. doi: 10.3390/jcm9072090

123. Cauwenberghs N, Godderis S, Sabovcik F, Cornelissen V, Kuznetsova T. Subclinical heart remodeling and dysfunction in relation to peripheral endothelial dysfunction: a general population study. Microcirculation. (2021) 28:e12731. doi: 10.1111/micc.12731

124. Shantsila E, Wrigley BJ, Blann AD, Gill PS, Lip GY. A contemporary view on endothelial function in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. (2012) 14:873–81. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs066

125. Balmain S, Padmanabhan N, Ferrell WR, Morton JJ, McMurray JJ. Differences in arterial compliance, microvascular function and venous capacitance between patients with heart failure and either preserved or reduced left ventricular systolic function. Eur J Heart Fail. (2007) 9:865–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.06.003

126. Aguado-Alvaro LP, Garitano N, Pelacho B. Fibroblast diversity and epigenetic regulation in cardiac fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:6004. doi: 10.3390/ijms25116004

127. Shi J, Yang C, Zhang J, Zhao K, Li P, Kong C, et al. NAT10 is involved in cardiac remodeling through ac4C-mediated transcriptomic regulation. Circ Res. (2023) 133:989–1002. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.322244

128. Gomes CPC, Schroen B, Kuster GM, Robinson EL, Ford K, Squire IB, et al. Regulatory RNAs in heart failure. Circulation. (2020) 141:313–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042474

129. Yang YL, Li XW, Chen HB, Tang QD, Li YH, Xu JY, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals writers of RNA modification-mediated immune microenvironment and cardiac resident Macro-MYL2 macrophages in heart failure. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2024) 24:432. doi: 10.1186/s12872-024-04080-x

130. Ijaz T, Burke MA. BET protein-mediated transcriptional regulation in heart failure. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:6059. doi: 10.3390/ijms22116059

131. Kim SY, Zhang X, Schiattarella GG, Altamirano F, Ramos TAR, French KM, et al. Epigenetic reader BRD4 (bromodomain-containing protein 4) governs nucleus-encoded mitochondrial transcriptome to regulate cardiac function. Circulation. (2020) 142:2356–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047239

132. Stratton MS, Bagchi RA, Felisbino MB, Hirsch RA, Smith HE, Riching AS, et al. Dynamic chromatin targeting of BRD4 stimulates cardiac fibroblast activation. Circ Res. (2019) 125:662–77. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315125

133. Feng Y, Cai L, Hong W, Zhang C, Tan N, Wang M, et al. Rewiring of 3D chromatin topology orchestrates transcriptional reprogramming and the development of human dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. (2022) 145:1663–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055781

134. Gi WT, Haas J, Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Kayvanpour E, Tappu R, Lehmann DH, et al. Epigenetic regulation of alternative mRNA splicing in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:1499. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051499

135. Gonzalez-Valdes I, Hidalgo I, Bujarrabal A, Lara-Pezzi E, Padron-Barthe L, Garcia-Pavia P, et al. Bmi1 limits dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure by inhibiting cardiac senescence. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:6473. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7473